Abstract

The Crk adaptor family of proteins comprises the alternatively spliced CrkI and CrkII isoforms, as well as the paralog Crk-like (CrkL) protein, which is encoded by a different gene. Initially thought to be involved in signaling during apoptosis and cell adhesion, this ubiquitously expressed family of proteins is now known to play essential roles in integrating signals from a wide range of stimuli. In this review, we describe the structure and function of the different Crk proteins. We then focus on the emerging roles of Crk adaptors during Enterobacteriaceae pathogenesis, with special emphasis on the important human pathogens Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Throughout, we remark on opportunities for future research into this intriguing family of proteins.

1. Introduction

The product of the oncogene v-Crk was identified in 1988 due to its capacity to transform fibroblasts and to induce tumors in chickens and was named CT10 (chicken tumor virus number 10) regulator of kinase, Crk [1, 2]. The demonstration that the v-Crk protein was able to increase significantly the tyrosine-phosphorylation of proteins in cells without having any intrinsic kinase activity itself was a breakthrough that contributed to the description of the SH2-phosphotyrosine interaction module which functions in cell signaling. Today, the v-Crk cellular homologs (c-Crk) CrkI and CrkII, together with the paralog Crk-like (CrkL) protein, are categorized as adaptor proteins. CrkL was first cloned as a gene implicated in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) [3]. Soon afterward, CrkL was found to be the major phosphoprotein detected in CML cells [4]. The discovery of Crk adaptor proteins represents a milestone in the signal transduction field [5, 6]. These proteins were first implicated in signaling during apoptosis [7] and cell adhesion and migration (reviewed in [8, 9]). Currently, this ubiquitously expressed family of proteins is known to play essential roles in integrating signals from a wide variety of cellular processes, including those more specific to the immune system [10]. In this review, we focus on the emerging roles of Crk adaptors during bacterial pathogenesis.

2. Knockout Mouse Models

CrkI and CrkII are alternatively spliced products from a gene locus located on human chromosome 17p13.3 [11, 12]. CrkL is a paralog encoded by a distinct gene located on human chromosome 22q11.21 [3]. CrkL shares high sequence homology with CrkII, bringing into question whether the two proteins have overlapping functions and the ability to compensate for one another. Unfortunately, the different Crk knockout (K.O.) mouse models have not provided a simple answer to this important question. The first Crk K.O. mouse model was generated by gene trap insertional mutagenesis, resulting in the elimination of CrkII but not of CrkI [13]. These animals developed normally, indicating that CrkI can compensate for the absence of CrkII. Much later, complete ablation of both CrkI and CrkII was achieved and it was observed that most animals died perinatally, mainly due to vascular, cardiac, and craniofacial development defects [14].

There are two different CrkL K.O. mouse models. One was used to develop a transgenic mouse bearing the BCR-ABL fusion gene [15]. Unexpectedly, the CrkL K.O., as well as the transgenic animals, developed leukemia and lymphoma. Furthermore, CrkII was found to be tyrosine phosphorylated and associated with the Bcr-Abl chimeric protein in these cells, suggesting that CrkII replaced CrkL tumorigenic functions. CrkL maps to the 22q11.2 chromosomal region frequently deleted in heterozygosis in humans afflicted with the DiGeorge/velocardiofacial syndrome (now referred to as 22p11DS, Orpha number ORPHA567). The second CrkL K.O. mouse model was developed by the research group of Dr. Akira Imamoto (University of Chicago) and had severe developmental alterations that recapitulated some of the defects typically found in DiGeorge syndrome, such as defects of the cranial and cardiac neural crest derivatives, including a thymus aplasia [16] that causes immunodeficiency [17]. Importantly, MEFs were produced [18] that, much later, allowed investigation into how CrkL contributes to pedestal formation by enteropathogenic E. coli.

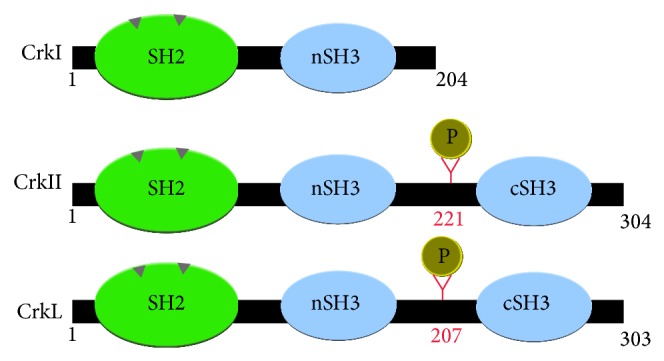

3. Structure

Crk proteins are prototypical adaptors (i.e., absence of enzymatic activity) consisting of Src homology 2 and Src homology 3 (SH2, SH3) domains. They possess one N-terminal SH2 domain, followed by one SH3 domain in the case of CrkI. However, CrkII and CrkL have two SH3 domains named according to whether they are more N- or C-terminally located, nSH3 and cSH3, respectively (Figure 1). The predicted molecular masses are 40 and 36 kDa for CrkII and CrkL, respectively, and 28 kDa for CrkI. They undergo posttranslational modifications as discussed below.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of Crk adaptor protein structure.

4. SH2 Domain

The SH2 domain is an approximately 100 amino acid module with intrinsic folding capacity. Structural studies performed with the Src kinase determined that SH2 domains have two binding surfaces and consequently bind simultaneously to a phosphorylated tyrosine (pTyr) and to motifs containing specific residues located C-terminal to the pTyr (residues +1 to +5). The first pocket contains highly conserved arginine and histidine residues whose mutations abrogate phosphate binding [25]. The second binding surface is more variable and is presumed to confer binding specificity (the specificity pocket; reviewed in [26, 27]). It is generally accepted that the consensus-binding motif for the SH2 domain of Crk proteins is pY-x-x-L/P.

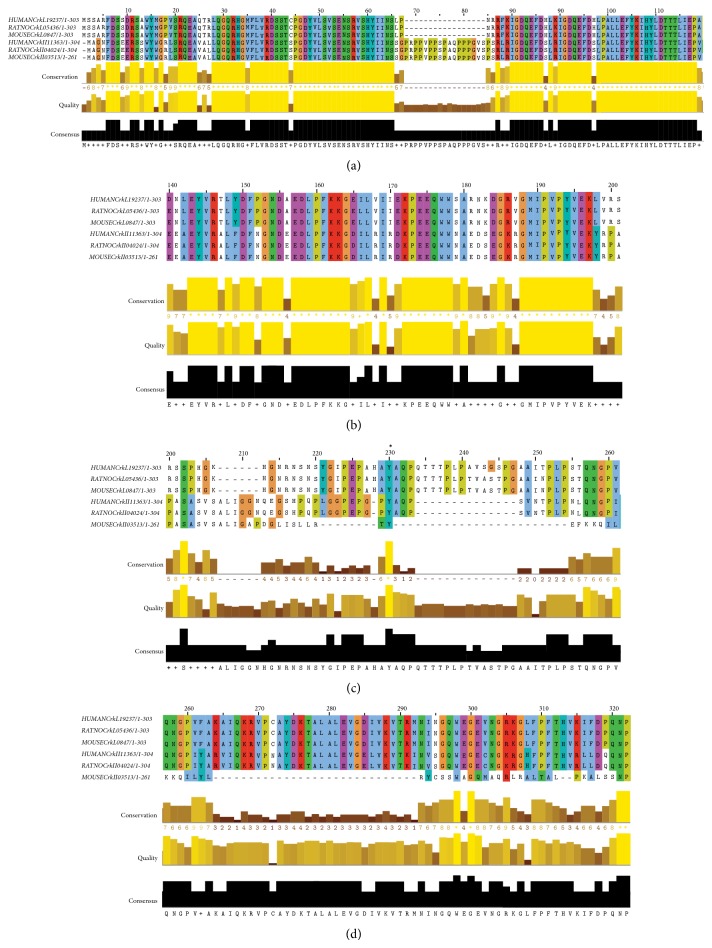

A closer look into the structure of the SH2 domain of CrkI and CrkII shows that, compared with CrkL, they possess an extra stretch of 17 amino acids that contains a proline-rich region (PRR; PPVPPSPAQPPPGVSPS; Figure 2). This SH2-confined PRR has been shown to bind the SH3 domain of Abelson murine leukemia kinase (Abl) [28]. The SH2 domains of CrkII and CrkL share 82% homology. Remarkably, and unlike SH3 domains, SH2 domain containing proteins are apparently missing in prokaryotes [27].

Figure 2.

Crk alignments based on NCBI sequences by using the Clustal Omega program from the European bioinformatics institute (EMBL-EBI) (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). (a) SH2 domains. Note the PRR in CrkII. (b) nSH3 domains. (c) Linker region containing the regulatory tyrosines (indicated by an asterisk). (d) cSH3 domains. Note the low homology of mouse CrkII.

5. SH3 Domain

SH3 domains are globular domains composed of approximately 60 amino acids that bind to PRRs in proteins with a generic PXXP core consensus and additional specificity-determining residues in the proximity, including a positively charged arginine or lysine residue. According to the orientation of the motif, SH3 domains have been classified into class I (+XXPXXP) and class II (PXXPX+) [29]. The nSH3 of CrkII and CrkL share 70% homology. In general, the nSH3 of Crk proteins binds polyproline class II motifs, although there are exceptions, such as the binding of CrkL nSH3 to the downstream of Crk 2 (DOCK2) protein that uses a bipartite motif [30].

CrkII and CrkL each contain a cSH3 defined by its inability to bind to classic polyproline type II (PPII) motifs (reviewed in [31]). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy studies demonstrated that the cSH3 domain adopts the standard SH3 fold encompassing a five-stranded beta barrel; however, its binding surface contains several polar residues (such as glutamine and histidine) which suggests it may not bind typical PXXP ligands or that it may bind them with reduced affinity [32]. Thus, only one interaction has been described so far with the major nuclear export receptor named chromosome maintenance region-1 Crm1/exportin [33]. In fact, the binding site contains a nuclear localization signal (amino acids 256-266 in the human sequence). Therefore, the cSH3 domain allows for the nuclear export of CrkII and CrkL (see the nuclear import/export section).

6. Regulation

The nSH3 and cSH3 domains are bound by an approximately 50-residue-long linker (spacer) region that contains the so-termed regulatory tyrosines, Y221 in CrkII and Y207 in CrkL. It was proposed early on that the phosphorylated Y221 of CrkII could bind to its own SH2 domain [34]. Later, such a mechanism was also demonstrated for CrkL [35] and further confirmed using a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) biosensor ([36]; see below). CrkI regulation must be different because it lacks the regulatory tyrosine, a characteristic that was long ago presumed to be associated with its greater transforming activity [37].

The CrkI and CrkII structure were studied using small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy ([38], commented on in [39]). The authors reported that residues 224–237, which are missing in CrkI, constitute an important regulatory element in CrkII called the inter-SH3 core (ISC). The ISC establishes contacts with the SH2 and SH3 domains to assemble CrkII into a compact structure in which the binding site of SH2 is exposed, but the SH2 domain masks the nSH3 domain. However, the cSH3 domain also contributes to the stability of the structure. It was also proposed that phosphorylation of the regulatory tyrosine not only blocks the SH2 domain, but also hides the binding surface of the nSH3 domain, generating a fully inhibited molecule. By contrast, CrkI has an extended structure in which both SH2 and nSH3 are freely accessible for interactions with target proteins.

cis-trans isomerization of P238 in chicken CrkII mediated by peptidyl-prolyl-cis-trans isomerases (PPIases) was proposed to be another regulatory element. In the cis conformation the nSH3 binding surface would be blocked by P238 and other residues from the cSH3 acting as a “reversible lid” ([40]; reviewed in [41]). However the sequence around the corresponding proline in human CrkII and CrkL (P237) is not well conserved, making the existence of such a regulatory mechanism less probable in human Crk [31]. A recent NMR spectroscopy study ([42]; discussed in [43]) pointed towards a distinct regulation for CrkL (see below).

7. Crk and Abl Kinases: Mutual Regulation

The Abl family of kinases, named after the Abelson murine leukemia virus (v-Abl) oncogene, comprises Abl and Arg (Abl-related gene; also known as Abl2). This family of nonreceptor tyrosine kinases has a modular structure, which includes one SH2 and one SH3 domain. They have a complex regulation and they play essential roles in regulating the actin-cytoskeleton, as indicated by the presence of an actin-binding domain in their C-terminus (reviewed in [44]).

The functional relationships between Crk and Abl are bidirectional (reviewed in [45]). The regulatory tyrosine of Crk adaptors is phosphorylated by the Abl family kinases [35]. The Crk nSH3 domain interacts with PRRs in Abl and induces its transactivation [46], which results in phosphorylation of Crk. In addition, phosphorylation of Y251 within the cSH3 of CrkII promotes a similar Abl transactivation [47].

CML and some adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) patients frequently present the so called Bcr-Abl fusion protein, generated by a reciprocal chromosomal translocation (t(9;22)(q34;q11)) that originates from the “Philadelphia chromosome” [48]. The chimeric protein generated possesses a prominent disease-associated kinase activity that phosphorylates CrkL.

An elegant recent NMR spectroscopy study has uncovered a different global organization for CrkII and CrkL that would explain the predilection of the Bcr-Abl fusion protein for CrkL over CrkII [42, 43]. CrkL forms a constitutive complex with Bcr-Abl. Moreover, binding of phosphorylated Tyr207 (or any other phosphotyrosine) to the SH2 domain has no effect on the nSH3 that is still available to bind Bcr-Abl. In contrast, the association of CrkII with the kinase is repressed in at least two of the four proposed conformational states of the protein.

8. Crk Nuclear Import/Export

Although Crk adaptor proteins can enter the nucleus, the mechanisms governing their nuclear import/export are not well characterized. These proteins seem not to have a cognate nuclear localization signal (NLS); therefore, it is thought that they are imported through their interaction with other proteins that contain an NLS [49]. On the contrary, they have a typical nuclear export signal (NES) located in the cSH3, as previously mentioned. It has been reported that the translocation of CrkII to the nucleus is mediated by the interaction of the nSH3 domain with the cell cycle protein Wee1, DOCK180, or Abl. For example, in the complex formed by WeeI-CrkII, the NES of the latter is masked, keeping Crk in the nucleus, where the complex has pro-apoptotic functions.

CrkL nuclear export is mediated by the interaction with CrmI/exportin [33]. The cSH3 domain of CrkL can exist in monomeric or dimeric conformations in which partial unfolding of the domain exposes the NES [50]. A CrkL and CrmI complex is then formed that can be exported out of the nucleus. It is possible that CrkII shares this mechanism, taking into account the homology (93%) between their cSH3 domains. In addition, type I interferons signal for STAT5 phosphorylation, allowing the interaction with the CrkL SH2 domain [51, 52]. The CrkL-SH2 domain-phospho-STAT5 complex can translocate to the nucleus where it binds to the promoter region of c-Abl or Bcr-Abl in CML cells [52].

9. Crk Signaling Complexes

The current paradigm in the signaling of Crk adaptors is that interactions through the nSH3 are constitutive, while binding to the SH2 domain is primarily inducible. In other words, their SH2 domain senses pathway activation by upstream tyrosine kinases. However, phosphotyrosine signaling is now envisioned as more dynamic [53], with complex formation depending on protein availability, affinity of the implicated domains, post-translational modifications, and other factors.

CrkII itself and some of its key partners are focal adhesion (FA) proteins. FAs are multiprotein complexes containing plasma membrane-associated integrins that link the extracellular matrix and the actin cytoskeleton (reviewed in [54, 55]). Two of the first binding partners described for Crk were the p130 Crk-associated substrate (p130Cas; [56, 57]; reviewed in [58, 59]) and paxillin [60]. p130Cas is an adaptor protein whose tyrosine phosphorylation provides binding sites for the Crk SH2 domain and its association via the nSH3 domain with DOCK180, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) that switches the small GTPase Rac1 to the GTP-bound active state [61].

FA formation and dynamics are challenging subjects to investigate because many different molecular assemblies of proteins are formed that are difficult to dissect. FAs are enriched in kinases, such as focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Src family kinases (SFK). FAK is recruited to the cytoplasmic domain of integrin receptors. In one of the most studied cell adhesion pathways, a FAK-Src complex is formed that promotes paxillin and p130Cas phosphorylation at FAs. The adaptor protein p130Cas contains binding-sites not only for Crk, as mentioned above, but also for FAK, Nck, and Src.

Many proteins found at FAs participate in the formation of other “adhesive structures” such as the so-called “phagocytic cup.” Ig-opsonized pathogens are phagocytosed by professional phagocytes, mainly macrophages and neutrophils, as well as by M cells in the intestine, in a process that requires remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton through the action of the small GTPase Rac. CrkII and DOCK180 were found to accumulate at the phagocytic cup. Using Crk mutants and Crk siRNA, it was proposed that CrkII is required for DOCK180 recruitment, Rac activation, and pathogen engulfment [62]. The possible roles of Crk proteins in several human malignancies have remained elusive because studies have failed to correlate Crk expression levels with cancer progression [63–65]. There are several excellent reviews on the signaling of Crk proteins [9, 66].

10. Crk and Bacterial Invasion

Numerous reports indicate that Crk may contribute to bacterial pathogenesis in a variety of ways, including helping bacteria to enter host cells or serving as “targets of bacterial toxins that disrupt essential cellular functions” [9]. On one side, Crk adaptors have been implicated in lamellipodia and ruffle formation, in part because of their action over FAs [67] and, on the other side, in phagocytosis by immune cells [62]. It makes sense to think that intracellular pathogens would benefit by stimulating their invasion by promoting the first process, while they would benefit by inhibiting the second process to avoid their destruction by phagocytic immune cells. Thus, a common theme in bacterial invasion of nonphagocytic epithelial cells is the induction of ruffles at the site of bacterial attachment. The accumulation of bacteria along with the remodeled cytoskeleton at the site of entrance is very frequently referred as “foci.” This mechanism of entrance is called “the triggering mechanism” [68], in which we will focus with respect to Crk adaptors, as it is employed by various Enterobacteriacea members (e.g., Salmonella and Shigella). On the contrary, Yersinia uses “the zipper mechanism.”

10.1. Salmonella

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium targets intestinal epithelial cells that are normally nonphagocytic. Despite this, Salmonella is able to induce its phagocytic uptake after bacterial attachment to the intestinal epithelium [69]. Invasion is mediated by a type III secretion system (T3SS) that injects bacterial effector proteins directly into the host cytosol [70]. Salmonella T3SS effectors directly target and manipulate host signaling pathways involved in actin filament assembly and cytoskeletal rearrangement leading to bacterial entry [71, 72]. Salmonella invasion utilizes several pathways that converge on Crk: on one side the bacteria manipulate the Fak-p130Cas-Crk axis and on the other side the Abl/Arg-Crk signaling pathway.

To stimulate phagocytic uptake by host cells, Salmonella induces the assembly of FA-like complexes that lack integrins but require the recruitment of FAK and p130Cas [73]. FAK appears to act as a structural scaffold, as its kinase domain is not required. However, its C-terminal proline-rich motif, through which it interacts with p130Cas, is required. In addition, the p130Cas-CrkII interaction appears to be functionally important for Salmonella-induced cytoskeletal rearrangement. Thus, p130Cas−/− cells complemented with p130Cas lacking the Crk-binding domain were impaired for invasion as compared with p130Cas+/+ cells. These data suggest that FAK, p130Cas, and Crk work in concert to regulate Salmonella invasion [73].

Another important strategy used by Salmonella is the manipulation of Abl kinases to promote lamellipodia formation through activation of the WASP family verprolin homologous protein (WAVE) complex [74], also called WAVE regulatory complex (WRC). WAVE proteins are actin-nucleation promoting factors (NPFs) that activate the Arp2/3 complex mainly at sites of lamellipodia formation (reviewed in [75]). Their regulatory mechanism is controversial, but it seems that activation of the WAVE2 complex requires simultaneous interactions with prenylated Rac-GTP and acidic phospholipids, as well as a specific phosphorylation [76, 77].

The role of Abl/Arg kinases and Crk phosphorylation has been studied by Casanova's group [19]. Abl is recruited to the site of bacterial invasion (reviewed in [72]). In MEFs either lacking Abl/Arg, or HeLa and MDCK cells treated with an Abl inhibitor (Imatinib), bacterial invasion efficiency was greatly reduced, as compared with untreated cells. It was proposed that the adaptor protein CrkII associates with Abl during infection, as evidenced by the presence of CrkII at the site of active Salmonella internalization where it colocalized with F-actin. Salmonella infection led to increased phosphorylation of CrkII, while CrkII phosphorylation deficient variants block Salmonella entry. Furthermore, Salmonella infection led to increased phosphorylation of the Abelson-interacting protein (Abi1) [19], a component of the WAVE2 complex. Interestingly, it has been proposed that Crk competes with Abi1 for binding to activated Abl, through interaction of their SH3 domain with the PRR in the kinase [45]. Thus, it is clear that both the Fak-p130Cas-Crk and Abl/Arg-Crk pathways make important contributions to Salmonella invasion. Because these pathways have largely been studied independently of each other, it will be interesting to determine if they are indeed interconnected.

10.2. Shigella

Like Salmonella, Shigella flexneri enters intestinal epithelial cells, which are not inherently phagocytic, and causes bacillary dysentery in humans. Shigella T3SS effectors interact with host proteins to induce dramatic rearrangements of the host actin cytoskeleton to form actin-rich extensions, similar to lamellipodia, which engulf the bacterium [78, 79]. However, in contrast to Salmonella, which replicates and survives inside a special compartment (the Salmonella-containing vacuole), Shigella remains in the cell cytoplasm [80]. Thus, although their invasion shares key components, including Crk, distinct host proteins seem to be used by these pathogens (e.g., cortactin).

Shigella stimulates the tyrosine phosphorylation of some host cell proteins, including Crk adaptors. Abl- and Arg-deficient MEFs have a dramatic decrease in intracellular bacteria after Shigella infection, as compared with WT cells. Similar to Salmonella infection, treating cells with Imatinib (which was developed to inhibit the kinase activity of the BCR-Abl fusion protein in Philadelphia-positive CMLs) reduced Shigella invasion compared with untreated cells, indicating that efficient Shigella infection requires Abl and Arg kinase activity [81]. It was reported that Shigella uptake promotes phosphorylation of Crk, indicating that the Abl-Crk module participates in Shigella invasion of host cells. In addition, a Crk-phosphorylation deficient mutant (CrkII-Y221F) showed a significant decrease in Rac and Cdc42 activation suggesting that the activation of these GTPases is at least in part mediated by Crk phosphorylation [81].

Cortactin, a type II NPF that activates the actin related protein (Arp) 2/3 complex and regulates the neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (N-WASP) activity [82], is recruited to the site of Shigella entry and is tyrosine-phosphorylated in a Src kinase-dependent manner [83]. Bougnères et al. reported that, during Shigella invasion, Src phosphorylates cortactin and then phosphocortactin localizes to the site of Shigella invasion. Furthermore, it was proposed that phosphocortactin association with Crk promotes Shigella entry [84]. Contrary to Shigella, cortactin expression downregulation by RNA interference does not inhibit Salmonella invasion, although the protein is recruited to the sites where the bacteria invade [85].

Unc119 was initially identified as an adaptor protein that activates specific SFK members, such as Lyn [86]. Interestingly, Unc119 blocks Shigella invasion by inhibiting Abl/Arg tyrosine kinases, which results in Crk phosphorylation downregulation [87]. While for Salmonella, the WAVE complex has been well studied, relatively little data are available for Shigella, while the opposite is true for cortactin. Therefore, potential future studies could examine the roles of these respective proteins to determine if they are indeed important to Shigella and Salmonella invasion, respectively.

10.3. Yersinia

Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Y. enterocolitica are enteric pathogens that cause infections which are usually self-limiting, in contrast to Y. pestis, the causative agent of bubonic plague (reviewed in [88]). Yersinia species deliver virulence proteins (Yop effectors) directly into the host cell via the T3SS [89]. Yersinia spp. utilize a β1-integrin-mediated zippering mechanism for bacterial uptake in an actin-dependent process. Uptake is mediated by the interaction between invasin, a bacterial transmembrane protein, and β1-integrins on the host cell surface. The invasin-integrin association initiates a signaling cascade, characterized by tyrosine phosphorylation, leading to activation of the Rho GTPases Rac1 and Cdc42, possibly to promote the activation of N-WASP and the Arp2/3 complex [90] for the formation of actin projections enabling bacterial invasion.

Crk-p130Cas signaling was implicated in Y. pseudotuberculosis uptake [91]. Overexpression of Crk containing mutations (R38V, W169L) to block Crk-SH2 or Crk-SH3 domain binding to target proteins decreased bacterial uptake, indicating that Crk is important for Yersinia invasion of epithelial cells. Furthermore, p130Cas-Crk complex formation was induced in response to infection, which was coupled to Rac1 activation. However, the existence of a Fak-dependent and p130Cas-Crk independent pathway for Yersinia uptake has also been proposed [92].

In contrast to invasin, which binds directly to β1-integrin receptors with high affinity, YadA is a Y. pseudotuberculosis outer membrane adhesin that binds integrins indirectly through the extracellular matrix (ECM). Hudson et al. characterized the mechanisms by which invasin and YadA promote adherence and phagocytic signaling events in macrophages and studied how ECM proteins differentially influence their ability to bind integrins. At low ECM concentrations, invasin binds directly and with high-affinity to β1-integrin to induce integrin clustering and to stimulate integrin-dependent phagocytosis, through FAK-p130Cas-Rac1 signaling. However, at high ECM concentrations, indirect YadA binding to β1-integrin predominates, which also promotes adherence to and entry into host cells [93]. Together, these data suggest that the host cell response to Yersinia infection is likely influenced not only by the expression levels of invasin and YadA during infection, but also by the extracellular environment at the infection site.

It is noteworthy that Crk is implicated in the triggering mechanism for Salmonella and Shigella, and in the zipper mechanism of invasion for Yersinia. This may not be surprising because Crk is implicated in cytoskeletal remodeling via Rac GTPase and possibly WAVE regulation, whereas it is also involved in FA remodeling through integrin signaling.

11. EPEC

Enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EPEC and EHEC, resp.) adhere to intestinal epithelial cells and deliver proteins into the host via the T3SS, resulting in microvilli effacement and intimate attachment to cells, forming the so-called attaching and effacing (A/E) lesions. Because most of the data obtained to date regarding Crk signaling has been from studies of EPEC, rather than EHEC, we will primarily focus on EPEC in this review. It will be interesting in the future to determine to what extent these data are translatable to EHEC.

Among the effector proteins delivered is the translocated intimin receptor (Tir), which is inserted into the host cell plasma membrane where it binds intimin, located on the outer membrane of EPEC [94]. The Tir-intimin interaction activates signaling events that are required for A/E lesion formation. The accumulation of a dense material identified as actin was noticed in early studies. The resulting actin-rich structure is now referred to as a pedestal (reviewed in [95]).

EPEC Tir is phosphorylated on residue Y474 [96] redundantly by Abl/Arg [97] and SFK tyrosine kinases [98], which is essential for actin polymerization and pedestal formation [96]. Besides tyrosine phosphorylation, Tir is phosphorylated on serine residues (S434 and S463). This phosphorylation has been correlated to increases in apparent molecular mass and efficient pedestal formation [99]. It is thought that these shifts in apparent molecular mass indicate changes in Tir structure that enable tyrosine phosphorylation and/or promote Tir insertion into the plasma membrane [99, 100]. Phosphorylated Y474, within the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of Tir, recruits the host cell adaptor proteins non-catalytic tyrosine kinase (Nck) 1 and 2 (collectively referred to as Nck). Nck in turns recruits N-WASP [101], an NPF member of the WAS family of proteins that promote actin polymerization by activating the Arp2/3 complex [102, 103]. N-WASP presents a closed inactive conformation mainly due to intramolecular autoinhibitory interactions that involve the C-terminal acidic domain and the GTPase-binding domain (GBD). N-WASP requires the interaction with other proteins through its GBD or proline-rich domain (PRD) and possibly posttranslational modifications to be fully active [75].

The current paradigm establishes that the major pathway to actin polymerization in typical EPEC infections takes place through phosphorylation of Tir Y474, and subsequent formation of a Tir-Nck-N-WASP complex to promote actin polymerization by the Arp2/3 complex [104]. This proposed signaling pathway has been based mainly on studies using Nck-deficient MEFs, thus their low efficiency in pedestal formation was presumed to reflect a lack of N-WASP activation [101, 105–107]. It is also generally accepted that phosphorylated Tir Y454 promotes a secondary Nck-independent pathway for actin nucleation [107].

However, infection studies with human intestinal tissue using an EPEC Tir Y454F,Y474F variant also lead to actin nucleation and pedestal formation [108]. Likewise, A/E lesion formation and N-WASP recruitment was unaltered when the equivalent Tir variant from Citrobacter rodentium (TirCR Y471 and Y451) was used [109]. These in vitro versus in vivo contradictory results might be explained at least in part by our recent unexpected findings indicating that Nck adaptors possibly have a subsidiary function in activating N-WASP during pedestal formation by EPEC (Nieto-Pelegrin et al, Cell Adhesion and Migration, In press). We found decreased levels of translocated Tir within Nck1/2-deficient MEFs that were corroborated in HeLa cells with down-regulated expression of Nck by siRNA.

12. EPEC Manipulation of Focal Adhesion Proteins

In the early 1960s it was reported that EPEC induces epithelial cell shedding in the intestine [110] which may contribute to diarrhea. This effect was later reproduced in studies with cell lines, including epithelial cells (HeLa, Caco-2) and fibroblasts (DU17; [111]). It was observed that EPEC induces cell detachment from the substratum of the infected host cells mainly by modifying FAs, which were reduced in number and redistributed to the cell periphery. Furthermore, this T3SS dependent-detachment was correlated with FAK dephosphorylation and thus, in FAK−/− fibroblasts, detachment could not be detected [111]. However, the molecular mechanism underlying cell detachment induced by EPEC remained elusive, until it was recently found that the non-LEE-encoded EspC, a serine protease injected by EPEC, is responsible for FAK dephosphorylation and its subsequent degradation, as well as for the degradation of other FA proteins such as paxillin [21].

Related to that, an increase in FAK dephosphorylation by the Shigella late T3SS effector OspE has been reported [112]. OspE interacts with integrin-linked kinase (ILK) and blocks focal adhesion disassembly. ILK is a central adaptor (a pseudokinase) recruited to β1-integrin tails in FAs that mediates the communication between cells and the ECM. Future work will undoubtedly address whether the anticell lifting effect mediated by OspE binding to ILK, demonstrated for Shigella, applies to the OspE orthologs found in EPEC, EHEC, and Salmonella [113, 114]. As for EHEC, the EspO1-2 effectors are homologous to Shigella OspE, and through EspM, seem to regulate RhoA GTPase activity to stabilize FAs [115]. Since Crk adaptors participate in FAs signaling, future studies should aim to address their role in FAs manipulation by these pathogens.

Using immunofluorescence staining, Goosney et al. localized other FA components besides FAK, including p130Cas, vinculin, and CrkII [116]. CrkII localization within pedestals was shown to be dependent on the phosphorylation of Y474 of Tir, although it should be noted that the Y474F variant induces a very limited number of pedestals. In addition, Crk proteins interact with N-WASP via SH3-PRR interactions in smooth muscle cells [117]. However, it still remains unknown whether Crk-N-WASP interaction would activate the latter to promote Arp2/3 complex dependent actin polymerization.

These and other unanswered questions prompted us to investigate the role of Crk adaptors in pedestal formation by EPEC [20]. Unexpectedly, we found that Crk isoforms act as redundant inhibitors of pedestal formation. Thus, Crk expression downregulation by siRNA in HeLa cells or the absence of individual Crk isoforms within CrkI/II or CrkL K.O. MEFs did not alter the number of pedestals formed in infected cells. On the contrary, inhibition of the three Crk isoforms in HeLa cells resulted in a significant increase in pedestal number. Similar results were found in CrkI/II or CrkL K.O. MEFs with knock-down expression by siRNA of the remaining isoform. Moreover, we found that Crk SH2 domain binds Tir through Y474 and competes with the binding of the Nck SH2 domain to Tir, thus inhibiting its recruitment and subsequently, N-WASP activation. In view of our findings, we proposed that Crk adaptors might inhibit actin polymerization at pedestals by competing with Nck activation of N-WASP [20].

13. Do Crk Adaptors Have a Role in Innate Immunity Signaling Manipulation by EPEC?

Several EPEC and EHEC T3SS effectors have been found to inhibit the innate immune response of intestinal epithelial cells by altering the activity of various components of the proinflammatory NF-κB signaling pathway. This is the case for Tir, whose interaction in the cytoplasm with the TNF-alpha receptor-associated factor (TRAF) adaptor proteins induces their degradation by, at the moment, an undefined mechanism [118]. EPEC Tir contains ITIM motifs that interact with SHP-1, a host tyrosine phosphatase, implicated in immune downregulation. Tir binding to SHP-1 was found to promote the association of SHP-1 with TRAF6 and inhibit TRAF6 ubiquitination, thus altering immune signaling [119]. While Tir is known to bind Crk [20], this interaction is not necessarily implicated in the phenotypes described above, and awaits further experimentation.

Several years ago it was discovered that the ribosomal protein S3 (RPS3) interacts with the p65 subunit of NF-κB in the nucleus to increase the affinity of the NF-κB complex for a subset of gene promoters [120]. The non-LEE-encoded effector NleH1 inhibits IκB-kinase-β (IKKβ) phosphorylation of RPS3 S209, preventing RPS3 nuclear translocation [121] and thus reducing NF-κB activity in infected cells [122]. Wan et al. reported that the Ser/Thr kinase activity of NleH1 is essential to inhibit NF-κB activation, yet neither RPS3 nor IKKβ appeared to be the target for NleH1 kinase activity [121]. Using an in vitro kinase array, CrkL was identified as an NleH1 kinase substrate and was also found to interact with IKKβ [22]. Downregulation of CrkL expression using siRNA prevented NleH1 inhibition of NF-κB activity, suggesting that CrkL may act as an adaptor protein, possibly by recruiting NleH1 to the IKKβ-RPS3 complex to prevent RPS3 phosphorylation and subsequently inhibit NF-κB activation [22]. It is currently unknown if this adaptor function in innate immunity applies only to CrkL or might also involve CrkII, as these proteins often have redundant functions. It is also unknown if CrkII/CrkL activities might influence the action of other EPEC/EHEC effectors with anti-inflammatory functions.

14. Crk Adaptors as Possible Targets in the Treatment of Enterobacteriaceae Infections

Fortunately, there is a lot of active research in the area of pharmacological inhibition of Crk, due to the oncogenic role of Bcr-Abl fusion-protein in CML. Microbiologists could exploit much of this work for future research. As mentioned above, the Abl inhibitor imatinib significantly reduced Salmonella and Shigella infection of cells, an observation that appears promising regarding its potential use in animal models. Evolving knowledge on microRNAs (such as miR-126, [123]) could be taken into consideration as a possible way to prevent infection of Salmonella, Shigella, and Yersinia.

On the contrary, according to in vitro studies [97], chemical inhibition of Abl/Arg might be expected to fail in the case of preventing EPEC infection. However, the discrepancies found between the different in vitro and in vivo models, as previously mentioned, will dictate careful reassessment. The subject gets even more complicated because, as discussed above, on one side, CrkII and CrkL block Tir signaling to achieve pedestal formation, which could be explained by the recent finding that Crk adaptors function in a heterocomplex, as reported to occur during podocyte morphogenesis [124]. Therefore, concomitant inhibition of CrkII and CrkL might result in an increase in pedestal formation, which would seem to favor bacterial adhesion. However, individual CrkL expression downregulation was sufficient to block NleH1-mediated inhibition of NF-κB, which could imply a different mechanism of action and a direct role of Crk adaptors in promoting innate immune responses. Clearly, more research is needed to gain further insight into how Crk adaptors participate in the host response to Enterobacteriacea infections.

15. Concluding Remarks

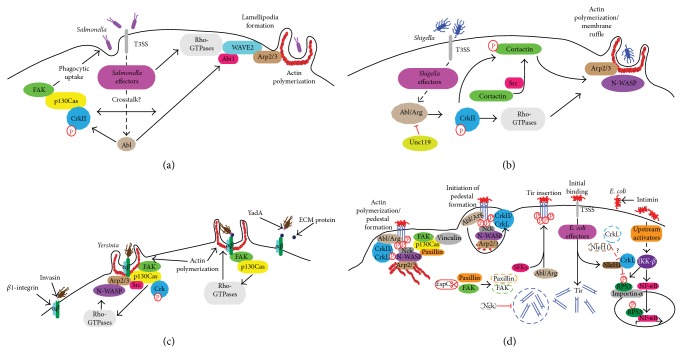

Much has been learned about the role of Crk adaptors in host-pathogen interactions (Figure 3). However many unanswered questions regarding their signaling pathways remain open to investigation, especially with regard to a detailed dissection of the molecular complexes that are formed. In addition, some of the pathways in which Crk adaptors have been implicated are still incomplete and disconnected. There is little doubt that future work should address some challenging matters of pathogen manipulation of cellular signaling. One of those key aspects is the temporal regulation of signaling. The picture gets complicated by the apparent redundancy in effector targets (i.e., the same cellular proteins can be targeted by different bacterial effectors), even more so when these targets are functionally pleiotropic proteins such as Crk adaptors. In our opinion, although Crk adaptors have been traditionally involved in the entrance of pathogens, thanks to recent studies, it seems that they will also be further implicated in innate signaling.

Figure 3.

Roles of Crk proteins in bacterial pathogenesis. (a) Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium manipulates Abl kinase phosphorylation of Crk adaptors to gain entry into the host cell. S. Typhimurium activates Abl kinase via T3SS effectors. Abl phosphorylates CrkII regulatory tyrosines. FAK and p130Cas are recruited to the FA-like complex where p130Cas interacts with CrkII, leading to cytoskeletal rearrangement and uptake of the bacterium. Abl activation by Salmonella effectors may also result in WAVE2 complex activation, in part through phosphorylation of Abi1. The WAVE2 complex is necessary for activation of Arp2/3 to induce actin polymerization at the site of lamellipodia formation. WAVE2 activation also requires interaction with Rho-GTPases (e.g., Rac). Salmonella effectors may also directly activate Rho-GTPases. It is unclear whether crosstalk between the two pathways exists (adapted from [19]). (b) Shigella T3SS effectors activate Abl/Arg to phosphorylate Crk adaptors. Abl/Arg phosphorylates and activates CrkII, which regulates the activity of Rho-GTPases (e.g., Rac and Cdc42). Cortactin is phosphorylated by Src and phosphocortactin interacts with CrkII. Cortactin can contribute to activation of N-WASP and the Arp2/3 complex, resulting in actin polymerization and membrane ruffling. Rho-GTPases can also activate Arp2/3 and N-WASP. On the contrary, Unc119 blocks Abl/Arg phosphorylation of Crk. (c) Yersinia uptake is mediated by β1-integrin signaling to Crk adaptors. The p130Cas-Crk interaction is promoted during Yersinia invasion. FAK and Src are also recruited to this complex. The p130Cas-Crk complex formation is coupled to Rho-GTPase (e.g., Rac) activation, leading to activation of N-WASP, actin polymerization, and bacterial entrance. Alternatively, Yersinia YadA can bind to host cell integrin indirectly through ECM proteins (e.g., fibronectin). This activates a signaling cascade involving FAK, p130Cas and Rho-GTPases, which ultimately lead to actin remodeling and Yersinia uptake. At low ECM concentrations, the invasin-integrin model predominates. At high ECM concentrations, the YadA-ECM-integrin model predominates. Yersinia likely uses a combination of invasin and YadA binding to gain entry into the cell. (d) Crk adaptor proteins are targeted by several EPEC effectors during infection. Tir is inserted into the host cell membrane where binds intimin on the bacterial surface, resulting in intimate attachment of E. coli to the host cell. Abl/Arg and Src family kinases (SFKs) phosphorylate Tir (“Tir insertion”), resulting in the recruitment of Nck. Nck recruits and activates N-WASP leading to Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin polymerization and pedestal formation. Abl/Arg phosphorylates CrII/CrkL (“initiation of pedestal formation”; see [20] for details). Tir levels are reduced in the absence of Nck (dashed circle; Nieto-Pelegrin et al, in press). Other FA components localize to pedestals (e.g., FAK, p130Cas, vinculin, and paxillin; “Actin polymerization/Pedestal formation”), though some are degraded by the EspC effector (dashed lines; [21]). During infection, the transcriptional regulator, NF-κB, becomes activated and translocates to the nucleus. In addition, RPS3 is phosphorylated by IKKβ and translocates to the nucleus via importin-α, where RPS3 acts as a “specifier” for NF-κB to select for and regulate a specific subset of innate immune response genes. The effector NleH1 interacts with CrkL and subsequently prevents the phosphorylation of RPS3, thus blocking RPS3 nuclear translocation and inhibiting NF-κB activation and the innate immune response. In the absence of CrkL (dashed lines), NleH1 cannot block RPS3 translocation to the nucleus. Model partially adapted from [22]. Other translocated effectors include mitochondrial associated protein (Map) and EPEC-secreted proteins (Esp) H, F, G, and Z [23] that are encoded within a pathogenicity island termed the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) [24].

Acknowledgments

The authors apologize to researchers whose studies we were unable to cite due to space limitations. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award number R01AI099002 and by Award number R03CA155868 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAID, NIH, or NCI.

Abbreviations

- Abl:

Abelson murine leukemia kinase

- Arp:

Actin-related protein

- Crk:

CT10 (chicken tumor virus number 10) regulator of kinase

- CrkI/II−/−:

CrkI/II-deficient MEFs

- CrkL−/−:

CrkL-deficient MEFs

- CrkL:

Crk-like

- Dock:

Dedicator of cytokinesis

- EPEC:

Enteropathogenic E. coli

- FA:

Focal adhesion

- F-actin:

Filamentous actin

- FAK:

Focal adhesion kinase

- LEE:

Locus of enterocyte effacement

- MEFs:

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- NCK:

Noncatalytic tyrosine kinases (Nck) 1 and 2

- NF-κB:

Nuclear factor kappaB

- p130Cas:

p130 Crk-associated substrate

- PPIase:

Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase

- PRR:

Proline-rich region

- SH2 and SH3:

Src homology 2 and 3 domain

- Src tyrosine kinase:

Sarcoma tyrosine kinase.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Mayer B. J., Hamaguchi M., Hanafusa H. Characterization of p47(gag-crk), a novel oncogene product with sequence similarity to a putative modulatory domain of protein-tyrosine kinases and phospholipase C. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 1988;53(2):907–914. doi: 10.1101/SQB.1988.053.01.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayer B. J., Hamaguchi M., Hanafusa H. A novel viral oncogene with structural similarity to phospholipase C. Nature. 1988;332(6161):272–275. doi: 10.1038/332272a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ten Hoeve J., Morris C., Heisterkamp N., Groffen J. Isolation and chromosomal localization of CRKL, a human crk-like gene. Oncogene. 1993;8(9):2469–2474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ten Hoeve J., Arlinghaus R. B., Guo J. Q., Heisterkamp N., Groffen J. Tyrosine phosphorylation of CRKL in Philadelphia+ leukemia. Blood. 1994;84(6):1731–1736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buday L. Membrane-targeting of signalling molecules by SH2/SH3 domain-containing adaptor proteins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1999;1422(2):187–204. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4157(99)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pawson T., Scott J. D. Signaling through scaffold, anchoring, and adaptor proteins. Science. 1997;278(5346):2075–2080. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glassman R. H., Hempstead B. L., Staiano-Coico L., Steiner M. G., Hanafusa H., Birge R. B. V-Crk, an effector of the nerve growth factor signaling pathway, delays apoptotic cell death in neurotrophin-deprived PC12 cells. Cell Death and Differentiation. 1997;4(1):82–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeo M. G., Song W. K. v-Crk regulates membrane dynamics and Rac activation. Cell Adhesion & Migration. 2008;2(3):174–176. doi: 10.4161/cam.2.3.6578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birge R. B., Kalodimos C., Inagaki F., Tanaka S. Crk and CrkL adaptor proteins: networks for physiological and pathological signaling. Cell Communication and Signaling. 2009;7, article 13 doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu D. The adaptor protein Crk in immune response. Immunology & Cell Biology. 2014;92(1):80–89. doi: 10.1038/icb.2013.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuda M., Tanaka S., Nagata S., Kojima A., Kurata T., Shibuya M. Two species of human CRK cDNA encode proteins with distinct biological activities. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1992;12(8):3482–3489. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.8.3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fioretos T., Heisterkamp N., Groffen J., Benjes S., Morris C. CRK proto-oncogene maps to human chromosome band 17p13. Oncogene. 1993;8(10):2853–2855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imaizumi T., Araki K., Miura K., Araki M., Suzuki M., Terasaki H., Yamamura K.-I. Mutant mice lacking Crk-II caused by the gene trap insertional mutagenesis: Crk-II is not essential for embryonic development. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1999;266(2):569–574. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park T. J., Boyd K., Curran T. Cardiovascular and craniofacial defects in Crk-null mice. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2006;26(16):6272–6282. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00472-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemmeryckx B., Reichert A., Watanabe M., Kaartinen V., de Jong R., Pattengale P. K., Groffen J., Heisterkamp N. BCR/ABL P190 transgenic mice develop leukemia in the absence of Crkl. Oncogene. 2002;21(20):3225–3231. doi: 10.1038/sj/onc/1205452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guris D. L., Fantes J., Tara D., Druker B. J., Imamoto A. Mice lacking the homologue of the human 22q11.2 gene CRLK phenocopy neurocristopathies of DiGeorge syndrome. Nature Genetics. 2001;27(3):293–298. doi: 10.1038/85855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Herz W., Bousfiha A., Casanova J.-L., et al. Primary immunodeficiency diseases: an update on the classification from the international union of immunological societies expert committee for primary immunodeficiency. Frontiers in Immunology. 2014;5, article 162 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L., Guris D. L., Okura M., Imamoto A. Translocation of CrkL to focal adhesions mediates integrin-induced migration downstream of Src family kinases. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2003;23(8):2883–2892. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.8.2883-2892.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ly K. T., Casanova J. E. Abelson Tyrosine kinase facilitates Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium entry into epithelial cells. Infection and Immunity. 2009;77(1):60–69. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00639-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nieto-Pelegrin E., Meiler E., Martín-Villa J. M., Benito-León M., Martinez-Quiles N. Crk adaptors negatively regulate actin polymerization in pedestals formed by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) by binding to Tir effector. PLoS Pathogens. 2014;10(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004022.e1004022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Navarro-Garcia F., Serapio-Palacios A., Vidal J. E., Isabel Salazar M., Tapia-Pastrana G. EspC promotes epithelial cell detachment by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli via sequential cleavages of a cytoskeletal protein and then focal adhesion proteins. Infection and Immunity. 2014;82(6):2255–2265. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01386-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pham T. H., Gao X., Singh G., Hardwidge P. R. Escherichia coli virulence protein NleH1 interaction with the v-Crk sarcoma virus CT10 oncogene-like protein (CRKL) governs NleH1 inhibition of the ribosomal protein S3 (RPS3)/nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) pathway. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288(48):34567–34574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.512376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong A. R. C., Pearson J. S., Bright M. D., Munera D., Robinson K. S., Lee S. F., Frankel G., Hartland E. L. Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli: even more subversive elements. Molecular Microbiology. 2011;80(6):1420–1438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elliott S. J., Wainwright L. A., McDaniel T. K., Jarvis K. G., Deng Y., Lai L.-C., McNamara B. P., Donnenberg M. S., Kaper J. B. The complete sequence of the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli E2348/69. Molecular Microbiology. 1998;28(1):1–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bibbins K. B., Boeuf H., Varmus H. E. Binding of the Src SH2 domain to phosphopeptides is determined by residues in both the SH2 domain and the phosphopeptides. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1993;13(12):7278–7287. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu B. A., Engelmann B. W., Nash P. D. The language of SH2 domain interactions defines phosphotyrosine-mediated signal transduction. FEBS Letters. 2012;586(17):2597–2605. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu B. A., Nash P. D. Evolution of SH2 domains and phosphotyrosine signalling networks. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2012;367(1602):2556–2573. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anafi M., Rosen M. K., Gish G. D., Kay L. E., Pawson T. A potential SH3 domain-binding site in the Crk SH2 domain. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(35):21365–21374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.35.21365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teyra J., Sidhu S. S., Kim P. M. Elucidation of the binding preferences of peptide recognition modules: SH3 and PDZ domains. FEBS Letters. 2012;586(17):2631–2637. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishihara H., Maeda M., Oda A., Tsuda M., Sawa H., Nagashima K., Tanaka S. DOCK2 associates with CrkL and regulates Rac1 in human leukemia cell lines. Blood. 2002;100(12):3968–3974. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sriram G., Birge R. B. Commentary: the carboxyl-terminal Crk SH3 domain: regulatory strategies and new perspectives. FEBS Letters. 2012;586(17):2615–2618. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muralidharan V., Dutta K., Cho J., Vila-Perello M., Raleigh D. P., Cowburn D., Muir T. W. Solution structure and folding characteristics of the C-terminal SH3 domain of c-Crk-II. Biochemistry. 2006;45(29):8874–8884. doi: 10.1021/bi060590z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith J. J., Richardson D. A., Kopf J., Yoshida M., Hollingsworth R. E., Kornbluth S. Apoptotic regulation by the Crk adapter protein mediated by interactions with Wee1 and Crm1/exportin. Molecular & Cellular Biology. 2002;22(5):1412–1423. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.5.1412-1423.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feller S. M., Ren R., Hanafusa H., Baltimore D. SH2 and SH3 domains as molecular adhesives: the interactions of Crk and Abl. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 1994;19(11):453–458. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Jong R., Ten Hoeve J., Heisterkamp N., Groffen J. Tyrosine 207 in CRKL is the BCR/ABL phosphorylation site. Oncogene. 1997;14(5):507–513. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mizutani T., Kondo T., Darmanin S., Tsuda M., Tanaka S., Tobiume M., Asaka M., Ohba Y. A novel FRET-based biosensor for the measurement of BCR-ABL activity and its response to drugs in living cells. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16(15):3964–3975. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feller S. M., Knudsen B., Hanafusa H. C-Abl kinase regulates the protein binding activity of c-Crk. The EMBO Journal. 1994;13(10):2341–2351. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06518.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobashigawa Y., Sakai M., Naito M., Yokochi M., Kumeta H., Makino Y., Ogura K., Tanaka S., Inagaki F. Structural basis for the transforming activity of human cancer-related signaling adaptor protein CRK. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. 2007;14(6):503–510. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cowburn D. Moving parts: how the adaptor protein CRK is regulated, and regulates. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. 2007;14(6):465–466. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0607-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sarkar P., Saleh T., Tzeng S.-R., Birge R. B., Kalodimos C. G. Structural basis for regulation of the Crk signaling protein by a proline switch. Nature Chemical Biology. 2011;7(1):51–57. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Isakov N. A new twist to adaptor proteins contributes to regulation of lymphocyte cell signaling. Trends in Immunology. 2008;29(8):388–396. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jankowski W., Saleh T., Pai M.-T., Sriram G., Birge R. B., Kalodimos C. G. Domain organization differences explain Bcr-Abl's preference for CrkL over CrkII. Nature Chemical Biology. 2012;8(6):590–596. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kobashigawa Y., Inagaki F. Structural biology: CrkL is not Crk-like. Nature Chemical Biology. 2012;8(6):504–505. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sato M., Maruoka M., Takeya T. Functional mechanisms and roles of adaptor proteins in abl-regulated cytoskeletal actin dynamics. Journal of Signal Transduction. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/414913.414913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hossain S., Dubielecka P. M., Sikorski A. F., Birge R. B., Kotula L. Crk and ABI1: binary molecular switches that regulate abl tyrosine kinase and signaling to the cytoskeleton. Genes and Cancer. 2012;3(5-6):402–413. doi: 10.1177/1947601912460051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shishido T., Akagi T., Chalmers A., Maeda M., Terada T., Georgescu M.-M., Hanafusa H. Crk family adaptor proteins trans-activate c-Abl kinase. Genes to Cells. 2001;6(5):431–440. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sriram G., Reichman C., Tunceroglu A., Kaushal N., Saleh T., MacHida K., Mayer B., Ge Q., Li J., Hornbeck P., Kalodimos C. G., Birge R. B. Phosphorylation of Crk on tyrosine 251 in the RT loop of the SH3C domain promotes Abl kinase transactivation. Oncogene. 2011;30(46):4645–4655. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ben-Neriah Y., Daley G. Q., Mes-Masson A.-M., Witte O. N., Baltimore D. The chronic myelogenous leukemia-specific P210 protein is the product of the bcr/abl hybrid gene. Science. 1986;233(4760):212–214. doi: 10.1126/science.3460176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kar B., Reichman C. T., Singh S., O'Connor J. P., Birge R. B. Proapoptotic function of the nuclear Crk II adaptor protein. Biochemistry. 2007;46(38):10828–10840. doi: 10.1021/bi700537e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harkiolaki M., Gilbert R. J. C., Jones E. ., Feller S. M. The C-terminal SH3 domain of CRKL as a dynamic dimerization module transiently exposing a nuclear export signa. Structure. 2006;14(12):1741–1753. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fish E. N., Uddin S., Korkmaz M., Majchrzak B., Druker B. J., Platanias L. C. Activation of a CrkL-Stat5 signaling complex by type I interferons. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(2):571–573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rhodes J., York R. D., Tara D., Tajinda K., Druker B. J. CrkL functions as a nuclear adaptor and transcriptional activator in Bcr-Abl-expressing cells. Experimental Hematology. 2000;28(3):305–310. doi: 10.1016/S0301-472X(99)00148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mayer B. J. Perspective: dynamics of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling complexes. FEBS Letters. 2012;586(17):2575–2579. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ciobanasu C., Faivre B., Le Clainche C. Integrating actin dynamics, mechanotransduction and integrin activation: the multiple functions of actin binding proteins in focal adhesions. European Journal of Cell Biology. 2013;92(10-11):339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Geiger B., Spatz J. P., Bershadsky A. D. Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2009;10(1):21–33. doi: 10.1038/nrm2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sakai R., Iwamatsu A., Hirano N., Ogawa S., Tanaka T., Nishida J., Yazaki Y., Hirai H. Characterization, partial purification, and peptide sequencing of p130, the main phosphoprotein associated with v-Crk oncoprotein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(52):32740–32746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salgia R., Pisick E., Sattler M., Li J.-L., Uemura N., Wong W.-K., Burky S. A., Hirai H., Chen L. B., Griffin J. D. p130CAS forms a signaling complex with the adapter protein CRKL in hematopoietic cells transformed by the BCR/ABL oncogene. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(41):25198–25203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.di Stefano P. The adaptor proteins p140CAP and p130CAS as molecular hubs in cell migration and invasion of cancer cells. American Journal of Cancer Research. 2011;1(5):663–673. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barrett A., Pellet-Many C., Zachary I. C., Evans I. M., Frankel P. P130Cas: a key signalling node in health and disease. Cellular Signalling. 2013;25(4):766–777. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Birge R. B., Fajardo J. E., Reichman C., Shoelson S. E., Songyang Z., Cantley L. C., Hanafusa H. Identification and characterization of a high-affinity interaction between v-Crk and tyrosine-phosphorylated paxillin in CT10-transformed fibroblasts. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1993;13(8):4648–4656. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kiyokawa E., Hashimoto Y., Kobayashi S., Sugimura H., Kurata T., Matsuda M. Activation of Rac1 by a Crk SH3-binding protein, DOCK180. Genes and Development. 1998;12(21):3331–3336. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee W. L., Cosio G., Ireton K., Grinstein S. Role of CrkII in Fcγ receptor-mediated phagocytosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(15):11135–11143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700823200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sriram G., Birge R. B. Emerging roles for Crk in human cancer. Genes and Cancer. 2011;1(11):1132–1139. doi: 10.1177/1947601910397188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kumar S., Fajardo J. E., Birge R. B., Sriram G. Crk at the quarter century mark: perspectives in signaling and cancer. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2014;115(5):819–825. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bell E. S., Park M. Models of crk adaptor proteins in cancer. Genes and Cancer. 2012;3(5-6):341–352. doi: 10.1177/1947601912459951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Feller S. M. CrK family adaptors-signalling complex formation and biological roles. Oncogene. 2001;20(44):6348–6371. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Antoku S., Mayer B. J. Distinct roles for Crk adaptor isoforms in actin reorganization induced by extracellular signals. Journal of Cell Science. 2009;122(22):4228–4238. doi: 10.1242/jcs.054627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haglund C. M., Welch M. D. Pathogens and polymers: microbe-host interactions illuminate the cytoskeleton. Journal of Cell Biology. 2011;195(1):7–17. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201103148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wagner C., Hensel M. Adhesive mechanisms of salmonella enterica. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2011;715:17–34. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0940-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Galán J. E., Wolf-Watz H. Protein delivery into eukaryotic cells by type III secretion machines. Nature. 2006;444(7119):567–573. doi: 10.1038/nature05272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Patel J. C., Galan J. E. Manipulation of the host actin cytoskeleton by Salmonella—all in the name of entry. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2005;8(1):10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ly K. T., Casanova J. E. Mechanisms of Salmonella entry into host cells. Cellular Microbiology. 2007;9(9):2103–2111. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shi J., Casanova J. E. Invasion of host cells by Salmonella typhimurium requires focal adhesion kinase and p130Cas. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2006;17(11):4698–4708. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shi J., Scita G., Casanova J. E. WAVE2 signaling mediates invasion of polarized epithelial cells by Salmonella typhimurium. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(33):29849–29855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500617200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Burianek L. E., Soderling S. H. Under lock and key: spatiotemporal regulation of WASP family proteins coordinates separate dynamic cellular processes. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2013;24(4):258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lebensohn A. M., Kirschner M. W. Activation of the WAVE complex by coincident signals controls actin assembly. Molecular Cell. 2009;36(3):512–524. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mendoza M. C. Phosphoregulation of the WAVE regulatory complex and signal integration. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2013;24(4):272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Adam T., Arpin M., Prevost M.-C., Gounon P., Sansonetti P. J. Cytoskeletal rearrangements and the functional role of T-plastin during entry of Shigella flexneri into HeLa cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1995;129(2):367–381. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.2.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tran Van Nhieu G., Sansonetti P. J. Mechanism of Shigella entry into epithelial cells. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 1999;2(1):51–55. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Marteyn B. S., Gazi A. D., Sansonetti P. J. Shigella: a model of virulence regulation in vivo. Gut Microbes. 2012;3(2):104–120. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Burton E. A., Plattner R., Pendergast A. M. Abl tyrosine kinases are required for infection by Shigella flexneri . The EMBO Journal. 2003;22(20):5471–5479. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Martinez-Quiles N., Ho H.-Y. H., Kirschner M. W., Ramesh N., Geha R. S. Erk/Src phosphorylation of cortactin acts as a switch on-switch off mechanism that controls its ability to activate N-WASP. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2004;24(12):5269–5280. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5269-5280.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dehio C., Prévost M.-C., Sansonetti P. J. Invasion of epithelial cells by Shigella flexneri induces tyrosine phosphorylation of cortactin by a pp60c-src-mediated signalling pathway. The EMBO Journal. 1995;14(11):2471–2482. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bougnères L., Girardin S. E., Weed S. A., Karginov A. V., Olivo-Marin J.-C., Parsons J. T., Sansonetti P. J., Van Nhieu G. T. Cortactin and Crk cooperate to trigger actin polymerization during Shigella invasion of epithelial cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 2004;166(2):225–235. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200402073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Unsworth K. E., Way M., McNiven M., Machesky L., Holden D. W. Analysis of the mechanisms of Salmonella-induced actin assembly during invasion of host cells and intracellular replication. Cellular Microbiology. 2004;6(11):1041–1055. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cen O., Gorska M. M., Stafford S. J., Sur S., Alam R. Identification of Unc119 as a novel activator of Src-type tyrosine kinases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(10):8837–8845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208261200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vepachedu R., Karim Z., Patel O., Goplen N., Alam R. Unc119 protects from Shigella infection by inhibiting the Abl family kinases. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005211.e5211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Costa T. R. D., Amer A. A. A., Farag S. I., Wolf-Watz H., Fällman M., Fahlgren A., Edgren T., Francis M. S. Type III secretion translocon assemblies that attenuate Yersinia virulence. Cellular Microbiology. 2013;15(7):1088–1110. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dhar M. S., Virdi J. S. Strategies used by Yersinia enterocolitica to evade killing by the host: thinking beyond Yops. Microbes and Infection. 2014;16(2):87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.McGee K., Zettl M., Way M., Fällman M. A role for N-WASP in invasin-promoted internalisation. FEBS Letters. 2001;509(1):59–65. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)03139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Weidow C. L., Black D. S., Bliska J. B., Bouton A. H. CAS/Crk signalling mediates uptake of Yersinia into human epithelial cells. Cellular Microbiology. 2000;2(6):549–560. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bruce-Staskal P. J., Weidow C. L., Gibson J. J., Bouton A. H. Cas, Fak and Pyk2 function in diverse signaling cascades to promote Yersinia uptake. Journal of Cell Science. 2002;115(13):2689–2700. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.13.2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hudson K. J., Bliska J. B., Bouton A. H. Distinct mechanisms of integrin binding by Yersinia pseudotuberculosis adhesins detssermine the phagocytic response of host macrophages. Cellular Microbiology. 2005;7(10):1474–1489. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kenny B., DeVinney R., Stein M., Reinscheid D. J., Frey E. A., Finlay B. B. Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) transfers its receptor for intimate adherence into mammalian cells. Cell. 1997;91(4):511–520. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80437-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lai Y., Rosenshine I., Leong J. M., Frankel G. Intimate host attachment: enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli . Cellular Microbiology. 2013;15(11):1796–1808. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kenny B. Phosphorylation of tyrosine 474 of the enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) Tir receptor molecule is essential for actin nucleating activity and is preceded by additional host modifications. Molecular Microbiology. 1999;31(4):1229–1241. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Swimm A., Bommarius B., Li Y., Cheng D., Reeves P., Sherman M., Veach D., Bornmann W., Kalman D. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli use redundant tyrosine kinases to form actin pedestals. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2004;15(8):3520–3529. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-02-0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Phillips N., Hayward R. D., Koronakis V. Phosphorylation of the enteropathogenic E. coli receptor by the Src-family kinase c-Fyn triggers actin pedestal formation. Nature Cell Biology. 2004;6(7):618–625. doi: 10.1038/ncb1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Warawa J., Kenny B. Phosphoserine modification of the enteropathogenic Escherichia coli Tir molecule is required to trigger conformational changes in Tir and efficient pedestal elongation. Molecular Microbiology. 2001;42(5):1269–1280. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Race P. R., Solovyova A. S., Banfield M. J. Conformation of the EPEC Tir protein in solution: investigating the impact of serine phosphorylation at positions 434/463. Biophysical Journal. 2007;93(2):586–596. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.101766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gruenheid S., DeVinney R., Bladt F., Goosney D., Gelkop S., Gish G. D., Pawson T., Finlay B. B. Enteropathogenic E. coli Tir binds Nck to initiate actin pedestal formation in host cells. Nature Cell Biology. 2001;3(9):856–859. doi: 10.1038/ncb0901-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kalman D., Weiner O. D., Goosney D. L., Sedat J. W., Finlay B. B., Abo A., Bishop J. M. Enteropathogenic E. coli acts through WASP and Arp2/3 complex to form actin pedestals. Nature Cell Biology. 1999;1(6):389–391. doi: 10.1038/14087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lommel S., Benesch S., Rottner K., Franz T., Wehland J., Kühn R. Actin pedestal formation by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and intracellular motility of Shigella flexneri are abolished in N-WASP-defective cells. The EMBO Reports. 2001;2(9):850–857. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Campellone K. G., Leong J. M. Tails of two Tirs: actin pedestal formation by enteropathogenic E. coli and enterohemorrhagic E. coli O157:H7. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2003;6(1):82–90. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(03)00005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Campellone K. G., Giese A., Tipper D. J., Leong J. M. A tyrosine-phosphorylated 12-amino-acid sequence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli Tir binds the host adaptor protein Nck and is required for Nck localization to actin pedestals. Molecular Microbiology. 2002;43(5):1227–1241. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Campellone K. G., Rankin S., Pawson T., Kirschner M. W., Tipper D. J., Leong J. M. Clustering of Nck by a 12-residue Tir phosphopeptide is sufficient to trigger localized actin assembly. Journal of Cell Biology. 2004;164(3):407–416. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200306032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Campellone K. G., Leong J. M. Nck-independent actin assembly is mediated by two phosphorylated tyrosines within enteropathogenic Escherichia coli Tir. Molecular Microbiology. 2005;56(2):416–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Schüller S., Chong Y., Lewin J., Kenny B., Frankel G., Phillips A. D. Tir phosphorylation and Nck/N-WASP recruitment by enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli during ex vivo colonization of human intestinal mucosa is different to cell culture models. Cellular Microbiology. 2007;9(5):1352–1364. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Crepin V. F., Girard F., Schüller S., Phillips A. D., Mousnier A., Frankel G. Dissecting the role of the Tir:Nck and Tir:IRTKS/IRSp53 signalling pathways in vivo. Molecular Microbiology. 2010;75(2):308–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06938.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Staley T. E., Jones E. W., Corley L. D. Attachment and penetration of Escherichia coli into intestinal epithelium of the ileum in newborn pigs. The American Journal of Pathology. 1969;56(3):371–392. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Shifrin Y., Kirschner J., Geiger B., Rosenshine I. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli induces modification of the focal adhesions of infected host cells. Cellular Microbiology. 2002;4(4):235–243. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kim M., Ogawa M., Fujita Y., Yoshikawa Y., Nagai T., Koyama T., Nagai S., Lange A., Fässler R., Sasakawa C. Bacteria hijack integrin-linked kinase to stabilize focal adhesions and block cell detachment. Nature. 2009;459(7246):578–582. doi: 10.1038/nature07952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.van Nhieu G. T., Guignot J. When Shigella tells the cell to hang on. Journal of Molecular Cell Biology. 2009;1(2):64–65. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjp013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Tegtmeyer N., Backert S. Bacterial type III effectors inhibit cell lifting by targeting integrin-linked kinase. Cell Host and Microbe. 2009;5(6):514–516. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Morita-Ishihara T., Miura M., Iyoda S., Izumiya H., Watanabe H., Ohnishi M., Terajima J. EspO1-2 regulates EspM2-mediated RhoA activity to stabilize formation of focal adhesions in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli-infected host cells. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055960.e55960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Goosney D. L., DeVinney R., Finlay B. B. Recruitment of cytoskeletal and signaling proteins to enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli pedestals. Infection and Immunity. 2001;69(5):3315–3322. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3315-3322.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tang D. D., Zhang W., Gunst S. J. The adapter protein CrkII regulates neuronal Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein, actin polymerization, and tension development during contractile stimulation of smooth muscle. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(24):23380–23389. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413390200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ruchaud-Sparagano M.-H., Mühlen S., Dean P., Kenny B. The enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) Tir effector inhibits NF-κB activity by targeting TNFα receptor-associated factors. PLoS Pathogens. 2011;7(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002414.e1002414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yan D., Wang X., Luo L., Cao X., Ge B. Inhibition of TLR signaling by a bacterial protein containing immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs. Nature Immunology. 2012;13(11):1063–1071. doi: 10.1038/ni.2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wan F., Anderson D. E., Barnitz R. A., Snow A., Bidere N., Zheng L., Hegde V., Lam L. T., Staudt L. M., Levens D., Deutsch W. A., Lenardo M. J. Ribosomal protein S3: a KH domain subunit in NF-κB complexes that mediates selective gene regulation. Cell. 2007;131(5):927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wan F., Weaver A., Gao X., Bern M., Hardwidge P. R., Lenardo M. J. IKKβ phosphorylation regulates RPS3 nuclear translocation and NF-κB function during infection with Escherichia coli strain O157:H7. Nature Immunology. 2011;12(4):335–343. doi: 10.1038/ni.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Gao X., Wan F., Mateo K., et al. Bacterial effector binding to ribosomal protein s3 subverts NF-κB function. PLoS Pathogens. 2009;5(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000708.e1000708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ebrahimi F., Gopalan V., Smith R. A., Lam A. K.-Y. MiR-126 in human cancers: clinical roles and current perspectives. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2014;96(1):98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.George B., Fan Q., Dlugos C. P., et al. Crk1/2 and CrkL form a hetero-oligomer and functionally complement each other during podocyte morphogenesis. Kidney International. 2014;85(6):1382–1394. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]