Abstract

Coral diseases impact reefs globally. Although we continue to describe diseases, little is known about the etiology or progression of even the most common cases. To examine a spectrum of coral health and determine factors of disease progression we examined Orbicella faveolata exhibiting signs of Yellow Band Disease (YBD), a widespread condition in the Caribbean. We used a novel combined approach to assess three members of the coral holobiont: the coral-host, associated Symbiodinium algae, and bacteria. We profiled three conditions: (1) healthy-appearing colonies (HH), (2) healthy-appearing tissue on diseased colonies (HD), and (3) diseased lesion (DD). Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis revealed health state-specific diversity in Symbiodinium clade associations. 16S ribosomal RNA gene microarrays (PhyloChips) and O. faveolata complimentary DNA microarrays revealed the bacterial community structure and host transcriptional response, respectively. A distinct bacterial community structure marked each health state. Diseased samples were associated with two to three times more bacterial diversity. HD samples had the highest bacterial richness, which included components associated with HH and DD, as well as additional unique families. The host transcriptome under YBD revealed a reduced cellular expression of defense- and metabolism-related processes, while the neighboring HD condition exhibited an intermediate expression profile. Although HD tissue appeared visibly healthy, the microbial communities and gene expression profiles were distinct. HD should be regarded as an additional (intermediate) state of disease, which is important for understanding the progression of YBD.

Keywords: 16S rRNA gene, Orbicella faveolata, Montastraea faveolata, PhyloChip, coral reefs, yellow band blotch disease

Introduction

Corals engage in symbioses with a diverse array of microbes (Douglas, 1998; Wegley et al., 2007). Tropical corals thrive in nutrient-limited waters largely owing to their symbioses (Muscatine and Porter, 1977). Recent analysis of this complex metaorganism (that is, the coral holobiont) revealed great microbial diversity (Rohwer et al., 2002). One member of this holobiont, that many tropical and sub-tropical corals harbor, is a unicellular alga of the genus Symbiodinium, which harnesses light energy and transfers fixed carbon and other organic compounds to the coral-host (Trench, 1979). In addition, corals harbor a large diversity of bacteria, some of which appear to be host-specific (Rohwer et al., 2001; Sunagawa et al., 2010; Roder et al., 2014). Of the ones that have been studied, many are beneficial to the holobiont by promoting coral health, defense and nitrogen fixation (Lesser et al., 2004; Ritchie, 2006; Chimetto et al., 2008; Alagely et al., 2011; Lema et al., 2012). These recent findings highlight the importance of deepening our understanding of host–microbe interactions in coral reef environments (Ainsworth et al., 2009; Mouchka et al., 2010), yet high throughput genomic analyses have revealed that most of the coral-associated bacteria are unclassified (Sunagawa et al., 2010).

In the last 50 years, coral reef ecosystems have drastically declined (Wilkinson, 2008). Since the mid-1970s (Dustan, 1977) coral disease events have become pervasive throughout the world's oceans (Sutherland et al., 2004; Weil et al., 2006; Bourne et al., 2009). Anthropogenic pressures such as increasing sea surface temperatures, coastal development, depletion of fisheries and high-nutrient effluents, impact coral health and exacerbate disease outbreaks (Bruno et al., 2003; Cervino et al., 2004; Bruno et al., 2007; Brandt and McManus, 2009). Metagenomic approaches have revealed higher numbers of potentially pathogenic bacteria along gradients of anthropogenic activity (Vega Thurber et al., 2009). As human activities increase both locally and globally, reef systems continue to decline (Pandolfi et al., 2003; Hughes et al., 2010).

In recent decades, the Caribbean Sea has become a disease hotspot (Dustan, 1977) and its shallow reefs are the most impacted worldwide (Bourne et al., 2009). Many coral diseases manifest themselves in necrosis of the coral tissue followed by macroalgal colonization of the bare skeleton (Richardson, 1998; Knowlton and Jackson, 2008). Continuous episodes of disease can ultimately lead to a macroalgal-dominated reef with major consequences for biodiversity and the survival of scleractinian corals (Bruckner and Bruckner, 2006; Knowlton and Jackson, 2008).

One common disease in the Caribbean is Yellow Band Disease (YBD), also known as ‘Yellow Blotch Disease'. YBD was first noted off the coast of the Florida Keys in 1994 (Reeves, 1994) and has since been identified throughout the region. In some reefs, as high as 88% of Orbicella spp. colonies exhibited signs of YBD (Richards Dona et al., 2008). YBD has been reported for the Orbicella annularis species complex, Montastraea cavernosa, and the Colpophyllia natans species complex (Bruckner and Bruckner, 2006). Orbicella spp. (formerly part of the genus Montastraea, but recently reclassified to the Orbicella genus (Budd et al., 2012)) are major reef-building species. Coral die-offs driven by YBD have detrimental, long-term consequences for Caribbean reefs (Gardner et al., 2003). YBD is characterized by a 1–5 cm wide, yellow to white, circular band that radiates outwards (Reeves, 1994). As it progresses, necrotic tissue sloughs off exposing the denuded skeleton. The band has been recorded to spread about 0.6 cm per month (Cervino et al., 2001), a relatively slow rate of progression compared with other coral diseases, for example, White Plague Disease typically progresses by 0.3–2 cm per day (Richardson, 1998). However, YBD lesions are often seen on multiple areas of a colony and can persist over multiple seasons until a large portion of or the entire colony is decimated. The gradient of yellow to white band color is a result of declining algal symbiont densities (Cervino et al., 2001). Cervino et al. (2004) identified four Vibrio spp. as the putative causative agents for YBD using traditional isolation and culturing techniques. Recently, YBD has been reported to affect other coral species in the Indo-Pacific, that is, Diploastrea heliopora, Fungia spp. and Herpolitha spp. (Cervino et al., 2008).

Given the rapid reef decline worldwide, there is a pressing need for novel approaches for coral disease diagnostics (Pollock et al., 2011). Both bacterial and Symbiodinium community composition have been assessed in some coral diseases (Cervino et al., 2004). However, the host physiological response has been evaluated mainly in the context of thermal stress (DeSalvo et al., 2008; Barshis et al., 2013) and never in conjunction with microbial community profiling. Host transcriptome profiling can enhance our understanding of how corals are responding to disease outbreak. We combine these three approaches, that is, bacterial taxonomic profiling, Symbiodinium genotyping, and host transcriptome response to gain insight into the dynamics of YBD in the coral Orbicella faveolata. 16S ribosomal RNA gene microarrays, known as ‘PhyloChips', provide a culture independent method to monitor relative abundance of a set of bacterial taxa under different conditions (Brodie et al., 2006), and have been extensively used in different biological systems (Wu et al., 2010; Mendes et al., 2011), including corals (Sunagawa et al., 2009b; Kellogg et al., 2012; Roder et al., 2014). Coral transcriptome profiling has been used to examine differential gene expression under multiple physiological and developmental conditions (DeSalvo et al., 2008; Voolstra et al., 2009a, 2009b; Portune et al., 2010; Bellantuono et al., 2012; Kaniewska et al., 2012; Barshis et al., 2013). Herein we extend the use coral complimentary DNA (cDNA) microarrays to examine host response to disease.

To our knowledge this is the first study to examine multiple facets of the holobiont in a range of health states, including healthy-appearing tissue neighboring the disease lesion. This approach aimed to allow a better understanding of the progression of YBD and to provide insights into part of the coral holobiont's response. We show that beyond visual signs of a disease, the associated microbiome and coral-host transcriptome dramatically shift in O. faveolata. The combination of molecular tools used identified associated bacterial taxa and genes that distinguish samples, which appear phenotypically healthy, from healthy colonies. These results advance our understanding of YBD progression and could be used to design an early screen for detecting elevated transcription of key genes as well as presence of indicator taxa highlighted herein.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and preparation

We collected skeletal-tissue cores of O. faveolata on 2 September 2008 along the coast of Puerto Morelos, Mexico. Samples were collected using hammer and corer (2 cm diameter) by SCUBA at an average depth of 6 m at Los Jardines reef in Puerto Morelos National Marine Park (N 20.831230, W 86.874350). We collected a total of 12 samples from eight colonies: one set of samples from four healthy colonies (HH), which exhibited no visually apparent signs of stress or impacted health and two sample sets from four diseased colonies; one set of four samples from the advancing disease lesion (DD), yellowish tissue interface adjacent to the recently denuded skeleton; and one set of samples from neighboring tissue which had no apparent physical signs of disease (HD) 30–90 cm from the lesion, on the same coral colonies.

Using SCUBA we sampled each colony underwater and cores were placed into Whirl-Pak bags (Nasco, Fort Atkinson, WI, USA). The samples were transferred to the boat, quickly rinsed with filtered seawater, wrapped in aluminum foil and subsequently flash-frozen in a liquid nitrogen dry shipper. At UC Merced, excess skeleton was removed with mallet and sterile chisel. The residual upper tissue/skeleton (<0.5 cm) layer was ground into a homogenous powder using a sterilized mortar and pestle cooled to −78.5 °C. The entire homogenization process took place on dry ice.

DNA extraction and generation of 16S ribosomal DNA amplicons

From each sample, we added 50 mg of frozen homogenized coral powder to a screw-cap tube. We performed DNA extractions as described in the study by Sunagawa et al. (2010). We amplified 16 S ribosomal RNA genes in 100 μl reactions using the extracted DNA (20 ng), 0.8 μM of the universal primers 27 F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492 R (5'-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′), Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity (0.4 μl), and PCR buffer (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA). We ran gradient amplifications (annealing temperatures from 48 to 60 °C) using 25 cycles. We purified pooled products for a given sample with the MinElute Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), and hybridized them to third generation (G3) PhyloChips (Second Genome, South San Francisco, CA, USA) as described in the study by Hazen et al. (2010).

PhyloChip hybridization

The 16S ribosomal RNA G3 PhyloChip was expanded to contain multiple oligonucleotide probes to identify across 59 222 operational taxonomic units (OTUs), representing a majority of the known diversity in Bacteria and Archaea. The PhyloChip was designed to track population dynamics in the majority of known bacterial and archaeal taxa from publically available databases (Wu et al., 2010), which included 943 identified O. faveolata-associated sequences (Sunagawa et al., 2009b).

We used a total of 230 ng of pooled gradient amplicon products from each sample for hybridization. One sample, HH4, did not yield sufficient PCR product for PhyloChip analysis. For the remaining samples, we followed published procedures for sample preparation for hybridization (Wu et al., 2010). PhyloChips were washed and stained following Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA, USA) protocols. PhyloChips were scanned as previously described (Wu et al., 2010).

PhyloChip data analysis

We generated CEL files from probe fluorescence intensities of the scanned microarrays using PhyloChip Analysis parameters (Wu et al., 2010) through Stage 1 for taxa selection, allowing unclassified microbial taxa (OTUs) to be included in the output files. Hybridization fluorescence intensities were scaled to the internal spike mix to allow comparison across samples. OTUs present in three or more samples under each condition were used for subsequent analyses. Presence/absence calling of each was based on positive hybridization of multiple probes that correspond to an OTU (average of 37 probes per OTU). The resulting fluorescence data were log2 transformed.

We used the Bioconductor package ‘limma' (Smyth, 2004) for further analysis in R; log2-transformed values were compared using pair-wise comparisons. Results were filtered at a P-value⩽0.05 and a log fold change (FC)⩾2. The data were loaded into MeV v4.6.1 (TM4, Boston, MA, USA) (Saeed et al., 2003) for visualization.

Symbiodinium 18S amplification and clade identification

Symbiodinium 18S ribosomal RNA gene fragments were amplified using universal forward primer ss5 (5′-GGTTGATCCTGCCAGTAGTCATATGCTTG-3′), Symbiodinium-specific reverse primer ss3z (5′-AGCACTGCGTCAGTCCGAATAATTCACCGG-3′) (Rowan and Powers, 1991) and Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity. The amplified fragments were digested with TaqI restriction enzyme (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), ran on a 1% agarose gel, and compared across Symbiodinium A–D clade standards following the protocol by Rowan and Knowlton (1995).

Host genotyping

We assessed clonal similarities using the methods described in the study by Davies et al. (2013). The eight coral colonies sampled proved to be genets. No clones were identified, as assessed by nine microsatellite markers: maMS8_CAA, Mfav5_CGA, Mfav7_CAT, Mfav3_ATG, Mfav4_TTTG, Mfav6_CA, Mfav9_CAAT, Mfav30_TTTTG and Mfav8_CAA.

RNA extraction and amplification for coral cDNA arrays

From each frozen homogenized coral sample described above, we isolated total RNA using QIAzol Lysis Reagent (Qiagen), two chloroform extractions, subsequent isopropanol precipitation and two successive 70% ethanol washes. RNA pellets were redissolved in 100 μl of nuclease-free water and quantified using a ND1000 (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE, USA). The samples were concentrated using 3 M sodium acetate and ethanol precipitation, and further purified using the RNeasy MinElute Cleanup Kit (Qiagen). RNA quality was assessed with a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). With the modified steps outlined in the study by DeSalvo et al. (2008, 2012), we amplified 1 μg of total RNA using the MessageAmp II aRNA kit (Ambion, Foster City, CA, USA).

Composition of pooled reference sample and hybridization of cDNA

A total of 3 μg of amplified RNA from each sample was reverse transcribed into cDNA and purified with the RNeasy MinElute Kit. Equal amounts of amplified RNA aliquots from each sample comprised the pooled reference. Reference and individual samples were labeled with Cy-3 and Cy-5 dyes, respectively. After fluorescent labeling, we purified samples with the RNeasy MinElute Kit to remove any excess dye.

The second generation (G2) O. faveolata cDNA microarray slides, referred here on as cDNA microarrays, were designed and printed with 10 930 features at UC Merced's Genome Core Facility (Aranda et al., 2011). We post-processed, hybridized and scanned the O. faveolata cDNA microarray slides as described in the study by DeSalvo et al. (2012). Each of the 12 samples from the three health states (that is, HH, HD, DD) were competitively hybridized against a pooled reference sample. After overnight hybridization, slides were immediately transferred to individual falcon tubes containing wash buffers (0.6 × saline-sodium citrate (SSC) and 0.01%SDS, followed by 0.06 × SSC) to remove non-specific hybridization and unbound excess cDNAs. Slides were scanned using an Axon GenePix 4000B scanner (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), and photomultiplier tube gain settings were individually adjusted to balance and maximize the dynamic range for both channels.

cDNA microarray data analysis

Scanned Tagged Image File Format images were analyzed with GenePix Pro 6.0 (Molecular Devices), with the following steps: 1) find, align and fill irregular features, and 2) flag features, which match the query: (Circularity)=0 OR (Sum of Medians (635/532))⩽400 OR (F532% Sat.)>5 OR (F635% Sat.)>5. GenePix result files were converted into the TIGR MultiExperiment Viewer file format using the TIGR ExpressConverter (TM4, Version 2.1). Using TIGR MIDAS 2.22 (TM4) (Saeed et al., 2003), data were locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS) normalized, block and slide standard deviation regularized, and in-slide duplicates were averaged.

We filtered expression data to include only those features for which a minimum of three out of four samples per condition had fluorescence values. Resulting fluorescence data were log2 transformed. Using the Bioconductor package ‘limma' (Smyth, 2004) for further analysis in R (R Core Team, 2012), the log2-transformed values were compared using pair-wise comparisons and adjusted P-values for multiple testing using a false discovery rate <0.05 (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). Visualizations of the data were performed using MeV v4.6.1 (Saeed et al., 2003).

Results

PhyloChips hybridizations

Of 59 222 OTUs complementary to PhyloChip probe sets, 4102 hybridized and passed filter parameters (Hazen et al., 2010). Many were unclassified in the reference database and ∼50% (2068) lacked family level annotation.

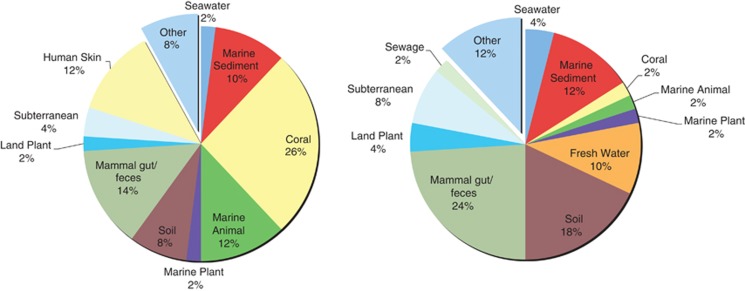

More terrestrial-originated sequences in diseased samples

A shift was observed towards increasing sequences of terrestrial origin in the diseased samples. The 50 most abundant sequences on the PhyloChip for HH and DD were markedly different. Bacterial sequences originally isolated from marine environments made up more than half of the most abundant in the HH sample (52%); a quarter (26%) were originally isolated from corals. In DD, only 22% were from marine environments, while 66% were sequences originally isolated from terrestrial environments. Only 2% of the hybridized spots in DD represented sequences originally isolated from corals (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The top 50 most abundant, unique sequences in HH (left) and DD (right) conditions, which contained sequences that were originally sampled from terrestrial (for example, soil, fresh water and mammal gut/feces) and marine environments (for example, marine sediment, seawater, coral, marine animals). These delineations revealed an increase in terrestrial-associated sequences with DD samples.

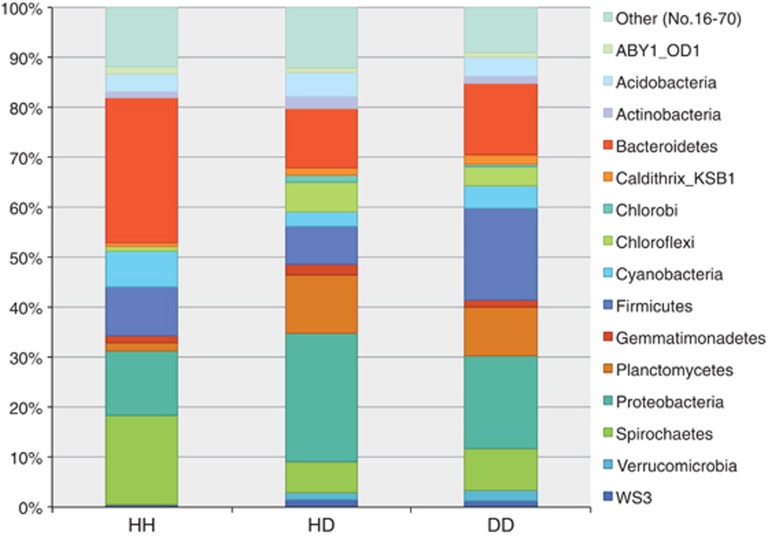

Higher bacterial richness in diseased samples

Overall, 70 classified bacterial phyla were represented. Most phyla were identified in diseased samples (Table 1). DD samples had almost double the amount of phyla (n=30) compared with healthy (n=16). HD had the most phyla associated (n=44). To measure relative richness each sample was compared with the grand total (Table 2). Relative richness revealed changes in the community structure of the 15 richest phyla (Figure 2). HH samples had the highest relative richness of Bacteroidetes, Spirochetes and Proteobacteria (Gammaproteobacteria). In DD, Firmicutes showed the greatest relative richness. Relative richness in HD was similar to DD, however Proteobacteria was richest in HD and, of those, the majority were Alphaproteobacteria.

Table 1. The average number of bacterial taxa identified per condition out of the maximum number matched at each taxonomic level, unclassified taxa excluded.

| Taxonomic level (n) | Healthy colonies | Diseased colonies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n identified in HH (%) | n identified in HD (%) | n identified in DD (%) | |

| Phylum (70) | 16 (23%) | 44 (63%) | 30 (43%) |

| Class (276) | 22 (8%) | 118 (43%) | 68 (25%) |

| Order (179) | 16 (9%) | 78 (44%) | 47 (26%) |

| Family (188) | 15 (8%) | 70 (37%) | 44 (23%) |

Abbreviations: DD, diseased lesion; HD, healthy-appearing tissue on diseased colonies; HH, healthy-appearing colonies.

Table 2. Richness totals for each taxonomic level across all three health conditions; classified richness, left, vs unclassified richness, right.

| Taxonomic level |

HH(88) |

HD(684) |

DD(336) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classified (%) | Unclassified (%) | Classified (%) | Unclassified (%) | Classified (%) | Unclassified (%) | |

| Phylum | 65 (74%) | 23 (26%) | 526 (77%) | 158 (23%) | 252 (75%) | 84 (25%) |

| Class | 44 (50%) | 44 (50%) | 314 (46%) | 370 (54%) | 157 (47%) | 179 (53%) |

| Order | 38 (43%) | 50 (57%) | 254 (37%) | 430 (63%) | 132 (39%) | 204 (61%) |

| Family | 25 (28%) | 63 (72%) | 152 (22%) | 532 (78%) | 87 (26%) | 249 (74%) |

Abbreviations: DD, diseased lesion; HD, healthy-appearing tissue on diseased colonies; HH, healthy-appearing colonies.

Figure 2.

Mean community structure of the 15 richest phyla across all health conditions. Chlorobi and Verrucomicrobia were identified exclusively in the diseased samples. Bacteriodetes, Cyanobacteria and Spirochetes were richest in HH. Proteobacteria were richest in HD, dominantly Alphaproteobacteria. Firmicutes were richest in DD.

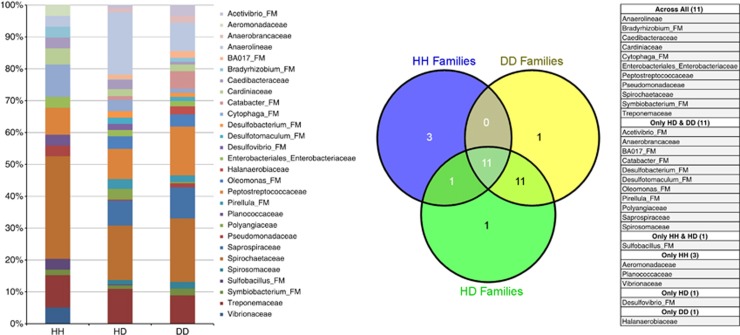

Differential family abundances

Descriptive richness was measured by comparing the number of families associated with one sample to the total within each condition. For the top 15 families, composition varied between health conditions (that is, HH, HD, and DD). In total, all health conditions comprised 28 bacterial families; 11 of those top families were found in all three conditions. Eleven families were most abundantly associated with only HD and DD (Figure 3). Sulfobacillus_FM was associated with both, HH and HD, but not DD. Vibrionaceae, Planococcaceae and Aeromonadaceae were in the top 15 families in HH. Desulfovibrio_FM was most abundantly associated with HD and Halanaerobiaceae with DD.

Figure 3.

Descriptive family richness stacked bar chart for the top 15 families in each condition. There was a large overlap between the top families associated with HD and DD. Spirochaetaceae was dominant in HH samples. The Venn diagram and table show families such as Aeromonadaceae, Planococcaceae, and Vibrionaceae that were top families only in HH. Eleven families were associated with only HD & DD samples. Desulfovibrio_FM was highly abundant only in HD samples, while Halanaerobiaceae was richest in DD samples.

Additional significant classified families resulted from the limma pair-wise comparisons (Supplementary Figure 1). Of these, Vibrionaceae was the most abundant family in HH samples. Based on log2 values, Planococcaceae, Enterobacteriales_Enterobacteriaceae, and Fusobacteriaceae were also abundant families in HH. Pirellula and BCf2-25, both Plantomycetes, were the two most abundant families associated with HD samples. Rhodoplanaceae, Ruminococcus, Azospirillaceae and Phyllobacteriaceae, were differentially abundant in the HD condition. Peptostreptococcaceae was the most abundant family in DD (FC=3.01), but Halanaerobiaceae, Catabacter and Ruminococcus were also prevalent.

Differential OTU abundances

Limma pair-wise analyses identified 124 significant OTUs at P<0.05 and FC⩾2. When HH samples were compared with HD samples, 94 significant OTUs were identified. HD vs DD comparison resulted in 44 significant OTUs. HH to DD comparisons identified 41 OTUs (Supplementary Figure 1). While some OTUs did overlap, a distinct bacterial community structure defined each of the health conditions.

The most abundant OTUs in both the HH and HD samples were originally discovered in association with marine organisms, however, the majority of these were unclassified. Across samples of all three health conditions the proportion of unclassified OTUs was similar at each taxonomic level.

Distinct Symbiodinium populations & coral genotypes

Restriction fragment length polymorphism signatures identified the majority taxa associated with each health condition; HH samples, two samples had clade A and two hosted clade C (Table 3). The HD samples were most diverse. All DD samples hosted clade A with one sample also harboring clade C. In addition, host genotyping confirmed that all coral colonies sampled were genets and not clones.

Table 3. Associated Symbiodinium clades per sample furcate according to health condition.

| Sample | Clade 1 | Clade 2 | Clade 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| HH1 | C | ||

| HH2 | A | ||

| HH3 | A | ||

| HH4 | C | ||

| HD1 | C | ||

| HD2 | C | ||

| HD3 | C | D | A |

| HD4 | C | D | B |

| DD1 | A | C | |

| DD2 | A | ||

| DD3 | A | ||

| DD4 | A |

Abbreviations: DD, diseased lesion; HD, healthy-appearing tissue on diseased colonies; HH, healthy-appearing colonies.

Clade C and A were each dominant in two samples of HH. Clade C was dominant in HD. Clade A was dominant in the DD samples

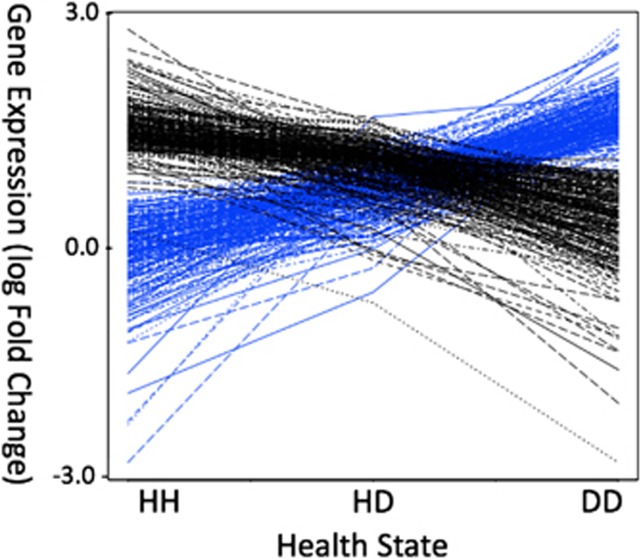

Distinct host-transcriptomic response

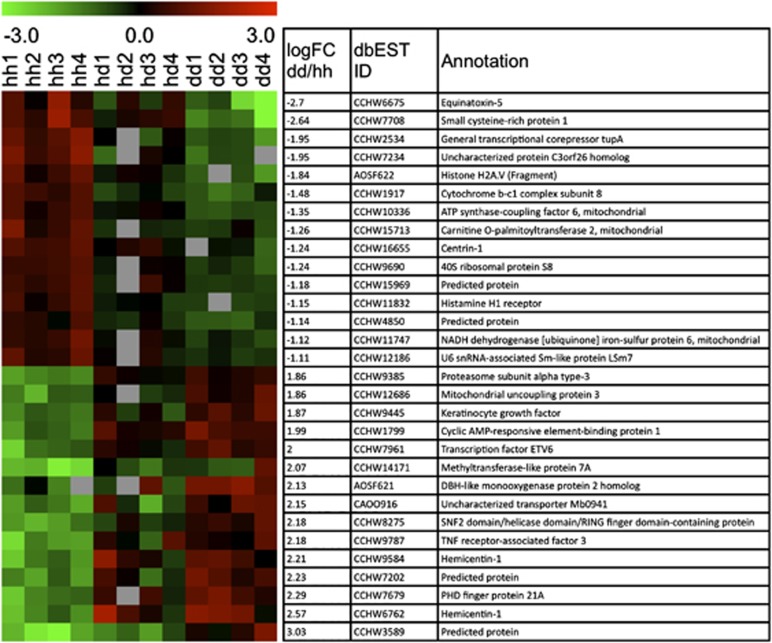

After hybridization to the coral cDNA microarray, 6,620 genes passed the filtering criteria. At P<0.01 (n=431), more than 80% of the genes exhibited increasing or decreasing expression trends, where HH and DD had opposite expression patterns, while HD consistently exhibited intermediate gene expression (Figure 4). The host cDNA array analysis (false discovery rate=5) resulted in 134 significantly expressed genes across all three pair-wise comparisons.

Figure 4.

DEGs show distinct expression differences across health conditions, with healthy-diseased often having an intermediate expression signal. Greater than 80% (n=438) of the 500 significant genes (P<0.01) show a trend of either continuous up (blue, n=221) or down (black, n=217) regulation of transcripts when comparing expression values across all three health conditions.

HH vs DD comparison resulted in 132 significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with 83 upregulated and 49 downregulated genes in the DD samples (Supplementary Table 1). The five genes with the highest log FC ranged from 2.82 to 3.74, but have unknown functions. Of the 132 DEGs, 63 were annotated (Figure 5 for the condensed list and FC values). The annotated DEGs with the largest FC were Equinatoxin-5 (NCBI dbEST ID: CCHW6675) and small cysteine-rich protein 1 (CCHW7708), which were downregulated in DD (−2.70 and −2.64, respectively). Hemicentin-1 (CCHW6762) was the most upregulated annotated gene in the diseased samples (FC=2.57). Of the 132 significant genes, 117 were solely significant in the HH vs DD comparison and not significant in the other comparisons.

Figure 5.

Heatmap of the 15 most upregulated as well as downregulated DEGs across the three conditions determined by limma (false discovery rate=5). Negative log FC represents downregulated genes in DD, positive represent upregulated in DD (left column) resulting from DD vs HH comparison. NCBI dbEST ID and Annotations characterize the DEGs (right columns).

The HH vs HD comparison revealed 16 significant DEGs. One (CCHW60626) was downregulated and 15 were upregulated in the HD samples. Only two of the upregulated genes were annotated, cyclic AMP-responsive element-binding protein 1 (CCHW1799) and proteasome subunit alpha type-3 (CCHW9385). Two of the genes (CCHW12270 and CCHW6026) were found to be significant only in the HH vs HD comparison.

Only one unannotated gene (AOSF808) was differentially expressed between HD vs DD. The DD condition was downregulated (FC=−1.81) relative to HD.

Discussion

Multiple stressors compromise coral health and leave them susceptible to disease. Although YBD was described in the Caribbean in the mid-90's, the method of transmission remains elusive. How diseases affect the holobiont and its dynamic microbial assemblage, which may have a role in disease progression, is also still poorly known. Baseline descriptive data corresponding to different health states, exemplified in this study, are the key to understanding the etiology of a disease.

Bacterial community shifts under different health states

Coring provided reproducible results when assessing the coral-associated bacterial community structure as also observed by Kellogg et al. (2012). The community structure changed dramatically when comparing healthy (HH) to diseased (HD and DD) colonies. Differences were also observed between HD and DD. Our data are consistent with other studies that showed increased bacterial richness in impacted corals over healthy (Table 2) (Sunagawa et al., 2009b; Vega Thurber et al., 2009; Roder et al., 2014).

The highest bacterial richness was observed in the healthy-appearing tissue on the diseased colonies (HD). High bacterial diversity in these tissues likely reflects disequilibrium in the community structure and may represent a transitional community or competition after a disturbance (Costello et al., 2012). Opportunistic taxa may compete for available resources and take advantage of the impaired defense system. This ultimately may increase some members or new colonists, while decreasing other members and give rise to the increased taxa associated with disease (Sunagawa et al., 2009b; Vega Thurber et al., 2009; Roder et al., 2014). Richness may be further inflated because of factors such as proximity to the lesion, symbiont composition and micro-environmental differences.

The most abundant OTUs in this dataset were associated with sequences previously identified from coral, mammal guts and sediments. OTUs frequently found in diseased colonies were often related to bacteria that have been associated with fecal or gut communities. This evidence supported the idea that a healthy microbial community may be destabilized by high nutrients (Bruno et al., 2003; Kimes et al., 2010) and terrestrial run-off. Fluctuations in community structure could exacerbate YBD.

Vibrionaceae have been described as potential causative agents for YBD (Cervino et al., 2004). Cróquer et al. (2013) found Vibrio spp. to be dominant in diseased mucus. However, in this dataset and other YBD studies (Cunning et al., 2009), Vibrionaceae were noticeably more abundant (2–10x) in healthy samples (Supplementary Figure 1). Some Vibrios are commensal in healthy corals (Chimetto et al., 2008; Koenig et al., 2011; Krediet et al., 2013). This does not negate that it may be possible for Vibrios to become pathogenic as environmental conditions change or genomic modifications occur, such as activation, shuffling or transfer of gene cassettes (Koenig et al., 2011).

Firmicutes, such as Peptostreptococcaceae, Clostridiaceae, Thermoanaerobacteriaceae, Ruminococcus_FM, Halanaerobiaceae, and Clostridium_FM, were more abundant in diseased samples. Many of these are anaerobic families or facultative anaerobes, suggesting that under diseased conditions oxygen-limitation may favor anaerobic bacteria. Peptostreptococcaceae was the most abundant family in DD samples and has been observed in other coral diseases, both Black Band (Sekar et al., 2009) and White Plague (Sunagawa et al., 2009b). Sunagawa et al. (2009b) also observed abundant Clostridiaceae in White Plague samples. Firmicute_Clostridia along with Actinobacteria, both Gram-positive bacterial groups, dominated DD samples. Gram-negative bacteria were less represented in DD samples. The above families all contain known pathogens and many have been linked to sewage-related samples.

HH samples were strongly associated with Proteobacteria_Gammaproteobacteria and Bacteroidetes, both gram-negative bacterial groups. Fusobacteria (Gram (−)), Acidobacteria (Gram (−)), Planctomycetes (Gram (−)) and Actinobacteria (Gram (+)) were each represented once.

Pseudoalteramonas, which has been previously associated with YBD (Cervino et al., 2004) was not measured in high abundance. However, other Pseudomonadaceae were present at low abundance, in all health states. Abundances were even lower in diseased samples compared with HH and HD. Crenotrichaceae, which associates with sponges and has been sampled from seawater, was most abundant in the HD samples. These data supported the hypothesis that the bacterial community is shifting in regions adjacent to the lesion. Microbial taxa from the surrounding water column may colonize during these shifts, which suggests that the disease-associated community may change with season or geographic location.

Symbiodinium clade differences in various health states

O. faveolata associates with Symbiodinium from clades A, B, C and D (Garren et al., 2006; DeSalvo et al., 2010; Thornhill et al., 2010, 2013). Both A and C were present in HH. Clade C dominated the HD condition. Half of the HD samples also contained D with traces of either clade A or clade B. Finally, DD samples contained mostly clade A; however, one sample also hosted clade C. Cervino et al. (2004) showed that intercellular Symbiodinium lysed before YBD-affected coral tissues displayed physical symptoms of the disease. The dominant clade A signature in these DD samples could be remnants of lysed cells. Alternatively, certain clade A genotypes have been present during or colonized coral polyps after stress events (Rodríguez-Román et al., 2006; Stat et al., 2008; DeSalvo et al., 2010).

Microbial interactions may be shaping Symbiodinium species composition or alternatively, Symbiodinium may affect the bacterial communities (Bourne et al., 2013). We recorded diverse Symbiodinium assemblages in the samples from the diseased colonies, which may represent shifting communities. Our sample size and genotyping were too limited to provide conclusive evidence to support this hypothesis. However, our observations suggest that it would be worthwhile to further investigate how disease and microbial interactions impact coral–Symbiodinium assemblages.

Transcriptomic responses under disease & stress

Host genets under healthy and diseased conditions showed distinct transcriptomes. Differences in gene expression reflect the differences between health states. However, in the HD condition, some DEGs responded similarly to DD and some were more similar to the HH response. These results illustrated that the HD condition is not always defined by intermediate expression.

The clearly distinct DEG profiles for HH and DD showed that corals exhibit an extreme cellular response under YDB. For instance, respiration is reduced as mitochondrial ATP synthase-coupling factor 6 and other mitochondrial-associated genes appear to be suppressed once the disease manifests into a lesion (Supplementary Table 1). In addition, specific functional genes are differentially expressed between health conditions. Equinatoxin-5 (CCHW6675), a protein involved with pore-formation found in nematocysts of cnidarians (Anderluh et al., 1999), is downregulated in DD. This protein has also been proposed as a precursor to the antimicrobial peptides of the magainin and dermaseptin families (Pungercar et al., 1997). The suppression of Equinatoxin-5 would leave the coral-host with reduced defense mechanisms. CCHW7708, small cysteine-rich protein 1 (SCRiP1), is also strongly suppressed in DD samples. SCRiP1 is part of the SCRiP gene family, originally uncovered in O. faveolata, and is the only SCRiP to have a β-defensin domain (Sunagawa et al., 2009a). The reduction of these two distinct antimicrobial peptides could impede the innate immune response that healthy corals would launch at the site of infection. In addition to suppressed defense mechanisms, Transcriptional corepressor tupA (CCHW2534) and Histone H2A.v (AOSF622), which are involved in transcriptional repression and regulation, are strongly downregulated in DD.

Hemicentin-1 is highly upregulated in diseased samples. Hemicentin-1 is part of the immunoglobin superfamily in human (Vogel and Hedgecock, 2001) and involved in immune response as well as stabilization of the germline syncytium in C. elegans (Vogel et al., 2006). Additional immune response proteins, such as tumour-necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 3 (CCHW9787), are strongly upregulated in diseased samples. This protein has been associated with hemorrhage and inflammatory response. Specifically, cyclic AMP-responsive element-binding protein 1 has been associated with hypoxia-induced inflammatory processes (Comerford et al., 2003) and is upregulated in DD. PHD finger protein 21A (CCHW7679) inhibits transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter and the transcription factor ETV6 (CCHW7961) is a transcriptional repressor. Both were strongly upregulated in DD.

Strong mitochondrial suppression suggests that nutrients, which may have been provided by beneficial microbes are no longer available. Nor did the host invest in energy production. Although immune and inflammatory responses (also observed in coral bleaching studies) were identified, we did not detect differential expression of reactive oxygen species or heat shock proteins genes that appear in temperature stress studies (Barshis et al., 2013; DeSalvo et al., 2008, 2010, 2012).

HD as an intermediate health state

These results showed that HD is an intermediate health state, which is distinct and potentially transitional. While HD appeared visually healthy, bacterial richness was threefold higher than in HH. This may be explained by the Intermediate Disturbance Hypothesis (Connell, 1978), where maximum species diversity is postulated to exist at intermediate regimes of disturbance. Although originally proposed for plant and animal diversity, our results suggest this may occur in microbial systems as well. Transcriptional changes indicate that the coral responds to disease, even in areas where the diseased colony does not exhibit signs of disease. A systemic response in colonies with YBD was also observed by Mydlarz et al. (2009); higher lysozyme-like and antibacterial enzymatic activity was measured in both healthy-appearing and diseased tissue. We measured a systemic response in diseased colonies by the change in DEGs. Some FC values were higher in HD than in DD, suggesting that certain unannotated genes have a larger role in the host transcriptome during this intermediate health state. Variance was higher for the HD sample set likely owing to sampling a less defined area. Together, a distinct DEG profile, Symbiodinium population and bacterial community structure defined HD as an intermediate health state in the progression of YBD.

Conclusions

Coral colonies are complex microbial ecosystems that can now be examined experimentally through the lens of high throughput tools as those described herein.

This study assessed the health state of coral colonies using two microarray technologies. Differences were distinguished in both the host transcriptome response and associated microbial communities. We used three conditions to examine a spectrum of health states and determine factors in the YBD progression. The HD condition was a distinct health state, where the associated bacterial community was mostly composed of the diversity associated with HH as well as DD, and host gene expression levels were also intermediate. This intermediate profile revealed that the entire colony responds to the disease, even though the HD tissue is visually indistinguishable from healthy tissue.

The molecular signatures highlighted in this study provide a basis for future studies of YBD and other coral diseases to assess disease beyond phenotypic appearance. Future studies should use consistent collecting methods. In particular, samples from the HD condition have proven to be valuable. With comparative methods and further attention to intermediate heath states, we will learn more about coral health, disease dynamics and subsequent changes in the coral holobiont.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología (ICML), the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México for providing facilities and collection permits. Additionally we would like to thank those at the ICML, as well as the Medina & Andersen Lab members who provided assistance in collecting the sample, and in experimental and analytical methods. Especially, Adan Guillermo Jordán-Garza, Julia Schnetzer and Erika M Diaz-Almeyda for helping with the sample collection. Nicholas R Polato & Elizabeth Green for genotyping coral colonies. Lauren M Tom for assistance with the analyses. Justin L Matthews for statistical input. Bishoy SK Kamel and Erika M Diaz-Almeyda for additional draft comments. This study was supported by NSF awards IOS 0644438 and IOS 0926906 from NSF to MM.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

Supplementary Material

References

- Ainsworth TD, Vega Thurber R, Gates R. The future of coral reefs: a microbial perspective. Trends Ecol Evol. 2009;25:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alagely A, Krediet CJ, Ritchie KB, Teplitski M. Signaling-mediated cross-talk modulates swarming and biofilm formation in a coral pathogen Serratia marcescens. ISME J. 2011;5:1609–1620. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderluh G, Krizaj I, Strukelj B, Gubensek F, Macek P, Pungercar J. Equinatoxins, pore-forming proteins from the sea anemone Actinia equina, belong to a multigene family. Toxicon. 1999;37:1391–1401. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(99)00082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranda M, Banaszak AT, Bayer T, Luyten JR, Medina M, Voolstra CR. Differential sensitivity of coral larvae to natural levels of ultraviolet radiation during the onset of larval competence. Mol Ecol. 2011;20:2955–2972. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barshis DJ, Ladner JT, Oliver TA, Seneca FO, Traylor-Knowles N, Palumbi SR. From the cover: genomic basis for coral resilience to climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:1387–1392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210224110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellantuono AJ, Granados-Cifuentes C, Miller DJ, Hoegh-Guldberg O, Rodriguez-Lanetty M. Coral thermal tolerance: tuning gene expression to resist thermal stress. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne DG, Dennis PG, Uthicke S, Soo RM, Tyson GW, Webster N. Coral reef invertebrate microbiomes correlate with the presence of photosymbionts. ISME J. 2013;7:1452–1458. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne DG, Garren M, Work T, Rosenberg E, Smith G, Harvell CD. Microbial disease and the coral holobiont. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:554–562. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt ME, McManus J. Disease incidence is related to bleaching extent in reef-building corals. Ecology. 2009;90:2859–2861. doi: 10.1890/08-0445.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie EL, DeSantis TZ, Joyner D, Joyner DC, Baek SM, Larsen JT, et al. Application of a high-density oligonucleotide microarray approach to study bacterial population dynamics during uranium reduction and reoxidation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:6288–6298. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00246-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner AW, Bruckner RJ. Consequences of yellow band disease (YBD) on Montastraea annularis (species complex) populations on remote reefs off Mona Island, Puerto Rico. Dis Aquat Org. 2006;69:67–73. doi: 10.3354/dao069067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno JF, Petes LE, Harvell CD, Hettinger A. Nutrient enrichment can increase the severity of coral diseases. Ecol Lett. 2003;6:1056–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno JF, Selig ER, Casey KS, Page CA, Willis BL, Harvell CD, et al. Thermal stress and coral cover as drivers of coral disease outbreaks. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd AF, Fukami H, Smith ND, Knowlton N. Taxonomic classification of the reef coral family Mussidae (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Scleractinia) Zoolog J Linn Soc. 2012;166:465–529. [Google Scholar]

- Cervino JM, Goreau T, Nagelkerken I, Smith G, Hayes R. Yellow band and dark spot syndromes in Caribbean corals: distribution, rate of spread, cytology, and effects on abundance and division rate of zooxanthellae. Hydrobiologia. 2001;460:53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cervino JM, Hayes R, Polson S. Relationship of Vibrio species infection and elevated temperatures to yellow blotch/band disease in Caribbean corals. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:6855–6864. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6855-6864.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervino JM, Thompson F, Gomez-Gil B, Lorence E, Goreau T, Hayes R, et al. The Vibrio core group induces yellow band disease in Caribbean and Indo-Pacific reef-building corals. J Appl Micro. 2008;105:1658–1671. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimetto LA, Brocchi M, Thompson CC, Martins RCR, Ramos HR, Thompson FL. Vibrios dominate as culturable nitrogen-fixing bacteria of the Brazilian coral Mussismilia hispida. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2008;31:312–319. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comerford KM, Leonard MO, Karhausen J, Carey R, Colgan SP, Taylor CT. Small ubiquitin-related modifier-1 modification mediates resolution of CREB-dependent responses to hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:986–991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337412100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell JH. Diversity in tropical rain forests and coral reefs. Science. 1978;199:1302–1310. doi: 10.1126/science.199.4335.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EK, Stagaman K, Dethlefsen L, Bohannan BJM, Relman DA. The application of ecological theory toward an understanding of the human microbiome. Science. 2012;336:1255–1262. doi: 10.1126/science.1224203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cróquer A, Bastidas C, Elliott A, Sweet M. Bacterial assemblages shifts from healthy to yellow band disease states in the dominant reef coral Montastraea faveolata. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2013;5:90–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2012.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunning J, Thurmond J, Smith G, Weil E, Ritchie KB. A survey of Vibrios associated with healthy and Yellow Band Diseased Montastraea faveolata. Proc 11th Intl Coral Reef Symp. 2009;7:206–210. [Google Scholar]

- Davies SW, Rahman M, Meyer E, Green EA, Buschiazzo E, Medina M, et al. Novel polymorphic microsatellite markers for population genetics of the endangered Caribbean star coral, Montastraea faveolata. Mar Biodiv. 2013;43:167–172. [Google Scholar]

- DeSalvo MK, Estrada A, Sunagawa S, Medina M. Transcriptomic responses to darkness stress point to common coral bleaching mechanisms. Coral Reefs. 2012;31:215–228. [Google Scholar]

- DeSalvo MK, Sunagawa S, Fisher PL, Voolstra CR, Iglesias-Prieto R, Medina M. Coral host transcriptomic states are correlated with. Mol Ecol. 2010;19:1174–1186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSalvo MK, Voolstra CR, Sunagawa S, Schwarz JA, Stillman J, Coffroth M, et al. Differential gene expression during thermal stress and bleaching in the Caribbean coral Montastraea faveolata. Mol Ecol. 2008;17:3952. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas AE. Nutritional interactions in insect-microbial symbioses: aphids and their symbiotic bacteria buchnera. Annu Rev Entomol. 1998;43:17–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.43.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dustan P. Vitality of reef coral populations off Key Largo, Florida: recruitment and mortality. Environ Geol. 1977;2:51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner T, Côté I, Gill J, Grant A, Watkinson A. Long-term region-wide declines in Caribbean corals. Science. 2003;301:958. doi: 10.1126/science.1086050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garren M, Walsh SM, Caccone A, Knowlton N. Patterns of association between Symbiodinium and members of the Montastraea annularis species complex on spatial scales ranging from within colonies to between geographic regions. Coral Reefs. 2006;25:503–512. [Google Scholar]

- Hazen TC, Dubinsky EA, DeSantis TZ, Andersen GL, Piceno YM, Singh N, et al. Deep-sea oil plume enriches indigenous oil-degrading bacteria. Science. 2010;330:204–208. doi: 10.1126/science.1195979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TP, Graham NAJ, Jackson JBC, Mumby PJ, Steneck RS. Rising to the challenge of sustaining coral reef resilience. Trends Ecol Evol. 2010;25:633–642. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniewska P, Campbell PR, Kline DI, Rodriguez-Lanetty M, Miller DJ, Dove S, et al. Major cellular and physiological impacts of ocean acidification on a reef building coral. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg CA, Piceno YM, Tom LM, DeSantis TZ, Zawada DG, Andersen GL. PhyloChip microarray comparison of sampling methods used for coral microbial ecology. J Microbiol Methods. 2012;88:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimes NE, Van Nostrand JD, Weil E, Zhou J, Morris PJ. Microbial functional structure of Montastraea faveolata, an important Caribbean reef-building coral, differs between healthy and yellow-band diseased colonies. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:541–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton N, Jackson JBC. Shifting baselines, local impacts, and global change on coral reefs. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e54. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig JE, Bourne DG, Curtis B, Dlutek M, Stokes HW, Doolittle WF, et al. Coral-mucus-associated Vibrio integrons in the Great Barrier Reef: genomic hotspots for environmental adaptation. ISME J. 2011;5:962–972. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krediet CJ, Ritchie KB, Paul VJ, Teplitski M. Coral-associated micro-organisms and their roles in promoting coral health and thwarting diseases. Proc Biol Sci. 2013;280:20122328. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lema KA, Willis BL, Bourne DG. Corals form characteristic associations with symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:3136–3144. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07800-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesser MP, Mazel C, Gorbunov M, Falkowski P. Discovery of symbiotic nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria in corals. Science. 2004;305:997. doi: 10.1126/science.1099128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes R, Kruijt M, De Bruijn I, Dekkers E, Van Der Voort M, Schneider JHM, et al. Deciphering the rhizosphere microbiome for disease-suppressive bacteria. Science. 2011;332:1097–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1203980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouchka ME, Hewson I, Harvell CD. Coral-associated bacterial assemblages: current knowledge and the potential for climate-driven impacts. Integr Comp Biol. 2010;50:662–674. doi: 10.1093/icb/icq061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscatine L, Porter JW. Reef corals: mutualistic symbioses adapted to nutrient-poor environments. BioScience. 1977;27:454–460. [Google Scholar]

- Mydlarz LD, Couch CS, Weil E, Smith G, Harvell CD. Immune defenses of healthy, bleached and diseased Montastraea faveolata during a natural bleaching event. Dis Aquat Organ. 2009;87:67–78. doi: 10.3354/dao02088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandolfi JM, Bradbury RH, Sala E, Hughes TP, Bjorndal KA, Cooke RG, et al. Global trajectories of the long-term decline of coral reef ecosystems. Science. 2003;301:955–958. doi: 10.1126/science.1085706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock FJ, Morris PJ, Willis BL, Bourne DG. The urgent need for robust coral disease diagnostics. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002183. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portune KJ, Voolstra CR, Medina M, Szmant AM. Development and heat stress-induced transcriptomic changes during embryogenesis of the scleractinian coral Acropora palmata. Mar Genomics. 2010;3:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.margen.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pungercar J, Anderluh G, Macek P, Gubensek F, Strukelj B. Sequence analysis of the cDNA encoding the precursor of equinatoxin V, a newly discovered hemolysin from the sea anemone Actinia equina. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1341:105–107. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(97)00083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R: a Language And Environment For Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves L. Newly discovered: yellow band disease strikes keys reefs. Underwater USA. 1994;11:16. [Google Scholar]

- Richards Dona A, Cervino JM, Karachun V, Lorence E, Bartels E, Hughen K, et al. Coral yellow band disease; current status in the caribbean, and links to new indo-pacific outbreaks. Proc 11th Intl Coral Reef Symp. 2008. pp. 1–5.

- Richardson LL. Coral diseases: what is really known. Trends Ecol Evol. 1998;13:438–443. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01460-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie KB. Regulation of microbial populations by coral surface mucus and mucus-associated bacteria. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2006;322:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Roder C, Arif C, Bayer T, Aranda M, Daniels C, Shibl A, et al. Bacterial profiling of White Plague Disease in a comparative coral species framework. ISME J. 2014;8:31–39. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Román A, Hernández-Pech X, Thomé P, Enríquez S, Iglesias-Prieto R. Photosynthesis and light utilization in the Caribbean coral Montastraea faveolata recovering from a bleaching event. Limnology and Oceanography. 2006;51:5702–2710. [Google Scholar]

- Rohwer F, Breitbart M, Jara J, Azam F, Knowlton N. Diversity of bacteria associated with the Caribbean coral Montastraea franksi. Coral reefs. 2001;20:85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Rohwer F, Seguritan V, Azam F, Knowlton N. Diversity and distribution of coral-associated bacteria. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2002;243:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rowan R, Knowlton N. Intraspecific diversity and ecological zonation in coral-algal symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2850–2853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan R, Powers DA. Molecular genetic identification of symbiotic dinoflagellates(zooxanthellae) Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1991;71:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed A, Sharov V, White J, Li J, Liang W, Bhagabati N, et al. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques. 2003;34:374–378. doi: 10.2144/03342mt01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekar R, Kaczmarsky LT, Richardson LL. Effect of freezing on PCR amplification of 16S rRNA genes from microbes associated with black band disease of corals. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:2581–2584. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01500-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3:1–25. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stat M, Morris E, Gates RD. Functional diversity in coral–dinoflagellate symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9256–9261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801328105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunagawa S, DeSalvo MK, Voolstra CR, Reyes-Bermudez A, Medina M. Identification and gene expression analysis of a taxonomically restricted cysteine-rich protein family in reef-building corals. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunagawa S, DeSantis TZ, Piceno YM, Brodie EL, DeSalvo MK, Voolstra CR, et al. Bacterial diversity and White Plague Disease-associated community changes in the Caribbean coral Montastraea faveolata. ISME J. 2009;3:512–521. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunagawa S, Woodley C, Medina M. Threatened corals provide underexplored microbial habitats. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland K, Porter JW, Torres C. Disease and immunity in Caribbean and Indo-Pacific zooxanthellate corals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2004;266:273–302. [Google Scholar]

- Thornhill DJ, Doubleday K, Kemp DW, Santos SR. Host hybridization alters specificity of cnidarian–dinoflagellate associations. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2010;420:113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Thornhill DJ, Lewis AM, Wham DC, Lajeunesse TC. Host-specialist lineages dominate the adaptive radiation of reef coral endosymbionts. Evolution. 2013;68:352–367. doi: 10.1111/evo.12270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trench RK. The cell biology of plant-animal symbiosis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1979;30:485–531. [Google Scholar]

- Vega Thurber R, Willner-Hall D, Rodriguez-Mueller B, Desnues C, Edwards RA, Angly F, et al. Metagenomic analysis of stressed coral holobionts. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:2148–2163. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel BE, Hedgecock EM. Hemicentin, a conserved extracellular member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, organizes epithelial and other cell attachments into oriented line- shaped junctions. Development. 2001;128:883–894. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.6.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel BE, Muriel JM, Dong C, Xu X. Hemicentins: what have we learned from worms. Cell Res. 2006;16:872–878. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voolstra CR, Schnetzer J, Peshkin L, Randall CJ, Szmant AM, Medina M. Effects of temperature on gene expression in embryos of the coral Montastraea faveolata. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:627. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voolstra CR, Schwarz JA, Schnetzer J, Sunagawa S, DeSalvo MK, Szmant AM, et al. The host transcriptome remains unaltered during the establishment of coral-algal symbioses. Mol Ecol. 2009;18:1823–1833. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegley L, Edwards R, Rodriguez-Brito B, Liu H, Rohwer F. Metagenomic analysis of the microbial community associated with the coral Porites astreoides. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:2707–2719. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil E, Smith GW, Gil-Agudelo DL. Status and progress in coral reef disease research. Dis Aquat Organ. 2006;69:1–7. doi: 10.3354/dao069001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson C. Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 2008. Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network and Reef and Rainforest Research Centre: Townsville, Australia; 2008. pp. 1–304. [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Sercu B, Van De Werfhorst L, Wong J, DeSantis TZ, Brodie EL, et al. Characterization of coastal urban watershed bacterial communities leads to alternative community-based indicators. PLoS One. 2010;5:1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.