Abstract

Summary: Chimera is a Bioconductor package that organizes, annotates, analyses and validates fusions reported by different fusion detection tools; current implementation can deal with output from bellerophontes, chimeraScan, deFuse, fusionCatcher, FusionFinder, FusionHunter, FusionMap, mapSplice, Rsubread, tophat-fusion and STAR. The core of Chimera is a fusion data structure that can store fusion events detected with any of the aforementioned tools. Fusions are then easily manipulated with standard R functions or through the set of functionalities specifically developed in Chimera with the aim of supporting the user in managing fusions and discriminating false-positive results.

Availability and implementation: Chimera is implemented as a Bioconductor package in R. The package and the vignette can be downloaded at bioconductor.org.

Contact: raffaele.calogero@unito.it

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Fusion genes, also known as chimeras, have become crucial in the areas of biomarkers and therapeutic targets investigation. The emergence of deep sequencing of the transcriptome has opened many opportunities for the identification of this class of genomic alterations, leading to the discovery of novel chimeric transcripts in cancers. A significant number of bioinformatics algorithms have been developed to detect fusion genes (Beccuti et al., 2013). Recently, we have shown that the performances of such tools can be quite variegated and that their false-positive detection rate can be a critical issue (Carrara et al., 2013) (Carrara et al., 2013). Most tools detect fusion events in two steps: (i) alignment to a reference genome to detect discordant alignments, and (ii) refinements of fusion candidates with removal of false-positive results. The second step is particularly critical, as each tool implements a different set of filters (Beccuti et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013), and users have limited control on them. As each fusion detection tool has a specific combination of alignment and filtering approaches, results produced by each tool are only partially comparable with the others’ (Carrara et al., 2013a,b). Thus, although the combination of the results derived from different tools can increase the number of true fusions detected, it also significantly increases the number of false-positive results (see Supplementary Material). The Bioconductor package Chimera, reported in this note, provides a common framework to manipulate, analyze and filter fusion events detected by a variety of fusion detection tools. Chimera is based on typical R data structures, which allows its users to take advantage also of the full set of R functionalities.

2 DESCRIPTION

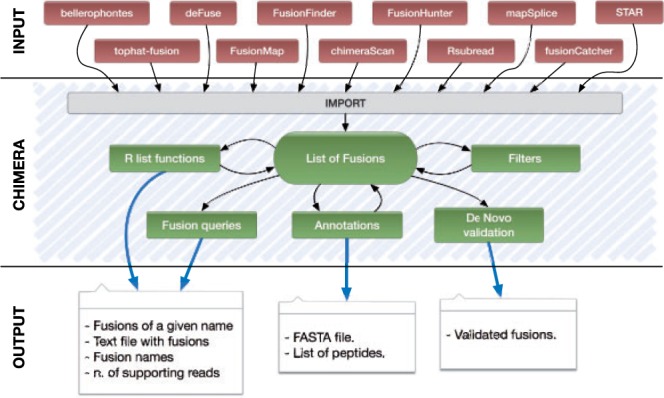

The flow of analysis supported by Chimera is described in Figure 1, and it is exemplified in the note’s Supplementary Material. With the functions made available by Chimera, the user can import data from 11 different fusion detection tools, represented on top of Figure 1, into a list of fusions. Each fusion stores the genomic break point and all the information that can be derived from the output of fusion detection tools (e.g. number of spanning and encompassing reads supporting the fusion junction, splicing pattern used and transcripts involved in the fusion). As each fusion detection tool might rely on different gene annotations, the import function recovers the HUGO (Seal et al., 2011) symbols for the genes involved in the fusion, by overlapping the fusion break points to the genes’ genomic location stored in the Bioconductor package (Gentleman et al., 2004) org.Hs.eg.db, which contains a genome-wide annotation based on Entrez Gene identifiers.

Fig. 1.

The information flow in Chimera

Thus, a fusion involving two annotated genes will be described as SymbolX:SymbolY. In case a break point is located in a non-coding genomic region, it is annotated using its genomic coordinates (e.g. NBPF1:chr14:81937890-81937920).

A list of fusions can be manipulated, as in Figure 1, using basic R list functions (e.g. concatenation) or with the set of Chimera ‘fusion queries’, e.g. function fusionName extracts the fusion name in the above described format (e.g. SPDYE8P:SLC24A5), function prettyPrint stores fusions description in a tab delimited file and function supportingReads extracts supporting reads for a given fusion.

2.1 Fusion filtering

Once the user has created and inspected the fusion list with the above functionalities, he/she might decide to filter the fusions through a select/exclude mechanism. Available filtering criteria are as follows: (i) a (user defined) threshold for the number of encompassing/spanning reads; (ii) a specific subset of fusion names; (iii) the presence of annotated gene names in fusions (e.g. SPDYE8P:SLC24A5 is kept, NBPF1:chr14:81937890-81937920 is excluded); (iv) fusions belonging to long distance exons of the same gene (e.g. SPDYE8P: SPDYE8P is discarded) and (v) presence of an intron at the fusion junction. This last filter is justified by the fact that analysis is performed on mature mRNAs. Thus, in case long introns are retained at the fusion break point, it is likely that such fusion event will not be translated into a functional protein.

2.2 Annotation

A user willing to complete, or enrich, fusion data can use Chimera functionalities for annotation (‘Annotations’ block in Fig. 1). The annotation facility allows to generate (i) the nucleotide sequence of a (list of) fusions (chimeraSeqSet); (ii) the number of supporting reads; and (iii) the list of fusion encoded peptides.

This additional information could be used as final output or to enrich the information present in a fusion object. In particular, the output of chimeraSeqSet is a R DNAStringSet object that can be exported as a fasta file and that can enrich the fusion information (with the method addRNA). This output can also be used by the function fusionPeptides to explore the fusion at the protein level (the function retrieves the peptide regions involved and evaluates whether the fusion will produce an in-frame polypeptide). Chimera also embeds Oncofuse (Shugay et al., 2013), a naive Bayes Network Classifier that provides a variegated annotation of fusions, as well as a score for the probability that a fusion acts as tumor driver.

2.3 Validation

Finally, a user can take advantage of Chimera to perform a first step of validation, which can be useful given the high number of false-positive results reported, in most cases, by fusion detection tools. Fusion break points are assessed by de novo assembly using GapFiller (Nadalin et al., 2012). GapFiller is a seed-and-extend method able to correctly fill the gap between paired reads, thus it generates accurate longer sequences with respect to input reads.

The supporting reads of a fusion (whether made available by the fusion detection tool or through the Chimera annotation functions) are assembled with GapFiller into a reference. The nucleotide sequence of the fusion break point, reconstructed by chimeraSeqSet, is then checked for inclusion against the de novo assembled reference. Validation is particularly useful for the correct evaluation of fusion events supported by few reads (see Supplementary Material).

3 DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, Chimera is the only available software able to integrate and compare the data produced by different fusion detection tools. Thus, it represents an answer to the lack of standard data structure for fusion data representation. Furthermore, as the combination of results from more than one fusion detection tool enhances the probability to identify fusion events (see Supplementary Material), Chimera provides a common framework to manipulate, filter and prioritize fusion events. Moreover Chimera offers a validation procedure based on de novo assembly (thanks to the GapFiller tool) and enhances fusions’ annotation through the exploitation of the Oncofuse results.

Funding: This work was supported by the Epigenomics Flagship Project EPIGEN and the European 7th frame-work program, Health.2012.1.2-1, NGS-PTL grant n. 306242.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Beccuti M, et al. The structure of state-of-art gene fusion-finder algorithms. Genome Bioinformatics. 2013;1:2. [Google Scholar]

- Carrara M, et al. State of art fusion-finder algorithms are suitable to detect transcrip-tion-induced chimeras in normal tissues? BMC Bioinformatics. 2013a;14(Suppl. 7):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-S7-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrara M, et al. State-of-the-art fusion-finder algorithms sensitivity and specificity. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013b;2013:340620. doi: 10.1155/2013/340620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman RC, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for comptional biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadalin F, et al. GapFiller: a de novo assembly approach to fill the gap within paired reads. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13(Suppl. 14):S8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-S14-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal RL, et al. genenames.org: the HGNC resources in 2011. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D514–D519. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shugay M, et al. Oncofuse: a computational framework for the prediction of the oncogenic potential of gene fusions. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:2539–2546. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, et al. Application of next generation sequencing to human gene fusion detection: computational tools, features and perspectives. Brief. Bioinform. 2013;14:506–519. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.