Abstract

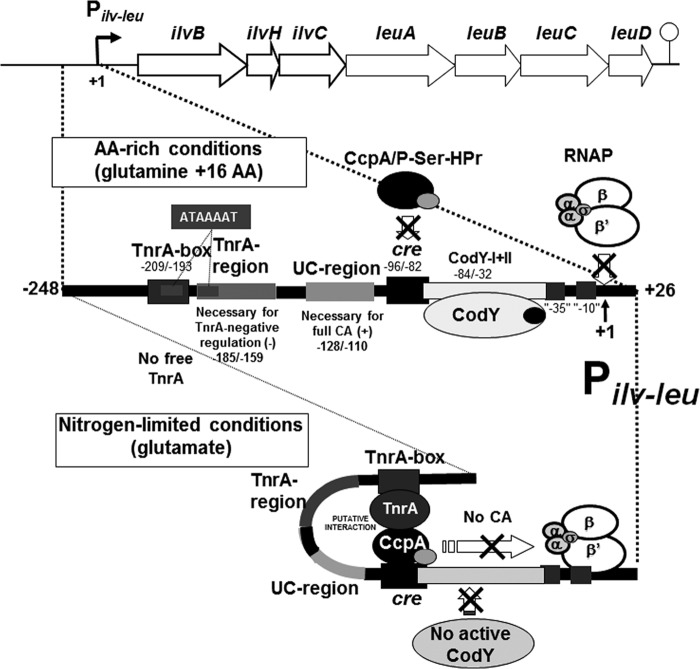

The Bacillus subtilis ilv-leu operon functions in the biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids. It undergoes catabolite activation involving a promoter-proximal cre which is mediated by the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr. This activation of ilv-leu expression is negatively regulated through CodY binding to a high-affinity site in the promoter region under amino acid-rich growth conditions, and it is negatively regulated through TnrA binding to the TnrA box under nitrogen-limited growth conditions. The CcpA-mediated catabolite activation of ilv-leu required a helix face-dependent interaction of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr with RNA polymerase and needed a 19-nucleotide region upstream of cre for full activation. DNase I footprinting indicated that CodY binding to the high-affinity site competitively prevented the binding of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr to cre. This CodY binding not only negated catabolite activation but also likely inhibited transcription initiation from the ilv-leu promoter. The footprinting also indicated that TnrA and the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr simultaneously bound to the TnrA box and the cre site, respectively, which are 112 nucleotides apart; TnrA binding to its box was likely to induce DNA bending. This implied that interaction of TnrA bound to its box with the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr bound to cre might negate catabolite activation, but TnrA bound to its box did not inhibit transcription initiation from the ilv-leu promoter. Moreover, this negation of catabolite activation by TnrA required a 26-nucleotide region downstream of the TnrA box.

INTRODUCTION

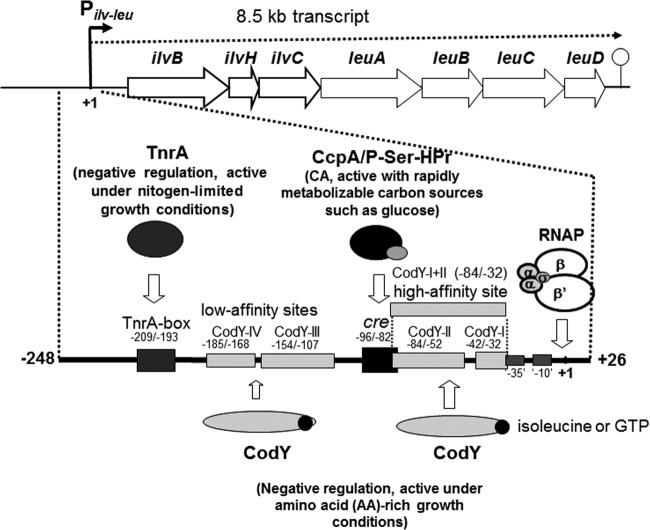

Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) are the most abundant amino acids (AAs) in proteins and form the hydrophobic cores of the proteins. Moreover, these AAs are precursors for the biosynthesis of iso- and anteiso-branched fatty acids, which represent the major fatty acid species of the membrane lipids in Bacillus species (1). The initial step of isoleucine or valine synthesis is the condensation of threonine and pyruvate or two pyruvates, which leads to the formation of branched-chain keto-acids (2). Leucine is synthesized from a branched-chain keto acid, i.e., α-ketoisovalerate. The Bacillus subtilis ilv-leu operon comprises seven genes (ilvB, -H, and -C and leuA, -B, -C, and -D) necessary for the biosynthesis of BCAAs (3) (Fig. 1). Ludwig et al. first communicated that the ilv-leu operon was positively regulated by CcpA (4). Subsequently, it was revealed that transcription of the ilv-leu operon undergoes catabolite activation (CA) involving the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr proteins (5, 6), which mediates carbon catabolite control of not only hundreds of catabolic operons and genes but also several cellular processes (7). This CcpA-mediated CA of ilv-leu, which is evoked by binding of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr to the catabolite-responsible element (cre) site (Fig. 1), links carbon metabolism to AA anabolism. Global gene expression studies on AA availability (8) and CodY regulation (9), as well as a study on metabolic linking of ilv-leu expression to nitrogen metabolism (10), revealed that the ilv-leu operon is under direct negative transcriptional control through two major global regulators of nitrogen metabolism (TnrA and CodY) (Fig. 1). TnrA is known to both activate and repress nitrogen-regulated genes during nitrogen-limited growth through its binding to the TnrA box (11). But, TnrA is trapped by glutamine synthase under nitrogen-rich growth conditions, preventing it from regulating its target genes (11). The CodY protein bound to CodY-binding sites (12–14) is a GTP-binding repressor (or, rarely, activator) of many anabolic and cellular process operons, including ilv-leu, which are normally quiescent when cells are growing under AA-rich conditions (15). A high concentration of GTP activates the CodY repressor, which serves as a gauge of the general energetic capacity of cells. A stringent response renders RelA able to synthesize guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp), which inhibits GMP kinase, which results in a GTP decrease (16) and inactivation of CodY. CodY is also induced through direct interaction with BCAAs (especially isoleucine) to bind to the CodY-binding sites of the promoter regions of its target genes and operons for their repression or activation of ackA, which encodes acetate kinase (17, 18).

FIG 1.

Catabolite activation of the B. subtilis ilv-leu operon mediated by CcpA and its negation by CodY- or TnrA-mediated negative regulation under AA-rich or nitrogen-limited growth conditions. The ilv-leu operon involved in the biosynthesis of BCAAs consists of the ilvBHC and leuABCD genes and is transcribed from nt +1 of the ilv-leu promoter (Pilv-leu) to the terminator to produce a 8.5-kb transcript. CA of the ilv-leu operon is evoked by binding of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr, which is formed upon an increase in the in vivo concentration of fructose-bisphosphate during growth on rapidly metabolizable carbon source such as glucose (7), to the cre site (nt −96/−82). CodY associated with the corepressors of BCAAs and GTP binds to the CodY-I (nt −42/−32) and CodY-II (−84/−52) [CodY-I+II (−84/−32)] high-affinity sites and to the CodY-III (−154/−107) and CodY-IV (−185/−168) low-affinity sites under AA-rich growth conditions (nitrogen source, glutamine plus 16 AAs). CodY binding to the CodY-I+II effectively negates CcpA-mediated CA of ilv-leu. This CA is also negated by binding of TnrA to its box (nt −209/−193), which becomes free from glutamine syntase under nitrogen-limited growth conditions (nitrogen source, glutamate only) (11).

It is notable that CcpA-mediated CA is associated with the respective counteracting regulation mediated by CodY and TnrA under both AA-rich and nitrogen-limited growth conditions. To achieve the full growth potential of rapidly metabolizable carbohydrates such as glucose, CcpA attempts to enhance the expression of ilv-leu to make the cell synthesize more BCAAs for rapid growth. However, when enough BCAAs are supplied from AA-rich medium, negative regulation exerted by CodY interacting with these AAs overwhelms the CcpA-mediated CA to prevent their excess synthesis for maintenance of their appropriate concentrations in vivo. On the other hand, when cells are grown in a nitrogen-limited medium containing glutamate as the sole nitrogen source, TnrA decreases the CcpA-mediated CA to adjust the amounts of BCAAs in response to a poor nitrogen supply. Consequently, the ilv-leu operon is maximally expressed under nitrogen-rich growth conditions, using nitrogen sources such as glutamine when both CodY and TnrA are inactive.

Furthermore, proteome and transcriptome analyses of the stringent response revealed that the ilv-leu operon exhibited positive stringent transcription control in response to AA starvation induced by dl-norvaline addition (19). The lysine starvation led to RelA-dependent positive stringent control of ilv-leu, as dl-norvaline treatment did (20). An increase in the ppGpp concentration due to RelA stimulation might reduce the GTP concentration through severe inhibition of GMP kinase by ppGpp (16), whereby ATP increases through feedback activation of its synthesis due to decreased GTP (20). The increased concentration of ATP, an in vivo RNA polymerase (RNAP) substrate, enhances the transcription initiation of ilv-leu possessing adenine at the 5′-site of the ilv-leu transcript (20, 21).

In this paper, we describe the molecular mechanism underlying CcpA-mediated CA of the B. subtilis ilv-leu operon and its negation by either CodY- or TnrA-mediated negative regulation. This CA involving a promoter-proximal cre is mediated by the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr and requires a 19-nucleotide (nt) region upstream of the cre site for full CA (UC region). CodY interacted with a promoter-proximal high-affinity binding site to negate CA. TnrA bound to the TnrA box was likely to interact with the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr bound to the cre site through DNA bending to negate CA. This negation required a 26-nt region downstream of the TnrA box (TnrA region). Interestingly, a 7-nt direct repeat, ATAAAAT, which is likely required for the TnrA-mediated negative regulation, was found in the middle of the TnrA box and in the most upstream part of the TnrA region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The B. subtilis strains used in this work are listed in Table 1. Strains FU1176, FU1177, FU1178, and FU1179 carrying a lacZ fusion with the respective regions of the ilv-leu promoter (Pilv-leu) carrying the cre site and various lengths of its upstream sequence (nt −110, −120, −130, and −140/+26; +1 is the transcription initiation nucleotide) at the amyE locus were constructed as follows. The PCRs were performed using DNA of strain 168 and primer pairs Fd-110, Fd-120, Fd-130, and Fd-140/D+26R (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) for construction of strains FU1176, FU1177, FU1178, and FU1179, respectively. The resulting PCR products were trimmed with XbaI and BamHI and then ligated with the XbaI-BamHI arm of plasmid pCRE-test2 (22). The ligated DNAs were used for transformation of Escherichia coli strain DH5α to an ampicillin resistance phenotype (50 μg ml−1) on Luria-Bertani medium (LB) plates (23). Correct cloning of each of the lacZ fusions in plasmid pCRE-test2 was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The resulting plasmids were linearized with PstI and then used for double-crossover transformation of strain 168 to a chloramphenicol resistance phenotype (5 μg ml−1) on tryptose blood agar base (Difco) plates containing 10 mM glucose (TBABG), which produced strains FU1176, FU1177, FU1178, and FU1179.

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| 168 | trpC2 | 43 |

| PS37 | trpC2 gid::spc ΔcodY | 44 |

| FU659 | trpC2 tnrA62::Tn917 | 10 |

| FU676 (Δ0) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26)-lacZ] | 10 |

| FU735 (Δ0 ΔcodY) | trpC2 gid::spec ΔcodY amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26)-lacZ] | 6 |

| FU735 | trpC2 gid::spc ΔcodY amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26)-lacZ] | 6 |

| FU731 | trpC2 ccpA::neo amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26)-lacZ] | 6 |

| FU846 (Δ11) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−66/−56)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU849 (Δ16) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−69/−54)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU847 (Δ21) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−71/−51)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU848 (Δ32) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−77/−46)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU861 (Δ11 ΔcodY) | trpC2 gid::spec ΔcodY amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−66/−56)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU864 (Δ16 ΔcodY) | trpC2 gid::spec ΔcodY amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−69/−54)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU862 (Δ21 ΔcodY) | trpC2 gid::spec ΔcodY amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−71/−51)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU863 (Δ32 ΔcodY) | trpC2 gid::spec ΔcodY amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−77/−46)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU865 (iΔ11) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−149/−139)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU854 (iΔ16) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−154/−139)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU866 (iΔ32) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−159/−128)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU868 (iΔ44) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−164/−121)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU869 (iΔ53) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−169/−117)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU887 (iΔ63) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−174/−112)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU870 (iΔ11 tnrA) | trpC2 tnrA62::Tn917 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−149/−139)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU856 (iΔ16 tnrA) | trpC2 tnrA62::Tn917 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−154/−139)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU871 (iΔ32 tnrA) | trpC2 tnrA62::Tn917 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−159/−128)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU873 (iΔ44 tnrA) | trpC2 tnrA62::Tn917 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−164/−121)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU874 (iΔ53 tnrA) | trpC2 tnrA62::Tn917 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−169/−117)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU888 (iΔ63 tnrA) | trpC2 tnrA62::Tn917 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−174/−112)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1159 (ΔD2) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−153/−149)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1163 (ΔD1) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−158/−154)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1170 (ΔU0) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−163/−159)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1162 (ΔU1) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−168/−164)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1157 (ΔU2) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−173/−169)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1158 (ΔU3) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−178/−174)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1160 (ΔU4) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−185/−179)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1161 (ΔU5) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−192/−186)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU722 | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) cre(G-89T C-84T)-lacZ] | 6 |

| FU679 | trpC2 tnrA62::Tn917 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26)-lacZ] | 6 |

| FU724 | trpC2 tnrA62::Tn917 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) cre(G-89T C-84T)-lacZ] | 6 |

| FU1172 (ΔC1) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−123/−119)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1173 (ΔC2) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−128/−124)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1174 (ΔC1 tnrA) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−123/−119)-lacZ] tnrA::Tn917 | This work |

| FU1175 (ΔC2 tnrA) | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−248/+26) (Δ−128/−124)-lacZ] tnrA::Tn917 | This work |

| FU714 | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−165/+26)-lacZ] | 6 |

| FU715 | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−150/+26)-lacZ] | 6 |

| FU716 | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−100/+26)-lacZ] | 6 |

| FU717 | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−55/+26)-lacZ] | 6 |

| FU1176 | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−110/+26)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1177 | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−120/+26)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1178 | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−130/+26)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1179 | trpC2 amyE::[cat Pilv-leu (−140/+26)-lacZ] | This work |

Strain FU676 carries a lacZ fusion with the Pilv-leu region (nt −248/+26) (Fig. 1) at the amyE locus. A series of deletions were introduced between the cre site and −35 region of Pilv-leu in this fusion as follows. The first recombinant PCRs to create a series of deletions were performed using DNA of strain 168 and primer pairs D-248F/ilv-cre-d11R, -d16R, -d21R, and -d32R and ilv-cre-d11F, -d16F, -d21F, and -d32F/D+26R (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) for construction of the Δ11 (nt −66/−56), Δ16 (−69/−54), Δ21 (−71/−51), and Δ32 (−77/−46) deletions, respectively. The second PCRs were performed using each set of two PCR fragments carrying Δ11, Δ16, Δ21, or Δ32 and a primer pair (D-248F/D+26R) to yield DNA fragments (nt −248/+26) carrying the respective deletions. The resulting PCR products were trimmed with XbaI and BamHI and then ligated with the XbaI-BamHI arm of plasmid pCRE-test2, and the lacZ fusions were integrated into the amyE locus as described above. The resulting strains were FU846 (Δ11), FU849 (Δ16), FU847 (Δ21), and FU848 (Δ32). The lacZ fusions in strains FU846, FU849, FU847, and FU848 were transferred to strain PS37 (ΔcodY) by transformation with DNAs of these strains to a chloramphenicol resistance phenotype (5 μg ml−1) on TBABG plates, which produced strains FU861, FU864, FU862, and FU863 carrying ΔcodY and one of the Δ11, Δ16, Δ21, and Δ32 deletions.

Another series of sequential deletions were introduced between the TnrA box and cre site in Pilv-leu (nt −248/+26). The first recombinant PCRs were performed using DNA of strain 168 and primer pairs D-248F/ilv-i11R, -i16R, -i32R, i42R, -i53R, and -i63R and ilv-i11F, -i16F, -i32F, -i42F, -i53F, and -i63F/D+26R (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) for construction of the iΔ11 (nt −149/−139), iΔ16 (−154/−139), iΔ32 (−159/−128), iΔ44 (−164/−121), iΔ53 (−169/−117), or iΔ63 (−174/−112) deletions, respectively. The second PCRs were performed using each set of two PCR fragments carrying iΔ11, iΔ16, iΔ32, iΔ44, iΔ53, or iΔ63 and a primer pair (D-248F/D+26R) to yield DNA fragments (nt −248/+26) carrying the respective deletions. The resulting PCR products were cloned into plasmid pCRE-test2, and the lacZ fusions were integrated into the amyE locus as described above. The resulting strains were FU865 (iΔ11), FU854 (iΔ16), FU866 (iΔ32), FU868 (iΔ44), FU869 (iΔ53), and FU887 (iΔ63). These strains were transformed with DNA of strain FU659 (tnrA62::Tn917) with erythromycin resistance (0.3 μg ml−1) on TBABG plates, which resulted in strains FU870, FU856, FU871, FU873, FU874, and FU888, carrying tnrA62::Tn917 and one of the iΔ11, iΔ16, iΔ32, iΔ44, iΔ53, and iΔ63 deletions.

Another series of segmented deletions of 5 or 7 nt were introduced in the regions downstream of the TnrA box and upstream of the cre site in Pilv-leu (nt −248/+26), respectively. The first recombinant PCRs were performed using DNA of strain 168 and primer pairs D-248F/D2-R, D1-R, U0-R, U1-R, U2-R, U3-R, U4-R, and U5-R and D2-F, D1-F, U0-F, U1-F, U2-F, U3-F, U4-F, and U5-F/D+26R (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) for construction of the ΔD2 (nt −153/−149), ΔD1 (−158/−154), ΔU0 (−163/−159), ΔU1 (−168/−164), ΔU2 (−173/−169), ΔU3 (−178/−174), ΔU4 (−185/−179), and ΔU5 (−192/−186) deletions downstream of the TnrA box, and we used the same template and primer pairs (D-248F/C1-R and C2-R and C1F and C2F/D+26) (see Table S1) for construction of the ΔC1 (nt −123/−119) and ΔC2 (−128/−124) deletions upstream of the cre site, respectively. The second PCRs were performed using each set of two PCR fragments carrying ΔD2, ΔD1, ΔU0, ΔU1, ΔU2, ΔU3, ΔU4, ΔU5, ΔC1, or ΔC2 and a primer pair (D-248F/D+26R) to yield DNA fragments (nt −248/+26) carrying the respective deletions. The resulting PCR products were cloned into plasmid pCRE-test2, and the lacZ fusions were integrated into the amyE locus as described above. The resulting strains were FU1159 (ΔD2), FU1163 (ΔD1), FU1170 (ΔU0), FU1162 (ΔU1), FU1157 (ΔU2), FU1158 (ΔU3), FU1160 (ΔU4), FU1161 (ΔU5), FU1172 (ΔC1), and FU1173 (ΔC2). Strains FU1172 and FU1173 were transformed with DNA of strain FU659 (tnrA62::Tn917) with erythromycin resistance, which resulted in strains FU1174 and FU1175 carrying tnrA62::Tn917 and ΔC1 and ΔC2, respectively.

Production of CodY, TnrA, CcpA, HPr, and HPrK.

To clone and express the codY gene in E. coli, a codY region was amplified by PCR using primer pair codY-F/codY-R (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) and DNA of strain 168 as a template. The resulting PCR product was ligated with vector pCR2.1-TOPO according to the instructions for the TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Life Technologies). After correct cloning of the fragment into the plasmid was confirmed by DNA sequencing, the constructed plasmid was digested with NdeI and BamHI. The resulting fragment was ligated with the NdeI and BamHI arm of vector pET-22b(+) (Novagen, Merck Millipore), and then ligated DNA was used for transformation of E. coli BL21(DE3) to produce plasmid pET-codY. The CodY protein was overexpressed in the E. coli cells by the addition of isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to the LB medium, and a crude extract was prepared as described previously (24). The tnrA and ptsH genes were cloned and overexpressed by the same procedure as above, using the respective primer pairs tnrA-F/tnrA-R and ptsH-F/ptsH-R (see Table S1) and DNA of strain 168 as a template. The His-tagged HPrK protein was cloned and overexpressed as described above except for the use of another primer pair, hprK-F/hprK-R (see Table S1) for hprK amplification and vector pET-16b for its cloning, which was designed to form a six-histidine tag at the N terminal of the overexpressed protein. The CcpA protein was overexpressed in E. coli as described previously (25).

Purification of CodY, TnrA, CcpA, HPr, and His-tagged HPrK.

Purification of the CodY protein was performed as follows. A crude extract was placed on a DEAE-Toyopearl 650M column (Tosoh) equilibrated with 10 mM Tris-Cl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.1 mM Na-EDTA, and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) (buffer A). After the column had been washed with buffer A, the CodY protein was eluted with buffer A containing 200 mM NaCl. The eluted fractions were pooled and dialyzed against buffer A. Moreover, the TnrA protein was purified as reported elsewhere (11), with the modification that all TnrA purification steps were performed in buffer A.

The CcpA protein was purified as described previously (25), and the HPr protein was purified as follows. A crude extract was placed on a DEAE-Toyopearl 650M column equilibrated with buffer A. After the column had been washed with buffer A, the HPr protein was eluted with a linear NaCl concentration gradient (0 to 300 mM). The eluted fractions were pooled and dialyzed against buffer A. The His-tagged HPrK protein was purified on a Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA)–agarose column (Qiagen). A crude extract was placed on Ni-NTA–agarose equilibrated with 10 mM Tris-Cl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 10% (vol/vol) glycerol. After the column had been washed with the same buffer, the His-tagged HPrK protein was eluted with the same buffer containing 300 mM imidazole. The eluted fractions were pooled and dialyzed against buffer A.

Phosphorylation of HPr and purification of P-Ser-HPr.

Phosphorylation of HPr by the His-tagged HPr kinase was carried out as reported previously (26). Phosphorylation of HPr was confirmed by native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (27). The reaction mixture containing P-Ser-HPr and His-tagged HPr kinase was placed on an Ni-NTA–agarose column equilibrated with 10 mM Tris-Cl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 10% (vol/vol) glycerol. The flowthrough fractions containing P-Ser-HPr were pooled and dialyzed against buffer A.

In vitro transcription.

The B. subtilis RNAP holoenzyme, containing a six-histidine fusion of the C terminus of the β′-subunit, was isolated as reported elsewhere (28). In vitro transcription was performed essentially as described previously (29, 30). The reaction mixtures comprised 1 nM DNA template, 40 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin, and 150 mM KCl; the DNA template was prepared by PCR using DNA of strain FU676 as a template and primer pair cat/lac-F and cat/lac-R (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). After CcpA and P-Ser-HPr, purified as described above, had been added, the reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 10 min. RNAP was then added to a concentration of 0.4 μg μl−1, and the incubations continued for 10 min. Transcription was initiated by the addition of nucleotide triphoshates (final concentrations of 200 mM ATP, 200 mM GTP, 200 mM CTP, 10 mM UTP, and 2 mM [α-32P]UTP [MP Biochemicals]), and then the reactions were allowed to proceed for 10 min. The reactions were terminated by the addition of an equal volume of formamide loading buffer (80% [vol/vol] formamide, 0.1% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate, 8% [vol/vol] glycerol, 8 mM Na-EDTA, 0.05% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue, and 0.05% [wt/vol] xylene cyanol). The reaction products were fractionated by electrophoresis on 7.5 M urea and 8% polyacrylamide gels.

DNase I footprinting.

DNase I footprinting experiments were performed essentially as described previously (31, 32). The ilv-leu probe (nt −248/+26) for footprinting of the CcpA and P-Ser-HPr, CodY, and TnrA proteins was prepared by PCR with DNA of strain 168 as a template and primer pair FP-F/FP-R (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Prior to PCR amplification, the 5′ end of the FP-F primer was radiolabeled as described previously (6).

lacZ fusion analysis to monitor ilv-leu promoter activity.

B. subtilis cells were inoculated into 50 ml of glucose minimal (GM) medium containing 13.6 mM Na-glutamate (nitrogen-limited medium) or 0.2% Na-glutamime and 16 amino acids (AA-rich medium) (6, 33) to give an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1, and then incubated at 37°C. During cell growth with shaking, 1-ml aliquots of the culture were withdrawn at 1-h intervals, and the β-galactosidase (β-Gal) activity was measured spectrophotometrically as described previously (34).

RESULTS

CcpA-mediated CA of the ilv-leu operon and its negation by CodY binding to a promoter-proximal high-affinity binding site (CodY-I+II).

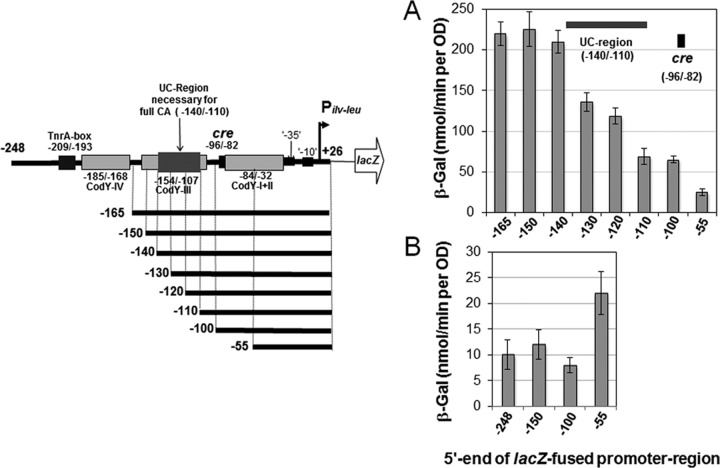

The ilv-leu operon undergoes CA mediated by the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr (5, 6). A cre site for this CA was identified at nt −96/−82, approximately 55 nt upstream of the −35 region of Pilv-leu (Fig. 1 and 2) (5, 6). The CcpA-mediated CA occurred fully in strain FU715 containing a lacZ fusion with the Pilv-leu region (nt −150/+26) including the cre site as well as the UC region upstream of cre under nitrogen-limited growth conditions using GM medium containing Na-glutamate (see Materials and Methods) and only partially in strain FU716 containing a fusion with the Pilv-leu region (nt −100/+26) not including the UC region but including cre (6). In order to identify the UC region necessary for full CA, we constructed a series of lacZ fusion strains: [FU1179 (−140), FU1178 (−130), FU1177 (−120), and FU1176 (−110)] with various lengths of the Pilv-leu region (nt −140/+26, −130/+26, −120/+26, and −110/+26), respectively, besides strains FU714 (−165), FU715 (−150), FU716 (−100), and FU717 (−55)] (nt −165/+26, −150/+26, −100/+26, and −55/+26) constructed previously (6) (Fig. 2). To carry out deletion analysis of the Pilv-leu region (nt −165/+26) necessary for CA, these lacZ fusion strains were grown under nitrogen-limited growth conditions, and β-Gal synthesis was monitored (Fig. 2A). (TnrA does not repress lacZ expression in the lacZ fusions deficient in the TnrA box, because TnrA-mediated negative regulation is cis-acting [6].) The result revealed that CA of ilv-leu almost fully occurred when the UC region between nt −140 and −110 was included besides the cre site (Fig. 2A); the average level of β-Gal synthesized in the cells of strains FU714 (−165), FU715 (−150), and FU1179 (−140) was roughly 3-fold higher than that in strains FU1176 (−110) and FU716 (−100). (Note that this UC region [31 bp] was longer than that estimated below.) The partial occurrence of CA of ilv-leu without the UC region resembled the case of CA of ackA (35). The UC region necessary for CA of ackA is not required for binding of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr itself to its cre but has functions in full CA of ackA through an unknown molecular mechanism (35).

FIG 2.

Deletion analysis of the ilv-leu promoter region to determine a region necessary for CA of ilv-leu upstream of the cre site (UC region). (A) Cells of strains FU714 (−165), FU715 (−150), FU1179 (−140), FU1178 (−130), FU1177 (−120), FU1176 (−110), FU716 (−100), and FU717 (−55) carrying a lacZ fusion of various promoter regions (nt −165, −150, −140, −130, −120, −110, −100, and −55 to +26) in amyE, respectively, were grown to an OD600 of 0.5 under nitrogen-limited conditions, and then β-Gal activity in crude cell extracts was measured. The average β-Gal activities (with standard deviations), which were obtained from at least two independent lacZ monitoring experiments, are shown. The promoter region (nt −55/+26) does not contain the cre site, whereas the others contain cre and various lengths of a region upstream of cre. The region upstream of cre necessary for full CA of ilv-leu (UC region) is indicated. (B) Cells of strains FU676 (nt −248/+26, −248), FU715 (−150), FU716 (−100), and FU717 (−55) were grown under AA-rich growth conditions, and then β-Gal activity in crude cell extracts was measured.

CodY interacts with the high-affinity binding sites CodY-I (nt −42/−32) and CodY-II (−84/−52) and with the low-affinity binding sites CodY-III (nt −154/−107) and CodY-IV (−185/−168)] in the Pilv-leu region (nt −248/+26) (Fig. 1) (17). However, the CodY-I and -II sites are unlikely separate (14), so they were combined as the high-affinity binding site CodY-I+II (nt −84/−32). The cre site partially overlaps the CodY-I+II site. Under AA-rich growth conditions using GM medium containing Na-glutamine plus 16 AAs (see Materials and Methods), CA is supposed to occur in the absence of free TnrA and negated by transcription repression that is exerted by CodY (6), whose corepressor is BCAAs such as isoleucine and GTP (15, 17). However, contrary to our data (6), it has been argued that the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr, which binds to the cre site, stimulates transcription significantly only when CodY is present, suggesting that the complex acts primarily by interfering with CodY repression (5). Subsequently, Brinsmade et al. (36) communicated that CcpA acts as a positive regulator of ilv-leu, which was inferred from the results showing that CcpA still has a significant positive effect on ilv-leu transcription when the interaction between CodY and the high-affinity CodY-I+II site is perturbed or even when CodY is eliminated from the cell.

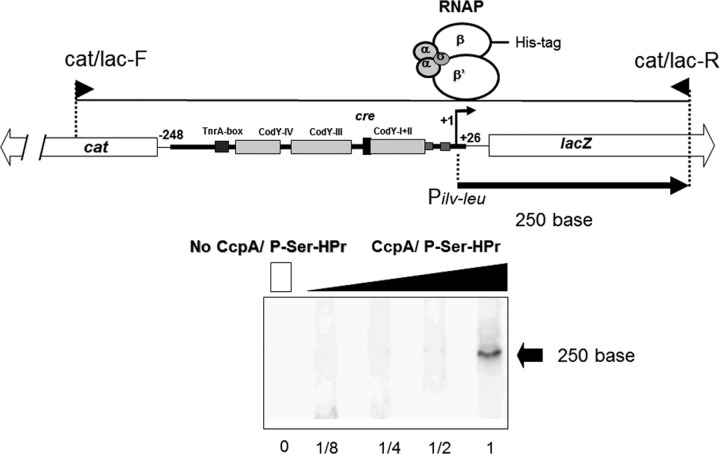

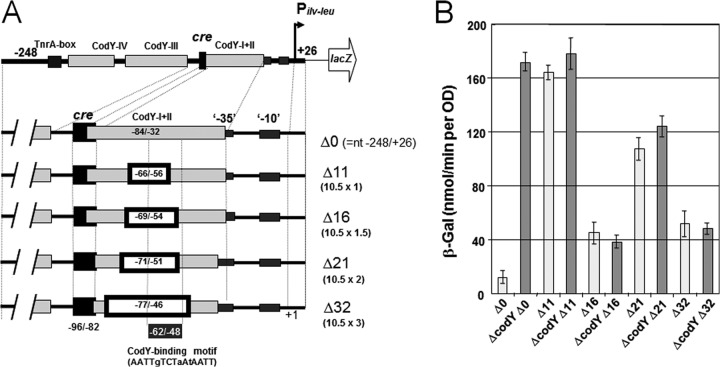

In order to demonstrate that CA of ilv-leu occurs in the absence of CodY, we first constructed an in vitro transcription system using a DNA fragment carrying Pilv-leu (nt −248/+26) and part of lacZ, and RNAP, whose RpoC is His tagged (28) (Fig. 3). This in vitro transcription activation was observed when only CcpA and P-Ser-HPr were added, clearly indicating that CA occurs in the absence of CodY. Then, we examined the helix face dependence of the interaction of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr with RNAP for CA, as performed for CA of ackA by using lacZ fusions (37). As one turn of the DNA helix is 10.5 bases, we introduced deletions of 11 nt (Δ11 [10.5 × 1], 16 nt (Δ16 [10.5 × 1.5]), 21 nt (Δ21 [10.5 × 2]), and 32 nt (Δ32 [10.5 × 3]) between the cre site and −35 region of Pilv-leu (Fig. 4A). The center of these deletions is nt −61, which is located in the CodY-binding motif of ilv-leu, AATTgTCTaAtAATT (nt −62/−48) (Fig. 4A), which comprises the left-hand side of the overlapping sequence motif (AATTgTCTaAtAATTtTaAAAAaT; nt −62/−39) (13) (mismatches are indicated by lowercase letters and are in comparison with the consensus sequence, AATTTTCWGAAAATT [12]). β-Gal synthesis in cells of strain FU676 carrying Pilv-leu (−248/+26)-lacZ (no deletion; Δ0), grown under AA-rich conditions, was derepressed 15-fold by the introduction of ΔcodY, as observed for strain FU735 carrying Pilv-leu (−248/+26)-lacZ and ΔcodY (Fig. 4B, Δ0 columns). The β-Gal synthesis was not repressed by CodY in cells carrying the Δ11, Δ16, Δ21, or Δ32 deletion, because these deletions disrupted the above CodY-binding motif, which is likely essential for CodY binding to the CodY-I+II site, thereby repressing lacZ expression. Actually, the helix face-dependent interaction of CcpA with RNAP for activation of lacZ expression was detected, as seen in Fig. 4B. lacZ expression gradually decreased with the decrease in helical turns between the cre site and −35 region, that is, the Δ11 (one-turn), Δ21 (two-turn), and Δ32 (three-turn) deletions, in the backgrounds of both CodY+ and CodY− (ΔcodY). However, lacZ expression in the Δ16 deletion (1.5-turn) strain was exceptionally low in comparison to those in strains carrying the Δ11, Δ21, and Δ32 deletions in both the CodY+ and CodY− backgrounds. Thus, CA of ilv-leu by the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr, which was dependent on the helix face, is highly likely exerted in the same manner as for CA of ackA (37), which is also observed in the absence of CodY (18).

FIG 3.

CA of in vitro transcription from the ilv-leu promoter. The in vitro transcription was performed as described in the text. In vitro transcription with the DNA template carrying Pilv-leu (nt −246/+26) and part of lacZ produced a 250-base runoff transcript. The lanes (1, 1/2, 1/4, and 1/8) contained stepwise-diluted CcpA and P-Ser-HPr solutions, whereas lane 0 contained neither CcpA nor P-Ser-HPr; the most right-hand lane 1 (no dilution) contained CcpA (3.0 μM as a dimer) and P-Ser-HPr (3.7 μM).

FIG 4.

Helix face-dependent interaction of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr with RNAP for CA of ilv-leu. (A) Strains FU676, FU846, FU849, FU847, and FU848 carried lacZ fusions with the ilv-leu promoter region (−248/+26) possessing Δ0 (no deletion), Δ11, Δ16, Δ21, and Δ32, respectively, whose deletion centers were at nt −61 inside CodY-I+II. Strains FU735, FU861, FU864, FU862, and FU863 carry Δ0, Δ11, Δ16, Δ21, and Δ32, respectively, in the ΔcodY genetic background. The CodY-binding motif is shown at the bottom. (B) The cells of these strains were grown to an OD600 of 0.5 under AA-rich conditions, and then β-Gal activity in crude cell extracts was measured and plotted.

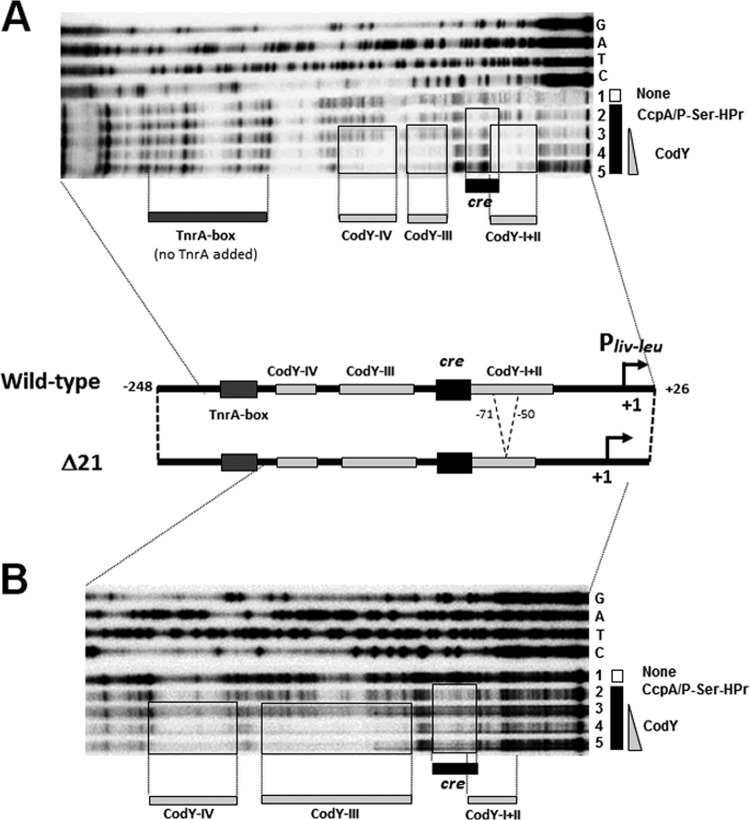

Actually, CodY protected the CodY-I+II, -III, and -IV sites on footprinting of the wild-type Pilv-leu region (nt −248/+26) (Fig. 5A). But CodY was not found to protect the CodY-I+II site against DNase I on footprinting of the Pilv-leu region carrying the Δ21 deletion (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, CodY was found to protect the CodY-III and -IV sites against DNase I on the latter footprinting analyses, indicating that CodY binding to the CodY-III and -IV sites was separable from CodY binding to the CodY-I+II site. As observed via footprinting analysis of both CodY and the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr in the wild-type region (Fig. 5A), CodY binding to the CodY-binding sites competitively inhibited the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr bound to the cre site and resulted in its release from cre. However, CodY was not found to overcome the binding of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr on footprinting of the Pilv-leu region carrying the Δ21 deletion, due to inability of CodY to bind to the CodY-I+II site (Fig. 5B). Shivers and Sonenshein communicated previously that the competitive binding of CodY to the CodY-I+II site overcame the binding of His-tagged CcpA to cre (5). lacZ expression under the control of Pilv-leu in the wild-type background decreased nearly 15-fold through CodY-mediated negative regulation, in comparison with that in the ΔcodY background (Fig. 4B, two Δ0 columns). However, lacZ expression under the control of Pilv-leu carrying Δ21 only slightly decreased in the wild-type background in comparison with that in the ΔcodY background (Fig. 4B, two Δ21 columns). These overall in vitro and in vivo results suggest that Pilv-leu is catabolite activated for the binding of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr to the cre site under AA-rich growth conditions when CodY is inactive, which could be competitively displaced by CodY binding to the CodY-I+II site to minimize CA of ilv-leu.

FIG 5.

DNase I footprinting analysis of competition of binding of CodY to CodY-I+II with that of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr to cre. The footprinting experiments were carried out as described in the text. (A) The probe DNA (wild type) was the ilv-leu promoter fragment (nt −248/+26). The gel is a DNase I footprint of the 5′-end-labeled coding strand. Binding of CcpA/P-Ser-HPr to cre and CodY to its sites was carried out in the presence of 2 mM GTP and 10 mM (each) isoleucine, valine, and leucine, with constant concentrations of CcpA (3.0 μM) and P-Ser-HPr (3.7 μM), as described in the text. Lane 1 contained no protein. Lanes 2, 3, 4, and 5 contained 0, 125, 250, and 500 nM CodY. Lanes G, A, T, and C contained the products of the corresponding sequencing reactions performed with the same primers as those used for the probe preparations. The protected areas of the cre sequence and CodY-I+II to CodY-IV sites are enclosed in boxes. (B) The probe DNA (Δ21) was the ilv-leu promoter fragment (nt −248/+26) carrying the Δ21 (nt −72/−52) deletion. The gel is a DNase I footprint of the 5′-end-labeled coding strand. The respective conditions for protection of CodY sites and the cre site by CodY and of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr are shown in panel A. The assignment of lanes (G, A, T, C, and lanes 1 to 5) was the same as that for panel A.

It is interesting that lacZ expression from the Pilv-leuregion (nt −55/+26) without the cre site and the CodY-I+II site necessary for CodY repression was 2.2-fold higher than that from the longer Pilv-leu regions (nt −248, −150, and −100/+26) in the wild-type background (Fig. 2B), indicating that CodY binding to the CodY-I+II site not only negates CA but also likely interferes with transcription initiation from Pilv-leu, through steric hindrance.

CcpA-mediated CA and its negation by TnrA bound to the TnrA box.

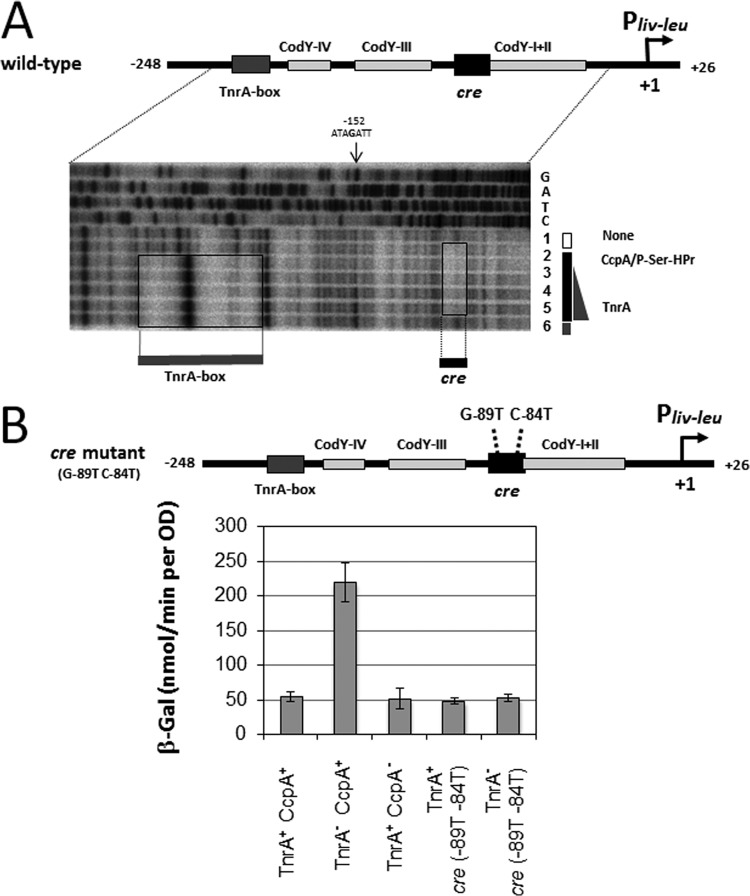

As described above, full CcpA-mediated CA of ilv-leu required not only the cre site (6) but also the UC region (Fig. 2). This CA of the ilv-leu operon is also negated by TnrA through its binding to the TnrA box located at nt −209/−193 (Fig. 1) (not nt −211/−195, as incorrectly described in reference 10) in cells grown under nitrogen-limited conditions (10). It was assumed that this TnrA-mediated negative regulation to negate CA might occur through an interaction of TnrA bound to the TnrA box with the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr bound to the cre site (6). Footprinting revealed that TnrA is bound to the TnrA box, which was independent of the binding of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser HPr to the cre site, that is, both the TnrA protein and the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr were able to simultaneously bind to their binding sites (Fig. 6A). TnrA binding to the TnrA box itself likely induces DNA bending without binding of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr, whose probable center at nt −152 becomes hyper-DNase I-sensitive upon TnrA binding to its box (Fig. 6A). This DNA bending supports the idea that interference by TnrA in CcpA-mediated CA could occur via looping and a direct interaction between TnrA and CcpA.

FIG 6.

DNase I footprinting analysis of simultaneous binding of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr to cre with that of TnrA to its box. The footprinting experiments were carried out as described in the text. (A) The probe DNA (wild type) was the ilv-leu promoter fragment (nt −248/+26). The gel is a DNase I footprint of the 5′-end-labeled coding strand. Simultaneous binding of CcpA/P-Ser-HPr to cre and TnrA to its site was carried out at constant concentrations of CcpA (3.0 μM) and P-Ser-HPr (3.7 μM). Lane 1 contained no protein. Lanes 2, 3, 4, and 5 contained 0, 50, 100, and 200 nM TnrA. Lanes G, A, T, and C contained the products of the corresponding sequencing reactions performed with the same primers as those used for the probe preparation. The protected areas of the cre sequence and TnrA box are enclosed in boxes. (B) Cells of strains FU676, FU679 (tnrA::Tn917), FU731 (ccpA::neo), FU722 [cre (G-89T C-84T)], and FU724 [tnrA::Tn917 cre (G-89T C-84T)] carrying the lacZ fusion of the Pilv-leu region (nt −248/+26) were grown to an OD600 of 0.5 under nitrogen-limited conditions, and then β-Gal activity in crude cell extracts was measured.

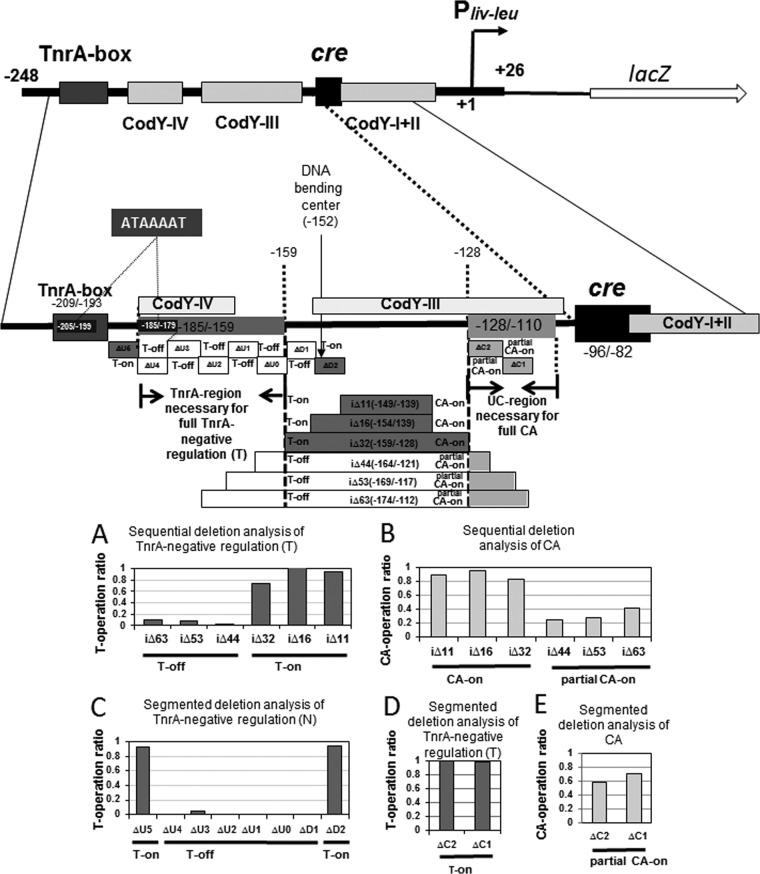

In order to investigate the nature of the TnrA-mediated negative regulation of CA, we first created a series of sequential internal deletions: iΔ11 (nt −149/−139), iΔ16 (nt −154/−139), iΔ32 (nt −159/−128), iΔ44 (nt −164/−121), iΔ53 (nt −169/−117), and iΔ63 (nt −174/−112), between the cre site and the TnrA box in the Pilv-leu region (nt −248/+26) (Fig. 7). β-Gal synthesis in cells of strains FU870, FU856, FU871, FU873, FU874, and FU888, carrying the respective deletions and ΔtnrA, was monitored during growth under nitrogen-limited conditions (Fig. 7B). The CodY-mediated negative regulation of Pilv-leu does not occur under these growth conditions, so only CcpA-mediated CA can be measured. As shown in Fig. 7B, full CA was observed in the iΔ11, iΔ16, and iΔ32 cells, but only partial CA was observed in the iΔ44, iΔ53, and iΔ63 cells. The results suggest that the UC region (nt −128/−110) necessary for full CA is significantly shorter than that assigned above (nt −140/−110). This discrepancy is likely due to differences in the DNA sequences flanking the deletion endpoint. Here the UC region is designated as a shorter region (nt −128/−110). Then, we constructed internal deletions of 5 nt, ΔC1 (nt −123/−119) and ΔC2 (nt −128/−124), in the UC region (nt −128/−110), and β-Gal synthesis in cells of strains FU1174 and FU1175, carrying the respective internal deletions and ΔtnrA, was monitored during their growth under nitrogen-limited conditions, which indicated that these internal regions (ΔC1 and ΔC2) partially affected CcpA-mediated CA (Fig. 7E). The overall deletion analysis indicated that full CA requires the UC region (nt −128/−110) as well as the cre site.

FIG 7.

Sequential and segmented deletion analysis of the regions necessary for full CA and TnrA-negative regulation between the TnrA box and cre site. The cre and CodY sites and the TnrA box as well as the UC and TnrA regions are indicated in the Pilv-leu region (nt −248/+26). A 7-nt direct repeat, ATAAAAT, was found inside the TnrA box and the most upstream part of the TnrA region, which is likely required for TnrA-mediated negative regulation. (A) Sequential deletion analysis of TnrA-negative regulation. Cells of strains FU676, FU865, FU854, FU866, FU868, FU869, and FU887 carried no deletion, iΔ11, iΔ16, iΔ32, iΔ42, iΔ53, and iΔ63, respectively, in the Pilv-leu region (nt −248/+26), which is fused with lacZ. These strains together with strain FU679 carrying the lacZ fusion (no deletion) and a disrupted tnrA gene were grown to an OD600 of 0.5 under nitrogen-limited conditions, and then β-Gal activity in crude cell extracts was measured. After subtraction of the value for strain FU676 (no deletion at nt −248/+26) from the values for all the internal deletion strains, including strain FU679 (tnrA), the plotted ratios were obtained by subtraction from 1 of the ratio obtained by dividing each subtracted β-Gal value with that of strain FU679 (tnrA). The average rations obtained from at least two independent lacZ-monitoring experiments had at most 10% errors. T-on and T-off denote TnrA-mediated negative regulation (N) was on or off, respectively. (B) Sequential deletion analysis of CA. Cells of lacZ fusion tnrA strains FU679, FU870, FU856, FU871, FU873, FU874, and FU888 carried no deletion, iΔ11, iΔ16, iΔ32, iΔ42, iΔ53, and iΔ63, respectively. These strains together with strain FU724 carrying cre mutations (G-89T C-84T) and tnrA were grown to an OD600 of 0.5 under nitrogen-limited conditions, and then β-Gal activity in crude cell extracts was measured. After subtraction of the β-Gal value for strain FU724 [tnrA cre (G-89T C-84T)] from the values for all the internal deletion strains, including strain FU679 (tnrA), the plotted ratios were obtained by dividing each subtracted value with that for strain FU679. (C) Segmented deletion analysis of the TnrA region downstream of the TnrA box essential for TnrA-negative regulation. Cells of strains FU676, FU1161, FU1160, FU1158, FU1157, FU1162, FU1170, FU1163, and FU1159 carried Δ0 (no deletion), ΔU5, ΔU4, ΔU3, ΔU2, ΔU1, ΔU0, ΔD1, and ΔD2, downstream of the TnrA box, respectively. These strains together with strain FU679 (tnrA) were grown under nitrogen-limited conditions, and then β-Gal activity in crude cell extracts was measured. The plotted ratios were obtained as for panel A. (D) Segmented deletion analysis of TnrA-negative regulation. Cells of strains FU676, FU1172, and FU1173 carried no deletion, ΔC1, and ΔC2, upstream of cre, respectively. These strains together with strain FU679 (tnrA) were grown, and then β-Gal activity in crude cell extracts was measured. The plotted ratios were obtained as described for panel A. (E) Segmented deletion analysis of CA. Cells of tnrA strains FU679, FU1174, and FU1175 carried no deletion, ΔC1, and ΔC2, respectively. These strains together with strain FU724 carrying cre mutations (G-89T C-89T) and tnrA were grown under nitrogen-limited conditions, and then β-Gal activity in crude cell extracts was measured. The plotted ratios were obtained as described for panel B.

Then, we attempted to determine the TnrA region that is necessary for TnrA-mediated negative regulation to negate CcpA-mediated CA, which likely involves the interaction of TnrA with the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr, both being bound to their binding sites, probably through DNA bending induced by binding of TnrA to its box. We first monitored β-Gal synthesis in cells of TnrA+ strains FU865, FU854, FU866, FU868, FU869, and FU887, carrying the above respective internal deletions (iΔ11, iΔ16, iΔ32, iΔ44, iΔ53, and iΔ63), under nitrogen-limited growth conditions to determine if these deletions affected TnrA-mediated negative regulation of ilv-leu (Fig. 7A). Full negative regulation was observed in the iΔ11 and iΔ16 cells, whereas this negative regulation significantly decreased in the iΔ32 cells. Moreover, the TnrA-mediated negative regulation was negligible in the iΔ44, iΔ53, and iΔ63 cells (Fig. 7A). The results indicated that the TnrA region upstream of iΔ32 (nt −159/−128) is necessary for this TnrA-mediated negative regulation.

Moreover, we constructed a series of segmented deletions of 5 or 7 nt downstream of the TnrA box: ΔU5 (nt −192/−186), ΔU4 (−185/−179), ΔU3 (−178/−174), ΔU2 (−173/−169), ΔU1 (−168/−164), ΔU0 (−163/−158), ΔD1 (−158/−154), and ΔD2 (−153/−149). Also, β-Gal synthesis in TnrA+ strains FU1161, FU1160, FU1158, FU1157, FU1162, FU1170, FU1163, and FU1159, carrying the respective deletions, was monitored during growth under nitrogen-limited conditions (Fig. 7C). Almost full TnrA-mediated negative regulation was observed in the cells carrying the ΔU5 or ΔD2 deletion, whereas this negative regulation was scarcely observed in the cells carrying each of the other deletions (ΔU4, ΔU3, ΔU2, ΔU1, ΔU0, or ΔD1). These results indicate that besides the TnrA box, the TnrA region (nt −185/−159) is necessary for TnrA-mediated negative regulation to negate CcpA-mediated CA. Furthermore, full TnrA-mediated negative regulation was observed even in cells carrying the ΔC1 or ΔC2 deletion in the UC region in the wild-type background (Fig. 7D), which partially affected CcpA-mediated CA (Fig. 7E).

Thus, the following conclusions can be drawn from the overall results with respect to TnrA-mediated negative regulation to negate CcpA-mediated CA of ilv-leu. The TnrA region downstream of the TnrA box (nt −185/−159) is essential for this TnrA-mediated negative regulation, which does not include the probable center (nt −152) for DNA bending induced by binding of TnrA to its box (Fig. 6A). This center shifts 7 nt upstream of a physical center (nt −145) between the TnrA box and cre site. This probable bending center is unlikely to be fixed, because the TnrA-negative regulation was conserved in deletion strains iΔ16 (nt −154/−139), iΔ32 (−159/−128), and ΔD2 (−153/−149), which are deficient in this center (Fig. 7).

TnrA-mediated negative regulation of ilv-leu does not depend on the helix face with the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr bound to the cre site, because deletions (a half turn or 1.5 turns) between the TnrA box and cre did not affect this negative regulation at all. Of course, it is highly possible that the distance between the TnrA box and the cre site is great enough that interaction occurs without the need for DNA-bound proteins occupying the same helix face.

We found an 8 bp-direct repeat, TATAAAAT (nt −206/−199), overlapping the TnrA box (nt −209/−193) and nt −186/−179 overlapping the most upstream part of the TnrA region (nt −185/−159). However, a 7-nt shift of the TnrA region essential for TnrA-mediated negative regulation toward the TnrA box on introduction of ΔU5 (nt −192/−186) did not affect this negative regulation, but a 7-bp deletion (ΔATAAAAT) upon introduction of ΔU4 (nt −185/−179) affected it thoroughly (Fig. 7C). This implied that a 7-bp direct repeat of ATAAAAT might be required for TnrA-mediated negative regulation, instead of the 8-bp direct repeat (TATAAAAT) (Fig. 7 and 8).

FIG 8.

The molecular mechanisms underlying CodY- and TnrA-negative regulation to negate CA exerted by the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr. The ilv-leu operon is catabolite activated in the presence of rapidly metabolizable carbon sources such as glucose through binding of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr to the cre sequence (nt −96/−82); P-Ser-HPr is formed by HPr kinase, which is activated by fructose-bisphosphate, whose concentration increases during growth on rapidly metabolizable carbon sources such as glucose (7). The UC region (nt −128/−110) is necessary for full CA, but its function in CA is unknown. The binding of the complex to cre is displaced by tight binding of CodY to the CodY-I+II (nt −84/−32) site; isoleucine and GTP are bound to CodY for its activation on cell growth under AA-rich conditions. On the other hand, CA might be negated by the putative interaction of TnrA bound to the TnrA box (nt −209/−193) with the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr to cre on DNA bending; TnrA becomes free in cells growing under nitrogen-limited conditions (11). Also, TnrA-negative regulation requires the TnrA region downstream of the TnrA box (nt −185/159), which likely has an unknown function in DNA bending for the interaction of TnrA and the complex. In addition, a direct repeat of ATAAAAT is shown in the TnrA box and region and is likely required for the TnrA-mediated negative regulation.

TnrA-mediated negative regulation completely blocked CcpA-mediated CA (Fig. 7A and C). Moreover, it completely blocked CcpA-mediated CA that had been only partially activated due to the introduction of a deletion (ΔC1 or ΔC2) into the UC region (Fig. 7D and E). However, this negative regulation is unlikely to inhibit Pilv-leu itself. This was inferred from the results with the lacZ fusion, as the β-Gal level in TnrA+ CcpA+ cells was almost the same as that in TnrA+ CcpA− cells and in TnrA+ cells carrying cre mutations in the lacZ fusion (G-89T C-84T) (Fig. 6B), whereas the β-Gal level was derepressed 4-fold in the TnrA− CcpA+ cells but the level in the TnrA+ cells carrying the cre mutations was not further increased by the introduction of tnrA62::Tn917, as observed in TnrA− cells carrying the cre mutations (Fig. 6B). This was probably due to the inability of TnrA when bound to its box to interfere with transcription initiation conducted by RNAP, even if DNA bending occurred.

DISCUSSION

The molecular mechanism underlying CcpA-mediated CA of the B. subtilis ilv-leu operon involves the binding of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr to the cre site and its negation by either CodY- or TnrA-mediated negative regulation under nitrogen-limited or AA-rich growth conditions (Fig. 8). CA of ilv-leu required the UC region (19 nt) for full activation (Fig. 2 and 7B and E). CodY-negative regulation negated CA through binding of CodY to the CodY-I+II site, which competitively overcame the binding of the complex to cre (Fig. 5A). TnrA-negative regulation of CA was likely to be exerted through interaction of TnrA bound to the TnrA box with the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr bound to cre. DNA bending that is essential for this interaction was induced by binding of TnrA to the TnrA box (Fig. 6A). The TnrA region (26 nt) downstream of the TnrA box, required for the negation of CA (Fig. 7A and C), might function in this DNA bending.

CcpA-mediated CA of the ilv-leu operon.

CcpA-mediated CA involving the cre site has so far been demonstrated clearly only for ackA (37), pta (38), and ilv-leu (5, 6). The pta and ackA genes encode a phosphotransferase and an acetate kinase, respectively, which catalyze the conversion of acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) to acetate, a major compound secreted during growth in carbon-rich medium, via an acetyl∼P intermediate. The cre sites of ackA (37) and pta (38) are, respectively, located at nt −64/−49 and −64/−50 with respect to their transcription initiation nucleotide position, although that of ilv-leu is at nt −96/−82 (5, 6). The cre site for ilv-leu is located approximately 32 nt (10.5 nt [one helix-turn] × 3) further upstream of pta and ackA. This means that CA of ilv-leu might reflect a helix face-dependent interaction of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr with RNAP, as CA tolerates a 10-nt insertion between the cre site of ackA and the −35 region of its promoter, in contrast to prevention of CA with a 5-nt insertion (37). Actually, CA of ilv-leu exhibited helix face dependence (Fig. 4), so it is highly likely that CA of ilv-leu is exerted in the same manner as that of ackA. Furthermore, deletion analysis of a region upstream of the cre site (Fig. 2A and 7B) suggested that the UC region, a 19-nt region upstream of the cre site (nt −128/−110) is necessary for full CA of ilv-leu, which is the same size as that of ackA, necessary for full CA (35). Recently, bacterial two-hybrid assays involving the combination of each RNAP subunit with CcpA localized CcpA binding to the α-subunit of RNAP (RpoA) (39). Moreover, surface plasmon resonance analysis confirmed the binding of CcpA to the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of RpoA (39). These findings strongly suggest that CcpA complexed with P-Ser-HPr, which is bound to each cre of ilv-leu, ackA, and pta, can interact with RpoA to exert CA in B. subtilis. However, we failed to find clear conserved sequence similarities between the UC regions of ackA, pta, and ilv-leu.

CodY-mediated negative regulation to negate CA of ilv-leu.

When B. subtilis cells are grown under AA-rich conditions, the CodY protein binds to the CodY-binding sites of anabolic and cellular process genes and operons such as ilv-leu (12–14), which are normally quiescent under such AA-rich conditions (15). A high concentration of GTP activates the CodY repressor. BCAAs, especially isoleucine, also activate CodY to repress the ilv-leu operon, which is considered to represent a feedback regulation of CodY by reaction products of the ilv-leu proteins (17). The promoter-proximal CodY-I+II (nt −84/−32) site is a high-affinity binding site of CodY (Fig. 1), while the promoter-distal CodY-III (nt −154/−107) and CodY-IV (−185/−168) sites are low-affinity ones (17). The CodY-I+II site overlaps the CodY-binding motif of ilv-leu, AATTgTCTaAtAATT (nt −62/−48) (12) (Fig. 4A), although the CodY-III and CodY-IV sites contain no such obvious CodY-binding motif (14). Actually, CodY was found not to protect the high-affinity CodY-I+II-binding site against DNase I based on footprint analysis of the Pilv-leu region carrying a deletion of Δ21 (Fig. 5B), but it still protected the low-affinity CodY-III and CodY-IV sites. At present, we cannot explain the physiological meaning of CodY binding to the low-affinity CodY-III- and CodY-IV-binding sites. Moreover, CodY binding to the CodY-I+II site competitively overcame the binding of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr to the cre site (nt −96/−82) (Fig. 5A), which most likely resulted in negation of CA.

The CodY protein controls, directly and indirectly, the expression of more than 100 anabolic and cellular process genes and operons, including ilv-leu (9, 14). Among them, only the ackA gene is activated by CodY, whose binding sites were identified by DNase I footprinting (18). Expression of the ackA gene is also under CcpA-mediated CA, as is that of ilv-leu; the cre2 site (main cre) of ackA is at nt −64/−49 (35, 37). Interestingly, the binding of His-tagged CcpA to the cre site and CodY to the CodY-II site (main site, nt −100/−61) synergistically activates the expression of ackA (18), contrary to the transcription repression of ilv-leu by CodY (6, 17). In contrast to this simultaneous binding of His-tagged CcpA to cre2 and CodY to CodY-II in the promoter region of ackA (18), CodY binding to the CodY-I+II site of ilv-leu overrode the binding of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr to cre (Fig. 5). The cre and CodY-binding sites of ilv-leu and ackA partially overlap. Therefore, this difference might reflect the mutual positioning of the cre and the CodY-binding sites; the cre site of ilv-leu is upstream of the CodY-I+II site, whereas the cre2 site of ackA is downstream of the CodY-II site. Recently, surface plasmon resonance analysis suggested that CodY and CcpA form a loose complex (39). Therefore, it is considered that this loose complex of CodY and CcpA, which both bind simultaneously to their very close binding sites on ackA in that order, can synergistically activate ackA transcription through the interaction of this complex with RpoA. However, the direct interaction between CodY and CcpA proteins may not play a role in the control of the ilv-leu operon. CodY binding to the CodY-I+II site partially overlapping the cre site competitively displaces the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr bound to cre. The binding affinity of CodY for the CodY-I+II site might be higher than that of the complex for cre.

TnrA-mediated negative regulation to negate CA of the ilv-leu operon.

The CcpA-mediated CA of ilv-leu is also negatively regulated by TnrA through its binding to the TnrA box located at nt −209/−193 under nitrogen-limited conditions (10). The target genes and operons of the TnrA protein were roughly estimated at 25, including ilv-leu (10, 40). Among them, 16 genes and operons are activated by TnrA, whereas 10, including ilv-leu, are negatively regulated. The typical TnrA-activated genes and operons (nrgAB [ammonium transport], gabP [γ-aminobutylate transport], nas [nitrate and nitrite assimilation], asnZ [l-asparaginase], and ykzB-ykoL [unknown function]) all contain a TnrA box (TGTNANAWWWTMTNACA) centered 49 to 51 nt upstream of their transcription initiation sites, except for the TnrA box of the puc operon (purine catabolism), whose TnrA box is centered 105 nt downstream of its transcription initiation site. Transcriptional activation of nrgAB occurs, in part, through enhancement of the binding of RNAP to the promoter (40). It was postulated that the A+T-rich region upstream of the TnrA box of nrgAB might interact with the α-subunit of RNAP through DNA bending induced by TnrA binding to the TnrA box of nrgAB (40). Meanwhile, the well-known TnrA-repressed operons (glnRA [glutamine synthase] and gltAB [glutamate synthase]) possess TnrA boxes centered at nt −50 and −27 and at +14, respectively (41, 42). This positioning of TnrA might create steric hindrance for the exposure of RNAP to the promoters to initiate transcription. However, TnrA-repressed ilv-leu possesses a TnrA box centered at nt −201, which is far upstream of the transcription start site (10), implying that an unknown molecular mechanism underlies this transcription repression.

It was assumed that the TnrA-mediated negative regulation of ilv-leu might occur through interaction of TnrA bound to the TnrA box and the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr bound to the cre site (6). Footprinting revealed that both the TnrA protein and the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr are able to bind simultaneously to their binding sites (Fig. 6A). TnrA binding to the TnrA box itself could induce DNA bending without binding of the complex of CcpA and P-Ser-HPr, whose probable center at nt −152 becomes hyper-DNase I-sensitive upon TnrA binding to its box (Fig. 6A). Thus, it is likely that TnrA when bound to its box interacts with the complex bound to cre through DNA binding to negate CA of ilv-leu. And, it is highly possible that the TnrA region is required for DNA bending but not for TnrA binding to the TnrA box itself, because TnrA was able to bind to the DNA fragment carrying the TnrA box, which possesses only part of the TnrA region (10). To experimentally verify the interaction of TnrA with CcpA, yeast two-hybrid analysis has been extensively carried out, but unfortunately, no positive results were obtained (S. Fukushima and H. Yoshikawa, unpublished observation).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Nii, A. Yano, and M. Toratani for their help with the experiments.

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for the Strategic Support Project of Research Infrastructure Formation for Private University (S1001056) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan. This work was also supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant number 23380053.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 25 August 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.02055-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Mendoza D, Schujman GE, Aguilar PS. 2002. Biosynthesis and function of membrane lipids, p 43–55 In Sonenshein AL, Hoch JA, Losick R. (ed), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives: from genes to cells. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fink PS. 1993. Biosynthesis of the branched-chain amino acids, p 307–317 In Sonenshein AL, Hoch JA, Losick R. (ed), Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria; biochemistry, physiology, and molecular genetics. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grandoni JA, Zahler SA, Calvo JM. 1992. Transcriptional regulation of the ilv-leu operon of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 174:3212–3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ludwig H, Meinken C, Matin A, Stülke J. 2002. Insufficient expression of the ilv-leu operon encoding enzymes of branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis limits growth of a Bacillus subtilis ccpA mutant. J. Bacteriol. 184:5174–5178. 10.1128/JB.184.18.5174-5178.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shivers RP, Sonenshein AL. 2005. Bacillus subtilis ilvB operon: an intersection of global regulons. Mol. Microbiol. 56:1549–1559. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tojo S, Satomura T, Morisaki K, Deutscher J, Hirooka K, Fujita Y. 2005. Elaborate transcriptional regulation of the Bacillus subtilis ilv-leu operon involved in the biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids through global regulators of CcpA, CodY and TnrA. Mol. Microbiol. 56:1560–1573. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujita Y. 2009. Carbon catabolite control of the metabolic network in Bacillus subtilis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 73:245–259. 10.1271/bbb.80479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mäder U, Homuth G, Scharf C, Büttner K, Bode R, Hecker M. 2002. Transcriptome and proteome analysis of Bacillus subtilis gene expression modulated by amino acid availability. J. Bacteriol. 184:4288–4295. 10.1128/JB.184.15.4288-4295.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molle V, Nakaura Y, Shivers RP, Yamaguchi H, Losick R, Fujita Y, Sonenshein AL. 2003. Additional targets of the Bacillus subtilis global regulator CodY identified by chromatin immunoprecipitation and genome-wide transcript analysis. J. Bacteriol. 185:1911–1922. 10.1128/JB.185.6.1911-1922.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tojo S, Satomura T, Morisaki K, Yoshida K, Hirooka K, Fujita Y. 2004. Negative transcriptional regulation of the ilv-leu operon for biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids through the Bacillus subtilis global regulator TnrA. J. Bacteriol. 186:7971–7979. 10.1128/JB.186.23.7971-7979.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wray LV, Jr, Zalieckas JM, Fisher SH. 2001. Bacillus subtilis glutamine synthetase controls gene expression through a protein-protein interaction with transcription factor TnrA. Cell 107:427–435. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00572-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL. 2008. Genetic and biochemical analysis of CodY-binding sites in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 190:1224–1236. 10.1128/JB.01780-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wray LV, Jr, Fisher SH. 2011. Bacillus subtilis CodY operators contain overlapping CodY binding sites. J. Bacteriol. 193:4841–4848. 10.1128/JB.05258-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL. 2013. Genome-wide identification of Bacillus subtilis CodY-binding sites at single-nucleotide resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 23:7026–7031. 10.1073/pnas.1300428110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ratnayake-Lecamwasam M, Serror P, Wong KW, Sonenshein AL. 2001. Bacillus subtilis CodY represses early stationary phase genes by sensing GTP levels. Genes Dev. 15:1093–1103. 10.1101/gad.874201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kriel A, Bittner AN, Kim SH, Liu K, Tehranchi AK, Zou WY, Rendon S, Chen R, Tu BP, Wang JD. 2012. Direct regulation of GTP homeostasis by (p)ppGpp: a critical component of viability and stress resistance. Mol. Cell 48:231–241. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shivers RP, Sonenshein AL. 2004. Activation of the Bacillus subtilis global regulator CodY by direct interaction with branched-chain amino acids. Mol. Microbiol. 53:599–611. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shivers RP, Dineen SS, Sonenshein AL. 2006. Positive regulation of Bacillus subtilis ackA by CodY and CcpA: establishing a potential hierarchy in carbon flow. Mol. Microbiol. 62:811–822. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eymann C, Homuth G, Scharf C, Hecker M. 2002. Bacillus subtilis functional genomics: global characterization of the stringent response by proteome and transcriptome analysis. J. Bacteriol. 184:2500–2520. 10.1128/JB.184.9.2500-2520.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tojo S, Satomura T, Kumamoto K, Hirooka K, Fujita Y. 2008. Molecular mechanisms underlying the positive stringent response of the Bacillus subtilis ilv-leu operon, involved in the biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids. J. Bacteriol. 190:6134–6147. 10.1128/JB.00606-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krásný L, Tišerová H, Jonák J, Rejman D, Sanderová H. 2008. The identity of the transcription +1 position is crucial for changes in gene expression in response to amino acid starvation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 69:42–54. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miwa Y, Fujita Y. 2001. Involvement of two distinct catabolite-responsive elements in catabolite repression of the Bacillus subtilis myo-inositol (iol) operon. J. Bacteriol. 183:5877–5884. 10.1128/JB.183.20.5877-5884.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Satomura T, Shimura D, Asai K, Sadaie Y, Hirooka K, Fujita Y. 2005. Enhancement of glutamine utilization in Bacillus subtilis through the GlnK-GlnL two-component regulatory system. J. Bacteriol. 187:4813–4821. 10.1128/JB.187.14.4813-4821.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miwa Y, Saikawa M, Fujita Y. 1994. Possible function and some properties of the CcpA protein of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 140:2567–2575. 10.1099/00221287-140-10-2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galinier A, Kravanja M, Engelmann R, Hengstenberg W, Kilhoffer MC, Deutscher J, Haiech J. 1998. New protein kinase and protein phosphatase families mediate signal transduction in bacterial catabolite repression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:1823–1828. 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deutscher J, Kessler U, Hengstenberg W. 1985. Streptococcal phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system: purification and characterization of a phosphoprotein phosphatase which hydrolyzes the phosphoryl bond in seryl-phosphorylated histidine-containing protein. J. Bacteriol. 163:1203–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujita M, Sadaie Y. 1998. Rapid isolation of RNA polymerase from sporulating cells of Bacillus subtilis. Gene 221:185–190. 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miwa Y, Fujita Y. 1988. Purification and characterization of a repressor for the Bacillus subtilis gnt operon. J. Biol. Chem. 263:13252–13257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldfarb DS, Wong SL, Kudo T, Doi RH. 1983. A temporally regulated promoter from Bacillus subtilis is transcribed only by an RNA polymerase with a 37,000 dalton sigma factor. Mol. Gen. Genet. 191:319-325. 10.1007/BF00334833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujita Y, Miwa Y. 1989. Identification of an operator sequence for the Bacillus subtilis gnt operon. J. Biol. Chem. 264:4201–4206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshida K, Ohki Y, Murata M, Kinehara M, Matsuoka H, Satomura T, Ohki R, Kumano M, Yamane K, Fujita Y. 2004. Bacillus subtilis LmrA is a repressor of the lmrAB and yxaGH operons: identification of its binding site and functional analysis of lmrB and yxaGH. J. Bacteriol. 186:5640–5648. 10.1128/JB.186.17.5640-5648.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atkinson MR, Wray LV, Jr, Fisher SH. 1990. Regulation of histidine and proline degradation enzymes by amino acid availability in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 172:4758–4765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshida K, Ishio I, Nagakawa E, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto M, Fujita Y. 2000. Systematic study of gene expression and transcription organization in the gntZ-ywaA region of the Bacillus subtilis genome. Microbiology 146:573–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moir-Blais TR, Grundy FJ, Henkin TM. 2001. Transcriptional activation of the Bacillus subtilis ackA promoter requires sequences upstream of the CcpA binding site. J. Bacteriol. 183:2389–2393. 10.1128/JB.183.7.2389-2393.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brinsmade SR, Kleijn RJ, Sauer U, Sonenshein AL. 2010. Regulation of CodY activity through modulation of intracellular branched-chain amino acid pools. J. Bacteriol. 192:6357–6368. 10.1128/JB.00937-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turinsky AJ, Grundy FJ, Kim J, Chambliss GH, Henkin TM. 1998. Transcriptional activation of the Bacillus subtilis ackA gene requires sequences upstream of the promoter. J. Bacteriol. 180:5961–5967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Presecan-Siedel E, Galinier A, Longin R, Deutscher J, Danchin A, Glaser P, Martin-Verstraete I. 1999. Catabolite regulation of the pta gene as part of carbon flow pathways in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 181:6889–6897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wünsche A, Hammer E, Bartholomae M, Völker U, Burkovski A, Seidel G, Hillen W. 2012. CcpA forms complexes with CodY and RpoA in Bacillus subtilis. FEBS J. 279:2201–2214. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wray LV, Jr, Zalieckas JM, Fisher SH. 2000. Purification and in vitro activities of the Bacillus subtilis TnrA transcription factor. J. Mol. Biol. 300:29–40. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sierro N, Makita Y, de Hoon M, Nakai K. 2008. DBTBS: a database of transcriptional regulation in Bacillus subtilis containing upstream intergenic conservation information. Nucleic Acids Res. 36(Suppl 1):D93–D96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshida K, Yamaguchi H, Kinehara M, Ohki Y, Nakaura Y, Fujita Y. 2003. Identification of additional TnrA-regulated genes of Bacillus subtilis associated with a TnrA box. Mol. Microbiol. 49:157–165. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anagnostopoulos C, Spizizen J. 1961. Requirements for transformation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 81:741–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Serror P, Sonenshein AL. 1996. CodY is required for nutritional repression of Bacillus subtilis genetic competence. J. Bacteriol. 178:5910–5915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.