Abstract

The allosteric regulation of substrate channeling in tryptophan synthase involves ligand-mediated allosteric signaling that switches the α- and β-subunits between open (low activity) and closed (high activity) conformations. This switching prevents the escape of the common intermediate, indole, and synchronizes the α- and β-catalytic cycles. 19F NMR studies of bound α-site substrate analogues, N-(4’-trifluoromethoxybenzoyl)-2-aminoethyl phosphate (F6) and N-(4’-trifluoromethoxybenzenesulfonyl)-2-aminoethyl phosphate (F9), were found to be sensitive NMR probes of β-subunit conformation. Both the internal and external aldimine F6 complexes gave a single bound peak at the same chemical shift, while α-aminoacrylate and quinonoid F6 complexes all gave a different bound peak shifted by +1.07 ppm. The F9 complexes exhibited similar behavior, but with a corresponding shift of -0.12 ppm. X-ray crystal structures show the F6 and F9 CF3 groups located at the α-β subunit interface and report changes in both the ligand conformation and the surrounding protein microenvironment. Ab initio computational modeling suggests that the change in 19F chemical shift results primarily from changes in the α-site ligand conformation. Structures of α-aminoacrylate F6 and F9 complexes and quinonoid F6 and F9 complexes show the α- and β-subunits have closed conformations wherein access of ligands into the α- and β-sites from solution is blocked. Internal and external aldimine structures show the α- and β-subunits with closed and open global conformations, respectively. These results establish that β-subunits exist in two global conformation states, designated open, where the β-sites are freely accessible to substrates, and closed, where the β-site portal into solution is blocked. Switching between these conformations is critically important for the αβ-catalytic cycle.

Conformational switching in allosteric proteins is driven by ligand binding and/or reaction at allosteric sites. Since publication of the landmark paper of Monod, Wyman and Changeux in 19651, the mechanisms by which allosteric transitions occur has been a topic of much speculation and vigorous investigation2. Allosteric conformational transitions in proteins are essential to the regulation of many biological processes1-7. It is now recognized that the roles played by allosteric interactions extend far beyond the regulation of intermediary metabolism or the modulation of oxygen transport by hemoglobin. The ever-growing list of allosteric protein systems includes the transport of metabolites across cell membranes, signal transduction, protein synthesis by the ribosome, transcriptional regulation, tumor necrosis factors, and gene expression.1-7

It has been demonstrated that in many metabolic pathways, some of the enzymes form bienzyme complexes in which a common metabolite is channeled from one site to the next via an interconnecting tunnel.5-15 This channeling is often subject to allosteric regulation.6,11,14,15 In the anthranilate branch of the aromatic amino acid synthetic pathway, enteric bacteria utilize the tryptophan synthase bienzyme complex to carry out the last two steps in the biosynthesis of L-Trp. Catalysis by this α2β2 oligomer involves the cleavage of 3-indole-D-glycerol 3’-phosphate (IGP) to D-glycerol 3-phosphate (G3P) and indole at the α-sites (Scheme 1a), and replacement of the β-hydroxyl of L-Ser by indole to form L-Trp at the pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) requiring β-sites (Fig 1b, Stages I and II).16 The channeling of indole from the α-site to the β-site via a 25 Å-long interconnecting tunnel within αβ dimeric units is an important component of this process.17,18 At the β-site, substrates indole and L-Ser react through a series of PLP-mediated chemical steps to give L-Trp and a water molecule (Scheme 1b).19,20 This complicated catalytic cycle operates under the control of allosteric interactions acting between the α- and β-sites that are triggered by substrate binding to the α-site, and by covalent reactions involving substrates L-Ser and indole with PLP at the β-site.8,14,15,18 A monovalent cation site near the β-catalytic site modulates the transmission of these allosteric interactions.14,21 - 27 The relationship of the structure of the S. typhimurium enzyme to catalysis and to allosteric regulation has been recently reviewed in detail.11-14

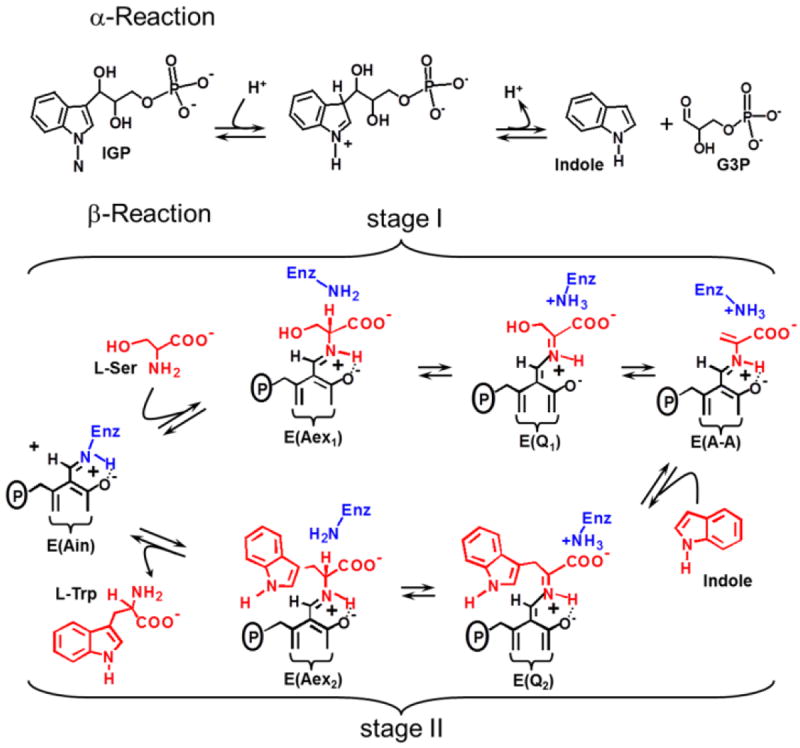

Scheme 1.

Chemistry of the physiological reactions catalyzed by the α- and β-sites. Redrawn from reference 27.

Figure 1.

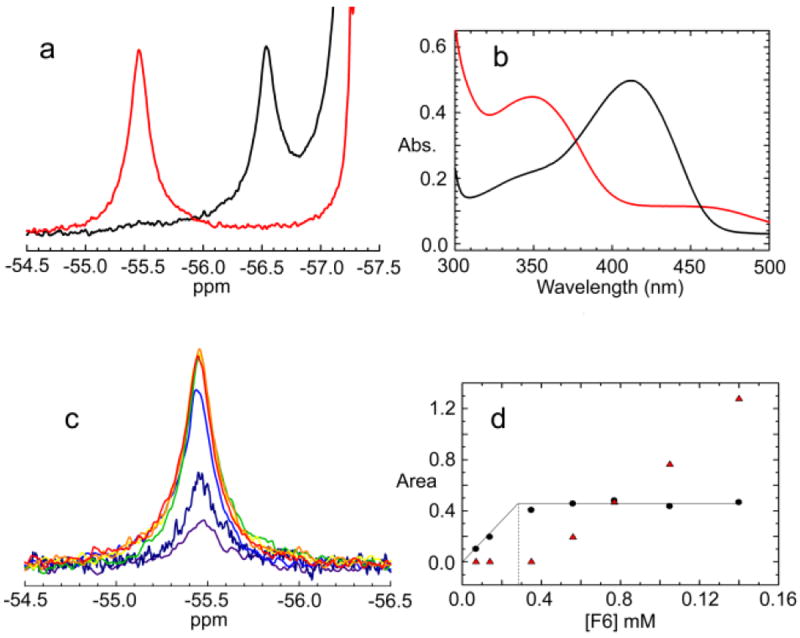

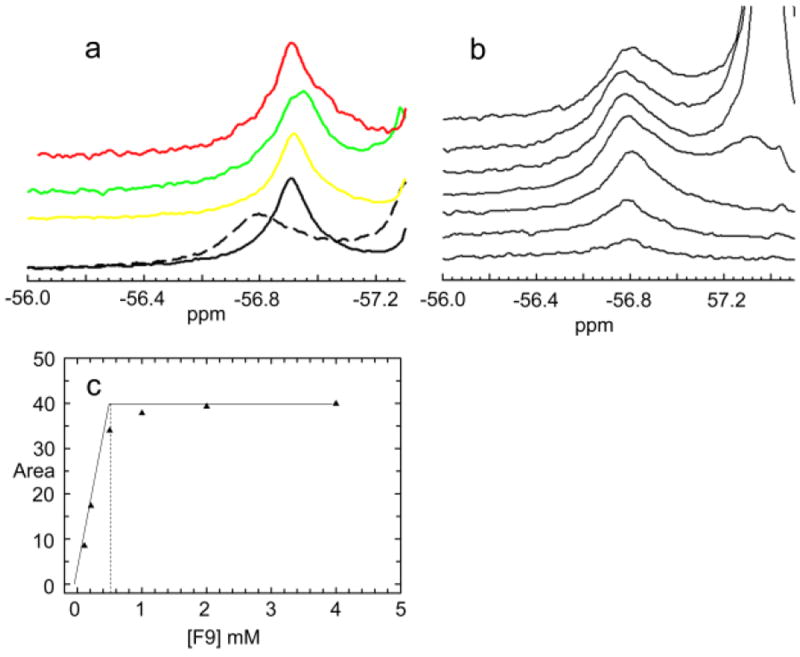

a: 19F NMR spectra of the (F6)(Na+)E(Ain) and (F6)(Na+)E(A-A) complexes (black and red lines, respectively). Conditions: αβ, 605 μM; F6, 1.4 mM; Na+, 100 mM and L-Ser, 200 mM when present. b: UV/Vis absoption spectra of the NMR of samples in a. Enzyme concentration: αβ, 5.6 μM. c: 19F spectra of the bound peak for the conditions [F6] < [sites] to [F6] > [sites]. Conditions: αβ = 300 μM; F9 concentrations: 70 μM (black), 140 μM (purple), 350 μM (blue), 560 μM (green), 770 μM (yellow) 1.05 mM (light orange), 1.40 mM (dark orange). d: Dependencies of the F9 peak areas from Figure 1c for the bound species (black circles) and for the free species (orange triangles) (peaks not shown) on the concentration of F6. The intersection point of the tangents drawn through the data points indicates the F6 binding stoichiometry is approximately 1:1.

Two types of mechanisms often have been postulated to explain the triggering of allosteric transitions by ligand binding/reaction. One postulates that allosteric behavior arises from ligand binding to pre-existing global protein conformational states (MWC-like mechanisms).1 The second postulates that allosteric behavior arises from a ligand binding induced-fit process (KNF-like mechanisms).28 Herein, we also make a distinction between global conformation changes (changes that alter distant sites, i.e., allosteric interactions), and local conformation changes (changes resulting from ligand binding interactions with neighboring residues at the site). Solution studies18,27,29-41 and the x-ray structures for tryptophan synthase17,42-52 established that the αβ dimeric units of the tetrameric complex undergo global conformational transitions between open conformations of low activity and closed conformations of high activity during the catalytic cycle. This allosteric coupling of open and closed conformation states with low and high activity states is essential to the regulation of tryptophan synthase; the closed structures render efficient the channeling of indole between the α- and β-sites by preventing the escape of indole, while the switching between low and high activity states synchronizes the catalytic cycles of the α- and β-sites.14,31-35 As shown in Chart 1a.11 synchronization of the α- and β-catalytic cycles is achieved through a mechanism wherein the α-site is switched to a high activity state by a conformational transition at the β-site triggered by the conversion of E(Aex1) to E(A-A), via E(Q1). The α-site is then switched off by a reversal of this conformational transition triggered by the conversion of E(Q3) to E(Aex2) (Chart 1a). The available x-ray structures have characterized three conformational states of the α-subunit: ligand-free structures show 12 to 16 residues of loop αL6 are disordered.17,45 Ligand-bound forms give structures where αL6 is either partially disordered (typically 6 to 10 residues), or well-ordered (no more than one or two disordered residues) depending on the conformational state and monovalent cation form of the β-subunit.17,38,39,44-47

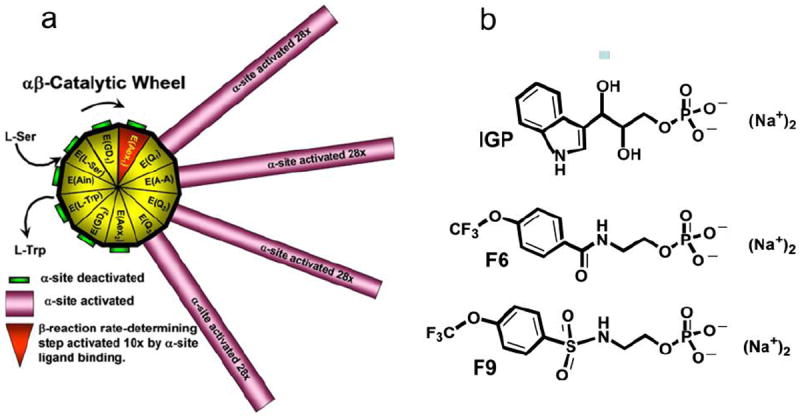

Chart 1.

a Representation of the chemical and conformational events which synchronize the α-and β- catalytic activities of αβ-dimeric units of tryptophan synthase and prevent the escape of indole. The 11 chemical states of the β-reaction are depicted as triangles around the hub of the catalytic wheel. The spokes connected to the triangles of the hub represent the activity states of the α-site as the β-site cycles through the 11 chemical states. The α-subunit is switched between inactive (green) and active (magenta) conformations in response to the interconversion among covalent intermediates along the β-site catalytic path. This switching activates or deactivates the α-site by ~28-fold. Activation of the α-site occurs when the L-Ser external aldimine, E(Aex1) is converted to the α-aminoacrylate Schiff base, E(A-A), while deactivation occurs when the quinonoid intermediate, E(Q3), is converted to the L-Trp external aldimine, E(Aex2). During Stage I of the β-reaction the rate-limiting conversion of E(Aex1) (red triangle) to E(A-A) is activated at least 10-fold by IGP binding to the α-site. (Figure taken from Dunn et al.11). This switching between low (open) and high (closed) activity states synchronizes the α- and β-catalytic activities, preventing the escape of indole as it is transferred between the α- and β-sites. b: Structures of N-(4’-trifluoromethoxybenzoyl)-2-aminoethyl phosphate (F6), and N-(4’-trifluoromethoxybenzenesulfonyl)-2-aminoethyl phosphate (F9).

The chemical intermediates in the β-subunit catalytic cycle (Scheme 1b) have been determined through chemical, kinetic, and spectroscopic experiments dating from the 1960’s.8,9,11,14,16,19,20,53-57 However, the relationships between covalent state and conformation state for events in the β-subunit catalytic cycle have not been completely determined, and the number of global conformation states required for the catalytic cycle is an open question. The evidence for conformational transitions between open and closed states during the catalytic cycle is derived from kinetic tests of the accessibility of the β-site to ligands from solution.18,32-37,39 Two global β-subunit conformations, open and closed, have been well characterized by x-ray crystallographic determinations of structure.17,38,39,43,44,46-52

The E(Ain), and E(Aex1) chemical states, and almost certainly the E(GD) states, favor the open conformation, while the E(Q) states, and the E(A-A) state favor the closed conformation (viz., Chart 1a).11,14 Since 2007, several structures with the closed β-site conformation have been reported for wild-type enzyme complexes: (a) A structure of the Na+ form of the α-aminoacrylate species with G3P bound to the α-site,39 designated as (Na+)(G3P)E(A-A). (b) Two structures of the Cs+ form of the α-aminoacrylate species, both with N-(4’-trifluoromethoxybenzenesulfonyl)-2-aminoethyl phosphate (F9) (Chart 1b) bound to the α-site and one with benzimidazole (BZI) also bound at the indole subsite of the β-subunit.49,50 These are designated respectively as (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A) and (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A)(BZI). There are two structures of the Cs+ form of the indoline quinonoid species, one with a transition-state analogue formed between indoline and G3P bound to the α-site,46 designated as (NGP)(Cs+)E(Q)indoline; the other two with F9 bound to the α-site,46,47 designated as (F9)(Cs+)E(Q)indoline. (c) The Na+ and Cs+ forms of the quinonoid species derived from reaction of 2-aminophenol (2AP) with E(A-A),51,52 designated respectively as (F6)(Na+)E(Q)2AP, and (F9)(Cs+)E(Q)2AP. (d) Rhee et al.43 reported that a tryptophan synthase variant with β-active site Lys87 replaced by Thr gives similar closed structures. There are two complexes with the L-Ser external aldimine, and one with the L-Trp external aldimine. (e) Blumenstein et al.58 reported that reaction of L-Ser, with the variant with β-site Gln114 replaced by Asn also gives a closed β-site complex. The relatively small number of closed structures thus far reported arises from the difficulty of obtaining crystals with the closed conformation.11,39,46,47

Herein we further investigate the role played by the switching between the open and closed conformations in the regulation of substrate channeling for tryptophan synthase using unractive fluorinated substrate analogues which give signatures of the subunit conformation state in solution.

It is well established that CF3-substituted ligands are particularly sensitive 19F NMR probes of ligand binding and conformational change in protein complexes.59-67 In comparison to 1H chemical shifts, the 19F resonance of the CF3 group is much more sensitive to small changes in the electrostatic environment arising from a change in protein conformation state.59-67 Protein complexes of ligands with CF3 substituents often give bound states that are in slow exchange (on the NMR time scale) with the free ligand, and the CF3 substituent usually gives a simple signal.

Here we present 19F NMR and single crystal x-ray diffraction studies to further characterize the allosteric linkages between ligand binding, chemical reaction, and conformation change in the substrate-channeling tryptophan synthase bienzyme complex. To accomplish this objective, we synthesized and characterized a new set of substrate analogues for IGP.38,39 Six x-ray crystal structures of these ligands bound to the α-site of tryptophan synthase have been reported.38,39,47-52 The chemical structures of the two IGP analogues important to this study, N-(4’-trifluoromethoxybenzoyl)-2-aminoethyl phosphate (F6) and N-(4’-trifluoromethoxybenzenesulfonyl)-2-aminoethyl phosphate (F9), together with the structure of IGP are shown in Chart 1b. The binding of F6 and F9 to tryptophan synthase species with different β-site chemical states are examined herein via detailed 19F NMR studies and by analysis of the high-resolution, single-crystal x-ray structures of some of these complexes. As will be shown, the CF3 groups of the F6 and F9 complexes provide 19F signals which sample the channel microenvironment at the α-β subunit interface. It will be shown herein that the chemical shifts of these probes provide signatures which distinguish between the open and closed conformation states of the β-subunit. These findings are consistent with an allosteric mechanism wherein the β-site is switched between two global conformation states, one open, which allows the facile exchange of ligands between solution and the β-site, the other closed, which strongly hinders the exchange of bound and free ligands and activates catalysis at the α- and β-catalytic sites.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

L-Ser, L-Trp, L-His, indoline, benzimidazole, 2-aminophenol, CsCl, and NaCl, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Indoline was purified as previously described.68 N-(4’-trifluoromethoxybenzoyl)-2-aminoethyl phosphate (F6) and N-(4-trifluoromethyoxylbenzenesulfonyl)-2-amino-1-ethylphosphate (F9) were synthesized as described.38 All solutions were prepared at 25 ± 2° C and maintained at pH 7.8 in 50 mM triethanolamine (TEA) buffer. Salmonella tryphimurium α2β2 tryptophan synthase was purified as previously described.69

UV-Visible Spectral Measurements

Static UV/Vis absorbance spectra were collected on a Hewlett-Packard 8452A diode array spectrophotometer. Samples were maintained at 25°C ± 2° in 50 mM TEA buffer at pH 7.8. The UV/Vis spectra of 19F NMR samples were determined immediately after collection of the NMR data.

One dimensional 19F NMR studies

A Varian Inova 500 MHz NMR spectrometer, equipped with a 5 mm Nalorac 1H/19F probe operating at a frequency of 470.56 MHz was used to collect 19F NMR spectra. All 19F-NMR samples were prepared in aqueous buffers adjusted to pH 7.80 containing 10% D2O (v/v) and locked on the D2O field frequency (no pH correction was made for the D2O content). Data were accumulated at 25 °C with a relaxation delay of 2 s over a spectral width of 28429 Hz (56 ppm) as 16384 complex point FIDs. For each experiment, 256 transients were accumulated and averaged. Spectra were processed with 3 Hz line broadening apodization applied. Chemical shift values are referenced relative to the external standard, trichlorofluoromethane (δ = 0.00 ppm).

Computational Chemistry

Ab initio calculations were performed within the Gaussian 03 software package.70 Geometry optimizations were performed using the ONIOM method71 (B3LYP/6-31G(d,p):PM3) with partitioning between the high and low levels as described in the text. 19F NMR chemical shifts were calculated for geometry-optimized structures at the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level.72

Structure Alignments

Alignments were carried out using the software, PyMOL 1.1r. Alignment of the α-subunits was accomplished by overlaying the Cα atoms of residues 6 to 170. Alignments of the β-subunits was accomplished27 by overlaying the Cα of residues 1-101. Alignments to compare β-active sites of different conformation states were accomplished with PyMOL using paired selections consisting of the C and N atoms in the PLP cofactor ring and the phosphoryl P of each structure. These alignments showed RMSD values of 0.07 to 0.08.

Single Crystal X-Ray Crystallography

Crystallizations of the F9 complexes of the internal aldimine, the α-aminoacrylate (with and without BZI), and the 2-AP quinonoid species with the Na+ and Cs+ forms of tryptophan synthase were accomplished as previously described by Lai et al.47 The Cs+ forms of the enzyme are known to stabilize the closed conformation of the β-subunit.27 Therefore, to extend the structural data base of tryptophan synthase consisting of structures with closed β-subunit conformations, we focused this crystallization effort on complexes with Cs+ bound to the monovalent cation site and β-site chemical intermediates proposed to have closed β-subunit conformations. We also determined the structure of the (F6)(Na+)E(Q)2AP complex for this work.

Accession Numbers

Coordinates and structure factors for (F9)(Cs+)E(Ain), (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A), (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A)(BZI), (F6)(Na+)E(Q)2AP and (F9)(Cs+)E(Q)2AP have been deposited in the PDB with the accession nos.: 4HT3; 4HN4; 4HPX; 4KKX and 4HPJ, respectively. The crystal parameters, data collection, and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Crystal Parameters, Data Collection, and Refinement Statistics

| Complex | (F9)(Cs+)E(Q)2AP | (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A)(BZI) | (F9)(Cs+)E(Ain) | (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A) | (F9)(Na+)E(Q)2AP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB entry | 4HPJ | 4HT3 | 4HPX | 4HN4 | 4KKX |

| Data collection | |||||

| space group | C 1 2 1 (no. 5) | C 1 2 1 (no. 5) | C 1 2 1 (no. 5) | C 1 2 1 (no. 5) | C 1 2 1 (no. 5) |

| cell dimensions | |||||

| a (Å) | 184.33 | 181.77 | 183.96 | 183.97 | 183.87 |

| b (Å) | 59.72 | 59.11 | 60.96 | 59.72 | 61.46 |

| c (Å) | 67.39 | 67.25 | 67.41 | 67.40 | 67.39 |

| resolution (Å) | 1.45 | 1.30 | 1.65 | 1.64 | 1.77 |

| X-ray source | ALS SIBYLS | ALS SIBYLS | MM-007HF | MM-007HF | MM-007HF |

| Rmerge (%) a | 9.5 (44.7) | 6.6 (48.9) | 6.1 (33.0) | 4.9 (22.0) | 7.1 (46.4) |

| mean I/σ(I) | 13.1 (2.4) | 10.1 (2.7) | 10.8 (2.7) | 12.6 (3.7) | 9.8 (2.0) |

| no. of reflections | 844041 (30907) | 582792 (82234) | 314928 (44289) | 283827 (37345) | 178798 (25633) |

| no. of unique reflections | 109585 (11872) | 171588 (24448) | 87817 (12465) | 86376 (11453) | 63604 (8825) |

| completeness (%) | 96.4 (62.9) | 98.4 (96.4) | 98.3 (96.2) | 95.7 (87.3) | 99.0 (82.9) |

| redundancy | 7.7 (2.6) | 3.4 (3.4) | 3.6 (3.6) | 3.3 (3.3) | 2.8 (2.9) |

| Refinement | |||||

| resolution range (Å) | 19.67-1.45 | 18.36-1.30 | 28.19-1.65 | 28.59-1.64 | 29.43-1.77 |

| no. of reflections | 104037 | 157562 | 83394 | 81320 | 63561 |

| Rwork / Rfree (%) b | 14.66/18.93 | 13.09/16.94 | 14.21/19.01 | 14.78/20.04 | 15.11/19.64 |

| no. of atoms | |||||

| protein | 5131 | 5294 | 5263 | 5132 | 5191 |

| ligand | 91 | 185 | 138 | 97 | 124 |

| water | 644 | 765 | 722 | 676 | 928 |

| Cs+ or Na+ ion | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| average B value (Å2) | |||||

| protein | 18.02 | 14.73 | 21.6 | 19.88 | 15.99 |

| ligand | 23.5 | 25.1 | 28.6 | 24.75 | 28.90 |

| water | 30.5 | 31.89 | 34.4 | 31.46 | 32.61 |

| Cs+ or Na+ ion | 16.93 | 13.07 | 21.29 | 22.59 | 17.82 |

| root-mean-square deviation | |||||

| bond lengths (Å) | 0.0106 | 0.0110 | 0.0102 | 0.011 | 0.011 |

| bond angles (deg) | 1.4531 | 1.6373 | 1.4274 | 1.427 | 1.299 |

| Ramachandran plot | |||||

| most favored regions | 528 (94.1%) | 523 (93.4%) | 530 (94.5%) | 526 (93.8%) | 523 (93.2%) |

| additionally allowed regions | 32 (5.7%) | 36 (6.4%) | 29 (5.2%) | 34 (6.1%) | 37 (6.6%) |

| generously allowed regions | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.4%) | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| disallowed regions | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Rmerge = Σhkl Σi |Ii(hkl) - <I(hkl)>| / Σhkl Σi Ii(hkl), where Ii(hkl) and <I(hkl)> are the observed individual and mean intensities of a reflection with the indices hkl, respectively, Σi is the sum over i measurements of a reflection with the indices hkl, and Σhkl is the sum over all reflections.

R = Σhkl ∥Fobs|-|Fcalc∥ / Σhkl|Fobs|. Rfree was calculated with the 5% of reflections set aside throughout the refinement. The set of reflections for Rfree calculation was kept the same for all five data sets.

RESULTS

Binding of the α-Site Substrate Analogue F6 to the Internal Aldimine and α-Aminoacrylate Forms of the Tryptophan Synthase Bienezyme Complex

Figure 1a shows one dimensional 19F-NMR spectra of the (F6)(Na+)E(Ain) and (F6)(Na+)E(A-A) complexes at 25.0° C. The (F6)(Na+)E(Ain) spectrum (a) shows the presence of a single, upfield-shifted and broadened peak corresponding to the bound species with a chemical shift of -56.52 ppm ± 0.01 ppm relative to an external standard of CFCl3. The bound peak is well described by a lorentzian line shape. The peak with a chemical shift of -57.3 ppm consists of a sharp signal arising from unbound (free) F6. UV/Vis absorption spectra of the NMR sample (Figure 1b, spectrum a) confirmed that the β-site retains the characteristic spectrum of the (Na+)E(Ain) species with λmax = 412 nm16,21,22,38,39 throughout the time period of the NMR data acquisition.

The reaction of L-Ser with (Na+)E(Ain) gives an equilibrating mixture of intermediates in Stage I of the β-reaction dominated by (Na+)E(Aex1) and (Na+)E(A-A).19 The binding of F6 shifts the distribution of species strongly in favor of the (F6)(Na+)E(A-A) species.38 The 1D 19F-NMR spectra of the (F6)(Na+)E(A-A) complex (Figure 1a, spectrum b), exhibits an upfield-shifted and broadened peak corresponding to bound F6 with a chemical shift of -55.45 ± 0.01 ppm at 25.0° C. As expected, the UV/Vis absorption spectrum (Figure 1b, spectrum b) indicates that the predominating enzyme-bound species formed when (Na+)E(Ain) is reacted with L-Ser in the presence of F6 is the (F6)(Na+)E(A-A) complex with chemical shift -55.45 ± 0.01 ppm.38,39 The 19F chemical shift of the -55.45 ± 0.01 ppm peak for (F6)(Na+)E(A-A) (Figure 1c) under the conditions of the titration, [F6] < [sites] to [F6] > [sites], was found to be concentration independent, a finding consistent with ligand exchange processes between free and bound states that are slow compared to the NMR time scale. For this titration, the dependence of the areas of the free and bound peaks on the concentration of F6 are shown in Figure 1d. These data show that the binding of F6 to (Na+)E(A-A) occurs with a stoichiometry of approximately one per αβ dimeric unit, a result consistent with the findings of Ngo et al.38,39

Binding of the α-Site Substrate Analogue F6 to the (Na+)E(A-A)(BZI), (Na+)E(Q)indoline and (Na+)E(Q)aniline Complexes

The binding of the unreactive indole analogue, BZI, to the β-site also shifts the distribution of intermediates formed in Stage I of the β-reaction in favor of the (Na+)E(A-A) species.18,36,37,73,74 The complex of F6 with (Na+)E(A-A)(BZI) gives an 19F spectrum for bound F6 with a chemical shift of -55.45 ± 0.01 ppm (Figure 2a, spectrum a). The UV/Vis absorption spectrum of this sample (Figure 2b, spectrum a) shows that essentially all of the enzyme is converted to the (F6)(Na+)E(A-A)(BZI) species.38,39

Figure 2.

a: 1D 19F NMR spectra of the (F6)(Na+)E(A-A)(BZI) complex (black), the (F6)(Na+)E(Q)indoline complex (red) and the (F6)(Na+) E(Q)aniline complex (green). Conditions: αβ, 605 μM; Na+, 100 mM; L-Ser, 200 mM; and when present, BZI, 10 mM; indoline, 5 mM; aniline, 10 mM. b: UV/Vis absorption spectra of the (F6)(Na+)E(A-A)(BZI) complex (black; αβ, 7.5 μM) and of the (F6)(Na+)E(Q)indoline (red; αβ, 1.36 μM) from the NMR samples in Figure 2a.

The 19F NMR spectrum of the species formed in the reaction of L-Ser and indoline with the enzyme in the presence of F6 is shown in Figure 2a (spectrum b) under conditions where formation of (F6)(Na+)E(Q)indoline is the dominant species.27,36,37,68 The NMR spectrum shows this species also is characterized by a chemical shift of -55.45 ± 0.01 ppm. The UV/Vis absorption spectrum of the NMR sample (Figure 2a, spectrum b) confirms that the 19F NMR spectrum is derived from the (F6)(Na+)E(Q)indoline intermediate. Substitution of aniline for indoline gives the aniline quinonoid species, E(Q)aniline.18 The binding of F6 to the Na+ form of this quinonoid gives an 19F NMR spectrum (Figure 2a, spectrum c) that is essentially identical to that of E(Q)indoline (spectrum b) with a chemical shift of -55.45 ± 0.01 ppm. The (F6)(Na+)E(Q)2AP complex also gives a chemical shift of -55.45 ± 0.01 ppm. Just as found with the complexes in Scheme 1, the exchange between bound and free states appears to be slow with respect to the NMR time scale for all of the complexes presented in Figure 2.

F9 Binding to Intermediates and Intermediate Analogues in Stage I of the β-Reaction

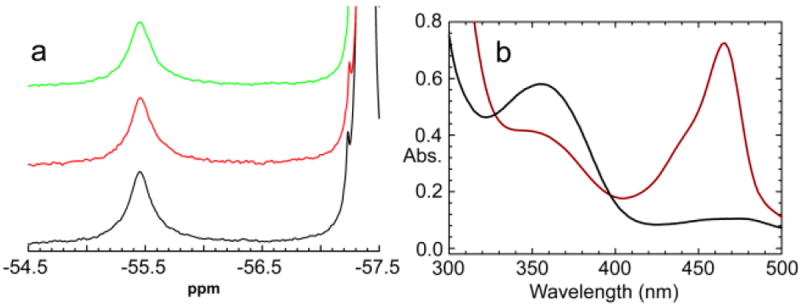

Figure 3a shows the bound 19F NMR peaks for the complexes of F9 with the Na+ forms of E(Ain), E(A-A), E(A-A)(BZI), E(Q)indoline and E(Q)2AP under conditions where the concentration of F9 is in large excess of the enzyme sites. The F9 complex with (Na+)E(Ain) (dashed black line) exhibits a bound peak with chemical shift -56.79 ± 0.01 ppm. The complexes of F9 with the Na+ forms of E(A-A), E(A-A)(BZI), E(Q)indoline and E(Q)2AP all give bound peaks with chemical shift -56.91 ± 0.01 ppm.

Figure 3.

a: 19F NMR peaks for the complexes of F9 with (Na+)E(Ain) (dashed black line), (Na+)E(A-A) (black), (Na+)E(A-A)(BZI) (yellow), (Na+)E(Q)indoline (green) and (Na+)E(Q)2AP (red). Concentrations: αβ, 0.605 mM; and when present, L-Ser, 20 mM; BZI, 10 mM; indoline, 4 mM; aniline, 10 mM; NaCl, 100 mM. b: Titration of (Na+)E(Ain) (αβ = 0.850 mM) with F9. F9 concentrations (increasing from bottom to top): 0.11 mM; 0.21 mM; 0.50 mM; 1.00 mM; 2.00 mM; 4.00 mM. The bound peak is located at -56.78 ppm. Figure 5c: Titration plot showing the area of the bound peak vs the concentration of F9. The intersection point of the tangents drawn through the data points indicates the F9 binding stoichiometry is approximately 1:1.

Titration of (Na+)E(Ain) with F9 gave the set of 19F NMR spectra shown in Figure 3b. When [F9] < [E sites], only a single peak is observed with chemical shift -56.91 ± 0.01 ppm. This peak is due to the binding of F9 to the α-site. When [F9] > [E sites], a second peak corresponding to unbound (free) F9 with chemical shift -57.32 ± 0.01 ppm also is present. The plot of the area of the bound peak vs. [F9] (Figure 3c) indicates that F9 binds tightly to (Na+)E(Ain) with a stoichiometry of ~ one per αβ-dimeric unit, in agreement with the findings of Ngo et al.38,39 The invariance of the chemical shifts of the bound and free peaks is consistent with slow exchange of F9 between the free and bound states with respect to the NMR time scale.

F6 Binding to the Complexes Formed with L-Trp

The Supporting information (Figure S1) shows that the reaction of L-Trp with The (Na+)E(Ain) complex gives a mixture of the external aldimine and quinonoid species, (F6)(Na+)E(Aex2) and (F6)(Na+)E(Q3).18,20,25,55 each with a chemical shift of −55.45 ± 0.01 ppm for bound F6.

Monovalent Cation Effects on the Chemical Shifts of the F6 and F9 complexes

Comparison of complexes with Cs+ substituted for Na+ alters the redistribution of β-site chemical intermediates and the distribution of open and closed conformational states,21, 27 however, the chemical shifts observed for the bound forms of F6 and F9 are unchanged (see Supplemental Information, Figure S2).

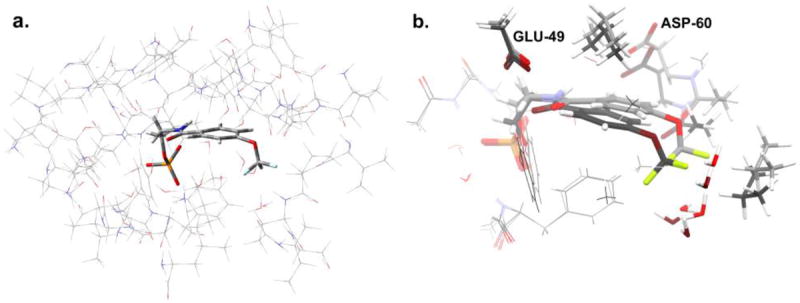

Calculation of Chemical Shifts Based on α-Site X-Ray Structure Models

Inspection of the complexes of the superimposed structures of (F6)(Na+)E(Ain) and (F6)(Na+)E(Q)2AP indicate that both the ligand geometry and the microenvironment surrounding the CF3 group in each structure are different. To quantify the effects of these two structural differences on CF3 19F chemical shifts, ab initio calculations were undertaken, following the procedure outlined in reference 47. The x-ray structures of the (F6)(Na+)E(Ain) and (F6)(Na+) E(Q)2AP complexes were used as the starting points. From these, models of the α-subunit enzyme active site (residues within 7 Å of the substrate) were constructed for both the (F6)(Na+)E(Ain) and (F6)(Na+) E(Q)2AP structures (Figure 4a and 4b).

Figure 4.

a. Model of the active site in the α-subunit of tryptophan synthase, showing (thin wireframe) the side chains fixed at their crystallographically-determined coordinates and (thick wireframe) the F6-substrate. The structure shown corresponds to the (F6)(Na+)E(Q)2AP form; an analogous model was built for (F6)(Na+)E(Ain). b: Superposition of the geometry-optimized F6 substrates for (F6)(Na+)E(Ain) (light gray carbon atoms) and (F6)(Na+)E(Q)2AP (dark gray carbon atoms) forms, also showing residue fragments within 3 Å of the CF3 group. These substructures were used for calculating NMR chemical shifts. The standard CPK scheme is used to designate the atom colors (H, white; C, gray; N, blue; F: green; O, red; P, orange; S, yellow).

In constructing these models, broken bonds at the edges of the models were terminated by replacing N-terminal nitrogens with hydrogens and C-terminal carbonyls with carboxamides. This provided a framework for optimizing the geometry of the F6-ligand that explicitly took into account the differences in microenvironments. Structures were optimized to ground state geometries using the ONIOM method71 in Gaussian03,70 with the side chains treated at the PM3 semi-empirical level of theory and the substrate treated at the density functional level of theory (B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)). During the geometry optimization, non-hydrogen side chain atoms were fixed at their crystallographically determined coordinates. In both the (F6)(Na+)E(Ain) and (F6)(Na+) E(Q)2AP substrate optimizations, very minor changes in geometry were observed relative to starting structures (RMSD for non-hydrogen atoms on the ligands was 0.29 Å RMSD for (F6)(Na+) E(Q)2AP). Ab initio chemical shifts were then calculated at the full DFT level of theory (B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p)) for each of the superimposed sub-structures shown in Fig 4b, which included all of F6 and the truncated fragments of residues within 3 Å of the analog. This gave a 3.2 ppm downfield shift for the CF3 group in the (F6)(Na+) E(Q)2AP complex relative to (F6)(Na+)E(Ain). A second chemical shift calculation was performed on the isolated F6 ligand from each of the optimized structures. In the absence of the surrounding residue fragments, the CF3 group shifted upfield by 12.1 ppm and 12.2 ppm for the F6 ligands from (F6)(Na+)E(Ain) and (F6)(Na+) E(Q)2AP, respectively, leaving their difference essentially unchanged. The calculated downfield shift of 3.2 ppm is larger than the experimentally observed 1.07 ppm downfield shift, but is consistent with the interpretation that the change in chemical shift for F6 is due primarily to a conformational change in the α-site ligand as the microenvironment surrounding F6 is perturbed. In general, one would expect that changes in the microenvironment alone could account for changes in fluorine chemical shifts of this magnitude, although in this case it appears that the ligand structural change plays the dominant role.

Identification of Global Conformations by Single Crystal X-Ray Structure Determinations

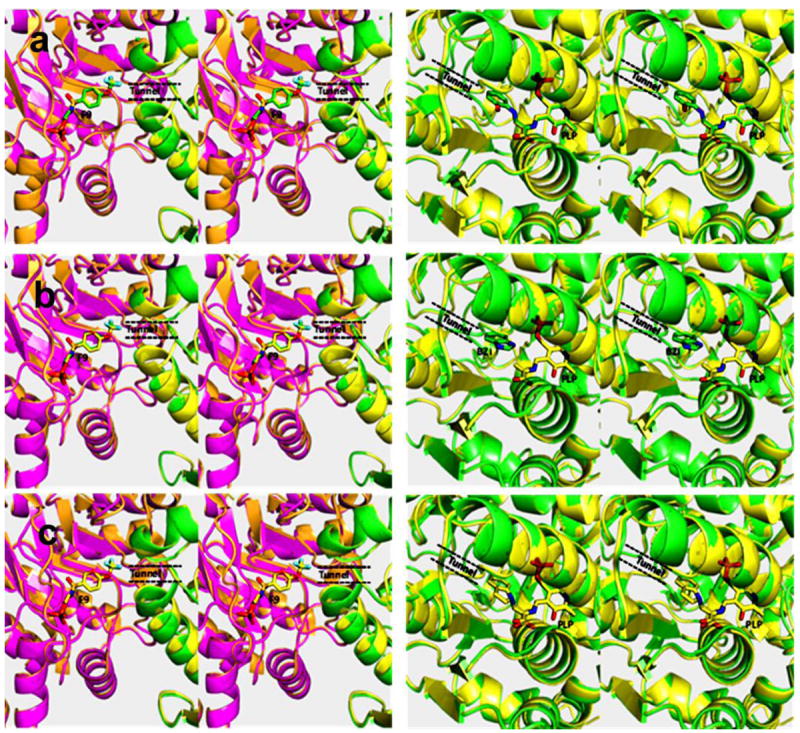

To more fully explore the relationship among global subunit conformation states, the binding of ligands to the α-site, and the chemical state of the β-site, the x-ray crystal structures of four F9 tryptophan synthase complexes and one F6 complex with different chemical states of the β-subunit were solved (Table 1; Figure 5). While the detailed analysis of these structures will be presented elsewhere, the analysis of the global conformational states of these structures is presented in Figure 5. Relatively high resolution structures (1.30 to 1.77 Å; Table 1) were obtained for the following complexes:48-51 (F9)(Cs+)E(Ain); (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A); (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A)(BZI); (F6)(Na+)E(Q)2AP and (F9)(Cs+)E(Q)2AP. BZI is a close structural analogue of indole, but does not react with the α-aminoacrylate intermediate;68 2-AP reacts with E(A-A) to form a stable, tightly-bound quinonoidal species.27 The (F6)(Na+)E(Q)2AP and (F9)(Cs+)E(Q)2AP complexes are stable analogues of the quinonoidal intermediates, E(Q)2 and E(Q)3 formed in Stage II of the β-reaction (Scheme 1). The binding of Cs+, F9 and BZI to tryptophan synthase strongly shift the distribution of intermediates formed in Stage I of the β-reaction in favor of the α-aminoacrylate intermediate. The binding of BZI to (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A) gives a complex that is predicted to be a close structural analogue of the corresponding (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A)(indole) complex. As will be presented elsewhere, this prediction is substantiated by the detailed analysis of the (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A)(BZI) complex.

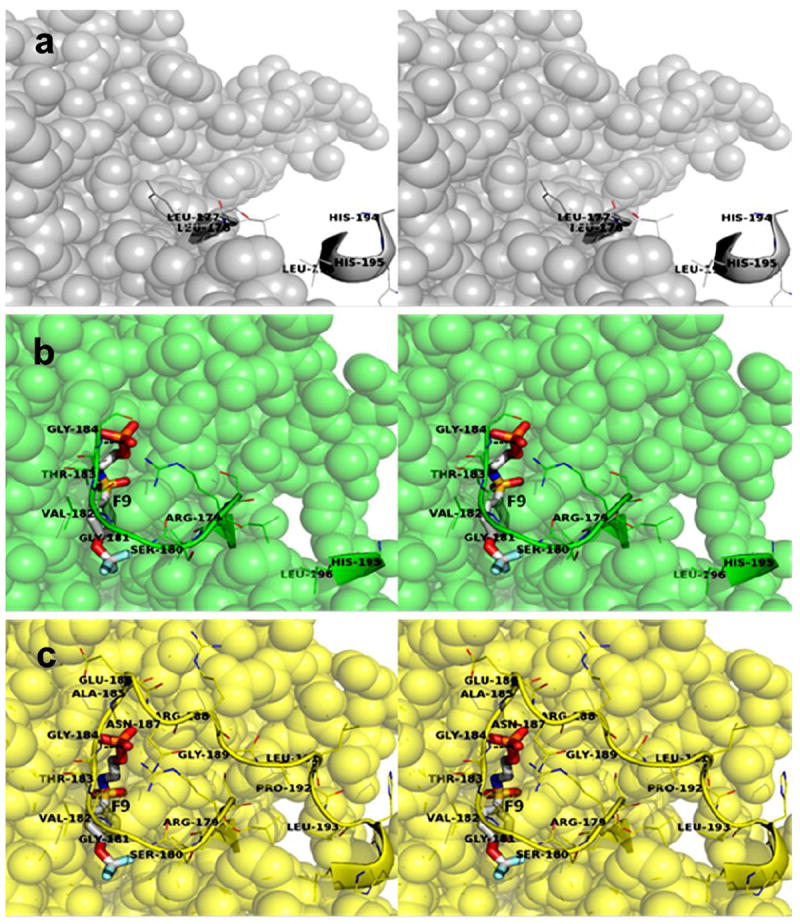

Figure 5.

Stereo views comparing the global conformations of the (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A), (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A)(BZI), and (F9)(Cs+)E(Q)2AP complexes (PDB accession codes 4HN4; 4HPX; and 4HPJ respectively). Each pair of panels (left and right) shows the cartoon ribbon structure of (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A) overlaid on the structure of another complex. Each panel on the left is a view into the α-site showing a stick rendering of F9, an indication of the tunnel at the α-β subunit interface, and a small portion of the β-subunits (green and yellow cartoon ribbons). Each panel on the left is a view into the β-site showing the PLP moieties as sticks. Color schemes: (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A) α-subunit magenta, β-subunit yellow; (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A)(BZI) and (F9)(Cs+)E(Q)2AP α-subunit orange, β-subunit green. Ligand color scheme: The ligand C atoms of the (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A) structure are colored yellow, other atoms are CPK colors. The ligand C atoms of the other structures are colored green, other ligand atoms are CPK colors. Notice that these sequence alignments show that, within experimental error, there is virtually no deviation of the positions of the Cα atoms.

The designation of global conformations as either open or closed for the α- and β- subunits is based on the following criteria: α-subunits were judged to be either open or closed depending on the extent of disorder observed for αL6. Open α-subunits exhibit 6 or more disordered residues, closed α-subunits typically exhibit two or fewer disordered residues. Open β-subunits lack a salt bridge between βArg141 and βAsp305 and present an open pathway from solvent directly into the β-catalytic site; closed β-subunits are characterized by a hydrogen-bonded salt-bridge between βArg141 and βAsp305. In closed β-subunit structures, there is no obvious pathway for substrates or analogues from solution directly into the β-site. The closed β-subunit conformation is further characterized by a movement of β-subunit residues 102-189 (the COMM domain) which positions the βArg141-βAsp305 salt bridge directly over the opening into the β-site.11, 14 As anticipated, (F9)(Cs+)E(Ain) exhibits a closed conformation for the α-subunits and an open conformation for the β-subunits.44 The structures of (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A); (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A)(BZI); (F6)(Na+)E(Q)2AP; and (F9)(Cs+)E(Q)2AP all exhibit closed conformations for the α- and β-subunits.

DISCUSSION

Allosteric Conformation States

The regulation of protein function via allosteric interactions continues to be a challenging and intriguing area of investigation. In the tryptophan synthase system, allosteric regulation of substrate channeling functions to prevent the escape of the common intermediate, indole.8,11,14 This sequestering of indole during the catalytic cycle of the αβ-reaction (Scheme 1 and Chart 1a) involves the switching of the α- and β-subunits of the α2β2 tetrameric protein between alternative conformational states designated as open and closed. The designations of subunit conformations as open or closed refers to the access of substrates and substrate analogues into the α- and β-active sites from solution (Chart 1a).8,11,14,18,31 Kinetic measurements indicate the open and closed conformations of the β-subunit give low and high activity forms of the α-subunit, respectively,31,32,33,35 Ngo et al.39 found that the closed forms of the α-subunit activate conversion of the internal aldimine to the α-aminoacrylate intermediate, the rate determining step in Stage I of the β-reaction11 (Scheme 1 and Chart 1a).

The mechanism in Chart 1a is consistent with the participation of at least 2 conformation states, open and closed, during the αβ-reaction cycle. However, the number of global subunit conformation states involved in the tryptophan synthase catalytic cycle (Chart 1a) has previously not been established. The evidence for open and closed states implies each αβ dimeric unit of the tetrameric enzyme can exist in at least four conformation states: αOβO; αCβO; αOβC; αCβC, where superscripts O and C designate open and closed conformations respectively.

There are at least nine chemical steps in the β-reaction (Scheme 1b, Stages I and II). It has been proposed that for catalysis of the individual chemical steps in the β-site catalytic cycle, the β-site must go through a series of localized conformational transitions that render the site complementary to the structure of each transition-state along the catalytic path11,19,20,47,75 These conformational transitions must be local, but could be coupled to global transitions. Consequently, it cannot be assumed that there are only four global protein conformation states relevant to catalysis and allosteric regulation of tryptophan synthase.

Conformation States in Tryptophan Synthase and Their Relationship to Catalysis and Regulation Based on X-Ray Crystal Structures

The Protein Data Bank contains more than 50 x-ray crystal structures of S. typhimurium tryptophan synthase and its complexes with substrates and substrate analogues. The majority of these structures correspond to αOβO or αCβO global subunit conformations.8,17,38,42,44,45,76,77 The propensity of the enzyme to crystallize in the global αOβO and αCβO conformations appears due to the influence of crystal packing forces. Only a few structures have been determined exhibiting αOβC or αCβC global subunit conformations.39,43,46-52,58 However, this structural data base is consistent with the existence of at least four global conformation states (i.e., αOβO, αCβO, αOβC and αCβC).

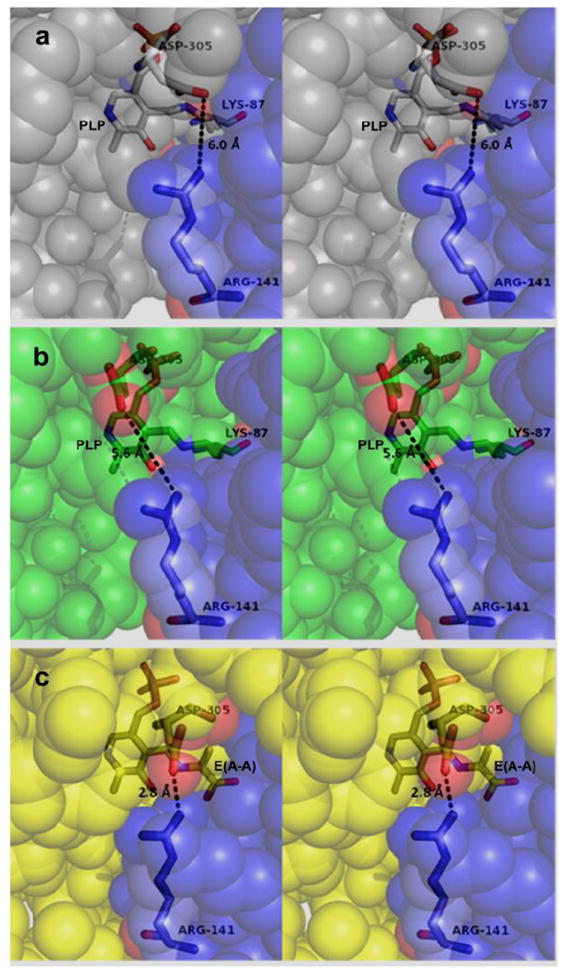

Table 2 summarizes the assignments of the global conformations based on x-ray crystal structure results for each of the tryptophan synthase complexes directly relevant to this work, and examples of complexes with global open and closed structures are shown in Figures 5-7.

Table 2.

Assignment of Global Conformation States from x-Ray Crystal Structures

| Na+ Complexes; PDB accession no. | Missing/disordered residues in Loop αL6 | βArg141-βAsp305 Salt Bridge | Subunit Conformation (αβ-dimeric unit) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (F6)(Na+)E(Ain) 2CLE |

179-193 (15 Res) | No | αOβO | Ngo et al.38 |

| (F9)(Na+)E(Ain) 2CLI |

185-193 (9 Res) | No | αOβO | Ngo et al.38 |

| (F6)(Na+)E(Aex1) 2CLM |

179-193 (15 Res) | No | αOβO | Ngo et al.39 |

| (F9)(Na+)E(Aex1) 2CLL |

185-194 (10 Res) | No | αOβO | Ngo et al.39 |

| (F6)(Na+)E(Q)2ap 4KKX |

0 | Yes | αCβC | Hilario et al.52 |

| Cs+Complexes PDB accession no. |

||||

| (F9)(Cs+)E(Ain) 4HT3 |

0 | No | αCβO | Hilario et al.48 |

| (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A) 4HN4 |

0 | Yes | αCβC | Hilario et al.49 |

| (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A)(BZI) 4HPX |

0 | Yes | αCβC | Hilario et al.50 |

| (F9)(Cs+)E(Q)indoline 3PR2 |

0 | Yes | αCβC | Lai et al.47 |

| (F9)(Cs+)E(Q)2AP 4HPJ |

0 | Yes | αCβC | Hilario et al.51 |

Figure 7.

Stereo views comparing the β-sites of the (Na+)E(Ain), (F6)(Na+)E(Ain), and (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A) complexes. a: (Na+)E(Ain) (PDB accession code KFK): Residues β141 and β305 are too far apart in this structure to form a salt bridge, and the access of substrates/analogues from solution into the β-site is not hindered by steric or electronic interactions. Color scheme: β-subunit residues are light blue spheres (COMM domain) and gray spheres. The PLP Schiff base with βLys87, βArg141 and βAsp305 are shown as sticks. b: (F6)(Na+)E(Ain): Residues βArg141 and βAsp305 are too far apart to form a salt bridge (PDB accession code 2CLI) and the opening from solution into the β-site is not hindered by steric or electronic interactions. Color scheme: β-subunit residues are light blue spheres (COMM domain) and green spheres. 7c: (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A) (PDB accession code 4HN4): Residues βArg141 and βAsp305 form a hydrogen-bonded salt bridge which provides a steric and electrostatic barrier preventing the access of small molecules from solution.

In Table 2, the assignments of α-subunit conformation are based on the extent of disorder in loop αL6, the assignments of β-subunit conformation are based on the absence or presence of the βArg141-βAsp305 salt bridge as the primary criterion. All of the subunit classifications were confirmed by subunit structure alignments using PyMol (viz. Figure 5).

Trifluoromethyl-Substituted IGP Analogues Are Probes of β-Site Conformation

19F substituted ligands bound to protein sites often are in slow exchange with the free ligand (on the NMR time scale),59-67 and this appears true for the binding of α-site ligands, F6 and F9, to tryptophan synthase. Solution studies to investigate the kinetic effects of F6 and F9 on chemical steps in the β-reaction, and the x-ray structures of the complexes formed with F6 and F9 have established that these ligands are good analogues of the tryptophan synthase-IGP complex.14,38,39,47-52 Both F6 and F9 bind in the IGP site of the α-subunit with orientations that place the phosphoryl groups into the IGP phosphoryl group subsite, and the aromatic ring moieties of F6 and F9 overlap with the IGP indolyl ring subsite.38,39 The trifluoromethyl carbon atoms of bound F6 and F9 are located in the tunnel at the α-β subunit interface (Figures 6 and 7), approximately 29.8 Å and 29.5 Å, respectively, from the C-4’ carbon of PLP.

Figure 6.

Stereo views comparing of the α-sites of the (Na+)E(Ain), (F9)(Na+)E(Ain), and (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A) complexes. a: (Na+)E(Ain) (PDB accession code KFK): Residues α178-α194 (αL6) are completely disordered in this structure and the α-site is completely open. Color scheme: α-subunit residues are gray spheres, residues α176, α177 and α194-α196 are shown as cartoon ribbons. b: (F9)(Na+)E(Ain) (PDB accession code 2CLI): Residues α185-α194 are completely disordered in this structure and the α-site is open to solution at the ligand phosphoryl. Color scheme: α-subunit residues are gray spheres, residues are green spheres, residues α179-α184 and α195, and α196 are shown as cartoon ribbons. F9 is shown as a stick structure with CPK colors (F pale blue, C gray, N blue, O red, S yellow, P orange). c: (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A) (PDB accession code 4HN4): No residues in αL6 are disordered and the α-site is completely closed. Color scheme: α-subunit residues are yellow spheres, residues α179-α193 are shown as a cartoon ribbon. F9 is shown as a stick structure with CPK colors.

The assignments of global subunit conformations for the complexes examined in this study are summarized in Table 3. These assignments are based on the chemical shifts observed in the F6 and F9 complexes (Figures 1-3, Table 3, also Figures S1 and S2).

Table 3.

Assignment of Global Conformation States from 19F NMR Measurements

| F6 Na+Complexes | Ligands and Substrates | Chemical Shifts of the 19F NMR Peaks (ppm) | Conformation Assignments | Figure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (F6)(Na+)E(Ain) | F6 | -56.52 ± 0.01 | αOβO | Figure 1 | |

| (F6))(Na+)E(A-A) | F6; L-Ser | -55.45 ± 0. 01 | αCβC | Figure 1 | |

| (F6))(Na+)E(A-A)(BZI) | F6; L-Ser; BZI | -55.45 ± 0. 01 | αCβC | Figure 2 | |

| (F6))(Na+)E(Q)Indoline | F6; L-Ser; Indoline | -55.45 ± 0. 01 | αCβC | Figure 2 | |

| (F6)E(Q)Aniline | F6; L-Ser; Aniline | -55.45 ± 0. 01 | αCβC | Figure 2 | |

| (F6))(Na+)E(Q)2AP | F6; L-Ser; 2-Aminophenol | -55.45 ± 0. 01 | αCβC | Figure 4 | |

| (F6))(Na+)E(Q)3 + (F6)E(Aex)2 | F6; L-Trp | -56.52 ± 0.01 | -55.45 ± 0. 01 | αCβC and αOβO or αOβC | Figure S1 |

| (F6))(Na+)E(Q)L-His + (F6)E(Aex)L-His | F6; L-His | -56.52 ± 0.01 | -55.45 ± 0. 01 | αCβC and αOβO or αOβC | Figure S2 |

| Cs+ F6 Complex | |||||

| (F6))(Cs+)E(Q)L-His | F6; L-His | -55.45 ± 0. 01 | Figure S2 | ||

| Na+ F9 Complexes | |||||

| (F9))(Na+)E(Ain) | F9 | -56.79 ± 0.01 | Figure 5 | ||

| (F9))(Na+)E(A-A) | F9; L-Ser | -56.91 ± 0. 01 | Figure 5 | ||

| (F9))(Na+)E(A-A)(BZI) | F9; L-Ser; BZI | -56.91 ± 0. 01 | Figure 5 | ||

| (F9))(Na+)E(Q)Indoline | F9; L-Ser; Indoline | -56.91 ± 0. 01 | Figure 5 | ||

| (F9)(Na+)E(Q)2AP | F9; L-Ser; 2-Aminophenol | -56.91 ± 0. 01 | Figure 5 | ||

The (F9)(Na+)E(Ain) complex gives a bound peak with a chemical shift of -56.91 ± 0.01ppm (Figure 3; Table 3). The x-ray crystal structures of the (F6)(Na+)E(Ain) and (F9)(Na+)E(Ain) complexes38 show that both the α- and the β-subunits have the open conformation (Figures 6 and 7). Disorder in Loop αL6 of the α-subunit and the absence of a salt bridge between βArg141 and βAsp305 are clear signatures of the open global conformations of the α- and β-subunits, respectively11,14,38,39 (Table 2). In the (F6)(Na+)E(Ain) and (F9)(Na+)E(Ain) complexes (respectively, PDB accession nos. 2CLL and 2CLI; Ngo et al.38), ten residues of loop αL6 are disordered, and β-subunit residues βArg141 and βAsp305 are too distant to form a salt bridge (Figures 6 and 7). The 19F NMR spectra of F9 bound to (Na+)E(A-A), (Na+)E(A-A)(BZI), (Na+)E(Q)indoline and (Na+)E(Q)2AP each give bound peaks with the same chemical shift (-56.79 ± 0.01 ppm) (Figure 3; Table 3). The x-ray crystal structures of the (F9(Cs+)E(A-A), (F9)(Cs+)E(A-A)(BZI), (F9)(Cs+)E(Q)indoline, (F6)(Na+)E(Q)2AP and (F9)(Cs+)E(Q)2AP complexes 47-51 (Figure 5) all show the α- the β-subunits have the same closed global subunit conformations. Consequently, we propose that the switch from the open β-subunit conformation of (F9)(Na+)E(Ain) to the closed β-subunit conformations of the Na+ or Cs+ forms of (F9)E(A-A), (F9)E(A-A)(BZI), (F9)E(Q)indoline and (F9)E(Q)2AP is signaled by a shift in the bound F9 peak from -56.79 ± 0.01 ppm to -56.91 ± 0.01 ppm. The chemical shifts of the F6 complexes behave similarly (Figures 1 and 2; Table 3): The (F6)(Na+)E(Ain) complex is characterized by a chemical shift of -56.52 ± 0.01 ppm; whereas the F6 complexes with (Na+)E(A-A), (Na+)E(A-A)(BZI), (Na+)E(Q)indoline, (Na+)E(Q)aniline and (F6)(Na+)E(Q)2AP all give the same chemical shift (-55.45 ± 0.01 ppm). The reasonable conclusion is that under the experimental conditions of these NMR experiments only two conformations of the αβ-dimeric unit are observed, open and closed, and that the (Na+)E(Ain) and (Na+)E(Aex) species favor the open conformation, while the Na+ and Cs+ complexes of E(Q) and E(A-A) species favor the closed conformation. This conclusion is further supported by the observation that the substitution of Na+ for Cs+ alters peak areas but does not alter the chemical shifts of the bound F6 or F9 complexes (Figure S2).

The 19F NMR results presented summarized in Table 3 (taken from Figures 1-3 and S1 and S2) establish that complexes of F6 and F9 with the α-subunit of tryptophan synthase exhibit 19F NMR peaks that are sensitive to the open and closed conformations of the β-subunit (Figures 1-3 and S1 and S2). With either ligand, only two bound states are observed. The invariance of the chemical shifts observed for the bound states of F6 or F9 as a function of ligand concentration (Figures 1-3 and S1 and S2) and the chemical state of the β-site (i.e., the α-aminoacrylate intermediate with or without BZI bound, and six different quinonoid intermediates, Table 3) is fully consistent with the conclusion that all of these complexes are in slow exchange with the free ligand. Of greater interest is the finding that the chemical shifts of bound F6 or F9 are sensitive to the conformational state of the β-subunit, but not to the chemical nature of the β-site intermediate. Conversely, while the distributions of open and closed conformation states are sensitive to the binding of F6 or F9, we conclude that the global conformations of the α- and β-subunits do not depend on the structures of F6 or F9.

Allosteric Switching Between Global Conformations as a Function of the β-Site Chemical State

The αβ-reaction cycle depends upon the switching of subunits between the open and closed global conformation states (Figures 1-3, 5-7 and S1 and S2). Assuming there are only two global conformation states of each subunit, then each chemical step in the β-reaction, a priori, involves an ensemble of four interconverting conformations of the αβ-dimeric unit. Table 4 summarizes these global conformation states as a function of the chemical state of the β-site and ligand-bound species along the tryptophan synthase αβ-reaction pathway. (Based on the x-ray structure comparisons (viz., Figure 7a), the α-subunit of the (Na+)E(Ain) species (first and last rows) appears to exist in a different open conformation here designated as α*.) Each row lists the four possible, interconverting, global conformations for the αβ-dimeric unit for each β-site chemical intermediate. It is our hypothesis that the switching between global conformational states as the β-site progresses from one intermediate to the next, provides the allosteric control that results in the synchronizing of the catalytic cycles of the α- and β-sites and prevents the escape of indole, the channeled intermediate. Early studies18,31-33,35 established that α-sites of the E(Ain), E(GD) and E(Aex) forms of the enzyme reside in a low activity state, whereas conversion of E(Aex1) to E(A-A) activates the α-site ~28-fold, and conversion of E(Q3) to E(Aex2) deactivates the α-site by a similar factor (viz., Chart 1a). Furthermore, binding of IGP analogues39 activates the conversion of E(Aex1) to E(A-A) by ~10-fold in Stage I of the β-reaction.

Table 4.

Global Conformation States as a Function of the Chemical State of the β-Site and Ligand-Bound Species Along the Tryptophan Synthase αβ-Reaction Pathway

| Substrate | Global Conformation States | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I | ||||

| α*βC(Ain) | α*βC(Ain) | α*βO(Ain) | α*βO(Ain) | |

| L-Ser | ||||

| αOβC(GD1) | αCβC(GD1) | αCβO(GD1) | αOβO(GD1) | |

| αOβC(Aex1) | αCβC(Aex1) | αCβO(Aex1) | αOβO(Aex1) | |

| αOβC(Q1) | αCβC(Q1) | αCβO(Q1) | αOβO(Q1) | |

| α O β C (A-A) | αCβC(A-A) | αCβO(A-A) | αOβO(A-A) | |

| Stage II | ||||

| IGP | ||||

| (IGP)αOβC(A-A) | (IGP)αC βC (A-A) | (IGP)αCβO(A-A) | (IGP)αOβO(A-A) | |

| (G3P)αOβC(A-A)(Indole) | (G3P)αC βC (A-A)(Indole) | (G3P)αCβO(A-A)(Indole) | (G3P)αOβO(A-A)(Indole) | |

| (G3P)αOβC(Q2/3) | (G3P)αC βC (Q2/3) | (G3P)αCβO(Q2/3) | (G3P)αOβO(Q2/3) | |

| (G3P)αOβC(Aex2) | (G3P)αC βC (Aex2) | (G3P)αCβO(Aex2) | (G3P)αOβO(Aex2) | |

| G3P | αOβC(Aex2) | αCβC(Aex2) | αC βO(Aex2) | αOβO(Aex2) |

| αOβC(GD2) | αCβC(GD2) | αCβO(GD2) | αOβO(GD2) | |

| L-Trp | α*βC(Ain) | α*βC(Ain) | α*βO(Ain) | α*βO(Ain) |

The structural and kinetic information available is consistent with the conclusion that the open conformations of the α- and β-subunits either have low, or no catalytic activity, while the closed conformations are active.14 Where the evidence is sufficient to make a prediction, Table 4 shows the predominating species in bold italics for each step. Where we are able to correlate conformation state with catalytic activity in Table 4, it appears that the chemical transformations occur via closed global conformations, while the transfer of substrates/products between solution and the catalytic sites occurs via open global conformations. The transfer of indole between the α- and β-sites occurs within αβ-dimeric units with the closed conformations, thus preventing the escape of indole.18,31-33,35-37

Under physiological conditions, there is a significant pool of L-Ser present in bacterial cells. This pool dictates that the (quasi-stable) α-aminoacrylate species, α° βC(A-A), produced in Stage I of the β-reaction is the predominating form of the bienzyme complex (Scheme 1, Chart 1a and Table 4). In response to the demands of the cell for L-Trp, the enzymes of the Trp operon convert phosphoenolpruvate and erythrose 4-phosphate through a series of metabolites to give IGP. IGP then binds to the α-site of tryptopan synthase where it is cleaved to indole and G3P, initiating Stage II of the β-reaction. Upon transfer of indole from the α-site to the β-site, via the interconnecting tunnel, reaction proceeds in Stage II via the closed conformation of the αβ-dimeric unit to give the L-Trp quinonoid species, (G3P)αCβC(Q2/3). Conversion of the quinonoid species to (G3P)αCβC(Aex2) and the switch to the quasi-stable α°βC(Aex2) releases G3P. Conformational interconversions between inactive and active forms then allow conversion of the L-Trp external aldimine to the L-Trp gem diamine, followed by release of L-Trp and formation of the internal aldimine.

As depicted in Table 4, the switching between global conformation states is triggered by the binding/dissociation of IGP and G3P to the α-site, and by the interconversion among covalent intermediates at the β-site. The free energy differences between the different global conformations are necessarily small, but nevertheless can exert significant effects on the kinetics of ligand exchange between site and solution, and on the kinetics of chemical steps in the α- and β-reactions. The residual catalytic activity of the α-site when the β-site is in the form of E(Ain), E(GD) or E(Aex)31,35 likely arises from the presence of a small fraction of the closed α-subunit. Based on rapid kinetic studies, Lane and Kirschner (1983) proposed the existence of two forms of the α-aminoacrylate, and this has been confirmed by subsequent kinetic studies.19,20,24,25,27 Comparison of the x-ray structures of E(Aex1) with E(A-A) and E(Q) species38,39,45,47-52 show that the catalytic residues at the active site of the E(Aex1) complex in the open β-subunit conformation are incorrectly positioned for catalysis, whereas these residues are correctly positioned for catalysis in the E(A-A) and E(Q) species where both the α- and β-subunits have the closed conformation.11,14,47-52

In summary, the evidence discussed in this study is fully consistent with an MWC-like allosteric mechanism for the regulation of catalysis and substrate channeling in the tryptophan synthase system where the ligand-mediated switching between a small, finite number of global subunit conformations accounts for the allosteric behavior of the system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Grant Number R01GM097569 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute Of General Medical Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- α and β

the subunits of tryptophan synthase

- IGP

3-indole-D-glycerol 3’-phosphate

- G3P

D-glycerol 3-phosphate

- PLP

pyridoxal 5’-phosphate

- MWC

the concerted model for allostery

- KNF

the induced-fit model for allostery

- F6

N-(4’-trifluoromethoxybenzoyl)-2-aminoethyl phosphate

- F9

N-(4’-trifluoromethoxybenzenesulfonyl)-2-aminoethyl phosphate

- BZI

-

Benzimidazole.

Tryptophan synthase intermediates resulting from reaction of substrates L-Ser and indole with PLP bound in the form of the Schiff-base internal aldimine E(Ain) formed with βLys87 to yield intermediates

- E(GD1)

the geminal diamine

- E(Aex1)

the external aldimine

- E(Q1)

the L-Ser quinonoid

- E(A-A)

the α-aminoacrylate

- E(Q2) and E(Q3)

the L-Trp quinonoids

- E(Aex2)

the L-Trp external aldimine

- E(GD2)

the L-Trp germinal diamine

- αL6

α-subunit loop 6 comprised of residues α179-α193

- COMM domain

-

β-subunit residues β102-β189.

Enzyme forms are designated as follows: (α-site ligand)(movalent cation) E(β-site intermediate)(β-site ligand)

For example, the complex of F6 and BZI with the Na+ form of the α-aminoacrylate intermediate is referred to as (F6)(Na+)E(A-A)(BZI). Global subunit conformations are designated by the superscripts O, open or C, closed

For example, the closed αβ-dimeric unit of (G3P)E(A-A)(indole) is designated as (G3P)αCβC(A-A)(indole).

- 2-AP

2-aminophenol

- TEA

triethanolamine

- ANS

8-anilino-1-naphthalene sulfonate

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Supporting information consisting of 19F NMR spectra for the complexes formed in the reactions of L-Trp and L-His with the F6 complexes of E(Ain) are presented along with spectra comparing the effects of Na+ and Cs+ on the species formed in the reaction of L-His with E(Ain). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Monod J, Wyman J, Changeux JP. On the nature of allosteric transitions: a plausible model. J Mol Biol. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant G. Allosteric regulation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;519:67–231. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.02.014. Guest editor. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kantrowitz ER. Allostery and cooperativity in Escherichia coli aspartate transcarboxylase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;519:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guerra AJ, Giedroc DP. Metal site occupancy and allosteric switching in bacterial metal sensor proteins. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;519:210–222. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batiza AF, Rayment I, Kung C. Channel gate! Tension, leak and disclosure. Structure. 1999;7:99–103. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thoden JB, Holden HM, Wesenberg G, Raushel FM, Rayment I. Structure of carbamoyl phosphate synthetase: a journey of 96 A from substrate to product. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6305–6316. doi: 10.1021/bi970503q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Negrutskii BS, Deutscher MP. Channeling of aminoacyl-tRNA for protein synthesis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4991–4995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan P, Woehl E, Dunn MF. Protein architecture, dynamics, and allostery in tryptophan synthase channeling. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 1997;22:22–27. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)10066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miles EW, Rhee S, Davies DR. The molecular basis of substrate channeling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12193–12196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang X, Holden HM, Raushel FM. Channeling of substrates and intermediates in enzyme-catalyzed reactions. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:149–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn MF, Niks D, Ngo H, Barends TRM, Schlichting I. Tryptophan synthase: the workings of a channeling nanomachine. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2008;33:254–264. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barends TRM, Dunn MF, Schlichting I. Tryptophan synthase, an allosteric molecular factory. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2008;12:619–625. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raboni S, Bettati S, Mozzarelli A. Tryptophan synthase: a mine for enzymologists. Cellular and Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:2391–2403. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0028-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunn MF. Allosteric regulation of substrate channeling and catalysis in the tryptophan synthase bienzyme complex. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012a;519:154–166. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn MF. The role of monovalent cations in tryptophan synthase catalysis and regulation of substrate channeling. in. Encyclopedia of Metalloproteins 2012b [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yanofsky C, Crawford IP. Tryptophan synthase. In: Boyer PD, editor. The Enzymes. Academic Press; New York: 1972. pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyde CC, Padlan EA, Ahmed SA, Miles EW, Davies DR. Three dimensional structure of the tryptophan synthase multienzyme complex from Salmonella typhimurium. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:17857–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunn MF, Aguilar V, Brzovic P, Drewe WF, Jr, Houben KF, Leja CA, Roy M. The tryptophan synthase bienzyme complex transfers indole between the α- and β-sites via a 25-30 Å long tunnel. Biochemistry. 1990;29:8598–8607. doi: 10.1021/bi00489a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drewe WF, Jr, Dunn MF. Detection and identification of intermediates in the reaction of L-serine with Escherichia coli tryptophan synthase via rapid-scanning ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1985;24:3977–3987. doi: 10.1021/bi00336a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drewe WF, Jr, Dunn MF. Characterization of the reaction of L-serine and indole with Escherichia coli tryptophan synthase via rapid-scanning ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1986;25:2494–2501. doi: 10.1021/bi00357a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peracchi A, Mozzarelli A, Rossi GL. Monovalent cations affect dynamic and functional properties of the tryptophan synthase α2β2 complex. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9459–9465. doi: 10.1021/bi00029a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woehl EU, Dunn MF. Monovalent metal ions play an essential role in catalysis and intersubunit communication in the tryptophan synthase bienzyme complex. Biochemistry. 1995a;34:9466–9476. doi: 10.1021/bi00029a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woehl EU, Dunn MF. The roles of Na+ and K+ in pyridoxal phosphate enzyme catalysis. Coord Chem Rev. 1995b;144:147–197. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woehl EU, Dunn MF. Mechanisms of monovalent cation action in enzyme catalysis: the first stage of the tryptophan synthase β-reaction. Biochemistry. 1999a;38:7118–7130. doi: 10.1021/bi982918x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woehl EU, Dunn MF. Mechanisms of monovalent cation action in enzyme catalysis: the tryptophan synthase α-, β-, and αβ-reactions. Biochemistry. 1999b;38:7131–7141. doi: 10.1021/bi982919p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weber-Ban E, Hur O, Bagwell C, Banik U, Yang L-H, Miles EW, Dunn MF. Investigation of allosteric linkages in the regulation of tryptophan synthase: The roles of salt bridges and monovalent cations probed by site-directed mutation, optical spectroscopy, and kinetics. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3497–3511. doi: 10.1021/bi002690p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dierkers AT, Niks D, Schlichting I, Dunn MF. Trptophan synthase: structure and function of the monovalent cation site. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10997–11010. doi: 10.1021/bi9008374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koshland DE, Jr, Némethy G, Filmer D. Comparison of experimental binding data and theoretical models in proteins containing subunits. Biochemistry. 1966;5:365–368. doi: 10.1021/bi00865a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirschner K, Lane AN, Strasser AWM. Reciprocal communication between the lyase and synthase active-sites of the tryptophan synthase bienzyme complex. Biochemistry. 1991;30:472–478. doi: 10.1021/bi00216a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson KS, Miles EW, Johnson KA. Serine modulates substrate channeling in tryptophan synthase - A novel intersubunit triggering mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8020–8033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brzovic PS, Ngo K, Dunn MF. Allosteric interactions coordinate catalytic activity between successive metabolic enzymes in the tryptophan synthase bienzyme complex. Biochemistry. 1992a;31:3831–3839. doi: 10.1021/bi00130a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brzovic PS, Sawa Y, Miles EW, Dunn MF. Evidence that mutations in a loop region of the α-subunit inhibit the transition from an open to a closed conformation in the tryptophan synthase bienzyme complex. J Biol Chem. 1992b;267:13028–13038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brzovic PS, Hyde CC, Miles EW, Dunn MF. Characterization of the functional role of a flexible loop in the α-subunit of tryptophan synthase from S. Typhimurium by rapid-scanning stopped-flow spectroscopy and site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 1993;32:10404–10413. doi: 10.1021/bi00090a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pan P, Dunn MF. β-site covalent reactions trigger transitions between open and closed conformations of the tryptophan synthase bienzyme complex. Biochemistry. 1995;35:5002–5013. doi: 10.1021/bi960033k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leja CA, Woehl EU, Dunn MF. Allosteric linkages between β-site covalent transformations and α-site activation and deactivation in the tryptophan synthase bienzyme complex. Biochemistry. 1995;34:6552–6561. doi: 10.1021/bi00019a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harris RM, Dunn MF. Intermediate trapping via a conformational switch in the Na+ -activated tryptophan synthase bienzyme complex. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9982–9990. doi: 10.1021/bi0255672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harris RM, Ngo H, Dunn MF. Synergistic effects on escape of a ligand from the closed tryptophan synthase bienzyme complex. Biochemistry. 2005;44:16886–16895. doi: 10.1021/bi0516881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ngo H, Harris R, Kimmich N, Casino P, Niks D, Blumenstein L, Barends TR, Kulik V, Weyand M, Schlichting I, Dunn MF. Synthesis and characterization of allosteric probes of substrate channeling in the tryptophan synthase bienzyme complex. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7713–7727. doi: 10.1021/bi700385f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ngo H, Kimmich N, Harris R, Niks D, Blumenstein L, Kulik V, Barends TR, Schlichting I, Dunn MF. Allosteric regulation of substrate channeling in tryptophan synthase: Modulation of the L-serine reaction in stage I of the β-reaction by α-site ligands. Biochemistry. 2007b;46:7740–7753. doi: 10.1021/bi7003872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phillips RS, McPhie P, Miles EW, Marchal S, Lang R. Quantitative effects of allosteric ligands and mutations on conformational equilibria in Salmonella typhimurium tryptophan synthase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;470:8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fatmi MQ, Ai R, Chang CA. Synergistic Regulation and ligand-induced conformational changes of tryptophan synthase. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9921–9931. doi: 10.1021/bi901358j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rhee S, Parris KD, Ahmed SA, Miles EW, Davies DR. Exchange of K+ or Cs+ for Na+ induces local and long-range changes in the three-dimensional structure of the tryptophan synthase alpha2beta2 complex. Biochemistry. 1996;35:4211–4221. doi: 10.1021/bi952506d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rhee S, Parris KD, Hyde CC, Ahmed SA, Miles EW, Davies DR. Crystal structures of a mutant (βK87T) tryptophan synthase α2β2 complex with ligands bound to the active sites of the α- and β-subunits reveal ligand-induced conformational changes. Biochemistry. 1997;36:7664–7680. doi: 10.1021/bi9700429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sachpatzidis A, Dealwis C, Lubetsky JB, Liang PH, Anderson KS, Lois E. Crystallographic studies of phosphonate-based α-reaction transition-state analogues complexed to tryptophan synthase. Biochemistry. 1999;38:12665–12674. doi: 10.1021/bi9907734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kulik V, Weyand M, Seidel R, Niks D, Arac DMF, Dunn MF, Schlichting I. On the role of αThr183 in the allosteric regulation and catalytic mechanism of tryptophan synthase. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:677–690. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barends TRM, Domratcheva T, Kulik V, Blumenstein L, Niks D, Dunn MF, Schlichting I. Structure and mechanistic implications of a tryptophan synthase quinonoid intermediate. ChemBiochem. 2008;9:1024–1028. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lai J, Niks D, Wang Y, Domratcheva T, Barends TRM, Schwarz F, Olsen RA, Elliott DW, Fatmi MQ, Chang CA, Schlichting I, Dunn MF, Mueller LJ. X-ray and NMR crystallography in an enzyme active site: The indoline quinonoid intermediate in tryptophan synthase. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:4–7. doi: 10.1021/ja106555c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hilario E, Niks D, Dunn MF, Mueller L, Fan L. The crystal structure of Salmonella typhimurium tryptophan synthase at 1.30 Å complexed with N-(4’-trifuloromethoxybenzenesulfonyl)-2-amino-1-ethylphosphate (F9) 2012 PDB accession no. 4HT3. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hilario E, Niks D, Dunn MF, Mueller L, Fan L. Tryptophan synthase in complex with alpha aminoacrylate E(A-A) form and the F9 inhibitor in the alpha site. 2012 PDB accession no. 4HN4. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hilario E, Niks D, Dunn MF, Mueller L, Fan L. Crystal structure of Tryptophan Synthase at 1.65 Å resolution in complex with alpha aminoacrylate E(A-A) and benzimidazole in the beta site and the F9 inhibitor in the alpha site. 2012 PDB accession no. 4HPX. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hilario E, Niks D, Dunn MF, Mueller L, Fan L. Crystal structure of tryptophan synthase at 1.45 Å resolution in complex with 2-aminophenol quinonoid in the beta site and the F9 inhibitor in the alpha site. 2012 PDB accession no. 4HPJ. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hilario E, Niks D, Dunn MF, Mueller L, Fan L. Crystal structure of Tryptophan Synthase from Salmonella typhimurium with 2-aminophenol quinonoid in the beta site and the F6 inhibitor in the alpha site. 2013 PDB accession no. 4KKX. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miles EW. Tryptophan synthase: structure, function, and subunit interaction. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1979;49:127–186. doi: 10.1002/9780470122945.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kirschner K, Weischet WO, Wiskocil RL. Ligand binding to enzyme complexes. In: Sund H, Blaver HG, editors. Protein-Ligand Interactions. Walter de Gruyter; Berlin: 1975. pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lane AN, Kirschner K. The mechanism of tryptophan binding to tryptophan synthase from Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1981;120:379–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb05715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lane AN, Kirschner K. The Mechanism of binding of L-serine to tryptophan synthase from Escherichia coli. Euro J of Biochem. 1983a;129:561–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lane AN, Kirschner K. The catalytic mechanism of tryptophan synthase from E. coli. Eur J Biochem. 1983b;129:571–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blumenstein L, Domratcheva T, Niks D, Ngo H, Seidel R, Dunn MF, Schlichting I. βQ114N and βT110V Mutations Reveal a Critically Important Role of the Substrate Carboxylate Site in the Reaction Specificity of Tryptophan Synthase. Biochemistry. 2007;46:14100–14116. doi: 10.1021/bi7008568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Danielson MA, Falke JJ. Use of 19F NMR to probe protein structure and conformational changes. Ann Rev Biophys Biomol Str. 1996;25:163–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.25.060196.001115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Elvington SM, Liu CW, Maduke MC. Substrate-driven conformational changes in ClC-ec1 observed by fluorine NMR. EMBO J. 2009;28:3090–3102. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dugad LB, Cooley CR, Gerig JT. NMR studies of carbonic anhydrase fluorinated benzenesulfonamide complexes. Biochemistry. 1989;28:3955–3960. doi: 10.1021/bi00435a049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gregory DH, Gerig JT. Prediction of fluorine chemical shifts in proteins. Biopolymers. 1991;31:845–858. doi: 10.1002/bip.360310705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sylvia LA, Gerig JT. NMR studies of alpha-chymotrypsin-®-1-acetamido-2-(4-fluorophenyl)ethyl-1-boronic acid complex. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1163:321–334. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(93)90169-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sylvia LA, Gerig JT. NMR studies of alpha-chymotrypsin-®-1-acetamido-2-(4-fluorophenyl)ethyl-1-boronic acid complex at pH 7. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1252:225–232. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(95)00132-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lau EY, Gerig JT. Effects of fluorine substitution on the structure and dynamics of complexes of dihydrofolate reducase (Escherichia coli) Biophys J. 1997;73:1579–1592. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78190-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bonaccio M, Ghaderi N, Borchardt D, Dunn MF. Insulin allosteric behavior: detection, identification and quantification of allosteric states via 19-F NMR. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7656–7668. doi: 10.1021/bi050392s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu JJ, Horst R, Katritch V, Stevens RC, Wüthrich K. Biased Signaling Pathways in β2-Adrenergic Receptor Characterized by 19F-NMR. Science. 2012;335:1106–1110. doi: 10.1126/science.1215802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roy M, Keblawi S, Dunn MF. Stereoelectronic control of bond formation in E. coli tryptophan synthase: Substrate specificity and the enzymatic synthesis of the novel amino acid, dihydroisotryptophan. Biochemistry. 1988;27:6698–6704. doi: 10.1021/bi00418a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang L, Ahmed SA, Miles EW. PCR mutagenesis and overexpression of tryptophan synthase from Salmonella typhimurium: on the roles of β2 subunit Lys-382. Protein Expr Purif. 1996;8:126–136. doi: 10.1006/prep.1996.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JA, JR, Montgomery J, Vreven T, Kudin KN, Burant JC, Millam JM, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Barone V, Mennucci B, Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Klene M, Li X, Knox JE, Hratchian HP, Cross JB, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Ayala PY, Morokuma K, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Zakrzewski VG, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Strain MC, Farkas O, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cui Q, Baboul AG, Clifford S, Cioslowski J, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al-Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Challacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Gonzalez C, Pople JA. B.05 ed. Gaussian, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vreven T, Morokuma K. On the application of the IMOMO (integrated molecular orbital + molecular orbital) method. J Comp Chem. 2000;21:1419–1432. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oldfield E. Chemical shifts in amino acids, peptides, and proteins. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2002;53:349–378. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.53.082201.124235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Houben KF, Kadima W, Roy M, Dunn MF. L-serine analogues form Schiff base and quinonoidal intermediates with Escherichia coli tryptophan synthase. Biochemistry. 1989;28:4140–4147. doi: 10.1021/bi00436a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Houben KF, Dunn MF. Allosteric effects acting over a distance of 20-25 Å in the Escherichia coli tryptophan synthase bienzyme complex increase ligand affinity and cause redistribution of covalent intermediates. Biochemistry. 1990;29:2421–2429. doi: 10.1021/bi00461a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pauling L. Chemical achievement and hope for the future. American Scientist. 1948;36:51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weyand M, Schlichting I. Crystal structure of wild-type tryptophan synthase complexed with the natural substrate indole-3-glycerol phosphate. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16469–16480. doi: 10.1021/bi9920533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Weyand M, Schlichting I, Marabotti A, Mozzarelli A. Crystal structures of a new class of allosteric effectors complexed to tryptophan synthase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10647–10652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111285200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.