Abstract

Four chiral OsII arene anticancer complexes have been isolated by fractional crystallization. The two iodido complexes, (SOs,SC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)I]PF6 (complex 2, (S)-ImpyMe: N-(2-pyridylmethylene)-(S)-1-phenylethylamine) and (ROs,RC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)I]PF6 (complex 4, (R)-ImpyMe: N-(2-pyridylmethylene)-(R)-1-phenylethylamine), showed higher anticancer activity (lower IC50 values) towards A2780 human ovarian cancer cells than cisplatin and were more active than the two chlorido derivatives, (SOs,SC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)Cl]PF6, 1, and (ROs,RC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)Cl]PF6, 3. The two iodido complexes were evaluated in the National Cancer Institute 60-cell-line screen, by using the COMPARE algorithm. This showed that the two potent iodido complexes, 2 (NSC: D-758116/1) and 4 (NSC: D-758118/1), share surprisingly similar cancer cell selectivity patterns with the anti-microtubule drug, vinblastine sulfate. However, no direct effect on tubulin polymerization was found for 2 and 4, an observation that appears to indicate a novel mechanism of action. In addition, complexes 2 and 4 demonstrated potential as transfer-hydrogenation catalysts for imine reduction.

Keywords: anticancer agents, arene ligands, chirality, organometallic, osmium

Introduction

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has defined strict rules for the development of new stereoisomeric drugs, especially following the tragedy of severe birth defects caused by the S isomer of thalidomide1 (originally developed as an antisedative drug, then found to be an inhibitor of angiogenesis for anticancer treatment2, 3). The fast-growing field of bioorganometallic chemistry has attracted much interest in the development of the next generation of anticancer agents following the success of the platinum-based drugs cisplatin, carboplatin, and oxaliplatin.4–8 Examples include ruthenium and osmium organometallic complexes that show promising anticancer activity.9–18 Notably, a number of these organometallic complexes contain chiral metal centers.13–18 Although there are no preclinical or clinical reports of different activity of specific stereoisomers of an organometallic complex, it is of interest to investigate the possible role of stereochemistry in the biological activity for this class of compounds. In particular, the design of metal-based anticancer agents now also includes those interacting with protein targets, a fact that requires careful control of the chirality on the metal center.19, 20 For example, the chirality of a ruthenium center has been shown to affect the inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3β.21 However, such studies are scarce, probably owing to the difficulty of isolating enantiomers or diastereomers of organometallic complexes.22, 23

The first examples of organometallic complexes isolated with defined chiral metal centers appear to be those reported in 1969 by Brunner:24 [M(η5-C5H5)(CO)(NO)(Ph3P)] (M=Cr, Mo, W) and [Mn(η5-C5H5)(CO)(NO)(Ph3P)]PF6. These complexes are all configurationally stable in the solid state. The configurational stability of the metal center in solution depends on the monodentate ligand; for example, (RMn,RC)- and (SMn,RC)-[Mn(η5-C5H5)(CO)(NO)(Ph3P)]PF6 are configurationally stable, whereas (RMn,RC)- and (SMn,RC)- [Mn(η5-C5H5)(COR)(NO)(Ph3P)]PF6 (R=acyl) can epimerize.25 Other factors involved in the configurational lability at the metal center in solution, such as temperature, solvent, or structural features, have been analyzed for diastereomeric RuII organometallic arene complexes,26–28 but fewer studies have been carried out on epimerization of OsII arene diastereomers.29 Examples of enantiopure half-sandwich anticancer complexes are scarce in the literature.30, 31 In particular, the biological properties of pure epimers of chiral-at-osmium arene complexes have not been reported to date.

OsII,32–34 OsIII,35 OsIV[36] and OsVI[37] complexes have been reported to show promising anticancer activity in recent years. Half-sandwich OsII organometallic arene anticancer complexes containing a monodentate ligand and an unsymmetrical chelating ligand are chiral. Previously, we reported that the synthesis of the anticancer OsII arene iminopyridine (Impy) complex, [Os(η6-p-cym)(Impy-OH)I]PF6 (p-cym= para-cymene, Impy-OH=4-[(2-pyridinylmethylene)amino]-phenol), gives a mixture of enantiomers in approximately 1:1 ratio.14 The enantiomeric resolution of such organometallic arene complexes would also be interesting in terms of elucidating mechanisms of action. Nevertheless, the purification of chiral osmium isomers is not easily achieved as chiral columns often produce low yields, and selective chiral synthesis on a metal center is still not readily achievable. Introduction of a chiral carbon atom into the chelated iminopyridine ligand of OsII arene complexes has allowed a facile separation by fractional crystallization of the resulting diastereomeric complexes, which have different physical properties.

Organometallic arene iminopyridine complexes containing ruthenium38, 39 and iridium40 can also act as transfer-hydrogenation catalysts. Catalytic transfer hydrogenation is a useful method for the preparation of amines of biological and chemical interest.41 The herein-reported OsII arene diastereomers could be also attractive as asymmetric catalysts. There are very few reports on the catalytic potential of OsII arene complexes as transfer-hydrogenation catalysts for imine reduction.42, 43 Thus, the four OsII arene iminopyridine complexes were also investigated as transfer-hydrogenation catalysts42, 43 using a model imine substrate.

Results

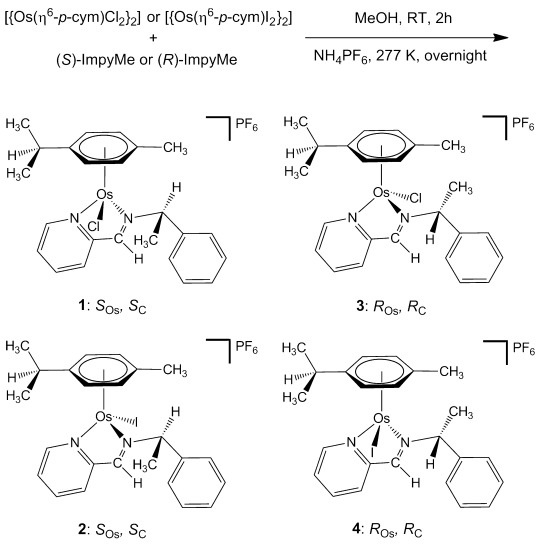

The pure chiral iminopyridine ligand ((S)- or (R)-ImpyMe: N-(2-pyridylmethylene)-(S)-1-phenylethylamine or N-(2-pyridylmethylene)-(R)-1-phenylethylamine) was reacted with the OsII dimer—[{Os(η6-p-cym)Cl2}2] or [{Os(η6-p-cym)I2}2]—to form both diastereomers; the diastereomer that crystallized first was collected from each reaction and the second diastereomer was left in the mother liquor. Only isolated single crystals were used for the physical and biological studies of all the four osmium complexes reported in this work. Although this approach to the study of chirality has been widely used on RuII and OsII arene catalysts with “piano-stool” geometry, there appears to be no report of any application in metallo-drug research. This approach could pave the way for further investigations on the effect of chirality of osmium metal centers on their pharmacological behavior, including metabolism, toxicity, tissue distribution, and excretion kinetics.44

Synthesis and characterization: Two asymmetric imine ligands (S)- and (R)-ImpyMe containing a chiral carbon atom were synthesized by condensation of 2-pyridine carboxaldehyde with (S)-(−)-α-methylbenzylamine or (R)-(+)-α-methylbenzylamine and were purified by distillation by following a reported method.45 Four OsII arene iminopyridine complexes of general formula [Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)X]PF6 (X=Cl, I) were synthesized by reaction of the corresponding dimer [{Os(η6-p-cym)X2}2] (X=Cl, I) and the chiral ligands (S)- or (R)-ImpyMe as described in the Experimental Section. As the chiral configuration of each enantiopure ligand is retained in solution, the OsII arene complexes were obtained as a mixture of two diastereomers differing only in the metal configuration (ROs or SOs). The isolation of diastereomerically pure complexes was accomplished by a crystallization method (Scheme 1). Thus, chiral-at-OsII iminopyridine chlorido and iodido complexes 1, 2, 3, and 4 were isolated as single crystals grown overnight at 277 K from a concentrated methanol solution. Unfortunately, the second diastereomer expected from each reaction could not be isolated as a pure compound although its formation was confirmed in the case of compound 3. All four pure chiral OsII iminopyridine complexes were characterized by CHN analysis, X-ray diffraction, ESI+ MS, 1H NMR and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy and their stability in aqueous solution was confirmed before screening for the anticancer activity.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route for the chiral OsII complexes used in this work.

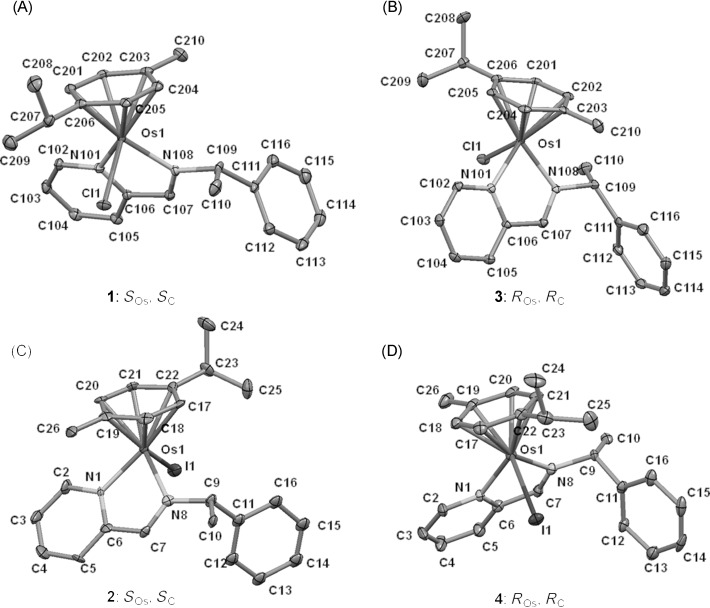

X-ray diffraction: The molecular structures of the OsII arene iminopyridine complexes 1, 2, 3, and 4 were established by X-ray crystallography. Only one pure diastereomer was observed in the unit cell of each compound and therefore the chirality on the osmium center could be determined unambiguously. The structures, along with their atom numbering schemes, are shown in Figure 1 A–D. Selected bond lengths and angles are listed in Tables 1 and 2. X-ray crystallographic data are reported in Table 3; the data show all the complexes crystallized in the same monoclinic space group: P21. The complexes adopt the expected pseudo-octahedral “piano-stool” geometry with the osmium center bound to the arene ligand through η6 bonding (Os–arene centroid 1.682–1.695 Å). Additionally, OsII is bound to a chloride (2.3892(7)–2.3913(8) Å) or iodide (2.7068(6)–2.7078(4) Å) and two nitrogen atoms (2.074(5)–2.124(9) Å) of the chelating ligand through σ bonds, these ligands constitute the three-legged structure of the “piano stool”. All the bond lengths and angles are in agreement with analogous osmium complexes previously reported.46

Figure 1.

X-ray crystal structures of 1 (A), 2 (C), 3 (B), and 4 (D). Thermal ellipsoids are shown at 50 % probability. The hydrogen atoms and counterion have been omitted for clarity.

Table 1.

Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°] for complexes 1 and 3.

| 1(SOs,SC)[a] | 3(ROs,RC)[b] | |

|---|---|---|

| Os(1)–N(101) [Å] | 2.082(3) | 2.086(2) |

| Os(1)–N(108) [Å] | 2.084(2) | 2.086(2) |

| Os(1)–arene centroid [Å] | 1.685 | 1.682 |

| Os(1)–Cl(1) [Å] | 2.3913(8) | 2.3892(7) |

| N(101)-Os(1)-N(108) [°] | 76.61(10) | 76.43(9) |

Non-classical hydrogen-bond interactions for complex 1: C102–H10A⋅⋅⋅F12, 2.48 Å [x, y, 1+z]; C105–H10D⋅⋅⋅F14, 2.44 Å [1+x, y, 1+z]; C109–H10F⋅⋅⋅F13, 2.37 Å; C202–H20B⋅⋅⋅F15, 2.40 Å; C205–H20D⋅⋅⋅F14, 2.43 Å [x, y, 1+z].

Non-classical hydrogen-bond interactions for complex 3: C102–H10A⋅⋅⋅F12, 2.48 Å [x, y, −1+z]; C105–H10D⋅⋅⋅F14, 2.44 Å [−1+x, y, −1+z], C109–H10F⋅⋅⋅F13, 2.38 Å; C202–H20B⋅⋅⋅F15, 2.39 Å; C205−H20D⋅⋅⋅F14, 2.43 Å [x, y, −1+z].

Table 2.

Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°] for complexes 2 and 4.

| 2(SOs,Sc)[a] | 4(ROs,Rc)[b] | |

|---|---|---|

| Os(1)–N(1) [Å] | 2.084(6) | 2.090(4) |

| Os(1)–N(8) [Å] | 2.090(7) | 2.074(5) |

| Os(1)–arene centroid [Å] | 1.689 | 1.695 |

| Os(1)–I(1) [Å] | 2.7068(6) | 2.7078(4) |

| N(1)-Os(1)-N(8) [°] | 75.9(3) | 76.17(17) |

Non-classical hydrogen-bond interactions for complex 2: C4–H4A⋅⋅⋅F12, 2.37 Å [−1+x, y, z]; C7–H7A⋅⋅⋅F13A, 2.30 Å [−1+x, y, −1+z].

Non-classical hydrogen-bond interactions for complex 4: C4–H4A⋅⋅⋅F12, 2.37 Å [1+x, y, z]; C7–H7A⋅⋅⋅F13A, 2.31 Å [1+x, y, 1+z].

Table 3.

X-ray crystallographic data and structure refinement for complexes 1, 3 and 2, 4.

| 1(SOs,Sc) | 3(ROs,Rc) | 2(SOs,Sc) | 4(ROs,Rc) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| formula | C24H28ClF6N2OsP | C24H28ClF6N2OsP | C24H28F6IN2OsP | C24H28F6IN2OsP |

| Mr | 715.1 | 715.1 | 806.55 | 806.55 |

| crystal system | monoclinic | monoclinic | monoclinic | monoclinic |

| crystal size [mm] | 0.25×0.18×0.16 | 0.24×0.20×0.20 | 0.18×0.18×0.06 | 0.35×0.35×0.12 |

| space group | P21 | P21 | P21 | P21 |

| crystal | brown block | orange block | brown block | brown block |

| a [Å] | 10.19773(12) | 10.19210(18) | 9.1232(2) | 9.1232(2) |

| b [Å] | 11.79001(13) | 11.78829(18) | 15.0439(4) | 15.0439(4) |

| c [Å] | 10.99917(13) | 10.99531(18) | 9.6304(2) | 9.6304(2) |

| α [°] | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| β [°] | 103.0453(12) | 103.0937(17) | 97.591(3) | 97.591(3) |

| γ [°] | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| T [K] | 100(2) | 100(2) | 100(2) | 100(2) |

| Z | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| μ [mm−1] | 5.174 | 5.181 | 6.164 | 6.164 |

| reflections collected | 27 544 | 11 484 | 13 060 | 12 315 |

| independent reflections [Rint] | 8081 [0.0360] | 6327 [0.0204] | 6754 [0.0526] | 6765 [0.0294] |

| R1, wR2 [F>4σ(F)][a,b] | 0.0241, 0.0517 | 0.0184, 0.0387 | 0.0427, 0.0951 | 0.0280, 0.0691 |

| R1, wR2 (all data)[a,b] | 0.0260. 0.0526 | 0.0192, 0.0391 | 0.0522, 0.0989 | 0.0288, 0.0698 |

| GOF[c] | 1.017 | 1.022 | 1.02 | 1.03 |

| Δρ max/min [e Å−3] | 1.217 and −0.796 | 1.046 and −0.718 | 2.220 and −1.676 | 1.904 and −1.058 |

R1=Σ||Fo|−|Fc||/Σ|Fo|.

.

.

.

.

Cahn–Ingold–Prelog priority rules (CIP system) cannot be applied directly to pseudo-four-coordinate organometallic chiral-at-metal arene complexes. Therefore, to assign the chirality in the R and S convention for these OsII arene complexes, the modified CIP rules for organometallic arene complexes suggested by Tirouflet et al.47 and Stanley and Baird48 were used; the p-cymene arene (η6-C6) was considered as a pseudo-atom with atomic weight 72. We defined the priority sequence of ligands attached to the OsII center as follows:47, 48 η6-C6>Cl>N (imine)>N (pyridine) or I>η6-C6>N (imine)>N (pyridine). According to the sequence rule of the R/S system, the configurations of the OsII centers in these four chiral osmium arene iminopyridine complexes are: 1=SOs, 2=SOs, 3=ROs, and 4=ROs. Therefore, the retention of chirality at osmium between each chlorido complex and its iodido analogue is just a consequence of the change in the priority sequence, as an inversion of configuration at the metal center is observed in the crystal structures (Figure 1 A–D).

The four complexes can be divided into two enantiomeric pairs according to the different monodentate ligand coordinated to osmium (chloride or iodide): (SOs,SC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)Cl]PF6 (1) and (ROs,RC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)Cl]PF6 (3), (SOs,SC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)I]PF6 (2) and (ROs,RC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)I]PF6 (4). The comparison between the crystal structures of both pairs of complexes showed no significant differences in their bond lengths and angles around the osmium center.

1H NMR spectroscopy: The 1H NMR spectra of 1, 2, 3, and 4 in [D6]acetone were recorded at 298 K. Identical 1H NMR data (see Experimental Section) were obtained for both of the chlorido complexes, 1 and 3, as well as for both of the iodido complexes, 2 and 4. These results suggest the molecular structures of each pair of OsII iminopyridine complexes are mirror images of each other.

To probe the formation of both diastereomers differing at the metal configuration, the first fraction of crystals of 3 was filtered off and the remaining solution was concentrated under reduced pressure to give an orange crystalline product. The 1H NMR data for the orange product showed a diastereomeric mixture of (ROs,RC)- and (SOs,RC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)Cl]PF6 in approximately 1:1 ratio instead of a single diastereomer (see the Supporting Information, Figure S1). This finding is consistent with a previous report on RuII and OsII arene salicylaldiminates complexes.29 There were only small differences between the 1H NMR chemical shifts of both diastereomers, a fact that made it difficult to identify which was the most stable product. For this reason, an initial crystallization step was necessary to obtain pure chiral-at-OsII complexes that separately exhibit different chemical shifts.

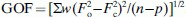

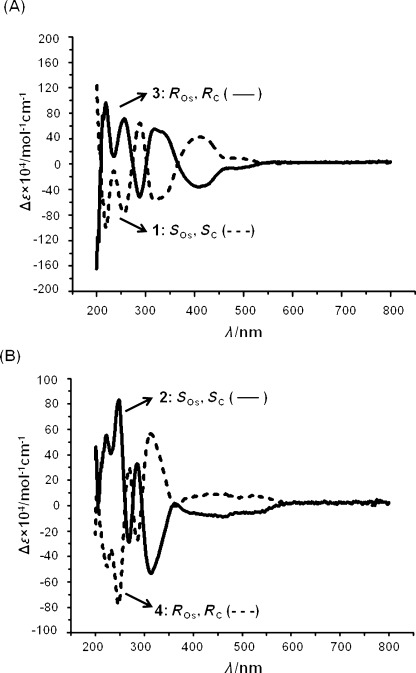

Circular dichroism: To gain further understanding of the enantiomeric relationships between these pairs of complexes, CD spectra were recorded. This technique measures the differential absorption of left- and right circularly polarized light and is widely used to confirm chiral purity. The CD spectra were recorded for each of the four OsII iminopyridine complexes in methanol. The chlorido complexes, 1 and 3, and iodido complexes, 2 and 4, gave complementary CD spectra (Figure 2). Complex 1 showed positive Cotton effects at 412 and 288 nm, and negative Cotton effects at 318, 256 and 220 nm. Complex 2 showed positive Cotton effects at 285, 247 and 221 nm, and negative Cotton effects at 450, 313 and 268 nm. Opposite Cotton effects were observed for complexes 1 and 2 and for complexes 3 and 4. Although CD cannot give information on the absolute configuration at the chiral osmium center in the individual complexes in solution, such results confirm that the two molecular structures within the two pairs of OsII iminopyridine complexes are mirror images.49

Figure 2.

Circular dichroism spectra for the two pairs of OsII arene iminopyridine complexes: (A) 1 and 3; (B) 2 and 4.

Stability in aqueous solution: Although chiral metal centers are usually stable in the solid state at ambient and physiological temperatures, they can behave differently in solutions in which epimerization can occur at ambient temperature with a half-life (τ1/2) less than 24 h.50 The configurational stability of the metal center in organometallic complexes in solution may depend on the ligands around the metal;51–53 for example, early work on the RuII arene iodido complexes [Ru(η6-p-cym)(LL*)I] (LL*=(SC)-(−)-dimethyl(1-phenylethyl)amine) showed that they were more configurationally labile compared with their chlorido analogues.54 However, there are no reports on the analogous OsII arene complexes. In general, epimerization occurs in solvents such as acetone, methanol, CH2Cl2, or CHCl3 giving rise to the thermodynamic product as the major epimer in solution. Nevertheless, diastereomeric complexes have been shown to be stereochemically stable in hydrocarbon-based solvents.55

The configurational stability of OsII arene complexes that are designed as anticancer agents is of particular interest. Each of the four OsII arene complexes were dissolved in 10 % CD3OD/90 % D2O phosphate buffer (pH* 7.4), and 1H NMR spectra were recorded before and after incubation for 24 h at 310 K. The two iodido complexes, 2 and 4, showed good stability with no change in the 1H NMR spectra after the incubation period. In contrast, the 1H NMR spectra for both chlorido complexes, 1 and 3, showed new peaks, which may correspond to epimerization or aquation products (see the Supporting Information, Figure S2). When complexes 1 and 3 were incubated at 310 K in the presence of a high molar excess (1000-fold) of sodium chloride (to suppress aquation) and the 1H NMR spectra recorded, no new peaks appeared indicating that the aforementioned new resonances correspond to aquation products and that these complexes are stable towards epimerization. The possibility of substitution of iodide by chloride was investigated for the two iodido complexes, 2 and 4. The NMR data showed no substitution of iodide by chloride for either 2 or 4 (100 μM) at high concentrations of Cl− (5000 mol equiv, 500 mM) (see the Supporting Information, Figure S2).

Anticancer activity: Iminopyridine- and azopyridine-containing complexes56, 57 with Ru and Os centers can exhibit potent anticancer activity.58–62 In particular, an OsII arene azopyridine complex is active in vivo.56 Therefore, the anticancer activities of the four OsII arene iminopyridine complexes 1–4 were studied in the human ovarian cancer cell line A2780. After 24 h incubation followed by 72 h recovery time, the two chlorido Os complexes, 1 and 3, showed moderate anticancer activity, with IC50 values of approximately 20 μm, similar to the value obtained for the mixture of (ROs,RC)- and (SOs,RC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)Cl]PF6 (Table 4) and significantly higher than that of cisplatin (2 μM). On the other hand, the IC50 values of the two iodido osmium complexes, 2 and 4, are in the same range as that of cisplatin (Table 4). These two iodido complexes were further screened in the NCI (National Cancer Institute) panel of 60 human tumor cell lines at five concentrations63, 64 and both 2 and 4 showed potent anticancer activities with mean IC50 values of 9.55 and 7.58 μM, respectively. In contrast, the two chlorido complexes, 1 and 3, were not sufficiently active when tested against the NCI 60-cell-line panel (mean IC50 values >10 μM) to warrant 5-dose testing. The mean growth inhibition parameters determined in the NCI screen of MG-MID (full-panel mean-graph midpoint) values of IC50 (the concentration that inhibits cell growth by 50 %), TGI (the concentration that inhibits cell growth by 100 %), and LC50 (the concentration that kills 50 % of the original cells) are listed in Table 5. The details for each cell line and the values of IC50, TGI, and LC50 are shown in Table S1 (see the Supporting Information). Similar to cisplatin, the two OsII iodido complexes showed a broad range of anticancer activities towards different cell lines, with IC50 values ranging from nanomolar to micromolar (530 nM to >100 μM).

Table 4.

IC50 values for the A2780 ovarian cancer cell line.

| Complex | IC50 [μM] |

|---|---|

| (SOs,SC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)Cl]PF6 (1) | 22.3 (±1.6) |

| (SOs,SC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)I]PF6 (2) | 1.9 (±0.2) |

| (ROs,RC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)Cl]PF6 (3) | 18.3 (±1.7) |

| (ROs,RC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)I]PF6 (4) | 0.60 (±0.02) |

| (ROs,RC) and (SOs,RC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)Cl]PF6 mixture[a] | 19.0 (±1.1) |

| cisplatin | 2.0 (±0.2) |

Ratio approximately 1:1.

Table 5.

Mean IC50, TGI and LC50 values from the NCI-60 data for complexes 2 and 4.

| Complex[a] | IC50 [μM][b] | TGI [μM][c] | LC50 [μM][d] |

|---|---|---|---|

| (SOs,SC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)I]PF6 (2) | 9.55 | 61.7 | 91.2 |

| (ROs,RC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)I]PF6 (4) | 7.58 | 53.7 | 89.1 |

| cisplatin[e] | 1.49 | 9.33 | 44.0 |

NCI codes for complex 2: NSC: D-758116/1 and 4: NSC: D-758118/1.

IC50=the concentration that inhibits cell growth by 50 %.

TGI=the concentration that inhibits cell growth by 100 %.

LC50=the concentration that kills 50 % of the original cells.

Cisplatin data from NCI/DTP screening: March 2012, 48 h incubation time.79

Catalysis of imine reduction: Organometallic ruthenium,40 rhodium65 and iridium66 complexes have been found to act as transfer-hydrogenation catalysts for the asymmetric reduction of ketones and imines. However, there are very few reports of the catalytic activity of osmium complexes,43, 44 especially for OsII arene complexes.67 The possible catalytic activity of the two OsII arene iminopyridine iodido complexes, 2 and 4, for cyclic imine (6,7-dimethoxy-1-methyl-3,4-dihydroisoquinoline) reduction was therefore evaluated. We observed a reasonable conversion (20–76 %) and low ee value (20–22 %) for reactions with both OsII complexes in less than 24 h (see the Supporting Information, Figure S4),68 demonstrating potential of the complexes as transfer-hydrogenation catalysts. This appears to be the first report of this type of OsII arene iminopyridine iodido complex acting as a catalyst in transfer hydrogenation. Although the asymmetric reduction of imines by RuII complexes has been studied in some detail, the mechanism of the reaction, in contrast to ketone reduction, is unclear. A recent report suggests that the reduction takes place through an “open” transition state in which binding to the N–H of the complex (typical for ketone reduction) is not required. This is supported by experiments conducted on stoichiometric reduction systems and also by molecular modeling. A similar mode of reduction has been proposed for enzyme-bound imine reductions.69, 70 The proposed mechanism retains the CH–π interaction that has been proposed for similar systems, although it is not clear whether this is operating in the current system.

Discussion

Crystal structures: Only one chiral configuration at the OsII center was observed in the X-ray crystal structures of chiral-at-OsII iminopyridine complexes 1, 2, 3, and 4, a fact that is consistent with the indication from the 1H NMR data. Thus, the use of two enantiomeric ligands in this work for the crystallization of pure diastereomers allowed us to successfully isolate two pairs of enantiomers (1, 3 and 2, 4, respectively). These results differ markedly from our previous findings on the OsII iminopyridine complex [Os(η6-p-cym)(Impy-OH)I]PF6, whose X-ray crystal structure showed a racemic mixture of enantiomers, (SOs)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(Impy-OH)I]PF6 and (ROs)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(Impy-OH)I]PF6.14 Chiral resolution of the second set of enantiomers in solution was hampered by their low solubility.

The assignment of chirality for the two pairs of osmium diastereomers 1/3 and 2/4 is consistent with their complementary CD spectra (Figure 2). It is apparent that the absolute stereochemical arrangements of the ligands around the osmium center in the complexes with the same chelating ligand 1 and 2 (chelating ligand=(S)-ImpyMe), 3 and 4 (chelating ligand=(R)-ImpyMe) are similar. These complexes do not exhibit the intramolecular “β-phenyl effect” found in previously reported organometallic arene complexes derived from similar chiral ligands. This stabilizing effect consists of an edge-to-face CH–π attractive interaction between the arene hydrogen atoms and a phenyl group from the optical active ligand, consequently giving rise to the thermodynamic product. Most of the published examples of diastereomeric RuII and OsII arene complexes showing the “β-phenyl effect” are neutral complexes71, 72 or contain different counterions (for example, ClO4−, Cl−, PF6−).72

The crystal structures of compounds 1–4 show the phenyl substituent from the ImpyMe ligand orientated downwards in order to avoid steric interactions with the p-cymene. A structural difference found between the chlorido and iodido complexes is the spatial arrangement of the methyl substituent from the ImpyMe ligand with respect to the monodentate ligand. The methyl group is directed towards the halide ligand in the chlorido complexes, 1 and 3, but it points in the opposite direction in the iodido analogues, 2 and 4, probably owing to steric repulsion by the bulky coordinated iodide. It is notable that in the chlorido complexes, an intermolecular non-classical *C–H⋅⋅⋅F bond interaction between the PF6− counterion and the hydrogen atom attached to the chiral carbon atom of the iminopyridine ligand is observed, whereas in the case of the iodido analogues this interaction occurs with the imine hydrogen. Additionally the PF6− anion hydrogen bonds to the p-cymene ligand and the pyridine ring of the ImpyMe ligand (Tables 1 and 2).

Regarding the thermodynamic/kinetic origin of the crystallized products, equilibration between the diastereomers at ambient temperature can be a fast process in which the thermodynamic product is obtained as the major epimer in solution.51 The equilibrium constant and configurational lability at the metal center depend on the temperature and the solvent, and some ruthenium arene complexes have a stable metal configuration even at high temperatures.26, 55 Several 1H NMR kinetic studies carried out by Brunner et al. on configurationally labile RuII and OsII half-sandwich diastereomers concluded that at low temperatures (193–195 K)29, 73 the major epimer (thermodynamic product) exists as the only compound in solution. An increase in temperature (223–294 K) favors the formation of the kinetic diastereomer, the percentage of which is higher at higher temperatures. Frequently the crystallization of these diastereomeric mixtures in solution gives rise to single crystals that contain only the less soluble diastereomer.

Taking all this into account, complexes 1, 2, 3, and 4 can be considered as the kinetic products of the reaction as well as the less soluble epimers at the temperature at which their crystallization from methanol took place (277 K). Few examples of OsII half-sandwich complexes crystallized as diastereomerically pure compounds have been reported.29, 67, 73

Circular dichroism: The CD spectra of the pairs of enantiomers (SOs,SC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)Cl]PF6 (1) and (ROs,RC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)Cl]PF6 (3), (SOs,SC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)I]PF6 (2) and (ROs,RC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)I]PF6 (4) showed several absorption bands with maximum intensities in the range 220–350 nm. A shoulder around 340 nm is also observed in spectra of the chlorido compounds, 1 and 3. These bands may be attributable to π→π* and n→π* transitions of the coordinated chiral iminopyridine ligand. Additionally, both pairs of enantiomers displayed two broad bands of lower intensity between 360–550 nm due to metal-based transitions. The opposite Cotton effects observed for 1 and 2 compared to 3 and 4, respectively, Figure 2, indicate that they are two pairs of mirror-image complexes.

Aqueous configuration stability: There was no epimerization at the OsII center during a 24 h incubation at 310 K of both the chlorido, 1 and 3, and iodido, 2 and 4, diastereomeric OsII iminopyridine arene complexes under biologically relevant conditions. This suggests that they are stable enough to allow further investigations of the effects of chirality of the osmium metal center on biological activity. As aquation and nucleophilic substitution of the metal–halide bond are involved in the general mechanism associated with DNA binding for RuII and OsII arene anticancer complexes,74 the mechanism of anticancer activity of these inert OsII arene iminopyridine iodido complexes is unlikely to involve DNA as a target in contrast to some previously reported OsII arene complexes.74

Density functional theory calculations: It is apparent that the synthetic route used for all the four osmium arene iminopyridine halido complexes can give rise to both R and S configurations at Os. To compare the thermodynamic stabilities of the diastereomers, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to optimize the geometry and calculate energies. These calculations were run at the B3LYP/LANL2DZ/6-31G** level in gas phase by using Gaussian 03.

For the two osmium chlorido complexes, the sequence of thermodynamic stability was: 3 (ROs,RC)>1 (SOs,SC)>(SOs,RC) = (ROs,SC) configuration. According to computational results, the 1 configuration is only 0.043 kJ mol−1 less stable than 3, whereas the (ROs,SC) and (SOs,RC) configurations are similar and 6.93 kJ mol−1 less stable than 1. For the two osmium iodido complexes, the sequence of thermodynamic stability follows the order: (SOs,RC) configuration>(ROs,SC) configuration>2 (SOs,SC)=4 (ROs,RC). According to the calculated energies, the (ROs,SC) configuration is only 0.002 kJ mol−1 less stable than the (SOs,RC) configuration, whereas 2 and 4 are 10.06 kJ mol−1 less stable than the (ROs,SC) configuration. Although the differences in energy are small, the computational results indicate that 1 and 3 are the thermodynamically favored isomers, while 2 and 4 are not thermodynamically favored isomers in terms of the chirality at osmium. Their separation may arise from solubility differences between the epimers.

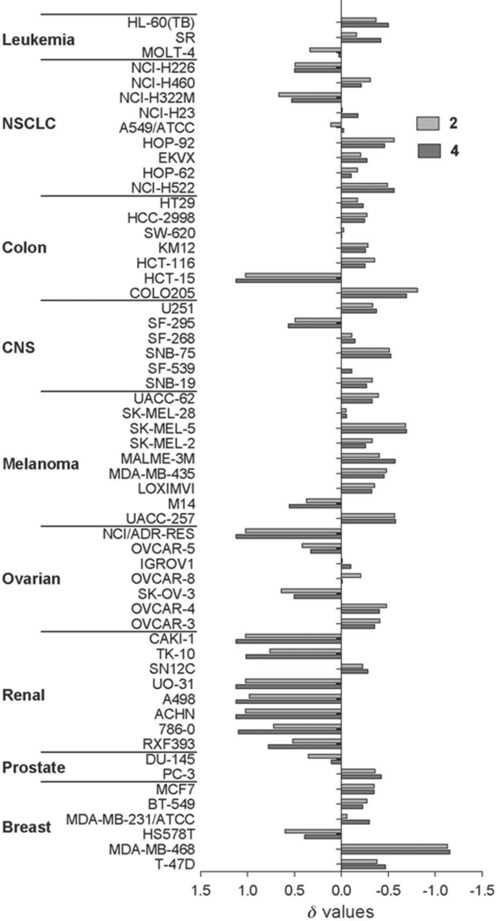

Anticancer activity: Further analysis of the in vitro anticancer efficacy of complexes 2 and 4 by the NCI revealed a broad spectrum of activity with promising selectivity towards melanoma and breast cancer cell lines. The breast cell line MDA-MB-468 showed particularly promising results with IC50 values in the sub-micromolar range (703 nM for 2 and 530 nM for 4). Also notable is the low selectivity of 2 and 4 for renal cancer cell lines (Figure 3), with IC50>100 μM for most of the renal cell lines in the NCI-60 screening.

Figure 3.

Overlay of mean graph for OsII arene iodido iminopyridine complexes 2 and 4 based on IC50 values from 60-cell-line screening (57 actual) by the National Cancer Institute Developmental Therapeutics Program. The average line represents the mean IC50 values for these compounds; bars pointing to the right indicate higher activity and to the left indicate lower activity compared with the mean value. NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer; CNS = central nervous system.

The COMPARE algorithm is an open tool developed by the NCI to quantify directly the similarity in cell line sensitivity between compounds.64 Each NCI-60 mean graph is taken as a fingerprint for the compound and is quantitatively compared to mean graphs for other compounds, producing a Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC) between −1 and 1 as a similarity measure. This method has been used successfully to predict mechanisms of action of emerging drugs by highlighting similarity in mean graph fingerprints to drugs of known mechanism in the NCI databases.75

A single analysis using the COMPARE algorithm for each complex against the NCI/DTP (Developmental Therapeutics Program) Standard Agents Database, housing 171 known anticancer compounds, was conducted.76 The results provide preliminary indications of a possible mechanism of action based on a correlation of the NCI 60-cell-line patterns of sensitivity.77 The three endpoints (IC50, TGI, and LC50) were used in the algorithm and those agents in the database with the highest PCC values were analyzed (Tables S2–S4). The highest PCC value for each endpoint for both complexes 2 and 4 was for vinblastine sulfate, an inhibitor of tubulin polymerization. The quantitative analysis of the selectivity patterns between complexes 2 and 4 gave PCC values of 0.973 (IC50), 0.969 (TGI), and 0.976 (LC50) for different endpoints, indicating that 2 and 4 may share high similarity in their mechanisms. This is demonstrated in the mean graphs in Figure 3, where the pattern of sensitivity is almost identical. We assessed whether cisplatin showed a significant correlation to either 2 or 4, and found that this comparison produced a PCC value of −0.298. This negative value highlights that cisplatin has a distinctly different pattern of selectivity and suggests a different mechanism of action from complexes 2 and 4 (Table 6).

Table 6.

COMPARE analysis showing the highest correlations for complexes 2 and 4 with known anticancer drugs, as indicated by their PCC (Pearson′s correlation coefficient) values.

| Complex | PCC | Name | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| (SOs,SC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)I]PF6 (2) | 0.743 | vinblastine sulfate | antimicrotubule agent |

| (ROs,RC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)I]PF6 (4) | 0.754 | vinblastine sulfate | antimicrotubule agent |

The prevention of polymerization of microtubules in vitro was investigated by assessing whether OsII complexes 2 and 4 interact directly with tubulin. Relative concentrations of OsII complexes (10 μM) were selected according to the IC50 values from the cell tests. Purified, unpolymerized tubulin was incubated with OsII compounds and the polymerization process monitored at 310 K for 60 min. Taxol and colchicines were used as positive controls for polymerization facilitation and inhibition, respectively.78 Under these conditions, no inhibition of polymerization by OsII complexes was observed (see the Supporting Information, Figure S3), a fact that indicated that the mechanism of action does not involve direct interaction with tubulin.

Conclusion

There are few reported studies of isolated organometallic complexes with chirally pure OsII centers. In this work, through incorporation of an additional chiral center into a chelated iminopyridine ligand, we have separated four chiral OsII arene anticancer complexes by fractional crystallization: two iodido complexes, (SOs,SC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)I]PF6 (2, containing (S)-ImpyMe: N-(2-pyridylmethylene)-(S)-1-phenylethylamine), and (ROs,RC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)I]PF6 (4, containing (R)-ImpyMe: N-(2-pyridylmethylene)-(R)-1-phenylethylamine), and the two chlorido derivatives (SOs,SC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)Cl]PF6 (1) and (ROs,RC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)Cl]PF6 (3). Their X-ray crystal structures and CD spectra verified their mirror image configurations. Interestingly, the two iodido OsII arene complexes, 2 and 4, showed more promising anticancer activity against A2780 human ovarian cancer cell line and the NCI 60-cell-line screening compared with the two chlorido OsII arene complexes, 1 and 3. Quantitative analysis of the NCI 60-cell-line screen using the COMPARE algorithm showed that the two potent iodido complexes have surprisingly similar selectivity patterns to one another and to an anti-microtubule drug, vinblastine sulfate. However, no direct effect towards tubulin polymerization was found for 2 and 4, a fact that may indicate a different or indirect mechanism of action. Other than anticancer activity, 2 and 4 also demonstrated potential as hydrogenation transfer catalysts for imine reduction.

Acknowledgments

We thank the ERC (grant no. 247450 BIOINCMED), EPSRC, and Science City/EU ERDF/AWM (MaXis mass spectrometer and the X-ray diffractometer) for funding. M.J.R. thanks Fundación Barrié (Spain) for her postdoctoral fellowship. L.S. thanks the MICINN of Spain for the Ramón y Cajal Fellowship RYC-2011–07787. We thank colleagues in the EC COST Action D39 and CM1105 for stimulating discussions, Dr. Rob Cross for the help with the test of interactions with the process of tubulin polymerizations, Dr. Patrycja Kowalska and Prof. Alison Rodger for providing facilities for circular dichroism, Dr. Michael Khan (Life Sciences) for provision of facilities for cell culture, and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) for 60-cancer-cell-line screening.

Experimental Section

Starting materials: OsCl3⋅3H2O was purchased from Alfa-Aesar. Ethanol and methanol were dried over Mg/I2 or anhydrous quality was used (Aldrich). All other reagents were obtained from commercial suppliers and used as received. The preparations of the starting materials [{Os(η6-p-cym)Cl2}2] and [{Os(η6-p-cym)I2}2] have been previously reported.57 The synthesis and purification of the chiral pure iminopyridine ligands, (S)-ImpyMe: N-(2-pyridylmethylene)-(S)-1-phenylethylamine, (R)-ImpyMe: N-(2-pyridylmethylene)-(R)-1-phenylethylamine, were carried out according to the literature method.45 The A2780 human ovarian carcinoma cell line was purchased from European Collection of Animal Cell Cultures (Salisbury, UK), RPMI-1640 media and trypsin were purchased from Invitrogen, bovine serum from Biosera, penicillin, streptomycin, trichloroacetic acid (TCA), and sulforhodamine B (SRB) from Sigma–Aldrich, and tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane from Formedium.

Syntheses and characterization: All the OsII compounds were synthesized and crystallized by a general method that is described for compound 1. Single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained for all these compounds and were used for all the chemical and biological tests.

(SOs,SC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)Cl]PF6 (1): [{Os(η6-p-cym)Cl2}2] (50.0 mg, 0.063 mmol) was dissolved in methanol (20 mL) at 313 K. (S)-ImpyMe (26.9 mg, 0.12 mmol) in methanol (10 mL) was added drop-wise. The solution changed color from orange to red immediately, and was stirred at ambient temperature (ca. 293 K) for 2 h. Ammonium hexafluorophosphate (41.2 mg, 0.24 mmol) was added. Then the solution was left in a fridge at 277 K for 24 h. Dark brown colored single crystals were obtained and were collected by filtration, washed with cold ethanol and diethyl ether, and dried under vacuum. Yield (single crystals): 54.0 mg (58.7 %); 1H NMR (400 MHz, (CD3)2CO): δ= 9.59 (d, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 9.32 (s, 1 H), 8.47 (d, J=8 Hz, 1 H), 8.32 (t, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 7.73 (t, J=6 Hz, 2 H), 7.62–7.55 (m, 3 H), 6.55 (d, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 6.16 (d, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 6.06 (qd, J=6, 8 Hz, 1 H), 5.89 (d, J=6 Hz, 2 H), 2.65 (s, 3 H), 2.54–2.42 (m, 1 H), 2.38 (s, 6 H), 1.93 (d, J=6 Hz, 3 H), 1.11 (d, J = 7 Hz, 3 H), 0.89 ppm (d, J = 7 Hz, 3 H); ESI-MS: m/z calcd for C24H28ClN2Os: 571.2 [M]+; found 571.1; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C24H28ClF6N2OsP: C 40.31, H 3.95, N 3.92; found: C 40.30, H 3.87, N 3.90; CD (CH3OH): λmax (Δε): 412 (+42), 318 (−58), 288 (+64), 256 (−78), 220 nm (−100 mol−1 cm−1). The brown single crystals of 1 were suitable for study by X-ray diffraction.

(SOs,SC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)I]PF6 (2): Prepared by following the same method as for complex 1. Yield (single crystals): 28.9 mg (33.8 %); 1H NMR (400 MHz, (CD3)2CO): δ= 9.57 (d, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 9.43 (s, 1 H), 8.48 (d, J=8 Hz, 1 H), 8.25 (t, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 7.77 (t, J=6 Hz, 2 H), 7.52–7.48 (m, 3 H), 6.49 (d, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 6.26 (d, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 6.08 (qd, J=6, 8 Hz, 1 H), 6.04 (d, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 5.83 (d, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 2.84 (s, 3 H), 2.67–2.60 (m, 1 H), 2.65 (s, 6 H), 2.13 (d, J=7 Hz, 3 H), 1.10 (d, J = 7 Hz, 3 H), 0.91 ppm (d, J = 7 Hz, 3 H); ESI-MS: m/z calcd for C24H28IN2Os: 663.1 [M]+; found 663.0. elemental analysis calcd (%) for C24H28F6IN2OsP: C 35.74, H 3.50, N 3.47; found: C 35.76, H 3.53, N 3.36; CD (CH3OH): λmax (Δε): 450 (−9), 313 (−57), 285 (+27), 268 (−30), 247 (+82), 221 nm (+51 mol−1 cm−1). The brown single crystals grown from a cooled methanol solution (277 K) were suitable for X-ray diffraction studies.

(ROs,RC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)Cl]PF6 (3): Prepared by following the same method as for complex 1. Yield (single crystals): 25.5 mg (27.7 %); 1H NMR (400 MHz, (CD3)2CO): δ = 9.59 (d, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 9.32 (s, 1 H), 8.47 (d, J=8 Hz, 1 H), 8.32 (t, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 7.73 (t, J=6 Hz, 2 H), 7.62–7.55 (m, 3 H), 6.55 (d, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 6.16 (d, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 6.06 (qd, J=6, 8 Hz, 1 H), 5.89 (d, J=6 Hz, 2 H), 2.65 (s, 3 H), 2.54–2.42 (m, 1 H), 2.38 (s, 6 H), 1.93 (d, J=6 Hz, 3 H), 1.11 (d, J = 7 Hz, 3 H), 0.89 ppm (d, J = 7 Hz, 3 H); ESI-MS: m/z calcd for C24H28ClN2Os: 571.2 [M]+; found 571.1; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C24H28ClF6N2OsP: C 40.31, H 3.95, N 3.92; found: C 40.16, H 3.80, N 3.90;. CD (CH3OH): λmax (Δε): 412 (−41), 318 (+58), 288 (−62), 256 (+78), 220 nm (+99 mol−1 cm−1). Orange single crystals suitable for X-ray crystallography were obtained after cooling a portion of the methanol solution at 277 K.

(ROs,RC)-[Os(η6-p-cym)(ImpyMe)I]PF6 (4): Prepared by following the same method as for complex 1. Yield (single crystals): 25.2 mg (35.6 %); 1H NMR (400 MHz, (CD3)2CO): δ= 9.57 (d, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 9.43 (s, 1 H), 8.48 (d, J=8 Hz, 1 H), 8.25 (t, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 7.77 (t, J=6 Hz, 2 H), 7.52–7.48 (m, 3 H), 6.49 (d, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 6.26 (d, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 6.08 (qd, J=6, 8 Hz, 1 H), 6.04 (d, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 5.83 (d, J=6 Hz, 1 H), 2.84 (s, 3 H), 2.67–2.60 (m, 1 H), 2.65 (s, 6 H), 2.13 (d, J=7 Hz, 3 H), 1.10 (d, J = 7 Hz, 3 H), 0.91 ppm (d, J = 7 Hz, 3 H); ESI-MS: m/z calcd for C24H28IN2Os: 663.1 [M]+; found 663.0; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C24H28F6IN2OsP: C 35.74, H 3.50, N 3.47; found: C 35.63, H 3.47, N 3.33; CD (CH3OH): λmax (Δε): 450 (+9), 313 (+56), 285 (−27), 268 (+30), 247 (−78), 222 nm (−47 mol−1 cm−1). Dark brown single crystals suitable for X-ray crystallography were obtained after cooling a portion of the methanol solution at 277 K.

Instrumentation

NMR spectroscopy: 1H NMR spectra were acquired in 5 mm NMR tubes at 298 K on either Bruker DPX-400, Bruker DRX-500, or Bruker AV II 700 spectrometers. 1H NMR chemical shifts were referenced to [D6]acetone (2.09 ppm). All data processing was carried out using MestReC or TOPSPIN version 2.0 (Bruker U.K. Ltd.).

Electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry (ESI-MS): Spectra were obtained by preparing the samples in 50 % CH3CN and 50 % H2O (v/v) and infusing into the mass spectrometer (Varian 4000). The mass spectra were recorded with a scan range of m/z 500–1000 for positive ions.

Elemental analysis: Elemental analysis (carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen) was carried out through Warwick Analytical Service using an Exeter analytical elemental analyzer (CE440).

pH* measurements: pH* (pH meter reading from D2O solution without correction for effects of deuterium on glass electrode) values were measured at ambient temperature before the NMR spectra were recorded, using a Corning 240 pH meter equipped with a micro-combination electrode calibrated with Aldrich buffer solutions at pH 4, 7, and 10.

X-ray crystallography: X-ray diffraction data for 1, 2, 3, and 4 were obtained on an Oxford Diffraction Gemini four-circle system with a Ruby CCD area detector using MoKα radiation.80 Absorption corrections were applied by using ABSPACK. The crystals were mounted in oil and held at 100(2) K with the Oxford Cryosystem Cryostream Cobra. The structures were solved by direct methods using SHELXS (TREF) with additional light atoms found by Fourier methods81 and refined against F2 using SHELXL 97.82 Hydrogen atoms were added at calculated positions and refined using a riding model with freely rotating methyl groups. Anisotropic displacement parameters were used for all non-H atoms; H atoms were given isotropic displacement parameters equal to 1.2 (or 1.5 for methyl hydrogen atoms) times the equivalent isotropic displacement parameter of the atom to which the H atom is attached. The graphics for the crystal structures were made with Mercury 2.4. CCDC-941759 http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/cgi-bin/catreq.cgi(1), 941760 http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/cgi-bin/catreq.cgi(2), 941761 http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/cgi-bin/catreq.cgi(3), and 941762 http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/cgi-bin/catreq.cgi(4) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Cell cultures: A2780 human ovarian cancer cell lines (ECACC, Salisbury, UK) were cultured in RPMI 1640 cell culture medium supplemented with 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mm l-glutamine, and 10 % fetal bovine serum.

Circular dichroism: Circular dichroism spectra of 1, 2, 3, and 4 were recorded on a J-815 circular dichroism spectropolarimetrer (Jasco, UK) at ambient temperature (ca. 293 K). The spectra were determined for all the samples at a concentration of 1 mM in methanol using a quartz cuvette of 0.1 cm path length, scan speed of 200 nm min−1, 1 nm band width, 0.2 nm data pitch, and 0.5 s of response time.

Methods

Aquation: Solutions of 1, 2, 3, or 4 in 10 % CD3OD/90 % D2O phosphate buffer (v/v) were prepared by dissolution in CD3OD followed by a dilution with D2O phosphate buffer (pH*=7.2). NMR spectra were recorded after 24 h of incubation at 310 K. The extent of aquation was determined from 1H NMR peak integrals.

Determination of A2780 IC50 values: The method was similar to that previously described.57

NCI 60-cell-line screen: The cells were treated for 48 h at five concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 100 μM. Three endpoints were calculated: IC50 (the concentration that inhibits cell growth by 50 %); TGI (the concentration that inhibits cell growth by 100 %); LC50 (the concentration that kills 50 % of the original cells); MG-MID (full-panel mean-graph midpoint). Cisplatin data were from NCI/DTP screening: Oct 2009, 48 h incubation.

Data evaluation, mean graph analysis, and COMPARE analysis: Anti-proliferative efficacies of test compounds in both assays were described by inhibitory concentrations (IC50 values), reflecting concentration-dependent cytotoxicity. Complexes 2 and 4 were selected for study in the human tumor 60-cell-line panel of the Developmental Therapeutics Program (DTP) of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), a panel that includes nine tumor-type subpanels. The cells were treated for 48 h at five concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 100 μM. Three endpoints were calculated: IC50 (the concentration that inhibits cell growth by 50 %); TGI (the concentration that inhibits cell growth by 100 %); LC50 (the concentration that kills 50 % of the original cells); MG-MID (full-panel mean-graph midpoint). The MG-MID value therefore represents an antiproliferative fingerprint of a compound. The COMPARE analysis was carried out using the NCI/DTP Standard Agents database, a collection of 171 known anticancer compounds, to provide preliminary indications on a possible mechanism of action based on data obtained in a panel of tumor cell lines tested in the 60-cell-line screen in vitro.77 Compounds that have a high correlation coefficient with known drugs have generally been found to have similar mechanisms of action. High correlation (ρ ≥ 0.6) to a specific standard agent indicated a similar anticancer mechanism of action. Low correlations to all standard agents indicated a novel anticancer mechanism of action not represented by the standard agent database.

Tubulin polymerization assay: A cytoskeleton tubulin polymerization assay kit (catalog no. BK004) was used in the tubulin polymerization study. Briefly, 10 μL of general tubulin buffer (80 mM PIPES, pH 6.9, 2 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 mM EGTA) containing osmium compound, colchicine, or taxol was pipetted into the pre-warmed 96-well microplate. Tubulin (defrosted to room temperature from 213 K and then placed on ice before use) was diluted with tubulin polymerization buffer with 1 mM GTP to a final concentration of 4 mg mL−1. Diluted tubulin (100 μL) was added into the wells containing 2, 4, colchicine, or taxol. Diluted tubulin (100 μL) mixed with general tubulin buffer (10 μL) served as control. The absorbance at 340 nm was read immediately with a Tecan microplate reader.

Catalyst for imine reduction: A mixture of imine (25 mg), catalyst (1 mol %) in FA (formic acid)/TEA (triethylamine) (5:2, 0.1 mL) was stirred at 301–333 K for 18–41 h under an inert atmosphere. For reaction monitoring, an aliquot of the reaction mixture was filtered through a plug of silica and analyzed by GC for percentage conversion. Enantiomeric excess and conversion were determined by GC analysis (chrompaccyclodextrin-β-236 M-19, 50 m×0.25 mm×0.25 μm, T=443 K, P=15 psi, gas H2, imine 38.46 min, S isomer 35.12 min, R isomer 35.94 min).

Computational details: Geometry optimization calculations of 1, 2, 3, and 4 and their enantiomers were performed at the DFT level in the gas phase using Gaussian 03.83 The Becke three parameter hybrid functional and Lee–Yang–Parr’s gradient corrected correlation functional (B3LYP)84, 85 were employed together with the LanL2DZ86 effective core potential for the Os atom and the 6-31G** basis set for all other atoms.87 The nature of all stationary points was confirmed by normal mode analysis.

Supporting Information

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/chem.201302183.

References

- De Camp WH. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 1993;11:1167–1172. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(93)80100-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato RJ, Loughnan MS, Flynn E, Folkman J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:4082–4085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.4082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal S, Mehta J, Desikan R, Ayers D, Roberson P, Eddlemon P, Munshi N, Anaissie E, Wilson C, Dhodapkar M, Zeldis J, Siegel D, Crowley J, Barlogie B. New Engl. J. Med. 1999;341:1565–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911183412102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser G, Ott I, Metzler-Nolte N. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:3–25. doi: 10.1021/jm100020w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartinger CG, Dyson PJ. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:391–401. doi: 10.1039/b707077m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry NPE, Sadler PJ. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:3264–3279. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15300a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindo SS, Mancino AM, Braymer JJ, Liu Y, Vivekanandan S, Ramamoorthy A, Lim MH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:16663–16665. doi: 10.1021/ja907045h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronconi L, Sadler PJ. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2007;251:1633–1648. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno V, Font-Bardia M, Calvet T, Lorenzo J, Avilés FX, Garcia MH, Morais TS, Valente A, Robalo MP. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2011;105:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanif M, Meier SM, Kandioller W, Bytzek A, Hejl M, Hartinger CG, Nazarov AA, Arion VB, Jakupec MA, Dyson PJ, Keppler BK. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2011;105:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso F, Rossi M, Benson A, Opazo C, Freedman D, Monti E, Gariboldi MB, Shaulky J, Marchetti F, Pettinari R, Pettinari C. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:1072–1081. doi: 10.1021/jm200912j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noffke AL, Habtemariam A, Pizarro AM, Sadler PJ. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:5219–5246. doi: 10.1039/c2cc30678f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Habtemariam A, Basri AMBH, Braddick D, Clarkson GJ, Sadler PJ. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:10553–10562. doi: 10.1039/c1dt10937e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Romero MJ, Habtemariam A, Snowden ME, Song L, Clarkson GJ, Qamar B, Pizarro AM, Unwin PR, Sadler PJ. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:2485–2494. [Google Scholar]

- Rijt SHv, Kostrhunova H, Brabec V, Sadler PJ. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011;22:218–226. doi: 10.1021/bc100369p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurzwernhart A, Kandioller W, Bartel C, Bachler S, Trondl R, Muhlgassner G, Jakupec MA, Arion VB, Marko D, Keppler BK, Hartinger CG. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:4839–4841. doi: 10.1039/c2cc31040f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanenko IN, Casini A, Edafe F, Novak MS, Arion VB, Dyson PJ, Jakupec MA, Keppler BK. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:12669–12679. doi: 10.1021/ic201801e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginzinger W, Mühlgassner G, Arion VB, Jakupec MA, Roller A, Galanski M, Reithofer M, Berger W, Keppler BK. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:3398–3413. doi: 10.1021/jm3000906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sava G, Jaouen G, Hillard EA, Bergamo A. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:8226–8234. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30075c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paira P, Chow MJ, Venkatesan G, Kosaraju VK, Cheong SL, Klotz K-N, Ang WH, Pastorin G. Chem. Eur. J. 2013;19:8321–8330. doi: 10.1002/chem.201203291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atilla-Gokcumen G, Di Costanzo L, Meggers E. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2011;16:45–50. doi: 10.1007/s00775-010-0699-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanck S, Geisselbrecht Y, Kraling K, Middel S, Mietke T, Harms K, Essen L-O, Meggers E. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:9337–9348. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30940h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanck S, Maksimoska J, Baumeister J, Harms K, Marmorstein R, Meggers E. Angew. Chem. 2012;124:5335–5338. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanck S, Maksimoska J, Baumeister J, Harms K, Marmorstein R, Meggers E. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:5244–5246. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner H. Angew. Chem. 1969;81:395–396. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1969;8:382–383. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner H, Aclasis J, Langer M, Steger W. Angew. Chem. 1974;86:864–865. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner H, Aclasis J, Langer M, Steger W. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1974;13:810–811. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner H, Oeschey R, Nuber B. Organometallics. 1996;15:3616–3624. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Ferri M-G, Hartinger CG, Eichinger RE, Stolyarova N, Severin K, Jakupec MA, Nazarov AA, Keppler BK. Organometallics. 2008;27:2405–2407. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona D, Viguri F, Pilar Lamata M, Ferrer J, Bardají, Lahoz FJ, García-Orduña P, Oro LA. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:10298–10308. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30976a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner H, Zwack T, Zabel M, Beck W, Böhm A. Organometallics. 2003;22:1741–1750. [Google Scholar]

- Smalley KSM, Contractor R, Haass NK, Kulp AN, Atilla-Gokcumen GE, Williams DS, Bregman H, Flaherty KT, Soengas MS, Meggers E, Herlyn M. Cancer Res. 2007;67:209–217. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpin KJ, Cammack SM, Clavel CM, Dyson PJ. Dalton Trans. 2013;42:2008–2014. doi: 10.1039/c2dt32333h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier SM, Hanif M, Adhireksan Z, Pichler V, Novak M, Jirkovsky E, Jakupec MA, Arion VB, Davey CA, Keppler BK, Hartinger CG. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:1837–1846. [Google Scholar]

- Boff B, Gaiddon C, Pfeffer M. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:2705–2715. doi: 10.1021/ic302779q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filak LK, Göschl S, Heffeter P, Ghannadzadeh Samper K, Egger AE, Jakupec MA, Keppler BK, Berger W, Arion VB. Organometallics. 2013;32:903–914. doi: 10.1021/om3012272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanenko IN, Krokhin AA, John RO, Roller A, Arion VB, Jakupec MA, Keppler BK. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:7338–7347. doi: 10.1021/ic8006958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büchel GE, Stepanenko IN, Hejl M, Jakupec MA, Keppler BK, Heffeter P, Berger W, Arion VB. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012;113:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni W-X, Man W-L, Yiu S-M, Ho M, Cheung MT-W, Ko C-C, Che C-M, Lam Y-W, Lau T-C. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:1582–1588. [Google Scholar]

- Naota T, Takaya H, Murahashi S-I. Chem. Rev. 1998;98:2599–2660. doi: 10.1021/cr9403695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyori R, Hashiguchi S. Acc. Chem. Res. 1997;30:97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Villa-Marcos B, Xiao J. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:9773–9785. doi: 10.1039/c1cc12326b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSkimming A, Colbran SB. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013. advance article.

- Faller JW, Lavoie AR. Organometallics. 2002;21:3493–3495. [Google Scholar]

- Faller JW, Lavoie AR. Org. Lett. 2001;3:3703–3706. doi: 10.1021/ol016641w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainer IW, Granvil CP. Ther. Drug Monit. 1993;15:570–580. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199312000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto S, Dragna JM, Anslyn EV. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:227–232. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock AFA, Sadler PJ. Chem. Asian J. 2008;3:1890–1899. doi: 10.1002/asia.200800149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecomte C, Dusausoy Y, Protas J, Tirouflet J, Dormond A. J. Organomet. Chem. 1974;73:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley K, Baird MC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:6598–6599. [Google Scholar]

- An H-Y, Wang E-B, Xiao D-R, Li Y-G, Su Z-M, Xu L. Angew. Chem. 2006;118:918–922. [Google Scholar]

- An H-Y, Wang E-B, Xiao D-R, Li Y-G, Su Z-M, Xu L. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:904–908. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner H, Muschiol M, Tsuno T, Takahashi T, Zabel M. Organometallics. 2010;29:428–435. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner H. Angew. Chem. 1999;111:1248–1263. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:1194–1208. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990503)38:9<1194::AID-ANIE1194>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Parkinson JA, Nováková O, Bella J, Wang F, Dawson A, Gould R, Parsons S, Brabec V, Sadler PJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:14623–14628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2434016100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganter C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2003;32:130–138. doi: 10.1039/b205996g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner H, Zwack T. Organometallics. 2000;19:2423–2426. [Google Scholar]

- Consiglio G, Morandini F. Chem. Rev. 1987;87:761–778. [Google Scholar]

- Shnyder SD, Fu Y, Habtemariam A, van Rijt SH, Cooper PA, Loadman PM, Sadler PJ. MedChemComm. 2011;2:666–668. [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Habtemariam A, Pizarro AM, van Rijt SH, Healey DJ, Cooper PA, Shnyder SD, Clarkson GJ, Sadler PJ. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:8192–8196. doi: 10.1021/jm100560f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotze ACG, Kariuki BM, Hannon MJ. Angew. Chem. 2006;118:4957–4960. [Google Scholar]

- Hotze ACG, Kariuki BM, Hannon MJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:4839–4842. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell U, Kerchoffs JMCA, Castiñeiras RPM, Hicks MR, Hotze ACG, Hannon MJ, Rodger A. Dalton Trans. 2008:667–675. doi: 10.1039/b711080d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velders AH, van der Schilden K, Hotze ACG, Reedijk J, Kooijman H, Spek AL. Dalton Trans. 2004:448–455. doi: 10.1039/b313182c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotze A, Caspers S, Vos D, Kooijman H, Spek A, Flamigni A, Bacac M, Sava G, Haasnoot J, Reedijk J. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2004;9:354–364. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0531-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougan SJ, Habtemariam A, McHale SE, Parsons S, Sadler PJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:11628–11633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800076105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paull KD, Shoemaker RH, Hodes L, Monks A, Scudiero DA, Rubinstein L, Plowman J, Boyd MR. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1088–1092. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.14.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbeck SL, Collins JM, Doroshow JH. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1451–1460. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J, Baker DC. Org. Lett. 1999;1:841–843. doi: 10.1021/ol990098q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Pettman A, Bacsa J, Xiao J. Angew. Chem. 2010;122:7710–7714. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Pettman A, Bacsa J, Xiao J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:7548–7552. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona D, Lahoz FJ, García-Orduña P, Oro LA, Lamata MP, Viguri F. Organometallics. 2012;31:3333–3345. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona D, Vega C, Lahoz FJ, Elipe S, Oro LA, Lamata MP, Viguri F, García-Correas R, Cativiela C, López-Ram de Víu MP. Organometallics. 1999;18:3364–3371. [Google Scholar]

- Soni R, Cheung FK, Clarkson GC, Martins JED, Graham MA, Wills M. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011;9:3290–3294. doi: 10.1039/c1ob05208j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringenberg M, Ward TR. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:8470–8476. doi: 10.1039/c1cc11592h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath RK, Nethaji M, Chakravarty AR. Polyhedron. 2002;21:1929–1934. [Google Scholar]

- Rath RK, Gowda GAN, Chakravarty AR. Proc. Indian Acad. Sci. 2002;114:461–472. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner H, Zwack T, Zabel M. Polyhedron. 2003;22:861–865. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H-K, Sadler PJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011;44:349–359. doi: 10.1021/ar100140e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J, Khan SN, Harvey I, Merrick W, Pelletier J. RNA. 2004;10:528–543. doi: 10.1261/rna.5200204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker RH. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:813–823. doi: 10.1038/nrc1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JK, Havaleshko DM, Cho H, Weinstein JN, Kaldjian EP, Karpovich J, Grimshaw A, Theodorescu D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:13086–13091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610292104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh HJC, Chrzanowska M, Brossi A. FEBS Lett. 1988;229:82–86. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Görmen M, Pigeon P, Top S, Hillard EA, Huché M, Hartinger CG, de Montigny F, Plamont M-A, Vessières A, Jaouen G. ChemMedChem. 2010;5:2039–2050. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201000286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CrysAlis PRO. Abington, Oxfordshire (UK): Oxford Diffraction Ltd; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick GM. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A. 1990;46:467–473. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick GM. SHELX97. Germany: University of Göttingen; 1997. Programs for Crystal Structure Analysis (Release 97–92) [Google Scholar]

- Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Montgomery JA, Vreven T, Kudin KN, Burant JC, Millam JM, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Barone V, Mennucci B, Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Klene M, Li X, Knox JE, Hratchian HP, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Ayala PY, Morokuma K, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Zakrzewski VG, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Strain MC, Farkas O, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cui Q, Baboul AG, Clifford S, Cioslowski J, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al-Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Challacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Gonzalez C, Pople JA. Gaussian, Inc. Wallingford CT: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Becke AD. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Phys. Rev. B. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay PJ, Wadt WR. J. Chem. Phys. 1985;82:270–283. [Google Scholar]

- McLean AD, Chandler GS. J. Chem. Phys. 1980;72:5639–5648. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.