Abstract

The human formyl-peptide receptor (FPR)-2 is a G protein-coupled receptor that transduces signals from lipoxin A4, annexin A1, and serum amyloid A (SAA) to regulate inflammation. In this study, we report the creation of a novel mouse colony in which the murine FprL1 FPR2 homologue, Fpr2, has been deleted and describe its use to explore the biology of this receptor. Deletion of murine fpr2 was verified by Southern blot analysis and PCR, and the functional absence of the G protein-coupled receptor was confirmed by radioligand binding assays. In vitro, Fpr2−/− macrophages had a diminished response to formyl-Met-Leu-Phe itself and did not respond to SAA-induced chemotaxis. ERK phosphorylation triggered by SAA was unchanged, but that induced by the annexin A1-derived peptide Ac2–26 or other Fpr2 ligands, such as W-peptide and compound 43, was attenuated markedly. In vivo, the antimigratory properties of compound 43, lipoxin A4, annexin A1, and dexamethasone were reduced notably in Fpr2−/− mice compared with those in wild-type littermates. In contrast, SAA stimulated neutrophil recruitment, but the promigratory effect was lost following Fpr2 deletion. Inflammation was more marked in Fpr2−/− mice, with a pronounced increase in cell adherence and emigration in the mesenteric microcirculation after an ischemia–reperfusion insult and an augmented acute response to carrageenan-induced paw edema, compared with that in wild-type controls. Finally, Fpr2−/− mice exhibited higher sensitivity to arthrogenic serum and were completely unable to resolve this chronic pathology. We conclude that Fpr2 is an anti-inflammatory receptor that serves varied regulatory functions during the host defense response. These data support the development of Fpr2 agonists as novel anti-inflammatory therapeutics.

The polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) is the first WBC type to egress from the blood during acute inflammation, followed by the monocyte (1). This process is orchestrated by the timed expression of cell-associated and soluble mediators, including adhesion molecules and cytokines or chemokines. At the site of inflammation, PMN life span is increased from hours to days, and monocytes differentiate into macrophages (Mϕs) to direct a series of events leading to safe resolution of the inflammatory process, with removal of the initial insult and restoration of tissue homeostasis (1, 2).

Because they transduce the action of chemokines and other inflammatory signals that are central to the adaptive and innate immune responses (3, 4), the role of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) in host defense has been the object of intense scrutiny.

The concept that acute inflammation resolves through active processes is relatively novel (2, 5). An important function, in this context, is served by the arachidonate derivative lipoxin A4 (LXA4) (6) and by the glucocorticoid-modulated protein annexin A1 (AnxA1) (7), both of which operate in the inflamed tissue in a temporal and spatial fashion. LXA4 and AnxA1 exert exquisite control over PMN biology, potently inhibiting cell interaction with the vascular endothelium and, at the site of inflammation, promoting apoptosis, phagocytosis, and egress (8-10). The major anti-inflammatory properties of LXA4, aspirin-triggered LXA4, and AnxA1 on PMNs are mediated through a specific GPCR, termed formyl peptide receptor (FPR) 2/LXA4 receptor (ALX) (11).

Human FPR2/ALX, FPR, and FPR3 form a subgroup of receptors (12) linked to inhibitory G proteins so that their activation leads to transient calcium fluxes, ERK phosphorylation (13), and in some cases cell locomotion (14).

FPR2/ALX seems unusual, being used by both lipid and protein ligands (11, 12, 15). Not only does it transduce the anti-inflammatory effects of LXA4 in many systems (8) as well as the neuroprotective effects of humanin (16) but it also can mediate proinflammatory responses to serum amyloid A (SAA) and other peptides (13, 17, 18). The ability of FPR2/ALX to mediate two opposite effects may be traced to different receptor domains used by different agonists (19).

There are no specific antagonists or neutralizing Abs that can be used to delineate the function of FPR2/ALX in vivo (12), so most notions concerning its function have been inferred from in vitro studies that may not reflect the true role of this receptor in the complex and dynamic environment of an ongoing inflammatory response. To address this important question, we therefore have generated a novel mouse line in which the gene for Fpr2 [the murine homologue of FPR2/ALX, formerly referred to as Fpr-rs2 (20)] has been deleted. Fpr2 has 76 and 63% identity with human FPR2/ALX and FPR3, respectively (12, 21), and is known to be activated by SAA (22) and LXA4 (23). Our aim was to determine the function of this receptor in inflammation as well as in response to natural and synthetic ligands.

Materials and Methods

Fpr2 ligands and reagents

GST-tagged human recombinant annexin A1 (hrAnxA1), produced in Escherichia coli, was purified protein by Sepharose column purification using GSTrap (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, U.K.). Endotoxin was monitored and found to be below detectable levels (0.05 endotoxin U/ml) using the E-Toxate kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). W-peptide and peptide Ac2–26 of annexin A1 (Ac2–26; acetyl-AMVSEFLKQAWIENEEQEYVVQTVK; Mr 3050) were synthesized by (Cambridge Bioscience, Cambridge, U.K.). LXA4 was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). IL-1β and SAA were purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hills, NJ). Formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP), zymosan A, and dexamethasone 21-phosphate disodium salt were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Compound 43 (Cpd43) was a generous gift from Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA).

Generation of the Fpr2−/− mouse

Fpr2−/− mice were generated by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells using a dual purpose targeting/reporter vector. Genomic clones containing Fpr sequences were isolated from a bacteriophage λ library (129/SvJ; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) by plaque hybridization. Inserts from positive plaques were subcloned into pZero (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), end-sequenced, and then aligned with the fpr locus on chromosome 17. A pgk-neo cassette was inserted into one of these clones (p2.1) just downstream of the ATG start codon for Fpr2, using the technique of site-specific recombination in bacteria. The sequences of the primers used to achieve this step were forward 5′-tcagaaggagccaaatatctgagaaatggttgtttttgaaaactttcaggtgcagacaaaATGgctagcccttctgcttaatttgtgcctgg and reverse 5′-tgctgtgaaagaaaagtcagccaatgctagattcagataccagatagtggtgacagtgtgtggcgtagaggatctgcltcatgtttgac. With the plasmid pPGK-neo-FRT as a template for PCR, these primers amplified a fragment of 2.2kb containing the pgk-neo cassette in reverse orientation, flanked by 63-bp arms showing homology to Fpr2. This fragment was electroporated along with plasmid p2.1 into E. coli strain HS996 using the RED-ET subcloning kit supplied by Gene Bridges (Heidelberg, Germany). The novel NheI site (gctagc) located immediately after the ATG start codon in the forward primer was used for the subsequent in-frame insertion of GFP (Qbiogene, Irvine, CA) and also to facilitate Southern blot screening. All of the steps were confirmed by sequencing.

The targeting vector was linearized by digestion with SnaBI and electroporated into embryonic stem cells (strain 129SvEv). Neomycin-resistant colonies were picked and screened for correct insertion by Southern blot analysis using probes located beyond both the 5′ and 3′ ends of the vector arms and also a probe for GFP. Clones showing homologous recombination into the Fpr2 locus were expanded, karyotyped by G-banding, and then injected into the blastocysts of C57Bl6 females (Caliper Life Sciences, Cambridge, MA).

Male chimaeras showing >95% agouti coat color were paired with C57Bl6 females. F1 offspring were screened by PCR of tail clip DNA for germline transmission of the targeted allele using the Extract-N-Amp system (Sigma-Aldrich). The primers used for genotyping were F1 (tgagtgtcatgtcagaaggagcc), B11 (cggaatccagctacccaaatc), and GB4 (ataaccttcgggcatggcactc). The F1/B11 pair produces a band of 233 bp from the wild-type (WT) allele, whereas F1 and GB4 produce a band of 351 bp if the targeted allele is present. Cycling conditions were 92°C for 30s, 54°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 15 s for 33 cycles. Heterozygotes were mated to produce F2 homozygotes. Genotyping was performed by PCR and confirmed by Southern blot analysis (Fig. 1).

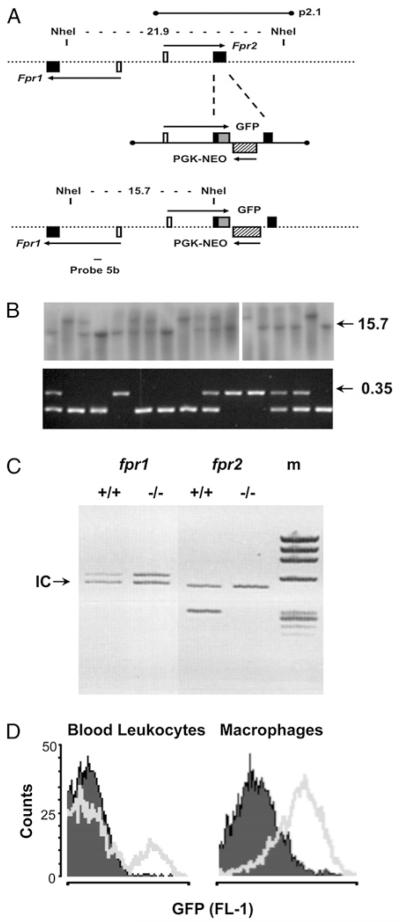

FIGURE 1. Generation of the Fpr2−/− mouse colony.

A, Schematic representation of a region of ~30 kb of mouse genomic DNA spanning the fpr1 and fpr2 genes. The alignment of the 14.12-kb λ insert p2.1 is shown, along with the locations of the NheI restriction sites used for Southern blot screening. Filled boxes are coding exons; white boxes are noncoding exons; the hatched box represents the Pgk-neo cassette inserted in reverse orientation into the coding region of Fpr2; the gray box shows GFP fused in-frame with the ATG start codon; arrows indicate primary transcripts. B, Southern blot analysis (top panel) screening of tail clip DNA digested with the enzyme NheI. Probe 5b generates bands of 21.9 and 15.7 kb for WT and targeted alleles, respectively. Genotyping by multiplex PCR (bottom panel) also is reported. The F1/B11 primer pair produces a band of 233 bp using WT DNA, whereas the F1/GB4 pair gives a band of 351 bp (0.35) if the targeted allele is present. C, Multiplex PCR was used to compare the expression of fpr1 and fpr2 in WT and Fpr2−/− mice. Primers were compared with the internal control gene (18S rRNA) denoted by the arrow. D, Detection of the GFP target/reporter insert by flow cytometry. Cell samples (peripheral blood or Mϕs) from WT (opaque) or Fpr2−/− (transparent) mice as analyzed by flow cytometry in the FL-1 channel (representative of six or more distinct cell preparations).

Genotype and litter size data on Fpr2−/− mice (16 litters, ~100 animals) confirmed that the gene assorted according to the expected Mendelian ratio and that there were no breeding abnormalities. The transgenic mice were viable, fertile, and showed no obvious developmental or behavioral defects. Similarly, no significant differences in the numbers of peritoneal resident cells (~4 × 106) or bone marrow or circulating PMNs were evident between WT littermate and Fpr2−/− mice (~20 × 106 and ~2.5 × 106 cells per milliliter, respectively; n = 6 mice per group).

Cellular and biochemical analyses

Preparation of Mϕs

Identical results were obtained using either bone marrow or peritoneal Mϕs. Bone marrow Mϕs were obtained from femurs and tibias of 4–6-wk-old WT littermate controls and Fpr2−/− mice. The marrow was flushed from the bone, washed, resuspended (2 × 106 cells per milliliter) in DMEM supplemented with l-glutamine, penicillin/streptomycin (Lonza Biologics, Slough, U.K.), 20% FCS, and 30% L929 conditioned medium, and incubated at 37°C for 5 d. Biogel-elicited Mϕs were harvested 4 d after i.p. injection of 1 ml, 2% P-100 gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in sterile PBS. Cell suspensions were passed through 40-μm cell strainers (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) before being washed and seeded.

Mϕ chemotaxis

The commercially available Neuroprobe ChemoTx 96-well plate (Receptor Technologies, Leamington Spa, U.K.) with poly-carbonate membrane filters and 5-μm membrane pores was used. Mϕs were resuspended at a concentration of 4 × 106 cells per milliliter in RPMI 1640 containing 0.1% BSA. The chemotaxis assay was performed by adding chemotactic stimuli to the bottom wells, with 105 Mϕ cell suspension in 25 μl placed above the membrane. Plates were incubated for 120 min in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. Migrated cells were quantified after 4 h of incubation with alamarBlue (Serotec, Oxford, U.K.) by comparison with a standard curve constructed with known Mϕ numbers (range 0–4 × 106). Plates were read at 530–560 nm excitation and 590 nm emission wavelengths for fluorescence values.

Radioligand binding assays

These were conducted as described previously (24). Briefly, primary peritoneal Mϕs were resuspended at a concentration of 10 × 106 cells per milliliter in PBS containing Ca2+ and Mg2+ and placed on ice. The tracer ([125I]W-peptide) was prepared following manufacturer’s instructions (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Belmont, CA) and dissolved in 1 ml distilled water.

The unlabeled W-peptide also was dissolved in distilled water to a final concentration of 1 μM. Subsequently a 500 μM working stock was prepared; this was used to determine the extent of nonspecific binding by the radiolabeled tracer. Together with total binding of the tracer; specific binding can be estimated by total binding minus nonspecific binding.

The reaction mixture then was incubated for 1 h on ice, after which it was transferred to a vacuum filtration unit equipped with 25-mm GF/C filter membranes onto which any cells and bound tracer would be retained. The filters then were washed three times using 4 ml aliquots of 10 mM ice-cold Tris-HCl to remove any unbound tracer. After the wash step, the filter paper was transferred into recipient tubes, and the amount of bound tracer was determined using a γ-counter. This experiment was repeated three times to confirm the reproducibility of the results obtained.

Phospho-ERK signaling

Peritoneal Mϕs were equilibrated for 30 min in Glutamax DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 50 U penicillin/streptomycin prior to incubation with the specified ligands in six-well plates for 10 min at 37°C. Mϕ lysates were analyzed by standard SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Blots were probed for rabbit anti–phospho-p44/42 MAP L(polyclonal anti–phospho-ERK; 1:1000 dilution) or p44/42 MAPK Abs (total ERK, 1:1000 dilution; clone 137F5; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) was diluted in 0.3% BSA/Tween 20 and Tris-buffered saline and incubated with the membrane overnight. Membranes were further incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA) and proteins were detected by ECL visualized on hyperfilm (GE Healthcare).

Histology

Analysis was conducted at the 4 h time point: joints were trimmed, placed in decalcifying solution (0.1 mM EDTA in PBS) for 25 d and then embedded in paraffin. Sections (5 μm) were deparaffinized with xylene and stained with H&E. Three sections per animal were evaluated. Phase-contrast digital images were taken using the Image Pro image analysis software package.

Inflammation assays

IL-1β–induced air pouch and zymosan-induced peritonitis

The air-pouch procedure was carried out as described previously (25), injecting 20 ng mouse IL-1β (PeproTech) in 0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose on day 6 after air-pouch induction. Zymosan peritonitis was induced by injecting i.p. 1 mg zymosan A (Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.5 ml PBS as previously described (26). Compounds were given i.v. immediately before IL-1β or zymosan. In all of the cases, either air pouches or peritoneal cavities were lavaged 4 h later using 2 or × ml, respectively, PBS-containing 25 U/ml heparin and 0.3 mM EDTA. Exudate fluids were stained with Turk’s solution to allow identification of differential PMN and PBMC counts in the total cell population by light microscopy. Proportions of specific leukocyte populations were confirmed and quantified by FACS (see below).

Carrageenan-induced paw edema

Paw edema was induced as previously described (27). Briefly, animals received subplantar administration of 50 μl carrageenan 1% (w/v) in saline. The volume was measured by using a hydroplethysmometer with mice paw adaptors (Ugo Basile, Varese, Italy) immediately before subplantar injection and 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h thereafter. Changes in paw volume were calculated by subtracting the initial paw volume (basal) from the paw volume measured at each time point.

Intravital microscopy of the mesenteric microcirculation

Intravital microscopy was performed as previously reported (28). Briefly, following anesthesia, cautery incisions were made along the abdominal region, and the superior mesenteric artery was clamped with a microaneurysm clip (Harvard Apparatus, Edenbridge, U.K.) to induce ischemia in the mesentery for 30 min prior to a 45 min reperfusion phase. Sham-operated mice were subject to anesthesia and other surgical procedures without clamping of superior mesenteric artery and analyzed 75 min after laparotomy. Mesenteries were superfused with thermostated (37°C) bicarbonate-buffered solution [7.71 g/l NaCl, 0.25 g/l KCl, 0.14 g/l MgSO4, 1.51 g/l NaHCO3, and 0.22 g/l CaCl2 (pH 7.4), gassed with 5% CO2/95%N2] at a rate of 2 ml/min. One to three randomly selected postcapillary venules (diameter between 20 to 40 μm; visible length of at least 100 μm) were observed for each mouse (minimum of five animals per genotype). Leukocyte adhesion was measured by counting static (at least 30 s) cells clearly visible on the vessel wall in a 100 μm stretch. Leukocyte emigration from the microcirculation into the tissue was quantified by counting the number of cells in a 100 × 50 μm2 area outside the vessel.

All of the animal studies were conducted in accordance with current U.K. Home Office regulations and complied with local ethical and operational guidelines.

K/B × N serum-induced inflammatory arthritis

Arthritis was induced by injection, on day 0, of 150 μl pooled K/B × N arthrogenic serum (29). Disease development was monitored by assessing the clinical index: one point was given for each digit, tarsal, or wrist joint that presented with erythema plus swelling; a maximum of 22 points could be scored per animal. Cumulative disease incidence was determined by the number of mice that presented a minimum of two paws with a clinical score and quantified as a percentage of the total group.

FACS analysis

Measurement of Fpr2 promoter activity and cell infiltrate by FACS

FACS analysis was used to assess the fluorescence of both stained and unstained cell populations. Fpr2−/− animals carried GFP within the promoter region of Fpr2 and therefore allowed analysis of both constitutive and induced promoter activities in naive, differentiating, and inflammatory cell populations by FL-1 analysis. This methodology also was used to confirm genotypes.

Quantification of specific leukocyte populations

Specific leukocyte populations were identified using the following conjugated monoclonal Abs (all at 10 mg/ml final concentrations): anti-mouse Ly-6G/Gr1+ (clone RB68C5; eBioscience, San Diego, CA), anti-mouse F4/80 (clone MCA497; Serotec), or isotype controls (eBR2a; eBioscience,) for 1 h at 4°C. Cell populations were analyzed for 10,000 events by FACSCalibur flow cytometry using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). The percentage of total events in each population was compared with total cell count to calculate specific cell infiltrate per cavity or pouch.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Student t test was used to compare two groups with parametric data distributions. Mann-Whitney U test was used for nonparametric data, such as the analysis for the ERK phosphorylation assays. Comparison between groups (e.g., of clinical scores and paw volumes) was made using ANOVA. All of the analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 4.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). In all of the cases, a p value < 0.05 was taken as significant.

Results

Generation and validation of the Fpr2−/− mouse colony

The targeting vector (Fig. 1A) underwent homologous recombination in 8 out of 96 embryonic stem cell clones. Blastocyst injections were performed using two different clones, both of which produced high-quality chimaeras capable of high-frequency germline transmission. Examples of genotyping results obtained by Southern blot analysis and multiplex PCR are shown in Fig. 1B and Fig. 1C. Expression of Fpr1 was similar in cells and tissues from WT and Fpr2−/− mice (Fig. 1C). The correct expression of the transgene was confirmed by detection of GFP fluorescence in a subpopulation of blood cells and primary Mϕs (Fig. 1D).

Phenotype of Fpr2−/− cells: Agonist-dependent readouts

Radioligand binding

The validity of our transgenic strategy was assessed using [125I]-labeled W-peptide, a synthetic hexapeptide that is a high-affinity ligand for Fpr2 (30). Specific binding to Mϕs was calculated in WT Mϕs by the addition of increasing concentrations of tracer (0.1–820 pmol) in the presence of a constant concentration of cold peptide (10 μM; Fig. 2A). The data were used to generate a Scatchard plot (Fig. 2B), which revealed the existence of both high- and low-affinity binding sites for W-peptide. This finding is in line with an earlier study (30). The high-affinity site had a Kd of ~44 pmol and a Bmax of ~12 pmol.

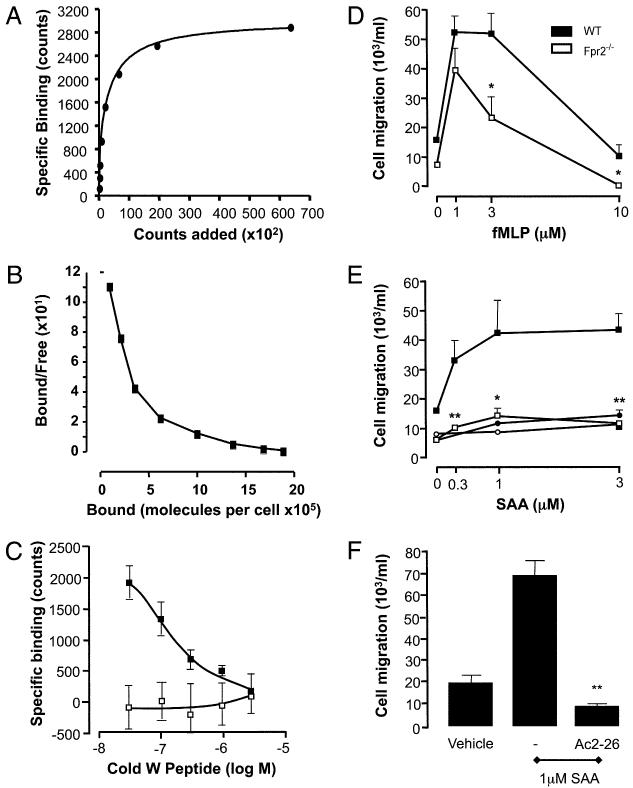

FIGURE 2. Functional deletion of Fpr2 in vitro.

A, Specific binding of [125I]-labeled W-peptide is represented as number of molecules bound compared with the γ-counts. B, This data allowed the calculation of a Scatchard plot. C, Fpr2-specific binding to WT (black) and Fpr2−/− (white) Mϕs was assessed by measuring the competitive displacement of the [125I]-labeled W-peptide trace by cold peptide. D and E, The chemotactic responses of WT (black) and Fpr2−/− (white) Mϕs toward different concentrations of (D) fMLP, (E) SAA, or Ac2–26 were assessed by using 5-μm 96-well ChemoTx plates. Data are mean ± SEM of three experiments in quadruplicate. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, compared with respective WT Mϕ group by Student t test. F, WT Mϕs were pretreated with either vehicle or 1 μM Ac2–26 for 10 min prior to SAA-induced (1 μM) chemotaxis. **p < 0.01; compared with vehicle-treated group by Student t test (n = 4).

WT Mϕs bound the tracer peptide and this was displaced by unlabeled peptide (30–3000 nM) in a concentration-dependent fashion (Fig. 2C). In contrast, the tracer was unable to bind to Fpr2−/− Mϕ cells, thus confirming deletion of the receptor.

Mϕ chemotaxis

To determine the functional relevance of the receptor knockout, we used established cellular readouts in vitro. fMLP provoked optimal Mϕ chemotaxis at 1 μM [in line with its affinity for mouse Fpr1 (31)]. At concentrations >1 μM, the effect of fMLP was partly reliant on Fpr2, because it was attenuated significantly when Mϕs were prepared from Fpr2−/− mice (Fig. 2D).

Chemotaxis was promoted consistently by SAA in WT cells (Fig. 2E) but absent in Fpr2−/− Mϕs. Both AnxA1 (data not shown) and its N-terminal–derived peptide Ac2–26 (Fig. 2E) were inactive as chemoattractants, but SAA-induced chemotaxis was inhibited markedly by Mϕ pretreatment with 1 μM Ac2–26 (Fig. 2F).

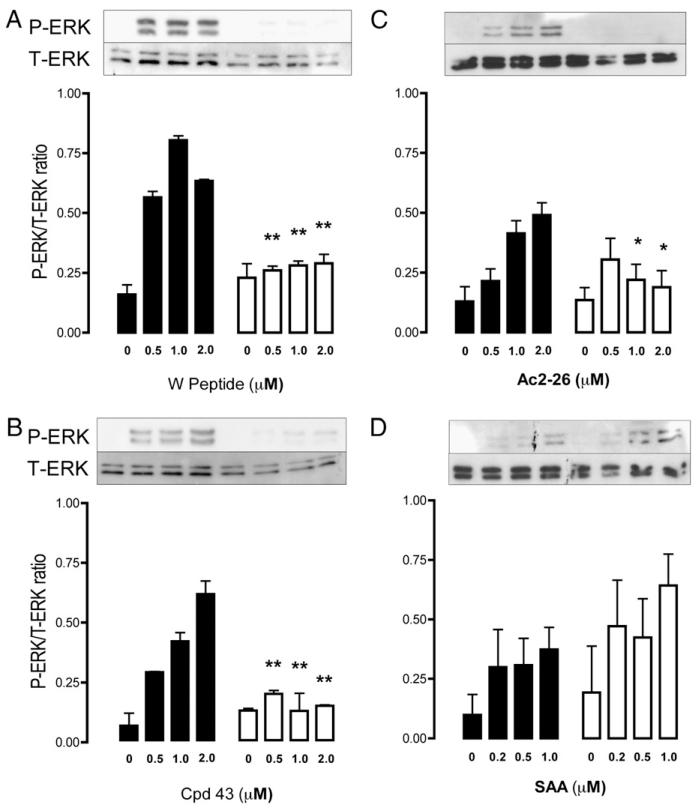

ERK phosphorylation

We chose ERK phosphorylation as a robust readout (13) to test the responsiveness of Fpr2−/− cells to nonchemokinetic receptor ligands. We used two selective, synthetic compounds, W-peptide (30) and a nonpeptidic molecule, Cpd43 (32), as agonists. In both cases, addition to Mϕs provoked a concentration-dependent rapid phosphorylation of ERK in WT cells (Fig. 3A) but not in Fpr2−/− Mϕs (Fig. 3B). Equally important, the agonistic effect of peptide Ac2–26, which is known to activate all FPRs under in vitro experimental settings (33), was abrogated in Fpr2−/− Mϕs (Fig. 3C), whereas the response elicited by SAA was retained (Fig. 3D).

FIGURE 3. Intracellular signaling induced by Fpr2 ligation.

Phosphorylation of ERK was monitored by Western blot analysis, with Mϕs exposed to a concentration range of Wpeptide, Cpd43, Ac2–26, and SAA (A–D, respectively) for 10 min at 37°C. Representative blots are shown; respective bar histograms showing cumulative data (n = 3). Closed bars, WT Mϕs; open bars, Fpr2−/− Mϕs. Data, expressed as the ratio of phospho-ERK to total ERK, are mean ± SEM of three distinct experiments with different Mϕ cultures. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; compared with respective WT Mϕs by Mann-Whitney U test.

Fpr2 pharmacology and models of acute inflammation

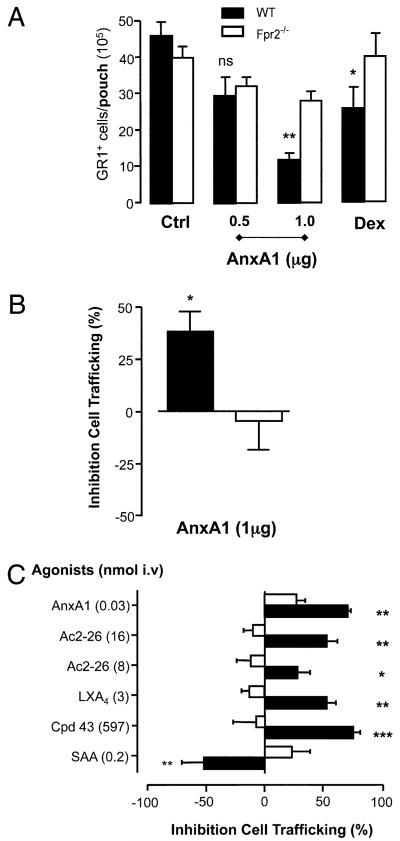

Treatment with hrAnxA1 produced dose-response inhibition of PMN (Gr1+ cells) accumulation into murine dorsal air pouches inflamed with IL-1β, with substantial inhibition (≥70%, p < 0.01, n = 10) at a dose of 1 mg per mouse (~30 pmol; Fig. 4A). The inhibitory action of AnxA1 was attenuated greatly (~25–30%; NS) in Fpr2−/− mice. Also notable was the reduced efficacy of dexamethasone in the Fpr2−/− mice at a dose that significantly reduced Gr1+ cell infiltrate into inflamed WT pouches (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4. AnxA1 and other Fpr2 ligands in the air-pouch and zymosan peritonitis model.

A, AnxA1 (given −10 min) or dexamethasone (0.5 mg/kg, given −1 h) were administered i.v. prior to IL-1β (20 ng) injection into 6-d-old air pouches in WT (closed bars) and Fpr2−/− mice (open bars). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, significant differences between treated and untreated WT values. There was no significant difference between the values for Fpr2−/− mice with any treatment (ANOVA). B, AnxA1 (1 mg, given −10 min) was administered i.v. prior to zymosan (1 mg, i.p.) injection. Gr1+ cell influx into the air pouch or peritoneal cavity was quantified at the 4 h time point by cell counting and flow cytometry. C, Fpr2 ligands were given i.v. at the doses shown (nanomoles) with data being reported as percentage of inhibition compared with vehicle-treated mice. The IL-1β response was similar in WT and Fpr2−/− mice (~3 × 106 cells per pouch). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; compared with respective control values (original numbers) by Student t test. In all of the cases, data are mean ± SEM of 6–12 mice per group.

The involvement of Fpr2 in the antimigratory properties of hrAnxA1 was not restricted to dorsal air pouches; when PMN trafficking was elicited by i.p. zymosan, hrAnxA1 (1 mg i.v.) significantly inhibited Gr1+ cell content in 4 h peritoneal fluids (38 ± 9% reduction versus cell recruitment in the vehicle group, n = 6, p < 0.05; Fig. 4B) but was inactive in Fpr2−/− mice (−5 ± 12%, n = 6, NS; Fig. 4B). The expression of fpr and anxa1 mRNA was similar in both WT and Fpr2−/− peritoneal cells, under resting or acute inflammatory conditions (data not shown).

We tested a number of structurally disparate FPR2/ALX ligands in the mouse air-pouch system following i.v. administration. Fig. 4C reports this data with doses presented in molar terms to facilitate quantitative comparison (the effects measured with hrAnxA1 are shown for comparative purposes). Peptide Ac2–26 dose-dependently inhibited (30–50%) Gr1+ cell recruitment promoted by IL-1β, an effect absent in Fpr2−/− mice. At anti-inflammatory doses (15, 32), LXA4 and Cpd43 produced 50–75% inhibition of cell recruitment (n = 6, p < 0.01 in both cases) in WT mice but were ineffective in Fpr2−/− animals. Intriguingly, SAA provoked a marked increase in the number of cells recruited by IL-1β (1.5-fold over control values of 3.0 ± 0.4 × 106 per cavity); again this effect was mediated through Fpr2 because the Fpr2−/− mice did not share this response (Fig. 4C).

Physiological role of Fpr2 in inflammation

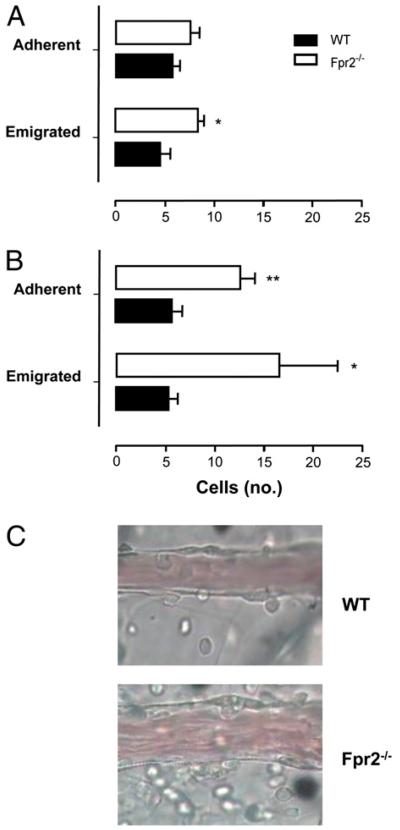

Because we did not observe differences in the leukocyte trafficking responses upon stimulation with IL-1β or zymosan between genotypes, we compared the mouse colonies applying either protocol shown to be sensitive to Fpr2 agonists AnxA1 and LXA4 (28, 34) or more complex models of inflammation. An ischemia–reperfusion insult provoked interaction between circulating leukocytes and postcapillary venules of the mesenteric vascular bed, quantified both at 45 and 90 min postreperfusion (Fig 5A, 5B). Deletion of Fpr2 caused a discrete alteration in these responses, with a significant increase above WT values only for the degree of cell emigration (Fig. 5A). In contrast, longer reperfusion times unveiled an important protective function for Fpr2, because a marked increase (p < 0.01) in adherent and emigrated cells was measured in Fpr2−/− mice (Fig. 5B). Representative images depicting these vascular differences at 90 min postreperfusion are shown in Fig. 5C.

FIGURE 5. Mesenteric ischemia–reperfusion injury of WT and Fpr2−/− mice.

A and B, Mesenteric circulation was subjected to 30 min ischemia followed by (A) 45 or (B) 90 min perfusion. C, A representative field analyzed following 90 min perfusion. WT and Fpr2−/− mice, spanning 100 μm in length and surrounding 50 μm of tissue either side of the vessel wall. Data are mean ± SEM of three fields per mouse of n = 5 mice per group. **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; compared with WT by Student t test.

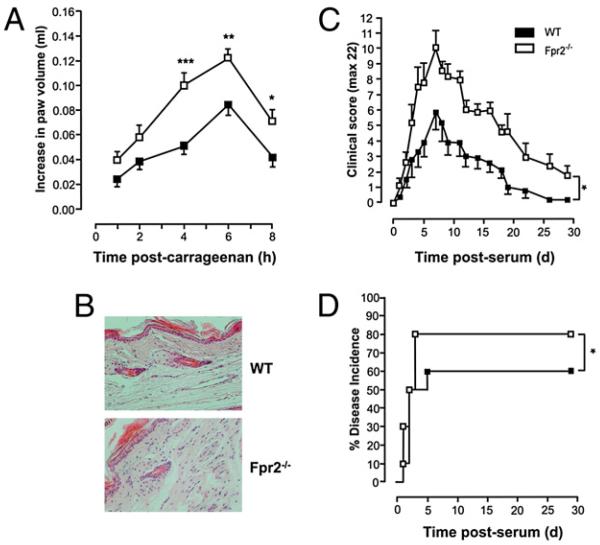

The enhanced acute inflammatory phenotype of the Fpr2−/− mouse emerged further using the carrageenan-induced paw edema model. There was a significant increase in paw swelling in Fpr2−/− mice compared with that in WT animals, significant as early as 4 h after carrageenan administration (~2.5-fold increase) and stable at peak response (8 h time point; +60% in Fpr2−/− mice) (Fig. 6A). Histological analyses of paws collected at the 4 h time point revealed larger numbers of infiltrating leukocytes in the dorsal areas of the paws (Fig. 6B) in the Fpr2−/− mice.

FIGURE 6. Carrageenan-induced paw edema and passive serum-induced arthritis: exacerbation in Fpr2−/− mice.

Mice paws were injected with 50 μl 1% carrageenan solution. A, Time course of the paw swelling in WT and Fpr2−/− mice. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of n = 15 animals. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Student t test. B, Histological analysis in dorsal section of paws at 4 h time point. Mice received 200 μl i.p. of arthrogenic K/B × N serum. C, Time course of the clinical arthritic score in WTand Fpr2−/− mice. Data are mean ± SEM of n = 6 mice. *p < 0.05; two-way ANOVA. D, Percentage disease incidence (cut-off score ≥3). *p < 0.05; log-rank test.

Administration of K/B × N serum provokes a rapid arthrogenic response mediated by cells of the innate immune system (35). Though reaching a maximum at day 7 in both strains, we noted a striking exacerbation and prolongation of the disease in Fpr2−/− mice (Fig. 6C, 6D, respectively), such that symptoms were still evident at day 18, when the response had subsided in WT mice (Fig. 6C). To our knowledge, this is the first data highlighting the tonic inhibitory action mediated through Fpr2 in a model of chronic pathology. A marked upregulation of fpr2 gene expression (as well as fpr and anxa1) was detected in the inflamed joints during the course of the arthritic response (data not shown).

Discussion

We have generated a new colony of mice in which the gene for Fpr2 has been deleted and have used this model to investigate the pathophysiology and pharmacology of this receptor in both cell-based assays and complex models in vivo. In the mouse, the fpr gene cluster (on chromosome 17) has undergone differential expansion, and at least eight genes have been identified (12, 20). Two of these do not appear to be expressed, and another is seen only in the skeletal muscle. Three genes (fpr1, fpr2, and fpr-rs3) are expressed in leukocytes, spleen, and lung.

To confirm that deletion of the fpr2 gene was responsible for the transcription of the functional equivalent of human FPR2/ALX, we conducted radioligand binding assays using [125I]WKYMVm. The absence of binding in Fpr2−/− Mϕs even at high concentrations reflected the specificity of our transgenic technique and revealed a lack of functional compensation by Fpr1 binding.

The absence of Fpr2 had little observable effect on the phenotype under naive conditions. Healthy litters were produced with the expected Mendelian ratio, and mice grew normally with no apparent adverse effects, spontaneous infections, or weight gain. The assessment of generic Ag markers and proportions of circulating immune cells were unaffected, with observations matching those made in the Fpr1−/− colony (31).

The results of the chemotaxis assays present significant parallels with a previous study assessing the migration of transfected HEK-293/Fpr2 toward these ligands (36). This profile is in line with the actions of fMLP at its low-affinity receptor (21). Our data furthermore indicate an exclusive role of Fpr2 in SAA-induced locomotion of human and mouse PMNs and monocytes (13, 22). Because Ac2–26 markedly inhibited SAA-mediated chemotaxis, although unable to induce Mϕ locomotion by itself, these data provide the first hint that murine Fpr2 can integrate two counter-regulatory pathways.

To validate the ligand specificity of this GPCR, we used phosphorylation of ERK (37), a well-established signaling pathway associated with the FPR family (12). W-peptide, a synthetic hexapeptide with a good degree of specificity for Fpr2, induced a concentration-dependent response that was absent in Fpr2−/− Mϕs, supporting the validity of our transgenic strategy. Furthermore, a selective nonpeptidic FPR2/ALX agonist with anti-inflammatory effects, Cpd43 (32), promoted an ERK response in Mϕs that was also dependent on Fpr2. Altogether, these data suggest the homology between the human and the mouse receptors translates into functional similarities. Interestingly, the ERK response to SAA was not diminished in Fpr2−/− Mϕs, a finding in line with the notion that this protein activates multiple receptors and that FPR2/ALX is not solely responsible for intracellular phospho-ERK generation (13, 38, 39). Collectively, these experiments indicate that we have generated a viable mouse colony deficient in Fpr2 (the orthologue of human FPR2/ALX) and that initial characterizations, at the cellular level, were congruent with the current understanding of the biology of the agonists used (20). Furthermore, because peptide Ac2–26- and Cpd43-induced phospho-ERK responses in Mϕs evidently rely upon Fpr2, we could test confidently the impact that fpr2 deletion had on experimental inflammation.

PMN recruitment is a hallmark of the inflammatory response (1, 40). It is exquisitely susceptible to inhibition by endogenous anti-inflammatory pathways (41), including the FPR2/ALX agonists LXA4 (8) and AnxA1 (9). To investigate the role of Fpr2 in orchestrating acute-phase inflammation, a number of Fpr2 ligands were assessed for their abilities to control leukocyte recruitment triggered by IL-1β as an example of a receptor-independent stimulus.

AnxA1 is established as a potent endogenous anti-inflammatory protein mediating a number of antimigratory and proresolving actions in vitro and in vivo (10). The antimigratory action of hrAnxA1 was attenuated largely in Fpr2−/− mice, suggesting that its influence on PMN recruitment depends largely upon Fpr2. This finding is in line with the fact that a high proportion of the anti-migratory action of hrAnxA1 is retained in fpr1−/− mice (42). Dexamethasone, which releases AnxA1 from PMNs within minutes (9), was ineffective in Fpr2−/− mice. Whereas it is clear that the anti-inflammatory properties of glucocorticoids result from multiple molecular and cellular mechanisms (43), a functional link with AnxA1 is confirmed by their reduced efficacy in AnxA1-deficient mice (e.g., Refs. 7, 44). Glucocorticoids can upregulate FPR2/ALX gene and protein expression in human cells (45) and in experimental dermatitis (46). A similar phenomenon also is seen in the case of FPR (47). These intriguing results beg the question of the role of this GPCR in the overall anti-inflammatory and multiple cellular effects of glucocorticoids (43). More experiments are required to elucidate these initial observations, though it is likely that Fpr2 (or FPR2/ALX in human) upregulation by glucocorticoids may mediate a permissive action in the context of inflammatory resolution (5). Furthermore, the diversity of reports on FPR2/ALX versus FPR gene induction might also indicate that distinct glucocorticoids produce different, cell-specific outcomes and gene expression profiles (47).

With the air-pouch model, novel results were seen when multiple Fpr2 ligands were tested. For instance, Cpd43, peptide Ac2–26, and LXA4 all reduced PMN migration selectively in WT mice but not in Fpr2 null animals. To the contrary, SAA increased PMN recruitment, an effect again absent in Fpr2−/− mice. This is the first demonstration that a single GPCR can mediate opposing effects of SAA and other ligands in vivo, a feature reported in some in vitro systems (e.g., Refs. 13, 48). Furthermore, whereas the biology of SAA is complex and its receptors uncertain (49), our study indicates conclusively that stimulation of cell locomotion by SAA in vitro and in vivo requires Fpr2. Finally, from these data, it is also clear that this receptor, and most likely its human counterpart FPR2/ALX, is an ideal model for testing ligand-biased responses and, possibly, ligand-specific receptor homo- or heterodimerization (50). In this respect, it is interesting to note that human FPR2/ALX can form heterodimers with the leukotriene B4 receptor, at least in artificial cell systems (51).

In the last part of the study, we investigated the pathophysiological roles of Fpr2, noting that in the acute models of cell recruitment to specific cavities no differences emerged between WT and Fpr2−/− mice. Because both AnxA1 and LXA4 exert exquisite effects in the inflamed microcirculation, with particular efficacy against ischemia–reperfusion insults (inflammation from within) (34, 52, 53), we compared responses postreperfusion in the mesenteric microcirculation. A protective role for Fpr2 was evident, and it followed a time-dependent profile, so that much higher degrees of cell adhesion and emigration could be measured at 90 min postreperfusion. These observations have the implicit caveats that Fpr2 agonists must be present or produced in this early phase of vascular inflammation. Indeed, we propose endogenous AnxA1 to be externalized on the cell surfaces of adherent PMNs (54), promoting detachment (28, 55). Furthermore, concentrations of LXA4 in localized tissue have been shown to be rapidly enhanced following ischemia–reperfusion injury (56). Finally, it should be noted that augmented degrees of cell adhesion and emigration also have been reported in microvascular beds of AnxA1−/− mice (7, 57) but not in Fpr1−/− animals (58), making a strong functional parallel between two elements (ligand and receptor) of the AnxA1 pathway (9).

The same thinking underlies the experiments of paw edema, a model where AnxA1−/− mice displayed higher inflammatory responses (44). Fpr2−/− mice had a much more rapid, and higher, edema responses in the paw compared with those of WT controls, and this was associated with a marked influx of blood-borne leukocytes in its dorsal tissues. It is unclear why these differences in cell influx were evident in this model and not in IL-1β–induced air-pouch or zymosan peritonitis assays; it is likely that in these cavities other processes may take place, including cell efflux or cell death (10), which is not reflected by the paw inflammation model, where a strong inflammatory response is localized in a discrete tissue site. Furthermore, it cannot be excluded that the different stimulus may have an impact, with the response to carrageenan being mediated, for instance, by a variety of processes, steps, or mediators (59). However, this explanation could be acceptable for IL-1β and carrageenan, because they are very different stimuli (with the cytokine promoting selective leukocyte recruitment without overt inflammatory responses), but not for zymosan and carrageenan, because both stimuli are nonsoluble and nonspecific. Further studies would be required to explain these apparent discrepancies.

The anti-inflammatory nature of Fpr2, evident in the carrageenan paw edema model, emerged more strongly in a longer-lasting model of inflammation caused by the K/B × N serum. Injection of this serum promotes a rapid arthritic response lasting up to 28 d (depending on the volume injected). The etiology of the disease relies mainly upon PMN, Mf, and mast cell activation (35, 60). Greater acute inflammation and a prolongation of inflammatory arthritis were observed in Fpr2−/− mice, with a higher penetrance of severe symptoms, corroborating the overall anti-inflammatory role of this GPCR. The K/B × N serum arthritis model already has been used to extend mechanistic observations generated with models of acute inflammation to settings modeling inflammatory arthritis (29, 61) and proved ideal for determining the potential anti-inflammatory functions of Fpr2. We would propose a model whereby, in the absence of the tonic inhibitory influence of Fpr2 (likely to be induced by AnxA1 and LXA4), greater activation of joint Mϕs and mast cells, will lead to a more pronounced accumulation of PMNs, leading ultimately to the more pronounced and prolonged arthritic response observed in Fpr2−/− mice. Not many studies have applied this model to other elements of this endogenous anti-inflammatory pathway, one exception being the recent study by Krönke et al. (62). These authors have applied this model to mice deficient for both 12- and 15-lipoxygenase, enzymes required for the synthesis of LXA4, observing exacerbated inflammatory arthritis associated with lower joint levels of this anti-inflammatory lipid.

In conclusion, we describe for the first time, the functions of Fpr2 in experimental models of inflammation. Not only does this receptor transduce inhibitory signals from endogenous effectors of anti-inflammation (AnxA1 and LXA4) as well as new chemical entities such as Cpd43, but it also regulates other aspects of the host inflammatory reaction including leukocyte interaction with postcapillary venules, tissue edema, and joint arthritis. Our data point to the existence of subtle, yet reproducible, modulatory loops centered on Fpr2 and its ligands and provide a compelling rationale for developing novel anti-inflammatory therapeutics based upon on agonists of Fpr2 and its human counterpart FPR2/ALX (32, 63).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust (Grants 086867/Z/08 and 069234/Z/02) and a studentship from the Research Advisory Board of Barts and the London and the Medical Research Council. This work forms part of the research themes contributing to the translational research portfolio of Barts and the London Cardiovascular Biomedical Research Unit, which is supported and funded by the National Institutes of Health Research.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- Ac2–26

peptide Ac2–26 of annexin A1

- ALX

lipoxin A4 receptor

- AnxA1

annexin A1

- Cpd43

compound 43

- fMLP

formyl-Met-Leu-Phe

- Fpr

formyl-peptide receptor

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- hrAnxA1

human recombinant annexin A1

- LXA4

lipoxin A4

- Mϕ

macrophage

- PMN

polymorphonuclear leukocyte

- SAA

serum amyloid protein A

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Nathan C. Points of control in inflammation. Nature. 2002;420:846–852. doi: 10.1038/nature01320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serhan CN, Savill J. Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:1191–1197. doi: 10.1038/ni1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luster AD, Alon R, von Andrian UH. Immune cell migration in inflammation: present and future therapeutic targets. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:1182–1190. doi: 10.1038/ni1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serhan CN. Resolution phase of inflammation: novel endogenous anti-inflammatory and proresolving lipid mediators and pathways. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2007;25:101–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serhan CN, Brain SD, Buckley CD, Gilroy DW, Haslett C, O’Neill LA, Perretti M, Rossi AG, Wallace JL. Resolution of inflammation: state of the art, definitions and terms. FASEB J. 2007;21:325–332. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7227rev. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bannenberg GL, Chiang N, Ariel A, Arita M, Tjonahen E, Gotlinger KH, Hong S, Serhan CN. Molecular circuits of resolution: formation and actions of resolvins and protectins. J. Immunol. 2005;174:4345–4355. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damazo AS, Yona S, Flower RJ, Perretti M, Oliani SM. Spatial and temporal profiles for anti-inflammatory gene expression in leukocytes during a resolving model of peritonitis. J. Immunol. 2006;176:4410–4418. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiang N, Serhan CN, Dahlén SE, Drazen JM, Hay DW, Rovati GE, Shimizu T, Yokomizo T, Brink C. The lipoxin receptor ALX: potent ligand-specific and stereoselective actions in vivo. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006;58:463–487. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perretti M, D’Acquisto F. Annexin A1 and glucocorticoids as effectors of the resolution of inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:62–70. doi: 10.1038/nri2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwab JM, Chiang N, Arita M, Serhan CN. Resolvin E1 and protectin D1 activate inflammation-resolution programmes. Nature. 2007;447:869–874. doi: 10.1038/nature05877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perretti M, Chiang N, La M, Fierro IM, Marullo S, Getting SJ, Solito E, Serhan CN. Endogenous lipid- and peptide-derived anti-inflammatory pathways generated with glucocorticoid and aspirin treatment activate the lipoxin A4 receptor. Nat. Med. 2002;8:1296–1302. doi: 10.1038/nm786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ye RD, Boulay F, Wang JM, Dahlgren C, Gerard C, Parmentier M, Serhan CN, Murphy PM. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIII. Nomenclature for the formyl peptide receptor (FPR) family. Pharmacol. Rev. 2009;61:119–161. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He R, Sang H, Ye RD. Serum amyloid A induces IL-8 secretion through a G protein-coupled receptor, FPRL1/LXA4R. Blood. 2003;101:1572–1581. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babbin BA, Lee WY, Parkos CA, Winfree LM, Akyildiz A, Perretti M, Nusrat A. Annexin I regulates SKCO-15 cell invasion by signaling through formyl peptide receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:19588–19599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiang N, Fierro IM, Gronert K, Serhan CN. Activation of lipoxin A(4) receptors by aspirin-triggered lipoxins and select peptides evokes ligand-specific responses in inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:1197–1208. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ying G, Iribarren P, Zhou Y, Gong W, Zhang N, Yu ZX, Le Y, Cui Y, Wang JM. Humanin, a newly identified neuroprotective factor, uses the G protein-coupled formylpeptide receptor-like-1 as a functional receptor. J. Immunol. 2004;172:7078–7085. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.7078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Y, Gong W, Tiffany HL, Tumanov A, Nedospasov S, Shen W, Dunlop NM, Gao JL, Murphy PM, Oppenheim JJ, Wang JM. Amyloid b42 activates a G-protein-coupled chemoattractant receptor, FPR-like-1. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:RC123. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-j0003.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Resnati M, Pallavicini I, Wang JM, Oppenheim J, Serhan CN, Romano M, Blasi F. The fibrinolytic receptor for urokinase activates the G protein-coupled chemotactic receptor FPRL1/LXA4R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:1359–1364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022652999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Y, Ye RD, Gong W, Li J, Iribarren P, Wang JM. Identification of functional domains in the formyl peptide receptor-like 1 for agonistinduced cell chemotaxis. FEBS J. 2005;272:769–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2004.04514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Y, Murphy PM, Wang JM. Formyl-peptide receptors revisited. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:541–548. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartt JK, Barish G, Murphy PM, Gao JL. N-Formylpeptides induce two distinct concentration optima for mouse neutrophil chemotaxis by differential interaction with two N-formylpeptide receptor (FPR) subtypes. Molecular characterization of FPR2, a second mouse neutrophil FPR. J. Exp. Med. 1999;190:741–747. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.5.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su SB, Gong W, Gao JL, Shen W, Murphy PM, Oppenheim JJ, Wang JM. A seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor, FPRL1, mediates the chemotactic activity of serum amyloid A for human phagocytic cells. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:395–402. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaughn MW, Proske RJ, Haviland DL. Identification, cloning, and functional characterization of a murine lipoxin A4 receptor homologue gene. J. Immunol. 2002;169:3363–3369. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayhoe RP, Kamal AM, Solito E, Flower RJ, Cooper D, Perretti M. Annexin 1 and its bioactive peptide inhibit neutrophil-endothelium interactions under flow: indication of distinct receptor involvement. Blood. 2006;107:2123–2130. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perretti M, Flower RJ. Modulation of IL-1-induced neutrophil migration by dexamethasone and lipocortin 1. J. Immunol. 1993;150:992–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perretti M, Solito E, Parente L. Evidence that endogenous interleukin-1 is involved in leukocyte migration in acute experimental inflammation in rats and mice. Agents Actions. 1992;35:71–78. doi: 10.1007/BF01990954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henriques MG, Silva PM, Martins MA, Flores CA, Cunha FQ, Assreuy-Filho J, Cordeiro RS. Mouse paw edema. A new model for inflammation? Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1987;20:243–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gavins FN, Yona S, Kamal AM, Flower RJ, Perretti M. Leukocyte antiadhesive actions of annexin 1: ALXR- and FPR-related anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Blood. 2003;101:4140–4147. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossi AG, Sawatzky DA, Walker A, Ward C, Sheldrake TA, Riley NA, Caldicott A, Martinez-Losa M, Walker TR, Duffin R, et al. Cyclindependent kinase inhibitors enhance the resolution of inflammation by promoting inflammatory cell apoptosis. Nat. Med. 2006;12:1056–1064. doi: 10.1038/nm1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Y, Gong W, Li B, Dunlop NM, Shen W, Su SB, Ye RD, Wang JM. Utilization of two seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptors, formyl peptide receptor-like 1 and formyl peptide receptor, by the synthetic hexapeptide WKYMVm for human phagocyte activation. J. Immunol. 1999;163:6777–6784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao JL, Lee EJ, Murphy PM. Impaired antibacterial host defense in mice lacking the N-formylpeptide receptor. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:657–662. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.4.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bürli RW, Xu H, Zou X, Muller K, Golden J, Frohn M, Adlam M, Plant MH, Wong M, McElvain M, et al. Potent hFPRL1 (ALXR) agonists as potential anti-inflammatory agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:3713–3718. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ernst S, Lange C, Wilbers A, Goebeler V, Gerke V, Rescher U. An annexin 1 N-terminal peptide activates leukocytes by triggering different members of the formyl peptide receptor family. J. Immunol. 2004;172:7669–7676. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scalia R, Gefen J, Petasis NA, Serhan CN, Lefer AM. Lipoxin A4 stable analogs inhibit leukocyte rolling and adherence in the rat mesenteric microvasculature: role of P-selectin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:9967–9972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ji H, Ohmura K, Mahmood U, Lee DM, Hofhuis FM, Boackle SA, Takahashi K, Holers VM, Walport M, Gerard C, et al. Arthritis critically dependent on innate immune system players. Immunity. 2002;16:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liang TS, Wang JM, Murphy PM, Gao JL. Serum amyloid A is a chemotactic agonist at FPR2, a low-affinity N-formylpeptide receptor on mouse neutrophils. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;270:331–335. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gripentrog JM, Miettinen HM. Formyl peptide receptor-mediated ERK1/2 activation occurs through Gi and is not dependent on b-arrestin1/2. Cell. Signal. 2008;20:424–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baranova IN, Vishnyakova TG, Bocharov AV, Kurlander R, Chen Z, Kimelman ML, Remaley AT, Csako G, Thomas F, Eggerman TL, Patterson AP. Serum amyloid A binding to CLA-1 (CD36 and LIMPII analogous-1) mediates serum amyloid A protein-induced activation of ERK1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:8031–8040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405009200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He RL, Zhou J, Hanson CZ, Chen J, Cheng N, Ye RD. Serum amyloid A induces G-CSF expression and neutrophilia via Toll-like receptor 2. Blood. 2009;113:429–437. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-139923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nathan C. Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006;6:173–182. doi: 10.1038/nri1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perretti M. Endogenous mediators that inhibit the leukocyte-endothelium interaction. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1997;18:418–425. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perretti M, Getting SJ, Solito E, Murphy PM, Gao JL. Involvement of the receptor for formylated peptides in the in vivo anti-migratory actions of annexin 1 and its mimetics. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;158:1969–1973. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64667-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clark AR. Anti-inflammatory functions of glucocorticoid-induced genes. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2007;275:79–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hannon R, Croxtall JD, Getting SJ, Roviezzo F, Yona S, Paul-Clark MJ, Gavins FN, Perretti M, Morris JF, Buckingham JC, Flower RJ. Aberrant inflammation and resistance to glucocorticoids in annexin 1−/− mouse. FASEB J. 2003;17:253–255. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0239fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sawmynaden P, Perretti M. Glucocorticoid upregulation of the annexin-A1 receptor in leukocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;349:1351–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hashimoto A, Murakami Y, Kitasato H, Hayashi I, Endo H. Glucocorticoids co-interact with lipoxin A4 via lipoxin A4 receptor (ALX) upregulation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2007;61:81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ehrchen J, Steinmüller L, Barczyk K, Tenbrock K, Nacken W, Eisenacher M, Nordhues U, Sorg C, Sunderkötter C, Roth J. Glucocorticoids induce differentiation of a specifically activated, anti-inflammatory subtype of human monocytes. Blood. 2007;109:1265–1274. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-001115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.El Kebir D, József L, Filep JG. Opposing regulation of neutrophil apoptosis through the formyl peptide receptor-like 1/lipoxin A4 receptor: implications for resolution of inflammation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008;84:600–606. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1107765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shah C, Hari-Dass R, Raynes JG. Serum amyloid A is an innate immune opsonin for Gram-negative bacteria. Blood. 2006;108:1751–1757. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-011932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bosier B, Hermans E. Versatility of GPCR recognition by drugs: from biological implications to therapeutic relevance. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2007;28:438–446. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Damian M, Mary S, Martin A, Pin JP, Banères JL. G protein activation by the leukotriene B4 receptor dimer. Evidence for an absence of trans-activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:21084–21092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710419200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gavins FN, Dalli J, Flower RJ, Granger DN, Perretti M. Activation of the annexin 1 counter-regulatory circuit affords protection in the mouse brain microcirculation. FASEB J. 2007;21:1751–1758. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7842com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chiang N, Gronert K, Clish CB, O’Brien JA, Freeman MW, Serhan CN. Leukotriene B4 receptor transgenic mice reveal novel protective roles for lipoxins and aspirin-triggered lipoxins in reperfusion. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:309–316. doi: 10.1172/JCI7016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perretti M, Croxtall JD, Wheller SK, Goulding NJ, Hannon R, Flower RJ. Mobilizing lipocortin 1 in adherent human leukocytes downregulates their transmigration. Nat. Med. 1996;2:1259–1262. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lim LH, Solito E, Russo-Marie F, Flower RJ, Perretti M. Promoting detachment of neutrophils adherent to murine postcapillary venules to control inflammation: effect of lipocortin 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:14535–14539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Souza DG, Fagundes CT, Amaral FA, Cisalpino D, Sousa LP, Vieira AT, Pinho V, Nicoli JR, Vieira LQ, Fierro IM, Teixeira MM. The required role of endogenously produced lipoxin A4 and annexin-1 for the production of IL-10 and inflammatory hyporesponsiveness in mice. J. Immunol. 2007;179:8533–8543. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chatterjee BE, Yona S, Rosignoli G, Young RE, Nourshargh S, Flower RJ, Perretti M. Annexin 1-deficient neutrophils exhibit enhanced transmigration in vivo and increased responsiveness in vitro. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2005;78:639–646. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0405206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gavins FN, Kamal AM, D’Amico M, Oliani SM, Perretti M. Formyl-peptide receptor is not involved in the protection afforded by annexin 1 in murine acute myocardial infarct. FASEB J. 2005;19:100–102. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2178fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vinegar R, Truax JF, Selph JL, Johnston PR, Venable AL, McKenzie KK. Pathway to carrageenan-induced inflammation in the hind limb of the rat. Fed. Proc. 1987;46:118–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee DM, Friend DS, Gurish MF, Benoist C, Mathis D, Brenner MB. Mast cells: a cellular link between autoantibodies and inflammatory arthritis. Science. 2002;297:1689–1692. doi: 10.1126/science.1073176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gray M, Miles K, Salter D, Gray D, Savill J. Apoptotic cells protect mice from autoimmune inflammation by the induction of regulatory B cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:14080–14085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700326104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krönke G, Katzenbeisser J, Uderhardt S, Zaiss MM, Scholtysek C, Schabbauer G, Zarbock A, Koenders MI, Axmann R, Zwerina J, et al. 12/15-Lipoxygenase counteracts inflammation and tissue damage in arthritis. J. Immunol. 2009;183:3383–3389. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hecht I, Rong J, Sampaio AL, Hermesh C, Rutledge C, Shemesh R, Toporik A, Beiman M, Dassa L, Niv H, et al. A novel peptide agonist of formyl-peptide receptor-like 1 (ALX) displays anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective effects. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009;328:426–434. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.145821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]