Abstract

Dr. Conn originally reported an increased risk of diabetes in patients with hyperaldosteronism in the 1950’s, although the mechanism remains unclear. Aldosterone-induced hypokalemia was initially described to impair glucose tolerance by impairing insulin secretion. Correction of hypokalemia by potassium supplementation only partially restored insulin secretion and glucose tolerance, however. Aldosterone also impairs glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in isolated pancreatic islets via reactive oxygen species in a mineralocorticoid receptor-independent manner. Aldosterone-induced mineralocorticoid receptor activation also impairs insulin sensitivity in adipocytes and skeletal muscle. Aldosterone may produce insulin resistance secondarily by altering potassium, increasing inflammatory cytokines, and reducing beneficial adipokines such as adiponectin. Renin-angiotensin system antagonists reduce circulating aldosterone concentrations and also the risk of type 2 diabetes in clinical trials. These data suggest that primary and secondary hyperaldosteronism may contribute to worsening glucose tolerance by impairing insulin sensitivity or insulin secretion in humans. Future studies should define the effects of MR antagonists and aldosterone on insulin secretion and sensitivity in humans.

Keywords: Aldosterone, Mineralocorticoid receptor, Hypertension, Diabetes, Insulin Sensitivity, Insulin Secretion

1. INTRODUCTION

Since Dr. Conn’s initial description of hyperaldosteronism in the 1950’s, aldosterone excess has been associated with diabetes, although the mechanism remains unclear (1–3). Aldosterone-induced hypokalemia was initially described to impair glucose tolerance by impairing insulin secretion. Correction of hypokalemia by potassium supplementation only partially restored insulin secretion and glucose tolerance, however (1). Our group and others have demonstrated that aldosterone impairs glucose-stimulated insulin secretion directly via reactive oxygen species (4–6). Aldosterone-induced mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) activation also impairs insulin sensitivity in adipocytes and skeletal muscle (7). Furthermore, aldosterone is inappropriately increased in obese subjects (8–10), and fat-derived factors stimulate aldosterone secretion in vitro (11–13). Because obesity is the principal risk factor for development of type 2 diabetes (T2DM), obesity-related hyperaldosteronism may contribute to worsening glucose tolerance by impairing insulin sensitivity or insulin secretion.

Retrospective analysis of several large cardiovascular trials suggests that interrupting the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) prevents the occurrence of diabetes, with recent prospective trials supporting a beneficial effect on glucose metabolism. In the DREAM trial, the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor ramipril did not prevent the occurrence of diabetes, but improved fasting glycemia and 2-hour plasma glucose during glucose tolerance tests (14). In the NAVIGATOR trial, the angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) valsartan reduced the risk of diabetes by 14% in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance (15). The mechanism by which ACE inhibitors and ARBs reduce diabetes risk is largely unknown, although improvements in insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion have been implicated. These agents also decrease aldosterone and subsequent mineralocorticoid receptor activation, which could explain their beneficial effect on diabetes risk. We will briefly review the basic pathophysiology of diabetes and mechanisms by which aldosterone may alter glucose homeostasis.

2. INSULIN RESISTANCE AND INSULIN SECRETION IN THE PROGRESSION OF TYPE 2 DIABETES

2.1 Insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes

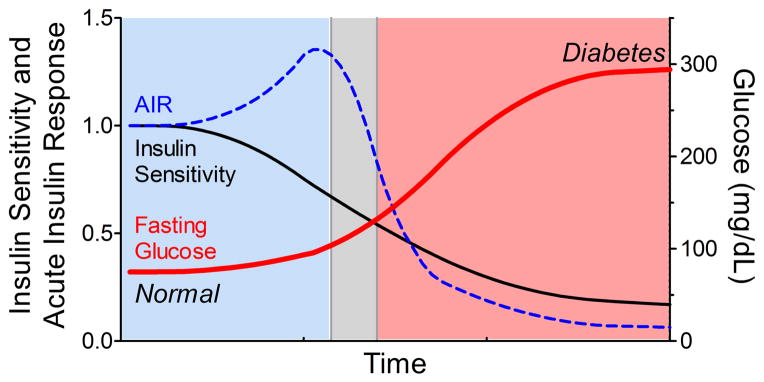

Development of insulin resistance is the hallmark of T2DM, although an inadequate insulin secretory response also contributes as detailed below (Figure 1) (16). Insulin stimulates glucose uptake in skeletal, hepatic, and adipose tissues, whereas glucose uptake in some tissues (e.g. brain) is primarily insulin-independent. Skeletal muscle accounts for the bulk of glucose disposal (~85%) during hyperinsulinemic clamps, and defective skeletal muscle glucose disposal accounts for the decrease in subjects with T2DM (17). Excess glucose release from gluconeogenic organs (i.e. the liver and to a lesser extent the kidney) also contributes to elevated fasting glucose in subjects with diabetes. Although insulin administration normally suppresses hepatic glucose production, insulin resistance blunts this hepatic response.

Figure 1.

Conceptualized time course of type 2 diabetes progression, relating insulin sensitivity (black line), acute insulin response (AIR, dashed blue line), and blood glucose (bold red line). Impaired insulin sensitivity occurs before detectable changes in glucose occur, which is compensated by an increase in insulin secretion (AIR) during normoglycemia (blue shading). However, an inappropriate decline in AIR coincides with development of impaired fasting glucose (gray shading) and eventual diabetes (red shading).

Hyperinsulinemia occurs in response to insulin-resistance in an attempt to maintain normal glucose homeostasis. Compared to insulin sensitive individuals, however, the degree of hyperinsulinemia may not adequately compensate for the severity of insulin resistance. In individuals with normal glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion are related in an inverse, non-linear manner resembling a hyperbola (18; 19). The product of the two measures, therefore remains constant in individuals with comparable glucose tolerance, but declines directly with impaired glucose tolerance (20; 21). Insulin secretion is impaired early in the pathogenesis of T2DM, and this inadequate insulin response is essential for the development of glucose intolerance and hyperglycemia (22; 23). This beta cell failure is reversible early in the course of disease, but is followed by progressive beta cell death mediated by glucotoxicity, lipotoxicity, and increased apoptosis (22). Better understanding of the environmental factors which affect insulin sensitivity and beta cell function is needed so that additional diabetes prevention strategies can be developed. Aldosterone or MR activation may contribute to these processes, and therefore serve as a potential drug target which already has proven cardiovascular benefits.

3. LINKS BETWEEN ALDOSTERONE, GLUCOSE TOLERANCE, AND INSULIN RESISTANCE

Obesity and hypertension are associated with peripheral insulin resistance, particularly in liver, skeletal muscle, and adipocytes. Insulin resistance is also associated with hypertension and has been independently linked to increased risk of cardiovascular complications, highlighting its importance (24–26). Elevated plasma aldosterone is associated with future development of hypertension, and primary hyperaldosteronism (PA) is the most frequently identifiable cause of secondary hypertension (27; 28). Furthermore, obesity is associated with increased circulating aldosterone levels (8–10), suggesting that aldosterone could be an important link between obesity and hypertension. In addition to Conn’s classic studies of diabetes in hyperaldosteronism, an aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2) -344C/C polymorphism, which has been associated with increased aldosterone, is also associated with development of metabolic syndrome and T2DM (29–32).

3.1 Clinical Studies of aldosterone on glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity

Studies suggest that aldosterone impairs insulin sensitivity in humans and in rodents via the mineralocorticoid receptor. Most clinical studies of aldosterone on insulin sensitivity reported estimates based on fasting glucose and insulin, or the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), which generally correlates with measures obtained during the more labor-intensive hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp studies (33; 34). In cross-sectional observational studies, plasma aldosterone is inversely associated with insulin sensitivity in normotensive and heart failure subjects using HOMA-IR (9; 35–39) and in essential hypertension subjects using hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps (40). Insulin sensitivity is also reduced in patients with primary aldosteronism compared to hypertensive controls in some (41–44), but not all studies (45–47). Elevated plasma aldosterone precedes and predicts the development of insulin resistance in humans after 10 years of follow-up, suggesting that the relative hyperaldosteronism could be causative (48). Further supporting this assertion, adrenalectomy (41; 46; 49) or medical therapy with an MR antagonist (44) improves insulin resistance in subjects with PA. Although adrenalectomy improved fasting glucose in patients with aldosterone producing adenomas (APAs), there was no improvement in oral glucose tolerance (49). Spironolactone administration also did not improve insulin sensitivity or glucose metabolism in a small group of subjects with idiopathic hyperaldosteronism (IHA), although these findings could be confounded by long follow-up times and weight gain (41; 42; 49). In a cohort of 9 APA subjects, adrenalectomy did not affect insulin sensitivity during hyperinsulinemic clamps but did increase serum potassium values and improve insulin secretory ability (47).

3.2 Cellular insulin signaling pathways which may be affected by mineralocorticoids

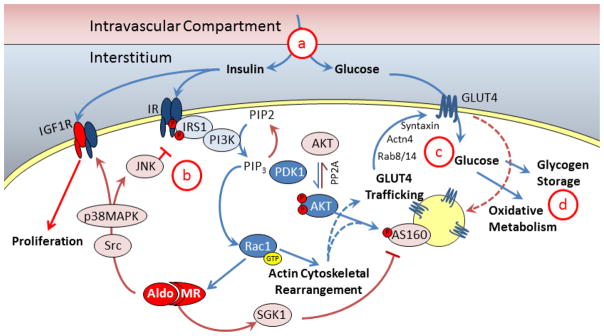

Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is caused by impairment at multiple steps in glucose/insulin delivery or in the insulin signaling pathways (Figure 2) (50). Adequate glucose and insulin delivery is determined by tissue perfusion and rapid nutrient diffusion from the vascular compartment through the interstitium to the cell membrane. In part, this process is dependent upon regulated transport of insulin across the vascular endothelium (51). Once glucose reaches the skeletal muscle cell, uptake is dependent on the cell membrane glucose transporter (primarily GLUT4) to facilitate diffusion into the cell. Once in skeletal muscle or adipose cells, glucose is phosphorylated by hexokinase to glucose-6-phosphate (G6P), which simultaneously increases the concentration gradient for glucose and directs glucose to either glycogenesis or oxidative metabolism. In gluconeogenic tissues such as the liver and kidney, however, G6P can be converted back to glucose and released into the circulation. Insulin receptor binding rapidly activates an intracellular signaling cascade resulting in generation of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate (PIP3), activation of AKT, and translocation of glucose transporter GLUT4 to the cell membrane. Activation of AKT is a focal point for downstream insulin signaling because it is required for maximal GLUT4 recruitment. Insulin also signals via AS160 and Rho/Rab family GTPases (e.g. Rac1) to alter cytoskeletal reorganization and direct GLUT4 trafficking to the cell membrane (52–54). Although additional downstream insulin receptor signaling pathways have also been identified, aldosterone has been implicated in the pathways as presented in Figure 2 and as discussed below. Aldosterone may also impair insulin sensitivity secondarily by affecting the production of other circulating factors such as adipokines and inflammatory cytokines.

Figure 2. Insulin signaling and glucose delivery.

Cellular insulin and glucose delivery is dependent on insulin transport and diffusion from the intravascular compartment, through the interstitium (a) to the cell membrane where insulin binds to the insulin receptor (IR) and glucose enters the cell via GLUT4. Insulin signaling is mediated by multiple pathways including IRS1, PI3K, and PDK1 which activate Akt (b). Akt and other pathways, e.g. Rac1, increase GLUT4 trafficking to the cell surface in part via actin cytoskeleton rearrangement. Glucose is taken into the cell and is converted to energy via oxidative metabolism or stored as glycogen for use in the future (d). Aldosterone and MR activation can affect multiple steps in the pathway by activating SGK1 or Src/MAPK/JNK pathways.

3.3 Role of aldosterone in vascular dysfunction, glucose, and insulin delivery (Figure 2a)

In healthy individuals, insulin and glucose administration produce vasodilation and increased capillary recruitment via increased nitric oxide production, which increases insulin and glucose delivery to target organs (51; 55; 56). This vasodilatory effect is impaired in obese or diabetic subjects (57). Excess aldosterone and MR activation adversely affects vascular function by reducing nitric oxide production and increasing reactive oxygen species, which produces endothelial dysfunction, vascular smooth muscle hypertrophy, and perivascular fibrosis and inflammation (58–60). Treatment with the mineralocorticoid deoxycorticosterone (DOCA) and salt reduces skeletal muscle capillary/fiber ratio and decreases terminal arteriole capillary vasodilation (61; 62). Aldosterone induces insulin resistance in isolated vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) by reducing IRS1 expression and downstream Akt signaling (63; 64). Aldosterone acts via the MR and Src-kinase activation to increase the expression of VSMC insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF1R), which can form a hybrid IR/IGF1R receptor which preferentially activates MAP-kinase pathways to promote vascular hypertrophy (65; 66). The vascular smooth muscle MR contributes to vasoconstrictor response and hypertension with ageing, demonstrating that aldosterone-MR activation has direct vascular effects independent of its renal effects (58; 67; 68). The extracellular matrix also affects angiogenesis and glucose diffusion which may also contribute to insulin resistance more than previously appreciated (69; 70). Aldosterone-salt excess consistently induces perivascular fibrosis and inflammation (71), which may indirectly contribute to insulin resistance in vivo by impairing glucose diffusion. Therefore, beneficial effects of MR antagonism on insulin sensitivity could be explained by improved vascular density or function, independent of renal MR and electrolyte changes (64).

3.4 Effect of aldosterone on insulin receptor activation and immediate downstream pathways in skeletal muscle and adipocytes (Figure 2b)

Skeletal muscle is the primary insulin-sensitive target, accounting for nearly 85% of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake under experimental conditions, with adipose tissue contributing a much smaller amount (17). Systemic aldosterone-salt administration to Wistar rats reduces skeletal muscle glucose uptake, associated with decreased IR, insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS1), and AKT expression and phosphorylation (72; 73). Aldosterone administration in fructose-fed rats also increases skeletal muscle expression of serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 (SGK1), a kinase typically affected by MR activation, suggesting that aldosterone may act via the MR directly in skeletal muscle (74). In a rat model with secondary hyperaldosteronism and insulin resistance (the Ren2 rat), MR antagonism improves insulin sensitivity and insulin receptor signaling, as assessed by ex vivo skeletal muscle glucose uptake, AKT and IRS1 phosphorylation, which is associated with decreased NADPH oxidase activity and reactive oxygen species (75). Although the aldosterone-sensitive pathways within VSMC have been clearly defined, further studies in skeletal muscle are needed. Aldosterone-induced skeletal muscle effects could alternatively be dependent on renal or adipocyte MR activation, which could alter electrolyte balance or adipokine production, respectively.

Some studies have utilized potassium supplementation to prevent significant hypokalemia, although a contribution of potassium depletion in the absence of altered serum potassium cannot be excluded. In particular, renal potassium loss may confound interpretation of in vivo studies by worsening insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion. The development of tissue-specific MR knockout mice promises to yield further insights into extra-renal MR effects. Evidence supports the hypothesis that aldosterone and the MR directly affect skeletal muscle metabolism, in particular by increasing intracellular potassium transport in chronic adaptation to high potassium diet (76–78). This effect can be reproduced by other mineralocorticoids such as deoxycorticosterone (DOCA) but not by glucocorticoids, and can be reversed by spironolactone, suggesting that it is MR-dependent (78). The effects of insulin on glucose and potassium are not necessarily directly linked. For example, the intracellular potassium shift produced by insulin is more sensitive and longer lasting than the glucose uptake response, and occurs even in the absence of glucose (79; 80). Further studies investigating aldosterone’s effect on skeletal muscle potassium and glucose insulin resistance are warranted.

Aldosterone also impairs insulin sensitivity directly in adipocytes. Aldosterone impairs glucose uptake in vitro in 3T3 adipocytes and is associated with reduced GLUT4 cell surface localization, and IRS1, P13K, and AKT phosphorylation (81; 82). Aldosterone may also impair insulin sensitivity by impairing normal adipocyte differentiation and function. Aldosterone induces pre-adipocyte differentiation in vitro via the MR (83). Adiponectin is the best-characterized adipose-derived circulating hormone, or adipokine, which improves insulin sensitivity (84). In genetically obese and diabetic mice, MR antagonism increases adipocyte peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-gamma and adiponectin expression, reduces tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha and monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1 expression, and improves insulin sensitivity in vivo (85–87). Aldosterone excess is also associated with reduced circulating adiponectin (88) and visceral adipose adiponectin expression in subjects with APA (87). Some studies argue against a direct adipose tissue affect, however, because aldosterone only impaired insulin signaling at concentrations which activate the glucocorticoid receptor (89). In the setting of diet-induced obesity, genetic aldosterone deficiency reduced adipocyte inflammation and increased circulating adiponectin, although this did not prevent development of obesity or insulin resistance, suggesting that mineralocorticoids other than aldosterone may contribute to insulin resistance in vivo (90).

3.5 Effect of aldosterone on cytoskeletal rearrangement and GLUT4 translocation (Figure 2c)

Aldosterone primarily stimulates translocation of sodium channels and transporters to the cell surface in the distal nephron segments via MR-dependent mechanisms, which shares similar regulatory proteins with Rho/Rab GTPase-regulated transport of GLUT4. In renal epithelial cells, aldosterone-induced AS160 phosphorylation by SGK1 regulates epithelial sodium (ENaC) cell-surface localization (91). In skeletal muscle, aldosterone administration also increases SGK1, which can phosphorylate multiple AS160 sites, but not the Ser341 site essential for 14-3-3 binding and maximal GLUT4 translocation (74; 92; 93). In skeletal muscle, aldosterone administration impairs AS160(Thr642) phosphorylation, GLUT4 expression, and glucose oxidation in vivo in a dose-dependent manner (72; 73). A definitive role of aldosterone-induced SKG1 phosphorylation of AS160 in skeletal muscle has not been definitely established, however.

Once glucose enters skeletal muscle, it enters either the glycolytic or glycogenic pathway, both of which are impaired in early T2DM and insulin resistance. The effect of aldosterone on oxidative versus glycogenic pathways has not been clearly defined, although aldosterone administration reduces skeletal muscle and hepatic glycogen content in Wistar rats (72; 73). This effect could be a consequence of reduced glucose entry into the cell, rather than a primary effect on these metabolic pathways.

3.5 Effect of aldosterone on hepatic glucose production and fatty liver

In the fasting state, the liver and kidney maintain circulating glucose within a tight range by releasing glucose from glycogen (glycogenolysis) or by converting precursor molecules to glucose (gluconeogenesis). The liver is the major source of circulating glucose in the fasted state, and therefore most studies of aldosterone have been performed in cultured hepatocytes to examine the effects on gluconeogenesis. Gluconeogenic organs express glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase), which converts G6P to glucose, which can then be released into the circulation. The MR is expressed in rat liver and hepatoma cell lines, although at a lower level than in heart or hippocampus (94; 95). Aldosterone increases expression of G6Pase and the essential gluconeogenic enzymes fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase in vitro (96; 97). Some of the effects of aldosterone only occurred at micromolar concentrations, however, raising the possibility that they may be nonspecific or physiologically irrelevant. Furthermore, aldosterone blunts the inhibitory effect of insulin within this system, and a single dose of aldosterone elevates fasting blood glucose in mice, suggesting that aldosterone increases hepatic glucose production (96). This effect of aldosterone on G6Pase increases further when given in micro-molar concentrations and is blocked by glucocorticoid receptor antagonist RU486 but not MR antagonists suggesting that this effect may only occur at supraphysiologic concentrations via glucocorticoid receptor activation (96). In contrast, Liu et al found that MR antagonism or siRNA treatment decreases G6Pase expression (97). The effect of aldosterone on hepatic glucose production in humans has not been assessed, although this is possible with the use of tracer methodologies.

In the setting of severe hepatic insulin resistance, liver fat accumulates and contributes to hepatic insulin resistance and dyslipidemia. In high fat-, fructose-fed, and genetic models of obesity, MR antagonism ameliorates fatty liver disease with reduction in histologic injury and hepatic triglyceride content (98–100). we similarly observed that aldosterone synthase deficiency ameliorates high fat diet-induced fatty liver histology and hepatic triglyceride content (90). On the other hand, one study found no effect of adrenalectomy or MR antagonism on fatty liver severity (101). Data in humans is limited, but fatty liver disease has been associated with plasma aldosterone, low potassium, and insulin resistance in a cohort of patients with APA (102).

4. EFFECT OF ALDOSTERONE ON INSULIN SECRETION

Conn originally implicated hypokalemia and insulin secretion in the pathogenesis of hyperaldosteronism-induced T2DM, although correction of hypokalemia only partially corrected the insulin secretory defect (1). Studies in rodents also demonstrate a reduced insulin secretion after systemic aldosterone or DOCA-salt administration in Wistar rats (103). In aldosterone deficient mice, glucose-stimulated insulin secretion is markedly increased during normal, high sodium, and high fat diets without any alteration in islet density, suggesting that endogenous aldosterone impairs insulin secretion by directly altering islet function (5; 90). This effect occurs without altered insulin sensitivity and after elevated serum potassium is normalized by high sodium diet, suggesting that endogenous aldosterone directly decreases insulin secretion in pancreatic islets. Furthermore, aldosterone impairs glucose-stimulated insulin secretion within either isolated murine or rat islets or the clonal beta cell MIN6 line, systems which are independent of potassium (4–6). Pancreatic islet MR expression is localized to delta and PP cells, although their physiologic relevance is uncertain and expression in other islet cell types cannot be excluded (5; 104). The inhibitory aldosterone effect on insulin secretion was not prevented by available MR antagonists spironolactone, eplerenone, or RU-28318 (5), but was reversed by either the superoxide dismutase mimetic tempol (5) or the reactive oxygen species scavenger N-acetylcysteine (4).

A relatively recent finding in the aldosterone field has been the identification of GPR30 as a membrane receptor for aldosterone which may mediate rapid actions of aldosterone (105–107). Interestingly, GPR30 activation mediates pregnancy- and estrogen-induced beta cell proliferation by down-regulating the micro RNA miR-338-3p (108). Estrogen induced GPR30 activation also potentiates insulin secretion in murine islets (109; 110). Therefore, the known effects of GPR30 activation within islets do not appear to explain the actions of aldosterone on insulin secretion. This field of aldosterone-GPR30 signaling remains in its infancy, and additional membrane receptors could be identified in the future to shed light on these findings (106; 111).

Studies also suggest that aldosterone impairs insulin secretion in humans. In Conn’s classic studies, he demonstrated that 14/27 (52%) of patients with PA exhibited impaired glucose tolerance and an impaired insulin response after oral glucose administration (1). More recently investigators estimated beta cell function using fasting glucose and insulin concentrations and noted a decrease in HOMA2-β and fasting C-peptide in patients with APA versus essential hypertension (112). Fischer et al demonstrated impaired acute glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in patients with APA versus essential hypertension using frequently-sampled intravenous glucose tolerance tests, which improved after adrenalectomy (47). Shimamoto also observed impaired glucose tolerance and insulin secretion in APA subjects and normalization after adrenalectomy which correlated strongly with potassium, although insulin sensitivity was increased as well (113). Taken together, these studies suggest that aldosterone may primarily affect insulin secretion. These studies were potentially confounded by significant differences in potassium or blood pressure, however. Further studies which more closely match these variables could exclude such an effect, although this is difficult to accomplish in clinical practice. The effect of MR blockade on insulin secretion has not been formally investigated and requires further study.

Additional clinical evidence supports an effect of the RAAS on insulin secretion in humans. As mentioned above several retrospective studies and two large prospective, randomized placebo controlled trials demonstrate that ACE inhibitors or ARBs improve glucose homeostasis and reduce the incidence of T2DMin subjects at high risk of cardiovascular events (14; 15; 114). AngII activation of AngII type I receptor (AT1) is a potent stimulus for aldosterone secretion, and both ACE inhibitors and ARBs reduce plasma aldosterone concentrations clinically. During thiazide treatment in hypertensive subjects, the ARB azilsartan preserved glucose tolerance compared to amlodipine treatment, which appears to have been mediated by preservation of the insulin secretory response (115). In a separate study, valsartan improved both insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity, assessed by hyperglycemic clamps and hyperinsulinemic clamps, respectively (116). Although aldosterone reduction could contribute to the beneficial effects of RAAS blockade, the relationship between aldosterone and insulin secretion was not assessed in these studies and also requires further investigation.

5. CLINICAL AND THERAPEUTIC IMPLICATIONS

Aldosterone is inappropriately elevated in 10–15% of patients with resistant hypertension, and contributes significantly to cardiovascular disease. Autonomous, AngII-independent aldosterone secretion is classified as primary hyperaldosteronism (PA). Most commonly this is due to either an aldosterone producing adenoma (APA) or idiopathic hyperaldosteronism (IHA). Treatment with an MR antagonist improves hypertension control and prevents hypokalemia, although it commonly produces a compensatory increase in plasma aldosterone concentrations (117). Based on the above data, this would be predicted to improve insulin sensitivity due to MR antagonism in muscle, adipocytes, and liver, or via secondary effects on circulating adipokines, cytokines, and electrolytes. Treatment with MR antagonists could also worsen insulin secretion due to the compensatory increase in plasma aldosterone. Along these lines, spironolactone worsened glycemic control compared to placebo in a group of diabetic subjects with poorly controlled hypertension (118). Further studies are needed to determine the net effect of MR antagonism on insulin secretion and insulin resistance in humans at risk for diabetes before drawing firm conclusions. Aldosterone synthase inhibitors, which are currently in development for human use, may provide an alternative strategy to treat hyperaldosteronism which could have favorable metabolic effects compared to MR antagonists or diuretics.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Aldosterone excess is associated with obesity, hypertension, and diabetes.

Renin-angiotensin system antagonists reduce aldosterone concentrations and diabetes risk.

Aldosterone reduces insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle and adipocytes.

Aldosterone impairs insulin secretion in isolated islets and patients with hyperaldosteronism.

Hypertension treatment may worsen glucose tolerance by increasing aldosterone.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grants DK081662 and DK096994 (J.M.L.).

Abbreviations

- ACE

Angiotensin converting enzyme

- AKT

also known as protein kinase B

- APA

Aldosterone-producing adenoma

- ARB

Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker

- As

Aldosterone synthase

- DOCA

Deoxycorticosterone acetate

- G6P

Glucose-6-phosphate

- G6Pase

Glucose-6-phosphatase

- GLUT4

Glucose transporter type 4

- HOMA-IR

Homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance

- IGF1

Insulin-like growth factor-I

- IGF1R

Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor

- IHA

Idiopathic hyperaldosteronism

- IRS1

Insulin receptor substrate 1

- MR

Mineralocorticoid receptor

- PA

Primary aldosteronism

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate 3-kinase

- PIP3

Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate

- SGK1

Serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- VSMC

Vascular smooth muscle cells

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to declare

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Conn JW. Hypertension, the potassium ion and impaired carbohydrate tolerance. N Engl J Med. 1965;273:1135–1143. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196511182732106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conn JW, Knopf RF, Nesbit RM. Clinical characteristics of primary aldosteronism from an analysis of 145 cases. Am J Surg. 1964;107:159–172. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(64)90252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Diabetes A: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Suppl 1):S67–74. doi: 10.2337/dc13-S067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin HM, Zhou DC, Gu HF, Qiao QY, Fu SK, Liu XL, Pan Y. Antioxidant N-acetylcysteine protects pancreatic beta-cells against aldosterone-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in female db/db mice and insulin-producing MIN6 cells. Endocrinology. 2013;154:4068–4077. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luther JM, Luo P, Kreger MT, Brissova M, Dai C, Whitfield TT, Kim HS, Wasserman DH, Powers AC, Brown NJ. Aldosterone decreases glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in vivo in mice and in murine islets. Diabetologia. 2011;54:2152–2163. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2158-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pierluissi J, Navas FO, Ashcroft SJ. Effect of adrenal steroids on insulin release from cultured rat islets of Langerhans. Diabetologia. 1986;29:119–121. doi: 10.1007/BF00456122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sowers JR, Whaley-Connell A, Epstein M. Narrative review: the emerging clinical implications of the role of aldosterone in the metabolic syndrome and resistant hypertension. AnnInternMed. 2009;150:776–783. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-11-200906020-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuck ML, Sowers J, Dornfeld L, Kledzik G, Maxwell M. The effect of weight reduction on blood pressure, plasma renin activity, and plasma aldosterone levels in obese patients. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:930–933. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198104163041602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodfriend TL, Egan BM, Kelley DE. Plasma aldosterone, plasma lipoproteins, obesity and insulin resistance in humans. Prostaglandins LeukotEssentFatty Acids. 1999;60:401–405. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(99)80020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bentley-Lewis R, Adler GK, Perlstein T, Seely EW, Hopkins PN, Williams GH, Garg R. Body mass index predicts aldosterone production in normotensive adults on a high-salt diet. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4472–4475. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehrhart-Bornstein M, Lamounier-Zepter V, Schraven A, Langenbach J, Willenberg HS, Barthel A, Hauner H, McCann SM, Scherbaum WA, Bornstein SR. Human adipocytes secrete mineralocorticoid-releasing factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14211–14216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336140100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodfriend TL, Ball DL, Egan BM, Campbell WB, Nithipatikom K. Epoxy-keto derivative of linoleic acid stimulates aldosterone secretion. Hypertension. 2004;43:358–363. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000113294.06704.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagase M, Yoshida S, Shibata S, Nagase T, Gotoda T, Ando K, Fujita T. Enhanced aldosterone signaling in the early nephropathy of rats with metabolic syndrome: possible contribution of fat-derived factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:3438–3446. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Investigators DT, Bosch J, Yusuf S, Gerstein HC, Pogue J, Sheridan P, Dagenais G, Diaz R, Avezum A, Lanas F, Probstfield J, Fodor G, Holman RR. Effect of ramipril on the incidence of diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1551–1562. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Group NS, McMurray JJ, Holman RR, Haffner SM, Bethel MA, Holzhauer B, Hua TA, Belenkov Y, Boolell M, Buse JB, Buckley BM, Chacra AR, Chiang FT, Charbonnel B, Chow CC, Davies MJ, Deedwania P, Diem P, Einhorn D, Fonseca V, Fulcher GR, Gaciong Z, Gaztambide S, Giles T, Horton E, Ilkova H, Jenssen T, Kahn SE, Krum H, Laakso M, Leiter LA, Levitt NS, Mareev V, Martinez F, Masson C, Mazzone T, Meaney E, Nesto R, Pan C, Prager R, Raptis SA, Rutten GE, Sandstroem H, Schaper F, Scheen A, Schmitz O, Sinay I, Soska V, Stender S, Tamas G, Tognoni G, Tuomilehto J, Villamil AS, Vozar J, Califf RM. Effect of valsartan on the incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1477–1490. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weyer C, Bogardus C, Mott DM, Pratley RE. The natural history of insulin secretory dysfunction and insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:787–794. doi: 10.1172/JCI7231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeFronzo RA. Lilly lecture 1987. The triumvirate: beta-cell, muscle, liver. A collusion responsible for NIDDM. Diabetes. 1988;37:667–687. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.6.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahren B, Pacini G. Importance of quantifying insulin secretion in relation to insulin sensitivity to accurately assess beta cell function in clinical studies. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;150:97–104. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1500097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahn SE, Prigeon RL, McCulloch DK, Boyko EJ, Bergman RN, Schwartz MW, Neifing JL, Ward WK, Beard JC, Palmer JP. Quantification of the relationship between insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function in human subjects. Evidence for a hyperbolic function. Diabetes. 1993;42:1663–1672. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.11.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gastaldelli A, Ferrannini E, Miyazaki Y, Matsuda M, Defronzo RA. Beta-cell dysfunction and glucose intolerance: results from the San Antonio metabolism (SAM) study. Diabetologia. 2004;47:31–39. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1263-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergman RN, Phillips LS, Cobelli C. Physiologic evaluation of factors controlling glucose tolerance in man: measurement of insulin sensitivity and beta-cell glucose sensitivity from the response to intravenous glucose. J Clin Invest. 1981;68:1456–1467. doi: 10.1172/JCI110398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhodes CJ. Type 2 diabetes-a matter of beta-cell life and death? Science. 2005;307:380–384. doi: 10.1126/science.1104345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kahn SE, Hull RL, Utzschneider KM. Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2006;444:840–846. doi: 10.1038/nature05482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pande RL, Perlstein TS, Beckman JA, Creager MA. Association of insulin resistance and inflammation with peripheral arterial disease: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 to 2004. Circulation. 2008;118:33–41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.721878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abbasi F, Brown BW, Jr, Lamendola C, McLaughlin T, Reaven GM. Relationship between obesity, insulin resistance, and coronary heart disease risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:937–943. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pyorala M, Miettinen H, Halonen P, Laakso M, Pyorala K. Insulin resistance syndrome predicts the risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in healthy middle-aged men: the 22-year follow-up results of the Helsinki Policemen Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:538–544. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.2.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vasan RS, Evans JC, Larson MG, Wilson PW, Meigs JB, Rifai N, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Serum aldosterone and the incidence of hypertension in nonhypertensive persons. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:33–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calhoun DA. Is there an unrecognized epidemic of primary aldosteronism? Pro Hypertension. 2007;50:447–453. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.086116. discussion 447–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bellili NM, Foucan L, Fumeron F, Mohammedi K, Travert F, Roussel R, Balkau B, Tichet J, Marre M. Associations of the -344 T>C and the 3097 G>A polymorphisms of CYP11B2 gene with hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome in a French population. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:660–667. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ranade K, Wu KD, Risch N, Olivier M, Pei D, Hsiao CF, Chuang LM, Ho LT, Jorgenson E, Pesich R, Chen YD, Dzau V, Lin A, Olshen RA, Curb D, Cox DR, Botstein D. Genetic variation in aldosterone synthase predicts plasma glucose levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13219–13224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221467098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russo P, Lauria F, Loguercio M, Barba G, Arnout J, Cappuccio FP, de LM, Donati MB, Iacoviello L, Krogh V, van DM, Siani A. -344C/T Variant in the promoter of the aldosterone synthase gene (CYP11B2) is associated with metabolic syndrome in men. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:218–222. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pojoga L, Gautier S, Blanc H, Guyene TT, Poirier O, Cambien F, Benetos A. Genetic determination of plasma aldosterone levels in essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 1998;11:856–860. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(98)00048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1487–1495. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freel EM, Tsorlalis IK, Lewsey JD, Latini R, Maggioni AP, Solomon S, Pitt B, Connell JM, McMurray JJ. Aldosterone status associated with insulin resistance in patients with heart failure--data from the ALOFT study. Heart. 2009;95:1920–1924. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.173344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodfriend TL, Kelley DE, Goodpaster BH, Winters SJ. Visceral obesity and insulin resistance are associated with plasma aldosterone levels in women. Obes Res. 1999;7:355–362. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1999.tb00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huan Y, Deloach S, Keith SW, Goodfriend TL, Falkner B. Aldosterone and aldosterone: renin ratio associations with insulin resistance and blood pressure in African Americans. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2012;6:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kidambi S, Kotchen JM, Grim CE, Raff H, Mao J, Singh RJ, Kotchen TA. Association of adrenal steroids with hypertension and the metabolic syndrome in blacks. Hypertension. 2007;49:704–711. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000253258.36141.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kidambi S, Kotchen JM, Krishnaswami S, Grim CE, Kotchen TA. Hypertension, insulin resistance, and aldosterone: sex-specific relationships. J Clin Hypertens(Greenwich) 2009;11:130–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00084.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Colussi G, Catena C, Lapenna R, Nadalini E, Chiuch A, Sechi LA. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia are related to plasma aldosterone levels in hypertensive patients. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2349–2354. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giacchetti G, Ronconi V, Turchi F, Agostinelli L, Mantero F, Rilli S, Boscaro M. Aldosterone as a key mediator of the cardiometabolic syndrome in primary aldosteronism: an observational study. J Hypertens. 2007;25:177–186. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3280108e6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sindelka G, Widimsky J, Haas T, Prazny M, Hilgertova J, Skrha J. Insulin action in primary hyperaldosteronism before and after surgical or pharmacological treatment. Exp Clin Endocr Diab. 2000;108:21–25. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1329211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Widimsky J, Jr, Sindelka G, Haas T, Prazny M, Hilgertova J, Skrha J. Impaired insulin action in primary hyperaldosteronism. Physiol Res. 2000;49:241–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Catena C, Lapenna R, Baroselli S, Nadalini E, Colussi G, Novello M, Favret G, Melis A, Cavarape A, Sechi LA. Insulin sensitivity in patients with primary aldosteronism: a follow-up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3457–3463. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ishimori M, Takeda N, Okumura S, Murai T, Inouye H, Yasuda K. Increased insulin sensitivity in patients with aldosterone producing adenoma. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1994;41:433–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1994.tb02573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Widimsky J, Jr, Strauch B, Sindelka G, Skrha J. Can primary hyperaldosteronism be considered as a specific form of diabetes mellitus? Physiol Res. 2001;50:603–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fischer E, Adolf C, Pallauf A, Then C, Bidlingmaier M, Beuschlein F, Seissler J, Reincke M. Aldosterone excess impairs first phase insulin secretion in primary aldosteronism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2513–2520. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumagai E, Adachi H, Jacobs DR, Jr, Hirai Y, Enomoto M, Fukami A, Otsuka M, Kumagae S, Nanjo Y, Yoshikawa K, Esaki E, Yokoi K, Ogata K, Kasahara A, Tsukagawa E, Ohbu-Murayama K, Imaizumi T. Plasma aldosterone levels and development of insulin resistance: prospective study in a general population. Hypertension. 2011;58:1043–1048. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.180521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strauch B, Widimsky J, Sindelka G, Skrha J. Does the treatment of primary hyperaldosteronism influence glucose tolerance? Physiol Res. 2003;52:503–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Samuel VT, Shulman GI. Mechanisms for insulin resistance: common threads and missing links. Cell. 2012;148:852–871. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barrett EJ, Eggleston EM, Inyard AC, Wang H, Li G, Chai W, Liu Z. The vascular actions of insulin control its delivery to muscle and regulate the rate-limiting step in skeletal muscle insulin action. Diabetologia. 2009;52:752–764. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1313-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leto D, Saltiel AR. Regulation of glucose transport by insulin: traffic control of GLUT4. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:383–396. doi: 10.1038/nrm3351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bogan JS. Regulation of glucose transporter translocation in health and diabetes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:507–532. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060109-094246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chiu TT, Jensen TE, Sylow L, Richter EA, Klip A. Rac1 signalling towards GLUT4/glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. Cell Signal. 2011;23:1546–1554. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mather KJ, Steinberg HO, Baron AD. Insulin resistance in the vasculature. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1003–1004. doi: 10.1172/JCI67166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baron AD, Steinberg HO, Chaker H, Leaming R, Johnson A, Brechtel G. Insulin-mediated skeletal muscle vasodilation contributes to both insulin sensitivity and responsiveness in lean humans. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:786–792. doi: 10.1172/JCI118124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baron AD. The coupling of glucose metabolism and perfusion in human skeletal muscle. The potential role of endothelium-derived nitric oxide. Diabetes. 1996;45 (Suppl 1):S105–109. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.1.s105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCurley A, Pires PW, Bender SB, Aronovitz M, Zhao MJ, Metzger D, Chambon P, Hill MA, Dorrance AM, Mendelsohn ME, Jaffe IZ. Direct regulation of blood pressure by smooth muscle cell mineralocorticoid receptors. Nat Med. 2012;18:1429–1433. doi: 10.1038/nm.2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pruthi D, McCurley A, Aronovitz M, Galayda C, Karumanchi SA, Jaffe IZ. Aldosterone promotes vascular remodeling by direct effects on smooth muscle cell mineralocorticoid receptors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:355–364. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Luther JM, Luo P, Wang Z, Cohen SE, Kim HS, Fogo AB, Brown NJ. Aldosterone deficiency and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism prevent angiotensin II-induced cardiac, renal, and vascular injury. Kidney Int. 2012;82:643–651. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hernandez N, Torres SH, Finol HJ, Sosa A, Cierco M. Capillary and muscle fiber type changes in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Anat Rec. 1996;246:208–216. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199610)246:2<208::AID-AR7>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Losada M, Torres SH, Hernandez N, Lippo M, Sosa A. Muscle arteriolar and venular reactivity in two models of hypertensive rats. Microvasc Res. 2005;69:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hitomi H, Kiyomoto H, Nishiyama A, Hara T, Moriwaki K, Kaifu K, Ihara G, Fujita Y, Ugawa T, Kohno M. Aldosterone suppresses insulin signaling via the downregulation of insulin receptor substrate-1 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension. 2007;50:750–755. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.093955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bender SB, McGraw AP, Jaffe IZ, Sowers JR. Mineralocorticoid receptor-mediated vascular insulin resistance: an early contributor to diabetes-related vascular disease? Diabetes. 2013;62:313–319. doi: 10.2337/db12-0905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sherajee SJ, Fujita Y, Rafiq K, Nakano D, Mori H, Masaki T, Hara T, Kohno M, Nishiyama A, Hitomi H. Aldosterone induces vascular insulin resistance by increasing insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor and hybrid receptor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:257–263. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.240697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cascella T, Radhakrishnan Y, Maile LA, Busby WH, Jr, Gollahon K, Colao A, Clemmons DR. Aldosterone enhances IGF-I-mediated signaling and biological function in vascular smooth muscle cells. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5851–5864. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Galmiche G, Pizard A, Gueret A, El Moghrabi S, Ouvrard-Pascaud A, Berger S, Challande P, Jaffe IZ, Labat C, Lacolley P, Jaisser F. Smooth muscle cell mineralocorticoid receptors are mandatory for aldosterone-salt to induce vascular stiffness. Hypertension. 2014;63:520–526. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dupont JJ, Hill MA, Bender SB, Jaisser F, Jaffe IZ. Aldosterone and vascular mineralocorticoid receptors: regulators of ion channels beyond the kidney. Hypertension. 2014;63:632–637. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wasserman DH. Four grams of glucose. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E11–21. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90563.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kang L, Lantier L, Kennedy A, Bonner JS, Mayes WH, Bracy DP, Bookbinder LH, Hasty AH, Thompson CB, Wasserman DH. Hyaluronan accumulates with high-fat feeding and contributes to insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2013;62:1888–1896. doi: 10.2337/db12-1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rocha R, Martin-Berger CL, Yang P, Scherrer R, Delyani J, McMahon E. Selective aldosterone blockade prevents angiotensin II/salt-induced vascular inflammation in the rat heart. Endocrinology. 2002;143:4828–4836. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Selvaraj J, Muthusamy T, Srinivasan C, Balasubramanian K. Impact of excess aldosterone on glucose homeostasis in adult male rat. Clin ChimActa. 2009;407:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Selvaraj J, Sathish S, Mayilvanan C, Balasubramanian K. Excess aldosterone-induced changes in insulin signaling molecules and glucose oxidation in gastrocnemius muscle of adult male rat. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;372:113–126. doi: 10.1007/s11010-012-1452-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sherajee SJ, Rafiq K, Nakano D, Mori H, Kobara H, Hitomi H, Fujisawa Y, Kobori H, Masaki T, Nishiyama A. Aldosterone aggravates glucose intolerance induced by high fructose. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;720:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lastra G, Whaley-Connell A, Manrique C, Habibi J, Gutweiler AA, Appesh L, Hayden MR, Wei Y, Ferrario C, Sowers JR. Low-dose spironolactone reduces reactive oxygen species generation and improves insulin-stimulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle in the TG(mRen2)27 rat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E110–E116. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00258.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Alexander EA, Levinsky NG. An extrarenal mechanism of potassium adaptation. J Clin Invest. 1968;47:740–748. doi: 10.1172/JCI105769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Adler S. An extrarenal action of aldosterone on mammalian skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. 1970;218:616–621. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1970.218.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Goldfarb S, Cox M, Singer I, Goldberg M. Acute hyperkalemia induced by hyperglycemia: hormonal mechanisms. Ann Intern Med. 1976;84:426–432. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-84-4-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zierler KL, Rabinowitz D. Effect of Very Small Concentrations of Insulin on Forearm Metabolism. Persistence of Its Action on Potassium and Free Fatty Acids without Its Effect on Glucose. J Clin Invest. 1964;43:950–962. doi: 10.1172/JCI104981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zierler KL. Effect of insulin on potassium efflux from rat muscle in the presence and absence of glucose. Am J Physiol. 1960;198:1066–1070. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1960.198.5.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wada T, Ohshima S, Fujisawa E, Koya D, Tsuneki H, Sasaoka T. Aldosterone inhibits insulin-induced glucose uptake by degradation of insulin receptor substrate (IRS) 1 and IRS2 via a reactive oxygen species-mediated pathway in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1662–1669. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li P, Zhang XN, Pan CM, Sun F, Zhu DL, Song HD, Chen MD. Aldosterone perturbs adiponectin and PAI-1 expression and secretion in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. HormMetab Res. 2011;43:464–469. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1277226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Caprio M, Feve B, Claes A, Viengchareun S, Lombes M, Zennaro MC. Pivotal role of the mineralocorticoid receptor in corticosteroid-induced adipogenesis. FASEB J. 2007;21:2185–2194. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7970com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Turer AT, Scherer PE. Adiponectin: mechanistic insights and clinical implications. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2319–2326. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2598-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Guo C, Ricchiuti V, Lian BQ, Yao TM, Coutinho P, Romero JR, Li J, Williams GH, Adler GK. Mineralocorticoid receptor blockade reverses obesity-related changes in expression of adiponectin, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma, and proinflammatory adipokines. Circulation. 2008;117:2253–2261. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.748640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hirata A, Maeda N, Hiuge A, Hibuse T, Fujita K, Okada T, Kihara S, Funahashi T, Shimomura I. Blockade of mineralocorticoid receptor reverses adipocyte dysfunction and insulin resistance in obese mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;84:164–172. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Williams TA, Monticone S, Urbanet R, Bertello C, Giraudo G, Vettor R, Fallo F, Veglio F, Mulatero P. Genes implicated in insulin resistance are down-regulated in primary aldosteronism patients. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;355:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fallo F, Della Mea P, Sonino N, Bertello C, Ermani M, Vettor R, Veglio F, Mulatero P. Adiponectin and insulin sensitivity in primary aldosteronism. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:855–861. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Urbanet R, Pilon C, Calcagno A, Peschechera A, Hubert EL, Giacchetti G, Gomez-Sanchez C, Mulatero P, Toffanin M, Sonino N, Zennaro MC, Giorgino F, Vettor R, Fallo F. Analysis of insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue of patients with primary aldosteronism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4037–4042. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Luo P, Dematteo A, Wang Z, Zhu L, Wang A, Kim HS, Pozzi A, Stafford JM, Luther JM. Aldosterone deficiency prevents high-fat-feeding-induced hyperglycaemia and adipocyte dysfunction in mice. Diabetologia. 2013;56:901–910. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2814-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liang X, Butterworth MB, Peters KW, Frizzell RA. AS160 modulates aldosterone-stimulated epithelial sodium channel forward trafficking. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2024–2033. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-01-0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Geraghty KM, Chen S, Harthill JE, Ibrahim AF, Toth R, Morrice NA, Vandermoere F, Moorhead GB, Hardie DG, MacKintosh C. Regulation of multisite phosphorylation and 14-3-3 binding of AS160 in response to IGF-1, EGF, PMA and AICAR. Biochem J. 2007;407:231–241. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen S, Synowsky S, Tinti M, MacKintosh C. The capture of phosphoproteins by 14-3-3 proteins mediates actions of insulin. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2011;22:429–436. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zaini A, Pearce P, Funder JW. High-affinity aldosterone binding in rat liver--a re-evaluation. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1987;14:39–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1987.tb00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Reul JM, Pearce PT, Funder JW, Krozowski ZS. Type I and type II corticosteroid receptor gene expression in the rat: effect of adrenalectomy and dexamethasone administration. Mol Endocrinol. 1989;3:1674–1680. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-10-1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yamashita R, Kikuchi T, Mori Y, Aoki K, Kaburagi Y, Yasuda K, Sekihara H. Aldosterone stimulates gene expression of hepatic gluconeogenic enzymes through the glucocorticoid receptor in a manner independent of the protein kinase B cascade. Endocr J. 2004;51:243–251. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.51.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liu G, Grifman M, Keily B, Chatterton JE, Staal FW, Li QX. Mineralocorticoid receptor is involved in the regulation of genes responsible for hepatic glucose production. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342:1291–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wada T, Miyashita Y, Sasaki M, Aruga Y, Nakamura Y, Ishii Y, Sasahara M, Kanasaki K, Kitada M, Koya D, Shimano H, Tsuneki H, Sasaoka T. Eplerenone ameliorates the phenotypes of metabolic syndrome with NASH in liver-specific SREBP-1c Tg mice fed high-fat and high-fructose diet. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305:E1415–1425. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00419.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wada T, Kenmochi H, Miyashita Y, Sasaki M, Ojima M, Sasahara M, Koya D, Tsuneki H, Sasaoka T. Spironolactone improves glucose and lipid metabolism by ameliorating hepatic steatosis and inflammation and suppressing enhanced gluconeogenesis induced by high-fat and high-fructose diet. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2040–2049. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Noguchi R, Yoshiji H, Ikenaka Y, Kaji K, Shirai Y, Aihara Y, Yamazaki M, Namisaki T, Kitade M, Yoshii J, Yanase K, Kawaratani H, Tsujimoto T, Fukui H. Selective aldosterone blocker ameliorates the progression of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in rats. Int J Mol Med. 2010;26:407–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gamliel-Lazarovich A, Raz-Pasteur A, Coleman R, Keidar S. The effects of aldosterone on diet-induced fatty liver formation in male C57BL/6 mice: comparison of adrenalectomy and mineralocorticoid receptor blocker. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:1086–1092. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328360554a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fallo F, Dalla Pozza A, Tecchio M, Tona F, Sonino N, Ermani M, Catena C, Bertello C, Mulatero P, Sabato N, Fabris B, Sechi LA. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in primary aldosteronism: a pilot study. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:2–5. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ndisang JF, Jadhav A. The heme oxygenase system attenuates pancreatic lesions and improves insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism in deoxycorticosterone acetate hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R211–223. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.91000.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chuang JC, Cha JY, Garmey JC, Mirmira RG, Repa JJ. Research resource: nuclear hormone receptor expression in the endocrine pancreas. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:2353–2363. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gros R, Ding Q, Sklar LA, Prossnitz EE, Arterburn JB, Chorazyczewski J, Feldman RD. GPR30 expression is required for the mineralocorticoid receptor-independent rapid vascular effects of aldosterone. Hypertension. 2011;57:442–451. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.161653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Barton M. Position paper: The membrane estrogen receptor GPER--Clues and questions. Steroids. 2012;77:935–942. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Batenburg WW, Jansen PM, van den Bogaerdt AJ, AHJD Angiotensin II-aldosterone interaction in human coronary microarteries involves GPR30, EGFR, and endothelial NO synthase. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;94:136–143. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jacovetti C, Abderrahmani A, Parnaud G, Jonas JC, Peyot ML, Cornu M, Laybutt R, Meugnier E, Rome S, Thorens B, Prentki M, Bosco D, Regazzi R. MicroRNAs contribute to compensatory beta cell expansion during pregnancy and obesity. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3541–3551. doi: 10.1172/JCI64151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sharma G, Hu C, Brigman JL, Zhu G, Hathaway HJ, Prossnitz ER. GPER deficiency in male mice results in insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and a proinflammatory state. Endocrinology. 2013;154:4136–4145. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sharma G, Prossnitz ER. Mechanisms of estradiol-induced insulin secretion by the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor GPR30/GPER in pancreatic beta-cells. Endocrinology. 2011;152:3030–3039. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wendler A, Wehling M. Is GPR30 the membrane aldosterone receptor postulated 20 years ago? Hypertension. 2011;57:e16. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.170977. author reply e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mosso LM, Carvajal CA, Maiz A, Ortiz EH, Castillo CR, Artigas RA, Fardella CE. A possible association between primary aldosteronism and a lower beta-cell function. J Hypertens. 2007;25:2125–2130. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282861fa4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Shimamoto K, Shiiki M, Ise T, Miyazaki Y, Higashiura K, Fukuoka M, Hirata A, Masuda A, Nakagawa M, Iimura O. Does insulin resistance participate in an impaired glucose tolerance in primary aldosteronism? J Hum Hypertens. 1994;8:755–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.van der Zijl NJ, Moors CC, Goossens GH, Blaak EE, Diamant M. Does interference with the renin-angiotensin system protect against diabetes? Evidence and mechanisms Diabetes, obesity & metabolism. 2012;14:586–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sowers JR, Raij L, Jialal I, Egan BM, Ofili EO, Samuel R, Zappe DH, Purkayastha D, Deedwania PC. Angiotensin receptor blocker/diuretic combination preserves insulin responses in obese hypertensives. J Hypertens. 2010;28:1761–1769. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833af380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.van der Zijl NJ, Moors CC, Goossens GH, Hermans MM, Blaak EE, Diamant M. Valsartan improves {beta}-cell function and insulin sensitivity in subjects with impaired glucose metabolism: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:845–851. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Luther JM, Gainer JV, Murphey LJ, Yu C, Vaughan DE, Morrow JD, Brown NJ. Angiotensin II induces interleukin-6 in humans through a mineralocorticoid receptor-dependent mechanism. Hypertension. 2006;48:1050–1057. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000248135.97380.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Swaminathan K, Davies J, George J, Rajendra NS, Morris AD, Struthers AD. Spironolactone for poorly controlled hypertension in type 2 diabetes: conflicting effects on blood pressure, endothelial function, glycaemic control and hormonal profiles. Diabetologia. 2008;51:762–768. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-0972-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]