Summary

Falls in the elderly are a public health problem. Consequences of falls are increased risk of hospitalization, which results in an increase in health care costs. It is estimated that 33% of individuals older than 65 years undergoes falls. Causes of falls can be distinguished in intrinsic and extrinsic predisposing conditions. The intrinsic causes can be divided into age-related physiological changes and pathological predisposing conditions. The age-related physiological changes are sight disorders, hearing disorders, alterations in the Central Nervous System, balance deficits, musculoskeletal alterations. The pathological conditions can be Neurological, Cardiovascular, Endocrine, Psychiatric, Iatrogenic. Extrinsic causes of falling are environmental factors such as obstacles, inadequate footwear. The treatment of falls must be multidimensional and multidisciplinary. The best instrument in evaluating elderly at risk is Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA). CGA allows better management resulting in reduced costs. The treatment should be primarily preventive acting on extrinsic causes; then treatment of chronic and acute diseases. Rehabilitation is fundamental, in order to improve residual capacity, motor skills, postural control, recovery of strength. There are two main types of exercises: aerobic and muscular strength training. Education of patient is a key-point, in particular through the Back School. In conclusion falls in the elderly are presented as a “geriatric syndrome”; through a multidimensional assessment, an integrated treatment and a rehabilitation program is possible to improve quality of life in elderly.

Keywords: falls, elderly, multidimensional assessment, comprehensive geriatric assessment

Introduction

Falls are defined as the sudden, involuntary transfer of body to the ground and at a lower level than the previous one (1). Falls are responsible for considerable morbidity, immobility, and mortality among older persons: so falls in the elderly are considered as a major public health problem (2). Serious consequences of falls are an increased risk of hospitalization and institutionalization, with prolonged recovery periods, which results in an increase in health care costs (3). Falls result from an interaction of multiple and diverse risk factors and situation. This interaction is modified by age, disease and the by environment. Proper management of this health problem has strong clinical and economical relevance (4): fundamentals are therefore an appropriate assessment of the elderly at risk of falling and an effective treatment after the traumatic event.

Epidemiology

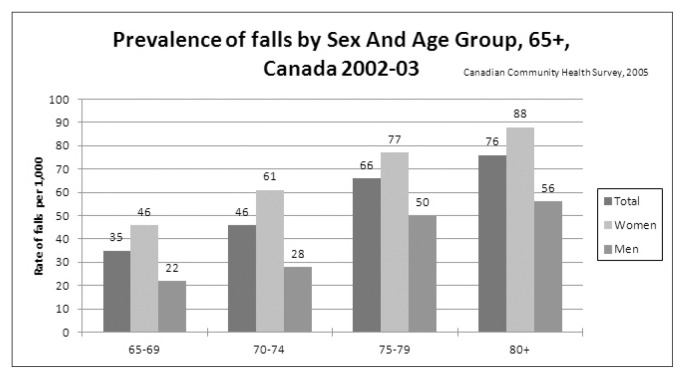

It is estimated that 33% of individuals older than 65 years undergoes falls, with 50% of subjects falling more than once in a year (5, 6) (Figure 1). The rates also depending on the setting: the falls at home are estimated at 0.3–1.6/person/year ; in Nursing Home (RSA in Italy) 0.6 to 3.6/bed/year; in the hospital 1–4/person/bed/year (7). The falls are the most common cause of traumatic injury and the leading cause of death secondary to traumatic injuries in people over the age of 65. The mortality related to falls is age-dependent, increasing from 50/100000 to 65 and reaching 150 and 5,252/100,000 respectively to 75 and 85 years (8). Unintentional injuries are the fifth cause of death in older adults (after cardiovascular disease, cancer, stroke and pulmonary disorders) and falls constitute two-thirds of these deaths. About three-fourths of deaths due to falls occur in the 13% of the population age ≥65. About 40% of this group will fall at least once each year, and about 1 in 40 of them will be hospitalized. Only about half of those admitted to hospital will be alive a year later. The most frequent complications of falls fractures of the femur (2% of cases), fractures of the humerus, wrist and pelvis (5%), head trauma, intracranial hematomas and injury of internal organs (10%) (9).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of falls by Sex and Age Groups, Canada 2002–03 (adapted from Report on seniors fall in Canada. Public Health Agency of Canada, 2005).

Etiopatogenesis

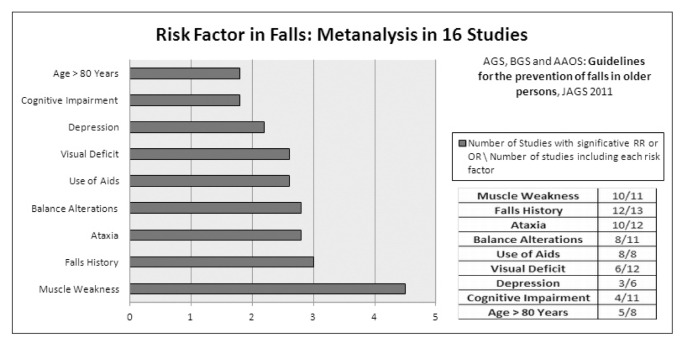

At etiological level causes of falls can be distinguished in intrinsic predisposing conditions (due to the subject) and extrinsic predisposing conditions (due to the environment). The intrinsic causes can be divided into age-related physiological changes and pathological predisposing conditions. Among the age-related physiological changes can be distinguished sight alterations (reduction in visual acuity, especially in night; reduced ability to accommodate; presbyopia; deficit in discriminative capacity for colors; reduced tolerance to glare; reduced discriminative capacity for colors); hearing alterations (reduced discrimination capability between sounds at different frequency and distance; reduced discrimination capability between contemporary voices in conversation; r; reduced perception of pure tones); alterations in the Central Nervous System (deficient tactile sensitivity, vibration sense, thermal sensitivity; increase in postural sway with instability; alterations in the integration of sensory inputs and motor responses causing increased time of reaction; vestibular and balance deficits); alterations in the musculoskeletal system (sarcopenia; reduced muscle strength mainly involving anti-gravity muscles ; reduced range of motion) (Table 1). The pathological conditions that predispose to falls can be neurological (stroke and its outcome; TIA; Parkinsonism; Dementia; Epilepsy; carotid sinus hypersensitivity syndrome), Cardiovascular (Myocardial Infarction; orthostatic hypotension; arrhythmias); Endocrine\Metabolic (Hypothyroidism; hypoglycemia; anemia), Gastrointestinal (bleeding; diarrhea; post-prandial syncope), Genito- Urinary (post-micturition syncope; urinary incontinence), Musculoskeletal (degenerative arthropathies; myopathies), Psychiatric (Depression; Anxiety) (10) (Table 2). Extremely important in this context are the falls due to iatrogenic causes: the intake of 4 or more drugs (in particular antihypertensives, diuretics, benzodiazepines, antidepressants) is considered an independent risk factor of fall (11). An additional risk factor is represented by the psychological alterations related to the fall: fear of falling and the post-fall anxiety syndrome result in loss of self-confidence and selfimposed functional limitations in both home-living and institutionalized elderly persons who have fallen (12); fear of falling is considered an independent risk factor (13). Extrinsic causes of falling are environmental factors such as obstacles, inadequate ambient lighting, inadequate footwear and clothing, uneven or slippery floors, presence of steps, lack of handrails, inadequate height of beds, inadequate chairs, inadequate bathroom, unfamiliar environment (9). Individuals with at least 4 of these risk factors have a 69% increased chance to reach out a fall than the general population (14) (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Age-related physiological changes.

Sight:

|

Table 2.

Falls predisposing conditions (adapted from Rubenstein LZ: Falls in older people, epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention; Age Ageing, 2006).

Cardiovascular

|

Internal Medicine and Endocrine

|

Neurological

|

Musculoskeletal

|

Gastrointestinal

|

Psychiatric

|

Genitourinary

|

Iatrogenic

|

Figure 2.

Risk factor in falls: metanalysis in 16 studies (adapted from American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: Guidelines for the prevention of falls in older persons. Journal of American Geriatric Society. 2001;49(5):664–72).

Assessment and clinical evaluation

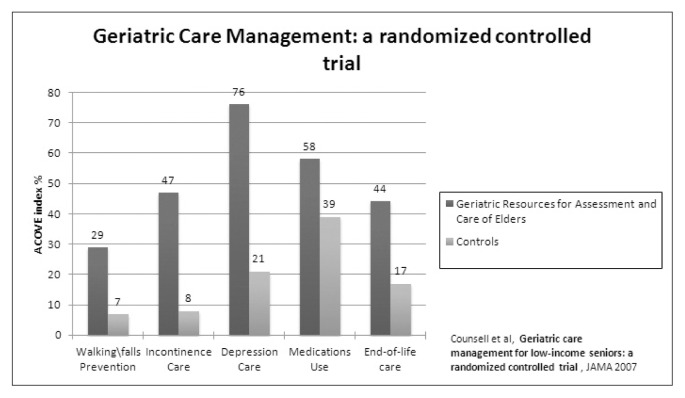

Given the multiplicity of causes and triggers the framing and the treatment must be multidimensional and multidisciplinary, involving various professionals in the health sector. The best instrument in evaluating elderly at risk for falling is the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA). The CGA is defined as a multidisciplinary evaluation in which are identified and described the multiple problems of an elderly individual; are defined its functional capacity; are defined its needs for support services; will develop a plan of treatment and care, in which the various actions are commensurate with the needs and problems (15). The objective of CGA are to increase the diagnostic accuracy, to guide the choice of appropriate interventions to restore or to preserve the best health conditions as possible, to ensure optimal environmental conditions for the care, to formulate a prognosis, to monitoring clinical changes. The CGA is possible with the intervention of a Multidisciplinary Team, including physician specialized in Geriatrics, Internal Medicine, Cardiology, Orthopedics, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Neurology, Endocrinology; General Practitioners; professional figures like Nurse, Physical Therapist, Speech Therapist, Occupational Therapist, Psychologist, Engineer, Biomedical, Geneticist. Several studies demonstrates the efficacy of a CGA respect to conventional treatment, due to a global evaluation and a specific treatment (16) (Figure 3); CGA also allows better management of health interventions resulting in reduced costs (17). The evaluation must begin with a careful anamnesis in order to evaluate the acute and chronic conditions of patient and the levels of motor autonomy. Pharmacologic anamnesis has a relevant value in order to evaluate possible interactions between drugs and their side effects. Then the circumstances of the fall must be investigate: when, where and how the patient is dropped; any warning sign or symptom coexisting. The evaluation continues with physical examination, with particular attention to the evaluation of vision, gait and balance; general condition, neurological evaluation (cognitive status, muscle strength, peripheral nerves, proprioception, reflexes, cortical function, extrapyramidal and cerebellar function), assessment of cardiovascular system (heart rate and rhythm, PA and FC in the upright position and, if appropriate, after stimulation of the carotid sinus), assessment of pain with VAS scale, evaluating muscle strength with Medical Research Council Scale. Then functional ability must be analyze using specific evaluation scale such as Berg Balance Scale (in order to evaluate static and dynamic balance), Timed Up and Go Test (to assess patient’s mobility), Falls Efficacy Scale (to assess the fear of falling) (18). Functional evaluation could be integrated (when possible) with scale like 6 minutes Walking Test and 10 meters Walking test. The instrumental assessment integrates the clinical evaluation, allowing a more accurate diagnosis; however in the elderly the use of instrumental tests must be exclusively aimed at completing the clinical suspicion and thoroughly evaluated by the Multidisciplinary team. This helps to avoid unnecessary tests in frail patients and better management of healthcare resources.

Figure 3.

Geriatric care management: quality of medical care (adapted from Counsell SR, et al. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of American Medical Association. 2007;298:2623–33).

Treatment

The treatment of falls should be primarily preventive acting on extrinsic causes: removal of architectural barriers, management of lighting environment (uniform illumination, switches visible and appropriate), adaptation of stairs, furniture, kitchen, bathroom. Other preventive actions are the control of PA and of the other cardiovascular disease risk factor. Fundamental is then the treatment of chronic and acute diseases. Therefore another objective is the reduction in the number of drugs, so a global evaluation is a key-event: the appropriateness of pharmacological prescription in older complex patients should be evaluated carefully, translating the recommendations of clinical guidelines to patients with a limited life expectancy, functional and cognitive impairment (19). Another objective of treatment is improving residual capacity. In this context appropriate rehabilitative care is fundamental, in order to improve posture control and muscle strength. Another main task is neuromotor rehabilitation, through education of the patient and the care giver (20). In rehabilitation the goal is the improvement of basic motor skills, postural control, recovery of strength and mobility of the lower limbs and education in the march and passages of position. Group and home-based exercise programs and home safety interventions reduce rate of falls and risk of falling (21). There are two main types of exercises: aerobic exercises and muscular strength training. The objective of aerobic exercises is improving cardiovascular capacity and functionality. Improving muscular strength take to a better physical function in terms of improved balance and walking speed (22). Both strength training and aerobic training may affect bone mineral density, glucose homeostasis and the risk of falling. Strength training improves muscle mass, strength and muscle quality, while aerobic training mainly affects cardio-vascular fitness, blood pressure and plasma lipoprotein (23). Exercise interventions may be effective in preventing, delaying, or reversing the frailty process (24). A systematic review on the effects of more general physical exercise programs in institutionalized elderly indicated a strong positive effect on muscle strength and mobility, gait, disability, balance and endurance (22). There is also evidence regarding beneficial exercise effects on sleep and overall well-being (25). Another goal in rehabilitation is represented by the protection of vertebral column. This is accomplished through the exercises of Overload Protection: a rehabilitation path aimed to protection of the column trough an improvement in the strength of the antigravity muscles and stabilizers, a recovery of motility in extension of the spine and a conditioning cognitive face to electively search positions which encourage the less possible the spine involvement (26). These treatments may be associated with postural exercises to the control of the spine and respiratory gymnastic exercises, in order to improve the spinal proprioception. Education of patient is also a key-point, in particular learning program in management of an ergonomic column set according to a cognitive-behavioral approach: the Back School (27). These educational programs guides to properly use the lumbar column in ADLs, such as lifting or moving loads, correct postures and learn techniques for handling ergonomic aids.

Conclusions

Falls in the elderly are presented as a real “geriatric syndrome” characterized by multiple causes and influenced by diverse factors. A multidimensional assessment carried out by a multidisciplinary team is therefore essential, allowing to deal with every single aspect of this syndrome and to optimize the resources and expertise available. The treatment of falls in the elderly patient should be integrated and comprehensive: it must first be preventive, by acting on multiple risk factors for falls; then must take action on the causes of chronic and acute fall. The rehabilitation is as a key event in the natural history of the treatment, in order to increase the residual functional capacity and to educate the patients in a proper and functional management of their resources. In rehabilitation numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of therapeutic exercise in improving the health and quality of life in elderly.

References

- 1.Rubenstein LZ, Robbins AS, Josephson KR, et al. The value of assessing falls in an elderly population. A randomized clinical trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1990;113:308–16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-4-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, Guo Z. Hospitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. The Journal of American Medical Association. 2004;292(17):2115–2124. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.17.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevens JA, Corso PS, Finkelstein EA, Miller TR. The costs of fatal and non-fatal falls among older adults. Injury Prevention. 2006;12:290–295. doi: 10.1136/ip.2005.011015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shumway-Cook A, Ciol MA, Hoffman J, et al. Falls in the Medicare population: incidence, associated factors, and impact on health care. Physical Therapy. 2009;89(4):1–9. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tinetti ME. Preventing falls in elderly persons. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348:42–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp020719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Public Health Agency of Canada, Division of Aging and Seniors. Report on senior’s fall in Canada. Public Health Agency of Canada. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Josephson KR, Rubenstein LZ. The epidemiology of falls and syncope. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2002;18(2):141–58. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(02)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shorr RI, Mion LC, Chandler AM, et al. Improving the capture of fall events in hospitals: combining a service for evaluating inpatient falls with an incident report system. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56(4):701–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01605.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubenstein LZ. Falls in older people: epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age Ageing. 2006;35:37–41. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson JA, Goldsmith CH, Clase CM. Muscle weakness and falls in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:1121–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landi F, Onder G, Cesari M, et al. Psychotropic medications and risk for falls among community-dwelling frail older people: an observational study. The Journal of Gerontology. 2005;60:622–6. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.5.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saliba S, Elliott M, Rubenstein LA, et al. The Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES-13): A Tool for Identifying Vulnerable Elders in the Community. The Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2001;49:1691–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman SM, Munoz B, West SK, et al. Falls and fear of falling: which comes first? A longitudinal prediction model suggests strategies for primary and secondary prevention. The Journal of American Geriatric Society. 2002;50(8):1329–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society, and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Panel on Falls. Prevention Guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons. Journal of American Geriatric Society. 2001;49(5):664–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute of Health Consensus Statement. Journal of American Geriatric Society. 1988;36:342–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb02362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, et al. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of American Medical Association. 2007;298:2623–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.22.2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harari D, Hopper A, Dhesi J, et al. Proactive care of older people undergoing surgery (‘POPS’): designing, embedding, evaluating and funding a comprehensive geriatric assessment service for older elective surgical patients. Age Ageing. 2007;36(2):190–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gates S, Fisher JD, Cooke MW, et al. Multifactorial assessment and targeted intervention for preventing falls and injuries among older people in community and emergency care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal. 2008;336:130–133. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39412.525243.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Onder G, Landi F, Fusco D, et al. Recommendations to Prescribe in Complex Older Adults: Results of the Criteria to Assess Appropriate Medication Use Among Elderly Complex Patients (CRIME) Project. Drugs Aging. 2013 Nov 15; doi: 10.1007/s40266-013-0134-4. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howe TE, Rochester L, Jackson A, et al. [Review]Exercise for improving balance in older people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004963.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Systematic Rev. 2012 Sep;12:9. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faber MJ, Bosscher RJ, Chin A, Paw MJ. Effects of exercise programs on falls and mobility in frail and pre-frail older adults: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2006;87(7):885–96. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rydwik E, Frandin K, Akner G. Effects of physical training on physical performance in institutionalised elderly patients (70+) with multiple diagnoses. Age and Ageing. 2004;33:13–23. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Studenski S, et al. Designing randomized, controlled trials aimed at preventing or delaying functional decline and disability in frail, older persons: a consensus report. Journal of American Geriatric Society. 2004;52:625–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King AC, Rejeski WJ, Buchner DM. Physical activity interventions targeting older adults. A critical review and recommendations. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;15:316–33. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carter ND, Kannus P, Khan KM. Exercise in the prevention of falls in older people: a systematic literature review examining the rationale and the evidence. Sports Medicine. 2001;31(6):427–38. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200131060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heymans MW, van Tulder MW, Esmail R, et al. Back schools for non-specific low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30(19):2153–63. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000182227.33627.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]