Abstract

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most aggressive malignancies in US adults. The experimental studies have found that antioxidant nutrients could reduce oxidative DNA damage, suggesting that these antioxidants may protect against pancreatic carcinogenesis. Several epidemiologic studies showed that dietary intake of antioxidants was inversely associated with the risk of pancreatic cancer, demonstrating the inhibitory effects of antioxidants on pancreatic carcinogenesis. Moreover, nutraceuticals, the anti-cancer agents from diet or natural plants, have been found to inhibit the development and progression of pancreatic cancer through the regulation of cellular signaling pathways. Importantly, nutraceuticals also up-regulate the expression of tumor suppressive miRNAs and down-regulate the expression of oncogenic miRNAs, leading to the inhibition of pancreatic cancer cell growth and pancreatic Cancer Stem Cell (CSC) self-renewal through modulation of cellular signaling network. Furthermore, nutraceuticals also regulate epigenetically deregulated DNAs and miRNAs, leading to the normalization of altered cellular signaling in pancreatic cancer cells. Therefore, nutraceuticals could have much broader use in the prevention and/or treatment of pancreatic cancer in combination with conventional chemotherapeutics. However, more in vitro mechanistic experiments, in vivo animal studies, and clinical trials are needed to realize the true value of nutraceuticals in the prevention and/or treatment of pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: nutraceutical, Pancreatic cancer, prevention, treatment, miRNA, epigenome

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer has remained one of the most aggressive malignancies for decades, with 46,420 new cases and almost 40,000 deaths estimated for 2014 in the USA (1). It has maintained its position as the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in US adults for years (1). Pancreatic cancer is fundamentally a disease initiated by the DNA damage caused by hereditary, smoking, or other lifestyle factors by chance. Since the acquired DNA damage is commonly induced by oxidants, the studies on the inhibitory effects of antioxidant nutrients on DNA damage and carcinogenesis have been broadly conducted. The experimental studies have found that antioxidant nutrients, functioning as anti-carcinogenic factors, could reduce oxidative DNA damage during the development of cancers, suggesting that these antioxidants may protect against carcinogenesis (2–5). Several epidemiologic studies have shown that dietary intake of antioxidant nutrients has been found to be inversely associated with the risk of pancreatic cancer, further demonstrating the inhibitory effects of antioxidants on pancreatic carcinogenesis (5–8). In addition, type II diabetes mellitus has been associated with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer, suggesting that the diet and glucose metabolism are involved in pancreatic carcinogenesis (9,10). Moreover, the anti-cancer agents from diet or natural plants have recently received much attention as nutraceuticals for cancer prevention and/or treatment. Importantly, emerging evidence shows that nutraceuticals could prevent the development and progression of pancreatic cancer, demonstrating the importance of nutraceuticals in the management of pancreas cancer.

The word “nutraceutical” was coined from “nutrition” and “pharmaceutical”. The term nutraceutical is applied to products that range from isolated nutrients, dietary supplements, and natural plant products. In recent years, an increasing number of studies have been conducted to investigate the inhibitory effects of nutraceuticals on cancers and the molecular mechanisms of action of nutraceuticals. The most frequently investigated nutraceuticals in pancreatic cancer include isoflavone genistein, biochanin A, curcumin, (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), indole-3-carbinol (I3C), 3,3′-diindolylmethane (DIM), resveratrol, lycopene, garcinol, apigenin, benzyl isothiocyanate (BITC), sulforaphane, triphendiol, metformin, thymoquinone (TQ), emodin, triptolide, plumbagin, vitamins, etc (Table 1). Isoflavones are mainly derived from soybeans. Genistein, daidzein, and glycitein are the three main isoflavones found in soybeans. Isoflavone genistein shows anti-oxidant and anti-cancer activities (11). Biochanin A is another isoflavone found in red clover or soy and is known to exert its anti-cancer effect on various cancers (12). Curcumin is a natural compound present in turmeric and possesses anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, and anti-cancer effects (13). EGCG is extracted from green tea and has antioxidant and anti-cancer properties (14). I3C and DIM are phytochemicals derived from cruciferous vegetables. I3C and DIM show inhibitory effects on carcinogenesis in various cancers (15). Both BITC and sulforaphane are also bioactive compounds from cruciferous vegetables and show anti-cancer activities (16,17). Resveratrol is a dietary compound from grapes and shows anti-carcinogenesis features through the up-regulation of tumor suppressor genes (18). Lycopene is the red pigment in tomatoes and has shown its chemopreventive potential in cancers (19). Garcinol is extracted from the rind of the fruit of Garcinia indica and shows anti-carcinogenesis activity (20). Apigenin is a dietary flavonoid possessing potential against cancers (21). Triphendiol (NV-196) is a synthetic isoflavene and shows inhibitory effects on pancreatic cancer (22). Metformin is a first-line drug for diabetes, and the natural source of metformin is Galega officinalis (23). TQ is isolated from the seeds of Nigella Sativa and shows some efficacy against pancreatic cancer (24). Emodin is an active constituent isolated from the root of Rheum Palmatum and has anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer effects (25). Plumbagin is a quinoid constituent isolated from the roots of the medicinal plant Plumbago zeylanica L (26). The in vitro experimental and in vivo animal studies have shown that these nutraceuticals have beneficial effects against pancreatic cancer through the regulation of cellular signaling, miRNAs, and epigenome.

Table 1.

Frequently investigated nutraceuticals in pancreatic cancer

| Nutraceutical | Structure | Sources | Main Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

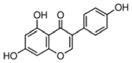

| Genistein |

|

Soybeans, lupin, fava beans, kudzu, psoralea | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor, antioxidant, binding to ER, anti-cancer |

| Biochanin A |

|

Red clover, soy, alfalfa sprouts, peanuts, chickpea, other legumes | As a phytoestrogen, fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor, antioxidant, anti- cancer. |

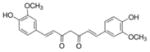

| curcumin |

|

Turmeric from Curcuma longa | Antioxidant, anti-inflammation, anti- cancer |

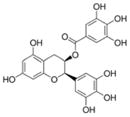

| (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate |

|

Green tea, white tea | Antioxidant, DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, anti-atherogenic, anti-cancer |

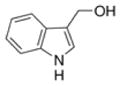

| Indole-3-carbinol |

|

Cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, kale | Antioxidant, anti-atherogenic, anti-cancer |

| 3,3′-diindolylmethane |

|

Cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, kale | Derived from the digestion of indole-3-carbinol. Antioxidant, anti-cancer |

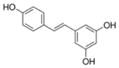

| Resveratrol |

|

Grapes, Vitis vinifera, labrusca, mulberries, and peanuts. Highest concentration is in the skin. | Antioxidant, anti-atherogenic, anti-cancer |

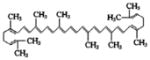

| Lycopene |

|

Tomatoes and other red fruits and vegetables such as red carrots, watermelons, papayas | Antioxidant, anti-cancer |

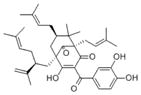

| Garcinol |

|

The rind of Garcinia indica fruit | Inhibitor of histone acetyltransferases (HATs) p300, anti-inflammation, antioxidant, anti-cancer, anti-bacterial |

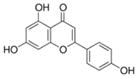

| Apigenin |

|

Many fruits and vegetables such as parsley, celery, artichokes | Casein kinase II (CK2) inhibitor, anti-inflammation, anti-cancer |

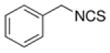

| Benzyl isothiocyanate |

|

Cruciferous vegetables | Antioxidant, anti-cancer |

| Sulforaphane |

|

Cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, Brussels sprouts or cabbages | Anti-microbial, anti-cancer |

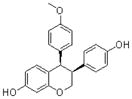

| Triphendiol |

|

A synthetic isoflavene | Broadly cytostatic and cytotoxic against most forms of human cancer cells |

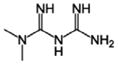

| Metformin |

|

Plant Galega officinalis | Anti-diabetes, anti-cancer |

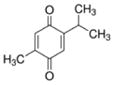

| Thymoquinone |

|

Plant Nigella sativa | Anti-epileptic effects, analgesic, anticonvulsant, HDAC inhibitor, anti-cancer |

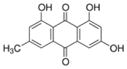

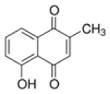

| Emodin |

|

Root of Rheum palmatum, buckthorn, Japanese knotweed | 11β-HSD1 inhibitor, anti-cancer |

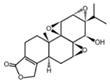

| Triptolide |

|

Thunder God Vine, Tripterygium wilfordii | Immunosuppression, anti-inflammation, anti-cancer |

| Plumbagin |

|

Plumbago, Drosera, Nepenthes, black walnut drupe | Anti-inflammation, anti-microbial, anti-atherosclerosis, anti-malarial, anti-cancer |

NUTRIENTS AND NUTRACEUTICALS FOR PANCREATIC CANCER PREVENTION

Environmental and lifestyle factors are believed to play an important role in pancreatic carcinogenesis. It has been estimated that obesity, diabetes, and their associated chronic conditions contribute to the development of, at least, 30% of pancreatic cancer. Therefore, the nutrients in the diet and the dietary supplements are critical for the prevention of pancreatic cancer. A recent study from Mayo Clinic showed a significant inverse association (p < 0.05) between pancreatic cancer and nutrient or supplement intake including magnesium, potassium, selenium, α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lutein and zeaxanthin, niacin, total αtocopherol, total vitamin A activity, vitamin B6, and vitamin C (6). These results suggest that most nutrients obtained through consumption of fruits and vegetables may reduce the risk of pancreatic cancer development. Consistent with these results, another recent study also showed a significant inverse association between dietary selenium and the risk of pancreatic cancer (p = 0.01) (7). Because fruits and vegetables may decrease the risk of pancreatic cancer, a study has been conducted to investigate the association between dietary carotenoids and pancreatic cancer risk. It has been found that lycopene, obtained mainly through the consumption of tomatoes, was associated with a 31% reduction in pancreatic cancer risk among men, suggesting that a diet rich in tomatoes and tomato-based products with high levels of lycopene could reduce pancreatic cancer risk (27). This result is consistent with another study showing that a low level of serum lycopene was strongly associated with pancreatic cancer (28), suggesting the beneficial effects of fruits and vegetables in lowering the risk of pancreatic cancer. However, in the Netherlands Cohort Study, no association between pancreatic cancer risk and high consumption of vegetables/fruits, carotenoids, and vitamin supplements was observed (29). The inconsistent results could be due to different analysis methods and geographic differences.

It is known that folate deficiency could induce DNA breaks and alter cellular capacity for mutation and epigenetic methylation. Studies have been conducted to investigate the potential protective role of plasma concentrations of folate, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, and homocysteine in pancreatic carcinogenesis. It has been found that among participants who get folate, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 exclusively through dietary sources, there is an inverse relationship between pancreatic cancer risk and circulating folate, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 (30), suggesting the protective effects of these nutrients against the development of pancreatic cancer. Moreover, a combination of several chemopreventive agents for pancreatic cancer chemoprevention has been investigated because carcinogenesis comprises genetic and epigenetic alterations and a single agent may not be sufficient to prevent cancer that is mediated through the regulation of many signaling networks. The combination of aspirin, curcumin, and sulforaphane for the prevention of pancreatic cancer in hamsters has been reported (31). This study showed that aspirin and curcumin could be formulated in nanoparticles and that the effective dosages were decreased by 10-fold when combined with sulforaphane compared with the free form in the mixture. The formulated aspirin and curcumin nanoparticles are stable for oral administration, no toxicity, and more effective for chemoprevention of pancreatic cancer (31).

It is also important to note that diabetes mellitus has been associated with increased risk of pancreatic cancer. Diabetic patients with insulin resistance who have received insulin therapy had a two-fold increased risk in subsequent development of pancreatic cancer (32). This finding supports the idea that insulin and insulin-like growth factor receptors (IGFRs) are involved in pancreatic carcinogenesis (33). Interestingly, metformin, one of the nutraceuticals and the first-line of drugs for diabetes, could inhibit IGF signaling (34), suggesting that metformin could also inhibit the development of pancreatic cancer. A hospital-based case-control study was conducted at M. D. Anderson Cancer Center from 2004 to 2008 involving 973 patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma (including 259 diabetic patients) and 863 controls (including 109 diabetic patients). The study found that diabetic patients who had taken metformin had a significantly lower risk of pancreatic cancer compared with those who had not taken metformin (35). This study also showed that diabetic patients who had taken insulin or insulin secretagogues had a significantly higher risk of pancreatic cancer compared with diabetic patients who had not taken these drugs. These results suggest that the use of metformin could prevent the development of pancreatic cancer in patients diagnosed with diabetes. All results described above suggest the beneficial effects of nutrients and nutraceuticals in the prevention of pancreatic cancer.

The investigation on the nutritional modulation of carcinogenesis started several decades ago. However, no significant advances were achieved until the human genome project in 2001. From then on, armed with the information of human genome and the advances of new post-genomic technologies including DNA methylation array, mRNA microarray, miRNA array, proteomic profiling, and metabolomics analysis, critical studies have been initiated. Growing body of studies has been conducted to elucidate the molecular effects of dietary constituents on genome-wide multiple-level gene expression and metabolic profiles, exhibiting the arrival of post-genomic era in nutrition and cancer research (36–38). The results from these studies are exciting and the new biomarkers have been identified through the dietary intervention studies (39,40). Emerging evidence has demonstrated that the interactions between genes/miRNAs and nutrients or nutraceuticals are significantly implicated in the processes of cancer development and progression (41,42). The results from gene/miRNA expression and methylation profiling together with molecular mechanistic experiments provided the information regarding the cellular signal transduction networks regulated by nutrients or nutraceuticals, which are becoming important for designing novel strategies for the prevention and/or treatment of pancreatic cancer.

NUTRACEUTICALS FOR PANCREATIC CANCER TREATMENT

In recent years, the studies on nutraceuticals for the treatment of pancreatic cancer have been largely increased due to the realization of the beneficial effects of nutraceuticals in the prevention of pancreatic cancer. Growing evidence has shown that nutraceuticals could prevent the progression of pancreatic cancer through the modulation of cellular signaling, miRNAs, and epigenome. Some of this evidence are discussed in the following paragraphs.

Inhibition of Pancreatic Cancer through the Regulation of Cellular Signaling

Targeting EGFR signaling

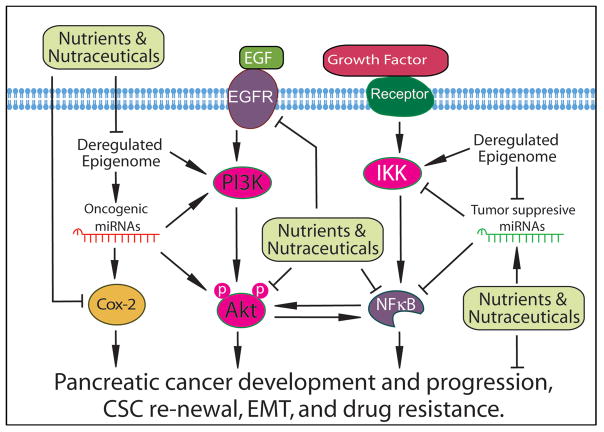

The alterations of the EGFR gene in pancreatic cancer include over-expression, mutation, and other genetic and epigenetic events, leading to the activation of EGFR signaling. The activation of EGFR signaling causes the development and progression of pancreatic cancer and induces the resistance of pancreatic cancer cells to chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Clinical and experimental data has shown that most pancreatic cancers exhibit up-regulated expression of EGF and EGFR and that the up-regulated EGFR signaling is significantly associated with the advanced pancreatic cancer and poor survival of patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer (43). Therefore, targeting EGFR signaling is an important strategy for the treatment of pancreatic cancer (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The effects of nutraceuticals on the development and progression of pancreatic cancer though the regulation of miRNA and epigenome mediated cellular signaling network.

By using microarray technology, isoflavone genistein has been found to inhibit the expression of EGFR AKT2, CYP1B1, NELL2, SCD, DNA ligase III, and Rad in pancreatic cancer, suggesting the inhibitory effect of genistein on EGFR signaling (44). The effects of another natural agent, plumbagin, on EGFR signaling in pancreatic cancer have also been tested. It has been found that plumbagin treatment could down-regulate EGFR, pSTAT3 at Tyr705, pSTAT3 at Ser727, DNA binding of STAT3, and interaction of EGFR with STAT3 in PANC-1 pancreatic cancer cells and xenograft tumors, leading to the inhibition of pancreatic cancer cell growth in vitro and decreased weight/volume of implanted tumor in vivo (45). Plumbagin treatment also inhibited the phosphorylation and DNA-binding activity of NF-κB, and down-regulated STAT3 and NF-κB downstream target genes including cyclin D1, MMP-9 and Survivin (45). These results suggest that plumbagin could be a potent agent for the treatment of pancreatic cancer through the regulation of EGFR and NF-κB signaling.

To enhance the anti-cancer effects of chemotherapeutics on pancreatic cancer, several natural agents have been tested in combination treatments for targeting EGFR signaling. It has been found that isoflavone genistein could significantly enhance EGFR inhibitor erlotinib-induced growth inhibition and apoptosis in BxPC-3, CAPAN-2, and AsPC-1 pancreatic cancer cells (46). The combination treatment with genistein and erlotinib showed much more inhibition of EGFR, phosphorylated Akt, NF-κB, and survivin compared with the erlotinib treatment alone, suggesting the beneficial effects of isoflavone genistein in the combination treatment of EGFR activated pancreatic cancer. Moreover, 3,3′-diindolylmethane (DIM) also potentiated the anti-cancer activity of EGFR inhibitor erlotinib in pancreatic cancer cells. The combination treatment with erlotinib and DIM significantly inhibited EGFR phosphorylation, cell proliferation and clonogenic growth compared to the treatment with either agent alone (47). Furthermore, animal studies have shown that DIM in combination with erlotinib exerted increased inhibitory effects on tumor growth in vivo compared to either agent alone, suggesting that nutraceutical DIM combined with erlotinib could be useful for the combination treatment of pancreatic cancer with activated EGFR signaling.

Targeting COX-2 signaling

Cyclooxygenase (COX) is an enzyme which catalyzes the production of prostaglandins (PGE). PGE promotes cell proliferation; therefore, COX plays an important role in the control of cancer cell proliferation through the regulation of PGE. COX-2 is more relevant to the growth of cancer cells because it is usually absent in normal tissues and up-regulated in cancer cells. The synthesis of COX-2 could be induced during inflammatory and carcinogenic processes by cytokines, growth factors, and other cancer promoters. It has been found that most pancreatic cancer cell lines express up-regulated COX-2 (48). Moreover, strong expression of COX-2 protein has been observed in 44% of pancreatic carcinoma tissues and moderate expression of COX-2 has been found in 46% of pancreatic carcinoma tissues. However, benign tumors only showed weak expression or no expression of COX-2 (49). These results suggest the importance of COX-2 in pancreatic carcinogenesis. Therefore, targeting COX-2 signaling could be another promising strategy for the treatment of pancreatic cancer.

Several COX-2 inhibitors have been developed and shown to inhibit pancreatic cancer growth. Among them, celecoxib which inhibits only COX-2 is more desirable for clinical use. Moreover, several nutraceuticals have been tested for the inhibition of inflammation and carcinogenesis through the regulation of COX-2 (Figure 1). Curcumin showed strong inhibitory effects on the expression of COX-2, EGFR, NF-κB, ERK1/2, lipooxygenase (LOX), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), leading to the inhibition of pancreatic cancer and inflammation (50,51). Importantly, curcumin synergistically potentiated the growth inhibitory and pro-apoptotic effects of celecoxib in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells (52). The enhanced growth inhibition has been found to be associated with significant down-regulation of COX-2 expression under the combination treatment condition. Curcumin also increased the inhibitory effect of gemcitabine on pancreatic cancer cell proliferation, and potentiated pro-apoptotic activity of gemcitabine through the down-regulation of COX-2 and p-ERK1/2 (53). In addition, curcumin analog CDF with higher bioavailability has been synthesized and the effect of CDF on COX-2 expression and pancreatic cancer growth have been tested. It has been found that CDF significantly inhibited the expression of COX-2, NF-κB, and VEGF, leading to the inhibition of growth of pancreatic cancer cells with cancer stem cell (CSC) signatures (54,55). These results suggest that curcumin and its analogs could be useful for the inhibition of pancreatic cancer growth mediated through the targeting of COX-2 signaling. Moreover, another nutraceutical resveratrol has been found to potentiate the effects of gemcitabine through the regulation of COX-2 signaling, leading to the inhibition of pancreatic cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis (56). In addition, triptolide could down-regulate COX-2 signaling, resulting in reduced growth and angiogenesis of pancreatic cancer in mouse xenograft model (57). Moreover, triptolide could also cooperate with cisplatin to induce more apoptosis in gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer (58). Therefore, targeting COX-2 by these nutraceuticals could be a therapeutic strategy for achieving better treatment outcomes for pancreatic cancer.

Targeting PI3K/Akt signaling

The activation of EGFR has been known to activate PI3K which further phosphorylates and activates Akt, leading to the activation of PI3K/Akt signaling. The activation of Akt promotes cell survival through the inhibition of apoptosis mediated by down-regulation of pro-apoptotic molecules including Bad, Forkhead transcription factors, and caspase-9 (59). Akt could also activate NF-κB pathway through the regulation of molecules in the NF-κB pathway, leading to the survival of cancer cells (Figure 1). The activation of PI3K/Akt signaling has been found in most pancreatic cancers and the up-regulated Akt signaling has been found to be associated with high tumor grade and poor prognosis of pancreatic cancer, suggesting that PI3K/Akt signaling is critical for the survival of pancreatic cancer cells.

The effect of several nutraceuticals on the PI3K/Akt pathway in pancreatic cancer cells has been tested. It has been found that EGCG from green tea could up-regulate PTEN expression and down-regulate the Akt phosphorylation (60). Similarly, resveratrol from grapes inhibited cell viability, suppressed colony formations, and induced apoptosis through the inhibition of PI3K/Akt signaling, resulting in the inhibition of pancreatic tumor growth in mice (61). Moreover, resveratrol decreased the level of p-Akt and regulated the expression of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) related genes (E-cadherin, N-cadherin, vimentin), MMP-2, and MMP-9, leading to the suppression of pancreatic cancer migration and invasion (62). In addition, benzyl isothiocyanate also showed its inhibitory effects on the growth of implanted BxPC-3 tumor in xenografts in mice through the down-regulation of pAkt and up-regulation of apoptotic genes, Bim, p27, and p21 (63). Similarly, sulforaphane also inhibited pAkt and induced the expression of p21 and p27, leading to cell cycle arrest and the induction of apoptosis of pancreatic cancer (64). Moreover, biochanin A, curcumin, and curcumin analogs (FLLL11, FLLL12, and CDF) could also inhibit the activation of Akt signaling, leading to the induction of apoptosis and the inhibition of pancreatic cancer cell survival and invasion (65–68).

More importantly, nutraceuticals could also enhance the anti-cancer effects of conventional therapeutics through down-regulation of Akt signaling. Isoflavone genistein has been found to potentiate the anti-cancer activity of erlotinib through the inhibition of EGFR and Akt activation in pancreatic cancer cells, suggesting that the combination treatment with erlotinib and genistein could be a novel strategy for pancreatic cancer therapy (46). Genistein also enhanced the anti-cancer activity of gemcitabine via significant inhibition of Akt activity (69). Moreover, apigenin in combination with gemcitabine exerted more inhibitory effects on pancreatic cancer cell proliferation compared to either agent alone. Apigenin decreased the levels of pAkt and abrogated gemcitabine-induced pAkt, leading to the significant inhibition of cell proliferation in combination treatment (70,71). By targeting Akt signaling, apigenin also down-regulated the expression of glucose transporter 1 (GLUT-1), one of the Akt target genes (72), suggesting the inhibitory effects of apigenin on Akt signaling. In addition, emodin also inhibited the activation of Akt. Treatment with gemcitabine combined with emodin could efficiently suppress tumor growth in mice inoculated with pancreatic cancer cells via the reduction of pAkt level and the induction of caspase-9 and caspase-3 activation (73). These results demonstrated that inactivation of Akt by nutraceuticals could enhance the efficacy of conventional therapies for the treatment of pancreatic cancer.

Targeting NF-κB signaling

It is well known that NF-κB signaling is critical for the control of cell growth, apoptosis, inflammation, stress response, and other cellular processes (74). NF-κB can be activated through the Akt activation or the IKK mediated IκBα degradation, leading to NF-κB nuclear translocation and binding to DNA. The binding of NF-κB to the promoters of target genes enhances the expression of survivin, MMP-9, uPA, and VEGF that are critical for cell growth, apoptosis, invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis of cancer cells. It has been found that pancreatic cancer tissues and cell lines express significantly up-regulated NF-κB, suggesting that the activation of NF-κB contributes to the carcinogenesis of pancreatic cancer (75). Moreover, the constitutively activated or chemotherapeutic agent-induced NF-κB is associated with chemoresistance, invasion and metastasis of pancreatic cancer. Therefore, targeting NF-κB could be a promising strategy for the treatment of pancreatic cancer.

Benzyl isothiocyanate from cruciferous vegetables could inhibit the expression of NF-κB in BxPC-3 pancreatic cancer cells (76,77). Sulforaphane also derived from cruciferous vegetables could eliminate pancreatic CSCs by down-regulation of NF-κB activation, leading to the inhibition of clonogenicity, spheroid formation, ALDH1 activity, and migratory capacity (78). Triptolide also inhibited ALDH1 and NF-κB activity, migratory activity, and EMT/CSC features, leading to the reversal of EMT and CSC characteristics (79). In addition, thymoquinone and garcinol could inhibit the constitutive and TNF-α-mediated activation of NF-κB and down-regulate NF-κB target genes, MMP-9, VEGF, IL-8, and PGE2, leading to the growth inhibition of pancreatic cancer cells (80–82).

Several nutraceuticals targeting NF-κB have been used to enhance the anti-tumor effects of chemotherapeutic agents. It has been found that treatment with cisplatin, docetaxel, doxorubicin, and gemcitabine could induce NF-κB activity (69,83,84). However, the activation of NF-κB by these agents was completely abrogated by the isoflavone genistein treatment in pancreatic cancer cells (69,83–85). Experimental studies also showed that down-regulation of NF-κB by nutraceutical sulfasalazine, apigenin, curcumin, or emodin could sensitize pancreatic cancer cells to chemotherapeutic agents (71,86–91). Apigenin could down-regulate NF-κB signaling (92,93) and enhance anti-tumor efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents in pancreatic cancer (71,88). Curcumin could decrease the expression of NF-κB p50, NF-κB p65, Sp1, Sp3, and Sp4 transcription factors that are overexpressed in pancreatic cancer cells (94), and sensitize pancreatic cancer to gemcitabine and radiation in vitro and in vivo (87,95). Emodin could also suppress NF-κB signaling (96) and sensitize gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells to gemcitabine therapy via inhibition of MDR-1, NF-κB and its target genes, VEGF, MMP-2, MMP-9, and eNOS (89–91,97). All these results demonstrate that targeting NF-κB signaling by nutraceuticals could enhance the anti-cancer effects of conventional therapies for the treatment of pancreatic cancer; however, proof-of-concept and therapeutic clinical trials must be done to validate the importance of nutraceuticals in the treatment design for pancreas cancer.

Numerous studies have shown that curcumin has low systemic bioavailability. To increase the bioavailability, nanoparticle encapsulated formulation of curcumin, liposomal formulation of curcumin, and curcumin analogs (GO-Y030 and CDF) have been developed. The formulated curcumins and the analog significantly inhibited the activation of NF-κB and down-regulated the expression of NF-κB target genes, IL-6, IL-8, and COX-2 (66,98–101), suggesting higher bioavailability and anti-cancer efficacy of these formulated curcumins and curcumin analogs. These formulated curcumins and curcumin analogs could be useful in combination with chemotherapeutics for enhancing the anti-cancer efficacy of chemotherapeutics in the treatment of pancreatic cancer.

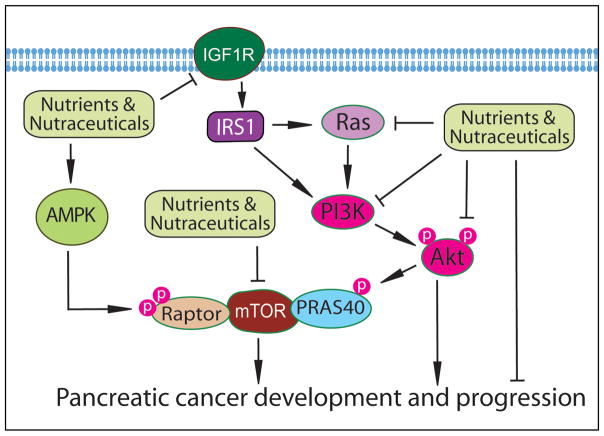

Targeting AMPK-mTOR signaling pathway

The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is critically involved in the control of the energy status of a cell where glucose and amino acids regulate the release of insulin. It has been found that the inhibition of AMPK in pancreatic β-cells by high glucose activates the mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) signaling (102) which is another regulator for nutritional status in cells, suggesting the importance of AMPK-mTOR signaling in pancreatic development and differentiation. In addition, the activated Akt signaling in pancreatic cancer cells could up-regulate its down-stream mTOR signaling, leading to the survival of pancreatic cancer cells. Indeed, the constitutively activated mTOR pathway is frequently observed in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and chronic pancreatitis (103). Moreover, mTOR signaling also plays important roles in the maintenance of pancreatic cancer stem cells through stemness-related regulations (104). Therefore, targeting AMPK-mTOR signaling by nutraceuticals could be a promising strategy for the treatment of pancreatic cancer (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The effects of nutraceuticals on the AMPK-mTOR and IGF signaling.

In an in vivo clinical study, it was found that diabetic patients with pancreatic cancer who used metformin for their diabetes treatment have an improved survival (105). Moreover, in vitro studies showed that metformin exerts anti-cancer activity through the inhibition of mTOR signaling via AMPK-dependent and -independent pathways in pancreatic cancer cells (106). Low concentrations of metformin also selectively inhibit the proliferation of CD133+ cancer stem-like cell in pancreatic cancer through the suppression of mTOR signaling (107). In addition, EGCG from green tea has been found to significantly inhibit the proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells and induce apoptotic cell death (108). These anti-cancer effects of EGCG on pancreatic cancer cells are mediated through the up-regulation of PTEN expression and the down-regulation of phospho-Akt and phospho-mTOR, suggesting the molecular regulation of EGCG on Akt/mTOR signaling. Importantly, the targeted inhibition of mTOR signaling has been found to enhance radiosensitivity in pancreatic carcinoma cells (109), suggesting that the suppression of mTOR signaling by nutraceuticals such as metformin and EGCG could potentiate the anti-cancer activity of radiation therapy for achieving better treatment outcomes in patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

Targeting other signaling pathways

The nutraceuticals are also known to inhibit the growth of pancreatic cancer cells through the regulation of other cellular signaling pathways (Figure 2). As described earlier, metformin down-regulates IGF signaling, leading to the inhibition of pancreatic cancer growth (34). K-ras signaling is commonly activated by K-ras mutation in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) and late stage of pancreatic cancer, suggesting that the activated K-ras signaling drives the development and progression of pancreatic cancer (110). It has been found that EGCG from green tea could suppress the expression of the K-ras gene and, thereby, inhibits the growth of pancreatic cancer cells (111). EGCG also down-regulates the expression of CSC marker genes (Nanog, c-Myc and Oct-4) and self-renewal capacity of pancreatic CSCs through the inhibition of hedgehog signaling (112). Similarly, sulforaphane and resveratrol also inhibit pancreatic CSC stemness and pancreatic cancer cell growth by regulating the CSC marker genes and hedgehog signaling (113,114). Apigenin is known to inhibit the expression of HIF-1α, GLUT-1, and VEGF mRNA and protein in pancreatic cancer cells (72,115). Benzyl isothiocyanate has been found to down-regulate the STAT3 signaling and induce the phosphorylation of ERK and JNK, leading to the induction of apoptosis and inhibition of pancreatic cancer cell growth (116,117). Triptolide also regulates ERK and induce apoptosis in pancreatic cancer (118). Similarly, thymoquinone is known to sensitize gemcitabine and oxaliplatin-induced apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells with down-regulation of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, survivin, and XIAP (119). These findings suggest that nutraceuticals could inhibit pancreatic cancer cells or CSCs through the modulation of CSC related hedgehog signaling and apoptotic signaling pathways.

Inhibition of Pancreatic Cancer by Targeting miRNAs

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are noncoding RNAs which contain only 18 to 22 nucleotides. Although miRNAs do not code for any proteins or peptides, miRNAs are known to down-regulate the expression of their target genes. In this way, miRNAs control cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis and other cellular processes through the regulation of different cellular signaling pathways. Importantly, miRNAs also play critical roles in the development and progression of various cancers including pancreatic cancer. The miRNAs expression profiles of pancreatic cancers have been achieved by conducting miRNA array analysis using pancreatic cancer and normal pancreatic epithelial cells, tissues, and serum. The aberrant expressions of several miRNAs have been found in pancreatic cancer cells. Pancreatic cancer cells express significantly higher levels of miR-21 and miR-221, and reduced levels of miR-34, miR-200, and let-7. These miRNAs are known to regulate several important molecules including EGFR, p53, Akt, NF-κB, TGF-β, p16INK4A, BRCA1/2, K-ras, etc, which are aberrantly expressed in pancreatic cancer (120). By regulating these critical molecules and their cellular signaling, the miRNAs are known to control DNA repair, cell cycle, apoptosis, invasion and metastases of pancreatic cancer cells. Therefore, these aberrantly expressed miRNAs could be promising targets for the treatment of pancreatic cancer.

It is well known that overexpression of miR-21 contributes to chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Indole-3-carbinol has been found to down-regulate the expression of miR-21 and consequently increased the expression of its target PDCD4, leading to increased sensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells to gemcitabine (121). Similarly, resveratrol also decreased the expression of miR-21 and inhibited BCL-2 expression in PANC-1, CFPAC-1 and MiaPaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cells (122). Garcinol could also synergize with gemcitabine to inhibit cell proliferation and induce apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells through the down-regulation of miR-21 expression (123).

The miR-221 is another miRNA that is highly expressed in pancreatic cancer. It has been found that the treatment of pancreatic cancer cells with isoflavone mixture G2535, formulated 3,3′-diindolylmethane (BR-DIM), or synthetic curcumin analogue CDF could down-regulate the expression of miR-221 and consequently up-regulate the expression of PTEN, p27kip1, p57kip2, and PUMA, leading to the inhibition of cell proliferation and migration of MiaPaCa-2 and PANC-1 pancreatic cancer cells (124). Benzyl isothiocyanate could also reduce the levels of miR-221, and induce the expression of miR-375 which is down-regulated in pancreatic cancer patients (125).

The expression of miRNA let-7, miR-200, and miR-146a are commonly down-regulated in pancreatic cancer, and could regulate EMT and CSC signature genes. It has been found that DIM and isoflavone significantly up-regulated the expression of miR-200 family in EMT-type MiaPaCa-2 cells (126). DIM or isoflavone also increased epithelial marker E-cadherin and decreased mesenchymal markers, ZEB1, vimentin and slug, suggesting that these nutraceuticals could revert the EMT phenotype. More importantly, the sensitivity of EMT-type cells to gemcitabine was significantly increased after miR-200b transfection or treatment of cells with DIM or isoflavone (126). These results clearly demonstrate that the nutraceuticals, DIM or isoflavone, could enhance the sensitivity of gemcitabine-resistant EMT-type cells to gemcitabine through the regulation of miR-200. Moreover, DIM and isoflavone also induced miR-146a expression and subsequently reduced EGFR, MTA-2, IRAK-1, and NF-κB expression, resulting in the inhibition of pancreatic cancer cell invasion (127). Isoflavone also suppressed pancreatic cancer cell proliferation, migration, invasion, EMT phenotype, and pancreatosphere formation capacity through the up-regulation of let-7 and miR-200 families, and the down-regulation of CSC marker CD44 and EpCAM, suggesting that miRNA mediated EMT and CSC signatures could be inhibited by isoflavone (128).

In addition, the effects of curcumin analog CDF on miRNA expressions in pancreatic cancer cells with EMT and CSC signatures have also been tested. It has been found that CDF could significantly inhibit the expression of oncogenic miR-21 and could also up-regulate the expression of several tumor suppressive miRNAs including miR-26a, miR-101, miR-146a, miR-200 family, and let-7 family (55,129). By regulating the expression of miRNAs, CDF significantly inhibits the sphere formation capacity of pancreatic cancer cells, increases disintegration of pancreatospheres, and down-regulates the expression of CSC marker genes in gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells (55). Further studies have shown that CDF could increase drug sensitivity and suppress tumor growth and aggressiveness of pancreatic cancer through the regulation of miRNA-mediated CSC signature genes, and the deregulation of EZH2, Notch-1, VEGF, IL-6, and Akt signaling pathways (55,66,129–131), suggesting the inhibitory effects of CDF on pancreatic CSCs and overcoming drug resistance via miRNA regulation. Interestingly, metformin, a natural agent for the treatment of diabetes, also increased the expression of tumor suppressive miRNAs including let-7a, let-7b, miR-26a, miR-101, miR-200b, and miR-200c, and decreased the expression of CSC marker genes including CD44, EpCAM, EZH2, Notch-1, Nanog and Oct4 (132). By modulating the miRNA-mediated CSC signaling, metformin significantly inhibited cell proliferation, invasion, and sphere-forming capacity in both gemcitabine-sensitive and gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells (132). These findings further support the inhibitory effects of nutraceuticals on miRNA-regulated EMT and CSC signaling (Figure 1).

In addition, studies have also shown that nutraceuticals could regulate the expression of various miRNAs in pancreatic cancer. It has been found that isoflavone genistein could also suppress cell growth, induce apoptosis, and inhibit invasion of pancreatic cancer cells through the inhibition of miR-27a (133). Curcumin could up-regulate miRNA-22 and down-regulate miRNA-199a, leading to the inhibition of pancreatic cancer cell growth (134). Triptolide could increase the expression of miR-204 and decrease the expression of miR-204 target Mcl-1, leading to apoptotic cell death of pancreatic cancer cells (135). Triptolide also induced the expression of miR-142-3p and inhibited the expression of its target HSP70 (136).

All the findings described above suggest that nutraceuticals could inhibit the growth of pancreatic cancer cells, pancreatic CSCs and EMT-type cells through the deregulation of miRNAs, and thus nutraceuticals could be very useful for the prevention and/or for the treatment of pancreas cancer preferably in combination with conventional therapeutics.

Targeting Epigenome for Pancreatic Cancer Treatment

Epigenome contains a profile of the chemical changes to the DNA and histone proteins within an individual, and the changes could be heritable as well. The epigenetic chemical changes could alter the structure of chromatin and, thereby, the function of the genome. The most frequent epigenetic changes include DNA methylation and histone modifications with methylation and acetylation. These epigenetic regulations alter the expression of genes without any changes in the DNA sequences. By regulating gene expression, epigenome controls organ development, tissue differentiation, and cell survival. The genome within an individual is more static; however, the epigenome can be altered by environmental conditions such as foods and pollutions. Therefore, the alterations in epigenome could be regulated by nutraceuticals for the inhibition of cancer development and progression.

It is important to note that pre-cancerous cells undergo aberrant epigenetic regulation, leading to the development of cancers. In pancreatic pre-cancerous and cancer cells, the epigenome precedes multiple alterations and regulations, which are the molecular basis of carcinogenesis and aggressiveness of pancreatic cancer. Among the epigenetic regulations, altered histone modification and DNA methylation are mostly observed in pancreatic cancer. DNA methylation and histone modification critically affect the transcription of genes. In histone modification, acetylation and methylation of histones regulate gene expression. The altered histone acetylation and methylation in a specific gene could cause activation of oncogenes and inactivation of tumor suppressors. The methylation of DNA sequences in promoters of genes obstructs transcriptional activators, leading to the down-regulation of gene expression. Importantly, DNA methylation in the promoter region of miRNA genes could also inhibit the expression of specific tumor suppressive miRNAs, leading to the up-regulation of oncogenic targets of these miRNAs (Figure 1). The up-regulated oncogenic signaling caused by altered histone modification and DNA methylation could promote carcinogenesis and the progression of pancreatic cancer.

It has been found that nutrients in the diet can reverse or change epigenetic regulation such as DNA methylation and histone modifications (137). Because pancreatic carcinogenesis is known to be regulated by genetic or epigenetic mechanisms, epigenetic regulations using nutraceuticals could prevent carcinogenesis and control the progression of pancreatic cancer (137,138). Several enzymes such as histone deacetylases (HDACs), histone acetyltransferases, and DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) play important roles in epigenetic regulations. It has been found that pancreatic cancer cells overexpress histone deacetylases, giving rise to epigenetic patterns of chemoresistance and aggressiveness (139,140). Therefore, targeting HDACs is important in the inhibition of pancreatic cancer growth through epigenetic regulations. Pancreatic cancer cells also express high levels of DNMTs, which could lead to DNA methylation in tumor suppressor genes and the inactivation of tumor suppressor (141). Several nutraceuticals have been shown to inhibit HDACs and DNMTs, suggesting the role of nutraceuticals in the inhibition of pancreatic cancer development and progression through deregulating HDACs and DNMTs.

Isoflavone genistein from soybeans could epigenetically up-regulate the expression of tumor suppressor genes and miRNAs by modulating DNA methylation and chromatin configuration, leading to the inhibition of various cancers (142,143). Type 2 diabetes is a result of chronic insulin resistance and loss of functional pancreatic β-cells. Type 2 diabetes is associated with the development of pancreatic cancer. Therefore, strategies to preserve β-cells could prevent the occurrence of pancreatic cancer. Isoflavone genistein has been found to protect β-cells at physiologically relevant concentrations through the epigenetic regulation of cAMP/PKA signaling (144), suggesting the inhibitory effect of genistein on pancreatic carcinogenesis through epigenetic regulation. Equol is an isoflavonoid metabolized from daidzein which is a type of isoflavone. Coumestrol is a natural phytochemical found in soybeans. It has been found that the DNA sequences of c-H-ras proto-oncogene could be hypermethylated in neonatal rats exposed to coumestrol and equol, leading to the inhibition of c-H-ras expression (145). This phenomenon is consistent with epidemiologic studies showing that equol may have anti-carcinogenic effects.

Curcumin could also mediate epigenetic modulation of genes and miRNA expressions. A phase II clinical study has shown the benefit of curcumin in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer through epigenetic modulation of target genes (146). It was found that curcumin may function as an epigenetic agent which could interact with HDACs, histone acetyltransferases, DNA methyltransferase-1, and several miRNAs to mediate its biological activity (146), leading to the inhibition of pancreatic cancer. Histone methyltransferase (EZH2) is a critical epigenetic regulator and plays important roles in the control of cell proliferation, apoptosis, and CSC function. Curcumin analog CDF has been shown to down-regulate the expression of EZH2, leading to the inhibition of cell survival, clonogenicity, pancreatosphere formation capacity, cell migration, and CSC function in human pancreatic cancer cells (129). In addition, curcumin analogues EF31 and UBS109 could also inhibit HSP-90 and NF-κB, leading to the down-regulation of DNMT-1 expression in pancreatic cancer cells (147). These findings suggest the beneficial effects of curcumin and its analogs in the inhibition of pancreatic cancer though the epigenetic deregulation of several important genes.

It has been found that EGCG could decrease global DNA methylation in cancer cells. EGCG could induce the expression of Raf kinase inhibitor protein (RKIP) through the inhibition of HDAC activity, suggesting the effects of EGCG on epigenetic regulation (148). Moreover, the epigenetic regulation by EGCG up-regulates the expression of histone H3 and down-regulates the expression of Snail, nuclear translocation of NF-κB, the activity of MMP-2 and -9, and the invasive activity of AsPC-1 pancreatic cancer cells (148). In addition, increased expression of E-cadherin and decreased phosphorylation of ERK were also observed upon EGCG treatment (148). These results demonstrate that EGCG could function as an epigenetic regulator to modulate signal transduction in the PKIP/ERK/NF-κB signaling pathway, leading to the inhibition of the invasion of pancreatic cancer cells.

Recent studies have shown that garcinol possesses anti-cancer activity through its antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic, and proapoptotic activities. Moreover, garcinol could also function as an effective epigenetic regulator by inhibiting histone acetyltransferases and modulating miRNAs that are involved in carcinogenesis, leading to the growth inhibition of pancreatic cancer in vitro and in vivo (149). Therefore, garcinol could be a promising nutraceutical for the prevention and/or treatment of pancreatic cancer which is in part due to epigenetic regulation.

Because the nutraceuticals including metformin, genistein, curcumin, etc. have shown their anti-cancer activities through the regulation of cellular signaling, miRNAs, and epigenome in vitro, these nutraceuticals have been used in the clinical trials for the prevention or combination treatment of pancreatic cancers (34,150). Metformin is being used with the conventional chemotherapeutics such as gemcitabine, erlotinib, capecitabine, cisplatin, epirubicin, and others in the clinical trials for the combination treatment of pancreatic cancer (ClinicalTrials.gov). Curcumin has also been used in combination with gemcitabine and Celebrex in the clinical trials for pancreatic cancer therapy. Similarly, several clinical trials are being conducted to evaluate the role of genistein and AXP107-11, a crystalline form of genistein, in the combination treatment of pancreatic cancer with gemcitabine and erlotinib (ClinicalTrials.gov). In addition, vitamins have also been used in combination with chemotherapeutics in pancreatic cancer clinical trials. Table 2 lists ongoing clinical trials using nutrients and nutraceuticals in combination with conventional chemotherapeutics for achieving better treatment outcome of patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. The results from these clinical trials will reveal the true value of these nutraceuticals in the treatment of pancreatic cancer.

Table 2.

Ongoing clinical trials using nutrients and nutraceuticals in the combination treatment of pancreatic cancer. (ClinicalTrials.gov)

| NCT Number | Title | Phases |

|---|---|---|

| NCT01210911 | Metformin Combined With Chemotherapy for Pancreatic Cancer | Phase II |

| NCT01954732 | Metformin Hydrochloride in Treating Patients With Pancreatic Cancer That Can be Removed by Surgery | Phase II |

| NCT01167738 | Combination Chemotherapy With or Without Metformin in Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer | Phase II |

| NCT02005419 | Metformin Combined With Gemcitabine as Adjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer After Curative Resection | Phase II |

| NCT01666730 | Metformin Plus Modified FOLFOX 6 in Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer | Phase II |

| NCT01488552 | Gemcitabine+Paclitaxel and FOLFIRINOX and Profiling for Patients With Advanced Pancreatic Cancer | Phase I/II |

| NCT01971034 | Treatment of Patients With Advanced Pancreatic Cancer After Gemcitabine Failure. | Phase II |

| NCT02048384 | Metformin With or Without Rapamycin as Maintenance Therapy in Subjects With Pancreatic Cancer | Phase 1/II |

| NCT00094445 | Trial of Curcumin in Advanced Pancreatic Cancer | Phase II |

| NCT00192842 | Gemcitabine With Curcumin for Pancreatic Cancer | Phase II |

| NCT00486460 | Gemcitabine, Curcumin and Celebrex in Patients With Advance or Inoperable Pancreatic Cancer | Phase III |

| NCT00882765 | Genistein in Treating Patients With Pancreatic Cancer That Can Be Removed by Surgery | Phase II |

| NCT00376948 | Genistein, Gemcitabine, and Erlotinib in Patients With Locally Advanced or Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer | Phase II |

| NCT01182246 | AXP107-11 in Combination With Standard Gemcitabine Therapy for Patients With Pancreatic Cancer | Phase I/II |

| NCT01879878 | Pilot Study Evaluating Broccoli Sprouts in Advanced Pancreatic Cancer | |

| NCT01905150 | Vitamin C & G-FLIP (Low Doses Gemcitabine, 5FU, Leucovorin, Irinotecan, Oxaliplatin) for Pancreatic Cancer | Phase II |

| NCT01515046 | Clinical Trial of High-dose Vitamin C for Advanced Pancreatic Cancer | Phase II |

| NCT01364805 | New Treatment Option for Pancreatic Cancer | Phase I |

| NCT01555489 | The Efficacy and Safety of IV Vitamin C in Combination With Standard Chemotherapy for Pancreatic Ca | Phase II |

| NCT00954525 | Intravenous Vitamin C in Combination With Standard Chemotherapy for Pancreatic Cancer | Phase I |

| NCT00985777 | Vitamin E Tocotrienol Administered to Subjects With Resectable Pancreatic Exocrine Neoplasia | Phase I |

| NCT01327794 | Vitamin D Biomarkers and Survival in Blood Samples From Patients With Advanced Pancreatic Cancer | |

| NCT01049880 | A Research Trial of High Dose Vitamin C and Chemotherapy for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer | Phase I |

| NCT02030860 | Neoadjuvant Paricalcitol to Target the Microenvironment in Resectable Pancreatic Cancer | |

| NCT00342992 | Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention (ATBC) Study | |

| NCT02080221 | FOLFOX-A For Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: A Phase II Brown University Oncology Research Group Trial | Phase II |

| NCT01063192 | A Study of Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer | Phase II |

| NCT00149578 | A Phase II Study of Combine Modality Therapy in Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer | Phase II |

| NCT01836432 | Immunotherapy Study in Borderline Resectable or Locally Advanced Unresectable Pancreatic Cancer | Phase III |

| NCT00089024 | Combination Chemotherapy, and Radiation Therapy in Patients With Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer | Phase II |

| NCT00323583 | Weekly Dosing of an Integrative Chemotherapy Combination to Treat Advanced Pancreatic Cancer | Phase II |

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Epidemiological studies have shown the beneficial effects of some nutrients in foods on the inhibition of pancreatic carcinogenesis. Moreover, experimental studies have demonstrated that nutraceuticals inhibit the development and progression of pancreatic cancer through the regulation of several important cellular signaling pathways such as EGFR, COX-2, Akt, NF-κB, etc, which are aberrantly activated in pancreatic cancer. Importantly, nutraceuticals also up-regulate the expression of tumor suppressive miRNAs such as let-7 and miR-200 families, and down-regulate the expression of oncogenic miRNAs such as miR-21 and miR-221, leading to the inhibition of pancreatic cancer cell growth and pancreatic CSC self-renewal capacity through deregulation of cellular signaling networks. Furthermore, nutraceuticals also regulate epigenetic events through deregulation of coding genes and miRNAs, leading to the normalization of altered cellular signaling in pancreatic cancer cells. Therefore, nutraceuticals could become promising agents for the prevention of pancreatic cancer. More importantly, nutraceuticals could be useful as adjuncts to conventional therapy for achieving better treatment outcomes in patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. However, more in vitro mechanistic experiments, in vivo animal studies, and innovative clinical trials are warranted to fulfill the promise regarding the beneficial effects of nutraceuticals for the prevention and/or treatment of pancreatic cancer.

It is also important to note that pancreatic stellate cells and the microenvironment of pancreatic cancer have received much attention in the area of pancreatic cancer research in recent years. The tumor microenvironment could influence the drug sensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells while pancreatic stellate cells could stimulate pancreatic cancer cell invasion, metastasis, and resistance to conventional chemotherapy. The pancreatic stellate cells and tumor microenvironment in pancreatic cancer could be altered by miRNAs and epigenetic regulation. Therefore, further investigation to dissect the molecular effects of nutraceuticals on the miRNAs, and thus epigenetically regulated pancreatic stellate cell function and tumor microenvironment could open a new avenue towards the development of better treatment strategies for pancreatic cancer with nutraceuticals and chemotherapeutics using novel rational design and targeted therapies.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ work cited in this review article was partly funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute, NIH (5R01CA108535, 5R01CA131151, 5R01CA132794, 5R01CA154321, and 1R01CA164318 awarded to FHS and 1P01AT00396001A1 and 1P01 CA16320001 awarded to VLW Go). We also thank Puschelberg and Guido foundations for their generous financial contribution.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Yiwei Li, Departments of Pathology, Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI, USA.

Vay Liang W. Go, Division of Digestive Diseases, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Fazlul H. Sarkar, Departments of Pathology and Oncology, Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI, USA.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pool-Zobel BL, Adlercreutz H, Glei M, et al. Isoflavonoids and lignans have different potentials to modulate oxidative genetic damage in human colon cells. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1247–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Astley SB, Elliott RM, Archer DB, et al. Increased cellular carotenoid levels reduce the persistence of DNA single-strand breaks after oxidative challenge. Nutr Cancer. 2002;43:202–213. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC432_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Martinis BS, Bianchi MD. Effect of vitamin C supplementation against cisplatin-induced toxicity and oxidative DNA damage in rats. Pharmacol Res. 2001;44:317–320. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2001.0860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appel MJ, Roverts G, Woutersen RA. Inhibitory effects of micronutrients on pancreatic carcinogenesis in azaserine-treated rats. Carcinogenesis. 1991;12:2157–2161. doi: 10.1093/carcin/12.11.2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jansen RJ, Robinson DP, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, et al. Nutrients from fruit and vegetable consumption reduce the risk of pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2013;44:152–161. doi: 10.1007/s12029-012-9441-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han X, Li J, Brasky TM, et al. Antioxidant intake and pancreatic cancer risk: the Vitamins and Lifestyle (VITAL) Study. Cancer. 2013;119:1314–1320. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bravi F, Polesel J, Bosetti C, et al. Dietary intake of selected micronutrients and the risk of pancreatic cancer: an Italian case-control study. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:202–206. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong X, Li Y, Chang P, et al. Glucose metabolism gene variants modulate the risk of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:758–766. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ben Q, Xu M, Ning X, et al. Diabetes mellitus and risk of pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1928–1937. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y, Kong D, Bao B, et al. Induction of cancer cell death by isoflavone: the role of multiple signaling pathways. Nutrients. 2011;3:877–896. doi: 10.3390/nu3100877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kole L, Giri B, Manna SK, et al. Biochanin-A, an isoflavon, showed anti-proliferative and anti-inflammatory activities through the inhibition of iNOS expression, p38-MAPK and ATF-2 phosphorylation and blocking NFkappaB nuclear translocation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;653:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park W, Amin AR, Chen ZG, et al. New perspectives of curcumin in cancer prevention. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2013;6:387–400. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan N, Afaq F, Saleem M, et al. Targeting multiple signaling pathways by green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2500–2505. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banerjee S, Kong D, Wang Z, et al. Attenuation of multi-targeted proliferation-linked signaling by 3,3′-diindolylmethane (DIM): from bench to clinic. Mutat Res. 2011;728:47–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hecht SS. Chemoprevention of cancer by isothiocyanates, modifiers of carcinogen metabolism. J Nutr. 1999;129:768S–774S. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.3.768S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheung KL, Kong AN. Molecular targets of dietary phenethyl isothiocyanate and sulforaphane for cancer chemoprevention. AAPS J. 2010;12:87–97. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9162-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitlock NC, Baek SJ. The anticancer effects of resveratrol: modulation of transcription factors. Nutr Cancer. 2012;64:493–502. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2012.667862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharoni Y, Linnewiel-Hermoni K, Zango G, et al. The role of lycopene and its derivatives in the regulation of transcription systems: implications for cancer prevention. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:1173S–1178S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.034645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balasubramanyam K, Altaf M, Varier RA, et al. Polyisoprenylated benzophenone, garcinol, a natural histone acetyltransferase inhibitor, represses chromatin transcription and alters global gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33716–33726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402839200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shukla S, Gupta S. Apigenin: a promising molecule for cancer prevention. Pharm Res. 2010;27:962–978. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0089-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saif MW, Tytler E, Lansigan F, et al. Flavonoids, phenoxodiol, and a novel agent, triphendiol, for the treatment of pancreaticobiliary cancers. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:469–479. doi: 10.1517/13543780902762835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham GG, Punt J, Arora M, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of metformin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011;50:81–98. doi: 10.2165/11534750-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woo CC, Kumar AP, Sethi G, et al. Thymoquinone: potential cure for inflammatory disorders and cancer. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:443–451. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei WT, Lin SZ, Liu DL, et al. The distinct mechanisms of the antitumor activity of emodin in different types of cancer (Review) Oncol Rep. 2013;30:2555–2562. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Padhye S, Dandawate P, Yusufi M, et al. Perspectives on medicinal properties of plumbagin and its analogs. Med Res Rev. 2012;32:1131–1158. doi: 10.1002/med.20235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nkondjock A, Ghadirian P, Johnson KC, et al. Dietary intake of lycopene is associated with reduced pancreatic cancer risk. J Nutr. 2005;135:592–597. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.3.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Comstock GW, Helzlsouer KJ, Bush TL. Prediagnostic serum levels of carotenoids and vitamin E as related to subsequent cancer in Washington County, Maryland. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53:260S–264S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/53.1.260S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heinen MM, Verhage BA, Goldbohm RA, et al. Intake of vegetables, fruits, carotenoids and vitamins C and E and pancreatic cancer risk in The Netherlands Cohort Study. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:147–158. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schernhammer E, Wolpin B, Rifai N, et al. Plasma folate, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, and homocysteine and pancreatic cancer risk in four large cohorts. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5553–5560. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang CS, Wang H, Hu B. Combination of chemopreventive agents in nanoparticles for cancer prevention. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2013;6:1011–1014. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Graubard BI, Chari S, et al. Insulin, glucose, insulin resistance, and pancreatic cancer in male smokers. JAMA. 2005;294:2872–2878. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.22.2872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pollak M. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor signalling in neoplasia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:915–928. doi: 10.1038/nrc2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rozengurt E, Sinnett-Smith J, Kisfalvi K. Crosstalk between insulin/insulin-like growth factor-1 receptors and G protein-coupled receptor signaling systems: a novel target for the antidiabetic drug metformin in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2505–2511. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li D, Yeung SC, Hassan MM, et al. Antidiabetic therapies affect risk of pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:482–488. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Go VL, Butrum RR, Wong DA. Diet, nutrition, and cancer prevention: the postgenomic era. J Nutr. 2003;133:3830S–3836S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3830S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Go VL, Wong DA, Wang Y, et al. Diet and cancer prevention: evidence-based medicine to genomic medicine. J Nutr. 2004;134:3513S–3516S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.12.3513S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Go VL, Nguyen CT, Harris DM, et al. Nutrient-gene interaction: metabolic genotype-phenotype relationship. J Nutr. 2005;135:3016S–3020S. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.12.3016S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blanchard RK, Moore JB, Green CL, et al. Modulation of intestinal gene expression by dietary zinc status: effectiveness of cDNA arrays for expression profiling of a single nutrient deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13507–13513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251532498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chaudhary N, Nakka KK, Maulik N, et al. Epigenetic manifestation of metabolic syndrome and dietary management. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17:254–281. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lunec J, Halligan E, Mistry N, et al. Effect of vitamin E on gene expression changes in diet-related carcinogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1031:169–183. doi: 10.1196/annals.1331.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y, Sarkar FH. Gene expression profiles of genistein-treated PC3 prostate cancer cells. J Nutr. 2002;132:3623–3631. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.12.3623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Talar-Wojnarowska R, Malecka-Panas E. Molecular pathogenesis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: potential clinical implications. Med Sci Monit. 2006;12:RA186–RA193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bai J, Sata N, Nagai H, et al. Genistein-induced changes in gene expression in Panc 1 cells at physiological concentrations of genistein. Pancreas. 2004;29:93–98. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200408000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hafeez BB, Jamal MS, Fischer JW, et al. Plumbagin, a plant derived natural agent inhibits the growth of pancreatic cancer cells in in vitro and in vivo via targeting EGFR, Stat3 and NF-kappaB signaling pathways. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2175–2186. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.El-Rayes BF, Ali S, Ali IF, et al. Potentiation of the effect of erlotinib by genistein in pancreatic cancer: the role of Akt and nuclear factor-kappaB. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10553–10559. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ali S, Banerjee S, Ahmad A, et al. Apoptosis-inducing effect of erlotinib is potentiated by 3,3′-diindolylmethane in vitro and in vivo using an orthotopic model of pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1708–1719. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 48.Molina MA, Sitja-Arnau M, Lemoine MG, et al. Increased cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human pancreatic carcinomas and cell lines: growth inhibition by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4356–4362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okami J, Yamamoto H, Fujiwara Y, et al. Overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 in carcinoma of the pancreas. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2018–2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lev-Ari S, Starr A, Vexler A, et al. Inhibition of pancreatic and lung adenocarcinoma cell survival by curcumin is associated with increased apoptosis, down-regulation of COX-2 and EGFR and inhibition of Erk1/2 activity. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:4423–4430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bengmark S. Curcumin, an atoxic antioxidant and natural NFkappaB, cyclooxygenase-2, lipooxygenase, and inducible nitric oxide synthase inhibitor: a shield against acute and chronic diseases. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2006;30:45–51. doi: 10.1177/014860710603000145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lev-Ari S, Zinger H, Kazanov D, et al. Curcumin synergistically potentiates the growth inhibitory and pro-apoptotic effects of celecoxib in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2005;59 (Suppl 2):S276–S280. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(05)80045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lev-Ari S, Vexler A, Starr A, et al. Curcumin augments gemcitabine cytotoxic effect on pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell lines. Cancer Invest. 2007;25:411–418. doi: 10.1080/07357900701359577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Padhye S, Banerjee S, Chavan D, et al. Fluorocurcumins as cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor: molecular docking, pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution in mice. Pharm Res. 2009;26:2438–2445. doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-9955-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bao B, Ali S, Kong D, et al. Anti-tumor activity of a novel compound-CDF is mediated by regulating miR-21, miR-200, and PTEN in pancreatic cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 56.Harikumar KB, Kunnumakkara AB, Sethi G, et al. Resveratrol, a multitargeted agent, can enhance antitumor activity of gemcitabine in vitro and in orthotopic mouse model of human pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:257–268. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ma JX, Sun YL, Wang YQ, et al. Triptolide induces apoptosis and inhibits the growth and angiogenesis of human pancreatic cancer cells by downregulating COX-2 and VEGF. Oncol Res. 2013;20:359–368. doi: 10.3727/096504013X13657689382932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu W, Li J, Wu S, et al. Triptolide cooperates with Cisplatin to induce apoptosis in gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2012;41:1029–1038. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31824abdc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Downward J. PI 3-kinase, Akt and cell survival. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2004;15:177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu S, Wang XJ, Liu Y, et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling is involved in (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-induced apoptosis of human pancreatic carcinoma cells. Am J Chin Med. 2013;41:629–642. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X13500444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roy SK, Chen Q, Fu J, et al. Resveratrol inhibits growth of orthotopic pancreatic tumors through activation of FOXO transcription factors. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li W, Ma J, Ma Q, et al. Resveratrol inhibits the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of pancreatic cancer cells via suppression of the PI-3K/Akt/NF-kappaB pathway. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20:4185–4194. doi: 10.2174/09298673113209990251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boreddy SR, Pramanik KC, Srivastava SK. Pancreatic tumor suppression by benzyl isothiocyanate is associated with inhibition of PI3K/AKT/FOXO pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1784–1795. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roy SK, Srivastava RK, Shankar S. Inhibition of PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK pathways causes activation of FOXO transcription factor, leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in pancreatic cancer. J Mol Signal. 2010;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bhardwaj V, Tadinada SM, Jain A, et al. Biochanin A reduces pancreatic cancer survival and progression. Anticancer Drugs. 2014;25:296–302. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ali S, Ahmad A, Banerjee S, et al. Gemcitabine sensitivity can be induced in pancreatic cancer cells through modulation of miR-200 and miR-21 expression by curcumin or its analogue CDF. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3606–3617. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 67.Friedman L, Lin L, Ball S, et al. Curcumin analogues exhibit enhanced growth suppressive activity in human pancreatic cancer cells. Anticancer Drugs. 2009;20:444–449. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32832afc04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hatcher H, Planalp R, Cho J, et al. Curcumin: from ancient medicine to current clinical trials. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1631–1652. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7452-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Banerjee S, Zhang Y, Ali S, et al. Molecular evidence for increased antitumor activity of gemcitabine by genistein in vitro and in vivo using an orthotopic model of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9064–9072. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Strouch MJ, Milam BM, Melstrom LG, et al. The flavonoid apigenin potentiates the growth inhibitory effects of gemcitabine and abrogates gemcitabine resistance in human pancreatic cancer cells. Pancreas. 2009;38:409–415. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318193a074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee SH, Ryu JK, Lee KY, et al. Enhanced anti-tumor effect of combination therapy with gemcitabine and apigenin in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2008;259:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Melstrom LG, Salabat MR, Ding XZ, et al. Apigenin inhibits the GLUT-1 glucose transporter and the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway in human pancreatic cancer cells. Pancreas. 2008;37:426–431. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181735ccb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wei WT, Chen H, Ni ZL, et al. Antitumor and apoptosis-promoting properties of emodin, an anthraquinone derivative from Rheum officinale Baill, against pancreatic cancer in mice via inhibition of Akt activation. Int J Oncol. 2011;39:1381–1390. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer development and progression. Nature. 2006;441:431–436. doi: 10.1038/nature04870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang W, Abbruzzese JL, Evans DB, et al. The nuclear factor-kappa B RelA transcription factor is constitutively activated in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:119–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Batra S, Sahu RP, Kandala PK, et al. Benzyl isothiocyanate-mediated inhibition of histone deacetylase leads to NF-kappaB turnoff in human pancreatic carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1596–1608. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Srivastava SK, Singh SV. Cell cycle arrest, apoptosis induction and inhibition of nuclear factor kappa B activation in anti-proliferative activity of benzyl isothiocyanate against human pancreatic cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:1701–1709. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rausch V, Liu L, Kallifatidis G, et al. Synergistic activity of sorafenib and sulforaphane abolishes pancreatic cancer stem cell characteristics. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5004–5013. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu L, Salnikov AV, Bauer N, et al. Triptolide reverses hypoxia-induced EMT and stem-like features in pancreatic cancer by NF-kappaB downregulation. Int J Cancer. 2013 doi: 10.1002/ijc.28583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chehl N, Chipitsyna G, Gong Q, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of the Nigella sativa seed extract, thymoquinone, in pancreatic cancer cells. HPB (Oxford) 2009;11:373–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00059.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ahmad A, Wang Z, Wojewoda C, et al. Garcinol-induced apoptosis in prostate and pancreatic cancer cells is mediated by NF-kappaB signaling. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2011;3:1483–1492. doi: 10.2741/e349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Parasramka MA, Gupta SV. Garcinol inhibits cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63:456–465. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.535962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li Y, Ellis KL, Ali S, et al. Apoptosis-inducing effect of chemotherapeutic agents is potentiated by soy isoflavone genistein, a natural inhibitor of NF-kappaB in BxPC-3 pancreatic cancer cell line. Pancreas. 2004;28:e90–e95. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200405000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li Y, Ahmed F, Ali S, et al. Inactivation of nuclear factor kappaB by soy isoflavone genistein contributes to increased apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic agents in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6934–6942. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mohammad RM, Banerjee S, Li Y, et al. Cisplatin-induced antitumor activity is potentiated by the soy isoflavone genistein in BxPC-3 pancreatic tumor xenografts. Cancer. 2006;106:1260–1268. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Muerkoster S, Arlt A, Witt M, et al. Usage of the NF-kappaB inhibitor sulfasalazine as sensitizing agent in combined chemotherapy of pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 2003;104:469–476. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]