Abstract

MmpL3, a resistance-nodulation-division (RND) superfamily transporter, has been implicated in the formation of the outer membrane of Mycobacterium tuberculosis; specifically, MmpL3 is required for the export of mycolic acids in the form of trehalose monomycolates (TMM) to the periplasmic space or outer membrane of M. tuberculosis. Recently, seven series of inhibitors identified by whole-cell screening against M. tuberculosis, including the antituberculosis drug candidate SQ109, were shown to abolish MmpL3-mediated TMM export. However, this mode of action was brought into question by the broad-spectrum activities of some of these inhibitors against a variety of bacterial and fungal pathogens that do not synthesize mycolic acids. This observation, coupled with the ability of three of these classes of inhibitors to kill nonreplicating M. tuberculosis bacilli, led us to investigate alternative mechanisms of action. Our results indicate that the inhibitory effects of adamantyl ureas, indolecarboxamides, tetrahydropyrazolopyrimidines, and the 1,5-diarylpyrrole BM212 on the transport activity of MmpL3 in actively replicating M. tuberculosis bacilli are, like that of SQ109, most likely due to their ability to dissipate the transmembrane electrochemical proton gradient. In addition to providing novel insights into the modes of action of compounds reported to inhibit MmpL3, our results provide the first explanation for the large number of pharmacophores that apparently target this essential inner membrane transporter.

INTRODUCTION

The need for novel, more efficient, and safer drugs capable of addressing the growing issue of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) (1) has prompted intense research efforts from academia, nonprofit organizations, and the pharmaceutical industry, resulting in an increasing flow of novel anti-Mycobacterium tuberculosis agents entering the drug development pipeline (http://www.newtbdrugs.org) (2, 3). One approach taken has been to revisit well-established drugs, such as ethambutol (EMB), rifampin (RIF), or isoniazid (INH), with the objective of identifying analogs showing more favorable physicochemical properties, greater potency, and decreased toxicity. Using combinatorial chemistry to synthesize and screen a chemical library designed around the active 1,2-ethylenediamine pharmacophore of EMB (4), SQ109 (Fig. 1) was identified as a promising lead compound based on its mycobactericidal activity, cytotoxicity, pharmacokinetic properties, and improved efficacy against M. tuberculosis in vivo (5). Remarkably, SQ109 concentrates in lung tissues and displays synergistic activity, both in vitro and in vivo, with most of the drugs currently used to treat TB (5–7). An evaluation of SQ109 as a substitute for EMB in the standard four-drug treatment regimen suggests that it may have the potential to shorten treatment duration (7). SQ109 was found to be safe and well tolerated in phase I and early phase II clinical trials, and it has now entered trials to evaluate its efficacy in patients with pulmonary TB (7). Although designed to be an analog of EMB and, therefore, an inhibitor of arabinogalactan synthesis, SQ109 does not cause the typical depletion in cell wall arabinose or the transcriptional profile normally observed upon EMB treatment (8). Instead, an analysis of mutants resistant to related ethylenediamine compounds coupled to the metabolic labeling of M. tuberculosis-treated cells led to the conclusion that the trehalose monomycolate (TMM) transporter MmpL3 was the primary target of this series of compounds (9).

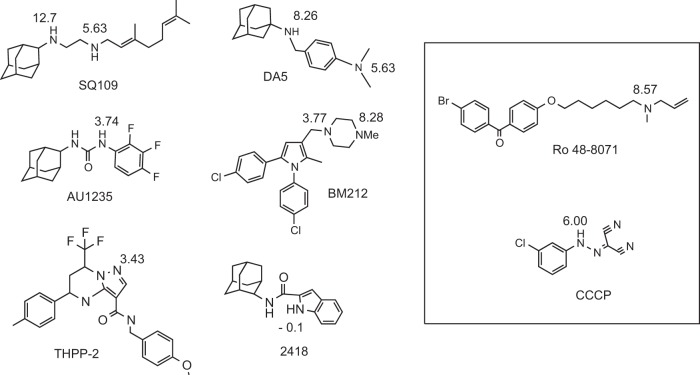

FIG 1.

Structures of compounds discussed in the text. Shown are the MmpL3 inhibitors SQ109 (an ethylenediamine analog of ethambutol), BM212 (a 1,5-diarylpyrrole), THPP-2 (a tetrahydropyrazolo pyrimidine), 2418 (an indolecarboxamide), AU1235 (an adamantyl urea), and DA5 (a SQ109-related compound). The known menaquinone inhibitor (Ro 48-8071) and PMF uncoupler (CCCP) are boxed. The estimated pKa values are indicated. The pKa values were predicted using the pKa component of Pipeline Pilot (Accelrys, Inc.). The actual pKa for CCCP is 6.09 (48).

Surprisingly, in the last 2 years, the whole-cell-based screening of compound libraries against M. tuberculosis in culture coupled to the whole-genome sequencing of spontaneous resistant mutants identified a variety of pharmacophores that apparently shared the same mode of action as SQ109. These inhibitors include the 1,5-diarylpyrrole derivative BM212 and analogs (10, 11), the benzimidazole C215 (12), tetrahydropyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine-3-carboxamides (THPPs) (13, 14), N-benzyl-6′,7′-dihydrospiro[piperidine-4,4′-thieno[3,2-c]pyrans (13), indolecarboxamides (15–18), and adamantyl ureas (AUs) (19) (Fig. 1). While the apparent promiscuity of MmpL3 as a drug target may owe to unusual vulnerability or druggability, the diversity of the chemical scaffolds identified and important differences in their spectra of activity led us to question their direct mechanism of action on the transporter. In particular, the fact that SQ109, BM212, and THPP compounds display inhibitory activity against a broad spectrum of bacterial and fungal pathogens that are devoid of mycolic acids (7, 20, 21), while AUs and indolecarboxamides specifically target mycobacteria (17, 19), suggests that the three first compounds had at least one broader-spectrum target in M. tuberculosis or killed the bacterium through a different mechanism, impacting MmpL3 only indirectly. Another important difference between the MmpL3 inhibitors resides in their activities against nonreplicating M. tuberculosis bacilli. While SQ109, BM212, and THPPs kill this population of cells (11, 22, and this study), AUs and indolecarboxamides do not (17, 19, and this study).

Recent studies have established that SQ109 inhibits the enzymes involved in menaquinone synthesis, respiration, and, hence, ATP synthesis (22); in addition, the compound acts as an uncoupler, collapsing the proton motive force (PMF). These diverse activities, which are found in mycobacteria and species, such as Escherichia coli, that do not have MmpL3 orthologs, might account for the inhibitory effects of SQ109 against a variety of pathogens. Importantly, the disruptive effect of SQ109 on the PMF may also impact MmpL proteins, since these resistance-nodulation-division (RND) transporters are thought to catalyze substrate export via a proton antiport mechanism (23–25). Understanding the mode of action of small-molecule inhibitors is critical to driving their optimization process; therefore, we revisited the mycobactericidal activities of SQ109 and other MmpL3 inhibitors. Our results clearly indicate that BM212, THPPs, indolecarboxamides, and AUs dissipate, as does SQ109, the transmembrane proton concentration gradient (ΔpH), membrane potential (Δψ), or both components of the PMF simultaneously. Evidence is further provided that the ability of these compounds to collapse the PMF most likely accounts for their inhibitory effect on MmpL3 and other MmpL-driven processes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

E. coli strain DH5α, the strain used for cloning, was grown in LB, Lennox medium (BD, Difco) at 37°C. M. tuberculosis strains H37Rv ATCC 25618 and TMC102 were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth supplemented with oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase (OADC) (BD, Difco) and 0.05% tyloxapol or on solid Middlebrook 7H11 medium supplemented with OADC at 37°C. Mycobacterium smegmatis strain mc2155 was grown in LB broth at 37°C. The avirulent auxotrophic M. tuberculosis H37Rv strain mc26206 (ΔpanCD ΔleuCD) was grown at 37°C in Middlebrook 7H9-OADC–0.05% tyloxapol supplemented with 0.2% Casamino Acids, 48 μg/ml pantothenate, and 50 μg/ml l-leucine or on similarly supplemented Middlebrook 7H11-OADC agar medium. Hypoxic nonreplicating M. tuberculosis H37Rv mc26206 organisms were generated under conditions of slow stirring in Dubos Tween 80-albumin broth in sealed tubes, as described previously (26). The control tubes contained methylene blue dye (1.5 μg/ml) as an indicator of oxygen depletion.

Drug and ionophore susceptibility determinations.

The MICs of SQ109, AUs (19), BM212 (10, 11), 2418, the tetrahydropyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine-3-carboxamide compound 2 (THPP-2) (14), Ro 48-8071 (27), nigericin, valinomycin, and carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) against M. tuberculosis H37Rv mc26206 and M. smegmatis mc2155 were determined in 7H9-OADC–0.05% tyloxapol medium (supplemented with 0.2% Casamino Acids, 48 μg/ml pantothenate, and 50 μg/ml l-leucine in the case of M. tuberculosis H37Rv mc26206) in 96-well microtiter plates using the colorimetric resazurin microtiter assay and visually scanning for growth. Alternatively, the MICs of RIF, SQ109, and AU1235 against actively replicating and nonreplicating M. tuberculosis H37Rv were determined using the microplate alamarBlue assay (MABA) and low-oxygen-recovery assay (LORA), as described previously (28, 29).

Nutrient starvation model.

The nutrient starvation conditions were essentially according to those described earlier by Betts et al. (30). Briefly, M. tuberculosis H37Rv ATCC 25618 was grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth supplemented with ADC (BD, Difco) and 0.025% Tween 80 in roller bottles at 37°C, with constant rolling at 2 rpm. After a week, the log-phase cultures were pelleted, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and transferred to standing tissue culture flasks containing PBS for further incubation at 37°C for up to 6 weeks. One-milliliter aliquots of a 1:50 dilution of the 7-day-old log-phase culture, and 1-ml aliquots of 2-week-old and 6-week-old starved M. tuberculosis cultures were transferred to triplicate wells of 48-well plates containing isoniazid (INH), rifampin (RIF), SQ109, DA5 (ChemBridge, CA, USA), 2418, THPP-2, or BM212 at 5× and 50× their MICs. The control wells received no drug. The cultures were incubated with or without drugs at 37°C for 7 days in a 5% CO2 incubator before being harvested and resuspended in 7H9 medium, and serial dilutions were plated on 7H11-OADC agar to enumerate the viable CFU. This experiment was performed twice on two independent culture batches, and the results of one representative experiment are shown in Fig. 2.

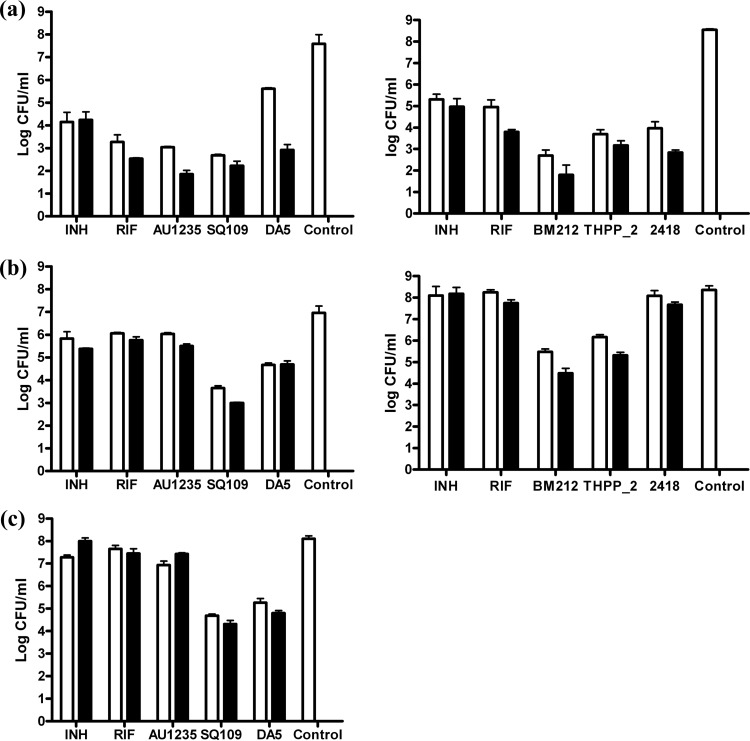

FIG 2.

Drug susceptibilities of actively replicating versus nutrient-starved M. tuberculosis cultures. The effects of SQ109, DA5, INH, RIF, THPP-2, BM212, 2418, and AU1235 on the viability of log-phase and 2- and 6-week nutrient-starved M. tuberculosis H37Rv ATCC 25618 cultures were investigated. Triplicate wells of M. tuberculosis cultures incubated for 7 days in the absence or presence of 5× the MIC (white bars) or 50× the MIC (black bars) of each of the drugs were processed, and mean values and standard deviations of the viable CFU counts are shown. (a) log-phase cultures; (b) 2-week-starved cultures; (c) 6-week-starved cultures. The drug concentrations (5× and 50× the MIC, respectively) were as follows: INH, 0.5 and 5 μg/ml; RIF, 0.5 and 5 μg/ml; DA5, 16 and 160 μg/ml; AU1235, 0.5 and 5 μg/ml; SQ109, 2.5 and 25 μg/ml; THPP-2, 7 and 70 μg/ml; BM212, 7.8 and 78 μg/ml; and 2418, 7.8 and 78 μg/ml.

Drug and ionophore treatment of whole M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis cells, metabolic labeling, and lipid analysis.

Menaquinone biosynthesis in SQ109-treated, Ro 48-8071-treated, and untreated M. tuberculosis H37Rv mc26206 cells was monitored by metabolic labeling with l-[methyl-14C]methionine (56.3 Ci/mol; PerkinElmer, Inc.), essentially as described previously (27). Briefly, M. tuberculosis cells grown to mid-log phase (A600, 0.6 to 0.7) in 7H9-OADC–0.05% tyloxapol were pelleted and resuspended in fresh medium at 1/10 of the original volume, and 0.5-ml subsets were incubated with 10, 25, and 50 μg/ml Ro 48-8071 (an inhibitor of menaquinone biosynthesis; the concentrations were equivalent to 0.4×, 1×, and 2× the MIC, respectively), 0.8 and 1.6 μg/ml SQ109 (1× and 2× the MIC, respectively), or no drug for 20 min prior to the addition of 5 μCi l-[methyl-14C]methionine and further incubation at 37°C for 2 h. The labeling reactions were terminated by adding chloroform-methanol (2:1 [vol/vol]). The apolar lipids containing the menaquinones were separated from the polar lipids by silicic acid column chromatography, using chloroform as the eluent, and the samples were run on aluminum-backed silica gel 60-F254 precoated plates (E. Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), which were developed in hexane/diethyl ether (95:5 [vol/vol]).

To compare the effects of CCCP, valinomycin, and SQ109 on mycolic acid metabolism, cultures grown to mid-log phase (A600, 0.6 to 0.7) in LB-Tween 80 broth (M. smegmatis) or 7H9-OADC–0.05% tyloxapol plus supplements (M. tuberculosis H37Rv mc26206) were incubated with 3.2 to 12.5 μg/ml CCCP, 1 μM valinomycin, or 12.5 μg/ml SQ109 (19) for 3 h (M. smegmatis) to 16 h (M. tuberculosis) at 37°C with shaking. A concentration of 0.25 to 0.5 μCi/ml [1,2-14C]acetic acid (specific activity, 54.3 Ci/mol; PerkinElmer, Inc.) was added at the same time as the inhibitors. The total lipids and cell wall-bound mycolic acid methyl esters were prepared from treated and untreated cells and analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC), as described previously (19, 31).

The effects of SQ109, AU1235, and INH (0.2 and 0.5 μg/ml [4× and 10× the MIC, respectively]) on sulfolipid (SL), diacyltrehalose (DAT), polyacyltrehalose (PAT), phthiocerol dimycocerosate (PDIM), TMM, and trehalose dimycolate (TDM) synthesis was assessed by labeling SQ109-treated, AU1235-treated, INH-treated, and untreated M. tuberculosis H37Rv mc26206 cells with 0.5 μCi/ml [1-14C]propionate (specific activity, 55 Ci/mol; American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc.) or 0.5 μCi/ml [1,2-14C]acetate (specific activity, 54.3 Ci/mol; PerkinElmer) for 24 h at 37°C. Surface-exposed lipids were extracted from whole cells in water-saturated 1-butanol, as described previously (19), and the butanol-treated cells were then reextracted overnight with chloroform-methanol (2:1 [vol/vol]) to recover all remaining extractable lipids. The lipids from the butanol and chloroform-methanol fractions were resuspended in chloroform-methanol (2:1 [vol/vol]), and the lipid samples were analyzed by TLC. The TLCs were revealed and semiquantified using a PhosphorImager (Typhoon; GE Healthcare) and the ImageQuant TL 7.0 software (GE Healthcare). The effects of SQ109 and AU1235 on siderophore synthesis and export were assessed by labeling inhibitor-treated and untreated M. tuberculosis H37Rv mc26206 cells with 0.5 μCi/ml [7-14C]salicylic acid (specific activity, 47 Ci/mol; PerkinElmer), as described previously (32).

Membrane potential measurements in intact cells and determination of ΔpH by 31P NMR spectroscopy.

The effects of inhibitors on ΔΨ were determined by fluorescence quenching of the potential-sensitive probe 3,3′-dipropylthio-dicarbocyanine (DisC3 [5]), as described previously (22). The effects of inhibitors on ΔpH by 31P nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy in intact mycobacterial cells was determined as described by Li et al. (22).

Synthesis of AUs, 2418, and SQ109.

AUs and SQ109 were synthesized as described previously (4, 19, 33). For the synthesis of N-(1-adamantyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxamide (compound 2418), 1H-indole-2-carboxylic acid (134 mg, 0.83 mmol), N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) (435 μl, 2.50 mmol), N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-O-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)uronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) (253 mg, 1.00 mmol), and 1-adamantyl amine (378 mg, 2.50 mmol) were sequentially dissolved in methylene chloride (DCM) (3 ml) and stirred overnight at room temperature. The reaction mixture was diluted with CHCl3 and washed 3 times with water and brine. The combined aqueous layers were backwashed with CHCl3. The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4, followed by solvent removed under reduced-pressure conditions. The final product (51 mg [20.8%]) was isolated as a white solid by flash column chromatography using a 10 to 80% ethyl acetate (EtAc)-in-hexane gradient. 1H NMR (500 MHz, dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]-d6) δ = 1.68 (br s, 6H), 2.08 (br s, 9H), 7.02 (t, J = 10 Hz, 1H), 7.14 to 7.18 (m, 2H), 7.42 (d, J = 10 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (s, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 10 Hz, 1H), 11.42 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 28.87, 36.03, 41.03, 51.52, 102.73, 112.12, 119.52, 121.30, 123.02, 127.03, 132.60, 136.19, 160.40; electrospray ionization–high-resolution mass spectrometry (ESI-HRMS): [M + H]+ calculated for C19H23N2O, 295.1805; found, 295.1806.

RESULTS

Activities of MmpL3 inhibitors on nonreplicating M. tuberculosis bacilli.

BM212 is reported to kill nonreplicating M. tuberculosis bacilli grown under low-oxygen-tension conditions (MIC, 18.5 μM compared to 5 μM against replicating bacilli) (11), whereas indolecarboxamides are apparently devoid of such activity (17). SQ109, on the other hand, has been described as a potent inhibitor of the menaquinone synthesis enzymes MenA and MenG in vitro, displaying 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) in the 5 and 15 μM range, respectively (22). Because inhibitors of the menaquinone biosynthetic pathway, and of the 1,4-dihydroxy-2-napthoic acid nonaprenyl transferase MenA in particular, have been shown to display activities against nonreplicating M. tuberculosis bacilli (27), we tested whether SQ109 had any effect on M. tuberculosis cultured under low-oxygen-tension conditions (LORA assay based on the Wayne model) (26, 29) or under nutrient deprivation conditions in oxygen-rich medium (Loebel model) (30). Both models are thought to mimic some of the physical conditions encountered by persistent bacilli in lung lesions and have demonstrated the survival of M. tuberculosis for extended periods in a nonreplicative and drug-tolerant state. Strikingly, SQ109 displayed similar MICs against M. tuberculosis in the LORA model (MIC, 1.09 μg/ml; 3.3 μM) and in oxygen-rich medium (MABA assay; MIC, 0.76 μg/ml; 2.3 μM) (28) (Table 1). As shown in Fig. 2, SQ109 and the related compound DA5 (Fig. 1) also showed activity in the nutrient starvation model with 7 days of treatment with SQ109 at 50× the MIC, resulting in a 4-log reduction in the CFU counts in cultures that had been starved for 2 weeks (2.2-log reduction with DA5), as well as a 3.8-log reduction in the CFU counts in cultures starved for 6 weeks (3.3-log reduction with DA5) (Fig. 2). Thus, supporting recent observations made on the nonreplicating (streptomycin-starved) model strain M. tuberculosis 18b (22, 34), SQ109 kills hypoxic and nutrient-deprived nonreplicating bacilli. This property might account for the reported improvement in bacillary clearance observed in a mouse model of TB infection when SQ109 replaces EMB in drug combination regimens (7).

TABLE 1.

Drug susceptibilities of actively replicating versus oxygen-starved M. tuberculosisa

| Drug | MIC (μM) for M. tuberculosis |

|

|---|---|---|

| Replicating | Nonreplicating | |

| RIF | 0.05 | 1.41 |

| SQ109 | 2.37 | 3.35 |

| AU1235 | 0.31 | >310 |

| THPP-2 | 6.25 | >25 |

The MICs of RIF, SQ109, and AU1235 determined in the MABA and LORA assays (28, 29) are against virulent M. tuberculosis H37Rv. The MICs of THPP-2 are against M. tuberculosis H37Rv mc26206. The susceptibility of the actively replicating M. tuberculosis cells to this compound was determined in 7H9-OADC-Tween 80 broth using the resazurin microplate reduction assay, while that of the hypoxic nonreplicating bacilli was determined in Dubos Tween albumin medium, as described by Wayne and Hayes (26). The nonreplicating M. tuberculosis bacilli were exposed to THPP-2 for 7 days.

The adamantyl urea AU1235, in contrast, showed no activity on M. tuberculosis bacilli grown under low-oxygen-tension conditions (MIC, >100 μg/ml for AU1235) (Table 1). Furthermore, AU1235 and the indolecarboxamide 2418 had only minimal activity in the nutrient starvation model (0.7-log decrease in CFU upon treatment of 6-week-starved cultures with 50× MIC of AU1235 for 7 days, and 0.7-log decrease in CFU upon treatment of 2-week-starved cultures with 50× MIC of 2418 for 7 days), similar to the control drugs INH and RIF (Fig. 2b and c). This was in contrast to the tetrahydropyrazolopyrimidine THPP-2 and BM212, which at 50× the MIC led to a 3.9- and 3.0-log reduction in CFU, respectively, in cultures that had been starved for 2 weeks (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, however, THPP-2 showed no activity under low-oxygen-tension conditions at concentrations up to 25 μM (11 μg/ml) (Table 1). AU1235, THPP-2, 2418, BM212, INH, and RIF displayed, as expected, potent inhibitory activities on actively replicating bacilli (Fig. 2a and Table 1). Thus, MmpL3 inhibitors clearly differ in their abilities to kill nonreplicating hypoxic and nutrient-starved bacilli.

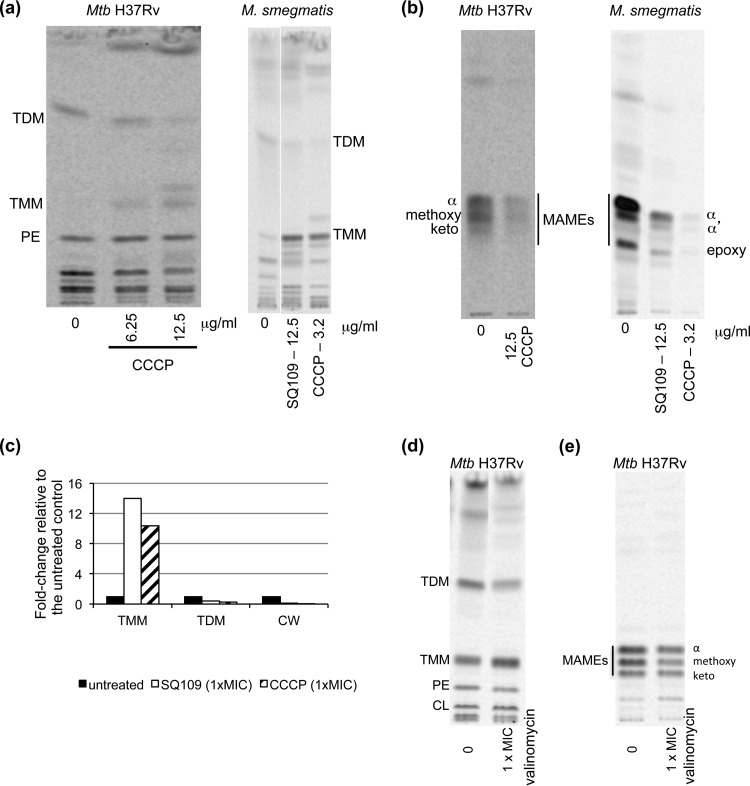

CCCP and valinomycin recapitulate the effect of MmpL3 inhibitors on mycolic acid transfer to their cell envelope acceptors.

As noted above, MmpL proteins belong to the RND superfamily of integral membrane transporters, which, in Gram-negative bacteria, function as proton-drug antiporters requiring PMF rather than ATP hydrolysis for activity (23–25). The PMF consists of two components: an electrical charge gradient (also known as membrane potential [Δψ]) and the transmembrane proton concentration gradient (ΔpH). SQ109 dissipates both of these components (22), collapsing PMF in mycobacteria (Table 2). To investigate whether PMF dissipation may lead to the inhibition of MmpL3, M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis cells were treated with the uncoupler carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP), which, like SQ109, disrupts both ΔpH and Δψ (Table 2), and mycolic acid transfer onto arabinogalactan and TDM in CCCP-treated and untreated cells was investigated by metabolic labeling with [1,2-14C]acetic acid, as previously reported (19). The results clearly show that CCCP treatment recapitulates the effect of SQ109 in both M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis (Fig. 3 and 4A) (9). At a concentration of 12.5 μg/ml (2× the MIC), CCCP caused a 50-fold decrease in the transfer of mycolic acids onto arabinogalactan, a 3.7-fold decrease in TDM formation, and a 10-fold intracellular accumulation of TMM in M. tuberculosis. In M. smegmatis, the effects of CCCP treatment (1× the MIC [3.2 μg/ml]) on TDM formation and TMM accumulation were of similar magnitude as those observed upon treatment with 1× the MIC of SQ109 (12.5 μg/ml), and CCCP almost completely abolished mycolic acid transfer onto arabinogalactan (Fig. 3). Exposing M. tuberculosis to valinomycin (1 μM [1× the MIC]), a K+ ionophore that disrupts the PMF through the dissipation of Δψ, also led to a clear inhibition of MmpL3, as demonstrated by the decrease of mycolic transfer onto arabinogalactan and TDM in the treated cells (Fig. 3). Although these results do not preclude a direct effect of SQ109 on MmpL3, they indicate that the ability of this compound to disrupt the PMF may account for the inhibition of TMM export, and it suggests that other MmpL family members might be inhibited by the collapse of PMF as well.

TABLE 2.

31P NMR-derived ΔpH collapse in inhibitor and ionophore-treated M. smegmatis cellsa

| Compound | pH outside | pH inside | ΔpH |

|---|---|---|---|

| No drug | 6.82 | 7.09 | 0.26 |

| Isoniazid | 6.79 | 7.08 | 0.29 |

| Rifampin | 6.81 | 7.08 | 0.27 |

| Streptomycin | 6.77 | 7.05 | 0.28 |

| CCCP (2× MIC) | 6.85 | 6.85 | 0 |

| Nigericin (20 μM) | 6.82 | 6.82 | 0 |

| Valinomycin (33 μM) | 6.83 | 7.07 | 0.24 |

| Ro 48-8071 (2× MIC) | 6.83 | 6.83 | 0 |

| SQ109 (2× MIC) | 6.81 | 6.81 | 0 |

| AU1235 (2× MIC) | 6.82 | 6.82 | 0 |

| BM212 (1× MIC) | 6.85 | 6.85 | 0 |

| 2418 (2× MIC) | 6.81 | 6.81 | 0 |

| THPP-2 (2× MIC)b | 6.82 | 6.82 | 0 |

The average pH values were calculated from the equation pH = 6.75 + log (d − 10.85)/(13.25 − d) (49), where d is the 31P NMR chemical shift difference between peaks and that of the α phosphorus on ATP. The error is estimated to be no more than ±0.02 pH units.

THPP-2 was tested against M. tuberculosis H37Rv mc26206 cells, since this compound did not show any inhibitory effect against M. smegmatis in culture at the highest concentration tested (22 μg/ml).

FIG 3.

Effect of CCCP on the transfer of mycolic acids onto its cell envelope acceptors. (a) Lipid analysis of untreated, SQ109-treated, and CCCP-treated M. smegmatis and M. Tuberculosis (Mtb) H37Rv mc26206 cells. The same volume of [14C]acetate-labeled lipids from bacterial cells treated with CCCP or SQ109, or untreated cells were analyzed by TLC in the solvent system (CHCl3/CH3OH/H2O, 20:4:0.5) and revealed by phosphorimaging. PE, phosphatidylethanolamine. (b) TLC analysis of cell wall-bound mycolic acid methyl esters (MAMEs) prepared from the same untreated, SQ109-treated, and CCCP-treated M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis H37Rv mc26206 cells as in panel a. The TLC plates were developed thrice in the solvent system (n-hexane/ethyl acetate, 95:5) and revealed by phosphorimaging. (c) The amount of radioactivity incorporated in TMM, TDM, and cell wall-bound mycolic acids (CW) in the M. smegmatis treated and untreated cells was semiquantified using a PhosphorImager, and the results (expressed as a fold increase or decrease over the value measured in the untreated control arbitrarily set to 1) are presented as histograms. (d) Lipid analysis of untreated and valinomycin-treated M. tuberculosis H37Rv mc26206 cells. The same volume of [14C]acetate-labeled total lipids was analyzed by TLC for each sample as described in panel a. (e) TLC analysis as in panel b of cell wall-bound mycolic acid methyl esters (MAMEs) prepared from the same untreated and valinomycin-treated M. tuberculosis H37Rv mc26206 cells.

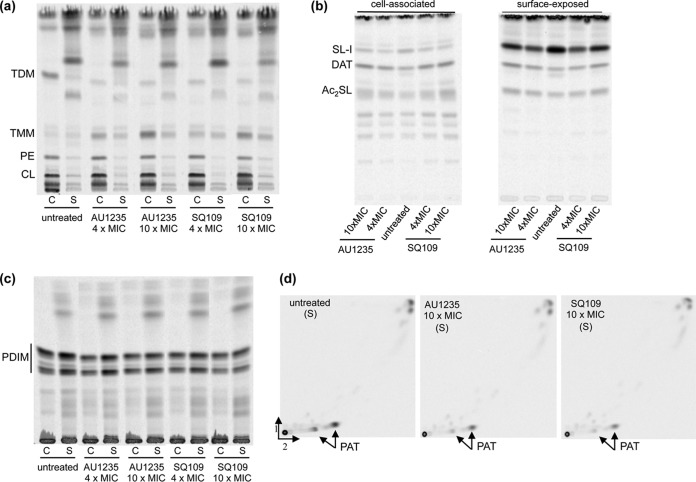

FIG 4.

Effects of SQ109 and AU1235 on the biosynthesis and export of sulfolipids, di- and polyacyltrehaloses, and phthiocerol dimycocerosates in M. tuberculosis. Lipid analysis of untreated, SQ109-treated, and AU1235-treated M. tuberculosis H37Rv mc26206 cells. Surface-exposed (S) and cell-associated (C) [14C]acetate-labeled and [1-14C]propionate-labeled lipids from bacterial cultures treated with SQ109 or AU1235 or untreated were analyzed by TLC in the solvent systems (CHCl3/CH3OH/H2O [20:4:0.5]) ([14C]-acetate-labeled lipids) (a), (CHCl3/CH3OH/H2O [60:30:6]) ([1-14C]propionate-labeled lipids) (b), (petroleum ether [60/80°C]/ethyl acetate [98:2]; three developments) ([1-14C]propionate-labeled lipids) (c), first dimension: (petroleum ether [60/80°C]/acetone (92:8); three developments); second dimension: (acetone-toluene [95:5]) ([1-14C]propionate-labeled lipids), and revealed by autoradiography (d). The same volume of samples was loaded per lane. The amount of radioactivity incorporated in SL-I, the diacylated sulfolipid precursor (Ac2SL), DAT, PAT, and PDIM in the treated and untreated cells was semiquantified using a PhosphorImager, and the results are presented in Table 3. CL, cardiolipin; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine.

Effects of SQ109 on the activities of other MmpL transporters.

Consistent with the above findings, further metabolic labeling of SQ109-treated M. tuberculosis cells with [1-14C]propionate indicated that other (nonessential) biosynthetic pathways dependent on MmpL proteins were also affected by the drug, albeit to various degrees. The exposure of log-phase M. tuberculosis mc26206 cultures to 10× the MIC of SQ109 for 24 h inhibited the formation of TDM in whole cells by 88%, that of PAT by 68%, that of sulfolipid-I (SL-I) by 20%, and that of PDIM by 47% (Fig. 4 and Table 3). A build-up of TMM (211% increase over the untreated control), DAT (73% increase over the untreated control), and diacylated SL precursors (145% increase over the control), particularly in the innermost layers of the cell envelope (Fig. a, b, and d), accompanied the decreases in TDM, SL-I, and PAT biosynthesis. The intracellular accumulation of the diacylated forms of SL has been reported in mmpL8 knockout mutants of M. tuberculosis (35, 36). Likewise, DAT are biosynthetic precursors of PAT and, together with PAT, are the likely substrates of MmpL10 (37, 38). In comparison, INH treatment (at 4× and 10× the MIC) displayed the expected inhibitory effect on TMM and TDM formation (72 and 82%, respectively) and impacted, to various degrees, the biosynthesis of other lipids as a result of the general decrease in the metabolic activity of the cells following drug treatment, but it did not cause a build-up of diacylated SL and DAT (suggestive of the absence of MmpL8 and MmpL10 inhibition) (Table 3; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Thus, the effects of SQ109 on TDM, SL-I, and DAT/PAT synthesis are specific to this compound and presumably the result of the reduced activity of MmpL3, MmpL8 (35, 36), and MmpL10, respectively, due to the disruption of the PMF. Whether SQ109 had an inhibitory effect on MmpL7 and thus PDIM synthesis (39, 40) was not concluded from our studies, as INH displayed an even stronger inhibitory effect than SQ109 on the biosynthesis of these lipids (Table 3). Likewise, an assessment of the effect of SQ109 on mycobactins and carboxymycobactins known to be reliant on MmpL proteins for export (41) failed to show a clear effect of the inhibitor on the secretion of these compounds, most likely due to the shutdown of siderophore synthesis that accompanies a deficiency in their export (41) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Quantitative assessment of the effects of SQ109 on the biosynthesis and export of sulfolipids, di- and polyacyltrehaloses, and phthiocerol dimycocerosates in M. tuberculosis

| Whole-cell treatmenta | % increase/decrease radioactivity compared to control forb: |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMM | TDM | DAT | PAT | Ac2SL | SL-I | PDIM | MBT | |

| SQ109 | 211 | −88 | 73 | −68 | 145 | −20 | −47 | −16 |

| AU1235 | 318 | −84 | 70 | −44 | 88 | −19 | −29 | −13 |

| INH | −72 | −82 | −18 | −43 | −9 | −25 | −63 | NDc |

All were at 10× the MIC.

The amount of radioactivity incorporated by whole cells (including cell-associated and surface-exposed materials) in TMM, TDM, SL-I, the diacylated SL precursor (Ac2SL), DAT, PAT, PDIM, and (carboxy)mycobactins (MBT) of the M. tuberculosis SQ109-, AU1235-, and INH-treated cells was analyzed by TLC (Fig. 4 and data not shown) and semiquantified using a PhosphorImager. The results are expressed as percent increases or decreases of the values measured in the untreated control.

ND, not determined.

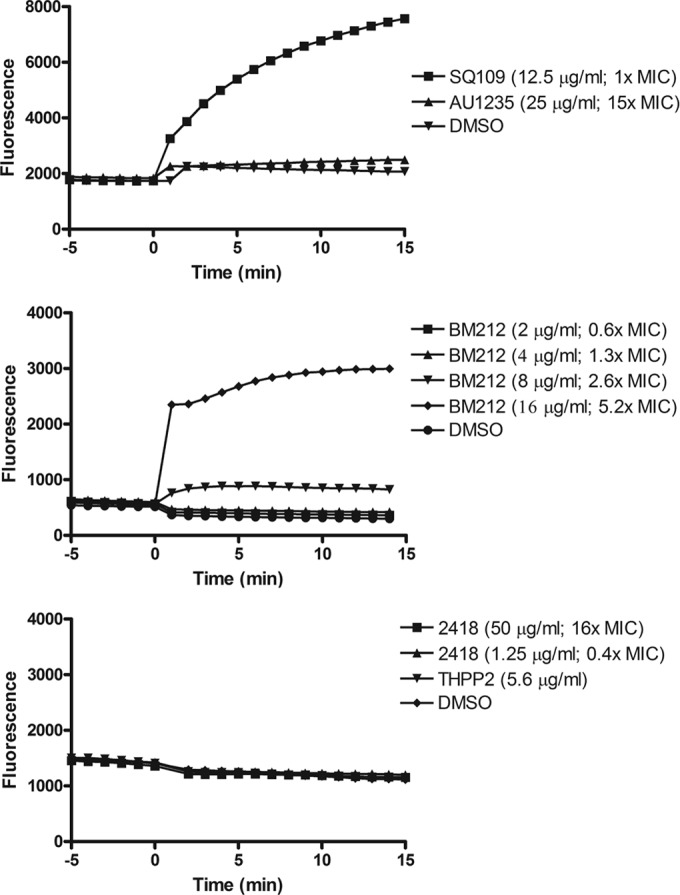

Effects of SQ109, adamantyl ureas, BM212, 2418, and THPP-2 on the proton motive force.

A number of structurally diverse hydrophobic inhibitors have been reported in the last 2 years to target the essential TMM transporter MmpL3 (7, 9–19, 21). Various explanations have been advanced for this apparent bias, including the fact that MmpL3 may represent a particularly vulnerable and druggable target and/or one in which spontaneous resistance-conferring mutations may be easier to achieve (12). Another hypothesis has to do with the hydrophobicity of the small molecules used in the high-throughput screens that favored their concentration in the membrane-driving inhibition of essential membrane processes through more- or less-specific interactions with their target (42). The finding that SQ109 probably acts indirectly on the transporter by collapsing the PMF required to drive TMM export prompted us to test whether any other series of inhibitors act similarly. Although there are few structural similarities between SQ109 and CCCP, it has been shown that they both function as uncouplers in mycobacteria (22). The one feature that stands out in terms of structural similarity is the presence of a nitrogen atom that is protonatable at physiological pH (Fig. 1). The MmpL3 inhibitors DA5 (9), BM212 (10), and the MenA inhibitor Ro 48-8071 (27) also contain a nitrogen atom that is protonatable at physiological pH, suggesting that they may have a similar effect on PMF. However, the adamantyl urea AU1235 (19), the tetrahydropyrazolopyrimidine inhibitor THPP-2 (14), and the indolecarboxamide 2418 do not contain nitrogens that are protonatable at physiological pH (Fig. 1), suggesting a possible alternate mechanism of action. Therefore, we tested these compounds for their effect on the PMF of intact mycobacterial cells. Prior to performing these experiments, the inhibitory activities of THPP-2 and compound 2418 on TMM translocation were verified by the metabolic labeling of treated M. tuberculosis or M. smegmatis cells, as this had not been confirmed (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). BM212 and SQ109 that have a nitrogen atom that can be protonated at physiological pH dissipated the charge (ΔΨ) (Fig. 5) and the proton gradient (ΔpH) (Table 2) across the membrane in live bacteria, suggesting that they behave like protonophores rather than ionophores, such as valinomycin, which only collapse ΔΨ by acting as K+ transporters. The other compounds (AU1235, THPP-2, and 2418) did not dissipate ΔΨ at any concentration tested (Fig. 5); however, all of these compounds collapsed the ΔpH at concentrations near (2×) the MIC (Table 2).

FIG 5.

Effects of inhibitors on ΔΨ dissipation in M. smegmatis cells. DisC3 (5) fluorescence is quenched in the presence of the cells due to intercalation into the membrane. The addition of compounds (at time zero) that dissipate ΔΨ causes an increase in fluorescence due to dissociation of the dye from the membranes. Note: the MIC of THPP-2 against M. smegmatis is >22 μg/ml (the highest concentration tested here).

Thus, like SQ109, all other series of inhibitors tested in this study collapsed the PMF. Consistent with this activity, AU1235, like SQ109, inhibited the activities of several MmpL proteins in addition to MmpL3 in whole M. tuberculosis cells, resulting in marked defects in the synthesis of PAT and SL-I that accompanied the intracellular build-up of diacylated SL and DAT (Fig. 4 and Table 3).

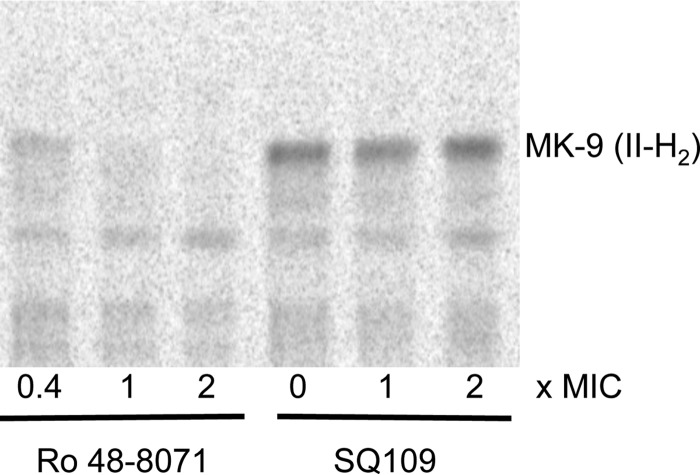

Effect of SQ109 on menaquinone biosynthesis in whole M. tuberculosis cells.

Finally, to assess whether the reported inhibition of menaquinone biosynthetic enzymes by SQ109 in vitro (22) may account for or at least contribute to the mycobactericidal activity of this compound, SQ109-treated and untreated log-phase M. tuberculosis cultures were metabolically labeled with l-[methyl-14C]methionine, and the de novo synthesis of menaquinones in whole cells was monitored by TLC. The MenA inhibitor Ro 48-8071 (Fig. 1) was used as a positive control for inhibition (27). While Ro 48-8071 strongly inhibited the synthesis of the dominant mycobacterial menaquinone MK-9 (II-H2) at 0.4×, 1×, and 2× the MIC, SQ109 used at concentrations up to 2× the MIC (1.6 μg/ml) showed no such activity (Fig. 6). Thus, in spite of SQ109 being a potent inhibitor of the MenA and MenG enzymes in vitro (22), the inhibition of menaquinone synthesis was not observed by metabolic labeling under the conditions reported here. It is possible that the effect of SQ109 on menaquinone synthesis in treated cells is masked by the inhibition of another more vulnerable target(s). Alternatively, the concentration of SQ109 reaching the Men enzymes in intact cells may be insufficient to abolish menaquinone synthesis. In light of the results presented here, a possible explanation for externally added menaquinones rescuing the growth of M. tuberculosis exposed to SQ109 (22) might have to do with menaquinones partially relieving the PMF dissipation caused by SQ109.

FIG 6.

Menaquinone biosynthesis in untreated, Ro 48-8071-treated, and SQ109-treated M. tuberculosis cells. Shown is a TLC analysis of neutral lipids isolated from M. tuberculosis H37Rv mc26206 after metabolic labeling with l-[methyl-14C]methionine in the presence of the indicated concentrations of Ro 48-8071 and SQ109. Menaquinone [MK-9 (II-H2)] was identified by comigration with an authentic standard (27). The MIC of Ro 48-8071 against M. tuberculosis H37Rv mc26206 under the culture conditions used in this experiment is 25 μg/ml; the MIC of SQ109 is 0.8 μg/ml.

DISCUSSION

The MmpL3 inhibitors, SQ109, BM212, indolecarboxamides, AUs, and THPPs all abolish PMF-driven translocation processes through the dissipation of the transmembrane electrochemical proton gradient. While our studies do not preclude a possible selectivity of some of these compounds for MmpL3 (or other cellular targets), they provide the first unifying hypothesis for the apparent promiscuity of this transporter. They also serve as a cautionary tale that the metabolic labeling of drug-treated cells and the whole-genome sequencing of spontaneous resistant mutants do not necessarily point to the primary target of an inhibitor, even though these approaches often provide useful information about possible mechanisms of resistance.

The apparent indirect mechanism of inhibition of MmpL3 by all five series of compounds tested in this study and the effects that these compounds are likely to have on many other essential PMF-dependent cellular processes beyond TMM translocation raise the question of why spontaneous resistance-conferring mutations map to MmpL3 (9, 10). Based on our metabolic labeling of CCCP-, valinomycin-, and inhibitor-treated cells, mycolic acid transfer to their cell envelope acceptors is, among lipid-related processes, clearly the most dramatically affected by all compounds (Fig. 3 and 4 and Table 3; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). This finding may reflect the lower abundance of MmpL3 relative to other targets affected by the inhibitors and/or the fact that MmpL3 is a more vulnerable target. Experiments in our laboratories are in progress to assess these hypotheses. As a result, spontaneous resistant mutants may tend to accumulate mutations in MmpL3 as their first response to drug treatment to alleviate the early toxic effects of the inhibitors. The modest level of resistance conferred by most of these mutations (a maximum 16- to 33-fold increase in MIC in the case of BM212 and derivatives, 8-fold in the case of AUs, 4- to 8-fold in the case of SQ109, 4- to 122-fold in the case of indolecarboxamides, and 8- to 70-fold in the case of THPPs) (9–11, 13, 14, 17–19) indicates that this response is, in most cases at least, limited in efficacy, as one would expect if the inhibitors impact a variety of other PMF-dependent metabolic processes individually or collectively required for optimal bacterial growth. How these mutations may help relieve the loss of energy suffered by MmpL3 upon dissipation of the transmembrane proton gradient is unclear, but it is noteworthy that most of them are located within or in the immediate vicinity of the 4th, 10th, 11th, and 12th transmembrane domains, close to residues thought to participate in the electrochemical proton gradient that provides energy to the transporter for substrate translocation (D251, R259, D640, Y641, D710, and R715) (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Seven of the residues affected by these mutations (Q40, A249, S288, G253, L567, V684, and A700) were found in mutants displaying resistance to two or three different series of compounds (see Fig. S3). Furthermore, the MIC studies conducted here and in earlier publications on AU1235-, SQ109-, and indolecarboxamide-resistant isolates harboring nonsynonymous mutations in MmpL3 (9, 18, 19) clearly point to the existence of cross-resistance between the MmpL3 inhibitors (Table 4) (18). Whether some of these mutations allow MmpL3 to function in the presence of low concentrations of protonophores remains to be established.

TABLE 4.

Cross-resistance of adamantyl urea and SQ109 spontaneous resistant mutants of M. tuberculosis H37Rv to AU1235, BM212, and SQ109

| Isolatea | MIC (μg/ml) forb: |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WTc | AU2 | AU3 | AU4 | AU5 | AU6 | DA5_1 | DA5_2 | DA8_1 | DA8_2 | |

| AU1235 | 0.2–0.4 | >1.6 | >1.6 | >1.6 | >1.6 | >1.6 | >1.6 | 1.6 | >1.6 | 1.6 |

| BM212 | 1.25 | 10 | 5–10 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 5 |

| SQ109 | 1 | NDd | ND | ND | ND | ND | 4 | 2 | 2–8 | 2–4 |

The mutation for the isolates AU2, AU3, AU4, AU5, and AU6 is G253E, that for DA5_1 and DA5_2 is A700T, that for DA8_1 is L567P, and that for DA8_2 is Q40R. The adamantyl urea (isolates AU2, AU3, AU4, AU5, and AU6) and SQ109 (isolates DA5_1, DA5_2, DA8_1, and DA8_2) spontaneous resistant mutants of M. tuberculosis H37Rv were reported previously (9, 19).

The MICs, defined as the concentration of inhibitors that inhibited 100% of the growth and metabolic activity of the various M. tuberculosis H37Rv isolates, were determined in 96-well microtiter plates using the colorimetric resazurin assay in 7H9-OADC-Tween 80 broth at 37°C.

The wild-type (WT) strain was M. tuberculosis H37Rv TMC102.

ND, not determined.

Compared to other inhibitors, the broader spectra of activity of SQ109 and BM212 and the activities of these compounds on hypoxic and nutrient-starved nonreplicating M. tuberculosis cells may reflect their ability to dissipate both the transmembrane proton concentration gradient (ΔpH) and the membrane potential (Δψ) (while other compounds dissipate ΔpH only) and/or the existence of other lethal targets in the cells whose identities remain to be established. These hypotheses may be particularly true for SQ109, whose very low rate of spontaneous resistance mutation in M. tuberculosis (2.55 × 10−11) (7, 9) compared to that of other MmpL3 inhibitors (mutation rate range, 1 × 10−8 to 1 × 10−9) (10, 17, 19) is suggestive of the inhibition of multiple essential cellular processes and/or a nonspecific uncoupling effect. That SQ109 is more than a nonspecific uncoupler and probably inhibits specific cell envelope-related targets is suggested by the strong induction of the iniBAC gene cluster in SQ109-treated M. tuberculosis cells (4, 8), an effect not observed in CCCP- or nigericin-treated cells (8). Clearly, gaining further insights into the mechanism of inhibition of M. tuberculosis by these compounds and their potential selectivity for MmpL3 and other essential targets will be critical to their further development and the appreciation of whether pathogen selectivity may be achieved. For now, the MmpL3 inhibitors reported to date can be added to the growing list of antimycobacterial compounds, including TMC207, pyrazinamide, and clofazimine, whose potencies against actively replicating and, in some cases, nonreplicating M. tuberculosis bacilli have been associated with their ability to perturb membrane permeability and/or energy production (43–47). Despite the challenges ahead, these findings should provide a stimulus to optimize lipophilic membrane-active compounds to become novel anti-TB agents, as this has successfully been done in the past to treat other bacterial infections (45).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants AI063054 and AI049151 and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

We are grateful to W. R. Jacobs, Jr. (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, NY, USA) for the kind gift of M. tuberculosis H37Rv mc26206, H. Boshoff (NIH/NIAID) for the SQ109-resistant mutants of M. tuberculosis, D. R. Sherman (Seattle Biomedical Research Institute, USA) for THPP-2, and G. Poce (Sapienza Universita di Roma, Italy) for compound BM212.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 August 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.03229-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abubakar I, Zignol M, Falzon D, Raviglione M, Ditiu L, Masham S, Adetifa I, Ford N, Cox H, Lawn SD, Marais BJ, McHugh TD, Mwaba P, Bates M, Lipman M, Zijenah L, Logan S, McNerney R, Zumla A, Sarda K, Nahid P, Hoelscher M, Pletschette M, Memish ZA, Kim P, Hafner R, Cole S, Migliori GB, Maeurer M, Schito M, Zumla A. 2013. Drug-resistant tuberculosis: time for visionary political leadership. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13:529–539. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sala C, Hartkoorn RC. 2011. Tuberculosis drugs: new candidates and how to find more. Future Microbiol. 6:617–633. 10.2217/fmb.11.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson M, McNeil MR, Brennan PJ. 2013. Progress in targeting cell envelope biogenesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Future Microbiol. 8:855–875. 10.2217/fmb.13.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee RE, Protopopova M, Crooks E, Slayden RA, Terrot M, Barry CE., III 2003. Combinatorial lead optimization of [1,2]-diamines based on ethambutol as potential antituberculosis preclinical candidates. J. Comb. Chem. 5:172–187. 10.1021/cc020071p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Protopopova M, Hanrahan C, Nikonenko B, Samala R, Chen P, Gearhart J, Einck L, Nacy CA. 2005. Identification of a new antitubercular drug candidate, SQ109, from a combinatorial library of 1,2-ethylenediamines. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:968–974. 10.1093/jac/dki319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jia L, Tomaszewski JE, Hanrahan C, Coward L, Noker P, Gorman G, Nikonenko B, Protopopova M. 2005. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of SQ109, a new diamine-based antitubercular drug. Br. J. Pharmacol. 144:80–87. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sacksteder KA, Protopopova M, Barry CE, III, Andries K, Nacy CA. 2012. Discovery and development of SQ109: a new antitubercular drug with a novel mechanism of action. Future Microbiol. 7:823–837. 10.2217/fmb.12.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boshoff HI, Myers TG, Copp BR, McNeil MR, Wilson MA, Barry CE., III 2004. The transcriptional responses of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to inhibitors of metabolism: novel insights into drug mechanisms of action. J. Biol. Chem. 279:40174–40184. 10.1074/jbc.M406796200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tahlan K, Wilson R, Kastrinsky DB, Arora K, Nair V, Fischer E, Barnes SW, Walker JR, Alland D, Barry CE, III, Boshoff HI. 2012. SQ109 targets MmpL3, a membrane transporter of trehalose monomycolate involved in mycolic acid donation to the cell wall core of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:1797–1809. 10.1128/AAC.05708-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.La Rosa V, Poce G, Canseco JO, Buroni S, Pasca MR, Biava M, Raju RM, Porretta GC, Alfonso S, Battilocchio C, Javid B, Sorrentino F, Ioerger TR, Sacchettini JC, Manetti F, Botta M, De Logu A, Rubin EJ, De Rossi E. 2012. MmpL3 is the cellular target of the antitubercular pyrrole Derivative BM212. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:324–331. 10.1128/AAC.05270-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poce G, Bates RH, Alfonso S, Cocozza M, Porretta GC, Ballell L, Rullas J, Ortega F, De Logu A, Agus E, La Rosa V, Pasca MR, De Rossi E, Wae B, Franzblau SG, Manetti F, Botta M, Biava M. 2013. Improved BM212 MmpL3 inhibitor analogue shows efficacy in acute murine model of tuberculosis infection. PLoS One 8:e56980. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanley SA, Grant SS, Kawate T, Iwase N, Shimizu M, Wivagg C, Silvis M, Kazyanskaya E, Aquadro J, Golas A, Fitzgerald M, Dai H, Zhang L, Hung DT. 2012. Identification of novel inhibitors of M. tuberculosis growth using whole cell based high-throughput screening. ACS Chem. Biol. 7:1377–1384. 10.1021/cb300151m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Remuiñán MJ, Pérez-Herrán E, Rullás J, Alemparte C, Martínez-Hoyos M, Dow DJ, Afari J, Mehta N, Esquivias J, Jiménez E, Ortega-Muro F, Fraile-Gabaldón MT, Spivey VL, Loman NJ, Pallen MJ, Constantinidou C, Minick DJ, Cacho M, Rebollo-López MJ, González C, Sousa V, Angulo-Barturen I, Mendoza-Losana A, Barros D, Besra GS, Ballell L, Cammack N. 2013. Tetrahydropyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine-3-carboxamide and N-benzyl-6′,7′-dihydrospiro[piperidine-4,4′-thieno[3,2-c]pyran] analogues with bactericidal efficacy against Mycobacterium tuberculosis targeting MmpL3. PLoS One 8:e60933. 10.1371/journal.pone.0060933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ioerger TR, O'Malley T, Liao R, Guinn KM, Hickey MJ, Mohaideen N, Murphy KC, Boshoff HI, Mizrahi V, Rubin EJ, Sassetti CM, Barry CE, III, Sherman DR, Parish T, Sacchettini JC. 2013. Identification of new drug targets and resistance mechanisms in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One 8:e75245. 10.1371/journal.pone.0075245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kondreddi RR, Jiricek J, Rao SP, Lakshminarayana SB, Camacho LR, Rao R, Herve M, Bifani P, Ma NL, Kuhen K, Goh A, Chatterjee AK, Dick T, Diagana TT, Manjunatha UH, Smith PW. 2013. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of indole-2-carboxamides: a promising class of antituberculosis agents. J. Med. Chem. 56:8849–8859. 10.1021/jm4012774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Onajole OK, Pieroni M, Tipparaju SK, Lun S, Stec J, Chen G, Gunosewoyo H, Guo H, Ammerman NC, Bishai WR, Kozikowski AP. 2013. Preliminary structure-activity relationships and biological evaluation of novel antitubercular indolecarboxamide derivatives against drug-susceptible and drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains. J. Med. Chem. 56:4093–4103. 10.1021/jm4003878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao SP, Lakshminarayana SB, Kondreddi RR, Herve M, Camacho LR, Bifani P, Kalapala SK, Jiricek J, Ma NL, Tan BH, Ng SH, Nanjundappa M, Ravindran S, Seah PG, Thayalan P, Lim SH, Lee BH, Goh A, Barnes WS, Chen Z, Gagaring K, Chatterjee AK, Pethe K, Kuhen K, Walker J, Feng G, Babu S, Zhang L, Blasco F, Beer D, Weaver M, Dartois V, Glynne R, Dick T, Smith PW, Diagana TT, Manjunatha UH. 2013. Indolecarboxamide is a preclinical candidate for treating multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 5:214ra168. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lun S, Guo H, Onajole OK, Pieroni M, Gunosewoyo H, Chen G, Tipparaju SK, Ammerman NC, Kozikowski AP, Bishai WR. 2013. Indoleamides are active against drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 4:2907. 10.1038/ncomms3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grzegorzewicz AE, Pham H, Gundi VA, Scherman MS, North EJ, Hess T, Jones V, Gruppo V, Born SE, Korduláková J, Chavadi SS, Morisseau C, Lenaerts AJ, Lee RE, McNeil MR, Jackson M. 2012. Inhibition of mycolic acid transport across the Mycobacterium tuberculosis plasma membrane. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8:334–341. 10.1038/nchembio.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biava M, Porretta GC, Manetti F. 2007. New derivatives of BM212: a class of antimycobacterial compounds based on the pyrrole ring as a scaffold. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 7:65–78. 10.2174/138955707779317786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballell L, Bates RH, Young RJ, Alvarez-Gomez D, Alvarez-Ruiz E, Barroso V, Blanco D, Crespo B, Escribano J, González R, Lozano S, Huss S, Santos-Villarejo A, Martín-Plaza JJ, Mendoza A, Rebollo-Lopez MJ, Remuiñan-Blanco M, Lavandera JL, Pérez-Herran E, Gamo-Benito FJ, García-Bustos JF, Barros D, Castro JP, Cammack N. 2013. Fueling open-source drug discovery: 177 small-molecule leads against tuberculosis. ChemMedChem 8:313–321. 10.1002/cmdc.201200428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li K, Schurig-Briccio LA, Feng X, Upadhyay A, Pujari V, Lechartier B, Fontes F, Yang H, Rao G, Zhu W, Gulati A, No JH, Cintra G, Bogue S, Liu YL, Molohon K, Orlean P, Mitchell DA, Freitas-Junior L, Ren F, Sun H, Jiang T, Li Y, Guo RT, Cole ST, Gennis RB, Crick DC, Oldfield E. 2014. Multitarget drug discovery for tuberculosis and other infectious diseases. J. Med. Chem. 57:3126–3139. 10.1021/jm500131s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paulsen IT, Brown MH, Skurray RA. 1996. Proton-dependent multidrug efflux systems. Microbiol. Rev. 60:575–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tseng TT, Gratwick KS, Kollman J, Park D, Nies DH, Goffeau A, Saier MH., Jr 1999. The RND permease superfamily: an ancient, ubiquitous and diverse family that includes human disease and development proteins. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1:107–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murakami S. 2008. Multidrug efflux transporter, AcrB—the pumping mechanism. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18:459–465. 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wayne LG, Hayes LG. 1996. An in vitro model for sequential study of shiftdown of Mycobacterium tuberculosis through two stages of nonreplicating persistence. Infect. Immun. 64:2062–2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dhiman RK, Mahapatra S, Slayden RA, Boyne ME, Lenaerts A, Hinshaw JC, Angala SK, Chatterjee D, Biswas K, Narayanasamy P, Kurosu M, Crick DC. 2009. Menaquinone synthesis is critical for maintaining mycobacterial viability during exponential growth and recovery from non-replicating persistence. Mol. Microbiol. 72:85–97. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collins LA, Franzblau SG. 1997. Microplate Alamar blue assay versus Bactec 460 system for high-throughput screening of compounds against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1004–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho SH, Warit S, Wan B, Hwang CH, Pauli GF, Franzblau SG. 2007. Low-oxygen-recovery assay for high-throughput screening of compounds against nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1380–1385. 10.1128/AAC.00055-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Betts JC, Lukey PT, Robb LC, McAdam RA, Duncan K. 2002. Evaluation of a nutrient starvation model of Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence by gene and protein expression profiling. Mol. Microbiol. 43:717–731. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stadthagen G, Korduláková J, Griffin R, Constant P, Bottová I, Barilone N, Gicquel B, Daffé M, Jackson M. 2005. p-Hydroxybenzoic acid synthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 280:40699–40706. 10.1074/jbc.M508332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Voss JJ, Rutter K, Schroeder BG, Su H, Zhu Y, Barry CE., III 2000. The salicylate-derived mycobactin siderophores of Mycobacterium tuberculosis are essential for growth in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:1252–1257. 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.North EJ, Scherman MS, Bruhn DF, Scarborough JS, Maddox MM, Jones V, Grzegorzewicz A, Yang L, Hess T, Morisseau C, Jackson M, McNeil MR, Lee RE. 2013. Design, synthesis and anti-tuberculosis activity of 1-adamantyl-3-heteroaryl ureas with improved in vitro pharmacokinetic properties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 21:2587–2599. 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sala C, Dhar N, Hartkoorn RC, Zhang M, Ha YH, Schneider P, Cole ST. 2010. Simple model for testing drugs against nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4150–4158. 10.1128/AAC.00821-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Converse SE, Mougous JD, Leavell MD, Leary JA, Bertozzi CR, Cox JS. 2003. MmpL8 is required for sulfolipid-1 biosynthesis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:6121–6126. 10.1073/pnas.1030024100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Domenech P, Reed MB, Dowd CS, Manca C, Kaplan G, Barry CE., III 2004. The role of MmpL8 in sulfatide biogenesis and virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 279:21257–21265. 10.1074/jbc.M400324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jain M, Chow ED, Cox JS. 2008. The MmpL protein family, p 201–210 In Daffé M, Reyrat JM. (ed), The mycobacterial cell envelope. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hatzios SK, Schelle MW, Holsclaw CM, Behrens CR, Botyanszki Z, Lin FL, Carlson BL, Kumar P, Leary JA, Bertozzi CR. 2009. PapA3 is an acyltransferase required for polyacyltrehalose biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 284:12745–12751. 10.1074/jbc.M809088200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cox JS, Chen B, McNeil M, Jacobs WR., Jr 1999. Complex lipid determines tissue-specific replication of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Nature 402:79–83. 10.1038/47042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Camacho LR, Constant P, Raynaud C, Lanéelle MA, Triccas JA, Gicquel B, Daffé M, Guilhot C. 2001. Analysis of the phthiocerol dimycocerosate locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Evidence that this lipid is involved in the cell wall permeability barrier. J. Biol. Chem. 276:19845–19854. 10.1074/jbc.M100662200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wells RM, Jones CM, Xi Z, Speer A, Danilchanka O, Doornbos KS, Sun P, Wu F, Tian C, Niederweis M. 2013. Discovery of a siderophore export system essential for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003120. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldman RC. 2013. Why are membrane targets discovered by phenotypic screens and genome sequencing in Mycobacterium tuberculosis? Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 93:569–588. 10.1016/j.tube.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Wade MM, Scorpio A, Zhang H, Sun Z. 2003. Mode of action of pyrazinamide: disruption of Mycobacterium tuberculosis membrane transport and energetics by pyrazinoic acid. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:790–795. 10.1093/jac/dkg446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andries K, Verhasselt P, Guillemont J, Göhlmann HWH, Neefs JM, Winkler H, Van Gestel J, Timmerman P, Zhu M, Lee E, Williams P, de Chaffoy D, Huitric E, Hoffner S, Cambau E, Truffot-Pernot C, Lounis N, Jarlier V. 2005. A diarylquinoline drug active on the ATP synthase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 307:223–227. 10.1126/science.1106753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hurdle JG, O'Neill AJ, Chopra I, Lee RE. 2011. Targeting bacterial membrane function: an underexploited mechanism for treating persistent infections. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9:62–75. 10.1038/nrmicro2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yano T, Kassovska-Bratinova S, Teh JS, Winkler J, Sullivan K, Isaacs A, Schechter NM, Rubin H. 2011. Reduction of clofazimine by mycobacterial type 2 NADH:quinone oxidoreductase: a pathway for the generation of bactericidal levels of reactive oxygen species. J. Biol. Chem. 286:10276–10287. 10.1074/jbc.M110.200501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu P, Haagsma AC, Pham H, Maaskant JJ, Mol S, Lill H, Bald D. 2011. Pyrazinoic acid decreases the proton motive force, respiratory ATP synthesis activity, and cellular ATP levels. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:5354–5357. 10.1128/AAC.00507-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McLaughlin SG, Dilger JP. 1980. Transport of protons across membranes by weak acids. Physiol. Rev. 60:825–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Navon G, Ogawa S, Shulman RG, Yamane T. 1977. High-resolution 31P nuclear magnetic resonance studies of metabolism in aerobic Escherichia coli cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 74:888–891. 10.1073/pnas.74.3.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.