Abstract

mTOR (the mechanistic target of rapamycin) is an atypical serine/threonine kinase involved in regulating major cellular functions including growth and proliferation. Deregulations of the mTOR signaling pathway is one of the most commonly observed pathological alterations in human cancers. To this end, oncogenic activation of the mTOR signaling pathway contributes to cancer cell growth, proliferation and survival, highlighting the potential for targeting the oncogenic mTOR pathway members as an effective anti-cancer strategy. In order to do so, a thorough understanding of the physiological roles of key mTOR signaling pathway components and upstream regulators would guide future targeted therapies. Thus, in this review, we summarize available genetic mouse models for mTORC1 and mTORC2 components, as well as characterized mTOR upstream regulators and downstream targets, and assign a potential oncogenic or tumor suppressive role for each evaluated molecule. Together, our work will not only facilitate the current understanding of mTOR biology and possible future research directions, but more importantly, provide a molecular basis for targeted therapies aiming at key oncogenic members along the mTOR signaling pathway.

Keywords: mTORC2, mTORC1, mTOR pathway, mouse model, tumorigenesis

Introduction

Rapamycin is an immune-suppressant drug extracted from a bacterial strain isolated on the Easter Island [1]. In 1991, a genetic screen for rapamycin-resistant mutations in budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae led to the discovery of both TOR1 and TOR2 genes [2], the yeast homologues of mammalian mTOR. Subsequent biochemical studies in mammalian cells further led to the identification of a ~290 kDa protein, which was termed mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin, also known as the mammalian target of rapamycin) [3–5]. mTOR is an atypical serine/threonine kinase that belongs to the PIKK (phosphoinositide 3-kinase related protein kinase) super-family, which includes multiple members of large-size kinase proteins that are involved in nutrient sensing (mTOR) and DNA repair [ATM (ataxia-telangiectasia mutated), ATR (ataxia-telangiectasia and Rad3-related) and DNAPK (DNA-dependent protein kinase)] [6].

In yeast, two TOR genes have been identified and termed as TOR1 and TOR2, both of which participate in two separate protein complexes TORC1 and TORC2, respectively [7]. Notably, both TOR1 and TOR2 are found in the TORC1 complex that mainly regulates cell growth; whereas only TOR2 is found in the TORC2 complex, which is important for cell cycle-dependent polarization of the actin cytoskeleton [8]. On the other hand, in mammalian cells, there is only one mTOR gene identified thus far [3, 4]. Furthermore, as an evolutionarily conserved kinase, mTOR functions largely as the catalytic subunit of two distinct protein kinase complexes, designated as mTORC1 (mTOR complex 1) and mTORC2 (mTOR complex 2), respectively [9].

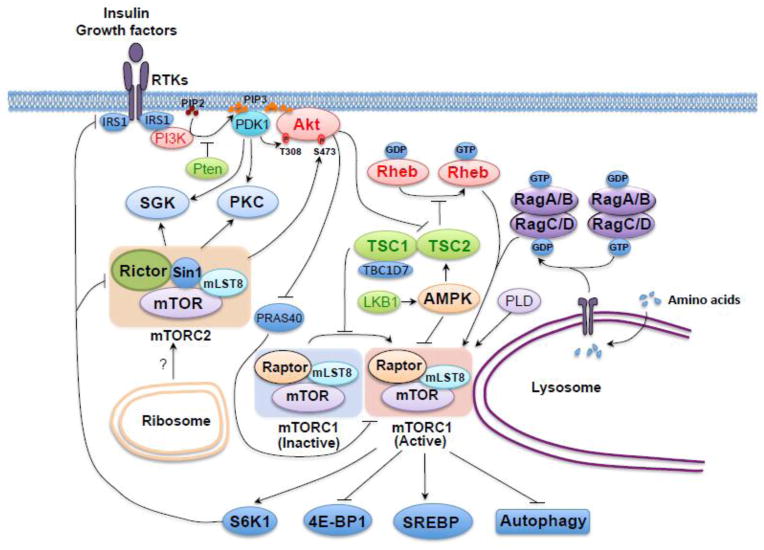

Both mTORC1 and mTORC2 complexes share common subunits including mTOR and mLST8 (mammalian lethal with sec-13 protein 8, also known as GβL) [10–12], whereas mTORC1 contains its unique subunit, Raptor (regulator-associated protein of mammalian target of rapamycin), and the specific components including Rictor (rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR) and mSin1 (mammalian stress-activated map kinase-interacting protein 1, also termed MAPKAP1) define mTORC2 [13–16] (Figure 1). Critically, both Raptor and Rictor serve as scaffolding proteins to regulate the assembly, localization and substrate binding of mTORC1 and mTORC2, respectively [17]. However, it appears that mLST8 is essential for the mTOR/Rictor, but not the mTOR/Raptor interaction, while the underlying molecular mechanism is not fully understood [18]. Sin1 is also considered as a scaffolding protein regulating the assembly and activity of mTORC2 [15, 19, 20], while the detailed complex organization remains largely elusive in part due to the lack of structural evidence for the mTORC2 holo-enzyme. Furthermore, other additional regulatory components have also been reported to be involved in mTOR complex function [17]. For example, DEPTOR (DEP domain containing mTOR-interacting protein) acts as an endogenous mTOR inhibitor that expresses at low levels in most cancers [21]. Unlike DEPTOR, which inhibits both mTORC1 and mTORC2, PRAS40 (proline-rich Akt substrate 40 kDa) binds the mTOR kinase domain in a phosphorylation-dependent manner and only suppresses the kinase activity of mTORC1 [22, 23]. On the other hand, Protor1/2 (protein observed with Rictor 1 and 2) binds Rictor, and is only present in mTORC2, to increase the mTORC2-mediated activation of SGK-1 (serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase-1) [24, 25].

Figure 1.

A schematic illustration of the mTOR signaling pathway, including major upstream regulators and downstream substrates for both the mTORC2 and mTORC1 kinase complexes. The major mTORC1 upstream regulators include Rheb, TSC1/2, AMPK, Rag and Akt. When activated at the lysosome membrane, mTORC1 directly phosphorylates 4E-BP1, S6K, SREBP and certain autophagy components, which exert their functions to modulate protein synthesis, lipid and lysosome biosynthesis, energy metabolism and autophagy. On the other hand, relatively little is known about the upstream regulators of mTORC2, although it is well established that mTORC2 is sensitive to growth factors. The downstream targets of mTORC2 are AGC family of kinases, including Akt, SGK and PKC, which regulate the cytoskeleton polarization and cell survival /metabolism. The mTOR pathway components with established mouse models are marked in bold. Oncogenic proteins in this pathway are labeled in red color, while tumor suppressors are labeled in green.

The mTOR signaling pathway is pivotal in regulating major cell functions including cell growth, proliferation and metabolism [17]. To this end, mTORC1 and mTORC2 have been shown to play critical yet functionally distinct roles in controlling different cellular processes. Specifically, mTORC1 largely regulates protein translation and cell metabolism through sensing intra-cellular as well as extra-cellular stimuli, such as stress, nutrients, energy, oxygen levels and growth factors [7, 17]. In addition, it also directly phosphorylates many downstream targets including 4E-BP1 (eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1), S6K (S6 kinase), SREBP (sterol regulatory element-binding protein) and autophagy components to promote protein and lipid synthesis, lysosome biogenesis, energy metabolism and to inhibit autophagy [17]. On the other hand, mTORC2 is less sensitive to nutrients but largely responsive to extra-cellular growth factors [13, 14]. However, the exact molecular mechanism for how mTORC2 senses extra-cellular growth factor stimulation is still largely unclear, while the only available knowledge is that ribosome association of mTORC2 is critical for its activation [17]. Nonetheless, once mTORC2 is activated, it phosphorylates major downstream target proteins including AGC family of kinases, such as Akt, SGK and PKC (protein kinase C) [26] to further augment the kinase cascade to exert their cellular functions.

Consistent with a critical role in regulating cell growth and metabolism, deregulation of the mTOR signaling is commonly observed in human cancers [27–29]. To this end, mutations or loss-of-function of upstream regulator genes such as TSC1/2 (tuberous sclerosis complex 1/2) or LKB1 (liver kinase B1) have been closely linked to clinical tumor syndromes including the Tuberous Sclerosis complex and the Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, respectively [30, 31]. More importantly, hyper-activation of PI3K and Akt, or genetic loss or mutation of PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue), a negative suppressor of the PI3K signaling, have been observed in many types of human cancers [32]. Given that hyper-activation of the mTOR pathway in cancer contributes significantly to cancer initiation and development, targeting the oncogenic mTOR pathway components could potentially be an effective cancer treatment strategy [17]. In fact, FDA (Food and Drug Administration) has approved rapamycin and its analogs Temsirolimus and Everolimus for the treatments of certain types of tumors including renal cell carcinoma and mantle cell lymphoma [33]. However, considering rapamycin and its analogs have only reached modest efficacy in current clinical trials, an in-depth further understanding of the molecular mechanisms for the mTOR signaling pathway, as well as identifying new therapeutic targets along this signaling cascade may provide fruitful targets for cancer therapy [17, 34].

Thus in this review, we summarize the available genetic mouse models for both the mTORC1 and mTORC2 complexes. Furthermore, we also explore their upstream regulators or downstream targets to define a clear functional role for these critical molecules in their physiological settings as well as in tumorigenesis, which will provide insights for further speculations regarding whether they are potential drug targets for effective cancer treatment.

1. The roles of the mTOR signaling pathway components in tumorigenesis: revealed by mouse models

1.1 Shared components for the mTORC1 and mTORC2 complexes

1.1.1. mTOR

In an effort to elucidate the physiological function of mTOR, two groups independently generated the mTOR−/− mice in 2006 and found that loss of mTOR leads to embryonic lethality at the E5.5–6.5 stage in part due to impaired cell proliferation and gastrulation [35, 36]. Whereas, mTOR+/− mice develop normally and do not show any overt development defects [35, 36]. Interestingly, the mTORH/H (hypomorphic mTOR) mice, which are viable and only express 25% of total mTOR levels compared to wild-type mice, show an approximately 20% increase in lifespan, indicating that inhibiting mTOR may lead to a prolonged lifespan [37]. In order to identify the physiological function of mTOR in various tissues, an mTOR conditional KO (knockout) mouse model was generated to specifically ablate the mTOR gene in muscle (Figure 2). These mice display severe myopathy and premature death due to impaired oxidative metabolism and glycogen accumulation [38], further indicating a critical role for mTOR in regulating the development and metabolism processes.

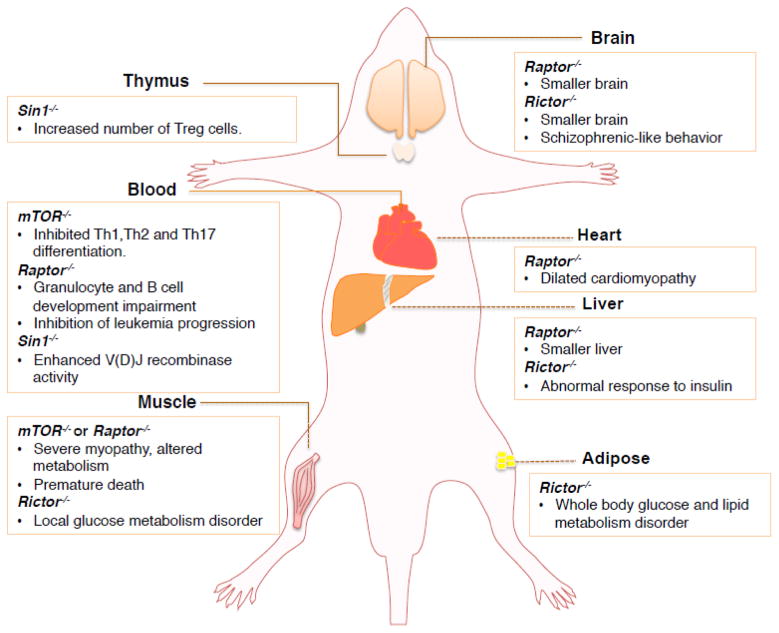

Figure 2.

A schematic illustration of various tissue-specific knockout mouse models for the indicated critical mTOR signaling components. Please note that certain cell type-specific knockout mouse models are not included in this figure.

1.1.2. mLST8 (GβL)

The mLST8−/− mice die around E10.5 in part due to defects in vascular development [18]. Unexpectedly, although mLST8 participates in both mTORC1 and mTORC2 complexes, the mLST8−/− mice showed deficiency largely in mTORC2, but not mTORC1, related functions [18]. Consistently, mLST8−/− MEFs (mouse embryonic fibroblasts) showed impaired Akt and PKCα phosphorylation, with unaffected S6K phosphorylation [18]. Mechanistically, biochemical studies demonstrated that mLST8 is functionally required for the mTOR/Rictor interaction but not the mTOR/Raptor interaction, which supports the notion that mLST8 genetic ablation only affects mTORC2 but not mTORC1 signaling [18]. However, additional in-depth studies are required to understand the underlying molecular mechanism for the different roles of mLST8 in governing the activation of mTORC1 versus mTORC2 kinase complex.

1.2 mTORC1 specific components

1.2.1 Raptor

Raptor−/− mice are embryonic lethal and die at E5.5–6.5, due to blastocysts failure for expansion and differentiation [18]. Considering the essential role for Raptor in maintaining mTORC1 complex organization and function, several tissue-specific Raptor KO (knockout) mice also showed the phenotypes similar to a deficiency in mTORC1 function. Specifically, the adipose-specific Raptor KO mice have much less adipose tissue, and are less likely to get hyper-cholesterolemia and obesity, which emphasizes the critical role of Raptor and mTORC1 in adipose metabolism and whole body energy homeostasis [39] (Figure 2). Furthermore, the skeletal muscle-specific Raptor KO mice exhibit severe muscle dystrophy, with little or no fat underneath skin, eventually leading to premature death [40]. Similarly, heart-specific Raptor KO mice die from heart failure five weeks after tamoxifen-inducted genetic ablation of Raptor, likely caused by the lack of adaptive cardiomyocyte growth, as well as increased apoptosis and autophagy in cardiac tissue [41]. Echoing the pivotal role of mTORC1 in development, the central nervous system specific Raptor KO mice slow brain growth starting at E17.5 and die shortly after birth [42]. The only viable Raptor conditional KO mouse model are liver-specific Raptor KO mice, which exhibit 40% smaller liver mass, smaller hepatocyte and less protein content [43], arguing for a critical physiological role of mTORC1 in maintaining protein synthesis and cell growth.

Notably, a tamoxifen (TAM)-inducible conditional Raptor KO mouse model (Raptorfl/fl/CreER+TAM) was generated in 2012, where depletion of Raptor in adult mice with TAM in all tissues caused body weight loss and death within 17 days, with impairment of granulocyte and B cell development in bone marrow [44]. In order to investigate the critical role of Raptor in established acute myeloid leukemia (AML), Raptorfl/fl, Raptor+/+/CreER and Raptorfl/fl/CreER AML mice were generated by transplantation of the MLL-AF9 fusion gene modified hematopoietic progenitor cells from Raptorfl/fl, Raptor+/+/CreER and Raptorfl/fl/CreER mice into lethally irradiated syngeneic recipients [44]. Notably, further analyses of these AML mouse models revealed that Raptor deletion remarkably impaired AML progression owing to an increased induction of cellular apoptosis [44]. Interestingly, although loss of Raptor significantly inhibited AML stem cells initiation, the self-renewal ability for these cells was not affected [44], indicating that mTORC1 activity is essential for AML propagation but not AML stem cell self-renewal.

1.3 mTORC2 specific components

1.3.1 Rictor

Similar to the phenotypes of mLST8−/− mice, the Rictor−/− mice exhibit vascular development defects and die around E10.5–11.5 [18, 45]. Thus, in order to examine the physiological role of Rictor in vivo, various tissue-specific KO mouse models were established in recent years. Specifically, the muscle-specific Rictor KO mice display impaired insulin-stimulated glucose uptake, elevated glycogen synthase activity and mild glucose intolerance, indicating an impairment of the glucose transportation process [46] (Figure 2). Similar to muscle-specific Rictor KO mice, the liver-specific Rictor KO mice and the fat-cell specific Rictor KO mice also show defects in glucose metabolism [47, 48]. Furthermore, compared to their wild-type littermates, neuron-specific Rictor KO mice exhibit a reduction in brain size, neuron cell size as well as whole-body size [49]. These mice also displayed a Schizophrenic-like behavior according to the results from an independent behavior study [50]. Interestingly, a recent study revealed that the lifespan of male, but not female mice, was significantly decreased in Rictor+/−, liver-specific Rictor−/− mice or Rictorfl/fl/Cre mice, indicating the association of Rictor with aging in a gender-dependent manner [51]. However, the underlying molecular mechanism(s) driving this difference remains elusive and thus warrant further in-depth investigations.

Rictor has also been tightly linked with tumorignesis according to results obtained from the Sabatini group [52]. By crossing the Pten+/− mice with mTOR+/−, Rictor+/−, Raptor+/− or mLST8+/− mice, and monitoring the cancerous phenotypes of their off-springs, they found that both the Pten+/−/mTOR+/−and Pten+/−/mLST8+/−mice exhibit a longer lifespan than Pten+/−counterparts. More importantly, compared with Pten+/− mice that develop spontaneous cancers in multiply organs, the Pten+/−/Rictor+/− mice exhibit less prostate tumor incidences, less severe lesions and a longer lifespan [52]. Given the fact that Rictor is a haplo-insufficient gene, this study supports the notion that mTORC2 signaling is required for the development of Pten heterozygous-induced prostate cancer [52]. Hence, developing specific inhibitors for mTORC2 may represent a potential novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of cancer patients, especially in the patient population with Pten loss.

1.3.2 Sin1 (MAPKAP1)

Functioning as another essential and unique mTORC2 subunit, the critical role of Sin1 in maintaining mTORC2 complex integrity and activity was first evaluated by three independent groups in 2006 [15, 16, 19]. The Sin1−/− mice are embryonic lethal and die between E10.5~15.5, in part due to defects in embryonic cardiovascular development [53]. Furthermore, ablation of Sin1 in B cells leads to an increase in V(D)J recombinase enzymatic activity and enhanced pro-B cell survival, resulting from elevated IL-7R and RAG1/2 gene expression [53] (Figure 2). Moreover, Sin1 deficiency was found to result in an increase in the number of T-regulatory cells in the thymus. This deficiency, however, has no affect on the growth and proliferation of T cells [54], further supporting a critical role for Sin1 in regulating immune response through modulating both B and T cell respiratories. However, the physiological role of Sin1 in contributing to tumorigenesis remains unclear. Therefore, it will be important to develop additional Sin1 tissue-specific KO or Transgenic (Tg) mice as well as various compound mouse models such as crossing Sin1 conditional KO mice with Pten+/− mice to fully understand the critical role of Sin1 in tumorigenesis.

1.4 mTORC1 upstream regulators

1.4.1. TSC1/2

The TSC complex is generally considered as a heterodimer formed by TSC1 (also named hamartin) and TSC2 (also termed as tuberin) [55]. Recent studies also revealed TBC1D7 (tre2-bub2-cdc16 1 domain family, member 7) as a third subunit of the TSC complex [56]. However, TBC1D7 gene mutations are not commonly observed in TSC patients [56], suggesting that it might not be an essential component. Under physiological stimulation triggered by amino acids, growth factors, stress, energy as well as oxygen, TSC2 is phosphorylated by various upstream kinases including Akt [57], ERK [58] or RSK [59], to release its inhibition as a GAP (GTPase-activating protein) for the Rheb (ras homolog enriched in brain) GTPase, and to convert Rheb to its active GTP-bound form for mTORC1 activation [17]. Meanwhile, Akt-mediated phosphorylation of TSC2 also results in the dissociation of the TSC complex from the lysosome and subsequent activation of mTORC1 [60]. On the other hand, AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase) can phosphorylate TSC2, leading to its potent suppression of mTORC1 under energy deprivation conditions [61]. In addition to phosphorylation-mediated regulation of mTORC1 activation, a recent study from the Sabatini group, also revealed an amino acid-mediated and a Rag-dependent “inside-out” mTORC1 activation mechanism [62]. Specifically, changes in lysosomal amino acid levels may guide the Rag proteins to release the TSC1/2 complex from the lysosome, as well as to recruit mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface for activation [62, 63].

Notably, Tuberous Sclerosis is an autosomal dominant genetic disease defined by mutations of either TSC1 or TSC2, and is characterized by the formation of hamartomas in the brain, skin, kidneys, lungs, eyes and heart [30]. Pathologically, loss of heterozygosity of either TSC1 or TSC2 gene has been found in many TSC patients and shown to be a driving-force for the disease [64]. However, no particular hot-spot mutations of TSC1 or TSC2 have been identified [30], highlighting a possible tumor suppressor role for TSC1 or TSC2.

The phenotypes of TSC1/2 KO mice are summarized in Table 2. Notably, multiple mouse models clearly support the notion that both TSC1 and TSC2 function as tumor suppressors. Specifically, Tsc1−/− mice die around E10.5–11.5 due to failed closure of the neural tube, while 64% of Tsc1+/− mice develop renal tumors and 71% of Tsc1+/− mice develop liver hemangiomas by 15–18 months [65]. In addition, Tsc2−/− mice die at E9.5–12.5 from hepatic hypoplasia, while Tsc2+/− mice display a 100% incidence of multiple bilateral renal tumors, 50% incidence of liver hemangiomas and a 32% incidence of lung adenomas by 15 months [66]. Another independent study generated Tsc1+/− mice in different genetic backgrounds and reported that 95% of Tsc1+/− C3H mice develop macroscopically visible renal tumors, while 80% of Tsc1+/− mice exhibit renal cell carcinomas at the age of 15–18 months [67]. Furthermore, extra-renal tumor lesions in liver, spleen and uterine were also observed in both C3H and Balb/c mice [67]. Taken together, these mouse models strongly support TSC2 and TSC1 as physiological tumor suppressors.

Table 2.

Major physiological functions of the mTORC1 upstream regulator.

| mTORC1 upstream regulators | Mouse models | Major phenotypes | Putative roles in tumorigenesis | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knockout (KO) | Transgenic (Tg) | ||||

| TSC1 | Tsc1−/− | Embryonic lethal at E10.5–11.5 | Tumor suppressor | [65, 108] | |

| Tsc1+/− | Developed renal tumors and liver hemangiomas at the age of 15–18 months | [67, 108] | |||

| Conditional Tsc1−/− (prostate epithelium) | Developed prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (mPIN) at 6 months stage | [68] | |||

| Conditional Tsc1−/− (liver) | Developed sporadic hepatocellular carcinoma | [69] | |||

| Conditional Tsc1−/− (mammary tissue) | Significantly promoted breast cancer cell growth in vivo | [70] | |||

| Conditional Tsc1−/−Pten−/− (liver) | Exhibited accelerated tumor development and greater tumor numbers | [71] | |||

| Conditional Tsc1−/− (skeletal muscle) | Developed a late-onset myopathy marked with autophagic substrates accumulation | [109] | |||

| Conditional Tsc1−/− (bone marrow) | Showed developmental block of iNKT differentiation | [110] | |||

| Conditional Tsc1−/− (cardiovascular system) | Severe hypertrophy in both ventricles | [111] | |||

| Conditional Tsc1−/− (hypothalamus) | Developed obesity | [112] | |||

| Conditional Tsc1−/− (glia) | Exhibited progressive epilepsy and premature death | [113] | |||

| TSC2 | Tsc2−/− | Embryonic lethal at E9.5–12.5 | Tumor suppressor | [66, 114] | |

| Tsc2+/− | Develops spontaneous tumors in renal, liver and lung at the age of 15 months | [66, 114] | |||

| Tsc2+/− Pten+/− | Showed spontaneous prostate cancer | [73] | |||

| Conditional Tsc2−/− (uterine) | Developed uterine tumor | [72] | |||

| Conditional Tsc2−/− (neuron) | Showed reduced survival rates and enlarged brain and cortical neuron | [115] | |||

| Conditional Tsc2−/− (glia) | Exhibited epilepsy, premature death | [115] | |||

| Rheb | Rheb−/− | Embryonic lethal around mid-gestation | Emerging role as an oncogene | [79] | |

| Rheb1−/− | Embryonic lethal at E10.5~E11.5 stage | [80] | |||

| Rheb2−/− | Without obvious abnormal until adulthood | [80] | |||

| Conditional Rheb1−/− (neural progenitor cell) | Impairment of brain postnatal myelination | [80] | |||

| Conditional Rheb2−/−(liver) | Showed a 2-fold increase of mitochondrial proteins | [81] | |||

| Rheb transgenic lymphoma mice | Promoted lymphoma progression and drug-resistant | [82] | |||

| Rheb transgenic (Pten+/− mice) | Exhibited accelerated prostate cancer progression compared to Pten+/− mice | [83] | |||

| Rag | RagA−/− | Embryonic death at E10.5; loss of mTORC1 activity and severe growth defects | To be determined | [89] | |

| RagB−/− | No overt phenotypes | [89] | |||

| RagA−/−/RagB−/− | Embryonic lethal at E10.5; more robust loss of mTORC1 activity | [89] | |||

| Conditional RagA−/−(heart) | No overt phenotypes | [90] | |||

| Conditional RagB−/−(heart) | No overt phenotypes | [90] | |||

| Conditional RagA−/−/RagB−/− (heart) | Cardiac hypertrophy; defects in autophagy; phenocopies lysosome storage diseases | [90] | |||

| Conditional RagA−/−/RagB−/− (liver) | More robust loss of mTORC1 activity comparing with RagA−/− mice | [89] | |||

| RagA Knock-in mice | Glucose homeostasis defects; autophagy defects; died before postnatal day 1 | [88] | |||

| AMPK | Ampkα1 −/− | Showed increased bone remodeling; decreased fertility function | Context-dependent | [100, 116] | |

| Ampkα2−/− | Dysfunctional glucose metabolism and more likely to development obesity under high-fat diet | [99] | |||

| Ampkβ1−/− | Reduced food intake and protection against diet-induced obesity | [117] | |||

| Ampkβ2−/− | Reduced exercise capacity and promote diet-induced obesity | [118] | |||

| Ampkγ3−/− | Impaired glycogen re-synthesis after exercise | [101] | |||

| Ampkα1−/−/Ampkα2−/− | Embryonic lethal at E10.5 stage | [97] | |||

| Conditional Ampkα1−/− /Ampkα2−/−(muscle) | Showed larger size of myofibers and a higher mass in the biopsy muscle | [98] | |||

| Conditional Ampkβ1−/− /Ampkβ2−/−(muscle) | Physical inactive; reduced mitochandrial content in muscle cells | [102, 119] | |||

| Conditional Ampkα1−/− (Eμ-Myc induced lymphoma) | Showed acceleration of Myc-induced B-cell lymphomagenesis | [105] | |||

Keys: +, wild type allele; −, null allele.

In order to circumvent the embryonic lethality issue for Tsc1/2 homozygous mice, a series of conditional KO mouse models have been further developed. Specifically, prostate epithelium Tsc1 KO mice develop prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia at the age of 6 months, and progress to carcinoma at the age of 16 to 22 months [68]. In another study, liver-specific Tsc1 KO mice manifest spontaneous sporadic hepatocellular carcinoma accompanied with liver inflammation, necrosis and regeneration [69]. Considering that nutrient availability directly regulates TSC1 for mTORC1 activation, this model indicates that activation of mTORC1 might be the bridge between diet and cancer [69]. Furthermore, an inducible Tsc1 deletion system has been recently introduced into mouse primary mammary tumor cells (Tsc1fl/fl/MMTV-PyMT), which demonstrated that deletion of Tsc1 significantly promoted breast cancer cell growth in vivo [70]. In addition, another group further generated and compared the cancerous phenotypes of Tsc1fl/fl/Ptenfl/fl/AlbCre mice with Tsc1fl/fl/AlbCre mice or Ptenfl/fl/AlbCre mice. Notably, the liver of Tsc1fl/fl/Ptenfl/fl/AlbCre mice developed tumors more rapidly and to a greater degree than any other strains, indicating that loss of Tsc1 and Pten may work synergistically in promoting tumorigenesis [71]. On the other hand, the tumor suppressor role of TSC2 is supported by the report that almost all uterine-specific Tsc2−/− mice exhibit uterine leiomyomas at the age of 3 months and myometrial proliferation at the age of 6 months [72]. However, compared with the Pten+/− mice, the Pten+/−/Tsc2+/− mice do not show any advantage in neither promoting prostate adenocarcinoma development nor facilitating tumor progression [73]. This suggests that TSC2 might exert its tumor suppressor function differentially from TSC1, warranting further investigation for the underlying molecular mechanism(s).

1.4.2. Rheb

After establishing TSC1/2 as the upstream negative regulator of mTORC1, studies to determine the molecular link between the TSC complex and the mTORC1 complex subsequently led to the identification of Rheb, a small GTPase [74–76]. Rheb is a member of the Ras superfamily of GTP-binding proteins, with two isoforms (Rheb1 and Rheb2), localized on the endomembrane system [17]. However, only lysosome membrane-associated Rheb has been demonstrated to possess mTORC1 activating capacity, where the Rag-Ragulator complex shuttles the inactive mTORC1 to GTP-bound Rheb for its activation [17, 77]. Compared with Rag-Ragulator signaling, which is essential in sensing the intracellular amino acid levels through an “inside-out” mechanism [62], Rheb is mainly regulated by the TSC complex, which receives the systematic nutrient signals, such as growth factors, to trigger activation of the Akt pathway to subsequently phosphorylate TSC2, releasing it from the lysosomal membrane surface and its inhibition of Rheb [78].

Rheb KO mouse models have been established and mainly demonstrate the vital role of Rheb in developmental process. The Rheb−/− mice die around mid-gestation due to defects in cardiovascular development [79]. The developmental impairments were also confirmed by both smaller body size and a decreased proliferation capacity of Rheb−/− MEFs compared to wild type MEFs [79]. As to the isoform specific knockout mice, the Rheb1−/− mice die between E10.5 and E11.5, whereas the Rheb2−/− mice develop normally and show no obvious defects until adulthood, indicating that Rheb1, but not Rheb2, is essential for embryonic survival and mTORC1 signaling [80]. To further examine the physiological role of Rheb1 in various tissues, Rheb1 neural progenitor cell conditional KO mice were generated and exhibit impairment of brain postnatal myelination, but no obvious defects in early postnatal brain development was observed, suggesting that Rheb1 plays a role in selective cellular adaptation [80]. Another study using liver-specific Rheb KO mice showed increased mitochondria content in liver, and further proved the mitochondrial localized Rheb promotes mitophagy, contributing to the maintenance of optimal mitochondrial energy production [81].

A series of mouse models and clinical evidences also support the notion that Rheb may act as an oncogene in various cancer settings. For example, after adoptive transferring an Eμ-Myc lymphoma mouse model, Rheb acted as an oncogene in promoting lymphoma progression as well as drug-resistance [82]. Furthermore, another independent study using a Rheb transgenic mouse model demonstrated that Pten haplo-insufficiency and Rheb overexpression worked synergistically to promote prostate cancer progression [83]. Moreover, systematic examination of the clinical database revealed a positive correlation between an increase in Rheb expression levels and a higher cancer occurrence rate in breast, liver, lung, head and neck, and bladder [84]. Cumulatively, these results indicate that Rheb acts as an oncogene and thus is a potential therapeutic target for certain types of cancer.

1.4.3. RAG

Similar to Rheb, the Rag family of proteins is also a subgroup of Ras GTPase, including four isoforms in mammals, RagA, RagB, RagC and RagD. Unlike other Ras family members, the Rag GTPases function by forming heterodimers consisting RagA or RagB with RagC or RagD [85]. As mentioned previously, the Rag-Ragulator complex is essential in sensing the intracellular amino acids levels to facilitate the subsequent activation of mTOR1 [86, 87]. Considering GTP-bound RagA/B alone can activate the mTORC1 kinase even in the absence of amino acids, the loading of RagA/B with GTP appears to be functionally predominant over GTP or GDP-loaded RagC/D [86, 87], which also explains why recent genetic mouse models are largely focused on manipulating RagA and RagB.

In order to illustrate the physiological role of RagA, a knock-in mouse model that expresses a constitutive active form of RagA (Q66L) has been generated, which exhibited defects in glucose homeostasis and autophagy and die on postnatal day 1 [88]. Furthermore, the RagA−/− mice show a loss of mTORC1 activity, profound developmental defects and die around E10.5, whereas the RagB−/− mice show no overt developmental abnormality and no obvious reduction in mTORC1 activity, indicating that RagA, but not RagB, is more important for mTORC1 activity [89]. Given that whole body and liver specific RagA−/−/RagB−/− mice exhibit a more robust loss of mTORC1 activity, the phenotype difference between RagA−/− and mTOR−/−(or Raptor−/−) mice may be in part due to the compensation effect of RagB [89]. Interestingly, the heart-specific RagA−/−/RagB−/− mice do not show an impairment of mTORC1 activity, but manifest cardiac hypertrophy, defective autophagy and lysosome function, whereas none of the heart-specific RagA−/− or RagB−/− mice shows cardiac hypertrophy [90]. Thus, different phenotypes of various tissue-specific Rag KO mice indicate that the role of Rag GTPase in governing mTORC1 activation may be tissue-specific or context-dependent.

Thus far, no Rag genetic mouse model has been associated with tumor formation yet. However, several GAPs (GTPase-activation proteins) have been linked to tumorigenesis. Specifically, the tumor suppressor gene Flcn (folliculin), the mutation of which is considered the driving force behind the pathologic phenotypes of the BHD (Birt-Hogg-Dubé) syndrome, is necessary for mTORC1 activation in part by acting as a GAP for RagC/D [91]. Moreover, it has also been demonstrated that the protein complex GATOR could serve as the GAP for RagA/B, and inactivation mutations of GATOR1 components including DEPDC5 and NPRL2 have been associated with aberrant mTORC1 activation in cancer cell lines [92]. However, the physiological contributions of these two proteins to tumorigenesis in vivo still require additional studies by utilizing Gator1 or Flcn KO mice.

1.4.4. AMPK

AMPK is a conserved serine/threonine kinase, functioning as a fuel sensor to maintain cellular energy homeostasis [93, 94]. Once activated under low energy state, AMPK inhibits the anabolic processes such as protein and lipid biosynthesis, and promotes catabolic pathways including fatty acid oxidation and glycolysis, resulting in the fostered generation of ATP. AMPK exists as a hetero-trimetric complex consisting of a catalytic subunit α and two regulatory β and γ subunits [93]. Two or three isoforms of each subunit have been identified in mammals (namely α1, α2, β1, β2, γ1, γ2 and γ3) [95]. It has been established that AMPK could negatively regulates the activation of mTORC1 complex indirectly in part through phosphorylation of the mTORC1 upstream regulator TSC2 to keep its suppression on Rheb [61] or directly via phosphorylation of the mTORC1 regulatory but essential component, Raptor, to trigger its interaction with 14-3-3 and subsequent dissociation from mTOR [96].

Given that AMPK acts as a key regulator of cellular metabolism, Ampk KO mouse models have been generated to closely examine the physiological roles of AMPK subunits on metabolism. Complete loss of AMPK kinase activity is not tolerated at the whole-body level in vivo, which has been supported by the observation that the Ampkα1−/−/Ampkα2−/− mice are embryonic lethal at E10.5 [97]. However, muscle-specific Ampkα1−/−/Ampkα2−/− mice are viable, but the skeletal muscle of these KO mice have an increased mass with larger myofibers compared to their wild type littermates [98], indicating a physiological role of AMPK activity in governing muscle function. On the other hand, loss of either isoform of the AMPK catalytic α1 or α2 subunits is permissible, as the Ampkα1−/− mice are largely normal, and the Ampkα2−/− mice are viable but exhibit higher glucose levels in the feeding period and therefore are more likely to develop obesity under a high-fat diet [99]. Thus AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 may play non-redundant roles in vivo. This notion was further supported by the observation that bone tissue-specific Ampkα1−/− mice showed elevated rate of bone remodeling, while the Ampkα2−/− mice only show bone absorption phenotypes [100].

Notably, deletion of various AMPK regulatory subunits appears to have no significant effects on mouse survival. Specifically, the Ampkγ3−/− mice show impaired glycogen re-syntheses after exercise [101]. Furthermore, muscle-specific Ampkβ1/Ampkβ2 DKO mice are physically inactive and display reduced mitochondrial content in muscle cells [102], impinging a possible role of AMPKβ in regulating energy homeostasis in muscle. More importantly, these findings paved the way for the clinical application of metformin, an AMPK-activating drug, in treating type 2 diabetes by increasing glucose uptake and fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscles [103]. Interestingly, follow-up studies indicated that metformin may also reduce the incidence of cancer, especially colon and liver cancers in diabetic patients, implying a possible tumor suppressor role of AMPK [104].

In line with these findings, as a downstream effector of the tumor suppressor LKB1, AMPK is commonly characterized as a metabolic tumor suppressor. This was supported by a study demonstrating that ablation of the Ampkα1 subunit, the only subunit in B cells, resulted in accelerated B-cell lymphomagenesis in an Eμ-Myc transgenic mouse model [105]. Furthermore, loss of AMPKα signaling led to an enhancement of Warburg effects and increased HIF-1α expression levels, which subsequently promoted glycolytic pathways and lymphoma progression [105]. Additionally, Ampkα2−/−, but not Ampkα1−/− MEFs exhibited increased susceptibility to H-RasV12 transformation in vivo and tumorigenesis in vitro [106], indicating that AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 subunits may exert their tumor suppressor function in a tissue-dependent or context-dependent manner. On the other hand, another study revealed that AMPK activation during energy stress maintained the cellular NAPDH levels and facilitated cell survival and tumor growth through redox regulation [107], revealing an oncogenic potential for AMPK in cells. Cumulatively, these results indicate that AMPK may in large act as a tumor suppressor in pre-tumor lesions. However, once the tumor is established, AMPK may promote tumor cell survival under metabolic stress [93], which warrants further detailed investigations with additional mouse modeling studies for clarification.

1.5 mTORC1 downstream substrates in tumorigenesis

The major function of mTORC1 is to control protein synthesis through directly phosphorylating translational regulators 4E-BP1 and S6K1 (S6 kinase 1) [120, 121]. Notably, recent work from the Manning group suggests that mTORC1 also regulates the protein turnover rate to balance protein synthesis and degradation largely through promoting NRF1-dependent elevation of proteasome levels [122]. Nevertheless, in both processes, mTORC1 activity is required for targeting a subset of its substrates for phosphorylation-mediated regulation to exert its biological functions.

1.5.1. 4E-BP1

mTORC1-mediated phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 prevents its binding with the cap-binding protein eIF4E, resulting in the initiation of cap-dependent translation [123]. Consequently, eIF4E-dependent translation enhances cell growth and proliferation by increasing translation of a subset of pro-oncogenic proteins involved in regulating cell survival, cell-cycle progression and angiogenesis, such as c-Myc, ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), cyclin D1, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [17, 124].

To further understand the physiological role of 4E-BP1 in vivo, 4E-bp1−/− mice were generated in 2001, which led to markedly smaller white fat pads than wild-type animals, and the male KO mice showed an elevated metabolic rate. Furthermore, white adipose tissues derived from male KO mice showed manifestation and biomarkers of brown fat [125]. Additionally, 4E-bp1−/−/4E-bp2−/− mice demonstrate an increased insulin resistance, coupled with increased S6K activity and impaired Akt activity in muscle, liver, and adipose tissue [126]. Together, these results clearly showed a protective role for 4E-BPs in the development of obesity. Moreover, 4E-bp1−/− mice also have an increased immature granulocytic precursor number and a decreased mature granulocytic number in bone marrow and spleen, indicating an important role for 4E-BP1 in early granulo-monocytic differentiation [127].

Moreover, consistent with an oncogenic role for eIF4E in vivo, a lymphoma mouse model that was reconstituted with Eμ-Myc HSCs (hematopoietic stem cells) transduced with eif-4e expression displays a disseminated pathology and is highly resistant to chemotherapy [9, 128]. Furthermore, more compound 4E-bp1 genetic mouse models indicate the function loss of 4E-BP1 might contribute to the growth of sporadic cancers. For example, compared with p53−/− mice, 4E-bp1−/−/4E-bp2−/−/p53−/− mice manifest with an increased tumor-free survival, indicating that inactivation of 4E-BPs worked synergistically with p53 loss to promote cell proliferation and tumorigenesis [129]. Furthermore, another group showed that inactivation of 4E-BP1 through phosphorylation was a key effector in the oncogenic activation of the Akt and ERK signaling pathways [130]. Specifically, a phosphorylation-deficient mutant of 4E-BP1 that mimics a constitutively active form of 4E-BP1, showed impaired tumor growth in vivo [130]. Hence, these studies indicate the emerging role of 4E-BP1 as a tumor suppressor and might be a potential therapeutic target for the cancer patients bearing p53 loss or hyper-activation of Akt or ERK signaling.

1.5.2. S6K

Mammalian cells contain two isoforms of S6K, namely S6K1 and S6K2, both of which can be directly phosphorylated by mTORC1 [131, 132]. In 1998, the S6k1−/− mice were generated and 20% smaller body mass and organ size were observed compared to their wild type littermates [133]. It was also reported that the viability of S6k1−/−/S6k2−/− mice were sharply reduced due to perinatal lethality [134]. Other than the growth deficiency phenotypes, glucose metabolism was dysfunctional in S6k1−/− mice, whereas S6k1−/− mice suffer from hypo-insulinaemia and are glucose intolerant due to reduced β-cell size in pancreas [135]. Therefore, the mice are less likely to develop obesity due to an increased lipolysis and metabolism rate, which is related to enhanced β-oxidation process [136, 137]. However, no cancer-related S6K mouse models have been established so far, which warrants further investigation of whether S6K plays distinct roles in facilitating tumor formation in different tissues.

Mechanistically, a feedback loop has been established to indicate that S6K1 negatively regulates the stability of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) through directly phosphorylating the S307 and S636/S639 residues under nutrient deprivation conditions [136], as well as shuts down insulin or IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor) mediated activation of Akt by phosphorylating Grb10 (growth factor receptor-bound protein 10) [138, 139]. Similarly, our group recently demonstrated that S6K1 could directly phosphorylates the essential component of mTORC2, Sin1, on both T86 and T398 residues to dissociate Sin1 from the functional mTORC2 complex to terminate its activity towards activating the Akt oncogenic signaling [20]. These results indicate that S6K might exert its oncogenic function through its positive regulation on protein synthesis, and could also display certain “tumor suppressor” role in inactivating growth factor signaling and lead to insulin resistant phenotype. Therefore, it will be important to develop additional genetically engineered mouse models within various tumor backgrounds to fully understand the physiological role of S6K in tumorigenesis.

1.5.3. SREBP

In addition to protein synthesis, mTORC1 also controls lipid synthesis, which is important for cell membrane homeostasis and cell survival [17]. SREBPs are responsive elements to sterols and are inactive when they are oriented to membranes of ER (endoplasmic reticulum) [140]. Under insulin or sterol depletion, SREBPs are truncated through a proteolytic cleavage process, thereby releasing their active forms from membranes and migrate into nucleus to activate relevant genes for lipid synthesis [140]. It has been reported that the activation status of mTORC1 positively correlates with SREBP1 activity [141, 142]. Mechanistically, mTORC1 regulates SREBP activity through several mechanisms, including S6K1-dependent and lipin-dependent regulations [142, 143]. However, whether and how mTORC1 may directly regulate SREBP activity is still largely unknown [17].

In mammalian cells, three SREBP isoforms (SREBP-1a, SREBP-1c, and SREBP-2) have been identified [144]. To demonstrate the function of individual SREBP isoforms, a series of SREBP isoform-specific KO mouse models have been developed (Table 3). Specifically, 55%–90% of Srebp-1a−/−/Srebp-1c−/− mice die on E11. Survived mice are normal at birth, but reduced synthesis of fatty acid and compensatory elevated expression of Srebp-2 was observed throughout their lives [145]. Similarly, Srebp-2−/− embryos die around E7–8 [145]. Different from the observed embryonic lethality of Srebp-1−/− and Srebp-2−/− mice, the Srebp-1c−/− mice are viable, although a reduction in fatty acid and triglyceride synthesis is observed in liver [140, 146]. Consistent with the important role of SREBP in lipid synthesis, the liver-specific Tg Srebp mice display lipid metabolism disorders (Table 3) [145, 147, 148].

Table 3.

Major physiological functions of the mTORC1 substrates.

| mTORC1 downstream effectors | Mouse models | Major phenotypes | Putative roles in tumorigenesis | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knockout | Transgenic | ||||

| 4E-BP1 | 4E-bp1−/− | Smaller white fat pads; impaired granulocytic early differentiation | Emerging role as a tumor suppressor | [125, 127] | |

| 4E-bp1−/−/4E-bp2−/− | Increased insulin resistance | [126] | |||

| 4E-bp1−/−/4E-bp2−/− /p53−/− | Increased tumor-free survival | [129] | |||

| Transgenic 4E-BP1 | Inhibited tumor growth in vivo | [130] | |||

| S6K | S6k1−/− | Smaller body size; obesity-like metabolism disorder | To be determined | [133–136] | |

| S6k2−/− | Slightly larger body size | [134] | |||

| S6k1−/−/S6k2−/− | Sharp reduction in viability | [134] | |||

| SREBP | Srebp1−/− | Embryonic lethal at E11 | Emerging role as an oncogene | [140] | |

| Srebp1c−/− | Lipid metabolism disorder in liver | [146, 160] | |||

| Srebp2−/− | Embryonic lethal at E7~E8 | [160] | |||

| Truncated Srebp-1a transgenic (liver) | Developed a massive fatty liver enriched with cholesterol and triglycerides | [147] | |||

| Truncated Srebp-1c transgenic (liver) | Developed a fatty liver enriched with triglycerides | [148] | |||

| Truncated Srebp-2 transgenic (liver) | Developed a fatty liver enriched with cholesterol | [145] | |||

| ULK1 | Ulk1−/− | Defects in reticulocyte maturation | To be determined | [157] | |

| Transcription factor EB (TFEB) | Tfeb−/− | Embryonic lethal between E9.5–10.5 | To be determined | [156] | |

| Conditional Tfeb−/− (osteoclast) | Increased bone mass | [161] | |||

| Beclin1 | Beclin1+/− | Increased spontaneous malignancy | Tumor suppressor | [158] | |

Keys: +, wild type allele; −, null allele.

Given that increased de novo lipid synthesis is a hallmark of cancer pathogenesis, as well as elevated expression of SREBP target genes such as FAS (fatty acid synthase) is nearly ubiquitously observed in cancer cells [149], the SREBP pathway may possess a oncogenic property [142]. Consistent with this possibility, it has been reported that depletion of an oncogenic mutant of the tumor suppressor p53 is sufficient to revert the breast cancer cell phenotype towards normal epithelia phenotype, which correlates with sterol synthesis at least partially though SREBP [150]. These findings further support the notion that the SREBP pathway is likely to be a potential drug target for anti-cancer therapies.

1.5.4. Autophagy Components

Autophagy was firstly discovered more than 40 years ago, when autophagic vacuoles (the smooth endoplasmic reticulum) were observed in the hepatocytes after cessation of phenobarbital induction, indicating that cells can digest cellular organelles [151]. Under nutrient deprivation conditions, mTORC1 is inhibited by AMPK and amino acid signaling [152], causing bulk cytoplasm and organelles to form double membrane sequestering vesicles or “autophagosomes”, which are then delivered to the lysosome for degradation [153]. mTORC1 has been shown to play a negative regulatory role in the autophagy process in mammals through several mechanisms. First, under rich nutrient conditions, mTORC1 directly phosphorylates ULK1 (uncoordinated 51-like kinase 1) and Atg13 (mammalian autophagy-related gene 13), leading to dissociation of the ULK1/Atg13/FIP200 (FAK family-interacting protein complex of 200 kDa) complex to inhibit autophagy. Second, mTORC1-dependent phosphorylation and inactivation of DAP1 (death-associated protein 1) acts as a braking system for the autophagic flux [154]. Third, phosphorylation of TFEB (transcription factor EB) by mTORC1 retains TFEB in the cytosol, which inhibits the transcription of critical autophagy related genes [155].

Several mouse models have been developed in order to reveal the physiological roles for individual autophagic genes. To this end, it has been reported that the Tfeb−/− mice die between E9.5–10.5 due to severe defects in placental vascularization [156]. Tfeb osteoclasts-specific conditional KO mice show a decreased lysosomal gene expression and an increased bone mass. Moreover, though with defects in reticulocyte maturation, Ulk1−/− mice are viable and show no overt developmental defects [157]. Thus it seems that different autophagic genes might play differential roles in the developmental process.

However, it is more important to understand the relationship between autophagy and cancer. To this end, autophagy has been considered to protect cells from cancer through removing damaged mitochondria, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and long-lived proteins [158]. Consistently, loss-of-function mutations of Beclin 1, an essential component of autophagy, have been found in several solid tumors [153]. More importantly, Beclin1+/− mice exhibit higher rates of spontaneous malignancy [158], suggesting that Beclin 1 may play a tumor suppressor role in vivo. On the other hand, inhibiting autophagy enhanced the chemotherapeutic effects in part by promoting apoptosis in a lymphoma mouse model [159], arguing for an oncogenic role for the autophagy process. Thus, autophagy may be important to prevent cancer initiation but necessary for cancer cells to survive in energy and nutrient deficient conditions [17].

1.6 mTORC2 substrates in tumorigenesis

1.6.1. Akt

The serine/threonine kinase Akt, also known as protein kinase B, is one of the most commonly activated onco-proteins in human cancers [32, 162]. Notably, cancerous hyper-activated Akt accelerates cell growth and proliferation, facilitates resistance to apoptosis as well as promotes angiogenesis [162, 163]. Three highly homologous Akt isoforms have been identified in mammals, namely Akt1 (also known as PKBα), Akt2 (PKBβ) and Akt3 (PKBγ) [164]. Akt1 and Akt2 are ubiquitously expressed, while Akt3 is primarily expressed in the brain and testis [165]. Upon extra-cellular growth factors stimulation, activation of PI3K (phosphoinositide 3-kinase) leads to increased levels of PIP3 (phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate), which serves as a lipid second messenger to recruit Akt, through its PH (pleckstrin homology) domain to the plasma membrane, as well as its activating kinase, PDK1 (phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1) [166]. The Akt-PH/PIP3 interaction induces a conformational change in Akt, which enables the exposure and phosphorylation of two critical residues, Thr308 and Ser473 [167], by PDK1 [168] and mTORC2 [169], respectively, achieving Akt full activation. Activated Akt will then phosphorylate a large spectrum of proteins in the cytoplasm, mitochondria and nucleus to exert its various physiological functions [170]. More than 200 Akt substrates have been identified so far and they all share a similar Akt recognizable consensus motif (RxRxxpS/pT) [171]. Interestingly, we recently observed that Akt activation is cell cycle-dependent. Furthermore, we identified that in addition to mTOR, Cdk2/Cyclin A directly phosphorylates Akt1 at its extreme C-terminus on S477 and T479 residues, which either primes for, or compensates for Akt-S473 phosphorylation, revealing a new regulatory mechanism for Akt activation [172].

Different cellular distributions and functions for three Akt isoforms have emerged after generation of the Akt isoform-specific KO mice by two independent labs [173–175]. Specifically, Akt1−/− mice are smaller than their wild type counterparts and Akt1−/− MEFs are more vulnerable to induced apoptosis [176], supporting a role for the Akt1 isoform in controlling body size and cell survival. On the other hand, Akt2−/− mice develop an insulin resistance phenotype largely due to changes of hormones in liver and skeletal muscle, which reveals a critical role for Akt2 in maintaining glucose homeostasis [174, 177]. Consistent with a predominant expression pattern of Akt3 in the brain, the brain size and weight from Akt3−/− mice are reduced by 25%, compared with their wild type counterparts [178, 179]. Although loss of a single Akt1 isoform is tolerated in vivo, combined deletion of additional Akt isoform(s) with Akt1 displays an embryonic lethality phenotype. Specifically, the Akt1−/−/Akt2−/− mice die shortly after birth, and are much smaller with impaired development of skin, skeletal muscle and bone [180]. Similarly, the Akt1−/−/Akt3−/− mice die between E11–12 due to severe defects in development of cardiovascular and nervous systems [179]. On the other hand, the Akt2−/−/Akt3−/− mice are viable but smaller, and exhibit severe glucose and insulin intolerance [181]. These results reinforce the notion that Akt1 is the major isoform for maintaining Akt function during the development.

Aberrant activation of Akt isoforms has been frequently observed in different organ-originated cancer patients [170]. This might be due to Akt gene amplification and/or Akt somatic mutations, which contribute to the pathological Akt hyper-activation. For example, the Akt1-E17K somatic mutation in the Akt PH domain occurring in human breast, ovarian and colorectal cancer patients is tightly associated with Akt hyper-activation, which could induce B-cell leukemia in a Eμ-Myc transgenic mouse model, while wild type Akt failed to do so [182]. Moreover, hyper-activation of the mTOR/Akt signaling might also stem from mutations of signaling components upstream of Akt, which are also commonly observed in a series of human cancers, including somatic mutations of PI3KCA and loss-of-function mutations of Pten [183–187]. In addition, gene rearrangements leading to an in-frame fusion gene of Akt3 with Magi3 (membrane-associated guanylate kinase, WW and PDZ domain containing 3) has been found in breast cancer patients (8/235) [188], which produced a MAGI3–Akt3 fusion protein, resulting in the loss of the PH-domain-mediated suppression of Akt and subsequently constitutive activation of Akt3 [188].

To further determine the role of Akt isoforms in cancer, mouse models have been generated with an Akt isoform combined with various cancerous mouse models. Furthermore, application of a polyoma middle T (PyMT) and ErbB2/Neu-driven mammary adenocarcinomas model in the Akt1−/−, Akt2−/− and Akt3−/− mice make it feasible to demonstrate the specific role of each Akt isoform in driving tumorigenesis under these unique conditions. Notably, in contrary to Akt2−/− mice, the Akt1−/− mice showed an inhibited tumor initiation with an accelerated tumor invasion [189]. Consistently, transgenic expression of Akt1 or Akt2 isoforms in transformed mammary glands also demonstrated that expression of Akt1 accelerated tumor development and inhibited invasion, while expression of Akt2 exhibited the opposite effects [190]. Hence, these results indicate that different Akt isoforms may exert unique roles in tumorigenesis in a context-dependent manner.

The mammalian PKCs comprise conventional PKCs (PKC-α, PKC-β and PKC-γ), novel PKCs (PKC-δ, PKC-ε, PKC-η and PKC-θ) and atypical PKCs (PKC-ζ and PKC-λ/ι) [191]. As a member of the AGC kinase family, activation of all PKC isoforms is also phosphorylation-dependent [26]. Activation of PKC not only requires hydrophobic motif phosphorylation by mTORC2 and kinase motif phosphorylation by PDK1, but also needs further stimulatory regulation by second messengers [26], which differs from the activation of Akt. Specifically, the second messengers for conventional PKCs is calcium and diacylglycerol; for novel PKCs is diacylglycerol but not calcium, while neither is required for the activation of atypical PKCs [192]. Most PKC isoforms are ubiquitously expressed in all tissues, although they may exert different roles under both physiological and pathological conditions [193].

To determine the exact physiological function of each PKC isoform, different PKC isoform KO mouse models were established and different phenotypes were observed (Table 4), indicating the essential role of PKC in the development of the immune system and central nervous system [194–203]. In addition, various transgenic mouse models further support the notion that different PKC isoforms may exert different roles in tumorigenesis. For example, PKC-ε and PKC-λ/ι are generally considered to be oncogenes. Pathologically, clinical studies further revealed the incidence and malignancy of malignant glioma are tightly correlated with PKC-ε activation [204]. Moreover, PKC-λ/ι has also been reported to promote Ras-mediated transformation and colon tumorigenesis in transgenic mice [205], and its oncogenic role was echoed by observed overexpression or hyper-activation in human non-small cell lung cancer [206] and ovarian cancer [207]. Furthermore, the PKC-β isoform is linked to carcinogenesis as PKC-β−/− mice are resistant to azoxymethane (AOM)-induced colon carcinogenesis, while transgenic expression of PKC-β in PKC-β−/− mice restored colon cancer development [208]. Moreover, another study revealed that PKC-β was essential in VEGF-induced vasculogenesis [209]. Consistent with an oncogenic role for PKC kinases in tumorigenesis, several PKC inhibitors have been tested in clinical trials for treatment of cancer patients [210]. On the other hand, it is difficult to simply define the other PKC isoforms as either oncogene or tumor suppressor. For example, PKC-α transgenic mice illustrate a positive role for PKC-α in promoting cell proliferation [211]. However, clinical evidences suggest that over-expression of PKC-α in prostate, endometrial and hepatocellular cancers, whereas the down-regulation of PKC-α was observed in basal cell carcinoma and colon cancers, indicating that the role for PKC-α in tumorigenesis may be context-dependent [212]. To further evaluate the specific role of PKC isoforms in cancer, more PKC isoform-specific and tissue-specific knockout mouse models are warranted for further in-depth investigations in the near future.

Table 4.

Major physiological functions of the mTORC2 substrates.

| mTORC2 substrates | Mouse models | Major phenotypes | Putative roles in tumorigenesis | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| knockout | Transgenic | ||||

| Akt | Akt1−/− | Reduced body, brain and liver size | Oncogene | [173, 176] | |

| Akt2−/− | Insulin resistance and diabetes | [174, 177] | |||

| Akt3−/− | Reduction in body size and brain weight | [175, 178] | |||

| Akt1−/−/Akt2−/− | Born with reduced body size; died shortly after birth | [180] | |||

| Akt1−/−/Akt3−/− | Embryonic lethal at E11~E12 | [179] | |||

| Akt2−/−/Akt3−/− | Reduced body size; insulin resistance | [181] | |||

| Conditional Akt1−/− (mammary gland) | Inhibited tumor initiation; accelerated tumor invasion | [189] | |||

| Conditional Akt2−/− (mammary gland) | Accelerated tumor initiation; inhibited tumor invasion | [189] | |||

| Akt1 transgenic (ErbB-2 transgenic mammary gland mice) | Promoted tumor development; inhibited metastasis | [226] | |||

| Akt2 transgenic (ErbB-2 transgenic mammary gland mice) | Inhibited tumor development; promoted metastasis | [226] | |||

| PKC | Pkc-α−/− | Diminished glucose induced albuminuria | Isoform-specific (Pkc-ε and Pkc-ι are oncogenes) | [194] | |

| Pkc-β−/− | Humoral immunodeficiency; resistance to carcinogen-induced colonic tumors | [195, 208] | |||

| Pkc-γ−/− | Mild deficits in spatial and contextual learning | [196, 197] | |||

| Pkc-δ−/− | B-cell dysfunction | [198, 199] | |||

| Pkc-ε−/− | Severely impaired innate immunity; decreased hyperalgesia | [200, 201] | |||

| Pkc-ζ−/− | B cell malfunction | [202, 203] | |||

| Pkc-θ−/− | Impaired cell activation; protective from fat-induced insulin resistance | [227, 228] | |||

| Transgenic Pkc-βII (pkc-β−/−) | Restored the susceptibility to carcinogen - induced colon tumor | [208] | |||

| Transgenic Pkc-ι | Susceptible to carcinogen-induced colon carcinogenesis | [205] | |||

| SGK | Sgk1−/− | Impaired renal sodium retention under low salt diet | Context-dependent | [216] | |

| Sgk3−/− | Delayed hair growth | [217] | |||

| Sgk1−/−/Sgk3−/− | Delayed hair growth; lower blood pressure | [217] | |||

| Compound Sgk1−/− /ApcMin/+mice | Inhibited tumorigenesis | [218] | |||

Keys: +, wild type allele; −, null allele; H, hypomorphic allele; AOM, azoxymethane.

1.6.3. SGK

As a member of the AGC kinase family, SGK1 is a serine/threonine kinase that under transcriptional control of various stimuli including serum, glucocorticoids, cytokines and other growth factors [213]. In addition to SGK1, two other isoforms have also been identified, namely SGK2 and SGK3 [214]. Similar to other members of the AGC kinase family such as Akt and PKC, activation of SGK requires phosphorylation by PDK1 and mTORC2 [215].

To evaluate the physiological roles of SGK isoforms in vivo, Sgk1−/− mice were developed in 2002, and these mice show impaired renal sodium retention under low salt diet, due to decreased renal epithelial Na+ channel activity, which subsequently leads to lower blood pressure and glomerular filtration rate [216]. Moreover, Sgk3−/− mice exhibit a delayed hair growth phenotype without a sodium chloride excretion abnormality [217]. Notably, Sgk1−/−/Sgk3−/− mice exhibit both phenotypes of Sgk1−/− and Sgk3−/− mice [217], suggesting that SGK1 and SGK3 possess non-redundant developmental functions in vivo. Although genetic ablation of SGK does not result in tumorigenesis, after induction by chemical carcinogen, Sgk1−/− mice develop much less colonic tumors than their wild-type littermates, supporting a physiological role for SGK1 deficiency in counteracting carcinogenesis [213]. Consistently, the ApcMin/+/Sgk1−/− compound mice, generated by crossing Sgk1−/− mice with an APC (adenomatous polyposis coli) tumor suppressor defective (ApcMin/+) mice, develop much less intestinal tumors than ApcMin/+/Sgk1+/+ mice, as well as associate with decreased levels of colonic β-catenin protein [218], further supporting an oncogenic role for SGK1 in vivo. Consistently, administration of SGK inhibitors promoted radiation-induced tumor cell apoptosis in vitro and decreased the number of tumors in vivo, supporting the notion that SGK facilitates colon cancer progression [219].

Mutations of SGK appear to be mutually exclusive with Akt mutations in cancer [220]. Both SGK and Akt share common downstream substrates, as well as are able to promote cell growth, proliferation and migration [220]. Accordingly, SGK3 has been observed to be able to compensate for Akt to facilitate tumorigenesis in many PIK3CA mutated cancer cells and breast tumors. Moreover, SGK3-dependent PDK1 signaling was shown to be required for tumor growth, indicating the oncogenic role of SGK3 [221]. Clinically, up-regulation of SGK1 has been reported in multiple tumor types, such as prostate cancer [222] and non-small cell lung cancer [223]. However, this phenotype is tissue-dependent, as decreased SGK1 expression was also found in adenomatous polyposis coli [218], adenomatous ovarian cancer [224] and hepatocellular cancer [225]. Given that SGK is not essential in tumor cell survival, the physiological role of SGK in tumorigenesis may be tissue-dependent and context-dependent, which warrants further in-depth investigations in part by generating additional tissue-specific SGK transgenic mouse models.

Discussion

Hyper-activation of the PI3K/mTOR/Akt signaling pathway is among the most commonly observed pathological alterations in human cancers [32]. Since the identification of the yeast TOR gene in 1990s, the mTOR/Akt pathway has been considered a central regulator in controlling cell growth, proliferation and survival, as well as a promising anti-cancer drug target [229, 230]. In this review, we summarized the growing list of available genetic mouse models, pathological alteration status as well as downstream targets for key pathway components that are closely related to mTORC1 and mTORC2 (Table 1–4). More importantly, based on these physiological and pathological evidences, we assigned a possible role for each listed member for its role in tumorigenesis. Due to space limitation, we cannot include mouse models of some indirect regulators of mTOR complexes, such as PI3K [231, 232], PTEN [233, 234], PLD (phospholipase D) [235–237], LKB1 [238], FLCN [91, 239] and REDD1 (regulated in development and DNA damage responses 1) [240] in the current review, although they are also critical for our further understanding of how dysregulation of the mTOR signaling pathway facilitates tumorigenesis.

Table 1.

Mouse phenotypes upon knockout of the various core subunits of mTORC complex.

| mTOR complex subunits | Mouse models | Major phenotypes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| mTOR | mTOR−/− | Embryonic lethal around E5.5–6.5; blastocysts fail to expansion | [35] |

| mTOR+/− | Without overt defects | [36] | |

| mTORH/H | Longer lifespan | [37] | |

| Conditional mTOR−/− (muscle) | Severe myopathy | [38] | |

| mLST8 | mLST8−/− | Embryonic lethal around E10.5; vascular development defects | [18] |

| Raptor | Raptor−/− | Embryonic death before E7, blastocysts fail to expand | [18] |

| Conditional Raptor−/− (skeletal muscle) | Severe muscle dystrophy | [40] | |

| Conditional Raptor−/− (heart) | Dilated cardiomyopathy 6 weeks post-deletion | [41] | |

| Conditional Raptor−/− (liver) | 40% smaller liver mass | [43] | |

| Conditional Raptor−/− (brain) | Smaller brain beginning at E17.5; die shortly after birth | [42] | |

| Conditional Raptor−/− (HSC) | Impairments in granulocytes and B cells development | [44] | |

| Conditional Raptor−/− (AML mouse model) | Significantly inhibited leukemia progression | [44] | |

| Rictor | Rictor−/− | Embryonic lethal at E10.5–11.5; vascular development defects | [18, 45] |

| Rictor+/−Pten+/− | Less prostate tumor incidence; less severe lesions and longer lifespan than Pten+/− mice | [52] | |

| Conditional Rictor−/−(muscle) | Local glucose metabolism disorder | [46] | |

| Conditional Rictor−/−(neuron) | Smaller brain and body size; schizophrenic-like behavior | [49, 50] | |

| Conditional Rictor−/−(liver) | Abnormal response to insulin | [47] | |

| Conditional Rictor−/−(fat cell) | Whole body glucose and lipid metabolism disorders | [48] | |

| Sin1 | Sin1−/− | Embryonic lethal at E10.5~15.5; cardiovascular development defects | [53] |

| Conditional Sin1−/− (B cell) | Increased V(D)J recombinase activity | [53] | |

| Conditional Sin1−/− (T cell) | Increased thymic T-regulatory cells | [54] |

Keys: +, wild type allele; −, null allele; H, hypomorphic allele.

Extensive studies have greatly facilitated our current understanding of the biological functions of the mTOR pathway. However, clinical applications of inhibitors targeting key oncogenic members of this pathway, including mTOR, Akt, PKC, SGK and S6K, haven’t achieved satisfactory clinical outcomes due to many reasons [33, 34, 210, 241]. Since rapamycin opens the mTOR research field, its application on treating mTOR-related diseases has been extensively studied. For example, rapamycin was the first drug examined to be able to extend the lifespan in mice [242]. However, comprehensive and large-scale assessment showed these effects were not due to ageing [243]. As rapamycin is a potent acute inhibitor for mTORC1 [3, 4] and chronic inhibitor for mTORC2 [244, 245], it has been used to combat various human cancers but only reached limited success [34]. For example, rapamycin analogs everolimus improved the progression-free survival in a clinical phase III study on patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma that progressed on VEGFR-targeted therapy, but the objective response rate was only 1% [246]. More importantly, cancer patients received rapamycin typically developed an insulin resistance after prolonged treatments [247]. In addition to rapamycin, an allosteric mTOR inhibitor, some ATP-competitive mTOR kinase inhibitors are in clinical trails to treat cancer patients, including INK128 [248], AZD8055 [249] and AZD2014 [250]. Unfortunately, these compounds demonstrated only limited success in shrinking KRAS driven tumors [251], suggesting that targeting both mTORC1 and mTORC2 for inhibition might not be an optimal treatment option. Instead, mTORC2-specific inhibitors might shed new lights on targeted therapeutic avenues to treat cancer patients with deregulated mTOR signaling.

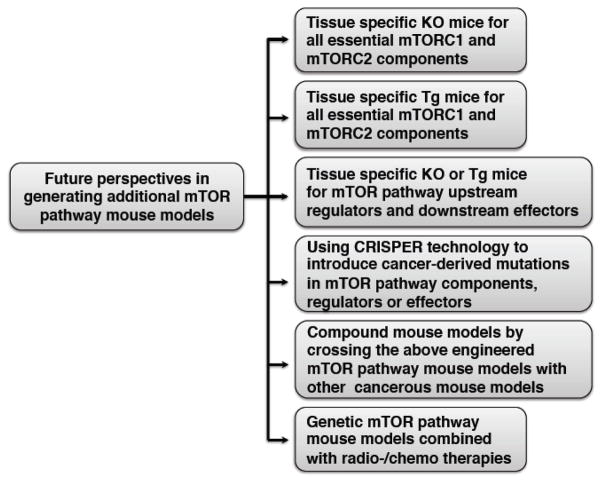

To this end, more thorough and in-depth understanding of how the mTOR/Akt pathway is regulated in normal cells and dysregulated in cancer cells would benefit the identification of new mTORC2 upstream regulators, and more importantly might lead to the discovery of more potential anti-cancer drug targets. Achieving this goal will rely on thorough biochemical studies to examine the cellular functions, utilization of deep sequencing technology for analyzing the genetic alteration status of target genes in cancer patient samples, and more importantly, the establishment of additional sophisticated and comprehensive mouse models to examine the physiological role for each signaling component of mTOR, as well as to recapitulate human caners in mice to facilitate the drug screening and clinical trials in the future. As the whole body knockout of mTOR, mLST8 or Sin1 core subunits leads to embryonic lethality, to appreciate the exact role of these critical mTOR modulators in vivo, tissue-specific knockout or transgenic mouse models are urged to be generated. In addition, only limited mouse models are currently available, preventing the fully understanding of the physiological contribution of many members along this signaling pathway to cancer and other human pathological conditions. Thus establishing mouse models for all critical mTOR pathway components including its core complex components, upstream regulators and downstream targets, will greatly help to pinpoint their critical roles in various cellular processes leading to tumorigenesis. Notably, the recently developed CRISPR technique has provided an efficient and accurate method to generate engineered mice with cancer patient-derived hotspot mutations [252], which may not only bypass the embryonic lethality issue caused by gene ablation, but also evaluate how significant a certain cancer patient hot mutation contributes to tumorigenesis in a mouse model and might facilitate the test of various treatments specifically targeting this mutation. For example, we recently identified a oncogenic Sin1-R81T mutation that leads to hyper-activation of mTORC2 in a mouse xenograft model [20], it will be interesting to further examine whether the Sin1-R81T transgenic mice are prone to develop certain types of tumors.

More importantly, as a heterogeneous disease, cancer initiation and development are commonly driven by multiple genetic alterations or mutations. In addition, after the initial treatment, drug resistance is a commonly developed due to additional adaptive genetic alterations. In this scenario, to effectively cure cancer, targeted or combined cancer therapies emerge as more effective clinical application approaches. For example, application of both Cdk4 and MEK inhibitors not only achieves better treatment outcome, but also reduces drug resistance development in cancer patients [253]. Thus, compound mouse models will shed new lights into which combination of different oncogenic pathways along the PI3K/mTOR/Akt signaling cascade should be considered in a new combination therapy.

Finally, since the traditional radio- or chemo-therapy causes DNA damage that also alters the activation status of the mTOR pathway, it will be critical to examine whether cancer patients benefit from the combination therapy including radio- or chemo-therapy plus targeted inhibition of the mTOR pathway. To examine this hypothesis, genetic mouse models combined with radiation or chemo-drug treatments might need further testing in the future. There is no doubt that biochemical analysis, coupled with comprehensive structural and genetic approaches, significant improvement of our understanding of mTOR biology will be made, which eventually will facilitate the treatment of patients suffering from cancer characterized with aberrancies in the mTOR/Akt oncogenic signaling pathway.

Figure 3.

A summary of future perspectives to determine the physiological roles for additional members of the mTOR oncogenic pathway in tumorigenesis.

Highlights.

mTOR pathway component-related engineered mouse models are summarized.

Pathological alterations for discussed mTOR pathway components are outlined.

An oncogenic or tumor suppressor role is assigned for mTOR pathway components.

Further perspectives for generating additional mouse models are provided.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely apologize to all those colleagues whose important work was not cited in this paper owing to space limitations. They thank B. North, A. W. Lau, H. Inuzuka, L. Wan and other members of the Wei laboratory for critical reading and discussion of the manuscript. W.W. is an American Cancer Society (ACS) research scholar and a Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS) research scholar. P.L. is supported by grant 1K99CA181342. This work was supported in part by US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants to W.W. (GM094777 and CA177910).

Abbreviations

- mTOR

the mechanistic target of rapamycin or the mammalian target of rapamycin

- PIKK

phosphoinositide 3-kinase related protein kinase

- ATM

ataxia-telangiectasia mutated

- ATR

ataxia-telangiectasia and rad3-related

- DNAPK

DNA-dependent protein kinase

- Raptor

regulator-associated protein of mammalian target of rapamycin

- mLST8

mammalian lethal with sec-13 protein 8

- Rictor

rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR

- mSin1 (MAPKAP1)

mammalian stress-activated map kinase-interacting protein 1

- DEPTOR

DEP domain containing mTOR-interacting protein

- PRAS40

proline-rich Akt substrate 40 kDa

- Protor1/2

protein observed with rictor 1 and 2

- SGK

serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase

- 4E-BP1

eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E)-binding protein 1

- S6K

S6 kinase

- SREBP

sterol regulatory element-binding protein

- LKB1

liver kinase B1

- TBC1D7

tre2-bub2-cdc16 1 domain family, member 7

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- GAP

GTPase-activating protein

- BHD

Birt-Hogg-Dubé

- Rheb

ras homolog enriched in brain

- FLCN

folliculin

- KO

knockout

- Tg

transgenic

- ODC

ornithine decarboxylase

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- HSCs

hematopoietic stem cells

- IRS1

insulin receptor substrate 1

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor

- Grb10

growth factor receptor-bound protein 10

- FAS

fatty acid synthase

- ULK1

uncoordinated 51-like kinase 1

- Atg13

mammalian autophagy-related gene 13

- DAP1

death-associated protein 1

- TFEB

transcription factor EB

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- PH

pleckstrin homology

- PDK1

phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1

- Pten

phosphatase and tensin homologue

- APC

adenomatous polyposis coli

- PLD

phospholipase D

- REDD1

regulated in development and DNA damage responses 1

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Vezina C, Kudelski A, Sehgal SN. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. I. Taxonomy of the producing streptomycete and isolation of the active principle. The Journal of antibiotics. 1975;28:721–726. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.28.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heitman J, Movva NR, Hall MN. Targets for cell cycle arrest by the immunosuppressant rapamycin in yeast. Science. 1991;253:905–909. doi: 10.1126/science.1715094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown EJ, Albers MW, Shin TB, Ichikawa K, Keith CT, Lane WS, Schreiber SL. A mammalian protein targeted by G1-arresting rapamycin-receptor complex. Nature. 1994;369:756–758. doi: 10.1038/369756a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabatini DM, Erdjument-Bromage H, Lui M, Tempst P, Snyder SH. RAFT1: a mammalian protein that binds to FKBP12 in a rapamycin-dependent fashion and is homologous to yeast TORs. Cell. 1994;78:35–43. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90570-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sabers CJ, Martin MM, Brunn GJ, Williams JM, Dumont FJ, Wiederrecht G, Abraham RT. Isolation of a protein target of the FKBP12-rapamycin complex in mammalian cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1995;270:815–822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. Initiating cellular stress responses. Cell. 2004;118:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006;124:471–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inoki K, Corradetti MN, Guan KL. Dysregulation of the TSC-mTOR pathway in human disease. Nature genetics. 2005;37:19–24. doi: 10.1038/ng1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]