Abstract

Objective

This study assessed oral health status for preschool aged children in Navajo Nation to obtain baseline decayed, missing, and filled tooth surfaces (dmfs) data and dental caries patterns, describe socio-demographic correlates of children’s baseline dmfs measures, and compare the children’s dmfs measures to previous dental survey data for Navajo Nation from Indian Health Service and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Methods

The analyzed study sample included 981 child/caregiver dyads residing in Navajo Nation who completed baseline dmfs assessments for an ongoing randomized clinical trial involving Navajo Nation Head Start Centers. Calibrated dental hygienists collected baseline dmfs data from child participants ages 3–5 years (488 males and 493 females), and caregivers completed a Basic Research Factors Questionnaire (BRFQ).

Results

Mean dmfs for the study population was 21.33 (SD =19.99) and not appreciably different from the 1999 Indian Health Service survey of Navajo Nation preschool aged children (mean=19.02, SD=16.59, p=0.08). However, 69.5 percent of children in the current study had untreated decay compared to 82.9 percent in the 1999 Indian Health Service survey (p<0.0001). Study results were considerably higher than the 16.0 percent reported for 2–4 year old children in the Whites Only group from the 1999–2004 NHANES data. Age had the strongest association with dmfs, followed by child gender, and caregivers’ income and education.

Conclusion

Dental caries in preschool aged Navajo children is extremely high compared to other US population segments and dmfs has not appreciably changed for more than a decade.

Introduction

National surveys of oral health status indicated dental caries in children ages 2 to 5 years increased between 1988–1994 and 1999–2004, and marked differences existed among ethnic groups (1). Oral disease levels in American Indian and Alaska Native children are by far the highest, suggesting disparate risk and the need for effective, culturally accepted interventions (2). A recent study reported 68.4 percent of American Indian and Alaska Native preschool children had dental caries experience, 45.8 percent had untreated dental caries, and the mean decayed, and filled teeth (dft) score of 3.5 which was 3 times higher compared to scores from their non-Native counterparts. In the Navajo Nation, dental caries among preschool children is especially severe; a recent survey reported a mean decayed, missing, and filled teeth (dmft) of 6.5 for 2–5 year olds, the highest in Indian Country. (3)

The Center for Native Oral Health Research (CNOHR) at the University of Colorado initiated a randomized clinical trial (Clinicaltrials.gov NCT01116739) in Navajo Nation Head Start Centers in 2010 to test effectiveness of a community-based intervention to reduce dental caries in young children. The intervention consisted of delivery of fluoride varnish (FV) applications to Head Start children and oral health promotion (OHP) events for children and their caregivers by specially trained native paraprofessionals designated as a Community Oral Health Specialist (COHS). The primary outcome variable was dmfs measured at baseline and then annually for a duration of 3 years. At the time of acquiring dmfs data, caregivers also completed a computerized 190-item Basic Research Factor Questionnaire (BRFQ) to assess caregivers’ dental knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and other psychosocial characteristics that may be moderators or mediators of the observed treatment effect.(4) This paper reports baseline dmfs data and patterns of dental caries, describes socio-demographic correlates of the children’s baseline dmfs measures, and compares children’s dmfs measures to previous dental Indian Health Service (IHS) survey data from Navajo Nation (2,3) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (1, 5).

Methods

Approvals

This study was approved by the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board (NNHRRB), governing bodies at tribal and local levels, the tribal departments of Head Start and Education, Head Start parent councils, and the University of Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB). The study also has ongoing oversight by National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR).

Study Design

The study design was a cluster randomized clinical trial. There were 100 Head Start Center based classrooms in the Navajo Nation, at the study inception. The Head Start Centers were first stratified on the basis of single versus multiple Head Start classrooms in each building location and by Navajo Nation Agency (5 agencies), and then randomized into intervention and control groups within those strata. Fifty-two Head Start classrooms were enrolled into the study, 26 in each treatment arm. (4)

Head Start Eligibility

Eligible participants were Head Start enrollees and their caregivers. On the Navajo Nation, Head Start eligibility is based on age and income. Children must be 36 months of age and their family income must be equal to or less than 100 percent of the federal poverty level. Children from families with incomes exceeding federal poverty guidelines can be enrolled in Navajo Nation Head Start programs after all income-eligible children have been enrolled.

Study Eligibility

All enrolled Head Start children were eligible to participate in the study. Children were American Indian or Alaska Native as defined by their tribe, or children of other race/ethnic groups who were Head Start enrollees. Children younger than age 3 years, children without a parent or legal guardian to consent and/or participate in the study or unable to understand English were excluded. Children were also excluded if allergic to any components of the FV or with health conditions or findings that, in the opinion of the investigator, would interfere with or preclude participation in the study including ulcerative gingivitis, stomatitis or other conditions resulting in chronically disrupted or irritated oral mucosa. The intervention was administered by the trained COHS over two Head Start program school years: FV was offered 4 times per school year and OHP activities provided to children 4 times per school year in the Head Start classrooms. Oral health promotion programs were offered to caregivers at specific Head Start events 3 times per school year, in addition to a parent-child kick-off event each year. Participants in the usual care arm received toothbrushes and toothpaste for all family members at enrollment.

Outcome Measures and Data Collection

The primary outcome measure was the number of decayed, missing, and filled tooth surfaces (dmfs) for each child. The dmfs data were collected by dental hygienists trained for the study and systematically calibrated to ensure consistency. Eight dental hygienists conducted study evaluations during 2011–2013. All dental hygienists completed calibration training with a gold standard examiner. Calibration training was conducted in accordance with a designated protocol and criteria used by the NIDCR and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (NHANES program studies) for examinations and scoring. Two study investigators served as gold standard examiners for calibration of the dental hygienists (the same two individuals conducted all training). Study investigators who served as gold standard examiners completed calibration training with an independent gold standard examiner (the same individual has conducted all training). Recalibration of all examiners was conducted annually. Kappa scores were calculated from a minimum of 13 dental examinations. Calibration scores were independently analyzed to determine when Kappa scores met or exceeded target thresholds; specifically, for demineralized lesions examiners had to achieve surface level kappa values of 0.40 or greater; for cavitated decayed lesions examiners required surface level kappa values of 0.75 or greater. Overall surface level kappa values for all types of decay had to be 0.70 or higher. The calibrated dental hygienists were blinded to the study condition. Dental hygienists completed visual assessment of children’s teeth to obtain dmfs at baseline, 12, 24 and 36 months. Data recording was conducted by trained study personnel using Mini laptop computers (Dell, TX, USA). The findings were recorded using anelectronic dental research-recording instrument designated as CARIN (CAries Research Instrument) specifically designed for research documentation involving dmfs/DMFS. Examinations were conducted using a headlamp (SurgiTel, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and lighted mouth mirror (Defend MirrorLite Illuminated Mouth Mirror, Hauppauge, NY, USA). Teeth to be examined were brushed for 30 seconds to remove debris, dried with gauze and systematically evaluated for presence of decayed and filled surfaces. Caries detection and measurement criteria were used to visually evaluate and score lesions (6). Non-cavitated lesions (demineralization) were not identified as decay. A cavitated lesion involving a smooth surface was defined as demonstrable loss of enamel structure, and for approximal smooth surfaces, undermining with discoloration under a marginal ridge and either direct extension onto the proximal surface, or evidence of a break in the proximal enamel surface. A cavitated lesion involving pits/fissures was defined as demonstrable loss of enamel structure upon visual examination with evidence of active decay, such as demineralization or undermining of enamel. A second outcome variable, the percentage of children with at least one untreated carious tooth surface, was reported as this outcome variable, in addition to dmfs, is often used in studies assessing oral health status. Caregivers completed a computerized 190-item BRFQ to assess their dental knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. The questionnaire also addressed other psychosocial scales as potential moderators or mediators of observed treatment effects in the trial. Caregivers were asked to complete the survey at enrollment and annually for three years. In this paper we report the results of baseline data collection.

Statistical Analyses

Basic descriptive statistics are reported for dmfs and percentage of children with at least one untreated carious tooth surface in Navajo Head Start Center enrollees, by gender and age of the child, and by income and education of the caregiver.

A mixed effects analysis was used to assess the effects of child age and gender on dmfs. An interaction term was assessed to see if the relationship between dmfs and age differed between males and females. The interaction term was not statistically significant (p>0.05) and was removed from the analysis. Head Start classrooms were treated as a random effect, in order to account for the clustering of children within each classroom. In addition, caregiver education and income were assessed as potential predictors of dmfs.

Logistic regression analysis was used to assess the simultaneous, independent association between socio-demographic predictors and children with any untreated caries. T-tests were used to compare mean dmfs in the current clinical trial compared to mean dmfs reported in the 1999 IHS survey of Navajo Nation (2) and mean dfs (decayed and filled tooth surfaces) in the current clinical trial compared to mean dfs in the 1999–2004 NHANES survey (1). Chi-square tests were used to compare the percentage of children with untreated caries in the current clinical trial compared to the same statistics in the IHS surveys of Navajo Nation reported in 1999(2) and 2010(3), and oral health surveys of all race/ethnic groups in NHANES (1,5). All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

The target sample size for the clinical trial was 1,040 child/caregiver dyads in 52 Head Start classrooms to enable detection of a 10 percent increase in the intervention group compared to a 40 percent increase in the usual care group using an expected baseline dmfs of 23 (standard deviation of 24) based upon the 1999 IHS dental survey. The target sample was also based on, an average cluster (Head Start class) size of 20, an intraclass correlation for the dmfs measure of 0.045, a statistical power of 80 percent, and a retention rate of 70 percent.

Results

A total of 1,016 child/caregiver dyads from 52 Head Start classrooms were enrolled into the clinical trial. This represents 100 percent of the enrollment goal for Head Start classrooms, and 97.6 percent of the children and caregivers goal. At baseline, the dmfs data were collected for 981 children (488 males and 493 females). Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the mean dmfs measure and the percentage of children with untreated caries, by age and gender of the children, and education and income of the caregivers. The dmfs was higher in males compared to females (23.3 vs. 19.4, p=0.005), and, as expected, older compared to younger children (37.5 at age 5 years vs. 22.9 at age 4 years vs. 18.2 at age 3 years, p<.0001). It is noteworthy that the sample size is smaller in the 5-year-old group as compared to 3 and 4-year-old groups. There was no statistically significant interaction between gender and age. The dmfs tended to decrease with increasing caregivers’ education (23.0 for < high school to 16.8 for college graduate, p=0.053) and income (24.0 for <$10,000 per year to 20.3 for ≥ $40,000 per year, p=0.012).

Table 1.

Decayed, Missing, and Filled Tooth Surfaces (dmfs) and Percentage of Untreated Decay by Child Age (years) and Gender and Caregiver Education and Income

| Category | N | Mean dmfs | SD | % With Untreated Decay |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 3 | ||||

| Male | 190 | 20.0 | 20.1 | 67.9 |

| Female | 218 | 16.7 | 18.6 | 65.6 |

| Age 4 | ||||

| Male | 281 | 24.9 | 20.3 | 74.7 |

| Female | 265 | 20.7 | 19.0 | 68.7 |

| Age 5 | ||||

| Male | 16 | 33.4 | 22.8 | 62.5 |

| Female | 9 | 44.9 | 22.7 | 77.8 |

| All Ages | ||||

| Male | 488 | 23.3 | 20.5 | 71.7 |

| Female | 493 | 19.4 | 19.3 | 67.3 |

| p=0.005 | p=0.18 | |||

| Age 3 | ||||

| Both genders | 408 | 18.2 | 19.4 | 66.7 |

| Age 4 | ||||

| Both genders | 546 | 22.9 | 19.8 | 71.8 |

| Age 5 | ||||

| Both genders | 25 | 37.5 | 23.0 | 68.0 |

| p<.0001 | p=0.34 | |||

| Caregiver Education | ||||

| < HS | 153 | 23.0 | 20.0 | 75.8 |

| HS/GED | 364 | 23.5 | 21.3 | 69.0 |

| Some college | 340 | 19.9 | 19.0 | 69.7 |

| Coll. grad. | 112 | 16.8 | 17.7 | 62.5 |

| p=0.053 | p=0.30 | |||

| Caregiver Income | ||||

| Missing | 153 | 19.7 | 18.8 | 71.9 |

| < $10K | 411 | 24.0 | 21.1 | 71.5 |

| $10K to <$20K | 169 | 22.0 | 19.7 | 69.8 |

| $20K to <$30K | 90 | 15.0 | 16.9 | 66.7 |

| $30K to <$40K | 68 | 17.3 | 17.9 | 63.2 |

| ≥ $40K | 90 | 20.3 | 20.1 | 63.3 |

| p=0.012 | p=0.80 | |||

The percentage of children with any caries experience was 89.3 percent and for untreated dental caries was 69.5 percent. There were no statistically significant associations between the percentage of children with untreated dental caries and the children’s gender or age, or the caregivers’ level of education or income (p-values ranging from 0.18 to 0.80).

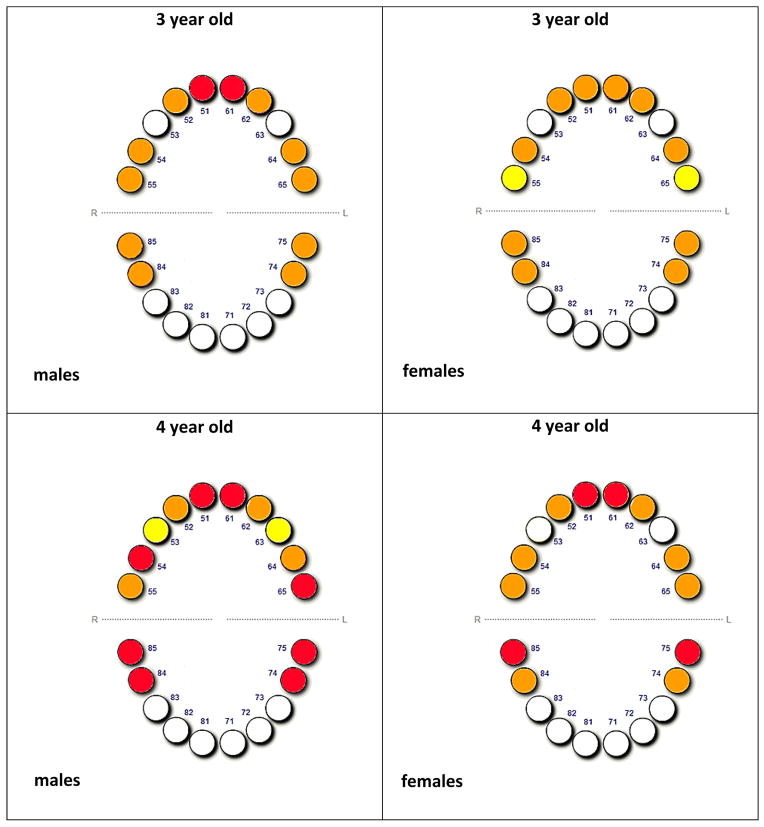

Figure 1 presents the heat maps for each primary tooth with previous or current dental caries based on gender and age. The heat maps demonstrated a high prevalence of dental caries in the maxillary central incisors and mandibular first and second molars. Moderately high levels of dental caries prevalence were found in the maxillary first and second molars and maxillary lateral incisors. The teeth with the lowest prevalence of dental caries were the maxillary canines and mandibular incisors and canines.

Figure 1.

Percentage of children with decay, past or present by primary tooth type (decay defined as ≥ 1 decayed or filled surface or having a tooth missing due to decay)

Color index: Red ≥ 60%; Orange 40–60%; Yellow 20–40%; White 0–20%

Table 2 shows the simultaneous, independent relationships between the socio-demographic predictors and baseline dmfs. Age had the strongest association (p<0.0001), followed by gender (p=0.005), caregivers’ income (p=0.01), and caregivers’ education (p=0.053). On average, 5-year-olds had 18.5 more carious surfaces than 3-year-olds and 14 more than 4-year-olds. Males had 3.5 more carious surfaces than females, children of caregivers with a less than high school education had 3.7 more carious surfaces than children of a college graduate, and children of caregivers with incomes <$10,000/year hadfrom 1.1 to 7.7 more carious surfaces than children of families with incomes >$10,000/year. It is interesting that the relationship between the increase in dmfs and the decrease in income was not monotonic.

Table 2.

Multiple Linear Regression Analysis of Associations between dmfs (outcome variable), Child Age (years) and Gender and Caregiver Education and Income

| Variable | Estimate | S.E. | P-value | Overall p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 41.56 | 4.33 | <0.0001 | |

| Age vs. 5 (ref) | <.0001 | |||

| 3 | −18.53 | 4.17 | <0.0001 | |

| 4 | −14.28 | 4.14 | 0.0006 | |

| Gender vs. Female (ref) | 0.005 | |||

| Male | 3.52 | 1.25 | 0.005 | |

| Caregiver Education vs. <HS (ref) | 0.053 | |||

| Coll. grad. | −3.67 | 2.51 | 0.14 | |

| Some college | −2.07 | 1.93 | 0.28 | |

| HS/GED | 1.27 | 1.88 | 0.50 | |

| Caregiver Income vs. <$10K (ref) | 0.01 | |||

| Missing | −3.86 | 1.89 | 0.04 | |

| ≥ $40K | −2.92 | 2.32 | 0.21 | |

| $30K to <$40K | −4.72 | 2.60 | 0.07 | |

| $20K to <$30K | −7.71 | 2.30 | 0.0008 | |

| $10K to <$20K | −1.07 | 1.79 | 0.55 | |

Table 3 presents the simultaneous, independent relationships between the socio-demographic predictors and children with untreated tooth caries. There were no statistically significant independent relationships between any of the socio-demographic predictors and children with untreated tooth decay.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Analysis of Associations for Children with Untreated Primary Tooth Decay (outcome variable), Child Age and Gender and Caregiver Education and Income

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Overall p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of Child | |||

| 3 vs. 5 (reference) | 0.93 | 0.37, 2.34 | 0.34 |

| 4 | 1.15 | 0.46, 2.87 | |

| Gender of Child | |||

| Female vs. Male (ref.) | 0.83 | 0.63, 1.09 | 0.18 |

| Caregiver Income | |||

| Missing vs. <$10K (ref.) | 1.06 | 0.69, 1.62 | 0.80 |

| ≥ $40K | 0.76 | 0.47, 1.25 | |

| $30K to <$40K | 0.75 | 0.43, 1.30 | |

| $20K to <$30K | 0.86 | 0.53, 1.42 | |

| $10K to <$20K | 0.97 | 0.65, 1.44 | |

| Caregiver Education | |||

| Coll. grad. vs. <HS (ref.) | 0.56 | 0.34, 1.04 | 0.30 |

| Some College | 0.80 | 0.51, 1.24 | |

| HS/GED | 0.73 | 0.47, 1.13 | |

Table 4 presents comparisons between the baseline oral health data in the current clinical trial and previous IHS surveys of the Navajo Nation and NHANES samples. There was no statistically significant difference between mean dmfs in the current clinical trial compared to the 1999 IHS survey in Navajo Nation (21.33 vs. 19.02, p=0.08), indicating prevalence of dental caries has not appreciably changed in Navajo Nation in the past 10–15 years. Although mean dmfs in the current clinical trial was slightly higher, the 1999 IHS survey included some 2-year old children, which the current trial did not. Inclusion of younger children may result in a comparatively lower dmfs mean due to primary teeth eruption and dental caries increasing with age. The dfs measure in the current clinical trial is 6.8 times higher than the dfs measure for all race/ethnicity groups in the national 1999–2004 NHANES Survey (17.45 vs. 2.58, p<0.0001), indicating dental caries continues to be more severe in Navajo Nation children compared to national surveys of all U.S. children. There appears to be some improvement over time in percentage of children with untreated caries between the 1999 IHS Survey and the current clinical trial (82.9 percent vs. 69.5 percent, p=0.0001). The percentage of children with untreated caries is about the same between the 2010 IHS Survey and the current clinical trial (65.8 percent vs. 69.5 percent, p=0.16), giving additional credence to both of these measures. Finally, the percentage of children with untreated caries is much higher in the current clinical trial compared to either the White Only population in the 1999–2004 NHANES national sample (69.5 percent vs. 16.04 percent, p<0.0001) or all race/ethnicity groups combined (69.5 percent vs. 20.48 percent, p<0.0001), again reflecting the severity of dental caries in Navajo Nation.

Table 4.

Comparison of Dental Caries Measures for Primary Teeth in the Current Study vs. Earlier IHS Dental Surveys in Navajo Nation and NHANES Dental Surveys in Other Populations

| Study | N | dmfs Mean (SD) |

Dmft Mean (SD) |

dfs Mean (SE) |

dft Mean (SE) |

% Children with Untreated Decay | % Caries Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 IHS Survey Navajo Nation 2–5 Year Olds |

208 | 19.02 (16.6) | 7.45 (4.9) | NA | NA | 82.9* | 90.7 (dmft>0) |

| 2010 IHS Survey Navajo Nation 2–5 Year Olds |

411 | NA | 6.52 (3.6)* | NA | NA | 65.8 | 85.9 (dmft>0) |

| NHANES, 1999–2004 All Race/Ethnic Groups 2–5 Year Olds |

2,379 | NA | NA | 2.58 (0.2)* | 1.17 (0.1)* | 20.48* | 27.9 (dft>0)* |

| NHANES, 1999–2004 Whites Only 2–4 Year Olds |

385 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 16.04* | 20.45 (dft>0)* |

|

Current Study 2011–2012 3–5 Year Olds |

981 | 21.33 (20.0) | 7.35 (5.0) | 17.45 (0.5) | 6.47 (0.1) | 69.5 |

89.3 (dmft>0) 88.69 (dft>0) |

significantly different from current study, p≤0.001

DISCUSSION

Dental Caries experience in Navajo Nation Head Start children was extremely high and mean dmfs was higher with older age of the child, male gender, and when the caregivers’ educational attainment and income were low. Mean dmfs in the study children was also 6.8 times higher than national averages for children of the same age, and their mean dmfs did not appreciably change over the last decade. The percent of children with untreated decay appears to have declined in the past decade, although it remains today substantially higher (3–4 times) than national averages. However, when comparing study data with previous surveillance studies on the Navajo Nation it is important to note the 1999 IHS data were from collected solely from children seeking care at dental units. What this means in terms of comparability of the data is unknown; children in the 1999 survey may have accessed care at a dental unit due to presence of oral disease, or may have less disease as their caregivers’ had demonstrated ability to access care at a dental unit.

Specific etiologies for disparities in dental caries are not known; however several factors including social environment, physical environment, health behaviors, and access to dental and medical care have been associated with oral health disparities (7,8). However, the high prevalence of untreated dental caries in Navajo Nation children was not associated with education or income level of their caregiver. An examination of the dental care delivery system identifies one concern. The Navajo Nation resides on the largest reservation in the U.S. at 25,000 square miles (9). There are 22 dental clinics serving 225,639 individuals (9). In Navajo Nation the dentist to population ratio is 32.3 dentists per 100,000 (10), and at the lowest end of the range for the dentist to population ratio in the U.S. by state, excluding the District of Columbia with 31.1 to 69 per 100,000 (11). The geography of the area is challenging with a dispersed population living in a vast region with lack of public transportation. Clearly, accessing dental care is often difficult, and likely contributes to oral health disparities. The percentage of children with one or more untreated carious lesions was less than the percentage reported in 1999, 82.9 percent compared to 69.5 percent, but still very high at 3.39 times that reported for all races combined in the NHANES data (5). Untreated dental caries may be related to the ability of the caregivers to access dental care for their children. Future research should be designed to test for a relationship between untreated caries and accessibility of dental services.

The Navajo Nation’s division on economic development reports 43 percent of the population lives below the poverty level; the median household income is $20,000; and 42 percent of residents are unemployed (12). Other studies have identified a relationship between poverty and poor oral health (13), and children living in poverty are most likely to be affected by dental disease (7). However, income in this study was inconsistently related to dmfs. Children with caregivers of the lowest income category (< $10,000 per year) had a mean dmfs of 24.0 and mean dmfs dropped for the next two highest income levels. However, dmfs increased to 17.3 for the $30,000–$40,000 income category and rose to 20.3 for the greater than $40,000 category. Previous studies of factors associated with dental caries of the primary dentition concluded that, even in a low income population, slightly higher income was a protective factor for dental caries (14). The rise in dmfs in the highest income groups may be related to greater financial ability to maintain dietary habits that include consumption of convenience foods high in fermentable carbohydrates.

To achieve a deeper characterization of dental caries beyond prevalence or mean surfaces, the distribution of surface-level data was evaluated using mapping based on age and gender. The pattern of dental caries in this population was found to be similar to that in other studies of preschool children in Arizona (15). In both populations, the primary maxillary anterior teeth were most frequently decayed and primary canines and mandibular anterior teeth least frequently affected. Primary maxillary teeth are generally among the first primary teeth to erupt and subject to greater exposure from dietary factors, such as prolonged exposure from a cariogenic liquid in a bottle or sippy cup. Maxillary canines are less frequently affected by dental caries due to later eruption in the sequence of primary tooth development. Involvement of primary molars in the maxillary and mandibular teeth increased with age as dental caries progressed. The severity of dental caries in 4-year-old children in this study was highest with greater than 60 percent of the children found to have carious involvement of primary incisors and molars.

Males were found to have higher dmfs scores compared to females. This finding may be related to female children having more positive oral health behaviors. Specifically, studies in the U.S. and Europe have observed that female children are more likely to brush more than once per day compared to their male counterparts. It has also been postulated that female adolescents consider oral appearance more important than males and perhaps this is a motivating factor in younger children as well.(16)

This study has several strengths; it is representative of the prevalence of dental caries in Navajo Nation, as the sample was large, a broad geographic sample of children from Navajo Nation were included in the study, and strict calibration measures were used to maintain the quality of data collected. However, the limitation of the study is the representative dmfs in preschool children does not describe dental caries experience for children of other ages. Study results are based on Head Start children who are primarily 3 and 4-year-olds, thus future approaches should emphasize the importance of establishing access to care at the earliest ages when primary teeth first erupt.

Future research is warranted to gain a deeper understanding of dental caries in the Navajo Nation population and to design interventions to improve oral health for Navajo Nation children. A three-part approach is suggested to improve oral health of Navajo Nation children: increased access to effective preventive services, culturally sensitive and effective oral health education programs, and improved access to restorative care. The current study strives to improve the first two. Improved access to restorative dental services will require innovation, financial support and political will.

Acknowledgments

The grant support for this project is National Institute of Health-National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIH-NIDCR) award number 1U54DE019259. Basic Research Factors Questionnaire (BRFQ) developed with support from: U54DE019285, U54DE019275, and U54DE019259. CARIN software developed with support from: US DHHS/NIH/NIDCR U54DE014251 and R21DE018650

References

- 1.Dye BA, Tan S, Smith V, Lewis BG, Barker LK, Thornton-Evans G, et al. Trends in oral health status: United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 11. 2007;24(8):1–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Indian Health Service. The 1999 oral health survey of American Indian and Alaska Native dental patients: findings, regional differences and national comparisons. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phipps KR, Ricks TL, Manz MC, Blahut P. Prevalence and severity of dental caries among American Indian and Alaska Native preschool children. J of Public Health Dentistry. 2012;72(3):208–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2012.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quissell DO, Bryant LL, Braun PA, Cudeii D, Johs N, Smith VL, et al. Preventing caries in preschoolers: Successful initiation of an innovative community-based clinical trial in Navajo Nation Head Start. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.01.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Dye BA, Li X, Beltran-Aguilar ED. NCHS data brief, no 96. Vol. 96. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. Selected oral health indicators in the United States, 2005–2008; pp. 1–8. NCHS Data Brief. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitts NB. Modern concepts of caries measurement. J of Dental Research. 2004;83(Special Issue C):C43. doi: 10.1177/154405910408301s09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patrick DL, Lee RSY, Nucci M, Grembowski D, Jolles CZ, Milgrom P. Reducing oral health disparities: a focus on social and cultural determinants. BMC Oral Health. 2006;6 (Suppl 1):S4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-6-S1-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher-Owens SA, Gansky SA, Platt LJ, Weintraub JA, Soobader MJ, Bramlett MD, et al. Influences on children’s oral health: A conceptual model. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3):e510–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Indian Health Service. [accessed on January 29, 2014];Navajo Area. Available from URL: http://www.ihs.gov/Navajo/

- 10.Joe G. Health care in Navajo Nation Fact sheet. [accessed January 29, 2014];Tribal Connections. 2004 Available from: URL: http://www.tribalconnections.org/health_news/secondary_features/GeorgeFactSheet.

- 11.Oral Health USAR. [accessed January 29, 2014];Dental care workforce/Cost of dental care/Accessibility of dental care. 2002 Available from: URL: http://drc.hhs.gov/report/16_5.htm.

- 12.TC [accessed January 29, 2014];An overview of the Navajo Nation – Demographics Facts. 2000 Available from: URL: http://www.navajobusiness.com/fastFacts/demographics.htm.

- 13.Çolak H, Dülgergil ÇT, Dalli M, Hamidi MM. Early childhood caries update: A review of causes, diagnoses, and treatments. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2013 Jan;4(1):29–38. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.107257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finlayson TL, Siefert K, Ismail AI, Sohn W. Psychosocial factors and early childhood caries among low-income African–American children in Detroit. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35(6):439–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Psoter WJ, Pendrys DG, Morse DE, Zhang H, Mayne ST. Associations of ethnicity/race and socioeconomic status with early childhood caries patterns. J of Public Health Dentistry. 2006;66(1):23–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2006.tb02547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poutanen R, Lahti S, Tolvanen M, Hausen H. Gender differences in child-related and parent-related determinants of oral health-related lifestyle among 11 to 12 year old Finnish School children. Acta Odont Scandinavia. 2007;65(4):194–200. doi: 10.1080/00016350701308356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]