Abstract

Inflammasomes are large cytosolic multiprotein complexes that assemble in response to detection of infection- or stress-associated stimuli and lead to the activation of caspase-1-mediated inflammatory responses, including cleavage and unconventional secretion of the leaderless proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18, and initiation of an inflammatory form of cell death referred to as pyroptosis. Inflammasome activation can be induced by a wide variety of microbial pathogens and generally mediates host defense through activation of rapid inflammatory responses and restriction of pathogen replication. In addition to its role in defense against pathogens, recent studies have suggested that the inflammasome is also a critical regulator of the commensal microbiota in the intestine. Finally, inflammasomes have been widely implicated in the development and progression of various chronic diseases, such as gout, atherosclerosis, and metabolic syndrome. In this perspective, we discuss the role of inflammasomes in infectious and noninfectious inflammation and highlight areas of interest for future studies of inflammasomes in host defense and chronic disease.

In response to infection or stress, inflammasomes assemble in the cytosol and activate caspase-1-mediated inflammatory responses. They have also been implicated in various diseases (e.g., gout).

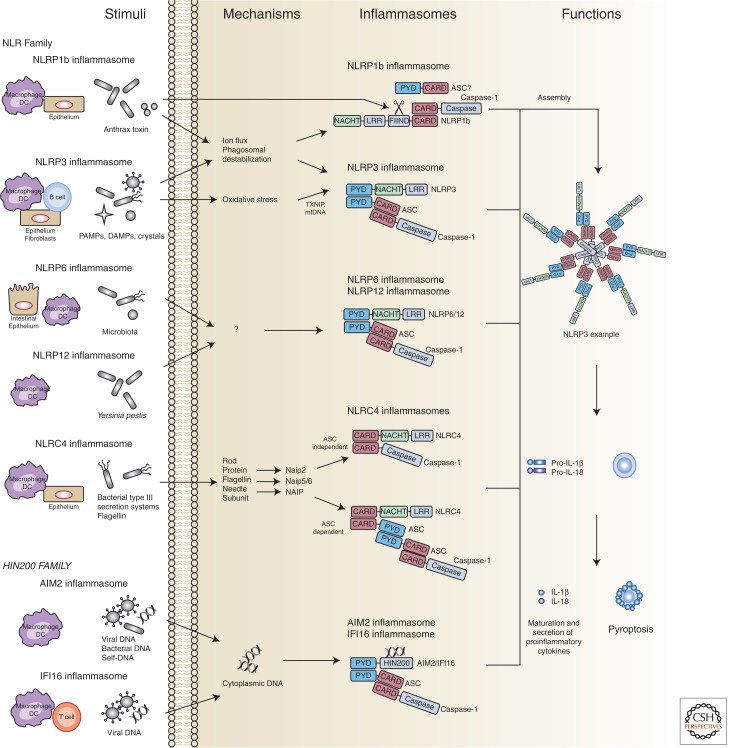

Inflammasomes are cytosolic molecular factories that typically consist of a sensor protein, the adaptor protein apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase-recruitment domain (ASC), and the proinflammatory caspase, caspase-1 (Schroder and Tschopp 2010). Inflammasome assembly can be triggered by sensing of a variety of stimuli that are associated with infection or cellular stress and culminates in the activation of caspase-1 (Fig. 1) (Strowig et al. 2012; de Zoete and Flavell 2013; Latz et al. 2013). Active caspase-1 subsequently processes the leaderless proinflammatory cytokines pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18, which are unconventionally secreted on caspase-1 cleavage. Therefore, inflammasome-mediated processing and secretion of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 enables a rapid, yet tightly regulated and highly inducible proinflammatory response. In addition to cytokine secretion, inflammasome activation can also trigger an inflammatory cell death dubbed pyroptosis, which serves to blunt intracellular pathogen replication (Miao et al. 2011).

Figure 1.

Inflammasome assembly can be triggered by sensing of a variety of stimuli that are associated with infection or cellular stress and culminates in the activation of caspase-1. DC, dendritic cell.

The NOD-like receptor (or nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat containing receptor; NLR) family was the first family of sensor proteins discovered to form inflammasomes and is comprised of 22 genes in humans and 33 genes in mice (Reed et al. 2003; Ting et al. 2008). NLRs are classified and named according to their domain structure; all NLRs (except NLRP10) contain a leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain, which is believed to mediate ligand binding, a nucleotide-binding domain (NBD), and a signaling domain (Ting et al. 2008). This signaling domain enables the recruitment of caspase-1 either directly, through a CARD, or indirectly, through a PYRIN domain, which can bind the PYRIN-CARD-containing adaptor ASC. In addition to the NLRs, recent studies have revealed additional families of genes that can nucleate the assembly of inflammasomes: the AIM2-like receptor (ALR) family, which possesses a HIN200 DNA-binding domain instead of an LRR (Schattgen and Fitzgerald 2011), and the RIG-I-like receptor (RLR) family (Ireton and Gale 2011). In this perspective, we will discuss the mechanisms of inflammasome activation, as well as the role of inflammasomes in host defense and disease pathology. In addition, we will attempt to highlight areas in which additional studies will be necessary to clarify or expand our current understanding of inflammasome biology.

MECHANISMS OF INFLAMMASOME ACTIVATION

Many of the most interesting and important questions in the inflammasome field pertain to the identities of the specific signals that lead to the assembly of the different NLRs, ALRs, and RLRs into active inflammasome complexes. Because the expression patterns, molecular structures, and stimuli that lead to activation of the different inflammasomes are highly variable, we will introduce and discuss each one separately.

The NLRP1 Inflammasome

The NLRP1 inflammasome was the first inflammasome to be discovered (Martinon et al. 2002). Although initial studies showed that the NLRP1 inflammasome could assemble spontaneously in cell lysates, more recent studies have described two natural ligands for NLRP1: muramyl dipeptide (MDP), a peptidoglycan fragment from both Gram positive and negative bacteria, and the Bacillus anthracis lethal toxin (Boyden and Dietrich 2006; Faustin et al. 2007). These ligands appear to be species-specific because MDP can activate human, but not mouse, NLRP1 (Faustin et al. 2007; Kovarova et al. 2012), whereas anthrax toxin has been shown to activate mouse NLRP1. NLRP1 also shows species-specific differences at the genetic level. Humans possess a single NLRP1 gene containing both a PYRIN and a CARD domain, whereas mice have a cluster of three homologous genes, Nlrp1a, Nlrp1b, and Nlrp1c, that contain a CARD but lack PYRIN domains. Nlrp1b was found to confer responsiveness to anthrax toxin in certain mouse strains, including Balb/c and 129S1; however, C57Bl/6 and SJL/J mice encode Nlrp1b variants that are not activated by the toxin (Boyden and Dietrich 2006).

The active fragment of anthrax lethal toxin consists of a zinc metalloproteinase that gains access to the cytosol of infected host cells. Nlrp1b does not directly bind anthrax toxin through its LRR motif, but instead appears to sense the proteolytic activity of the toxin because cleavage of NLRP1b itself proved sufficient for activation of the receptor (Levinsohn et al. 2012; Chavarria-Smith and Vance 2013). In contrast, human NLRP1 was shown to directly bind MDP. This binding induces a conformational change in NLRP1 that allows binding of ATP. ATP hydrolysis presumably then induces NLRP1 oligomerization and provides a platform to recruit and activate caspase-1 (Faustin et al. 2007). MDP-mediated caspase-1 activation by NLRP1 was enhanced by, but did not strictly require, the adaptor protein ASC. In addition to caspase-1, caspase-5 has also been implicated in binding the human NLRP1 complex (Martinon et al. 2002). Further studies will be necessary to reveal the precise mechanisms of NLPR1 activation, to identify any additional NLRP1 ligands, and to elucidate the functions of mouse NLRP1a and NLRP1c.

The NLRP3 Inflammasome

NLRP3 is by far the most thoroughly studied NLR. NLRP3 is expressed at low levels in myeloid cells and can be transcriptionally induced by Toll-like receptor agonists, such as LPS, and by inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, in an NF-κB-dependent manner (Bauernfeind et al. 2009). This is referred to as “signal one” and is necessary to induce transcription of pro-IL-1β and for the NLRP3 inflammasome to become responsive to “signal two,” which consists of a broad spectrum of infection and stress-associated signals (Schroder and Tschopp 2010). NLRP3-activating signals include pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and toxins from bacterial (Mariathasan et al. 2006; Duncan et al. 2009; He et al. 2010; Toma et al. 2010; Shimada et al. 2011), viral (Allen et al. 2009; Thomas et al. 2009; Ichinohe et al. 2010; Rajan et al. 2011), fungal (Gross et al. 2009; Hise et al. 2009; Joly et al. 2009), and protozoan pathogens (Shio et al. 2009), as well as host-derived damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as ATP, uric acid crystals, and amyloid-β fibrils (Mariathasan et al. 2006; Martinon et al. 2006; Halle et al. 2008). Because many diverse pathogens and pathogen-associated molecules can activate NLRP3, it is unlikely that all of these different stimuli are sensed directly. Instead, it is generally believed that all of these signals converge on a shared molecular event that specifically activates NLRP3.

Three main models for NLRP3 activation have been proposed: the ion flux model, the reactive oxygen species (ROS) model, and the lysosome rupture model. In the ion flux model, changes in cytosolic levels of specific cations, such as K+, Ca2+, and H+, are proposed to play a critical role in NLRP3 activation. Several NLRP3 activators were shown to directly induce potent ion fluxes. Extracellular ATP activates the ATP-gated ion channel P2X7 and triggers rapid K+ efflux (Franchi et al. 2007; Petrilli et al. 2007); Nigericin creates a K+ pore in the cell membrane (Mariathasan et al. 2006); the influenza M2 protein triggers export of H+ ions from the Golgi complex into the cytosol (Ichinohe et al. 2010); and high concentrations of extracellular Ca2+, increase cytosolic Ca2+, and cAMP (Lee et al. 2012; Murakami et al. 2012; Rossol et al. 2012). However, it is important to note that ion fluxes also activate other inflammasomes, such as NLRP1b (Fink et al. 2008; Wickliffe et al. 2008; Newman et al. 2009; Ali et al. 2011) and NLRC4 (Arlehamn et al. 2010). This suggests that ion fluxes might only modulate the threshold of caspase-1 activation but not serve as specific signals that trigger NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Lamkanfi and Dixit 2012).

Oxidative stress in the form of ROS has been widely implicated in NLRP3 activation and many NLRP3-activating stimuli, including ATP, alum, uric acid, and Nigericin, all induce ROS production (Schroder and Tschopp 2010). However, the precise role of ROS in NLRP3 inflammasome activation remains somewhat controversial. Initially, intracellular ROS produced via the NADPH oxidase system were thought to activate NLRP3; however, both mouse and human cells defective in NADPH oxidase show normal NLRP3 activation (Latz 2010; van Bruggen et al. 2010). In addition, although ROS inhibitors were shown to inhibit NLRP3 activation, this effect was likely because of the role of ROS in NF-κB mediated up-regulation of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β transcription (signal one) rather than its role in NLRP3 inflammasome activation itself (Bauernfeind et al. 2011). Recently, a report suggested that increased amounts of ROS were sensed by a complex of Thioredoxin and Thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP), with the latter binding to NLRP3 in response to oxidative stress (Zhou et al. 2010). Two other studies suggest an alternative role for ROS in inflammasome activation, in which oxidized mitochondrial DNA that is released from dysfunctional mitochondria can directly bind to and activate the NLRP3 inflammasome (Nakahira et al. 2011; Shimada et al. 2012). In contrast, ROS-independent mitochondria-derived cardiolipin was shown to bind and activate NLRP3 (Iyer et al. 2013). Although both ROS and mitochondria clearly play a role in inflammasome formation and activation, their precise function has yet to be fully clarified.

Finally, the NLRP3 inflammasome was proposed to sense lysosomal rupture during “frustrated” phagocytosis of crystalline or large particulate molecules, such as uric acid crystals, alum, silica, malarial hemozoin, hydroxyapatite, and amyloid-β (Schroder and Tschopp 2010; Jin et al. 2011). Inhibitors of the lysosomal protease Cathepsin B reduced NLRP3 activation, suggesting a role for proteolytic activity in the activation of NLRP3, similar to what was observed for NLRP1b (Hornung et al. 2008). However, Cathepsin B–deficient mice did not show impaired inflammasome responses (Dostert et al. 2009), and it was recently shown that particulate triggers of the NLRP3 inflammasome also require K+ efflux (Munoz-Planillo et al. 2013).

Despite considerable efforts, there is currently no agreement in the field on a universal mechanism by which the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated. One likely reason for this is the diversity of stimuli that can lead to NLRP3 activation, many of which have multiple effects on cell physiology. Recently, NLRP3 activation was shown to be even more complex with the discovery of noncanonical inflammasome activation (Kayagaki et al. 2011a). Although the canonical pathway activates NLRP3 directly, noncanonical activation involves the activation of caspase-11 by intracellular LPS released by rupture of bacteria-loaded phagolysosomes or by bacteria that actively enter the cytosol (Hagar et al. 2013; Kayagaki et al. 2013). Notably, the initial discovery of caspase-11-dependent inflammasome activation resulted from the realization that the caspase-1-deficient mice used by most researchers are in fact double knockouts, as they also lack a functional caspase-11 owing to a passenger mutation in the 129 mouse strain, from which the embryonic stem cells to generate the mice were derived (Kayagaki et al. 2011a). Although its nature is currently unknown, presumably the formation of an inflammasome-like complex containing a cytosolic LPS-receptor precedes caspase-11 activation. Also, the mechanism through which caspase-11 interplays with the NLRP3 pathway remains to be elucidated. A possible pathway is that activated caspase-11, which initiates pyroptosis in a similar manner as caspase-1, induces signals that are subsequently sensed by NLRP3. Future research will hopefully clarify the specific mechanisms of both canonical and noncanonical NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

The NLRP6 and NLRP12 Inflammasomes

Unlike NLRP3, which plays a major role in hematopoietic cells such as macrophages, NLRP6 is highly expressed in nonhematopoietic cells, including epithelial cells and goblet cells in the intestine (Elinav et al. 2011; Wlodarska et al. 2014), although there is a claim that it is mainly expressed in hematopoietic cells (Chen et al. 2011). Accordingly, NLRP6 plays an important role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis (Chen et al. 2011; Elinav et al. 2011; Normand et al. 2011; Hu et al. 2013). Despite the clear role of NLRP6 in intestinal homeostasis, many basic questions regarding NLRP6 biology remain unanswered. Early studies suggested that coexpression of NLRP6 with ASC results in a synergistic activation of caspase-1-dependent cytokine processing (Grenier et al. 2002), indicating that NLRP6 might indeed form an inflammasome. Furthermore, alterations in the microbiota associated with NLRP6 deficiency also occurred in mice lacking IL-18, suggesting that NLRP6 activation might trigger IL-18 release (Elinav et al. 2011). However, NLRP6 was recently shown to contribute to mucus secretion by goblet cells through the regulation of autophagy in an IL-1β- and IL-18-independent manner (Wlodarska et al. 2014). In addition, NLRP6 has been shown to be a negative regulator of NF-κB and MAPK signaling, leading to uncontrolled proinflammatory responses in NLRP6-deficient mice during bacterial challenge (Anand and Kanneganti 2013). Additional studies will be necessary to fully understand the role of NLRP6 in immune defense; in particular, identification of the signals that lead to NLRP6 activation, which remain completely unknown, will be critical.

NLRP12 possesses several features that resemble NLRP6. Similar to NLRP6, NLRP12 plays an important role in protecting against DSS-induced colitis and AOM/DSS-induced colon cancer (Zaki et al. 2011; Allen et al. 2012b). Furthermore, NLRP12 also appears to maintain intestinal homeostasis by negatively regulating inflammatory signaling pathways such as NF-κB and MAPK (Zaki et al. 2011; Allen et al. 2012b), and forced coexpression of NLRP12 and ASC results in synergistic activation of caspase-1 and secretion of IL-1β (Wang et al. 2002). In addition, a recent study showed that the NLRP12 inflammasome regulates IL-18 and IL-1β production after Yersinia pestis infection, and NLRP12-deficient mice were more susceptible to bacterial challenge (Vladimer et al. 2012). Like NLRP6, the specific PAMPs or DAMPs that can activate NLPR12, and the precise mechanism of activation, await identification.

The NLRC4 Inflammasome

The mechanism of NLRC4 activation appears to be relatively clear in comparison to the other inflammasomes. NLRC4 is activated in response to many different bacterial pathogens, including Legionella pneumophila, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhimurium, and Shigella flexneri (Mariathasan et al. 2004; Amer et al. 2006; Franchi et al. 2006; Miao et al. 2006; Lamkanfi et al. 2007; Sutterwala et al. 2007; Suzuki et al. 2007; Miao et al. 2008). NLRC4 senses bacterial flagellin or structural components of the bacterial type III secretion system (T3SS) that are injected or leaked into the host cell (Miao et al. 2010c). These bacterial proteins are directly bound by NLR-family apoptosis-inhibiting proteins (NAIPs) in the cytosol. In mice, NAIP2 binds the T3SS rod protein, whereas NAIP5 and NAIP6 bind flagellin; in humans, the sole NAIP binds the T3SS needle subunit (Kofoed and Vance 2011; Zhao et al. 2011). NAIPs then interact with NLRC4 and trigger assembly of the NLRC4 inflammasome complex, resulting in activation of caspase-1, release of inflammatory cytokines and pyroptosis. NLRC4 inflammasome assembly was recently shown to require phosphorylation of NLRC4, which may drive additional conformational changes that are necessary for inflammasome assembly (Qu et al. 2012).

AIM2-Like Receptors and RIG-I-Like Receptors

Absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) and the ALRs are members of the PYHIN family, which consists of proteins that contain a PYRIN domain and the conserved DNA-binding domain hematopoietic IFN-inducible nuclear protein with 200-amino acids (HIN-200) domain (Schattgen and Fitzgerald 2011). Therefore, these proteins can theoretically bind nucleic acids and recruit ASC to trigger the formation of an inflammasome. Indeed, AIM2 can form an inflammasome whose assembly is stimulated by recognition of cytosolic DNA of bacterial or viral origin (Fernandes-Alnemri et al. 2010; Jones et al. 2010; Rathinam et al. 2010; Sauer et al. 2010), or self-DNA from apoptotic cells (Choubey 2012; Zhang et al. 2013). Recent crystal structures of AIM2 complexed with DNA have provided particular insight into the mechanism of AIM2 inflammasome activation. Binding of DNA to the HIN domain of AIM2 results in a conformational change and AIM2 oligomerization around the DNA molecule, which then allows for the recruitment of ASC and caspase-1 and inflammasome assembly (Jin et al. 2012, 2013).

In addition to AIM2, humans have three additional ALRs, IFI16, IFIX, and MNDA, whereas mice have an expanded repertoire of ALRs that includes at least 13 members (Brunette et al. 2012). Most of these ALRs remain poorly characterized; however, a number of murine ALRs were found to colocalize with ASC and trigger IL-1β production, suggesting that they can form inflammasomes (Brunette et al. 2012). Furthermore, human IFI16 can form an inflammasome in response to Kaposi's sarcoma–associated herpesvirus infection, and activation of IFI16 in quiescent “bystander” CD4 T cells during HIV infection was found to trigger massive pyroptosis of T cells and is proposed to be a main driver of depletion of CD4 T cells during progression to AIDS (Monroe et al. 2014).

Finally, the RIG-I like receptor (RLR) family member RIG-I, which is best known as an inducer of type I IFN production in response to recognition of viral RNA, was also shown to form an inflammasome (Poeck et al. 2010). However, it remains unclear what determines when RIG-I forms an inflammasome versus when it simply triggers type I IFN production.

INFLAMMASOMES IN HOST DEFENSE AGAINST INFECTIONS

Considering that the main effect of inflammasome activation is pyroptosis and/or the secretion of IL-1β and IL-18, protection against invading microorganisms is likely the primary function of this arm of the innate immune system (Franchi et al. 2012). This is further demonstrated by the abundance of microbe-sensing NLRs, ALRs, and RLRs described so far, which detect microorganisms both directly (e.g., NLRC4, AIM2, NLRP1b, IFI16, RIG-I) and indirectly (e.g., NLRP3). In general, inflammasome-activating microbes can be divided into three categories: intracellular pathogens, extracellular pathogens that secrete toxins or inject virulence proteins into the host cell, and passively “invading” commensals. All three types of inflammasome-activating microbes are frequently found at mucosal and nonmucosal surfaces throughout the body. Not surprisingly, inflammasome proteins are expressed at these surfaces, most prominently by macrophages and dendritic cells (Kummer et al. 2007; Lech et al. 2010; Guarda et al. 2011). Nonetheless, other cell types at the host–microbe interface are increasingly recognized to respond to invading microbes through inflammasome activation. Below, we discuss the main tissues and cells involved in inflammasome-mediated defense against microbial infections.

Intestine

The intestinal tract is continuously colonized with trillions of microbes and continuously exposed to new microbes that are ingested daily. Despite the abundance of commensal bacteria that can potentially activate inflammasomes, the function of inflammasomes in the intestine has been most clearly demonstrated in the context of pathogenic bacterial infections. In the majority of these infections, inflammasomes initiate protective responses: Salmonella typhimurium, Citrobacter rodentium, Listeria monocytogenes, and Clostridium difficile infections in mice are all exacerbated in the absence of caspase-1/11 and/or ASC, resulting in increased bacterial burdens, inflammatory responses, tissue damage, and death (Tsuji et al. 2004; Lara-Tejero et al. 2006; Raupach et al. 2006; Ng et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2012b).

Several NLRs have been implicated in the recognition of these pathogens. Both NLRP3 and NLRC4 were shown to detect S. typhimurium (Broz et al. 2010, 2012; Carvalho et al. 2012), and IL-1β and IL-18 were found to be important for controlling S. typhimurium infection (Raupach et al. 2006). Similar to S. typhimurium, C. rodentium infection results in NLRP3- and NLRC4-dependent inflammatory responses that limit bacterial burden and tissue pathology, which was proposed to be IL-18 dependent (Kayagaki et al. 2011b; Gurung et al. 2012b; Liu et al. 2012a; Alipour et al. 2013). Unlike for S. typhimurium, NLRP3 and NLRC4 were shown to sense C. rodentium in nonhematopoietic cells, most likely in intestinal epithelial cells (Gurung et al. 2012a; Nordlander et al. 2013; Song-Zhao et al. 2013). This matches the localization of C. rodentium, which does not invade host cells and instead remains firmly attached to intestinal epithelial cells. Other intestinal pathogens that were shown to activate inflammasomes are: (1) C. difficile, which secretes two NLRP3-activating toxins resulting in proinflammatory responses that restrict infection; (2) Yersinia, which can trigger both the NLRP3 and NLRC4 inflammasomes (Brodsky et al. 2010); (3) and the yeast Candida albicans, which has also been shown to activate both NLRP3 and NLRC4, leading to protection in mice (Hise et al. 2009; Joly et al. 2009; Tomalka et al. 2011). Because C. albicans is not known to express any of the currently known NLRC4 ligands, this suggests a novel pathway to activate this NLR.

The importance of inflammasome activation in mediating bacterial control is also highlighted by inflammasome-evasion strategies employed by several pathogens. This is nicely demonstrated by the food-borne pathogen L. monocytogenes; in vitro, L. monocytogenes induces inflammasome responses via NLRP3 through listeriolysin (Warren et al. 2008; Meixenberger et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2010), via NLRC4 through flagellin (Warren et al. 2008), and via AIM2 and RIG-I through released DNA (Kim et al. 2010; Sauer et al. 2010; Tsuchiya et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2010; Abdullah et al. 2012). However, DNA release is kept at a minimum in wild-type bacteria, and flagellin is strongly down-regulated during murine infection (Sauer et al. 2010, 2011). Flagellin-down-regulation is also observed for S. typhimurium, which limits NLRC4-mediated pyroptosis (Miao et al. 2010a). When intracellular flagellin expression is enforced, both S. typhimurium and L. monocytogenes are strongly attenuated because of the potent induction of NLRC4-mediated pyroptosis, showing the potential of this type of cell death to limit intracellular bacterial growth and spread (Miao et al. 2010b; Sauer et al. 2011). Inflammasome-evasion is also displayed by Yersinia, which secretes an effector protein that limits inflammasome activation by the Yersinia T3SS (Brodsky et al. 2010). The function of caspase-11-mediated pyroptosis remains more enigmatic. Although potentially limiting bacterial intracellular replication, S. typhimurium was shown to exploit this pathway as an “exit strategy” for further dissemination as caspase-11-deficient mice showed decreased infection severity (Broz et al. 2012).

Lung

A second major interface between the host and the environment is the lung. Although not as abundantly colonized with microbes as the intestinal tract, the surface of the lung, particularly in the upper airways, is continuously exposed to a wide variety of commensal and pathogenic bacteria, viruses, and fungi. As in the intestine, several different inflammasomes have been shown to detect invading bacteria in the lung: the NLRP3 inflammasome senses infection with Klebsiella pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus, the latter two through the detection of pore-forming toxins (Willingham et al. 2009; He et al. 2010; McNeela et al. 2010; Kebaier et al. 2012; Rotta Detto Loria et al. 2013); the NLRC4 inflammasome responds to a number of flagellated bacteria including Legionella pneumoniae and Burkholderia pseudomallei (Case et al. 2009; Ceballos-Olvera et al. 2011); the NLRP1b inflammasome is activated by secreted toxins from B. anthracis (Kovarova et al. 2012); and both the NLRP3 and AIM2 inflammasomes are proposed to play a role during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection (Dorhoi et al. 2012; Saiga et al. 2012). Despite the induction of potent proinflammatory immune responses, which might not always be desirable in the lung, the majority of inflammasome activation helps to fight and resolve bacterial lung infections through pyroptosis, IL-1β and IL-18 secretion.

The role of inflammasomes in protection against viral infections in the lung has been clearly demonstrated by multiple studies. Influenza A virus was shown to strongly activate NLRP3 in the lung, resulting in caspase-1-mediated inflammatory responses that provided protection against and healing after infection (Kanneganti et al. 2006; Allen et al. 2009; Ichinohe et al. 2009; Thomas et al. 2009). Similarly, several other lung viruses were shown to induce NLRP3-mediated immune responses, including Rhinovirus (Triantafilou et al. 2013b), human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) (Segovia et al. 2012; Triantafilou et al. 2013a), and Varicella-zoster virus (Nour et al. 2011). Whereas NLRP3 activation seems to occur mainly in macrophages, RIG-I was demonstrated to sense influenza A virus through detection of viral RNA in lung epithelial cells (Pothlichet et al. 2013), resulting in a protective type I interferon response. Interestingly, influenza A simultaneously uses the viral protein NS1 to inhibit RIG-I (Gack et al. 2009).

Several viral proteins have been shown to be responsible for NLRP3 activation. Interestingly, all of these proteins target membranes of intracellular organelles. The influenza A M2 and rhinovirus 2B ion channel proteins induce ion fluxes from the Golgi and/or endoplasmic reticulum (Ichinohe et al. 2010; Triantafilou et al. 2013b); the viroporin SH protein from RSV forms pores in Golgi membranes; and the influenza A protein PB1-F2 is incorporated in the membrane of phagolysosomes, in which it has an as-yet unknown function (McAuley et al. 2013). Although these viruses deliberately express these inflammasome-activating proteins, the subsequent initiation of proinflammatory immune responses is usually detrimental to the virus. From the host side, this highlights the strength of “ligand selection” by NLRP3; from the viral side, this suggests an evolutionary difficulty to avoid NLRP3 activation. To circumvent this problem, some viruses, like measles virus and several herpes viruses, have likely developed mechanisms to directly inhibit inflammasomes to remain “under the radar” of the immune system (Gregory et al. 2011; Komune et al. 2011; Johnson et al. 2013).

Although many lung pathogens can directly activate the inflammasome, an additional proinflammatory stimulus comes from host-derived DAMPs following infection-associated tissue damage. Sensing of this type of damage seems to be restricted to the NLRP3 inflammasome, which has been shown to be activated in response to damage-associated molecules like uric acid (Gasse et al. 2009), extracellular ATP (Riteau et al. 2010), and serum amyloid A (Ather et al. 2011). Whether this additional inflammasome activation is detrimental or beneficial depends on the type and severity of the infection.

Other Examples of Inflammasome Activation in Host–Microbial Interactions

Many other surfaces and cells that come in contact with microbes depend on inflammasome-mediated defense strategies. For instance, Francisella tularensis induces AIM2-mediated inflammatory responses in the skin during subcutaneous infection (Fernandes-Alnemri et al. 2010) and NLRP3 is activated by the skin commensal Propionibacterium acnes (Kistowska et al. 2014), by hepatitis C virus in hepatic macrophages (Burdette et al. 2012), and by encephalomyocarditis virus through the viroporin 2B (Ito et al. 2012). Systemically, CD4 T cells are subject to HIV-induced IFI16 activation, which leads to caspase-1-mediated pyroptosis and subsequent CD4 T-cell depletion (Doitsh et al. 2014; Monroe et al. 2014).

INFLAMMASOMES AND THE COMMENSAL MICROBIOTA

In addition to the many studies linking the inflammasome to defense against pathogenic microbes, recent studies have suggested that the inflammasome may also play a role in shaping the composition of the intestinal microbiota. Our group found that mice lacking NLRP6 harbored an altered intestinal microbiota that was characterized by the presence of Prevotellaceae species and conferred increased susceptibility to DSS-induced colitis. This alteration in microbial composition and susceptibility to colitis was communicable to wild-type mice through cohousing or flora transfer, which demonstrates that this phenotype is mediated by alterations in the intestinal microbiota (Chen et al. 2011; Elinav et al. 2011; Normand et al. 2011; Hu et al. 2013). A similar phenotype was observed in mice lacking other inflammasome components or effectors, including ASC−/−, caspase-1−/−, and IL-18−/− mice. This suggests that the assembly of an NLRP6 inflammasome and secretion of IL-18 are required for maintenance of intestinal hemostasis through regulation of the composition of the microbiota, and that the absence of the NLRP6 inflammasome leads to acquisition or expansion of potentially pathogenic members of the microbiota (Elinav et al. 2011). In addition to affecting susceptibility to DSS colitis, inflammasome-dependent alterations in the microbiota also exacerbated carcinogenesis in an inflammation-dependent model of colon cancer (Hu et al. 2013). Furthermore, alterations in the microbiota in mice deficient in NLRP3, NLRP6, or IL-18 conferred susceptibility to diet-induced metabolic syndrome, including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and progression to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and obesity (Henao-Mejia et al. 2012). The precise mechanisms by which NLRP6 regulates microbial composition in the intestine remain unclear, especially because the stimuli for NLRP6 activation are still completely unknown. However, it was recently found that NLRP6 mice display a defect in mucus secretion by goblet cells in the intestine, which leads to impaired mucosal defense (Wlodarska et al. 2014). Therefore, an attractive possibility is that defective mucus secretion in NLRP6 mice may favor outgrowth of potentially pathogenic members of the microbiota and invasion of the gut epithelial environment by these organisms.

Examination of the role of the inflammasome in regulation of the microbiota promises to be a particularly interesting area of research in the future and elucidation of the mechanisms by which inflammasomes are activated in response to members of the intestinal microbiota will be of particular importance.

NONMICROBIAL INFLAMMASOME ACTIVATORS AND DISEASE

Chronic, low-grade inflammation has been linked to a variety of diseases of both obvious and nonobvious inflammatory nature. The triggers of such inflammation can be either microbial derived (e.g., members of the microbiota, as discussed above) or nonmicrobial (e.g., undegraded self-nucleic acids). Nonmicrobial triggers of inflammation can be separated into two categories: endogenous (i.e., self-derived) and exogenous (i.e., environmental). In this section, we will focus on the role of nonmicrobial triggers of the inflammasome in a variety of diseases. Where possible, we will also highlight cases in which treatment with IL-1 blocking therapies has been attempted and assess its relative success or failure.

Cryopyrin-Associated Periodic Syndromes

The genesis of the inflammasome field lies in the discovery that the hereditary diseases Familial Cold Autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS) and Muckle–Wells syndrome are both caused by mutations in a single novel gene containing a PYRIN domain, which is now known as NLRP3 (Hoffman et al. 2001). Shortly thereafter, it was discovered that de novo mutations in NLRP3 also cause neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID), which is also known as chronic infantile neurological cutaneous and articular syndrome (CINCA) (Aksentijevich et al. 2002; Feldmann et al. 2002). These disorders are collectively referred to as Cryopyrin-Associated Periodic syndromes (CAPS) and are considered to be autoinflammatory rather than autoimmune because they are mediated primarily by cytokines of the innate immune system, most notably IL-1β (Kastner et al. 2010; Dinarello et al. 2012). Mice engineered to contain human mutant NLRP3 also show a CAPS-like disorder, and macrophages from these mice activate caspase-1 and secrete IL-1β directly in response to microbial PAMPs without the need for signal 2 (e.g., ATP) (Meng et al. 2009). This suggests that CAPS results from the proclivity of NLRP3 mutants to assemble into active inflammasomes in response to stimuli that are normally insufficient to trigger inflammasome activation.

CAPS patients are highly responsive IL-1 blockade, which suggests that dysregulated production of IL-1β by the NLRP3 inflammasome is the major driver of pathology in CAPS (Hoffman et al. 2004; Goldbach-Mansky et al. 2006; Dinarello et al. 2012; Jesus and Goldbach-Mansky 2014). However, a recent study looking at the role of IL-18 in mice with CAPS-associated NLRP3 mutations found that IL-18 deficiency, like IL-1β deficiency, also dramatically ameliorated disease (Brydges et al. 2013). Furthermore, mice lacking both IL-1β and IL-18 also maintained some residual caspase-1-dependent disease, suggesting that cytokine-independent effects of the inflammasome, such as pyroptosis, may also contribute to CAPS pathology.

Gout

Gout is a form of inflammatory arthritis that most commonly affects the joint at the base of the big toe and results from the pathological accumulation of uric acid, which is the end product of purine catabolism, and the subsequent formation and deposition of uric acid crystals (Rock et al. 2013). In 2006, it was discovered that uric acid crystals can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and trigger IL-1β secretion, which suggested that inflammasome activation and IL-1β secretion may be a critical driver of arthritis in gout (Martinon et al. 2006). Accordingly, IL-1 blockade was subsequently found to be a highly effective treatment for gout (So et al. 2007; Jesus and Goldbach-Mansky 2014). Osteoarthritis, which is characterized by the degeneration of cartilage, has also been shown to involve NLRP3 activation. Synovial uric acid correlated strongly with synovial fluid IL-1β and IL-18 in patients, and mice deficient in NLRP3 had significantly reduced pathogenesis in osteoarthritis mouse models (Denoble et al. 2011; Jin et al. 2011). Although IL-1 blocking therapy has so far shown less promising results as compared to the treatment of gout, the above results suggests that a detailed investigation of therapies targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome or its mediators in treating osteoarthritis might be fruitful.

Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a thickening of the artery wall caused by the accumulation and deposition of cholesterol, calcium, and cellular debris in atherosclerotic plaques (Grebe and Latz 2013). Because the accumulation of cholesterol crystals in atherosclerotic plaques is a common feature of atherosclerosis, and various crystals are known to trigger activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, the Latz group examined whether the inflammasome might be involved in atherosclerosis (Duewell et al. 2010). They found that cholesterol crystals could trigger NLRP3 inflammasome activation, and that the inflammasome contributed to the development of atherosclerosis in mice lacking the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor. Cholesterol crystals were also found to trigger NLRP3 activation in human macrophages (Rajamaki et al. 2010). Thus, inflammasome activation in response to cholesterol crystals may be a critical early trigger of inflammation in atherosclerosis. Notably, recent studies showed that the endocytic PRR CD36 is critical for NLRP3 activation by oxidized LDL, but not in vitro–generated cholesterol crystals (Sheedy et al. 2013). These studies suggest that receptor-mediated uptake of LDL is a primary event in crystal formation and, therefore, inflammasome activation during atherosclerosis (Sheedy et al. 2013). Despite these compelling findings, the importance of the NLRP3 inflammasome in atherosclerosis remains unclear because NLRP3 deficiency had no effect on atherosclerosis development in ApoE-deficient mice fed a high fat diet, which is another common model of atherosclerosis (Menu et al. 2011). However, caspase-1 and CD36 deficiency significantly reduced the severity of atherosclerosis in this model (Chi et al. 2004; Gage et al. 2012; Usui et al. 2012; Sheedy et al. 2013).

Although the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in atherosclerosis is controversial, the role of IL-1 appears to be clear: both IL-1β deficiency and IL-1 blockade can ameliorate atherosclerosis in mice (Elhage et al. 1998; Kirii et al. 2003). Clinical trials testing the effect of IL-1 blockade on atherosclerosis in humans are in progress (Sheedy and Moore 2013).

Alzheimer’s Disease and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Recent studies have suggested that misfolded protein aggregates lead to activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in two neurodegenerative diseases: Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Masters and O’Neill 2011; Walsh et al. 2014). Alzheimer’s disease is a chronic neurodegenerative disease that mainly affects cognitive functioning and is the most common cause of dementia. ALS, which is also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a neurodegenerative disease that results from the progressive death of motor neurons, which eventually leads to loss of control of voluntary muscles and, finally, paralysis and death. Both Alzheimer’s and ALS are associated with the accumulation of protein aggregates; in Alzheimer’s, the amyloid-β protein (Aβ) forms extracellular plaques that are thought to contribute to disease development, whereas mutant forms of superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) that form toxic aggregates are the best characterized cause of ALS (Walsh et al. 2014). Fibrilar Aβ was found to trigger activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in LPS-primed microglial cells, and inflammasome activation and IL-1β secretion contribute to the inflammatory response to Aβ in the brain (Halle et al. 2008). Furthermore, ALS-linked mutant SOD1 was also found to trigger inflammasome activation in microglia in a model of ALS and caspase-1 or IL-1β deficiency significantly ameliorated neurodegenerative disease in SOD1 mutant mice (Meissner et al. 2010a). Aggregates of prion proteins have also been shown to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, suggesting that aggregated proteins may represent a common class of sterile triggers of inflammasome activation (Hafner-Bratkovic et al. 2012; Shi et al. 2012). Finally, although most studies have focused on the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome, SNPs in NLRP1 have also been linked to Alzheimer’s disease (Pontillo et al. 2012a). This suggests that multiple NLRs may play important roles in neurodegenerative disorders.

Taken together, these data suggest that the inflammasome may contribute to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders that are associated with the accumulation of protein aggregates and where inflammation contributes to disease development and progression. Furthermore, they highlight inflammasome or IL-1 blocking therapies as potential treatments for neurodegenerative disease.

Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes

The role of the inflammasome in metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes (T2D) can be separated into two major mechanistic categories: (1) direct roles mediated by sensing of endogenous inflammasome activators; and (2) indirect roles mediated by inflammasome-associated alterations in the composition of the intestinal microbiota. As the latter has been described above (see the section Inflammasomes and the Commensal Microbiota), we will focus on the potential direct role of the inflammasome in metabolic syndrome in this section; however, it is important to note that alterations in the microbiota could also contribute to phenotypes discussed below because these studies did not consider or control for potential effects of the microbiota.

A number of studies have shown that mice deficient in NLRP3, caspase-1, and ASC are protected from high fat diet (HFD)–induced insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, inflammation, and, in some studies, obesity (Stienstra et al. 2010, 2011; Zhou et al. 2010; Vandanmagsar et al. 2011; Wen et al. 2011). Multiple potential mechanisms by which the NLRP3 inflammasome may become activated in HFD-induced metabolic syndrome have been proposed: through binding of TXNIP, which may respond to endoplasmic reticulum–mediated cell stress (Zhou et al. 2010; Lerner et al. 2012; Oslowski et al. 2012); by oligomers of islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP), a pancreatic hormone that is cosecreted with insulin and triggers IL-1β secretion by islet macrophages (Masters et al. 2010); by ceramide, a lipid that accumulates in adipose tissues in response to HFD (Vandanmagsar et al. 2011); by palmitate, a saturated fatty acid whose concentration in serum is elevated by HFD (Wen et al. 2011); and by endocannabinoids that, in a different model of T2D, activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages in a cannabinoid receptor-dependent manner (Jourdan et al. 2013).

Where tested, the effects of NLRP3 deficiency on diabetes in mice are partially phenocopied by IL-1R deficiency (Masters et al. 2010). Furthermore, inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation ameliorated metabolic changes associated with HFD (Stienstra et al. 2010; Zhou et al. 2010). In humans, proof-of-concept studies have suggested that IL-1 blockade may significantly ameliorate T2D (Larsen et al. 2007), and larger-scale clinical trials are underway to definitively determine the potential of this treatment strategy (Boni-Schnetzler and Donath 2013).

Autoimmunity

IL-1β and IL-18 are critical for the initiation and control of the adaptive immune response; for example, IL-1β is intimately involved in the instruction of Th17 responses, which are implicated in many autoimmune disorders, and IL-18 supports Th1 responses (Garlanda et al. 2013). For this reason, one might expect that the inflammasome would also play an important role in autoimmunity. Indeed, a variety of studies in both humans and mice have suggested that multiple NLRs play important roles in autoimmune disease. The clearest connection between autoimmunity and the inflammasome is in the case of NLRP1. SNPs in NLRP1 have been linked to vitiligo and vitiligo-associated Addison’s disease (Jin et al. 2007), Type 1 diabetes (Magitta et al. 2009), systemic lupus erythematosus (Pontillo et al. 2012b), Kawasaki disease (Onoyama et al. 2012), Addison’s disease (Magitta et al. 2009; Zurawek et al. 2010), celiac disease (Pontillo et al. 2011), rheumatoid arthritis (Sui et al. 2012), systemic sclerosis (Dieude et al. 2011), and autoimmune thyroid disease (Alkhateeb et al. 2013). Despite these findings, confirmation of the role of NLRP1 in autoimmunity in mice has remained challenging because mice have three orthologs of NLRP1, whereas humans have only one. Therefore, the mechanism by which NLRP1 SNPs influence autoimmunity remains largely unclear; however, a recent study found that autoimmunity-associated NLRP1 SNPs may lead to greater processing of IL-1β in response to inflammatory stimuli, such as TLR ligands (Levandowski et al. 2013).

Although most findings connecting NLRs to autoimmunity have focused on NLRP1, a few SNPs in NLRP3 have also been linked to autoimmunity. Mutations in NLRP3 have been linked to celiac disease (Pontillo et al. 2010, 2011), and type 1 diabetes (Pontillo et al. 2010). Furthermore, NLRP3-, and IL-1R-deficient mice show reduced disease in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis; this effect is likely a result of defective Th17 differentiation (Sutton et al. 2006; Gris et al. 2010).

Finally, AIM2 has also been suggested to play a role in autoimmunity and autoinflammation. AIM2 blockade was found to ameliorate development of autoimmunity in a model of lupus that is induced via immunization with DNA from apoptotic cells (Zhang et al. 2013). Furthermore, AIM2 has been implicated in the chronic skin disorder psoriasis (Dombrowski et al. 2011).

Environmental Inflammasome Activators: Allergens and Particulates

The role of the inflammasome in the allergic response remains less well studied than its role in antimicrobial defense or in chronic inflammatory diseases. However, a number of studies have shown that certain allergens can indeed trigger inflammasome activation. House dust mite allergens can trigger NLRP3 inflammasome activation in keratinocytes, and honey bee venom can trigger inflammasome activation in both keratinocytes and macrophages (Dai et al. 2011; Dombrowski et al. 2012; Palm and Medzhitov 2013). However, the role of the inflammasome in allergic responses to HDM and venoms remains unclear. Notably, in the case of bee venom, components of the inflammasome were dispensable for the allergic response and instead the inflammasome was critical for the early inflammatory response to envenomation (Palm and Medzhitov 2013). Also, NLRP3 was found to be dispensable for the allergic response to intranasal HDM allergen (Allen et al. 2012a). Aluminum hydroxide, which is an adjuvant notable for its ability to induce allergic responses under certain conditions, can also trigger NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Li et al. 2007, 2008; Eisenbarth et al. 2008; Franchi and Nunez 2008; Kool et al. 2008; McKee et al. 2009). Finally, the inflammasome has been linked to allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) because contact hypersensitivity, which is a model for ACD, was found to require the NLRP3 inflammasome (Sutterwala et al. 2006).

Particulate environmental substances have also been shown to activate the inflammasome. For example, both silica and asbestos can trigger activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and the inflammasome plays a critical role in the progressive pulmonary fibrotic disorders silicosis and asbestosis, which result from the inhalation of silica and asbestos, respectively (Cassel et al. 2008; Dostert et al. 2008; Hornung et al. 2008). Finally, necrosis triggered by pressure disruption, hypoxia, complement lysis, or chemically induced epithelial cell injury has also been shown to lead to activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome (Iyer et al. 2009; Li et al. 2009). This activation was mediated by ATP release from mitochondria from necrotic cells, and NLRP3 deficiency reduced mortality in a renal ischemic tubular necrosis model (Iyer et al. 2009).

PERSPECTIVE AND FUTURE PROSPECTS

It is abundantly clear that one of the major beneficial roles of the inflammasome is to sense microbial infection and mediate a rapid program of host defense through the immediate secretion of pre-made cytokines and triggering of cell death. These responses generally are highly efficient in fighting off infectious agents of various origins. However, many nonmicrobial activators of the inflammasome are also known, suggesting that inflammasomes can also function as sensors of nonmicrobial signals (e.g., sterile mediators of membrane damage or cellular stress). Most of these nonmicrobial triggers of the inflammasome have been studied mainly because of their pathological roles in disease, whereas examples of beneficial effects of inflammasome activation by nonmicrobial triggers are few and far between. Therefore, current studies support the idea that inflammasome activation by noninfectious triggers is largely unintentional. It is, however, possible that beneficial effects of inflammasome activation by nonmicrobial triggers have been overlooked. It is also notable that almost all known noninfectious triggers of the inflammasome mediate activation through NLRP3, which seems to be uniquely able to respond to a wide range of stimuli. So far it remains unclear whether other NLRs can also sense nonmicrobial signals of physiological stress.

Finally, there remain many NLRs whose respective roles in host defense and/or physiology are just beginning to be appreciated, such as NLRP10 (Eisenbarth et al. 2012), NLRC5 (Cui et al. 2010; Meissner et al. 2010b), NLRC3 (Schneider et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2014), and many more whose functions are still completely unknown. With these NLRs, one of the major hurdles to overcome seems to be identifying the activating signals. The reason that it has been so difficult to identify ligands and activities for these NLRs is unclear. However, one intriguing possibility is that these NLRs do not respond to the expected signals (e.g., microbial infection), do not engage traditional inflammasome effector responses (e.g., caspase-1 activation, IL-1β or IL-18 secretion, and pyroptosis), or trigger inflammasome activation in unexpected cell types (e.g., lymphocytes or goblet cells). Indeed, the majority of studies of the effects of inflammasome activation have focused on the roles of IL-1β, IL-18, and pyroptosis; furthermore, most studies have looked at inflammasome activation in macrophages. However, a few studies have highlighted potential cytokine- and pyroptosis-independent roles for the inflammasome; for example, inflammasome activation by pore-forming toxins triggers caspase-1-dependent activation of membrane repair (Gurcel 2006), and NLRC4 activation induced by cytosolic delivery of flagellin was shown to trigger rapid production of inflammatory lipid mediators in a caspase-1-dependent manner (von Moltke et al. 2012). Furthermore, it is clear that inflammasomes exist in multiple cell types, including both hematopoetic and nonhematopoetic cells. Additional examples of cytokine- and pyroptosis-independent effects of the inflammasome, and of roles for the inflammasome in additional cell types will presumably be uncovered in future studies. Such studies should even further expand our view of the role of the inflammasome in host physiology and antimicrobial defense.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a Rubicon Fellowship from the Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research (NWO) (M.R.d.Z.), the Cancer Research Institute Irvington Fellowship Program (N.W.P.), a fellowship from Howard Hughes Medical Institute-The Helen Hay Whitney Foundation (S.Z.), Department of Defense Grant (W81XWH-11-1-0745) (R.A.F.), and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (R.A.F. and M.R.d.Z.).

Footnotes

Editor: Ruslan M. Medzhitov

Additional Perspectives on Innate Immunity and Inflammation available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Abdullah Z, Schlee M, Roth S, Mraheil MA, Barchet W, Bottcher J, Hain T, Geiger S, Hayakawa Y, Fritz JH, et al. 2012. RIG-I detects infection with live Listeria by sensing secreted bacterial nucleic acids. EMBO J 31: 4153–4164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aksentijevich I, Nowak M, Mallah M, Chae JJ, Watford WT, Hofmann SR, Stein L, Russo R, Goldsmith D, Dent P, et al. 2002. De novo CIAS1 mutations, cytokine activation, and evidence for genetic heterogeneity in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID): A new member of the expanding family of pyrin-associated autoinflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum 46: 3340–3348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali SR, Timmer AM, Bilgrami S, Park EJ, Eckmann L, Nizet V, Karin M 2011. Anthrax toxin induces macrophage death by p38 MAPK inhibition but leads to inflammasome activation via ATP leakage. Immunity 35: 34–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alipour M, Lou Y, Zimmerman D, Bording-Jorgensen MW, Sergi C, Liu JJ, Wine E 2013. A balanced IL-1β activity is required for host response to Citrobacter rodentium infection. PLoS ONE 8: e80656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkhateeb A, Jarun Y, Tashtoush R 2013. Polymorphisms in NLRP1 gene and susceptibility to autoimmune thyroid disease. Autoimmunity 46: 215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen IC, Scull MA, Moore CB, Holl EK, McElvania-TeKippe E, Taxman DJ, Guthrie EH, Pickles RJ, Ting JP 2009. The NLRP3 inflammasome mediates in vivo innate immunity to influenza A virus through recognition of viral RNA. Immunity 30: 556–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen IC, Jania CM, Wilson JE, Tekeppe EM, Hua X, Brickey WJ, Kwan M, Koller BH, Tilley SL, Ting JP 2012a. Analysis of NLRP3 in the development of allergic airway disease in mice. J Immunol 188: 2884–2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen IC, Wilson JE, Schneider M, Lich JD, Roberts RA, Arthur JC, Woodford RM, Davis BK, Uronis JM, Herfarth HH, et al. 2012b. NLRP12 suppresses colon inflammation and tumorigenesis through the negative regulation of noncanonical NF-κB signaling. Immunity 36: 742–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amer A, Franchi L, Kanneganti TD, Body-Malapel M, Ozoren N, Brady G, Meshinchi S, Jagirdar R, Gewirtz A, Akira S, et al. 2006. Regulation of Legionella phagosome maturation and infection through flagellin and host Ipaf. J Biol Chem 281: 35217–35223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand PK, Kanneganti TD 2013. NLRP6 in infection and inflammation. Microbes Infect 15: 661–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlehamn CS, Petrilli V, Gross O, Tschopp J, Evans TJ 2010. The role of potassium in inflammasome activation by bacteria. J Biol Chem 285: 10508–10518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ather JL, Ckless K, Martin R, Foley KL, Suratt BT, Boyson JE, Fitzgerald KA, Flavell RA, Eisenbarth SC, Poynter ME 2011. Serum amyloid A activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and promotes Th17 allergic asthma in mice. J Immunol 187: 64–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauernfeind FG, Horvath G, Stutz A, Alnemri ES, MacDonald K, Speert D, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Wu J, Monks BG, Fitzgerald KA, et al. 2009. Cutting edge: NF-κB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J Immunol 183: 787–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauernfeind F, Bartok E, Rieger A, Franchi L, Nunez G, Hornung V 2011. Cutting edge: Reactive oxygen species inhibitors block priming, but not activation, of the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Immunol 187: 613–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boni-Schnetzler M, Donath MY 2013. How biologics targeting the IL-1 system are being considered for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Br J Clin Pharmacol 76: 263–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden ED, Dietrich WF 2006. Nalp1b controls mouse macrophage susceptibility to anthrax lethal toxin. Nat Genet 38: 240–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky IE, Palm NW, Sadanand S, Ryndak MB, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA, Bliska JB, Medzhitov R 2010. A Yersinia effector protein promotes virulence by preventing inflammasome recognition of the type III secretion system. Cell Host Microbe 7: 376–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broz P, Newton K, Lamkanfi M, Mariathasan S, Dixit VM, Monack DM 2010. Redundant roles for inflammasome receptors NLRP3 and NLRC4 in host defense against Salmonella. J Exp Med 207: 1745–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broz P, Ruby T, Belhocine K, Bouley DM, Kayagaki N, Dixit VM, Monack DM 2012. Caspase-11 increases susceptibility to Salmonella infection in the absence of caspase-1. Nature 490: 288–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunette RL, Young JM, Whitley DG, Brodsky IE, Malik HS, Stetson DB 2012. Extensive evolutionary and functional diversity among mammalian AIM2-like receptors. J Exp Med 209: 1969–1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brydges SD, Broderick L, McGeough MD, Pena CA, Mueller JL, Hoffman HM 2013. Divergence of IL-1, IL-18, and cell death in NLRP3 inflammasomopathies. J Clin Invest 123: 4695–4705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdette D, Haskett A, Presser L, McRae S, Iqbal J, Waris G 2012. Hepatitis C virus activates interleukin-1β via caspase-1-inflammasome complex. J Gen Virol 93: 235–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Carvalho FA, Nalbantoglu I, Aitken JD, Uchiyama R, Su Y, Doho GH, Vijay-Kumar M, Gewirtz AT 2012. Cytosolic flagellin receptor NLRC4 protects mice against mucosal and systemic challenges. Mucosal Immunol 5: 288–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case CL, Shin S, Roy CR 2009. Asc and Ipaf Inflammasomes direct distinct pathways for caspase-1 activation in response to Legionella pneumophila. Infect Immun 77: 1981–1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassel SL, Eisenbarth SC, Iyer SS, Sadler JJ, Colegio OR, Tephly LA, Carter AB, Rothman PB, Flavell RA, Sutterwala FS 2008. The Nalp3 inflammasome is essential for the development of silicosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 9035–9040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos-Olvera I, Sahoo M, Miller MA, Del Barrio L, Re F 2011. Inflammasome-dependent pyroptosis and IL-18 protect against Burkholderia pseudomallei lung infection while IL-1β is deleterious. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavarria-Smith J, Vance RE 2013. Direct proteolytic cleavage of NLRP1B is necessary and sufficient for inflammasome activation by anthrax lethal factor. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GY, Liu M, Wang F, Bertin J, Nunez G 2011. A functional role for Nlrp6 in intestinal inflammation and tumorigenesis. J Immunol 186: 7187–7194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi H, Messas E, Levine RA, Graves DT, Amar S 2004. Interleukin-1 receptor signaling mediates atherosclerosis associated with bacterial exposure and/or a high-fat diet in a murine apolipoprotein E heterozygote model: Pharmacotherapeutic implications. Circulation 110: 1678–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choubey D 2012. DNA-responsive inflammasomes and their regulators in autoimmunity. Clin Immunol 142: 223–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Zhu L, Xia X, Wang HY, Legras X, Hong J, Ji J, Shen P, Zheng S, Chen ZJ, et al. 2010. NLRC5 negatively regulates the NF-κB and type I interferon signaling pathways. Cell 141: 483–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Sayama K, Tohyama M, Shirakata Y, Hanakawa Y, Tokumaru S, Yang L, Hirakawa S, Hashimoto K 2011. Mite allergen is a danger signal for the skin via activation of inflammasome in keratinocytes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 127: 806–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denoble AE, Huffman KM, Stabler TV, Kelly SJ, Hershfield MS, McDaniel GE, Coleman RE, Kraus VB 2011. Uric acid is a danger signal of increasing risk for osteoarthritis through inflammasome activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 2088–2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zoete MR, Flavell RA 2013. Interactions between Nod-like receptors and intestinal bacteria. Front Immunol 4: 462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieude P, Guedj M, Wipff J, Ruiz B, Riemekasten G, Airo P, Melchers I, Hachulla E, Cerinic MM, Diot E, et al. 2011. NLRP1 influences the systemic sclerosis phenotype: A new clue for the contribution of innate immunity in systemic sclerosis-related fibrosing alveolitis pathogenesis. Ann Rheum Dis 70: 668–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA, Simon A, van der Meer JW 2012. Treating inflammation by blocking interleukin-1 in a broad spectrum of diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 11: 633–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doitsh G, Galloway NL, Geng X, Yang Z, Monroe KM, Zepeda O, Hunt PW, Hatano H, Sowinski S, Munoz-Arias I, et al. 2014. Cell death by pyroptosis drives CD4 T-cell depletion in HIV-1 infection. Nature 505: 509–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrowski Y, Peric M, Koglin S, Kammerbauer C, Goss C, Anz D, Simanski M, Glaser R, Harder J, Hornung V, et al. 2011. Cytosolic DNA triggers inflammasome activation in keratinocytes in psoriatic lesions. Sci Transl Med 3: 82ra38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrowski Y, Peric M, Koglin S, Kaymakanov N, Schmezer V, Reinholz M, Ruzicka T, Schauber J 2012. Honey bee (Apis mellifera) venom induces AIM2 inflammasome activation in human keratinocytes. Allergy 67: 1400–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorhoi A, Nouailles G, Jorg S, Hagens K, Heinemann E, Pradl L, Oberbeck-Muller D, Duque-Correa MA, Reece ST, Ruland J, et al. 2012. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by Mycobacterium tuberculosis is uncoupled from susceptibility to active tuberculosis. Eur J Immunol 42: 374–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dostert C, Petrilli V, Van Bruggen R, Steele C, Mossman BT, Tschopp J 2008. Innate immune activation through Nalp3 inflammasome sensing of asbestos and silica. Science 320: 674–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dostert C, Guarda G, Romero JF, Menu P, Gross O, Tardivel A, Suva ML, Stehle JC, Kopf M, Stamenkovic I, et al. 2009. Malarial hemozoin is a Nalp3 inflammasome activating danger signal. PLoS ONE 4: e6510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM, Vladimer G, Bauernfeind FG, Abela GS, Franchi L, Nunez G, Schnurr M, et al. 2010. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature 464: 1357–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JA, Gao X, Huang MT, O’Connor BP, Thomas CE, Willingham SB, Bergstralh DT, Jarvis GA, Sparling PF, Ting JP 2009. Neisseria gonorrhoeae activates the proteinase cathepsin B to mediate the signaling activities of the NLRP3 and ASC-containing inflammasome. J Immunol 182: 6460–6469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbarth SC, Colegio OR, O’Connor W, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA 2008. Crucial role for the Nalp3 inflammasome in the immunostimulatory properties of aluminium adjuvants. Nature 453: 1122–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbarth SC, Williams A, Colegio OR, Meng H, Strowig T, Rongvaux A, Henao-Mejia J, Thaiss CA, Joly S, Gonzalez DG, et al. 2012. NLRP10 is a NOD-like receptor essential to initiate adaptive immunity by dendritic cells. Nature 484: 510–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhage R, Maret A, Pieraggi MT, Thiers JC, Arnal JF, Bayard F 1998. Differential effects of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and tumor necrosis factor binding protein on fatty-streak formation in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation 97: 242–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elinav E, Strowig T, Kau AL, Henao-Mejia J, Thaiss CA, Booth CJ, Peaper DR, Bertin J, Eisenbarth SC, Gordon JI, et al. 2011. NLRP6 inflammasome regulates colonic microbial ecology and risk for colitis. Cell 145: 745–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustin B, Lartigue L, Bruey JM, Luciano F, Sergienko E, Bailly-Maitre B, Volkmann N, Hanein D, Rouiller I, Reed JC 2007. Reconstituted NALP1 inflammasome reveals two-step mechanism of caspase-1 activation. Mol Cell 25: 713–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann J, Prieur AM, Quartier P, Berquin P, Certain S, Cortis E, Teillac-Hamel D, Fischer A, de Saint Basile G 2002. Chronic infantile neurological cutaneous and articular syndrome is caused by mutations in CIAS1, a gene highly expressed in polymorphonuclear cells and chondrocytes. Am J Hum Genet 71: 198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Alnemri T, Yu JW, Juliana C, Solorzano L, Kang S, Wu J, Datta P, McCormick M, Huang L, McDermott E, et al. 2010. The AIM2 inflammasome is critical for innate immunity to Francisella tularensis. Nat Immunol 11: 385–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink SL, Bergsbaken T, Cookson BT 2008. Anthrax lethal toxin and Salmonella elicit the common cell death pathway of caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis via distinct mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 4312–4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi L, Nunez G 2008. The Nlrp3 inflammasome is critical for aluminium hydroxide-mediated IL-1β secretion but dispensable for adjuvant activity. Eur J Immunol 38: 2085–2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi L, Amer A, Body-Malapel M, Kanneganti TD, Ozoren N, Jagirdar R, Inohara N, Vandenabeele P, Bertin J, Coyle A, et al. 2006. Cytosolic flagellin requires Ipaf for activation of caspase-1 and interleukin 1β in salmonella-infected macrophages. Nat Immunol 7: 576–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi L, Kanneganti TD, Dubyak GR, Nunez G 2007. Differential requirement of P2X7 receptor and intracellular K+ for caspase-1 activation induced by intracellular and extracellular bacteria. J Biol Chem 282: 18810–18818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi L, Munoz-Planillo R, Nunez G 2012. Sensing and reacting to microbes through the inflammasomes. Nat Immunol 13: 325–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gack MU, Albrecht RA, Urano T, Inn KS, Huang IC, Carnero E, Farzan M, Inoue S, Jung JU, Garcia-Sastre A 2009. Influenza A virus NS1 targets the ubiquitin ligase TRIM25 to evade recognition by the host viral RNA sensor RIG-I. Cell Host Microbe 5: 439–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage J, Hasu M, Thabet M, Whitman SC 2012. Caspase-1 deficiency decreases atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-null mice. Can J Cardiol 28: 222–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlanda C, Dinarello CA, Mantovani A 2013. The interleukin-1 family: Back to the future. Immunity 39: 1003–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasse P, Riteau N, Charron S, Girre S, Fick L, Petrilli V, Tschopp J, Lagente V, Quesniaux VF, Ryffel B, et al. 2009. Uric acid is a danger signal activating NALP3 inflammasome in lung injury inflammation and fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 179: 903–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach-Mansky R, Dailey NJ, Canna SW, Gelabert A, Jones J, Rubin BI, Kim HJ, Brewer C, Zalewski C, Wiggs E, et al. 2006. Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease responsive to interleukin-1β inhibition. N Engl J Med 355: 581–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grebe A, Latz E 2013. Cholesterol crystals and inflammation. Curr Rheum Rep 15: 313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory SM, Davis BK, West JA, Taxman DJ, Matsuzawa S, Reed JC, Ting JP, Damania B 2011. Discovery of a viral NLR homolog that inhibits the inflammasome. Science 331: 330–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenier JM, Wang L, Manji GA, Huang WJ, Al-Garawi A, Kelly R, Carlson A, Merriam S, Lora JM, Briskin M, et al. 2002. Functional screening of five PYPAF family members identifies PYPAF5 as a novel regulator of NF-κB and caspase-1. FEBS Lett 530: 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gris D, Ye Z, Iocca HA, Wen H, Craven RR, Gris P, Huang M, Schneider M, Miller SD, Ting JP 2010. NLRP3 plays a critical role in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by mediating Th1 and Th17 responses. J Immunol 185: 974–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross O, Poeck H, Bscheider M, Dostert C, Hannesschlager N, Endres S, Hartmann G, Tardivel A, Schweighoffer E, Tybulewicz V, et al. 2009. Syk kinase signalling couples to the Nlrp3 inflammasome for anti-fungal host defence. Nature 459: 433–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarda G, Zenger M, Yazdi AS, Schroder K, Ferrero I, Menu P, Tardivel A, Mattmann C, Tschopp J 2011. Differential expression of NLRP3 among hematopoietic cells. J Immunol 186: 2529–2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurcel L, Abrami L, Girardin S, Tschopp J, van der Goot FG 2006. Caspase-1 activation of lipid metabolic pathways in response to bacterial pore-forming toxins promotes cell survival. Cell 126: 1135–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung P, Malireddi RK, Anand PK, Demon D, Vande Walle L, Liu Z, Vogel P, Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD 2012a. Toll or interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain-containing adaptor inducing interferon-β (TRIF)-mediated caspase-11 protease production integrates toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) protein- and Nlrp3 inflammasome-mediated host defense against enteropathogens. J Biol Chem 287: 34474–34483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung P, Malireddi RS, Anand PK, Demon D, Walle LV, Liu Z, Vogel P, Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti T-D 2012b. Toll or interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain-containing adaptor inducing interferon-β (TRIF)-mediated caspase-11 protease production integrates Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) protein-and Nlrp3 inflammasome-mediated host defense against enteropathogens. J Biol Chem 287: 34474–34483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner-Bratkovic I, Bencina M, Fitzgerald KA, Golenbock D, Jerala R 2012. NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophage cell lines by prion protein fibrils as the source of IL-1β and neuronal toxicity. Cell Mol Life Sci 69: 4215–4228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagar JA, Powell DA, Aachoui Y, Ernst RK, Miao EA 2013. Cytoplasmic LPS activates caspase-11: Implications in TLR4-independent endotoxic shock. Science 341: 1250–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halle A, Hornung V, Petzold GC, Stewart CR, Monks BG, Reinheckel T, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E, Moore KJ, Golenbock DT 2008. The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-β. Nat Immunol 9: 857–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Mekasha S, Mavrogiorgos N, Fitzgerald KA, Lien E, Ingalls RR 2010. Inflammation and fibrosis during Chlamydia pneumoniae infection is regulated by IL-1 and the NLRP3/ASC inflammasome. J Immunol 184: 5743–5754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henao-Mejia J, Elinav E, Jin C, Hao L, Mehal WZ, Strowig T, Thaiss CA, Kau AL, Eisenbarth SC, Jurczak MJ, et al. 2012. Inflammasome-mediated dysbiosis regulates progression of NAFLD and obesity. Nature 482: 179–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hise AG, Tomalka J, Ganesan S, Patel K, Hall BA, Brown GD, Fitzgerald KA 2009. An essential role for the NLRP3 inflammasome in host defense against the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe 5: 487–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman HM, Mueller JL, Broide DH, Wanderer AA, Kolodner RD 2001. Mutation of a new gene encoding a putative pyrin-like protein causes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle–Wells syndrome. Nat Genet 29: 301–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman HM, Rosengren S, Boyle DL, Cho JY, Nayar J, Mueller JL, Anderson JP, Wanderer AA, Firestein GS 2004. Prevention of cold-associated acute inflammation in familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome by interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Lancet 364: 1779–1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, Samstad EO, Kono H, Rock KL, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E 2008. Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat Immunol 9: 847–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Elinav E, Huber S, Strowig T, Hao L, Hafemann A, Jin C, Wunderlich C, Wunderlich T, Eisenbarth SC, et al. 2013. Microbiota-induced activation of epithelial IL-6 signaling links inflammasome-driven inflammation with transmissible cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: 9862–9867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinohe T, Lee HK, Ogura Y, Flavell R, Iwasaki A 2009. Inflammasome recognition of influenza virus is essential for adaptive immune responses. J Exp Med 206: 79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinohe T, Pang IK, Iwasaki A 2010. Influenza virus activates inflammasomes via its intracellular M2 ion channel. Nat Immunol 11: 404–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireton RC, Gale M Jr, 2011. RIG-I like receptors in antiviral immunity and therapeutic applications. Viruses 3: 906–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Yanagi Y, Ichinohe T 2012. Encephalomyocarditis virus viroporin 2B activates NLRP3 inflammasome. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer SS, Pulskens WP, Sadler JJ, Butter LM, Teske GJ, Ulland TK, Eisenbarth SC, Florquin S, Flavell RA, Leemans JC, et al. 2009. Necrotic cells trigger a sterile inflammatory response through the Nlrp3 inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 20388–20393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer SS, He Q, Janczy JR, Elliott EI, Zhong Z, Olivier AK, Sadler JJ, Knepper-Adrian V, Han R, Qiao L, et al. 2013. Mitochondrial cardiolipin is required for Nlrp3 inflammasome activation. Immunity 39: 311–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesus AA, Goldbach-Mansky R 2014. IL-1 blockade in autoinflammatory syndromes. Annu Rev Med 65: 223–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Mailloux CM, Gowan K, Riccardi SL, LaBerge G, Bennett DC, Fain PR, Spritz RA 2007. NALP1 in vitiligo-associated multiple autoimmune disease. N Engl J Med 356: 1216–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C, Frayssinet P, Pelker R, Cwirka D, Hu B, Vignery A, Eisenbarth SC, Flavell RA 2011. NLRP3 inflammasome plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of hydroxyapatite-associated arthropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 14867–14872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin T, Perry A, Jiang J, Smith P, Curry JA, Unterholzner L, Jiang Z, Horvath G, Rathinam VA, Johnstone RW, et al. 2012. Structures of the HIN domain:DNA complexes reveal ligand binding and activation mechanisms of the AIM2 inflammasome and IFI16 receptor. Immunity 36: 561–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin T, Perry A, Smith P, Jiang J, Xiao TS 2013. Structure of the absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) pyrin domain provides insights into the mechanisms of AIM2 autoinhibition and inflammasome assembly. J Biol Chem 288: 13225–13235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KE, Chikoti L, Chandran B 2013. Herpes simplex virus 1 infection induces activation and subsequent inhibition of the IFI16 and NLRP3 inflammasomes. J Virol 87: 5005–5018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joly S, Ma N, Sadler JJ, Soll DR, Cassel SL, Sutterwala FS 2009. Cutting edge: Candida albicans hyphae formation triggers activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome. J Immunol 183: 3578–3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JW, Kayagaki N, Broz P, Henry T, Newton K, O’Rourke K, Chan S, Dong J, Qu Y, Roose-Girma M, et al. 2010. Absent in melanoma 2 is required for innate immune recognition of Francisella tularensis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 9771–9776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdan T, Godlewski G, Cinar R, Bertola A, Szanda G, Liu J, Tam J, Han T, Mukhopadhyay B, Skarulis MC, et al. 2013. Activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome in infiltrating macrophages by endocannabinoids mediates β cell loss in type 2 diabetes. Nat Med 19: 1132–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanneganti TD, Body-Malapel M, Amer A, Park JH, Whitfield J, Franchi L, Taraporewala ZF, Miller D, Patton JT, Inohara N, et al. 2006. Critical role for Cryopyrin/Nalp3 in activation of caspase-1 in response to viral infection and double-stranded RNA. J Biol Chem 281: 36560–36568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastner DL, Aksentijevich I, Goldbach-Mansky R 2010. Autoinflammatory disease reloaded: A clinical perspective. Cell 140: 784–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayagaki N, Warming S, Lamkanfi M, Vande Walle L, Louie S, Dong J, Newton K, Qu Y, Liu J, Heldens S, et al. 2011a. Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature 479: 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayagaki N, Warming S, Lamkanfi M, Walle LV, Louie S, Dong J, Newton K, Qu Y, Liu J, Heldens S 2011b. Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature 479: 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayagaki N, Wong MT, Stowe IB, Ramani SR, Gonzalez LC, Akashi-Takamura S, Miyake K, Zhang J, Lee WP, Muszynski A, et al. 2013. Noncanonical inflammasome activation by intracellular LPS independent of TLR4. Science 341: 1246–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]