SUMMARY

The sorting of signaling receptors into and out of cilia relies on the BBSome, a complex of Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS) proteins, and on the intraflagellar transport (IFT) machinery. GTP loading onto the Arf-like GTPase ARL6/BBS3 drives assembly of a membrane-apposed BBSome coat that promotes cargo entry into cilia, yet how and where ARL6 is activated remains elusive. Here, we show that the Rab-like GTPase IFT27/RABL4, a known component of IFT complex B, promotes the exit of BBSome and associated cargoes from cilia. Unbiased proteomics and biochemical reconstitution assays show that, upon disengagement from the rest of IFT-B, IFT27 directly interacts with the nucleotide-free form of ARL6. Furthermore, IFT27 prevents aggregation of nucleotide-free ARL6 in solution. Thus, we propose that IFT27 separates from IFT-B inside cilia to promote ARL6 activation, BBSome coat assembly and subsequent ciliary exit, mirroring the process by which BBSome mediates cargo entry into cilia.

INTRODUCTION

Primary cilia are microtubule-based organelles that convert extracellular signals into intracellular responses through the dynamic exchange of signaling molecules with the rest of the cell. While significant progress has been made toward understanding the mechanisms of entry into cilia, little is known about how signaling molecules exit cilia besides a possible requirement for the BBSome (Nachury et al., 2010; Sung and Leroux, 2013). The BBSome is an octameric complex of eight conserved Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS) proteins [BBS1/2/4/5/7/8/9/18] (Nachury et al., 2007; Loktev et al., 2008; Scheidecker et al., 2014), which are amongst 19 gene products defective in BBS, a pleiotropic disorder characterized by obesity, polydactyly, retinal dystrophy, and cystic kidneys (Fliegauf et al., 2007). We previously showed that GTP loading onto the small Arf-like GTPase ARL6/BBS3 triggers the assembly of a planar BBSome/ARL6 coat on the surface of membranes (Jin et al., 2010). The BBSome coat sorts membrane proteins into cilia through the direct recognition of ciliary targeting sequences by the BBSome (Jin et al., 2010; Seo et al., 2011). In addition, the BBSome/ARL6 coat also mediates the export of signaling proteins such as the Hedgehog signaling receptors Patched 1 and Smoothened (Zhang et al., 2011; 2012). In cilia, BBSome coats co-move with intraflagellar transport (IFT) trains, composed chiefly of IFT complexes A and B (Piperno and Mead, 1997; Cole et al., 1998; Ou et al., 2005a; Lechtreck et al., 2009). IFT trains transport axonemal precursors from base to tip (anterograde transport) and recycle proteins from tip to base (retrograde transport) (Rosenbaum and Witman, 2002; Wren et al., 2013). Despite recent progress in understanding the cellular function of the BBSome, exactly where polymerization of the BBSome coat is initiated and terminated and how these events are coordinated with IFT train dynamics remains unknown. In particular, no guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) or GTPase-activating protein (GAP) has been identified for ARL6.

Small GTPases that localize to cilia represent a class of molecules that have the potential to regulate ciliary trafficking. In particular, the Rab-like GTPase IFT27/RABL4, which forms an obligatory complex with IFT25, associates with IFT-B inside cilia (Qin et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2009; Bhogaraju et al., 2011). Similar to BBSome mutants but unlike null mutants for other IFT-B subunits in which ciliogenesis is grossly affected, Ift25−/− cells possess normal cilia that accumulate Patched 1 and Smoothened in their cilia and are thus defective in Hedgehog signaling (Keady et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2011; 2012). The recent identification of a pathogenic mutation in IFT27 in a BBS family suggests that IFT27/BBS19 might regulate BBSome function (Aldahmesh et al., 2014). Here we show that, upon disengagement from the rest of IFT-B, IFT27 directly interacts with and stabilizes the nucleotide-free form of ARL6. We further demonstrate that loss of IFT27 reduces the ciliary exit rates of BBSome, and causes ciliary accumulation of ARL6, BBSome and GPR161, a G protein coupled receptor (GPCR) that participates in Hedgehog signaling. Thus, through its control of nucleotide-empty ARL6, IFT27 links the BBSome to the IFT machinery to drive ciliary export of signaling molecules.

RESULTS

Nucleotide-dependent association of IFT27 with IFT-B

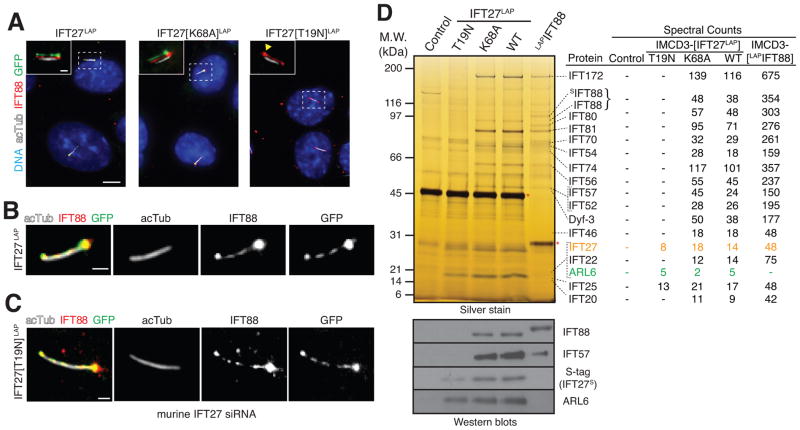

We first sought to understand how the nucleotide state of IFT27 might affect ciliary trafficking. We generated stable mouse IMCD3 kidney cell lines stably expressing human IFT27 fused to a LAP tag (localization and tandem affinity purification) consisting of an S-tag followed by a cleavage site for the HRV3C protease and GFP (Cheeseman and Desai, 2005). To “lock” IFT27 in either the GTP-bound (active) form or GDP-bound (inactive) form, we introduced point mutations into IFT27 that are predicted to either preclude GTP hydrolysis by preventing interaction with a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) [K68A], or disrupt GTP binding while allowing limited GDP binding [T19N] (Bhogaraju et al., 2011) (Figure S1A). Remarkably, while IFT27-LAP and IFT27[K68A]-LAP localized to cilia (Figure 1A) and co-localized with the IFT-B subunit IFT88 inside cilia (Figure 1B), IFT27[T19N]-LAP failed to localize to cilia, suggesting that GTP binding promotes ciliary entry of IFT27. Since IFT27[T19N]-LAP levels are only reduced 2-fold in lysates (and 5-fold in LAP eluates) compared to IFT27-LAP (Figures S1B and S1D), the absence of IFT27[T19N] from cilia cannot be solely accounted for by reduced protein levels. Surprisingly, knockdown of endogenous IFT27 in the stable cell line expressing IFT27[T19N]-LAP allowed IFT27[T19N]-LAP to enter cilia and co-localize with endogenous IFT88 (Figures 1C and S1C), suggesting that IFT27[T19N] is outcompeted by endogenous IFT27 for incorporation into IFT-B.

Figure 1. Identification of ARL6 as an interactor of IFT27.

(A–C) Murine IMCD3 cells stably expressing human IFT27, IFT27[K68A] (“GTP-locked”), or IFT27[T19N] (“GDP-locked”) tagged at the C-terminus with a LAP tag (S tag followed by a HRV3C cleavage site and GFP) were stained for IFT88 (red), acetylated tubulin (white) and DNA (blue). IFT27LAP variants were visualized through the intrinsic fluorescence of GFP. (A) Inset shows the individual fluorescence channels vertically offset from one another by 3 pixels. A yellow arrowhead points to the base of a cilium in the GFP channel of IFT27[T19N]LAP cells. Scale bar: 5 μm (main panels), 1 μm (insets). (B–C) Magnified views of cilia from IFT27LAP cells (B) or IFT27[T19N]LAP cells (C). Scale bar: 1 μm. In (C) endogenous mouse IFT27 was knocked down leaving human IFT27[T19N]LAP as the major IFT27 protein in those cells. See Figure S1C for control siRNA experiment.

(D) Lysates were subjected to anti-GFP antibody capture and HRV3C (control, IFT27LAP) or TEV (LAPIFT88) cleavage elution before SDS-PAGE and silver staining (top) or immunoblotting (bottom). Asterisks indicate proteases used for cleavage elution. In parallel, the eluates were analyzed by mass spectrometry and the spectral counts for each IFT-B subunit are shown in the table on the right. Spectral counts from LAPIFT88 are the aggregate of three separate mass spectrometry experiments. Immunoblotting for IFT-B subunits (IFT88, IFT57) and for ARL6 was conducted to confirm the mass spectrometry results. Immunoblotting for the S-tag that remains on IFT27LAP after HRV3C cleavage shows the amounts of all IFT27 variants recovered in the LAP eluates.

See also Figure S1.

To identify effectors and regulators of IFT27, we performed GFP-immunoprecipitation and HRV3C cleavage with all IFT27-LAP cell lines. Consistent with the localization pattern of IFT27[K68A] and IFT27, all IFT-B subunits, including the suspected subunit CLUAP1/DYF-3/qilin (Ou et al., 2005b), co-purified with IFT27[K68A] and with IFT27 (Figure 1D). Recovery of the IFT-B complex in association with IFT27 was confirmed by immunoblotting for the subunits IFT88 and IFT57, and LAP purifications of IFT88 yielded the same complement of IFT-B subunits. Meanwhile, the obligatory partner IFT25 was the only IFT-B subunit recovered in purifications of IFT27[T19N]-LAP. Since Chlamydomonas reinhardtii IFT27/25 complex exists in a free form with only a minor fraction associated with IFT-B (Wang et al., 2009), we conclude that GTP-bound IFT27 interacts strongly with the rest of IFT-B while IFT27-GDP interacts very weakly with IFT-B and is readily outcompeted by IFT27-GTP.

IFT27 but not IFT-B interacts with ARL6

Most unexpectedly, mass spectrometry robustly identified ARL6 in purifications of all IFT27 variants, a result we confirmed by immunoblotting (Figures 1D and S1E). In contrast to other IFT-B subunits, prior studies in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii have indicated that most of the IFT27/25 complex exists in a free form with only a minor fraction associated with IFT-B (Wang et al., 2009). The existence of distinct cellular pools of IFT25/IFT27 posed the question of which one associated with ARL6. Given that IFT27[T19N] recovered similar amounts of ARL6 as IFT27 and IFT27[K68A] – even though IFT27[T19N] is expressed (and recovered in LAP eluates) at lower levels than IFT27[K68A] and IFT27 (Figures 1D, S1B and S1C) – it appeared that stable incorporation of IFT27 into IFT-B was not required for interaction with ARL6. Furthermore, while every IFT subunit was identified in LAP-IFT88 purifications by at least three times as many spectral counts as in the IFT27-LAP purification, not a single peptide for ARL6 was identified in the LAP-IFT88 eluates (Figure 1D). Similarly, even when twice as much of the LAP-IFT88 eluate was loaded compared to the IFT27-LAP eluate, no ARL6 was detected in LAP-IFT88 eluates by immunoblotting (Figure 2A). Together, these results indicate that ARL6 does not recognize IFT27 within the IFT-B complex. Instead, ARL6 must interact with a form of IFT25/IFT27 that is either free or in a complex distinct from IFT-B.

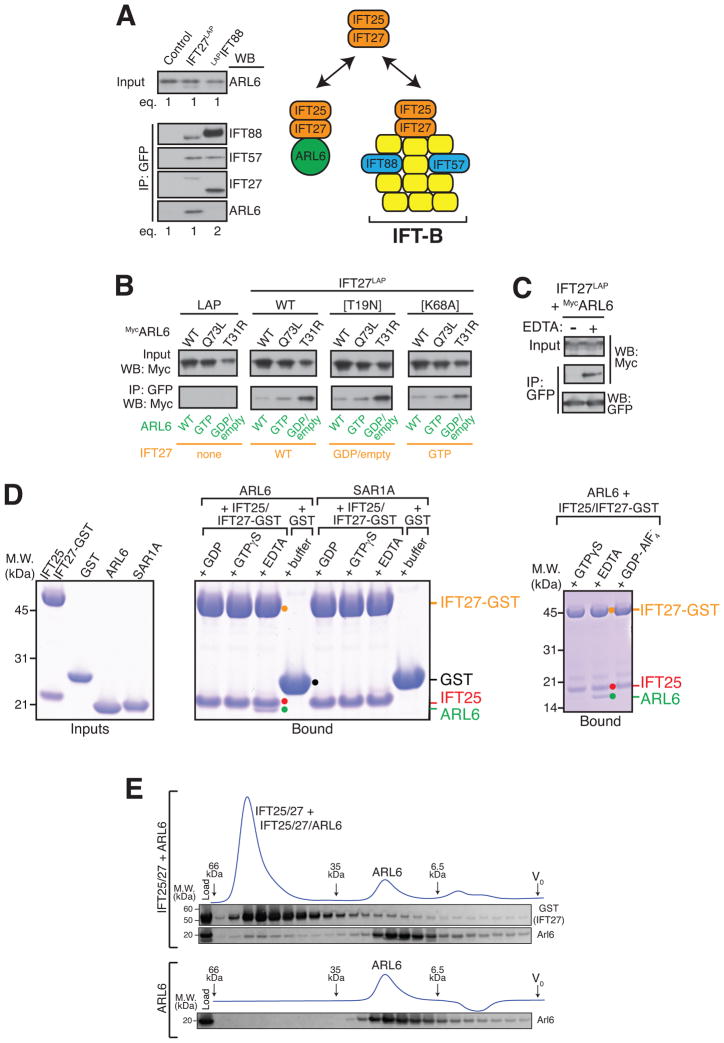

Figure 2. IFT27 directly interacts with nucleotide-empty ARL6.

(A) LAP eluates from IFT27LAP and LAPIFT88 were analyzed by immunoblotting for IFT-B subunits (IFT88, IFT57), IFT27 and ARL6. Twice as much of the LAPIFT88 eluate was loaded compared to the IFT27LAP eluate. Note that the IFT27 antibody preferentially recognizes murine IFT27 over human IFT27, accounting for the lower signal intensity of IFT27S-tag in the IFT27LAP lane compared to that of murine IFT27 in the LAPIFT88 lane.

(B) Co-transfections/co-immunoprecipitations were performed with all combinations of “GTP-locked” or “GDP-locked” variants of ARL6 and IFT27. IFT25 was co-transfected with IFT27LAP to ensure IFT27 stability.

(C) IFT25/IFT27LAP-decorated beads were used to capture overexpressed MycARL6 out of HEK cell lysate in the presence or absence of EDTA.

(D) The IFT25/IFT27-GST complex, GST, ARL6 and SAR1A were expressed in bacteria and purified to near-homogeneity before SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining (left panel). IFT25/IFT27-GST was mixed with ARL6 or SAR1A in the presence of various nucleotides and complexes were recovered on Glutathione Sepharose beads before LDS elution, SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining (middle panel). In a similar experiment, IFT25/IFT27-GST was mixed with ARL6 in the presence of GTPγS, EDTA or GDP/AlF4− (right panel).

(E) ARL6, either alone or mixed with the IFT25/IFT27 complex and EDTA was resolved by size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200). Size markers: 66.9 kDa (Thyroglobulin), 35.0 kDa (β-lactoglobulin) and 6.5 kDa (Aprotinin).

See also Figure S2.

IFT27 recognizes the nucleotide-free form of ARL6

Since ARL6 and IFT27 are both GTPases, we asked whether their mutual interaction was dependent on their respective nucleotide states. We first tested interactions by co-transfection/co-immunoprecipitation with all combinations of “GTP-locked” or “GDP-locked” variants of ARL6 and IFT27. While altering the nucleotide state of IFT27 had little effect on the interaction, the “GDP-locked” variant of ARL6 (T31R) interacted more strongly with IFT27 than the wildtype or “GTP-locked” forms of ARL6 (Figures 2B and S2A). It should be noted that the so-called “GDP-locked” P-loop mutation significantly lowers the affinity of small GTPases for GDP and even more dramatically for GTP. Thus, the T31R mutant of ARL6 is expected to mimic the nucleotide-empty and the GDP-bound forms of ARL6. To specifically test if nucleotide-empty ARL6 interacts with IFT27, we separately expressed the two proteins in HEK cells. IFT27 was captured onto beads and used as bait for ARL6.

The assays were conducted in the absence or presence of EDTA, which renders small GTPases nucleotide-empty by chelating the Mg2+ ion needed for nucleotide binding (Tucker et al., 1986). Remarkably, IFT27 only interacted with ARL6 in the presence of EDTA (Figure 2C). While small GTPases typically bind nucleotides with picomolar affinities, IFT27 only binds nucleotides with micromolar affinity (Bhogaraju et al., 2011) and a substantial proportion of IFT27 will be nucleotide-empty under our experimental conditions. Thus, together with the co-immunoprecipitation results, we interpret the EDTA dependency of the IFT27-ARL6 interaction as indicative that nucleotide removal on ARL6 promotes interaction with IFT27.

IFT27 directly and specifically bind nucleotide-free ARL6

Four different types of small GTPase regulators and binders have been defined (Cherfils and Zeghouf, 2013; Vetter, 2001). GDP dissociation inhibitors (GDIs) chaperone prenylated GTPases away from membranes when GDP-bound, GEFs catalyze the exchange of GDP for GTP to carry out activation, effectors read the GTP state to convey downstream effects and GAPs increase the rate of GTP hydrolysis to terminate signals.

In the nucleotide exchange reaction, the GEF is tightly bound to the nucleotide-free GTPase in the transition state and associates very weakly with the substrate (GDP-bound GTPase) and the product (GTP-bound GTPase) (Goody and Hofmann-Goody, 2002). While the transition state complex can be stabilized in vitro by removal of guanine nucleotides, high GTP concentrations in the cytoplasm lead to the rapid release of the GTP-bound GTPase from the GEF-GTPase complex. In the GEF hypothesis, IFT27 and ARL6 interact most strongly when ARL6 is nucleotide-free. In the GDI hypothesis, IFT27 and ARL6 interact most strongly when ARL6 is GDP-bound. Finally, GAPs recognize GTP-bound GTPases and the transition state of the GAP-catalyzed hydrolysis reaction has a water molecule positioned for nucleophilic attack on the β-γ phosphate bond, a state that can be mimicked by GDP-AlF4−.

To gain insights into the type of ARL6 regulator encoded by IFT27, we assessed how the nucleotide state of ARL6 affects binding to IFT27 using purified components. ARL6, its close relative SAR1A, and IFT27-GST together with IFT25 were expressed in bacteria (Figure 2D, left panel). IFT25/IFT27-GST was mixed with recombinant ARL6 or SAR1A loaded with various combinations of nucleotides and complexes were recovered on Glutathione beads. Similar to IFT27 and ARL6 expressed in mammalian cells, recombinant IFT27 interacted with ARL6 only in the presence of EDTA but not in the presence of GDP or GTP (Figure 2D, middle panel). Meanwhile, no interaction between IFT27 and SAR1A was observed in the presence of EDTA. Although nucleotide-free GTPases are prone to aggregation and possibly non-specific interactions, nucleotide-empty ARL6 did not interact with GST (Figure 2D, middle panel) or any of five unrelated proteins (Figure S2B). Furthermore, ARL6 co-migrated with IFT25/IFT27 on size exclusion chromatography in the presence of EDTA (Figure 2E), indicating formation of a stable complex between IFT25/IFT27 and nucleotide-free ARL6. Finally, to test the possibility that IFT27 might act as a GTPase activating protein (GAP) for ARL6, we preformed ARL6-GDP-AlF4−, which failed to interact with IFT27 (Figure 2D, right panel). Because IFT27 does not detectably associate with ARL6-GTP, ARL6-GDP-AlF4− or ARL6-GDP but strongly binds nucleotide-empty ARL6, our results strongly disfavor the effector, GAP and GDI hypotheses and leave the GEF function as the most likely hypothesis.

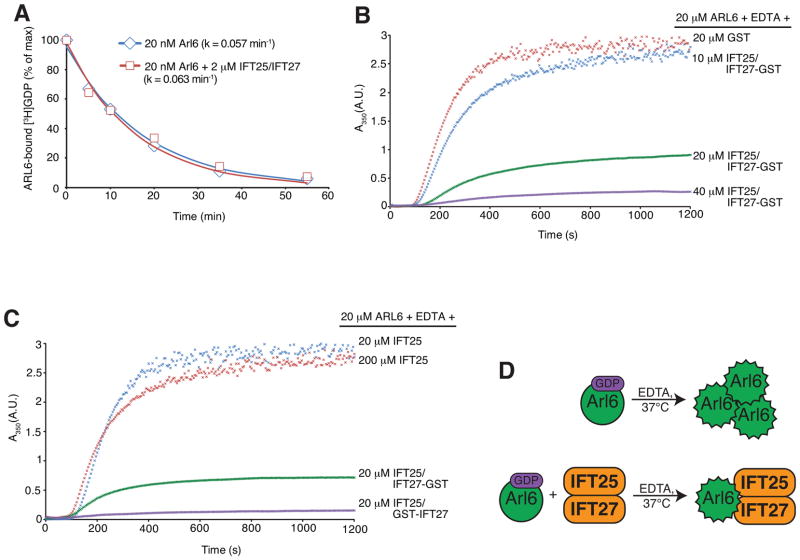

IFT27 chaperones the nucleotide-free form of ARL6 against aggregation

Despite repeated attempts to directly test the ARL6GEF activity of IFT27 in vitro, the greatest increase in GDP release rate brought about by addition of IFT27 was only 2-fold over control (Figure 3A; see Figure S3A for a summary of all conditions tested so far). This suggests that additional factors (e.g. proteins, membranes, post-translational modifications, etc.) besides IFT27 are required to reconstitute the full ARL6GEF activity. While the identity of these factors is presently unknown, we attempted to obtain further circumstantial evidence that IFT27 is part of an ARL6GEF. Similar to the behavior of other nucleotide-free GTPases (Cherfils and Zeghouf, 2013), ARL6 tends to aggregate upon EDTA addition, which can be monitored by light diffraction at 350nm. Remarkably, ARL6 aggregation was greatly reduced when ARL6 was co-incubated with stoichiometric amounts of the IFT25/IFT27 complex before addition of EDTA (Figure 3B and C). In this turbidity assay, the degree of precipitation rescue was dependent on the concentration of IFT25/IFT27 added (Figure 3B), whereas GST alone or IFT25 alone did not result in stabilization of nucleotide-free ARL6 (Figures 3B and C, S3B). Since the conformation of IFT25 is not affected by IFT27 binding (Figure S3C), it is most likely IFT27 itself that recognizes and stabilizes the nucleotide-free form of ARL6. Alternatively, a complex interface from IFT25 and IFT27 may recognize ARL6. Since GEFs stabilize the nucleotide-empty GTPases against aggregation, those data are consistent with IFT27 being part of the ARL6GEF (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. IFT27 stabilizes the nucleotide-empty form of ARL6.

(A) Time course of [3H]-GDP release from ARL6 in the presence or absence of IFT25/IFT27. Data points were fit to a single exponential decay equation and plotted. See Figure S3A for a summary of all conditions tested.

(B–D) EDTA-induced ARL6 precipitation at 37°C was followed by light diffraction at 350 nm.

(B) Rescue of ARL6 precipitation by stoichiometric concentrations of IFT25/ IFT27-GST.

(C) Effect of different IFT25/IFT27 variants on the rescue of EDTA-induced ARL6 precipitation. Judging by endpoint absorbance values, IFT25/GST-IFT27 (N-terminal GST tag) was ~6 times more efficient than IFT25/IFT27-GST (C-terminal GST tag) in rescuing EDTA-induced Arl6 precipitation. Addition of IFT25 (even at 10-fold molar excess over ARL6) does not rescue precipitation of nucleotide empty ARL6.

(D) Model for IFT27 stabilization of nucleotide-empty ARL6.

See also Figure S3.

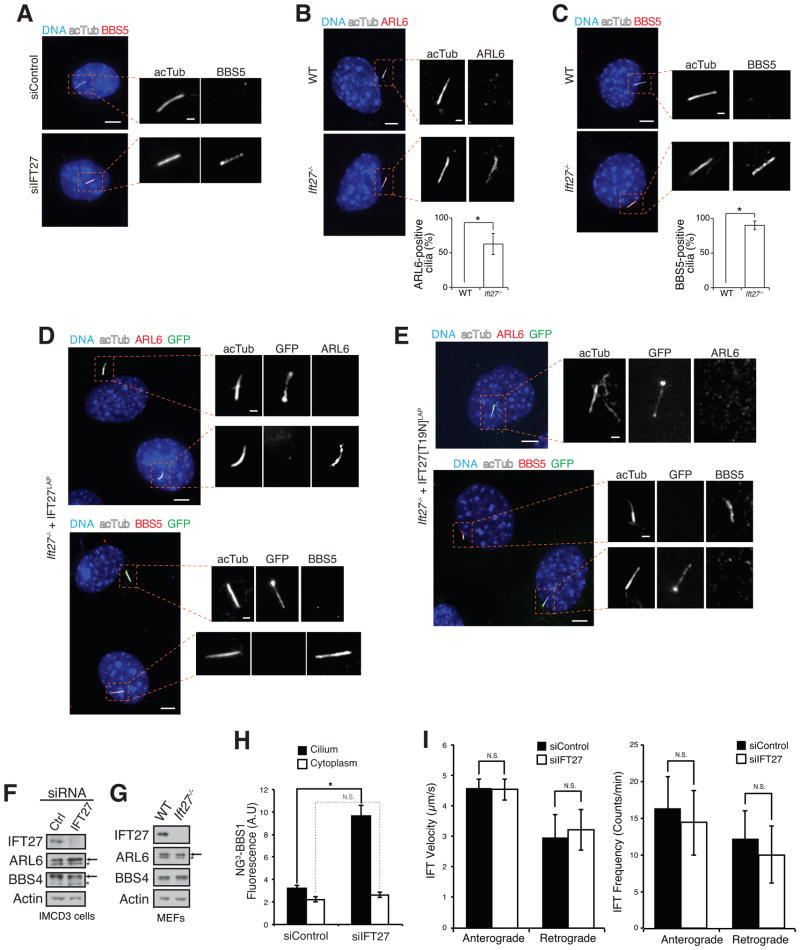

Loss of IFT27 causes hyper-accumulation of ARL6 and BBSome in cilia

Given our prior model that ARL6 activation drives BBSome coat formation and entry into cilia (Jin et al., 2010), loss of the cytoplasmic ARL6GEF is predicted to reduce BBSome coat formation and ciliary entry of ARL6 and the BBSome. Unexpectedly, while ciliary BBSome levels in IMCD3 cells are normally below the detection limit of our immunological reagents, IFT27 knockdown led to the distinct detection of BBSome in cilia (Figure 4A). Similarly Ift27−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) accumulated ARL6 (Figure 4B) and BBSome (Figure 4C) inside cilia while no BBSome or ARL6 signal could be detected in cilia of wild-type MEFs. The hyper-accumulation of ARL6 and BBSome in cilia could be rescued by transient expression of IFT27 WT, [K68A] or [T19N] (Figures 4D and E, and S4A). Since IFT27[T19N] exhibits reduced affinity for IFT-B (Figure 1D) it appears that strong binding of IFT27 to IFT-B is not required to properly regulate ARL6 ciliary levels. Meanwhile, knockout of ARL6 did not affect ciliary localization of IFT27 (Figure S4B) thus suggesting that IFT27 controls ARL6 and not vice versa. Immunoblotting of lysate from IFT27-depleted IMCD3 cells or Ift27−/− MEFs revealed no change in overall ARL6 or BBSome levels (Figures 4F and G, and S4C), indicating that the ciliary hyper-accumulation phenotypes did not result from global increases in ARL6 or BBSome levels. In agreement with our immunoblots, quantitation of BBSome signal from live IMCD3 cells stably expressing BBS1 fused to three tandem repeats of the superbright fluorescent protein NeonGreen (Shaner et al., 2013) (NG3-BBS1, Figure S4D) revealed similar amounts of BBSome in the cytoplasm of control siRNA- and IFT27 siRNA-treated cells (Figure 4H). Concordant with our fixed cell imaging, the amounts of NG3-BBS1 in cilia of live IFT27-depleted cells were about 3 times greater than those in control cells (Figure 4H). To test whether IFT27 depletion indirectly results in BBSome hyper-accumulation through alterations in ciliary IFT dynamics, we measured the velocity and frequency of IFT trains, and found no significant difference for either parameter between IFT27-depleted and control cells (Figure 4I). These results strongly suggest that IFT27 negatively regulates ciliary localization of ARL6 and the BBSome but that ARL6 does not influence IFT27 localization. These results are also congruent with our biochemical data showing that the nucleotide state of IFT27 does not influence the interaction with ARL6.

Figure 4. Loss of IFT27 causes hyperaccumulation of ARL6 and BBSome in cilia.

(A) IMCD3 cells were treated with control siRNA or IFT27 siRNA and immunostained for the BBSome subunit BBS5.

(B, C) WT and Ift27−/− MEFs were immunostained for ARL6 (B) or BBS5 (C). At least 100 cilia per experiment were counted, and the percentages of ARL6- and BBS5-positive cilia were plotted. Error bars represent standard deviations (SDs) between three independent experiments. The asterisks denote that a significant difference was found by unpaired t-test between WT and Ift27−/− MEFs for ARL6 accumulation (p = 0.0176) and BBS5 accumulation (p = 0.00143).

(D) IFT27LAP and (E) IFT27[T19N]LAP were transfected into Ift27−/− MEFs to rescue the ciliary accumulation of ARL6 and BBSome. (See also Figure S3C for rescue by transfection of IFT27[K68A]LAP). Scale bars: 5 μm (cell panels), 1 μm (cilia panels).

(F–G) Whole cell lysates from control siRNA- and IFT27 siRNA-treated IMCD3 cells (F) or WT and Ift27−/− MEFs (G) were immunoblotted for IFT27, ARL6, BBSome and Actin.

(H) Ciliary and cytoplasmic NG3-BBS1 fluorescent intensities were measured in control siRNA- and IFT27 siRNA-treated IMCD3-[NG3-BBS1] cells. Data were collected from 17 to 18 cells for each condition in five independent experiments. Error bars represent +/− SD. N.S.: p>0.05; *: p<0.05.

(I) Bar graphs representing the velocity (left) and frequency (right) of NG3-IFT88 fluorescent foci movement in cilia from control siRNA- and IFT27 siRNA-treated IMCD3-[NG3-IFT88] cells. More than 200 tracks of IFT88 foci were analyzed for each treatment. N.S.: p>0.05.

See also Figure S4.

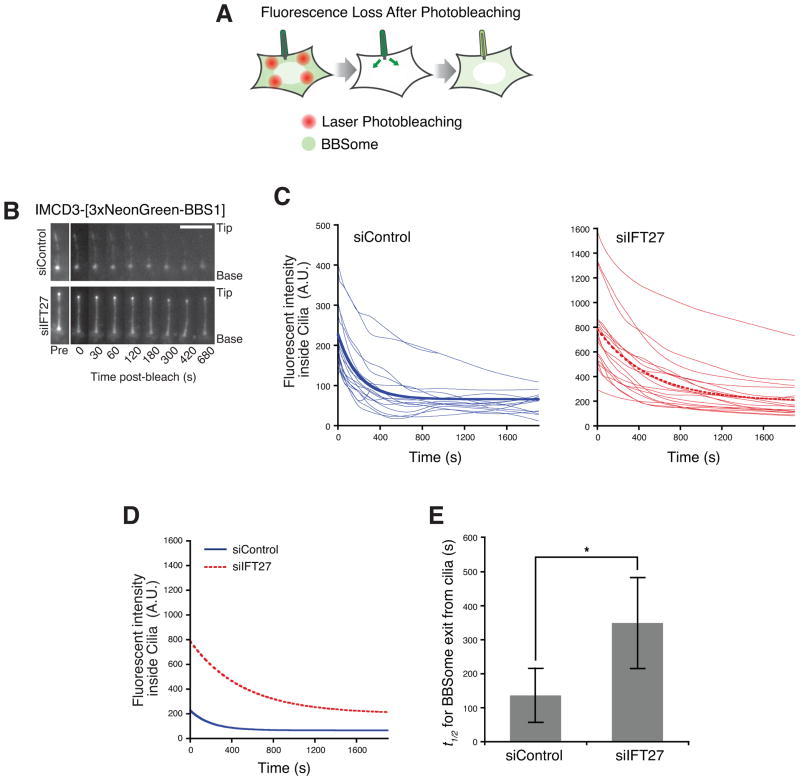

IFT27 promotes ciliary exit of the BBSome

Unregulated exchanges of molecules between cilium and cytoplasm are prevented by a diffusion barrier for both soluble and membrane proteins at the ciliary base, requiring specialized cellular machineries to facilitate transport into and out of the cilium (Nachury et al., 2010; Sung and Leroux, 2013). In this context, the hyper-accumulation of ARL6 and BBSome in IFT27-deficient cilia could result from either increased ciliary entry of ARL6 and BBSome, or impaired ciliary exit of ARL6 and BBSome. While the latter hypothesis is consistent with the model that IFT27 acts as an ARL6GEF inside cilia, the former hypothesis would instead suggest that IFT27 prevents nucleotide exchange on ARL6 in the cytoplasm, possibly by competing for nucleotide-empty ARL6 with the cytoplasmic ARL6GEF.

To distinguish between these two possibilities, we directly assessed the ciliary entry and exit rates of the BBSome by leveraging the newly developed IMCD3-[NG3-BBS1] cell line and photobleaching methods. The brightness of NG3-BBS1 enabled the robust imaging of ciliary BBSome dynamics in live mammalian cells. To measure ciliary exit of BBSome, we performed a Fluorescence Loss after Photobleaching (FLAP) assay (Figure 5A). Unlike the repeated photobleaching in conventional Fluorescence Loss In Photobleaching (FLIP) assays, in FLAP the cytoplasm is photobleached only during a 30 s time interval between the first and second time point of the movie (Figure 5B, Movie S1). Typically, 80% of the cytoplasmic NG3-BBS1 fluorescence was depleted in FLAP assays. Given that the volume of a cilium (<0.5 fL) represents less than 0.05% of the total volume of the cell (Nachury, 2014), the contribution of reentry of fluorescent BBSome that exited cilia is negligible. Therefore, the fluorescent signal decay in cilia is a direct measure of the exit rate of BBSome (Figure 5B and C). In IFT27 siRNA-treated cells, the half-life of ciliary BBSome is t1/2 = 349 s, which is significantly longer than in the control cells where t1/2 = 136 s (Figure 5D and E). Thus, in IFT27 siRNA-treated cells, a given amount of BBSome would take at least twice as much time to exit from cilia, as compared to control siRNA-treated cells. These data strongly suggest that IFT27 promotes the export of BBSome out of cilia and place the likely site of IFT27 activity within cilia.

Figure 5. IFT27 is required for rapid exit of BBSome from cilia.

(A) Schematic of Fluorescence Loss After Photobleaching (FLAP) assay. NG3-BBS1 was photobleached in the cytoplasm by intense illuminations with a 488 nm laser. The bleached areas of the cell are distant from the cilium to ensure that ciliary NG3-BBS1 is not bleached by the illuminations. The subsequent loss of NG3-BBS1 fluorescence from cilia was monitored by live imaging.

(B) Time series montage representing the dynamic loss of ciliary NG3-BBS1 fluorescence in FLAP assay. Ciliary tip and base are marked. Scale bar, 5 μm.

(C) Decay of ciliary NG3-BBS1 fluorescence signal in FLAP assays for control siRNA- and IFT27 siRNA-treated cells. The fluorescence decay was measured for individual cilia, and plotted as a smoothed line for siControl (left, blue lines) and siIFT27 (right, red lines) treated cells. Photobleaching was negligible (<2%, data not shown). Each experiment was individually fit to a single exponential, and a simulation describing the average of these fits is shown as a bold line. Data were collected from five independent experiments (number of cilia analyzed n=17 for siControl and n=18 for siIFT27).

(D and E) The exit of BBSome from cilia is slower in the absence of IFT27. (D) Replotting of the simulations describing the average fits from panel (B) for siControl (blue solid line) and siIFT27 (red dotted line) treated cells. (E) Average half-lives (t1/2) for ciliary exit of NG3-BBSome. For siControl, t1/2 =136s +/− 20s, and for siIFT27, t1/2 =349s +/− 20s. The asterisk indicates a highly significant difference in exit rates (unpaired t-test, p < 5 × 10−6). Error bars represent +/− 1 SD.

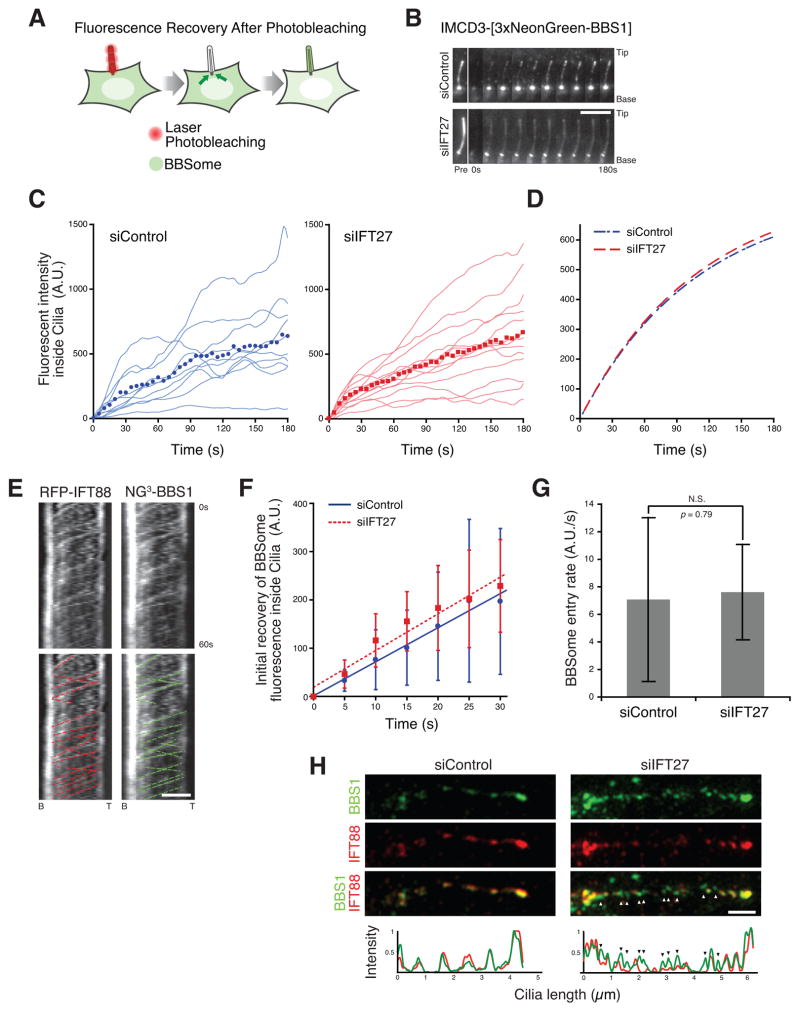

IFT27 does not affect ciliary entry of the BBSome

Defective ciliary export need not be the sole factor contributing to the aberrant ciliary accumulation of BBSome in IFT27-deficient cells. To determine if the ciliary entry rate of BBSome was also affected in IFT27-deficient cells, we performed Fluorescence Recovery After photobleaching (FRAP) analysis of ciliary NG3-BBS1 (Figure 6A). After photobleaching ciliary NG3-BBS1, the subsequent signal recovery rate in cilia was monitored to obtain the ciliary entry rate of BBSome (Figure 6B, Movie S2). The averaged curves of fluorescence recovery in control and IFT27-deficient cilia appeared nearly identical (Figure 6C–D).

Figure 6. IFT27 does not affect the entry of BBSome into cilia.

(A) Schematic of Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) assay. Ciliary NG3-BBS1 was photobleached by intense illumination with a 488 nm laser. The subsequent ciliary NG3-BBS1 fluorescence recovery from cytoplasmic pools was monitored by live imaging.

(B) Time series montage representing the dynamic recovery of ciliary NG3-BBS1 fluorescence in FRAP assay. Ciliary tip and base are marked. Scale bar, 5 μm.

(C–D) Recovery of NG3-BBS1 ciliary fluorescence in FRAP assays for control siRNA- and IFT27 siRNA-treated cells.. (C) The fluorescent intensity was measured for each individual cilia, and plotted as a smoothed line for siControl (left, blue lines) and siIFT27 (right, red lines) treated cells. The averaged fluorescence values at each time points are shown in the plot (blue dots for siControl and red dots for siIFT27). Photobleaching was measured and corrected (see Experimental Procedures). (D) Single exponential fit to the averaged fluorescence recovery for siControl (blue dashed line) or siIFT27 (red dashed line).

(E) Simultaneous imaging of tagRFP.T-IFT88 (left) and NG3-BBS1 (right) movements in cilia of IMCD3 cells. The fluorescent foci tracks for IFT88 (red) and NG3-BBS1 (green) are indicated in the bottom panels. Scale bar, 2 μm.

(F and G) Initial velocities for BBSome entry into cilia of Control siRNA and IFT27 siRNA-treated cells. (E) Time points from the first 30 second of the siControl and siIFT27 experiments in (C) were averaged and plotted. (F) The slopes from the curves in (E), corresponding to the initial velocities of BBSome entry into cilia, were plotted in a bar graph. There was no significant difference for the velocities of BBSome entry (unpaired t-test, p = 0.79). For panels (E) and (F), error bars represent +/− 1 SD.

(H) Ciliated IMCD3 cells expressing NG3-BBS1 were immunostained for IFT88 and imaged by Structured Illumination Microscopy (SIM) on an OMX Blaze (API). Colocalization between IFT88 (red) and NG3-BBS1 (green) is displayed on a line profile (bottom). While each foci of BBS1 precisely co-localizes with an IFT88 spot in cilia of Control siRNA-treated cells, the majority of BBS1 foci are free of IFT88 (arrowheads) in cilia of IFT27 siRNA-treated cells (bottom right). Scale bar, 1 μm.

See also Figure S5.

The BBSome has been previously reported to colocalize and co-move with IFT trains within cilia in Chlamydomonas (Lechtreck et al., 2009) and the BBSome is transported within nematode cilia at IFT rates (Ou et al., 2005a). Similarly, we saw overlapping ciliary tracks of RFP-IFT88 and NG3-BBS1, indicative of BBSome co-movement with IFT (Figure 6E and Figure S5A). The anterograde and retrograde velocities of IFT88 foci are approximately 0.5 μm/s (Ye et al., 2013), indicating that the minimum time required for a newly entered BBSome/IFT train to travel along the length of a 5 μm cilia and return to the base would be 20 s, without taking into account the time required for IFT complex remodeling at the ciliary tip. To minimize the contribution of ciliary exit of BBSome on the signal recovery in our FRAP assays, we plotted the initial recovery of BBSome fluorescence for the first 30 s (Figure 6F) and the entry rate of BBSome (Figure 6G) was calculated based on the linear fit of the initial recovery. Consistent with our initial observation, knockdown of IFT27 does not significantly affect the rate of BBSome entry into cilia.

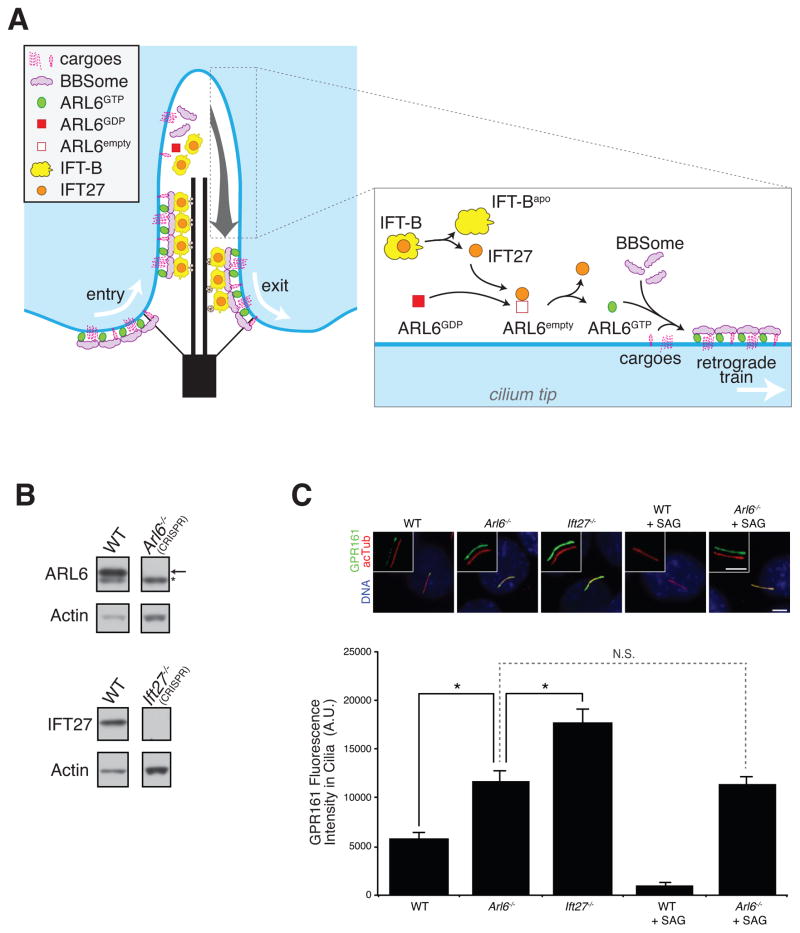

While the abundance of BBSome was nearly three times greater in the cilia of IFT27-depleted cells compared to control cells (Figure 4H), the amount of ciliary IFT-B (assessed by IFT88 staining) appeared unchanged (Figure 1C and S1C). To determine if the BBSome that hyperaccumulates in IFT27-deficient cilia was still associated with IFT trains, we imaged IFT88 and NG3-BBS1 by Structured Illumination Microscopy (SIM). The axial resolution of less than 100 nm provided by SIM allowed us to precisely distinguish between IFT-associated BBSome foci and IFT-free BBSome foci. In control cilia, IFT88 and NG3-BBS1 foci colocalized and were found in a series of puncta along the cilium length (Figure 6H and S5B), whereas in IFT27-deficient cilia, the majority of BBSome puncta did not overlap with IFT88 staining (Figure 6H and S5B). In conclusion, these data indicate that the ciliary accumulation of ARL6 and BBSome in IFT27-deficient cells results from defective ciliary export rather than increased ciliary entry. Together with our biochemical data demonstrating that IFT27 recognizes and stabilizes the nucleotide-free form of ARL6, the live-imaging data support a model where IFT27 regulates ARL6 within cilia to drive the export of BBSome and associated cargoes from cilia (Figure 7A).

Figure 7. IFT27 and ARL6 are required for ciliary exit of GPR161.

(A) A model for the turnaround point. GTP hydrolysis on ARL6 leads to disassembly of BBSome coats at the tip. IFT-B particles release IFT25/IFT27 by an unknown mechanism upon IFT train disassembly at the tip. Free IFT27 then participates in GDP to GTP exchange on ARL6 and assembly of a BBSome coat laden with cargoes and attached to a retrograde IFT train ensues.

(B) Genome engineering of IMCD3 WT, Arl6−/− or Ift27−/− cells. Knockout of the respective gene products are demonstrated by immunoblotting for ARL6 and IFT27. As a loading control, lysates were immunoblotted for Actin.

(C) IMCD3 WT, Arl6−/− or Ift27−/− cells treated with SAG or vehicle or untreated were stained for GPR161 (green), acetylated tubulin (red) and DNA (blue). Scale bar, 4 μm. Background-subtracted integrated ciliary fluorescence intensities were measured from 42 to 76 cilia in 5 to 6 microscopic fields for each condition and plotted in the bar chart (bottom). *: p < 0.05, N.S.: p > 0.05, Error bars represent +/− SEM.

Ciliary removal of the GPCR GPR161 requires IFT27 and ARL6

Since the BBSome participates in the trafficking of several GPCRs (Berbari et al., 2008; Domire et al., 2010; Jin et al., 2010) and Hedgehog intermediates (Zhang et al., 2011; 2012), we imaged the behavior of the putative BBSome cargo and Hedgehog signaling intermediate GPR161 as a final test of our model. GPR161 undergoes regulated exit from cilia upon activation of the Hedgehog pathway by either natural ligand or the Smoothened agonist SAG (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2013). However, in Arl6−/− IMCD3 cells generated by genome engineering (Figure 7B), addition of SAG failed to reduce the ciliary levels of GPR161 (Figure 7C). Even in the absence of SAG, the levels of GPR161 inside cilia were elevated in Arl6−/− cells when compared to WT cells, consistent with a low level constitutive activation of the Hh pathway in our culture system. These results indicate that GPR161 relies on the ARL6/BBSome coat for regulated exit from cilia. Meanwhile, Ift27−/− cells displayed constitutively levels of ciliary GPR161 higher than WT and Arl6−/− cells, further supporting our model that IFT27 promotes ciliary exit of ARL6, BBSome and associated cargo. The greater penetrance of the GPR161 ciliary accumulation phenotype in Ift27−/− cells suggests that the BBSome may function in both ciliary entry and exit of GPR161: without ARL6, both entry and exit are reduced (but exit more than entry) while IFT27 only regulates ARL6 within cilia and hence only affects the exit of GPR161 out of cilia.

DISCUSSION

The functional importance of the IFT27-ARL6 interaction

Although the BBSome has been shown to undergo intraflagellar movement at the same rates as IFT particles in nematodes, Chlamydomonas and human cells (Ou et al., 2005a; Nachury et al., 2007; Lechtreck et al., 2009), the IFT27-ARL6 interaction we describe here represents, to our knowledge, the first biochemical link established between the BBSome and the IFT complexes. Furthermore, our discovery that IFT27 specifically interacts with and stabilizes the nucleotide-free form of ARL6 suggests a regulatory role for IFT27 on ARL6. Based on our biochemical and cell biological results, the most parsimonious model views IFT27 as part of a GEF for ARL6, which triggers the formation of BBSome coats inside cilia and the trafficking of BBSome and associated cargoes out of cilia. Despite repeated attempts, we have thus far failed to detect robust ARL6GEF activity in IFT25/IFT27 preparations (Figure 3A; see Figure S3A for a summary of all conditions tested so far). We consider three possibilities: first, additional protein factors may be required to reconstitute the full ARL6GEF activity in vitro (although we did not find any factor associated with IFT27[T19N] besides ARL6 and IFT25); second, detection of ARL6GEF activity may necessitate specific experimental conditions such as membrane surfaces; third, the ARL6GEF activity may be autoinhibited within the IFT25/IFT27 complex. This last hypothesis is reminiscent of the potent autoinhibition found in cytohesin family ARFGEFs (DiNitto et al., 2007). Given that the nucleotide-empty chaperone assays suggest that it is IFT27 and not IFT25 that recognizes ARL6, it is conceivable that IFT25 inhibits the ARL6GEF activity of IFT27. Finally, we note that these three hypotheses are not mutually exclusive. In the cytohesin family, autoinhibition of ARFGEF activity is relieved upon binding to membranes (Donaldson and Jackson, 2011).

Another type of GTPase regulator is exemplified by MSS4/DSS4. While MSS4/DSS4 was initially defined as a GEF for exocytic Rabs, the GEF activity of MSS4/DSS4 towards those Rabs was later found to be rather slow and MSS4/DSS4 was instead proposed to represent a chaperone for nucleotide-empty exocytic Rabs (Nuoffer et al., 1997). Yet, rigorous enzymological analyses demonstrate that MSS4/DSS4 does accelerate nucleotide exchange on exocytic Rabs to an extent similar to other RabGEFs (Itzen et al., 2006), and in vivo studies have provided further support for the Rab3GEF activity of MSS4/DSS4 (Coppola et al., 2002). Thus MSS4/DSS4 “nucleotide-empty chaperones” likely constitute a subclass of GEFs rather than a distinct biochemical activity. Finally, the idea that IFT27 functions to chaperone ARL6 against aggregation in the cell suggests that ARL6 will become unstable in the absence of IFT27, a prediction not supported by our experimental data (Figure 4G).

Where and how does IFT27 initiate ciliary export of ARL6 and the BBSome?

If IFT27 activates ARL6 within the cilium, where and how does this interaction take place? Since remodeling IFT trains are remodeled at the distal tip (Iomini et al., 2001; Pedersen et al., 2005; 2006; Wei et al., 2012), we propose that this remodeling transiently releases IFT25/IFT27 from IFT-B, allowing IFT27 and ARL6 to interact at the distal tip of cilia. In our model (Figure 7A), remodeling of a BBSome/IFT train is initiated by hydrolysis of GTP on ARL6. The BBSome/ARL6-GDP coat is rapidly disassembled to release BBSome and ARL6-GDP from the ciliary membrane at the tip. Once a BBSome coat and its associated IFT train are disassembled, IFT-B free IFT27 (together with other factors) locally catalyzes the interconversion of ARL6-GDP into ARL6-GTP. Mirroring our proposed model for BBSome coat formation at the base of cilia (Jin et al., 2010), ARL6-GTP recruits the BBSome to membranes at the tip where membranous cargoes are captured. Since excess BBSome is not associated with IFT trains in the absence of IFT27 (Figure 6H and S5B), it is likely that BBSome coat assembly at the tip is a prerequisite for BBSome association with IFT trains and that the tip-assembled BBSome/IFT train is destined for retrograde transport and cargo removal from cilia.

In contrast to the observed association of the BBSome with only a subset of IFT trains in Chlamydomonas (Lechtreck et al., 2009), our super-resolution imaging of fixed samples and live imaging of IFT and BBSome co-movement strongly suggests that all IFT trains are associated with BBSome in IMCD3 cells. While species dissimilarity may account for this difference, it is also conceivable that the use of a much brighter fluorescent protein fusion with BBS1 enabled us to detect very low levels of BBSome associated with IFT trains.

How does IFT27 cycle on and off the IFT-B complex?

Given millimolar GTP concentrations in the cell (Woodland and Pestell, 1972) and micromolar affinity of IFT25/IFT27 for guanine nucleotides (Bhogaraju et al., 2011), IFT27 is likely bound to nucleotides within the cell suggesting that the in vivo activity of IFT27 might be regulated by its nucleotide state. Our data suggest that hydrolysis of GTP on IFT27 reduces the affinity of IFT25/IFT27 for the rest of the IFT-B complex, leading to dynamic release of IFT25/IFT27-GDP from IFT-B at the tip (Figure 1). IFT25/IFT27-GDP may then associate with another complex at the tip to generate the ciliary ARL6GEF.

We note that in T. brucei, IFT27[T19N] is unable to enter cilia and bind IFT-B even after depletion of endogenous IFT27 (Huet et al., 2014), thus suggesting species-specific differences in the affinity of IFT27-GDP for the rest of the IFT-B complex.

Implications for the molecular basis of Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS)

The recent discovery that IFT27 is mutated in a BBS family [BBS19] has implicated it as a potential regulator of BBSome function (Aldahmesh et al., 2014). Here, we have shown that IFT27 controls ciliary exit of the BBSome through its interaction with ARL6. Hence, in addition to a failure to transport signaling receptors into cilia, the multitude of symptoms seen in BBS patients is also likely a result of defective ciliary export and aberrant ciliary accumulation of signaling receptors. These results are clinically relevant and future work promises to unravel the molecular mechanisms linking BBSome dysfunction and disease.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies and Reagents

Antibodies against the following proteins were used: actin (Sigma, #A2066), IFT88 (Proteintech), IFT57 (Proteintech), cMyc (9E10), GST (Life Technologies, #A-5800), GFP (Nachury et al., 2007), acetylated tubulin (6-11B-1), ARL6 (Jin et al., 2010), BBS5 (Proteintech), BBS4 (Nachury et al., 2007) and IFT27 (Keady et al., 2012). Chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich except for GTPγS (Roche) and [3H]GDP/[35S]GTPγS (Perkin-Elmer).

Cell Culture and Transfections

Stable IMCD3 Flp-In cell lines were generated as described (Ye et al., 2013). To generate pEF5-FRT-NG3-BBS1, the cDNA sequence of mNeonGreen (NG) was assembled by gene synthesis and inserted in three tandem repeats into pEF5-FRT-DEST vector before Gateway-mediated recombination of mBBS1. Transient transfections used XtremeGENE9 (Roche). For IFT27 knockdown, IMCD3 cells were transfected with 30 nM of either IFT27 siRNA (Qiagen, #SI02743860) or AllStars Negative Control siRNA (Qiagen, #SI03650318) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Life Technologies). Ciliation was induced by shifting cells from 10% to 0.2% serum 24 h after transfection, and cells were fixed 48 to 72 h posttransfection. Ift27−/− MEFs were from Gregory Pazour (U. Mass.). Arl6−/− MEFs were derived from E13.5 Arl6 knockout mice (Zhang et al., 2011) according to standard protocols. All cells were fixed and stained as described (Breslow et al., 2013).

LAP purifications and mass spectrometry

Purification of LAP-tagged protein complexes was performed as previously described (Nachury, 2008) with modifications (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

Recombinant Protein Expression and Purification

Recombinant proteins were expressed in E. coli Rosetta (DE3) pLysS. ARL6 and SAR1A were expressed from derivatives of pGEX6P with HRV3C-cleavable GST tags. IFT25 and IFT27 were expressed from derivatives of pRSFDuet1 with HRV3C-cleavable GST and TEV-cleavable His tags, respectively. ARL6 and SAR1A were purified on Glutathione Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) resin and eluted by HRV3C cleavage. IFT25/IFT27 was typically purified with Glutathione Sepharose 4B followed by Ni-NTA (Thermo Scientific). After affinity purification, recombinant proteins were subjected to size-exclusion chromatography. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for other proteins.

GST-Capture Assay

100 μg ARL6 or SAR1A (control) was mixed with 100 μg IFT25/IFT27-GST or GST (control) in 250 to 290 μl HBS* buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2) containing either 1 mM GDP, 1 mM GTPγS, 20 μM EDTA, or 1 mM GDP/2 mM AlCl3/20 mM NaF. Reactions were incubated at 30°C for 1 h before binding at 4°C for 90 min to 10 μL Glutathione Sepharose 4B beads. Proteins were eluted in LDS sample buffer.

Nucleotide Exchange Assay

Binding of radiolabeled nucleotides to ARL6 was measured by filter assays (Northup et al., 1982) with modifications (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

Turbidity Assay

20 μM ARL6 was mixed on ice with 20 μM EDTA and 10 to 200 μM of IFT25/IFT27 variants in a total reaction volume of 300 μL and then transferred into a pre-heated quartz cuvette (Bio-Rad, #170-2504). EDTA-induced ARL6 precipitation at 37°C was followed at 350 nm with a Thermo Scientific Nanodrop Spectrophotometer 2000c machine taking readings every 5 sec for 20 min.

Live Cell Imaging and Photokinetic Assays

Cells were seeded on 25 mm coverslips and transfected with siRNA as above. Imaging was conducted in Phenol red-free imaging and on a DeltaVision system (Applied Precision) equipped with a PlanApo 60×/1.40 NA Oil, a PlanApo 60×/1.49 NA TIRF Oil objective lens (Olympus) and images were captured with a sCMOS camera (Applied Precision).

For Fluorescence Loss After Photobleaching (FLAP) assay, cytoplasmic NG3-BBS1 was photobleached with a 488 nm laser and cilia were observed by widefield imaging with a PlanApo 60×/1.40 NA Oil lens (Olympus). In FLAP, the cytoplasm is photobleached in multiple areas between the first and second time point of acquisition. The time interval for the first two time points was 30 s. The time interval was then doubled for the next two time points and continued to double every two time points thereafter. Excluding the initial 30 s time interval for photobleaching, the total time for the FLAP assay was 1860 s. The signal intensities from cilia, cytoplasmphotobleached, cytoplasmnon-photobleached and background were measured with ImageJ (NIH). For Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) assay, ciliary NG3-BBS1 was photobleached by the 488 nm laser and cilia were observed by TIRF with a PlanApo 60×/1.49 NA TIRF Oil lens (Olympus). Images were acquired every 5 s after photobleaching. The signal intensities were measured as for FLAP. Analysis of photokinetic data is detailed in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Structured Illumination Microscopy

siRNA-treated IMCD3-[NG3-BBS1] cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at 4°C and immunostained for IFT88. 3D-SIM images were acquired by a DeltaVision OMX imaging system equipped with three EMCCD cameras (Andor Technology Ltd) and a UPlanSApo 100x/1.4 NA Oil lens (Olympus). 12 to 20 Z sections were acquired for each cilium with a step size of 125 nm. Structured illuminated images for NG3-BBS1 1 and IFT88 were reconstructed and shift-corrected with SoftWoRx 6.0 (DeltaVision).

Genome editing of IMCD3 cells

Arl6−/− and Ift27−/− IMCD3 cell lines were generated using the CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing method previously described (Cong et al., 2013) and pX330 (Addgene 42230). The guide sequences used were AAGCCGCGATATGGGCTTGC for Arl6 and GGAAATGGGTCCCGTCGCTG for Ift27. Targeting CRISPR plasmids were transfected into IMCD3 cells with Lipofectamine 2000, individual clones isolated by limited dilution and Arl6−/− and Ift27−/− clones identified by immunoblotting for ARL6 and IFT27.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Greg Pazour (U. Mass) for gift of the Ift27−/− MEFs and IFT27 antibody, Saikat Mukhopadhyay (UT Southwestern) for GPR161 antibody, Hua Jin for generating the LAP-IFT88 IMCD3 cell line and deriving the Arl6−/− MEFs, Val Sheffield (U. Iowa) for the gift of Arl6−/− mice, Wei Guo (U. Penn) for a Sec8 construct, Brunella Franco (Federico II U., Italy) for an Ofd1 construct, Or Gozani (Stanford U.) for a Plcδ construct, Suzanne Pfeffer (Stanford U.) for careful reading of the manuscript, and the Nachury lab for helpful comments and discussions. This work was supported by a grant to M.V.N. from NIH/NIGMS (R01GM089933). G.M.L. was supported by a National Science Scholarship from A*STAR, Singapore. A.R.N. and D.K.B. were supported by Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation fellowships DRG 2160-13 and DRG 2087-11.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aldahmesh MA, Li Y, Alhashem A, Anazi S, Alkuraya H, Hashem M, Awaji AA, Sogaty S, Alkharashi A, Alzahrani S, et al. IFT27, encoding a small GTPase component of IFT particles, is mutated in a consanguineous family with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:3307–3315. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berbari NF, Lewis JS, Bishop GA, Askwith CC, Mykytyn K. Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins are required for the localization of G protein-coupled receptors to primary cilia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4242–4246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711027105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhogaraju S, Taschner M, Morawetz M, Basquin C, Lorentzen E. Crystal structure of the intraflagellar transport complex 25/27. EMBO J. 2011;30:1907–1918. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow DK, Koslover EF, Seydel F, Spakowitz AJ, Nachury MV. An in vitro assay for entry into cilia reveals unique properties of the soluble diffusion barrier. J Cell Biol. 2013;203:129–147. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201212024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman IM, Desai A. A combined approach for the localization and tandem affinity purification of protein complexes from metazoans. Sci STKE. 2005;2005:pl1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2662005pl1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherfils J, Zeghouf M. Regulation of small GTPases by GEFs, GAPs, and GDIs. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:269–309. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DG, Diener DR, Himelblau AL, Beech PL, Fuster JC, Rosenbaum JL. Chlamydomonas kinesin-II-dependent intraflagellar transport (IFT): IFT particles contain proteins required for ciliary assembly in Caenorhabditis elegans sensory neurons. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:993–1008. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.4.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola T, Perret-Menoud V, Gattesco S, Magnin S, Pombo I, Blank U, Regazzi R. The death domain of Rab3 guanine nucleotide exchange protein in GDP/GTP exchange activity in living cells. Biochem J. 2002;362:273–279. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNitto JP, Delprato A, Gabe Lee MT, Cronin TC, Huang S, Guilherme A, Czech MP, Lambright DG. Structural basis and mechanism of autoregulation in 3-phosphoinositide-dependent Grp1 family Arf GTPase exchange factors. Mol Cell. 2007;28:569–583. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domire JS, Green JA, Lee KG, Johnson AD, Askwith CC, Mykytyn K. Dopamine receptor 1 localizes to neuronal cilia in a dynamic process that requires the Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;68:2951–2960. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0603-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson JG, Jackson CL. ARF family G proteins and their regulators: roles in membrane transport, development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:362–375. doi: 10.1038/nrm3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliegauf M, Benzing T, Omran H. When cilia go bad: cilia defects and ciliopathies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:880–893. doi: 10.1038/nrm2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goody R, Hofmann-Goody W. Exchange factors, effectors, GAPs and motor proteins: common thermodynamic and kinetic principles for different functions. Eur Biophys J. 2002;31:268–274. doi: 10.1007/s00249-002-0225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huet D, Blisnick T, Perrot S, Bastin P. The GTPase IFT27 is involved in both anterograde and retrograde intraflagellar transport. Elife. 2014;3:e02419–e02419. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iomini C, Babaev-Khaimov V, Sassaroli M, Piperno G. Protein particles in Chlamydomonas flagella undergo a transport cycle consisting of four phases. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:13–24. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzen A, Pylypenko O, Goody RS, Alexandrov K, Rak A. Nucleotide exchange via local protein unfolding--structure of Rab8 in complex with MSS4. EMBO J. 2006;25:1445–1455. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, White SR, Shida T, Schulz S, Aguiar M, Gygi SP, Bazan JF, Nachury MV. The conserved Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins assemble a coat that traffics membrane proteins to cilia. Cell. 2010;141:1208–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keady BT, Samtani R, Tobita K, Tsuchya M, San Agustin JT, Follit JA, Jonassen JA, Subramanian R, Lo CW, Pazour GJ. IFT25 links the signal-dependent movement of hedgehog components to intraflagellar transport. Dev Cell. 2012;22:940–951. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechtreck KF, Johnson EC, Sakai T, Cochran D, Ballif BA, Rush J, Pazour GJ, Ikebe M, Witman GB. The Chlamydomonas reinhardtii BBSome is an IFT cargo required for export of specific signaling proteins from flagella. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:1117–1132. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loktev AV, Zhang Q, Beck JS, Searby CC, Scheetz TE, Bazan JF, Slusarski DC, Sheffield VC, Jackson PK, Nachury MV. A BBSome subunit links ciliogenesis, microtubule stability, and acetylation. Dev Cell. 2008;15:854–865. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay S, Wen X, Ratti N, Loktev A, Rangell L, Scales SJ, Jackson PK. The ciliary G-protein-coupled receptor Gpr161 negatively regulates the sonic hedgehog pathway via cAMP signaling. Cell. 2013;152:210–223. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachury MV. How do cilia organize signalling cascades? Phil Trans R Soc B. 2014;369:20130465. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachury MV. Tandem affinity purification of the BBSome, a critical regulator of Rab8 in ciliogenesis. Methods Enzymol. 2008;439:501–513. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)00434-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachury MV, Loktev AV, Zhang Q, Westlake CJ, Peränen J, Merdes A, Slusarski DC, Scheller RH, Bazan JF, Sheffield VC, et al. A core complex of BBS proteins cooperates with the GTPase Rab8 to promote ciliary membrane biogenesis. Cell. 2007;129:1201–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachury MV, Seeley ES, Jin H. Trafficking to the ciliary membrane: how to get across the periciliary diffusion barrier? Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:59–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northup JK, Smigel MD, Gilman AG. The guanine nucleotide activating site of the regulatory component of adenylate cyclase. Identification by ligand binding. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:11416–11423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuoffer C, Wu SK, Dascher C, Balch WE. Mss4 does not function as an exchange factor for Rab in endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi transport. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1305–1316. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.7.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou G, Blacque OE, Snow JJ, Leroux MR, Scholey JM. Functional coordination of intraflagellar transport motors. Nature. 2005a;436:583–587. doi: 10.1038/nature03818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou G, Qin H, Rosenbaum JL, Scholey JM. The PKD protein qilin undergoes intraflagellar transport. Curr Biol. 2005b;15:R410–R411. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen LB, Geimer S, Rosenbaum JL. Dissecting the molecular mechanisms of intraflagellar transport in Chlamydomonas. Curr Biol. 2006;16:450–459. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen LB, Miller MS, Geimer S, Leitch JM, Rosenbaum JL, Cole DG. Chlamydomonas IFT172 is encoded by FLA11, interacts with CrEB1, and regulates IFT at the flagellar tip. Curr Biol. 2005;15:262–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piperno G, Mead K. Transport of a novel complex in the cytoplasmic matrix of Chlamydomonas flagella. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4457–4462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin H, Wang Z, Diener D, Rosenbaum J. Intraflagellar transport protein 27 is a small G protein involved in cell-cycle control. Curr Biol. 2007;17:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JL, Witman GB. Intraflagellar transport. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:813–825. doi: 10.1038/nrm952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheidecker S, Etard C, Pierce NW, Geoffroy V, Schaefer E, Muller J, Chennen K, Flori E, Pelletier V, Poch O, et al. Exome sequencing of Bardet-Biedl syndrome patient identifies a null mutation in the BBSome subunit BBIP1 (BBS18) J Med Genet. 2014;51:132–136. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo S, Zhang Q, Bugge K, Breslow DK, Searby CC, Nachury MV, Sheffield VC. A novel protein LZTFL1 regulates ciliary trafficking of the BBSome and Smoothened. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e100235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner NC, Lambert GG, Chammas A, Ni Y, Cranfill PJ, Baird MA, Sell BR, Allen JR, Day RN, Israelsson M, et al. A bright monomeric green fluorescent protein derived from Branchiostoma lanceolatum. Nat Methods. 2013;10:407–409. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung CH, Leroux MR. The roles of evolutionarily conserved functional modules in cilia-related trafficking. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:1387–1397. doi: 10.1038/ncb2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker J, Sczakiel G, Feuerstein J, John J, Goody RS, Wittinghofer A. Expression of p21 proteins in Escherichia coli and stereochemistry of the nucleotide-binding site. EMBO J. 1986;5:1351–1358. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter IR. The guanine nucleotide-binding switch in three dimensions. Science. 2001;294:1299–1304. doi: 10.1126/science.1062023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Fan ZC, Williamson SM, Qin H. Intraflagellar transport (IFT) protein IFT25 is a phosphoprotein component of IFT complex B and physically interacts with IFT27 in Chlamydomonas. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Q, Zhang Y, Li Y, Zhang Q, Ling K, Hu J. The BBSome controls IFT assembly and turnaround in cilia. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:950–957. doi: 10.1038/ncb2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodland HR, Pestell RQ. Determination of the nucleoside triphosphate contents of eggs and oocytes of Xenopus laevis. Biochem J. 1972;127:597–605. doi: 10.1042/bj1270597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wren KN, Craft JM, Tritschler D, Schauer A, Patel DK, Smith EF, Porter ME, Kner P, Lechtreck KF. A differential cargo-loading model of ciliary length regulation by IFT. Curr Biol. 2013;23:2463–2471. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye F, Breslow DK, Koslover EF, Spakowitz AJ, Nelson WJ, Nachury MV. Single molecule imaging reveals a major role for diffusion in the exploration of ciliary space by signaling receptors. Elife. 2013;2:e00654. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Nishimura D, Seo S, Vogel T, Morgan DA, Searby C, Bugge K, Stone EM, Rahmouni K, Sheffield VC. Bardet-Biedl syndrome 3 (Bbs3) knockout mouse model reveals common BBS-associated phenotypes and Bbs3 unique phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:20678–20683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113220108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Seo S, Bugge K, Stone EM, Sheffield VC. BBS proteins interact genetically with the IFT pathway to influence SHH-related phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:1945–1953. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.