Abstract

Objective To determine the rate of early discontinuation and non-publication of randomised controlled trials involving patients undergoing surgery.

Design Cross sectional observational study of registered and published trials.

Setting Randomised controlled trials of interventions in patients undergoing a surgical procedure.

Data sources The ClinicalTrials.gov database was searched for interventional trials registered between January 2008 and December 2009 using the keyword “surgery”. Recruitment status was extracted from the ClinicalTrials.gov database. A systematic search for studies published in peer reviewed journals was performed; if they were not found, results posted on the ClinicalTrials.gov results database were sought. Email queries were sent to trial investigators of discontinued and unpublished completed trials if no reason for the respective status was disclosed.

Main outcome measures Trial discontinuation before completion and non-publication after completion. Logistic regression was used to determine the effect of funding source on publication status, with adjustment for intervention type and trial size.

Results Of 818 registered trials found using the keyword “surgery”, 395 met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 21% (81/395) were discontinued early, most commonly owing to poor recruitment (44%, 36/81). The remaining 314 (79%) trials proceeded to completion, with a publication rate of 66% (208/314) at a median time of 4.9 (interquartile range 4.0-6.0) years from study completion to publication search. A further 6% (20/314) of studies presented results on ClinicalTrials.gov without a corresponding peer reviewed publication. Industry funding did not affect the rate of discontinuation (adjusted odds ratio 0.91, 95% confidence interval 0.54 to 1.55) but was associated with a lower odds of publication for completed trials (0.43, 0.26 to 0.72). Investigators’ email addresses for trials with an uncertain fate were identified for 71.4% (10/14) of discontinued trials and 83% (101/122) of unpublished studies. Only 43% (6/14) and 20% (25/122) replies were received. Email responses for completed trials indicated 11 trials in press, five published studies (four in non-indexed peer reviewed journals), and nine trials remaining unpublished.

Conclusions One in five surgical randomised controlled trials are discontinued early, one in three completed trials remain unpublished, and investigators of unpublished studies are frequently not contactable. This represents a waste of research resources and raises ethical concerns regarding hidden clinical data and futile participation by patients with its attendant risks. To promote future efficiency and transparency, changes are proposed to research governance frameworks to overcome these concerns.

Introduction

Trial discontinuation, non-publication, and non-contactable investigators represent a potential waste of research resources, leading to hidden trial data and ethical concerns for study participants.1 With decreasing health budgets and finite resources, such wastage is unsustainable and strategies to increase efficiency may be required.

In general research populations, high rates of discontinuation and non-publication of randomised controlled trials have been identified as common problems.2 3 4 The extent of this waste in surgery specific studies is unknown. Surgical randomised controlled trials have methodological challenges similar to trials of novel drugs. Additional difficulties can be encountered through introduction of new equipment (including minimally invasive versus open surgery) or material and lack of equipoise when comparing operative and non-operative options, which may lead to greater expense and suboptimal efficiency in trial conduct.5 Interventions including surgical technique, use of technology, and optimal perioperative care require novel strategies for delivery that cannot be controlled with placebo as in conventional drug trials. Such design problems can lead to poor recruitment, futility, and adverse events, which may predispose to waste. Industry funding has previously been suggested as a contributing factor to waste.2 3 4 However, collaboration with industry developers and funders is an important source of surgical innovation,6 which may present a unique dynamic in surgery specific studies.

A greater understanding of the factors leading to waste will guide future allocation of resources and allow funders to foster mutually beneficial relationships with research teams to maximise research capacity. Previous work has included strategies to promote transparency in randomised controlled trials, including trial registration on publicly available databases.7 These resources (for example, ClinicalTrials.gov) provide an open access medium to assess outcomes of trials and to permit assessment of publication bias.8 9 This study aimed to determine the rate of discontinuation and non-publication of surgical randomised controlled trials and the feasibility of contacting trial investigators.

Methods

Objectives and outcome measures

The objective of this study was to determine the rate of discontinuation and non-publication of randomised controlled trials involving patients undergoing surgery. For this study, we defined wastage of resources in three domains, which we subsequently used as the main outcome measures: discontinuation (versus completion); non-publication (versus publication); and feasibility of contacting trial investigators for both discontinued and unpublished studies. Although success of email contact has not been tested as an outcome in this context before, this is a logical way for patients, clinicians, and trialists to obtain information about relevant trials that have been discontinued or remain unpublished.

Data source

ClinicalTrials.gov is a web based registration system and database including more than 174 000 clinical trials.10 The database was launched in 2000 and is maintained and quality controlled by the United States National Library of Medicine. Data are provided by study investigators and sponsors, who are expected to provide updates throughout the trial’s lifecycle. Each record provides information relating to recruitment status, study design, funding, and participants. Records are identifiable by a unique national clinical trial (NCT) number.

Definitions

ClinicalTrals.gov defines registered studies on the basis of current recruitment status11; this formed the basis for definitions and inclusions used in this paper. We included terminated, withdrawn, or suspended studies in the “discontinued” group (see table 1 for complete definitions), with completed studies forming the “completed” group. We excluded trials with status “unknown,” “active, not recruiting,” or “enrolling by invitation.” For the purposes of this study, we defined industry funded trials as any trial receiving commercially sourced funding, including investigator initiated, industry sponsored trials.

Table 1.

ClinicalTrials.gov definitions for recruitment status of randomised trials11

| Recruitment status | Definition |

|---|---|

| Included in this study | |

| Completed | The clinical study has ended normally, and participants are no longer being examined or treated (that is, the “last subject, last visit” has occurred) |

| Suspended | The clinical study has stopped recruiting or enrolling participants early, but it may start again |

| Terminated | The clinical study has stopped recruiting or enrolling participants early and will not start again. Participants are no longer being examined or treated |

| Withdrawn | The clinical study stopped before enrolling its first participant |

| Excluded from this study | |

| Active, not recruiting | The clinical study is ongoing (that is, participants are receiving an intervention or being examined), but potential participants are not currently being recruited or enrolled |

| Enrolling by invitation | A clinical study that selects its participants from a population, or group of people, decided on in advance by the researchers. These studies are not open to everyone who meets the eligibility criteria, but only to people in that particular population, who are specifically invited to participate |

| Unknown | A clinical study in ClinicalTrials.gov with a status of “recruiting,” “not yet recruiting,” or “active, not recruiting” and whose status has not been confirmed within the past two years. Studies with an unknown recruitment status are considered open studies or closed studies, depending on their last recorded recruitment status |

| “Temporarily not available for expanded access” “No longer available for expanded access” “Approved for marketing” | No definition available |

We used two definitions for publication, to represent a spectrum of reporting methods. The primary definition was publication of a complete manuscript in a peer reviewed journal, identified through a systematic search. The secondary definition was availability of results in the ClinicalTrials.gov results database, when no primary publication was found. This was not included in the primary definition, as the principles of peer review, compliance with reporting standards (for example, CONSORT statement), and detailed reporting are not upheld in the ClinicalTrials.gov results database.12 Two authors (SJC and AB) independently classified studies by detailed intervention type (grouped under main headings of non-device operative, device, or pharmacological intervention), with consensus discussion in case of disagreement.

Study inclusion criteria

We queried the ClinicalTrials.gov advanced search facility by using the keyword “surgery” for non-paediatric, phase III-IV clinical trials registered between 1 January 2008 and 31 December 2009, using recruitment status definitions (table 1). The keyword search was a pragmatic decision based on time efficiency and the likelihood that it would identify most relevant studies; no other systematic search term for surgical trials within ClinicalTrials.gov exists. We defined surgery as any procedure involving an incision through an external body surface. We included phase III/IV randomised controlled trials including a preoperative, intra-operative, or postoperative intervention applied to adult patients undergoing a surgical procedure in any surgical specialty. Phase III/IV studies assess effectiveness in large patient groups, and subsequent publication is expected. We excluded phase II studies, as these are typically safety assessments before phase III studies, for which publication is not routinely planned. We excluded studies involving paediatric patients, as we judged that these are likely to have recruitment problems more in keeping with involving children than surgical techniques and warrant separate analysis. We included trials registered between 1 January 2008 and 31 December 2009 with a final confirmed status by 31 December 2011.

Search strategy

We did the ClinicalTrials.gov search on a single day (18 December 2013) to account for daily changes to the database. We screened the title and trial summary of each study to remove non-randomised and duplicated entries (BS and HM, checked by SJC). We then made a detailed evaluation of each record to confirm trial inclusion (BS and HM, checked by AB). In cases of discrepancy, a third author reviewed the record and consensus was achieved by discussion.

Publication search

The time elapsing from the latest possible completion date (31 December 2011) to the time of the search for publication (10 August 2014) allowed a minimum of 31 months for journal submission, peer review, and editorial processes. We initially reviewed each ClinicalTrials.gov record to identify links to relevant publications (BS, checked by SJC). Authors may choose to provide this information by updating the record once the study is published. If no such link was identified, we searched Medline via PubMed by using the following characteristics: NCT number, trial title, author names, institutions, and keywords (BS, checked by SJC). We subsequently searched for publications not identified using PubMed via the Scopus bibliographic database by using a comparable strategy (BS, checked by SJC). Scopus has a wide coverage and encompasses citations listed in both PubMed and Embase. We evaluated matches according to trial design, sample size, dates of recruitment, study hypotheses, and nature of intervention, as described in the ClinicalTrials.gov database. We considered a trial as published if it was catalogued in print or in press. If we found no peer reviewed journal publication, we sought reporting of results within the ClinicalTrials.gov results database.

Contact email search

For discontinued trials without a stated reason on ClinicalTrials.gov and for completed studies with no identified publication, we sought a contact email address. We searched for publications authored by the trial investigator identified on the register by using PubMed and Scopus databases through examination of previous publications by investigator name, location, and field of expertise. We sent a standardised email to seek clarification of the reason for discontinuation or current publication status, with one reminder scheduled two weeks later (BS and HM, checked by SJC). We deemed trial investigators to be non-contactable and considered completed trials to be unpublished if we received no response within the total four weeks. If a contact email address was not found, if no response was received, or if the email address provided was inactive, we did a further Google Scholar and Google search using the trial registration number, investigator name, or both (BS, checked by AB). If these failed and a sponsoring industry name was provided, we requested details through either a company email address or a generic online contact form. We calculated a final response rate by dividing the total number of replies from all sources by the number of trials for which we sought contact.

Statistical analysis

We used the χ2 test to compare differences in trial design variables between groups. We considered differences to be statistically significant if P was less than 0.05. To test for the effect of these variables together on discontinuation and publication status, we used adjusted binary logistic regression. The binary outcome targets were firstly discontinuation (versus completion) and secondly non-publication (versus publication); we used primary publication (in a peer reviewed journal) for this modelling process. Selection of variables used for adjustment of these models and their categorisation was pre-planned, irrespective of statistical significance at the univariable level; we judged these adjustment variables to be key surrogate markers of important differing trial design. The main explanatory variable was funding status (industry versus non-industry), adjusted for intervention type (drug or medical device versus non-drug) and number of patients in the trial (≥100 versus <100 patients). Further variables were not added or tested within models to avoid overlap and over-adjustment in this exploratory analysis. This produced an odds ratio and 95% confidence interval, which if greater than 1.0 indicated a greater likelihood of trial completion or publication and if less than 1.0 indicated lower likelihood. We used SPSS version 21.0 for analysis.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

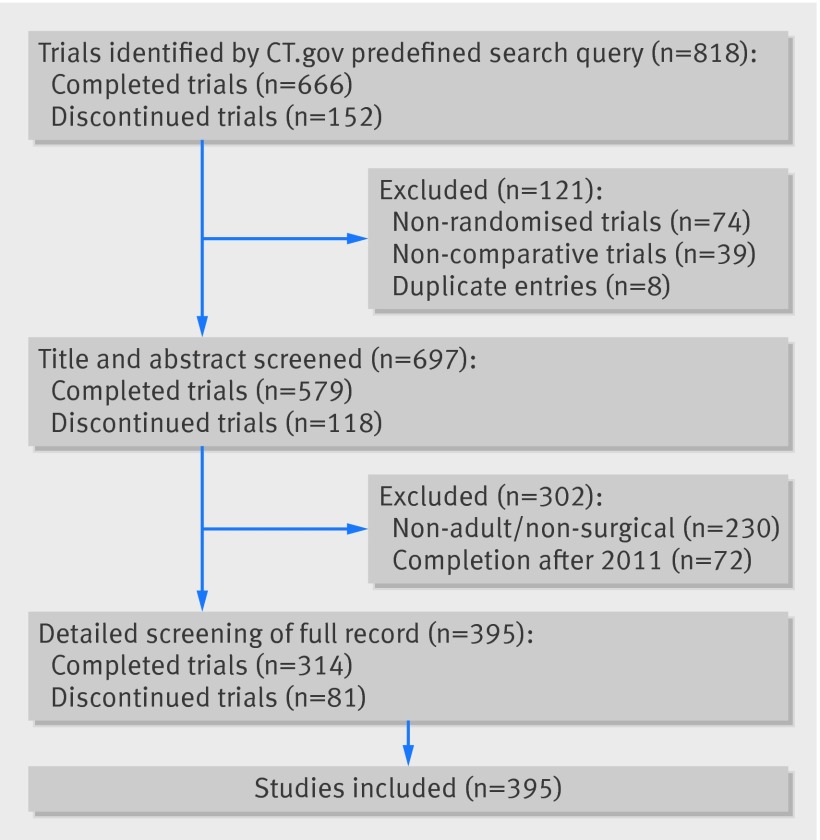

The initial search identified 818 trials, of which 395 were included in the final analysis after exclusions (fig 1). The most frequently represented specialties were gastrointestinal surgery (23%), trauma and orthopaedic surgery (23%), ophthalmology (13%), and cardiothoracic surgery (13%) (table 2). Table 3 shows detailed intervention classes for all included trials. The median number of study participants was 100 (interquartile range 51-205, range 1-6000). The primary site/affiliation of the principle investigator originated from 39 countries across six continents.

Fig 1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria of clinical trials

Table 2.

Surgical specialty of 395 randomised controlled trials included in study

| Surgical specialty | No (%) of trials |

|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal surgery | 92 (23) |

| Trauma and orthopaedics | 91 (23) |

| Ophthalmology | 52 (13) |

| Cardiothoracic surgery | 51 (13) |

| Gynaecology | 30 (8) |

| Urology | 18 (5) |

| Breast surgery | 14 (4) |

| Vascular surgery | 11 (3) |

| Neurosurgery | 10 (3) |

| Otolaryngology | 5 (1) |

| Plastic surgery | 5 (1) |

| Oral and maxillofacial surgery | 4 (1) |

| Other | 12 (3) |

Table 3.

Intervention class of 395 randomised controlled trials included in this study

| Intervention class | No (%) trials |

|---|---|

| 1) Operative intervention; non-device (total): | 42 (11) |

| 1A Operative versus non-operative intervention | 13 (3) |

| 1B Surgical technique (non-device) | 29 (7) |

| 2) Intervention with device (total): | 106 (27) |

| 2A Implantable therapeutic device (permanent) | 44 (11) |

| 2B Non-implantable therapeutic device | 18 (5) |

| 2C Operative (non-therapeutic, temporary, or access) or diagnostic device | 44 (11) |

| 3) Pharmacological interventions (total): | 247 (63) |

| 3A (i) Perioperative analgesics | 75 (19) |

| 3A (ii) Perioperative anti-emetics | 8 (2) |

| 3B Reduction and prevention of infection | 11 (3) |

| 3C Reduction and prevention of haemorrhage | 28 (7) |

| 3D Fluid management | 6 (2) |

| 3E Nutrition | 14 (4) |

| 3F Reduction and prevention of thrombosis | 12 (3) |

| 3G Reduction and prevention of other disease-specific morbidity | 45 (11) |

| 3H Adjuvant therapeutic treatment | 18 (5) |

| 3I Other | 30 (8) |

Discontinuation

Table 4 shows trials’ characteristics according to study completion status. Of 395 clinical trials, 314 (79%) were completed and 81 (21%) were discontinued. This represented 77 008 (83.1%) and 15 626 (16.9%) study participants respectively (calculated from actual or target registration data in ClinicalTrials.gov). Of the discontinued trials, 72 (89%) were terminated, 8 (10%) were withdrawn, and 1 (1%) was suspended. We found no significant differences between completion status for funding type, intervention type, number of participants, or blinding. More discontinued trials were multicentre (36% (112/314) completed v 51% (41/81) discontinued; P=0.034) and international (9% (28/314) v 17% (14/81); P=0.042).

Table 4.

Characteristics of completed and discontinued trials. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Discontinued (n=81) | Completed (n=314) | Total (n=395) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Funding: | ||||

| Non-industry | 47 (21) | 182 (79) | 229 | 0.548 |

| Industry | 34 (20) | 132 (80) | 166 | |

| Intervention: | ||||

| Operative | 12 (29) | 30 (71) | 42 | 0.251 |

| Device | 24 (23) | 82 (77) | 106 | |

| Pharmacological | 45 (18) | 202 (82) | 247 | |

| No of centres: | ||||

| Single centre | 40 (18) | 186 (82) | 226 | 0.034 |

| Multicentre | 41 (27) | 112 (73) | 153 | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 16 (100) | 16 | |

| Sample size: | ||||

| <100 | 39 (21) | 145 (79) | 184 | 0.663 |

| ≥100 | 40 (19) | 166 (81) | 206 | |

| Missing | 2 (40) | 3 (60) | 5 | |

| Recruitment: | ||||

| National | 67 (20) | 273 (80) | 340 | 0.042 |

| International | 14 (33) | 28 (67) | 42 | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 13 (100) | 13 | |

| Blinding: | ||||

| None | 31 (26) | 90 (74) | 121 | 0.149 |

| Single* | 14 (15) | 80 (85) | 94 | |

| Double | 35 (20) | 141 (80) | 176 | |

| Missing | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | 4 |

Percentages total across rows.

*Investigator, assessor, or patient blinding.

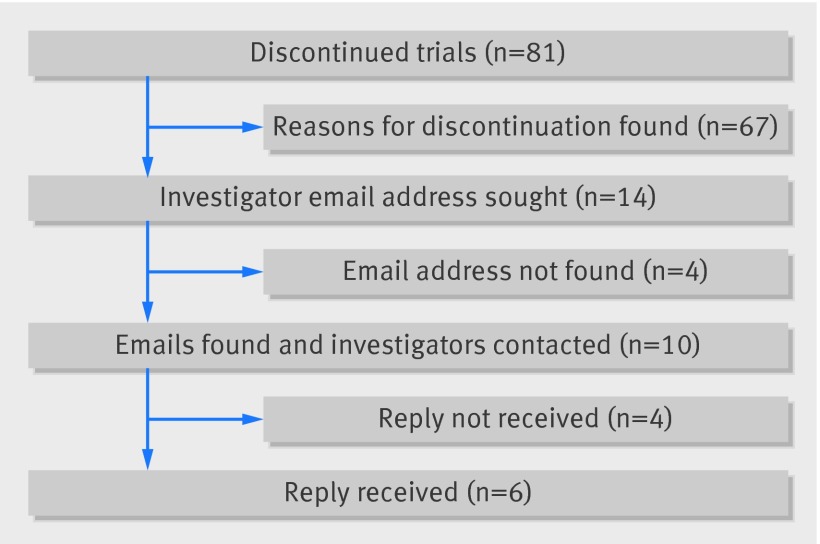

Fourteen (17.3%) discontinued studies did not provide reasons on ClinicalTrials.gov (fig 2). We identified contact email addresses for 71% (10/14) and received replies from 60% (6/10) of queries sent, giving an overall responding email rate of 43% (6/14). Including these responses, the most common reasons for discontinuation were poor recruitment (44%; 36/81), lack of continued funding (10%; 8/81), and termination due to negative results (10%; 8/81) (table 5). Industry funding was not a predictor of discontinuation (adjusted odds ratio 0.91, 95% confidence interval 0.54 to 1.55; P=0.735) (table 6).

Fig 2 Discontinued trials: authors’ email response

Table 5.

Reasons for discontinuation of 81/395 surgical randomised controlled trials

| Reason for non-completion | No (%) |

|---|---|

| Insufficient/poor patient recruitment | 36 (44) |

| Lack of funding to continue trial | 8 (10) |

| Trial terminated early owing to negative results/futility | 8 (10) |

| Withdrawal of trial management or clinical investigators | 7 (9) |

| Trial administration or conduct problems | 4 (5) |

| Trial lost clinical relevance | 4 (5) |

| Trial product/device/drug withdrawn from market | 3 (4) |

| Trial termination based on safety or toxicity data | 2 (2) |

| Trial terminated early owing to positive results | 1 (1) |

| Missing | 8 (10) |

14/81 did not disclose reason for termination on ClinicalTrials.gov; emails were identified and sent to 10/14 authors, with no contact available for remaining 4/14.

Table 6.

Adjusted logistic regression for effect of industry funding on trial discontinuation and publication of completed trials

| Univariable | Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Discontinuation | |||||

| Funding: | |||||

| Non-industry | Reference | Reference | |||

| Industry | 1.00 (0.61 to 1.65) | 0.992 | 0.91 (0.54 to 1.55) | 0.735 | |

| Intervention: | |||||

| Operative | Reference | Reference | |||

| Device | 1.37 (0.61 to 3.07) | 0.449 | 1.29 (0.55 to 3.06) | 0.558 | |

| Pharmacological | 1.80 (0.85 to 3.78) | 0.123 | 1.65 (0.76 to 3.62) | 0.209 | |

| Sample size: | |||||

| <100 patients | Reference | Reference | |||

| ≥100 patients | 1.12 (0.68 to 1.83) | 0.663 | 1.10 (0.66 to 1.84) | 0.704 | |

| Publication | |||||

| Funding: | |||||

| Non-industry | Reference | Reference | |||

| Industry | 0.49 (0.30 to 0.78) | 0.003 | 0.43 (0.26 to 0.72) | 0.001 | |

| Intervention: | |||||

| Operative | Reference | Reference | |||

| Device | 0.70 (0.27 to 1.78) | 0.454 | 0.80 (0.30 to 2.13) | 0.653 | |

| Pharmacological | 0.69 (0.29 to 1.62) | 0.390 | 0.64 (0.34 to 2.07) | 0.700 | |

| Sample size: | |||||

| <100 patients | Reference | Reference | |||

| ≥100 patients | 1.34 (0.84 to 2.14) | 0.226 | 1.71 (1.03 to 2.84) | 0.038 | |

Non-publication of completed studies

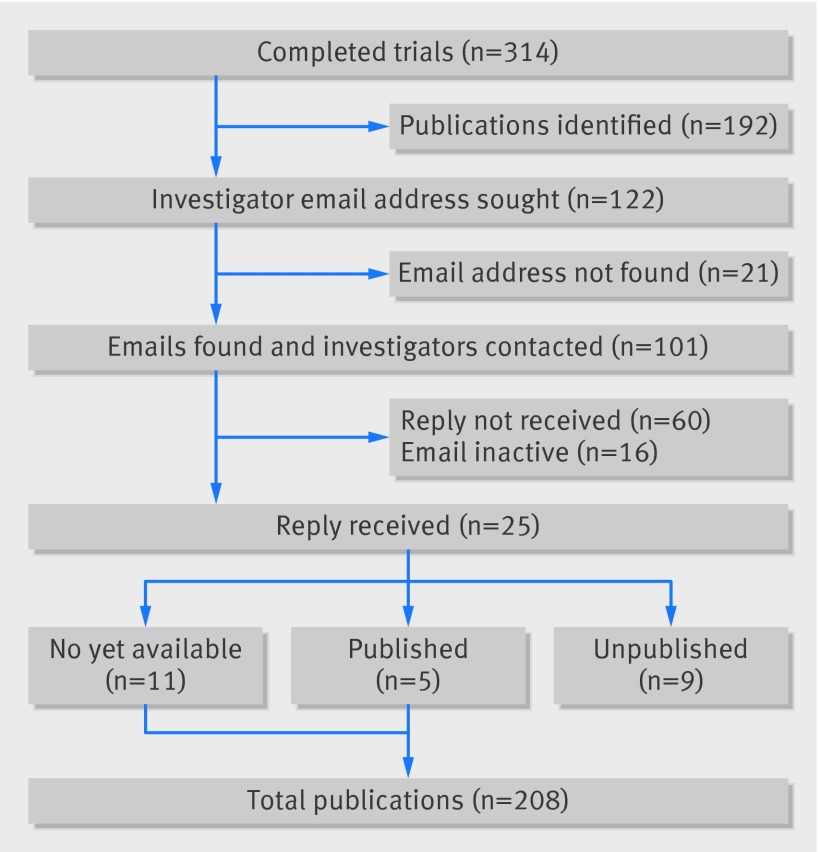

Table 7 shows characteristics of the 314 completed studies, according to publication status. The median time from study completion to publication search date was 4.9 (interquartile range 4.0-6.0, minimum 2.7) years. Of 314 completed trials, we initially identified 192 as published following searches on PubMed and Scopus databases. We sought contact email addresses for the remaining 122 unpublished trials, for which 101 email addresses were identified and contacted, with the remaining 21 email addresses not found (fig 3). Of authors contacted, 25/101 (25%) replies were received, giving an overall responding email rate of 20% (25/122). These replies identified 11 studies in press and five published studies (four in non-indexed peer reviewed journals). We subsequently considered these published, yielding a revised total of 208/314 (66%) published studies in peer reviewed journals. The remaining responses identified a further nine trials as unpublished (table 8). Combining these nine with 21 studies without a contact email address, 60 with no reply to contact, and 16 with an inactive email address generated a total of 106 unpublished trials according to the definition of primary publication (34%; 106/314).

Table 7.

Characteristics of published and unpublished completed trials. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Unpublished (n=106) | Published (n=208) | Total (n=314) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Funding: | ||||

| Non-industry | 49 (27) | 133 (73) | 182 | 0.003 |

| Industry | 57 (43) | 75 (57) | 132 | |

| Intervention: | ||||

| Operative | 8 (27) | 22 (73) | 30 | 0.686 |

| Device | 28 (34) | 54 (66) | 82 | |

| Pharmacological | 70 (35) | 132 (65) | 202 | |

| No of centres: | ||||

| Single centre | 56 (30) | 130 (70) | 186 | 0.398 |

| Multicentre | 39 (35) | 73 (65) | 112 | |

| Missing | 11 (69) | 5 (31) | 16 | |

| Sample size: | ||||

| <100 patients | 54 (37) | 91 (63) | 145 | 0.225 |

| ≥100 patients | 51 (31) | 115 (69) | 166 | |

| Missing | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | 3 | |

| Recruitment: | ||||

| National | 87 (32) | 186 (68) | 273 | 0.678 |

| International | 10 (36) | 18 (64) | 28 | |

| Missing | 9 (69) | 4 (31) | 13 | |

| Blinding: | ||||

| None | 32 (36) | 58 (64) | 90 | 0.234 |

| Single* | 32 (40) | 48 (60) | 80 | |

| Double | 41 (29) | 100 (71) | 141 | |

| Missing | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | 3 |

Percentages total across rows.

*Investigator, assessor, or patient blinding.

Fig 3 Completed trials: identified publications and authors’ email response

Table 8.

Reasons for non-publication received from corresponding authors of 20 completed randomised controlled trials who replied to email information requests*

| Reason for non-publication | No |

|---|---|

| Study in press but not available on PubMed. | 11 |

| Publication efforts abandoned following failed submission(s) | 3 |

| Lack of time, resources, or personnel | 2 |

| Clinician authors decided not to publish owing to negative results | 1 |

| Study terminated early | 1 |

| Study still ongoing | 1 |

| Reason not disclosed by author | 1 |

*Five additional responses disclosed a peer reviewed publication (four in non-PubMed indexed journals), leading to a total of 25 investigators’ responses for completed trials.

Of the 314 completed studies, 69 (22%) had results on the ClinicalTrials.gov results database. A peer reviewed publication was also available for 49 of these; the remaining 20 (6%) studies reported in the online entry only. This means that the rate of non-publication fell to 27% (86/314) when we considered the primary (peer reviewed journal) and secondary (ClinicalTrials.gov results only) publication standards together. Of the 69 studies with results, 66 (96%) had an email contact, two (3%) had a telephone contact only, and one (1%) had no contact details. For 245 studies on ClinicalTrials.gov that were completed without results, no contact details were available on the online entry.

Industry funding was significantly associated with reduced likelihood of publication (adjusted odds ratio 0.43, 0.26 to 0.72; P=0.001), and sample size of 100 or more patients was associated with increased likelihood of publication (1.71, 1.03 to 2.84; P=0.038) (table 6).

Discussion

This study identified a considerable waste of resources in interventional trials related to patients undergoing surgery. One in five surgical randomised controlled trials were discontinued early and one in three completed trials remained unpublished at a median of 4.9 years. Difficulty obtaining information from corresponding research teams compounded these losses. Although not quantified by this study, this wastage is likely to represent a poor use of financial resources for funders, host institutions, and commissioning bodies. In addition, further non-financial and ethical costs include a loss of knowledge through hidden data and patients being placed at potential risk without delivery of accessible research benefits.1 The most common reason for discontinuation was poor recruitment of participants, which is a persistent problem and aligns with previous reports describing this challenge for a wider range of clinical trials.3 Some reasons for early discontinuation may have led to preservation of resources rather than wastage. Carefully considered termination due to positive or negative results, safety data, or clinical developments is likely to save future resources, whereas poor recruitment, trial conduct problems, or withdrawal of management groups represents wasted resources.

Strengths and weaknesses of this study

Problems in trial delivery and scientific design of interventional surgical trials may not be comparable to those of drug trials.5 This study included only surgical specialties on the basis that the surgical community must urgently consider trial design, conduct, and resource allocation. Through inclusion of a broad range of surgical specialties and related intervention types, the relevance to research teams across multiple surgical specialties is wide and generalisable. Conversely, this is also an inherent limitation of the study, as the results do not permit a detailed assessment of exactly where in the research pathway, which surgical specialty, or which intervention should be targeted. It is likely that not all surgical randomised controlled trials were captured by this study, partly because we used a pragmatic search strategy based only on the keyword “surgery”. More importantly, a recent analysis of 10 high impact surgical journals showed that, contrary to guidelines, 34.9% of 246 published randomised controlled trials were not registered on a clinical trials database and would therefore not be identified by our search strategy.7 8 However this finding should not directly affect the rate of non-publication, which is a function of registered trials only. It is also feasible that not all published trials were identified, although if publications were available beyond the comprehensive search strategy used in this study, their lack of visibility presents an additional barrier contributing to resource wastage. Although the study period chosen (2008-09) represents the modern trials era, trials designed in the present day may have overcome some of the wastage problems, although the situation may have also worsened. As this can be explored only after publication status can be reliably assessed, this study represents the most modern knowledge available and is able to influence current trial design.

The relatively short follow-up period used by this study may have contributed to the low publication rate. Although our study represents a modern time period, the earlier time frame used by Kasenda et al (2000-03) allowed for a longer median follow-up of 11.6 (range 8.8-12.6) years, compared with our shorter median period of 4.9 years with a minimum time of 2.7 years.3 A longer period, which accounts for studies with long follow-up times, may have further increased the publication rate in our study. The nature of these delays is unknown and should be subject to future linked research to minimise them when possible. The effect on the relevance of a study’s results, especially when considering introduction of novel surgical technologies and perioperative drugs (which are likely to have short term outcome measures), justifies use of a shorter follow-up period in this study.

This study highlights difficulty in tracing study investigators. Contact details for completed but unpublished studies were unavailable from the ClinicalTrials.gov entry, suggesting systematic removal. A ClinicalTrials.gov record should be considered to have been published in the public domain, and information should not be removed from this at a later date. Additional barriers to contact exist, which may have limited response rates in this study during the search for further information, such as investigators changing surnames, moving institution before study completion, or changing email addresses. Furthermore, the quality of results in the ClnicalTrials.gov entry has not yet been systematically analysed for compliance with reporting guidelines.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies

Rosenthal and colleagues recently reported a 43% discontinuation rate and a 44% non-publication rate from surgical randomised controlled trials registered by six ethics committees in three countries between 2000 and 2003 (Canada, Germany, Switzerland).13 Our large, contemporary analysis supports these findings by using an international trials registration database; Rosenthal reported 127 surgical trials from three countries, compared with 395 trials from 39 countries in six continents in our study. We additionally sought to assess feasibility of contacting trial investigators across this wider geographical landscape, which better represents the position of patients and clinicians seeking results, rather than direct contact from a research ethics committee alone.

Before these, studies assessing non-publication of clinical trials did not analyse surgical studies separately, so their application to surgical trialists was unclear.2 4 14 15 16 17 18 A previous study including 1017 registered randomised controlled trials from a broad specialty base found that poor recruitment was the most frequent reason for discontinuation (9.9%; 101/1017) and that industry sponsors were associated with non-publication (adjusted odds ratio 1.68, 1.20 to 2.34).3 A recent cross sectional analysis of non-publication of large randomised trials from ClinicalTrials.gov included only trials with more than 500 patients from any specialty.2 This study found a 29% (171/585) non-publication rate, which was significantly associated with industry funding, and a ClinicalTrials.gov only publication rate of 6%. These are in keeping with our results, which showed a non-publication rate of 33.8% and a ClnicalTrials.gov only publication rate of 6.4%. This demonstrates importance in both large and small clinical trials. As larger trials were more likely to be published, the specific challenges encountered in often smaller surgery specific trials leading to this attrition may be different and require further definition. Aligned with this, a recent study assessing the rate of non-publication in trials relating to medical vaccines reported similar results, with a non-publication rate of 50.4%.4 Our study confirms the relevance of these findings in surgery specific studies and provides direct evidence to the surgical community of the need for reform.

Meaning of study: implications for clinicians and policy makers

The advent of clinical trial registration has provided the necessary foundation to increase transparency and awareness of research methodology. Taken together with previous work quantifying trial outcomes in other medical specialties,2 5 14 15 16 17 18 this study shows an urgent need to solve problems of research capacity and resource wastage, hidden or lost knowledge through trial discontinuation and non-publication, and difficulties relating to communication with people responsible for conducting such trials. As the extent of these problems continues to become more apparent, new strategies to combat them are needed to augment current international, national, and local research governance frameworks. Input from all stakeholders is needed, including funding and commissioning bodies, regulatory groups (both medical and governmental), ethics review boards, and the public and private institutions hosting such clinical research activities.

This study found that both multicentre and international trials were associated with higher rates of discontinuation, which highlights difficulty in their delivery. Completed studies with larger patient numbers were more likely to be published, so investment in their delivery is worthwhile. As national surgical networks develop to deliver multicentre trials, their potential to deliver robust international multicentre trials remains untested.19 If successful, these could greatly increase the generalisability of findings and, with well functioning networks, could speed recruitment.

Industry funding had the strongest association with non-publication of completed studies, although in common with previous studies we are unable to identify the reasons for this. It may be a function of industry held data, conduct of industry trials, or research teams failing to publish. Surgical collaboration with industry through an appropriate governance framework is still likely to be beneficial for patients, driving innovation in devices and drugs, and policy makers should work to ensure healthy collaborative relationships. Funders should also be willing to support trials with potentially negative results, which could include trials discontinued early. Although investigators’ responses from this study identified negative findings as a barrier to publication, several journals now carry a commitment to publish negative studies that have high methodological rigour.20

Recommendations and future research

The optimum framework to deliver surgical trials that are likely to succeed in a timely fashion is unclear, and a considerable need exists for surgery specific guidance in this area. All funders should expect value for money and timely delivery of such studies. For surgical trials, this may involve targeting the limited resources available to research teams who have the resources and infrastructure to deliver larger multicentre trials. In this way, efficiency is increased, maximising use of the available research capacity. This should not hinder the establishment of new researchers, but rather they should enter an existing structural framework that will help them to deliver across a multicentre platform.

A ban on publishing industry funded research, which has been suggested, could harm surgical innovation and should be discouraged.21 Rather, frameworks should be put in place to match industry funders to independent, clinically driven researchers who can deliver trials that are relevant to patients and who can hold data independently. In any collaboration with industry, academic investigators must remain free to publish their findings without risk of a sponsor’s veto, in keeping with good publishing practices.22

Internationally, the World Medical Association’s “Declaration of Helsinki,”23 detailing the ethical principles of medical research involving humans, includes the statement that “Authors have a duty to make publicly available the results of their research on human subjects.” This ethical duty should be incorporated into agreements put in place by research funding and commissioning bodies, with regulatory oversight and enforcement. Holding trial data in secure and independent trials units may prevent any intentional or unintentional losses in the future. This also promotes the importance of data sharing, ideally through open access data platforms. Such structures would also overcome difficulties encountered in communication with corresponding investigators, which can be time consuming, inefficient, and often fruitless (as shown in this study), further reducing transparency. Even in cases in which no journal paper is written, ensuring open access publication of datasets for completed studies will satisfy this obligation.

To enable improved communication, a permanent contact should be made publicly available from the point of trial registration. In future, this contact may be best suited to a permanent “clinical data controller” role within the clinical trial regulatory framework, whereby a nominated person identified by the initiator of the study ensures access to trial data. This will ensure that contact is not lost as named principal investigators move on in their careers. This may be of great interest to patients, who can track results and query investigators directly if data remain non-published.

Finally, patients recruited to surgical trials are probably not aware of or informed about the risk of early termination or non-publication. Ethically, patients and the wider medical profession must consider this serious problem. A fully informed decision to participate in a trial is an absolute requirement, and persistence of these problems may further hinder recruitment to trials through a perception of futility and altered balance of risks. Careful consideration and guidance around this matter is needed.

What is already known on this topic

Non-publication of randomised trials is common, exposing patients to the risks of participating in trials while bringing no benefit to the wider community

Interventional surgical trials are challenging to design and deliver and are expensive to conduct

Evidence exists of resource wastage in medical and surgical randomised trials

What this study adds

Considerable resource wastage exists in the conduct of modern surgical trials, identified through early termination due to insufficient recruitment and non-publication after completion

Most, but not all, investigators’ contact email addresses are identifiable through focused searches, although investigators are frequently not contactable when asked for additional information

Contributors: SJC, JEF, EH, and AB conceptualised the study. SJC, BS, and HM did searches and extracted data, which were verified by AB. SJC and AB prepared the initial manuscript drafts, which were subsequently edited by all authors. All authors agreed to submission. AB is the guarantor.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Transparency: The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2014;349:g6870

References

- 1.Chan AW, Song F, Vickers A, Jefferson T, Dickersin K, Gøtzsche PC, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste: addressing inaccessible research. Lancet 2014;383:257-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones CW, Handler L, Crowell KE, Keil LG, Weaver MA, Platts-Mills TF. Non-publication of large randomized clinical trials: cross sectional analysis. BMJ 2013;347:f6104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasenda B, von Elm E, You J, Blümle A, Tomoanga Y, Saccilotto R, et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and publication of discontinued randomized trials. JAMA 2014;311:1045-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manzoli L, Flacco ME, D’Addario M, Capasso L, De Vito C, Marzuillo C, et al. Non-publication and delayed publication of randomized trials on vaccines: survey. BMJ 2014;348:g3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garas G, Ibrahim A, Ashrafian H, Ahmed K, Patel V, Okabayashi K, et al. Evidence-based surgery: barriers, solutions, and the role of evidence synthesis. World J Surg 2012;36:1723-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Royal College of Surgeons of England. From innovation to adoption: successfully spreading surgical innovation. London: RCSENG Communications, 2014.

- 7.Killeen S, Sourallous P, Hunter IA, Hartley JE, Grady HL. Registration rates, adequacy of registration, and a comparison of registered and published primary outcomes in randomized controlled trials published in surgery journals. Ann Surg 2014;259:193-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeAngelis CD, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, Haug C, Hoey J, Horton R, et al. Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. JAMA 2004;292:1363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huser V, Cimino JJ. Linking ClinicalTrials.gov and PubMed to track results of interventional human clinical trials. PLoS One 2013;8:e68409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US National Institutes of Health. Trends, charts and maps. 2014. www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/resources/trends#RegisteredStudiesOverTime.

- 11.National Institutes of Health. Glossary of common site terms. 2014. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/about-studies/glossary.

- 12.Gray R, Sullivan M, Altman DG, Gordon-Weeks AN. Adherence of trials of operative intervention to the CONSORT statement extension for non-pharmacological treatments: a comparative before and after study. Ann R Coll Surg Eng 2012;94:388-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenthal R, Kasendra B, Dell-Kuster S, von Elm E, You J, Blümle A, et al. Completion and publication rates of randomized controlled trials in surgery: an empirical study. Ann Surg 2014. (in print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Ross JS, Mulvey GK, Hines EM, Nissen SE, Krumholz HM. Trial publication after registration in ClinicalTrials.Gov: a cross-sectional analysis. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ross JS, Tse T, Zarin DA, Xu H, Zhou L, Jrumholz HM, et al. Publication of NIH funded trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov: cross sectional analysis. BMJ 2012;344:d7292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Von Elm E, Rollin A, Blümle A, Huwiler K, Egger M. Publication and non-publication of clinical trials: longitudinal study of applications submitted to a research ethics committee. Swiss Med Wkly 2008;138:197-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blümle A, Meerpohl JJ, Schumacher M, von Elm E. Fate of clinical research studies after ethical approval—follow-up of study protocols until publication. PLoS One 2014;9:e87184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee K, Bacchetti P, Sim I. Publication of clinical trials supporting successful new drug applications: a literature analysis. PLoS Med 2008;5:e191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhangu A, Kolias AG, Pinkney T, Hall NJ, Fitzgerald JE. Surgical research collaboratives in the UK. Lancet 2013;382:1091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehman R, Loder E. Missing clinical trial data. BMJ 2012;344:d8158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chapman S, Bhangu A. Ban on publishing industry funded research could harm surgical innovation. BMJ 2014;348:g1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graf C, Battisti WP, Bridges D, Bruce-Winkler V, Conaty JM, Ellison JM, et al. Good publication practice for communicating company sponsored medical research: the GPP2 guidelines. BMJ 2009;339:b4330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013;310:2191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]