Abstract

To illuminate the evolution and mechanisms of actinobacterial complexity, we evaluate the distribution and origins of known Streptomyces developmental genes and the developmental significance of actinobacteria-specific genes. As an aid, we developed the Actinoblast database of reciprocal blastp best hits between the Streptomyces coelicolor genome and more than 100 other actinobacterial genomes (http://streptomyces.org.uk/actinoblast/). We suggest that the emergence of morphological complexity was underpinned by special features of early actinobacteria, such as polar growth and the coupled participation of regulatory Wbl proteins and the redox-protecting thiol mycothiol in transducing a transient nitric oxide signal generated during physiologically stressful growth transitions. It seems that some cell growth and division proteins of early actinobacteria have acquired greater importance for sporulation of complex actinobacteria than for mycelial growth, in which septa are infrequent and not associated with complete cell separation. The acquisition of extracellular proteins with structural roles, a highly regulated extracellular protease cascade, and additional regulatory genes allowed early actinobacterial stationary phase processes to be redeployed in the emergence of aerial hyphae from mycelial mats and in the formation of spore chains. These extracellular proteins may have contributed to speciation. Simpler members of morphologically diverse clades have lost some developmental genes.

Keywords: mycelial growth, polar growth, cell division, sporulation, nitric oxide, mycothiol

Introduction

Bacteria in the ancient phylum Actinobacteria have extraordinary diversity of function and form. They include pathogens of humans and other mammals (the agents of tuberculosis, leprosy, mycetomas, diphtheria, Whipple's disease, and skin, oral and vaginal infections of humans) and plants (potato scab, ratoon stunting disease of sugarcane); major agents of symbiotic nitrogen fixation (Frankia); industrially important producers of amino acids (Corynebacterium glutamicum); genera such as Streptomyces, Micromonospora, Saccharopolyspora and Actinoplanes that are the richest natural source of antibiotics and other secondary metabolites; probiotic bifidobacteria; and agents of bioremediation, notably rhodococci (Ventura et al., 2007). There is also growing interest in their frequent occurrence as plant endophytes and arthropod exosymbionts (Seipke et al., 2012).

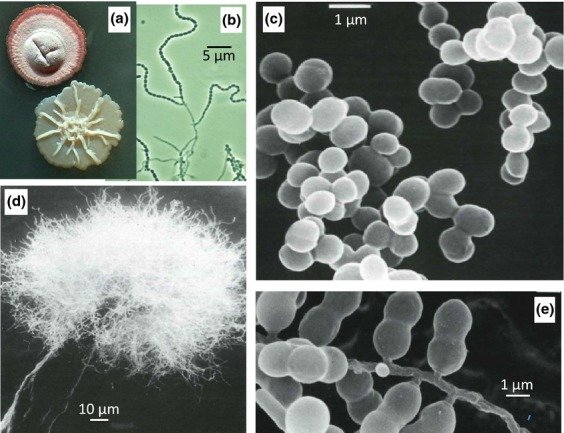

Actinobacteria are Gram-positive bacteria that typically have a high G + C content in their DNA. They range from simple cocci to the various complex mycelial forms found in some of the Actinomycetales order (Fig. 1). This morphological diversity is spectacularly illustrated in the ‘Atlas of Actinomycetes’ (Miyadoh, 1997). Mycelial organisms present particular problems for growth and development: their hyphae are intrinsically nonsymmetrical; special mechanisms must be needed to permit and control branching; and they must have some phase of fragmentation that permits dispersal. Often, the fragmentation of actinomycete hyphae leads to the formation of dessication-resistant spores, of a general type distinct from the endospores formed inside ‘mother cells’ of Bacillus spp. and other firmicute bacteria: they are formed directly by cell division from multigenomic hyphal compartments, followed by changes in the cell wall to permit rounding and thickening of the spore wall and the acquisition of resistance properties. These ‘exospores’ appear in or on a considerable variety of specialised morphological structures, including short hyphal side branches, large sporangia and specialised aerial hyphae that turn into long spore chains. In some genera, although not in Streptomyces, spores may be motile.

Fig. 1.

Morphological diversity of actinobacteria. (a) Colonies of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) wild type (upper) and bldA mutant (lower). (b) Phase contrast image of sporulating mycelium of S. coelicolor. (c) Micrococcus luteus. (d) Actinosynemma mirum. (e) Microbispora rosea. Images [c–e] are scanning electron micrographs taken from Miyadoh (1997), with permission.

Streptomycetes, the central subject of this article, are the most extensively studied mycelial actinobacteria. They are sporulating organisms whose considerable morphological complexity is interlinked with an extraordinary ability to make diverse secondary metabolites (Chater, 2011; Liu et al., 2013a). Two or three days after a spore germinates on agar media, the biomass-accumulating vegetative or substrate mycelium of the colony becomes covered with a fuzzy white aerial mycelium. The individual aerial hyphae grow to give rise to long unbranched tip cells often containing more than 50 copies of the genome. The tip cells are then divided into multiple prespore compartments by sporulation septation, during which synchronously assembled and regularly spaced FtsZ rings lead septal ingrowth. During sporulation septation, the uncondensed mass of chromosomes partitions into nucleoids, so that each prespore compartment contains a single copy of the genome. The change of cylindrical prespore compartments into ovoid spores involves remodelling and thickening of the cell wall, while inside the developing spore further changes contribute to the onset of dormancy, including chromosome condensation.

Three model species have provided nearly all the available experimental information about the molecular basis of the morphological development of streptomycetes. The most widely studied of these is the genetically amenable S. coelicolor A3(2) (Hopwood, 2007), while S. griseus (one of the first streptomycetes to be used as the source of a major antibiotic, streptomycin) has been particularly intensively studied for its production of, and responsiveness to, a hormone-like developmental signalling molecule, A-factor (Horinouchi, 2002, 2007). The third model species, S. venezuelae, an early industrial producer of chloramphenicol, has recently been taken up as a developmental model, because it sporulates rapidly, synchronously and comprehensively in submerged culture, in contrast to most streptomycetes, which sporulate gradually and nonsynchronously and do not form spores in submerged culture (Flärdh & Buttner, 2009; Bibb et al., 2012). This makes S. venezuelae especially suitable for sensitive biochemical, cytological and molecular studies of consecutive developmental states. The genomes of all three species have been sequenced (Bentley et al., 2002; Ohnishi et al., 2008; FR845719: for annotated presentation, see http://strepdb.streptomyces.org.uk), along with those of numerous other members of the genus.

A previous comparative genomic survey of actinobacteria (Ventura et al., 2007) was based on 21 sequences, encompassing 10 genera, and with many gaps in its phylogenetic coverage. When we began the analysis leading to this article in April 2011, about 100 further actinobacterial genomes had been sequenced and annotated to a level that made productive comparative analysis possible. The number had increased to 157 complete sequences and 474 in progress, in a recent and comprehensive review on the genome-based phylogeny of actinobacteria (Gao & Gupta, 2012). That review extended earlier work in which 28 ‘signature proteins’ peculiar to, and near-universal among, actinobacteria were identified, along with a further 48 peculiar to, and near-universal among, actinomycetes (Gao et al., 2006). These proteins form an important background to this review, and we summarise them in Table 1, using Streptomyces coelicolor gene designations (SCO numbers) as the key instead of those originally used (mainly from Mycobacterium leprae).

Table 1.

Conserved actinobacterial signature proteins/genes identified by Gao et al. (2006) and Gao & Gupta (2012)†. (A) The 26 most frequent actinobacterial signature proteins include at least six with likely developmental roles (asterisks). (B) Seven actinomycete signature proteins referred to in the text‡

| SCO number | ML number | Comments such as gene or protein name, function, conserved linkage, references, etc. |

|---|---|---|

| (A) | ||

| 5199 | 0642 | Often next to conserved gene for ‘epimerase/dehydratase’. Similar to SCO3407 (25% identity over 336 aa overlap), which is also very widespread and actinospecific, but is not listed in Gao et al. (2006). SCO3407 is neighboured by SCO3408 (= ML00211, actinospecific, widely conserved, predicted D-ala, D-ala carboxypeptidase, PBP4 class, similar to dacB of E. coli) and by a cluster conserved even in B. subtilis (SCO3406, possible MesJ-like cell division-associated ATPase; SCO3405, probable hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase; SCO3405, FtsH2, ATP-dependent protease) |

| 1997* | 1009 | Closely similar to ParJ. Function unknown, but structure established (Gao et al., 2009). May perhaps interact with ParA or the ubiquitous ParA2 (= SCO1772). Absent from nonactinomycete actinobacteria and from two actinomycetes, Trophyrema whipplei and Saccharopolyspora erythraea. |

| 5869 | 1029 | DUF3710 domain; probably cotranscribed with SCO5868 (3nt in between; dut, probable deoxyuridine 5′-triphosphate nucleotidohydrolase) and SCO5867 (phenylacetic acid thioesterase, Paa1). Linkage with dut conserved throughout actinomycetes |

| 1662* | 1306 | parJ. ParJ interacts with ParA (Ditkowski et al., 2010) |

| 3034* | 0760 | whiB, developmental regulatory gene (Fowler-Goldsworthy et al., 2011) |

| 5240* | 0804 | wblE, encodes WhiB-like protein of uncertain role, possibly essential in streptomycetes but not in C. glutamicum (Kim et al., 2005; Fowler-Goldsworthy et al., 2011) |

| 2196 | 0857 | 234 aa, probable integral membrane protein |

| 2169 | 0869 | 251 aa, DUF3034, probable integral membrane protein |

| 2947 | 1016 | 97 aa, DUF3039 |

| 5864 | 1026 | 98 aa; note conserved linkage of SCO5864 and 5869, and ML1026 and 1029 |

| 1381 | 2073 | 228 aa; present in all actinobacteria except Acidimicrobium ferrooxidans and Coriobacteriales. Removed by Gao & Gupta (2012) |

| 5855 | 2137 | 252 aa, DUF3071 |

| 4088 | 2204 | 84 aa, DUF3073 |

| 3854* | 0013 | crgA (whiP in S. avermitilis), 84-aa membrane protein, septation inhibitor, absent from nonactinomycete actinobacteria (Del Sol et al., 2003, 2006; Plocinski et al., 2011, 2012) |

| 3872 | 0007 | 185 aa, DUF3566, invariably very close to oriC |

| 1938 | 0580 | opcA; assembly of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (also in cyanobacteria: Hagen & Meeks, 2001; and next to the zwf2 gene); a less widely occurring paralogue, SCO6660, is downstream of zwf1 in S. coelicolor |

| 2078 | 0921 | 94 aa, possible transmembrane protein, invariably next to divIVA |

| 1421 | 1439 | rpbA, RNA polymerase-binding protein (Tabib-Salazar et al., 2013; Bortoluzzi et al., 2013; note that ML1439 was listed twice by Gao et al. (2006)) |

| 5601 | 1610 | 102aa, DUF2469, conserved linkage with SCO5602 |

| 4084 | 2207 | 437 aa. Note conserved linkage of SCO4084 and 4088, and ML2207 and 2204 |

| 3095* | 0256 | divIC; part of cell division apparatus, interacts with FtsL (Bennett et al., 2007; sequence divergence of DivIC orthologues in other bacteria took them beyond the threshold adopted by Gao et al., 2006; but they were removed by Gao & Gupta, 2012) |

| 3011 | 0775 | lpqB/Putative lipoprotein |

| 3031 | 0761 | 117 aa, DUF1025. Note conserved linkage of SCO3031 and another signature gene, SCO3034 (whiB) |

| 5169 | 0814 | 94 aa, DUF3107, possible ATP-binding protein |

| 2370 | 1649 | 159 aa, DUF3052, invariably next to gene for possible thiol-specific antioxidant protein |

| 4330 | 2142 | 308 aa, DUF3027 |

| (B) | ||

| 3375 | 0234 | lsr2/HNS-like DNA-bridging protein, iron-regulated in M. tuberculosis (Gordon et al., 2010) |

| 2097 | 0904 | 135 aa, DUF3040, part of spore wall-synthesising complex (Kleinschnitz et al., 2011) |

| 4179 | 2200 | 191 aa, cd07821, likely nitrobindin. NO or fatty acid-binding protein domain, structure known for M. tuberculosis (Shepard et al., 2007), conserved synteny with adjacent fur homologue |

| 1480 | 0540 | 107 aa, nucleoid-binding protein sIHF (Yang et al., 2012; Swiercz et al., 2013) |

| 1664 | 1300 | 265 aa, generally very close to mshC gene for mycothiol biosynthesis |

| 3097 | 2030 | rpfC/RPF, secreted protein, peptidoglycan binding, several paralogues |

| 4205 | 2442 | 168 aa, DUF2596, downstream of and overlapping mshA |

The gene identifiers listed by Gao et al. (2006) were for the Mycobacterium leprae genome. Here, we have listed S. coelicolor orthologues as defined by reciprocal best-hit BLASTP analysis. The function descriptions are based on the cited papers where given, but where no reference is given, the commentary is derived from synteny and conserved domain analysis carried out for this review, using StrepDB (http://strepdb.streptomyces.org.uk).

The remaining 39 actinomycete signature genes identified by Gao et al. (2006) were as follows (M. leprae, L. xyli or T. fusca designations given in brackets after SCO equivalent): SCO numbers: 0908 (Tfu_0365), 1372 (Lxx16410), 1383 (ML2075), 1437 (ML0561), 1653 (ML1312), 1665 (ML1299), 1929 (ML0589), 2105 (ML0898), 2153 (ML2446), 2154 (ML0876), 2197 (Lxx10090), 2391 (ML1781), 2460 (Tfu_1340), 2557 (Lxx08190), 2643 (ML1485), 2893 (ML0169), 2915 (ML1166), 2916 (ML1165), 3016 (Tfu_2498), 3030 (ML0762), 3576 (Lxx03620), 3647 (ML0284), 3822 (ML0115), 3902 (ML2687), 4043 (Tfu_0030), 4287 (ML1927), 4579 (ML2064), 4590 (Tfu_1240), 5145 (ML1067), 5167 (Tfu_0515), 5173 (ML0816), 5414 (ML1176), 5493 (ML1706), 5697 (Tfu_0751), 5766 (ML0986), 5866 (ML1027), 6030 (ML1041). One (ML2428A) was similar to SCO3327, but did not give a reciprocal blastp best hit, and another (ML0899) was absent from S. coelicolor, but present in S. avermitilis (SAV1313) and many other streptomycetes.

Our aim in this article is to combine comparative genomics, knowledge about Streptomyces development and growing information about gene function gleaned from other actinobacteria, particularly from the intensive focus of many researchers on the globally important pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis, to address several questions: What are the evolutionary origins of genes important for Streptomyces sporulation? Are the mechanisms leading to sporulation widely homologous in phylogenetically diverse actinobacteria, or did they evolve independently? Does the developmental process contribute to speciation? Are today's simple actinobacterial species primitive, or are they degenerate descendants of morphologically much more complex ancestors? What gave the ancestral ur-actinobacterium the potential for such morphological complexity in its modern descendants? And can studies of the development of complex actinomycetes assist our understanding of the cell biology of their simpler cousins?

Our analysis was aided by tabulating reciprocal blastp best hits of the translated products of each S. coelicolor gene with those of more than 100 actinobacterial genomes (http://streptomyces.org.uk/actinoblast/). We further analysed these tabulations using different approaches to identify proteins widespread among actinobacteria, but absent from other bacteria (as represented by E. coli and B. subtilis), in an extension of the work of Gao et al. (2006) and Gao & Gupta (2012). These approaches, which we do not describe in detail, included listing proteins in order of their frequency of representation in all actinobacteria analysed and analysing proteins present in both S. coelicolor and Micrococcus luteus, two morphologically and phylogenetically distinct organisms. Proteins of interest were further investigated using the NCBI Conserved Domain Database, which in several cases proved illuminating in relation to possible function. Throughout the article, the SCO identifiers used in the S coelicolor genome are used to designate genes and their protein products interchangeably. The rich genome sequence database used in this survey has caused us to modify some of the conclusions of an earlier exploration of this theme (Chater & Chandra, 2006) and to put forward some new ideas.

Taxonomy and phylogeny of actinobacteria, in relation to developmental complexity

The taxonomy of actinobacteria has been through several phases. Initially, the phylum consisted of mycelial bacteria termed actinomycetes. Genera were named in accordance with their different modes of sporulation (e.g. Micromonospora, Streptosporangium, etc.). Subsequently, the use of chemotaxonomy and numerical taxonomy led to the inclusion of some nonmycelial organisms in the phylum. Eventually, the sequencing of 16S ribosomal RNA began to provide a clearer phylogenetic basis for the taxonomy, and further genera of simple bacteria, such as Bifidobacterium, were shown to be related to the Actinomycetales, leading to the recognition of a more inclusive phylum, Actinobacteria. Using such a 16S RNA-based scheme, Zhi et al. (2009) divided Actinobacteria into five orders, one of which, the Actinomycetales, contained the great majority of families, the other four orders being made up of very few families: Rubrobacterales, including Rubrobacter and Conexibacter as genera with sequenced representatives; Acidimicrobiales, comprising only Acidimicrobium; Bifidobacteriales, including the genera Bifidobacterium and Gardnerella; and Coriobacteriales, including sequenced representatives in the genera Coriobacterium, Atopobium, Cryptobacterium, Eggerthella, Olsenella and Slackia. To maximise the ease of relating this article to the existing literature, we are using this taxonomic scheme. However, in the last few years, genome-level information has been employed in various ways to increase the resolution of actinobacterial phylogeny. Alam et al. (2010) combined several approaches, including gene order, to arrive at a well-resolved phylogeny, the main limitation of which was the lack of genome sequences representing the deepest branches. A key element in their analysis was the use of catenated sequences of 155 conserved proteins. A catenated set of 21 conserved protein sequences was used by Penn & Jensen (2012) to generate a tree from 186 actinobacterial genome sequences, while Gao & Gupta (2012) used 35 catenated conserved proteins to generate a very well-resolved tree from 98 actinobacterial genomes chosen to give comprehensive coverage of the phylum. Gao & Gupta (2012) went on to show that the distribution of taxon-specific signature indels (small insertions or deletions) and signature proteins fully supported the branch order of their tree, which we have therefore taken as the scaffolding for the rest of this article, but without adopting their revised taxonomic scheme (because it can be confusing for nonspecialists in relation to the pre-existing literature). It was pointed out by Gao & Gupta (2012) that the Coriobacteriales, previously included in Actinobacteria, lacked all the actinobacterial signature proteins and indels and should therefore be excluded from the phylum (a suggestion re-examined by Gupta et al., 2013). Likewise, we found that all the actinobacteria-specific genes that we discuss in this article were absent from Coriobacteriales. The term Actinobacteria is therefore taken to exclude Coriobacteriales throughout this article, although they are included in the reciprocal blastp best-hit analyses shown in some of the figures.

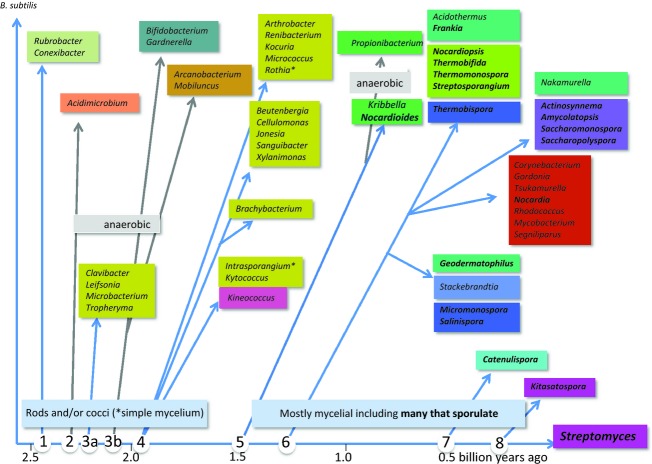

Because of our underlying emphasis on Streptomyces, we needed to re-present this phylogeny from the perspective of Streptomyces. To do this, we reorganised the tree of Gao & Gupta (2012) to show clearly the nodes at which various taxa shared a last common ancestor with Streptomyces, and aligned it with an estimated timescale derived from Battistuzzi et al. (2004) (Fig. 2). A complication of this scheme is the division of one of the Actinomycetales suborders, Micrococcineae, into three suborders, one of which has a more ancient origin than Bifidobacteriales (Gao & Gupta, 2012) and is indicated in Fig. 2 by node 3A. For the purposes of this article, we consider that node 4 of Fig. 2 represents the origin of Actinomycetales (i.e. actinomycetes).

Fig. 2.

The evolutionary path leading to Streptomyces. The diagram was derived from the phylogenetic tree in Fig. 2 of Gao & Gupta (2012), and the boxes correspond in colour to those used in Fig 3. Nodes 1 to 9 are reference points for the main text. Arrow lengths are not proportional to phylogenetic difference. Micrococcales genera showing a simple mycelium are indicated by asterisks, and sporulating mycelial genera are given in bold type. The approximate evolutionary timescale is based on Battistuzzi et al. (2004).

It can be seen in Fig. 2 that the actinobacteria originating from nodes 1 to 3B on the path to Streptomyces all show variations on a simple rod/coccus morphology and do not sporulate. These organisms include most of the obligately anaerobic genera, consistent with the earliest actinobacteria having preceded the major oxygenation of the atmosphere, around 2.3 Gya (Battistuzzi et al., 2004). The earliest branch of the order Actinomycetales (node 4) also leads almost exclusively to rod/coccus organisms (suborders Micrococcineae and Kineosporineae), with (rudimentary) mycelial growth being found only in Rothia and Intrasporangium. Extensive mycelium formation and sporulation occur in organisms originating at or after node 5, although some genera such as Corynebacterium and Mycobacterium arising from a later node do not show obvious developmental complexity (readers interested in mycobacterial dormancy or the controversial suggestion that mycobacteria can sporulate are referred to Gengenbacher & Kaufmann, 2012; Lamont et al., 2012). The simplest explanation for this discontinuity is that extensive and obligatory mycelial growth arose once and was closely associated with the evolution of sporulation, but such developmental complexity was lost from some lines later in evolution. We show later that loss of complexity is associated with the loss of several developmental regulatory genes.

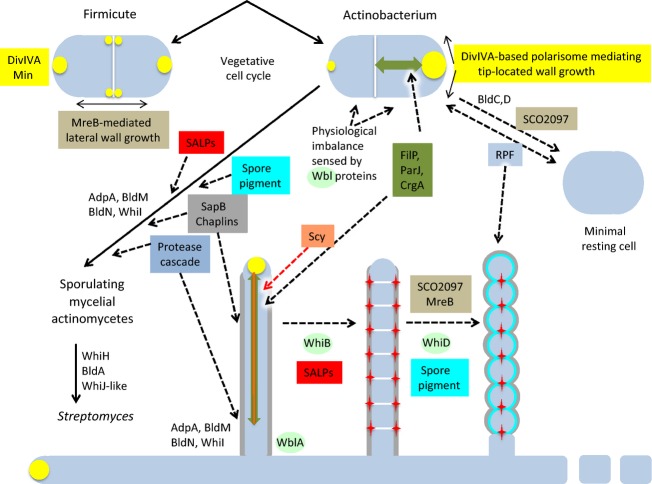

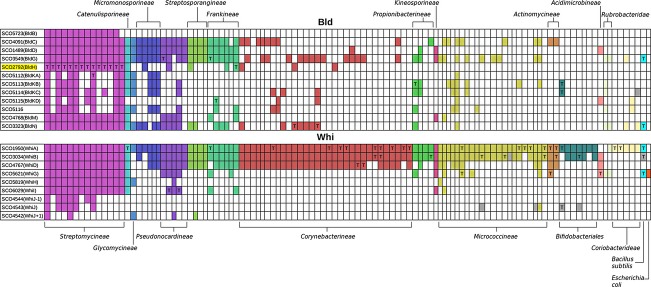

The Streptomyces sporulation regulatory cascade is built on ancient roots

Focused genetic studies of model streptomycetes have revealed several tens of key developmental genes (Flärdh & Buttner, 2009; Chater, 2011; McCormick & Flärdh, 2012). Mutations in some of these genes result in the loss of aerial mycelium formation, at least under most culture conditions (Merrick, 1976; Champness, 1988). Because of the bald appearance of the colonies, such genes are mostly designated bld. Another major phenotypic class of developmental mutants – those that form aerial hyphae but do not sporulate efficiently – identified the whi genes, so-called because the mutants fail to accumulate spore pigment in their aerial mycelium, which remains white on prolonged incubation (Hopwood et al., 1970; Chater, 1972). Here, we evaluate the phylogenetic distribution of many of these genes and interpret the results in terms of the evolution and mechanisms of Streptomyces development (Fig. 3: the legend to Fig. 3 includes information about the methods used to generate the data and how to access the full tables). Unless stated otherwise, orthologues of these genes are absent from B. subtilis and E. coli, so they may well be confined to actinobacteria. It appears from this that the key developmental regulatory roots of Streptomyces sporulation described in this section lie in some of the Whi proteins, while actions of the Bld proteins (also mostly regulatory) have come to be overlaid on the initiation of the whi gene cascade. These genes are discussed in the inferred order of their appearance during the c. 2.7 G years since the emergence of the first actinobacteria (Battistuzzi et al., 2004). We also identify some potentially interesting, but sometimes little-studied, genes whose patterns of occurrence across the actinobacteria are congruent with those of certain well-known developmental genes, and speculate on the significance of this congruence.

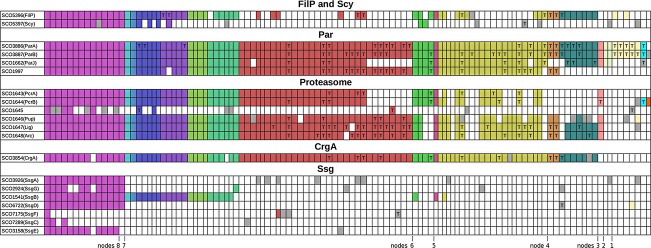

Fig. 3.

Distribution of probable orthologues of Bld and Whi proteins of Streptomyces coelicolor encoded in more than 100 actinobacterial genomes, as detected by reciprocal blastp best hits. Each column represents one genome, and the genomes are grouped and coloured to indicate subgroup relationships (e.g. Corynebacterineae columns, including Mycobacterium, Nocardia and Corynebacterium, were coloured Indian red). Grey boxes indicate reciprocal hits falling below the minimal criteria adopted for orthology. White boxes indicate the absence of a reciprocal hit. The yellow highlighted SCO genes contain a TTA codon, and the presence of TTA codons in apparent orthologues is indicated by a T in the coloured box. A similar display of reciprocal blastp analysis of the entire S. coelicolor genome against the 111 genomes, with links to StrepDB, is available at http://streptomyces.org.uk/actinoblast/. The tables at that site allow clicking onto any coloured box to show the gene identifier together with minimal annotation, as well as information about the length of the overlap and the percentage identity. The sources of genomes are listed in Table 1 of Gao & Gupta (2012). Organisms were as follows (in order across the tabulation). Magenta: Streptomycineae, S. lividans TK24, S. viridochromogenes DSM 40736, S. scabiei 87.22, S. sviceus ATCC 29083, S. avermitilis MA-4680, S. griseoflavus Tu4000, S. venezuelae ATCC 10712, S. griseus subsp. griseus NBRC 13350, S. hygroscopicus ATCC 53653, S. pristinaespiralis ATCC 25486, S. roseosporus NRRL 15998, S. albus G J1074, S. clavuligerus ATCC 27064, Kitasatospora setae KM-6054. Turquoise: Catenulispora acidiphila DSM 44928. Light blue: Stackebrandtia nassauensis DSM 44728. Dark blue: Salinispora, S. tropica CNB-440, S. arenicola CNS-205; Micromonospora, M. sp. L5, M. sp. ATCC39149, M. aurantiaca ATCC 27029. Purple: Saccharomonospora viridis DSM 43017; Saccharopolyspora erythraea NRRL 2338; Amycolatopsis mediterranei U32; Actinosynnema mirum DSM 43827; Thermobispora bispora DSM 43833. Yellow green: Streptosporangium roseum DSM 43021; Thermomonospora curvata DSM 43183; Thermobifida fusca YX; Nocardiopsis dassonvillei subsp. dassonvillei DSM 43111. Blue green: Acidothermus cellulolyticus 11B; Frankia, F. sp. EAN1pec, F. sp. CcI3, F. alni ACN14a; Geodermatophilus obscurus DSM 43160; Nakamurella multipartita DSM 44233. Rust red: Gordonia bronchialis DSM 43247; Nocardia farcinica IFM 10152; Segniliparus rotundus DSM 44985; Tsukamurella paurometabola DSM 20162; Rhodococcus, R. opacus B4, R. jostii RHA1, R. erythropolis PR4, R. equi 103S; Mycobacterium, M. vanbaalenii PYR-1, M. ulcerans Agy99, M. sp. Spyr1, M. sp. MCS, M. sp. KMS, M. sp. JLS, M. smegmatis str. MC2 155, M. marinum M, M. leprae Br4923, M. gilvum PYR-GCK, M. abscessus ATCC 19977, M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis K-10, M. avium 104, M. tuberculosis H37Rv, M. bovis AF2122/97; Corynebacterium, C. urealyticum DSM 7109, C. pseudotuberculosis FRC41, C. kroppenstedtii DSM 44385, C. jeikeium K411, C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 2, C. efficiens YS-314, C. diphtheriae NCTC 13129, C. aurimucosum ATCC 700975. Bright green: Nocardioides sp. JS614; Kribbella flavida DSM 17836; Propionibacterium, P. freudenreichii subsp. shermanii CIRM-BIA1, P. acnes KPA171202. Plum: Kineococcus radiotolerans SRS30216. Olive yellow: Beutenbergia cavernae DSM 12333; Cellulomonas flavigena DSM 20109; Brachybacterium faecium DSM 4810; Kytococcus sedentarius DSM 20547; Intrasporangium calvum DSM 43043; Jonesia denitrificans DSM 20603; Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis NCPPB 382; Leifsonia xyli subsp. xyli str. CTCB07; Microbacterium testaceum StLB037; Arthrobacter, A. sp. FB24, A. phenanthrenivorans Sphe3, A. chlorophenolicus A6, A. aurescens TC1, A. arilaitensis Re117; Kocuria rhizophila DC2201; Micrococcus luteus NCTC 2665; Renibacterium salmoninarum ATCC 33209; Rothias, R. mucilaginosa DY-18, R. dentocariosa ATCC 17931; Xylanimonas cellulosilytica DSM 15894; Sanguibacter keddieii DSM 10542; Tropheryma whipplei str. Twist. Brown: Mobiluncus curtisii ATCC 43063; Arcanobacterium haemolyticum DSM 20595. Cyan: Gardnerella vaginalis ATCC 14019; Bifidobacterium, B. longum NCC2705, B. longum DJO10A, B. dentium Bd1, B. bifidum PRL2010, B. animalis subsp. lactis Bl-04, B. adolescentis ATCC 15703. Pink: Acidimicrobium ferrooxidans DSM10331. Pale grey green: Conexibacter woesii DSM14684; Rubrobacter xylanophilus DSM9941. Beige: Atopobium parvulum DSM 20469; Cryptobacterium curtum DSM 15641; Eggerthella lenta DSM 2243; Olsenella uli DSM 7084; Slackia heliotrinireducens DSM 20476.

WhiG, an orthologue of an ancient sigma factor, regulates more recently acquired regulatory genes specific to aerial sporulation

Considering likely orthologues of all the bld and whi genes studied, none is more widespread across the bacterial kingdom than whiG. WhiG protein is a sigma factor critically involved in the decision of aerial hyphae to sporulate, and in its absence, colonies develop long, thin aerial hyphae and entirely fail to sporulate (Chater, 1972). It is orthologous with the extensively studied FliA of E. coli and SigD of B. subtilis, which are involved in regulating genes important for motility and chemotaxis, adhesion and invasion, some aspect(s) of cell wall remodelling and cyclic di-AMP hydrolysis (Helmann, 1991; Claret et al., 2007; Luo & Helmann, 2012). It is possible to envisage connections between these functions and Streptomyces sporulation, as they are mostly associated with the transition from growth as a biofilm to dispersal as planktonic single cells. However, FliA in E. coli and SigD in B. subtilis are both regulated by an antisigma factor, FlgM, that has the extraordinary property of being exported via the flagellar basal body during flagellum assembly. This is clearly not feasible for nonmotile streptomycetes, so it is not surprising that no homologue of this antisigma factor has been found in streptomycetes.

WhiG orthologues are widely but intermittently present in diverse actinobacteria, including some that are morphologically simple (Fig. 3). In most cases, these simpler organisms have been recorded as motile, the exceptions being Acidithermus and Rubrobacter (but Acidithermus does have a set of flagellar genes: Barabote et al., 2009). The only node 6-branch organism possessing WhiG, Nocardioides, is the only mycelial, sporulating organism known in this branch, and it also has a set of flagellar genes (Barabote et al., 2009). Even if motility functions are regulated by WhiG orthologues in these actinobacteria, no FlgM-like protein is encoded in any of their genomes. The whiG-like genes all show some local synteny, part of which is even retained in B. subtilis, so whiG seems to have been lost independently from several actinobacterial lines, rather than having been absent from the last common ancestor and then reacquired later in actinobacterial evolution as we previously suggested (Chater & Chandra, 2006).

RNA polymerase containing WhiG sigma directly activates two regulatory genes involved in slightly later stages in sporulation (whiH, Ryding et al., 1998; whiI, Ainsa et al., 1999). WhiI protein resembles response regulators, many of which are part of two-component systems in which activity of the response regulator is determined by its phosphorylation by a partner sensor kinase. WhiI, however, does not have a known partner kinase, being one of 13 ‘orphan’ response regulators present in S. coelicolor (Hutchings, 2007), and lacks key residues normally required for phosphorylation (Tian et al., 2007). It occurs almost exclusively in developmentally complex WhiG-containing actinomycetes and is absent from WhiG-containing, morphologically simple, motile actinobacteria; but both WhiG and WhiI are absent from many mycelial actinomycetes whose sporulation does not involve the formation of chains of spores on long aerial hyphae (Frankia, Micromonospora, Salinispora, Thermobispora, Nocardiopsis, Thermobifida, Streptosporangium and Thermomonospora). The other WhiG target regulatory gene, whiH, encodes an autoregulating GntR-like protein (Ryding et al., 1998; Persson et al., 2013) confined to streptomycetes and their closest relatives (Catenulispora and Kitasatospora).

In summary, the WhiG-dependent part of the Streptomyces sporulation regulatory cascade (as known until recently, see below) appears to have evolved in a stepwise manner, in which an early role for WhiG may have been to facilitate planktonic dispersal from biofilms (but there is still no analysis of roles for WhiG in motility and chemotaxis of motile simple actinobacteria). This made it potentially appropriate for activating the analogous process of sporulation of mycelial mats. The subsequent acquisition (and WhiG dependence) of WhiI and WhiH may have permitted increased provision of components needed in large amounts for sporulation septation and spore maturation, as in WhiI-dependent upregulation of genes needed for phosphoinositides for membrane synthesis (Tian et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2012) and an apparently WhiH-stimulated increase in the supply of FtsZ for sporulation septation (Flärdh et al., 1999, 2000).

whiA, part of a syntenous cluster of genes conserved across Gram-positive bacteria

Like WhiG (but no other sporulation regulator of S. coelicolor), WhiA orthologues are not confined to actinobacteria: one is present in most Gram-positive bacteria, including all actinobacteria except Acidimicrobium ferrooxidans. The structure and molecular function of WhiA have only been fruitfully studied recently. One of its two domains is an evolutionary relative of homing endonucleases, but lacks catalytic residues, and the other resembles the C-terminal domain of major sigma factors, which interacts with the -35 region of promoters (Knizewski & Ginalski, 2007; Kaiser et al., 2009). WhiA showed in vitro DNA binding to its own promoter and to a sporulation-activated promoter of the parAB operon (Kaiser & Stoddard, 2011), both of which are also WhiA-dependent in vivo (Jakimowicz et al., 2006). The whiA sporulation-specific promoter could be transcribed in vitro by WhiG-containing RNA polymerase (Kaiser & Stoddard, 2011), in contradiction of an earlier result (Ainsa et al., 2000). WhiA exerted a modest inhibitory effect on this transcription and showed some evidence of direct interaction with WhiG in a pull-down experiment involving the two purified proteins (Kaiser & Stoddard, 2011). These experiments, although not conclusive, provide the first suggestion of direct interplay between the WhiG- and WhiA-dependent parts of the sporulation regulatory cascade, previously thought to be separate (Chater, 1998; Flärdh et al., 1999).

whiA and the upstream three genes form a cluster that is highly conserved in actinobacteria and even in B. subtilis. This putative operon is probably responsible for a low level of whiA (SCO1950) expression during growth (Ainsa et al., 2000). The three upstream genes encode apparently unrelated deduced functions: the UvrC excinuclease (SCO1953); a NTPase that inactivates an sRNA (GlmZ) that regulates glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcN6P) synthase production in E. coli (NCBI conserved domain PRK05416; SCO1952); and a protein of unknown function (SCO1951) that is related to an enzyme of cytochrome F420 biosynthesis, LPPG:Fo 2-phospho-L-lactate transferase (pfam01933). There is also conspicuous synteny on the other side of whiA in actinobacteria (but this does not extend to B. subtilis): three genes for steps in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, phosphoglycerate kinase and triose phosphate isomerase, are always found next to whiA (or separated from it by one or two genes in some streptomycetes), along with secG, encoding part of the protein secretion system. If the notion of ‘guilt by association’ is applied to whiA, we may guess that it operates in the context of a physiological transition resulting from nutritional limitation, such that assimilated nutrients are redirected via gluconeogenesis to generate glucose-6-phosphate, which may then be converted into N-acetyl glucosamine for cell wall synthesis during aerial growth (perhaps also feeding into mycothiol biosynthesis, see below). This model does not account for all the conserved genetic linkage of whiA, but it is consistent with the apparent inability of aerial hyphae of whiA mutants of streptomycetes to stop growing and switch to sporulation (Chater, 1972).

WhiB and its paralogues: ancient actinobacterial nitric oxide-binding proteins

A phenotype identical to that of whiA mutants results from mutations in whiB (SCO3034), which encodes one of the actinobacterial signature proteins (Table 1A, Fig. 3). Mutation of the whiB orthologue (whmD) of Mycobacterium smegmatis indicated a likely role in cell division that could represent its core activity (Gomez & Bishai, 2000). There are strong two-way transcriptional influences (not necessarily direct) between whiA and whiB (Jakimowicz et al., 2006), but little is known about other possible WhiB targets.

WhiB is the exemplar of a paralogous family of small proteins (Wbl for WhiB-like: Soliveri et al., 1993, 2000; Fowler-Goldsworthy et al., 2011) that all possess an oxygen-sensitive [4Fe, 4S] cluster coordinated by four conserved cysteinyl residues (Jakimowicz et al., 2005a,b; den Hengst & Buttner, 2008; Alam et al., 2009; Saini et al., 2011, 2012). Orthologues of four other Wbl proteins (WblA, WblC, WhiD and WblE) occur in most actinomycetes (Figs 3 and 4), even though WblA and WhiD have developmental roles in S. coelicolor: WblA plays a key part in the transition of aerial hyphal initial branches to a sporulation-directed fate (wblA mutants have thin aerial hyphae often embedded in an extracellular matrix, with only occasional spore chains: Fowler-Goldsworthy et al., 2011); and mutants lacking WhiD have defects at a later stage, having thin-walled spores and uncontrolled sporulation septation (McVittie, 1974; Molle et al., 2000). Limited information is available about the roles of these two proteins in simpler actinobacteria: in Corynebacterium glutamicum, the WblA orthologue WhcA negatively influences the oxidative stress response (Choi et al., 2009); and the WhiD orthologue of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (WhiB3) is required for virulence (Saini et al., 2011). Some nonactinomycete actinobacteria also contain Wbl proteins, notably Bifidobacteriales, which have orthologues of two S. coelicolor Wbls, WhiB and WblK, respectively, termed WhiB2 and WblE in a recent survey (Averina et al., 2012). Using WhiB as a probe in one-way blastp searches of all the translated actinobacterial genomes, paralogues were sometimes very abundant: in an extreme case, Rhodococcus jostii possessed 30 wbl genes, all but five of them being almost specific to this organism or genus. The frequent finding of wbl genes in actinophages (e.g. Dedrick et al., 2013) and plasmids (e.g. SCP1; Fig. 4 and Bentley et al., 2004) makes it plausible that the large family of Wbl paralogues evolved in these elements, which would also serve as agents for their genome-specific lateral acquisition by diverse actinobacteria (Saini et al., 2011).

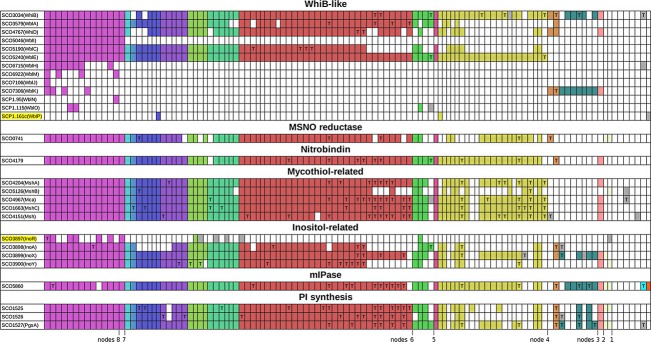

Fig. 4.

Distribution of WhiB-like (Wbl) proteins compared with proteins related to nitric oxide and mycothiol metabolism. The numbered nodes refer to Fig. 2. See Fig. 3 legend and text for further details.

Soliveri et al. (2000) suggested that WhiB and other Wbl proteins might interact with the major antioxidant thiol mycothiol (MSH), which is widespread among, and apparently confined to, actinobacteria (Fahey, 2012). Genomic searches confirmed that the MSH pathway is present in most Actinomycetales, but it is absent from nonactinomycete actinobacteria apart from Acidimicrobium ferrooxidans, even though wbl genes are present in many of these (Fig. 4). Thus, Wbl proteins can fulfil at least some function(s) in the absence of MSH. Nevertheless, another Wbl protein of M. tuberculosis, WhiB7 (=WblC), which is important in a global response to various antibiotics and other inhibitors and is widespread among actinobacteria, was found to control, directly or indirectly, the concentration of mycothiol (MSH+MSSM; Morris et al., 2005; Burian et al., 2012), and mycothiol-deficient mutants of Mycobacterium smegmatis (Rawat et al., 2002), Rhodococcus jostii (Dosanjh et al., 2008) and Corynebacterium glutamicum (Liu et al., 2013b) showed pleiotropic sensitivity to antibiotics similar to that of whiB7/wblC mutants of M. tuberculosis and Streptomyces lividans (Morris et al., 2005).

Several Wbl proteins have been shown to have specific DNA-binding activity (Rybniker et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2010; Stapleton et al., 2012). This can be enhanced by rapid, high-affinity interaction of the [4Fe, 4S] clusters with NO (Singh et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2010; Crack et al., 2011, 2013; Stapleton et al., 2012). Interestingly, we found two likely NO-related genes with a phylogenetic distribution similar (although not identical) to that of Wbl proteins (Fig. 4). One of these genes, SCO0741, encodes an orthologue of a mycobacterial protein that in vitro very rapidly reduces an NO conjugate (MSNO) of MSH to MSH sulphonamide, which in vivo is processed by M. smegmatis to MSSM (oxidised MSH) and nitrate (Vogt et al., 2003).

The second potentially NO-related protein with a very similar distribution, SCO4179, has clearcut similarity to nitrobindins of plants and animals (Bianchetti et al., 2010; Bianchetti et al., 2011). Nitrobindins are haem-containing proteins that bind NO in the absence of oxygen, and whose major structural features are conserved in the SCO4179 protein and its orthologues in other actinobacteria (Shepard et al., 2007; Bianchetti et al., 2010, 2011). A potential role for nitrobindin might be to transfer the NO groups of Wbl:NO complexes to MSH (Fig. 5). This would provide a means of recycling Wbl proteins to ensure that any burst of Wbl:NO-dependent transcription would be switched off once the Wbl-dependent gene expression cascade had been set in motion (Fig. 5). MSNO might in turn be denitrosylated by MSNO reductase. The MSSM formed in this process would then be reduced to MSH either by mycothiol reductase, which is present in most actinomycetes although apparently not in streptomycetes, or by some other, possibly less specific, thiol reductase. The MSNO reductase gene is immediately upstream of a gene (SCO0740) encoding a protein with homology to hydroxyacylglutathione hydrolases (Rawat & Av-Gay, 2007). This pairing is seen in almost all the actinobacteria that possess the MSNO reductase gene, with the genes usually overlapping by one nucleotide, indicating likely co-transcription and translational coupling. As glutathione is not present in most actinobacteria, an activity on a mycothiol derivative may be the real function of SCO0740 – perhaps in association with MSNO reductase.

Fig. 5.

Hypothetical scheme invoking the involvement of nitric oxide, mycothiol and Wbl proteins in major physiological or developmental decisions. It is supposed that early actinobacteria possessed the functions coloured grey green. They made phosphoinositol-containing phospholipids and used Wbl proteins to respond to nitrosative stress (the pink arrows indicate downstream regulatory events of different Wbl states). The putative nitrobindin may have aided the denitrosylation of Wbl:NO proteins. It is further suggested that the subsequent acquisition of mycothiol biosynthetic genes and MSNO reductase greatly increased the efficiency of NO removal and Wbl regeneration.

A further hint of a Wbl–NO connection has been found: in Corynebacterium glutamicum, the Wbl protein WhcA appears to interact with a protein showing very high similarity to nitronate monooxygenase (Park et al., 2011), an FMN-dependent fungal and bacterial enzyme that generates nitrite from alkyl nitronates (Gadda & Francis, 2010) and is found in nearly all actinobacteria (the S. coelicolor equivalent of this protein is SCO2553).

If MSNO was significant for early actinobacteria that emerged before the evolution of complex eukaryotes that produce NO as a defence and signalling molecule, NO may be an endogenous signal molecule in actinobacteria, which in Streptomyces fulfils roles in development (and in any other general physiological changes influenced by Wbl proteins). How might NO be generated, as the great majority of actinobacteria do not possess an obvious nitric oxide synthase? In plants, nitrate reductase has been implicated as a generator of endogenous NO that brings about the closure of stomata (Desikan et al., 2002), and nitrate and nitrite reductases generate NO in bacteria (Corker & Poole, 2003; Vine et al., 2011). Like the binding of NO by nitrobindin (Bianchetti et al., 2010), these reactions are anoxic. This may explain why the WhiB7 (=WblC)-dependent response of M. tuberculosis to antibiotics was surprisingly stimulated by reducing conditions (added dithiothreitol), but not by oxidative stress induced by the thiol oxidant diamide (Burian et al., 2012). It is interesting to note that in surveys of the thiol-oxidative stress responses mediated by the SigR system, only one of the genes discussed in this section (mshA, determining a step in MSH biosynthesis) was part of the SigR regulon (Paget et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2012). This is consistent with the idea of a partial separation of Wbl–NO–MSH physiology from responses to external oxidative stress (but does not exclude them from having some involvement).

The acquisition of MSH biosynthesis early in actinobacterial evolution seems to have been preceded by the means to generate an immediate precursor for MSH, myoinositol-1-phosphate (mIP), which is also absent from other bacteria. The relevant gene (SCO3899, inoA), is present in at least one nonactinomycete, Arcanobacterium haemolyticum, and is present in many actinomycetes, although surprisingly absent from corynebacteria and many Micrococcales. The source of inositol for MSH biosynthesis in these organisms is not known. When present, inoA is generally adjacent to its regulatory gene (inoR; Zhang et al., 2012). A similar distribution across actinobacteria was found for the biosynthetic genes of other inositol derivatives such as phosphoinositides (a three-gene cluster comprising SCO1527, putatively encoding phosphoinositide synthase, and SCO1525 and SCO1526, likely determinants of the further modification of phosphoinositides: Zhang et al., 2012; Fig. 4). From this, it seems likely that an early actinobacterial organism already possessed the ability to make phosphoinositides from glucose-6-phosphate and that the later acquisition of MSH biosynthesis, close to the time of emergence of the first actinomycetes, was made possible by the availability of the MSH precursor mIP (Fig. 5).

Finally in this section, we draw attention to genes for two further signature proteins listed in Table 1B: SCO1664 and SCO4205 are invariably closely linked to MSH biosynthetic genes (mshC, SCO1663, and mshA, SCO4204), so it is possible that their functions may also be implicated in the network proposed in Fig. 5.

Evolution of the developmental roles of two ancient genes, bldC and bldD

In B. subtilis, sporulation is an extreme response to nutrient limitation usually taken only when all other solutions fail (Narula et al., 2012). Likewise, in streptomycetes, it seems that many (but not all) of the bld gene products, which are nearly all regulatory, feed in information relevant to this drastic decision and ensure that the whi gene cascade operates only under fully appropriate circumstances.

The most ubiquitous bld genes are bldC, encoding an apparently single-domain small protein with a helix-turn-helix of the MerR type (Hunt et al., 2005), and bldD, which encodes a protein distantly related to SinR, a transition state regulator of B. subtilis (Elliot et al., 1998). Orthologues of both are found in most of the morphologically complex, large-genome actinomycetes. Simpler organisms (relatively anciently diverged from the Streptomyces line) seldom have both, and often (as in the case of anaerobic actinobacteria) have neither (Fig. 3). bldD orthologues always show high conservation and local synteny, but bldC orthologues are somewhat less highly conserved and are located among less extensively conserved genes, although some evidence of bldC synteny could often be detected (Chater & Chandra, 2006) (except where the BldC reciprocal blastp best hits were to proteins showing well under 50% identity – such cases may well be laterally acquired paralogues). Importantly, there are convincing orthologues of bldC in Rubrobacteriales and bldD in Acidimicrobium. Thus, both genes were present in very early actinobacteria, but each gene has been lost many times in the later evolution of the phylum. These losses may conceivably have contributed to the evolution of branches such as Micrococcineae (Node 4 of Fig. 2) and Corynebacterineae (a sub-branch from node 6).

The BldD regulon has been subjected to detailed analysis by immunoprecipitation of in vivo BldD–DNA complexes, which showed that BldD directly targets about 147 transcription units in vegetative, liquid-grown S. coelicolor (den Hengst et al., 2010). These include 42 regulatory genes, several of which are developmental (bldA, bldC, bldD, bldH, bldM, bldN, whiB, whiG). These are all repressed by BldD. Based on a consensus sequence derived from these ChIP-chip data, BldD recognition sequences were found upstream of many of the same genes not only in other streptomycetes, but also in other sporulating actinobacteria (den Hengst et al., 2010). Such species included Saccharopolyspora erythraea, an organism in which a constructed bldD mutant had a bald colony phenotype (Chng et al., 2008). Thus, BldD orthologues appear to coordinate development in diverse sporulating actinomycetes, perhaps preventing the expression of genes for morphological differentiation and antibiotic production during vegetative growth and connecting the regulons of other regulators of these processes (den Hengst et al., 2010). BldD orthologues in simpler actinomycetes might well have roles both during growth, to repress functions associated with entry into stationary phase, and in stationary phase, in coordinating the expression of different stationary phase regulatory genes.

Despite the extensive characterisation of BldD and its regulon, it is not understood why, if BldD represses developmental functions, bldD mutants are bald rather than hypersporulating (but see the paragraphs on BldN below); and there is no information about any signals that BldD might respond to (an initial search for possible proteins interacting with BldD was reported to have had negative results: den Hengst et al., 2010). It has been suggested that an interaction of BldD with another sporulation regulatory protein, BldB, could determine the rate of turnover of BldD (McCormick & Flärdh, 2012); but BldB is confined to streptomycetes, so it could not fulfil such a role in other complex actinomycetes such as Sac. erythraea (Fig. 3).

Evolution of the BldD regulon

Some BldD-regulated bld genes of S. coelicolor belong to classes of genes that are widespread and often represented by multiple paralogues in any one genome. For such genes, it can be difficult to be confident that reciprocal blastp hits between genomes are meaningful, particularly when the extent of amino acid identity falls well below levels that are typically seen for conserved housekeeping genes. For example, the general kind of anti-anti-sigma factor to which the BldG protein belongs is almost universally found among both Gram-positive firmicutes and actinobacteria; so the presence in some actinobacteria of BldG reciprocal best hits with identities only in the 20–40% range is relatively uninformative (in fact, such low-scoring hits did not show the local synteny seen with those having higher identities). Evidently, anti-anti-sigmas (and corresponding antisigmas) of this general class were present in the ur-actinobacterium, giving rise to the possibility of subtle control of sigma factor activity by signals that might include morphological checkpoints (as in the case of the spoIIAA/spoIIAB genes of B. subtilis; Piggot & Hilbert, 2004) or stress (as in the case of sigB of B. subtilis; Price, 2000). Indeed, BldG influences the activity of the stress-responsive sigma factor SigH in S. coelicolor (Sevcikova et al., 2010; Takano et al., 2011), and the anti-anti-sigma/antisigma/sigma interactions of this general type have considerable potential for promiscuity in Streptomyces (Kim et al., 2008a,b; Sevcikova et al., 2010; Takano et al., 2011).

The problem of recognising orthologues among large families of paralogues is less severe with the phylogenetically distinct ECF class of sigmas and their antisigma partners, which are more diverse than the class regulated through BldG-like cascades, and usually show high partner specificity (Staron et al., 2009). bldN, a direct target of BldD, encodes one of about 50 S. coelicolor ECF sigma factors (Bibb et al., 2000; den Hengst et al., 2010). At least in S. venezuelae, BldN is a direct activator of the genes for chaplins (and their associated rodlins): amphipathic proteins that assemble at air–water interfaces and coat incipient aerial hyphae, facilitating their emergence into the air (Bibb et al., 2012; see below). This emergence into the air has been suggested as a trigger for the sporulation pathway controlled by the whi genes (Claessen et al., 2006). Convincing BldN reciprocal hits (at well over 50% identity and with local synteny) were found only among morphologically complex genera of actinomycetes (Fig. 3), suggesting a close connection of bldN with the emergence of complexity (reciprocal hits with other actinobacteria were all at well under 40% identity and lacked discernible synteny).

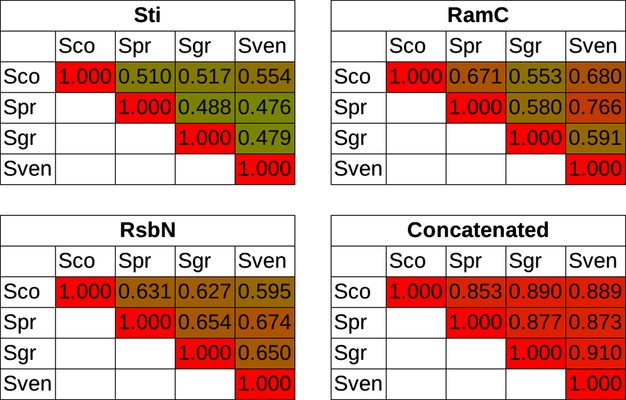

It has been demonstrated that, in S. venezuelae, an antisigma factor controlling BldN is encoded by the adjacent gene, termed rsbN (= SCO3324 in S.coelicolor; Bibb et al., 2012). In blastp analysis, a reciprocal best hit to rsbN is found next to nearly all bldN orthologues in actinomycete genomes; but, strikingly, the RsbN-like proteins are much more divergent than their BldN target or most other families of orthologous proteins of actinobacteria (Fig 6). We speculate that this may imply differences in the signal responsiveness of different RsbN proteins, thereby contributing to the differences between different organisms in the interplay of ecology and development: in other words, they may be potential agents of speciation.

Fig. 6.

High rates of divergence of three developmentally significant proteins. Pairwise blastp comparisons are shown between three developmental proteins of four Streptomyces spp: S. coelicolor (Sco), S. pristinaespiralis (Spr), S. griseus (Sgr) and S. venezuelae (Sven). High percentage identity is indicated by the intensity of red, and low identity by the intensity of green. A control table (‘Concatenated’) shows the comparisons for a concatenated set of seven universal proteins (AtpD, DnaA, DnaG, DnaK, GyrB, RecA, RpoB).

The rsbN gene of S. venezuelae has its own promoter, which is BldN-dependent, and is also a BldD target (den Hengst et al., 2010; Bibb et al., 2012). As a bldD mutant might therefore be expected to overexpress rsbN, the resulting increase in anti-BldN activity might interfere with the expression of BldN-dependent genes and contribute significantly to the bald phenotype of bldD mutants.

The most well-studied target of BldN is bldM, which encodes an orphan response regulator (Molle & Buttner, 2000). The distribution of convincing reciprocal hits to bldM is closely similar to that of bldN hits, suggesting that the BldN to BldM regulatory step was established very early in the evolution of actinomycete complexity. The distribution of BldM was even more closely similar to that of orthologues of another developmental orphan response regulator, WhiI (Fig. 3).

The key developmental regulator AdpA emerged along with complex mycelial growth and is bldA-dependent only in Streptomycineae

BldD targets also include adpA, known as bldH in S. coelicolor (den Hengst et al., 2010). AdpA has been most comprehensively described in S. griseus, in which it is the agent of the effects of the hormone-like A-factor (Horinouchi, 2002). It comprises a structurally characterised C-terminal AraC/XylS-like DNA-binding domain (Yao et al., 2012) and an N-terminal domain that may sense adenine nucleotides (Wolanski et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2013a). It plays a central role in the decisions leading to colony differentiation, notably affecting extracellular functions such as protease cascades, extracellular morphogenetic peptides and secondary metabolism (Akanuma et al., 2009; Chater et al., 2011; Higo et al., 2012), but also contributing to the regulation of DnaA-mediated chromosome replication initiation (Wolanski et al., 2012). In S. griseus, many hundreds of direct targets for AdpA have been defined, and it is suspected that the unusually low DNA-binding specificity of AdpA may permit the ready recruitment of new targets, leading to species-specific differences in AdpA regulons (Higo et al., 2012). The phylogenetic distribution of adpA-like genes is similar to that of bldN-like genes (Fig. 3), but there is little evidence of direct regulatory interplay between the two genes. Possibly, then, AdpA evolved to regulate aspects of developmental physiology complementary to those regulated by BldN (if so, one might anticipate that some cross-checks between the two regulons will eventually be discovered).

The regulation of adpA in streptomycetes is remarkably complex (reviewed in detail in Liu et al., 2013a). It involves at least three levels of control: transcriptional [autorepression (Kato et al., 2005), repression by BldD (den Hengst et al., 2010), repression by gamma-butyrolactone-binding proteins (Horinouchi, 2007; Xu et al., 2009)]; mRNA processing by RNaseE (Xu et al., 2010); and mRNA translation (Nguyen et al., 2003; Takano et al., 2003). Translational regulation is via a very rare UUA codon in the adpA mRNA, falling between the segments encoding the two domains of AdpA. UUA is the only one of the six leucine codons to comprise only A and U residues, so the corresponding TTA codon is comparatively rare in GC-rich genomes – it occurs in only 147 chromosomal genes in S. coelicolor (Li et al., 2007). UUA codons have a special regulatory role in Streptomyces, as indicated by the finding that mutants (bldA) in the gene for the UUA-reading tRNA grow well, but fail to form aerial mycelium or some antibiotics (Merrick, 1976; Lawlor et al., 1987). adpA is the only gene that has a TTA codon in all the streptomycetes analysed (Fig. 3; Table 2; Chater & Chandra, 2008), a feature also found in the adpA orthologue in Kitasatospora setae. The TTA codon in adpA was shown by mutagenesis to be the main (but not entire) cause of the Bld phenotype of bldA mutants of S. coelicolor (Nguyen et al., 2003; Takano et al., 2003). A study of S. griseus and S. coelicolor has shown that the abundance of bldA tRNA is important in determining whether AdpA reaches levels sufficient to activate development and, remarkably, that there is a mutual feedforward mechanism in which AdpA activates bldA transcription (Higo et al., 2011). However, the adpA-like genes of other actinomycetes, including Catenulispora acidiphila (the closest genome-sequenced relative of Streptomyces and K. setae), are nearly all TTA-free (in the single exception, Nakamurella multipartita, the TTA codon is not located in the interdomain-coding region, but close to the 3′-end of the gene). Thus, bldA-adpA interplay was apparently established after node 7 (Fig. 2), branching to Catenulispora, but before the Streptomyces and Kitasatospora lines diverged (node 8). Indeed, the broader developmental significance of bldA may not extend beyond Streptomycineae, as in non-Streptomycineae genomes TTA codons do not show the positional bias towards the start of genes that is observed in streptomycetes, and sometimes occur in conserved growth-associated genes (Chater & Chandra, 2008). Interestingly, there is a strong target for BldD binding within bldA (den Hengst et al., 2010).

Table 2.

Streptomyces genes or gene clusters that frequently contain TTA codons*

| SCO number of gene *asterisk means TTA codons are absent from the S. coelicolor gene | Function | Fraction of TTA-containing orthologues among 14 Streptomyces genomes (see note) | K. setae orthologue, accepting > 40% identity (TTA present?) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0381*;0382*;0383 | Enzymatic modifications | 6/12; 5/9; 2/10 | – |

| 0683*;0684*;0685* | Unknown | 2/12; 4/13; 2/13 |

67090 (–) *67100 (–) *67110 (–) |

| 1187(celB);1188* (celS2*) | Cellulose utilisation | 6/13; 7/14 | – *59340 (–) |

| 1242 | DNA-binding regulatory protein (WhiJ-like) | 9/11 | 58780 (–) |

| 1256* | Unknown | 6/10 | – |

| 1434 | Secreted AAA ATPase | 8/13 | 11520 (–) |

| 1592 | ADPribose pyrophosphatase | 8/12 | 41440 (–) |

| 1980 | Possible antisigma factor (AbaA-like) | 9/14 | – |

| 2426 | Regulatory | 8/14 | – |

| 2567*; 2568* | Competence operon | 3/11; 5/13 |

25860 (TTA) *25870 (–) |

| 2792 (adpA) | Major developmental regulator | 14/14 | 26930 (TTA) |

| 3195* | Unknown | 5/14 | – |

| 3423 | Possible antisigma factor (AbaA-like) | 12/14 | 17120 (TTA) |

| 3550* (widespread among actinobacteria) | Helicase | 6/14 | 35850 (–) |

| 3919* (abaB*) | LysR-like regulator of antibiotic biosynthesis | 7/13 | – |

| 3943* (rstP*) | LacI-like regulator | 5/14 | 40040 (–) |

| 4114 (widespread among actinobacteria) | Sporulation-associated protein (ankyrin-like repeats) | 9/14 | 43220 (–) |

| 4263 | LuxR-like regulator | 8/11 | – |

| 4395 | Hydroxylase | 12/14 | – |

| 5203 | 6/14 | 49090 | |

| 5460 | Possible antisigma factor (AbaA-like) | 6/14 | 50850 (TTA) |

| 5495 | Cyclic di-GMP cyclase/phosphodiesterase | 7/14 | 51100 (TTA) |

| 5970 | 6/13 | 26520 | |

| 6156* | Possible antisigma factor (AbaA-like) | 5/14 | 19600 (–) |

| 6245* | Unknown | 5/13 | – |

| 6476 | Unknown | 7/14 | – |

| 6681(amfC); 6685* (amfR*) | SapB biosynthetic enzyme; regulator of SapB biosynthesis | 2/12; 7/12 | – |

| 7251 | Possible phosphotransferase | 10/12 | 16190 |

| 7465 (cvnC13) | Component of conservon | 9/12 | 37840 (TTA) |

Throughout, examples included had a TTA codon in at least five genomes other than S. coelicolor (arbitrarily chosen as a level likely to indicate adaptive value). The table includes gene clusters likely to share a physiological role, selected because of the frequent occurrence of a TTA codon in one or another gene of the cluster.

Previously unnoticed aspects of the occurrence of conserved TTA codons

Earlier analyses had indicated that most of the S. coelicolor TTA-containing genes were absent from the few other Streptomyces genomes then available, and where the genes were conserved, the TTA codons often were not (Li et al., 2007; Chater & Chandra, 2008). With the availability of more genome sequences, it became possible to make a more sensitive search for orthologues of the 147 S. coelicolor TTA-containing genes (or in some cases gene clusters). We identified 19 that were widespread and frequently TTA-containing in 13 other Streptomyces genomes (Table 2). In addition, a further 10 genes or gene clusters frequently had TTA codons, even though their S. coelicolor orthologues were TTA-free (asterisks in Table 2). As 27/29 of the TTA-containing genes/clusters were found only in Streptomycineae, we infer that these genes and their TTA codons have adaptive value to streptomycetes and not to other actinobacteria. As shown in Table 2, about half of these genes encode proteins likely to be closely implicated in gene regulation or signal transduction, although their targets are mostly unknown. They include five conserved paralogues of genes found in the whiJ cluster (see below for further discussion) and gene sets for highly modified oligopeptides that contribute significantly to the ability of aerial hyphae to grow into the air (such as SapB, also discussed below).

Evolution of the multigene whiJ system, which represses development, and its abundant paralogues

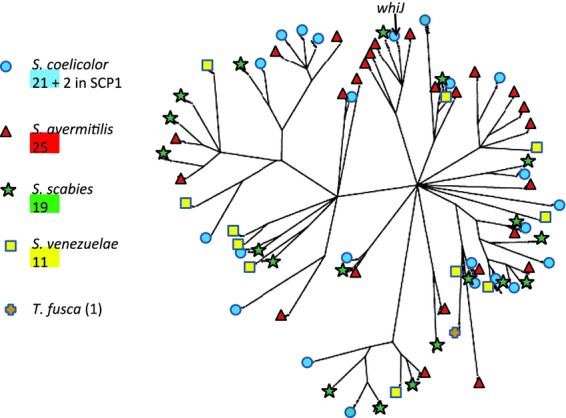

The central feature of the complex whiJ locus of S. coelicolor is the whiJ gene (SCO4543) for a deduced DNA-binding protein (Gehring et al., 2000; Ainsa et al., 2010). Most of the 24 paralogues of whiJ in the S. coelicolor chromosome are associated with one or both of two kinds of immediately neighbouring genes, one kind encoding very small DNA-binding proteins (i.e. like SCO4542) and the other encoding proteins with features like antisigma factors (e.g. SCO4544) (Gehring et al., 2000; Ainsa et al., 2010). whiJ-like genes are widely present in complex actinobacteria, but they are absent from morphologically simple ones (corynebacteria, mycobacteria, rhodococci, propionibacteria and micrococci except Beutenbergia and Intrasporangium) and from nonactinobacterial bacteria. These genes are often clustered with one or both types of whiJ-associated genes. Most mycelial actinomycetes have two or three WhiJ paralogues, but K. setae has five, and all streptomycetes have more than 10, sometimes more than 20. Phylogenetic analysis of WhiJ paralogues from four well-studied streptomycetes is shown in Fig. 7. The branching pattern is consistent with underlying sequential gene duplication events in an early progenitor of the four streptomycetes, followed by lineage-specific further divergence and duplication events. Phylogenetic analyses of the two whiJ-associated gene families gave broadly similar patterns, supportive of the idea that the genes in each cluster co-evolved (results not shown). WhiJ paralogues in S. coelicolor vary considerably in their conservation in other organisms. One (SCO3421) was present in nearly all complex actinomycetes, and the adjacent gene encoding a likely antisigma factor nearly always contained a TTA codon in Streptomycineae (but in no other groups). Another present in all Streptomycineae (SCO4441) was also widespread among other complex actinomycetes. Four others were found in all or nearly all Streptomycineae but no other groups (SCO1242, 1979, 2513, 6236), among which a TTA was present in SCO1242 and in the antisigma factor gene next to SCO1979. Future studies might profitably focus on these six relatively long-established clusters. Twelve other S. coelicolor whiJ-like genes were represented in around half of streptomycetes (SCO2381*, 2865, 2869*, 3365*, 4176, 4301, 4678, 4998, 6129, 6537, 6629*, 7579) [asterisks indicate occurrence also in some other complex actinomycete(s)]; while seven others were found in four or fewer streptomycetes (SCO0704, 2246, 2253, 4543, 5125, 6003, 7615). TTA codons were not associated with any of the last 19 genes mentioned or their associated genes.

Fig. 7.

Phylogenetic analysis of WhiJ and its paralogues in four streptomycetes and another complex actinomycete. Genes encoding WhiJ paralogues were identified by probing translated gene products of the genomes of four streptomycetes [S. coelicolor A3(2) (blue circles); S. avermitilis (red triangles); S. scabies (green stars); S. venezuelae (yellow squares)] and Thermobifida fusca (brown crosses). The tree represents a phylogenetic analysis using PHYLIP (Felsenstein, 1989, 2005).

Certain mutations in whiJ gave rise to a white-colony appearance caused by a deficiency in sporulation, although the complete deletion of whiJ had no obvious phenotypic consequences (Ainsa et al., 2010). A mutant lacking the whiJ-neighbouring gene SCO4542, encoding a predicted small DNA-binding protein, had a bald colony phenotype and overproduced the pigmented antibiotic actinorhodin. This phenotype was entirely suppressed by the co-deletion of whiJ itself. Putting these observations together, it was suggested that WhiJ acts mainly to repress reproductive development until a suitable signal has been perceived via the SCO4542 DNA-binding protein, which would then directly interact with WhiJ to relieve repression (Ainsa et al., 2010). It is thought that WhiJ mediates its effects both on the emergence of aerial hyphae and, separately, on their further differentiation into spore chains. There is no information about the direct or indirect targets of WhiJ regulation or about the role of the antisigma-like protein (SCO4544).

The apparently repressing action of the whiJ locus raises the possibility that some or all of its paralogues may also act as developmental brakes. If so, it may be that during ‘normal’ colony development on laboratory media, these brakes are all off – in other words, all relevant checkpoints have been passed, and the WhiJ-like proteins are not repressing their target genes. The acquisition of additional clusters would presumably confer species-specific environmental adaptations. As different streptomycetes vary in their ability to develop normally on different media, it is possible that this (partly) reflects differences in the complement of WhiJ-like signal transduction cascades. The strikingly reduced number of paralogues in S. venezuelae (one of several streptomycetes that lack a cluster orthologous to whiJ itself) may underpin the ability of S. venezuelae to sporulate exceptionally readily and comprehensively even in submerged culture, which has led to its adoption as a model system for development (Flärdh & Buttner, 2009; Bibb et al., 2012). Like the wbl genes described earlier, whiJ-like clusters are also found in plasmids (Bentley et al., 2004), permitting horizontal transfer. Interestingly, one of the ‘classical’ bld genes, bldB, encodes a diverged member of the SCO4542 family, but is an ‘orphan’ lacking neighbouring whiJ- or SCO4544-like genes. It is curious that bldB is the only classical bld gene to be confined to, yet universal among, streptomycetes (Fig. 3). We speculate that the bald phenotype of bldB mutants could imply a promiscuous interaction of BldB with WhiJ-like proteins encoded elsewhere in the genome and that this may be connected with the large numbers of such proteins found in streptomycetes.

Special features of actinobacterial cell biology have contributed to the evolution of developmental complexity in Streptomyces

Cell growth and division in actinobacteria were recently thoughtfully reviewed by McCormick & Flärdh (2012) and Letek et al. (2012). Here, we consider the part played in these processes by conserved actinobacterial proteins, including some of the actinobacterial signature proteins in Table 1.

The origins of mycelial growth: actinobacteria are unusual in predominantly using polar growth

At least in streptomycetes, corynebacteria and mycobacteria, cells grow by the insertion of peptidoglycan precursors at cell poles, guided by large, pole-located complexes of a coiled-coil-containing protein, DivIVA (Flärdh, 2003; Flärdh, 2010; Letek et al., 2008). The actinobacterial divIVA gene is nearly always located immediately next to an actinobacterial signature gene encoding a small probable membrane protein (SCO2078, Table 1a). It is an interesting possibility that this protein plays a part in the adaptation of DivIVA to polar growth in actinobacteria.

In Bacillus subtilis and other rod-shaped firmicutes (nonactinobacterial Gram-positive bacteria), DivIVA has a different role: it is involved in selection of the division site midway between opposite cell poles. Nevertheless, in such firmicutes, DivIVA is located at both poles, at least partly because of an affinity for concave membrane surfaces (Strahl & Hamoen, 2012). In these organisms, DivIVA binds the cell-division-inhibitory MinJDC protein complex – a mechanism that ensures that the cell centre contains the lowest concentration of Min proteins, so that cell division is medial. At firmicute cell division, DivIVA accumulates at the nascent septum, and upon cell separation, the new and old poles have similar amounts of DivIVA (Bramkamp & van Baarle, 2009).

In contrast, DivIVA does not accumulate rapidly at nascent septa in rod-shaped actinobacteria such as corynebacteria or mycobacteria, so newborn cells have an intrinsic asymmetry with respect to polar DivIVA complexes. In M. tuberculosis, the lag in formation of a full-sized DivIVA complex at the new pole is in fact very long – it is comparable with the interval between cell divisions, as shown by fluorescence microscopy of DivIVA::GFP fusions (Kang et al., 2008). This may reflect the complexity of the tip-organising complex (‘polarisome’: Hempel et al., 2012) that assembles round DivIVA and includes cytoskeletal elements and the cell wall biosynthetic apparatus (Holmes et al., 2013). The asymmetry in DivIVA distribution underpins a striking asymmetry in cell division observed by live-cell imaging of mycobacterial cells confined to microfluidic chambers (Aldridge et al., 2012): cells grow at just one pole, which is inherited stably; the newborn cells that lack an active pole take significant time to form one, and cell division depends on time rather than cell dimensions. As a result, the population of progeny cells in a very young microcolony is physiologically heterogeneous, different cell types even differing in their patterns of sensitivity to antibiotics (Aldridge et al., 2012).

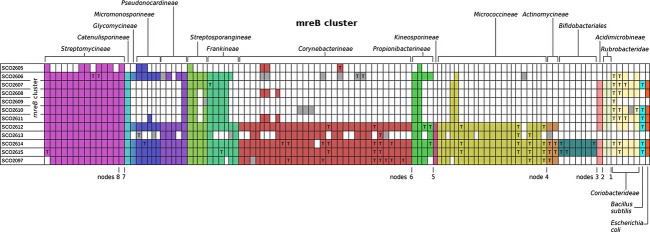

Comparative genomic analysis suggests that DivIVA-mediated apical growth is typical of actinobacteria, as, on one hand, divIVA is universally conserved (always located close to the cluster containing ftsZ and other genes concerned with division and cell wall biosynthesis); while, on the other hand, the mre gene cluster (which mediates lateral cell wall growth in nonactinobacterial rod-shaped bacteria including E. coli and B. subtilis) is absent from nearly all rod-shaped or coccal actinobacterial genera originating from nodes 3 and 4 of Fig. 2 (Fig. 8). Actinobacteria on the deepest branches (nodes 1 and 2) do have the mre cluster, so it is not possible to infer which growth mode they might use. Although coccal actinobacteria also possess DivIVA, they may possibly grow in a DivIVA/MreB-independent manner, as in staphylococci: there, peptidoglycan growth is confined to the septum, which becomes remodelled from a circular to a hemispherical form during cell separation (Touhami et al., 2004).

Fig. 8.

The mre gene cluster is absent from most simple actinobacteria. The reciprocal blastp best-hit tabulation includes the region from SCO2605 to SCO2615. The numbered nodes refer to Fig. 2. See Fig. 3 legend and text for further details. The mre gene (SCO2611) is part of a cluster (SCO2607-2611) present in all streptomycetes and morphologically complex actinomycetes, but absent from nearly all mycobacteria and corynebacteria (rust red), and from members of the Micrococcineae (olive yellow), Bifidobacteriales (dark green) and Rubrobacterideae (brown). Interestingly, the adjacent gene SCO2606 (encoding a likely radical SAM enzyme related to those involved in tRNA methylation) shows a very similar distribution. The Figure also shows the distribution of hits to the MreB-associated actinobacterial signature protein SCO2097 (Kleinschnitz et al., 2011).

What are the possible adaptive benefits of the two known growth modes of rod-shaped bacteria? The lateral wall growth of rod-shaped firmicutes may permit more efficient population growth, because the near-symmetry of growth and division allows both daughter cells to progress equally rapidly to subsequent divisions. In contrast, the asymmetry implicit in polar growth of rod-shaped actinobacteria has the potential to improve population resilience, because daughter cells have significantly different physiology, including different susceptibilities to some antibiotics (Aldridge et al., 2012). In the event of predivisional actinobacterial cells with three or more compartments (an apparent example of this may be seen in Fig. 5A of Singh et al., 2013), the tip-less compartments would have only nongrowing wall on their surface, with high levels of cross-linking. This might have enhanced survival value during exposure in the natural environment to physical stress, chemical or enzymatic attack of the wall itself, chemical or biochemical poisons (such as antibiotics produced by neighbouring organisms) and attack by bacteriophages. This increased resistance may have been a driving force for the evolution of mycelial growth.

A key requirement for the evolution of mycelial growth is a mechanism for cellular branching. This has become clarified by the discovery that, as a Streptomyces tip extends, it acquires increasing amounts of DivIVA (perhaps this is in some proportion to the number of genome copies in the tip compartment) and eventually splits, part remaining at the tip and part adhering to the lateral wall, which is thereby marked as a position of future branch emergence (Hempel et al., 2008; Flärdh et al., 2012). In a manner reminiscent of the situation already described for new poles in mycobacteria, branch emergence is not usually immediate, perhaps because the incipient polarisome has to be built up to some critical mass and/or organisation. However, new mycobacterial poles must be nucleated with DivIVA de novo, whereas mycelial branches are nucleated by the residue of a split polarisome, which may be a more avid target for DivIVA than septa.

Streptomyces polarisome splitting requires the activity of a serine/threonine protein kinase, AfsK, which phosphorylates DivIVA (Hempel et al., 2012). AfsK orthologues are present only in streptomycetes and K. setae, with a very weak hit also in Catenulospora acidiphila. How do other mycelial actinomycetes control branching? Most probably, by the action of other protein kinases on DivIVA – even in the nonbranching mycobacteria, DivIVA (=Wag31) is subject to phosphorylation during cell growth, but by serine/threonine protein kinases different from AfsK (Jani et al., 2010).

To achieve full mechanical strength, hyphae require FilP, a cytoskeletal coiled-coil protein that forms filaments along the hyphae (Bagchi et al., 2008). Orthologues of FilP appear to be very widespread among actinobacteria, including many morphologically simple organisms that diverged from the Streptomyces line early in evolution (e.g. bifidobacteria), but FilP is absent from coccal organisms, with the exception of Kineococcus radiodurans (Fig. 9). Thus, FilP is an ancient protein that may be important in generating resilient cylinders from the hemispherical nascent peptidoglycan emanating from poles. In streptomycetes, this involves a direct interaction with DivIVA (Fuchino et al., 2013). However, FilP is also apparently absent from corynebacteria and most mycobacteria. Possibly some other protein substitutes for it, or the sequence divergence of FilP in these organisms may be too great for identification by reciprocal blastp best-hit analysis.

Fig. 9.