Abstract

During early lung development, airway tubes change shape. Tube length increases more than circumference as a large proportion of lung epithelial cells divide parallel to the airway longitudinal axis. We show that this bias is lost in mutants with increased extracellular signal– regulated kinase 1 (ERK1) and ERK2 activity, revealing a link between the ERK1/2 signaling pathway and the control of mitotic spindle orientation. Using a mathematical model, we demonstrate that change in airway shape can occur as a function of spindle angle distribution determined by ERK1/2 signaling, independent of effects on cell proliferation or cell size and shape. We identify sprouty genes, which encode negative regulators of fibroblast growth factor 10 (FGF10)–mediated RAS-regulated ERK1/2 signaling, as essential for controlling airway shape change during development through an effect on mitotic spindle orientation.

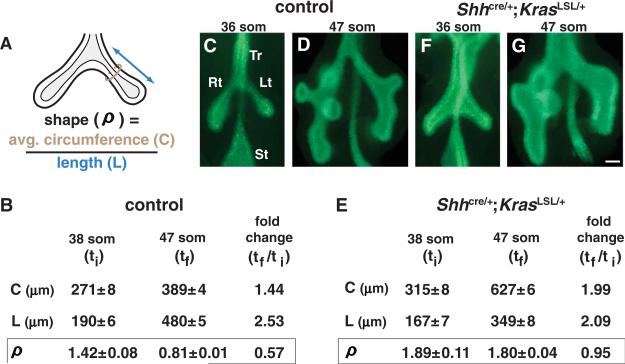

Many organs, including lung, develop from epithelial tubes that branch to form complex networks. Each branch grows to attain the final size and shape characteristic of its position in the network (1). The genetic programs and cellular mechanisms that determine branch architecture in mammalian organs are poorly understood. Here we characterized how airway branch shape, defined as the ratio (ρ) of average tube circumference to length (Fig. 1A), changes during early mouse lung development (2). In the left primary branch, ρ decreased significantly over ~24 hours (Fig. 1, B to D). This change in airway shape (ρ) was not accompanied by alterations in cell size or shape (fig. S1), and the airway epithelium remained a monolayer. These data demonstrate that allo-metric growth (3), in this case a greater increase in length than circumference, is a characteristic of early airway development.

Fig. 1.

Expression of KRASG12D results in a lack of normal airway shape change. (A) Diagram of a lung from a mouse embryo at the 38 somite stage (som) (lumen, light gray) illustrating the parameters measured (average circumference, C, brown circle; length, L, double-headed arrow) to determine airway shape (ρ) (2). (B to D) Shape change in control embryos. (B) Mean values of C, L, and ρ (±SEM) for the left primary branch were determined at an initial time (ti) and a final time (tf). (C and D) Whole-mount E-CAD staining highlights the epithelium. (E to G) Shape change in Shhcre/+;KrasLSL/+ lungs. Lt, left primary branch; Rt, right primary branch; St, stomach; Tr, trachea. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Fibroblast growth factor (FGF)–mediated receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling is required for lung development (4). To determine whether such signaling plays a role in regulating airway shape, we used Cre-mediated recombination to express a mutationally activated form of RAS, a critical effector of RTK signaling, throughout the airway epithelium. We employed Shhcre (5) to recombine a Kras conditional allele, KrasLSL-G12D (6) (hereafter referred to as KrasLSL) (fig. S2A), to obtain expression of KRASG12D, which is predicted to activate signaling by way of RAF→MEK→ERK and other pathways (MEK: mitogen-activated or extracellular signal–regulated protein kinase kinase) (7). In control lungs at the 47 somite stage [som; embryonic day 11.75 (E11.75)], phosphorylated ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) is highly localized (8) (fig. S2B), whereas in Shhcre/+;KrasLSL/+ lungs, pERK1/2 was detected throughout the epithelium (fig. S2C). In the mutant lungs, the normal change in the ratio of airway circumference to length (ρ) did not occur (Fig. 1, E to G), i.e., airway growth was isometric rather than allometric, suggesting that increasing ERK1/2 signaling in lung epithelium prevents the normal airway shape change.

To confirm this hypothesis, we generated Shhcre/+;Braf CA/+ embryos, in which a mutationally activated RAF family member, BRAFV600E (9), is expressed in developing lung epithelium (fig. S3A). BRAFV600E is predicted to increase ERK1/2 but not PI 3-kinase→PDK→AKT signaling (PI 3-kinase: phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PDK: phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase) (10). Shhcre/+;Braf CA/+ lungs displayed the same abnormal shape as Shhcre/+;KrasLSL/+ lungs (compare fig. S3, B and C, to Fig. 1, D and G). Next, we treated Shhcre/+;KrasLSL/+ embryos in utero with PD0325901, a highly specific inhibitor of MEK1/2 (11, 12). Whereas vehicle-treated Shhcre/+;KrasLSL/+ embryos displayed the same abnormal airway shape as untreated mutant embryos, lungs from PD0325901-treated Shhcre/+;KrasLSL/+ embryos appeared normal (fig. S4). Together, these data provide compelling evidence that the lack of normal change in airway shape (ρ) in Shhcre/+;KrasLSL/+ lungs is mediated by RAS-regulated RAF→ MEK→ERK signaling.

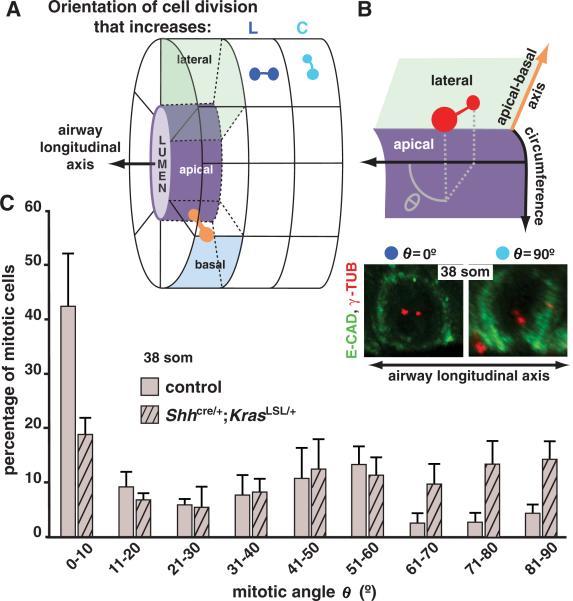

We next investigated what cell-biological processes might be responsible for the mutant airway phenotype. We detected no increase in epithelial cell proliferation in Shhcre/+;KrasLSL/+ lungs (fig. S8A), consistent with previous reports (13), and observed little or no epithelial cell death in Shhcre/+;KrasLSL/+ or control lungs. Moreover, epithelial cell size and shape were similar in mutant and control lungs at 38 or 47 som (fig. S1). Furthermore, no effects were detected on apical-basal polarity or on primary cilia or airway smooth muscle formation. We then assayed for effects on mitotic spindle orientation because it can influence tube shape (14–16) (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Mitotic spindle angle distribution is abnormal in Shhcre/+;KrasLSL/+ lungs. (A) Diagram representing an airway with mitotic spindles (two dots connected by a line) shown in three orientations: in the plane of the epithelium, parallel (dark blue) or perpendicular (lighter blue) to the airway longitudinal axis, and parallel to the apical-basalaxis(orange). (B) (Top) Diagram illustrates how mitotic spindle angle θ, the projection angle of the mitotic spindle onto the plane of the epithelium, is determined with respect to airway longitudinal axis. (Bottom) Maximum intensity confocal projections of ECAD–stained lungs showing cells in which the mitotic spindle poles are labeled with antibody against γ tubulin (red) and spindle angle θ equals 0° or 90°. (C) Bar graph showing the mean distribution of mitotic spindle angles θ (±SD) in left primary branch epithelial cells at 38 som.

Mitotic spindle orientation in dividing airway epithelial cells can be deconstructed into two component angles, determined with respect to tube longitudinal axis (θ; Fig. 2B) and the apical-basal axis of the epithelium (φ; fig. S5). In control left primary airways at 38 som, spindle angle θ distribution was highly nonuniform and skewed toward low angles: In 42% of mitotic cells, the spindle was essentially parallel to the airway longitudinal axis (θ = 0° to 10°), whereas in 58% spindle orientation distribution over the remaining angular range (θ = 11° to 90°) was not different from uniform (P = 0.27; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). However, in Shhcre/+;KrasLSL/+ lungs the bias toward low angles was lost, and spindle orientation distribution across the entire angular range (0° to 90°) was not different from uniform (P = 0.32, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; Fig. 2C). In contrast, spindle angle φ distribution was not affected by KRASG12D expression (P = 0.11; fig. S5). Moreover, these component angles can be independently controlled: In individual mitotic cells in control lungs, there was no correlation between the values of θ and φ (r = –0.13; P = 0.1, two-tailed t test).

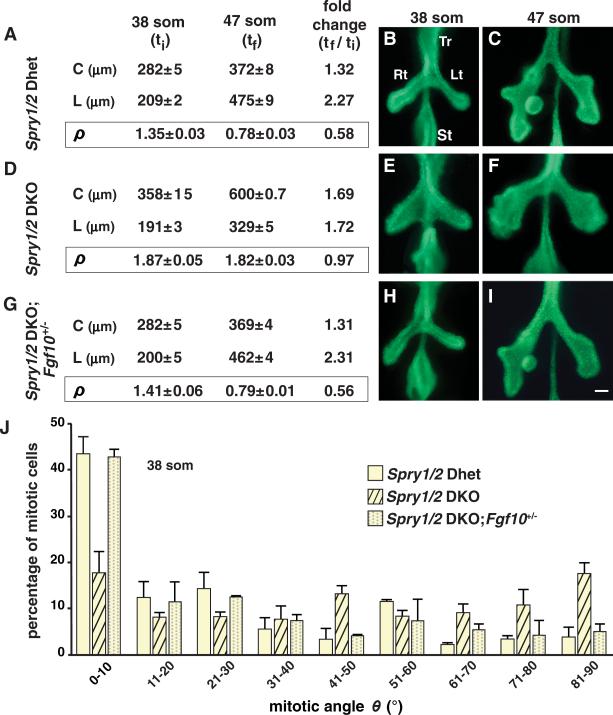

Together, our data underscore the importance of regulating ERK1/2 signaling during airway development and suggest that genes encoding endogenous regulators of ERK1/2 signaling are required for normal airway shape change and mitotic spindle angle distribution. Because members of the sprouty family negatively regulate ERK1/2 signaling (17–20), and Spry1 and Spry2 RNAs are detected in lung epithelium from at least 38 som (fig. S6, A and B), we tested the effect of sprouty loss-of-function (LOF). In Spry1 and Spry2 double-knockout (Spry1/2 DKO) embryos, but not in their double-heterozygous (Spry1/2 Dhet) littermates, we observed both an expansion of the ERK1/2 activation domain (compare fig. S6, C and D, with fig. S2, B and C) and a lack of the normal change in airway shape (ρ) between 38 and 47 som (Fig. 3, A to F), similar to the effect observed when ERK1/2 activity was increased following KRASG12D expression (Fig. 1, B to G). Moreover, spindle angle distribution was altered in Spry1/2 DKO lungs in the same manner as in Shhcre/+;KrasLSL/+ lungs, with a loss of bias toward low angles; the distribution of spindle orientations across the entire angular range (0° to 90°) was not different from uniform (P = 0.28 for Spry1/2 DKO lungs; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; Fig. 3J). Furthermore, airway shape change and mitotic spindle angle distribution were normal when Spry1/2 DKO embryos were treated with MEK1/2 inhibitor PD0325901 (fig. S7).

Fig. 3.

Loss of Spry1 and Spry2 function results in abnormal mitotic spindle angle distribution and a lack of normal airway shape change. (A to C) Shape change in Spry1/2 Dhet control lungs. (A) Mean values of L, C, and ρ (±SEM) for the left primary branch were determined at ti and tf. (B and C) Whole-mount E-CAD staining highlights the epithelium. (D to I) Similar analysis of Spry1/2 DKO lungs (D to F) and Spry1/2 DKO lungs with reduced Fgf10 dosage (G to I). (J) The bar graph shows the mean distribution of mitotic spindle angles θ (±SD) in lungs of these three genotypes. There is no significant difference between Spry1/2 Dhet versus Spry1/2 DKO; Fgf10+/– lungs (P = 1.0; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). Abbreviations as in Fig. 1 legend; scale bar, 100 μm.

However, there were differences between the Shhcre/+;KrasLSL/+ and Spry1/2 DKO lungs. In the latter, the percentage of mitotic epithelial cells increased ~twofold (fig. S8A), secondary branching was impaired (Fig. 3, C and F), and infoldings of the epithelium and underlying basement membrane into the airway lumen were observed (fig. S8, B to E). Because increased cell proliferation was observed in Spry1/2 DKO but not Shhcre/+;KrasLSL/+ airways, it is unlikely to cause the lack of normal shape change seen in both, but presumably underlies the abnormal infoldings and suppressed branching observed in Spry1/2 DKO lungs.

Sprouty genes encode negative-feedback antagonists of signaling pathways downstream of FGF receptor (FGFR) and other RTKs (20). We hypothesized that Spry1 and Spry2 LOF removes a brake on signaling via Fgf10 and Fgfr2, genes that are required for lung development (21–25). If so, then reducing FGF10-mediated FGFR2 signaling by reducing Fgf10 or Fgfr2 gene dosage in Spry1/2 DKO embryos might rescue the mutant phenotype. This approach has been used to identify ligand and receptor genes involved in other sprouty LOF phenotypes caused by excess RTK signaling (26–29). When Fgf10 dosage was reduced in Spry1/2 DKO embryos, airway shape, branching, the domain of ERK1/2 phosphorylation, and mitotic spindle angle distribution appeared normal (Fig. 3, G to J, and fig. S6E). Reducing the dosage of Fgfr2 or Fgf9, another FGF gene required for normal lung development (30), did not rescue the Spry1/2 DKO phenotype (fig. S9). These data demonstrate that Spry1 and Spry2 LOF results in an increase in FGF10-mediated ERK1/2 signaling that causes abnormal spindle angle distribution and a lack of normal change in airway shape.

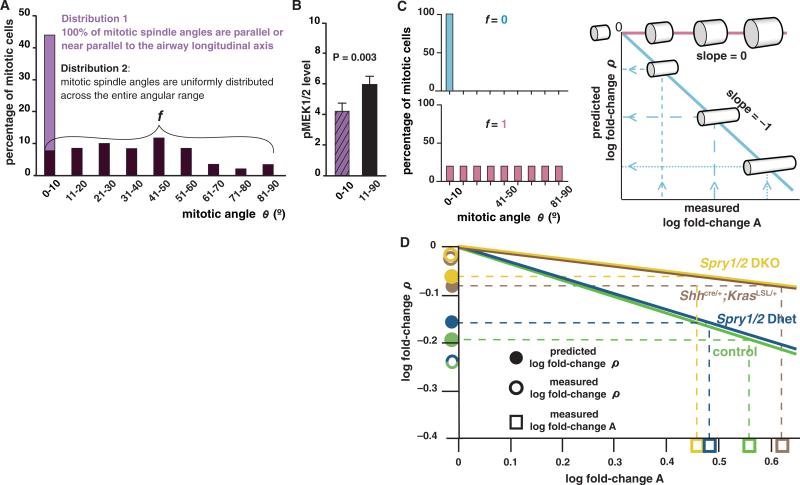

To address whether the distribution of mitotic spindle angles in the epithelium at 38 som (initial time, ti) can account for the changes in airway shape (ρ) observed between 38 and 47 som (final time, tf), we devised a mathematical model to predict epithelial tube shape from spindle angle distribution [see supporting online material (SOM) text I to IV] and tested whether predicted and experimentally measured values were in close agreement. Spindle angle distribution can be described as comprising two underlying distributions and characterized by a single parameter, the fraction (f) of mitotic cells in which spindle angle is uniformly distributed across the angular range (Fig. 4A; SOM text V). f can be estimated with a maximum likelihood approach (SOM text VI). Because the fraction of mitotic cells in which θ = 0° to 10° is lower in the mutant lungs, we assume that ERK1/2 signaling influences f such that its value increases as the proportion of cells with high-level ERK1/2 signaling increases. We tested this assumption by measuring pMEK1/2 level and determining spindle angle θ in individual mitotic cells. pMEK1/2 level was significantly higher in cells in which mitotic spindle angle θ = 11° to 90° than in cells in which θ = 0° to 10° (P = 0.003; one-tailed t test; Fig. 4B), supporting the notion that a high level of ERK1/2 signaling increases the probability that a cell will not divide parallel or near parallel to the airway longitudinal axis.

Fig. 4.

A quantitative model relating spindle angle distribution to airway shape change. (A) The measured spindle angle distribution for mitotic epithelial cells in wild-type left primary branches at 38 som is represented as comprising two distributions. The percentage of mitotic cells with spindle angle θ = 0° to 10° includes cells from both distribution 1 and 2; f is the fraction of cells in distribution 2. (B) Quantification of pMEK1/2 levels (normalized to background; ±SEM) in individual mitotic cells in the population analyzed in (A) gives results consistent with the hypothesis that increasing ERK1/2 signaling increases f. (C) For any value of f (examples in bar graphs, left), the model (see SOM text) can be used to determine the slope of a line relating fold-changes in airway shape (ρ) and in surface area (A) over time on a log-log plot (right). Dashed lines illustrate how such a plot can be used to predict fold-change ρ from measurements of fold-change A between ti and tf. (D) For each genotype shown, the value of f was calculated from spindle angle distribution data at 38 som (Figs. 2C and 3J) and used with the measured value of log fold-change A between 38 and 47 som to determine the predicted value of log fold-change ρ (fig. S10). The agreement between predicted and measured values of fold-change ρ is statistically significant (2).

Our model predicts that there is a scaling relationship between changes over time in epithelial tube shape (ρ, average tube circumference/length) and tube surface area (A, average tube circumference × length) that is determined solely by the value of f. Specifically, a plot of the fold-change in ρ versus fold-change in A on a log-log scale gives a straight line, the slope of which is a function of f (SOM text V). From such a plot, log fold-change ρ (i.e., the log of the ratio of ρ at tf to ρ at ti) can be predicted for any given value of log fold-change A (Fig. 4C). On the basis of the spindle angle distribution for each genotype, we calculated f and used this value to predict fold-change ρ given the measured fold-change A between ti and tf. As expected, the calculated value of f was greater in mutant lungs with increased ERK1/2 signaling than in controls, and the predicted values of fold-change ρ for both mutant and control embryos closely matched the measured values (Fig. 4D and fig. S10). Such agreement suggests that there is no need to invoke effects of ERK1/2 on cellular processes other than spindle orientation to explain the observed shape changes in the primary airway.

To investigate whether a common mechanism controls the change in airway shape in primary and later branch generations during normal lung growth, we examined L.L2, a left lateral secondary branch (31) (fig. S11, A to C). As in the control primary branches, spindle orientation in wild-type L.L2 was strongly biased toward low angles (fig. S11D). Notably, as for the primary branch, the fold-change ρ for L.L2 between ti (55 som) and tf (60 som) predicted on the basis of the observed spindle angle distribution closely matched the measured value (fig. S11E).

Our analysis suggests that cell division in airway epithelium may by default be oriented longitudinally and ERK1/2 activity functions as a switch to override the default orientation, with the level of ERK1/2 activity determining the probability that override will occur. Presumably, ERK1/2 activity does not itself provide any orientation cue but instead determines whether or not a cell responds to such cues. The planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway, which plays an important role in regulating mitotic spindle angle distribution in other tissues (14, 32–34), may provide these cues. However, as yet, there is no evidence that PCP pathway genes function to regulate airway shape or spindle orientation in the lung. Indeed, these parameters were normal in lungs from Vangl2Lp homozygotes (fig. S12).

The mechanism by which ERK1/2 signaling influences spindle orientation remains to be determined. Possibilities include effects on the centrosomal components of the mitotic spindle, on the cytoskeletal elements that control centrosome position and spindle orientation, or on some aspect of cell behavior. Consistent with observations that cell movement in presomitic mesoderm and limb bud is affected by ERK1/2 signaling (35, 36), it is conceivable that high levels of signaling cause mitotic cells to rotate within the epithelium such that spindle angle with respect to the airway longitudinal axis is altered.

The hypothesis that RAS-regulated ERK1/2 signaling influences airway shape change by regulating mitotic spindle angle distribution not only explains the adverse effects on airway shape of increasing ERK1/2 activity, but also posits a role for ERK1/2 signaling in controlling normal airway shape change during development. It is tempting to speculate that such a mechanism also regulates epithelial tube shape changes in other branched organs. Moreover, our data identify sprouty genes as key regulators that function to ensure that the shape changes required for normal development occur.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to J. Licht and J. Zallen for insightful and helpful suggestions; B. Hann for technical advice; K. Thorn (Nikon Imaging Center at UCSF/QB3) for imaging assistance; and D. Hom, P. Ghatpande, C. Firkus, and E. Yu for technical assistance. We also thank members of the Martin, Metzger, and Marshall laboratories and M. Barna, P. Devine, U. Grieshammer, J. Jeong, O. Klein, M. Kumar, S. Luschnig, A. Mogilner, S. Rafelski, and S. Greenberg for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants R01 CA131201 (to M.McM.), R01 GM077004 (to W.F.M), and R01 CA78711 and R01 DE17744 (to G.R.M.). W.F.M. was supported by the W. M. Keck Foundation; R.J.M. was supported by the UCSF Program for Breakthrough Biomedical Research, which is funded in part by the Sandler Foundation; N.T. was supported by an American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship and NIH training grant 5T32HL007185.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

References and Notes

- 1.Weibel ER, Gomez DM. Science. 1962;137:577. doi: 10.1126/science.137.3530.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Information on materials and methods is available on Science Online [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huxley JS, Teissier G. Nature. 1936;137:780. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrisey EE, Hogan BL. Dev. Cell. 2010;18:8. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harfe BD, et al. Cell. 2004;118:517. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson EL, et al. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3243. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young A, et al. Adv. Cancer Res. 2009;102:1. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(09)02001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y, et al. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:897. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dankort D, et al. Genes Dev. 2007;21:379. doi: 10.1101/gad.1516407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Courtois-Cox S, et al. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:459. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohren JF, et al. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:1192. doi: 10.1038/nsmb859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sebolt-Leopold JS, Herrera R. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2004;4:937. doi: 10.1038/nrc1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaw AT, et al. Genes Dev. 2007;21:694. doi: 10.1101/gad.1526207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saburi S, et al. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:1010. doi: 10.1038/ng.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer E, et al. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:21. doi: 10.1038/ng1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kieserman EK, Wallingford JB, Cell Sci J. 2009;122:2481. doi: 10.1242/jcs.042135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hacohen N, Kramer S, Sutherland D, Hiromi Y, Krasnow MA. Cell. 1998;92:253. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80919-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minowada G, et al. Development. 1999;126:4465. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fürthauer M, Reifers F, Brand M, Thisse B, Thisse C. Development. 2001;128:2175. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.12.2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mason JM, Morrison DJ, Basson MA, Licht JD. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:45. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sekine K, et al. Nat. Genet. 1999;21:138. doi: 10.1038/5096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Min H, et al. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3156. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.20.3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Moerlooze L, et al. Development. 2000;127:483. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellusci S, Grindley J, Emoto H, Itoh N, Hogan BL. Development. 1997;124:4867. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.23.4867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cardoso WV, Lü J. Development. 2006;133:1611. doi: 10.1242/dev.02310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shim K, Minowada G, Coling DE, Martin GR. Dev. Cell. 2005;8:553. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein OD, et al. Dev. Cell. 2006;11:181. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein OD, et al. Development. 2008;135:377. doi: 10.1242/dev.015081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basson MA, et al. Dev. Cell. 2005;8:229. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colvin JS, White AC, Pratt SJ, Ornitz DM. Development. 2001;128:2095. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.11.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Metzger RJ, Klein OD, Martin GR, Krasnow MA. Nature. 2008;453:745. doi: 10.1038/nature07005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baena-López LA, Baonza A, García-Bellido A. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1640. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gong Y, Mo C, Fraser SE. Nature. 2004;430:689. doi: 10.1038/nature02796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ciruna B, Jenny A, Lee D, Mlodzik M, Schier AF. Nature. 2006;439:220. doi: 10.1038/nature04375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bénazéraf B, et al. Nature. 2010;466:248. doi: 10.1038/nature09151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gros J, et al. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:1993. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.