Abstract

The transduction efficiency of adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors in various somatic tissues has been shown to depend heavily on the AAV type from which the vector capsid proteins are derived. Among the AAV types studied, AAV6 efficiently transduces cells of the airway epithelium, making it a good candidate for the treatment of lung diseases such as cystic fibrosis. Here we have evaluated the effects of various promoter sequences on transduction rates and gene expression levels in the lung. Of the strong viral promoters examined, the Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) promoter performed significantly better than a human cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter in the airway epithelium. However, a hybrid promoter consisting of a CMV enhancer, β-actin promoter and splice donor, and a β-globin splice acceptor (CAG promoter) exhibited even higher expression than either of the strong viral promoters alone, showing a 38-fold increase in protein expression over the RSV promoter. In addition, we show that vectors containing either the RSV or CAG promoter expressed well in the nasal and tracheal epithelium. Transduction rates in the 90% range were achieved in many airways with the CAG promoter, showing that with the proper AAV capsid proteins and promoter sequences, highly efficient transduction can be achieved.

INTRODUCTION

Vectors based on adeno-associated virus (AAV), a single-stranded DNA parvovirus, can promote persistent gene expression in dividing and nondividing cells in multiple somatic tissues of animals (Kessler et al., 1996; Xiao et al., 1996; Fisher et al., 1997; Halbert et al., 1997; Herzog et al., 1997, 1999). The ability to transduce nondividing cells is an important feature of AAV vectors for gene transfer to many tissues, including the lung, which have low rates of proliferation (Kauffman, 1980).

Transfer of therapeutic genes to the lung may provide a cure for diseases such as cystic fibrosis (CF), which affects 1 in 3,000 white births. Inactivating mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR), a chloride ion channel, result in gradual lung destruction, which is the major cause of morbidity. Although the normal CFTR protein has been localized to the apical surface of the airway epithelium and the submucosal glands beneath the epithelium (Engelhardt et al., 1992; Yankaskas et al., 1993), the airway is the site of microbial obstruction associated with mortality. This clinical manifestation provides the rationale for targeting the airway epithelium for CF gene therapy.

In contrast to vectors made with AAV type 2 capsids, those having AAV type 5 or 6 capsids show high transduction rates in airway epithelial cells, in a range that should be sufficient for treating lung disease (Seiler et al., 2006). The low level of airway expression from an AAV2 vector is consistent with the low level of heparan sulfate proteoglycans, a receptor for AAV2, on the apical surface of the airway that is exposed to the virus. Sialic acid is required for AAV5 gene transfer (Walters et al., 2001) and is an abundant sugar on the apical surface, consistent with the better performance of AAV5 compared with AAV2 in the airways. Several AAV types use sialic acid as an attachment factor. AAV4 and AAV5 use α2,3 O-linked and α2,3 N-linked sialic acid, respectively. It has been reported that AAV1 and AAV6 use both α2,3 and α2,6 N-linked sialic acids for binding and infection (Wu et al., 2006). However, there are differences. AAV6 binds to heparin and AAV1 does not (Halbert et al., 2001), and AAV6 is more efficient in liver transduction than AAV1 (Wu et al., 2006). A comparison of AAV6 and AAV1 in the lung has yet to be done. A comparison of AAV5 and AAV6 showed that whereas both vectors had high transduction rates in well-differentiated human airway epithelial cultures, they exhibited distinct cell type transduction profiles in mouse lung that were consistent with differences in receptor usage (Seiler et al., 2006). It is clear that other factors such as different secondary receptors and virus uncoating (Thomas et al., 2004) play a role in virus binding and tissue transduction efficiency.

Although receptor abundance is a factor in tissue-specific expression, other elements of the AAV vector can affect tissue-specific expression. Here we have studied gene expression in lung from AAV vectors containing various transcriptional regulatory elements in an attempt to augment lung-specific expression. We chose to use vectors having the AAV6 capsid because our previous in vivo experience comparing AAV types 2, 3, 5, and 6 indicated that the AAV6 capsid performed the best in the airway epithelium in vivo (Halbert et al., 2000, 2001; Seiler et al., 2006).

Our previous studies have used AAV vectors containing the Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) promoter. We tried to increase expression of such vectors encoding human placental alkaline phosphatase (AP) by replacing the RSV sequence with an immediate- early enhancer and promoter from a human cytomegalovirus (CMV). Surprisingly, we found that whereas both vectors expressed well in tissue culture cells and in alveolar cells in mice, the CMV promoter/enhancer performed poorly in the mouse airway epithelium compared to the RSV promoter/enhancer. We next tested a hybrid promoter/enhancer consisting of a CMV enhancer, the chicken β-actin promoter and splice donor, and a rabbit β-globin splice acceptor (CAG), and a derivative of it that did not contain the CMV sequences (AG). In this context, the CMV portion did not lower expression in the airway epithelium, but instead increased total lung AP activity by 38-fold over the RSV promoter. In addition to the various cell types transduced in the lung, we show that both the RSV and CAG promoter-containing vectors expressed well in the nasal and tracheal epithelium, providing other venues for assessing therapeutic protein function for lung diseases such as cystic fibrosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Human embryonic kidney 293 cells (CRL-1573; American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], Manassas, VA) and HTX cells (an approximately diploid subclone of human HT-1080 fibrosarcoma cells [CCL-121; ATCC]) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

AAV vector plasmids

The AAV2-based vector ARAP4 (Allen et al., 2000) expresses AP and contains the RSV promoter/enhancer, the AP cDNA, and simian virus 40 (SV40) polyadenylation sequences. The AAV2-based vector CWRZn (Halbert et al., 1997) expresses a nuclear-localizing β-galactosidase (nβ-Gal) and contains the RSV promoter and enhancers, a cDNA for nβ-Gal, and an AAV2 polyadenylation sequence. CWCZn (Halbert et al., 2000) and ACAP contain a human CMV immediate-early promoter and enhancer (HCMV IE1) from bases −727 to +77 relative to the RNA cap site (Boshart et al., 1985) in place of the RSV sequences. pACAGAP was constructed by replacing the RSV promoter in ARAP4 with the hybrid promoter/enhancer CAG (Niwa et al., 1991), which contains HCMV IE1 enhancer sequences from bases −598 to −218 relative to the RNA cap site (Boshart et al., 1985), the chicken β-actin promoter and first intron splice donor site, and the rabbit β-globin second intron splice acceptor site. The plasmid pAAGAP was derived by removing the CMV IE1 sequences from the CAG-containing vector plasmid pACAGAP. The plasmid pDGM6 (Gregorevic et al., 2004), which encodes adenovirus helper, AAV2 replication, and AAV6 packaging functions, was cotransfected with the vector plasmids to generate the AAV vectors. The AAV vector plasmids pARAP4, pACAP, pCWCZn, pCWRZn, pACAGAP, and pAAGAP were propagated in the bacterial strain SURE (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) or JC8111 (Boissy and Astell, 1985). The packaging and helper plasmids were propagated in the DH5α strain of E. coli.

AAV vector production and characterization

AAV6 vectors were generated by cotransfection of vector and helper plasmids into 293 cells seeded at 4 × 106 cells per 10-cm dish the prior day. Concentration and purification of AAV vectors were done as previously described (Halbert and Miller, 2004). The titer of vector stocks was determined by making 10-fold serial dilutions of vector and using HTX cells as targets for transduction (Halbert et al., 2001). Southern analysis was done to determine the number of vector genomes (vg) in the vector preparations, and was generally between 1011 and 1012 vg/ml. Procedures for Southern analysis have previously been described (Halbert et al., 1997). AAV6 vectors used in experiments had a vg:focus-forming unit (FFU) ratio in HTX target cells of 2–5 × 104 for the AP-expressing vectors, and 105 for the nβ-Gal-expressing vectors. To simplify nomenclature, the AP-expressing vectors are designated RSV-AP, CMV-AP, CAG-AP, or AGAP, with similar nomenclature for the nβ-Gal-expressing vectors.

AAV vector delivery to mouse airways

Animal studies were performed in accordance with guidelines set forth by the Institutional Review Office of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (Seattle, WA). Eight- to 10-week-old C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Taconic (Germantown, NY). Mice received vector by nasal aspiration as described (Halbert and Miller, 2004). Mice were given the AAV vector on day 1 and were killed 1 month later and their lungs were processed and stained for β-Gal or AP as previously described (Halbert et al., 1998). Processing and staining of the nasal cavity were done by first removing fur from the mouse head. The lower jaw was then removed and the nasal cavity was exposed by cutting the bone along the midline of the head, from the retro-orbital area to the nares. The head was fixed for 4 hr in 2% paraformaldehyde– phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then stained for marker gene expression as described for the lungs.

Quantitation of transduction efficiency in mouse lungs

AP-stained tissue slices from the entire lung were cut into 3-mm blocks and were paraffin embedded. Two sections were taken from each lung sample. One of these was counterstained with nuclear fast red and the second with hematoxylin and eosin. Quantitation of transduction efficiency was done by three methods. The first method used for AP-stained lungs relied on determining the percentage of apical surface that was positive for AP. AP protein in airway epithelial cells is apically expressed and therefore the transduction efficiency of the vectors encoding a CMV or an RSV promoter was scored by determining the percentage of apical surface that was AP positive for each airway. Quantitation of transduction in β-Gal-stained lungs was done by counting the number of cells having stained nuclei and dividing by the total number of nuclei in the airway epithelium. Results are expressed as histograms indicating the number of airways with various ranges of transduction rates. The third method relied on counting the number of AP+ or nβ-Gal+ cells per section on the slides stained with nuclear fast red. Positive alveolar cell counts were estimated from 10 random 1-mm2 areas for nβ-Gal and from 5 random 1-mm2 areas for AP. Positive counts were obtained by analysis of the entire tissue section for all other cell types. One 4-μm-thick section was scored per lung. The total area was quantitated by scanning stained slides (Adobe Photoshop; Adobe, San Jose, CA), and values were expressed as AP+ or βgal+ cells per cm2.

Assay for AP activity in cell lysates and mouse lung

HTX cells were plated at 105 cells per well in 6-well tissue culture dishes on day 1. On day 2, cells were exposed to 108 vg of AAV vector and were harvested on day 5. Mouse lungs were harvested 1 month after exposure to 2 × 1010 vg of AAV vector. Lungs were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until assayed. AP activity in cell and tissue lysates was determined by a spectrophotometric assay (Wolgamot and Miller, 1999). Controls included a blank with no cell lysate and cell lysate from uninfected cells or tissues. The protein content of each sample was determined by the method of Bradford, and product production was determined by using a 4-methylumbelliferone (MU) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) standard. AP activity was expressed as the amount of enzyme product (MU) produced per minute per μg of total protein.

RESULTS

Poor performance of AAV vectors containing the CMV promoter in mouse airway epithelium

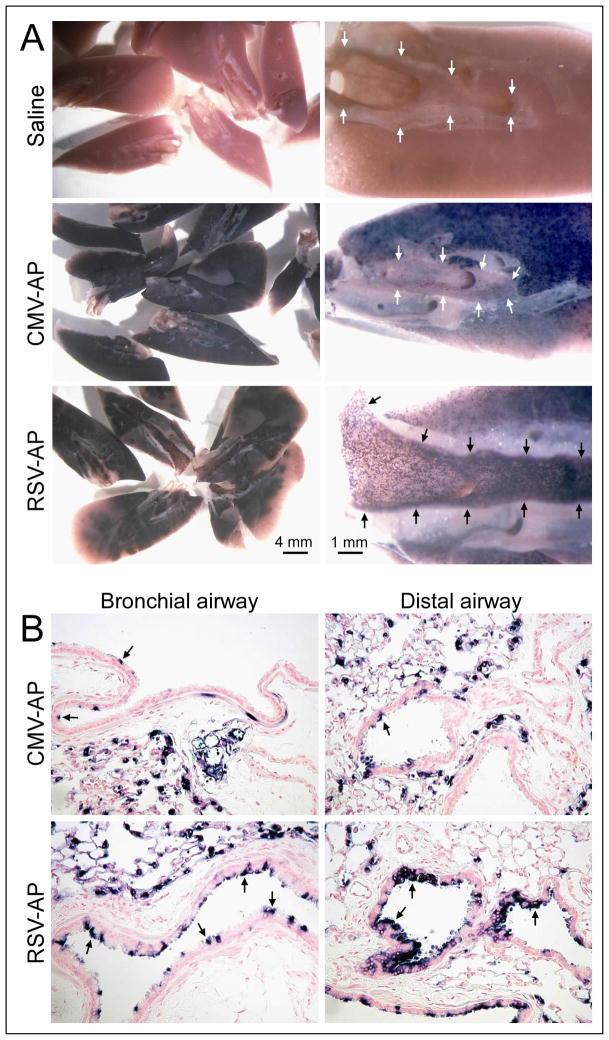

A comparison of the performance of AAV vectors containing the RSV or CMV promoter was done in mouse lung. Sedated mice spontaneously inhaled droplets containing 5 × 1010 vg of AP-encoding AAV vectors. One month later they were killed and their lungs were processed and stained for AP (Fig. 1A). The lung segments from mice given saline did not express AP (Fig. 1A, upper panels). Those given the AAV-AP vectors expressed AP as indicated by the dark staining in the lung parenchyma for both CMV-AP and RSV-AP (Fig. 1A, middle and lower panels, respectively). In contrast to the staining in the alveolar regions, the CMV vector gave minimal AP staining in the large airways (Fig. 1A, middle panels), whereas the RSV vector gave robust staining in these regions of the lung (Fig. 1A, lower panels). Histologic analysis showed that instillation of the RSV vector resulted in abundant staining in the airway epithelium of bronchial and distal airways (Fig. 1B, lower left and lower right panels), whereas the CMV vector exhibited more sporadic AP staining in bronchial and distal airways (Fig. 1B, upper left and upper right panels).

Fig. 1.

Expression of AP in mouse lung from vectors containing the CMV or RSV promoter/enhancers. Mice were given 5 × 1010 vg of the CMV-AP or RSV-AP vectors, or saline, and lungs were harvested one month later and stained for AP. (A) The left panels show representative segments from the lungs of one mouse each and the right panels show a higher magnification of lung segments cut parallel to the main bronchus (outlined by arrows). The AP stain is dark purple in color. (B) Mouse lungs were paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and counter-stained with nuclear fast red. Representative samples of AP staining found in bronchial and distal airways are shown. Arrows indicate examples of AP+ cells in the airway epithelium. Original magnification was 200×.

To confirm that the tissue expression phenotype was a general feature of the CMV and RSV promoters, we used another marker protein. AAV vectors containing the CMV and RSV sequences were linked to a cDNA that encodes a bacterial β-galactosidase protein with a nuclear localization signal (nβ-Gal). Mice were given 1011 genome-containing particles of the RSV- or CMV-nβ-Gal vector. One month after vector administration, lungs were histochemically stained for β-Gal expression. Cells expressing β-Gal in their nuclei were seen in the large airways of RSV-nβ-Gal-treated mice but rarely in CMV-nβ-Gal-treated mice (data not shown). Thus the lower efficiency of expression in the airway epithelium from the CMV promoter occurred with both AP and nβ-Gal sequences.

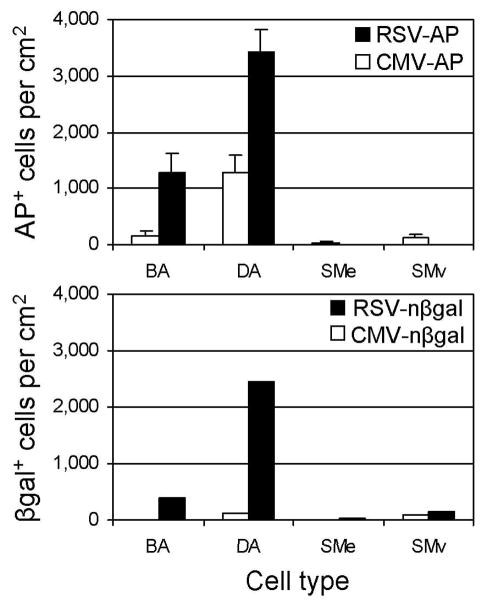

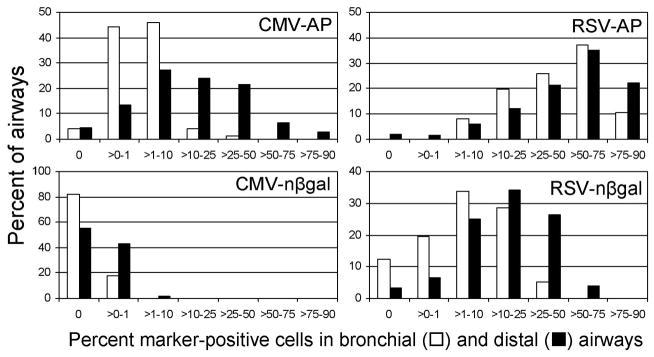

Quantitation of AP and nβ-Gal expression in airways is shown in Fig. 2. The RSV-AP vector transduced greater than 50% of the airway epithelium in 58% of the distal airways and in 47% of bronchial airways. In contrast, the CMV-AP vector ACAP transduced 25% or less of the airway epithelium in 90% of bronchial airways and in 70% of distal airways. Similarly, the RSV-nβ-Gal vector transduced greater than 10% percent of the airway epithelium in 34% of bronchial airways and 60% of distal airways analyzed. The CMV-nβ-Gal vector transduced bronchial airways at an average rate of ≤1%, and only 14 distal airways of 717 (2%) showed between 1 and 10% transduction; the rest were ≤1% positive. These results clearly show that the CMV promoter performs poorly in the airway epithelium compared to the RSV promoter. We also note that transduction by the nβ-Gal vectors was in general lower than that of the AP vectors. This could be due to the more robust staining obtained with AP in comparison to nβ-Gal, allowing us to detect cells expressing even low levels of AP, or perhaps the bacterial nβ-Gal nucleic acid sequences negatively affect transcription or translation in eukaryotic cells, in comparison to the AP sequences, which are of human origin.

Fig. 2.

Percentages of AP+ and nβgal+ cells in airways of mouse lungs exposed to vectors containing the RSV or CMV promoter/enhancers. Morphometric analysis was done on sections of mouse lungs stained for AP to determine the percent positive cells in airways. Results are expressed as a histogram showing the percentage of airways with the indicated range of positive cells. The AAV vector used is indicated in each histogram. Data are from three mice per group for the AP vectors and from four mice per group for the nβ-Gal vectors. The number of airways scored for the AP vectors was approximately 60 bronchial and 400 distal airways, and for the nβ-Gal vectors, 70 bronchial and 600 distal airways.

Alveolar cells represent the most abundant population of cells in the lung as well as the largest number of cells positive for marker protein expression. Approximately 25% of alveolar cells were marker protein positive and the efficiency of transduction of alveolar cells between the CMV- and RSV-containing vectors was not significantly different at the dose tested. Smooth muscle cells underlying the airway epithelium and in the vasculature were also positive for transduction by the AAV vectors. Morphometric analysis was done to determine the absolute number of positive cells in these regions and in the airways (Fig. 3). Transduction of smooth muscle cells by AAV vectors was significantly lower than that of epithelial cells and the quantitation did not show any clear differences in smooth muscle cell transduction by the vectors.

Fig. 3.

Quantitation of AP+ and nβgal+ cells in various cell types in mouse lung after exposure to vectors containing the CMV or RSV promoter/enhancers. Morphometric analysis was done on sections of mouse lungs stained for AP or β-Gal to determine the number of cells and cell types expressing AP or nβ-Gal. The cell types are as designated: BA, bronchial airway; DA, distal airway; SMe, smooth muscle underlying airway epithelium; SMv, smooth muscle in vasculature.

Efficient transduction of mouse lungs by AAV vectors containing hybrid promoters

The CMV immediate-early enhancer/promoter is variably active in different tissues of transgenic mice (Furth et al., 1991). In particular, expression in lung and skin seemed to be especially low. In contrast, a hybrid promoter/enhancer containing CMV sequences was strongly active in epithelial cells of mouse skin (Sawicki et al., 1998). We tested this hybrid regulatory sequence (designated CAG) that contained the CMV-IE1 enhancer, a chicken β-actin promoter, and an intron. We wanted to determine whether the hybrid promoter/enhancer would perform well in airway epithelial cells even though it contained CMV regulatory sequences. Two AAV vectors were made, one having the CAG sequences in place of the RSV promoter/enhancer (CAG-AP) and another with the CMV enhancer deleted from CAG, leaving the β-actin promoter and the intron (AGAP).

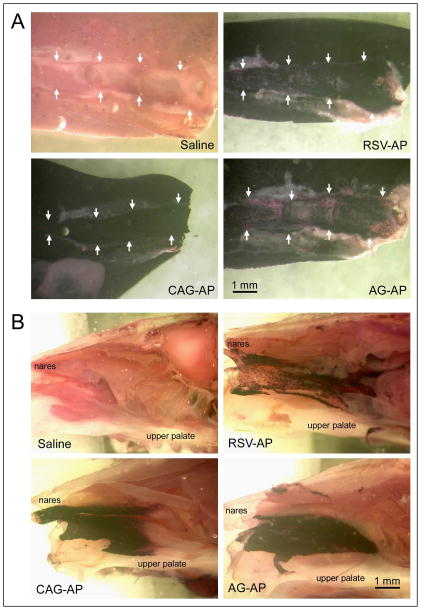

Mice were exposed to these vectors and their lungs were harvested as in the experiments described above. Figure 4A shows typical AP staining of lungs from mice given each of the vectors. Overall, all three vectors transduced the lung parenchyma and the large airways efficiently, resulting in robust AP expression. Surprisingly, the CMV enhancer in the context of the CAG sequences gave the highest level of staining in the large airway, where there was practically no unstained area (Fig. 4A, lower left panel).

Fig. 4.

Expression of AP in mouse lung and nasal epithelium from vectors containing the RSV, CAG, or AG hybrid promoter/enhancers. Mice were given 2 × 1010 vg of the AAV vectors or saline and were analyzed one month later. (A) Lungs were stained for AP. The main bronchial airway is outlined by arrows and a 1 mm scale bar is shown. (B) The heads from the mice were fixed and stained for AP. Then the head was cut along the midline extending from the top of cranium to the nares to expose the nasal cavity. One half of the opened nasal cavity is shown. The locations of the upper palate and the nares are indicated and a 1 mm scale bar is shown.

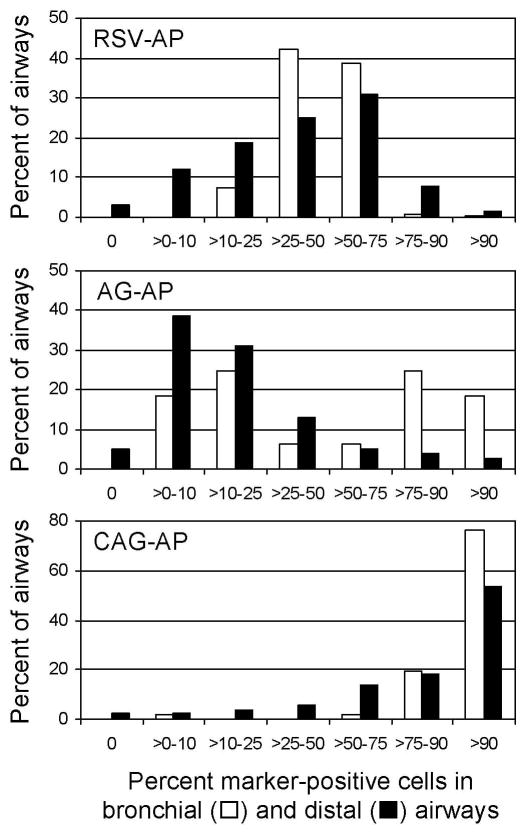

Quantitation of transduction efficiency was done by determining the percent positive cells in bronchial and distal airways (Fig. 5). Administration of the CAG-AP vector resulted in greater than 90% AP-positive epithelial cells in 50% or more of bronchial and distal airways. Removal of the CMV enhancer resulted in 12% of distal airways having greater than 50% positive cells. The RSV vector gave intermediate values of 40% of airways having greater than 50% positive cells.

Fig. 5.

Quantitation of AP transduction in mouse lung from vectors containing the RSV, CAG, or AG hybrid promoter/enhancers. Morphometric analysis was done on sections of mouse lungs stained for AP to determine the percent positive cells in airways. Results are expressed as a histogram for each vector. Data are from three mice per vector. The number of airways scored per vector was approximately 60 bronchial and 400 distal airways.

Robust transduction from nasal epithelium to distal alveoli by AA6 vectors

Models of AAV transduction of the upper airway are important for diseases such as cystic fibrosis because a measure of nasal potential difference (NPD) can be used to determine the potential of a gene transfer system for correcting the CFTR defect. This has been shown to be feasible in a CF knockout mouse after adenoviral vector delivery of the wild-type CFTR cDNA (Grubb et al., 1994). We examined transduction in the upper airways. AP staining of mouse nasal cavity showed that transduction of the nasal epithelium (both olfactory and nonolfactory) occurred with all three vectors (Fig. 4B). Both the CAG-AP and AG-AP vectors performed better than the RSV-AP vector and gave robust staining of the murine nasal epithelium.

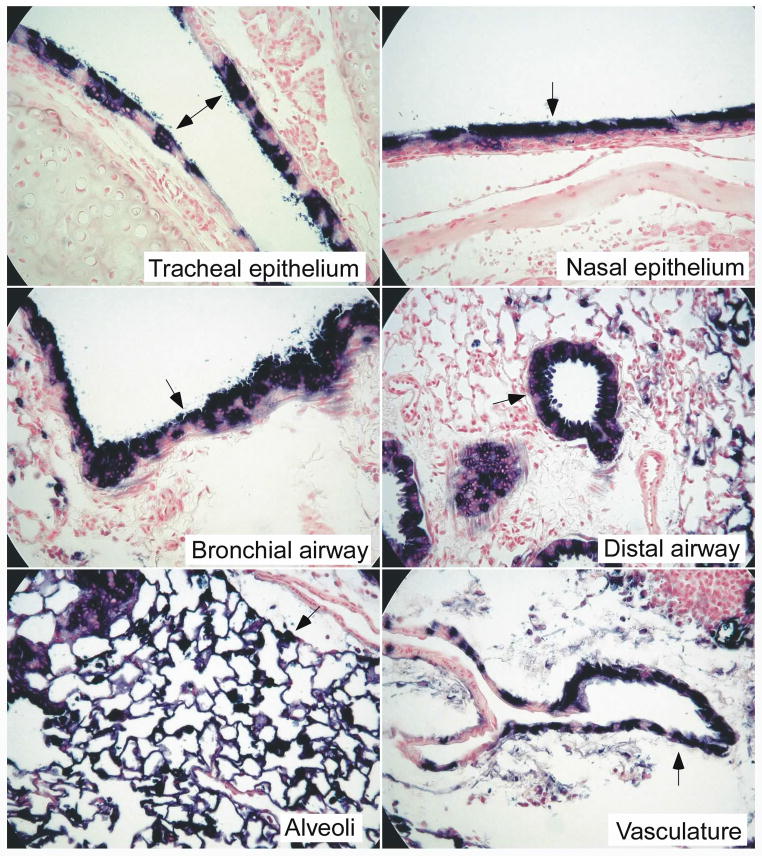

Interestingly, AAV6 vector transduction seemed to occur even with limited tissue exposure to the vector. Passage of spontaneously inhaled droplets of vector through the nasal cavity and the trachea is presumably brief, yet intense AP staining is seen in the nasal as well as in the tracheal epithelium of mice given CAG-AP (Fig. 6, top panels). Histologic analyses showed robust AP staining in the bronchial and distal airways (Fig. 6, middle panels). Note that the AP staining penetrates deeper into the epithelium compared to that of the RSV vector (Fig. 1B). Almost all alveolar cells were stained in most regions of the lung (Fig. 6, left bottom panel), and many of the blood vessel walls (smooth muscle cells) were also transduced (Fig. 6, right bottom panel). Widespread but less intense staining of the nasal epithelium and trachea were seen with the RSV-AP and AGAP vectors (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Histologic analysis of mouse lungs expressing AP from the CAG hybrid promoter/enhancer. Mouse lungs, trachea, and heads were paraffin embedded and sections were stained with nuclear fast red. Arrows indicate bronchial and distal airways, alveoli, vasculature, and tracheal and nasal epithelium. Original magnification: 400× for bronchial airways, alveoli, and tracheal and nasal epithelium; 200× for distal airways; 100× for vasculature.

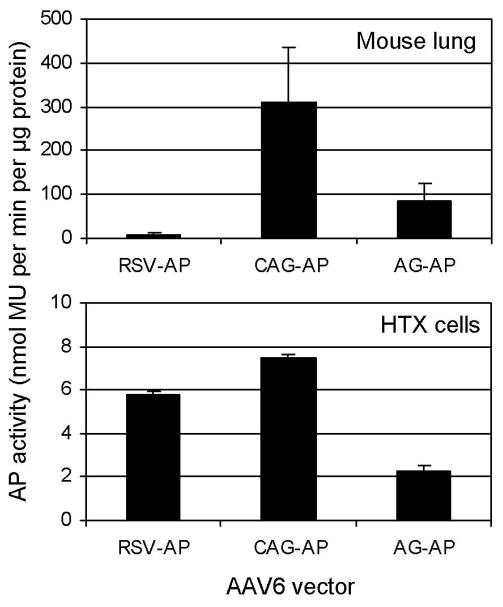

Comparison of in vivo versus in vitro transduction, and use of histochemical staining or enzyme activity assays for evaluating transduction

Histochemical staining for AP is based on the enzymatic activity of a highly active AP enzyme and is thus a sensitive detection technique. However, AP staining also appears to saturate at low levels of protein expression, making it difficult to detect differences in AP protein at high levels of expression. Therefore we used a spectrophotometric assay to directly measure AP enzyme activity in lung to compare the promoter/enhancer activity of the RSV-AP, CAG-AP, and AG-AP vectors (Fig. 7). Note that alveolar cells are the most abundant cells in the lung and the predominant cell type positive for marker gene expression; therefore, AP activity in total lung reflects primarily the level of AP protein in alveolar cells. The results show that there was a much greater difference in AP activity between the three promoter/enhancer sequences than was apparent by morphometric analysis. The CAG promoter was 38-fold more active than the RSV promoter, whereas the AG promoter was only 10-fold more active than the RSV promoter. Analysis of these vectors in the HTX cell line revealed that the differences in AP activities were not as dramatic and, regarding the RSV and CAG sequences, not predictive of in vivo activity (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

AP enzyme activity in mouse lungs and HTX cells exposed to AAV vectors containing the RSV, CAG, and AG promoter/enhancers. Extracts from mouse lungs and HTX cells were assayed for AP activity and results are expressed as the amount of enzyme product (MU) per minute per μg of total protein. Means ± SD are shown for three mice per group and for triplicate cultures of HTX cells.

DISCUSSION

In an effort to augment transduction by AAV6 vectors in the airway, we replaced the RSV promoter in our standard vectors with the CMV promoter, because the CMV promoter has been shown to be considerably stronger in cell lines from various tissues and species (Foecking and Hofstetter, 1986). This change actually lowered transduction rates in the airway epithelium. Key features of the life cycle of CMV may help explain this phenomenon. Infection by CMV occurs in most humans but is asymptomatic because of the latent status of the virus in most healthy individuals. The mechanism underlying maintenance of the latent phase and the switch to lytic and productive phase remains unclear. However, the immediate-early promoter/enhancer region regulates the level of immediate-early gene products necessary for productive infection, and contains binding sites for both viral and cellular proteins that can be involved in these processes (Lundquist et al., 1999; Isomura et al., 2004; Lashmit et al., 2004). It is likely that different tissues and the state of differentiation of cells within these tissues result in a varied repertoire and levels of these cellular proteins. Thus, it is not surprising that the human CMV enhancer/promoter has previously been shown to drive high transcriptional activity in transfected cultured cells (Foecking and Hofstetter, 1986) and in multiple tissues in transgenic mice (Schmidt et al., 1990) and yet has also been reported to be quite variable between different tissues in strains of transgenic mice where the overall expression of CMV-driven transgene is high (Furth et al., 1991). Our results indicating low activity in mouse airway epithelium and high levels in alveolar cells are consistent with these previous observations of variable CMV-driven gene expression.

The CAG hybrid promoter does not exhibit repression in airway epithelial cells even though it contains sequences from the CMV enhancer. This may be due to a requirement for multiple elements in both the enhancer and promoter regions to act in concert for repression, or simply that the presence of cis-acting sequences within the constitutively active actin promoter and the intron can overcome the negative regulatory elements. Previous studies have demonstrated that the CAG promoter/enhancer is active not only in cultured cells (Niwa et al., 1991) but also in the suprabasal and basal cells of the murine epidermis, whereas the CMV promoter/enhancer is not active in most cell types of the epidermis (Sawicki et al., 1998). Here we have tested CAG in mouse lung and found it to have high levels of activity in all cell layers of the pseudo-stratified airway epithelium as well as in other cell types of the lung including the alveolar cells. It was superior to the RSV promoter and to the AG promoter, which lacked a CMV enhancer region. It remains to be seen whether these results in mouse lung translate to the human airway.

The identification and characterization of novel adeno-associated virus isolates from both human and nonhuman primates have yielded AAV types with different tropism that can be used to treat diseases affecting different tissues. Of these, AAV1 has been shown to be efficient in muscle (Xiao et al., 1999) and AAV8 in liver (Gao et al., 2002). AAV6 is a strong candidate for endothelial cells (Kawamoto et al., 2005), muscle (Blankinship et al., 2004), and lung (Halbert et al., 2001). It has been shown that unlike AAV2, AAV6 and AAV8 exhibit rapid uncoating of vector genomes, which is crucial for efficient liver delivery. This feature may also contribute to the safety of the vector relative to the host immune response. In fact, AAV6 vectors do not generate a strong immune response in animal models of vector delivery as compared to AAV2 vectors (Halbert et al., 2000). In addition, the prevalence and strength of humoral immunity in the human population (Halbert et al., 2006) indicate that vectors made with AAV6 capsids may have an advantage over AAV2 in avoiding preexisting immunity, particularly for lung gene therapy.

Here, we have taken vector development a step further by showing that with the highly active CAG promoter, we can enhance the expression of the epithelial cell-tropic AAV6 vector. We have been able to achieve >90% transduction in the majority of large and small airways. Likewise, almost every cell in the alveoli was positive for marker gene expression. These results extended to the cells of the upper airway epithelium of the trachea and the nasal cavity. The efficient transduction of the upper airways indicates avid, high-affinity binding after spontaneous inhalation of vectors given in droplets. While this study was in progress, a comparative study of a CMV promoter and a CMV β-actin hybrid promoter was published, showing more efficient transduction by the latter in alveolar cells when using AAV5 or AAV1 vectors (Virella-Lowell et al., 2005). However, no transduction was detected in bronchial epithelial cells, a primary target for CF gene therapy. In contrast, our results show high transduction rates in the airway epithelium. It is not clear whether this difference is due to the AAV capsid types used or to differences in nucleotide sequences included in the hybrid promoters used (the nucleotide sequences were not specified in the paper by Virella-Lowell et al. [2005]).

A major hurdle for CF gene therapy using AAV vectors is that the size of the CFTR cDNA is close to the packaging limit of AAV. Certainly the CAG promoter would be too large to package with the CFTR cDNA. However, strategies using trans-splicing AAV vectors (Duan et al., 2001) and paired AAV vectors that recombine in target cells (Halbert et al., 2002) could be developed to achieve expression of the complete CFTR. In parallel with the development of AAV-CFTR vectors, other lung diseases such as α1-antitrypsin can be a therapeutic goal for AAV6 gene therapy. The robust transduction of alveolar cells suggests that local correction of the protease deficiency is possible, and noninvasive gene transfer to the lung can be used for systemic delivery of therapeutic proteins.

OVERVIEW SUMMARY.

We have previously shown that AAV6 vectors promote relatively high rates of transduction in the airway epithelium of animals. Here we have examined transduction by AAV6 vectors containing various transcriptional elements in an effort to further increase expression in the airway epithelium. By using a highly active hybrid promoter, we could transduce ~90% of the cells in the majority of large and small airways, the trachea, and the nasal cavity. Likewise, almost all alveolar cells were positive for marker gene expression. These results support the application of AAV6 vectors containing highly active promoters for the treatment of common genetic diseases that affect the lung, such as cystic fibrosis and α1-antitrypsin deficiency.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Alfano for dedicated technical assistance, Dr. Charles Alpers (University of Washington, Seattle, WA) and the Pathology Core of the Molecular Therapy Core Center for immunohistochemistry services, and Dr. J. Miyasaki (Osaka University, Suita, Japan) for providing the CAG hybrid promoter. This work was supported by grants DK47754 and HL66947 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- ALLEN JM, HALBERT CL, MILLER AD. Improved adeno-associated virus vector production with transfection of a single helper adenovirus gene, E4orf6. Mol Ther. 2000;1:88–95. doi: 10.1006/mthe.1999.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLANKINSHIP MJ, GREGOREVIC P, ALLEN JM, HARPER SQ, HARPER H, HALBERT CL, MILLER AD, CHAMBERLAIN JS. Efficient transduction of skeletal muscle using vectors based on adeno-associated virus serotype 6. Mol Ther. 2004;10:671–678. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOISSY R, ASTELL CR. An Escherichia coli recBCsbcBrecF host permits the deletion-resistant propagation of plasmid clones containing the 5’-terminal palindrome of minute virus of mice. Gene. 1985;35:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOSHART M, WEBER F, JAHN G, DORSCH-HASLER K, FLECKENSTEIN B, SCHAFFNER W. A very strong enhancer is located upstream of an immediate early gene of human cytomegalovirus. Cell. 1985;41:521–530. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUAN D, YUE Y, ENGELHARDT JF. Expanding AAV packaging capacity with trans-splicing or overlapping vectors: A quantitative comparison. Mol Ther. 2001;4:383–391. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENGELHARDT JF, YANKASKAS JR, ERNST SA, YANG Y, MARINO CR, BOUCHER RC, COHN JA, WILSON JM. Submucosal glands are the predominant site of CFTR expression in the human bronchus. Nat Genet. 1992;2:240–248. doi: 10.1038/ng1192-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISHER KJ, JOOSS K, ALSTON J, YANG Y, HAECKER SE, HIGH K, PATHAK R, RAPER SE, WILSON JM. Recombinant adeno-associated virus for muscle directed gene therapy. Nat Med. 1997;3:306–312. doi: 10.1038/nm0397-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOECKING MK, HOFSTETTER H. Powerful and versatile enhancer-promoter unit for mammalian expression vectors. Gene. 1986;45:101–105. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FURTH PA, HENNIGHAUSEN L, BAKER C, BEATTY B, WOYCHICK R. The variability in activity of the universally expressed human cytomegalovirus immediate early gene 1 enhancer/promoter in transgenic mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6205–6208. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.22.6205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAO GP, ALVIRA MR, WANG L, CALCEDO R, JOHNSTON J, WILSON JM. Novel adeno-associated viruses from rhesus monkeys as vectors for human gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11854–11859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182412299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREGOREVIC P, BLANKINSHIP MJ, ALLEN JM, CRAWFORD RW, MEUSE L, MILLER DG, RUSSELL DW, CHAMBERLAIN JS. Systemic delivery of genes to striated muscles using adeno-associated viral vectors. Nat Med. 2004;10:828–834. doi: 10.1038/nm1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRUBB BR, PICKLES RJ, YE H, YANKASKAS JR, VICK RN, ENGELHARDT JF, WILSON JM, JOHNSON LG, BOUCHER RC. Inefficient gene transfer by adenovirus vector to cystic fibrosis airway epithelia of mice and humans. Nature. 1994;371:802–806. doi: 10.1038/371802a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALBERT CL, MILLER AD. AAV-mediated gene transfer to mouse lungs. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;246:201–212. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-650-9:201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALBERT CL, STANDAERT TA, AITKEN ML, ALEXANDER IE, RUSSELL DW, MILLER AD. Transduction by adeno-associated virus vectors in the rabbit airway: Efficiency, persistence, and readministration. J Virol. 1997;71:5932–5941. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5932-5941.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALBERT CL, STANDAERT TA, WILSON CB, MILLER AD. Successful readministration of adeno-associated virus vectors to the mouse lung requires transient immunosuppression during the initial exposure. J Virol. 1998;72:9795–9805. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9795-9805.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALBERT CL, RUTLEDGE EA, ALLEN JM, RUSSELL DW, MILLER AD. Repeat transduction in the mouse lung by using adeno-associated virus vectors with different serotypes. J Virol. 2000;74:1524–1532. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.3.1524-1532.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALBERT CL, ALLEN JM, MILLER AD. Adeno-associated virus type 6 (AAV6) vectors mediate efficient transduction of airway epithelial cells in mouse lungs compared to that of AAV2 vectors. J Virol. 2001;75:6615–6624. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6615-6624.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALBERT CL, ALLEN JM, MILLER AD. Efficient mouse airway transduction following recombination between AAV vectors carrying parts of a larger gene. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:697–701. doi: 10.1038/nbt0702-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALBERT CL, MILLER AD, MCNAMARA S, EMERSON J, GIBSON RL, RAMSEY B, AITKEN ML. Prevalence of neutralizing antibodies against adeno-associated virus (AAV) types 2, 5, and 6 in cystic fibrosis and normal populations: Implications for gene therapy using AAV vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:440–447. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERZOG RW, HAGSTROM JN, KUNG SH, TAI SJ, WILSON JM, FISHER KJ, HIGH KA. Stable gene transfer and expression of human blood coagulation factor IX after intramuscular injection of recombinant adeno-associated virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5804–5809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERZOG RW, YANG EY, COUTO LB, HAGSTROM JN, ELWELL D, FIELDS PA, BURTON M, BELLINGER DA, READ MS, BRINKHOUS KM, PODSAKOFF GM, NICHOLS TC, KURTZMAN GJ, HIGH KA. Long-term correction of canine hemophilia B by gene transfer of blood coagulation factor IX mediated by adeno-associated viral vector. Nat Med. 1999;5:56–63. doi: 10.1038/4743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISOMURA H, TSURUMI T, STINSKI MF. Role of the proximal enhancer of the major immediate-early promoter in human cytomegalovirus replication. J Virol. 2004;78:12788–12799. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12788-12799.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAUFFMAN SL. Cell proliferation in the mammalian lung. Int Rev Exp Pathol. 1980;22:131–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWAMOTO S, SHI Q, NITTA Y, MIYAZAKI J, ALLEN MD. Widespread and early myocardial gene expression by adeno-associated virus vector type 6 with a β-actin hybrid promoter. Mol Ther. 2005;11:980–985. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KESSLER PD, PODSAKOFF GM, CHEN X, MCQUISTON SA, COLOSI PC, MATELIS LA, KURTZMAN GJ, BYRNE BJ. Gene delivery to skeletal muscle results in sustained expression and systemic delivery of a therapeutic protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14082–14087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LASHMIT PE, LUNDQUIST CA, MEIER JL, STINSKI MF. Cellular repressor inhibits human cytomegalovirus transcription from the UL127 promoter. J Virol. 2004;78:5113–5123. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5113-5123.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUNDQUIST CA, MEIER JL, STINSKI MF. A strong negative transcriptional regulatory region between the human cytomegalovirus UL127 gene and the major immediate-early enhancer. J Virol. 1999;73:9039–9052. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9039-9052.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIWA H, YAMAMURA K, MIYAZAKI J. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene. 1991;108:193–199. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90434-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAWICKI JA, MORRIS RJ, MONKS B, SAKAI K, MIYAZAKI J. A composite CMV-IE enhancer/β-actin promoter is ubiquitously expressed in mouse cutaneous epithelium. Exp Cell Res. 1998;244:367–369. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHMIDT EV, CHRISTOPH G, ZELLER R, LEDER P. The cytomegalovirus enhancer: A pan-active control element in transgenic mice. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:4406–4411. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.8.4406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEILER MP, MILLER AD, ZABNER J, HALBERT CL. Adeno-associated virus types 5 and 6 use distinct receptors for cell entry. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:10–19. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMAS CE, STORM TA, HUANG Z, KAY MA. Rapid uncoating of vector genomes is the key to efficient liver transduction with pseudotyped adeno-associated virus vectors. J Virol. 2004;78:3110–3122. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.6.3110-3122.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VIRELLA-LOWELL I, ZUSMAN B, FOUST K, LOILER S, CONLON T, SONG S, CHESNUT KA, FERKOL T, FLOTTE TR. Enhancing rAAV vector expression in the lung. J Gene Med. 2005;7:842–850. doi: 10.1002/jgm.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALTERS RW, YI SM, KESHAVJEE S, BROWN KE, WELSH MJ, CHIORINI JA, ZABNER J. Binding of adeno-associated virus type 5 to 2,3-linked sialic acid is required for gene transfer. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20610–20616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOLGAMOT G, MILLER AD. Replication of Mus dunni endogenous retrovirus depends on promoter activation followed by enhancer multimerization. J Virol. 1999;73:9803–9809. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.9803-9809.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU Z, MILLER E, AGBANDJE-MCKENNA M, SAMULSKI RJ. α2,3 and α2,6 N-linked sialic acids facilitate efficient binding and transduction by adeno-associated virus types 1 and 6. J Virol. 2006;80:9093–9103. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00895-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XIAO W, CHIRMULE N, BERTA SC, MCCULLOUGH B, GAO G, WILSON JM. Gene therapy vectors based on adeno-associated virus type 1. J Virol. 1999;73:3994–4003. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3994-4003.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XIAO X, LI J, SAMULSKI RJ. Efficient long-term gene transfer into muscle tissue of immunocompetent mice by adeno-associated virus vector. J Virol. 1996;70:8098–8108. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8098-8108.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANKASKAS RJ, SUCHINDRAN H, SARKODI B, NETTESHEIM P, RANDELL S. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein is selectively expressed in ciliated airway epithelial cells [abstract] Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:A26. [Google Scholar]