Abstract

Reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton is essential for cell motility and chemotaxis. Actin-binding proteins (ABPs) and membrane lipids, especially phosphoinositides PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 are involved in the regulation of this reorganization. At least 15 ABPs have been reported to interact with, or regulated by phosphoinositides (PIPs) whose synthesis is regulated by extracellular signals. Recent studies have uncovered several parallel intracellular signalling pathways that crosstalk in chemotaxing cells. Here, we review the roles of ABPs and phosphoinositides in chemotaxis and cell migration.

Linked Articles

This article is part of a themed section on Cytoskeleton, Extracellular Matrix, Cell Migration, Wound Healing and Related Topics. To view the other articles in this section visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2014.171.issue-24

Tables of Links

| TARGETS |

|---|

| Enzymesa |

| PI3Kγ |

| PLCβ2 |

| PTEN phosphatase |

| SHIP1, (INPP5D) |

| GPCRsb |

| CCR5 |

| CXCR4 |

| Ligand-gated ion channelsc |

| IP3 receptors |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (a,b,cAlexander et al., 2013a,b,c,,).

| LIGANDS |

|---|

| C5a, complement component |

| cAMP |

| fMLP, formylMet-Leu-Phe |

| IL-8 |

| IP3, inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate; |

| LTB4 |

| PI(3,4,5)P3, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate, PIP3 |

| PI(4,5)P2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; PIP2 |

Introduction

Cells can sense external chemical concentration gradients and move towards the higher concentrations in the gradient. This migration process is called chemotaxis. It is important for a variety of physiological events, such as axon guidance (Henle et al., 2013), wound healing (Martins et al., 2012) and tissue morphogenesis (McLennan et al., 2012). Moreover, immune cells traffic between the vascular and lymphatic systems and migrate from the blood towards sites of infection (Hespel and Moser, 2012). In addition to these roles in normal physiology, many human diseases are associated with inappropriate cell migration. For example, tumour cell migration results in cancer metastasis (Ang et al., 2004; 2010,) and unwanted immune-cell chemotaxis causes chronic inflammatory diseases such as asthma and arthritis (Isozaki et al., 2013). In eukaryotic cells, actin assembly provides a major force for cell movement, in particular by driving the membrane protrusions that propel the leading edge (Huang et al., 2013). Chemotaxing cells are morphologically polarized with a leading front and a trailing end. At the front, a continuing growth of actin-network pushes the membrane forward, which leads to pseudopod extension. At the sides and back of the cell, formation of errant pseudopods is suppressed by the cortical actin/myosin II complex. The central question in chemotaxis is how the GPCR/G-protein machinery directs polarized biochemical responses that lead to the growth of the actin-network only at the leading edge of the cell (Jin, 2013).

Actin is a major component of the cytoskeleton system in all eukaryotic cells and is essential for a wide variety of functions such as muscle contraction, cell movement, phagocytosis, cytokinesis and intracellular trafficking (Doherty and McMahon, 2008; Blanchoin et al., 2014). In prokaryotic cells, MreB is an analogue of eukaryotic actin, especially in three-dimensional structure and filament polymerization (Strahl et al., 2014). Actin can be present as either a free monomer called G-actin or as part of a linear polymer microfilament called F-actin, and both are important for cellular functions such as the mobility and contraction of cells during cell division. Polymerization and depolymerization of actin filaments in non-muscle cells are highly regulated. The dynamics of actin filament in these processes are precisely regulated by an array of actin-binding proteins (ABPs) (Ciobanasu et al., 2013). Phosphoinositides (PIPs), especially phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [also known as PI(4,5)P2] and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate [also known as PI(3,4,5)P3], regulate ABP activity and play a crucial role in actin-dependent cellular processes such as cytokinesis, endocytosis, phagocytosis and cell migration. These PIPs usually promote actin polymerization by suppressing the activities of proteins that induce actin disassembly and activate proteins that promote actin assembly (Miki et al., 1996).

The goal of this review is to demonstrate how the PIPs and PIP-binding proteins affect actin cytoskeleton-mediated cell migration and chemotaxis, and how they contribute to specific disease states. Within migrating cells, actin filaments are distributed predominantly at the leading edge underneath the plasma membrane and are highest in concentration at the tips of pseudopodia/lamellipodia (Servant et al., 2000). The last decade has seen the discovery of how the fundamental properties of PIP-binding proteins are harnessed by cells to regulate actin reorganization and then regulate cellular functions. This review is presented in three sections; the first section describes the basic features and the metabolic pathway of the PIPs and their roles in chemotaxis and cell migration. The second section briefly describes the mechanisms of chemotaxis and cell migration in Dictyostelium and mammalian neutrophils. Finally, the third section highlights molecular and biochemical features of actin and its associated proteins, especially those proteins which bind to PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3, and also the pivotal role that the PIP-binding ABP and actin cytoskeleton play in the molecular pathophysiology of disease states.

Basic features and metabolic pathway of PIPs

Basic features of PIPs

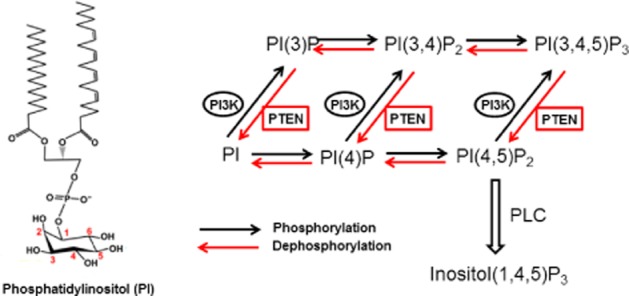

PIPs are phosphorylated derivatives of PI produced by a variety of kinases and phosphatases that makes up their membrane-associated lipid substrates (Figure 1). Phosphorylation occurs in the −OH group of inositol ring which is linked to the position three of the DAG backbone through a phosphodiester bounding using the −OH group of the ring at the D1 position. This myo-inositol head contains five free hydroxyl groups position to be phosphorylated, but only three of them are phosphorylated in vivo (Positions D3, D4 and D5) (Lee et al., 2012). The ratio of inositol phospholipids (composed of PI and PIPs) within cells measured in different cells and tissues shows significant variation (Nasuhoglu et al., 2002; Wenk et al., 2003). Total inositol phospholipid represents 10 to 20% of total phospholipids and is mostly dominated by PI, whereas the contributions of the other PIPs are even smaller. Only approximately 5% of PIPs are phosphorylated at position D4 [PI(4)P], another 5% are phosphorylated at positions D4 and D5[PI(4,5)P2] (Balla et al., 1988), and about 0.25% are phosphorylated at D3 position. This explains why the cellular concentration of PI(3,4,5)P3 is typically at least 25 times lower than that of PI(4,5)P2 (Lemmon and Ferguson, 2000). Among the various PIPs, PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 have played the most important roles in actin cytoskeletal reorganization (Janmey and Lindberg, 2004).

Figure 1.

Reactions catalyzed by PI3K and PTEN. PI3K phosphorylates the D3 position of phosphatidylinositol (PI), PI4P or PI(4,5)P2 to produce PI3P, PI(3,4)P2 or PI(3,4,5)P3 respectively. PTEN has been shown to dephosphorylate the D3 position of both PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 and thus to reverse the reactions catalyzed by PI3K.

PIPs metabolism

PI(4,5)P2 is a major source of three second messengers in cells: diacylglycerol (DAG), inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) and PI(3,4,5)P3. PI(4,5)P2 is the precursor of IP3 and DAG after PLC activation and therefore is crucial for early signalling from cell surface receptors. In addition, PI(4,5)P2 is a substrate of class I PI3Ks and the precursor of PI(3,4,5)P3, this being critical for growth factor signalling and also plasma membrane polarization and membrane dynamics (Figure 1).

Canonical PIP signalling transduced by cell surface receptors

Studies uncovering the connection between receptor-mediated stimulation of ‘PIP turnover’ and Ca2+ signalling placed PIPs in the centre of attention in the early 1980s, and this knowledge has become part of every textbook of cell biology. This will be summarized only briefly for the sake of completeness. PLC cleaves the PI(4,5)P2 into DAG and IP3 (Berridge, 1984; Berridge and Irvine, 1984). DAG remains bound to the membrane, and IP3 is released as a soluble structure into the cytosol. IP3 then diffuses through the cytosol to bind to IP3 receptors, particularly calcium channels in the smooth endoplasmic reticulum (O'Rourke et al., 1985). This causes the cytosolic concentration of calcium to increase, which leads to a cascade of intracellular activities (Pozzan et al., 1988). In addition, calcium and DAG work together to regulate numerous PKC isoforms (Reyland, 2009; Rosse et al., 2010) extending beyond them (Carrasco and Merida, 2007; Rozengurt, 2011), which goes on to phosphorylate other molecules, leading to altered cellular activity. The discovery of PI3Ks has given birth to a new field in PI signalling from the plasma membrane. These kinases are closely associated with growth factors and oncogenic signalling, and the diversity of their activation mechanisms has been overwhelming. PI3K-mediated signalling pathways are paralleled only by the number of effector proteins that bind and are regulated by PIP3. The list includes serine/threonine and soluble tyrosine kinases, guanine exchange factors and GTPase-activating proteins for a variety of small GTP-binding proteins and scaffolding proteins that organize signalling complexes. There are several processes regulated by PIPs in the plasma membrane that are not covered under the canonical PI signalling umbrella but rather belong to cytoskeleton dynamics or to cancer cell migration/metastasis fields. These are the areas that will be reviewed in some detail in subsequent sections.

Mechanisms of chemotaxis and cell migration

In addition to mammalian cells, the mechanisms of chemotaxis and cell migration have been extensively studied using a model organism, Dictyostelium discoideum. Previous studies in Dictyostelium have established that the chemotaxis involves chemical sensing, intracellular signalling and cytoskeleton rearrangement, and this underlying mechanism is conserved in mammalian neutrophils (Chen et al., 2007; Swaney et al., 2010; Tang et al., 2011a; Huang et al., 2013). In fact, Dictyostelium provides a simple model system in which identical single cells respond to one major chemoattractant. Neutrophils, on the other hand, respond to a multitude of attractants that are generated from a wide variety of sources, including bacterially derived formylated peptides (fMLP), products of the complement cascade (C5a), relay signals released by neutrophils (IL-8 and LTB4) and a plethora of chemokines derived from host cells, such as platelet-activating factor (Van Haastert and Veltman, 2007; Insall, 2010; Swaney et al., 2010; Yamauchi et al., 2014). For comparison between neutrophil and Dictyostelium chemotaxis, see Stephens et al. (2008), Iglesias (2009) and Hecht et al. (2011). Dictyostelium and neutrophils precisely detect and respond to very shallow chemoattractant gradients by amplifying very small receptor occupancy differences into highly polarized intracellular events that give rise to a dramatic redistribution of cytoskeletal components. F-actin is locally polymerized at the front and actomyosin is localized at the back of the cells (Kamimura et al., 2009; Renkawitz et al., 2009). This asymmetric enrichment of cytoskeletal components leads to cellular polarity, a prerequisite for migration. The exposure of Dictyostelium cells and neutrophils to gradients of chemoattractants induces a rapid change in polarity through the extension of anterior pseudopods. Pseudopod extension occurs through increased F-actin polymerization and is mediated by the Arp2/3 complex, a seven subunit complex that binds to the sides of pre-existing actin filaments and induces the formation of branched polymers (Bagorda et al., 2006; Suraneni et al., 2012). It has been demonstrated that Rho family GTPases, including Rac, Cdc42 and Rho are responsible for mediating leading edge formation, stimulating F-actin assembly at the front of chemotaxing cells (Srinivasan et al., 2003; Park et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2013). In neutrophils, Cdc42 is proposed to be required exclusively for directional migration and for maintaining leading edge stability in chemoattractant gradients (Srinivasan et al., 2003). Interestingly, no Cdc42 homologues are found in Dictyostelium cells, suggesting that alternative mechanisms should exist to stabilize the leading edge during directional migration. The polarization of chemotaxing cells is not raised from the asymmetric distribution of the receptors themselves. Indeed, studies in both Dictyostelium and neutrophils have established that chemoattractant receptors are uniformly distributed on the surface of chemotaxing cells (Xiao et al., 1997; Servant et al., 1999). However, in some cases, the receptors redistribute to the leading edge, such as CXCR4, in hematopoietic progenitor cells (van Buul et al., 2003), and CCR5, in motile Jurkat cells (Gomez-Mouton et al., 2004). These results suggest that the mechanisms regulating chemotactic responsiveness may vary among different cell types and different receptors.

PI3K and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) regulate chemotaxis

The agonist-induced activation of mammalian chemokine receptors promotes the release of Gβγ, which is responsible for the activation of PLCβ2 and PI3Kγ. Gene knockout studies in mice indicate that PI3Kγ plays an important role in the activation of downstream phagocyte function, including chemotaxis and oxygen radical formation (Hirsch et al., 2000; Vadas et al., 2013). In addition, Ca2+ signals also contribute to chemotaxis as cyclic ADP-ribose-induced Ca2+ mobilizations (Partida-Sanchez et al., 2001; 2007,).

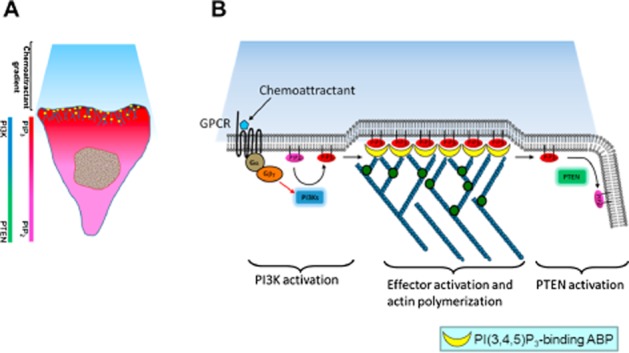

PTEN was first identified as a tumour suppressor gene after mapping its homozygous deletions in several advanced human cancers on chromosome 10 (Li and Sun, 1997; Li et al., 1997; Steck et al., 1997). PTEN is believed to be a dual-function protein phosphatase (Myers et al., 1997). However, subsequent studies revealed that this enzyme shows much higher activity against PI(3,4,5)P3 than against protein and peptide substrates (Maehama and Dixon, 1998; 1999,). Although able to dephosphorylate PI(4,5)P2, PTEN is much more active in converting PI(3,4,5)P3 to PI(4,5)P2 (McConnachie et al., 2003), and the tumour suppressive function of PTEN is primarily associated with its lipid phosphatase activity. Previous studies have shown that the lipid phosphatase activity of PTEN is necessary to maintain proper migration of cells (Iijima and Devreotes, 2002; Iijima et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2007; Henle et al., 2013). Dictyostelium lacking PTEN exhibit PI(3,4,5)P3 overproduction, hyperactivation of the actin cytoskeleton and failure to restrict pseudopodia extension to the leading edge in a chemoattractant gradient (Funamoto et al., 2002; Iijima and Devreotes, 2002; Iijima et al., 2002; M Tang et al., 2011b). In Dictyostelium, like PI3Ks, PTEN localization is also regulated by cAMP, but in an opposite manner. When Dictyostelium are exposed to a cAMP gradient, PTEN accumulates towards the rear. The interaction of PTEN with the membrane is regulated by its PI(4,5)P2 binding domain and independent of PI(3,4,5)P3. The PIPs binding domain in the N-terminus of PTEN contributes to PI(4,5)P2 binding and membrane localization (Iijima et al., 2004; Nguyen et al., 2013). As the membrane association of PTEN is dependent on PI(4,5)P2, phosphorylation of this lipid by PI3K may decrease the amount of PI(4,5)P2 at the leading edge and therefore binding sites for PTEN (Iijima et al., 2004). It is possible that this decrease in PTEN binding leads to further accumulation of PI(3,4,5)P3 at the leading edge and amplifies its asymmetric distribution (Wang et al., 2011). Thus, reciprocal localization of PI3K and PTEN combined with this potential positive feedback mechanism results in spatial regulation of PI(3,4,5)P3 production, with synthesis occurring at the leading edge and degradation at the rear (Figure 2). In addition to PTEN, SHIP1 was identified as a 5-phosphatase that dephosphorylates PI(3,4,5)P3 to PI(3,4)P2 and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 to Ins(1,3,4)P3 (Damen et al., 1996). In contrast to PTEN, which is located at the trailing edge in both Dictyostelium and mammalian cells, SHIP is distributed evenly within the cytoplasm of mammalian cells. In neutrophils, it is reported that SHIP1 is essential for chemoattractant-mediated neutrophil migration and is believed to be the primary inositol phosphatase responsible for generating a PI(3,4,5)P3 gradient. Biochemical studies of neutrophil lysates show that a large amount of the PI(3,4,5)P3 phosphatase activity is contributed by 5-phosphatases. Disruption of SHIP1 resulted in the accumulation of PH-Akt-GFP (a PI(3,4,5)P3 probe) and F-actin polymerization across the cell membrane. Consequently, these neutrophils are extremely flat and display improper polarization and dramatically slower cell migration (Nishio et al., 2007). In contrast, the genetic disruption of PTEN in neutrophils resulted in only minor defects in cell migration with slightly enhanced responsiveness to chemokines and up-regulation of neutrophil functions (Heit et al., 2008). Therefore, SHIP1 may be an important regulator of PI(3,4,5)P3-mediated neutrophil function. Dictyostelium express four PI5-phosphatases that show homology with the mammalian enzymes but the degree to which PI5-phosphatases contribute to PI(3,4,5)P3 dephosphorylation and their functions remain to be determined (Loovers et al., 2003).

Figure 2.

Functional role of PI3K and PTEN in chemotaxis. (A) Spatial-temporal regulation of PTEN and PI3K induces cell polarization in response to a chemoattractant signal. When cells sense the chemoattractant signal, a signalling pathway yet to be identified promotes the rapid translocation of PI3K to the leading edge facing the higher chemoattractant concentration and the delocalization of PTEN from the leading edge. Therefore, PI(3,4,5)P3 is synthesized from PI(4,5)P2 at the leading edge and prevented from accumulating on the sides and at the back of the cell by PTEN, causing a very steep anterior/posterior PI(3,4,5)P3 gradient. (B) Chemotaxis signal pathway in Dictyostelium and neutrophils. Binding of chemoattractant to G-protein coupled receptors releases the Gα heterodimer from the heterotrimeric Gα proteins. Dissociated Gα proteins stimulate PI(3,4,5)P3 production via PI3K and lead to membrane translocation of PI(3,4,5)P3-binding ABPs, probably the members of myosin I. Finally, there is remodelling of the actin cytoskeleton at the leading edge required for the formation of novel cell protrusions.

Alterations of PIP levels in diseases related to cell migration

There are many more human diseases linked to overproduction of PIPs than to the lack of them as demonstrated by the cancer-causing elevations of PI(3,4,5)P3. Class I PI3K mutations are found at very high rates in human cancers (Samuels et al., 2005; Pang et al., 2009), and the same is true for the loss function of PTEN phosphatase which converts PI(3,4,5)P3 back to PI(4,5)P2 (Li et al., 1997; Cantley and Neel, 1999; Choucair et al., 2012). PI3Ks play a major role in oncogenesis by regulating cell survival and proliferation (Roymans and Slegers, 2001; Pendaries et al., 2003; Yuan and Cantley, 2008), and innumerable studies provide mechanisms on how PI(3,4,5)P3 can help cancer cells to survive and metastasize. The first and most remarkable point is that PI(3,4,5)P3 enhances both proliferation and protects cells from apoptosis. Secondly, PI(3,4,5)P3 activates various guanine nucleotide exchange factor proteins that regulates small GTP-binding proteins such as Rho, Rac, Ras and Cdc42, and hence, can activate all of the processes that are used for metastasis and invasion, such as cell migration and attachment (Senoo and Iijima, 2013) (Figure 3). Although activation of PI3K per se is sufficient to transform cells and generate tumours in mouse models (Kang et al., 2006; Gustin et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2010), often these cancers come up with other mutations which promote tumourigenesis. Hence, activation of PI3K may play a role in representing a sensitized state which can facilitate other oncogenic events to initiate the transformation processes (Yuan and Cantley, 2008). PTEN is one of the most commonly lost tumour suppressors in human cancers. Up to 70% of men with prostate cancer are estimated to have lost a copy of the PTEN gene at the time of diagnosis (Chen et al., 2005). During tumour development, mutations and deletions of PTEN occur that inactivate its enzymic activity leading to increased cell proliferation and reduced cell death. Frequent genetic inactivation of PTEN occurs in glioblastoma, endometrial cancer and prostate cancer; and reduced expression is found in many other tumour types such as lung and breast cancer (Bohn et al., 2013; Shukla et al., 2013). Furthermore, PTEN mutation also causes a variety of inherited predispositions to cancer (Wang et al., 2011).

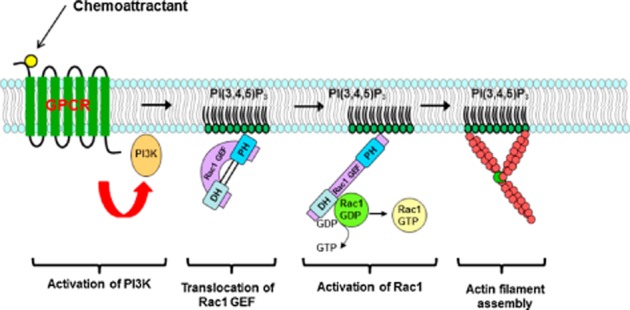

Figure 3.

Activation of actin filament assembly by PI(3,4,5)P3 through Rho GTPase. In neutrophils, Rho family guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) are PI3K effectors, which lead to the accumulation of activated Rac (Rac-GTP). The feedback loop required for the amplification of the pathway may involve actin polymerization.

Functional and pathophysiological roles of actin and PIP-associated ABP

The actin cytoskeleton is a dynamic structure providing physical support and functional flexibility in cell morphology. During cell migration and chemotaxis, the polarized distribution of F-actin is a crucial step in providing the driving force for directional migration in mammalian leukocytes and Dictyostelium cells. In the last decade, accumulating data indicate that establishment of asymmetrical distribution of F-actin in migrating cells is regulated by PI3K and PLC, and these signalling cascades are evolutionarily conserved in all eukaryotic cells (Tang et al., 2011c). The dynamics and organization of these structures in migrating cells are precisely regulated by a large group of actin-associated proteins. Based on the functional role of these proteins, they can be divided into three major groups: (i) a group regulating assembling and depolymerization of F-actin by adding or removing G-actin to the barbed end of actin filaments; (ii) the accessory proteins which control filament bundling and lateral crosslinking; and (iii) a group of phospholipid-binding proteins which attach and tether the actin filament to the plasma membrane.

PIP-binding proteins are involved in F-actin assembly

Gelsolin

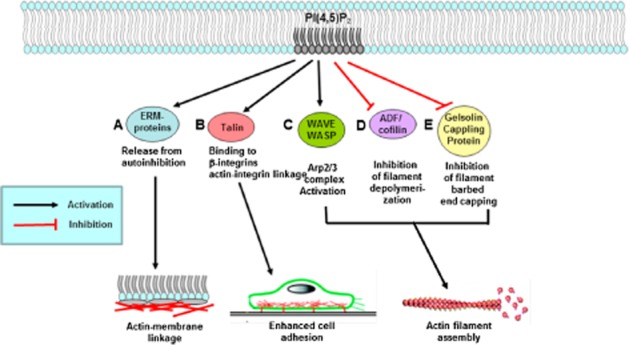

Gelsolin is an 82-kD ABP that is a key regulator of actin filament assembly and disassembly. Gelsolin contains six tightly-folded homologous subdomains (S1–S6) connected by linkers (G1–G6). G1 and G4 bind to actin monomer, G2 is involved in F-actin binding. Gelsolin caps to barbed ends of actin filaments, preventing monomer exchange (end-blocking or capping) (Weeds et al., 1986), promoting nucleation (the assembly of monomers into filaments) and sever existing F-actins. Gelsolin binds PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 in vivo through two regions in G1 and G2 (residue 135–149 and 150–169) which contain clusters of basic residues. Due to overlapping of the PIP-binding site and G-actin/F-actin binding site, PIP binds to S2 and S3, inhibiting gelsolin from actin side binding (Xian and Janmey, 2002). Gelsolin not only binds to charged PIPs but also interacts with fatty acid side chains and thus pulls out phospholipids from lipid bilayers. Therefore, gelsolin may modulate PIP density in the plasma membrane (Feng et al., 2001; Liepina et al., 2003) (Figure 4). Gelsolin is a ubiquitous, multifunctional regulator of cell structure and metabolism. More recent data show that gelsolin can act as a transcriptional cofactor in signal transduction and that its own expression and function can be influenced by epigenetic changes (Mielnicki et al., 1999; Li et al., 2012; Aragona et al., 2013). For example, gelsolin interacts with hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1). HIF-1a is a transcription factor and a key regulator of cell metabolism under hypoxic conditions. Gelsolin and HIF-1a coprecipitate and colocalize in the nuclei during hypoxia. The interaction of gelsolin with HIF-1a in nuclei may play an important role in the induction of apoptosis mediated by HIF-1a-DNase I (Li et al., 2009). The membrane-associated and cytoplasmic forms of gelsolin have their manifold effects on cancer, apoptosis, infection and inflammation, cardiac injury, pulmonary diseases and aging (Ahn et al., 2003; Li et al., 2012).

Figure 4.

Regulation of ABPs by PI(4,5)P2. (A) The activation of ERM proteins is mediated by both exposure to PI(4,5)P2 and phosphorylation of the C-terminal threonine. The C-terminal residue of activated ERM proteins binds to F-actin filaments. (B) Integrins can bind directly to the talin head domain. Through its tail domain, talin can bind directly to actin as well as to other components of the linkage, such as vinculin. (C) PI(4,5)P2 activates WASP and induces WASP dimerization. The Arp2/3 complex mediates actin branch formation activated by WASP dimers on the inside surface of a cell membrane. (D) In the inactive state, cofilin is bound to PI(4,5)P2 at the plasma membrane through its Asp122 residue. Release of cofilin from PI(4,5)P2 at the plasma membrane increases severing of actin filaments, generating free barbed ends that define the sites of dendritic nucleation by the Arp2/3 complex. (E) PI(4,5)P2 sequesters gelsolin and increases actin polymerization.

Cofilin

ADF/cofilin is a family of ABPs which are structurally and functionally related to gelsolin. The protein binds to both G-actin and F-actin and causes depolymerization at the minus end of filaments, thereby preventing their reassembly. Both PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 bind to cofilin and inhibit its activity (Ojala et al., 2001) (Figure 4). The PIP-binding site and F-actin binding site of cofilin are overlapping but are not identical. Based on the site-directed mutagenesis result, the lipid binding sites include basic residues 23–26, 34, 35, 38, 80, 82, 96, 98, 109 and 110. The positions 109 and 110 are required for PIP interaction but not included in the F-actin binding site. Replacement of arginines in 109 and 110 with alanines in yeast results in abnormal actin organization (Ojala et al., 2001). ADF/cofilin-induced actin dynamics are also linked to many diseases. For example, in mammary tumours, the activity status of cofilin is directly related to invasion, intravasation and metastasis (Wang et al., 2007). The level of active cofilin is correlated with metastasis in a mouse model of prostate tumour and in human prostate cancer, cofilin expression is increased significantly in metastatic tumours. A recent study shows that constitutively active cofilin (Ser3Ala) promoted filopodia formation and cell migration mediated by TGF-β, suggesting that the actin severing protein cofilin coordinates responses to TGF-β that are needed for invasive cancer migration and metastasis (Collazo et al., 2014).

Villin

Villin is a 92.5 kDa tissue-specific ABP associated with the actin core bundle of the brush border (Friederich et al., 1999). Villin is structurally related to gelsolin and cofilin, and contains multiple gelsolin-like domains capped by a small (8.5 kDa) ‘headpiece’ at the C-terminus consisting of a fast and independently folding three-helix bundle that is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions. Villin is composed of seven domains, six homologous domains make up the N-terminal core and the remaining domain makes up the C-terminal cap (Bazari et al., 1988). Villin contains three PI(4,5)P2 binding sites, one of which is located at the headpiece and the other two in the core. The PI(4,5)P2 binding sites of villin overlap with its actin-binding sites. Consequently, binding of PI(4,5)P2 to the two NH2-terminal sites inhibits the actin filament severing activity of villin. (Meng et al., 2005).

Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome protein (WASP)

The WASP is a 502-amino acid protein that is expressed in cells of the hematopoietic system. In the inactive state, WASP exists in an auto-inhibited conformation with sequences near its C-terminus binding to a region near its N-terminus. Its activation is dependent upon Cdc42 and PI(4,5)P2 acting to disrupt this interaction causing the WASP protein to ‘open’ (Figure 4). This exposes a domain near the WASP C-Terminus that binds to and activates the Arp2/3 complex. Activated Arp2/3 nucleates new F-actin. WASP is the founding member of a gene family which also includes the broadly expressed neuronal-WASP (N-WASP) and Scar.

The Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome (WAS) family of proteins shares similar domain structure and is involved in transduction of signals from receptors on the cell surface to the actin cytoskeleton. The presence of a number of different motifs suggests that they are regulated by a number of different stimuli and that they interact with multiple proteins. Recent studies have demonstrated that these proteins, directly or indirectly, associate with the small GTPase Cdc42, known to regulate formation of actin filaments, and the cytoskeletal organizing complex, Arp2/3 (Kumar et al., 2012). The WAS gene product is a cytoplasmic protein, expressed exclusively in hematopoietic cells, which shows signalling and cytoskeletal abnormalities in WAS patients. A transcript variant arising as a result of alternative promoter usage, and containing a different 5′ UTR sequence, has been described; however, its full-length nature is not known. The WASP family includes both WASP, which is expressed exclusively in hematopoietic cells, and N-WASP, which is expressed ubiquitously. In its inactive state, N-WASP is auto-inhibited and bound to Arp2/3 (Prehoda et al., 2000). Cooperative binding of Cdc42 and PI(4,5)P2 relieve the auto-inhibition of N-WASP, causing Arp2/3 to carry out actin polymerization (Wegner et al., 2008; Humphries et al., 2014).

In the absence of Cdc42 and PI(4,5)P2, N-WASP is in an inactive, locked conformation. Cooperative binding of both Cdc42 and PI(4,5)P2 relieve the auto-inhibition. The cooperative binding of Cdc42 and PI(4,5)P2 is thermodynamically favoured; binding of one enhances binding of the other (Prehoda et al., 2000; Wegner et al., 2008; Humphries et al., 2014). Cdc42 and PI(4,5)P2 localize the N-WASP-Arp2/3 complex to the plasma membrane. This localization ensures that the actin polymers will be able to push through the plasma membrane and form the filopodium required for cell motility.

WAS, first described in 1954, is a rare X-linked recessive disease characterized by eczema, thrombocytopenia (low platelet count), immune deficiency and bloody diarrhoea (secondary to the thrombocytopenia) (Aldrich et al., 1954). A large number of missense point mutations in WASP have been identified in patients with different degrees of severity such as WAS, X-linked thrombocytopenia and X-linked neutropenia. However, the links between mutations and disease severity have not been characterized (Jin et al., 2004). The majority of the missense mutations in WASP are located in the WH1 domain of WASP, the region important for interaction with WASP interacting protein (Imai et al., 2003). Some of the missense mutations in the WH1 domain of WASP have been shown to affect WASP–WASP interacting protein interaction (Jin et al., 2004).

PIP-binding proteins involved in actin crosslinking

α-actinin

α-Actinin belongs to the spectrin gene superfamily which connects actin filaments to integrins and serves as a scaffold to integrate signalling components at adhesion sites and bundles actin filaments (MacArthur and North, 2004; Otey and Carpen, 2004). Four isoforms of α-actinin include the ‘muscle’ α-actinin-2 and α-actinin-3 and the ‘non-muscle’ α-actinin-1 and α-actinin-4. α-actinin-2 and -3 form part of the contractile machinery by anchoring actin filaments at the Z lines in striated muscles and dense bodies in smooth muscle cells (Otey and Carpen, 2004). The expression of genes encoding ‘non-muscle’ α-actinin-1 and -4 is widespread (Oikonomou et al., 2011). α-actinin-2 is not only present in the muscle but also in the brain especially the gray matter. α-actinin-3 is exclusively present in the skeletal muscle and at very low levels in the brain (Niggli, 2006). In the non-muscle α-actinin especially, α-actinin-4 isoform has been implicated in cancer cell progression and metastasis, as well as the migration of cell types participating in the immune response (Menez et al., 2004; Oikonomou et al., 2011). The PIP-binding site is located in the calponin homology domain (CH1 and CH2), close to the actin binding site. α-actinin binds to both PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 with equal affinity. In vivo study shows that PI(3,4,5)P3 disrupts the connection between α-actinin and F-actin which is opposite to the results from in vitro studies. Moreover, elevation of PI(3,4,5)P3 appears to disrupt the link between actin and integrins, which allows redistributing of focal adhesion in migrating cells (Fraley et al., 2005). Alpha-actinins are known for their ability to modulate cytoskeletal organization and cell motility by crosslinking actin filaments. Increased α-actinin-4 levels in bladder cancer cells exhibit increased growth and invasion activity. In addition, α-actinin-4 knockdown inhibited invasion of bladder cancer cells, but did not alter their growth (Koizumi et al., 2010). In breast cancer cells, α-actinin-4 harbours a functional LXXLL receptor interaction motif, interacts with nuclear receptors in vitro and in mammalian cells, and potently activates transcription mediated by nuclear receptors (Yamamoto et al., 2012).

PIP-binding proteins involved in F-actin-plasma membrane linkage

Dynamin

Dynamin is a GTPase, which is primarily responsible for both clathrin and caveolae-related endocytosis in eukaryotic cells (Herskovits et al., 1993; Taylor et al., 2011; Ferguson and De Camilli, 2012). During endocytosis, dynamin is polymerized around the neck of an endocytic bud (or a tubular membrane structure in vitro) and its GTP hydrolysis-dependent structural reorganization triggers constriction or stretching to promote cleavage of the vesicle from the parent membrane (Praefcke and McMahon, 2004). Dynamin regulates actin polymerization by interacting with cortactin and profilin and has been implicated in coordinating membrane remodelling and actin reorganization (Schafer, 2004). The PH domain of dynamin binds to acidic phospholipid, particularly interacting with PI(4,5)P2. Thus, PH domain mutants exert dominant-negative effects on clathrin-mediated endocytosis (Lee et al., 1999; Vallis et al., 1999). A hydrophobic loop emerging from the PH domain may promote membrane interactions and may also have curvature-generating or curvature-sensing properties (Ramachandran et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2011; Ferguson and De Camilli, 2012). Mutations within the PH and stalk domain of dynamin 2 have been identified in patients with two autosomal-dominant genetic disorders, centronuclear myopathy (Bitoun et al., 2005) and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (Zuchner et al., 2005). Interestingly, the most recent studies suggest that, although dynamin 2 is a key mechanoenzyme, its reduction is beneficial for centronuclear myopathy and thus represents a potential therapeutic approach (Cowling et al., 2014).

Talin

Talin is a cytoskeletal protein concentrated at the region of cell-substratum contact (Burridge and Connell, 1983) and, in lymphocytes, at cell-cell contacts (Burn et al., 1988). Talin is a ubiquitous cytosolic protein which is concentrated in focal adhesions and is thought to be engaged in multiple protein interactions at the cytoplasmic face of cell-substratum contacts. Talin consists of a large C-terminal rod domain that contains bundles of alpha helices and an N-terminal FERM domain with three subdomains: F1, F2 and F3 (Rees et al., 1990). The F3 subdomain of the FERM domain contains the highest affinity integrin-binding site for integrin β tails and is sufficient to activate integrins (Calderwood et al., 2002). Talin interactions with PI(4,5)P2 in vitro and lipid binding induce a conformational change in talin and enhance its interaction with integrins (Martel et al., 2001) (Figure 4). Talin is a focal adhesion component that is recruited early and with structural and functional significance in mediating interactions with integrin cytoplasmic tails which lead to destabilization of the transmembrane complex and resulting in rearrangements in the extracellular integrin compartments that mediate integrin activation. Talin expression is significantly increased in prostate cancer compared with benign and normal prostate tissue and this overexpression correlates with progression to metastatic disease implicating a prognostic value for talin during tumour progression (Sakamoto et al., 2010; Jevnikar et al., 2013).

Vinculin

Vinculin is a 117-kDa cytoskeleton protein which is a highly conserved scaffold protein localized to focal adhesion and adherens junctions (Parsons et al., 2010). Due to its important role in regulation of adhesive force and cell movement, vinculin is one of the most studied cytoskeletal proteins in cellular adhesion. At the site of adhesion, vinculin mediates the recruitment of a number of binding partners such as talin (Johnson and Craig, 1994), α-catenin (Weiss et al., 1998), α-actinin (Kroemker et al., 1994), ponsin/CAP (Mandai et al., 1999), vinexin α/β (Kioka et al., 1999), Arp2/3 (DeMali et al., 2002), paxillin (Wood et al., 1994), PI(4,5)P2 (Johnson et al., 1998) and F-actin (Huttelmaier et al., 1997). Vinculin is a conserved and abundant cytoskeletal protein involved in linking the actin cytoskeleton to the membrane at the sites of adhesion. Therefore, vinculin plays an important role in processes such as cell migration, development and wound healing. Partial loss of vinculin function has been associated with cancer, cardiovascular diseases and lethal defects in embryogenesis (Zemljic-Harpf et al., 2009; Ruiz et al., 2011; Sun and Liu, 2013). Vinculin knockout mice died by the E10.5 stage of the embryo (Xu et al., 1998) and the fibroblasts isolated from these knockout mice have a number of defects including increased cell migration, reduction in cell stiffness and elevated paxillin and focal adhesion kinase signalling (Coll et al., 1995; Subauste et al., 2004).

Ezrin/radixin/moesin (ERM)

The ERM protein family consists of three closely related proteins: ezrin, radixin and moesin. They provide a regulated linkage between the plasma membrane and the underlying actin cytoskeleton (Tsukita et al., 1997). ERM proteins contain three domains: (i) N-terminal domain, also called the FERM domain (Band 4.1, ezrin, radixin, moesin); (ii) extended α-helical domain; and (iii) C-terminal domain which refer to F-actin binding domain. Intermolecular interaction between the N-terminal domain and C-terminal domain called N-/C-ERMAD (ERM associated domain) inhibits ERM protein biological activities. Many studies have indicated that the binding of the FERM domain to PI(4,5)P2 and phosphorylation of a threonine residue in the F-actin binding site cause the dissociation of the N-/C-ERMAD interaction. These results suggest that PI(4,5)P2 binding and phosphorylation of F-actin binding site activate ERM proteins (Figure 4). ERM proteins are involved in cell migration following stimulation of various growth factors. Upon hepatocyte growth factor stimulation of epithelial cells, ezrin is rapidly recruited to the lateral membrane and to the leading edge of migrating cells where it is supposed to play a role in controlling actin polymerization (Crepaldi et al., 1997; Naba et al., 2008). ERM proteins are also involved in tumour invasion and metastasis. An increase of ezrin expression in metastatic human carcinomas from different origins has been observed by immunohistochemical staining and proteomic profiling analyses (Cui et al., 2009; Kahsai et al., 2010). These studies and others indicate that not only the expression level of ERM proteins but also their phosphorylation status and subcellular localization should be considered to understand their role in tumour progression (Arpin et al., 2011). Pancreatic cancers with lymph node metastasis have shown an increased expression of moesin and radixin but not in the lymph node metastasis-negative group. Another example of change in ezrin localization associated with a poor prognosis is provided by invasive breast carcinomas (Sarrio et al., 2006).

Septin

Septins are a group of highly conserved GTP-binding proteins that assemble into filaments and constitute an emerging of the fourth component of cytoskeleton (Mostowy and Cossart, 2012). Septin proteins contain three domains: a conserved GTP-binding domain, a N-terminal proline-rich domain and C-terminal coiled coil domains that vary between family members. The septins act as a scaffold, recruiting many proteins. These protein complexes are involved in cytokinesis, cell polarity, in the morphogenesis checkpoint, spindle alignment checkpoint and bud site selection. Septins localize to a small structure in the middle section of spermatozoa called the annulus and are required for the structural integrity of that region. Spermatozoa lacking SEPT4 become fragile through their middle piece and bend sharply or break as they develop and become motile. In another motile cell, septin filaments assemble along the cortex of amoeboid T-cells in a collar-like distribution that bridges the region between the cell body and the trailing uropod. ShRNA knockdown of septin complexes in T-cells cause increases in cortical protrusions and blebbing, elongation of the uropod and the loss of persistent motility (Gilden and Krummel, 2010). In vitro studies have shown that purified septins bind lipids with particular affinities for PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 (Zhang et al., 1999; Tanaka-Takiguchi et al., 2009) which they bind through a polybasic region just N-terminal to GTP-binding domain (Gilden and Krummel, 2010). Addition of septins to PIP-containing liposome changed large spherical liposome into tubular structures, with properties distinct from those formed by BAR domain-containing proteins. In vivo, depletion of PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 disrupts septin filament in 3T3 cells (Gilden and Krummel, 2010).

Myosin isoforms

Myosin I is a monomeric, actin-based motor protein with ATPase activity and has been shown to function in membrane–cytoskeletal interactions, including vesicle transport along actin filaments and regulation of plasma membrane tension. Myosin I molecules have a tail homology (TH) domain that contains a putative PH domain, a PI binding motif. Previous studies have shown that the TH domain preferentially binds to acidic phospholipids such as phosphatidylserine and PI(4,5)P2. These phospholipids are relatively abundant in biological membranes and may not change their levels in response to intracellular signalling. In contrast, PI(3,4,5)P3 levels are highly regulated and function as signalling mechanisms. Our previous studies have shown that Dictyostelium myosin ID, IE and IF interact with PI(3,4,5)P3 in vitro and in vivo, which suggest that these myosin molecules are regulated by PI(3,4,5)P3 (Chen et al., 2012). Furthermore, human myosin IF, which has been suggested to bind to PI(3,4,5)P3 in a proteomic study, also binds to PI(3,4,5)P3 in a lipid dot-blot assay, and mutations in the TH domain of human myosin IF blocked its interaction with PI(3,4,5)P3. These data indicate that the ability of TH domain-containing myosin I to bind to PI(3,4,5)P3 is evolutionarily conserved (Chen and Iijima, 2012; Chen et al., 2012). Previous studies have shown that myosin IF, on chromosome band 19p13.2–p13.3, is a fusion partner of the MLL gene, in de novo infant acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) with chromosomal abnormalities involving chromosomes 7, 11, 19 and 22. Myosin IF, the fourth partner gene of MLL on chromosome band 19p13.t(11;19)(q23;p13) is a recurring chromosomal translocation frequently observed in both acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and AML. The MLL-MYO1F fusion protein contains almost the entire MYO1F protein. Functional analyses of various MLL fusion proteins demonstrated two different mechanisms for leukemogenesis by MLL fusion proteins: (i) the fusion partners have transcriptional activation domains and (ii) induction of dimerization of MLL fusion proteins. MYO1F has neither a transcriptional transactivation domain nor a dimerization domain. The mechanism of MLL-MYO1F-induced leukemia remains unclear (Taki et al., 2005).

Concluding remarks

No review article is able to cover all of what has been learned about PIPs over the last few decades. It is generally recognized that these lipids are fundamental in the regulation of all aspects of membrane dynamics in eukaryotic cells. What remains to be fully determined are the overall underlying principles of how these lipids work and why we encounter them wherever we look in biomedical research. In the past few decades, remarkable progress has been made in identifying the functional roles of PIPs. However, there are still several questions that need to be answered. How do PIPs and its partner proteins regulate changes in cytoskeleton–membrane interaction to promote the assembly/disassembly of cell junctions or cell motility? How do they participate in the transmission of signals that control adhesion-dependent processes such as cell proliferation and cell survival? And how PIPs organize multiple protein complexes in specific compartments in response to external signals? The efforts required for answering these questions must be tightly linked with methodological advances. Conditional knockout experiments will provide a better comprehension of the role of PIPs and its binding proteins in a variety of tissues. Advances in mass spectrometry technologies offer the potential of studying hierarchies of protein binding to PIPs in cellular systems. Advanced imaging techniques, including image correlation analysis, analysis of protein dynamics and high resolution imaging and FRET, should help us map PIPs localization and interactions in space and time. All these techniques, together with bioinformatics and mathematical modelling could bring us closer to solving how PIPs orchestrate cytoskeletal systems.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Science Council of Taiwan (101-2320-B-110-003 and 102-2320-B-110-007), Center for Stem Cell Research, Kaohsiung Medical University (KMU-TP103G01, KMU-TP103G02, KMU-TP103G03) and NSYSU-KMU Joint Research Project (NSYSUKMU 2013-I006).

Glossary

- ABP

actin-binding protein

- IP3

inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate

- PIP

phosphoinositide

- PI(3,4,5)P3

phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate

- PI(4,5)P2

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog

- WASP

Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome Protein

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahn JS, Jang IS, Kim DI, Cho KA, Park YH, Kim K, et al. Aging-associated increase of gelsolin for apoptosis resistance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;312:1335–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich RA, Steinberg AG, Campbell DC. Pedigree demonstrating a sex-linked recessive condition characterized by draining ears, eczematoid dermatitis and bloody diarrhea. Pediatrics. 1954;13:133–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol. 2013a;170:1797–1867. doi: 10.1111/bph.12451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: G Protein-Coupled Receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2013b;170:1459–1581. doi: 10.1111/bph.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Catterall WA, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Ligand-Gated Ion Channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2013c;170:1582–1606. doi: 10.1111/bph.12446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang J, Lijovic M, Ashman LK, Kan K, Frauman AG. CD151 protein expression predicts the clinical outcome of low-grade primary prostate cancer better than histologic grading: a new prognostic indicator? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(11 Pt 1):1717–1721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang J, Fang BL, Ashman LK, Frauman AG. The migration and invasion of human prostate cancer cell lines involves CD151 expression. Oncol Rep. 2010;24:1593–1597. doi: 10.3892/or_00001022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragona M, Panciera T, Manfrin A, Giulitti S, Michielin F, Elvassore N, et al. A mechanical checkpoint controls multicellular growth through YAP/TAZ regulation by actin-processing factors. Cell. 2013;154:1047–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpin M, Chirivino D, Naba A, Zwaenepoel I. Emerging role for ERM proteins in cell adhesion and migration. Cell Adh Migr. 2011;5:199–206. doi: 10.4161/cam.5.2.15081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagorda A, Mihaylov VA, Parent CA. Chemotaxis: moving forward and holding on to the past. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95:12–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balla T, Baukal AJ, Guillemette G, Catt KJ. Multiple pathways of inositol polyphosphate metabolism in angiotensin-stimulated adrenal glomerulosa cells. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:4083–4091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazari WL, Matsudaira P, Wallek M, Smeal T, Jakes R, Ahmed Y. Villin sequence and peptide map identify six homologous domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:4986–4990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.4986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ. Inositol trisphosphate and diacylglycerol as second messengers. Biochem J. 1984;220:345–360. doi: 10.1042/bj2200345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Irvine RF. Inositol trisphosphate, a novel second messenger in cellular signal transduction. Nature. 1984;312:315–321. doi: 10.1038/312315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitoun M, Maugenre S, Jeannet PY, Lacene E, Ferrer X, Laforet P, et al. Mutations in dynamin 2 cause dominant centronuclear myopathy. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1207–1209. doi: 10.1038/ng1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchoin L, Boujemaa-Paterski R, Sykes C, Plastino J. Actin dynamics, architecture, and mechanics in cell motility. Physiol Rev. 2014;94:235–263. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn BA, Mina S, Krohn A, Simon R, Kluth M, Harasimowicz S, et al. Altered PTEN function caused by deletion or gene disruption is associated with poor prognosis in rectal but not in colon cancer. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:1524–1533. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burn P, Kupfer A, Singer SJ. Dynamic membrane-cytoskeletal interactions: specific association of integrin and talin arises in vivo after phorbol ester treatment of peripheral blood lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:497–501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.2.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge K, Connell L. A new protein of adhesion plaques and ruffling membranes. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:359–367. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.2.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Buul JD, Voermans C, van Gelderen J, Anthony EC, van der Schoot CE, Hordijk PL. Leukocyte-endothelium interaction promotes SDF-1-dependent polarization of CXCR4. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30302–30310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304764200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood DA, Yan B, de Pereda JM, Alvarez BG, Fujioka Y, Liddington RC, et al. The phosphotyrosine binding-like domain of talin activates integrins. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21749–21758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111996200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantley LC, Neel BG. New insights into tumor suppression: PTEN suppresses tumor formation by restraining the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4240–4245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco S, Merida I. Diacylglycerol, when simplicity becomes complex. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CL, Iijima M. Myosin I: a new pip(3) effector in chemotaxis and phagocytosis. Commun Integr Biol. 2012;5:294–296. doi: 10.4161/cib.19892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CL, Wang Y, Sesaki H, Iijima M. Myosin I links PIP3 signaling to remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton in chemotaxis. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra10. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Iijima M, Tang M, Landree MA, Huang YE, Xiong Y, et al. PLA2 and PI3K/PTEN pathways act in parallel to mediate chemotaxis. Dev Cell. 2007;12:603–614. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Trotman LC, Shaffer D, Lin HK, Dotan ZA, Niki M, et al. Crucial role of p53-dependent cellular senescence in suppression of Pten-deficient tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;436:725–730. doi: 10.1038/nature03918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choucair K, Ejdelman J, Brimo F, Aprikian A, Chevalier S, Lapointe J. PTEN genomic deletion predicts prostate cancer recurrence and is associated with low AR expression and transcriptional activity. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:543. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciobanasu C, Faivre B, Le Clainche C. Integrating actin dynamics, mechanotransduction and integrin activation: the multiple functions of actin binding proteins in focal adhesions. Eur J Cell Biol. 2013;92:339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll JL, Ben-Ze'ev A, Ezzell RM, Rodriguez Fernandez JL, Baribault H, Oshima RG, et al. Targeted disruption of vinculin genes in F9 and embryonic stem cells changes cell morphology, adhesion, and locomotion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9161–9165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collazo J, Zhu B, Larkin S, Horbinski C, Pu H, Martin SK, et al. Cofilin drives cell invasive and metastatic responses to TGF-beta in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2362–2373. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowling BS, Chevremont T, Prokic I, Kretz C, Ferry A, Coirault C, et al. Reducing dynamin 2 expression rescues X-linked centronuclear myopathy. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1350–1363. doi: 10.1172/JCI71206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaldi T, Gautreau A, Comoglio PM, Louvard D, Arpin M. Ezrin is an effector of hepatocyte growth factor-mediated migration and morphogenesis in epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:423–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.2.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Wu J, Zong M, Song G, Jia Q, Jiang J, et al. Proteomic profiling in pancreatic cancer with and without lymph node metastasis. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1614–1621. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damen JE, Liu L, Rosten P, Humphries RK, Jefferson AB, Majerus PW, et al. The 145-kDa protein induced to associate with Shc by multiple cytokines is an inositol tetraphosphate and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate 5-phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1689–1693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMali KA, Barlow CA, Burridge K. Recruitment of the Arp2/3 complex to vinculin: coupling membrane protrusion to matrix adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:881–891. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200206043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty GJ, McMahon HT. Mediation, modulation, and consequences of membrane-cytoskeleton interactions. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:65–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L, Mejillano M, Yin HL, Chen J, Prestwich GD. Full-contact domain labeling: identification of a novel phosphoinositide binding site on gelsolin that requires the complete protein. Biochemistry. 2001;40:904–913. doi: 10.1021/bi000996q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SM, De Camilli P. Dynamin, a membrane-remodelling GTPase. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:75–88. doi: 10.1038/nrm3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley TS, Pereira CB, Tran TC, Singleton C, Greenwood JA. Phosphoinositide binding regulates alpha-actinin dynamics: mechanism for modulating cytoskeletal remodeling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15479–15482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500631200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friederich E, Vancompernolle K, Louvard D, Vandekerckhove J. Villin function in the organization of the actin cytoskeleton. Correlation of in vivo effects to its biochemical activities in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26751–26760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funamoto S, Meili R, Lee S, Parry L, Firtel RA. Spatial and temporal regulation of 3-phosphoinositides by PI 3-kinase and PTEN mediates chemotaxis. Cell. 2002;109:611–623. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00755-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilden J, Krummel MF. Control of cortical rigidity by the cytoskeleton: emerging roles for septins. Cytoskeleton. 2010;67:477–486. doi: 10.1002/cm.20461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Mouton C, Lacalle RA, Mira E, Jimenez-Baranda S, Barber DF, Carrera AC, et al. Dynamic redistribution of raft domains as an organizing platform for signaling during cell chemotaxis. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:759–768. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustin JP, Karakas B, Weiss MB, Abukhdeir AM, Lauring J, Garay JP, et al. Knockin of mutant PIK3CA activates multiple oncogenic pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2835–2840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813351106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht I, Skoge ML, Charest PG, Ben-Jacob E, Firtel RA, Loomis WF, et al. Activated membrane patches guide chemotactic cell motility. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heit B, Robbins SM, Downey CM, Guan Z, Colarusso P, Miller BJ, et al. PTEN functions to ‘prioritize’ chemotactic cues and prevent ‘distraction’ in migrating neutrophils. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:743–752. doi: 10.1038/ni.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henle SJ, Carlstrom LP, Cheever TR, Henley JR. Differential role of PTEN phosphatase in chemotactic growth cone guidance. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:20837–20842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C113.487066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskovits JS, Burgess CC, Obar RA, Vallee RB. Effects of mutant rat dynamin on endocytosis. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:565–578. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.3.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hespel C, Moser M. Role of inflammatory dendritic cells in innate and adaptive immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:2535–2543. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch E, Katanaev VL, Garlanda C, Azzolino O, Pirola L, Silengo L, et al. Central role for G protein-coupled phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma in inflammation. Science. 2000;287:1049–1053. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CH, Tang M, Shi C, Iglesias PA, Devreotes PN. An excitable signal integrator couples to an idling cytoskeletal oscillator to drive cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:1307–1316. doi: 10.1038/ncb2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries AC, Donnelly SK, Way M. Cdc42 and the Rho GEF intersectin-1 collaborate with Nck to promote N-WASP-dependent actin polymerisation. J Cell Sci. 2014;127(Pt 3):673–685. doi: 10.1242/jcs.141366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttelmaier S, Bubeck P, Rudiger M, Jockusch BM. Characterization of two F-actin-binding and oligomerization sites in the cell-contact protein vinculin. Eur J Biochem. 1997;247:1136–1142. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.01136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias PA. Spatial regulation of PI3K signaling during chemotaxis. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2009;1:247–253. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima M, Devreotes P. Tumor suppressor PTEN mediates sensing of chemoattractant gradients. Cell. 2002;109:599–610. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00745-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima M, Huang YE, Devreotes P. Temporal and spatial regulation of chemotaxis. Dev Cell. 2002;3:469–478. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima M, Huang YE, Luo HR, Vazquez F, Devreotes PN. Novel mechanism of PTEN regulation by its phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate binding motif is critical for chemotaxis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16606–16613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K, Nonoyama S, Ochs HD. WASP (Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein) gene mutations and phenotype. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;3:427–436. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200312000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insall RH. Understanding eukaryotic chemotaxis: a pseudopod-centred view. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:453–458. doi: 10.1038/nrm2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isozaki T, Arbab AS, Haas CS, Amin MA, Arendt MD, Koch AE, et al. Evidence that CXCL16 is a potent mediator of angiogenesis and is involved in endothelial progenitor cell chemotaxis: studies in mice with K/BxN serum-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1736–1746. doi: 10.1002/art.37981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janmey PA, Lindberg U. Cytoskeletal regulation: rich in lipids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:658–666. doi: 10.1038/nrm1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jevnikar Z, Rojnik M, Jamnik P, Doljak B, Fonovic UP, Kos J. Cathepsin H mediates the processing of talin and regulates migration of prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:2201–2209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.436394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin T. Gradient sensing during chemotaxis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25:532–537. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Mazza C, Christie JR, Giliani S, Fiorini M, Mella P, et al. Mutations of the Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome Protein (WASP): hotspots, effect on transcription, and translation and phenotype/genotype correlation. Blood. 2004;104:4010–4019. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RP, Craig SW. An intramolecular association between the head and tail domains of vinculin modulates talin binding. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12611–12619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RP, Niggli V, Durrer P, Craig SW. A conserved motif in the tail domain of vinculin mediates association with and insertion into acidic phospholipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10211–10222. doi: 10.1021/bi9727242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahsai AW, Zhu S, Fenteany G. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 activates radixin, regulating membrane protrusion and motility in epithelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803:300–310. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura Y, Tang M, Devreotes P. Assays for chemotaxis and chemoattractant-stimulated TorC2 activation and PKB substrate phosphorylation in Dictyostelium. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;571:255–270. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-198-1_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Denley A, Vanhaesebroeck B, Vogt PK. Oncogenic transformation induced by the p110beta, -gamma, and -delta isoforms of class I phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1289–1294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510772103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kioka N, Sakata S, Kawauchi T, Amachi T, Akiyama SK, Okazaki K, et al. Vinexin: a novel vinculin-binding protein with multiple SH3 domains enhances actin cytoskeletal organization. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:59–69. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi T, Nakatsuji H, Fukawa T, Avirmed S, Fukumori T, Takahashi M, et al. The role of actinin-4 in bladder cancer invasion. Urology. 2010;75:357–364. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemker M, Rudiger AH, Jockusch BM, Rudiger M. Intramolecular interactions in vinculin control alpha-actinin binding to the vinculin head. FEBS Lett. 1994;355:259–262. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Xu J, Perkins C, Guo F, Snapper S, Finkelman FD, et al. Cdc42 regulates neutrophil migration via crosstalk between WASp, CD11b, and microtubules. Blood. 2012;120:3563–3574. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-426981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A, Frank DW, Marks MS, Lemmon MA. Dominant-negative inhibition of receptor-mediated endocytosis by a dynamin-1 mutant with a defective pleckstrin homology domain. Curr Biol. 1999;9:261–264. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Kim YR, Park J, Kim S. Inositol polyphosphate multikinase signaling in the regulation of metabolism. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1271:68–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Poulogiannis G, Pyne S, Jia S, Zou L, Signoretti S, et al. A constitutively activated form of the p110beta isoform of PI3-kinase induces prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11002–11007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005642107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon MA, Ferguson KM. Signal-dependent membrane targeting by pleckstrin homology (PH) domains. Biochem J. 2000;350(Pt 1):1–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DM, Sun H. TEP1, encoded by a candidate tumor suppressor locus, is a novel protein tyrosine phosphatase regulated by transforming growth factor beta. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2124–2129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GH, Shi Y, Chen Y, Sun M, Sader S, Maekawa Y, et al. Gelsolin regulates cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction through DNase I-mediated apoptosis. Circ Res. 2009;104:896–904. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.172882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GH, Arora PD, Chen Y, McCulloch CA, Liu P. Multifunctional roles of gelsolin in health and diseases. Med Res Rev. 2012;32:999–1025. doi: 10.1002/med.20231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Yen C, Liaw D, Podsypanina K, Bose S, Wang SI, et al. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275:1943–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liepina I, Czaplewski C, Janmey P, Liwo A. Molecular dynamics study of a gelsolin-derived peptide binding to a lipid bilayer containing phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Biopolymers. 2003;71:49–70. doi: 10.1002/bip.10375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YW, Neumann S, Ramachandran R, Ferguson SM, Pucadyil TJ, Schmid SL. Differential curvature sensing and generating activities of dynamin isoforms provide opportunities for tissue-specific regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E234–E242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102710108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loovers HM, Veenstra K, Snippe H, Pesesse X, Erneux C, van Haastert PJ. A diverse family of inositol 5-phosphatases playing a role in growth and development in Dictyostelium discoideum. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5652–5658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208396200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur DG, North KN. A gene for speed? The evolution and function of alpha-actinin-3. Bioessays. 2004;26:786–795. doi: 10.1002/bies.20061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehama T, Dixon JE. The tumor suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13375–13378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehama T, Dixon JE. PTEN: a tumour suppressor that functions as a phospholipid phosphatase. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:125–128. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandai K, Nakanishi H, Satoh A, Takahashi K, Satoh K, Nishioka H, et al. Ponsin/SH3P12: an l-afadin- and vinculin-binding protein localized at cell-cell and cell-matrix adherens junctions. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:1001–1017. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.5.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel V, Racaud-Sultan C, Dupe S, Marie C, Paulhe F, Galmiche A, et al. Conformation, localization, and integrin binding of talin depend on its interaction with phosphoinositides. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21217–21227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102373200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins M, Warren S, Kimberley C, Margineanu A, Peschard P, McCarthy A, et al. Activity of PLCepsilon contributes to chemotaxis of fibroblasts towards PDGF. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(Pt 23):5758–5769. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnachie G, Pass I, Walker SM, Downes CP. Interfacial kinetic analysis of the tumour suppressor phosphatase, PTEN: evidence for activation by anionic phospholipids. Biochem J. 2003;371(Pt 3):947–955. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLennan R, Dyson L, Prather KW, Morrison JA, Baker RE, Maini PK, et al. Multiscale mechanisms of cell migration during development: theory and experiment. Development. 2012;139:2935–2944. doi: 10.1242/dev.081471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menez J, Le Maux Chansac B, Dorothee G, Vergnon I, Jalil A, Carlier MF, et al. Mutant alpha-actinin-4 promotes tumorigenicity and regulates cell motility of a human lung carcinoma. Oncogene. 2004;23:2630–2639. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng J, Vardar D, Wang Y, Guo HC, Head JF, McKnight CJ. High-resolution crystal structures of villin headpiece and mutants with reduced F-actin binding activity. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11963–11973. doi: 10.1021/bi050850x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielnicki LM, Ying AM, Head KL, Asch HL, Asch BB. Epigenetic regulation of gelsolin expression in human breast cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 1999;249:161–176. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki H, Miura K, Takenawa T. N-WASP, a novel actin-depolymerizing protein, regulates the cortical cytoskeletal rearrangement in a PIP2-dependent manner downstream of tyrosine kinases. EMBO J. 1996;15:5326–5335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostowy S, Cossart P. Septins: the fourth component of the cytoskeleton. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:183–194. doi: 10.1038/nrm3284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers MP, Stolarov JP, Eng C, Li J, Wang SI, Wigler MH, et al. PTEN, the tumor suppressor from human chromosome 10q23, is a dual-specificity phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9052–9057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naba A, Reverdy C, Louvard D, Arpin M. Spatial recruitment and activation of the Fes kinase by ezrin promotes HGF-induced cell scattering. EMBO J. 2008;27:38–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasuhoglu C, Feng S, Mao J, Yamamoto M, Yin HL, Earnest S, et al. Nonradioactive analysis of phosphatidylinositides and other anionic phospholipids by anion-exchange high-performance liquid chromatography with suppressed conductivity detection. Anal Biochem. 2002;301:243–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HN, Afkari Y, Senoo H, Sesaki H, Devreotes PN, Iijima M. Mechanism of human PTEN localization revealed by heterologous expression in Dictyostelium. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.507. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niggli V. Lipid interactions of cytoskeletal proteins. In: Khurana S, editor. Aspects of the Cytoskeleton. San Diego, CA: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 221–250. [Google Scholar]

- Nishio M, Watanabe K, Sasaki J, Taya C, Takasuga S, Iizuka R, et al. Control of cell polarity and motility by the PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 phosphatase SHIP1. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:36–44. doi: 10.1038/ncb1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomou KG, Zachou K, Dalekos GN. Alpha-actinin: a multidisciplinary protein with important role in B-cell driven autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2011;10:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojala PJ, Paavilainen V, Lappalainen P. Identification of yeast cofilin residues specific for actin monomer and PIP2 binding. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15562–15569. doi: 10.1021/bi0117697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke FA, Halenda SP, Zavoico GB, Feinstein MB. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate releases Ca2+ from a Ca2+-transporting membrane vesicle fraction derived from human platelets. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:956–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otey CA, Carpen O. Alpha-actinin revisited: a fresh look at an old player. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2004;58:104–111. doi: 10.1002/cm.20007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang H, Flinn R, Patsialou A, Wyckoff J, Roussos ET, Wu H, et al. Differential enhancement of breast cancer cell motility and metastasis by helical and kinase domain mutations of class IA phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8868–8876. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KC, Rivero F, Meili R, Lee S, Apone F, Firtel RA. Rac regulation of chemotaxis and morphogenesis in Dictyostelium. EMBO J. 2004;23:4177–4189. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Horwitz AR, Schwartz MA. Cell adhesion: integrating cytoskeletal dynamics and cellular tension. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:633–643. doi: 10.1038/nrm2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partida-Sanchez S, Cockayne DA, Monard S, Jacobson EL, Oppenheimer N, Garvy B, et al. Cyclic ADP-ribose production by CD38 regulates intracellular calcium release, extracellular calcium influx and chemotaxis in neutrophils and is required for bacterial clearance in vivo. Nat Med. 2001;7:1209–1216. doi: 10.1038/nm1101-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partida-Sanchez S, Gasser A, Fliegert R, Siebrands CC, Dammermann W, Shi G, et al. Chemotaxis of mouse bone marrow neutrophils and dendritic cells is controlled by adp-ribose, the major product generated by the CD38 enzyme reaction. J Immunol. 2007;179:7827–7839. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, et al. NC-IUPHAR. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert-driven knowledge base of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl Acids Res. 2014;42(Database Issue):D1098-1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendaries C, Tronchere H, Plantavid M, Payrastre B. Phosphoinositide signaling disorders in human diseases. FEBS Lett. 2003;546:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00437-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzan T, Volpe P, Zorzato F, Bravin M, Krause KH, Lew DP, et al. The Ins(1,4,5)P3-sensitive Ca2+ store of non-muscle cells: endoplasmic reticulum or calciosomes? J Exp Biol. 1988;139:181–193. doi: 10.1242/jeb.139.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praefcke GJ, McMahon HT. The dynamin superfamily: universal membrane tubulation and fission molecules? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:133–147. doi: 10.1038/nrm1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prehoda KE, Scott JA, Mullins RD, Lim WA. Integration of multiple signals through cooperative regulation of the N-WASP-Arp2/3 complex. Science. 2000;290:801–806. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5492.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran R, Pucadyil TJ, Liu YW, Acharya S, Leonard M, Lukiyanchuk V, et al. Membrane insertion of the pleckstrin homology domain variable loop 1 is critical for dynamin-catalyzed vesicle scission. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:4630–4639. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-08-0683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees DJ, Ades SE, Singer SJ, Hynes RO. Sequence and domain structure of talin. Nature. 1990;347:685–689. doi: 10.1038/347685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renkawitz J, Schumann K, Weber M, Lammermann T, Pflicke H, Piel M, et al. Adaptive force transmission in amoeboid cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1438–1443. doi: 10.1038/ncb1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyland ME. Protein kinase C isoforms: multi-functional regulators of cell life and death. Front Biosci. 2009;14:2386–2399. doi: 10.2741/3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosse C, Linch M, Kermorgant S, Cameron AJ, Boeckeler K, Parker PJ. PKC and the control of localized signal dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:103–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roymans D, Slegers H. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases in tumor progression. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:487–498. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.01936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozengurt E. Protein kinase D signaling: multiple biological functions in health and disease. Physiology (Bethesda) 2011;26:23–33. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00037.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]