Abstract

Hydrogen/deuterium exchange (HDX) mass spectrometry (MS) is used for analyzing protein dynamics, protein folding/unfolding, and molecular interactions. Until this study, HDX MS experiments employed mass spectral resolving powers that afforded only one peak per nominal mass in a given peptide’s isotope distribution, and HDX MS data analysis methods were developed accordingly. A level of complexity that is inherent to HDX MS remained unaddressed, namely, various combinations of natural abundance heavy isotopes and exchanged deuterium shared the same nominal mass and overlapped at previous resolving powers. For example, an A + 2 peak is comprised of (among other isotopomers) a two-2H-exchanged/zero-13C isotopomer, a one-2H-exchanged/one-13C isotopomer, and a zero-2H-exchanged/two-13C isotopomer. Notably, such isotopomers differ slightly in mass as a result of the ~3 mDa mass defect between 2H and 13C atoms. Previous HDX MS methods did not resolve these isotopomers, requiring a natural-abundance-only (before HDX or “time zero”) spectrum and data processing to remove its contribution. It is demonstrated here that high-resolution mass spectrometry can be used to detect isotopic fine structure, such as in the A + 2 profile example above, deconvolving the isotopomer species resulting from deuterium incorporation. Resolving isotopic fine structure during HDX MS therefore permits direct monitoring of HDX, which can be calculated as the sum of the fractional peak magnitudes of the deuterium-exchanged isotopomers. This obviates both the need for a time zero spectrum as well as data processing to account for natural abundance heavy isotopes, saving instrument and analysis time.

Hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX MS) is used to characterize protein structure, dynamics, and the interactions between proteins and other molecules. Popular applications include folding and unfolding rates; how solvent conditions, mutation, post-translational modification, and interaction with other molecules affect protein structures; and the quality of biologics. Reviews of the mechanisms and many applications of HDX MS are available.1–3

While standardized approaches to HDX MS have not yet been realized, the workflow is somewhat conserved in the literature. Typically, proteolytic (classically nonspecific) degradation of proteins or protein complexes is carried out in solution under slow exchange reaction conditions. Under these “quench” conditions, nonprotected peptide fragments should not readily exchange such that the extent of deuteration correctly reflects protection characteristics of the intact system. These exchanged peptides are spatially separated via liquid chromatography (LC) and introduced to the mass spectrometer where measured peptide masses are compared to similar data sets of nonexchanged systems to determine the extent of deuteration for mapping structural protection features.

Improving the realized efficacy of this approach requires independent optimization of all component processes including proteolytic digestion conditions,4 LC separation methods,5–7 and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) fragmentation techniques.8–12 Automation of these steps in combination with MS/MS of exchange peptides lead to high-throughput platforms (DXMS),13,14 while further gains in robustness coupled with automated data interpretation15–22 recently culminated in an automated commercial HDX MS platform.7

Various combinations of natural abundance isotopomers and the isotopomers resulting from HDX shared the same nominal mass and their peaks therefore overlapped at previous MS resolving powers.23 This complexity, specifically various combinations of natural abundance isotopomers and deuterated isotopomers, is recalcitrant to chromatographic separation. Whereas a Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer (FTICR MS) at a resolving power >375 000 was able to mass resolve small molecule keto and enol isomers after deuterium labeling,24 higher resolving power is required for (normally larger) peptides. Although such fine structure was not previously resolved, it was shown to influence the peak shape of peptides analyzed by an FTICR MS instruments at resolving power ~100 00023 and should therefore also affect peak shape for Orbitrap instruments and potentially low mass peptides on modern quadrupole-time-of-flights (Q-TOFs). Recent advances in FTICR MS technology, for example, the compensated dynamically harmonized ICR cell25 and the higher field Orbitrap with optimized geometry, should enable the routine detection of isotopic fine structure and even make its detection difficult to avoid.

Ultrahigh resolving power FTICR MS was employed to analyze the isotopic fine structure of a model peptide following HDX, which permitted detection of, as well as characterization of the relative abundance of, peptide isotopomers with precise number of deuterium incorporation separable from isotopic species with the same nominal mass due to the distribution of natural abundance isotopes. Such data could be collected on an LC-compatible time scale (~2 s) with commercially available technology. Specific data analysis methods were found to be required for high resolving power data and were therefore developed in order to account for resolving HDX-related isotopomers from isotopomers present from the distribution of natural abundance isotopes. It was further demonstrated that the isotopic fine structure affected peak shape in any FTICR MS instrument (commercial ICR or Orbitrap), and failure to account for this decreased the accuracy of HDX MS data analysis.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

Deuterium-enriched solvents were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA). All other solvents (HPLC grade) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Substance P was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Part number S6883).

Peptide Level HDX

Deuterated substance P was labeled at 0.2 μM concentration with 20% D2O for 10 min at 37 °C. Before data acquisition, 0.2 μM substance P in pure HPLC water was mixed 9:1 (v: v) with 0.1% FA in water and deuterated substance P was mixed 19:1 (v: v) with 0.1% FA in pure acetonitrile (ACN).

All experiments were performed on a Bruker Daltonics’ 12 T solariX FTICR mass spectrometer. After the initial tuning, calibration was performed using a 0.05 mg/mL NaTFA solution to produce a distribution of sodium bound clusters.26 Root mean square (RMS) mass error by external calibration was generally less than 0.1 ppm over m/z 430 to 1110. Samples were directly infused with a built-in syringe pump at 150 μL/h flow rate. Nebulizer gas was 1 bar and drying gas was 2.2 L/min at 180 °C. Control parameters during acquisition included the following: capillary voltage = −4500 V, source declustering potential = 34 V, source accumulation time = 0.001 s, ion accumulation time = 0.15 s, time-of-flight = 0.001 s, and sidekick extraction voltages = −1.5 V. Data was acquired using either 4 M or 64k data acquisition points with a quadrupole isolation window of m/z 20 or 30 (samples were pure and isolation was used to separate a given charge state). Unless otherwise noted, spectra were generated by averaging 16 scans.

HDX Data Processing

Both high-resolution (4 M acquisition points, 4.61 s transient length) and low-resolution (64k acquisition points, 0.07 s transient length) spectra were calibrated internally using the theoretical substance P isotopic mass (<0.1 ppm mass error) or substance P average mass (<3 ppm mass error) in DataAnalysis 4.0 (Bruker Daltonics Inc., MA). Simulated spectra were generated in DataAnalysis using “simulate pattern” function from known elemental composition, and inputs of peak width and monoisotopic peak magnitude were measured from acquired spectrum. For determining the deuterium incorporation level, low-resolution HDX data was analyzed using standard methods. Briefly, the difference of the average masses of a peptide before and after deuterium exchange were taken as the average number of deuterium incorporated.27 However, high-resolution HDX data were analyzed differently and described in detail in the Results and Discussion section.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Detection of Isotopic Fine Structure in Unlabeled Substance P

Detecting natural abundance isotopic fine structure is a prerequisite for detecting fine structure specific to deuteration. Unlabeled substance P was chosen for proof-of-concept as it is an “average-sized” sulfur containing peptide (Figure 1A), thus representing the complete array of isotopic fine structure typically found in peptides from nascent proteins (posttranslational modifications with non-C, H, O, N, and S elements, such as phosphorylation, add additional fine structure). Isotopic fine structure of natural abundance substance P was detected at resolving power ~750 000 at m/ z 674 and fitted with the theoretical spectrum (Figure 1C). In contrast, non-Fourier transform instruments currently convolute these into a single unresolved peak, which is illustrated at resolving power ~12,000 (Figure 1B). As a point of reference, heavy sulfur and carbon isotopomer peaks are separated (~ 90% valley) at resolving power ~130 000 (Δm = 11 mDa and Δ m/z = 0.005 for 2+ charge state) and 25% valley at resolving power ~250 000. The resolving power required to detect isotopic fine structure of an “average-sized” peptide is therefore within reach of Orbitrap and ICR instruments but not most commercial Q-TOFs. On the other hand, Spiral TOF from JEOL offers resolution ~60 000 at m/z 2093 (unknown resolution at low m/z) and the MaXis HD from Bruker Daltonics offers resolution of ~75 000 (m/z unspecified). They therefore have the potential to resolve isotopic fine structures of small peptides (<500 Da), which could confound the low mass portion of HDX (Q-TOF) MS. Detection of heavy N and S isotopes (Δm = 1.7 mDa and Δ m/z = 0.0009 for the 2+ charge state), one of the most closely spaced isotope pairs among the C, H, O, N, and S isotopomers, requires a resolving power of ~ 1 180 000. A handful of specialized groups, including our own, have detected isotopic fine structure of peptides and even proteins, but required considerable time of tuning, long transient times, specialized parameters, and even specialized data processing.28–30 It is therefore noteworthy that the combination of the dynamically harmonized ICR cell (trade name “ParaCell”)25 and integrated data processing methods for generating phased absorption-mode spectrum31–33 makes the acquisition of such data routine.

Figure 1.

Resolved isotopic fine structure of unlabeled substance P. Acquired spectra of nondeuterated substance P (blue traces) are plotted with simulated spectra (red traces were simulated as described in the Experimental Section) at ultrahigh resolving power (B top panel: 4 M data acquisition points with resolving power ~750 000) and low resolving power (B bottom panel: 64k data acquisition points with resolving power ~12 000). A zoom in of A + 2 profile from B top panel is shown in panel C. A total of 16 scans were averaged for this figure to demonstrate stability of the signal (no scan-to-scan alignment was required to account for frequency shifts), but isotopic fine structure was also detected in a single scan (see Figure S-1 in the Supporting Information). Elemental compositions of detected isotopic peaks are labeled in panel C. Theoretical m/z of deuterium-containing isotopic peak position is also marked to denote the negligible contribution from natural abundance deuterium.

Resolving HDX-Derived Isotopomers Using Isotopic Fine Structure

Detection of HDX-derived isotopic fine structure of substance P is shown in Figure 2. The spectra observed here are an order of magnitude more complex than those of previous studies, and the “new” peaks require a naming convention. In accord with theory, every deuteration creates what is defined here as a “Di exchangeomer peak,” which results from a particular natural abundance molecule undergoing a given number (i) H/D exchanges. This natural abundance molecule could have any number (including zero) of natural abundance heavy isotopes prior to exchange and could be indexed by its elemental formula. To simplify matters, it is suggested this index only consists of the symbol and number of heavy isotopes, such that the 34S1D4 exchangeomer represents molecules with only one heavy isotope, 34S1, undergoing four H/D exchanges. By analogy, a given number (i) deuterium adding to the entire natural abundance isotopomer distribution results in a “Di exchangeomer distribution.”

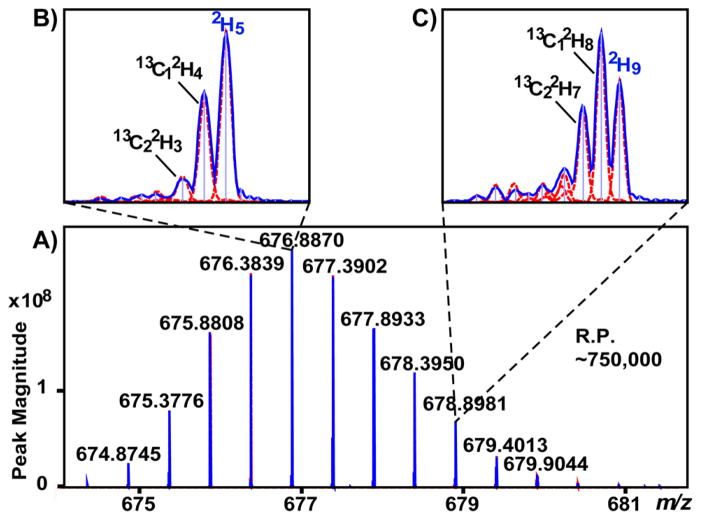

Figure 2.

Detection of isotopic fine structure following HDX: deuteration-related isotopomers of substance P. Acquired (blue trace) and simulated spectra (red traces were simulated as described in the Experimental Section) are shown for substance P incubated and introduced to the mass spectrometer in 20% D2O. This experimental design, by virtue of spraying out of deuterium oxide, eliminates back exchange. For a point of reference, this spectrum approximates a typical HDX experiment (equivalent to ~65% backbone exchanged with no side chains labeled upon detection) (A). Close-ups of isotopic fine structure in A + 5 and A + 9 profiles are shown with pseudomonoisotopic peaks labeled with blue typeface (B and C).

The term “Di pseudo-monoisotopic peak” is defined as the peak resulting from a molecule of monoisotopic mass undergoing a given number (i) H/D exchanges, such that the D2 pseudomonoisotopic peak arises from a peptide with no natural abundance heavy isotopes that incorporates two deuterons. Overlap of acquired and simulated spectra (simulation is described in Experimental Section and below) of 20% deuterated substance P is shown in Figure 2, with closeups of A + 5 and A + 9 profiles and highlighted pseudomonoisotopic peaks for D5 and D9 exchangeomer distributions (2H5 and 2H9 isotopes). As shown, the pseudomonoisotopic peaks were well resolved by 3 mDa or m/z 0.0015 (for the 2+ charge state) from 13C heavy isotopes of the previous exchangeomer distribution. There is no upper limit on the numbers of exchangeomer distributions that can be resolved within a nominal mass. For example, in a spectrum of 20% deuterated substance P, up to five exchangeomers were resolved at a nominal mass 11 Da heavier than the monoisotopic mass (Figure S-2 in the Supporting Information).

Data Analysis of Ultrahigh Resolution HDX MS

Current methods for processing HDX MS data are not directly applicable to spectra with resolved isotopic fine structure. In order to use existing data processing approaches on high resolving power data, one of two preprocessing methods was used: (1) the spectral resolving power was artificially reduced (in this case by using only 64k of experimental data in the Fourier transform). (2) The magnitude at a given nominal mass was calculated as the weighted average of the isotopomers within that nominal mass (0.5% relative magnitude cutoff). These approaches served as the standards to which the novel technique described below were compared. Using either of these preprocessing methods followed by standard analysis, the mass shifts of 20% deuterated substance P were both 5.2 Da. These existing methods require the acquisition or simulation of an unlabeled “time zero” spectrum to account for the contribution from natural abundance heavy isotopes. Notably, this is not required in the method described below.

With isotopic fine structure resolved data, it is possible to simultaneously simplify data analysis and eliminate the requirement for an unlabeled spectrum. Ironically, this remarkable increase in spectral complexity reduces the amount of processing required by increasing specificity. This was accomplished by analyzing only the pseudomonoisotopic peaks, since they encode the number of incorporated deuterium. This simplified data analysis eliminated ~80% of the detected peaks. Specifically, pseudomonoisotopic peaks were assigned with 0.5% relative magnitude threshold (Figure 3), their relative magnitudes determined, and the mass shift from deuteration was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

where i is the number of deuterons exchanged and n is the maximum number of exchanges detected. Pi is the fractional magnitude for the ith pseudomonoisotopic peak (mathematically equivalent to the probability). P0 accounts for unlabeled peptide such that if no HDX takes place, the number of exchanged deuterium will be calculated as 100% × 0 = 0. A sample calculation follows: if the fourth, fifth, and sixth pseudomonoisotopic peaks are 25%, 53%, and 22% of the total pseudomonoisotopic peak magnitude, respectively, the calculation would be (0.25 × 4) + (0.53% × 5) + (0.22 × 6) = 5.0 average exchanged deuterium. In such a manner, the average number of deuterons incorporated in 20% deuterated substance P was calculated as 5.2, consistent with the 5.2 Da result obtained above using standard methods, demonstrating the validity of using only the pseudomonoisotopic peak for data analysis. An analogous but more data intensive method using entire exchangeomer distributions (rather than pseudomonoisotopic peaks only) gave the same result (Table S-1 in the Supporting Information). The contribution of natural abundance deuterium (2 orders of magnitude less abundant than 13C) was taken as negligible. This did not detectably affect accuracy but could be accounted for at the expense of acquiring or calculating a natural abundance spectrum.

Figure 3.

Simulated isotopic fine structure of deuterated substance P using a linear combination of discrete exchangeomer distributions. Acquired (blue trace) and simulated spectra of exchangeomer distributions (red traces were simulated as described in the Experimental Section) are shown for 20% deuterated substance P. Simulated individual exchangeomer distribution is shown with corresponding elemental composition and relative abundance. Pseudomonoisotopic peaks for each exchangeomer distribution are highlighted in the dotted box.

Using Data Analysis Methods That Do Not Account for Isotopic Fine Structure Can Result in Error in Reported Deuterium Uptake

Standard data analysis methods work well (as expected) for low resolving power data, and our novel data analysis methods work well for isotopic fine structure resolved, high-resolving power HDX MS data. However, it is demonstrated below standard methods can result in errors for data with intermediate resolving power (the type of data expected from routine use of an Orbitrap or at low masses for a modern Q-TOF). These errors arise from misestimating both relative peak magnitude and m/z. Spectra of 20% deuterated substance P were simulated at resolving powers ~50 000, ~ 150 000, and ~500 000 (Figure 4A–C). Relative peak magnitudes were affected by resolving power in the following way: after normalization to the monoisotopic peak (Figure 4A), magnitude discrepancies were found to increase with m/z. For example, in the A + 3 profile, peak magnitudes differed subtly among three simulated spectra at different resolving powers (Figure 4B), but in contrast, peak magnitudes changed by ~2-fold for A + 9 profiles (Figure 4C). This effect was the result of multiple isotopomers convolving to contribute to the total magnitude in intermediate- but not high-resolving power data. This led to miscalculation of average mass and underestimation of deuterium incorporation.

Figure 4.

Previous data analysis methods applied to high resolving power data causes errors in relative magnitude and calculated deuterium incorporation. Spectrum for individual exchangeomer distribution of 20% deuterated substance P was simulated in DataAnalysis 4.0 at different resolving powers and grouped in MATLAB (MathWorks, MA). Panels A–C show simulated spectra of the monoisotopic peak, A + 3 peak, and A + 9 peak of 20% deuterated substance P at resolving powers ~50 000 (black trace), ~ 150 000 (red trace), and ~500 000 (blue trace).

A second contribution to the error in reported deuterium uptake for partially resolved HDX MS is estimation of m/z using either centroid mass analysis or local maximum. Spectra of 20% deuterated substance P were simulated at different resolving powers (~375 000, ~500 000, and ~750 000) (Figure 5A). As illustrated, well-resolved isotopic peaks gradually convoluted with a decrease in resolving power; isotopic fine structure was detected at resolving power ~750 000; a single peak of irregular shape with many peak shoulders was detected at resolving power ~500 000; at lower resolving power ~375 000, the A + 9 peak exhibited a visible side peak. If centroid mass analysis was used, this irregular peak shape may lead to error. For example, the average mass would be incorrect if the contribution of the side peak is omitted. Given that peak m/z is most often determined by local maximum, in these intermediate cases and in high resolution data, the local maximum does not always represent the average m/z (Figure 5A,B).

Figure 5.

Previous data analysis methods applied to high resolving power data causes errors in m/z and calculated deuterium incorporation. (A) Spectra for individual exchangeomer distribution of 20% deuterated substance P were simulated in DataAnalysis 4.0 at different resolving powers and grouped up in MATLAB. Simulated spectra are shown for the A + 9 peak at resolving powers ~375 000 (black trace), ~500 000 (red trace), and ~750 000 (blue trace). Red arrow points out local maximum for the A + 9 peak at resolving power ~375 000, which does not coincide with its average mass measured at resolving power ~40 000 (indicated by black arrow and dashed line). One visible side peak is observed at resolving power ~375 000, which is possibly assigned as a separate peak and not accounted for in centroid mass analysis. (B) Spectrum of A + 11 peak for 20% deuterated substance P at a resolving power ~750 000 is shown. Black arrow points out the average mass measured at resolving power ~40 000, and red arrows points to possibly assigned local maximum.

The theoretically predicted errors in m/z estimation were verified using experimental data. Spectra of 20% deuterated substance P with medium resolving power were generated by ftms Processing program (Bruker Daltonics Inc., MA) from spectrum acquired with 4 M data acquisition points. Spectrum with 256k acquisition points (resolving power is ~150 000) reported 4.5 Da of mass shift, which was different from 5.2 Da of mass shift measured in control experiments (vide supra).

CONCLUSION

It was demonstrated here that modern FTICR mass spectrometers can routinely detect isotopic fine structure, including the fine structure resulting from HDX. Data analysis methods for isotopic-fine structure resolved HDX MS data were developed and shown to obviate the need for subtracting the contribution of natural abundance isotopes, which in practice eliminated the need for analyzing a “time zero” (nondeuterated) sample. Ultrahigh resolution HDX MS could provide solutions to more challenging analyses including localization of deuteration from overlapping fragments which typically suffers from natural isotopic interference requiring the use of specialized algorithms.34 It is, however, demonstrated that failure to account for the influence of partially resolved isotopic fine structure could introduce errors into calculating the extent of deuteration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support for this work by Grant R01NS065263 from the National Institutes of Health. Also we thank Christopher Thompson for his kind help.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Additional information as noted in text. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Englander SW, Kallenbach NR. Q Rev Biophys. 1983;16:521–655. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500005217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Z, Smith DL. Protein Sci. 1993;2:522–531. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wales TE, Engen JR. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2006;25:158–170. doi: 10.1002/mas.20064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L, Pan H, Smith DL. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:132–138. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m100009-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang HM, Bou-Assaf GM, Emmett MR, Marshall AG. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2009;20:520–524. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valeja SG, Emmett MR, Marshall AG. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23:699–707. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0329-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wales TE, Fadgen KE, Gerhardt GC, Engen JR. Anal Chem. 2008;80:6815–6820. doi: 10.1021/ac8008862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rand KD, Adams CM, Zubarev RA, Jorgensen TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1341–1349. doi: 10.1021/ja076448i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan J, Han J, Borchers CH, Konermann L. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:11574–11575. doi: 10.1021/ja802871c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zehl M, Rand KD, Jensen ON, Jorgensen TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:17453–17459. doi: 10.1021/ja805573h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abzalimov RR, Kaplan DA, Easterling ML, Kaltashov IA. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2009;20:1514–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landgraf RR, Chalmers MJ, Griffin PR. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23:301–309. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0298-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woods VL, Jr, Hamuro Y. J Cell Biochem. 2001;Suppl 37:89–98. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Englander JJ, Del Mar C, Li W, Englander SW, Kim JS, Stranz DD, Hamuro Y, Woods VL., Jr Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7057–7062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232301100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hotchko M, Anand GS, Komives EA, Ten Eyck LF. Protein Sci. 2006;15:583–601. doi: 10.1110/ps.051774906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weis DD, Engen JR, Kass IJ. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2006;17:1700–1703. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nikamanon P, Pun E, Chou W, Koter MD, Gershon PD. BMC Bioinf. 2008;9:387–402. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slysz GW, Baker CA, Bozsa BM, Dang A, Percy AJ, Bennett M, Schriemer DC. BMC Bioinf. 2009;10:162–175. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreshuk A, Stankiewicz M, Lou XH, Kirchner M, Hamprecht FA, Mayer MP. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2011;302:125–131. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller DE, Prasannan CB, Villar MT, Fenton AW, Artigues A. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23:425–429. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0234-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pascal BD, Willis S, Lauer JL, Landgraf RR, West GM, Marciano D, Novick S, Goswami D, Chalmers MJ, Griffin PR. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23:1512–1521. doi: 10.1007/s13361-012-0419-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kan ZY, Mayne L, Chetty PS, Englander SW. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:1906–1915. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0236-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kazazic S, Zhang HM, Schaub TM, Emmett MR, Hendrickson CL, Blakney GT, Marshall AG. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2010;21:550–558. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong W, Yang J. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2009;23:3255–3258. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nikolaev EN, Boldin IA, Jertz R, Baykut G. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:1125–1133. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moini M, Jones BL, Rogers RM, Jiang LF. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1998;9:977–980. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katta V, Chait BT. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 1991;5:214–217. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1290050415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi SD, Hendrickson CL, Marshall AG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11532–11537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L, Kresh JA, Karabacak NM, Cobb JS, Agar JN, Hong P. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2008;19:1867–1874. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nikolaev EN, Jertz R, Grigoryev A, Baykut G. Anal Chem. 2012;84:2275–2283. doi: 10.1021/ac202804f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Comisarow MB. J Chem Phys. 1971;55:205–217. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Comisarow MB. J Chem Phys. 1978;69:4097–4104. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qi Y, Thompson CJ, Van Orden SL, O’Connor PB. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:138–147. doi: 10.1007/s13361-010-0006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abzalimov RR, Kaltashov IA. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2006;17:1543–1551. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.