Abstract

Food allergen oral immunotherapy (OIT) is an experimental, immune-modifying therapy that may induce clinical desensitization in some patients. OIT is still in early phase clinical research, but some provider may offer OIT as a clinical service. To understand the current practices of allergists performing OIT an on-line survey was emailed to members of the American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology. Among 442 respondents, 61 (13.8%) reported participating in OIT, including 28 in non-academic settings. Informed consent for OIT was obtained by 91.3%, IRB approval by 47.7% and Investigational New Drug (IND) approval by 38.1%. Compared to non-academic participants, more academic participants used peanut OIT, obtained IRB and IND (p <0.0001 respectively), and challenged patients prior to entry (p=0.008). More non-academic providers billed the patient or insurance for reimbursement (p<0.0001). Low reported regard for the importance for FDA approval or a standardized product (increased odds), and high regard for better safety data (decreased odds) were associated with considering to offer OIT as a service. Significant differences exist in OIT occurring in academic vs. non-academic settings. Further assessment is needed regarding the different motivations and practice styles among providers offering OIT, and those considering doing so.

Keywords: Food oral immunotherapy, food allergy, oral food challenge, provider attitudes, sublingual immunotherapy, clinical trial

Introduction

Food oral immunotherapy (OIT) is an investigational treatment that can modulate the immune response1,2 and has been shown in small trials to induce variable hypo-responsiveness to allergen (e.g., clinical desensitization).3–5 However, the interventions and endpoints used in these and other published trials vary widely, and to date, most study designs either have not included controls or have employed a cross-over design. As a result, neither safety nor efficacy have been definitively established as superior to allergen avoidance, and recent National Institutes of Allergy and Infections Diseases (NIAID) food allergy treatment guidelines specifically recommend against the use of OIT in clinical settings.6 OIT is also not currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration, a convention that some allergists in private practice have contested as unnecessary given the potential benefits of OIT.6–9 The question of equipoise in the practice of OIT continues to be prominently debated, in light of still emerging data pertaining to the safety and efficacy of OIT.7,10–13 There are limited data pertaining to the actual practice of OIT outside of trials conducted at academic medical centers,8,11,14 but it is known that OIT is being offered by allergists, as well as otolaryngologists and non-allergy specialists in several states, with limited differentiation of these services by patients and some exploratory data suggestive that provider framing is a factor in influencing parent participation in OIT programs.15 Additional factors that have been shown to influence participation in OIT at an academic center include parental anxiety and perception of reaction severity.16 However, there are no current data exploring provider-level motivations to participate in OIT, either in an academic or a non-academic setting, provider opinions regarding OIT and the question of equipoise, as well as understand differences that may exist in current practice styles among providers offering OIT. We therefore undertook a study to survey these provider-level attributes among members of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, to better understand current practice styles and sentiment regarding OIT.

Methods

A 23-question survey was developed by the investigational team through the AAAAI Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee Subgroup on Oral and Sublingual Immunotherapy. Membership on the subcommittee was open to any interested committee member. Questions were developed to survey current OIT practice styles (including types of patients, patient age, allergens for which OIT was offered, protocol and oversight, and reimbursement options for OIT), opinions on OIT practice styles and current regulatory climate, barriers to entry to the practice of OIT, awareness of other providers practicing OIT, and demographic information. Once developed, the survey was posted for group feedback on the Basecamp access site for the Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee. Once approved by the subcommittee, the survey was then forwarded to the AAAAI Needs Assessment committee for approval prior to distribution through the AAAAI membership email distribution list in January of 2013 to 4,370 domestic and international members. A reminder email within a 2-week period was sent to members who did not complete the survey within a specified time frame. The survey was offered for 4 weeks. No financial incentive for participation was provided. The questions were administered in a multiple-choice format, with some questions allowing for multiple responses per question, and selected questions allowing for an open ended additional response. Response to every question was not mandated. Responses were automatically tabulated through the Survey Monkey server and exported to a spreadsheet for data cleaning, variable labeling/coding and uploading into a statistical package. Data were collected and analyzed at the provider level for general descriptive trends using frequency analysis, and inferential proportional comparisons were assessed using the two-sided Fisher exact test at a pre-specified alpha level of 0.05 for significance. Logistic regression was used to build an exploratory model of pre-specified factors that may influence provider participation in OIT. Data were analyzed using Stata IC, Version 12 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). This study was deemed exempt from ongoing review by the University of North Carolina School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Results

A total of 442 Allergists responded to the survey (response rate approximately 10.1% of 4370 invitees). Among responding allergists (n=440 to this question), 75.9% identified that they were in a private practice (n=96 in solo practice, n=157 in a single specialty group practice, and n=81 in a multi-specialty group practice), and 24.1% in an academic practice (n=106). Geographically, 18.3% reported practicing in the Northeast, 17.4% in the Mid-Atlantic area, 10.5% in the Southeast, 17.6% in the Southwest, 17.6% in the Upper Midwest, 18.5% in the Far West, and 0.1% from Canada.. Approximately 41.7% indicated that they were aware of either another allergist or other provider (including non-allopathic providers) was offering OIT, and 42.6% that another allergist or provider was offering SLIT to food (an alternative approach to oral tolerance also being researched or offered clinically).

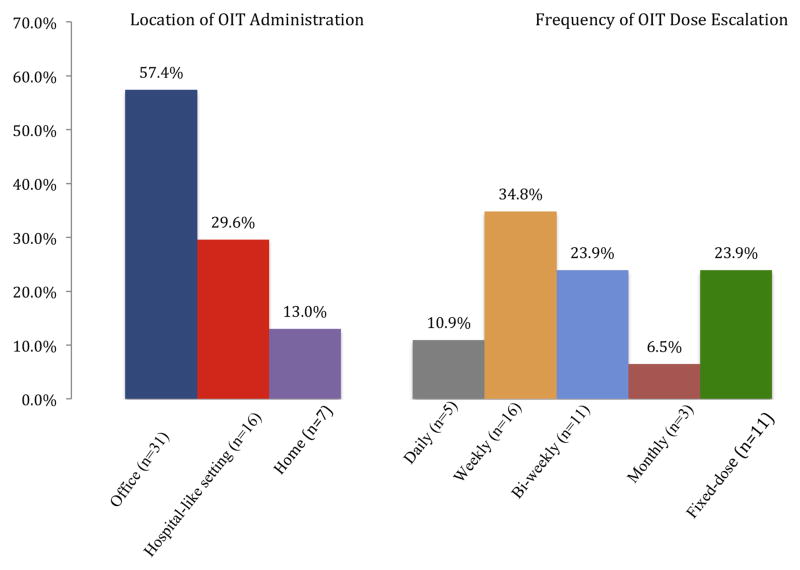

A total of 61 providers (13.8%) indicated that they were providing OIT as a service or studying it under a research protocol. Among the allergists participating in OIT in some capacity, 68.9% (42/61) reported obtaining informed consent prior to initiating OIT (including 88% of respondents in academic practice and 95% of those in private practice), 34.4% (21/61) reported having IRB approval to conduct OIT, 22.9% (14/61) reported that a data safety monitoring board oversaw their administration of OIT, 26.2% (16/61) reported obtaining an IND to administer OIT, and 18% (11/61) reported they had none of these aforementioned oversights in place. Figure 1 details the location (venue) of where dose escalations occurred, and the frequency at which dose escalations occurred. Forty-six respondents provided information regarding compensation for OIT, with 23.9% reporting research or grant funding, 43.5% reporting insurance reimbursement, 13% reporting the patient paid out of pocket, and 19.6% reported offering the service pro bono. When asked to rank the relative importance of OIT as a means of developing a new revenue stream, however, 9.7% indicated this was a “most important” or “very important” consideration, and there was no significant difference in this trend when comparing academic versus private practice. Table 1 details specific differences in the administration of OIT between allergists identifying themselves as academic, versus those identifying themselves as non-academic.

Figure 1.

Reported locations of OIT administration and frequency of OIT dose escalations

The left-sided graph compares the reported venue or location in which the OIT is administered. The right-sided graph represents the reported range of the frequency of OIT dose escalation.

Table 1.

Specific trends related to the administration of OIT based on practice type

| Trend (total n for trend) | Academic practice | Non-academic practice | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Offering OIT (n=61) | 54.1% (n=33) | 45.9% (n=28) | < 0.001 |

| OIT protocol IRB approved (n=21) | 85.7% (n=18) | 14.3% (n=3) | < 0.001 |

| Informed consent obtained (n=42) | 47.6% (n=20) | 52.4% (n=22) | 0.61 |

| IND obtained for material (n=16) | 93.8 (n=15) | 6.3% (n=1) | < 0.001 |

| Challenge prior to entry (n=38) | 52.6% (n=20) | 47.3%(n=18) | 0.008 |

| Bill insurance or patient for service (n=26) | 0% (n=0) | 100% (n=26) | < 0.001 |

| Offer OIT to peanut (n=32) | 43.7%(n=14) | 56.3% (n=18) | 0.19 |

| Offer OIT to milk (n=31) | 29% (n=9) | 71% (22) | 0.007 |

| Offer OIT to egg (n=30) | 30% (n=9) | 70% (21) | 0.03 |

| Commercial food product used for OIT (n=25) | 24% (n=6) | 76% (n=19) | 0.02 |

All comparisons made using 2-sided Fisher’s exact test in a cross-tabulation, representing the relative percentages for the trend as stratified by practice type.

Among the 381 providers not participating in OIT currently, 74.3% indicated they are awaiting FDA approval before offering this therapy, 21.2% indicated they are considering offering OIT but not yet doing so, and 4.5% indicated they did not have the resources at present to offer OIT but were interested in doing so. Among this group, several questions regarding motivation to offer OIT were investigated. Regarding the importance of specific reasons as to why these providers were not participating in OIT at present, FDA approval was felt to be extremely important or important in 88.3% (n=326 responding to this item); better established safety data was felt to be extremely important or important to 90.9% (n=318 responding to this item); insurance coverage of the service was felt to be extremely important or important to 70.9% (n=310 responding to this item); and long-term data supporting the efficacy of the procedure was felt to be extremely important or important to 85.1% (n=316 responding to this item). When asked to rate the relative importance of factors that would specifically motivate these providers to offer OIT in the future, 90.5% indicated FDA approval, 91.9% a standardized product, 86% a CPT billing code, 93.9% additional data pertaining to the safety of OIT, 92.5% data indicating that OIT can produce long-term tolerance, and 88.5% indicated that a practice parameter or evidence-based guideline were felt to be extremely important or important factors. Table 2 describes a logistic regression model detailing factors that influence the odds of considering OIT at present versus waiting for FDA approval for OIT, which revealed significant positive associations with lack of belief in the importance for FDA approval of OIT or need for a standardized OIT product. A similar regression model was attempted to determine the association among providers participating in OIT between practice type and the same variables in the model in table 1, but 5 of the 6 included variables were perfect predictors of practice type, and no regression could be be generated.

Table 2.

Factors predictive of providers considering offering OIT or wanting to offer OIT but lacking the resources to do so

| Predictive Factors Identified | OR | P | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of a nearby practice offering OIT | 1.76 | 0.1 | 0.89–3.47 |

| Academic practice | .91 | 0.83 | 0.4–2.08 |

| Region (Northeast region as reference) | 1 | ||

| Mid-Atlantic | 2.57 | 0.1 | 0.83–7.97 |

| Southeast | 1.01 | 0.98 | 0.25–4.08 |

| Southwest | .65 | 0.5 | 0.19–2.24 |

| Upper-midwest | 2.11 | 0.15 | 0.76–5.89 |

| Far-west | 3.08 | 0.03 | 1.09–8.64 |

| Belief that…. | |||

| FDA approval for OIT is neutral/not important* | 20.52 | <0.001 | 5.64–74.6 |

| A standardized product for OIT is neutral/not important | 6.26 | 0.003 | 1.89–20.73 |

| A CPT code for OIT is neutral/not important | 1.36 | 0.51 | 0.55–3.35 |

| Better safety data for OIT are neutral/not important | .19 | 0.06 | 0.03–1.09 |

| Proof OIT can establish tolerance is neutral/not important | 1.63 | 0.47 | 0.44–6.04 |

| Having more support staff to conduct OIT is neutral/not important | 1.37 | 0.34 | 0.72–2.64 |

| Having clinical guidelines for OIT is neutral/not important | .77 | 0.63 | 0.26–2.26 |

Neutral/not important represents a combined range of opinion compared to very important/important

Discussion

There is intense interest surrounding OIT, given the growing problem of food allergy, promising preliminary data, and the lack of any existing interventional treatment for food allergy. Though OIT is not currently an FDA approved therapy, over 40% of respondents could identify at least one provider in their area who was currently administering OIT, or offering SLIT as a food allergy therapy (a similar therapeutic approach to oral tolerance also being researched and offered in clinical practice by some providers). At present, sentiment among AAAAI members completing this survey is clear and indicates several points: a) the vast majority of providers neither participate in OIT as a research project nor offer OIT as a clinical treatment service, though there are a sizable component who are considering doing so (in particular OIT as a clinical service); b) the issue of OIT not being an FDA-approved therapy is rather significant and is, at present, a barrier to many providers; and c) present knowledge gaps supporting further safety of OIT, its long-term efficacy and ultimate outcomes produced (a transient outcome such as desensitization vs. a lasting outcome such as tolerance), and lack of both a standardized OIT product and consensus parameter for how to administer OIT are very important to providers currently not offering OIT.

A small segment of respondents to this survey indicated they are currently participating in OIT. Academic providers studying OIT under research protocols slightly outnumbered providers in practice offering OIT. Though nearly all providers offering OIT obtained informed consent, those in practice did not readily obtain other types of oversight, whereas they were significantly more commonly obtained among academic researchers. These include obtaining IND approval to use food as a therapeutic substance from the FDA, having IRB approval, or having a research protocol for OIT with a safety monitoring board. How this affects the administration of OIT is not well understood, nor is if the food-allergic individual or family receiving the therapy is aware that such differences in oversight exist.15 Those in private practice administering OIT have contested the importance of many of these oversights, given that they advocate performing OIT as a service and not for research, where these oversights would be required and expected.11 However those in academic practice have advocated strongly that such safeguards are exceptionally important.7 This argument is one of exceptional importance but is beyond the scope of this survey. With respect to the type of therapy offered, there were no differences in the proportion of academic or private practices studying/administering peanut OIT, but significantly more private practices were using OIT to milk and egg. Among respondents, those in practice were significantly more likely to report that they charge the patient directly or bill insurance for this service than those in academic settings. However, there were no reported differences by type of practice in the reported relative importance of using OIT as a new revenue stream. There is no CPT code at present for food OIT, and it is unknown if insurance plans regularly reimburse for this procedure among those who provide OIT as a clinical service.

Within our sample, among providers not participating in OIT, there were a few factors that were predictive of those either strongly considering it or those who would if they had sufficient staff. These included reporting neutrality or lack of importance for OIT requiring FDA approval, neutrality or lack of importance that OIT protocols use a standardized food product, and neutrality or lack of importance that OIT have better present safety data. Proof of long-term efficacy (such as clinical tolerance), having clinical guidelines, other providers in the area offering the procedure, having a billing code, and most importantly type of practice were not significant. Though type of practice was not a significant influence in this model, provider behavior does appear to significantly change based on type of practice once the provider does engage in OIT, according to the trends detected in Table 1, and the fact that practice type was nearly perfectly predicted in an attempt to construct a regression model from those variables. This study was not designed, intended, nor powered to understand the influencing differences between academic and private practice styles pertaining to administering OIT, and was only designed to identify if any exist. However, in this sample we have identified potential major differences based on practice type, which would be of interest to examine further in a future study.

Limitations of this study include a limited response rate, exclusive distribution to providers on the AAAAI email distribution (which limited to a non-clustered, single staged, non-stratified sampling frame from the active AAAAI membership list and therefore allowed data collection only at the provider level), use of self-reported provider data, use of an internet based survey that allowed providers to not answer every question, and that only a small number of responding providers (~13.8%) were engaged in OIT. Self-reported measures, by provider or by patients, are subject to questions of validity and recall bias though the validity argument may be more appropriate to patient-reported attributes of a disease and not to provider-reported practices. Question to question drop out on selected responses, a consequence of not forcing participants to answer every question also likely created relative issues of imbalance for selected individual items though the nature of this study was purely exploratory and hypothesis-generating, not hypothesis-confirming. To more specifically address the issue of low response rate, per discussion with the AAAAI administrative team that oversees membership surveys similar to this project, our response rate is in line with past member surveys. We acknowledge that small response rates may result in reporting bias and limit the generalizability of these data to the membership as a whole. As stated, we caution that this study was exploratory, for needs assessment of a controversial and emerging therapy. There was no intent to specifically compare dosing style, target dose, or specific therapeutic goal, and intended only to categorize the range and variations of currently reported OIT practices. Complex analysis of the propensity for the average AAAAI member to respond or not respond to a survey was not available to account for the effect of participation bias or non-response bias. Similarly, subpopulation weighting was unable to be performed given use of a single strata and sampling unit, which also may have helped. We also consider that OIT may just be a topic of limited interest to all but a small segment of the membership, and that a response rate of 10–15% may actually be inclusive of all interested members in this topic. Our intent is not to suggest that these findings are applicable to the membership as a whole, but rather to position these findings as a measure of needs assessment and current understanding of OIT by some segment of the AAAAI membership.

We would like to highlight the issue of FDA approval as an important finding of the survey. Any item intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease is a drug or a biologic and therefore is subject to the pertinent FDA regulations. FDA has previously ruled that allergenic material (for example, peanut flour) used to treat food allergy as in OIT meets the definition of a drug.17 Hence, academic researchers study the use of OIT under Investigational New Drug guidelines, and at least one company is conducting OIT research with intent to develop one or more products to submit for approval through the New Drug Application process upon eventual completion of successful phase II and III trials (http://www.allergenresearch.com/). A large number of respondents expressed that FDA approval of OIT was an important step in considering providing this as a service. Although we intended the survey question to inquire about FDA approval of an OIT drug as described above, we cannot be certain that the respondents did not interpret the question to mean FDA approval in a broader sense (i.e. as a procedure), which is outside the FDA’s jurisdiction. Readily available allergenic foods such as peanut-containing candy or liquid milk could be used as treatment material during OIT, and FDA does not regulate medical practice.17 Regardless of the interpretation of the question, we believe that the results of this survey demonstrate a strong desire on the part of many of the responding practitioners for formal evaluation, regulation, and standardization of OIT by a governmental source. Similarly, many respondents expressed strong wishes for standardized protocols and practice guidelines to harmonize OIT’s implementation across sites. Thus, it is unclear at this time if or how OIT would gain approval by FDA or be regulated, but participants expressed a strong desire for the development of additional structures and safeguards by federal and professional agencies before changing their practice.

In conclusion, this study presents the first allergist-reported opinions about OIT and details data regarding the practice of OIT in the US. As OIT emerges as a potential therapy, backed by multi-centered research sponsored by the NIH, it is also currently being used as a marketed therapy in private practice. Very limited information is known about the differences in practice styles, which makes this information unique and timely. Though the majority of allergists do not offer OIT, among those who do, oversight and type of reimbursement differed significantly between those studying OIT at academic centers vs. those in practice offering OIT in their office. Among allergists who do not currently participate in OIT, there is strong desire for FDA approval, a standardized product, a CPT billing code, additional data pertaining to the safety of OIT, data indicating that OIT can produce long-term tolerance, and some sort of practice parameter or evidence-based guideline for OIT. However, factors most associated with consideration to initiate OIT as opposed to waiting for OIT to be FDA-approved included belief that FDA approval, enhanced safety data, and a CPT code for the procedure were not important. Though we have identified some preliminary traits associated with providers who currently administer OIT, as well as traits that may predict which future providers are more likely to start doing so soon, continued study to identify additional traits is needed.

What is already known about this topic

Promising preliminary studies suggest that OIT offers therapeutic potential. While many within the academic community strongly advocate for equipoise, a vocal minority in non-academic practice advocate that it is ready for general use.

What does this article add to our knowledge

Minimal information exists regarding current practices for food OIT. This study reveals key differences in beliefs and concerns among those identifying as OIT providers and non-providers, and also differences in academic versus non-academic OIT programs.

How does this study impact current management guidelines

Significant differences may exist in OIT occurring in academic vs. non-academic settings. Opinions, motivations, and styles vary regarding regulatory oversight requirements, use of standardized product, and safety. Ongoing assessment is needed to understand these variations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the OIT/SLIT Subcommittee in the design and creation of the survey instrument; the AAAAI Needs Assessment Committee in its review; Steve Folstein in the online deployment of the survey and collection and preparation of the data; the leadership of the Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee (especially Allan Bock, MD and Anna Nowak-Wegrzyn, MD) for guidance and critical review of the project, and the members of the Adverse Reactions to Foods OIT Subcommittee for their assistance in editing the survey drafts.

Abbreviations

- AAAAI

American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology

- CPT

Current Procedural Terminology

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- IND

Investigational New Drug

- OIT

oral immunotherapy

- SLIT

sublingual immunotherapy

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Khoriaty E, Umetsu DT. Oral immunotherapy for food allergy: towards a new horizon. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2013;5:3–15. doi: 10.4168/aair.2013.5.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mousallem T, Burks AW. Immunology in the Clinic Review Series; focus on allergies: immunotherapy for food allergy. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2012;167:26–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skripak JM, Nash SD, Rowley H, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo349 controlled study of milk oral immunotherapy for cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:1154–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varshney P, Jones SM, Scurlock AM, et al. A randomized controlled study of peanut oral immunotherapy: clinical desensitization and modulation of the allergic response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:654–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burks AW, Jones SM, Wood RA, et al. Oral immunotherapy for treatment of egg allergy in children. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:233–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:S1–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sampson HA. Peanut oral immunotherapy: is it ready for clinical practice? Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 2013;1:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wasserman RL, Sugerman RW, Mireku-Akomeah N, et al. Office-based oral immunotherapy for food allergy is safe and effective. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:290–1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.052. author reply 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thyagarajan A, Varshney P, Jones SM, et al. Peanut oral immunotherapy is not ready for clinical use. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:31–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenhawt MJ. Oral and sublingual peanut immunotherapy is not ready for general use. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2013;34:197–204. doi: 10.2500/aap.2013.34.3661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mansfield LE. Oral immunotherapy for peanut allergy in clinical practice is ready. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2013;34:205–9. doi: 10.2500/aap.2013.34.3666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wasserman RL, Factor JM, Baker JW, et al. Oral Immunotherapy for Peanut Allergy: Multipractice Experience With Epinephrine-treated Reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol:In Practice. 2014;2(1):91–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood RA, Sampson HA. Oral Immunotherapy for the Treatment of Peanut Allergy: Is It Ready for Prime Time? J Allergy Clin Immunol:In Practice. 2014;2(1):97–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Factor JM, Mendelson L, Lee J, et al. Effect of oral immunotherapy to peanut on food-specific quality of life. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:348–52. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Traister RS, Green TD, Mitchell L, et al. Community opinions regarding oral immunotherapy for food allergies. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:319–23. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DunnGalvin A, Chang WC, Laubach S, et al. Profiling families enrolled in food allergy immunotherapy studies. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e503–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. [Accessed February 12, 2014]; http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CBER/ucm133072.htm.