Abstract

Shiga-toxin producing Escherichia coli (STEC) is the etiologic agent of acute diarrhea, dysentery, and hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS). There is no approved vaccine for STEC infection in humans, and antibiotic use is contraindicated, as it promotes Shiga toxin production. In order to identify STEC-associated antigens and immunogenic proteins, outer membrane proteins (OMPs) were extracted from STEC O26:H11, O103, O113:H21, and O157:H7 strains, and commensal E. coli strain HS was used as a control. SDS-PAGE, two-dimensional-PAGE analysis, Western blot assays using sera from pediatric HUS patients and controls, and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–tandem time of flight analyses were used to identify 12 immunogenic OMPs, some of which were not reactive with control sera. Importantly, seven of these proteins have not been previously reported to be immunogenic in STEC strains. Among these seven proteins, OmpT and Cah displayed IgG and IgA reactivity with sera from HUS patients. Genes encoding these two proteins were present in a majority of STEC strains. Knowledge of the antigens produced during infection of the host and the immune response to those antigens will be important for future vaccine development.

INTRODUCTION

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) is emerging globally as a leading zoonotic pathogen associated with food-borne illnesses. STEC is an etiologic agent of acute diarrhea, dysentery, and hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS). The primary animal reservoir of STEC is cattle, and infection can result from contaminated water or food, such as meat products, prepared leafy green salads, unpasteurized milk, and fruit juices (1–3). O157:H7 is the most common serotype associated with sporadic outbreaks of dysenteric diarrhea and severe HUS cases. Nevertheless, other STEC serogroups, such as O26, O103, and O113, have been also implicated in such outbreaks (4). The presence of virulence factors, such as the outer membrane protein intimin and its receptor, Tir, both of which are encoded by the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE), are considered risk factors for developing HUS (1, 5).

HUS, which has a high incidence in children less than 5 years of age (6), is the most severe consequence of STEC infection and is characterized by microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute renal insufficiency, which can progress to chronic renal failure (7). HUS treatment is primarily supportive, as there is no specific therapy for STEC infection. Antibiotics are contraindicated, as they may promote Shiga toxin (Stx) production and release (8), increasing the risk of developing HUS (9). Therefore, because the most deleterious effects of STEC are those resulting from Stx, efforts to develop therapies have focused on compounds that bind to Stx and block its action. However, treatments have been unsuccessful to date or have yet to be tested for clinical efficacy in humans (10–12).

Although the incidence of STEC infection appears to be low, the economic losses (at the individual or national level) associated with community outbreaks and the significant costs of hospitalization required for the management of HUS and its possible sequelae, in addition to a few cases of death, justify the effort to find suitable targets against this pathogen (6). In this context, targets of vaccines have been tested in animal models with various levels of success, albeit the lack of an animal model that accurately reproduces the clinical profile of infection in humans is a considerable barrier (13). Some candidates have included recombinant Stx, intimin, EspA (14), chimeric proteins constructed by fusing the A and B subunits of Stx1 and Stx2 (15), and avirulent O157:H7 strains (16). The most promising vaccine candidate tested in humans was based on the covalent fusion of the E. coli O157:H7 O-specific polysaccharide and recombinant Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A (O157-rEPA). A phase I trial conducted with adults and a phase II trial conducted with children were completed in 2006 and showed the vaccine candidate to be safe and immunogenic, but to date, phase III trials have not been initiated (17). Overall, these efforts have mainly targeted O157 and have disregarded non-O157 serogroups; as a result, such vaccines would provide incomplete coverage against STEC infections. Moreover, characterization of STEC antigens has focused on the O157 serogroup. Reports have described a humoral immune response in patients infected with these bacteria against the lipopolysaccharide (LPS), Stx (18), flagellin (FliC-H7) (19), and antigens encoded in the LEE locus, which, apart from intimin and Tir, include EspA, EspB, and EspD (20–22). While identifying these proteins may lead to a vaccine with improved coverage, protection would still be limited mainly to the STEC LEE-positive serogroups. Therefore, it is important to identify antigens and immunogenic proteins conserved in a wide variety of STEC strains and capable of providing broader coverage. Immunoproteomics (two-dimensional [2D]-PAGE, mass spectrometry, and Western blotting), using serum from infected patients, has proved useful in the identification of proteins that are synthesized in vivo during infection and that stimulate the host's humoral immune response, and some of these proteins have been shown to have long-lasting effects (23–26).

In the present study, we were able to identify STEC-associated immunogenic antigens recognized by human IgG and IgA by means of immunoproteomic analysis of outer membrane protein (OMP) extracts. A total of 12 immunogenic STEC proteins were identified, and 7 of these are novel antigen candidates. These seven proteins include OmpT and Cah, which displayed IgG and IgA reactivity with sera from HUS patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The STEC strains were clinical isolates characterized using PCR and were serotyped by the Chilean Institute of Public Health and the Enteropathogen Laboratory, Microbiology and Mycology Program, School of Medicine at the University of Chile. In order to exclude proteins that might generate cross-reactivity with commensal microbiota, the reference commensal E. coli HS strain (kindly provided by Myron Levine, University of Maryland) was used. A collection of 170 STEC isolates and 11 commensal E. coli isolates from human feces (which were PCR negative for known diarrheagenic pathotype virulence factors), described in Table S2 in the supplemental material, was used for detection of the frequency of the ompT gene, the antigen 43 (Ag43) gene, and the cah gene.

E. coli was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (tryptone [10 g/liter], NaCl [10 g/liter], yeast extract [5 g/liter]) at 37°C for 18 h with no agitation. Bacteriological agar in a final concentration of 1.5% (wt/vol) was added to prepare the solid media. The culture media were supplemented as needed with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and 1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). To perform α complementation, ampicillin (100 μg/ml), IPTG (50 μg/ml), and X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) (50 μg/ml) were added to the culture media.

OMP extraction.

OMP extracts were obtained as described by Rivas et al. (27) with minor modifications. Briefly, 2 liters of bacterial culture grown in LB medium was centrifuged at 9,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was washed and resuspended in a final volume of 5 ml solution containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO). Each suspension was sonicated on ice (40 cycles for 30 s with 30-s intervals, which allowed cooling). To remove the cells and cell debris, cell extracts were deposited in new tubes and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant (total protein extract) was treated with DNase-RNase at room temperature for 20 min and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The cytoplasmic membrane was solubilized by incubating the supernatant with N-lauroyl sarcosine (Sarkosyl; Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) at 2% for 30 min at 25°C, and the mixture was centrifuged at 20,500 × g for 80 min at 4°C. Next, the pellet was washed with 1 ml of sterile Milli-Q water plus PMSF (1 mM) and centrifuged at 20,500 × g for 50 min at 4°C. Finally, the pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of sterile Milli-Q water. The protein concentration in the outer membrane fraction was measured using the reactive Bradford protein assay dye reagent (Bio-Rad, USA) and standard bovine serum albumin (BSA) according to the manufacturer's directions. The OMP extracts were stored at −80°C until use.

Denaturing SDS-PAGE.

Eight micrograms of OMP samples from each strain was separated using 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) according to the method described by Laemmli (28), using a SE 600 Ruby Standard Dual Cool vertical unit (Amersham Biosciences, GE Healthcare). Precision Plus Protein Kaleidoscope standards (Bio-Rad) were used as molecular weight markers. Proteins were stained with either Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 (Bio-Rad, USA) or silver stain from a Silver Stain Plus kit (Bio-Rad, USA).

2D-PAGE.

Precast immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strips (13 cm, pH 4 to 7, linear; GE Healthcare) were rehydrated with 250 μl of DeStreak rehydration solution (GE Healthcare) containing IPG buffer, pH 4 to 7 (1%; GE Healthcare), 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 200 μg of OMPs for 16 h at room temperature according to the manufacturer's directions. The rehydrated strips were then subjected to isoelectric focusing (IEF) using an Ettan IPGphor isoelectric focusing system (GE Healthcare) at 20°C with a current limit of 50 μA/strip according to the following protocol: 200 V for 1 h, 500 V for 1 h, 1,000-V gradient for 1 h, 8,000-V gradient for 3 h 30 min, and finally, 8,000 V until the focusing reached 20 kV h. After IEF, the strips were equilibrated for 15 min in 3 ml of buffer I (Tris-HCl [50 mM, pH 8.8], urea [6 M], glycerol [30%, wt/vol], SDS [2%, wt/vol], DTT [10 mg/ml, wt/vol]) and then in 3 ml of buffer II for 15 min. Buffer II differed from buffer I in that it contained iodoacetamide (25 mg/ml) instead of DTT. Then, the strips were directly applied to 12% polyacrylamide gels. The second dimension was performed using an SE 600 Ruby Standard Dual Cool vertical unit (Amersham Biosciences, GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer′s directions. Electrophoresis was performed at a constant current of 5 mA/gel for 20 min, followed by 15 mA/gel for 9 h, until the bromophenol dye had run out of the gel. Following separation in the second dimension, the gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 (Bio-Rad, USA) and photographed, and the images were analyzed using BioNumerics 2D software (v6.6; Applied-Maths, Belgium). Precision Plus Protein Kaleidoscope standards (Bio-Rad, USA) were used as molecular weight markers.

Sera and IgG and IgA concentrations.

Sera were obtained from 10 pediatric patients (patients identified with the prefix HUS in the ID column in Table S3 in the supplemental material) in the convalescent phase who presented with prodromal diarrhea within 20 days prior to HUS diagnosis (HUS sera); these sera were collected from 1990 to 1993 and from 1999 to 2003 and were kindly provided by Valeria Prado. The sera were tested individually and were pooled; these are designated HUS antisera. As a control, a mixture was created from the sera from three patients with no history of HUS or episodes of STEC-associated diarrhea (control patient sera; patients identified with the prefix C in the ID column in Table S3 in the supplemental material). The sera were obtained from various health centers in Santiago, Chile, with the informed consent of the parents or legal guardians of all subjects. All procedures were approved by the local Ethics Committee of the University of Chile School of Medicine. Table S3 in the supplemental material shows the clinical history of each patient who donated serum used in this study. Furthermore, IgG and IgA concentrations in HUS and control sera were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with a protein detector ELISA kit (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories), according to the manufacturer's directions.

Protein transfer and immunodetection.

OMPs separated by SDS-PAGE and 2D-PAGE were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore, Germany) for 60 min at 100 V and 4°C using a Mini Trans-Blot cell system (Bio-Rad), according to the manufacturer's directions.

After transfer was completed, the nonspecific binding sites available on the membrane were saturated using a blocking solution (1× Tris-buffered saline [TBS], 0.0003% Tween 20, 2% BSA) for 1 h at room temperature. Next, the membranes were rinsed three times with 1× TBS–0.003% Tween 20 (TBS-T) solution for 5 min each time. Then, the membranes were incubated with agitation for 1 h in a blocking solution that contained the HUS or control sera diluted to 1:3,500. After 2 rinses with TBS-T solution for 10 min each time, the membranes were incubated with blocking solution containing anti-human IgG conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (Invitrogen, USA) diluted to 1:5,000 for 1 h at room temperature with agitation. The images were revealed with a nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (NBT-BCIP) chromogenic substrate kit (Invitrogen, USA), and the reaction was stopped with distilled water.

The seroreactivity of the recombinant OmpT (rOmpT) and Cah (rCah) proteins to IgG and IgA of the HUS and control sera was evaluated following the above-described protocol. However, when anti-human IgA secondary antibody conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (1:2,000) was used, the HUS and control sera were diluted to 1:1,000.

Identification of immunogenic proteins using mass spectrometry.

The proteins recognized by antibodies from HUS sera but not control sera or those present only in the STEC strains were cut from the SDS-polyacrylamide gels and 2D polyacrylamide gels that had been stained with Coomassie brilliant blue G-250. Other proteins that demonstrated immunodominance were also cut from the gels. These proteins were sent to the Mass Spectrometry Core at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (Galveston, Texas) for identification using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–tandem time of flight (MALDI-TOF/TOF) mass spectrometry. Each peptide fragment fingerprint was submitted to analysis with the MASCOT server (Matrix Science) in order to identify the protein by comparing it with the fingerprints of other protein fragments included in the database. The identities of rOmpT and rCah were also confirmed by MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry.

Bioinformatic analyses of the immunogenic proteins identified.

The subcellular localization of proteins was predicted using the pSORTb (v3.0) program (http://psort.org/) (29). Theoretical isoelectric points and molecular weights were determined by using the ExPASy Proteomics Server UniProt Knowledgebase (http://us.expasy.org/). The BLASTN algorithm (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) was used to evaluate the distribution of genes coding for each protein in other E. coli strains as well as in other bacterial species.

Frequencies of ompT, Ag43, and cah gene detection.

PCR (monoplex PCR) was used to determine the presence of the ompT, Ag43, and cah genes. Specific primers were designed using nucleotide sequences available in the GenBank database and the ClustalW algorithm for alignment (http://www.ebi.ac.uk), as well as the NCBI Primer-BLAST tool (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The specificity of each primer and the predicted PCR products were verified by comparison to the sequences in the GenBank database using the BLASTN program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and were also tested using reference strains (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). In addition, considering that the main difference between the Ag43 and cah genes is a 270-bp deletion in the coding region of Cah's α domain, primers targeting conserved regions that flank this deletion were designed in order to obtain two amplicons with different molecular weights. Table S4 in the supplemental material lists the primers used in this study. The amplification reactions were performed in a final volume of 25 μl that contained DNA template, 0.4 μM each primer, 5 μl of 5× GoTaq DNA polymerase buffer, 0.2 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Fermentas, Lithuania), and 1.25 U of GoTaq DNA polymerase (Promega, USA). The PCR conditions were specific for each pair of primers. The hybridization temperature was set as a function of the melting temperature of the primer, and the duration of the extension stage was set as a function of the DNA fragment length, generally 1 min/kb.

The frequency data obtained were subjected to a two-tailed Fisher's exact test with the significant level set at 95%.

Generation of recombinant OmpT and Cah proteins.

The coding sequences for OmpT and Cah were amplified from the reference E. coli strain O157:H7 EDL933, using the primers described in Table S4 in the supplemental material, which had recognition sites for the restriction enzymes NdeI and XhoI at the 5′ and 3′ gene termini, respectively. The PCR products were directly ligated to the vector pTZ57R/T (Fermentas, Lithuania) according to the manufacturer's directions to construct the vectors pTZ57R/T_ompT and pTZ57R/T_cah. These vectors were used to transform the laboratory strain E. coli DH5α, and clones were selected according to ampicillin resistance and α complementation. Sequencing was performed to confirm the correct cloning of the coding sequences (Macrogen, USA).

Plasmid DNA was extracted from the transformed E. coli DH5α strains and digested with the restriction enzymes NdeI and XhoI. The products of digestion were analyzed in 1% agarose gels, and ompT and cah were purified. These sequences were ligated to the expression vector pET15C (30), allowing the production of recombinant proteins under the control of the T7 phage promoter and with the histidine tag at the C terminus of each protein, to construct the vectors pET15C_ompT and pET15C_cah. These vectors were used to transform the E. coli DH5α and E. coli BL21(DE3) strains. E. coli BL21(DE3), as a control, was also transformed with an empty pET15C vector. The bacterial clones were selected according to ampicillin resistance and confirmed by PCR. The transformed E. coli BL21(DE3) strains were cultivated in LB broth supplemented with 100 μg/ml of ampicillin for 10 h at 37°C with agitation, and then synthesis of the recombinant proteins was induced for 4 h by supplementing the culture medium with 1 mM IPTG.

The recombinant proteins, rOmpT and rCah, were partially purified using immunoprecipitation with μMACS epitope tag protein isolation kits (Miltenyi Biotec, GmbH, Germany), according to the manufacturer's directions. Briefly, 5 μg of OMPs extracted from E. coli BL21(DE3)/pET15C_ompT or E. coli BL21(DE3)/pET15C_cah was suspended in 1 ml of lysis buffer (1 M NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.0]), and that suspension was mixed with 50 μl of anti-His tag microBeads. Each column was placed in the magnetic field of a μMACS separator and was prepared by applying 200 μl of lysis buffer. The solution (containing proteins) was incubated for 30 min on ice and then loaded onto the columns. Later, the columns were rinsed four times with 200 μl of wash buffer 1 (4 M NaCl, 1% IGEPAL CA-630 [formerly NP-40], 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.0]) and once with 100 μl of wash buffer 2 (20 mM Tris HCl [pH 7.5]). Seventy microliters of preheated (95°C) elution buffer (50 mM Tris HCl [pH 6.8], 50 mM DTT, 1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, 0.005% bromophenol blue, 10% glycerol) was added to the column. The eluate was collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the results were verified by MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry.

RESULTS

Differences between OMP profiles of STEC and E. coli HS strains.

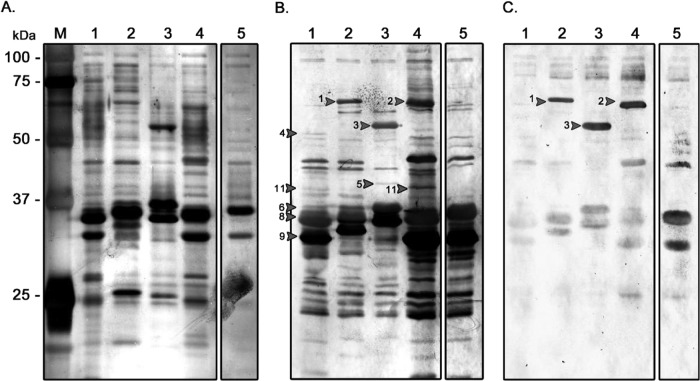

Exposed bacterial proteins are recognized as foreign antigens by the host immune system, and thus, OMPs may play an important role in immunogenicity and immunoprotection. Figure 1A shows the protein bands that were present in the STEC strains (lanes 1 to 4) but that were apparently absent from E. coli HS (lane 5). The molecular masses of these proteins were in the range of 37 to 75 kDa. In contrast, in all OMP profiles, the most abundant proteins were located close to 35 kDa, with minor variations in their electrophoretic mobilities being found. Due to limitations in resolution, as shown in Fig. 1A, it was difficult to identify each protein. Therefore, we performed 2D-PAGE to better discriminate OMPs on the basis of not only the molecular mass but also the isoelectric point.

FIG 1.

OMP profiles and OMP IgG seroreactivity with pooled sera from HUS patients and controls. (A) SDS-PAGE of OMPs. A 12% polyacrylamide gel and silver staining were used. (B and C) Western blot of 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels using pooled sera from HUS patients (B) and controls (C) (1:3,500 dilution). Anti-human IgG secondary antibodies were diluted 1:5,000. Lane M, protein ladder indicating the molecular masses of the various proteins; lanes 1, STEC O26:H11; lanes 2, STEC O103; lanes 3, STEC O113:H21; lanes 4, STEC O157:H7; lanes 5, E. coli HS. Arrows with numbers correspond to the proteins listed in Table 1.

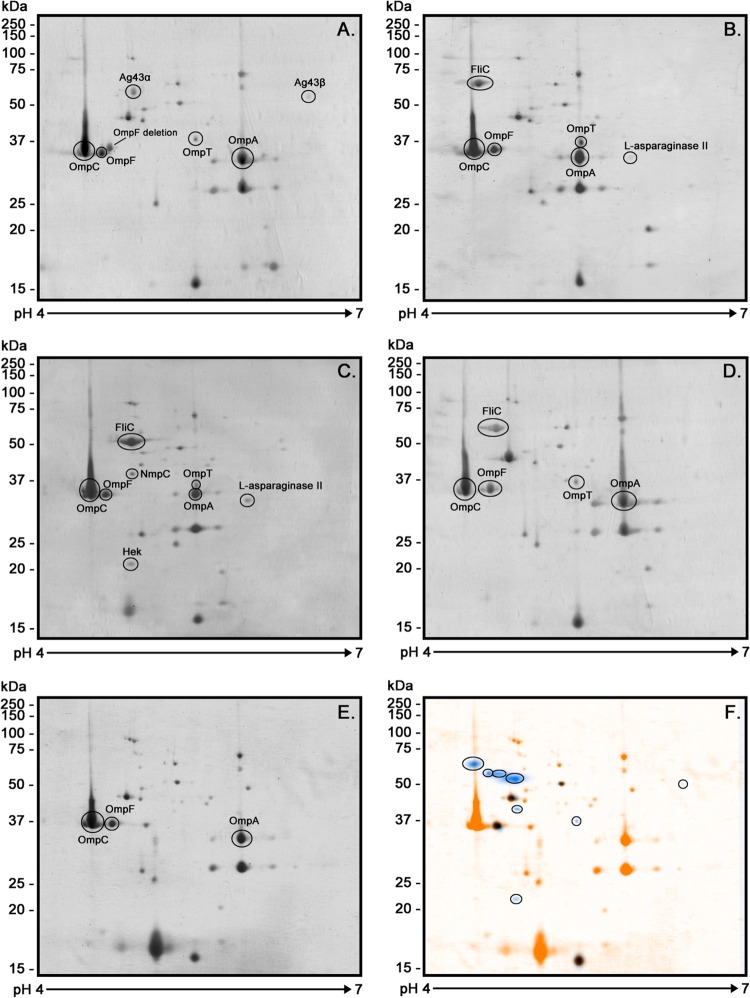

Because the literature suggests that most E. coli OMPs are best resolved at pH 4 to 7 (31, 32), the proteins were separated within this pH range on 2D gels, stained with Coomassie blue G-250, photographed, and analyzed using BioNumerics 2D software. An average of 47 spots was detected per strain (Fig. 2A to E). The software also provided a global OMP profile of the STEC strains analyzed. This profile was then superimposed on the OMP profile of the commensal E. coli HS strain in order to distinguish proteins unique to the STEC strains (Fig. 2F).

FIG 2.

2D-PAGE OMP profiles of STEC strains and E. coli HS. The pH range was 4 to 7, and 12% polyacrylamide gels and Coomassie blue G-250 stain were used. The images show the immunogenic proteins identified using MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry. (A) STEC O26:H11; (B) STEC O103; (C) STEC O113:H21; (D) STEC O157:H7; (E) E. coli HS. (F) Differences between OMP profiles of the STEC strains and E. coli HS. A unique OMP profile was identified for the STEC strains (blue) and was superimposed on the OMP profile of the E. coli HS strain (orange). Analysis was performed using BioNumerics 2D software (v6.6). The scale bars on the left indicate molecular masses.

Immunogenic OMPs associated with STEC.

ELISA showed that IgG and IgA concentrations did not differ significantly between HUS and control sera (unpublished observations). Pooled HUS sera recognized many of the OMPs, while the pooled control sera recognized only a minority of the OMPs or showed weak reactivity (Fig. 1B and C, respectively). Some of the STEC-associated proteins (proteins numbered 4, 5, 6, and 11 in Fig. 1B) were recognized by the HUS sera and not by the control sera, while other proteins (proteins numbered 1, 2, 3, 8, and 9 in Fig. 1B) were reactive with sera from both groups (Table 1). STEC-associated proteins that were seroreactive with HUS sera were extracted from the SDS-polyacrylamide and 2D polyacrylamide gels for identification by MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry. Other proteins with molecular masses between 32 and 37 kDa were also extracted, because despite their presence in all OMP profiles, they were strongly seroreactive with the HUS sera.

TABLE 1.

Immunogenic proteins identified by MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometryf

| Spot no.a | Protein | Best match (GenInfo Identifier sequence identification no.) | E valueb | pI/MWc |

Locationd | Strain | Reactivity with |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical | Experimental | HUS sera | Control sera | ||||||

| 1 | FliC | gi|191168280 | 3.6e−144 | 4.52/59,392 | 4.6/65,000 | F | O103 | + | + |

| 2 | FliC | gi|15831916 | 3.6e−144 | 4.70/59,953 | 4.8/62,000 | F | O157:H7 | + | + |

| 3 | FliC | gi|293446305 | 3.6e−118 | 4.83/51,502 | 5.0/54,000 | F | O113:H21 | + | + |

| 4 | Ag43 (α43) | gi|378084493 | 3.6e−96 | 5.6/106,853 | 4.9/53,000 | OM | O26:H11 | + | − |

| 4b | Ag43 (β43) | gi|388344126 | 1.8e−63 | 6.01/52,829 | 6.2/51,000 | OM | O26:H11 | + | − |

| 5 | NmpC | gi|33112659 | 5e−41 | 4.64/40,302 | 4.8/40,000 | OM | O113:H21 | + | − |

| 6 | OmpT | gi|193063338 | 1.4e−61 | 5.55/35,547 | 5.5/37,000 | OM | STEC | + | −/+e |

| 7 | OmpF | gi|157831181 | 2.3e−64 | 4.69/36,403 | 4.7/36,000 | OM | All | + | + |

| 8 | OmpC | gi|6650193 | 3.15e−70 | 4.55/40,499 | 4.5/36,000 | OM | All | + | + |

| 9 | OmpA | gi|71159604 | 3.97e−46 | 5.99/37,200 | 6.0/34,000 | OM | All | + | + |

| 10 | Hek | gi|331685335 | 5.7e−20 | 5.33/27,652 | 5.0/22,000 | OM | O113:H21 | + | − |

| 11 | EF-Tu | gi|323974212 | 1,9e−25 | 5.23/41,858 | 5.6/41,000 | C | O26:H11, O157:H7 | + | − |

| 12 | l-Asparaginase II | gi|229501 | 1,25e−15 | 5.02/34,087 | 5.9/34,000 | P | All | + | − |

Numbers correspond to the numbered proteins in Fig. 1.

Probability of erroneously assigning the protein identity.

The isoelectric point and theoretical molecular weight were determined using the ExPASy tool from the Proteomics Server UniProt Knowledgebase (http://us.expasy.org/).

Prediction was performed using the PSORTb (v3.0) program (http://www.psort.org/psortb/index.html).

OmpT was recognized by only one control serum sample using the recombinant protein (rOmpT).

OM, outer membrane; F, flagellum; C, cytoplasm; P, periplasm; pI, isoelectric point; MW, molecular weight.

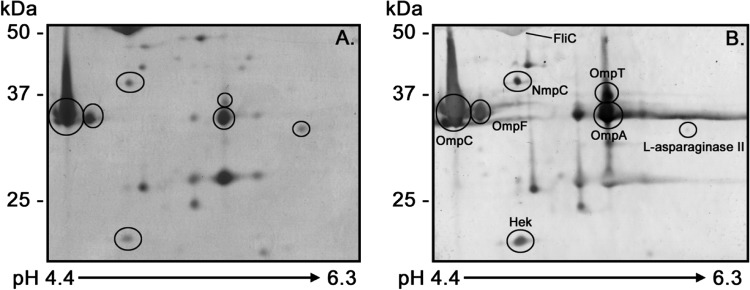

The immunogenic proteins identified by MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry are shown in Table 1. A total of 12 immunogenic proteins were identified, and some of these were present in multiple STEC OMP profiles. The porins OmpC, OmpF, and OmpA, ubiquitous in E. coli (Fig. 1A, and Fig. 2), were recognized by both HUS and control sera, although seroreactivity was weak in the latter group (Fig. 1B and C). The protein l-asparaginase II was observed only in the O103 and O113:H21 OMP profiles (Fig. 2B and C and 3); however, its molecular weight and isoelectric point coincided with those of the OmpA protein present in the other studied strains, possibly masking its presence. Recent results in our laboratories using anti-l-asparaginase II antibodies suggest that this protein is present in all OMP profiles (result not shown). However, it is noteworthy that this protein was seroreactive only with HUS sera (Fig. 3B). Flagellar (FliC) proteins were strongly recognized by both HUS and control sera numbered 1, 2, and 3 in Fig. 1B and C. Proteins Ag43 (the α subunit of Ag43 [α43]), NmpC, OmpT, and EF-Tu (numbered 4, 5, 6, and 11, respectively, in Fig. 1B) and the Hek protein (Fig. 3B), which were present in the STEC OMP profiles and not in the E. coli HS strain, were recognized only by HUS sera and therefore were classified as STEC-associated immunogenic proteins. The quantity of the proteins/spots observed and identified in OMP profiles is consistent with that found in other proteomics studies conducted with E. coli (24, 33, 34).

FIG 3.

Immunogenic proteins identified by 2D-PAGE and Western blot analysis. The O113:H11 OMP profiles on 12% polyacrylamide gels (A) and Western blots (B) using pooled sera from HUS patients (1:3,500 dilution) are shown. Anti-human IgG secondary antibodies were diluted 1:5,000. The scale bars on the left indicate molecular masses. The arrow at the bottom indicates the pH range of the separation.

In silico bioinformatics analysis of identified immunogenic proteins.

Bioinformatic analysis using PSORTb to predict the subcellular localization of immunogenic proteins indicated that EF-Tu and l-asparaginase II are cytoplasmic and periplasmic proteins, respectively. All other proteins were localized in the outer membrane (OM) or bacterial surface. In addition, cah, a homologue of Ag43, was identified in some STEC genomes but not in commensal E. coli genomes by BLAST analysis. This analysis suggests that cah is present in pathogenic E. coli strains but not in commensal E. coli strains (Table 2). However, this finding may be an artifact due to the low numbers of E. coli genomes sequenced to date.

TABLE 2.

Presence of Ag43 and cah in STEC and avirulent E. coli strains according to genome sequence analysis

| Strain | GenBank accession no. | Gene | Length (aad) | % identity/% similaritya | Scoreb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEC strains | |||||

| O157:H7 strain EDL933 | AAG55356.1 | cah | 1,005 | ||

| AAG55766.1 | cah | 1,005 | 100/100 | 5,574 | |

| O26:H11 strain 11368 | BAI24655.1 | cah | 1,005 | 100/100 | 5,568 |

| BAI26616.1 | cah | 948 | 90/93 | 3,855 | |

| BAI26126.1 | Ag43 | 1,039 | 68/73 | 1,589 | |

| BAI28612.1 | Ag43 | 1,039 | 68/73 | 1,589 | |

| O103:H2 strain 12009 | BAI33582.1 | cah | 948 | 90/93 | 3,749 |

| O104:H4 strain 2009EL-2071 | AFS88769.1 | cah | 948 | 89/89 | 3,670 |

| AFS88002.1 | Ag43 | 1,039 | 72/72 | 1,640 | |

| O111:H− strain 11128 | Not present | ||||

| Commensal strains | |||||

| E. coli K-12 strain W3110 | BAA15825.2 | Ag43 | 1,039 | 69/76 | 1,633 |

| E. coli HS | ABV06428.1 | Ag43c | 583 | 82/87 | 1,868 |

| E. coli SE15 | BAI57745.1 | Ag43c | 616 | 96/97 | 3,131 |

| BAI57742.1 | Ag43c | 325 | 75/83 | 545 | |

| E. coli SE11 | Not present | ||||

| E. coli IAI1 | Not present | ||||

| E. coli ED1A | CAR11130.1 | Ag43 | 1,042 | 75/75 | 1,703 |

Determined by use of EMBOSS (v6.3.1) matcher (http://mobyle.pasteur.fr/cgi-bin/portal.py?#forms::matcher).

Determined by use of the BLASTN algorithm (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?CMD=Web&PAGE_TYPE=BlastHome).

Gene with a deletion.

aa, number of amino acids.

Presence of ompT, Ag43, and cah genes in STEC versus commensal E. coli strains.

To determine the presence of the ompT, Ag43, and cah genes among STEC and commensal E. coli strains, PCR gene detection analysis was conducted using the isolates listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. The ompT gene was present in 98% and 36% of STEC and commensal E. coli strains, respectively, while cah was present in 64% and 9% of STEC and commensal E. coli strains, respectively. ompT (P < 0.0001) and cah (P < 0.001) were more frequently detected in STEC isolates than commensal isolates. The frequency of detection of the Ag43 gene was significantly greater (P < 0.01) in non-O157 human isolates than in commensal isolates (Table 3). These data demonstrate that the ompT and cah genes are highly conserved in STEC strains and mostly absent in commensal E. coli strains.

TABLE 3.

Frequency of detection of Ag43, cah, and ompT genes in 182 E. coli isolates of different origins, determined using PCR

| Origin of isolate | No. of isolates tested | No. (%) of isolates positive |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag43 | cah | ompT | ||

| Commensal E. coli isolatese | 12 | 3 (25) | 1 (8) | 4 (33) |

| O157:H7 STEC isolates from humans | 48 | 1 (2) | 48 (98)d | 48 (100)d |

| O26:H11 STEC isolates from humans | 28 | 28 (100)d | 28 (100)d | 28 (100)d |

| Other non-O157 isolates from humans | 49 | 32 (65)a | 16 (33) | 49 (100)d |

| Total non-O157 isolates | 77 | 60 (78)c | 44 (57)b | 77 (100)d |

| Total STEC isolates from humans | 125 | 61 (49) | 92 (74)d | 125 (100)d |

| STEC isolates from animals | 45 | 26 (58) | 17 (38) | 41 (91)c |

| Total STEC isolates | 170 | 87 (51) | 109 (64)c | 166 (98)d |

P < 0.05 compared with commensal isolates by two-tailed Fisher's exact test.

P < 0.01 compared with commensal isolates by two-tailed Fisher's exact test.

P < 0.001 compared with commensal isolates by two-tailed Fisher's exact test.

P < 0.0001 compared with commensal isolates by two-tailed Fisher's exact test.

Commensal E. coli isolates from human feces, including E. coli HS.

The rOmpT and rCah proteins are reactive for IgG and IgA in HUS patient sera.

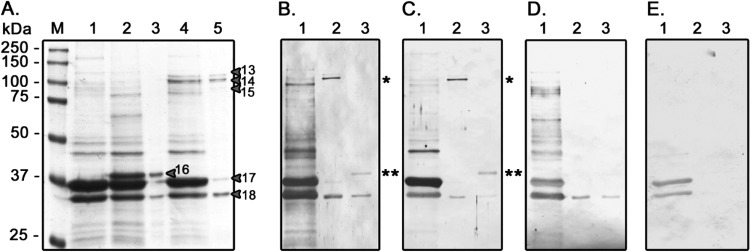

To confirm that the antiserum was recognizing OmpT and Cah, the genes encoding these proteins were cloned into expression vectors and expressed in strain BL21(DE3). As shown in Fig. 4A (lane 5), we observed three different protein bands (arrows labeled 13, 14, and 15) in the OMP profile for the strain expressing cah that were not present in the OMP profile obtained from the BL21(DE3) strain carrying the empty plasmid. These three protein bands were identified by MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry as Cah, and one of them had the expected size (92 kDa) (Table 4). OmpT and Cah were identified to be STEC-associated antigens using the pooled antisera, and it was important to determine the response to these antigens by HUS patients. Therefore, the individual antisera were tested for reactivity with recombinant OmpT and Cah (Fig. 4; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). By using sera from each of the 10 HUS individuals and 3 controls, Western blotting determined that rOmpT (Fig. 4A, arrow 16) was strongly recognized by IgG and IgA of HUS sera and weakly by control sera. Two other proteins copurified with rOmpT and rCah were identified by MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry as PhoE and OmpA (Fig. 4A, arrows 17 and 18, respectively). On the other hand, rCah was recognized by IgG and IgA in 8/10 HUS serum samples. Therefore, Cah was included as an STEC-associated immunogenic protein in this study (Fig. 4B to E; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 4.

OMP profiles of transformed E. coli BL21(DE3) strains and Western blots of the recombinant proteins with HUS and control sera. (A) SDS-PAGE of OMPs on 12% polyacrylamide gels stained with Coomassie blue G-250. Lane 1, E. coli BL21(DE3)/pET15C; lane 2, E. coli BL21(DE3)/pET15C_ompT; lane 3, partially purified rOmpT; lane 4, E. coli BL21(DE3)/pET15C_cah; lane 5, partially purified rCah; lane M, molecular mass ladder, with molecular mass standards indicated on the left. The arrows and numbers correspond to the proteins described in Table 4. (B) Representative Western blot using serum obtained from patient HUS-15 (1:3,500 dilution) and anti-human IgG secondary antibodies (1:5,000 dilution). (C) Representative Western blot using serum obtained from patient HUS-15 (1:1,000 dilution) and anti-human IgA secondary antibodies (1:2,000 dilution). (D) Representative Western blot using serum from control subject C-19 (1:3,500 dilution) and anti-human IgG secondary antibodies (1:5,000 dilution). (E) Representative Western blot using serum from control subject C-19 (1:1,000 dilution) and anti-human IgA secondary antibodies (dilution 1:2,000). Lanes in panels B to E: 1, E. coli BL21(DE3)/pET15C; 2, partially purified rCah (*); 3, partially purified rOmpT (**).

TABLE 4.

Recombinant proteins identified using MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry

| Band no.a | Protein | Best match (GenInfo Identifier sequence identification no.) | E valueb | Scorec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | Cah | gi|15830650 | 6.29e−60 | 647 |

| 14 | Cah | gi|15830650 | 6.29e−83 | 877 |

| 15 | Cah | gi|15830650 | 1.58e−39 | 443 |

| 16 | OmpT | gi|15801391 | 1.26e−73 | 784 |

Numbers correspond to the numbered proteins in Fig. 4A.

Probability of erroneously assigning the protein identity.

Highest score for the protein.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to identify immunogenic OMPs broadly conserved among STEC strains by considering the most common isolates associated with dysenteric diarrhea and HUS, like STEC isolates of serotypes O26:H11, O103, and O157:H7 (35, 36). Furthermore, to broaden the search for antigens, we included the LEE-negative O113:H11 serotype, which has also been associated with HUS (37, 38). Prior studies have reported that exposure to enterobacterial OMPs stimulates a humoral immune response in infected patients (39–41), therefore making them candidates suitable for use in vaccines against Gram-negative pathogens (42–45).

In this study, sera from children with STEC infections had an IgG immune response to FliC, expressed in serotypes O103, O113, and O157, that was strongly recognized by both HUS and control sera, consistent with its characterization as a pathogen-associated molecular pattern (46). FliC was not detected in STEC O26, possibly because FliC was not synthesized under our experimental culture conditions. Other detected proteins, such as OmpC, OmpF, and OmpA, have also been reported to be immunogenic in E. coli, Salmonella, and Shigella (24, 47–49). The pooled HUS antiserum also reacted with l-asparaginase II, an enzyme that catalyzes asparagine hydrolysis (50), and EF-Tu, one of the most abundant and best-characterized cytoplasmic proteins with a role in protein synthesis (51–53). Similar to our findings, l-asparaginase II and EF-Tu have been reported to be immunogenic in other pathogenic bacteria (49, 54–59). In addition, other studies have described the presence of EF-Tu in E. coli OM or OMP extracts (32, 60–64), as well as the interaction of EF-Tu with fibronectin (65), indicating the participation of EF-Tu in adhesion to human intestinal cells and mucin (66–68). It is also possible that EF-Tu belongs to the group of moonlighting proteins (69, 70), which can be found in various locations within the bacterial cell and fulfill specific functions that vary by location.

Other proteins identified in the O113:H11 (LEE-negative) strains but not in the LEE-positive STEC strains studied included Hek and NmpC. It is clear that within LEE-negative STEC isolates there must be unique virulence factors that mediate colonization and infection in the absence of the proteins encoded in the LEE locus. Hek is an important virulence factor in E. coli strains associated with neonatal meningitis-causing E. coli (NMEC). In these cases, it causes autoaggregation and facilitates epithelial cell adherence and invasion (71). NmpC has been reported to be immunogenic in uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) (24) and to increase the rate of E. coli survival by a factor of 50 to 1,000 when the bacteria are exposed to 60°C (72). It is likely that both proteins, Hek and NmpC, may be relevant and conserved antigens in other LEE-negative STEC strains.

Ag43 was another immunogenic protein that participates in autoaggregation and biofilm formation and also may act as an adhesin with certain extracellular matrix proteins (73, 74). Other studies demonstrate that this protein is an autotransporter with an N-proximal passenger domain (α43), which is processed by a yet unidentified protease, and a C-terminal β-barrel domain (the β subunit of Ag43 [β43]) that forms an integral outer membrane protein (75). Our results show that in O26:H11 strains, both domains were identified, but only α43 was recognized by the HUS sera. Two phylogenetic subfamilies have been classified in Ag43 on the basis of the variable region located on the C and N termini of α43 and β43, respectively. Subfamily I includes proteins coded for by the allele present in E. coli K-12 and other variants of UPEC (E. coli CFT073). Subfamily II is characterized by a deletion of 72 amino acids in the C terminus of the α43 passenger domain and includes the allele present in E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 (76). Interestingly, other studies have classified the allele present in O157:H7 to be a homologous gene, called cah (calcium binding antigen 43 homologue), that encodes a protein that has 68.5% amino acid identity and 72% similarity to Ag43 of E. coli K-12. The Cah protein binds calcium ions and also participates in autoaggregation and biofilm formation (77). Analysis of the genome sequences available for STEC and commensal E. coli strains revealed that cah is primarily associated with STEC strains, whereas the Ag43 gene is not. We investigated this further using PCR of a collection of 170 STEC isolates (including 4 STEC strains analyzed using immunoproteomics) and 11 fecal commensal isolates of E. coli (plus the E. coli HS strain). The frequency of detection of cah was significantly greater in human STEC isolates than commensal strains (P < 0.0001), whereas this was not the case for Ag43. However, Cah was not detected in the OMP profiles of O26:H11 and O157:H7 strains, both of which were positive for the cah gene. One possible explanation for this finding is that Cah is observed and detected by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting only when the bacteria are cultivated in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 3 mM EDTA (77). Therefore, in order to evaluate reactivity in HUS and control sera, we cloned the gene and obtained a recombinant Cah protein. After obtaining rCah (92 kDa), we observed two additional bands with molecular masses of 78 kDa and 97 kDa, also identified as Cah.

One possible explanation for this finding is that the protease responsible for protein processing is not expressed in this bacterium. rCah was reactive for IgG and IgA in the majority of HUS sera (Fig. 4B; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Therefore, Cah was included in the group of STEC-associated immunogenic proteins and is one of the most promising antigens for future studies. Interestingly, rCah was not seroreactive in 2/10 HUS serum samples tested, indicating that the STEC strains responsible for these HUS cases are probably not able to express Cah or they do not carry the cah gene, a finding that is consistent with our analysis of the frequency of detection of cah in STEC strains (Table 3).

OmpT is another immunogenic protein present in all STEC OMP profiles. OmpT is a serine protease well characterized to be an important virulence factor in NMEC and UPEC strains (78–82). In STEC, OmpT degrades LL-37 (83), an antimicrobial peptide secreted by epithelial cells of the stomach and colon (84, 85). Therefore, OmpT could play a defensive role against the host's immune response. Moreover, a role for OmpT in outer membrane vesicle (OMV) biogenesis in STEC has been described recently (86). The ompT gene is abundant and widely distributed in E. coli. However, epidemiological studies seem to indicate that it is mainly associated with pathogenic strains. ompT detection frequencies of 96% have been described in NMEC (n = 70) (79), and ompT detection frequencies of over 80% have been described in UPEC (80, 82). For commensal fecal isolates, the ompT detection frequency is unclear, as reports have described frequencies ranging from 67.7% (n = 318) (82) to 19% (n = 135) (80). These divergent results may be attributable to the fact that the fecal isolates used as intestinal commensal controls may have contained NMEC or UPEC (opportunistic pathogens), making it difficult to confirm that the strains were truly commensal intestinal types. To our knowledge, there have been no previous reports on the frequency of ompT detection in STEC. The presence of ompT in our STEC collection and fecal commensal isolates confirms that the ompT detection frequency is significantly greater (P < 0.0001) in STEC strains than human intestinal commensal strains (Table 3).

Moreover, Western blot assays showed that rOmpT was strongly recognized by IgG and IgA antibodies present in HUS sera and was weakly recognized in one control serum sample (Table 1; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). One possible explanation for OmpT reactivity in control sera could be cross-reactivity. OmpT has been described in other pathogenic E. coli strains, and previous exposure to such strains could result in an immunogenic cross-reaction. Despite the heterogeneity in the humoral immune response observed for each HUS serum sample through Western blot assays (see lane 1 in each panel of Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), both rOmpT and rCah were immunoreactive. These results indicate that the OmpT and Cah proteins are synthesized in vivo during STEC infection in humans that generate a strong humoral immune response.

Although the immunoproteomic focus used in this study allowed us to identify STEC antigen proteins, we cannot rule out the possibility of the presence of other immunogenic proteins, due to limitations inherent in the experimental design. First, OMP profiles were obtained by growing strains in a single culture medium. Second, low-abundance proteins that can be immunogenic are usually hidden by high-abundance proteins in complex samples analyzed by 2D-PAGE. Furthermore, because the proteins were subjected to denaturing conditions before Western blot analysis, it is likely that some conformational epitopes were not recognized by the sera.

Overall, our principal finding in this study was the identification of Ag43, Cah, OmpT, Hek, NmpC, EF-Tu, and l-asparaginase II proteins as immunogenic proteins produced during STEC infection. These had not previously been characterized to be immunogenic in STEC, even after extensive studies aimed at identifying antigens expressed in vivo during infection in humans (87). Several lines of evidence suggest that two of these antigens, Cah and OmpT, deserve further study to determine their potential role as protective antigens for STEC-related infections. Because STEC colonizes the mucosa, a humoral IgA response is required in order to reduce the chances of intestinal colonization by this pathogen, and both Cah and OmpT react with IgA from HUS sera. The cah and ompT genes are conserved in STEC strains but not in fecal commensal E. coli strains, suggesting that Cah and OmpT could have a role in protection against a wide range of STEC serogroups with minimal cross-reactivity with commensal microbiota. Overall, our findings are important in the understanding of the antigens produced by STEC during human infection and the immune response against these pathogens in HUS.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Miguel O'Ryan, Oscar Gómez, and Anne J. Lagomarcino for their critical reading of the manuscript.

This study was supported by FONDECYT grant 1110260, awarded to R. Vidal.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 25 August 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.02030-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nataro JP, Kaper JB. 1998. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:142–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rivas M, Miliwebsky E, Chinen I, Deza N, Leotta GA. 2006. The epidemiology of hemolytic uremic syndrome in Argentina. Diagnosis of the etiologic agent, reservoirs and routes of transmission. Medicina (Buenos Aires) 66:27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gyles CL. 2007. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: an overview. J. Anim. Sci. 85:E45–E62. 10.2527/jas.2006-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scientific Working Group Meeting, WHO. 1998. Zoonotic non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC). Scientific Working Group Meeting, WHO, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ethelberg S, Olsen KEP, Scheutz F, Jensen C, Schiellerup P, Enberg J, Petersen AM, Olesen B, Gerner-Smidt P, Mølbak K. 2004. Virulence factors for hemolytic uremic syndrome, Denmark. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:842–847. 10.3201/eid1005.030576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prado JV, Cavagnaro SM, Study Group for STEC Infection 2008. Hemolytic uremic syndrome associated to shigatoxin producing Escherichia coli in Chilean children: clinical and epidemiological aspects. Rev. Chilena Infectol. 25:435–444 (In Spanish.). 10.4067/S0716-10182008000600003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Gasser C, Gautier E, Steck A, Siebenmann RE, Oeschlin R. 1955. Hamolytisch-uramische Syndrome: bilaterale Nierenrindennekrosen bei akuten Erworbenen hamolytischen Anamien. Schweiz Med. Wochenschr. 85:905–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karch H, Goroncy-Bermes P, Opferkuch W, Kroll H, O'Brien A. 1985. Subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics modulate amount of Shiga-like toxin produced by Escherichia coli, p 239–245 In Adam D, Hahr H, Opterkuch W. (ed), The influence of antibiotics on the host parasite relationship. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong CS, Jelacic S, Habeeb RL, Watkins SL, Tarr PI. 2000. The risk of the hemolytic-uremic syndrome after antibiotic treatment of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 342:1930–1936. 10.1056/NEJM200006293422601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukherjee J, Chios K, Fishwild D, Hudson D, O'Donnell S, Rich SM, Donohue-Rolfe A, Tzipori S. 2002. Human Stx2-specific monoclonal antibodies prevent systemic complications of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection. Infect. Immun. 70:612–619. 10.1128/IAI.70.2.612-619.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mukherjee J, Chios K, Fishwild D, Hudson D, O'Donnell S, Rich SM, Donohue-Rolfe A, Tzipori S. 2002. Production and characterization of protective human antibodies against Shiga toxin 1. Infect. Immun. 70:5896–5899. 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5896-5899.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trachtman H, Cnaan A, Christen E, Gibbs K, Zhao S, Acheson DWK, Weiss R, Kaskel FJ, Spitzer A, Hirschman GH. 2003. Effect of an oral Shiga toxin-binding agent on diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome in children: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290:1337–1344. 10.1001/jama.290.10.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohawk KL, O'Brien AD. 2011. Mouse models of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection and Shiga toxin injection. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011:2581–2585. 10.1155/2011/258185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu J, Liu Y, Yu S, Wang H, Wang Q, Yi Y, Zhu F, Yu X-J, Zou Q, Mao X. 2009. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli trivalent recombinant vaccine containing EspA, intimin and Stx2 induces strong humoral immune response and confers protection in mice. Microbes Infect. 11:835–841. 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai K, Gao X, Li T, Wang Q, Hou X, Tu W, Xiao L, Tian M, Liu Y, Wang H. 2011. Enhanced immunogenicity of a novel Stx2Am-Stx1B fusion protein in a mice model of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection. Vaccine 29:946–952. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai K, Gao X, Li T, Hou X, Wang Q, Liu H, Xiao L, Tu W, Liu Y, Shi J, Wang H. 2010. Intragastric immunization of mice with enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 bacterial ghosts reduces mortality and shedding and induces a Th2-type dominated mixed immune response. Can. J. Microbiol. 56:389–398. 10.1139/W10-025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmed A, Li J, Shiloach Y, Robbins JB, Szu SC. 2006. Safety and immunogenicity of Escherichia coli O157 O-specific polysaccharide conjugate vaccine in 2–5-year-old children. J. Infect. Dis. 193:515–521. 10.1086/499821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greatorex J, Thorne G. 1994. Humoral immune responses to Shiga-like toxins and Escherichia coli O157 lipopolysaccharide in hemolytic-uremic syndrome patients and healthy subjects. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1172–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherman P, Soni R, Yeger H. 1988. Characterization of flagella purified from enterohemorrhagic, Vero-cytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:1367–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asper DJ, Karmali MA, Townsend H, Rogan D, Potter AA. 2011. Serological response of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli type III secreted proteins in sera from vaccinated rabbits, naturally infected cattle, and humans. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 18:1052–1057. 10.1128/CVI.00068-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenkins C, Chart H, Smith HR, Hartland EL, Batchelor M, Delahay RM, Dougan G, Frankel G. 2000. Antibody response of patients infected with verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli to protein antigens encoded on the LEE locus. J. Med. Microbiol. 49:97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Frey E, Mackenzie AM, Finlay BB. 2000. Human response to Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection: antibodies to secreted virulence factors. Infect. Immun. 68:5090–5095. 10.1128/IAI.68.9.5090-5095.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chenoweth MR, Greene CE, Krause DC, Gherardini FC. 2004. Predominant outer membrane antigens of Bartonella henselae. Infect. Immun. 72:3097–3105. 10.1128/IAI.72.6.3097-3105.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hagan EC, Mobley HLT. 2007. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli outer membrane antigens expressed during urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 75:3941–3949. 10.1128/IAI.00337-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurupati P, Teh BK, Kumarasinghe G, Poh CL. 2006. Identification of vaccine candidate antigens of an ESBL producing Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical strain by immunoproteome analysis. Proteomics 6:836–844. 10.1002/pmic.200500214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prokhorova TA, Nielsen PN, Petersen J, Kofoed T, Crawford JS, Morsczeck C, Boysen A, Schrotz-King P. 2006. Novel surface polypeptides of Campylobacter jejuni as traveller's diarrhoea vaccine candidates discovered by proteomics. Vaccine 24:6446–6455. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rivas L, Fegan N, Dykes GA. 2008. Expression and putative roles in attachment of outer membrane proteins of Escherichia coli O157 from planktonic and sessile culture. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 5:155–164. 10.1089/fpd.2007.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laemmli UK. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680–685. 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu NY, Wagner JR, Laird MR, Melli G, Rey S, Lo R, Dao P, Sahinalp SC, Ester M, Foster LJ, Brinkman FSL. 2010. PSORTb 3.0: improved protein subcellular localization prediction with refined localization subcategories and predictive capabilities for all prokaryotes. Bioinformatics 26:1608–1615. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caballero VC, Toledo VP, Maturana C, Fisher CR, Payne SM, Salazar JC. 2012. Expression of Shigella flexneri gluQ-rs gene is linked to dksA and controlled by a transcriptional terminator. BMC Microbiol. 12:226. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai E-M, Nair U, Phadke ND, Maddock JR. 2004. Proteomic screening and identification of differentially distributed membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 52:1029–1044. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taddei CR, Oliveira FF, Piazza RMF, Paes Leme AF, Klitzke CF, Serrano SMT, Martinez MB, Elias WP, Sant Anna OA. 2011. A comparative study of the outer membrane proteome from an atypical and a typical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Open Microbiol. J. 5:83–90. 10.2174/1874285801105010083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molloy MP, Herbert BR, Slade MB, Rabilloud T, Nouwens AS, Williams KL, Gooley AA. 2000. Proteomic analysis of the Escherichia coli outer membrane. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:2871–2881. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alteri CJ, Mobley HLT. 2007. Quantitative profile of the uropathogenic Escherichia coli outer membrane proteome during growth in human urine. Infect. Immun. 75:2679–2688. 10.1128/IAI.00076-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brooks JT, Sowers EG, Wells JG, Greene KD, Griffin PM, Hoekstra RM, Strockbine NA. 2005. Non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections in the United States, 1983-2002. J. Infect. Dis. 192:1422–1429. 10.1086/466536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Werber D, Beutin L, Pichner R, Stark K, Fruth A. 2008. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli serogroups in food and patients, Germany. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:1803–1806. 10.3201/eid1411.080361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paton A, Paton J. 1999. Direct detection of Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli strains belonging to serogroups O111, O157, and O113 by multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3362–3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paton AW, Woodrow MC, Doyle RM, Lanser JA, Paton JC. 1999. Molecular characterization of a Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli O113:H21 strain lacking eae responsible for a cluster of cases of hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3357–3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braun V, Bosch V, Klumpp ER, Neff I, Mayer H, Schlecht S. 1976. Antigenic determinants of murein lipoprotein and its exposure at the surface of Enterobacteriaceae. Eur. J. Biochem. 62:555–566. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henriksen AZ, Maeland JA. 1987. Serum antibodies to outer membrane proteins of Escherichia coli in healthy persons and patients with bacteremia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25:2181–2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hofstra H, Dankert J. 1980. Major outer membrane proteins: common antigens in Enterobacteriaceae species. J. Gen. Microbiol. 119:123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grandi G. 2001. Antibacterial vaccine design using genomics and proteomics. Trends Biotechnol. 19:181–188. 10.1016/S0167-7799(01)01600-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawahara M, Human L, Winningham J, Domingue G. 1994. Antibodies to Escherichia coli O6 porins cross-react with urinary pathogens. Immunobiology 192:65–76. 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80408-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McMillan D, Chhatwal G. 2005. Prospects for a group A streptococcal vaccine. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 7:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pages C, Prince P, Pages J. 1987. Immunological comparison of major outer membrane proteins from different strains of Escherichia coli. Ann. Inst. Pasteur Microbiol. 138:393–406. 10.1016/0769-2609(87)90057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramos HC, Rumbo M, Sirard J-C. 2004. Bacterial flagellins: mediators of pathogenicity and host immune responses in mucosa. Trends Microbiol. 12:509–517. 10.1016/j.tim.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Secundino I, López-Macías C, Cervantes-Barragán L, Gil-Cruz C, Ríos-Sarabia N, Pastelin-Palacios R, Villasis-Keever MA, Becker I, Puente JL, Calva E, Isibasi A. 2006. Salmonella porins induce a sustained, lifelong specific bactericidal antibody memory response. Immunology 117:59–70. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh SP, Singh SR, Williams YU, Jones L, Abdullah T. 1995. Antigenic determinants of the OmpC porin from Salmonella typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 63:4600–4605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ying T, Wang H, Li M, Wang J, Wang J, Shi Z, Feng E, Liu X, Su G, Wei K, Zhang X, Huang P, Huang L. 2005. Immunoproteomics of outer membrane proteins and extracellular proteins of Shigella flexneri 2a 2457T. Proteomics 5:4777–4793. 10.1002/pmic.200401326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ehrman M, Cedar H, Schwartz JH. 1971. l-Asparaginase II of Escherichia coli. Studies on the enzymatic mechanism of action. J. Biol. Chem. 246:88–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bosch L, Kraal B, Van der Meide PH, Duisterwinkel FJ, Van Noort JM. 1983. The elongation factor EF-Tu and its two encoding genes. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 30:91–126. 10.1016/S0079-6603(08)60684-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaziro Y. 1978. The role of guanosine 5′-triphosphate in polypeptide chain elongation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 505:95–127. 10.1016/0304-4173(78)90009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller D, Weissbach H. 1977. Aminoacyl-tRNA transfer factors, p 323–373 In Weissbach H, Pestka S. (ed), Molecular mechanisms of protein biosynthesis. Academic Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gupta MK, Subramanian V, Yadav JS. 2009. Immunoproteomic identification of secretory and subcellular protein antigens and functional evaluation of the secretome fraction of Mycobacterium immunogenum, a newly recognized species of the Mycobacterium chelonae-Mycobacterium abscessus group. J. Proteome Res. 8:2319–2330. 10.1021/pr8009462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scotti C, Sommi P, Pasquetto MV, Cappelletti D, Stivala S, Mignosi P, Savio M, Chiarelli LR, Valentini G, Bolanos-Garcia VM, Merrell DS, Franchini S, Verona ML, Bolis C, Solcia E, Manca R, Franciotta D, Casasco A, Filipazzi P, Zardini E, Vannini V. 2010. Cell-cycle inhibition by Helicobacter pylori l-asparaginase. PLoS One 5:e13892. 10.1371/journal.pone.0013892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kullas AL, McClelland M, Yang H-J, Tam JW, Torres A, Porwollik S, Mena P, McPhee JB, Bogomolnaya L, Andrews-Polymenis H, van der Velden AWM. 2012. l-Asparaginase II produced by Salmonella typhimurium inhibits T cell responses and mediates virulence. Cell Host Microbe 12:791–798. 10.1016/j.chom.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lopez JE, Siems WF, Palmer GH, Brayton KA, McGuire TC, Norimine J, Brown WC. 2005. Identification of novel antigenic proteins in a complex Anaplasma marginale outer membrane immunogen by mass spectrometry and genomic mapping. Infect. Immun. 73:8109–8118. 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8109-8118.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brady RA, Leid JG, Camper AK, Costerton JW, Shirtliff ME. 2006. Identification of Staphylococcus aureus proteins recognized by the antibody-mediated immune response to a biofilm infection. Infect. Immun. 74:3415–3426. 10.1128/IAI.00392-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nieves W, Heang J, Asakrah S, Höner zu Bentrup K, Roy CJ, Morici LA. 2010. Immunospecific responses to bacterial elongation factor Tu during Burkholderia infection and immunization. PLoS One 5:e14361. 10.1371/journal.pone.0014361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dombou M, Bhide SV, Mizushima S. 1981. Appearance of elongation factor Tu in the outer membrane of sucrose-dependent spectinomycin-resistant mutants of Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 113:397–403. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb05079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Otto K, Norbeck J, Larsson T, Karlsson KA, Hermansson M. 2001. Adhesion of type 1-fimbriated Escherichia coli to abiotic surfaces leads to altered composition of outer membrane proteins. J. Bacteriol. 183:2445–2453. 10.1128/JB.183.8.2445-2453.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sedgwick EG, Bragg PD. 1986. Uncoupler-induced relocation of elongation factor Tu to the outer membrane in an uncoupler-resistant mutant of Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 856:50–58. 10.1016/0005-2736(86)90009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sommer U, Petersen J, Pfeiffer M, Schrotz-King P, Morsczeck C. 2010. Comparison of surface proteomes of enterotoxigenic (ETEC) and commensal Escherichia coli strains. J. Microbiol. Methods 83:13–19. 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang D-F, Li H, Lin X-M, Wang S-Y, Peng X-X. 2011. Characterization of outer membrane proteins of Escherichia coli in response to phenol stress. Curr. Microbiol. 62:777–783. 10.1007/s00284-010-9786-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dallo SF, Kannan TR, Blaylock MW, Baseman JB. 2002. Elongation factor Tu and E1 β subunit of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex act as fibronectin binding proteins in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1041–1051. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Granato D, Bergonzelli GE, Pridmore RD, Marvin L, Rouvet M, Corthésy-Theulaz IE. 2004. Cell surface-associated elongation factor Tu mediates the attachment of Lactobacillus johnsonii NCC533 (La1) to human intestinal cells and mucins. Infect. Immun. 72:2160–2169. 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2160-2169.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dhanani AS, Bagchi T. 2013. The expression of adhesin EF-Tu in response to mucin and its role in Lactobacillus adhesion and competitive inhibition of enteropathogens to mucin. J. Appl. Microbiol. 115:546–554. 10.1111/jam.12249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nishiyama K, Ochiai A, Tsubokawa D, Ishihara K, Yamamoto Y, Mukai T. 2013. Identification and characterization of sulfated carbohydrate-binding protein from Lactobacillus reuteri. PLoS One 8:e83703. 10.1371/journal.pone.0083703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Henderson B, Martin A. 2011. Bacterial virulence in the moonlight: multitasking bacterial moonlighting proteins are virulence determinants in infectious disease. Infect. Immun. 79:3476–3491. 10.1128/IAI.00179-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jeffery C. 1999. Moonlighting proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:8–11. 10.1016/S0968-0004(98)01335-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fagan RP, Lambert MA, Smith SGJ. 2008. The Hek outer membrane protein of Escherichia coli strain RS218 binds to proteoglycan and utilizes a single extracellular loop for adherence, invasion, and autoaggregation. Infect. Immun. 76:1135–1142. 10.1128/IAI.01327-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ruan L, Pleitner A, Gänzle MG, McMullen LM. 2011. Solute transport proteins and the outer membrane protein NmpC contribute to heat resistance of Escherichia coli AW1.7. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:2961–2967. 10.1128/AEM.01930-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Diderichsen B. 1980. flu, a metastable gene controlling surface properties of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 141:858–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Reidl S, Lehmann A, Schiller R, Salam Khan A, Dobrindt U. 2009. Impact of O-glycosylation on the molecular and cellular adhesion properties of the Escherichia coli autotransporter protein Ag43. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 299:389–401. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Caffrey P, Owen P. 1989. Purification and N-terminal sequence of the alpha subunit of antigen 43, a unique protein complex associated with the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 171:3634–3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.van der Woude MW, Henderson IR. 2008. Regulation and function of Ag43 (flu). Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 62:153–169. 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Torres AG, Perna NT, Burland V, Ruknudin A, Blattner FR, Kaper JB. 2002. Characterization of Cah, a calcium-binding and heat-extractable autotransporter protein of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 45:951–966. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Foxman B, Zhang L, Palin K, Tallman P, Marrs CF. 1995. Bacterial virulence characteristics of Escherichia coli isolates from first-time urinary tract infection. J. Infect. Dis. 171:1514–1521. 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Johnson JR, Oswald E, O'Bryan TT, Kuskowski MA, Spanjaard L. 2002. Phylogenetic distribution of virulence-associated genes among Escherichia coli isolates associated with neonatal bacterial meningitis in the Netherlands. J. Infect. Dis. 185:774–784. 10.1086/339343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kudinha T, Johnson JR, Andrew SD, Kong F, Anderson P, Gilbert GL. 2013. Distribution of phylogenetic groups, sequence type ST131, and virulence-associated traits among Escherichia coli isolates from men with pyelonephritis or cystitis and healthy controls. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 19:E173–E180. 10.1111/1469-0691.12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lundrigan MD, Webb RM. 1992. Prevalence of ompT among Escherichia coli isolates of human origin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 76:51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Marrs CF, Zhang L, Tallman P, Manning SD, Somsel P, Raz P, Colodner R, Jantunen ME, Siitonen A, Saxen H, Foxman B. 2002. Variations in 10 putative uropathogen virulence genes among urinary, faecal and peri-urethral Escherichia coli. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:138–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thomassin J-L, Brannon JR, Gibbs BF, Gruenheid S, Le Moual H. 2012. OmpT outer membrane proteases of enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli contribute differently to the degradation of human LL-37. Infect. Immun. 80:483–492. 10.1128/IAI.05674-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hase K, Eckmann L, Leopard JD, Varki N, Kagnoff MF. 2002. Cell differentiation is a key determinant of cathelicidin LL-37/human cationic antimicrobial protein 18 expression by human colon epithelium. Infect. Immun. 70:953–963. 10.1128/IAI.70.2.953-963.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hase K, Murakami M, Iimura M, Cole SP, Horibe Y, Ohtake T, Obonyo M, Gallo RL, Eckmann L, Kagnoff MF. 2003. Expression of LL-37 by human gastric epithelial cells as a potential host defense mechanism against Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology 125:1613–1625. 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Premjani V, Tilley D, Gruenheid S, Le Moual H, Samis JA. 2014. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli OmpT regulates outer membrane vesicle biogenesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 355:185–192. 10.1111/1574-6968.12463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.John M, Kudva IT, Griffin RW, Dodson AW, McManus B, Krastins B, Sarracino D, Progulske-Fox A, Hillman JD, Handfield M, Tarr PI, Calderwood SB. 2005. Use of in vivo-induced antigen technology for identification of Escherichia coli O157:H7 proteins expressed during human infection. Infect. Immun. 73:2665–2679. 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2665-2679.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Levine M. 1987. Escherichia coli that cause diarrhea: enterotoxigenic, enteropathogenic, enteroinvasive, enterohemorrhagic, enteroadherent. J. Infect. Dis. 155:377–389. 10.1093/infdis/155.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Woodcock DM, Crowther PJ, Doherty J, Jefferson S, DeCruz E, Noyer-Weidner M, Smith SS, Michael MZ, Graham MW. 1989. Quantitative evaluation of Escherichia coli host strains for tolerance to cytosine methylation in plasmid and phage recombinants. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:3469–3478. 10.1093/nar/17.9.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Studier F, Moffatt B. 1986. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high level expression of cloned genes. J. Mol. Biol. 189:113–130. 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.