Abstract

We assessed what impact can be expected from global health treaties on the basis of 90 quantitative evaluations of existing treaties on trade, finance, human rights, conflict, and the environment.

It appears treaties consistently succeed in shaping economic matters and consistently fail in achieving social progress. There are at least 3 differences between these domains that point to design characteristics that new global health treaties can incorporate to achieve positive impact: (1) incentives for those with power to act on them; (2) institutions designed to bring edicts into effect; and (3) interests advocating their negotiation, adoption, ratification, and domestic implementation.

Experimental and quasiexperimental evaluations of treaties would provide more information about what can be expected from this type of global intervention.

There have been many calls over the past few years for new international treaties addressing health issues, including alcohol,1 chronic diseases,2 falsified/substandard medicines,3 health system corruption,4 impact evaluations,5 nutrition,6 obesity,7 research and development,8 and global health broadly.9 These calls follow the perceived success of past global health treaties—most notably the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (2002) and the revised International Health Regulations (2005)—and perceived potential for future impact.10 The World Health Organization’s unusually expansive yet largely dormant powers for making new international treaties under its constitution’s articles 19 and 21 are also cited as a reason for using them.11–13 Although few multilateral institutions are empowered to enact new treaties, in the World Health Organization’s case, with just a majority vote of its governing assembly, new regulations can automatically enter into force for all member states on communicable disease control, medical nomenclature, diagnostic standards, health product safety, labeling, and advertising unless states specifically opt out (article 21). Treaties in other health areas can be adopted by a two thirds vote of the World Health Organization’s membership, with nonaccepting states legally required to take the unusual step of justifying their nonacceptance (article 19).14

The effect that can be expected from any new global health treaty, however, is as yet largely unknown. Negotiation, adoption, ratification, and even domestic implementation of treaties do not guarantee achievement of the results that are sought. Contemporary history has shown how some states comply with international treaties whereas others neglect their responsibilities. Even those states that mostly comply with their international legal obligations do not necessarily comply with all of them. Citizens in the most prosperous and powerful countries may be surprised by the extent to which their own governments break international law and skirt responsibilities—which is well beyond what may be commonly assumed. Often states are even quite open about acknowledging their noncompliance, whether in statements to the media or in formal reports to international institutions.15 Perhaps most concerning is that even if we assume all international treaties cause at least some effects, there is no reason to believe these effects will all be intended and desirable. States can strategically use international treaty making to buy time before needing to act, placate domestic constituencies without changing domestic policies, provide a distraction from dissatisfaction, hide more pressing challenges, and justify unsavory expenditures. Ratifying international treaties can even provide political cover for engaging in behaviors—such as state-sponsored torture—that are more harmful than what was done or may have been acceptable before.15,16 In this way, advocates of new global health treaties cannot be sure whether they are successfully promoting their goals or unintentionally helping states undermine the very objectives they so earnestly seek to be fulfilled.

The most obvious starting point to assess what impact can be expected from global health treaties would be evaluations of existing global health treaties—those that were adopted primarily to promote human health. These include the International Sanitary Conventions (1892, 1893, 1894, 1897, 1903, 1912, 1926, 1938, 1944, 1944, 1946), Brussels Agreement for Free Treatment of Venereal Disease in Merchant Seamen (1924), International Convention for Mutual Protection Against Dengue Fever (1934), International Sanitary Convention for Aerial Navigation (1933, 1944), Constitution of the World Health Organization (1946), International Sanitary Regulations (1951), International Health Regulations (1969), Biological Weapons Convention (1972), Basel Convention on Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal (1989), Chemical Weapons Convention (1993), World Trade Organization Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (1994), Convention on the Prohibition of Anti-Personnel Mines and Their Destruction (1997), Rotterdam Convention on Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade (1998), Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety to the Convention on Biological Diversity (2000), Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (2001), World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (2003), International Health Regulations (2005), and Minamata Convention on Mercury (2013).

However, few studies to date have empirically measured the real-world effect of these global health treaties across countries.17–19 Three studies modeled the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control’s influence on national policies, finding that the treaty and its negotiation process were associated with certain countries adopting stronger tobacco control measures faster.20–22 Although it is not a treaty, there is a study that qualitatively evaluated the perceived effectiveness of the World Health Organization’s Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel, finding it had no effect on 93% of key informants surveyed.23

The evidence of international treaties’ effects in other policy areas is rapidly expanding and can be used to inform judgments about what impact can be expected from existing and proposed global health treaties. The precise effects of international treaties, their causal pathways, and the conditions under which these pathways function is currently among the most heavily debated issues and contested puzzles in the fields of international law and international relations.17,18 This includes at least 90 quantitative studies evaluating the effect of international trade treaties,24–32 international financial treaties,33–67 international human rights treaties,68–98 international humanitarian treaties,99–105 and international environmental treaties.106–115

ASSESSING IMPACT BY POLICY AREA

As with any complex regulatory intervention, the effect of international treaties will vary greatly depending on the problems being addressed and the contexts in which they operate.18 Looking at their impact by policy area is particularly important for drawing insights about global health treaties because the latter are so diverse, with some proposals most reminiscent of international human rights treaties that promote norms (e.g., proposed health research and development treaty), international humanitarian treaties that constrain state behavior (e.g., proposed global health corruption protocol), international environmental treaties that impose regulatory obligations (e.g., proposed framework convention on alcohol control), and international trade treaties that regulate cross-border interactions (e.g., proposed falsified/substandard medicines treaty).

Evaluations of international trade treaties have overwhelmingly found they encourage liberal trade policies and increase trade flows among participating states as intended. International financial treaties have similarly been found to reduce financial transaction restrictions and increase financial flows. Less evident is the impact of human rights treaties. These treaties have been found to improve respect for civil and political rights but only in countries with particular domestic institutions such as democracy,71 civil society,116,117 and judicial independence.118 International criminal treaties appear even more contested and uncertain. Some scholars have found war crime prosecutions to have no effect on violations119—some even claim it can worsen matters by lowering losing parties’ incentives to make peace120—whereas others have found it improves postconflict reconstruction efforts by facilitating transitional justice.85 International environmental treaties’ effects are similarly debated. Some argue they can improve environmental protection,106 especially by incentivizing private sector action,121 and others contend they merely codify existing practices, preferring incremental approaches that use nontreaty political mechanisms.122

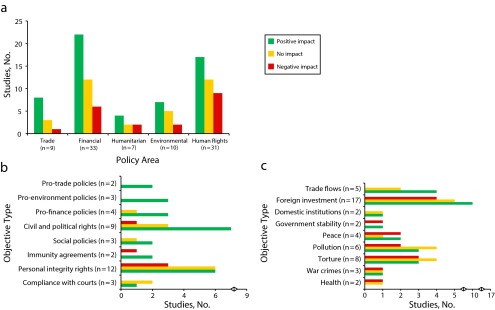

When categorizing each of the 90 quantitative evaluations according to whether they found positive, negative, or no effects—defined on the basis of the treaties’ own stated purposes as found in the preamble text—it appears that trade and finance is where international treaties have been most “successful” (Figure 1a). The 9 studies evaluating international trade treaties overall found them to reduce trade volatility and increase trade flows,31 particularly among member states of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the World Trade Organization28 but also among nonmember participants.29 Preferential trade agreements conditional on human rights standards were associated with less repression than were preferential trade agreements without them.27 However, some studies suggest that international trade treaties do not guarantee increased trade flows25 and that any increases may be limited to industrialized states and liberalized economic sectors.26,28 The 33 studies evaluating international financial treaties mostly found they increase foreign investment among participating states,33–37,40,41,43,44,46–48,50,53,56,57,59,60,62–67 although some found they had no impact in certain circumstances,38,39,42,45,49,51,52,55,57,59,61,62 and others concluded they sometimes diminished investment (Table 1).49,50,54,55,58,65

FIGURE 1—

Number of studies showing positive, negative, and no impact on (a) any outcome measure by policy area, (b) government policies by type of objective, and (c) people, places, and products by type of objective.

Note. Outcomes were deemed either “positive” or “negative” on the basis of whether they aligned or contradicted treaties’ own stated goals as found in their preamble text. We coded studies that drew both positive and negative conclusions twice in the bar chart coloring but only once in the tally of studies presented beside each label. This explains why there are 2 studies evaluating the impact of international law on immunity agreements for international crimes although the bar chart coloring indicates that 66% of studies found a positive impact and 33% found a negative impact. This also explains why there are 4 studies evaluating the impact of international law on peace yet the bar chart coloring indicates that 2 studies found a positive impact, 2 found a negative impact, and 1 found no impact. The figure does not show the impact of international laws on derogation from rights, economic sanctions, public support, and water levels because these 4 outcome measures were only evaluated in a single study each.

TABLE 1—

Impact of Different Areas of Laws on Any Outcome Measure

| Area of Law | Negative Impact | No Impact | Positive Impact |

| International human rights law (n = 31) | 69 | 68 | 71 |

| 70 | 73,a | 73,a | |

| 72 | 74 | 78 | |

| 81,b | 75 | 79 | |

| 84,a | 76,b | 80 | |

| 86,a | 77 | 82 | |

| 87 | 83,b | 84,a | |

| 92,a | 91 | 85 | |

| 97,a | 93,a | 86,a | |

| 95,a | 88 | ||

| 96,a | 89 | ||

| 97,a | 90,b | ||

| 92,a | |||

| 93,a | |||

| 95,a | |||

| 96,a | |||

| 98,b | |||

| 94 | |||

| International humanitarian law (n = 7) | 100 | 99,b | 102,b |

| 104,a,b | 101 | 103 | |

| 105,b | |||

| 104,a,b | |||

| International environmental law (n = 10) | 106,a,b | 107 | 106,a,b |

| 108,a | 109,a,b | 108,a | |

| 111,b | 109,a,b | ||

| 112 | 110,b | ||

| 114,a,b | 113,b | ||

| 114,a,b | |||

| 115,b | |||

| International trade law (n = 9) | 32,a | 25 | 24 |

| 26,a | 26,a | ||

| 27,a | 27,a | ||

| 28 | |||

| 29 | |||

| 30 | |||

| 31 | |||

| 32,a | |||

| International financial law (n = 33) | 49,a | 38 | 33,b |

| 50,a,b | 39 | 34–36 | |

| 54 | 42 | 37 | |

| 55,a | 45 | 40 | |

| 58,b | 49,a | 41 | |

| 65,a | 51 | 43 | |

| 52 | 44 | ||

| 55,a | 46 | ||

| 57,a | 47,b | ||

| 59,a | 48 | ||

| 61,b | 50,a,b | ||

| 62,a | 53 | ||

| 56 | |||

| 57,a | |||

| 59,a | |||

| 60 | |||

| 62,a | |||

| 63 | |||

| 64 | |||

| 65,a | |||

| 66 | |||

| 67 | |||

| No. of studies | 20 | 34 | 59 |

Note. Except where indicated, numbers in each column refer to reference citations in this paper. The citations are listed in chronological order.

These 23 studies are listed more than once, as they featured multiple conclusions about the impact of international law on measured outcomes.

These 23 studies used time-series analysis (n = 3),33,99,114 cross-sectional analysis (n = 6),33,61,76,90,102,111 Cox proportionate hazard models (n = 4),34–36,80,104,105 generalized method of moments analysis (n = 1),47 quantile treatment effect distributional analysis (n = 1),50 formal model analysis (n = 1),109 descriptive statistics (n = 6),81,83,106,110,113,115 survey experiments (n = 1),98 and difference-in-difference analysis (n = 1).58 One of these studies used both time-series analysis and cross-sectional analysis.33 The other 67 studies24–32,37–46,48,49,51–57,59,60,62–75,77–79,82,84–89,91–97,100,101,103,107,108,112 and 2 of the studies with Cox proportionate hazard modeling34–36,80 used time-series cross-sectional analysis.

ASSESSING IMPACT BY TYPE OF OBJECTIVE

The effect of international treaties will also vary according to the type of objective sought. This insight is important for global health treaties because each proposal has different goals, from changing national government policies to regulating people, places, or products.

The good news is that most studies evaluating changes in national government policies found treaties had a positive effect in the direction drafters desired (Figure 1b). For example, World Trade Organization and General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade membership increased trade liberalization24,30 just as the International Monetary Fund’s Articles of Agreement successfully reduced restrictions on financial transactions.34–36,46,60 International environmental treaties promoted desired changes in national environmental policies,110,113,115 International Labor Organization conventions increased the length of maternity leave,89 and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court has succeeded in preventing immunity agreements for international crimes by state parties.102,104

The bad news is that treaties’ influence on government policies did not always translate into positive changes for people, places, or products—with “positive” defined on the basis of treaties’ own stated goals in their preamble text (Figure 1c). Most studies that evaluated real-world outcomes found treaties had either no effect or the opposite effect than what was intended. For example, environmental agreements did not always reduce pollution,106–112 international humanitarian treaties did not reduce intentional civilian fatalities during wartime,101 human rights treaties did not improve life expectancy or infant mortality,76 and structural adjustment agreements actually diminished these health indicators along with basic literacy rates and government stability.72 Eight studies are split on whether the Convention Against Torture improved, had no effect, or worsened torture practices.69,75,77,84,87,89,93,96

Like the earlier analysis by policy area, a common trend here is that international treaties seem to be most successful in attaining economic objectives. This analysis additionally emphasizes how treaties seem to be least successful in realizing social goals. Although nearly all studies that evaluated these outcomes found treaties increased liberal economic policies, trade flows, and foreign investment, few studies reported improvements in government stability, peace, pollution, torture, war crimes, or health. More studies concluded that treaties had negative effects in these noneconomic areas than either positive or no effects (Table 2; individual summaries of the 90 quantitative evaluations are available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

TABLE 2—

Impact of International Treaties, by Impact Area

| Outcome | Study Conclusions | Impact | Conditions |

| Impact on government policies | |||

| Civil and political rights (n = 12) | Keith found ratifying the ICCPR did not improve civil rights practices.68 | None | |

| Hathaway found ratifying the ICCPR did not improve civil liberties and did not increase fairness of trials, and ratifying the UN Covenant on the Political Rights of Women did not improve women’s ability to take part in government.69 | None | ||

| Neumayer found ratifying human rights treaties improved civil rights practices in democratic states or states with strong engagement in global civil society.71 | Positive | Democracy Civil society | |

| Abouharb and Cingraelli found SAAs promoted an institutionalized democracy, freedom of assembly and association, freedom of speech, and free and fair elections.72 | Positive | ||

| Cardenas found international and domestic human rights pressures did not improve civil rights practices but increased ratification of human rights treaties in countries without a national security threat, in which norm violations would threaten the elites’ economic interests and prohuman rights groups have public support.73 | None and positive | Security Elite interests Human rights groups | |

| Simmons found ratifying the ICCPR slightly improved civil liberties after 5 years, reduced government restrictions on religious freedoms most strongly in states transitioning between autocracy and democracy, and improved the fairness of trials only in countries transitioning between autocracy and democracy.78 | Positive | Transitional state | |

| Simmons found ratifying 6 international human rights treaties (e.g., ICCPR, ICESCR, CERD, CEDAW, CAT, and CRC) improved civil and political rights practices in states transitioning between autocracy and democracy.79 | Positive | Transitional state | |

| Simmons found ratifying the ICCPR’s optional protocol slightly improved civil liberties.80 | Positive | ||

| Hill found ratifying the CEDAW improved women’s political rights practices.84 | Positive | ||

| Cole found due process and personal liberty claims filed under the ICCPR’s Optional Protocol were more successful than were suffrage and family rights claims in HRC rulings.86 | Both | Claim type | |

| Lupu found ratifying the ICCPR improved government respect for freedoms of speech, association, assembly, and religion.95 | Positive | ||

| Lupu found ratifying CEDAW improved respect for women’s political rights.96 | Positive | ||

| Compliance with court rulings (n = 3) | Basch et al. found high noncompliance with remedies adopted by the IASHPR, with total compliance observed only after a long time.81 | None | |

| Hawkins and Jacoby found only partial compliance with rulings of the IACHR and ECtHR.83 | None | ||

| Staton and Romero found high compliance with IACHR rulings that were clearly expressed.90 | Positive | Ruling clarity | |

| Derogation from rights (n = 1) | Neumayer found that among ICCPR signatory states in declared states of emergency, democracies did not increase violations, whereas autocracies and some anocracies increased violations of both derogable and nonderogable rights.97 | Both | Regime type |

| Economic sanctions (n = 1) | Hafner-Burton and Montgomery found PTAs did not affect the likelihood of sanctions, but the likelihood was increased when the initiator had high centrality in the PTA network.49 | None and negative | Initiator centrality |

| Environment policies (n = 3) | Miles et al. found international environmental laws promoted positive behavioral changes by states and, to a lesser degree, improved the state of the environment.110 | Positive | |

| Breitmeier et al. found international environmental laws promoted significant compliance behavior by signatory states and sometimes improved the state of the environment, with knowledge of the problem, member states’ interests, and decision rule being key factors.113,115 | Positive | Knowledge Interests Decision rule | |

| Financial transactions restrictions (n = 4) | Simmons found states that ratified Article VIII of the IMF’s Articles of Agreement were less likely to impose restrictions on their accounts.34–36 | Positive | |

| von Stein34–36 found the positive effect in Simmons45 was not because of Article VIII itself but the IMF’s informal conditions for selecting and pressuring states to ratify Article VIII. | None | ||

| Simmons and Hopkins found ratifying IMF Article VIII reduced account restrictions, even after accounting for selection effects.46 | Positive | ||

| Grieco et al. found states that ratified IMF Article VIII were less likely to impose account restrictions, even if their political orientation shifted away from monetary openness.60 | Positive | ||

| Immunity agreements for international crimes (n = 2) | Kelley found states that valued the ICC and respected the rule of law were more likely to reject a nonsurrender agreement with the United States that would violate Article 86 of the Rome Statute.102 | Positive | |

| Nooruddin and Payton found states that entered the ICC, especially those with high rule of law, had high GDP, had defense pacts with the United States or were sanctioned by the United States and took longer to sign a BIA with the United States, whereas states that traded heavily with the United States signed more quickly.104 | Both | ICC membership US relations | |

| Personal integrity rights (n = 12) | Keith found ratifying the ICCPR did not improve personal integrity rights practices.68 | None | |

| Hafner-Burton found PTAs requiring member states to improve their human rights practices were more effective than were HRAs in improving personal integrity rights practices.27 | Positive and none | ||

| Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui found ratifying human rights treaties did not improve personal integrity rights practices, but participation in global civil society activities did.70 | None | ||

| Neumayer found ratifying human rights treaties improved personal integrity rights practices in democratic states or states with strong engagement in global civil society.71 | Positive | Democracy Civil society | |

| Abouharb and Cingranelli found SAAs worsened personal integrity rights practices.72 | Negative | ||

| Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui found ratifying the CAT or ICCPR did not improve personal integrity rights practices of highly repressive states even long into the future, regardless of democracy and civil society.74 | None | ||

| Greenhill found membership in IGOs whose member states have strong human rights records improved personal integrity rights practices.82 | Positive | ||

| Hill found ratifying the ICCPR worsened personal integrity rights practices.84 | Negative | ||

| Kim and Sikkink found domestic and international prosecutions of human rights violations and truth commissions reduced repressions of personal integrity rights.85 | Positive | ||

| Cole found ratifying the ICESCR worsened labor rights laws but improved labor rights practices.92 | Both | ||

| Lupu found ratifying the ICCPR did not improve personal integrity rights practices.95 | None | ||

| Lupu found ratifying the CEDAW improved respect for women’s economic and social rights and ratifying the ICCPR did not improve personal integrity rights.96 | Positive and none | ||

| Social policies (n = 3) | Linos found the promulgation of global norms (through ratifying International Labor Organization conventions and large presence of INGOs) increased length of maternity leave.89 | Positive | |

| Kim and Boyle found SAAs did not increase education spending but citizen engagement in global civil society did.91 | None | ||

| Helfer and Voeten found ECtHR rulings on LGBT issues increased the likelihood that states under the ECtHR’s jurisdiction that had not yet adopted a pro-LGBT policy would do so.94 | Positive | ||

| Trade policies (n = 2) | Bown found commitment to trade liberalization following WTO or GATT trade disputes was greater if the trading partner had the ability to retaliate.24 | Positive | Ability to retaliate |

| Kucik and Reinhardt found WTO member states that could take advantage of the WTO’s antidumping flexibility provision agreed to tighter tariff bindings and applied lower tariffs.30 | Positive | Flexibility provision | |

| Impact on people, places, or products | |||

| Domestic institutions (n = 2) | Ginsburg found BITs did not improve and in some cases worsened domestic institutions.42 | None | |

| Busse et al. found BITs promoted institutional development and may thus substitute for domestic measures to improve political governance.66 | Positive | ||

| Foreign investment (n = 27) | UNCTAD found BITs slightly increased FDI to developing countries.33 | Positive | |

| Banga found BITs with developed countries increased FDI inflows to developing countries.37 | Positive | ||

| Davies found renegotiations on BTTs involving the United States did not increase FDI stocks and affiliate sales in the United States.38 | None | ||

| Hallward-Driemeier found BITs did not increase FDI inflows to developing countries.39 | None | ||

| Egger and Pfaffermayr found BITs increased outward FDI stocks but only if they have been fully implemented.40 | Positive | Fully implemented | |

| di Giovanni found BTTs and bilateral service agreements increased M&A flows.41 | Positive | ||

| Grosse and Trevino found BITs signed by states in Central and Eastern Europe increased FDI inflows to the region.43 | Positive | ||

| Neumayer and Spess found BITs with developed countries increased FDI inflows to developing countries.44 | Positive | ||

| Egger and Merlo (2007) found BITs increased outward FDI stocks to host countries, with their long-term impact being greater than was their short-term impact.47 | Positive | Time | |

| Büthe and Milner found WTO or GATT membership, PTAs, and BITs increased FDI inflows to developing countries.48,56 | Positive | ||

| Millimet and Kumas found BTTs increased inbound and outbound US FDI activity (i.e., flows, stocks, and affiliate sales) in countries with low FDI activity and decreased inbound and outbound US FDI activity in countries with high FDI activity.50 | Both | Base FDI activity | |

| Yackee found BITs, even the formally strongest ones with international arbitration provisions, did not increase FDI inflows to developing countries.51 | None | ||

| Aisbett found that although BITs seemingly increased FDI outflows, the measured effect was simply because of the endogeneity of BIT adoption.52 | None | ||

| Barthel et al. found DTTs increased FDI stocks between partner countries.53 | Positive | ||

| Blonigen and Davies found recently formed BTTs decreased outbound FDI stocks and flows to partner countries.54 | Negative | ||

| Blonigen and Davies found BTTs involving the United States decreased outbound FDI stocks and affiliate sales from the United States and did not affect inbound FDI stocks and affiliate sales to the United States.55 | None and negative | ||

| Coupé et al. found BITs, but not DTTs, increased FDI inflows to countries undergoing economic transition.57 | Positive and none | Economic transition | |

| Egger et al. found BTTs decreased outward FDI stocks to host countries.58 | Negative | ||

| Gallagher and Birch found BITs with the United States did not increase FDI inflows from the United States to Latin American and Mesoamerican states, whereas BITs with all countries increased total FDI inflows to Latin American states.59 | None and positive | ||

| Louie and Rousslang found BTTs with the United States did not affect the rates of return that US companies required on their FDI.61 | None | ||

| Millimet and Kumas found BTTs increased time-lagged inbound FDI stocks and flows but did not affect inbound affiliate sales and outbound FDI stocks, flows, and affiliate sales.62 | Positive and none | ||

| Neumayer found DTTs with the United States increased outbound FDI stocks from the United States, whereas DTTs with all countries increased general inbound FDI stocks and FDI inflows but only in middle-income countries.63 | Positive | Economic status | |

| Salacuse and Sullivan found BITs with the United States increased FDI inflows to developing countries, both generally from other countries and specifically from the United States.64 | Positive | ||

| Yackee found BITs decreased FDI inflows to developing countries, whereas those signed with countries at low political risk increased FDI inflows.65 | Both | Political risk | |

| Busse et al. found BITs increased FDI inflows to developing countries.66 | Positive | ||

| Tobin and Rose-Ackerman found BITs increased FDI inflows to developing countries that had a suitable political–economic environment.67 | Positive | Investment environment | |

| Government stability (n = 2) | Abouharb and Cingranelli found SAAs increased the probability and prevalence of antigovernment rebellion.72 | Negative | |

| Hollyer and Rosendorff found autocracies that ratified the CAT had longer tenures in office and experienced less oppositional activities.88 | Positive | ||

| Health and well-being (n = 2) | Abouharb and Cingranelli found SAAs led to worse quality of life as measured by basic literacy rate, infant mortality, and life expectancy at aged 1 year.72 | Negative | |

| Palmer et al. found ratifying human rights treaties did not improve life expectancy, infant mortality, maternal mortality, or child mortality.76 | None | ||

| Peace (n = 4) | Meernik found judicial actions of the ICTY did not improve societal peace in Bosnia.99 | None | |

| Simmons and Danner found the ICC terminated civil conflicts and promoted engagement in peace agreements in nondemocratic and low rule-of-law member states.105 | Positive | Nondemocracy | |

| Hafner-Burton and Montgomery found membership in IGOs increased the likelihood of participation in militarized international disputes.100 | Negative | ||

| Hafner-Burton and Montgomery found membership in trade institutions decreased the likelihood of militarized disputes between states with relatively equal economic positions and increased the likelihood of militarized disputes between states with unequal positions.32 | Both | Economic status | |

| Pollution (n = 6) | Mitchell found a treaty mandating tankers to install pollution-reduction equipment was more effective than was a treaty that set a legal limit to tanker oil discharges.106 | Both | |

| Murdoch and Sandler found the Montreal Protocol did not reduce CFC emissions but rather codified previous voluntary reductions by member states.107 | None | ||

| Murdoch et al. found the Helsinki Protocol reduced sulfur emissions but the Sofia Protocol did not reduce nitrogen oxides emissions in European states because of differences in the source and spread of each pollutant.108 | Both | ||

| Helm and Sprinz found the Helsinki Protocol reduced sulfur dioxide emissions and the Oslo Protocol reduced nitrogen dioxide emissions but fell short of the calculated optimum levels.109 | Positive and none | ||

| Finus and Tjøtta found the sulfur emission reduction targets set by the Oslo Protocol were lower than were those expected without an international agreement.111 | None | ||

| Ringquist and Kostadinova found the Helsinki Protocol did not reduce sulfur emissions in Europe.112 | None | ||

| Public support (n = 1) | Putnam and Shapiro found public support for government action against Myanmar increased when respondents were informed that Myanmar’s forced labor practices violated international law.98 | Positive | |

| Torture (n = 8) | Hathaway found ratifying the CAT led to worse torture practices, whereas additionally ratifying Article 21 of the CAT (which allows state to state complaints) did not change them.69 | None and negative | |

| Gilligan and Nesbitt found ratifying the CAT did not improve torture practices.75 | None | ||

| Powell and Staton found ratifying the CAT improved torture practices in states with strong domestic systems of legal enforcement.77 | Positive | Legal enforcement | |

| Hill found ratifying the CAT led to worse torture practices.84 | Negative | ||

| Hollyer and Rosendorff found autocracies that ratified the CAT continued their torture practices but at slightly lower levels.88 | Positive | ||

| Conrad and Ritter found ratifying the CAT improved torture practices in dictatorships with politically secure leaders but did not change practices in those with politically insecure leaders.93 | Positive and none | Leader security | |

| Lupu found ratifying the CAT was not associated with lower torture rates.96 | None | ||

| Conrad found ratifying the CAT increased the likelihood of torture in dictatorships with power sharing but only when judicial effectiveness was high.87 | Negative | Judicial effectiveness | |

| Trade flows (n = 5) | Rose found WTO or GATT membership did not increase trade.25 | None | |

| Gowa and Kim found GATT membership increased trade between Canada, France, Germany, United Kingdom, and United States but did not affect trade between other member states.26 | Positive and none | ||

| Subramanian and Wei found WTO or GATT membership increased trade for industrial states, especially when trading partners were also WTO or GATT members.28 | Positive | Industrialized partners | |

| Tomz et al. found WTO or GATT participation, formally or as a nonmember, increased trade.29 | Positive | ||

| Mansfield and Reinhardt found membership in the WTO or GATT and PTAs reduced export volatility and thereby increased export levels.31 | Positive | ||

| War crimes and genocide (n = 3) | Hathaway found ratifying the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide led to worse genocide practices.69 | Negative | |

| Valentino et al. found international humanitarian law did not reduce intentional civilian fatalities during wartime, regardless of regime type and identity of enemy combatants.101 | None | ||

| Morrow found democracies had fewer violations of international humanitarian laws during wartime, and joint ratification of laws promoted reciprocity between warring states.103 | Positive | Democracy | |

| Water levels (n = 1) | Bernauer and Siegfried found water release from the Toktogul reservoir after the 1998 Naryn/Syr Darya basin agreement met mandated levels, but was significantly higher than the calculated optimum levels.114 | Positive and none | |

Note. BIA = Bilateral Immunity Agreement; BIT = Bilateral Investment Treaty; BTT = Bilateral Tax Treaty; CAT = Convention Against Torture; CEDAW = Convention to Eliminate All Forms of Discrimination Against Women; CERD = Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination; CFC = chlorofluorocarbon; CRC = Convention on the Rights of the Child; DTT = Double Taxation Treaty; ECtHR = European Court of Human Rights; FDI = foreign direct investment; GATT = General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade; HRC = Human Rights Committee; IACHR = Inter-American Court of Human Rights; IASHRP = Inter-American System of Human Rights Protection; ICC = International Criminal Court; ICCPR = International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; ICESCR = International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights; ICTY = International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia; IGO = intergovernmental organization; IMF = International Monetary Fund; INGO = international nongovernmental organization; LGBT = lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender; M&A = merger and acquisition; PTA = Preferential Trade Agreement; SAA = Structural Adjustment Agreement; UN = United Nations; WTO = World Trade Organization.

IMPORTANCE OF INCENTIVES, INSTITUTIONS, AND INTERESTS

What impact can be expected from global health treaties? According to our analysis, not very much. International treaties have consistently succeeded in shaping economic matters just as they have consistently failed in achieving social progress (including improved health status).

But global health treaties are not necessarily destined to fail. Although there may be intrinsic differences between economic and social domains, there are at least 3 differences in how treaties are characteristically designed between these areas that suggest ways new global health treaties could be constructed to achieve positive effect.

First, international economic treaties tend to provide immediate benefits to states and governing elites such that action aligns with their short-term self-interests. International treaties on social issues rarely offer immediate benefits and usually impose costs on those in charge. This suggests new global health treaties can have greater impact if they too include incentives for those with power to act on them. This hypothesis aligns with neorealist theories from political science and international relations and game theory from economics that emphasize the role of incentives in shaping national agendas and the priorities of elites.79,123,124

Second, international economic treaties tend to incorporate institutional mechanisms for promoting compliance, dispute resolution, and accountability that are typically absent from socially focused treaties that must instead rely on the “naming and shaming” efforts of progressive states and civil society. Examples of institutional mechanisms include automatic penalties, sanctions, mandatory arbitration, regular reporting requirements, and compliance assessments. This suggests that new global health treaties can have greater effect if they include institutions specifically designed to bring edicts into effect. This hypothesis aligns with institutionalist theories that emphasize the role of implicit or explicit structures in defining expectations, constraining decisions, distributing power, and incentivizing behavior125,126 as well as international legal process theories that view treaties as organizing devices and constraints on diplomatic practice.127

Third, international economic treaties tend to have the support of powerful interest groups who advocate their full implementation and few strong opponents who can advocate against them. This most notably includes those industry groups and multinational corporations with extremely generous lobbying budgets, worldwide affiliates, and access to sophisticated advocacy professionals, which are resources not typically used by industry to address social challenges. Progressive civil society organizations are comparatively underfunded. This suggests that new global health treaties can have greater impact either if their aims match those of powerful interests or if supporters can build sufficiently strong coalitions of their own. This hypothesis aligns with institutionalist theories that stress how treaties serve as focal points for social mobilization and provide resources for political movements,79,124 critical legal theories that view treaties as offering language with which actors assert claims,128,129 and network theories that emphasize the role of transnational advocacy networks and networked governmental authorities in shaping domestic political decision making.130,131

Less important, this analysis suggests, is for new global health treaties to (1) allow individuals to bring claims against their own governments (e.g., domestic human rights litigation), (2) address an urgent imperative requiring immediate action (e.g., climate change), or (3) promote ideals of an ethical world (e.g., peace). These features are typically absent from the seemingly effective international economic treaties and characteristic of the seemingly less effective treaties addressing social problems. This hypothesis is in opposition to legal theories supporting individual litigation,132 cosmopolitanism’s ideal of shared morality,133,134 and constructivist theories that emphasize ideas, norms, language, and the power of treaty-making processes.22,135–138

EXPERIMENTAL AND QUASIEXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Our analysis of 90 quantitative evaluations is a start in assessing what impact can be expected from global health treaties and in identifying design characteristics of treaties that have historically achieved greater effect. But global health decision makers need stronger and more specific conclusions than existing research can offer. This is a matter not just of needing more research but also of needing a greater diversity of methodological approaches.

All but 2 of the 90 quantitative evaluations relied on observational study designs that by themselves do not facilitate causal inferences. The vast majority employed time-series cross-sectional analysis (n = 69), with the remaining studies using time-series analysis (n = 3), 33,99,114 cross-sectional analysis (n = 6),33,61,76,90,102,111 Cox proportionate hazard models (n = 4),34–36,80,104,105 generalized method of moments analysis (n = 1),47 quantile treatment effect distribution analysis (n = 1),50 formal model analysis (n = 1),109 and descriptive statistics (n = 7).81,83,106,110,113,115

This is not all bad news. Time-series cross-sectional analysis is a relatively strong design that increases the number of and variation across observations by incorporating both the temporal (e.g., year) and spatial (e.g., country) dimensions of data. This makes parameter estimates more robust and allows the testing of variables that would display negligible variability when examined across either time or space alone.139,140 But like most models of observational data, causal inferences from time-series cross-sectional analyses are undermined by the possibility of confounding, reverse causation and the nonrandom distribution of interventions (i.e., international treaties) that may be linked to the outcomes measured.141,142

Unfortunately we found only 2 experimental or quasiexperimental evaluations of specific international treaties for any policy area, despite these representing stronger methodological designs for measuring effects. The single experiment we found was a survey of 2724 American adults testing public reaction to Myanmar’s forced labor practices, which found that respondents who were told that Myanmar’s actions violated an international law were more likely to support sanctions than were uninformed respondents.98 The quasiexperiment was a difference-in-difference analysis of bilateral tax treaties’ effect on foreign investment.58 Quasiexperimental methods have been used extensively to evaluate the effects of legislation, policies, and regulations in domestic contexts,143–146 but they do not appear to be popular in the study of international instruments thus far.

CONCLUSIONS

States have increasingly relied on international treaties to manage the harmful effects of globalization and reap its potential benefits. Sometimes they seek to mitigate a threat or resolve a collective action problem; other times they hope to promote a specific norm, signal intentions, or encourage the production of global public goods. Motivating such international treaty making is the idea that states are willing to constrain their behavior or accept positive obligations if other states do the same. This type of international cooperation is viewed by many as essential for progress across many policy areas, including for health, because of how risks now travel between states irrespective of national boundaries (e.g., pandemics), and where attaining rewards often requires coordinated action or resources on a scale beyond any single country’s willingness to pay (e.g., research and development for neglected diseases).

But evidence of international treaties’ effects on health is scant, making it difficult to draw reasonable inferences on what impact can be expected from new treaties that either regulate health matters or aim to promote better health outcomes. The only 2 studies that evaluated health outcomes found that human rights treaties had no impact on a variety of health indicators76 and that structural adjustment agreements had a negative effect on them.72

As long as the evidence remains unclear, we should not assume new global health treaties will achieve positive outcomes. Their inconsistent effects undermine the oft-cited claim that treaties can have a greater effect on people, places, products, or policies than do other instruments, such as political declarations, codes of practice, or resolutions.147 The precise mechanism through which states make commitments to each other seems less important than does the content of the commitment, the regime complexes it joins,148,149 financial allocations,150 dispute resolution procedures,151 processes for promoting accountability,152 and the support of states and other stakeholders to see commitments fully implemented.153 Arguments about “hard law” versus “soft law” and “binding” versus “nonbinding” seem less important than do strategic conversations about incentivizing elites, institutionalizing compliance mechanisms, and activating interest groups. Without such conversations, new global health treaties will have less chance of achieving their intended impact, or, worse, they could even cause harm as some treaties may already have done.

Acknowledgments

S. J. H. is financially supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Trudeau Foundation.

Thank you to Julio Frenk, Benn McGrady, Graham Reynolds, and the participants of seminars at Chatham House, Harvard School of Public Health, Osgoode Hall Law School, Oxford University, Queen’s University, and the University of British Columbia for feedback on earlier drafts of this article and to Jennifer Edge, Zain Rizvi, Vivian Tam, and Charlie Tan for research assistance.

Note. S. J. H. was previously employed by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Secretary-General’s Office. J.-A. R. was chair of the World Health Organization’s Consultative Expert Working Group on Research and Development: Financing and Coordination that recommended adoption of an international convention on health research and development.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was necessary because no human participants were involved.

References

- 1.Sridhar D. Regulate alcohol for global health. Nature. 2012;482:302. doi: 10.1038/482302a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gostin LO. Non-communicable diseases: healthy living needs global governance. Nature. 2014;511(7508):147–149. doi: 10.1038/511147a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fighting fake drugs: the role of WHO and pharma. Lancet. 2011;377(9778):1626. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60656-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kohler JC, Makady A. Harnessing global health diplomacy to curb corruption in health. J Health Dipl. 2013;1(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oxman AD, Bjørndal A, Becerra-Posada F et al. A framework for mandatory impact evaluation to ensure well informed public policy decisions. Lancet. 2010;375(9712):427–431. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basu S. Should we propose a global nutrition treaty? 2012. Available at: http://epianalysis.wordpress.com/2012/06/26/nutritiontreaty. Accessed January 4, 2014.

- 7.Urgently needed: a framework convention for obesity control. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):741. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dentico N, Ford N. The courage to change the rules: a proposal for an essential health R&D treaty. PLoS Med. 2005;2(2):e14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gostin LO. Meeting basic survival needs of the world’s least healthy people: toward a framework convention on global health. Georgetown Law J. 2008;96(2):331–392. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fidler DP. The globalization of public health: the first 100 years of international health diplomacy. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79(9):842–849. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor AL. Global governance, international health law and WHO: looking towards the future. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80(12):975–980. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gostin LO. World health law: toward a new conception of global health governance for the 21st century. Yale J Health Policy Law Ethics. 2005;5(1):413–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman SJ, Røttingen JA. Split WHO in two: strengthening political decision-making and securing independent scientific advice. Public Health. 2014;128(2):188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization. 45th ed. 2005. Available at: http://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2014.

- 15.Hoffman SJ. Ending medical complicity in state-sponsored torture. Lancet. 2011;378(9802):1535–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60816-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hathaway OA. Why do countries commit to human rights treaties? J Conflict Resolut. 2007;51(4):588–621. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hafner-Burton E, Victor DG, Lupu Y. Political science research on international law: the state of the field. Am J Int Law. 2012;106(1):47–97. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaffer G, Ginsburg T. The empirical turn in international legal scholarship. Am J Int Law. 2012;106(1):1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman SJ, Røttingen JA. Dark sides of the proposed Framework Convention on Global Health’s many virtues: a systematic review and critical analysis. Health Hum Rights. 2013;15(1):117–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wipfli HL, Fujimoto K, Valente TW. Global tobacco control diffusion: the case of the framework convention on tobacco control. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(7):1260–1266. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.167833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanders-Jackson AN, Song AV, Hiilamo H, Glantz SA. Effect of the framework convention on tobacco control and voluntary industry health warning labels on passage of mandated cigarette warning labels from 1965 to 2012: transition probability and event history analyses. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(11):2041–2047. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wipfli H, Huang G. Power of the process: evaluating the impact of the framework convention on tobacco control negotiations. Health Policy. 2011;100(2–3):107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edge JS, Hoffman SJ. Empirical impact evaluation of the WHO global code of practice on the international recruitment of health personnel in Australia, Canada, UK and USA. Global Health. 2013;9:60. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-9-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bown CP. On the economic success of GATT/WTO dispute settlement. Rev Econ Stat. 2004;86(3):811–823. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rose AK. Do we really know that the WTO increases trade? Am Econ Rev. 2004;94(1):98–114. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gowa J, Kim SY. An exclusive country club: the effects of the GATT on trade, 1950–94. World Polit. 2005;57(4):453–478. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hafner-Burton EM. Trading human rights: how preferential trade agreements influence government repression. Int Organ. 2005;59(3):593–629. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Subramanian A, Wei SJ. The WTO promotes trade, strongly but unevenly. J Int Econ. 2007;72(1):151–175. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomz M, Goldstein JL, Rivers D. Do we really know that the WTO increases trade? Am Econ Rev. 2007;97(5):2005–2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kucik J, Reinhardt E. Does flexibility promote cooperation? An application to the global trade regime. Int Organ. 2008;62(3):477–505. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mansfield ED, Reinhardt E. International institutions and the volatility of international trade. Int Organ. 2008;62(4):621–652. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hafner-Burton EM, Montgomery AH. War, trade and distrust: why trade agreements don’t always keep the peace. Conflict Management & Peace Sci. 2012;29(3):257–278. [Google Scholar]

- 33.United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Bilateral Investment Treaties in the Mid-1990s. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simmons BA. International law and state behavior: commitment and compliance in international monetary affairs. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2000;94(4):819–835. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simmons BA. Money and the law: why comply with the public international law of money? Yale J Int Law. 2000;25(2):323–362. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simmons BA. The legalization of international monetary affairs. Int Organ. 2000;54(3):573–602. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Banga R. Impact of Government Policies and Investment Agreements on FDI Inflows. Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations. Working Paper No. 116; 2003.

- 38.Davies RB. Tax treaties, renegotiations, and foreign direct investment. Econ Anal Policy. 2003;33(2):251–273. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hallward-Driemeier M. Do Bilateral Investment Treaties Attract Foreign Direct Investment? Only a Bit—and They Could Bite. World Bank Policy Research. Working Paper No. 3121; 2003.

- 40.Egger P, Pfaffermayr M. The impact of bilateral investment treaties on foreign direct investment. J Comp Econ. 2004;32(4):788–804. [Google Scholar]

- 41.di Giovanni J. What drives capital flows? The case of cross-border M&A activity and financial deepening. J Int Econ. 2005;65(1):127–149. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ginsburg T. International substitutes for domestic institutions: bilateral investment treaties and governance. Int Rev Law Econ. 2005;25(1):107–123. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grosse R, Trevino LJ. New institutional economics and FDI location in Central and Eastern Europe. Manage Rev. 2005;45(2):123–145. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neumayer E, Spess L. Do bilateral investment treaties increase foreign direct investment to developing countries? World Dev. 2005;33(10):1567–1585. [Google Scholar]

- 45.von Stein J. Do treaties constrain or screen? Selection bias and treaty compliance. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2005;99(4):611–622. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simmons BA, Hopkins DJ. The constraining power of international treaties: theory and methods. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2005;99(4):623–631. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Egger P, Merlo V. The impact of bilateral investment treaties on FDI dynamics. World Econ. 2007;30(10):1536–1549. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Büthe T, Milner HV. The politics of foreign direct investment into developing countries: increasing FDI through international trade agreements? Am J Pol Sci. 2008;52(4):741–762. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hafner-Burton EM, Montgomery AH. Power or plenty: how do international trade institutions affect economic sanctions? J Conflict Resolut. 2008;52(2):213–242. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Millimet DL, Kumas A. Reassessing the Effects of Bilateral Tax Treaties on US FDI Activity. Dallas, TX: Southern Methodist University; 2008. Working Paper No. 704. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yackee JW. Bilateral investment treaties, credible commitment, and the rule of (international) law: do BITs promote foreign direct investment? Law Soc Rev. 2008;42(4):805–832. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aisbett E. Bilateral investment treaties and foreign direct investment: correlation versus causation. In: Sauvant K, Sachs L, editors. The Effect of Treaties on Foreign Direct Investment: Bilateral Investment Treaties, Double Taxation Treaties, and Investment Flows. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 395–437. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barthel F, Busse M, Neumayer E. The impact of double taxation treaties on foreign direct investment: evidence from large dyadic table data. Contemp Econ Policy. 2009;28(3):366–377. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blonigen BA, Davies RB. Do bilateral tax treaties promote foreign direct investment? In: Sauvant K, Sachs L, editors. The Effect of Treaties on Foreign Direct Investment: Bilateral Investment Treaties, Double Taxation Treaties, and Investment Flows. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 461–485. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blonigen BA, Davies RB. The effects of bilateral tax treaties on U.S. FDI Activity. In: Sauvant K, Sachs L, editors. The Effect of Treaties on Foreign Direct Investment: Bilateral Investment Treaties, Double Taxation Treaties, and Investment Flows. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 485–513. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Büthe T, Milner HV. Bilateral investment treaties and foreign direct investment: a political analysis. In: Sauvant K, Sachs L, editors. The Effect of Treaties on Foreign Direct Investment: Bilateral Investment Treaties, Double Taxation Treaties, and Investment Flows. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 171–225. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coupé T, Orlova I, Skiba A. The effect of tax and investment treaties on bilateral FDI flows to transition countries. In: Sauvant K, Sachs L, editors. The Effect of Treaties on Foreign Direct Investment: Bilateral Investment Treaties, Double Taxation Treaties, and Investment Flows. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 681–715. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Egger P, Larch M, Pfaffermayr M, Winner H. The impact of endogenous tax treaties on foreign direct investment: theory and empirical evidence. In: Sauvant K, Sachs L, editors. The Effect of Treaties on Foreign Direct Investment: Bilateral Investment Treaties, Double Taxation Treaties, and Investment Flows. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 513–541. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gallagher KP, Birch MBL. Do investment agreements attract investment? Evidence from Latin America. In: Sauvant K, Sachs L, editors. The Effect of Treaties on Foreign Direct Investment: Bilateral Investment Treaties, Double Taxation Treaties, and Investment Flows. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 295–311. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grieco JM, Gelpi CF, Warren TC. When preferences and commitments collide: the effect of relative partisan shifts on international treaty compliance. Int Organ. 2009;63(2):341–355. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Louie HJ, Rousslang DJ. Host-country governance, tax treaties, and U.S. direct investment abroad. In: Sauvant K, Sachs L, editors. The Effect of Treaties on Foreign Direct Investment: Bilateral Investment Treaties, Double Taxation Treaties, and Investment Flows. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 541–563. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Millimet DL, Kumas A. It’s all in the timing: assessing the impact of bilateral tax treaties on U.S. FDI activity. In: Sauvant K, Sachs L, editors. The Effect of Treaties on Foreign Direct Investment: Bilateral Investment Treaties, Double Taxation Treaties, and Investment Flows. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 635–659. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neumayer E. Do double taxation treaties increase foreign direct investment to developing countries? In: Sauvant K, Sachs L, editors. The Effect of Treaties on Foreign Direct Investment: Bilateral Investment Treaties, Double Taxation Treaties, and Investment Flows. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 659–687. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salacuse JW, Sullivan NP. Do BITS really work?: An evaluation of bilateral investment treaties and their grand bargain. In: Sauvant K, Sachs L, editors. The Effect of Treaties on Foreign Direct Investment: Bilateral Investment Treaties, Double Taxation Treaties, and Investment Flows. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 109–171. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195388534.001.0001. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yackee J. Do BITs really work? Revisiting the empirical link between investment treaties and foreign direct investment. In: Sauvant K, Sachs L, editors. The Effect of Treaties on Foreign Direct Investment: Bilateral Investment Treaties, Double Taxation Treaties, and Investment Flows. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 379–395. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Busse M, Königer J, Nunnenkamp P. FDI promotion through bilateral investment treaties: more than a bit? Rev World Econ. 2010;146:147–177. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tobin JL, Rose-Ackerman S. When BITs have some bite: the political–economic environment for bilateral investment treaties. Rev Int Organ. 2011;6(1):1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Keith LC. The United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights: does it make a difference in human rights behavior? J Peace Res. 1999;36(1):95–118. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hathaway OA. Do human rights treaties make a difference? Yale Law J. 2002;111(8):1935–2042. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hafner-Burton EM, Tsutsui K. Human rights in a globalizing world: the paradox of empty promises. Am J Sociol. 2005;110(5):1373–1411. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Neumayer E. Do international human rights treaties improve respect for human rights? J Conflict Resolut. 2005;49(6):925–953. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Abouharb R, Cingranelli D. Human Rights and Structural Adjustment. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cardenas S. Conflict and Compliance: State Responses to International Human Rights Pressure. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hafner-Burton EM, Tsutsui K. Justice lost! The failure of international human rights law to matter where needed most. J Peace Res. 2007;44(4):407–425. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gilligan MJ, Nesbitt NH. Do norms reduce torture? J Legal Stud. 2009;38(2):445–470. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Palmer A, Tomkinson J, Phung C et al. Does ratification of human-rights treaties have effects on population health? Lancet. 2009;373(9679):1987–1992. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Powell EJ, Staton JK. Domestic judicial institutions and human rights treaty violation. Int Stud Q. 2009;53(1):149–174. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Simmons BA. Civil rights in international law: compliance with aspects of the “International Bill of Rights.”. Indiana J Glob Leg Stud. 2009;16(2):437–481. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Simmons BA. Mobilizing for Human Rights: International Law in Domestic Politics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Simmons BA. Should states ratify protocol? Process and consequences of the optional protocol of the ICESCR. Norwegian J Hum Rights. 2009;27(1):64–81. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Basch F, Filippini L, Laya A, Nino M, Rossi F, Schreiber B. The effectiveness of the inter-American system of human rights protection: a quantitative approach to it functioning and compliance with its decisions. Int J Hum Rights. 2010;7(12):9–35. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Greenhill B. The company you keep: international socialization and the diffusion of human rights norms. Int Stud Q. 2010;54(1):127–145. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hawkins D, Jacoby W. Partial compliance: a comparison of the European and inter-American courts of human rights. J Int Law Int Relat. 2010;6(1):35–85. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hill DW., Jr Estimating the effects of human rights treaties on state behavior. J Polit. 2010;72(4):1161–1174. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim H, Sikkink K. Explaining the deterrence effect of human rights prosecutions for transitional countries. Int Stud Q. 2010;54(4):939–963. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cole WM. Individuals v. States: An Analysis of Human Rights Committee Rulings, 1979–2007. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University; 2011. Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Conrad CR. Divergent incentives for dictators: domestic institutions and (international promises not to) torture. J Conflict Resolution. 2014;58(1):34–67. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hollyer JR, Rosendorff PB. Why do authoritarian regimes sign the convention against torture? Signaling, domestic politics and non- compliance. Q J Pol Sci. 2011;6(3–4):275–327. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Linos K. Diffusion through democracy. Am J Pol Sci. 2011;55(3):678–695. [Google Scholar]

- 90. Staton JK, Romero A. Clarity and compliance in the inter-American human rights system. Presented at: International Political Science Association–European Consortium of Political Research Joint Conference; February 16–19, 2011; Sao Paulo, Brazil.

- 91.Kim M, Boyle EH. Neoliberalism, transnational education norms, and education spending in the developing world, 1983–2004. Law Soc Inq. 2012;37(2):367–394. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cole W. Strong walk and cheap talk: the effect of the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights on policies and practices. Social and Economic Rights in Law and Practice. 2013;92(1):165–194. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Conrad CR, Ritter EH. Treaties, tenure, and torture: the conflicting domestic effects of international law. J Polit. 2013;75(2):397–409. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Helfer LR, Voeten E. International courts as agents of legal change: evidence from LGBT rights in Europe. Int Organ. 2014;68(1):77–110. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lupu Y. Best evidence: the role of information in domestic judicial enforcement of international human rights agreements. Int Organ. 2013;67(3):469–503. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lupu Y. The informative power of treaty commitment: using the spatial model to address selection effects. Am J Pol Sci. 2013b;57(4):912–925. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Neumayer E. Do governments mean business when they derogate? Human rights violations during declared states of emergency. Rev Int Organ. 2013;8(1):1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Putnam TL, Shapiro JN. International law and voter preferences: the case of foreign human rights violations. New York, NY: Columbia University; 2013. Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Meernik J. Justice and peace? How the International Criminal Tribunal affects societal peace in Bosnia. J Peace Res. 2005;42(3):271–289. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hafner-Burton EM, Montgomery AH. Power positions: international organizations, social networks, and conflict. J Conflict Resolut. 2006;50(1):3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Valentino B, Huth P, Croco S. Covenants without the sword: international law and the protection of civilians in times of war. World Polit. 2006;58(3):339–377. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kelley J. Who keeps international commitments and why? The International Criminal Court and bilateral nonsurrender agreements. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2007;101(3):573–589. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Morrow JD. When do states follow the laws of war? Am Polit Sci Rev. 2007;101(3):559–572. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nooruddin I, Payton AL. Dynamics of influence in international politics: the ICCs, BIAs, and economic sanctions. J Peace Res. 2010;47(6):711–721. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Simmons BA, Danner A. Credible commitments and the International Criminal Court. Int Organ. 2010;64(2):225–256. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mitchell RB. Regime design matters: intentional oil pollution and treaty compliance. Int Organ. 1994;48(3):425–458. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Murdoch JC, Sandler T. The voluntary provision of a pure public good: the case of reduced CFC Emissions and the Montreal Protocol. J Public Econ. 1997;63(3):331–349. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Murdoch JC, Sandler T, Sargent K. A tale of two collectives: sulphur versus nitrogen oxides emission reduction in Europe. Economica. 1997;64(254):281–301. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Helm C, Sprinz D. Measuring the effectiveness of international environmental regimes. J Conflict Resolut. 2000;44(5):630–652. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Miles E, Underdal A, Andresen S, Wettestad J, Skjaerseth JB, Carlin EM. Environmental Regime Effectiveness: Confronting Theory With Evidence. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Finus M, Tjøtta S. The Oslo Protocol on sulfur reduction: the great leap forward? J Public Econ. 2003;87(9–10):2031–2048. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ringquist EJ, Kostadinova T. Assessing the effectiveness of international environmental agreements: the case of the 1985 Helsinki Protocol. Am J Pol Sci. 2005;49(1):86–102. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Breitmeier H, Young O, Zurn M. Analyzing International Environmental Regimes: From Case Study to Database. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bernauer T, Siegfried T. Compliance and performance in international water agreements: the case of the Naryn/Syr Darya Basin. Glob Gov. 2008;14(4):479–501. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Breitmeier H, Underdal A, Young OR. The effectiveness of international environmental regimes: comparing and contrasting findings from quantitative research. Int Stud Rev. 2011;13(4):579–605. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Merry SE. Transnational human rights and local activism: mapping the middle. Am Anthropol. 2006;108(1):38–51. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Merry SE. New legal realism and the ethnography of transnational law. Law Soc Inq. 2006;31(4):975–995. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Keith LC. Judicial independence and human rights protection around the world. Judicature. 2002;85(4):195–200. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Snyder J, Vinjamuri L. Trials and errors: principle and pragmatism in strategies of international justice. Int Secur. 2003;28(3):5–44. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ku J, Nzelibe J. Do international criminal tribunals deter or exacerbate humanitarian atrocities? Washington Univ Law Rev. 2006;84(4):777–833. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Prakash A, Potoski M. Racing to the bottom? Trade, environmental governance and ISO 14001. Am J Pol Sci. 2006;50(2):350–364. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Victor DG. Toward effective international cooperation on climate change: numbers, interests and institutions. Glob Environ Polit. 2006;6(3):90–103. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Snidal D. The game theory of international politics. World Polit. 1985;38(1):25–57. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hoffman SJ. Mitigating inequalities of influence among states in global decision-making. Glob Policy J. 2012;3(4):421–432. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Krasner SD. Structural causes and regime consequences: regimes as intervening variables. Int Organ. 1982;36(2):185–205. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Waltz K. Theory of International Politics. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Chayes A, Ehrlich T, Lowenfeld AF. International Legal Process. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Koskenniemi M. The politics of international law. Eur J Int Law. 1990;1(1):4–32. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kennedy D. The Dark Sides of Virtue: Reassessing International Humanitarianism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Keck ME, Sikkink K. Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Slaughter AM. A New World Order. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Koh HH. How is international human rights law enforced? Indiana Law J. 1999;74(4):1397–1417. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Archibugi D. The Global Commonwealth of Citizens: Toward Cosmopolitan Democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Held D. Restructuring global governance: cosmopolitanism, democracy and the global order. Millennium. 2009;37(3):535–547. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Finnemore M. National Interests in International Society. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ruggie JG. What makes the world hang together? Neo-utilitarianism and the social constructivist challenge. Int Organ. 1998;52(4):855. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Wendt A. Anarchy is what states make of it: the social construction of power politics. Int Organ. 1992;46(2):391–425. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Yach D, Bettcher D. Globalisation of tobacco industry influence and new global responses. Tob Control. 2000;9(2):206–216. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Franzese R. Models for time-series-cross-section data. 2010. Available at: http://www-personal.umich.edu/∼franzese/Franzese.JWAC.TSCS.1.Introduction.pdf. Accessed January 6, 2014.

- 140. Podesta F. Recent developments in quantitative comparative methodology: the case of pooled time series-cross sectional analysis. Brescia, Italy: Universität Brescia; 2002. DSS Paper SOC 3–02.

- 141.Beck N, Katz JN. What to do (and not to do) with time-series cross-section data. Am Polit Sci Rev. 1995;89(3):634–647. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Sekhon JS. The statistics of causal inference in the social sciences. 2012. Available at: http://sekhon.berkeley.edu/causalinf/causalinf.pres.pdf. Accessed January 6, 2014.

- 143.Loftin C, McDowall D, Wiersema B, Talbert JC. Effects of restrictive licensing of handguns on homicide and suicide in the District of Columbia. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(23):1615–1620. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199112053252305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Humphreys DK, Eisner MP, Wiebe DJ. Evaluating the impact of flexible alcohol trading hours on violence: an interrupted time series analysis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e55581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Ma ZQ, Kuller LH, Fisher MA, Ostroff SM. Use of interrupted time-series method to evaluate the impact of cigarette excise tax increases in Pennsylvania, 2000–2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E169. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Morgan OW, Griffiths C, Majeed A. Interrupted time-series analysis of regulations to reduce paracetamol (acetaminophen) poisoning. PLoS Med. 2007;4(4):e105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Gostin LO, Friedman E. Towards a framework convention on global health: a transformative agenda for global health justice. Yale J Health Policy Law Ethics. 2013;13(1):1–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Alter KJ, Meunier S. The politics of international regime complexity. Perspect Polit. 2009;7(1):13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 149.Drezner DW. The power and peril of international regime complexity. Perspect Polit. 2009;7(1):65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Chang AY, Røttingen JA, Hoffman SJ, Moon S. Governance Arrangements for Health R&D. Geneva, Switzerland: Graduate Institute of International & Development Studies and Cambridge, MA: Harvard Global Health Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 151. Hoffman SJ. Making the International Health Regulations matter: promoting compliance through effective dispute resolution. In: Rushton S, Youde J, eds. Routledge Handbook on Global Health Security. Oxford, UK: Routledge. In Print.

- 152.Hoffman SJ, Røttingen JA. Global health governance after 2015. Lancet. 2013;382(9897):1018. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61966-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Hoffman SJ, Røttingen JA. Assessing implementation mechanisms for an international agreement on research and development for health products. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(11):854–863. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.109827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]