Abstract

Few studies have examined changes in functional connectivity after long-term aerobic exercise. We examined the effects of 4 weeks of forced running wheel exercise on the resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) of motor circuits of rats subjected to bilateral 6-hydroxydopamine lesion of the dorsal striatum. Our results showed substantial similarity between lesion-induced changes in rsFC in the rats and alterations in rsFC reported in Parkinson’s disease subjects, including disconnection of the dorsolateral striatum. Exercise in lesioned rats resulted in: (a) normalization of many of the lesion-induced alterations in rsFC, including reintegration of the dorsolateral striatum into the motor network; (b) emergence of the ventrolateral striatum as a new broadly connected network hub; (c) increased rsFC among the motor cortex, motor thalamus, basal ganglia, and cerebellum. Our results showed for the first time that long-term exercise training partially reversed lesion-induced alterations in rsFC of the motor circuits, and in addition enhanced functional connectivity in specific motor pathways in the Parkinsonian rats, which could underlie recovery in motor functions observed in these rats.

Keywords: Exercise, motor training, brain mapping, plasticity, Parkinson’s disease, basal ganglia, limbic system

1. Introduction

Exercise training is widely used for the rehabilitation of patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) primarily based on clinical evidence of improvement in motor functions following exercise training (Goodwin, et al., 2008). Research using animal models has shed light on exercise-induced neuroplasticity as a candidate mechanism for the neurorehabilitative effects (Petzinger, et al., 2013). Currently, a knowledge gap exists between molecular/cellular neuroplasticity data and changes at the behavioral level in motor functions. Research on motor circuits at the network level may serve to bridge this gap.

Recent findings from functional brain mapping and functional (including effective) connectivity analysis of brain circuits have advanced our understanding of the neuropathology of PD at the network level (Hacker, et al., 2012, Helmich, et al., 2010, Luo, et al., 2014, Palmer, et al., 2009, Wu, et al., 2011). Many of these studies applied resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) to characterize PD-related alterations in resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) of the brain, with complex alterations reported in the striatum, subthalamic nucleus, supplemental motor area, prefrontal cortex, sensorimotor areas, thalamus, and cerebellum (Baudrexel, et al., 2011, Hacker, et al., 2012, Helmich, et al., 2010, Kwak, et al., 2010, Luo, et al., 2014, Sharman, et al., 2013, Wu, et al., 2011). Graph theoretical analysis has further revealed that PD is associated with a decrease in network efficiency, suggesting functional disconnection (Gottlich, et al., 2013, Skidmore, et al., 2011).

Aerobic exercise has been shown to induce functional plasticity in the rsFC in the aging brain (Voss, et al., 2010), while motor learning has been shown to enhance inter-regional connectivity in motor circuits (Ma, et al., 2010). In patients with cerebrovascular stroke, motor training results in rsFC changes in association with movement recovery (Varkuti, et al., 2013). Yet, little is known regarding how physical exercise modulates rsFC of the motor circuits in PD, with only a single study published to date on rsFC changes in PD subject following a one hour training on an exercise bicycle (Beall, et al., 2013). The present study aimed to characterize alterations in rsFC in an intra-striatal 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) lesion rat model of Parkinsonism, and to delineate the effects of long-term, aerobic exercise training on rsFC, with a focus on the motor circuits. To our best knowledge, this is the first study to describe the effects of long-term aerobic exercise on functional connectivity of motor circuits in the dopaminergically deafferented brain.

We recently demonstrated in a rat model of 6-OHDA-induced Parkinsonism that 4 weeks of forced running wheel exercise improved motor deficits and resulted in altered regional brain activation (Wang, et al., 2013), including the motor cortex, caudate putamen, globus pallidus, zona incerta, and cerebellum. Our earlier study presented histochemical, behavioral, and regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) findings. Since individual voxels were treated as independent functional units, rCBF results did not provide direct information at the network level. We now examined the effects exercise had on rsFC within the basal ganglia-thalamocortical, as well as the cerebellar-thalamocortical circuits. Results revealed findings not apparent in our earlier publication and discerned only by means of the correlation-based rsFC analysis. This included evidence that dopamergic deafferentation resulted in (a) a loss of rsFC of anterior secondary motor cortex and of dorsolateral striatum with the motor cortices; (b) a remapping of corticostriatal connectivity involving anterior and ventrolateral striatum, with the emergence of mid and posterior motor cortex as new cortical network hubs; and (c) the functional recruitment of the deep cerebellar nuclei and cerebellar hemispheres into the motor network, as well as a recruitment of the basal ganglia and zona incerta, largely through new negative correlations with motor cortex. Exercise-related compensatory changes included (a) exercise-dependent strengthening of rsFC within the motor thalamic nuclei; (b) the emergence with exercise of the ventrolateral striatum as a new network hub; and (c) exercise-dependent strengthening of rsFC between the cerebellum, the motor thalamic nuclei and the motor cortex.

2. Methods

2.1 Animal model

The experimental protocol has been previously reported and the reader is referred to our publication for additional details (Wang, et al., 2013). This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Southern California. In brief, 3-month old, male Sprague-Dawley rats were randomized into the following groups: Lesion/Exercise (n = 12), Lesion/No-Exercise (n = 10), and Sham/No-Exercise (n = 9). Rats received stereotaxic injection of the dopaminergic toxin 6-OHDA (10 μg in 2 μL of 1% L-ascorbic acid/saline, Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) at four injection sites targeting the dorsal caudate putamen bilaterally (AP: +0.6, ML: ±2.7, DV: −5.1 mm, and AP: −0.4, ML: ±3.5, DV: −5.5 mm), which resulted in ~40% of bilateral striatal volume affected, as well as a ~20–38% loss in tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) optical density at the level of the striatum and substantia nigra compacta, measured by immunohistochemical staining 7 weeks after the lesion. Sham-lesioned rats received 4 injections of an equal volume of vehicle. To prevent noradrenergic effects of the toxin, rats received desipramine (25 mg/kg in 2 mL/kg bodyweight saline, i.p., Sigma-Aldrich Co.) before the start of surgery. Two weeks after the lesioning, animals assigned to the exercise group were trained in a running wheel (diameter = 35.6 cm, Lafayette Instrument, Lafayette, IN, USA) for 20 min/day (4 sessions, 5 min each with 2-min inter-session intervals), 5 consecutive days/week. No-exercise animals were handled and left in a stationary running wheel for 30 min/day. Animals were trained for 4 weeks using an individually adjusted, performance-based speed adaptation paradigm as described (Wang, et al., 2013). Thereafter rats received implantation of the right external jugular vein cannula that was externalized dorsally in the suprascapular region. Brain mapping studies occurred 4 days postoperatively.

2.2 Brain Mapping

All animals were habituated to the experimental arena (single lane of a stationary horizontal treadmill) for 4 days. On the day of the perfusion experiment, rats while resting on the treadmill received a bolus intravenous administration of [14C]-iodoantipyrine (125 μCi/kg in 300 μL of 0.9% saline, American Radiolabelled Chemicals, St. Louis, MO, USA) followed immediately by the euthanasia agent (pentobarbital 50 mg/mL, 3 M potassium chloride). This resulted in cardiac arrest within ~ 10 s, a precipitous fall of arterial blood pressure, termination of brain perfusion, and death. This approach uniquely allowed a 3-dimensional (3D) assessment of functional activation in the awake, unrestrained animal, with a temporal resolution of ~ 10 s and an in-plane spatial resolution of 100 μm2. Olfactory cues were minimized by wiping the treadmill with a 1% ammonia solution. Brains were removed, flash frozen at −55 °C in methylbutane on dry ice and serially sectioned for autoradiography (57 coronal 20-μm thick slices, 300-μm interslice distance, beginning at 4.8 mm anterior to bregma). Autoradiographic images of brain slices were digitized on an 8-bit gray scale. Cerebral blood flow (CBF) related tissue radioactivity was measured by the classic [14C]-iodoantipyrine method (Goldman and Sapirstein, 1973, Sakurada, et al., 1978).

2.3 Three-dimensional brain reconstruction

3D reconstruction of each animal’s brain was conducted using 57 serial coronal sections (voxel size 40 × 300 × 40 μm) using TurboReg, an automated pixel-based registration algorithm implemented in ImageJ (version 1.35, http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). This algorithm registered each section sequentially to the previous section using a nonwarping geometric model that included rotations and translations and nearest-neighbor interpolation. All brains were spatially normalized to a template brain as previously described (Nguyen, et al., 2004). Spatial normalization consisted of applying a 12-parameter affine transformation followed by a nonlinear spatial normalization using 3D discrete cosine transforms. Voxels for each brain failing to reach a specified threshold in optical density (70% of the mean voxel value) were masked out to eliminate the background and ventricular spaces. To account for any global differences in the absolute amount of radiotracer delivered to the brain, adjustments were made by the SPM software in each animal by scaling the voxel intensities so that the mean intensity for each brain was the same (proportional scaling). Prior work has demonstrated that 6-OHDA striatal lesions in rats result in no significant difference in absolute cerebral blood flow (mL/g/min) (Dahlgren, et al., 1981, Lindvall, et al., 1981).

2.4 Pairwise interregional correlation analysis

The current resting-state functional connectivity analysis was based on data from 3 of the 6 groups we reported earlier, with subjects and tissue sections being identical (Wang, et al., 2013). We applied inter-regional correlation analysis to investigate rsFC (Wang, et al., 2012). Anatomical regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn manually in MRIcro (version 1.40, http://cnl.web.arizona.edu/mricro.htm) for each hemisphere of the template brain according to the rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 2007). A total of 21 anatomic ROIs were selected, representing the basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuit, the cerebellar-thalamocortical circuit, as defined in Fig. 1. Primary and secondary motor cortex were divided into anterior, mid, and posterior regions, where ‘anterior’ was defined at the level of the first appearance of the forceps minor (~ 3.7 mm anterior to the bregma), ‘mid’ was defined at the level of the first appearance of the caudate putamen (~ 2.7 mm anterior to the bregma), and ‘posterior’ was defined at the level of the genu of the corpus callosum (~ 2.2 mm anterior to the bregma). Mean optical density of each functional ROI was extracted for each animal using the Marsbar toolbox in SPM (version 0.42, http://marsbar.sourceforge.net/). Optical densities of homologous ROIs were averaged across hemispheres. An inter-regional correlation matrix was calculated across animals for each group in Matlab (version 6.5.1, The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). The matrices were visualized as heatmaps with Z-scores of Pearson’s correlation coefficients color-coded. Statistical significance of between-group difference of a correlation coefficient was evaluated using the Fisher’s Z-transform test (P < 0.05).

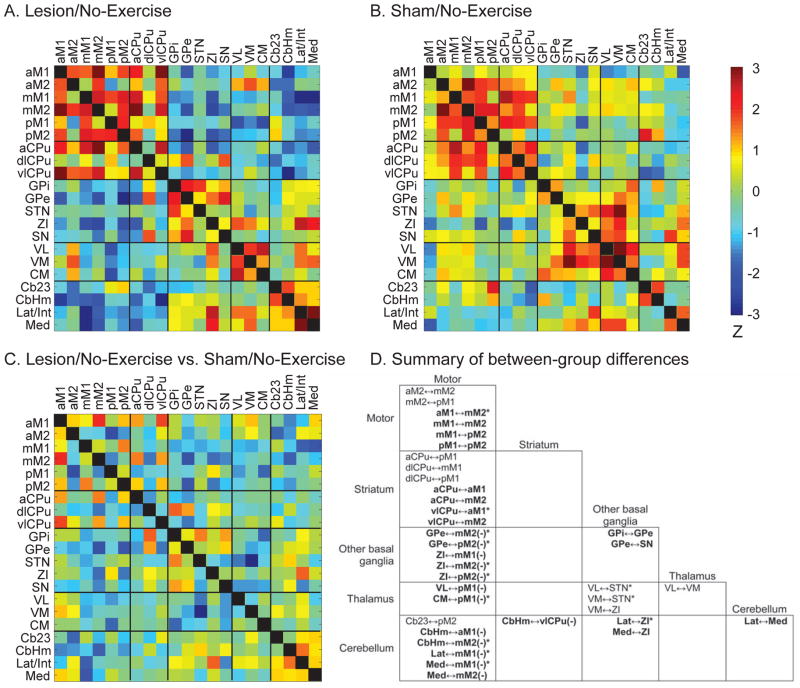

Figure 1. Effects of lesion on resting-state functional connectivity of the motor regions.

Resting-state functional connectivity was evaluated with inter-regional correlation matrices. Z-scores of Pearson’s correlation coefficients are color-coded for the Lesion/No-Exercise (A) and Sham/No-Exercise (B) group. The matrices are symmetric across the black diagonal line from upper left to lower right. Significant correlations (P < 0.05) are marked with white dots. (C) Group comparison. The matrix of Fisher’s Z-statistics represents differences in Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) between the Lesion/No-Exercise versus the Sham/No-Exercise group. Positive Z values indicate greater r in the Lesion group, while negative Z values indicate smaller r. Significant between-group differences (P < 0.05) are marked with white dots. (D) Summary of between-group differences. Significant connections that existed in the Lesion but not the Sham group are marked with bold characters, whereas significant connections showing in the Sham but not the Lesion group are printed in regular characters. Minus signs in parentheses (−) denote negative correlations, while the default is positive. *: significant between-group difference (P < 0.05). Abbreviations: aCPu, anterior caudate putamen; aM1, anterior primary motor cortex; aM2, anterior secondary motor cortex; Cb23, cerebellar vermis, lobules 2 and 3; CbHm, cerebellar hemisphere; CM, central medial thalamic nucleus; dlCPu, dorsolateral caudate putamen; GPe, external globus pallidus; GPi, internal globus pallidus; Lat/Int, lateral and interposed cerebellar nuclei; Med, medial cerebellar nucleus; mM1, mid primary motor cortex; mM2, mid secondary motor cortex; pM1, posterior primary motor cortex; pM2, posterior secondary motor cortex; SN, substantia nigra; STN, subthalamic nucleus; VL, ventrolateral thalamic nucleus; vlCPu, ventrolateral caudate putamen; VM ventromedial thalamic nucleus; ZI, zona incerta.

2.5 Graph theoretical analysis

The analysis was performed on networks defined by the above correlation matrices in the Pajek software (version 3.12, http://vlado.fmf.uni-lj.si/pub/networks/Pajek/) (de Nooy, et al., 2005). Each ROI was represented by a vertex (node) in a graph, and two vertices with statistically significant correlation (positive or negative) were linked with an edge. A Kamada-Kawai algorithm (Kamada and Kawai, 1988) was implemented to arrange the graph such that strongly connected regions were placed closer to each other, while weakly connected regions were placed further apart. Absolute values of correlation coefficients were used for the strength of connection. We calculate degree centrality to identify network hubs. The degree of a node was defined as the number of edges linking it to the rest of the network.

3. Results

3.1 Effects of bilateral striatal lesions on the rsFC of motor circuits (Lesion/No-Exercise vs. Sham/No-Exercise)

Pairwise inter-regional correlation matrices are displayed as heatmaps (Fig. 1A, 1B), with between-group differences of the correlation coefficients evaluated using the Fisher’s Z-transform test (Fig. 1C) and summarized in Fig. 1D. Significant differences in correlation coefficients are interpreted as significant changes in rsFC only when the connection is significant in at least one group. In cases where the connection is significant in one group but not the other, yet the difference does not reach statistical significance, the result is interpreted as a trend of changes in rsFC.

The Sham/No-Exercise group showed 14 significant connections, all of which were positive. Lesion increased the total number of connections to 30, 17 of which were positive and 13 negative. Four connections were preserved across groups: between mid and posterior secondary motor cortex (mM2↔pM2), between anterior and ventrolateral caudate putamen (aCPu↔vlCPu), between central medial and ventrolateral thalamic nuclei (CM↔VL), and between aCPu and mid primary motor cortex (aCPu↔mM1). Lesion caused substantial changes in rsFC, primarily involving the motor cortices and their connections to the basal ganglia, motor thalamic nuclei and cerebellum. In the Lesion/No-Exercise group, compared to the Sham group, 10 connections were lost, while 26 new connections emerged.

In lesioned animals, connections were lost among the motor cortices, between the striatum and motor cortices, between the motor cortices and cerebellum, and between the motor thalamic nuclei and basal ganglia. The mM2 lost its connection with the anterior secondary motor cortex (aM2↔mM2) and with the posterior primary motor cortex (mM2↔pM1). Dorsolateral caudate putamen (dlCPu) lost its connection with mM1 and pM1 (dlCPu↔mM1, dlCPu↔pM1). Also lost was the connection aCPu↔pM1. The subthalamic nucleus (STN) lost its connection with VL (VL↔STN) and with ventromedial thalamic nucleus (VM↔STN). VM lost its connection with the zona incerta (VM↔ZI), while the cerebellar vermis, lobules 2 and 3 lost its connection with pM2 (Cb23↔pM2). For convenience of discussion, ZI is included in the basal ganglia category.

In lesioned rats, new positive connections emerged mainly between the striatum and motor cortices, and among the motor cortices, including between aCPu and anterior primary motor cortex (aCPu↔aM1), aCPu↔mM2, vlCPu↔aM1, vlCPu↔mM2, aM1↔mM2, mM1↔mM2, mM1↔pM2, pM1↔pM2. Positive connections also emerged between external globus pallidus and substantia nigra (GPe↔SN), between GPe and internal globus pallidus (GPi↔GPe), between ZI and lateral and interposed cerebellar nuclei (Lat/Int↔ZI), between ZI and medial cerebellar nucleus (Med↔ZI), and between cerebellar deep nuclei Lat/Int↔Med.

New negative connections emerged in the lesioned rats mainly between the motor cortices and basal ganglia, and between the motor cortices and cerebellum, including GPe↔mM2, GPe↔pM2, ZI↔mM1, ZI↔mM2, ZI↔pM2, between cerebellar hemisphere and aM1 (CbHm↔aM1), CbHm↔mM2, Lat/Int↔mM1, Med↔mM1, and Med↔mM2. Negative connections also emerged in VL↔pM1, CM↔pM1, and CbHm↔vlCPu.

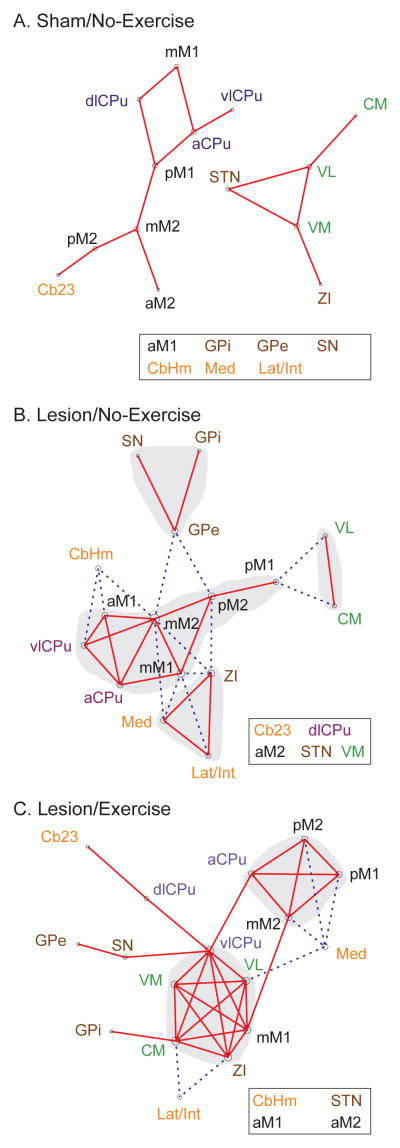

Graph theoretical analysis of the rsFC motor network of the Sham/No-Exercise group (Fig. 2A) revealed two separate networks, one consisting of motor cortical and striatal areas, with the other consisting of motor thalamic nuclei, STN, and ZI. There were no particular network hubs. In the Lesion/No-Exercise group (Fig. 2B), new connections emerged to form a single motor network. In the meantime, dlCPu, STN, VM, aM2, and Cb23 were disconnected from the network. Within the network, some motor cortical areas (aM1, mM2, mM1, pM2) and striatal areas (aCPu, vlCPu) formed a corticostriatal core through extensive, positive connections. Basal ganglia (GPi, GPe, SN) and cerebellar areas (CbHm, Lat/Int, Med) were recruited into the motor network, forming negative connections with the corticostriatal core. Network hubs with high degrees included mM2 (degree = 9), mM1 (6), pM2 (5), and ZI (5).

Figure 2. Graph theoretical analysis of the effects of lesion and exercise on the motor network.

(A) Sham/No-Exercise group. (B) Lesion/No-Exercise group. (C) Lesion/Exercise group. Each functional connectivity network is represented with a graph, in which nodes (vertices) represent regions of interest (ROIs) and edges represent significant correlations. Solid red lines denote significant positive correlations, whereas dashed blue lines significant negative correlations. Each graph was energized using the Kamada–Kawai algorithm that placed strongly correlated nodes closer to each other while keeping weakly correlated nodes further apart. The size of each node (in area) is proportional to its degree centrality, a measurement of the number of connections linking the node to other nodes in the network. ROIs with the highest degree are considered hubs of the network. Nodes and their labels are color-coded to facilitate identification of nodes belonging to the same structure. Disconnected ROIs are listed in the boxes. Shaded areas are manually drawn to highlight clusters. See Fig. 1 legends for abbreviations.

3.2 Effects of exercise training on rsFC of motor circuits in lesioned rats (Lesion/Exercise vs. Lesion/No-Exercise)

The inter-regional correlation matrix for the Lesion/Exercise group is displayed as a heatmap (Fig. 3A), with between-group differences of the correlation coefficients evaluated using the Fisher’s Z-transform test (P < 0.05, Fig. 3C) and summarized in Fig. 3D. The correlation matrix for the Lesion/No-Exercise group is reproduced in Fig. 3B to facilitate visual comparison.

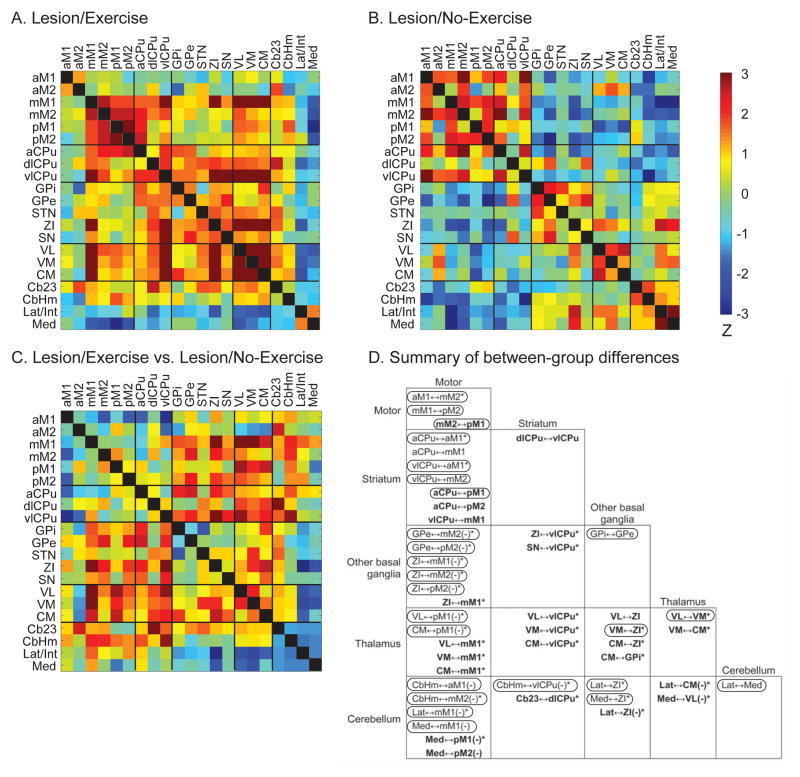

Figure 3. Effects of exercise on resting-state functional connectivity of the motor regions in lesioned rats.

Resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) was evaluated with inter-regional correlation matrices. Z-scores of Pearson’s correlation coefficients are color-coded for the Lesion/Exercise (A) and Lesion/No-Exercise (B) group. The matrices are symmetric across the black diagonal line from upper left to lower right. Significant correlations (P < 0.05) are marked with white dots. (C) Group comparison. The matrix of Fisher’s Z-statistics represents differences in Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) between the Lesion/Exercise versus the Lesion/No-Exercise group. Positive Z values indicate greater r in the Exercise group, while negative Z values indicate smaller r. Significant between-group differences (P < 0.05) are marked with white dots. (D) Summary of between-group differences. Significant connections that existed in the Exercise but not the No-Exercise group are marked with bold characters, whereas significant connections showing in the No-Exercise but not the Exercise group are printed in regular characters. The circled connections showed normalization in rsFC following exercise, i.e., a reversal of lesion-induced changes in rsFC. Minus signs in parentheses (−) denote negative correlations, while the default is positive. *: significant between-group difference (P < 0.05). See Fig. 1 legends for abbreviations.

The Lesion/Exercise group showed 34 connections, 28 of which were positive and 6 negative. It had 8 common connections with the Lesion/No-Exercise group (mM1↔mM2, mM2↔pM2. pM1↔pM2, aCPu↔mM2, aCPu↔vlCPu, GPe↔SN, VL↔CM, Med↔mM2), and 7 common connections with the Sham/No-Exercise group (mM2↔pM1, mM2↔pM2, aCPu↔pM1, aCPu↔vlCPu, VM↔ZI, VL↔VM, VL↔CM).

Remarkably, exercise reversed many of the lesion-induced changes in rsFC of the motor circuits. Of the 26 new connections in the Lesion/No-Exercise group (compared to the Sham/No-Exercise group), 21 were reversed following exercise. Of the 9 connections lost after lesioning, 4 were recovered following exercise (circled connections in Fig. 3D).

In addition, 17 new positive and 5 new negative connections emerged in the Lesion/Exercise group compared to the Lesion/No-Exercise group. New positive connections emerged in the striatum, including aCPu↔pM2, Cb23↔dlCPu, and new connections of vlCPu with mM1, dlCPu, ZI, SN, VL, VM, and CM. The thalamic nuclei (VL, VM, CM) showed new positive connections with mM1 and ZI, in addition to CM↔GPi and VM↔CM. The cerebellum showed new negative connections, including Med↔pM1, Med↔pM2, Med↔VL, Lat/Int↔ZI, and Lat/Int↔CM.

Graph theoretical analysis of the Lesion/Exercise group (Fig. 2C) showed that dlCPu and VM, formerly disconnected from the functional motor network as a result of lesioning, were reintegrated into the network. The thalamic nuclei (VM, VL, CM), vlCPu, mM1, and ZI formed a new strongly interconnected cluster. Network hubs included vlCPu (degree = 8), VL (6), CM (6), mM1 (6), and ZI (6).

4. Discussion

We applied correlation-based functional connectivity analysis to delineate effects of lesion and exercise training on the resting-state functional connectivity of motor circuits in the 6-OHDA rat model of Parkinsonism. Resting-state functional brain mapping was performed in awake, nonrestrained rats using the [14C]-iodoantipyrine autoradiographic perfusion method. Our results showed that 4 weeks of running-wheel exercise partially normalized lesion-induced disruption of the rsFC motor network, and strengthened rsFC in the basal ganglia-thalamocortical and cerebellar-thalamocortical circuit.

4.1 Lesion effects on rsFC (Lesion/No-Exercise vs. Sham/No-Exercise)

Lesion induced widespread alterations in the rsFC among motor areas. The dorsolateral caudate putamen, anterior secondary motor cortex, subthalamic nucleus, and ventrolateral thalamic nucleus were disconnected from the motor network. In addition, lesions induced new positive connections, resulting in a strongly interconnected corticostriatal cluster. Furthermore, part of the basal ganglia (internal and external globus pallidus, substantia nigra), cerebellum (hemisphere, medial, lateral/interposed nuclei), and zona incerta were recruited into the motor network and were linked to the corticostriatal core through newly emerged negative connections.

4.1.1 Basal ganglia

Lesions of the dorsal caudate putamen caused a loss of rsFC between the dorsolateral caudate putamen and primary motor cortex (loss of dlCPu↔mM1, dlCPu↔pM1), resulting in the removal of dlCPu from the motor network (Fig. 2B). Also lost was the connection aCPu↔pM1. At the same time, anterior and ventrolateral caudate putamen showed new connections with the motor cortices (aCPu↔aM1, aCPu↔mM2, vlCPu↔aM1, vlCPu↔mM2). Resting-state fMRI studies have reported in PD patients both decreases (Hacker, et al., 2012, Helmich, et al., 2010, Luo, et al., 2014, Sharman, et al., 2013, Wu, et al., 2011) and increases (Helmich, et al., 2010, Kwak, et al., 2010, Sharman, et al., 2013) in striatal rsFC, particularly with the sensorimotor cortical areas. Helmich et al. reported a shift in corticostriatal connections in PD patients from the posterior putamen, the striatal region most affected by dopamine depletion, toward the anterior putamen, a relatively spared region (Helmich, et al., 2010). Our findings suggest that similar remapping of corticostriatal connectivtiy may exist in the rat model. While the immediate lesioned dorsolateral striatal site was functionally disconnected, there was recruitment of the ventrolateral and anterior striatal regions, reflecting a putative, compensatory mechanism.

4.1.2 Motor cortices and motor thalamus

Lesion caused the most striking changes in the rsFC of the motor cortices. The anterior secondary motor cortex was disconnected from the network in the lesioned compared to sham-lesioned rats. This anterior-most motor cortex in the rodent has been proposed to be the equivalent of the supplementary motor area (SMA) in primates (Neafsey, et al., 1986, Rouiller, et al., 1993). It has been proposed that the SMA plays a role in postural stabilization, internally generated movements, bimanual coordination, and the planning of movement sequences. In human PD subjects, decreased activity in the SMA has been postulated to be a consequence of insufficient striato-thalamocortical facilitation and to contribute to akinesia (DeLong, 1990).

Lesioned compared to sham-lesioned rats showed a strong trend of increased positive rsFC in the corticostriatal network, including significantly increased positive rsFC of the anterior primary motor cortex with mid secondary motor cortex (aM1↔mM2), and with vlCPu (vlCPu↔aM1). In the meantime, new negative rsFC emerged between the motor cortices and the external globus pallidus, zona incerta, thalamus (ventrolateral and central medial nuclei), and the cerebellum (hemisphere, lateral/interposed and medial nuclei). Graph theoretical analysis (Fig. 2B) revealed a corticostriatal network linked together by positive connections. Mid and posterior secondary motor cortices emerged as new network hubs. In general, these results parallel reports of decreased rsFC in SMA and increased rsFC in sensorimotor cortices in PD subjects (Esposito, et al., 2013, Wu, et al., 2009).

4.1.3 Cerebellum

Graph theoretical analysis revealed that lesions resulted in changes in rsFC of the deep cerebellar nuclei (medial, lateral/interposed) and cerebellar hemisphere, with new significant negative connections to the mid primary and secondary motor cortices. Our findings in the cerebellum are in general agreement with what has been reported in human PD subjects (Wu and Hallett, 2013). A number of studies have suggested that disease-related impairment of the basal ganglia-thalamocortical motor circuit results in a compensatory recruitment of the cerebellum (Appel-Cresswell, et al., 2010, Cao, et al., 2011, Liu, et al., 2013, Palmer, et al., 2010), with the cerebellum being proposed as a potential therapeutic site for transcranial magnetic stimulation (Koch, et al., 2009). Cerebellar recruitment occurs not only during motor tasks but also at rest (Wu, et al., 2009).

4.2 Exercise effects on rsFC in lesioned rats (Lesion/Exercise vs Lesion/No-Exercise)

In lesioned animals, 4 weeks of aerobic exercise, compared to no-exercise, induced widespread and significant changes in the motor circuits. Remarkably, exercise reversed many of the lesion-induced alterations in rsFC, normalizing rsFC in 25 of 35 pathways affected by the lesion. Exercise also caused reintegration of the dorsolateral caudate putamen into the motor network, as well as strengthening of rsFC of the motor thalamus. A new core emerged consisting of the motor thalamic nuclei (CM, VM, VL), ventrolateral caudate putamen, mid M1, and zona incerta.

4.2.1 Basal ganglia

Inter-regional correlation analysis (Fig. 3) revealed that exercise resulted in reintegration of the dorsolateral caudate putamen into the motor network through the ventrolateral caudate putamen, as well as altered rsFC of the adjacent striatal regions (anterior, ventrolateral) with the motor cortices. Graph theoretical analysis (Fig. 2C) emphasized the emergence of the vlCPu as a network hub, with broad connections with other areas of the striatum (aCPu, dlCPu), mid primary motor cortex, motor thalamic nuclei (VM, VL, CM), substantia nigra, and zona incerta. Long-term treadmill exercise has been shown to partly restore the level of dopamine D2 receptor binding in the striatum in early PD patients (Fisher, et al., 2013). In 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced Parkinsonian mice treadmill running similarly increases D2 receptor binding (Vuckovic, et al., 2010) and reverses dendritic spine loss (Toy, et al., 2014) in the dorsolateral striatum. Treadmill exercise in rats has also been shown to increase the expression of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA)-type glutamate receptor subunits, synapsin I, synaptophysin, and neurofilaments in the striatum (Garcia, et al., 2012, Real, et al., 2010). Such exercise-induced neuroplasticity may contribute to the reintegration of dlCPu and increased functional connectivity of aCPu and vlCPu. It has been reported in human subjects that brief motor skill training involving signing with the non-dominant hand results in an increase in gray matter in the contralateral ventral striatum, as well as increases in its functional connectivity with motor cortices (Hamzei, et al., 2012). Similarly in the current study, since an element of skill is involved in the acquisition of learning the running-wheel task, this may have partially contributed to the increase in rsFC of the vlCPu.

4.2.2 Motor cortices and motor thalamus

Exercise in lesioned rats resulted in striking changes in the rsFC of the motor cortices and thalamic nuclei. In particular, lesion-induced negative correlations of the motor cortices with the external globus pallidus, zona incerta, and cerebellar hemisphere were removed following exercise. Graph theoretical analysis revealed that mid primary motor cortex and the motor thalamic nuclei (VL, VM, CM) showed robust positive connections with each other and with the vlCPu and zona incerta. These regions formed a cluster in the motor network, which interacted with the corticostriatal cluster and other basal ganglia regions (Fig. 2C). In exercised animals, the mM1 and vlCPu functioned as connector hubs connecting the motor-thalamic cluster and the corticostriatal cluster. An increased rsFC of the motor cortex has been reported in normal volunteers following several minutes of (McNamara, et al., 2007, Sun, et al., 2007) or 4 weeks of motor training (Ma, et al., 2010). Consistent with these human findings of neuroplasticity, rat models have suggested exercise-dependent synaptogenesis. Here treadmill training results in an increase in the expression of AMPA receptor subunit, synapsin I, and synaptophysin in the motor cortices (Garcia, et al., 2012, Real, et al., 2010), as well as in an increase in synaptophysin expression in the ventromedial thalamic nucleus (Ding, et al., 2002).

4.2.3 Cerebellum

Exercise reversed 8 of 9 cerebellar functional connections that emerged as a result of striatal lesioning. New negative connections appeared linking deep cerebellar nuclei (medial, lateral, interposed) to the mid and posterior motor cortices, zona incerta, and motor thalamic nuclei (central medial, ventrolateral). In addition, exercise resulted in a positive connection between the cerebellar vermis and dorsolateral caudate putamen, resulting in reintegration of the cerebellar vermis that had been disconnected from the motor network following lesion. Exercise-induced angiogenesis has been well documented in the cerebellar cortex in rats (Black, et al., 1990, Isaacs, et al., 1992). Treadmill exercise has also been reported to induce in the cerebellar cortex increases in the expression of AMPA receptor subunits, synapsin I, neurofilaments, and microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) (Garcia, et al., 2012, Real, et al., 2010). It remains to be investigated whether exercise causes similar plasticity in the deep cerebellar nuclei, which showed altered rsFC following exercise here. Our findings suggest that while lesioned rats compared to sham-lesioned rats demonstrated new negative correlations between motor cortex and the deep cerebellar nuclei, exercise resulted in an overall strengthened rsFC within the cerebellar-thalamocortical circuit.

4.3 Translational aspects

Rodents and primates show remarkable parallels in the anatomy and function of motor circuits (Hardman, et al., 2002, Jahn, et al., 2008, Smeets and Gonzalez, 2000). This general cross-species similarity constitutes the foundation for translational research applying neuroimaging methods to the understanding of functional brain organization in health and disease. The 6-OHDA basal ganglia injury rat model is a widely accepted model of dopaminergic deafferentation, and while not capturing all aspects of human PD, parallels the human disorder remarkably well (Cenci, et al., 2002). Results of our study in the 6-OHDA rat model showed a substantial similarity with reports of rsFC changes in PD subjects imaged at rest. We found functional dysconnection of the dorsolateral caudate putamen and anterior secondary motor cortex. Motor cortical regions showed compensatory increases in rsFC to vlCPu, with compensatory negative rsFC to the globus pallidus, zona incerta, motor thalamus and cerebellum.

Our findings on the effects of exercise on resting-state functional connectivity of the motor circuits in the Parkinsonian rats extended current understanding on the neurorehabilitative effects of motor training in PD. Exercise in lesioned rats normalized rsFC in many of the motor pathways altered by lesioning, and resulted in reintegration of the dorsolateral caudate putamen into the motor network. Exercise also enhanced rsFC in the basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuit, in particular, rsFC of the motor thalamic nuclei. In addition, ventrolateral caudate putamen emerged as a network hub, with broad connections with other areas of the striatum, motor thalamic nuclei, mid primary motor cortex, and zona incerta. These exercise-induced changes in rsFC were accompanied by a reduction in motor deficits in the lesioned animals as previously reported (Wang, et al., 2013).

It is generally accepted that Parkinsonian motor signs in human subjects appear when dopaminergic neuronal death exceeds a critical threshold, 60 – 80% of SNc perikarya and approximately 30–50% of striatal nerve terminals (Damier, et al., 1999, Greffard, et al., 2006, Hilker, et al., 2005, Jankovic, 2005, Kordower, et al., 2013), though estimates of the threshold level vary widely, likely because inter-individual variability is high. In the nonhuman primate, reductions of as little as 14–23% of nigral neuron counts are sufficient to induce mild parkinsonism (Tabbal, et al., 2012). The TH loss in the dorsal striatum and SN in our study was milder than the extent of TH loss typically noted in human PD subjects. Little is known about the optimal timing or type of exercise. As such, it remains unclear whether exercise as a disease modifying intervention is most relevant in presymptomatic and early PD, at a time when patients can still optimally engage in vigorous motor training. In the animal model, the degree of neuroprotection and neurorecovery is dependent upon how early exercise is started in the course of the disease. (Farley, et al., 2008, Tillerson, et al., 2002, Tillerson, et al., 2001). Indirect evidence suggests that a history of exercise in early life may reduce risk for PD. (Chen, et al., 2005, Sasco, et al., 1992) This suggests a need for regular activity to commence before or at the time of diagnosis to provide optimum results, with the promise that early physical training interventions may actually halt or slow the progression of the disease. (Farley, et al., 2008, Kleim, et al., 2003, Smith and Zigmond, 2003). Indeed, work suggests that exercise in early Parkinson’s disease can elevate striatal dopamine D2 receptor binding potential and normalize corticomotor excitability (Fisher, et al., 2013, Fisher, et al., 2008). Furthermore, a recent study by Park et al. reported a greater efficacy for early versus delayed exercise intervention with regards to depressive symptoms, though not for ratings on the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) (Park, et al., 2014). Our animal model was more relevant to early stage than late stage PD. Whether more extensive dopaminergic lesion would qualitatively change the effects of lesion and exercise on resting-state functional connectivity of the motor circuits remains to be determined. The pathways identified here as showing exercise-induced changes in rsFC may serve as a roadmap for future studies aimed at delineating neuroplasticity as a result of exercise in PD and its animal models.

Highlights.

We examined cerebral functional connectivity (FC) in the exercised Parkinsonian rat

Exercise partially reversed lesion-induced alterations in FC of the motor circuits

Running wheel exercise strengthened FC in the basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuit

Exercise facilitated the emergence of the ventrolateral striatum as a new network hub

Exercise strengthened FC in the cerebellar-thalamocortical circuit

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a United States National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) grant 1R01HD060630. The authors thank Drs. Michael W. Jakowec and Raina D. Pang for their comments regarding this study.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Appel-Cresswell S, de la Fuente-Fernandez R, Galley S, McKeown MJ. Imaging of compensatory mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23(4):407–12. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32833b6019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudrexel S, Witte T, Seifried C, von Wegner F, Beissner F, Klein JC, Steinmetz H, Deichmann R, Roeper J, Hilker R. Resting state fMRI reveals increased subthalamic nucleus-motor cortex connectivity in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroimage. 2011;55(4):1728–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall EB, Lowe MJ, Alberts JL, Frankemolle AM, Thota AK, Shah C, Phillips MD. The effect of forced-exercise therapy for Parkinson’s disease on motor cortex functional connectivity. Brain Connect. 2013;3(2):190–8. doi: 10.1089/brain.2012.0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JE, Isaacs KR, Anderson BJ, Alcantara AA, Greenough WT. Learning causes synaptogenesis, whereas motor activity causes angiogenesis, in cerebellar cortex of adult rats. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87(14):5568–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Xu X, Zhao Y, Long D, Zhang M. Altered brain activation and connectivity in early Parkinson disease tactile perception. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(10):1969–74. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenci MA, Whishaw IQ, Schallert T. Animal models of neurological deficits: how relevant is the rat? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3(7):574–9. doi: 10.1038/nrn877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Zhang SM, Schwarzschild MA, Hernan MA, Ascherio A. Physical activity and the risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2005;64(4):664–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000151960.28687.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren N, Lindvall O, Nobin A, Stenevi U. Cerebral circulatory response to hypercapnia: effects of lesions of central dopaminergic and serotoninergic neuron systems. Brain Res. 1981;230(1–2):221–33. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90403-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damier P, Hirsch EC, Agid Y, Graybiel AM. The substantia nigra of the human brain. II. Patterns of loss of dopamine-containing neurons in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 1999;122 ( Pt 8):1437–48. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.8.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Nooy W, Mrvar A, Batagelj V. Exploratory social network analysis with Pajek. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- DeLong MR. Primate models of movement disorders of basal ganglia origin. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13(7):281–5. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90110-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Li J, Lai Q, Azam S, Rafols JA, Diaz FG. Functional improvement after motor training is correlated with synaptic plasticity in rat thalamus. Neurological research. 2002;24(8):829–36. doi: 10.1179/016164102101200816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito F, Tessitore A, Giordano A, De Micco R, Paccone A, Conforti R, Pignataro G, Annunziato L, Tedeschi G. Rhythm-specific modulation of the sensorimotor network in drug-naive patients with Parkinson’s disease by levodopa. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 3):710–25. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley BG, Fox CM, Ramig LO, McFarland D. Intensive amplitude-specific therapeutic approaches for Parkinson disease: Toward a neuroplasticity-principled rehabilitation model. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 2008;24(2):99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BE, Li Q, Nacca A, Salem GJ, Song J, Yip J, Hui JS, Jakowec MW, Petzinger GM. Treadmill exercise elevates striatal dopamine D2 receptor binding potential in patients with early Parkinson’s disease. Neuroreport. 2013;24(10):509–14. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328361dc13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BE, Wu AD, Salem GJ, Song J, Lin CH, Yip J, Cen S, Gordon J, Jakowec M, Petzinger G. The effect of exercise training in improving motor performance and corticomotor excitability in people with early Parkinson’s disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(7):1221–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia PC, Real CC, Ferreira AF, Alouche SR, Britto LR, Pires RS. Different protocols of physical exercise produce different effects on synaptic and structural proteins in motor areas of the rat brain. Brain Res. 2012;1456:36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman H, Sapirstein LA. Brain blood flow in the conscious and anesthetized rat. Am J Physiol. 1973;224(1):122–6. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.224.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin VA, Richards SH, Taylor RS, Taylor AH, Campbell JL. The effectiveness of exercise interventions for people with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2008;23(5):631–40. doi: 10.1002/mds.21922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlich M, Munte TF, Heldmann M, Kasten M, Hagenah J, Kramer UM. Altered resting state brain networks in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greffard S, Verny M, Bonnet AM, Beinis JY, Gallinari C, Meaume S, Piette F, Hauw JJ, Duyckaerts C. Motor score of the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale as a good predictor of Lewy body-associated neuronal loss in the substantia nigra. Archives of neurology. 2006;63(4):584–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.4.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker CD, Perlmutter JS, Criswell SR, Ances BM, Snyder AZ. Resting state functional connectivity of the striatum in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 12):3699–711. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamzei F, Glauche V, Schwarzwald R, May A. Dynamic gray matter changes within cortex and striatum after short motor skill training are associated with their increased functional interaction. Neuroimage. 2012;59(4):3364–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardman CD, Henderson JM, Finkelstein DI, Horne MK, Paxinos G, Halliday GM. Comparison of the basal ganglia in rats, marmosets, macaques, baboons, and humans: volume and neuronal number for the output, internal relay, and striatal modulating nuclei. J Comp Neurol. 2002;445(3):238–55. doi: 10.1002/cne.10165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmich RC, Derikx LC, Bakker M, Scheeringa R, Bloem BR, Toni I. Spatial remapping of cortico-striatal connectivity in Parkinson’s disease. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20(5):1175–86. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilker R, Schweitzer K, Coburger S, Ghaemi M, Weisenbach S, Jacobs AH, Rudolf J, Herholz K, Heiss WD. Nonlinear progression of Parkinson disease as determined by serial positron emission tomographic imaging of striatal fluorodopa F 18 activity. Archives of neurology. 2005;62(3):378–82. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs KR, Anderson BJ, Alcantara AA, Black JE, Greenough WT. Exercise and the brain: angiogenesis in the adult rat cerebellum after vigorous physical activity and motor skill learning. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1992;12(1):110–9. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn K, Deutschlander A, Stephan T, Kalla R, Hufner K, Wagner J, Strupp M, Brandt T. Supraspinal locomotor control in quadrupeds and humans. Prog Brain Res. 2008;171:353–62. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00652-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankovic J. Progression of Parkinson disease: are we making progress in charting the course? Archives of neurology. 2005;62(3):351–2. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada T, Kawai S. An algorithm for drawing general undirected graphs. Information Processing Letters. 1988;31:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kleim JA, Jones TA, Schallert T. Motor enrichment and the induction of plasticity before or after brain injury. Neurochemical research. 2003;28(11):1757–69. doi: 10.1023/a:1026025408742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch G, Brusa L, Carrillo F, Lo Gerfo E, Torriero S, Oliveri M, Mir P, Caltagirone C, Stanzione P. Cerebellar magnetic stimulation decreases levodopa-induced dyskinesias in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2009;73(2):113–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ad5387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordower JH, Olanow CW, Dodiya HB, Chu Y, Beach TG, Adler CH, Halliday GM, Bartus RT. Disease duration and the integrity of the nigrostriatal system in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 8):2419–31. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak Y, Peltier S, Bohnen NI, Muller ML, Dayalu P, Seidler RD. Altered resting state cortico-striatal connectivity in mild to moderate stage Parkinson’s disease. Front Syst Neurosci. 2010;4:143. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindvall O, Ingvar M, Stenevi U. Effects of methamphetamine on blood flow in the caudate-putamen after lesions of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic bundle in the rat. Brain Res. 1981;211(1):211–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Edmiston EK, Fan G, Xu K, Zhao B, Shang X, Wang F. Altered resting-state functional connectivity of the dentate nucleus in Parkinson’s disease. Psychiatry Res. 2013;211(1):64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C, Song W, Chen Q, Zheng Z, Chen K, Cao B, Yang J, Li J, Huang X, Gong Q, Shang HF. Reduced functional connectivity in early-stage drug-naive Parkinson’s disease: a resting-state fMRI study. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(2):431–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Wang B, Narayana S, Hazeltine E, Chen X, Robin DA, Fox PT, Xiong J. Changes in regional activity are accompanied with changes in inter-regional connectivity during 4 weeks motor learning. Brain Res. 2010;1318:64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara A, Tegenthoff M, Dinse H, Buchel C, Binkofski F, Ragert P. Increased functional connectivity is crucial for learning novel muscle synergies. Neuroimage. 2007;35(3):1211–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neafsey EJ, Bold EL, Haas G, Hurley-Gius KM, Quirk G, Sievert CF, Terreberry RR. The organization of the rat motor cortex: a microstimulation mapping study. Brain Res. 1986;396(1):77–96. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(86)80191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen PT, Holschneider DP, Maarek JM, Yang J, Mandelkern MA. Statistical parametric mapping applied to an autoradiographic study of cerebral activation during treadmill walking in rats. Neuroimage. 2004;23(1):252–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer SJ, Eigenraam L, Hoque T, McCaig RG, Troiano A, McKeown MJ. Levodopa-sensitive, dynamic changes in effective connectivity during simultaneous movements in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience. 2009;158(2):693–704. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer SJ, Li J, Wang ZJ, McKeown MJ. Joint amplitude and connectivity compensatory mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience. 2010;166(4):1110–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park A, Zid D, Russell J, Malone A, Rendon A, Wehr A, Li X. Effects of a formal exercise program on Parkinson’s disease: a pilot study using a delayed start design. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20(1):106–11. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotatic coordinates. 6. Elsevier Academic Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Petzinger GM, Fisher BE, McEwen S, Beeler JA, Walsh JP, Jakowec MW. Exercise-enhanced neuroplasticity targeting motor and cognitive circuitry in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(7):716–26. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70123-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Real CC, Ferreira AF, Hernandes MS, Britto LR, Pires RS. Exercise-induced plasticity of AMPA-type glutamate receptor subunits in the rat brain. Brain Res. 2010;1363:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouiller EM, Moret V, Liang F. Comparison of the connectional properties of the two forelimb areas of the rat sensorimotor cortex: support for the presence of a premotor or supplementary motor cortical area. Somatosens Mot Res. 1993;10(3):269–89. doi: 10.3109/08990229309028837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurada O, Kennedy C, Jehle J, Brown JD, Carbin GL, Sokoloff L. Measurement of local cerebral blood flow with iodo [14C] antipyrine. Am J Physiol. 1978;234(1):H59–66. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1978.234.1.H59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasco AJ, Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Gendre I, Wing AL. The role of physical exercise in the occurrence of Parkinson’s disease. Archives of neurology. 1992;49(4):360–5. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530280040020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharman M, Valabregue R, Perlbarg V, Marrakchi-Kacem L, Vidailhet M, Benali H, Brice A, Lehericy S. Parkinson’s disease patients show reduced cortical-subcortical sensorimotor connectivity. Mov Disord. 2013;28(4):447–54. doi: 10.1002/mds.25255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skidmore F, Korenkevych D, Liu Y, He G, Bullmore E, Pardalos PM. Connectivity brain networks based on wavelet correlation analysis in Parkinson fMRI data. Neurosci Lett. 2011;499(1):47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeets WJ, Gonzalez A. Catecholamine systems in the brain of vertebrates: new perspectives through a comparative approach. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;33(2–3):308–79. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AD, Zigmond MJ. Can the brain be protected through exercise? Lessons from an animal model of parkinsonism. Experimental neurology. 2003;184(1):31–9. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun FT, Miller LM, Rao AA, D’Esposito M. Functional connectivity of cortical networks involved in bimanual motor sequence learning. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17(5):1227–34. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabbal SD, Tian L, Karimi M, Brown CA, Loftin SK, Perlmutter JS. Low nigrostriatal reserve for motor parkinsonism in nonhuman primates. Experimental neurology. 2012;237(2):355–62. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillerson JL, Cohen AD, Caudle WM, Zigmond MJ, Schallert T, Miller GW. Forced nonuse in unilateral parkinsonian rats exacerbates injury. J Neurosci. 2002;22(15):6790–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06790.2002. 20026651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillerson JL, Cohen AD, Philhower J, Miller GW, Zigmond MJ, Schallert T. Forced limb-use effects on the behavioral and neurochemical effects of 6-hydroxydopamine. J Neurosci. 2001;21(12):4427–35. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04427.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toy WA, Petzinger GM, Leyshon BJ, Akopian GK, Walsh JP, Hoffman MV, Vuckovic MG, Jakowec MW. Treadmill exercise reverses dendritic spine loss in direct and indirect striatal medium spiny neurons in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiology of disease. 2014;63:201–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varkuti B, Guan C, Pan Y, Phua KS, Ang KK, Kuah CW, Chua K, Ang BT, Birbaumer N, Sitaram R. Resting state changes in functional connectivity correlate with movement recovery for BCI and robot-assisted upper-extremity training after stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2013;27(1):53–62. doi: 10.1177/1545968312445910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss MW, Prakash RS, Erickson KI, Basak C, Chaddock L, Kim JS, Alves H, Heo S, Szabo AN, White SM, Wojcicki TR, Mailey EL, Gothe N, Olson EA, McAuley E, Kramer AF. Plasticity of brain networks in a randomized intervention trial of exercise training in older adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010;2 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2010.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuckovic MG, Li Q, Fisher B, Nacca A, Leahy RM, Walsh JP, Mukherjee J, Williams C, Jakowec MW, Petzinger GM. Exercise elevates dopamine D2 receptor in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease: in vivo imaging with [(1)(8)F]fallypride. Mov Disord. 2010;25(16):2777–84. doi: 10.1002/mds.23407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Myers KG, Guo Y, Ocampo MA, Pang RD, Jakowec MW, Holschneider DP. Functional reorganization of motor and limbic circuits after exercise training in a rat model of bilateral parkinsonism. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e80058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Pang RD, Hernandez M, Ocampo MA, Holschneider DP. Anxiolytic-like effect of pregabalin on unconditioned fear in the rat: an autoradiographic brain perfusion mapping and functional connectivity study. Neuroimage. 2012;59(4):4168–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Hallett M. The cerebellum in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 3):696–709. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Long X, Wang L, Hallett M, Zang Y, Li K, Chan P. Functional connectivity of cortical motor areas in the resting state in Parkinson’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp. 2011;32(9):1443–57. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Wang L, Chen Y, Zhao C, Li K, Chan P. Changes of functional connectivity of the motor network in the resting state in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2009;460(1):6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]