Abstract

Ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) is a common clinical consequence of hepatic surgery, cardiogenic shock, and liver transplantation. A steatotic liver is particularly vulnerable to IRI, responding with extensive hepatocellular injury. Autophagy, a lysosomal pathway balancing cell survival and cell death, is engaged in IRI, although its role in IRI of a steatotic liver is unclear. The role of autophagy was investigated in high-fat diet (HFD)-fed mice exposed to IRI in vivo and in steatotic hepatocytes exposed to hypoxic IRI (HIRI) in vitro. Two inhibitors of autophagy, 3-methyladenine and bafilomycin A1, protected the steatotic hepatocytes from HIRI. Exendin 4 (Ex4), a glucagon-like peptide 1 analog, also led to suppression of autophagy, as evidenced by decreased autophagy-associated proteins [microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3) II, p62, high-mobility group protein B1, beclin-1, and autophagy-related protein 7], reduced hepatocellular damage, and improved mitochondrial structure and function in HFD-fed mice exposed to IRI. Decreased autophagy was further demonstrated by reversal of a punctate pattern of LC3 and decreased autophagic flux after IRI in HFD-fed mice. Under the same conditions, the effects of Ex4 were reversed by the competitive antagonist exendin 9-39. The present study suggests that, in IRI of hepatic steatosis, treatment of hepatocytes with Ex4 mitigates autophagy, ameliorates hepatocellular injury, and preserves mitochondrial integrity. These data suggest that therapies targeting autophagy, by Ex4 treatment in particular, may ameliorate the effects of IRI in highly prevalent steatotic liver.

Keywords: autophagy, ischemia-reperfusion injury, steatosis

ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) is a common mechanism of clinical injury that, in the presence of hepatic steatosis, results in poor outcomes in shock/heart failure and after hepatic resection, hepatobiliary surgery, hepatectomy, and liver transplantation (5, 10, 36, 51). At a mechanistic level, the complexity of IRI on the background of steatosis arises mostly as a result of ischemia-induced hypoxia, reperfusion-induced oxidative damage, and steatosis-induced damage, each of which contributes a different type of injury (24, 25). A network of interactions among altered sinusoidal spaces, reduced microcirculatory blood flow, mitochondrial damage, and recruited immune cells further exacerbate this complexity (50). Hepatic IRI has thus been an area of increasingly intense investigation over the past decade, with a growing emphasis on mechanisms of IRI-mediated cell death in the presence of hepatic steatosis.

Studies have shown that, in addition to the more commonly described mechanisms of necrosis and apoptosis, autophagy is involved in cell death pathways (49). Autophagy plays a critical role in removing protein aggregates and damaged or excess organelles to maintain intracellular homeostasis (34). The ultimate effect of the lysosomal degradation in autophagy remains a matter of controversy, with various reports alluding to it as a prosurvival pathway (54, 55), intimating its role in programmed cell death (7, 31), or suggesting a dual functionality of prosurvival and prodeath (1, 9, 39). Hence, the effect of autophagy is likely contextual, with environmental factors and cellular stressors contributing to autophagy's influence on cell survival (12, 35). However, the relative significance of autophagy and its related lysosomal pathways in cell death is incompletely defined, particularly in the settings of IRI and steatosis (8, 14, 53).

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1) hormone is released from the L cells of the small intestine and has been shown to have a multitude of effects on different organs. We have shown that exendin 4 (Ex4), a GLP1 analog, has a role in modulating hepatic steatosis (21) and plays a protective role in hepatic IRI by alleviating apoptosis and necrosis (20). In this study we sought to investigate two critical missing links. 1) Does autophagy play a role in the IRI of a steatotic liver? 2) Does Ex4 modulate autophagy, thereby decreasing the hepatocellular dysfunction in a fatty liver ischemia-reperfusion insult? We demonstrate that 3-methyladenine (MA) and bafilomycin A1 (BafA1), known inhibitors of autophagy, and Ex4 protect steatotic hepatocytes from ischemia-reperfusion-induced cell death. In addition, we show that Ex4 decreases the levels of several proteins associated with autophagy. Given the substantial increase in the incidence of hepatic steatosis in the general population and the frequency of varying degrees of hepatic IRI (e.g., systemic hypotension, liver surgery, and transplantation), these observations are of utmost clinical significance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals.

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Emory University approved all procedures, which were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, published by the US Public Health Service. Four-week-old male C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson Research Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Over a period of 12 wk, half the mice were fed regular chow and the other half received a high (60%)-fat diet (HFD; Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ). Mice were maintained on a 12:12-h dark-light cycle and allowed free access to food and water. Body weights were measured at regular intervals.

Hepatic IRI.

After 12 wk of feeding, mice were subjected to hepatic IRI, as described in our previous publication (20). The abdomen was exposed, and a clamp was applied across the hepatic artery, portal vein, and bile duct; partial ischemia was induced for 20 min followed by 24 h of reperfusion (selected after 6 h to 3 days of reperfusion). Ex4 (20 μg/kg iv; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was administered 2 h prior to and immediately after surgery. Sham surgeries, in which the abdomen was opened and closed without clamping, were performed in anesthetized animals.

Hepatocyte culture and in vitro hypoxic IRI.

Earlier studies employed human hepatoma (HuH7) cells as a substitute for primary hepatocytes to study in vitro hypoxic IRI (HIRI) (17). Accordingly, in the present study we also used HuH7 cells. Cells were cultured using DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT). Steatosis was induced by addition of free fatty acids (FFA): palmitic and oleic acids (400 nM each) with 10% fatty acid-free albumin (Sigma Aldrich). Steatotic and control HuH7 cells were placed in a hypoxia chamber for 30 min in serum-free medium with or without Ex4 (20 nM) and then reperfused (medium with 10% serum) with or without Ex4 for 2 h, as described elsewhere (20). A competitive antagonist of GLP1 receptor (GLP-1R), exendin 9-39 (Ex9-39, 1 μM), was added 30 min before Ex4 treatment.

Hepatocellular damage.

Hepatocellular damage was assessed in vivo by measurement of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels using Infinity ALT/GTP reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and in vitro by the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) cytotoxicity assay (Clontech, Mountain View, CA), which determines LDH release into the culture medium from dead or membrane-damaged cells. Cell culture media from steatotic HuH7 cells exposed to HIRI and treated with Ex4 were used, along with appropriate controls. Percent cytotoxicity was measured according to the manufacturer's protocol using a Synergy 2 plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT) at 490 nm and expressed as international units per liter. Percent cytotoxicity was calculated using the following formula: cytotoxicity (%) = {[sample absorbance − low control (untreated) absorbance]/(high control absorbance − low control absorbance)} × 100, where low control represents the level of spontaneous LDH release from untreated cells and high control represents the maximum LDH activity that can be released from the 100% dead cells in response to Triton X-100.

Autophagy inhibitors.

To determine whether autophagy indeed had a role in HIRI, we pretreated steatotic HuH7 and control cells for 30 min with 2.5 mM MA or 50 nM BafA1 (Sigma Aldrich), two known inhibitors of autophagy, and exposed the cells to HIRI, as described above. Percent cytotoxicity was measured using the LDH assay, as described above.

Electron microscopy.

After IRI, liver tissues were fixed in glutaraldehyde. Electron microscopy was performed by the Emory Electron Microscopy Core facility to assess the damage to liver mitochondria. Sections were viewed on a transmission electron microscope (model H-7500, Hitachi High Technologies America, Pleasanton, CA). Mitochondrial damage score was based on membrane and cristae morphology and integrity, as described previously (11) and shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Criteria used to calculate mitochondrial damage score

| Damage Score | Morphological Appearance |

|---|---|

| 0 | Well-defined and organized membranes and cristae |

| 1 | Minor distortions and/or swellings, but general organization retained |

| 2 | Major distortions and/or swellings and discontinuous membranes and cristae |

| 3 | Membranes and cristae dissociated into particulates to produce diffuse mitochondrial ghosts |

| 4 | Only a few mitochondrial remnants in cells |

Mitochondrial enzyme activity analysis.

Mitochondrial enzyme activity was evaluated using the 2,3-bis-(2-methyl-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide (XTT) Cell Viability Kit (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The XTT assay is based on cleavage of the tetrazolium salt XTT, which occurs in the presence of viable mitochondrial enzymes. Cultured cells were rinsed and treated with XTT for 12 h, and the formazan dye that formed was quantified using a Synergy 2 plate reader at 450 nm. Percent enzyme activity was calculated according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blotting.

Liver tissues and HuH7 cells were processed and subjected to Western blotting. Equal amounts of protein were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and probed with specific antibodies against high-mobility group protein 1 (HMGB1), microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3) II, p62, beclin-1, and autophagy-related protein 7 (ATG7) (Cell Signaling Technology). Relative band densities were analyzed using Image Lab software (version 3.0, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

In vitro hepatocyte transfection with pSELECT green fluorescent protein-LC3 vector and confocal microscopy.

Steatotic HuH7 cells were transfected with the pSELECT green fluorescent protein (GFP)-LC3 vector (a gift from Dr. Arianne Thiess, Department of Internal Medicine, Baylor Research Institute, Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, TX) or the empty vector (27). After 48 h of transfection, cells were exposed to HIRI and treated with Ex4. Cells were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, counterstained with the nuclear stain 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, and analyzed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (model FV1000, Olympus America, Center Valley, PA). Six random fields (per slide) were captured using ×60 and ×100 objectives, and the number of cells showing punctate GFP-LC3 staining was determined.

Measurement of autophagy flux.

Autophagy flux was assessed in HIRI-exposed and non-HIRI-exposed steatotic HuH7 cells. A difference in LC3 II levels in the presence and absence of lysosomal degradation (BafA1, 10 nM) represents autophagic flux (30); BafA1 prevents maturation of autophagic vacuoles by inhibiting fusion of autophagosomes to lysosomes. To assess the autophagic flux, lean and steatotic cells were pretreated with or without BafA1 for 2 h and then exposed to HIRI and treated with Ex4 and Ex9-39. Western blots were performed as described above. LC3 II band intensities were analyzed using Image Lab software (version 3.0). LC3 II intensities were normalized to band intensities of β-actin, as in previous studies (40, 57). Autophagy flux (AF) was evaluated by the following equations according to the instructions of the VIVA Detect Autophlux Kit instruction manual (VIVA Bioscience, UK): UT AF = (UT + BafA1) − (UT − BafA1), MT AF = (MT + BafA1) − (MT − BafA1), and ΔAF = (MT AF) − (UT AF), where UT is untreated and MT is modulator (Ex4/Ex9-39)-treated.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using Student's t-test (Prism 5.0, Graphpad, San Diego, CA). P < 0.05 was regarded as significant.

RESULTS

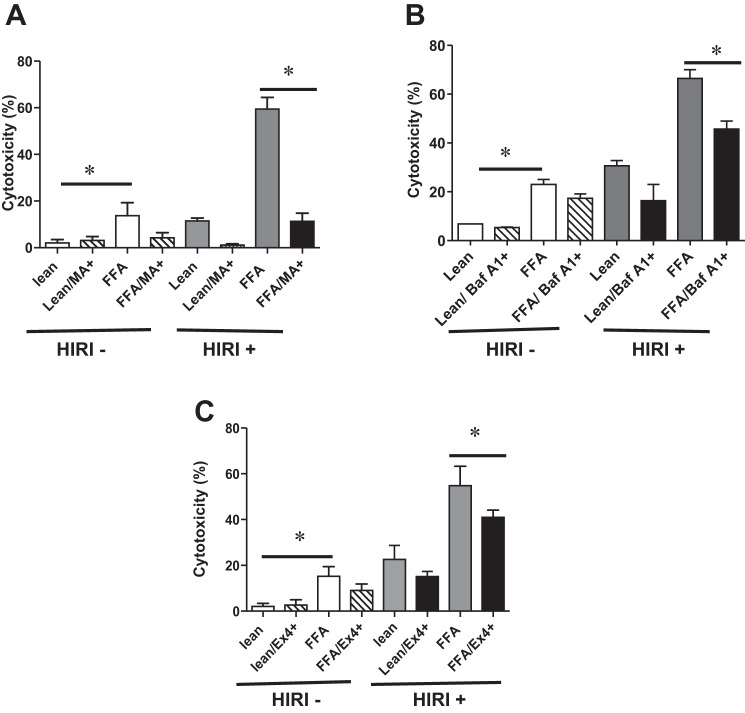

Autophagy inhibitors MA, BafA1, and Ex4 decrease IRI-induced hepatocellular cytotoxicity.

To determine if autophagy plays a role in IRI of a steatotic liver, we utilized steatotic HuH7 cells exposed to HIRI, as described in materials and methods. The autophagy pathway was blocked by pretreatment of cells with MA or BafA1, known inhibitors of autophagy. As expected, LDH levels at baseline were significantly higher in steatotic than lean cells [13.6 ± 2.0 vs. 2.0 ± 0.8 (P < 0.008); Fig. 1A]. Pretreatment with MA mitigated cytotoxicity induced by HIRI [lean/HIRI+/MA−: 11.4 ± 0.9 vs. lean/HIRI+/MA+: 1.0 ± 0.3 (P < 0.001) and FFA/HIRI+/MA−: 59.4 ± 2.8 vs. FFA/HIRI+/MA+: 11.32 ± 1.3 (P < 0.0001); Fig. 1A]. Similarly, treatment with BafA1 (50 nM) also mitigated cytotoxicity induced by HIRI [lean/HIRI+/BafA1−: 30.6 ± 2.1 vs. lean/HIRI+/BafA1+: 16.4 ± 6.6 (P < 0.08) and FFA/HIRI+/BafA1−: 66.5 ± 3.5 vs. FFA/HIRI+/BafA1+: 45.6 ± 3.3 (P < 0.02); Fig. 1B]. These results imply that autophagy is a critical pathway in cellular toxicity of HIRI and warrant further investigation. Treatment with Ex4 had a similar effect, with decreases in cellular cytotoxicity in the steatotic HuH7 cells [lean/HIRI+/Ex4−: 22.5 ± 2.3 vs. lean/HIRI+/Ex4+: 15.1 ± 0.8 (P < 0.01) and FFA/HIRI+/Ex4−: 54.8 ± 3.1 vs. FFA/HIRI+/Ex4+: 40.9 ± 1.3 (P < 0.006); Fig. 1C], confirming the protective effect of Ex4 in our in vitro system (20). The concentrations of Ex4, BafA1, and MA were not normalized for comparison but were selected arbitrarily on the basis of findings in the literature. BafA1 and MA were used to determine whether autophagy is involved in the IRI-exposed steatotic hepatocytes, making it an important area for further study. MA inhibits autophagy by targeting phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling, whereas BafA1 inhibits autophagy by inhibiting the fusion of autophagosomes to lysosomes. Even though MA and BafA1 act at different sites in the autophagic process, the observation that both inhibitors protected steatotic hepatocytes subjected to hypoxic reperfusion injury is significant.

Fig. 1.

A–C: 3-methyladenine (MA) and bafilomycin A1 (BafA1), inhibitors of autophagy, and exendin 4 (Ex4) decrease hepatocellular cytotoxicity induced by hypoxic ischemia-reperfusion injury (HIRI). A: lean and steatotic human hepatoma (HuH7) cells were exposed to HIRI and treated with MA, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity was measured to calculate percent cytotoxicity during normoxia (HIRI−) and hypoxia (HIRI+). For open and gray bars: HIRI−/FFA+/MA− vs. HIRI+/FFA+/MA− (P < 0.0001). For black bar: lean+/MA+ vs. lean+/MA− (P < 0.001) and FFA+/MA+ vs. FFA+/MA− (P < 0.0001). B: lean and steatotic HuH7 cells were treated with BafA1 (50 nM) during normoxia and HIRI, and LDH activity was measured to calculate percent cytotoxicity. Lean+/BafA1+ vs. lean+/BafA1− (not significant) and FFA+/BafA1+ vs. FFA+/BafA1− (P < 0.02). Values are means ± SD of triplicate plates. C: lean and steatotic HuH7 cells were exposed to HIRI and treated with or without Ex4, and LDH activity was measured to calculate percent cytotoxicity. Percent cytotoxicity was calculated by measuring LDH. For open and gray bars: HIRI−/FFA+/Ex4− vs. HIRI+/FFA+/Ex4− (P < 0.0001); for black bars: lean+/Ex4+ vs. lean+/Ex4− (P < 0.01) and FFA+/Ex4+ vs. FFA+/Ex4− (P < 0.006). Experiments were repeated 3 times in triplicate. Values are means ± SD. *P < 0.05.

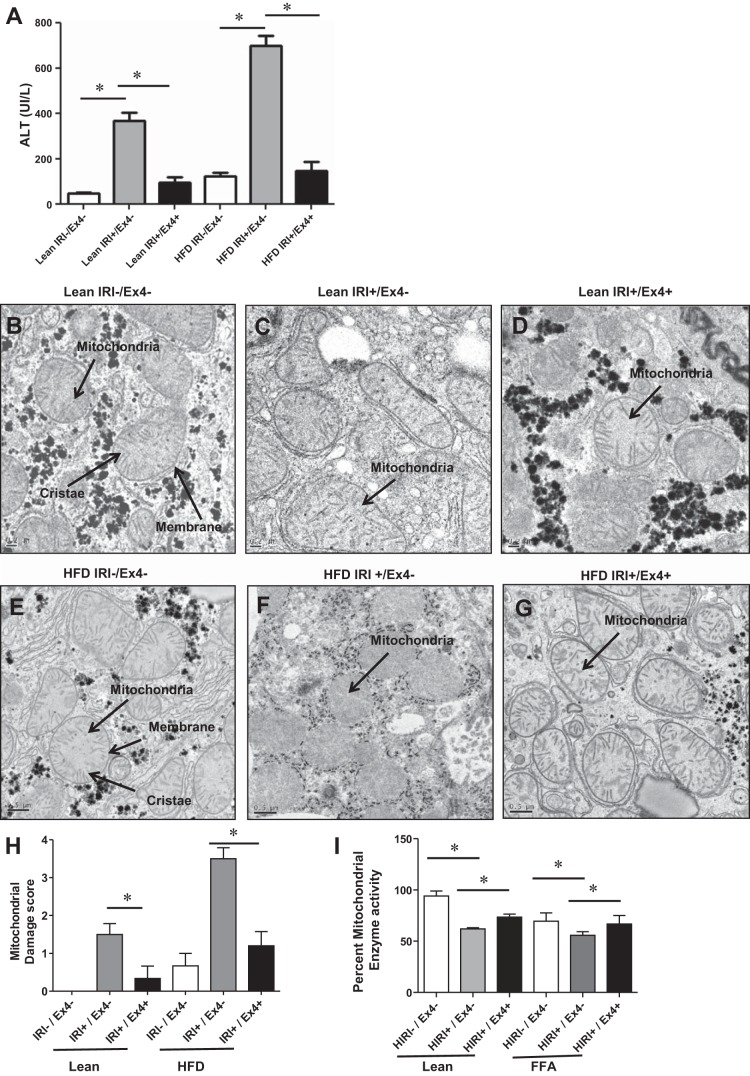

Ex4 treatment improved IRI/HIRI-induced hepatocellular injury and mitochondrial damage.

Having determined the protective effect of Ex4 in cell death and the importance of autophagy in the cytotoxicity after IRI, we investigated the mitochondrial integrity and mitochondrial enzyme activity that are known to be altered in autophagy. Results presented in Fig. 2A clearly indicate that hepatocellular injury, monitored as serum ALT levels, was increased in steatotic livers compared with the corresponding lean mice and that exposure to IRI further exacerbated the injury in steatotic livers compared with livers from lean mice. Ex4 conferred almost complete protection against IRI in lean, as well as HFD-fed, mice [lean/IRI−/Ex4−: 46.8 ± 7.5 vs. lean/IRI+/Ex4−: 370 ± 33.7 (P < 0.0001); lean/IRI+/Ex4−: 370.0 ± 33.7 vs. lean/IRI+/Ex4+: 95.5 ± 23.8 (P < 0.001); HFD/IRI−/Ex4−: 124.7 ± 16.9 vs. HFD/IRI+/Ex4−: 700.7 ± 43.5 (P < 0.0002); HFD/IRI+/Ex4−: 700.7 ± 43.5 vs. HFD/IRI+/Ex4+: 148.5 ± 39.1 (P < 0.0002), where all values are expressed as IU/l]. Mitochondrial damage, as shown by electron microscopic images of liver tissues, mirrored serum ALT levels. Lean control mice, with intact liver mitochondrial architecture with well-defined membranes and normal cristae, were given baseline scores of 0 (Fig. 2, B and H). In contrast, after exposure to IRI, the HFD-fed mice showed pronounced mitochondrial damage, as evidenced by a discontinuous membrane, particulate cristae, and mitochondrial ghosts; mitochondrial damage scores of these HFD-fed mice were significantly higher than those of the lean mice: 3.5 ± 0.28 vs. 1.5 ± 0.2 (P < 0.001; Fig. 2, C, F, and H). Treatment with Ex4 offered significant mitochondrial protection, with the mitochondrial score improving to 1.2 ± 0.37 (P < 0.002) in HFD-fed mice and 0.33 ± 0.3 (P < 0.04) in lean mice (Fig. 2, D, G, and H).

Fig. 2.

Ex4 treatment improved IRI/HIRI-induced mitochondrial damage. A–G: mice were fed regular chow or a high-fat diet (HFD) for 12 wk and then exposed to IRI with or without Ex4. Serum was analyzed for alanine aminotransferase (ALT; A), and liver tissues were processed for electron microscopic analysis of mitochondrial integrity (B–G). A: open bars, lean and HFD controls [not subjected to IRI (IRI−)]; gray bars, lean and HFD-fed mice subjected to IRI (IRI+/Ex4−); black bars, lean and HFD-fed mice subjected to IRI and treated with Ex4 (IRI+/Ex4+). Values are means ± SD; n = 6 per group. Lean/IRI−/Ex4− vs. lean/IRI+/Ex4− (P < 0.0001); lean/IRI+/Ex4− vs. lean/IRI+/Ex4+ (P < 0.001); HFD/IRI−/Ex4− vs. HFD/IRI+/Ex4− (P < 0.0002); HFD/IRI+/Ex4− vs. HFD/IRI+/Ex4+ (P < 0.0002). B–G: electron micrographs showing representative images of mitochondria from livers of mice described in A. Fifteen images were obtained from each slide, mitochondrial morphology was assessed in 10 fields per image, and damage scores were calculated as shown in Table 1. Arrows indicate mitochondria, mitochondrial membranes, and cristae. H: mitochondrial damage score calculated on the basis of electron micrographs (B–G). Values are means ± SD; n = 8 per group. Lean/IRI+/Ex4− vs. lean IRI+/Ex4+ (P < 0.04); HFD/IRI+/Ex4− vs. HFD/IRI+/Ex4+ (P < 0.02). I: mitochondrial enzyme activity in HuH7 cells assessed using XTT assay. FFA, free fatty acid-induced steatosis. Values are means ± SD; n = 9. Lean/HIRI−/Ex4− vs. lean/HIRI+/Ex4− (P < 0.0001); lean/HIRI+/Ex4− vs. lean/HIRI+/Ex4+ (P < 0.02); FFA/HIRI−/Ex4− vs. FFA/HIRI+/Ex4− (P < 0.001); FFA/HIRI+/Ex4− vs. FFA/HIRI+/Ex4+ (P < 0.008). Each assay was performed in triplicate, and the experiment was repeated 3 times. *P < 0.05.

We also assessed mitochondrial enzyme activity using the XTT assay. Lean and steatotic HuH7 cells exposed to HIRI demonstrated decreased activity (Fig. 2I). Ex4 improved the mitochondrial enzyme activity [FFA/HIRI+/Ex4+: 66.8 ± 3.6 vs. FFA/HIRI+/Ex4−: 55.7 ± 1.2 (P < 0.008) and lean/HIRI+/Ex4+: 73.5 ± 1.6 vs. lean/HIRI+/Ex4−: 62.0 ± 0.6 (P < 0.0007)]. Thus, in the setting of IRI, Ex4 appeared to confer substantial mitochondrial protection (structural and functional) in lean and HFD-fed mice.

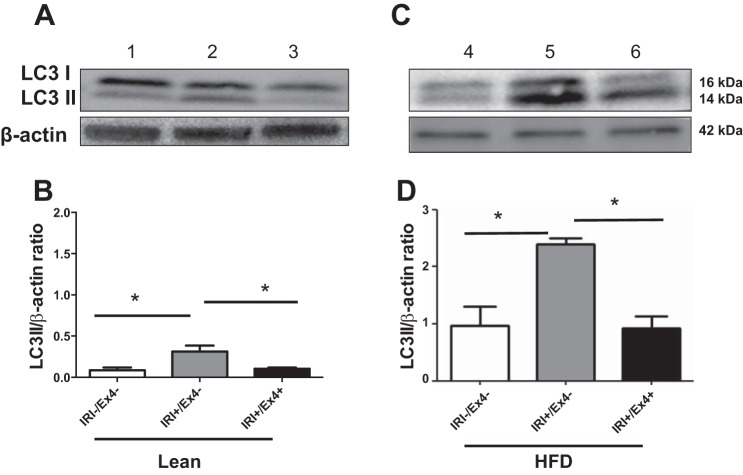

Ex4 mitigates the autophagy marker LC3 II in livers of IRI-exposed lean and HFD-fed mice.

After establishing the protective effect of Ex4 after IRI in vivo and in vitro, we assessed biochemical markers for autophagy. For in vivo studies we assessed the autophagy marker LC3 II (48). IRI-exposed lean and HFD-fed mice demonstrated significantly higher levels of LC3 II than controls [lean/IRI+: 0.31 ± 0.07 vs. lean/IRI−: 0.086 ± 0.03 (P < 0.04) and HFD/IRI+: 2.4 ± 0.1 vs. HFD/IRI−: 0.97 ± 0.3 (P < 0.01); Fig. 3]. Ex4 treatment leads to a decrease in levels of LC3 II, indicative of mitigating autophagy [HFD/IRI+/Ex4+: 0.92 ± 0.21 vs. HFD/IRI+/Ex4−: 2.4 ± 0.1 (P < 0.002); Fig. 3D]. Lean mice demonstrated a similar trend but to a lesser extent. These results demonstrate that Ex4 can mitigate IRI-induced autophagy as monitored by the levels of LC3 II.

Fig. 3.

Ex4 mitigates the autophagy marker microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3) II in liver of lean and HFD-fed mice exposed to IRI. After IRI and with or without Ex4 treatment, livers of lean (A and B) and HFD-fed (C and D) mice were homogenized, and equal amounts of protein were subjected to electrophoresis and probed with LC3 I/II antibody. A: Western blot for LC3 I/II and β-actin (loading control). Lane 1, control (IRI−); lane 2, IRI+/Ex4−; lane 3, IRI+/Ex4+. B: relative band density of LC3 II-to-β-actin ratio. Lean/IRI−/Ex4− vs. lean/IRI+/Ex4− (P < 0.04); lean/IRI+/Ex4− vs. lean/IRI+/Ex4+ (P < 0.04). C: Western blot for LC3 I/II and β-actin. Lane 4, HFD/IRI−/Ex4−; lane 5, HFD/IRI+/Ex4−; lane 6, HFD/IRI+/Ex4+. D: relative band density of LC3 II-to-β-actin ratio in HFD-fed mice. HFD/IRI−/Ex4− vs. HFD/IRI+/Ex4− (P < 0.01); HFD/IRI+/Ex4− vs. HFD/IRI+/Ex4+ (P < 0.002). Values are means ± SD; n = 9. *P < 0.05.

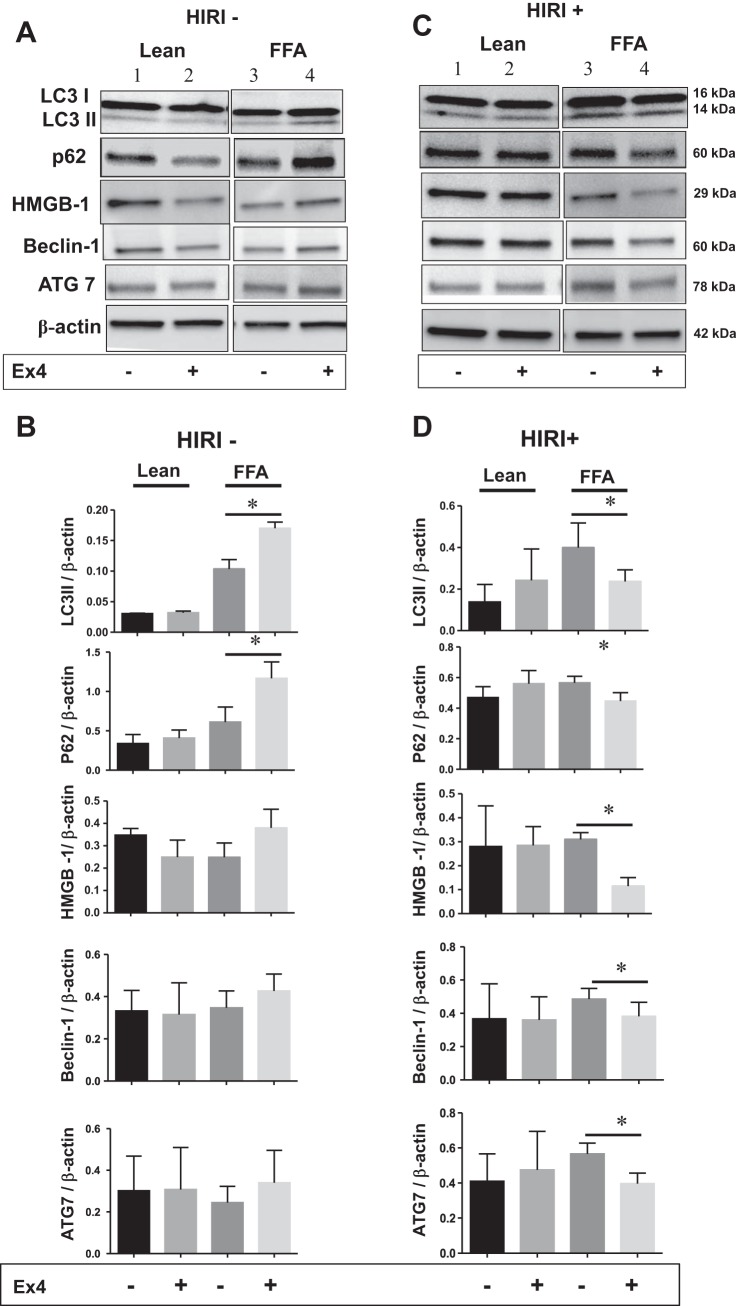

Ex4 mitigates autophagy in steatotic HuH7 cells exposed to HIRI.

In the next series of experiments, a detailed study was undertaken to determine the effect of Ex4 on autophagy in lean and steatotic HuH7 cells exposed to normoxia (HIRI−) as well as hypoxia (HIRI+). Autophagy was assessed by evaluating the autophagy markers LC3 II, p62, HMGB1, beclin-1, and ATG7. As shown in Fig. 4, A and B, in normoxia-exposed steatotic hepatocytes, Ex4 increased the levels of autophagy markers; for example, LC3 II and p62 were statistically significantly increased. Although the increase in other markers was not statistically significant, the positive trend is clear (Fig. 4B). In contrast, in HIRI-exposed steatotic cells, Ex4 clearly and significantly decreased all the autophagy markers (Fig. 4, C and D). Lean hepatocytes failed to show statistically significant changes in the autophagy markers with exposure to normoxia or HIRI and with or without Ex4.

Fig. 4.

A–D: Ex4 mitigates autophagy in steatotic HuH7 cells during HIRI. Lean and steatotic hepatocytes were treated with and without Ex4 during normoxia (HIRI−) and hypoxia (HIRI+). Total cell lysates were subjected to electrophoresis followed by Western blotting with anti-LC3 I/II, p62, high-mobility group protein 1 (HMGB1), beclin-1, autophagy-related protein 7 (ATG7), and β-actin antibodies. A and C: HIRI− and HIRI+. Lanes 1 and 3, lean and FFA with no treatment; lanes 2 and 4, lean and FFA with Ex4 treatment. B and D: relative band density. Experiments were repeated 3 times in triplicate. Values are means ± SD. Ex4 treatment resulted in a statistically significant reduction of autophagy markers in steatotic cells exposed to HIRI. In steatotic cells that were not exposed to HIRI, Ex4 treatment resulted in an increase, rather than a decrease, in autophagy markers. Increase in LC3 II and p62 proteins was statistically significant. While the other proteins did not reach statistical significance, the increasing trend appears clear. *P < 0.05.

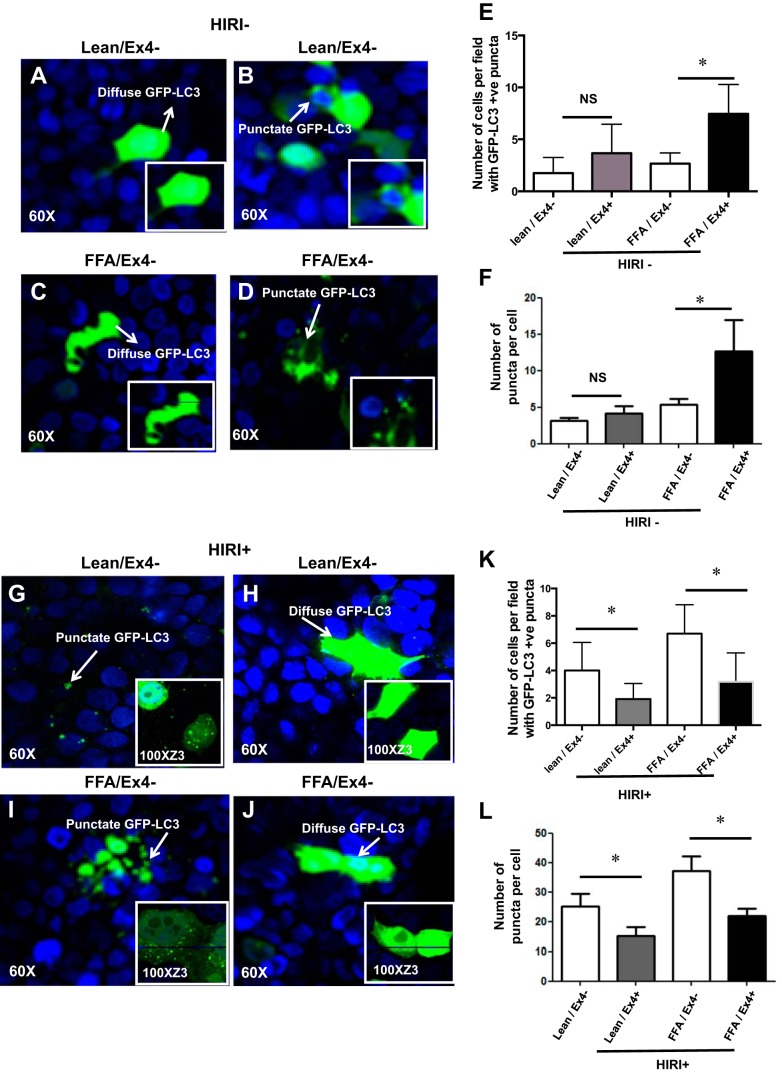

Ex4 treatment increases autophagy as evidenced by an enhanced punctate staining of GFP-LC3 in steatotic cells exposed to normoxia.

To verify our observation that Ex4 exhibits dual mechanisms of accentuating and attenuating autophagy with exposure to normoxia or HIRI, respectively, we performed additional studies. Lean and steatotic HuH7 cells were transfected with pSELECT GFP-LC3 vector. In steatotic cells exposed to normoxia, GFP-LC3 showed a diffuse pattern (Fig. 5C). Upon treatment with Ex4 the diffuse pattern was transformed into a distinct punctate pattern, indicating increased autophagosome formation (Fig. 5D). The number of cells with puncta was quantified [FFA/Ex4−: 2.6 ± 0.42 vs. FFA/Ex4+: 7.46 ± 0.78 (P < 0.0009); Fig. 5E], and the number of puncta per cell was also quantified [FFA/Ex4−: 5.33 ± 0.8 vs. FFA/Ex4+: 12.67 ± 4.2 (P < 0.04); Fig. 5F]. Ex4 also led to a mild increase in autophagy in lean cells, but the effect was less robust than the increase in the steatotic cells and was not statistically significant (Fig. 5, A, B, E, and F). These data confirm that Ex4 increases autophagy during normoxia.

Fig. 5.

Ex4 treatment increases autophagy, as evidenced by an enhanced punctate staining of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-LC3 in steatotic cells exposed to normoxia. Lean and steatotic hepatocytes were cultured on chamber slides and transfected with pSELECT GFP-LC3 vector and then treated with Ex4 or vehicle. Cells were mounted, and images were obtained using confocal microscopy at ×60 magnification. A–D: HIRI−. E and F: graphic representation of puncta with or without Ex4 in lean and steatotic HuH7 cells from 3 independent experiments. These punctate patterns were quantified in 6 fields per section, with ∼50 cells per field. Insets: representative enlarged images. E: number of cells with puncta. Lean/Ex4− vs. lean/Ex4+ (P < 0.008); FFA/Ex4− vs. FFA/Ex4+ (P < 0.0009). Values are means ± SD. *P < 0.05. F: number of puncta in GFP-LC3-positive cells were counted and are shown as number of puncta per cell. Values are means ± SD. Lean/Ex4− vs. lean/Ex4+ [P < 0.35 (not significant, NS)]; FFA/Ex4− vs. FFA/Ex4+ (P < 0.04). G–J: Ex4 pretreatment mitigates punctate staining of GFP-LC3 in lean and steatotic hepatocytes exposed to HIRI, indicating attenuation of autophagy. Lean and steatotic hepatocytes were cultured on chamber slides and transfected with pSELECT GFP-LC3 vector and then exposed to HIRI, with or without Ex4 treatment. Cells were mounted, and images were obtained using confocal microscopy at ×60 magnification. Insets: images of staining pattern at ×100 magnification zoomed 3 times. K and L: graphical representation of puncta, with or without Ex4, in lean and steatotic HuH7 cells from 3 independent experiments. Punctate patterns were quantified in 6 areas in each section with ∼50 cells per field. K: number of cells with puncta. Values are means ± SD. Lean/Ex4− vs. lean/Ex4+ (P < 0.008); FFA/Ex4− vs. FFA/Ex4+ (P < 0.0009). L: number of puncta in GFP-LC3-positive cells were counted and are shown as number of puncta per cell. Values are means ± SD. Lean/Ex4− vs. lean/Ex4+ (P < 0.03); FFA/Ex4− vs. FFA/Ex4+ (P < 0.004). *P < 0.05.

Ex4 treatment mitigates punctate staining of GFP-LC3 in lean and steatotic hepatocytes exposed to HIRI, indicating attenuation of autophagy.

After verifying that Ex4 increases autophagosome formation in normoxia-exposed steatotic cells, we exposed GFP-LC3-transfected cells to HIRI. The steatotic HuH7 cells demonstrated an increase in punctate GFP-LC3 staining (Fig. 5I) compared with non-HIRI-exposed cells (Fig. 5C), indicating increased autophagosome formation. Quantitative data presented in Fig. 5, E and F (non-HIRI-exposed steatotic hepatocytes) and in Fig. 5, K and L (HIRI-exposed steatotic hepatocytes) indicate increased autophagosome formation in steatotic hepatocytes exposed to HIRI. Treatment with Ex4 led to a remarkable change, i.e., replacement of the punctate pattern with a prominent diffuse pattern of GFP-LC3 (Fig. 5J), implying attenuation of autophagy. The number of cells with puncta was quantified [FFA/Ex4+: 6.7 ± 0.6 vs. FFA/Ex4−: 3.1 ± 0.6 (P < 0.0009); Fig. 5K]. Lean HuH7 cells demonstrated a similar trend (Fig. 5, G and H). The number of cells with puncta was quantified [lean/Ex4−: 4.0 ± 0.6 vs. lean/Ex4+: 1.9 ± 0.3 (P < 0.008); Fig. 5K]. The number of puncta per cell was also quantified [FFA/Ex4−: 37.07 ± 5.0 vs. FFA/Ex4+: 21.85 ± 2.4 (P < 0.004); Fig. 5L]. Lean HuH7 cells demonstrated a similar trend [lean/Ex4−: 25.09 ± 4.4 vs. lean/Ex4+: 13.40 ± 2.6 (P < 0.03)]. These results corroborate our earlier data on the effect of Ex4 in reducing autophagy under HIRI conditions.

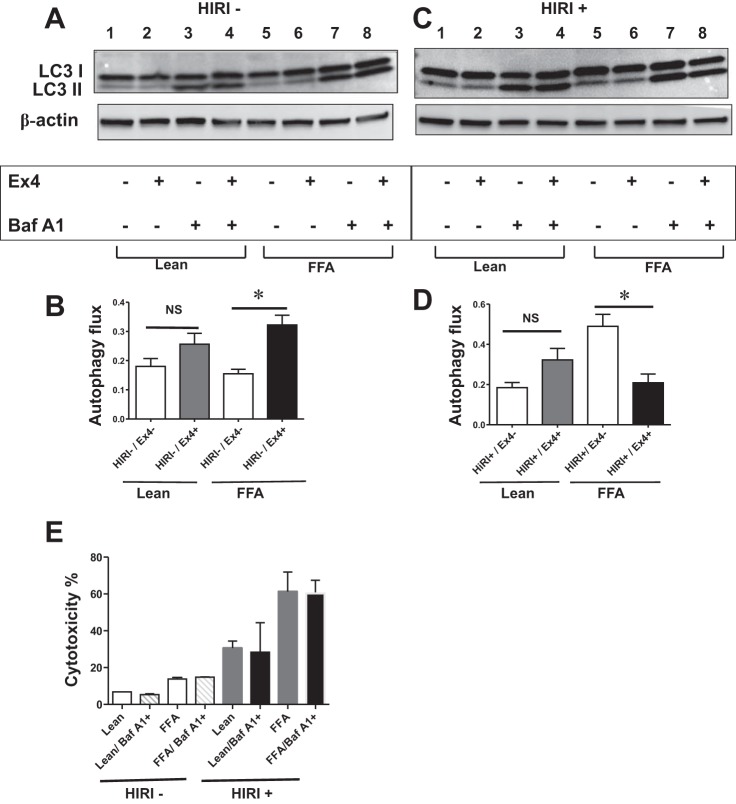

Ex4 increases autophagic flux in steatotic hepatocytes exposed to normoxia.

Thus far, the results from monitoring autophagy biomarkers and from the GFP-LC3 transfection studies are consistent with the dual action of Ex4 in increasing or decreasing autophagy, depending on the presence or absence of HIRI. Next, we evaluated autophagic flux, which has been deemed the gold standard for precise and consistent evaluation of autophagosome formation. We used BafA1, an autophagy inhibitor, which inhibits fusion of autophagosomes to lysosomes and, thus, can detect the levels of LC3 II before degradation. After BafA1 (10 nM) treatment, autophagosome flux (monitored as changes in LC3 II levels) increased considerably in normoxia-exposed steatotic cells after treatment with Ex4, indicating accentuation of autophagy and confirming our above-mentioned findings [FFA/Ex4−: 0.15 ± 0.1 vs. FFA/Ex4+: 0.32 ± 0.03 (P < 0.03); Fig. 6, A and B]. Although the increase in lean cells did not reach statistical significance, the increasing trend is clear (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

A and B: Ex4 increases autophagic flux in steatotic hepatocytes exposed to normoxia (HIRI−). Autophagic flux was assessed using BafA1 (10 nM). A: Western blot for LC3 I/II and β-actin (loading control). Lanes 1 and 5, Ex4−/BafA1−; lanes 2 and 6, Ex4+/BafA1−; lanes 3 and 7, Ex4−/BafA1+; lanes 4 and 8, Ex4+/BafA1+. Lanes 1–4 are from lean cells, and lanes 5–8 are from steatotic (FFA) cells. B: graphical representation of autophagic flux, which was calculated using equation in materials and methods. Values are means ± SD. FFA/Ex4− vs. FFA/Ex4+ (P < 0.03). C and D: Ex4 decreases autophagic flux in steatotic hepatocytes exposed to HIRI. C: Western blot for LC3 I/II and β-actin. Lanes 1 and 5, Ex4−/BafA1−; lanes 2 and 6, Ex4+/BafA1−; lanes 3 and 7, Ex4−/BafA1+; lanes 4 and 8: Ex4+/BafA1+. Lanes 1–4 are from lean cells, and lanes 5–8 are from steatotic (FFA) cells. Autophagic flux was assessed as described in materials and methods. D: graphical representation of autophagic flux. There was a significant decrease in autophagic flux in the Ex4-treated FFA cells: FFA/Ex4− vs. FFA/Ex4+ (P < 0.01). E: BafA1 at 10 nM, the concentration at which BafA1 inhibits autophagy flux, is not cytotoxic, nor does it confer survival advantage to lean and steatotic hepatocytes exposed to normoxia, as well as HIRI. Lean and steatotic HuH7 cells were treated with BafA1 (10 nM) during normoxia and HIRI, and LDH activity was measured to calculate percent cytotoxicity. Values are means ± SD of triplicate plates. *P < 0.05.

Ex4 decreases autophagic flux in steatotic hepatocytes exposed to HIRI.

Next, we evaluated autophagic flux in steatotic HuH7 cells exposed to HIRI. After treatment with Ex4, a significant attenuation was observed in autophagic flux in the steatotic cells [FFA/Ex4−: 0.49 ± 0.05 vs. FFA/Ex4+: 0.2 ± 0.4 (P < 0.01); Fig. 6, C and D], in contrast to the increase observed in normoxia-exposed cells, thus confirming the dual effect of Ex4 on autophagy. The lean cells showed a mild increase in flux; however, the increase was not statistically significant.

To rule out the possible influence of cytotoxicity or viability induced by BafA1 on the flux data, we studied the effect of BafA1 on steatotic, as well as lean, hepatocytes exposed to normoxia and HIRI. BafA1 at 10 nM, a concentration at which BafA1 inhibited autophagy flux, is not cytotoxic, nor did it confer cell survival advantage. These results clearly rule out any complications that might arise by cytotoxicity or survival advantage on flux data (Fig. 6E).

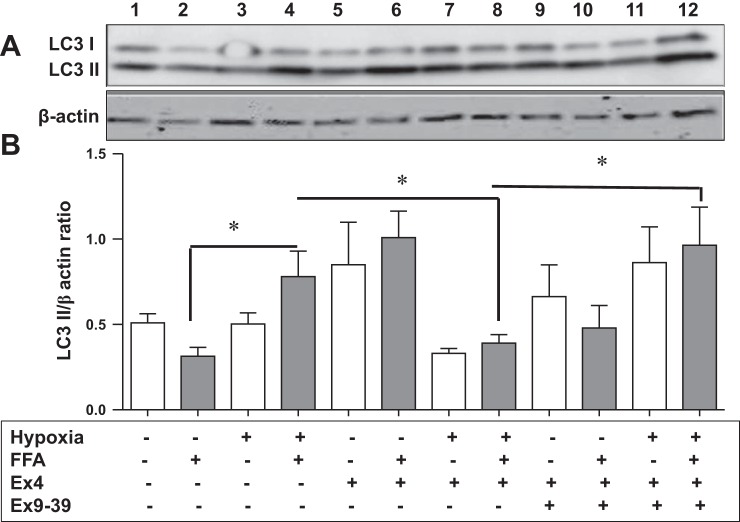

The GLP-1R antagonist Ex9-39 reverses the effects of Ex4 on autophagy.

Because Ex4 is an agonist of GLP-1R, we chose to determine whether Ex4 exerts its effects on autophagy via GLP-1R. We utilized Ex9-39, a competitive inhibitor, which competes with Ex4 for GLP-1R. The results presented in Fig. 7 indicate a significant increase in LC3 II levels in steatotic hepatocytes exposed to HIRI (lane 4) compared with non-HIRI-exposed cells (lane 2): 0.78 ± 0.14 vs. 0.31 ± 0.05 (P < 0.01). These effects were significantly attenuated on treatment with Ex4 in steatotic cells exposed to HIRI: 0.78 ± 0.14 in lane 4 vs. 0.39 ± 0.04 in lane 8 (P < 0.02). This attenuation was significantly reversed upon treatment with Ex9-39, a GLP-1R antagonist, under similar conditions: 0.39 ± 0.04 in lane 8 vs. 0.96 ± 0.2 in lane 12 (P < 0.01). In contrast, there was a significant increase in LC3 II levels upon treatment with Ex4 in non-HIRI-exposed steatotic hepatocytes: 0.31 ± 0.05 in lane 2 vs. 1.0 ± 0.15 in lane 6 (P < 0.0002). These effects were reversed upon treatment with Ex9-39 under similar conditions, although the reversal was not statistically significant: 1.0 ± 0.15 in lane 6 vs. 0.48 ± 0.13 in lane 10 (P < 0.07). These changes were not seen in normoxia- or hypoxia-exposed lean HuH7 cells: lane 5 vs. lane 9 and lane 7 vs. lane 11. These results are consistent with a possible role of GLP-1R in autophagy.

Fig. 7.

Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP-1R) antagonist, Ex9-39, reverses effects of Ex4 on levels of the autophagy marker LC3 II. Lean and steatotic HuH7 cells were pretreated with a competitive antagonist of GLP-1R, Ex9-39, before Ex4 treatment. Total cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting with LC3 I/II antibody. A: Western blot for LC3 I/II and β-actin (loading control). Lanes 1, 5, and 9, lean cells exposed to normoxia (HIRI−); lanes 2, 6, and 10, steatotic cells exposed to normoxia (HIRI−); lanes 1 and 2, controls; lanes 5 and 6, cells exposed to Ex4; lanes 9 and 10, cells pretreated with Ex9-39 and then treated with Ex4; lanes 3, 7, and 11, lean cells; lanes 4, 8, and 12, steatotic cells exposed to hypoxia (HIRI+); lanes 3 and 4, controls; lanes 7 and 8, cells treated with Ex4; lanes 11 and 12, cells pretreated with Ex9-39 and then treated with Ex4. B: graphical representation of relative band density with and without Ex4/Ex9-39. Open bars, lean cells; gray bars, steatotic cells. Ex9-39 significantly reversed Ex4-induced effects on autophagy under hypoxia: HIRI+/FFA+/Ex9-39− vs. HIRI+/FFA+/Ex9-39+ (P < 0.01). In lean cells, although a similar trend was seen, differences were not statistically significant. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Autophagy is considered a fundamental component of several liver diseases (43, 46, 58), including fatty liver disease (2, 44), with an overall protective effect on lipid metabolism (16, 45). Few reports have alluded to autophagy in IRI of the heart and liver (37, 47, 52), and our study is the first to demonstrate that autophagy can be detrimental in the presence of hypoxia and steatosis. In addition, Ex4, a GLP-1R agonist, can decrease autophagy in IRI of a steatotic liver and increase autophagy in normoxia, with both scenarios resulting in cell protection. It should be interesting to explore the dual effect of Ex4. Nevertheless, this offers an exciting therapeutic target for a clinical condition of surmounting significance. Because the ultimate effect of Ex4 is cell survival, the autophagic balance between prosurvival and prodeath in conditions of IRI is pivotal.

We clearly show that IRI (and HIRI in the in vitro model) leads to an increase in autophagy, which is associated with cell death, as evidenced by increased serum ALT and mitochondrial damage in vivo and LDH in vitro, and that MA and BafA1, inhibitors of autophagy, confer protection to steatotic hepatocytes exposed to HIRI. The upregulation of autophagy is demonstrated by autophagic flux, biomarker upregulation, and the punctate pattern of GFP-LC3 II protein, monitored as puncta per cell, as well as number of punctate-positive cells per field. Autophagic flux is considered the gold standard for evaluation of autophagy, as treatment with BafA1 prevents degradation of autophagosomes, permitting accurate quantification. In our studies, the autophagic flux was increased in steatotic cells exposed to HIRI, with a corresponding increase in cell death. Several autophagy markers such as LC3 II, ATG7, beclin-1, HMGB1, and p62, also showed increased levels. The observation that increased levels of p62 were associated with increased autophagy deserves a comment. Since p62 is degraded during autophagy, it is argued that decreased levels of p62 can be observed when autophagy is induced, and when autophagy is inhibited p62 accumulates. It is not surprising, therefore, that most of the reports, especially the nutrition/starvation-related studies, allude to an increase in p62 levels in response to a decrease in autophagy. Our model, although highly relevant clinically, is complicated at a molecular level: an environment of excess fat (steatosis) superimposed with hypoxia and nutrient deprivation (ischemia) followed by oxidative injury (reperfusion) makes comparison with autophagy in nutrition models difficult. This model is an interplay of several different signaling pathways. A probable explanation for our observation would be that Nrf2, which is expressed in response to oxidative damage, leads to induction of p62 and an increase in autophagy (26). Additionally, Ex4 has been shown to decrease oxidative stress and, thereby, can decrease p62 levels, which in turn can result in decreased autophagy (41, 42). A detailed study is needed to explore this alternate hypothesis.

Microscopically, an increase in the punctate pattern of GFP-LC3-transfected proteins signified autophagosome formation (3, 27). Increased autophagy resulting in cell death has been reported in myocardial IRI (38, 47), whereas increased autophagy after hepatic IRI alludes to a protective role (18, 52). Hence, there is evidence for a dual role of autophagy, with mitochondrial integrity being an important determinant of cell survival or death.

Mitochondria respond to the stress of hypoxia, reactive oxygen species, and loss of growth factors by regulating cell death, as demonstrated in steatotic liver IRI (19). In our study, increased autophagy was associated with disruption of mitochondrial membranes and cristae in the liver of HFD-fed mice exposed to IRI, with decreased mitochondrial function confirmed in our in vitro model. Ex4 reversed the structural and functional damage. It remains to be determined, however, whether this mitochondrial damage is due to mitophagy (33) or other mechanisms, such as signaling pathways, lipid, or receptor dynamics. Additionally, although it is our contention that increased autophagy in the steatotic liver after IRI is a cell death mechanism because of the association with concurrent increased hepatocellular injury and mitochondrial dysfunction, we acknowledge that there are other facets to autophagy (29, 35), and its exact role remains elusive.

While the role of autophagy in promoting cell survival or cell death depends greatly on the surrounding environment, we have shown that Ex4, a GLP-1R agonist, is capable of modulating the level of autophagy under hypoxic conditions in steatotic cells, thus influencing the fate of the cell. GLP-1R agonists have been shown to be protective in IRI of the heart (4, 6), which corroborates our finding of a protective role against necrotic and apoptotic cell death in IRI of the steatotic liver (20). In normoxia, our results are consistent with a previous report (44) that shows the protective effect of Ex4 by increasing autophagy.

The novel finding in our study is that Ex4 decreases hepatocellular damage while decreasing autophagy, demonstrated in vivo and in vitro. Furthermore, this is mechanistically proven by blocking the GLP1 pathway with Ex9-39, a competitive antagonist of Ex4, leading to a reversal of the protective effects. Although the presence of GLP-1R in liver is controversial (23, 56, 59), we previously demonstrated its presence and function (15, 20, 44), and we confirmed its presence by real-time PCR in the present study in mouse liver tissue (data not shown). We acknowledge that several signaling pathways are likely to be involved in this phenomenon.

The controversy over the role of autophagy in cell survival or cell death is ongoing, with many unanswered questions (9, 13, 28, 32). In the present study we show that autophagy is a critical player in the cell death pathway of a steatotic liver exposed to IRI. It is our premise that the GLP-1R agonist Ex4, a relatively safe and commercially available agent, has the potential for mitigating this hepatocellular injury, although the exact underlying mechanisms remain under investigation. In addition, since several different signaling pathways regulate the autophagic process (22), it should be of considerable significance and an exciting opportunity to design strategies to target one or more of these signaling pathways and, thus, mitigate hepatocellular injury.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant K08 DK-091506 (N. A. Gupta) and a grant from the Children's Disease Health and Nutrition Foundation (N. A. Gupta).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

N.A.G. and V.L.K. are responsible for conception and design of the research; N.A.G., V.L.K., C.A., A.K., and A.D.K. interpreted the results of the experiments; N.A.G. and V.L.K. drafted the manuscript; N.A.G., V.L.K., A.K., C.A., F.A.A., and A.D.K. edited and revised the manuscript; N.A.G. and V.L.K. approved the final version of the manuscript; V.L.K., R.J., A.S., A.K., and H.P. performed the experiments; N.A.G., V.L.K. and C.A. analyzed the data; V.L.K. prepared the figures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Emory+Children's Pediatric Research Center Cellular Imaging core and the Microsurgery core in the Department of Pediatrics, Robert P. Apkarian Integrated Electron Microscopy core, Emory University School of Medicine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altman BJ, Rathmell JC. Autophagy: not good OR bad, but good AND bad. Autophagy 5: 569–570, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amir M, Czaja MJ. Autophagy in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 5: 159–166, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Axe EL, Walker SA, Manifava M, Chandra P, Roderick HL, Habermann A, Griffiths G, Ktistakis NT. Autophagosome formation from membrane compartments enriched in phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and dynamically connected to the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol 182: 685–701, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ban K, Noyan-Ashraf MH, Hoefer J, Bolz SS, Drucker DJ, Husain M. Cardioprotective and vasodilatory actions of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor are mediated through both glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor-dependent and -independent pathways. Circulation 117: 2340–2350, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behrns KE, Tsiotos GG, DeSouza NF, Krishna MK, Ludwig J, Nagorney DM. Hepatic steatosis as a potential risk factor for major hepatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg 2: 292–298, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bose AK, Mocanu MM, Carr RD, Yellon DM. Myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury is attenuated by intact glucagon like peptide-1 (GLP-1) in the in vitro rat heart and may involve the p70s6K pathway. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 21: 253–256, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bursch W, Ellinger A, Gerner C, Frohwein U, Schulte-Hermann R. Programmed cell death (PCD) apoptosis, autophagic PCD, or others? Ann NY Acad Sci 926: 1–12, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardinal J, Pan P, Tsung A. Protective role of cisplatin in ischemic liver injury through induction of autophagy. Autophagy 5: 1211–1212, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Klionsky DJ. The regulation of autophagy—unanswered questions. J Cell Sci 124: 161–170, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clavien PA, Selzner M. Hepatic steatosis and transplantation. Liver Transplant 8: 980, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cole A, Armour EP. Ultrastructural study of mitochondrial damage in CHO cells exposed to hyperthermia. Radiat Res 115: 421–435, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuervo AM. Autophagy: in sickness and in health. Trends Cell Biol 14: 70–77, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Czaja MJ, Ding WX, Donohue TM, Friedman SL, Kim JS, Komatsu M, Lemasters JJ, Lemoine A, Lin JD, Ou JH, Perlmutter DH, Randall G, Ray RB, Tsung A, Yin XM. Functions of autophagy in normal and diseased liver. Autophagy 9: 1131–1158, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Degli Esposti D, Sebagh M, Pham P, Reffas M, Pous C, Brenner C, Azoulay D, Lemoine A. Ischemic preconditioning induces autophagy and limits necrosis in human recipients of fatty liver grafts, decreasing the incidence of rejection episodes. Cell Death Dis 2: e111, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding X, Saxena NK, Lin S, Gupta NA, Anania FA. Exendin-4, a glucagon-like protein-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, reverses hepatic steatosis in ob/ob mice. Hepatology 43: 173–181, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong H, Czaja MJ. Regulation of lipid droplets by autophagy. Trends Endocrinol Metab 22: 234–240, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emadali A, Muscatelli-Groux B, Delom F, Jenna S, Boismenu D, Sacks DB, Metrakos PP, Chevet E. Proteomic analysis of ischemia-reperfusion injury upon human liver transplantation reveals the protective role of IQGAP1. Mol Cell Proteomics 5: 1300–1313, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evankovich J, Zhang R, Cardinal JS, Zhang L, Chen J, Huang H, Beer-Stolz D, Billiar TR, Rosengart MR, Tsung A. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV limits organ damage in hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury through induction of autophagy. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 303: G189–G198, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans ZP, Ellett JD, Schmidt MG, Schnellmann RG, Chavin KD. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein-2 mediates steatotic liver injury following ischemia/reperfusion. J Biol Chem 283: 8573–8579, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta NA, Kolachala VL, Jiang R, Abramowsky C, Romero R, Fifadara N, Anania F, Knechtle S, Kirk A. The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, exendin 4, has a protective role in ischemic injury of lean and steatotic liver by inhibiting cell death and stimulating lipolysis. Am J Pathol 181: 1693–1701, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta NA, Mells J, Dunham RM, Grakoui A, Handy J, Saxena NK, Anania FA. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor is present on human hepatocytes and has a direct role in decreasing hepatic steatosis in vitro by modulating elements of the insulin signaling pathway. Hepatology 51: 1584–1592, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu Rev Genet 43: 67–93, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hnilicova J, Jirat Matejckova J, Sikova M, Pospisil J, Halada P, Panek J, Krasny L. Ms1, a novel sRNA interacting with the RNA polymerase core in mycobacteria. Nucleic Acids Res 42: 11763–11776, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaeschke H. Mechanisms of reperfusion injury after warm ischemia of the liver. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 5: 402–408, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaeschke H. Reperfusion injury after warm ischemia or cold storage of the liver: role of apoptotic cell death. Transplant Proc 34: 2656–2658, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain A, Lamark T, Sjottem E, Larsen KB, Awuh JA, Overvatn A, McMahon M, Hayes JD, Johansen T. p62/SQSTM1 is a target gene for transcription factor NRF2 and creates a positive feedback loop by inducing antioxidant response element-driven gene transcription. J Biol Chem 285: 22576–22591, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kathiria AS, Butcher LD, Feagins LA, Souza RF, Boland CR, Theiss AL. Prohibitin 1 modulates mitochondrial stress-related autophagy in human colonic epithelial cells. PLos One 7: e31231, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parzych KR, Klionsky DJ. An overview of autophagy: morphology, mechanism and regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal 20: 460–467, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klionsky DJ. Finding autophagy: it's a question of how you look at it. Autophagy 9: 267, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klionsky DJ, Baehrecke EH, Brumell JH, Chu CT, Codogno P, Cuervo AM, Debnath J, Deretic V, Elazar Z, Eskelinen EL, Finkbeiner S, Fueyo-Margareto J, Gewirtz D, Jaattela M, Kroemer G, Levine B, Melia TJ, Mizushima N, Rubinsztein DC, Simonsen A, Thorburn A, Thumm M, Tooze SA. A comprehensive glossary of autophagy-related molecules and processes (2nd ed.). Autophagy 7: 1273–1294, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobayashi S, Xu X, Chen K, Liang Q. Suppression of autophagy is protective in high glucose-induced cardiomyocyte injury. Autophagy 8: 577–592, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroemer G, Levine B. Autophagic cell death: the story of a misnomer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9: 1004–1010, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kubli DA, Gustafsson AB. Mitochondria and mitophagy: the yin and yang of cell death control. Circ Res 111: 1208–1221, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 132: 27–42, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loos B, Engelbrecht AM, Lockshin RA, Klionsky DJ, Zakeri Z. The variability of autophagy and cell death susceptibility: unanswered questions. Autophagy 9: 1270–1285, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matheson PJ, Hurt RT, Franklin GA, McClain CJ, Garrison RN. Obesity-induced hepatic hypoperfusion primes for hepatic dysfunction after resuscitated hemorrhagic shock. Surgery 146: 739–747, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsui Y, Takagi H, Qu X, Abdellatif M, Sakoda H, Asano T, Levine B, Sadoshima J. Distinct roles of autophagy in the heart during ischemia and reperfusion: roles of AMP-activated protein kinase and Beclin 1 in mediating autophagy. Circ Res 100: 914–922, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyer G, Czompa A, Reboul C, Csepanyi E, Czegledi A, Bak I, Balla G, Balla J, Tosaki A, Lekli I. The cellular autophagy markers beclin-1 and LC3B-II are increased during reperfusion in fibrillated mouse hearts. Curr Pharm Design 19: 6912–6918, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature 451: 1069–1075, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T. How to interpret LC3 immunoblotting. Autophagy 3: 542–545, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noyan-Ashraf MH, Momen MA, Ban K, Sadi AM, Zhou YQ, Riazi AM, Baggio LL, Henkelman RM, Husain M, Drucker DJ. GLP-1R agonist liraglutide activates cytoprotective pathways and improves outcomes after experimental myocardial infarction in mice. Diabetes 58: 975–983, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Padmasekar M, Lingwal N, Samikannu B, Chen C, Sauer H, Linn T. Exendin-4 protects hypoxic islets from oxidative stress and improves islet transplantation outcome. Endocrinology 154: 1424–1433, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rautou PE, Mansouri A, Lebrec D, Durand F, Valla D, Moreau R. Autophagy in liver diseases. J Hepatol 53: 1123–1134, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharma S, Mells JE, Fu PP, Saxena NK, Anania FA. GLP-1 analogs reduce hepatocyte steatosis and improve survival by enhancing the unfolded protein response and promoting macroautophagy. PLos One 6: e25269, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh R, Kaushik S, Wang Y, Xiang Y, Novak I, Komatsu M, Tanaka K, Cuervo AM, Czaja MJ. Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature 458: 1131–1135, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tacke F, Trautwein C. Controlling autophagy: a new concept for clearing liver disease. Hepatology 53: 356–358, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takagi H, Matsui Y, Sadoshima J. The role of autophagy in mediating cell survival and death during ischemia and reperfusion in the heart. Antioxid Redox Signal 9: 1373–1381, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanida I, Ueno T, Kominami E. LC3 and autophagy. Methods Mol Biol 445: 77–88, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Turkmen K, Martin J, Akcay A, Nguyen Q, Ravichandran K, Faubel S, Pacic A, Ljubanovic D, Edelstein CL, Jani A. Apoptosis and autophagy in cold preservation ischemia. Transplantation 91: 1192–1197, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vardanian AJ, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Molecular mediators of liver ischemia and reperfusion injury: a brief review. Mol Med 14: 337–345, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vetelainen R, van Vliet AK, van Gulik TM. Severe steatosis increases hepatocellular injury and impairs liver regeneration in a rat model of partial hepatectomy. Ann Surg 245: 44–50, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang D, Ma Y, Li Z, Kang K, Sun X, Pan S, Wang J, Pan H, Liu L, Liang D, Jiang H. The role of AKT1 and autophagy in the protective effect of hydrogen sulphide against hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Autophagy 8: 954–962, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang JH, Ahn IS, Fischer TD, Byeon JI, Dunn WA, Jr, Behrns KE, Leeuwenburgh C, Kim JS. Autophagy suppresses age-dependent ischemia and reperfusion injury in livers of mice. Gastroenterology 141: 2188–2199, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Y, Singh R, Massey AC, Kane SS, Kaushik S, Grant T, Xiang Y, Cuervo AM, Czaja MJ. Loss of macroautophagy promotes or prevents fibroblast apoptosis depending on the death stimulus. J Biol Chem 283: 4766–4777, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Y, Singh R, Xiang Y, Czaja MJ. Macroautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy are required for hepatocyte resistance to oxidant stress. Hepatology 52: 266–277, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Won H, Nandakumar V, Yates P, Sanchez S, Jones L, Huang XF, Chen SY. Epigenetic control of dendritic cell development and fate determination of common myeloid progenitor by Mysm1. Blood. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang PM, Liu YL, Lin YC, Shun CT, Wu MS, Chen CC. Inhibition of autophagy enhances anticancer effects of atorvastatin in digestive malignancies. Cancer Res 70: 7699–7709, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yin XM, Ding WX, Gao W. Autophagy in the liver. Hepatology 47: 1773–1785, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang Y, Moschetta M, Huynh D, Tai YT, Zhang W, Mishima Y, Ring JE, Tam WF, Xu Q, Maiso P, Reagan M, Sahin I, Sacco A, Manier S, Aljawai Y, Glavey S, Munshi NC, Anderson KC, Pachter J, Roccaro AM, Ghobrial IM. Pyk2 promotes tumor progression in multiple myeloma. Blood. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]