Abstract

Coordinate control of different classes of cyclins is fundamentally important for cell cycle regulation and tumor suppression, yet the underlying mechanisms are incompletely understood. Here we show that the PARK2 tumor suppressor mediates this coordination. The PARK2 E3 ubiquitin ligase coordinately controls the stability of both cyclin D and cyclin E. Analysis of approximately 5,000 tumor genomes shows that PARK2 is a very frequently deleted gene in human cancer and uncovers a striking pattern of mutual exclusivity between PARK2 deletion and amplification of CCND1, CCNE1 or CDK4—implicating these genes in a common pathway. Inactivation of PARK2 results in the accumulation of cyclin D and acceleration of cell cycle progression. Furthermore, PARK2 is a component of a new class of cullin-RING-containing ubiquitin ligases targeting both cyclin D and cyclin E for degradation. Thus, PARK2 regulates cyclin-CDK complexes, as does the CDK inhibitor p16, but acts as a master regulator of the stability of G1/S cyclins.

Proper progression through the cell cycle is dependent on an ordered sequence of events, including DNA replication, chromosome condensation and cytokinesis. In eukaryotic cells, waves of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) activity coordinate these events1–3. During the G1/S transition, cyclin D–CDK4, cyclin D–CDK6 and cyclin E–CDK2 complexes are active4. The activities of the cyclin-CDK complexes are further refined by a number of CDK inhibitors (CKIs) such as p16, which simultaneously inhibits multiple CDKs and whose gene (CDKN2A) is a frequent target of deletion in cancer5,6. These processes establish proper cell cycle control and the maintenance of genomic integrity.

Orderly and unidirectional progression from one cell cycle phase to the next is accomplished by a cascade of tightly regulated ubiquitination events targeting the cyclins2. Two families of ubiquitin ligases, the Skp/cullin/F-box–containing (SCF) complexes and the anaphase-promoting complexes (APCs), ubiquitinate and target specific cyclins for destruction7,8. For the cyclins involved in the G1/S transition, cullin-RING ligases (CRLs)—such as the SCF or SCF-like complexes—execute this process9. The FBX4-containing SCF complex (SCF4) targets cyclin D for proteolysis, and the FBXW7-containing SCF complex (SCF7) targets cyclin E for degradation10,11. It has been known for decades that cyclin levels during the G1/S transition are tightly coordinated, but how the stabilities of cyclin D and cyclin E are tied together is a fundamentally important question that has remained unanswered12.

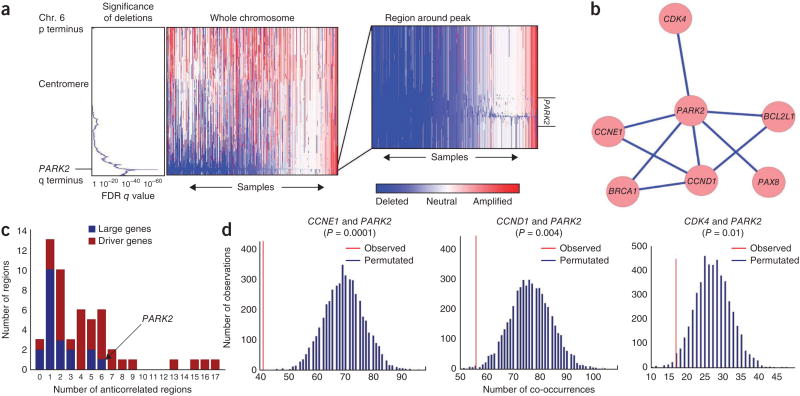

PARK2 genetic alterations are common across many human cancers as well as in hereditary Parkinson's disease13–15. In cancer, the PARK2 gene is mutated and/or deleted, with copy number loss being the primary mode of alteration13,16. One approach to determine the function of a somatic genetic alteration is to identify alterations that are mutually exclusive with it, as patterns of genetic alteration can be used to infer and inform biological pathways and function17–19. We therefore examined patterns of PARK2 deletion across 4,934 tumors spanning 11 cancer types. Deletions of PARK2 were the fourth most significant deletion among 70 significantly recurrent regions of deletion across the entire data set, and the focus (minimal commonly deleted region) of these deletions included no genes other than PARK2 (false discovery rate (FDR)-corrected q value; Fig. 1a), identifying PARK2 as the driver of this region of loss. Focal deletions of PARK2 occurred in 11% of tumors across all lineages and loss of the entire chromosome arm occurred in 19% of samples, resulting in an overall 30% rate of loss. Deletions of PARK2 were most common in serous ovarian, bladder and breast carcinomas (62%, 38% and 32% deletion rates, respectively; Supplementary Fig. 1). These pan-cancer data indicate that PARK2 is one of the most frequently deleted genes in human cancer.

Figure 1.

Genetic evidence from approximately 5,000 primary tumors suggests that PARK2 is a tumor suppressor integrally involved in cell cycle regulation. (a) GISTIC2.0 analysis across 4,934 SNP6.0 Affymetrix copy number arrays from primary tumors (The Cancer Genome Atlas, TCGA) shows high significance of deletion in a very narrow region containing the PARK2 gene. (b) Network of significant regions of amplification and deletion that anticorrelate with deletion of PARK2. (c) Extent of genetic anticorrelation between significant regions of copy number alteration. In general, driver genes anticorrelate with many more features than large genes, with PARK2 being an exception, supporting its tumor suppressive role. (d) Significance of anticorrelations between PARK2 deletion and amplification of CCND1, CCNE1 and CDK4. Each graph represents the distribution of co-occurrences of PARK2 deletion and amplification of one of three cell cycle–related genes in our lineage-controlled permutations. The red line represents the observed number of co-occurrences. Blue lines represent the predicted number of co-occurrences in the absence of a correlative relationship, as calculated by multiple permutations. P values that correspond to these graphs are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Focal deletions involving PARK2 were significantly anticorrelated with focal amplifications of five known oncogenes (CCND1, CCNE1, CDK4, BCL2L1 and PAX8) and one known tumor suppressor (BRCA1; Fig. 1b and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). We identified these instances of anticorrelation after rigorously controlling for tumor lineage and for overall levels of genomic disruption; both of these factors can confound correlation analyses (Online Methods)20,21. PARK2 deletions anticorrelated with more recurrent somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) than deletion of any other large gene, suggesting that loss of PARK2 is selected for because of its contribution to tumorigenic potential rather than occurring passively (Fig. 1c). Many of the largest genes in the genome tend to be recurrently deleted, with 20 of the top 70 most frequently deleted regions containing 1 of the 100 largest genes in the genome21. Many deletions encompassing large genes might arise owing to processes that occur during cancer evolution, rather than contributing to oncogenesis13,22. In this case, we expect that SCNAs affecting regions containing large genes would show few anticorrelations with other regions of significant alteration. Among the 34 significant regions with known driver genes and 20 significant regions with large genes, driver genes exhibited significantly more anticorrelations with other regions (median of 1 and 4 anticorrelations for large genes and driver genes, respectively; MWW = 0.0002; Fig. 1c)21. However, PARK2 deletion was an exception to this trend, with only three other significant deletions having more interactions than PARK2—STK11, NF1 and BRCA1—all known tumor suppressors that often undergo copy number loss. These findings strongly support a tumor suppressive role for PARK2 in human tumors and suggest that PARK2 deletions might serve some of the same functions as the alterations with which they anticorrelate.

The genetic relationship between PARK2, CCND1 (cyclin D1), CCNE1 (cyclin E1) and CDK4 is particularly intriguing. Cyclin D1, cyclin E1 and CDK4 all control G1/S progression and are all encoded by oncogenes that are frequently amplified in many different types of human malignancy13,23–25. One possibility is that, if PARK2 loss serves a similar function as copy gains of these cyclin genes and CDK4, this redundancy should lead to anticorrelation of these events in primary tumors19,26,27. Our analysis, which used a lineage control to detect anticorrelations between peak regions of significance, found strong anticorrelation between the presence of amplifications at the loci containing CCNE1 and CCND1, as expected, as well as between the presence of amplification of either of these regions and PARK2 loss (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 2). The anticorrelations between PARK2 loss and CCND1, CCNE1 and CDK4 gain were highly statistically significant and were much stronger than would be expected in the absence of selective pressure (Fig. 1d). These relationships were especially strong in tumor lineages where CCND1, CCNE1 or CDK4 amplification is frequent and is known to have an oncogenic role (i.e., breast and ovarian lineages). Such a pattern of mutual exclusivity is consistent with PARK2, cyclin D1, cyclin E1 and CDK4 functioning in a common pathway19,26,27.

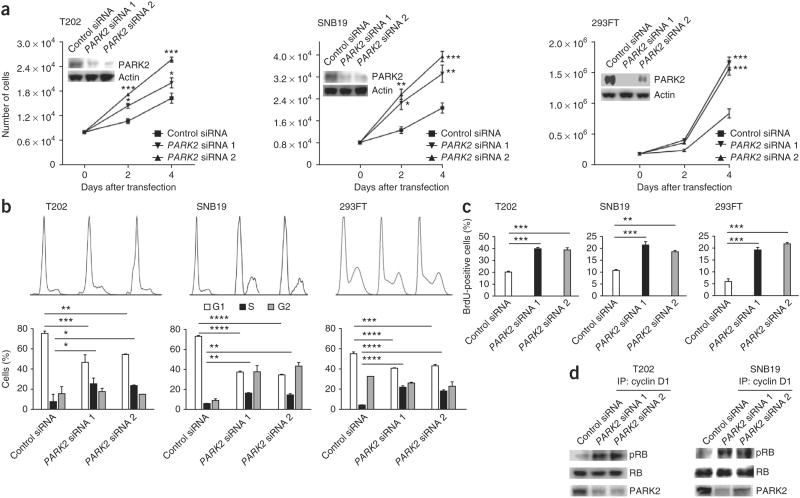

Although our genetic data implicate a functional relationship between PARK2 and cyclin D1, cyclin E1 and CDK4, the molecular mechanisms underlying this relationship are unclear. To characterize the effects of PARK2 inactivation in cells, we knocked down PARK2 in three different cell lines with intact PARK2 expression and examined the effects on cell proliferation. In all lines tested, depletion of PARK2 resulted in increased proliferation (Fig. 2a,b). Accordingly, inactivation of PARK2 resulted in significantly greater numbers of cells undergoing DNA synthesis (determined through analysis of 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation) (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 2). We next measured the amount of cyclin D1–CDK complex–dependent RB phosphorylation activity after PARK2 knockdown. We observed that enhanced cell cycle progression after PARK2 depletion was accompanied by an increase in cyclin D–CDK complex–mediated RB phosphorylation activity (Fig. 2d). To study global changes in the transcriptome resulting from PARK2 depletion, we performed expression array analyses with two cell lines (SF539 and SNB19) (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 3). Pathway analysis of genes with altered expression showed consistent enrichment of the transcriptional programs governing cell growth and cell cycle control (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 4). Depletion of PARK2 resulted in the consistent upregulation of genes associated with cell growth and proliferation (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

Figure 2.

PARK2 regulates cell cycle progression and proliferation. (a) Growth curves showing increased cell proliferation after PARK2 knockdown in the indicated cells. Protein blots showing PARK2 levels 48 h after transfection with two independent siRNAs or with scrambled siRNA control are shown in the insets. Experiments were performed in triplicate. (b) Cell cycle analysis showing a greater number of cells entering S phase after PARK2 knockdown. The indicated cell lines were either transfected with one of two PARK2 siRNAs or with scrambled siRNA control, in triplicate. Top, FACS distributions; bottom, numbers of cells in specific cell cycle phases. (c) BrdU incorporation assays showing increased DNA synthesis after PARK2 knockdown. Experiments were performed in triplicate. (d) PARK2 depletion causes increased cyclin D1–CDK complex activity. The indicated cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA control or with PARK2 siRNAs. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibody to cyclin D1 (IP). Purified RB protein and the immunoprecipitated cyclin-CDK complexes were incubated in the presence of ATP for 30 min at 37 °C. Protein blotting with antibodies specific for phosphorylated RB (pRB) and total RB was used to evaluate RB phosphorylation. Representative results from triplicate experiments are shown. T202 is a colon cancer line, and SNB19 is a GBM line. Error bars, 1 s.d. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, t test.

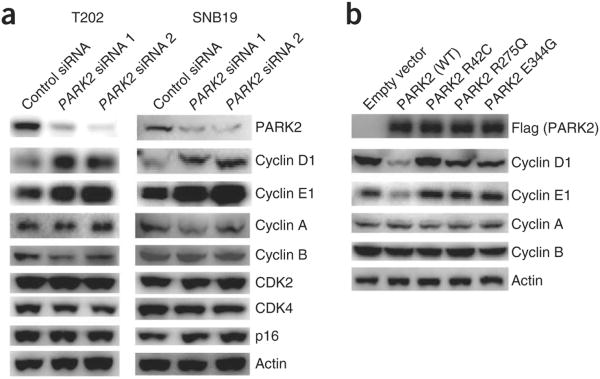

PARK2 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets proteins for destruction, and mutations in the PARK2 gene in both cancer and Parkinson's disease inactivate this function15,16,28–32. Given this observation and our genetic data implicating PARK2 in cyclin biology (Fig. 1), we examined how inactivation of PARK2 affected the protein levels of key components of the cell cycle machinery (Fig. 3a). Knockdown of PARK2 resulted in a substantial accumulation of the cyclin D1 and cyclin E1 proteins but not of other cell cycle effectors. This accumulation of cyclin D1 and cyclin E1 was not due to increased transcription of the corresponding genes (Supplementary Fig. 5). We also found that the protein levels of cyclin D2 and cyclin D3 were higher after PARK2 knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 6). Furthermore, overexpression of the PARK2 E3 ubiquitin ligase resulted in a coordinate decrease in the levels of cyclin D1 and cyclin E1 but not in the levels of cyclin A and cyclin B (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, PARK2 mutations that we previously identified in cancer16 abrogated the ability of the E3 ligase to degrade both cyclin D1 and cyclin E1. In combination, these data demonstrate that PARK2 is required for the normal regulation of cyclin D and cyclin E levels and that cancer-specific mutations affecting PARK2 abrogate its ability to target these cyclins for degradation.

Figure 3.

Coordinate control of cyclin D and cyclin E by the PARK2 ubiquitin ligase. (a) Knockdown of PARK2 results in increased cyclin D and cyclin E levels but not in altered levels of other cyclins, CDKs or p16. The indicated cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA control or with PARK2 siRNAs, and protein blots were performed with the indicated antibodies. Representative results are shown from triplicate experiments. (b) Expression of wild-type (WT) but not mutant PARK2 decreases cyclin D1 and cyclin E1 levels but not those of cyclin A or cyclin B. T98G glioma cells were transfected with vector only (pcDNA3.1) or with vector encoding wild-type PARK2 (Flag tagged) or one of three mutant PARK2 proteins (Flag tagged).

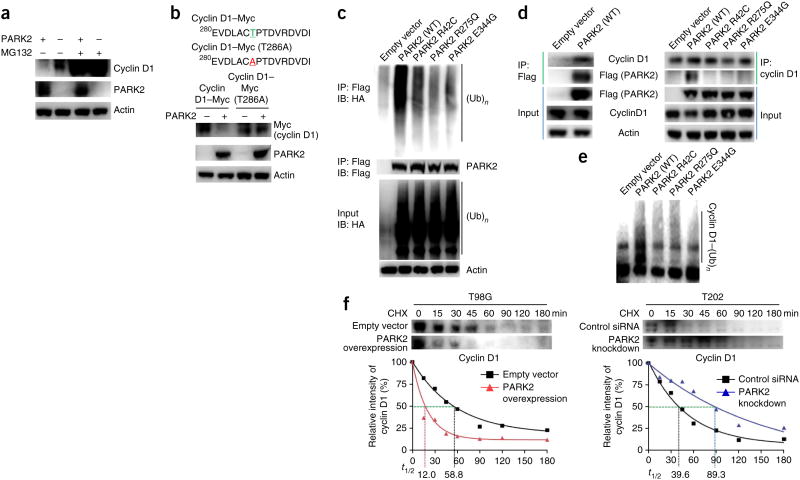

We next examined the molecular details of how PARK2 controls the amount of cyclin D1 protein. PARK2-mediated degradation of cyclin D1 was dependent on the proteasome, as it could be reversed using the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (ref. 33) (Fig. 4a). Moreover, the Thr286Ala mutant of cyclin D1 was resistant to degradation by PARK2 (Fig. 4b). As phosphorylation of cyclin D1 at Thr286 is required for its ubiquitin-mediated degradation by SCF4, these data show that PARK2-mediated destruction of cyclin D1 is dependent on this process34,35. PARK2 mutations that we previously identified in cancer16 abrogated E3 ligase activity (Fig. 4c). We found that wild-type PARK2 directly bound to and ubiquitinated cyclin D1, whereas cancer-specific mutations affecting PARK2 abrogated its ability to do both (Fig. 4d,e). PARK2 also interacted with cyclin D2 and cyclin D3 (Supplementary Fig. 7). Overexpression of PARK2 in cells lacking PARK2 resulted in a significant decrease in the half-life of cyclin D1, whereas knockdown of PARK2 in cells that expressed the protein resulted in an increase in cyclin D1 half-life (Fig. 4f).

Figure 4.

Molecular mechanisms of PARK2 regulation of cyclin D1 protein. (a) PARK2-dependent cyclin D1 degradation is mediated by the proteasome. Cyclin D1 levels are shown in T98G cells transfected with empty vector or with vector encoding PARK2, in the presence or absence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (25 μM). (b) A phosphorylation-deficient cyclin D1 mutant (Thr286Ala) is resistant to PARK2-mediated degradation. T98G cells were transfected with either empty vector or vector expressing wild-type PARK2 together with vector encoding either wild-type or mutant (Thr286Ala) Myc-tagged cyclin D1. (c) Tumor-derived mutations disrupt PARK2-mediated ubiquitin ligase activity in cancer cells. T98G cells were transfected with vector encoding hemagglutinin-tagged ubiquitin (HA-Ub) and with either vector only (pcDNA3.1) or with vector encoding wild-type PARK2 (Flag tagged) or one of three mutant PARK2 proteins (Flag tagged). Assays were performed as previously described16. IB, immunoblot. (d) Wild-type but not mutant PARK2 associates with cyclin D1. Left, immunoprecipitation assays showing binding of wild-type PARK2 to endogenous cyclin D1. Right, immunoprecipitation of Flag-tagged PARK2 constructs demonstrating that mutated PARK2 proteins lose binding to cyclin D1. (e) PARK2 ubiquitinates cyclin D1 in vitro. In vitro ubiquitination assays showing the cyclin D1 ubiquitin ligase activity of wild-type and mutant PARK2. PARK2 mutants have decreased cyclin D1 ubiquitination activity. (f) PARK2 regulates the half-life (t1/2) of cyclin D1 protein. Time course showing the levels of cyclin D1 at various time points after pulse treatment of cells with cycloheximide (CHX; 10 μM). Left, ectopic expression of PARK2 reduced the half-life of cyclin D1 in T98G cells (cells lacking PARK2 expression). Right, PARK2 knockdown increased cyclin D1 half-life in T202 cells (cells with PARK2 expression). Results are representatitve of triplicate experiments.

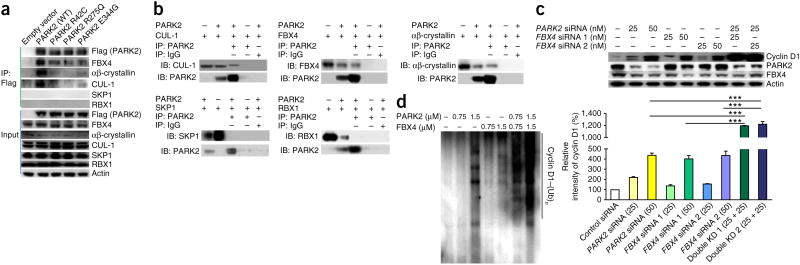

Cyclins are ubiquitinated and marked for proteasome-dependent degradation by CRL complexes36. Although FBX4 is a known mediator of cyclin D destruction, its activity does not fully account for all cyclin D regulation37–39. We next sought to determine whether PARK2 acts within the context of an SCF-related CRL complex. We found that PARK2 is a component of a new FBX4-containing SCF-like ubiquitin ligase complex (Fig. 5a). The PARK2-containing CRL complex includes the E3 ligase FBX4, the scaffold protein cullin-1 (CUL-1) and αβ-crystallin but not SKP1 or RBX1 (hereafter referred to as PCF4; Fig. 5a). The PCF4 complex bears similarity to SCF4, and this complex also ubiquitinates and targets cyclin D1 for destruction in a phosphorylation-dependent manner (Thr286)35. We verified the interaction of PARK2 and CRL components by systematically expressing these proteins in combination using baculoviruses and characterizing their associations (Fig. 5b). As expected, PARK2 interacted with FBX4, CUL-1 and αβ-crystallin but not with SKP1 or RBX1. These data indicate that PARK2 is a component of a new SCF-like ubiquitin complex that targets cyclin D1 for destruction.

Figure 5.

PARK2 is a component of new ubiquitin ligase complexes controlling cyclin D degradation. (a) PARK2 associates with a new complex containing FBX4, CUL-1 and αβ-crystallin (PCF4). T98G cells were transfected with vector encoding wild-type or mutant Flag-tagged PARK2 as indicated. Equal amounts of lysate were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibody to Flag followed by protein blotting with the indicated antibodies. (b) Recapitulation of PARK2 binding associations using baculoviruses. Sf9 cells were cotransduced with baculoviruses encoding PARK2 and other proteins as indicated. Associated proteins were copurified using immunoprecipitation. PARK2 binds to CUL-1, FBX4 and αβ-crystallin but not to RBX1 or SKP1. (c) Synergistic effects of PARK2 and FBX4 on the regulation of cyclin D1 stability. T202 cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA control or with a combination of PARK2 and FBX4 siRNAs as indicated. The graph shows quantification of the results from triplicate experiments. Numbers in parentheses represent the concentrations (in nM) of siRNA. Error bars, 1 s.d. ***P < 0.001, t test. KD, knockdown. (d) PARK2 and FBX4 synergize in cyclin D1 ubiquitination in assays in vitro. Purified proteins were used at the indicated concentrations.

Because both PARK2 and FBX4 can bind to and ubiquitinate cyclin D, we wondered what the functional relationship was between these two E3 ligases. To address this question, we knocked down FBX4, PARK2 or both genes simultaneously and characterized the resultant effects on cyclin D1 protein levels. Loss of either FBX4 or PARK2 alone resulted in accumulation of cyclin D1 protein (Fig. 5c). Moderate loss of both ubiquitin E3 ligases resulted in a synergistic effect, leading to dramatic accumulation of cyclin D1. When recombinant PARK2 and FBX4 were combined in vitro, the E3 ligases clearly synergized to ubiquitinate cyclin D1 (Fig. 5d). Taken together, these data show that PARK2 and FBX4 work together to regulate cyclin D.

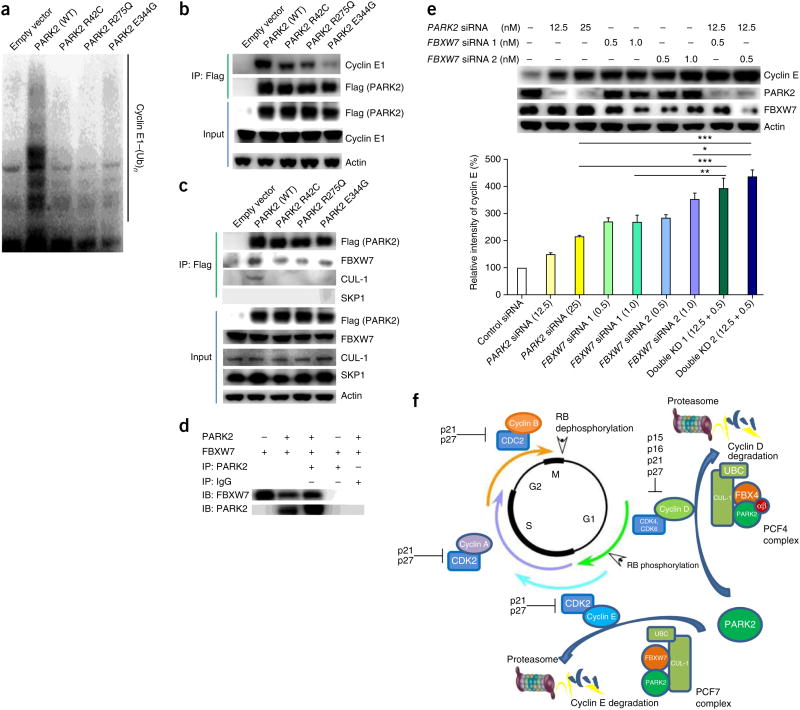

Along with regulating cyclin D levels during the G1/S transition, PARK2 also targets cyclin E for degradation. Depletion of PARK2 with small interfering RNA (siRNA) resulted in accumulation of cyclin E1 protein (Fig. 3a). Overexpression of wild-type but not mutant PARK2 resulted in a decrease in cyclin E1 levels but not in the levels of cyclin A or cyclin B (Fig. 3b). Using in vitro ubiquitination assays, we found that, as with cyclin D1, wild-type PARK2 ubiquitinated cyclin E1, but cancer-specific mutations affecting PARK2 abrogated the ability of the E3 ligase to do so (Fig. 6a). Furthermore, wild-type PARK2 can bind to cyclin E1, whereas PARK2 mutations found in cancer disrupt this association16,40 (Fig. 6b). Using immunoprecipitation, we found that PARK2 binds cyclin E1 and FBXW7 and is part of an SCF-like ubiquitin complex that contains both FBXW7 and CUL-1 but not SKP1 (hereafter called PCF7)41–43 (Fig. 6b,c). As with cyclin D, mutations affecting PARK2 disrupted its ability to bind to components of this CRL complex (Fig. 6c). We validated the association of PARK2 and FBXW7 by expressing both proteins using baculoviruses and demonstrated that the two proteins precipitate together (Fig. 6d). We then knocked down PARK2 and FBXW7 individually or simultaneously, as with FBX4 (Fig. 6e). Depletion of either protein increased cyclin E1 levels. However, in contrast to results with FBX4 depletion, knockdown of PARK2 and FBXW7 together had an additive effect on cyclin E1 degradation, as least in the system we employed. Thus, as in the PCF4 complex, PARK2 and FBXW7 cooperate in the PCF7 complex to ubiquitinate cyclin E, albeit with different kinetics. Nevertheless, as part of PCF complexes, PARK2 coordinates the levels of multiple G1/S cyclins and, in essence, acts analogously to p16, although at the level of cyclin stability (Fig. 6f).

Figure 6.

PARK2 is a master regulator of G1/S cyclin stability. (a) PARK2 ubiquitinates cyclin E1 in vitro. In vitro ubiquitination assays showing the cyclin E1 ubiquitin ligase activity of wild-type and mutant PARK2. PARK2 mutations decrease cyclin E1 ubiquitination activity. (b) Cancer-derived PARK2 mutants have decreased association with cyclin E1. Immunoprecipitation of Flag-tagged PARK2 was followed by protein blotting with the indicated antibodies. (c) PARK2 is associated with a complex containing FBXW7 and CUL-1 but not SKP1 (PCF7). T98G cells were transfected with vector encoding Flag-tagged wild-type PARK2 or one of three PARK2 mutants. Equal amounts of lysate were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibody to Flag followed by protein blotting with the indicated antibodies. (d) Recapitulation of PARK2 and FBXW7 binding using baculoviruses. Sf9 cells were cotransduced with baculoviruses expressing PARK2 and FBXW7. Associated proteins were copurified using immunoprecipitation and detected using protein blotting. (e) Additive relationship of PARK2 and FBXW7 on the regulation of cyclin E1 stability. T202 cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA control or with a combination of PARK2 and FBXW7 siRNAs as indicated. The graph shows quantification from triplicate experiments. Numbers in parentheses represent the concentrations (in nM) of siRNA. Error bars, 1 s.d. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, t test. (f) Model of coordinate regulation of multiple G1/S cyclins by PARK2-based ubiquitin E3 ligase complexes. PARK2-containing PCFs control both cyclin D and cyclin E stability. αβ, αβ-crystallin.

Colorectal cancers (CRCs) can harbor substantial numbers of FBXW7 mutations and PARK2 deletions. Interestingly, most tumors contained an alteration in either FBXW7 or PARK2, although a small set of tumors did have alterations in both genes (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Our findings have a number of critical implications. Notably, we provide a mechanistic basis for how different classes of cyclins can be coregulated at the protein level. Although transcriptional mechanisms have a role in regulating cyclin D and cyclin E, these mechanisms do not explain the rapid, coordinated changes in protein levels that occur. Our data demonstrate that new PARK2-based ubiquitin E3 complexes (PCFs) help mediate this coordination. Regulation of the activity of these complexes may involve a number of other processes such as post-translational modification, as is common for the fine-tuning of CRL complex activity9,44–47.

PARK2 can affect a number of processes that differ depending on cell type. In neural models, it can regulate processes such as cell survival and mitochondrial motility and clearance31,40,48–53. The genetic relationship between somatic events in PARK2, CCND1, CCNE1 and CDK4 strongly implicates these genes in a common aberrant process in cancer cells—the disruption of cell cycle control. Our observations show that PARK2 can control the activity of multiple proteins that regulate cell growth. Notably, genes that reside at such nodal points, such as TP53, are frequent targets of mutation in cancer cells. PARK2 may be such a gene. We believe our study has wide implications for understanding both cell cycle regulation and oncogenesis.

Online Methods

Genomic analyses

GISTIC2.0 analysis was performed across 11 primary tumor lineages as outlined previously20,21. To identify significant regions that anticorrelated with one another, we performed a permutation test that maintained the overall SCNA distribution and event structure and controlled for each of the 11 lineages in the TCGA Pan-Cancer data set (colon and rectal cancers were combined into a single group)21. We looked for interactions between the 34 regions with known drivers (23 amplifications and 11 deletions), as well as the 20 regions of significant deletion that contained large genes (54 regions in total). The Benjamini-Hochberg method was used to correct for FDR54, and anticorrelations with an FDR P value of less than or equal to 0.25 were considered significant.

Cell culture

Cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured using recommended media supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen) and penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Specifically, DMEM (Invitrogen) was used to culture SNB19, T98G and HEK 293FT cells, MEM (Invitrogen) was used to culture SF539 cells and MEM+NEAA (Invitrogen) was used to culture T202 cells. Grace's Insect Cell Culture Medium (Invitrogen) was used for Sf9 insect cells. Growth curve assays were performed with Vi-CELL Cell Viability Analyzers (Beckman Coulter). All experiments were performed in triplicate. All cells were tested and confirmed to be negative for mycoplasma.

siRNA knockdown and plasmid transfection

siRNAs to PARK2, FBX4 and FBXW7 were obtained from Invitrogen and Integrated DNA Technologies. The targeted sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 5. siRNAs were transfected into cells in antibiotic-free medium using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen), medium was changed after 4–6 h and cells were collected after 48 h. For exogenous expression, cells were transfected with Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) in serum- and antibiotic-free medium. The medium was changed after 4–6 h, and cells were collected after 48 h.

Baculovirus expression in insect cells

Full-length human cDNAs for PARK2, CUL-1, SKP1, RBX1, FBX4, αβ-crystallin and FBXW7 were cloned into pENTR-D-TOPO (Invitrogen). All constructs were verified by Sanger sequencing. The LR reaction was performed between the entry clone and C-terminal BaculoDirect linear DNA (Invitrogen) to generate recombinant baculovirus DNA, as directed by the manufacturer. Sf9 insect cells were coinfected with different combinations of baculovirus and grown to produce protein. Cells were collected and lysed for immunoprecipitation in buffer containing 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol.

Flow cytometry

Cells were trypsinized, fixed and stained using standard methods (BD Biosciences). Cell cycle and BrdU analyses were performed using a FACSCalibur laser flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems). Ten thousand events were acquired for each sample. Results were quantified using FlowJo software.

Immunoprecipitation

Cells were collected and lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40), 0.02% NaN3) containing protease inhibitors. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 12,000g for 10 min, and protein concentration was determined using a BCA assay kit (Thermo). For immunoprecipitation assays on endogenous protein, samples were incubated with antibodies (40 μl of antibody to cyclin D1 (72-13G, sc-450, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); 10 μl of antibody to PARK2 (4211, Cell Signaling Technology); or 3.3 μl of non-specific mouse IgG (Invitrogen)). Proteins were precipitated using protein A–Sepharose beads that had been blocked with 3% powdered milk in TBS. For samples from cells transfected with constructs encoding Flag-tagged protein, EZview Red ANTI-FLAG M2 Affinity Gel (Sigma) was used according to the manufacturer's protocol. Beads were washed four times with lysis buffer and then mixed with 2× Laemmli sample buffer. Protein blotting was performed using standard methods.

Antibodies

Antibodies used included those against Flag (Sigma, F7425), actin (Sigma, A2066), PARK2 (Cell Signaling Technology, 4211 and 2132), FBXW7 (Aviva Systems Biology, ARP47419), cyclin E1 (Cell Signaling Technology, 4129), FBXO4 (Rockland, 100-401-963; Abcam, ab153803; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-134721), cyclin A2 (Cell Signaling Technology, 4656), cyclin B1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-245), cyclin D1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-450; Cell Signaling Technology, 2922 and 2926), cyclin D2 (Cell Signaling Technology, 3741), cyclin D3 (Cell Signaling Technology, 2936), CDK2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 163), CDK4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 260), αβ-crystallin (Enzo Life Science, ADI-SPA-223), GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology, 2118), SKP1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-7163), CUL-1 (Invitrogen, 71-8700), p16 (Cell Signaling Technology, 4824), Myc tag (Cell Signaling Technology, 2272), RB (Cell Signaling Technology, 9313), phosphorylated RB Ser795 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9301) and RBX1 (Invitrogen, 34-2500). Antibodies were used at 1:1,000 dilutions.

RB kinase assays

Detection of phosphorylation of RB was modified from the method of Gitig and Koff55. Briefly, cells were lysed in buffer containing 50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% Tween-20, 10% glycerol, 80 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM NaF, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail. Lysates were incubated with 1 μl of antibody to cyclin D1 (72-13G, sc-450, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and precipitated using protein A–Sepharose beads. Samples were eluted into kinase buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, containing 7.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT and 10% glycerol) and supplemented with 200 μM ATP and purified glutathione S-transferase (GST)-RB protein substrate. After incubation for 30 min at 37 °C, reactions were terminated and analyzed by protein blotting.

Protein stability and half-life analyses

Protein stability and half-life were measured using a standard cycloheximide release assay56. For analysis of cyclin D1 decay after the inhibition of protein synthesis, cells were treated with cycloheximide (Sigma) at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml 48 h after transfection (time 0). Cell extracts from each time point were analyzed by protein blotting. Protein intensity was quantified and measured using ImageJ software (Research Services Branch, US National Institutes of Health).

Ubiquitination assays

In vivo ubiquitination assays were performed as previously described29. In vitro ubiquitination assays were performed using a commercial ubiquitination kit (Boston Biochem) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Expression microarray analysis

RNA was extracted and analyzed on Affymetrix U133A 2.0 expression arrays. Data were imported into Partek Genomics Suite 6.5 and were background corrected, log2 transformed and quantile normalized with Robust Mutliarray Average (RMA). Differentially expressed probes in cells with PARK2 knockdown compared to cells transfected with scrambled siRNA were identified in each cell line and were ranked by P value. The top ranked differentially expressed probes in each cell line were stringently filtered using standard methods57,58 to only keep those altered in consistent directions in both cell lines (4,255 probes) with an absolute alteration ratio of > 1.1 (3,378 probes). These probes were then interrogated using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.7 for functional category enrichment. Functional categories in the Gene Ontology (GO), Biocarta and SwissProt–Protein Information Resource (SP-PIR) were curated, and P values were calculated using EASE scores, from a conservative modification of Fisher's exact test with FDR correction.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Approximately 1 μg of RNA extracted from each cell line was used to generate cDNA with SuperScript III (Invitrogen). Reactions were performed using a MasterCycler Epgradient S instrument and Realplex software (Eppendorf). Primers for cyclin D1 (CCND1) and cyclin E1 (CCNE1) are listed in Supplementary Table 5. The 2ΔΔCt method was used to calculate ΔΔCt values. mRNA expression levels of target genes were normalized against GAPDH levels. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed at least in triplicate. Statistical significance was evaluated using either t tests or ANOVA as appropriate.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Examples of PARK2 locus profiles from distinct cancer lineages. Copy number data from the TCGA. Representative types of malignancies are shown. SCNA profiles of chromosome 6 (left) and a 5Mb region surrounding PARK2 (right) are shown in the three lineages that had the highest frequency of PARK2 deletions: ovarian cancer (a), breast cancer (b), and bladder cancer (c).

Supplementary Figure 2. PARK2 regulates cell cycle progression. FACS data from three cell lines as indicated. Cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA control or with PARK2 siRNAs. DNA content and BrdU incorporation were measured after PARK2 knockdown. Representative results are shown from triplicate experiments.

Supplementary Figure 3. PARK2 knockdown results in alterations in gene expression. The indicated cells were treated with scrambled siRNA or PARK2 siRNA as shown. The heat map shows the top 50 genes with increased expression.

Supplementary Figure 4. Pathway analyses of 2,698 genes differentially expressed across 2 cell lines transfected with PARK2 siRNAs. Significant enrichment is shown in transcriptional programs governing cell growth, proliferation, protein ubiquitination, and cell cycle control.

Supplementary Figure 5. Gene expression does not change for cyclins D1 and E1 after PARK2 knockdown. Two independent PARK2 siRNAs were used. Experiments were repeated five times. Error bars, 1 standard deviation. NS, not significant.

Supplementary Figure 6. PARK2 knockdown causes accumulation of cyclin D2 and D3 protein. T202 cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA control or with PARK2 siRNAs and protein blots were performed with the antibodies specific for each cyclin type as indicated. Representative results are shown from triplicate experiments.

Supplementary Figure 7. Immunoprecipitation assays show binding of wild-type PARK2 to endogenous cyclins D2 and D3. HEK 293T cells were transfected with either vector only (pcDNA3.1) or with vector encoding wild-type PARK2. Assays were performed as described in Online Methods.

Supplementary Figure 8. Patterns of genetic alteration of FBXW7 and PARK2 in colorectal cancer. In colorectal cancer, FBXW7 is primarily mutated while PARK2 is deleted and mutated. Shown are data from The Cancer Genome Atlas Project (http://www.cbioportal.org/public-portal/). Point mutations are noted in green and deletions are noted in blue. Percentages denote total numbers of tumors with alterations in the gene. p, not significant.

Supplementary Table 1. Pan-cancer regions of significant SCNA and PARK2 anticorrelates.

Supplementary Table 2. Significance of PARK2 anticorrelates.

Supplementary Table 5. Quantitative RT-PCR Primer and siRNA target sequences.

Supplementary Table 3. Gene expression changes after PARK2 knockdown.

Supplementary Table 4. Pathway analyses based on genes differentially expressed after PARK2 knockdown.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Holland, A.C. Koff and J. Huse for helpful advice. S.T. was a recipient of a US National Institutes of Health T32 grant (5T32CA160001). This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (RO1 NS086875-01) (T.A.C.), the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Brain Tumor Center (T.A.C.), the Sontag Foundation (T.A.C.) and the Frederick Adler Fund (T.A.C.).

Footnotes

Accession codes. Microarray data have been accessioned with the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under series GSE50864.

Note: Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper.

Author Contributions: T.A.C., Y.G., T.I.Z. and R.B. designed the experiments. Y.G., T.I.Z., K.L., I.-L.T., S.T., S.V., S.M., A.V., S.E.S. and P. P. performed the experiments. Y.G., T.A.C., R.B., T.I.Z. and L.G.T.M. analyzed the data. E.H. and R.R. contributed new reagents. T.A.C., Y.G., T.I.Z. and R.B. wrote the manuscript.

Competing Financial Interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://www.nature.com/reprints/index.html.

References

- 1.Ang XL, Wade Harper J. SCF-mediated protein degradation and cell cycle control. Oncogene. 2005;24:2860–2870. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teixeira LK, Reed SI. Ubiquitin ligases and cell cycle control. Annu Rev Biochem. 2013;82:387–414. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060410-105307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vodermaier HC. APC/C and SCF: controlling each other and the cell cycle. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R787–R796. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nurse P. Checkpoint pathways come of age. Cell. 1997;91:865–867. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80476-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nobori T, et al. Deletions of the cyclin-dependent kinase-4 inhibitor gene in multiple human cancers. Nature. 1994;368:753–756. doi: 10.1038/368753a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamb A, et al. A cell cycle regulator potentially involved in genesis of many tumor types. Science. 1994;264:436–440. doi: 10.1126/science.8153634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deshaies RJ. SCF and Cullin/Ring H2-based ubiquitin ligases. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:435–467. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stegmeier F, et al. Anaphase initiation is regulated by antagonistic ubiquitination and deubiquitination activities. Nature. 2007;446:876–881. doi: 10.1038/nature05694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skaar JR, Pagan JK, Pagano M. Mechanisms and function of substrate recruitment by F-box proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:369–381. doi: 10.1038/nrm3582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ackman JB, Ramos RL, Sarkisian MR, Loturco JJ. Citron kinase is required for postnatal neurogenesis in the hippocampus. Dev Neurosci. 2007;29:113–123. doi: 10.1159/000096216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winston JT, Koepp DM, Zhu C, Elledge SJ, Harper JW. A family of mammalian F-box proteins. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1180–1182. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)80021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diehl JA, Zindy F, Sherr CJ. Inhibition of cyclin D1 phosphorylation on threonine-286 prevents its rapid degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Genes Dev. 1997;11:957–972. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.8.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beroukhim R, et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature. 2010;463:899–905. doi: 10.1038/nature08822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veeriah S, Morris L, Solit D, Chan TA. The familial Parkinson disease gene PARK2 is a multisite tumor suppressor on chromosome 6q25.2-27 that regulates cyclin E. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1451–1452. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.8.11583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lücking CB, et al. Association between early-onset Parkinson's disease and mutations in the parkin gene. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1560–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005253422103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veeriah S, et al. Somatic mutations of the Parkinson's disease–associated gene PARK2 in glioblastoma and other human malignancies. Nat Genet. 2010;42:77–82. doi: 10.1038/ng.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ciriello G, Cerami E, Sander C, Schultz N. Mutual exclusivity analysis identifies oncogenic network modules. Genome Res. 2012;22:398–406. doi: 10.1101/gr.125567.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaske CJ, et al. Inference of patient-specifc pathway activities from multi-dimensional cancer genomics data using PARADIGM. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:i237–i245. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell. 1996;87:159–170. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mermel CH, et al. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R41. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-r41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zack TI, et al. Pan-cancer patterns of somatic copy number alteration. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1134–1140. doi: 10.1038/ng.2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bignell GR, et al. Signatures of mutation and selection in the cancer genome. Nature. 2010;463:893–898. doi: 10.1038/nature08768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hinds PW, Dowdy SF, Eaton EN, Arnold A, Weinberg RA. Function of a human cyclin gene as an oncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:709–713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosokawa Y, Arnold A. Cyclin D1/PRAD1 as a central target in oncogenesis. J Lab Clin Med. 1996;127:246–252. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(96)90092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.An HX, Beckmann MW, Reifenberger G, Bender HG, Niederacher D. Gene amplification and overexpression of CDK4 in sporadic breast carcinomas is associated with high tumor cell proliferation. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:113–118. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65257-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wood LD, et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2007;318:1108–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.1145720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nat Med. 2004;10:789–799. doi: 10.1038/nm1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poulogiannis G, et al. PARK2 deletions occur frequently in sporadic colorectal cancer and accelerate adenoma development in Apc mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:15145–15150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009941107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimura H, et al. Familial Parkinson disease gene product, parkin, is a ubiquitin-protein ligase. Nat Genet. 2000;25:302–305. doi: 10.1038/77060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka K, et al. Parkin is linked to the ubiquitin pathway. J Mol Med. 2001;79:482–494. doi: 10.1007/s001090100242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarraf SA, et al. Landscape of the PARKIN-dependent ubiquitylome in response to mitochondrial depolarization. Nature. 2013;496:372–376. doi: 10.1038/nature12043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitada T, et al. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature. 1998;392:605–608. doi: 10.1038/33416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee DH, Goldberg AL. Selective inhibitors of the proteasome-dependent and vacuolar pathways of protein degradation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27280–27284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alt JR, Cleveland JL, Hannink M, Diehl JA. Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of cyclin D1 nuclear export and cyclin D1–dependent cellular transformation. Genes Dev. 2000;14:3102–3114. doi: 10.1101/gad.854900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin DI, et al. Phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination of cyclin D1 by the SCFFBX4-αB crystallin complex. Mol Cell. 2006;24:355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakayama KI, Nakayama K. Regulation of the cell cycle by SCF-type ubiquitin ligases. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaites LP, et al. The Fbx4 tumor suppressor regulates cyclin D1 accumulation and prevents neoplastic transformation. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:4513–4523. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05733-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanie T, et al. Genetic reevaluation of the role of F-box proteins in cyclin D1 degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:590–605. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06570-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barbash O, et al. Mutations in Fbx4 inhibit dimerization of the SCFFbx4 ligase and contribute to cyclin D1 overexpression in human cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Staropoli JF, et al. Parkin is a component of an SCF-like ubiquitin ligase complex and protects postmitotic neurons from kainate excitotoxicity. Neuron. 2003;37:735–749. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strohmaier H, et al. Human F-box protein hCdc4 targets cyclin E for proteolysis and is mutated in a breast cancer cell line. Nature. 2001;413:316–322. doi: 10.1038/35095076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rajagopalan H, et al. Inactivation of hCDC4 can cause chromosomal instability. Nature. 2004;428:77–81. doi: 10.1038/nature02313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minella AC, Clurman BE. Mechanisms of tumor suppression by the SCFFbw7. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1356–1359. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.10.2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ko HS, et al. Phosphorylation by the c-Abl protein tyrosine kinase inhibits parkin's ubiquitination and protective function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:16691–16696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006083107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wauer T, Komander D. Structure of the human Parkin ligase domain in an autoinhibited state. EMBO J. 2013;32:2099–2112. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kao SY. DNA damage induces nuclear translocation of parkin. J Biomed Sci. 2009;16:67. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang C, et al. Parkin, a p53 target gene, mediates the role of p53 in glucose metabolism and the Warburg effect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16259–16264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113884108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang X, et al. PINK1 and Parkin target Miro for phosphorylation and degradation to arrest mitochondrial motility. Cell. 2011;147:893–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trempe JF, Fon EA. Structure and function of Parkin, PINK1, and DJ-1, the three musketeers of neuroprotection. Front Neurol. 2013;4:38. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2013.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trempe JF, et al. Structure of parkin reveals mechanisms for ubiquitin ligase activation. Science. 2013;340:1451–1455. doi: 10.1126/science.1237908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson BN, Berger AK, Cortese GP, Lavoie MJ. The ubiquitin E3 ligase parkin regulates the proapoptotic function of Bax. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:6283–6288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113248109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang H, et al. Parkin regulates paclitaxel sensitivity in breast cancer via a microtubule-dependent mechanism. J Pathol. 2009;218:76–85. doi: 10.1002/path.2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Y, Nartiss Y, Steipe B, McQuibban GA, Kim PK. ROS-induced mitochondrial depolarization initiates PARK2/PARKIN-dependent mitochondrial degradation by autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8:1462–1476. doi: 10.4161/auto.21211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hochberg Y, Benjamini Y. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat Med. 1990;9:811–818. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gitig DM, Koff A. Cdk pathway: cyclin-dependent kinases and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. Mol Biotechnol. 2001;19:179–188. doi: 10.1385/MB:19:2:179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Magal SS, et al. Downregulation of Bax mRNA expression and protein stability by the E6 protein of human papillomavirus 16. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:611–621. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Hal NL, et al. The application of DNA microarrays in gene expression analysis. J Biotechnol. 2000;78:271–280. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(00)00204-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Minn AJ, et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to lung. Nature. 2005;436:518–524. doi: 10.1038/nature03799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Examples of PARK2 locus profiles from distinct cancer lineages. Copy number data from the TCGA. Representative types of malignancies are shown. SCNA profiles of chromosome 6 (left) and a 5Mb region surrounding PARK2 (right) are shown in the three lineages that had the highest frequency of PARK2 deletions: ovarian cancer (a), breast cancer (b), and bladder cancer (c).

Supplementary Figure 2. PARK2 regulates cell cycle progression. FACS data from three cell lines as indicated. Cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA control or with PARK2 siRNAs. DNA content and BrdU incorporation were measured after PARK2 knockdown. Representative results are shown from triplicate experiments.

Supplementary Figure 3. PARK2 knockdown results in alterations in gene expression. The indicated cells were treated with scrambled siRNA or PARK2 siRNA as shown. The heat map shows the top 50 genes with increased expression.

Supplementary Figure 4. Pathway analyses of 2,698 genes differentially expressed across 2 cell lines transfected with PARK2 siRNAs. Significant enrichment is shown in transcriptional programs governing cell growth, proliferation, protein ubiquitination, and cell cycle control.

Supplementary Figure 5. Gene expression does not change for cyclins D1 and E1 after PARK2 knockdown. Two independent PARK2 siRNAs were used. Experiments were repeated five times. Error bars, 1 standard deviation. NS, not significant.

Supplementary Figure 6. PARK2 knockdown causes accumulation of cyclin D2 and D3 protein. T202 cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA control or with PARK2 siRNAs and protein blots were performed with the antibodies specific for each cyclin type as indicated. Representative results are shown from triplicate experiments.

Supplementary Figure 7. Immunoprecipitation assays show binding of wild-type PARK2 to endogenous cyclins D2 and D3. HEK 293T cells were transfected with either vector only (pcDNA3.1) or with vector encoding wild-type PARK2. Assays were performed as described in Online Methods.

Supplementary Figure 8. Patterns of genetic alteration of FBXW7 and PARK2 in colorectal cancer. In colorectal cancer, FBXW7 is primarily mutated while PARK2 is deleted and mutated. Shown are data from The Cancer Genome Atlas Project (http://www.cbioportal.org/public-portal/). Point mutations are noted in green and deletions are noted in blue. Percentages denote total numbers of tumors with alterations in the gene. p, not significant.

Supplementary Table 1. Pan-cancer regions of significant SCNA and PARK2 anticorrelates.

Supplementary Table 2. Significance of PARK2 anticorrelates.

Supplementary Table 5. Quantitative RT-PCR Primer and siRNA target sequences.

Supplementary Table 3. Gene expression changes after PARK2 knockdown.

Supplementary Table 4. Pathway analyses based on genes differentially expressed after PARK2 knockdown.