Abstract

Background

A diagnosis of depression is common in primary care practices, but data are lacking on the prevalence in Canadian practices. We describe the prevalence of the diagnosis among men and women, patient characteristics and drug treatment in patients diagnosed with depression in the primary care setting in Canada.

Methods

Using electronic medical record data from the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network, we examined whether the prevalence of a depression diagnosis varied by patient characteristics, the number of chronic conditions and the presence of the following chronic conditions: hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, osteoarthritis, dementia, epilepsy and parkinsonism. We used regression models to examine whether patient characteristics and type of comorbidity were associated with a depression diagnosis.

Results

Of the 304 412 patients who had at least 1 encounter with their primary care provider between Jan. 1, 2011, and Dec. 31, 2012, 14% had a diagnosis of depression. Current or past smokers and women with a high body mass index had higher rates of depression. One in 4 patients with a diagnosis of depression also had another chronic condition; those with depression had 1.5 times more primary care visits. About 85% of patients with depression were prescribed medication, most frequently selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, followed by atypical antipsychotics.

Interpretation

Our data provide information on the prevalence of a depression diagnosis in primary care and associations with being female, having a chronic condition, smoking history and obesity in women. Our findings may inform research and assist primary care providers with early detection and interventions in at-risk patient populations.

About 20 years ago, Anderson and colleagues1 pointed out that individual-level psychological distress, such as depression, in a population correlates highly with the mean population level of psychological distress.1 Depression has been found to significantly worsen individuals’ overall health status.2 Previous studies report that the prevalence of depression was significantly higher in patients with heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, rheumatoid arthritis and osteoporosis than in the general population.3,4 It is likely that shared underlying biological mechanisms (e.g., inflammatory processes) are etiological factors in both depression and other chronic conditions.5,6 The societal burden of depression includes an estimated cost of US$14 billion in health care expenditures and productivity losses.7

The World Health Organization reports that unipolar depressive disorder is more common than traffic accidents, cerebrovascular disease and ischemic heart disease and therefore responsible for a greater decrease in disability-adjusted life years in middle- and high-income countries.7 Depression is so prevalent that it is considered a serious public health issue.2 The 12-month prevalence rate of the most common form of depression, major depressive disorder, ranges from 5% to 14%.2 A large collaborative study by the World Health Organization, which included 26 000 patients in 15 centres worldwide, found a point prevalence rate of 10.4% for depression as defined by the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision.8 It is estimated that, over the course of a single year, 1 360 000 Canadians meet the criteria for major depressive disorder alone, as defined by the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.2 However, data from a large study are lacking on the prevalence of major depressive disorder or any form of depression in primary care in Canada.

Depression is most commonly diagnosed and treated in primary care.2 To determine the prevalence of depression among patients living in Canada, we used data from primary care electronic medical records collected for the purpose of surveillance of chronic conditions. The Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network is the first pan-Canadian, multidisease population health surveillance system. The purpose of this study was to describe the prevalence of a diagnosis of depression among men and women, patient characteristics, and the treatment (i.e., type and number of prescriptions) provided to these patients in a primary care setting in Canada.

Methods

Data source

The Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network consists of 10 practice-based research networks across Canada. The network contains data from almost 500 sentinel primary care providers (family physicians and nurse practitioners) and more than 600 000 patients.9 Although these providers are more likely to be younger and female than a general sample of primary care providers, patients included in this study are representative of those who visit primary care in Canada.10 Each consenting provider contributes de-identified patient data from the electronic medical records on a quarterly basis. Patients of consenting providers can decline to participate in the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network (< 0.01% decline to participate) and their patient records are then excluded from this pan-Canadian clinical data repository. All practice-based research networks have received research ethics board approval from their institution as well as ethics approval from Health Canada for collecting this information. To optimize the quality, comparability and usefulness of data for research, each network’s data manager transforms the extracted data into a common database template. Various checks for completeness and validity are performed, and several algorithms are performed for identifying cases of chronic disease and for coding textual data into discrete categories. Once data processing is complete, each practice-based research network database is securely submitted to a central repository, where a national Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network database is constructed, checked and prepared for quarterly analysis and reporting.

Case definition for depression

The Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network developed and validated a case definition for the diagnosis of depression: episodic mood disorders, depressive disorder not elsewhere classified, bipolar, manic affective disorder, manic episodes, mild depression (not simply clinical depression).10 This definition uses a combination of codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9), and free-text searches within the problem list, billing and encounter diagnoses and the medication history.10 Previous work on case validation, using a review of randomly sampled charts, has shown that the network’s diagnostic algorithm for depression performed adequately, with a sensitivity of 81.1% (95% confidence interval [CI] 77.2%–85.0%), a specificity of 94.8% (95% CI 93.7%–95.9%), a positive predictive value of 79.6% (95% CI 75.7%–83.6%) and a negative predictive value of 95.2% (95% CI 94.1%–96.3%).10 This definition was used to identify any instance of a diagnosis throughout the patient’s entire electronic medical record.

Inclusion criteria

All patients who visited their primary care provider between Jan. 1, 2011, and Dec. 31, 2012, were included in this study. We used a 2-year prevalence time frame because this is an accepted estimate of panel size in the primary care setting.11 A 12-month period will underestimate the panel size because many patients do not visit their primary care provider within a 1-year time frame.12

Variables of interest

We examined whether the prevalence of a diagnosis of depression varied by patient characteristics, including age, sex, rural or urban residence, smoking status and body mass index (BMI). We also examined whether those with a diagnosis of depression had any of the other chronic conditions for which the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network has a validated case definition (i.e., hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, osteoarthritis, dementia, epilepsy and parkinsonism) as well as the number of chronic conditions. Finally, we examined the type and number of medications prescribed for those with a diagnosis of depression (Table 1).

Table 1: List of medications commonly used to treat depression, by classification.

| Classification | Medication (generic name) |

|---|---|

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

Citalopram Escitalopram Fluoxetine Fluvoxamine Paroxetine Sertraline |

| Tricyclics and tetracyclics |

Amitriptyline Amoxapine Butriptyline Clomipramine Desipramine Doxepin Imipramine Maprotiline Nortriptyline Protriptyline Trimipramine |

| Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors |

Desvenlafaxine Duloxetine Venlafaxine |

| Serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors |

Trazodone |

| Atypical antipsychotics |

Aripiprazole Bupropion Mirtazapine Quetiapine |

| Monoamine oxidase inhibitors |

Isocarboxazid Moclobemide Phenelzine Selegiline Tranylcypromine |

| Bipolar medications | Lithium Carbamazepine Divalproex Lamotrigine Valproate |

Patient characteristics

We determined patients’ residence in rural or urban areas using the first 3 digits of the practice’s postal code, also known as the forward sortation area. Following Canada Post’s procedure for classification, we coded residence as rural if there was a value of zero in the second digit of their forward sortation areas and urban for those with all other values.13 Smoking status was recorded in 3 categories: 1) patients who had never smoked were coded as “nonsmokers”; 2) patients who smoked, regardless of frequency and amount, were coded as “smokers”; and 3) patients who reported having quit smoking were coded as “past smokers.” Body mass index was calculated based on the most recent height and weight data available. The BMI values were classified as follows: underweight (< 18), normal (18–24), overweight (25–29) and obese (≥ 30). The last available record on these patient characteristics was included in the analyses.

Medication

We developed a list of commonly used medications when a diagnosis of depression is made (Table 1) to identify patients who have been prescribed medications used to treat depression. The medications were categorized as follows: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclics and tetracyclics, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors, atypical antipsychotics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors and bipolar medications. The generic names of the prescribed medication were extracted from the electronic medical record.

Analysis

Data were analyzed by sex and as a total sample. We examined the lifetime prevalence of a diagnosis of depression among those who had visited their primary care provider in the last 2 years. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the mean number of comorbidities, and type and number of medications prescribed. We used a series of age-adjusted log-binominal regression models to examine whether patient characteristics and type of comorbidity were significantly associated with a diagnosis of depression. The log-binominal approach is akin to a logistic regression approach but is more appropriate to use when trying to estimate the prevalence ratio, or relative risk.14 All analyses were done using SAS 9.3.

Results

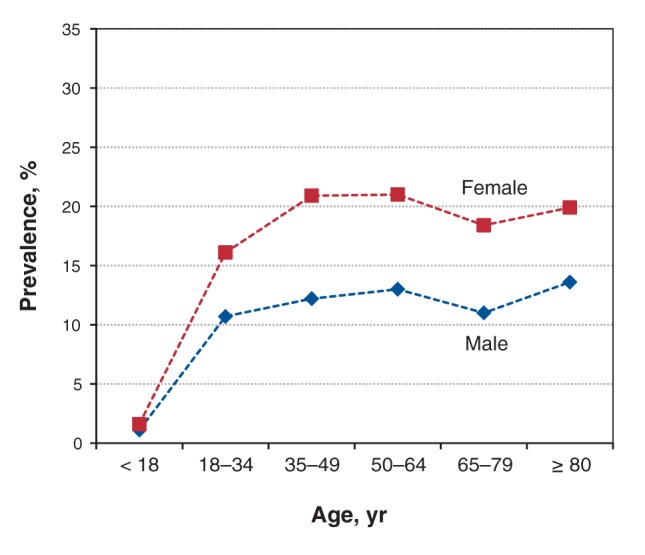

As of Dec. 31, 2012, the database of the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network contained data for a total of 304 412 patients who had at least 1 encounter with their primary care provider between Jan. 1, 2011, and Dec. 31, 2012. Of these, 41 274 (14%) had a diagnosis of depression. Figure 1 shows that, in all age categories, a diagnosis of depression was more prevalent among women than men. Almost 17% (n = 28 526) of women who had seen their primary care provider during these 2 years had a diagnosis of depression, compared with 10% (n = 12 748) of men.

Figure 1:

Lifetime prevalence of a diagnosis of depression by age and sex. Total prevalence: observed = 13.6%, age–sex standardized = 13.1%. Data source: Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network 2012.

After adjustment for age, our regression models suggest that residence in a rural area was associated with a lower likelihood of diagnosis of depression for both sexes (Table 2). Both men and women who were current or past smokers had a significantly higher risk of having a diagnosis of depression. Women who were overweight or obese had a higher rate of diagnosis of depression than women with a normal BMI.

Table 2: Age-adjusted prevalence ratios for a diagnosis of depression in men and women, by characteristic.

| Characteristic | Prevalence ratio (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men n = 12 748 |

Women n = 28 526 |

|||

|

Residence* |

||||

| Urban |

1.00 (reference) |

1.00 (reference) |

||

| Rural |

0.90 |

(0.87–0.94) |

0.92 |

(0.90–0.95) |

|

BMI† |

||||

| Normal (18–24) |

1.00 (reference) |

1.00 (reference) |

||

| Underweight (< 18) |

0.91 |

(0.83–1.00) |

0.96 |

(0.91–1.03) |

| Overweight (25–29) |

0.95 |

(0.90–1.00) |

1.06 |

(1.03–1.10) |

| Obese (≥ 30) |

1.03 |

(0.98–1.08) |

1.17 |

(1.13–1.20) |

|

Smoking‡ |

||||

| Never |

1.00 (reference) |

1.00 (reference) |

||

| Current |

1.54 |

(1.46–1.64) |

1.60 |

(1.54–1.66) |

| Past | 1.17 | (1.10–1.24) | 1.32 | (1.27–1.38) |

Note: BMI = body mass index, CI = confidence interval. *Data on residence missing for 10 650 patients (4977 men, 5673 women). †Data on BMI missing for 117 374 patients (53 917 men, 63 457 women). ‡Data on smoking status missing for 201 139 patients (89 686 men, 111 453 women).

More than half of those with a diagnosis of depression had no other comorbidities recorded (Table 3). Yet, 1 out of 4 people with a diagnosis of depression also had 1 other chronic condition for which the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network has a validated case definition. Table 4 shows that for those with a chronic condition, the prevalence of depression was significantly higher. The prevalence of depression was highest in those diagnosed with dementia, followed by parkinsonism and epilepsy.

Table 3: Presence of a diagnosis of depression by number of other chronic conditions.

| No. (%) of patients |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of other conditions | Men |

Women |

Total |

|||||||||

| No depression n = 118 424 |

Depression n = 12 748 |

No depression n = 144 714 |

Depression n = 28 526 |

No depression n = 263 138 |

Depression n = 41 274 |

|||||||

| 0 |

84 009 |

(70.9) |

6 932 |

(54.4) |

105 812 |

(73.1) |

16 695 |

(58.5) |

189 821 |

(72.1) |

23 627 |

(57.2) |

| 1 |

22 983 |

(19.4) |

3 351 |

(26.3) |

25 344 |

(17.5) |

6 937 |

(24.3) |

48 327 |

(18.4) |

10 288 |

(24.9) |

| 2 |

9 018 |

(7.6) |

1 740 |

(13.7) |

10 577 |

(7.3) |

3 395 |

(11.9) |

19 595 |

(7.5) |

5 135 |

(12.4) |

| ≥ 3 | 2 415 | (2.1) | 725 | (5.6) | 2 981 | (2.1) | 1 499 | (5.3) | 5 395 | (2.0) | 2 224 | (5.5) |

Table 4: Age-adjusted prevalence ratios for a diagnosis of depression in men and women, by comorbidity.

| Comorbidity | Prevalence ratio (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men n =12 748 |

Women n = 28 526 |

|||

| Hypertension |

1.15 |

(1.12–1.18) |

1.14 |

(1.12–1.16) |

| Diabetes |

1.23 |

(1.18–1.29) |

1.36 |

(1.31–1.42) |

| COPD |

1.78 |

(1.67–1.90) |

1.82 |

(1.72–1.92) |

| Osteoarthritis |

1.37 |

(1.31–1.43) |

1.35 |

(1.32–1.39) |

| Dementia |

3.23 |

(2.96–3.52) |

2.47 |

(2.32–2.63) |

| Epilepsy |

2.03 |

(1.77–2.33) |

1.82 |

(1.63–2.04) |

| Parkinsonism | 2.27 | (1.86–2.77) | 2.22 | (1.83–2.70) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The mean number of encounters with the primary care provider during a 12-month period was higher among those with a diagnosis of depression (Table 5). This pattern remained with both sexes and over a longer period (24 mo). Notably, even after controlling for age, sex, rural or urban residence, and all other chronic conditions (hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, osteoarthritis, dementia, epilepsy, parkinsonism), those with a diagnosis of depression had 1.5 (95% CI 1.5–1.6) times more visits to their primary care provider than those without the diagnosis (data not shown).

Table 5: Number of encounters with a primary care provider in patients with and without a diagnosis of depression.

| Period | No depression |

Depression |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men n = 118 424 |

Women n = 144 714 |

Total n = 144 714 |

Men n = 12 748 |

Women n = 28 526 |

Total n = 41 274 |

|

| 12 months |

||||||

| Mean (± SD) |

3.7 (± 3.8) |

4.1 (± 4.0) |

3.9 (± 3.9) |

5.6 (± 5.2) |

6.3 (± 5.5) |

6.1 (± 5.4) |

| Median |

3.0 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

4.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

| 24 months |

||||||

| Mean (± SD) |

5.9 (± 6.4) |

7.0 (± 7.0) |

6.5 (± 6.8) |

10.1 (± 9.3) |

11.5 (± 9.7) |

11.1 (± 9.6) |

| Median | 4.0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 |

SD = standard deviation.

About 85% of patients with a diagnosis of depression were prescribed some form of medication for this condition. Almost half (48%) were prescribed 1 antidepressant medication, whereas about 23% were prescribed 2 medications (Table 6). More than one-third of patients (34% of men and 38% of women) were simultaneously prescribed more than 2 antidepressant medications. Table 7 shows that the most frequently prescribed medications were selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (65% of men and 69% of women), followed by atypical antipsychotics (24% of men and 22.3% of women) and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (19% of men and 22% of women).

Table 6: Number of medications used in treating depression taken by patients with a diagnosis of depression.

| No. of medications | No. (%) of patients |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men n = 12 748 |

Women n = 28 526 |

Total n = 41 274 |

||||

| 0 |

2 222 |

(17.4) |

(4 083 |

(14.3) |

6 305 |

(15.3) |

| 1 |

6 155 |

(48.3) |

13 691 |

(48.0) |

19 846 |

(48.1) |

| 2 |

2 889 |

(22.7) |

6 746 |

(23.7) |

9 635 |

(23.3) |

| ≥ 3 | 1 482 | (11.6) | 4 006 | (14.0) | 5 488 | (13.3) |

Table 7: Medications prescribed to patients with a diagnosis of depression.

| Classification | No. (%) of patients |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men n = 12 748 |

Women n = 28 526 |

Total n = 41 274 |

||||

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

8 291 |

(65.0) |

19 756 |

(69.3) |

28 047 |

(68.0) |

| Atypical antipsychotics |

3 067 |

(24.1) |

6 350 |

(22.3) |

9 417 |

(22.8) |

| Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors |

2 478 |

(19.4) |

6 401 |

(22.4) |

8 879 |

(21.5) |

| Tricyclics and tetracyclics |

1 384 |

(10.9) |

4 026 |

(14.1) |

5 410 |

(13.1) |

| Serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors |

1 142 |

(9.0) |

2 988 |

(10.5) |

4 130 |

(10.0) |

| Bipolar medications |

508 |

(4.0) |

976 |

(3.4) |

1 484 |

(3.6) |

| Monoamine oxidase inhibitors |

43 |

(0.3) |

71 |

(0.3) |

114 |

(0.3) |

| No depression medication | 2 222 | (17.4) | 4 083 | (14.3) | 6 305 | (15.3) |

Interpretation

In this large Canadian study, we were able to identify a number of patient characteristics associated with depression and describe the treatment of these patients. Across all age groups, women were found to have a higher prevalence of a diagnosis of depression than men. In both men and women, residence in a rural area was associated with a lower rate of depression, and patients who were considered current or past smokers had a significantly higher risk of having a diagnosis of depression. Moreover, women whose BMI indicated they were overweight or obese had a higher rate of depression than their counterparts with BMIs in the normal range. Of patients with a diagnosis of depression, 25% also had 1 or more other chronic conditions. Those with a diagnosis of depression have a higher number of visits to their primary care provider than those with no depression diagnosis.

Use of data from the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network provided a novel approach to examining lifetime prevalence of a diagnosis of depression. Historically, the assessment of lifetime prevalence is based on retrospective assessment instruments and therefore subject to recall bias. Our prospective examination of the clinical data avoids the recall bias that has been thought to influence the pattern of age-specific lifetime prevalence.15 Although past studies have reported a decline in lifetime prevalence with age,16 our data suggest there is no decline in lifetime prevalence of a diagnosis of depression. Although we found a prevalence rate (13.6% total) for a diagnosis of depression that was higher than the12-month prevalence found by Moussavi and colleagues,4 we would expect it to be higher given that we did not restrict the diagnosis to major depressive disorder. Notably, the prevalence of a diagnosis of depression for men and women in this study was similar to what has been found using the 2002 Canadian Community Health Survey Mental Health component.17 Our results are consistent with past work that showed a positive association between smoking status and having 1 or more chronic condition.18–20 For women, a BMI indicating overweight or obesity was another characteristic associated with a diagnosis of depression. A high BMI for women could increase their negative perceptions about their bodies; sociological work suggests that women’s perceived body image is related to a diagnosis of depression.21 Yet, more work is needed to examine whether adverse effects of medications, particularly from atypical antipsychotics, cause excessive weight gain in women. Primary care providers may want to screen for depression in women with a BMI indicative of obesity, or communicate to patients that a known adverse effect of atypical antipsychotics is weight gain.

Given that women tend to use primary care more than men,22 primary care providers may be more likely to recognize depressive symptoms in women than in men. The manifestation of depressive symptoms may also be different in men and less easily recognized. Indeed, men will rarely mention any emotional or behavioural difficulties to their providers and may only discuss emotional problems in terms of “stress.”23

Data from our study indicate that many more patients with a diagnosis of depression are receiving a prescription for antidepressant medication (85%) than what has been reported in the past (60%).2 This could be reflective of widespread increasing use of antidepressant medications in Canada or the fact that these patients had stronger connections to primary care and therefore better access to treatment.24 The 15% of those in our study who are reported as having a diagnosis of depression but not taking any antidepressants may represent patients using non-medical treatments, such as cognitive behavioural therapy.16

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. These data are not representative of the entire Canadian population, but rather represent practices that are more engaged in chronic disease surveillance. Our case-finding definition for depression is imperfect in that it could misclassify other conditions as a diagnosis of depression, because the ICD-9 code 296 (affective psychoses) encompasses diagnostic subcategories for depression (ICD-9 296.2, 296.3, 296.9) and bipolar disorders.25 Due to the cross-sectional nature of the data, we were not able to determine whether chronic conditions occurred before a diagnosis of depression or vice versa or infer causality. It is possible that we have not captured the true proportion of patients taking medication, because antidepressants prescribed by a psychiatrist may not get recorded in the electronic medical record. Finally, it is not possible to differentiate severity of depressive symptoms using our data.

Conclusion

Our study provides information on a large cohort of patients with a diagnosis of depression in Canada using clinical data from electronic medical records. An area for future study could be patients who are reported as having a diagnosis of depression but not taking any antidepressants. It is not clear why patients with a diagnosis of depression do not take antidepressants. More work is needed to understand if these patients are not adhering to medication, or if something else has helped them with their depression. Our findings also suggest that more could be done to screen for depression among men visiting their primary care provider and among those who have a chronic condition, have been a past or current smoker, or women with a BMI indicative of overweight or obesity.

Supplemental information

For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/2/4/E337/suppl/DC1

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network is funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada under a contribution agreement with the College of Family Physicians of Canada. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Public Health Agency of Canada. The authors retained full academic control of this work including the right to publish.

References

- 1.Anderson J, Huppert F, Geoffrey R. Normality, deviance, and minor psychiatric morbidity in the community. A population-based approach to General Health Questionnaire data in the Health and Lifestyle Survey. Psychol Med 1993;23:475-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Craven MA, Bland R. Depression in primary care: current and future challenges. Can J Psychiatry 2013;58:442-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke DM, Currie KC. Depression, anxiety and their relationship with chronic diseases: a review of the epidemiology, risk and treatment evidence. Med J Aust 2009;190:S54-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet 2007;370:851-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2010;67:446-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patten SB, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, et al. Major depression as a risk factor for chronic disease incidence: longitudinal analyses in a general population cohort. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2008;30:407-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The global burden of disease: 2004 update Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2008. Available: www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/2004_report_update/en/ (accessed 2014 May 6).

- 8.Üstün TB. WHO Collaborative Study: an epidemiological survey of psychological problems in general health care in 15 centers worldwide. Int Rev Psychiatry 1994;6:357-63. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network. Mississauga (ON): Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network; 2013. Available: http://cpcssn.ca/ (accessed 2014 Jan. 2).

- 10.Williamson T, Green ME, Birtwhistle R, et al. Validating the 8 CPCSSN case definitions for chronic disease surveillance in a primary care database of electronic health records. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:367-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muldoon L, Dahrouge S, Russell G, et al. How many patients should a family physician have? Factors to consider in answering a deceptively simple question. Health Policy 2012;7:26-34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray M, Davies M, Boushon B. Panel size: How many patients can one doctor manage? Fam Pract Manag 2007;14:44-51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Addressing guidelines: important updates Ottawa: Canada Post Corporation; 2014:1–17. Available: www.canadapost.ca/textonly/tools/pg/manual/pgaddress-e.asp#1416938 (accessed 2014 Apr. 7).

- 14.Williamson T, Eliasziw M, Fick GH. Log-binomial models: exploring failed convergence. Emerg Themes Epidemiol 2013;10:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mueller TI, Leon AC, Keller MB, et al. Recurrence after recovery from major depressive disorder during 15 years of observational follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1000-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parikh SV, Segal ZV, Grigoriadis S, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. II. Psychotherapy alone or in combination with antidepressant medication. J Affect Disord 2009;117(Suppl 1):S15-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patten SB, Wang JL, Williams JVA, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of major depression in Canada. Can J Psychiatry 2006;51:84-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romans S, Cohen M, Forte T. Rates of depression and anxiety in urban and rural Canada. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2011;46:567-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang JL. Rural-urban differences in the prevalence of major depression and associated impairment. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2004;39:19-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patten SB. Long-term medical conditions and major depression in a Canadian population study at waves 1 and 2. J Affect Disord 2001;63:35-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Preiss K, Brennan L, Clarke D. A systematic review of variables associated with the relationship between obesity and depression. Obes Rev 2013;14:906-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prins MA, Verhaak PFM, Smit D, et al. Healthcare utilization in general practice before and after psychological treatment: a follow-up data linkage study in primary care. Scand J Prim Health Care 2014;32:117-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogrodniczuk JS, Oliffe JL. Men and depression. Can Fam Physician 2011;57:153-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simpson KRS, Meadows GN, Frances AJ, et al. Is mental health in the Canadian population changing over time? Can J Psychiatry 2012;57:324-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puyat JH, Marhin WW, Etches D, et al. Estimating the prevalence of depression from EMRs. Can Fam Physician 2013;59:445. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.