Abstract

Colorectal cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer death worldwide and is the third most common form of malignancy in both men and women. Several possible colon cancer chemopreventive agents are found in edible plants. Amorphophallus campanulatus (Roxb.) Blume (family: Araceae) is a tuber crop, largely cultivated throughout the plains of India for using its corm as food. This tuber has also been traditionally used for the treatment of abdominal tumors, liver diseases, piles etc. The aim of this study was to evaluate the dose-dependent cytotoxic and apoptosis inducing effects of the sub fractions of A. campanulatus tuber methanolic extract (ACME) viz. petroleum ether fraction (PEF), chloroform fraction (CHF), ethyl acetate fraction (EAF) and methanolic fraction (MEF) on the colon cancer cell line, HCT-15. Antiproliferative effects of the sub fractions of ACME were studied by MTT assay. Apoptotic activity was assessed by DAPI, Annexin V-FITC and JC-1 fluorescent staining. The chemotherapeutic drug, 5-flurouracil (5-FU) was used as positive drug control. The sub fractions of ACME significantly inhibited the proliferation of HCT-15 cells in a dose-dependent manner. In addition, the extracts were found to induce apoptosis and were confirmed by DAPI, Annexin V-FITC and JC-1 fluorescent staining. A pronounced results of cytotoxic and apoptotic activities were observed in the cells treated with 5-FU and CHF, whereas, EAF and MEF treated cells exhibited a moderate result and the least effect was observed in PEF treated cells. Our results suggested that, among the sub fractions of ACME, CHF had potent cytotoxic and apoptotic activity and thus it could be explored as a novel target for anticancer drug development. Furthermore, these findings confirm that the sub fractions of ACME dose-dependently suppress the proliferation of HCT-15 cells by inducing apoptosis.

Keywords: Amorphophallus campanulatus, Colon cancer, MTT, DAPI, JC-1, Annexin-V

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third most common malignant neoplasm worldwide and has become one of the major causes of cancer mortality (Jemal et al., 2004; American Cancer Society, 2011). Epidemiological studies have revealed a number of risk factors for colorectal cancer including age, family history of colon cancer or inflammatory bowel disease, smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity and diet (Kirkegaard et al., 2010). Human colon cancer development is often characterized at an early stage by hyperproliferation of the colonic epithelium leading to the formation of adenomas. This is mainly a consequence of dysregulated cell cycle control and/or suppressed apoptosis as usually observed in colon cancers (Gryfe et al., 1997; Potten, 1997). In addition, several studies have reported that the loss of control of apoptosis results in cancer initiation and progression and thus many new treatment strategies targeting apoptosis are feasible and may be used in the treatment of various types of cancers (Tu et al., 1996; Vitale-Cross et al., 2004; Tian et al., 2007; Wong, 2011).

Nowadays, large numbers of natural compounds have been identified that are pharmacologically highly effective against cancerous cells. It is reported that the consumption of a diet rich in phytochemicals can reduce the risk of cancer. Fruits and vegetables, which contain a diverse range of phytochemicals, are suggested to have properties important in the prevention of cancer. It includes antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative activities as well as modulatory effects on subcellular signaling pathways, induction of cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis (Block et al., 1992; Aviram et al., 2000; Kaplan et al., 2001; Afaq et al., 2005 Mahassni and Al-Reemi, 2013).

Among the various possible experimental models of cancer, human cancer cell lines have been the most widely used. They have retained the hallmarks of cancer cells namely self sufficiency in growth control, insensitivity to antigrowth signals, escape from checkpoints (apoptosis), genetic instability and invasiveness (van Staveren et al., 2009). HCT-15 cells, used in the present study, are one of the human adenocarcinoma cell lines extensively used in colon cancer studies. These cells were established from colorectal cancer after surgical resection before the chemotherapeutic treatment of a tumor (Tompkins et al., 1974).

In the present study, our aim was to investigate the cytotoxic and apoptosis inducing effects of the sub fractions of Amorphophallus campanulatus tuber methanolic extract (ACME) namely, petroleum ether fraction (PEF), chloroform fraction (CHF), ethyl acetate fraction (EAF) and methanolic fraction (MEF) on the colon cancer cell line, HCT-15. A. campanulatus (Roxb.) Blume belonging to the family of Araceae is a perennial herb commonly known as elephant foot yam. It is mostly a tuber crop of south East Asian origin and is largely cultivated throughout the plains of India for using its corm (bulb) as food (Das et al., 2009). Further, the plant is valuable as medicine particularly the corm has been used traditionally for the treatment of abdominal tumors, abdominal pain, liver diseases, piles etc. Besides, the corm has been reported to possess antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, hepatoprotective and cytotoxic activities (Khan et al., 2007; Ansil et al., 2012). The cytotoxic and apoptotic potential of the sub fractions of ACME, investigated in the present study, was compared with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) – a pyrimidine analog used in the treatment of colorectal cancer (Mohapatra et al., 2011). Furthermore, the present study was a step towards the isolation and characterization of the pharmacologically active phytochemical constituents from the crude extract of A. campanulatus tuber.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

Fetal bovine serum (FBS), N-2-Hydroxyethylpiperazine-N-2-ethane-sulfonic acid (HEPES) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) were procured from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA. 5-flourouracil (5-FU) was purchased from Biochem Pharmaceutical Industries, Mumbai, India. RPMI Medium and antibiotic–antimycotic were purchased from Gibco, Grand Island, N.Y, USA. Cell Proliferation Assay kit (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5diphenyltetrazoliumbromide, [MTT]) was purchased from HiMedia, India. 5,5′,6,6′ Tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1) was purchased from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA. Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) kit was supplied by Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was obtained from Merck, Mumbai, India. All the other chemicals used were also of high purity grade.

2.2. Cell culture

HCT-15 cell line was procured from National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune, India and grown as a monolayer in RPMI (Rosewell Park Memorial Institute) medium containing HEPES and sodium bicarbonate supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic–antimycotics. Cells were maintained in a tissue culture flask kept in a humidified incubator (5% CO2 in air at 37 °C) with a medium change every 2–3 days. When the cells reached 70–80% confluence, they were harvested with trypsin – EDTA (ethylene diamine tetra acetate) and seeded into a new tissue culture flask.

2.3. Collection and extraction of the plant material

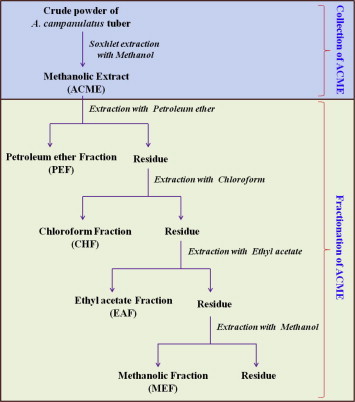

A. campanulatus tubers were harvested from the Kottayam district, Kerala, India and authenticated. A voucher specimen (SBSBRL.02) is maintained in the institute. The shade-dried tubers of A. campanulatus were powdered and subjected to Soxhlet extraction with methanol (50 g in 400 mL) and concentrated under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator. The percentage yield of methanolic extract in our study was approximately 9.3% (w/w). The methanolic extract was then taken in a round bottomed flask of simple condenser and further fractionated using solvents in increasing polarity, viz. petroleum ether, chloroform, ethyl acetate and methanol and the sub fractions were collected as petroleum ether fraction (PEF), chloroform fraction (CHF), ethyl acetate fraction (EAF) and methanolic fraction (MEF) respectively, as depicted in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the collection and fractionation of the methanolic extract of A. campanulatus tuber.

2.4. Preparation of drugs for the experiment

10 mg of PEF, CHF, EAF and MEF of ACME were dissolved in 50 μL DMSO and made up to 1 mL with phosphate buffered saline. Subsequently, the drugs were sterilized using 0.22 μm Durapore syringe filters (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) and were used as stock for further experiments. On the day of the experiment, test solutions were prepared by diluting the stock solutions in RPMI medium to give different concentrations (100 μg/mL and 50 μg/mL). 5-flourouracil, the standard control, was diluted to 50 μg/mL and 25 μg/mL with RPMI medium.

2.5. Cytotoxicity study

2.5.1. MTT assay

The cell viability was assessed by MTT assay (Mosmann, 1983), which determines the metabolically active mitochondria of intact cells. HCT-15 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany) with 5 × 103 cells/100 μL and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. The cells were then treated with PEF, CHF, EAF and MEF (100 μg/mL and 50 μg/mL), 5-FU (50 μg/mL and 25 μg/mL) and DMSO (0.1% v/v) and incubated for another 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The assay was performed by the addition of premixed MTT reagent, to a final concentration of 10% of total volume, to culture wells containing various concentrations of the test substance and incubated for a further 4 h. During the 4 h incubation, living cells converted the tetrazolium component of the dye solution into a formazan product. 100 μL of the solubilization solution was then added to the culture wells to solubilize the formazan product and the absorbance at 570 nm was recorded using a 96-well plate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The experiments were performed in triplicate. Percentage inhibition was calculated using the formula,

2.6. Detection of apoptosis

2.6.1. DAPI staining assay

4′-6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining was applied for determining the apoptotic cells. HCT-15 cells were cultured in a 24-well tissue culture grade plate (Greiner, Germany) for 24 h. After incubation with two different concentrations (100 μg/mL and 50 μg/mL) of PEF, CHF, EAF and MEF for 24 h, cells were washed in PBS, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and were treated with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. Cells after washing with PBS were stained with DAPI (1 μg/mL) and incubated in dark for 30 min. 5-flourouracil was used as the standard drug control. The cells were then examined and photographed using a fluorescence microscope (IXL 40, Labovision, India).

2.6.2. Annexin V-FITC staining

HCT-15 cells were seeded in a 12-well tissue culture grade plate (Greiner, Germany) and incubated for 24 h. After incubation, 100 μg/mL and 50 μg/mL of the sub fractions of ACME and 50 μg/mL and 25 μg/mL of 5-FU were added and further incubated for 12 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The cells were then washed with PBS and detached using trypsin – EDTA solution. Subsequently, the cells were suspended with 1× binding buffer (500 μL) containing Annexin V-FITC (1.25 μL) and incubated for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. After 15 min cells were washed with 1× binding buffer and then added with phenol red free medium and examined immediately by using a fluorescence microscope. Positive Annexin V-FITC staining will appear as bright apple green on the cell membrane surface.

2.6.3. JC-1 staining

The mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) was assayed using JC-1 (the cationic dye – 5,5′,6,6′ tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide) mitochondrial potential sensor (Invitrogen, USA), according to the manufacturer’s directions. Briefly, HCT-15 cells were incubated for 24 h in 24-well plates (Greiner, Germany) and the cells were treated with 100 μg/mL and 50 μg/mL of the sub fractions of ACME (PEF, CHF, EAF and MEF) and 50 μg/mL and 25 μg/mL of 5-FU for 18 h. The treated cells were washed with PBS and incubated for 30 min in 10% RPMI medium without phenol red containing JC-1 at a concentration of 2.5 μg/mL. The cells were then examined and photographed using a fluorescence microscope.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). All statistical comparisons were made by means of a one way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis and p-values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Cytotoxicity study

3.1.1. MTT assay

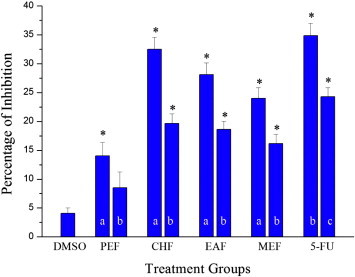

Results of the cytotoxic evaluation of the sub fractions of ACME on HCT-15 cells are graphically shown in Fig. 2. The cells were treated with 100 and 50 μg/mL of the sub fractions of ACME and the inhibition of cell proliferation was assessed after 24 h. PEF, CHF, EAF and MEF exerted cytotoxic effects on HCT-15 cells with percentage of cell inhibition values 14.0%, 32.5%, 28.1%, and 24.0% for 100 μg/mL and 8.5%, 19.6%, 18.6% and 16.2% for 50 μg/mL respectively. 5-flourouracil, used as positive control, showed an inhibition of 34.8% and 24.3% when incubated with 50 μg/mL and 25 μg/mL respectively. These values of percentage inhibition of cell proliferation demonstrate the cytotoxic activity of the treated groups in the following order: 5-FU > CHF > EAF > MEF > PEF. All the treatment groups, except 50 μg/mL of PEF, exhibited significant cytotoxic effects on HCT-15 cells (p ⩽ 0.05) when compared to the cells treated alone with DMSO.

Figure 2.

Effect of petroleum ether fraction (PEF), chloroform fraction (CHF), ethyl acetate fraction (EAF) and methanolic fraction (MEF) of ACME and 5-fluorouracil on the growth of HCT-15 cells determined by MTT assay, (a) 100 μg/mL; (b) 50 μg/mL; (c) 25 μg/mL. Cells were treated with the sub fractions of ACME (100 and 50 μg/mL) and 5-fluorouracil (50 and 25 μg/mL) for 24 h and the percentage inhibition of cell proliferation was determined. (n = 3). ∗p ⩽ 0.05 versus DMSO control.

3.2. Apoptosis assays

3.2.1. DAPI staining

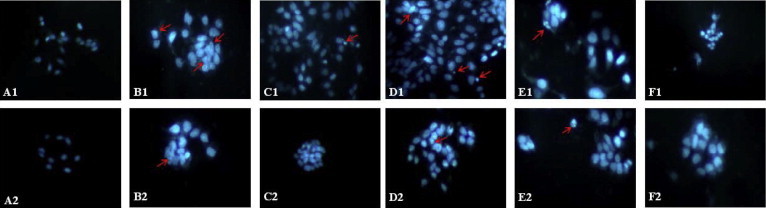

The results of DAPI staining indicated that the number of apoptotic cells were higher in drug treated cells than untreated and DMSO controls. The changes that occurred in cells as a result of PEF, CHF, EAF, MEF and 5-FU treatment are shown in Fig. 3. After DAPI staining, HCT-15 cells treated with the drugs showed marked nuclear fragmentation and chromatin condensation which are clear indications of apoptosis. A pronounced result of apoptotic body formation and nuclear fragmentation was observed in the cells treated with 5-FU and CHF, whereas, EAF and MEF treated cells exhibited a moderate result and the least effect was observed in PEF treated cells.

Figure 3.

Fluorescence image of HCT-15 cells treated with DAPI after 24 h incubation with the sub fractions of A. campanulatus tuber methanolic extract and 5-fluorouracil. Nuclear fragmentation and chromatin condensation are indicated with red arrows. (A1) Untreated cells; (A2) Cells treated with DMSO; (B1) 5-FU (50 μg/mL); (B2) 5-FU (25 μg/mL); (C1) PEF (100 μg/mL); (C2) PEF (50 μg/mL); (D1) CHF (100 μg/mL); (D2) CHF (50 μg/mL); (E1) EAF (100 μg/mL); (E2) EAF (50 μg/mL); (F1) MEF (100 μg/mL); (F2) MEF (50 μg/mL). Original magnification 200×.

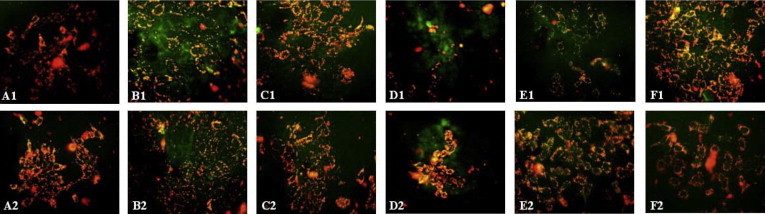

3.2.2. Annexin V-FITC staining

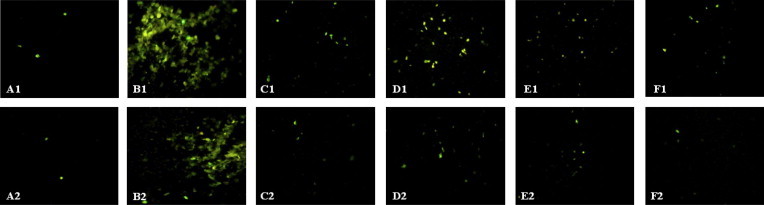

Staining with Annexin V-FITC is an apparent marker of apoptosis. Both untreated and DMSO alone treated groups of cells displayed a very faint signal, when HCT-15 cells were stained with Annexin V-FITC. Treatment with the sub fractions of ACME and 5-FU showed a dose dependent increase in the number of cells that have taken up the stain as shown in Fig. 4. Twelve hours of treatment with the standard drug control (5-FU) resulted in the intensive staining of HCT-15 cells. Likewise, the intensity of Annexin V-FITC staining was prominent in CHF treated cells indicating that it is a potential source of apoptotic inducer in human colon cancer cell line. Whereas, the bright apple green fluorescence displayed by the EAF and MEF treated cells were modest in its intensity. It was also evident from the assay that, among the sub fractions of ACME, PEF possesses the least apoptotic activity.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence image of HCT-15 cells treated with Annexin V after 12 h incubation with the sub fractions of A. campanulatus tuber methanolic extract and 5-fluorouracil. Bright apple green fluorescence shows the Annexin V-FITC staining on the cell membrane surface, a marker of early-stage apoptosis. (A1) Untreated cells; (A2) Cells treated with DMSO; (B1) 5-FU (50 μg/mL); (B2) 5-FU (25 μg/mL); (C1) PEF (100 μg/mL); (C2) PEF (50 μg/mL); (D1) CHF (100 μg/mL); (D2) CHF (50 μg/mL); (E1) EAF (100 μg/mL); (E2) EAF (50 μg/mL); (F1) MEF (100 μg/mL); (F2) MEF (50 μg/mL). Original magnification 200×.

3.2.3. JC-1 staining

Loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) is as an early event in apoptosis. When the cells are stained with JC-1, the loss of ΔΨm is indicated by the decrease of red fluorescence and the increase of green fluorescence. Eighteen hour treatment of HCT-15 cells with 100 μg/mL of CHF followed by the JC-1 staining resulted in green fluorescence in majority of cells. Cells treated with 50 μg/mL of CHF and 100 μg/mL of EAF also displayed a strong green fluorescence, indicating its potent apoptotic activity. 5-fluorouracil, the positive control, showed green fluorescence in majority of cells in a dose dependent manner. MEF and PEF treated cells exhibited both red orange and green fluorescence whereas the untreated cells and vehicle treated control cells showed orange red fluorescence only (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Fluorescence image of HCT-15 cells treated with JC-1 after 18 h incubation with the sub fractions of A. campanulatus tuber methanolic extract and 5-fluorouracil. The green fluorescence indicates a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential, an early event in apoptosis. (A1) Untreated cells; (A2) Cells treated with DMSO; (B1) 5-FU (50 μg/mL); (B2) 5-FU (25 μg/mL); (C1) PEF (100 μg/mL); (C2) PEF (50 μg/mL); (D1) CHF (100 μg/mL); (D2) CHF (50 μg/mL); (E1) EAF (100 μg/mL); (E2) EAF (50 μg/mL); (F1) MEF (100 μg/mL); (F2) MEF (50 μg/mL). Original magnification 200×.

4. Discussion

Apoptosis is an ordered and orchestrated cellular process that occurs in physiological and pathological conditions. In cancer, there is a loss of balance between cell division and cell death and cells that should have died did not receive the signals to do so. Defects along apoptotic pathways play a crucial role in carcinogenesis (Wong, 2011). Although many treatment strategies that target apoptosis are introduced, the interests in the search for natural compounds with potential apoptotic activity are still high. In the present work, we have studied the cytotoxic and apoptotic potential of the sub fractions of ACME on human colon carcinoma cell line, HCT-15.

MTT assay is an established method of determining viable cell number in proliferation and cytotoxicity studies (Sylvester, 2011). In the present study, cytotoxic effect of the sub fractions of ACME on HCT-15 cells were determined based on reduction of the yellow colored water soluble tetrazolium dye 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) to formazan crystals. Mitochondrial dehydrogenase produced by live cells reduces MTT to blue formazan product, which reflects the normal function of mitochondria and cell viability (Lau et al., 2004). The cytotoxic potential investigated based on the above principle indicated that, among the sub fractions of ACME, CHF possess the highest antiproliferative activity against HCT-15 cells followed by EAF, MEF and PEF.

Apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death, is characterized by cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, inter nucleosomal DNA fragmentation, and the formation of apoptotic bodies. Apoptosis and its related signaling pathways have a profound effect on the progression of cancer; therefore, the induction of apoptosis is a desirable goal for the prevention of cancer. It is reported that anticancer drugs exert their antitumor effects against cancer cells by inducing apoptosis (Salomons et al., 1999). Furthermore, it is established that apoptosis is an important mechanism by which dietary compounds exhibit their chemopreventive potential (Song et al., 2012; Ramesh and Alshatwi, 2013). DAPI staining is a reliable apoptotic assay in chemoprevention studies and it helps to observe the apoptotic changes at DNA level (Saha et al., 2013). Whereas, the apoptotic alterations of the plasma membrane and mitochondria can be perceived through Annexin V-FITC staining and JC-1 staining respectively (Szliszka et al., 2011; Nadda et al., 2013).

In the present investigation, we hypothesized that the sub fractions of ACME may exert its cytotoxic activity on HCT-15 cells by inducing apoptosis. We tested this hypothesis and found that the cytotoxic effect of the sub fractions of ACME is coupled with apoptosis. The morphological changes that occur in apoptotic cells, induced by the drugs, were perceived through DAPI staining. This demonstrated that the treatment with 5-FU, CHF and EAF mainly resulted in apoptotic body formation, chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation. It clearly indicates their apoptotic potential against colon cancer particularly on HCT-15 cells.

In healthy cells, phospholipids are asymmetrically distributed, with the anionic phospholipid phosphatidylserine normally confined to the cytoplasmic face of the plasma membrane (Balasubramanian and Schroit, 2003). It has been reported that loss of membrane asymmetry is an early and critical event of apoptosis due to which phosphatidylserine residues become exposed at the outer plasma membrane. This loss of membrane asymmetry and thereby apoptosis can be detected by utilizing the strong and specific interaction of Annexin V with phosphatidylserine (van Engeland et al., 1998). Phosphatidylserine translocation to the cell surface precedes nuclear breakdown, DNA fragmentation, and the appearance of most apoptosis-associated molecules making Annexin V binding a marker of early stage apoptosis. In the present study, to characterize the cellular death process caused by the sub fractions of ACME and 5-FU, HCT-15 cells were treated with the drugs and binding of Annexin V-FITC was detected by fluorescence microscopy. The intensive bright apple green staining on the cell membrane surface resulted after the treatment with CHF and EAF confirms that these two sub fractions of ACME possess highest apoptotic potential than PEF and MEF. Annexin V-FITC staining also indicates that the apoptosis induced by the sub fractions of ACME and 5-FU on HCT-15 cells are apparently due to the loss of plasma membrane asymmetry.

Mitochondria represent key organelles for the cell survival, and their role in programmed cell death is known since several years (Lugli et al., 2005). JC-1 is a reliable probe for the analysis of mitochondrial transmembrane potential changes occurring very early in apoptosis. It is a mitochondrial lipophilic dye and becomes concentrated in mitochondria in proportion to their membrane potential (ΔΨm); more dye becomes accumulated in mitochondria with greater ΔΨm and ATP generating capacity. Therefore, fluorescence of JC-1 can be considered as an indicator of mitochondrial energy state and the dye exists as a monomer at low concentrations giving green fluorescence. At higher concentrations it forms J-aggregates giving red fluorescence. J-aggregates are multimers of JC-1 formed inside intact mitochondria and their formation and fluorescence responds linearly to increase in mitochondrial membrane potential. Therefore, in JC-1 staining, the apoptotic cells were identified by an increase in green fluorescence and the loss of red fluorescence (Smiley et al., 1991; Salvioli et al., 1997; Savitskiy et al., 2003). The results of JC-1 staining, observed in the present study, obviously indicate that the sub fractions of ACME are capable to decrease the mitochondrial ΔΨm and thereby can induce apoptosis in HCT-15 cells. Among the sub fractions of ACME, the green fluorescence was prominent in cells treated with CHF and EAF. The increase of green fluorescence and the loss of red fluorescence in HCT-15 cells treated with 5-FU, CHF and EAF also demonstrated that the drugs exert their apoptotic potential in a dose dependent manner.

Many studies revealed the anticancer properties of plant based foods in cell culture and animal models. The phytochemical constituents present in the plant based foods are mainly responsible for their apoptotic activity (Surh, 2003). A. campanulatus tuber, evaluated for the apoptotic activity in the present study, is mainly consumed as food in many parts of the world. It is reported that ACME possess phytochemical constituents such as alkaloids, tannins, glycosides, phenols, flavonoids, saponins and carbohydrates (Ansil et al., 2011). Published report also establishes the presence of betulinic acid, lupeol, stigmasterol, β-sitosterol, glucose, galactose, rhamnose and xylose in the corm of A. campanulatus (Khare, 2007). Thus, in the present study, the cytotoxic and apoptotic activity exhibited by the extracts of A. campanulatus tuber might be attributed to the presence of the identified class of chemicals in single or in combination.

5. Conclusion

The present study demonstrates that the sub fractions of ACME possess antiproliferative and apoptotic activity against human colon carcinoma cell line, HCT-15. Among the sub fractions of ACME, CHF significantly inhibited the proliferation of HCT-15 cells in a concentration dependent manner. Whereas, EAF and MEF treated cells exhibited a moderate result and the least effect was observed in PEF treated cells. The inhibitory effect of natural bioactive substances in carcinogenesis and tumor growth may be through two main mechanisms: modifying redox status and interference with basic cellular functions (cell cycle, apoptosis, inflammation, angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis) (Kampa et al., 2007). In addition, apoptosis has been reported to play an important role in the elimination of seriously damaged cells or tumor cells by chemopreventive or chemotherapeutic agents (Galati et al., 2000). Therefore, apoptosis-inducing natural products including the most promising CHF identified in the present investigation can be explored as novel targets for anticancer drug development. However, further studies are needed to comprehend the different mechanisms by which the sub fractions of the methanolic extract of A. campanulatus tuber exert their cytotoxic and apoptotic effects on the colon cancer cell line, HCT-15.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by the University Grants Commission (UGC), New Delhi, India. Financial assistance from the UGC as Research Fellowship in Sciences for Meritorious Students to the first author is also thankfully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Afaq F., Saleem M., Krueger C.G., Reed J.D., Mukhtar H. Anthocyanin- and hydrolyzable tannin-rich pomegranate fruit extract modulates MAPK and NF-kappaB pathways and inhibits skin tumorigenesis in CD-1 mice. Int. J. Cancer. 2005;113:423–433. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society, 2011. Colorectal cancer facts & Figures 2011–2013, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Available at: http://www.cancer.org. Accessed on 24 December, 2011.

- Ansil P.N., Nitha A., Prabha S.P., Wills P.J., Jazaira V., Latha M.S. Protective effect of Amorphophallus campanulatus (Roxb.) Blume tuber against thioacetamide induced oxidative stress in rats. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2011;4:870–877. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansil P.N., Prabha S.P., Nitha A., Wills P.J., Jazaira V., Latha M.S. Curative effect of Amorphophallus campanulatus (Roxb.) Blume tuber methanolic extract against thioacetamide induced oxidative stress in experimental rats. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012;2:S83–S89. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviram M., Dornfeld L., Rosenblat M., Volkova N., Kaplan M., Coleman R., Hayek T., Presser D., Fuhrman B. Pomegranate juice consumption reduces oxidative stress, atherogenic modifications to LDL, and platelet aggregation: studies in humans and in atherosclerotic apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000;71:1062–1076. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian K., Schroit A.J. Aminophospholipid asymmetry: a matter of life and death. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003;65:701–734. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block G., Patterson B., Subar A. Fruit, vegetables, and cancer prevention: a review of the epidemiological evidence. Nutr. Cancer. 1992;18:1–29. doi: 10.1080/01635589209514201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das D., Mondal S., Roy S.K., Maiti D., Bhunia B., Maiti T.K., Islam S.S. Isolation and characterization of a heteropolysaccharide from the corm of Amorphophallus campanulatus. Carbohydr. Res. 2009;344:2581–2585. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galati G., Teng S., Moridani M.Y., Chan T.S., O’Brien P.J. Cancer chemoprevention and apoptosis mechanisms induced by dietary polyphenolics. Drug. Metabol. Drug. Interact. 2000;17:311–349. doi: 10.1515/dmdi.2000.17.1-4.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryfe R., Swallow C., Bapat B., Redston M., Gallinger S., Couture J. Molecular biology of colorectal cancer. Curr. Probl. Cancer. 1997;21:233–300. doi: 10.1016/s0147-0272(97)80003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A., Tiwari R.C., Murray T., Ghafoor A., Samuels A., Ward E., Feuer E.J., Thun M.J. American Cancer Society. Cancer statistics, 2004. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2004;54:8–29. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampa M., Nifli A.P., Notas G., Castanas E. Polyphenols and cancer cell growth. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007;159:79–113. doi: 10.1007/112_2006_0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan M., Hayek T., Raz A., Coleman R., Dornfeld L., Vaya J., Aviram M. Pomegranate juice supplementation to atherosclerotic mice reduces macrophage lipid peroxidation, cellular cholesterol accumulation and development of atherosclerosis. J. Nutr. 2001;131:2082–2089. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.8.2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A., Rahman M., Islam S. Antibacterial, antifungal and cytotoxic activities of tuberous roots of Amorphophallus campanulatus. Turk. J. Biol. 2007;31:157–172. [Google Scholar]

- Khare C.P. Springer; New York: 2007. Indian Medicinal Plants. An Illustrated Dictionary. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkegaard H., Johnsen N.F., Christensen J., Frederiksen K., Overvad K., Tjønneland A. Association of adherence to lifestyle recommendations and risk of colorectal cancer: a prospective Danish cohort study. BMJ. 2010;341:c5504. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau C.B., Ho C.Y., Kim C.F., Leung K.N., Fung K.P., Tse T.F., Chan H.H., Chow M.S. Cytotoxic activities of Coriolus versicolor (Yunzhi) extract on human leukemia and lymphoma cells by induction of apoptosis. Life Sci. 2004;75:797–808. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugli E., Troiano L., Ferraresi R., Roat E., Prada N., Nasi M., Pinti M., Cooper E.L., Cossarizza A. Characterization of cells with different mitochondrial membrane potential during apoptosis. Cytometry A. 2005;68:28–35. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahassni S.H., Al-Reemi R.M. Apoptosis and necrosis of human breast cancer cells by an aqueous extract of garden cress (Lepidium sativum) seeds. Saudi. J. Biol. Sci. 2013;20:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohapatra P., Preet R., Choudhuri M., Choudhuri T., Kundu C.N. 5-fluorouracil increases the chemopreventive potentials of resveratrol through DNA damage and MAPK signaling pathway in human colorectal cancer cells. Oncol. Res. 2011;19:311–321. doi: 10.3727/096504011x13079697132844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadda N., Setia S., Vaish V., Sanyal S.N. Role of cytokines in experimentally induced lung cancer and chemoprevention by COX-2 selective inhibitor, etoricoxib. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2013;372:101–112. doi: 10.1007/s11010-012-1451-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potten C.S. Epithelial cell growth and differentiation II. Intestinal apoptosis. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:G253–G257. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.2.G253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh E., Alshatwi A.A. Naringin induces death receptor and mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in human cervical cancer (SiHa) cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013;51:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S.K., Sikdar S., Mukherjee A., Bhadra K., Boujedaini N., Khuda-Bukhsh A.R. Ethanolic extract of the Goldenseal, Hydrastis canadensis, has demonstrable chemopreventive effects on HeLa cells in vitro: Drug-DNA interaction with calf thymus DNA as target. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2013;36:202–214. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2013.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomons G.S., Smets L.A., Verwijs-Janssen M., Hart A.A., Haarman E.G., Kaspers G.J. Bcl-2 family members in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: relationships with features at presentation, in vitro and in vivo drug response and long-term clinical outcome. Leukemia. 1999;13:1574–1580. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvioli S., Ardizzoni A., Franceschi C., Cossarizza A. JC-1, but not DiOC6(3) or rhodamine 123, is a reliable fluorescent probe to assess delta psi changes in intact cells: implications for studies on mitochondrial functionality during apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 1997;411:77–82. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00669-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitskiy V.P., Shman T.V., Potapnev M.P. Comparative measurement of spontaneous apoptosis in pediatric acute leukemia by different techniques. Cytometry B Clin. Cytom. 2003;56:16–22. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.10056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smiley S.T., Reers M., Mottola-Hartshorn C., Lin M., Chen A., Smith T.W., Steele G.D., Jr., Chen L.B. Intracellular heterogeneity in mitochondrial membrane potentials revealed by a J-aggregate-forming lipophilic cation JC-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:3671–3675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W., Shen D.Y., Kang J.H., Li S.S., Zhan H.W., Shi Y., Xiong Y.X., Liang G., Chen Q.X. Apoptosis of human cholangiocarcinoma cells induced by ESC-3 from Crocodylus siamensis bile. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012;18:704–711. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i7.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surh Y.J. Cancer chemoprevention with dietary phytochemicals. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:768–780. doi: 10.1038/nrc1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester P.W. Optimization of the tetrazolium dye (MTT) colorimetric assay for cellular growth and viability. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011;716:157–168. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-012-6_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szliszka E., Zydowicz G., Janoszka B., Dobosz C., Kowalczyk-Ziomek G., Krol W. Ethanolic extract of Brazilian green propolis sensitizes prostate cancer cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Int. J. Oncol. 2011;38:941–953. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Z., Pan R., Chang Q., Si J., Xiao P., Wu E. Cimicifuga foetida extract inhibits proliferation of hepatocellular cells via induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;114:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins W.A., Watrach A.M., Schmale J.D., Schultz R.M., Harris J.A. Cultural and antigenic properties of newly established cell strains derived from adenocarcinomas of the human colon and rectum. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1974;52:1101–1110. doi: 10.1093/jnci/52.4.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu H., Jacobs S.C., Borkowski A., Kyprianou N. Incidence of apoptosis and cell proliferation in prostate cancer: relationship with TGF-beta1 and bcl-2 expression. Int. J. Cancer. 1996;69:357–363. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961021)69:5<357::AID-IJC1>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Engeland M., Nieland L.J., Ramaekers F.C., Schutte B., Reutelingsperger C.P. Annexin V-affinity assay: a review on an apoptosis detection system based on phosphatidylserine exposure. Cytometry. 1998;31:1–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19980101)31:1<1::aid-cyto1>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Staveren W.C., Solís D.Y., Hébrant A., Detours V., Dumont J.E., Maenhaut C. Human cancer cell lines: Experimental models for cancer cells in situ? For cancer stem cells? Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1795:92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale-Cross L., Amornphimoltham P., Fisher G., Molinolo A.A., Gutkind J.S. Conditional expression of K-ras in an epithelial compartment that includes the stem cells is sufficient to promote squamous cell carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8804–8807. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong R.S. Apoptosis in cancer: from pathogenesis to treatment. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;30:87. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-30-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]