Abstract

Objectives

To understand the competition between and among tobacco companies and health groups that led to graphical health warning labels (GHWL) on all tobacco products in India.

Methods

Analysis of internal tobacco industry documents in the Legacy Tobacco Document Library, documents obtained through Indias Right to Information ‘ Act, and news reports.

Results

Implementation of GHWLs in India reflects a complex interplay between the government and the cigarette and bidi industries, who have shared as well as conflicting interests. Joint lobbying by national-level tobacco companies (that are foreign subsidiaries of multinationals) and local producers of other forms of tobacco blocked GHWLs for decades and delayed the implementation of effective GHWLs after they were mandated in 2007. Tobacco control activists used public interest lawsuits and the Right to Information Act to win government implementation of GHWLs on cigarette, bidi and smokeless tobacco packs in May 2009 and rotating GHWLs in December 2011.

Conclusions

GHWLs in India illustrate how the presence of bidis and cigarettes in the same market creates a complex regulatory environment. The government imposing tobacco control on multinational cigarette companies led to the enforcement of regulation on local forms of tobacco. As other developing countries with high rates of alternate forms of tobacco use establish and enforce GHWL laws, the tobacco control advocacy community can use pressure on the multinational cigarette industry as an indirect tool to force implementation of regulations on other forms of tobacco.

INTRODUCTION

With approximately 275 million tobacco users, India is the world’s second largest tobacco market,1 with 16% using cigarettes produced by three dominant cigarette companies (partially owned by multinational tobacco companies), 26% using bidis produced by a combination of large companies and cottage industry manufacturing, and 58% using smokeless tobacco.1 Health warning labels (HWL) on tobacco products with graphical elements (GHWL) are more effective than text-only warnings,2,3 especially in countries like India with several languages and widespread illiteracy.4,5 Multinational tobacco companies have fiercely opposed implementation of effective GHWLs.6–8 We examine the interplay between cigarette companies and domestic bidi companies, which compete for customers while having shared as well as conflicting lobbying interests, and public health groups since 1991 that eventually led to rotating GHWLs on cigarette, bidi and smokeless tobacco in December 2011. India illustrates how joint lobbying by multinational tobacco companies and producers of local forms of tobacco blocked GHWLs for years, and how tobacco control advocates finally overcame this obstruction through innovative use of public interest litigation and the Right to Information Act. India also illustrates how promoting tobacco reduction policies that affect multinational cigarette companies can lead them to press for regulation of local forms of tobacco that are often more difficult to regulate. As other developing countries with high rates of alternate forms of tobacco use establish and enforce GHWL laws, tobacco control advocates can use pressure on the cigarette industry as an indirect tool to force GHWLs on other forms of tobacco.

METHODS

We searched the UCSF Legacy Tobacco Documents Library (http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu) from September 2012 to January 2013 beginning with ‘Indian tobacco industry,’ ‘Indian government,’ ‘ITC,’ ‘GPI,’ ‘VST,’ ‘bidi,’ ‘warning labels,’ ‘HWL,’ and ‘GHWL’ that were dated between 1990 and 2013, using standard snowball techniques,9 then expanded searches to include key people and organisations identified in them and examining documents with adjacent Bates numbers. A total of 140 documents relating to graphic health warning labels in India were chosen for closer analysis. We also reviewed 55 Indian government documents obtained by Hemant Goswami using India’s Right to Information Act, 48 of which were used for this study. (These documents are available as an online supplementary file). Ninety-two media stories were obtained from Lexis Nexis Academic Universe using the snowball strategy.

RESULTS

Tobacco industry in India

Three companies control the Indian cigarette market, ITC Limited (32% owned by British American Tobacco (BAT)) with 80% of the market, Godfrey Phillips India (GPI, 25% owned by Philip Morris International) with 12%, and Vazir Sultan Tobacco (VST, 32% owned by BAT) with 8%.10 (The multinational cigarette companies’ role in India has been limited by restrictions on foreign direct investment.) Six of ITC’s 10 top shareholders are government-owned insurance companies (including Life Insurance Corporation of India, New India Insurance, General Insurance Corporation of India, the Oriental Insurance Company, and National Insurance Company Limited).10 In June 2012, Ghulam Nabi Azad, India’s Union Minister for Health and Family Welfare, called government ownership of ITC’s shares ‘a double interest,’ continuing, ‘On one side you are mobilising the resources through (this investment) and on other side there is a bad impact on the health.’11

Every major political party, including the ruling Congress Party and the major opposition party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), has accepted money from ITC, totalling at least rupees 124 million ($2.2 million) between 2005 and 2011,12–15 and several members of the ITC board of directors held or had held government office.16,17

About 4.5 million people (0.36% of the Indian population) work in the bidi industry18 with bidi production concentrated in southern and western states. Small bidi producers receive a heavy tax subsidy so they can sell their products at low prices19 to small vendors or larger bidi companies for distribution.10

A shifting tide in tobacco regulation

The process of tobacco regulation in India began with the 1975 Cigarettes Regulation of Production, Supply, and Distribution Act that sought to increase cigarette sales (table 1). The Act required small text health warnings stating that ‘cigarette smoking is injurious to health’ on the sides of cigarette packages and in advertisements. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) saw the warning as far too mild to be effective, but the government’s priority was to increase revenue from tobacco.20

Table 1.

Timeline of actions surrounding implementation of GHWLs, tobacco industry strategies and outcomes in India

| Date | Actions | Area/jurisdiction | Public health group activity | Tobacco industry activity (cigarette companies vs bidi companies) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1975 | Indian government passes the Cigarettes Regulation of Production, Supply and Distribution Act, mandating the use of text warning labels on cigarette packs advertisements | Ministries of Commerce, Health and Family Welfare | Unknown | Unknown | Text warning labels implemented in 1975 |

| 1980s–1990s | Pro-tobacco control NGOs founded | Throughout India | Multiple NGOs arise to advocate for tobacco control | Unknown | Environment becomes more favourable for tobacco control legislation |

| 1995 | Results of Indian Parliamentary Committee studying the 1975 Cigarette Regulation of Production, Supply and Distribution Act conclude that the legislation was ineffective at reducing tobacco use in India | Parliament | Unknown | Unknown | Stage is set for further tobacco control legislation |

| 1995 | Parliamentary Committee on Subordinate Legislation recommends use of strongly worded rotating warning label text with pictures and symbols | Lok Sabha (lower house of the parliament) | Unknown | Tobacco industry lobbies for voluntary regulation, then against use of strongly worded rotating text and images | Strongly worded labels with pictures are not implemented |

| 2001 | Parliamentary Standing Committee on Human Resource Development recommends use of skull and crossbones on tobacco packages | Rajya Sabha, (upper house of the parliament) | Unknown | Tobacco industry lobbies against implementation of skull and crossbones | Skull and cross bones image dropped in 2007 |

| 1999–2003 | COTPA process | National | Public health groups advocate for implementation of COTPA | Prior to COTPA, industry lobbies for voluntary code. After COTPA, industry lobbies to weaken provisions of COTPA | Full implementation of COTPA is postponed for several years |

| 2004 | India’s FCTC ratification | National | Public health groups advocate for ratifying FCTC and for implementing its provisions | Industry lobbies against ratification of FCTC | FCTC is ratified but its provisions are not fully implemented |

| 2006 | Public interest litigation is filed asking for enforcement of Article 11 of FCTC, implementation of GHWLs | Himachal Pradesh | Public health groups advocate for enforcement of Article 11 of FCTC | Industry uses economic arguments to argue against implementation of GHWLs | Article 11 of FCTC is enforced in 2012 |

| 2006–2009 | Tobacco industry lawsuits against GHWL law and lobbying | Tobacco Institute of India | Unknown | To delay implementation of pictorial warning labels | Delay in GHWL implementation until May 2009 |

| 2009 | GHWL provision goes into effect on all tobacco products | National | Public health groups advocate for stronger warning labels | Industry lobbies to weaken the warning label requirements advised by FCTC | GHWLs that are implemented are criticised by public health groups as weak |

| Mar 2010 | Government introduces new GHWLs depicting oral cancer to be rotated every twelve months and initiated in June 2010 | National | Public health groups advocate for these stronger warning labels | Industry lobbies to decrease the size and content of the warning labels | Ministry of Health and Family Welfare continues with strong oral cancer GHWLs |

| Jun 2010 | New rotating GHWL implementation delayed by government to December 2010 | National | Public health groups advocate for immediate warning label implementation | Industry lobbies to delay implementation | Implementation delayed until December 2010 |

| Dec 2010 | Implementation of GHWLs delayed by government to May 2011 | National | Public health groups advocate for more frequent rotation of warning labels and immediate implementation | Industry lobbies for further delay | GHWL rotation changed from every year to every two years, and implementation delayed to May 2011 |

| May 2011 | Implementation of GHWLs delayed pictorial warning labels to December 2011 | National | Public health groups advocate for no choice given to industry as to what GHWL to include | Industry lobbies for choice of which GHWLs to include | Industry is given choice of which of four images they would like to include on their labels |

| Dec 2011 | New GHWLs on all tobacco products are introduced | National | Public health groups criticise the labels as ineffective | Industry lobbies for delay in implementation | GHWLs are introduced on all tobacco products |

| Sep 2012 | Government announces introduction of three new GHWLs on cigarettes, bidis, and smokeless products to be introduced 1 April 2013 | National | Unknown | Industry lobbies for delay in implementation | GHWL implementation occurs in April 2013, when three rotating warning labels for cigarettes, bidis and smokeless tobacco are all implemented |

By 1991, government thinking had shifted from generating tobacco revenue to protecting people from tobacco-caused harm: the Government of India convened the first National Conference on Tobacco or Health, bringing together public health professionals and academicians advocating for tobacco control. (Tobacco industry representatives, including staff members of ITC, were invited and attended this conference, but during the last session, the secretary moderating the conference noted that their only motive appeared to be to obstruct and delay the session by not allowing others to speak.) In 1995, the parliamentary committee on subordinate legislation recommended adding stronger warning labels to all tobacco products. Over the next 20 years, the tobacco control landscape in India changed with the emergence of non-governmental organisations advocating for tobacco control.21 In August 1994, noting the increased tobacco control advocacy among community organisations and academics as well as legislation that the Indian government proposed that included a ban on advertising all tobacco-related products and more ‘emphatic’ HWLs, BAT’s regional operations director wrote to the British High Commission in New Delhi asking that the British government to urge India to allow the tobacco companies to implement voluntary HWL and marketing restrictions in lieu of binding legal requirements.22

In February 1995, the parliamentary committee on subordinate legislation of the 10th Lok Sabha (the lower house of parliament) examined the regulations under the Cigarettes Regulation of Production, Supply and Distribution Act from 1975 (table 1). In December 1995, the committee recommended strengthening the language in the warnings, adding pictures, and extending the warnings to bidis and smokeless tobacco. Because some committee members were industry representatives and did not sign the report it was not officially accepted by the government. The Central Ministry of Health also constituted an expert committee on the economics of tobacco use.23

In 1996, the cigarette companies proposed a voluntary code to the Ministry of Commerce that included HWLs and mild marketing restrictions.24 In 1999, the Tobacco Institute of India, the cigarette companies’ lobbying organisation, made the same proposal to the Ministry of Commerce.25 Neither voluntary code specified the size or content of the warnings.

Delay and dilution of GHWLs

In 2001, the Ministry of Health’s expert committee on the economics of tobacco use concluded that the health costs of tobacco outweighed any economic benefit.23

In May 2003, parliament passed the Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Act (COTPA), prohibiting smoking in public places, establishing smoking and non-smoking areas in hotels, restaurants and airports, limiting tobacco advertising, and requiring that by 2007 all tobacco products carry GHWLs (table 1). In February 2004, India ratified the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control26 (FCTC), which committed India to implementing GHWLs by February 2008. FCTC Article 11 specifies that HWLs shall be rotated periodically and large (at least 30% of the front of the pack), preferably including pictures that would disrupt the impact of brand imagery on the pack.27

When the cigarette and bidi industries realised COTPA’s passage was inevitable, they lobbied to centralise all tobacco regulation at the federal level; such language was added in 2004.28 This pre-emption provision prevents localities and states from adopting more stringent policies and shuts off opportunities for tobacco control advocates to lobby for local regulations that decentralised stakeholders could more easily influence.28

In December 2004, 10 months after FCTC ratification, and almost 2 years after enacting COTPA, FCTC-compliant HWLs still had not been implemented, prompting Ruma Kaushik, Advocate of Shimla High Court in the state of Himachal Pradesh, to file public interest litigation against the national government (table 2). In 2004, the Tobacco Growers Welfare Association wrote to Sonia Gandhi, Indian Congress Party leader, asking that COTPA not be implemented, and reported to the MoHFW that Gandhi ‘wrote letters for the [then] Prime Minister, Sri AB Vajpayee, not to implement [COTPA].’29

Table 2.

Key Court Decisions In Public Interest Litigation on Tobacco Control

| Court case/decision date | Details |

|---|---|

| Ramakrishnan and Anr. versus State of Kerala And Ors., 12 July 1999 | Plaintiff K Ramakrishnan argued that smoking should be declared a criminal public nuisance under the Indian Penal Code. The Court ruled that smoking in public was a punishable offense because it violated the right to life in the Indian constitution. |

| Deora versus India and Ors., 2 November 2001 | The Court prohibited smoking in eight types of public places on grounds that smoking impinges on constitutional right to life. |

| Ruma Kaushik, Advocate General of Shimla versus national government, 10 December 2004 | Asked that Article 11 of FCTC is followed with regard to warning labels. The Court stated that the government as per FCTC guidelines, had three years after treaty ratification to enforce the implementation of the warning labels. |

| Union of India versus ITC Limited, 29 September 2008 | The Court rejected the stay of implementation of rules prohibiting smoking in public places. |

| World Lung Foundation South Asia versus Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2 February 2011 | The World Lung Foundation South Asia sued the Indian government for violating COTPA. The Court ordered the Delhi Commissioner of Police to enforce COTPA. |

| The Institute of Public Health versus the State Government of Karnataka, 8 February 2011 | The Institute of Public Health sued to prevent the Indian Tobacco Board from sponsoring international tobacco promotion events. The Court ordered the Tobacco Board to refrain from sponsoring such events. |

| Crusade Against Tobacco versus Union of India, et al, 5 October 2011 | NGO Crusade Against Tobacco sued the Government of India for granting licenses to restaurants allowing smokers. The court mandated non-smoking areas. |

| Kerala Voluntary Health Services versus Union of India, et al, 26 March 2012 | Kerala VHS sued the Union of India for not penalising tobacco use in films and the sale of tobacco near educational facilities. The Court ruled that though the Indian Constitution guarantees freedom of expression, it also guarantees right to life, which had been violated. |

| Naya Bans Sarv Vyapar Assoc versus India, 9 November 2012 | An association of tobacco wholesalers challenged the ban of the sale of tobacco products within a 100-yard radius of any educational institution. The petition was dismissed and the court imposed costs of rupees 20 000 to be paid by the petitioners to the government. |

| Health for Millions versus India, 1 January 2013 | The cigarette industry challenged rules restricting tobacco advertising and requiring GHWLs on cigarette packs in 2005 in Mumbai High Court. The Mumbai High Court issued an interim order that stayed the implementation of these rules until further study was conducted. The stay was challenged in 2010 by the NGO Health for Millions in the Supreme Court and the Himachal Pradesh High Court. On 4 January 2013, the Supreme Court overturned the 2005 interim order and required the government to implement the rules on tobacco advertising and warning labels. |

A June 2006 memo from the external affairs minister to the joint secretary of the MoHFW30 described the industry’s concerted lobbying effort, which included letters from the Tobacco Institute of India, Godfrey Phillips India and the All India Bidi Federation requesting to further delay and weaken the GHWLs’ implementation31 (table 3).

Table 3.

Correspondence between lobbyists and the government from 2006 to 2008

| Date | Sender | Recipient | Lobbying Requests |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 Jun 2006 | Tobacco Institute of India | Ministry of Health and Family Welfare | More time for implementation31 |

| 6 Jun 2006 | Godfrey Phillips India | Ministry of Health and Family Welfare | More time for implementation31 |

| 6 Jun 2006 | All India Bidi Federation | Ministry of Health and Family Welfare | Smaller label size, flexibility with colours, more time for implementation31 |

| 22 May 2007 | Udayan Lall, President of the Tobacco Institute of India | Anbumani Ramadoss, Minister of Health and Family Welfare; Naresh Dayal, Health Secretary, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; Pranab Mukherjee, External Affairs Minister; Bhavani Thyagarajan, Joint Secretary of Health and Family Welfare | Skull and crossbones image should not be used on GHWLs, should only cover 30% of label, labels would impinge on brand identify, graphic images such as babies with tubes in their nostrils would create trauma and panic, bidis should also have GHWLs but enforcement of GHWLs on bidis would be too difficult because almost half are unbranded and unpackaged, and public would in turn believe that bidis are safer than cigarettes.34 |

| 12 September 2007 | Rajnikant Patel, President of the All India Bidi Federation | Anbumani Ramadoss | GHWLs should only cover 30% of the bidi label, bidi company should be able to choose from three images, label should be in same language as bidi name, label should be in a colour that contrasted with the package35 |

| 16 October 2007 | Gopal Krishna, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Commerce and Industry | Bhavani Thyagarajan | Time and cost prohibits GHWL implementation36 |

| 22 October 2007 | Anil Rajput, Senior Vice President of Corporate Affairs, ITC | Bhavani Thyagarajan | Timeframe for implementation of GHWLs inadequate Less graphic and smaller warning labels should be implemented37 |

| October 2007 | Sai Sankar, Managing Director of VST | Bhavani Thyagarajan | Time and cost prohibits GHWL implementation, company did not receive the CD containing the images early enough It would take at least 36 weeks time to implement the revised GHWLs38 |

| 17 October 2007 | Nita Kapoor, Executive Vice President of GPI | Bhavani Thyagarajan | Time and cost prohibits GHWL implementation, company did not receive the CD containing the images early enough It would take at least 36 weeks time to implement the revised GHWLs39 |

| 5 November 2007 | Oscar Fernandes, Minister for Labour and Development | Anbumani Ramadoss | Poor rural workers would be adversely affected by GHWL implementation40 |

| 7 November 2007 | Federation of Andhra Pradesh Tobacco Farmers (cigarette tobacco advocacy organisation) | CP Thakur, Union Health Minister | There should be no restriction on sale around any institution, tobacco farmers will be harmed by GHWLs, tobacco should be treated like other crops, policy is discriminatory against tobacco farmers, alternative employment must be found for millions of tobacco industry workers if this law goes into effect41 |

| 6 November 2007, | Consortium of Indian Farmers Associations | Oscar Fernandes | Poor farm workers would be adversely affected by GHWL implementation43 |

| 7 November 2007 | Federation of Farmers Associations | Oscar Fernandes | Implementing GHWLs will adversely affect economic situation of farmers42 |

| 7 November 2007 | G Siva Ram Prasad of the Nellore and Prakasam Districts Tobacco Growers Association | Oscar Fernandes | Use of GHWLs on domestically produced tobacco products would give legally imported and smuggled tobacco products an unfair advantage, harming Indian farmers29 |

| 3 March 2008 | Ram Poddar | Naresh Dayal | Lobbying for reduced warning label sizes44 |

| 10 March 2008 | Ram Poddar, Chairman of the Tobacco Institute of India | Kamal Nath, Minister of Commerce and Industry | GHWLs would only be required for cigarettes, and this would give consumers the impression that bidis and another non-cigarette tobacco products are safer than cigarettes45 |

| 1 May 2008 | Ram Poddar | CM Sharma, Undersecretary of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare | Extension of timeframe for GHWL implementation because of difficulty with creating new cylinders46 |

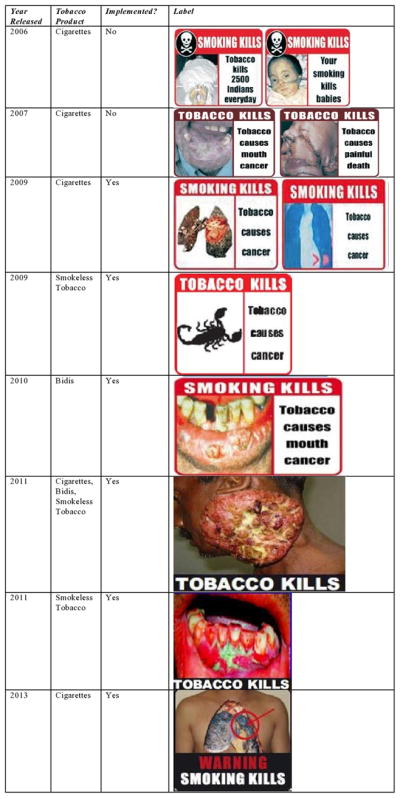

In June 2006, the Shimla High Court ordered the government to enforce rules on packaging and labelling of tobacco products in compliance with COTPA and FCTC guidelines by February 2008. In July, the MoHFW released a set of field-tested GHWLs to be used on cigarette, bidi and smokeless tobacco packages for public review (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Graphic health warning labels in India, 2008–2013.

These GHWLs were to contain a skull and crossbones image as recommended by the parliamentary standing committee on Human Resource Development (table 1), cover at least 50% of the display area of packages, and be rotated every 12 months beginning February 2007.32 The MoHFW first proposed the skull and crossbones in the late 1980s, but it was not implemented due to strong industry opposition. The cigarette and bidi industries continued to lobby heavily against the GHWLs,30,31 and in January 2007, the MoHFW delayed implementation until 1 June 2007, and in February it requested that the prime minister create a task force to further study the issue.21 In response, the prime minister created a task force called the Group of Ministers (GOM) to study GHWLs and make recommendations.21

In September 2007, a spokesman for the All India Bidi Federation, which represented the large bidi manufacturers, told the magazine, Economic Times, ‘the skull and bones warning is typically a sign of poison, and the government should not equate tobacco products with poison’33 (table 3). A senior politician who was a member of the Group of Ministers also argued that the skull and crossbones would offend peoples’ religious sensibilities.47 However, a survey of more than a thousand people showed that the skull and crossbones symbol was understood to indicate danger by illiterate rural populations and that more than ninety percent of Muslims and Hindus agreed that the symbol did not offend their religious sensibilities.

In July 2007, the Group of Ministers recommended that the skull and crossbones image be optional, allowing the cigarette manufacturers to choose whether or not to include it47 (figure 1). The MoHFW followed this recommendation and COTPA was amended in the parliament to completely remove the skull and crossbones in September 2007. The amendment was passed by both houses of parliament without any discussion during a heated debate about India’s non-proliferation treaty, demonstrating the enormous lobbying power of the tobacco industry.

The Group of Ministers also recommended to the MoHFW that the warning labels were to only cover 40% on the front of the pack, not 50% on both sides of the pack, as COTPA required. Though the Group asserted that they were catering to public sentiment by decreasing the size of the warning labels, a 2012 survey conducted by the non-governmental organisation HRIDAY (Health Related Information Dissemination Amongst Youth) in four Indian regions showed that 99% of the respondents supported larger and more effective pictorial warnings included on all tobacco products, including bidis and smokeless tobacco.48,49 The MoHFW released the milder GHWLs for use on cigarette, bidi and smokeless tobacco packs (figure 1).

In October 2007, ITC’s senior vice president of corporate affairs, Anil Rajput, wrote to Bhavani Thyagarajan, joint secretary of the MoHFW, stating that the implementation of GHWLs in September 2007 would lead to closure of some cigarette manufacturing factories in December 2007 and would ‘entail stopping of all manufacturing activities for several months… resulting in substantial revenue loss…’37

In December 2007, in response to the tobacco and bidi industry claims that they could not implement the GHWLs in time because of the lack of proper equipment, the Shimla High Court granted another extension for the implementation of the pictorial image guidelines until March 2008.50 In December 2007, the bidi companies lobbied for smaller warning labels using a single colour and either containing a picture of a bidi with a slash through it, a scorpion, or a child on oxygen, with the bidi company being allowed to choose the image.35 In January 2008, the minister of commerce wrote to prime minister, Dr Manmohan Singh, again urging action on the bidi industry’s requests in terms of size and colour of the warning labels ‘to safeguard the interest of the poor bidi workers.’50

Fighting GHWLs in the courts

In 2007, the cigarette and bidi companies filed lawsuits challenging the new GHWL rules on grounds that they did not have enough time to implement them and enforcement was delayed again. In January 2008, the National Organisation for Tobacco Eradication (NOTE), an NGO advocating for GHWLs, issued a press release stating the ‘Government of India seems to have fallen prey to the argument of Tobacco Industry that the display of Pictorial warnings would invite decline in Consumption, thereby causing unemployment.’51 NOTE also argued that the Group of Ministers was likely to be biased: ‘Shri Pranab Mukherjee [Chair of the GOM and then External Affairs Minister] for instance has a massive presence of [bidi] workers in his constituency. Andhra Pradesh, from where Mr. Jaipal Reddy [then Urban Development Minister] hails, is also a tobacco growing state. Hence one cannot expect a larger perspective and sane decision from the GOM.’51

In March 2008, the government released less explicit GHWLs to be implemented in August 2008 (figure 1), later delayed to November 2008.47 In September 2008, the NGO, Health For Millions, filed a public interest lawsuit alleging that the latest set of GHWLs was too mild, that the implementation of COTPA had been diluted to favour the tobacco industry, and asking that the government implement more effective GHWLs.47

Conflict between the cigarette and bidi industries

The bidi industry lobbied the government aggressively to exempt bidis from the new laws being formulated regarding GHWLs, while the cigarette industry lobbied the government to require GHWLs on bidis and smokeless tobacco products. On April 16, 2008, after receiving letters from the cigarette industry stating that they did not have time to implement the GHWLs, the MoHFW wrote to the Tobacco Institute indicating that the cigarette industry would only be granted a 3-month extension to create the GHWLs because ‘the industry was therefore well aware of the rule provision for quite some time and should have geared itself to implement it quickly.’52 The cigarette industry, accepting the fact that they would have to add GHWLs to their packages, then started lobbying the government to have the GHWL regulations apply to bidis and smokeless tobacco.28,34,53,54

On 6 May 2009, the Supreme Court of India ruled that the latest set of GHWLs should be implemented on 31 May 2009.47 GHWLs were finally implemented on cigarette, bidi, and smokeless tobacco packs depicting a lung X-ray and an image of diseased lungs for cigarette and bidi packs, and a scorpion for smokeless tobacco packs (figure 1).

Many NGOs publicly criticised the GHWLs as too weak to have an impact.55,56 As prominent tobacco control advocacy NGO, Voluntary Health Association of India (VHAI), stated in a press release in December 2010, ‘the Union Health Minister … has yet again compromised on the health of the millions by notifying the ineffective and weak pictorial warnings on tobacco packs…. It is apparent that the Government is repeatedly playing into the hands of a handful of tobacco companies… despite judicial intervention, it is not willing to take any steps towards proper implementation of the packaging and labelling rules, including stronger pictorial warnings.’55 In addition, the tobacco companies were not required to rotate the pictorial warnings, giving them the option to choose the least effective pictorial warning that was available.

Responding to the outcry from the NGOs, on March 5, 2010, the Ministry of Health announced a new set of GHWLs depicting oral cancer to be implemented on cigarettes and smokeless tobacco packs on 1 June 2010 (table 1) that would be rotated every 2 years. The Ministry of Health, however, later delayed implementation until 1 December 2010 in response to the cigarette industry’s continuing claims that they would be unable to implement the GHWLs in time. In response, VHAI and HRIDAY joined forces in a campaign to enlist public support for implementing the oral cancer GHWL on 1 December 2010 without further delay.21

On 3 December 2010, ITC and GPI announced that they had halted manufacturing at all their plants in press releases, citing that they did not know which pictures to print. An ITC spokesman stated, ‘We cannot produce cigarette packets until we do know what to print on them.’57 On 11 December 2010, ITC issued a press release stating that they would not implement the GHWLs until they were given more information from the government about what GHWLs to print. Between December 1 and 23 December the cigarette companies did not implement the new GHWLs, and on 7 December 2010, the MoHFW announced that the GHWL implementation would again be extended, this time until 30 May 2011.58

On December 23, 2010, after getting more direction from the MoHFW about which warnings to print, ITC and GPI resumed cigarette production.59 In addition, in 2011, India’s MoHFW proposed an amendment to the rules which included four additional pictorial warnings to be used on tobacco and bidi packages, and four additional pictorial warnings for smokeless packages. Implementation of these rules began on 1 December 2011, and allowed tobacco companies to choose any one picture out of each set of four images for smoking and four images for smokeless tobacco.57 The new GHWLs started to appear on cigarette, bidi, and smokeless tobacco packs, but did not follow COTPA or the FCTC’s requirements. As the Resource Center for Tobacco Control and the Cancer Institute told the national newspaper, The Hindu, with regard to the removal of the skull and crossbones image, ‘If the tobacco industry is given the option of displaying a mild image (diseased lung) it would choose it over the more graphic image of oral cancer.’60

The concerted efforts of tobacco control NGOs to lobby the Indian Government continued,60 and on 27 September 2012, the MoHFW amended the GHWL rules to include four additional pictorial warning labels to be used for cigarettes and bidis, together with four additional pictorial warning labels for smokeless packages.32 The cigarette and bidi package graphic warnings included three images of diseased lungs and one of oral cancer. Smokeless tobacco warnings showed four images of oral cancer (figure 1). However, even after the new GHWL rules were announced, the tobacco companies argued that the new labels should only be required on the date of manufacture, not the date of sale. The MoHFW agreed to this stipulation even though the packs do not typically carry the date of manufacture, and as a result, the GHWLs only began to slowly appear several months after they were technically required.

DISCUSSION

Implementation of GHWLs in India shows the complex interplay between the cigarette and bidi industries, who have shared as well as conflicting interests. Joint lobbying by multinational tobacco companies, local bidi producers and smokeless tobacco companies blocked effective GHWLs from 2006 to 2009, including delaying implementation of effective GHWLs even after parliament passed legislation requiring them in 2003.61 The release of documents showing the conflict of interest between the Indian government and the tobacco industry through the Right to Information Act catalysed public opinion, leading tobacco control activists to innovatively use public interest lawsuits to force implementation of GHWLs for cigarette, bidi and smokeless tobacco packs in May 2009. Even then, the GHWLs were watered down by the fact that the labels only rotate slowly, run one at a time, and the industry was able to choose the pictures they use on packs.

The unique feature of the Indian tobacco market is the interplay between the consolidated cigarette industry and the more diversified bidi industry. Once it was clear that GHWLs would be placed on cigarette packs, the cigarette industry successfully lobbied the government to also require GHWLs on bidis. The argument that the cigarette industry used was that they were at a competitive disadvantage because they were required to place GHWLs on their packages while the bidi industry was not. In making this argument, the cigarette industry implicitly accepted the fact that GHWLs would reduce smoking. Despite the delays in implementation, one of the major advances from the prolonged Indian GHWL story is that the bidi industry, which has escaped taxation and regulation for years under the guise of being a local industry that benefits the poor, is now finally subject to GHWLs. The Indian GHWL battle demonstrates that in markets where alternative forms of tobacco, such as bidis and smokeless tobacco are common, the cigarette companies can be put in the position of using their considerable political power to press for GHWLs on the full range of tobacco products.

As elsewhere,62,63 BAT and the Tobacco Institute of India tried to use offers of voluntary warning labels (and restrictions on advertising) to displace mandatory requirements. Indeed, the companies, led by BAT, tried a similar tactic in an effort between 1999 and 2001 to convince countries that the FCTC was not necessary, through Project Cerberus, a proposed worldwide voluntary code for self-regulating tobacco advertising and labelling.64,65 Once it became apparent for tobacco companies in India that the enactment of COTPA and the ratification of the FCTC were likely, the tobacco industry shifted from outright opposition to vocally supporting a watered-down version of COTPA over ratification of the FCTC.

The tobacco companies routinely try to secure legislation preempting (removing the authority from) subordinate jurisdictions in which the tobacco companies are weak, and transferring it to jurisdictions where they are strong by securing legislation preempting action at the local or state level.66–68 Afterrealising that COTPA was going to be enacted, the cigarette and bidi industries started lobbying for the adoption of federal regulations that would pre-empt local action to disempower local and state-level tobacco control advocates who might take advantage of decentralised decision making that would likely be more difficult for the companies to influence. The previous evidence on the use of pre-emption is from the USA66–68; India demonstrates that it is a global tobacco industry strategy.

Guidelines for implementing FCTC Article 5.3 recommend avoiding conflicts of interest for government officials and employees and treating a state-owned tobacco industry in the same way as any other tobacco industry.27 The Indian government has substantial financial interests in the cigarette industry, most notably in the biggest cigarette company ITC, and the board of directors of ITC has close links with the government.17 Political parties’ acceptance of the ITC’s campaign contributions in India between 2005 and 2012 conflicts with the FCTC Article 5.3 Guidelines for implementation which states that ratifying nations ‘should have effective measures to prohibit contributions from the tobacco industry…to political parties.’26 More effective implementation of FCTC Article 5.3 might have at least reduced the delay in adopting efficient GHWLs in India.

One of the tobacco industry’s main strategies in developed as well as developing countries is to emphasise the importance of local farming communities.69 The Indian cigarette and bidi industries made similar claims to undermine the implementation of GHWLs between 2006 and 2009, arguing in submissions to the government and the press that the livelihood of the farming community, an enormous sector of the Indian economy, would be endangered by GHWLs. By contrast, the 2001 expert committee convened by parliament concluded that in the long run, tobacco cultivation and use drained economic resources rather than adding to them.23 The tobacco industry is using the same strategy of equating tobacco regulation with harm to farmers in India that they have used globally, despite evidence to the contrary.

India exemplifies how tobacco control measures can be implemented through a combination of persistent lobbying, public interest litigation, and open access to government documents. The Right to Information Act has been important in bringing to light government activities and helped foment the movement among public health advocates for tobacco control implementation by helping them garner public support against the cigarette and bidi industries. The partnership between tobacco control NGOs in India to jointly advocate for tobacco control also lent power to the tobacco control movement. These lessons from India can be used in developing countries which have not yet implemented FCTC-compliant HWLs.70

Multinational cigarette companies have feared that countries passing more effective GHWLs would set precedents for others to follow.8 The GHWLs proposed in India in 1995 were advanced for the time71 when only Iceland had GHWLs.8 Despite being dropped because of aggressive industry lobbying, India was also the first country to seriously consider and implement a skull and crossbones image. With a growing number of countries proposing GHWLs in the 2000s, the industry used diverse strategies to oppose them in Asia and Latin America.72–75 In 2003, when the tobacco bill with GHWLs was passed in India, only two countries (Canada and Brazil; Iceland’s were repealed in 1996) had implemented GHWLs.71 Multinational cigarette companies lobbied aggressively against GHWLs in India because it was a forerunner country with large tobacco markets where the cigarette companies expect to increase sales as smokeless tobacco users and bidi smokers switch to cigarettes.

Limitations

The major limitation of this study is the lack of clear evidence elucidating the motives of the Indian government in delaying implementation of GHWLs. After the internal tobacco industry documents became publicly available, the multinational tobacco companies have become more careful in their written communication. There are few documents from bidi and smokeless tobacco companies. As a result, the role that the smokeless tobacco industry may have played in delay and dilution of GHWLs, and the dynamics between the smokeless tobacco companies, the bidi companies and the cigarette industry, could not be fully considered.

CONCLUSIONS

The joint lobbying of multinational tobacco companies and producers of local forms of tobacco blocked the implementation of HWLs in India from 1975 to 2011, but was finally overcome through innovative tobacco control strategies including filing public interest litigation. The top strategies employed by the industry were (1) the use of the economic livelihood argument, (2) promoting regulation of other tobacco products while downplaying the need for regulation of their own tobacco products, (3) lobbying key members of parliament and (4) at times working in concert with the representatives of other tobacco products to delay and dilute implementation of regulations. The top strategies employed by tobacco control advocates were (1) the use of public interest litigation to promote tobacco control and (2) the use of the Right to Information Act to release documents showing the activities of the cigarette and bidi industries as public opinion shifted in support of tobacco regulation. One of the indirect effects of promoting tobacco control on multinational cigarette companies in India was the enforcement of GHWLs on bidis. As other developing countries with high rates of alternate forms of tobacco use establish and enforce GHWL laws, the tobacco control advocacy community can use pressure on the cigarette industry as an indirect tool to force implementation of regulations on alternative forms of tobacco.

Supplementary Material

What is already known on this subject.

The multinational cigarette and domestic tobacco (bidis and smokeless) industry delayed graphic health warning labels in India from 1995, when they were first proposed, until 2011, when they took effect.

What this study adds

Tobacco control advocates overcame joint lobbying by multinational tobacco companies and producers of local forms of tobacco to block effective health warning labels through innovative use of public interest litigation.

Differences in the objectives of the cigarette and bidi companies eventually facilitated inclusion of warning labels on bidis.

India illustrates how promoting tobacco reduction policies that affect multinational cigarette companies can lead them to press for regulation of local forms of tobacco that are often more difficult to regulate.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the invaluable assistance given by Hemant Goswami, who obtained and made public a host of relevant documents using India’s Right to Information Act, Monika Arora, who gave her considerable insight about GHWLs in India, and CNN-IBN reporter Shalini Anand, who provided valuable insight and background information about the GHWL battle in India.

Funding This work was partly funded by National Cancer Instiute Grant CA-087472. The funding agency played no role in the definition of the research question, conduct of the research, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Additional material is published online only. To view please visit the journal online (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051536).

Contributors SS and SAG developed the idea for the study. SS did most of the data collection. All three authors participated in writing the paper.

Competing interests None.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement The unpublished documents cited in this paper are available as a supplemental file associated with this manuscript.

References

- 1.WHO. Global Adult Tobacco Survey. World Health Organization; 2010. [accessed 27 Dec 2013]. http://whoindia.org/EN/section20/section25.1861.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammond D. Health Warning Messages on Tobacco Products: A Review. Tob Control. 2011;20:327–37. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammond D, Fong GT, Borland R, et al. Text and Graphic Warnings on Cigarette Packages: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Study. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:202–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aftab M, Kolben D, Lurie P. International Cigarette Labelling Practices. Tob Control. 1999;8:368–72. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.4.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Browne J, Hennessey-Lavery S, Rogers K. Worth More Than a Thousand Words: Picture-Based Tobacco Warning Labels and Language Rights in the US Reports on Industry Activity from Outside UCSF. San Francisco: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alechnowicz K, Chapman S. The Philippine Tobacco Industry: “The Strongest Tobacco Lobby in Asia”. Tob Control. 2004;13(Suppl 2):ii71–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Assunta M, Chapman S. A Mire of Highly Subjective and Ineffective Voluntary Guidelines: Tobacco Industry Efforts to Thwart Tobacco Control in Malaysia. Tob Control. 2004;13(Suppl 2):ii43–50. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiilamo H, Crosbie E, Glantz SA. The Evolution of Health Warning Labels on Cigarette Packs: The Role of Precedents, and Tobacco Industry Strategies to Block Diffusion. Tob Control. 2014;23:e2. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter SM. Tobacco Document Research Reporting. Tob Control. 2005;14:368–76. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.010132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Tobacco Industry Profile--India. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anand S. [accessed 4 Mar 2014];Govt-Run Firms Violate Treaty for Tobacco Control. 2012 http://ibnlive.in.com/news/govtrun-firms-violate-treaty-for-tobacco-control/263360-3.html.

- 12.Indian Tobacco Company. Annual Report. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Indian Tobacco Company. Annual Report. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Indian Tobacco Company. Annual Report. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Indian Tobacco Company. Annual Report. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.ITC. [accessed 20 Jun 2013];Board of Directors. 2013 http://www.itcportal.com/about-itc/leadership/board-of-directors.aspx.

- 17.Indian Tobacco Company. Annual Report. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Bidi Smoking and Public Health in India. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krishnan M. In India, Bidi Industry’s Clout Trumps Health Initiatives. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reddy KS, Gupta PK. Report on Tobacco Control in India. Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arora M, Yadav A. Pictorial Health Warnings on Tobacco Products in India: Sociopolitical and Legal Developments. The National Medical Journal of India. 2010;23:357–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis N. Proposed Legislation to Ban Advertising of Tobacco Products in India. British American Tobacco; Aug 19, 1994. [accessed 25 Jan 2013]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ras41a99. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Government of India. Government of India Report of the Expert Committee on the Economics of Tobacco Use New Delhi, India. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Opukah S. Voluntary Code. British American Tobacco; Mar 12, 1996. [accessed 25 Jan 2013]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vjs63a99. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tobacco Institute of India. Proposed Voluntary Code for the Marketing of Tobacco Products. British American Tobacco; 1999. [accessed 25 Jan 2013]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ujs63a99. [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; Geneva. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO. Guidelines for Implementation of the WHO TCTC.Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Conference of the Parties; [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lall U. Communication between Udayan Lall of the Tobacco Institute of India and Anbumani Ramdoss of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Annexure 1. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Tobacco Growers Welfare Association. Communication from the Tobacco Growers Welfare Association to Sonia Gandhi. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta P. Communication between Pradeep Gupta to Bhavani Thyagarajan. Jun, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma CM. Hemant Goswami’s collection released by FOIA. Jun 6, 2006. Internal Memo from C.M. Sharma to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Government of India. Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (Packaging and Labelling) Amendment Rules. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhushan R, Prasad GC. The Economic Times. Sep 8, 2007. Mandatory Pictorial Warning to Push up Cigarette Cos’ Costs. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lall U. Communication between Udayan Lall and Pranab Mukherjee. May 22, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel R. Communication between Rajnikant Patel and Ambumani Ramdoss. Sep 12, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krishna G. Communication between Gopal Krishna and Bhavani Thyagarajan. Oct 16, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajput A. Communication between Anil Rajput and Bhavani Thyagarajan. Oct 22, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sankar NS. Communication between N. Sai Sankar and Bhavani Thyagarajan. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kapoor N. Communication between Nita Kapoor and Bhavani Thyagarajan. Oct 17, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernandes O. Communication between Oscar Fernandes and Anbumani Ramdoss. Nov 5, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Federation of Andhra Pradesh Tobacco Farmers. Communication from Federation of Andhra Pradesh Tobacco Farmers to Union Minister C.P. Thakur. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Federation of Farmers Associations. Communication between Federation of Farmers Assocations and Oscar Fernades. Nov 7, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fernandes O. Communication between Oscar Fernandes and the Consortium of Indian Farmers Associations. Nov 6, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poddar RA. Communication between R.A. Poddar and Shri Kamal Nath. Mar 10, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poddar RA. Communication between R.A. Poddar and Naresh Dayal. Mar 3, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poddar RA. Communication between R.A. Poddar and C.M. Sharma. May 1, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reddy SK, Arora M. Pictorial Health Warnings Are a Must for Effective Tobacco Control. Indian J Med Res. 2009;129:468–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arora M, Tewari A, Nazar G, et al. Ineffective Pictorial Health Warnings on Tobacco Products: Lessons Learnt from India. Indian J Public Health. 2012;56:61–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.96978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raute L, Mangesh S, Pednekar M, et al. Pictorial Health Warnings on Cigarette Packs: A Population Based Study Findings from India. Tobacco Use Insights. 2009;2:11–6. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reddy S. Communication between Sanjeeva Reddy and Manmohan Singh. Jan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 51.National Organization for Tobacco Eradication (NOTE) Press Release. Jan 12, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharma CM. Correspondence between C.M. Sharma and Udayan Lall. Apr 16, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lall U. Communication between Udayan Lall and Bhavani Thyagarajan. India: May 11, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lall U. Correspondence between Udayan Lall and Anbumani Ramdoss. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 55.The Hindu. The Hindu. Dec 27, 2010. Thumbs Down for Weak Pictorial Tobacco Warnings. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oswal K, Raute L, Pednekar M, et al. Are Current Tobacco Pictorial Warnings in India Effective? Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:121–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.PTI. Economic Times. Dec 11, 2010. Will Resume Cigarette Production Only after Govt Order: Itc. [Google Scholar]

- 58.PTI. Economic Times. Dec 8, 2010. Cigarette, Bidi Cos Win a Year’s Reprieve on Warnings. [Google Scholar]

- 59.PTI. Economic Times. Dec 23, 2010. Godfrey Phillips, Itc Resume Cigarette Production. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kannan R. The Hindu. Jun 4, 2011. New Pictorial Warnings for Tobacco Products Notified. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oswal K, Pednekar M, Gupta P. Tobacco Industry Interference for Pictorial Warnings. Indian J Cancer. 2010;47:s101–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.65318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sebrie EM, Schoj V, Glantz SA. Smokefree Environments in Latin America: On the Road to Real Change? Prev Control. 2008;3:21–35. doi: 10.1016/j.precon.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Samet J, Wipfli H, Perez-Padilla R, et al. Mexico and the Tobacco Industry: Doing the Wrong Thing for the Right Reason? BMJ. 2006;332:353–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7537.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mamudu HM, Hammond R, Glantz S. Tobacco Industry Attempts to Counter the World Bank Report Curbing the Epidemic and Obstruct the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:1690–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mamudu HM, Hammond R, Glantz SA. Project Cerberus: Tobacco Industry Strategy to Create an Alternative to the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Am J Pub Health. 2008;98:1630–42. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mowery PD, Babb S, Hobart R, et al. The Impact of State Preemption of Local Smoking Restrictions on Public Health Protections and Changes in Social Norms. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:632629. doi: 10.1155/2012/632629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nixon ML, Mahmoud L, Glantz SA. Tobacco Industry Litigation to Deter Local Public Health Ordinances: The Industry Usually Loses in Court. Tob Control. 2004;13:65–73. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.004176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.O’Connor JC, MacNeil A, Chriqui JF, et al. Preemption of Local Smoke-Free Air Ordinances: The Implications of Judicial Opinions for Meeting National Health Objectives. J Law Med Ethics. 2008;36:403–12. 214. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Otanez M, Glantz SA. Social Responsibility in Tobacco Production? Tobacco Companies’ Use of Green Supply Chains to Obscure the Real Costs of Tobacco Farming. Tob Control. 2011;20:403–11. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.039537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tumwine J. Implementation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in Africa: Current Status of Legislation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8:4312–31. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8114312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Canadian Cancer Society. Cigarette Package Health Warnings. International Status Report. 2012 Oct; http://www.cancer.ca/Canada-wide/About%20us/Media%20centre/CW-Media%20releases/CW-2012/~/media/CCS/Canada%20wide/Files%20List/English%20files%20heading/PDF%20-%20Communications/CCS-intl%20warnings%20report%202012-4%20MB.ashx.

- 72.Crosbie E, Glantz SA. Tobacco Industry Argues Domestic Trademark Laws and International Treaties Preclude Cigarette Health Warning Labels, Despite Consistent Legal Advice That the Argument Is Invalid. Tob Control. 2014;23:e7. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Crosbie E, Sebrie EM, Glantz SA. Tobacco Industry Success in Costa Rica: the Importance of FCTC Article 5. 3. Salud Publica Mex. 2012;54:28–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sebrie EM, Blanco A, Glantz S. Cigarette Labeling Policies in Latin America and the Caribbean: Progress and Obstacles. Salud Publica de Mexico. 2010;52:s233–243. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342010000800019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Alderete M, Gutkowski P, Shammah C. Case Studies 2010–2012. Argentina: 2010–12. Health Is Not Negotiable. Civil Society against the Tobacco Industry’s Strategies in Latin America. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.