Abstract

The precise mechanisms of kidney stone formation and growth are not completely known, even though human stone disease appears to be one of the oldest diseases known to medicine. With the advent of the new digital endoscope and detailed renal physiological studies performed on well phenotyped stone formers, substantial advances have been made in our knowledge of the pathogenesis of the most common type of stone former, the idiopathic calcium oxalate stone former (ICSF) as well as nine other stone forming groups. The observations from our group on human stone formers and those of others on model systems have suggested four entirely different pathways for kidney stone formation. Calcium oxalate stone growth over sites of Randall’s plaque appear to be the primary mode of stone formation for those patients with hypercalciuria. Overgrowths off the ends of Bellini duct plugs have been noted in most stone phenotypes, do they result in a clinical stone? Micro-lith formation does occur within the lumens of dilated inner medullary collecting ducts of cystinuric stone formers and appear to be confined to this space. Lastly, cystinuric stone formers also have numerous small, oval, smooth yellow appearing calyceal stones suggestive of formation in free solution. The scientific basis for each of these four modes of stone formation are reviewed and used to explore novel research opportunities.

Introduction

As the details of human stone formation have accumulated, new opportunities are arising for laboratory and clinical experiments, and our purpose here is to offer a review of details that appear crucial to human stone formation and also amenable to modern research techniques. Thus far we and others (1–22) have identified 4 different possible modes of stone formation: growth over white (Randall’s) interstitial hydroxyapatite (HA) plaque (1,2,4,6–9,12–15,17,22); growth over Bellini duct (BD) plugs (3,5–11,13–16,18–22); formation of micro-liths within inner medullary collecting ducts (IMCD) (3); and formation in free solution within the calyces or renal collecting system (3,18–21). Model systems, the usual conveyance from the clinic to the bench, have more or less benefitted nephrolithiasis research, from animal models to in vitro studies of crystallization kinetics and inhibitors. Now that the details of human stone formation are becoming clear such models can be made to more closely resemble clinical reality.

Growth on plaque

Simple observation during the course of surgery for stone removal shows that stones can grow attached to plaque (Figure 1, panel a). Randall (22) in 1937 showed in cadavers more or less what modern surgeons easily visualize with digital optic scopes. When the stone is removed (Figure 1 panel b) the attachment site is often visible, as here, and is composed of HA. With effort one can reconstruct from intra-operative images (12) the exact location on plaque from which stones have been removed, and also prove that a majority of stones within a particular patient do indeed grow attached to papillae and specifically to the plaque regions of the papillae (12). In a similar vein, unattached stones can be recognized as having a plaque origin from their telltale HA attachment site residues (23).

Figure 1. Attached stone to site of Randall’s plaque in ICSF patient.

Panel a shows an endoscopic view of a calcium oxalate stone (arrow) attached to the tip of a papilla. Several sites of interstitial (Randall’s) plaque (arrowheads) are seen around the attached stone. Note the normal appearance of the papilla. Panel b shows the same papilla after the stone was removed. The papillary surface of that same stone is seen by light microscopy as an inset at the bottom left of this panel. A small site of whitish mineral (marked by asterisk) is clearly visible and was identified as hydroxyapatite while the rest of the stone is calcium oxalate. After performing micro-CT imaging of this stone, these images were aligned and superimposed onto the papilla in order to determine if the small site of hydroxyapatite aligned with a region of Randall’s plaque on the papilla. Indeed, the small apatite region on the stone aligned with a small bleed (see circled area) on a site of interstitial plaque, presumably the site where the stone was attached to the papillum.

With care, from the mass of stone formers, one can define what appears to be a reasonably pure phenotype: patients who form calcium oxalate (CaOx) stones and have no systemic disease as a cause of stones, who are named through long custom (24) ‘idiopathic’ CaOx stone formers (ICSF) (25). Many but not all of these ICSF have idiopathic hypercalciuria (IH) a familial and presumably genetic trait. ICSF form most of their CaOx stones on plaque as we have illustrated in Figure 1.

The earliest formation of RP appears to be in the basement membranes of the thin loops of Henle (Figure 2 panel a) as micro-spherulites made of alternating lamina of matrix with and without HA crystals (Figure 2 panels b–e) (1). As well, plaque particles nucleate in the interstitium, where instead of remaining separate as in the basement membranes they fuse to form a continuous pool of matrix in which HA crystals reside in isolated clumps (Figure 2 panel f). It is the second form of plaque that extends between the tubules and vessels until it abuts against the limiting papillary epithelium (Figure 2 panel g). It is this plaque surgeons see as ‘white plaque’.

Figure 2. Histologic images showing initial sites of Randall’s plaque and its progression.

Light microscopy reveals the initial sites of interstitial deposits (panel a, arrows) to be in the basement membranes of the thin loops of Henle at the papilla tip. By transmission electron microscopy, these sites of interstitial deposits are made up of numerous micro-spherulites of alternating lamina of matrix with and without crystals (panels b–e). The individual deposits are as small as 50 nm and grow into multi-layered spheres of alternating light and electron dense rings with the light regions representing crystals and the electron dense sites matrix material. Extensive accumulation of crystalline deposits occur around the loops of Henle (panel f, double arrows) spread into the nearby interstitial space extending to the urothelial lining (panel g) of the urinary space. Disruption of the urothelial layer exposes the site of interstitial deposits to the urine which can trigger overgrowth of mineral and thus stone formation.

Given some breach of urothelial integrity, this plaque becomes exposed to urine (26). What is exposed is not HA crystals but the matrix in which they reside. The details of overgrowth can be visualized in small stones harvested with their tissue base (Figure 3, panels a and b) (27). The plaque area of overgrowth and the stone itself when restored to their original orientation with respect to one another (Figure 3 panel c) demonstrate epithelial disruption and separation of some plaque from tissue which is adherent to the base of the stone. Visualized by TEM (Figure 3 panel d) the plaque at the lower right of the panel shows white islands of HA within plaque matrix. The exposed plaque is covered by a ribbon of alternating matrix and HA crystals. The innermost layer of matrix (inset at upper right of panel) contains THP meaning that the matrix of exposed plaque is initially covered by an organic matrix of urine origin (27) as the interstitial matrix cannot normally have access to THP (28). As if to recapitulate the plaque particles, the HA crystals nucleate in alternating matrix layers, some layers free of crystals, some with crystals. At the terminal urinary border, crystals sweep into what was once the urinary space to form the base of the stone.

Figure 3. Ultrastructural features of attachment site of kidney stone from idiopathic calcium oxalate stone former.

Panel a is an endoscopic view of a half millimeter stone seen attached to papilla tip at a site of Randall’s plaque (arrow) while panel b shows the same stone by light microscopy with underlying tissue (arrow) after biopsy. Panel c shows the same stone-tissue complex seen in panel b but after demineralization. Note that the stone separated from the underlying tissue (rectangular box). Some tissue is still stuck to stone (asterisk) while the double arrowheads show a region of cellular debris. The single arrows point to areas on the papilla that still have a urothelial covering, these cells are lost at the stone-tissue junction. Panel d is a high magnification transmission electron micrograph of the tissue attachment site. The region of Randall’s plaque (lower right) is seen covered by a multi-layer, ribbon-like structure, have crystalline and matrix material, which are highlighted in the insert (upper right). A region marked “A” shows small (asterisk) and large crystals (single arrows) embedded in the outer (urine) side of the ribbon.

The range of novel research opportunities offered by growth on plaque mirror our ignorance of the process. The earliest nuclei of plaque appear in the type 3 collagen of the thin limb basement membrane (Figure 4, left most cartoon). Why there? The driving forces can arise from the lumen or interstitial fluid. We (29) have gathered evidence that in animals thin limb fluid is supersaturated with respect to calcium phosphate (CaP) as brushite (BR). The ionic composition of the human interstitium is unknown. The epithelium of the thin limbs is very impermeable to calcium (30) but high fluid CaP SS may be present much of the day because IH, which involves increased calcium delivery out of the proximal tubule (31,32), manifests especially with meals (31–35).

Figure 4. Calcium oxalate stones grows on sites of interstitial (Randall’s) plaque.

The earliest nuclei of plaque appear in the basement membrane of the thin loops of Henle (left most cartoon) as multi-layered spherulites of crystals and matrix material. Subsequently, interstitial plaque genesis (second cartoon, upper row) seems to occur on type 1 collagen in the interstitial space where individual spherulites appear to fuse. With time, islands of matrix and spherulites spread to the basal side of the urothelium and the plaque remains protected from the urine until the urothelium is breached (cartoon 3, upper row). At this point the urine appears to create nucleations that form the base of an overgrowth (cartoons 4 to 8). The urine proteins that form the immediate overlay include Tamm Horsfall protein (THP) and osteopontin (OP) followed by amorphous hydroxyapatite. As the overgrowth region expands there is a conversion of hydroxyapaittie to calcium oxalate (CaOx), the primary mineral of the stone of a ICSF stone patient.

Biophysical modelling using known permeabilities and ranges of reasonable interstitial molarities could perhaps help establish a range of SS for basement membrane. Likewise the composition of the membranes may be important. Why do the particles remain separate in the membrane? Why are they laminated? The nature of the particle matrix is not known except for osteopontin and the third heavy chain of the inter alpha trypsin inhibitor (36,37), nor why particles do not grow past a general size of 10 microns. Whether particles form directly on the basement membrane type 3 collagen, and if so where on the molecule, is also an open question. Do thin limb cells respond to the presence of the particles in the basement membrane via expression of novel proteins? Given proper techniques small samples from early plaque could help resolve these questions and open up the problem of membrane plaque genesis.

Interstitial plaque genesis (Figure 4, second cartoon, upper row) seems to be on type 1 collagen (1,38), but the exact region of the collagen remains to be shown (1,38). The driving forces for crystallization are entirely interstitial and unknown in quantity. As for all plaque particles, radial layering remains a puzzle. Unlike in membranes, particles fuse; why this happens is unknown.

Nucleation of HA on types 1 and 3 collagen, if thoughtfully performed, might clarify what happens in human kidneys. More directly, samples from kidneys could be studied in terms of nucleation sites and mechanisms of fusion. As in the membrane the matrix molecules are poorly described. We have described only osteopontin and the third heavy chain of the inter-alpha trypsin inhibitor (36,37). This latter is known to stabilize collagen structures after injury (39); is its presence evidence of injury from plaque that we cannot recognize, or is it remodeling?

What controls interstitial calcium concentration is unknown for papillum. We (13) have proposed vas washdown, the down transport in vasa recta of calcium reabsorbed in outer medullary thick ascending limbs which is available to pre-load descending vessels as they traverse the outer medulla in the vascular bundles. Increased proximal tubule delivery of calcium occurs in some IH patients (31,32) and would increase voltage driven transport out of thick limbs and thence into the descending vasa recta and eventually the papillary capillaries and interstitium (13). Correlation of proximal delivery with direct measurements of interstitial calcium could test this model.

So long as the papillary epithelium remains intact plaque is protected from the urine but once breached urine appears to create nucleations that form the base of an overgrowth (Figure 4, cartoons 3 to 8). What factors might lead to disruption of the urothelial barrier? Is it normal turnover unluckily over plaque? Does plaque somehow disturb the papillary epithelium? Gene and protein expression studies of papillary epithelium over plaque might or not might disclose clues to the process. The urine proteins that form the immediate overlay include THP and osteopontin (27), but the entire suite of proteins remains to be discovered. Are all urine proteins in their native concentrations or are some selected? Which ones? Are these the same in a group of patients or different between patients? Proteomic approaches seem ideal using biopsy materials.

We are aware of proteomic studies of materials eluted from kidney stones (40–47). These are of value in themselves. But being of the bulk phase of the stones they cannot give information about the initial nucleating sites over exposed plaque, which is the critical beginning of an attached stone. For that we must have biopsy materials and micro-techniques.

Successive waves of nucleation and matrix may represent the same proteins or a changing array of proteins from urine; this latter is very important because perhaps changes of matrix are what permit conversion from HA to CaOx that makes up the bulk of the stones. The HA nucleation is unexplored; needed are studies of the proper urine protein ensembles exposed to solutions made up to resemble the ionic composition of urine. No doubt the matrix molecules control the nucleation and may vary from person to person. As for the particles themselves, why is the overlay layered? Does it reflect waves of SS? Is it some alteration of matrix composition? The specific composition of alternating layers, especially those with and without HA crystals should be accessible to modern proteomic and immuno-TEM approaches.

Most mysterious of all is eventual conversion of nucleation from HA to CaOx. Possibly the pH within the matrix changes as one moves away from the tissues. Possibly the matrix changes. This should be accessible not only from tissue biopsies but from stones whose layers include the early HA and later CaOx nuclei. Put perhaps most directly, why does CaOx have to appear at all? If the beginning of the stone is all HA, why can this beginning not merely progress to HA stones as a rule?

One might say that growth of HA/CaOx stones over plaque is so incompletely understood that many if not all of the researches we have mentioned are justified. WIth disclosure of the fine details later work can become refined and eventually this process understood at a molecular and atomic level. Nothing less will move this area of stone research forward. Human tissues should suffice so that the problems of experiment are not to create animal or cell models but to explore what is already produced in human kidneys.

Our group may have been relatively unique in obtaining human papillary biopsies but the techniques we used are commonplace in urological surgery and many research-oriented surgeons can obtain tissue. What we have done that is truly unique and probably necessary is demand as much strictness as possible in defining the clinical phenotype under study. We have published evidence for much variability of tissue between clinical phenotypes, which must be controlled by selection of patients if chaos is to be avoided.

Although overgrowth on plaque occurs in people who produce brushite or HA stones (11,48), completely different phenotypes from ICSF, the process may not be the same in such patients as in ICSF. LIkewise overgrowth of CaOx on plaque occurs in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism, ileostomy, and small bowel resection (7–9). Patients with these systemic diseases do not have familial stones as do ICSF and idiopathic brushite and HA stone formers. Differences in plaque composition, matrix, and all other details of the process could be crucial for understanding this disease mechanism and the role of heredity, if any.

Bellini Duct plugging

Source of clinical stones

Although certainly not uncommon among stone formers, BD plugs have not as yet been proven as a source of clinical human stones. One might naturally assume that the open face of such plugs, bathed perpetually by urine and therefore exposed to CaOx and CaP SS of considerable magnitude (49,50), would foster nucleation of HA and CaOx thus producing an attached nascent stone that subsequently detaches and grows into a clinically important object. As attractive as this formulation might be, evidence for it is scanty at best.

BD plugs present to the surgeon as dilated BD filled with crystals (Figure 5 panel a). Sometimes crystals grow over the plugs into the urinary space (Figure 5 panels a and b). The rounded overgrowths on plugs from an HA and BR stone former respectively, are about 1–2 mm (figure 6, images a-d). Imaginably such overgrowths could detach and grow within a calyx to reach 3 or more mm and present as passage of a stone.

Figure 5. Endoscopic and histologic images from brushite stone formers.

Papilla from BR patients (panel a) often showed depressions (arrows) near the papillary tip and flatting, a phenomenon not seen in the CaOx stone formers. Like CaOx patients, the papilla from brushite stone formers possessed sites of Randall’s plaque (arrowheads), though less in amount. In addition, the papilla possessed sites of yellowish crystalline deposit at the openings of ducts of Bellini (asterisk). These ducts were usually enlarged and occasional filled with a crystalline material that protruded from the duct that might serve as a site for stone attachment. Panel b shows crystal deposition in a papillary biopsy stained by the Yasue method. Note crystal deposits in the lumens of individual inner medullary collecting ducts (arrows) and an occasional nearby loop of Henle. The crystal deposits have greatly expanded the lumen of these tubules and induced cell injury to complete cell necrosis in all of these same tubules. A cuff of interstitial inflammation and fibrosis accompanies sites of intra luminal disposition. Panel c shows a third (type 3) pattern of crystal deposits in papillary biopsies of brushite stone formers. Yellowish mineral deposition (single arrows) was found within lumens of medullary collecting ducts just like that described at the opening of ducts of Bellini, except that the type 3 deposits are located in collecting ducts just beneath the urothelium. Sites of type 3 deposits ranged from large areas of crystal deposition in collecting tubules that formed a spoke and wheel-like pattern around the circumference of the papilla to small, single sites of yellowish material in focal regions of a collecting duct lumen. Histologic analysis of the type 3 deposits (panel d) confirms that these sites of crystal deposition are in medullary collecting ducts (asterisk) positioned just beneath the urothelial lining (arrow). The double arrow shows a site of interstitial crystal deposition like that seen in idiopathic CaOx stone formers. Panel’s e and f were obtained from a papillary biopsy collected from a brushite patient here the gross morphology if all papilla was severely injured. Extensive regions of interstitial fibrosis surround the injured collecting ducts (double arrows). Entrapped injured thin loops of Henle and vasa recta (*) are noted in these fields of interstitial fibrosis. A series of crystalline-filled collecting tubules (arrow) are seen embedded in a small ring of fibrotic tissue. An occasional giant cell (arrowheads) was observed near damaged collecting ducts.

Figure 6. High resolution micro-CT images of the BD plugs with overgrowths.

Panels a, c, e, and g show a light micrograph of a BD plug with overgrowth region from an apatite, brushite, Ileostomy, and primary hyperparathyroidism stone patient respectively. Panels b, d, f, and h show a corresponding micro-CT image generated from 3D image stacks rendered for surface view and then sized for internal view from each of the plug/overgrowth structure. A dotted line demarks the region of the plug from the overgrowth which would occur at the opening of the duct of Bellini. The mineral forming the plugs from apatite (panel a–b), and primary hyperparathyroid (panels g–h) is entirely apatite. The plug from the brushite patient (panels c–d) is a mixture of brushite, apatite and CaOx while the plug from the ileostomy (panels e–f) is apatite and urates. The overgrowth regions from apatite and primary hyperthyroid patients are primarily concentric layers of apatite, entirely CaOx for ileostomy patients and a mixture of CaOx and and BR for BR patients.

The high resolution micro-CT images of the plugs (Figure 6, right hand series) show only HA for both the plug and overgrowth in the HA stone former (Figure 6, images a and b) and BR with a thin surface layer of CaOx for the overgrowth with a mixture of CaOx, BR, and HA for the base of the plug from the BR stone former (Figure 6, images c and d; Plug and overgrowth compositions are detailed in the legend to this figure and for all phenotypes in Table 1). It is therefore quite reasonable that HA and BR stones can originate on plugs, but even so proof is lacking at this point.

TABLE 1.

COMPOSITION OF STONES, BD PLUGS, OVERGROWTHS ON PLUGS AND DUCTAL STONES IN 10 STONE FORMER PHENOTYPES AND URINARY SUPERSATURATIONS FOR CAOX, CAP AND UA

| PHE NO- TYPE |

N | STONES ON PLAQUE |

DUCTAL STONES |

OTHER STONES |

BD PLUGS |

OVER- GROWTH ON PLUGS |

SS CAOX |

SS CAP |

SS UA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICSF | 30 | CAOX/HA | - | HA (1/7) | ? | 10.2 ± 0.7 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | |

| HA | 9 | CAOX/HA | - | HA/CAOX | HA | HA | 8.5 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| BR | 23 | CAOX/HA | - | BR/CAOX/HA | HA/CAOX/BR | BR | 9 ± 0.7 | 2 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| SBR | 11 | CAOX/HA | - | CAOX | HA | ? | 11.2 ± 2 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| ILEO | 7 | CAOX/HA | - | UA/CAOX | HA/NAU | ? | 8 ± 1.7 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.5 |

| PHPT | 5 | CAOX/HA | - | CAOX/HA/BR | HA | ? | 10.6 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | - |

| BYPASS | 5 | - | - | CAOX | HA/CAOX (TRACE) | NONE | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 0.1 ± 0.02 | 1.1 ± 0.2 |

| RTA | 5 | - | - | HA | HA/CAOX | HA | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.09 ± 0.04 |

| CYSTINE | 7 | - | CYSTINE/HA | CYSTINE | CYSTINE | CYSTINE | 5.1 ± 1 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| PH1 | 8 | - | - | CAOX | CAOX | CAOX | - | - | - |

An obvious question is how one might know if a stone originated as the overgrowth over a BD plug. One possibility is that a stone attached to a papillum is found to be attached not on white plaque but to a BD plug. This would be evident to the surgeon and on intra-operative movies because as the stone was detached the area it grew on was not plaque but a dilated BD. Likewise the stone must have remnants of the plug at one border - where it was attached. We have not as yet observed removal of such a stone, but in fairness this has not been a specific surgical research aim.

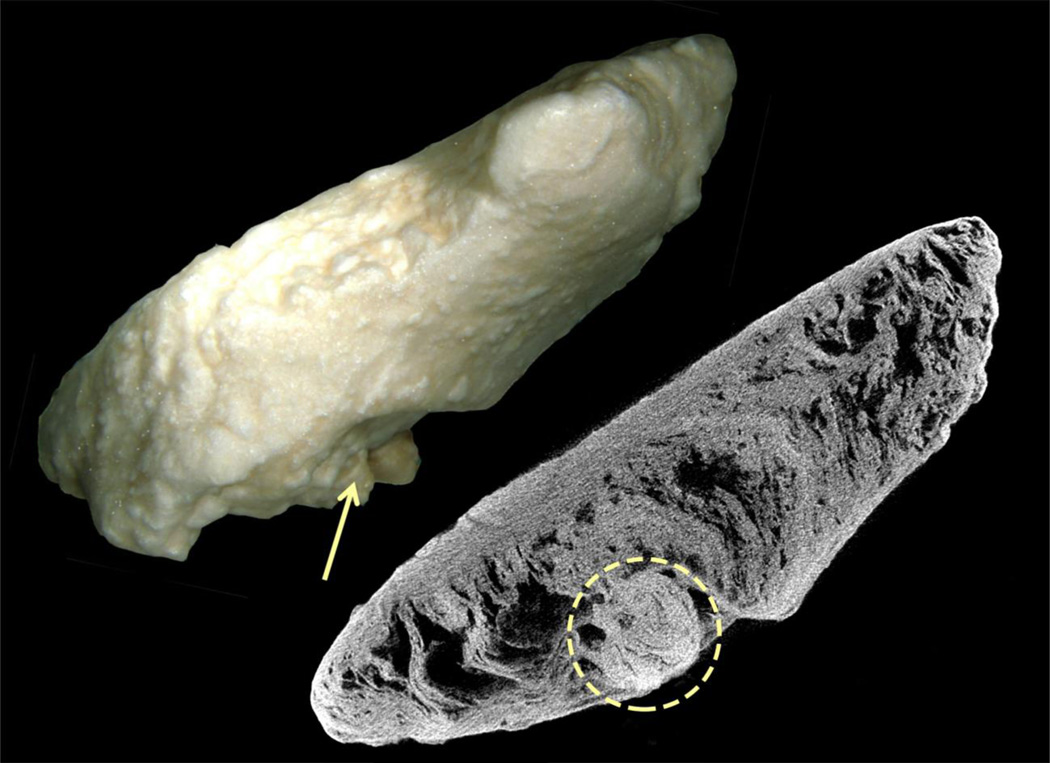

Another possibility is that an overgrowth has detached and is free in the calyx or pelvis, grows into a clinically relevant stone and is removed. Within that stone one might predict the ghost remnant of the plug or overgrowth around which layers of new mineral have created from a tiny overgrowth a larger stone. On study of our collection of stones we have found one example of such a ghost thus far (Figure 7). This renal pelvis stone from a patient with PHPT is 2 cm in length, 5 mm in width. On CT scanning a round inclusion was found (arrow and ring) which is HA and heterogeneous with respect to the rest of the stone. Possibly this was the original plug because its layers of HA are like those of plugs in being nodular vs the concentric rings of most stones as is seen here. Careful study of stones for heterogeneous inclusions may help clarify the question of whether BD plugs or overgrowths may be important stone nuclei.

Figure 7. Pelvic stone that possibly started as an overgrowth on a BD plug.

This figure shows a long (about 2 cm) and slender renal pelvic stone removed from a patient with primary hyperparathyroidism and viewed by light microscopy and micro-CT. By CT the stone is seen as composed of apatite with a round inclusion region (denoted by arrow and ring) at one side of the stone. Possibly this inclusion region was the original plug because its layers of HA are like those of plugs in being nodular vs the concentric rings of most stones as is seen here.

Mechanisms for overgrowth on plugs

Overgrowth on plug surfaces is altogether unstudied even though Randall recognized the process (22). Like overgrowth on plaque, the only factors that seem available to control overgrowth on BD plugs must be the plug composition, urine SS values, and the urine molecules that deposit over plugs to create the matrix for overgrowth. The urine molecules that must cover the open face of BD plugs are unknown (13,14). Actual plugs with their overgrowths can be harvested and perhaps studied directly in their longitudinal dimension for matrix molecules and their relationship to crystals. Stones have been studied for their matrix (51,52) but not usually in an oriented manner like this one. Although we may be the first group to harvest BD plugs with their attached overgrowths, other surgeons can in principle do the same.

SS itself is not sufficient to explain the crystal composition of plugs and overgrowths. For example, both BR and HA stone formers have high urine CaP SS with respect to BR but the plugs of the former are composed of BR, CaOx and HA (Table 1) whereas those of the later are pure HA. Moreover, the overgrowth on plugs is BR in the former and HA in the latter (Table 1).

Papillary injury

Apart from stone genesis one significance of BD plugs is papillary injury from plugging. The injury plugs produce is obvious (Figure 5 panels e and f). The tubule epithelium can be completely destroyed so that crystals attach to the tubule basement membranes; dilation of BD may approach 20 fold normal. Around plugs the interstitium shows fibrosis, and hyaluronan expression - a mark of injury - occurs in epithelia of more modestly involved tubules and even of normal appearing tubules near plugged tubules (6,10). In some patients plugging extends into the IMCD; seen along their long axes through the papillary epithelium IMCD plugs appear as yellow cylinders, which we have called ‘yellow plaque’ (Figure 5 panels c and d).

Cortical injury

Whereas ICSF cortices reveal virtually no pathology above that found in random people (Figure 8), cortices from HA and BR stone formers often show fibrosis, which could reflect procedures, such as SWL, or plugging. This question, the cause of the cortical injury, needs more study not so much with cutting edge bench techniques as with clinical research that attempts to dissociate cortical injury from the effects of treatments. Cortical injury occurs in all of the BD plugging states we have studied to date (1–11). But, of course, all of these patients may have been exposed to treatments such as SWL and PERC which themselves injure the renal cortex (53–55).

Figure 8. Cortical Interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy and glomerulosclerorsis in brushite (black circles), apatite (open circles) and ICSF (black triangles).

Left panel. After scoring cortical biopsies from BR, apatite and ICSF stone formers for interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy and glomerular injury, the highest score for interstitial or tubular atrophy was plotted on the x-axis and glomerular injury on the y axis for each phenotype. Out of 30 cases plotted, only 2 ICSF had interstitial changes above a score of 1, and none had significant glomerular disease with a glomerular score above 1, while 4/11 apatite and 12/25 BRSF had significant cortical injury. Right Panel’s a–c shows the range of interstitial (arrows), tubular and glomerular (G) changes seen by light microscopy in the apatite and brushite patients. Panel a shows the cortex of an apatite patient with mild interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (score = 1) and no glomerulosclerorsis while panel b shows an apatite patient with moderate interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy and glomerulosclerorsis (score =2). Panel c shows the cortex of a brushite patient with severe interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy and glomerulosclerorsis (score =3).

Mechanisms for BD and IMCD plugging - animal and in vitro models

The process of BD and IMCD plugging has been studied in animals with oxalate nephropathy; crystal deposition in cortex has been studied in human transplant kidneys and phosphate nephropathy (56). Phosphate nephropathy and transplant crystals involve proximal and distal tubules, but papillary involvement is not documented because biopsies do not include that portion of the kidney (57). Whereas the IMCD and BD of animal oxalate loading models are filled with CaOx crystals (21,56,58–60), this is only seen in human PH1 (10) and is not a model of ICSF or any other human stone disease, in which tubule crystals are mainly composed of HA.

What we have learned from renal cortex transplant crystals, cortical crystals in phosphate nephropathy, and from animal oxalate loading models is some idea about cell responses to crystals, and the cell injury mediators involved (56,61). But whether this knowledge translates into the BD plugging that occurs in common human stone diseases is unknown. For example, cortical renal cells may well respond to crystals in a manner far different from those lining the IMCD and BD. Likewise, CaOx crystals may well affect IMCD and BD cells differently from HA crystals, and rodent cells may respond differently from human cells. Moreover, phosphate nephropathy, transplant crystal deposition, and oxalate loading models in animals represent relatively acute crystal injuries compared to the much longer term evolution of a human disease that is known to occur over decades and is rarely associated with acute kidney injury with the exception of PH1.

Knockout mouse models are informative but likewise depart radically from human stone formers. SLC26a6 knockout mice develop hyperoxaluria, and in one knockout plugging occurs in proximal and distal tubules and stones are present in the renal pelvis (62). The other knockout with equivalent hyperoxaluria develops no crystal deposits or stones. NHERF knockout causes hypercalciuria and production of some papillary plaque and tubule plugging with HA in papillum (63). THP knockout produces plugging in the IMCD that gives way to plaque formation in the papillum (64). The latter two models have a potential to permit detailed studies of plaque, which have not as yet been exploited.

All of these models have immense potential to improve understanding of human stone formation and plugging but this cannot be realized until we have enough detailed knowledge of the human condition to link the animal and human findings together at a molecular and cellular level. Put another way if we do not know exactly what is happening in the human tissues at this level, how can we confidently interpret animal models?

Likewise for the many in vitro studies of crystal attachment to cell cultures derived from kidneys (65–68). In general these studies have established that crystals attach to cells at specific sites, cells respond to the crystals, may internalize them, and either break them down in their lysosomes or transport them to their basement membranes (56,61). However, the cells are not always relevant to BD and IMCD plugging, having been derived from proximal or distal cortical nephron which are certainly not the same as IMCD and BD cells that have a different embryological origin. The crystals have often been CaOx whereas HA is more pertinent. The amounts of crystals, this being in vitro work, have often far exceeded what one might expect in a human BD or IMCD.

Mechanisms for BD and IMCD plugging - Human plug formation

The sequence of events that initiates human BD plugging is not well defined even though we have considerable information about the tissues after the process is established. An appealing idea derived from cell culture work is that SS drives crystallizations, and some kind of tubule cell injury exposes hyaluronan rich areas of the membrane to the tubule fluid so that crystals may anchor there (69). Evidence for this in humans has come from studies of transplant kidney crystals in cortex (70) but no human studies have shown it in papillum except our own in which hyaluronan expression was found in cortex and papillum in the absence and presence of crystals in patients with PH1 (10), and in the papillum of those with CaOx stones from obesity bypass (6). Hyaluronan expression was never found in papillae of ICSF even in regions of plaque. Other plug forming stone diseases have not as yet been studied in this detail.

The range of clinical stone phenotypes with BD plugs is very large. ICSF can have them (15) but their compositions is not as yet determined (Table 1). HA and BR stone formers always display plugging (Table 1, Figure 6 images a to d). Ileostomy, and primary hyperparathyroidism (Table 1, Figure 6, images e to h) each form complex plugs and overgrowths. Distal renal tubular acidosis, small bowel resection, obesity bypass, cystinuria, and PH1, are additional examples (1,3,5,9,10) in which plugging can be prominent, but we do not have examples of plugs and overgrowth to display.

Urine SS is easily measured and some progress has been made associating plug formation and CaP stone disease with higher urine pH (13), but SS values are not a sufficient explanation for the variety of crystals found in plugs and overgrowths. In ileostomy, plugs are urates and HA whereas urine pH hovers around 5 so that driving forces for urate salts and HA are absent (8). Small bowel resection causes HA plugs despite high CaOx SS and low CaP SS (9). It is true that SS values tend to associate with their predicted clinical stones - e.g. CaP SS with HA or BR stones (11) - but association with plugging is so poor in ileostomy and small bowel resection that other mechanisms must dominate the process. In dRTA, the paradigm of alkaline urine CaP stone formation (5) plugging is massive and mainly HA, but CaP SS is not as high as in BR stone formers who have much smaller numbers of plugs (Table 1). Pursuit of more basic understanding of plugging mechanisms in human tissues needs to go far beyond simple SS and crystallization.

IMCD stones

Thus far only observed in cystinuria these are unattached round tiny ‘stones’ within dilated IMCD () (Figure 9). Micro-liths of cystine about 1 to 2 mm in diameter are present at the distal ends of IMCD and are easily removed if the IMCD is unroofed with a laser (Figure 9, panels a and b). BD can be plugged with cystine, but without attachment of plugs within their tubules, so the plugs can be removed without force (3) and the epithelium remains intact. This contrasts with all other BD plugs. Because they are round and unattached, formation in free solution is an obvious idea for cystinuria.

Figure 9. Endoscopic unroofing of an IMCD ductal stone in cystinuric stone former.

Micro-liths of cystine are present at the distal ends of IMCD and are easily seen at the time of percutaneous nephrolithotomy to lie under the urothelium at a site marked by a dark shadow (arrow) on a dilated duct (panel a). When the IMCD is unroofed with a laser (panel b), an unattached, round tiny ‘stone’ is exposed (double arrow) within dilated IMCD at easily flows out of the IMCD lumen.

Free Solution formation apart from IMCD stones

At surgery one commonly finds myriads of unattached stones filling calyces and even the renal pelvis with no evidence on the stones of an attachment site. We refer here to the CaOx stones in PH1 and obesity bypass, most BR and HA stones, and all cystine stones (Figure 10). In what ways is it possible even in principle to test and falsify the free solution hypothesis? To us this seems an ultimate challenge to the stone research community.

Figure 10. Cystine stones may be example of kidney stones formed in ‘free solution’.

While numerous unattached stones are seen at the time stone removal by percutaneous nephrolithotomy or ureteroscopy only the stones from cystinuric patients have consistent characteristics of a stone formed in ‘free solution’ (panel a). The cystine stones look like ‘Easter eggs” in that they are completely smooth, oval in shape, have a homogenous yellow coloration and are freely floating in a renal calyx. They are easily grasped and removed (panel b).

In the case of IMCD microliths, in cystinuria, stagnant urine is available as a breeding ground. But for the rest, the stones mentioned in the preceding paragraph, what would free solution formation mean? To us it would imply nucleation in urine, perhaps within a calyx, with some means for retention so that growth can occur. This theory is very close, in fact, to the plugging overlay hypothesis, in that the latter holds that tiny overlays are retained and grow. A commonly held speculation is that cell debris is shed from the renal pelvis and serves as an anchor and nucleation site (68).

Certainly crystals are forming in urine perhaps much of the time as all of us have found them during routine urinalysis. But none of us has ever observed these crystals becoming stones; all we have is the idea that somehow this may occur. The problem is that lacking a powerful means of experimental disproof this idea is not scientific but essentially metaphysical. For this reason, every effort is justified to work out new ways of testing mechanisms of clinical stone formation apart from growth on plaque and possibly as overgrowths on plugs.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIG grant P01 DK-56788.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Evan AP, Lingeman JE, Coe FL, Parks JH, Bledsoe SB, Shao Y, Sommer AJ, Patterson RF, Kuo RL, Grynpas M. Randall Plaque of patients with nephrolithisis begins in basement membranes of thin loops of Henle. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:607–616. doi: 10.1172/JCI17038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evan AP, Lingeman JE, Coe FL, Shao Y, Parks JH, Bledsoe SB, Phillips CL, Bonsib S, Worcester EM, Sommer AJ, Kim SC, Tinmouth WW, Grynpas M. Crystal-associated nephropathy in patients with brushite nephrolithiasis. Kidney Int. 2005;67:576–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evan AP, Coe FL, Lingeman JE, Shao Y, Matlaga BR, Kim SC, Bledsoe SB, Sommer AJ, Grynpas M, Philips CL, Worcester EM. Renal crystal deposits and histopathology in patients with cystine stones. Kidney Int. 2006;69:2227–2235. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evan A, Lingeman J, Coe FL, Worcester E. Randall's plaque: pathogenesis and role in calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1313–1318. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evan AP, Lingeman J, Coe F, Shao Y, Miller N, Matlaga B, Phillips C, Sommer A, Worcester EM. Renal histopathology of stone-forming patients with distal renal tubular acidosis. Kidney Int. 2007;71:795–801. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evan AP, Coe FL, Gillen D, Lingeman JE, Bledsoe S, Worcester EM. Renal intratubular crystals and hyaluronan staining occur in stone formers with bypass surgery but not with idiopathic calcium oxalate stones. Anat Rec. 2008;291:325–334. doi: 10.1002/ar.20656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evan AP, Lingeman JE, Coe FL, Miller N, Bledsoe S, Sommer A, Williams J, Shao Y, Worcester E. Histopathology and surgical anatomy of patients with primary hyperparathyroidism and calcium phosphate stones. Kidney Int. 2008;74:223–229. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evan AP, Lingeman JE, Coe FL, Bledsoe SB, Sommer AJ, Williams JC, Jr, Krambeck AE, Worcester EM. Intra-tubular deposits, urine and stone composition are divergent in patients with ileostomy. Kidney Int. 2009;76:1081–1088. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evan AP, Lingeman JE, Worcester EM, Bledsoe SB, Sommer AJ, Williams JC, Jr, Krambeck AE, Phillips CL, Coe FL. Renal histopathology and crystal deposits in patients with small bowel resection and calcium oxalate stone disease. Kidney Int. 2010;78:310–317. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Worcester EM, Evan AE, Coe FL, Lingeman JE, Krambeck A, Sommer A, Philips CL, Milliner D. A test of the hypothesis that oxalate secretion produces proximal tubule crystallization in primary hyperoxaluria Type 1. AJP. 2013;305:F1574–F1584. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00382.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evan AP, Lingeman J, Worcester EM, Sommer AJ, Phillips CL, Williams JC, Coe FL. Contrasting histopathology and crystal deposits in kidneys of idiopathic stone formers who produce hydroxy apatite, brushite, or calcium oxalate stones. In Press: Anat Rec. 2013 doi: 10.1002/ar.22881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller NL, Gillen DL, Williams JC, Evan AP, Bledsoe SB, Coe FL, Worcester EM, Matlaga BR, Munch LC, Lingeman JE. A formal test of the hypothesis that idiopathic calcium oxalate stones grow on Randall’s plaque. BJU Intl. 2009;103:966–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coe FL, Evan AP, Lingeman JE, Worcester EM. Plaque and deposits in nine human stone diseases. Urol Res. 2010;38:239–247. doi: 10.1007/s00240-010-0296-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coe FL, Evan AP, Worcester EM, Lingeman JE. Three pathways for human kidney stone formation. Urol. Res. 2010;38:147–160. doi: 10.1007/s00240-010-0271-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linnes MP, Krambeck AE, Cornell L, Williams JC, Korinek M, Bergstrald EJ, Rule AD, McCollough CM, Vritiska TJ, Lieske JC. Phenotypic characterization of kidney stone formers by endoscopic and histological quantification of intra-renal calcifications. Kidney Intl. 2013;84:818–825. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan SR, Finlayson B, Hackett RL. Renal papillary changes in patient with calcium oxalate lithiasis. Urology. 1984;23:194–199. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(84)90021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Low RK, Stoller ML. Endoscopic mapping of renal papillae for Randall’s plaques in patients with urinary stone disease. J Urol. 1997;158:2062–2064. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)68153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verkoelen CF, Verhulst A. Proposed mechanisms in renal tubular crystal retention. Kidney Int. 2007;72:13–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vermeulen CW, Lyon ES. Mechanisms of genesis and growth of calculi. Am J Med. 1968;45:684–692. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(68)90204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finlayson B, Reid F. The expectation of free and fixed particles in urinary stone disease. Invest Urol. 1978;15:442–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kok DJ, Khan SR. Calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis, a free or fixed particle disease. Kidney Int. 1994;46:847–854. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Randall A. The origin and growth of renal calculi. Ann Surg. 1937;105:1009–1027. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193706000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller NL, Williams JC, Evan AP, Bledsoe SB, Coe FL, Worcester EM, Munch LC, Handa S, Lingeman JE. In idiopathic calcium oxalate stone formers, unattached stones show evidence of having originated as attached stones on Randall’s plaque: A micro CT study. BJU Int. 2010;105:242–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08637.x. PMC2807918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henneman PH, Benedict PH, Fotbes A, Dudley R. Idiopathic hypercalcuria. N Engl J Med. 1958;259:802–907. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195810232591702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coe FL, Evan E, Worcester E. Kidney stone disease. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2598–2608. doi: 10.1172/JCI26662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evan AP. Histopathology predicts the mechanism of stone formation. In: Evan AP, Lingeman JE, Williams JC, editors. Renal Stone Disease: Proceedings of the First International Urolithiasis Research Symposium. Melville, NY: American Institute of Physics; 2007. pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evan AP, Coe FL, Lingeman JE, Shao Y, Sommer AJ, Bledsoe SB, Anderson JC, Worcester EM. Mechanism of formation of human calcium oxalate renal stones on Randall’s plaque. Anat Rec. 2007;290:1315–1323. doi: 10.1002/ar.20580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gokhale JA, McKee MD, Khan SR. Immunocytochemical localization of Tamm-Horsfall protein in the kidneys of normal and nephrolithic rats. Urol Res. 1996;24:201–209. doi: 10.1007/BF00295893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asplin JR, Mandel NS, Coe FL. Evidence for calcium phosphate supersaturation in the loop of Henle. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:F604–F613. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.270.4.F604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jamison RL, Frey NR, Lacy FB. Calcium reabsorption in the thin loop of Henle. Am J Physiol. 1974;227:745–751. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1974.227.3.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bergsland KJ, Worcester EM, Coe FL. Role of proximal tubule in the hypocalciuric response to thiazide of patients with idiopathic hypercalciuria. Am J Physiol. 2013;305:F853–F860. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00116.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Worcester EM, Coe FL, Evan AP, Bergsland KJ, Parks JH, Willis LR, Clark DL, Gillen DL. Evidence for increased postprandial distal nephron calcium delivery in hypercalciuric stone-forming patients. Am J Physiol. 2008;295:F1286–F1294. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90404.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Worcester EM, Gillen DL, Evan AP, Parks JH, Wright K, Trumbore L, Nakagawa Y, Coe FL. Evidence that postprandial reduction of renal calcium reabsorption mediates hypercalciuria of patients with calcium nephrolithiasis. Am J Physiol. 2007;292:F66–F75. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00115.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brannan PG, Morawski S, Pak CY, Fordtran JS. Selective jejunal hyperabsorption of calcium in absorptive hypercalciuria. Am J Med. 1979;66:425–428. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(79)91063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Broadus AE, Dominguez M, Batter FC. Pathophysiological studies in idiopathic hypercalciuria: use of an oral calcium tolerance test to characterize distinctive hypercalciuric subgroups. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1978;47:751–760. doi: 10.1210/jcem-47-4-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evan AP, Bledsoe S, Worcester EM, Coe FL, Lingeman JE, Bergsland KJ. Renal inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain 3 increases in calcium oxalate stoneforming patients. Kidney Intl. 2007;72:1503–1511. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evan AP, Coe FL, Rittling SR, Bledsoe SM, Shao Y, Lingeman JE, Worcester EM. Apatite plaque particles in inner medulla of kidneys of calcium oxalate stone formers: osteopontin localization. Kidney Intl. 2005;68:145–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khan SR, Rodriguez DE, Gower LB, Monga M. Association of Randall plaque with collagen fibers and membrane vesicles. J Urol. 2012;187:1094–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.10.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bost F, arra-Mehrpour M, Martin JP. Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor proteoglycan family – a group of proteins binding and stabilizing the extracellular matrix. Eur J Biochem. 1998;252:339–346. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2520339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merchant M, Cummins T, Wilkey D, Salyer S, Powell D, Klein J, Lederer ED. Proteomic analysis of renal calculi indicates an important role for inflammatory processes in calcium stone formation. Am J Physiol. 2008;295:F1254–F1258. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00134.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Canales B, Anderson l, Higgins L, Slaton J, Roberts K, Liu N, Monga M. Second prize: Comprehensive proteomic analysis of human calcium oxalate monohydrate kidney stone matrix. J Endourol. 2008;22:1161–1167. doi: 10.1089/end.2007.0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mushtaq S, Siddiqui A, Naqvi Z, Rattani A, Talati J, Palmberg C, Shafqat J. Identification of myeloperoxidase, alpha-defensin and calgranulin in calcium oxalate renal stones. Clin Chim Acata. 2007;384:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaneko K, Yamanobe T, Nakagomi K, Mawatari K, Onoda M, Fujimori S. Detection of protein Z in a renal calculus composed of calcium oxalate monohydrate with the use of liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry followingtwo dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis separation. Anal Biochem. 2004;324:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaneko K, Yamanobe T, Onoda M, Mawatari K, Nakagomi K, Fujimori S. Analysis of urinary calculi obtained from a patient with idiopathic hypouricemia using micro area x-ray diffractometry and LC-MS. Urol Res. 2005;33:415–421. doi: 10.1007/s00240-005-0480-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaneko K, Kobayashi R, Yasuda M, Izumi Y, Yamanobe T, Shimizu T. Comparison of matrix proteins in different types of urinary stone by proteomic analysis using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Int J Urol. 2012;19:765–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2012.03005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jou YC, Fang CY, Chen SY, Chen FH, Cheng MC, Shen CH, Liao LW, Tsai YS. Proteomic study of renal uric acid stone. Urology. 2012;80:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams JC, Jr, McAteer JA, Evan AP, Lingeman JE. Micro-computed tomography for analysis of urinary calculi. Urol Res. 2010;38:477–484. doi: 10.1007/s00240-010-0326-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Asplin JR, parks JH, Coe FL. Dependence of upper limit of metastability on supersaturation in nephrolithiasis. Kidney Intl. 1997;52:1602–1608. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parks JH, Coward M, Coe FL. Corresondence between stone composition and urine supersaturation in nephrolithiasis. Kidney Intl. 1997;51:894–900. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boyce WH. Organic matrix of human urinary concretions. Am J Med. 1968;45:673–683. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(68)90203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boyce W, Garvey FK. The amount and nature of organic matrix in urinary calculi: a review. J Urol. 1956;76:213–227. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)66686-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Willis LR, Evan AP, Connors BA, Blomgren PM, Fineberg N, Lingeman JE. Relationship between kidney size, renal injury, and renal impairment induced by shock wave lithotripsy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:1753–1762. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1081753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Evan A, Willis L, Lingeman J, McAteer J. Renal trauma and the risk of long-term complications in shock wave lithotripsy. Nephron. 1998;78:1–8. doi: 10.1159/000044874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McAteer JA, Evan AP. The acute and long-term adverse effects of shock wave lithotripsy. Sem Nephrol. 2008;28:200–213. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vervaet BA, Verhulst A, Dauwe SE, De Broe ME, D’Haese PC. An active renal crystal clearance mechanism in rat and man. Kidney Intl. 2009;75:41–51. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jennette JC, Falk RJ. Glomerular clinicopathologic syndrome. In: Greeburg A, CHenug AK, editors. Primer in kidney disease. Saunders, Philadelphia: 2005. pp. 150–169. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khan SR, Hackett RL. Calcium oxalate urolithiasis in the rat: is it a model for human stone disease? A review of recent literature. Scan Electron Micros. 1985;2:759–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khan SR, Shevock PN, Hackett Rl. Acute hyperoxaluria, renal injury and calcium oxalate urolithiasis. J Urol. 1992;147:226–230. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khan SR. Nephrocalcinosis in animal models with and without stones. Urol Res. 2010;38:429–438. doi: 10.1007/s00240-010-0303-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vervaet BA, Verhulst A, D’Haese PC, De Broe ME. Nephrocalcinosis: new insights into mechanisms and consequences. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2030–2035. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jiang Z, Asplin JR, Evan AP, Rajendran VM, Velazquez H, Notttoli TP, Binder HJ, Aronson PS. Calcium oxalate urolithiasis in mice lacking anion transporter Slc26a6. Nat Genet. 2006;38:474–478. doi: 10.1038/ng1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Evan AP, Weinman EJ, Wu XR, Lingeman JE, Worcester EM, Coe FL. Comparison of the pathology of interstitial plaque in human ICSF stone patients to NHERF-1 and THP-null mice. Urol Res. 2010;38:439–452. doi: 10.1007/s00240-010-0330-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu Y, Mo L, Goldfarb DS, Evan AP, Liang F, Khan SR, Lieske JC, Wu XR. Progressive renal papillary calcification and ureteral stone formtion in mice deficent for Tamm-Horsfall protein. Am J Physiol. 2010;299:F469–F478. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00243.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Verkoelen CF, van der Boom BG, Houtsmuller AB, Schroder FH, Romijn JC. Increased calcium oxalate monohydrate crystal binding to injured renal tubular epithelial cells in culture. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:F958–F965. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.5.F958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Verkoelen CF, van der Boom BG, Kok DJ, Houtsmuller AB, Viser P, Schroder FH, Romijn JC. Cell type-specific acquired protection from crystal adherence by renal tubule cells in culture. Kidney Intl. 1999;55:1426–1433. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wiessner JH, Hasegawa AT, Hung LY, Mandel GS, Mandel NS. Mechanisms of calcium oxalate crystal attachment to injured renal collecting duct cells. Kidney Intl. 2001;59:637–644. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.059002637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Khan SR, Thamilselvan S. Nephrolithiasis: a consequence of renal epithelial cell exposure to oxalate and calcium oxalate crystals. Mol Urol. 2000;4:305–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Verhulst A, Asselman M, Persy VP, Schepers MS, Helbert MF, Verkoelen CF, De Broe ME. Crystal retention capacity of cells in the human nephron: Involvement of CD44 and its ligands hyaluronic acid and osteopontin in the transition of a crystal binding- into a nonadherent epithelium. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:107–115. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000038686.17715.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Verhulst A, Asselman M, De Naeyer S, Vervaet BA, Mengel M, Gwinnwr W, D’Haese PC, Verkoelen CF, Be Broe ME. Preconditioning of the distal tubular epithelium of the human kidney precedes nephrocalcinosis. Kidney Intl. 2005;68:1643–1647. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Parks JH, Coe FL. Evidence for durable kidney stone prevention over several decades. BJU Int. 2009;103:1238–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]