Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Buprenorphine is a potent analgesic with high affinity at μ, δ and κ and moderate affinity at nociceptin opioid (NOP) receptors. Nevertheless, NOP receptor activation modulates the in vivo activity of buprenorphine. Structure activity studies were conducted to design buprenorphine analogues with high affinity at each of these receptors and to characterize them in in vitro and in vivo assays.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

Compounds were tested for binding affinity and functional activity using [35S]GTPγS binding at each receptor and a whole-cell fluorescent assay at μ receptors. BU08073 was evaluated for antinociceptive agonist and antagonist activity and for its effects on anxiety in mice.

KEY RESULTS

BU08073 bound with high affinity to all opioid receptors. It had virtually no efficacy at δ, κ and NOP receptors, whereas at μ receptors, BU08073 has similar efficacy as buprenorphine in both functional assays. Alone, BU08073 has anxiogenic activity and produces very little antinociception. However, BU08073 blocks morphine and U50,488-mediated antinociception. This blockade was not evident at 1 h post-treatment, but is present at 6 h and remains for up to 3–6 days.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

These studies provide structural requirements for synthesis of ‘universal’ opioid ligands. BU08073 had high affinity for all the opioid receptors, with moderate efficacy at μ receptors and reduced efficacy at NOP receptors, a profile suggesting potential analgesic activity. However, in vivo, BU08073 had long-lasting antagonist activity, indicating that its pharmacokinetics determined both the time course of its effects and what receptor-mediated effects were observed.

LINKED ARTICLES

This article is part of a themed section on Opioids: New Pathways to Functional Selectivity. To view the other articles in this section visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2015.172.issue-2

Table of Links

| TARGETS | LIGANDS | |

|---|---|---|

| δ receptor | Buprenorphine | Morphine |

| κ receptor | DAMGO | Nociceptin/orphanin FQ, NF/OFQ |

| μ receptor | DPDPE | SB612111 |

| NOP receptor | Ethylketocyclazocine, (-) EKC | U50,488 |

| β-Funaltrexamine, β-FNA |

This Table lists the protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (Alexander et al., 2013; Cox et al., 2015).

Introduction

The affinity and efficacy of opioid compounds generally can explain their ultimate physiological activity. Based upon original observations, a compound with high efficacy at μ receptors was likely to be analgesic with the concomitant side effects of constipation, respiratory depression and euphoria leading to abuse liability. Conversely, a compound with high efficacy at κ receptors was likely to be analgesic, with reduced constipation and respiratory depression, but dysphoria rather than euphoria (Martin et al., 1976; Martin, 1983).

If high-efficacy μ receptor agonists, such as morphine and fentanyl are plagued by dangerous side effects such as abuse liability and respiratory depression, in theory, lower efficacy at the opioid receptors would potentially lead to an analgesic with a lower μ receptor-mediated side effect profile. This concept was epitomized by buprenorphine, a high-affinity partial μ receptor agonist and high-affinity δ and κ receptor antagonist (Cowan et al., 1977; Toll et al., 1998; Lutfy and Cowan, 2004). More recently, it was determined that buprenorphine also has moderate affinity at nociceptin opioid (NOP) receptors, the fourth member of the opioid receptor family (Huang et al., 2001; Spagnolo et al., 2007). Buprenorphine has been used successfully as an analgesic since the 1980s. Although it is a potent analgesic, the antinociceptive activity is dependent upon the stimulus intensity and it can have an inverted U-shaped dose response curve, with reduced antinociception at high doses (Cowan et al., 1977; Lutfy et al., 2003). Buprenorphine also has reduced abuse liability and reduced respiratory depression, compared with morphine, a feature attributed to the partial agonist component of its profile (Mello et al., 1993; Dahan et al., 2015). Furthermore, because it is a lipophilic, long-lasting compound, buprenorphine has demonstrated great success as an opioid abuse maintenance medication, as an alternative to methadone. Buprenorphine also blocks self-administration of both cocaine and alcohol in various species, including humans (Mello et al., 1989; Montoya et al., 2004). It has been suggested that the downward portion of the inverted U-shaped dose response for antinociception, as well as the ability of buprenorphine to attenuate drug seeking is due to activation of NOP receptors (Lutfy et al., 2003; Ciccocioppo et al., 2007). This hypothesis is consistent with many studies demonstrating (i) other mixed NOP/μ receptor ligands, in addition to buprenorphine, also have antinociception that can be potentiated by the NOP antagonist SB612111 ((5S,7S)-7-{[4-(2,6-dichlorophenyl)piperidin-1-yl]methyl}-1-methyl-6,7,8,9-tetrahydro-5H-benzo[7]annulen-5-ol), indicating that μ receptor-mediated antinociception can be reduced by the NOP agonist activity residing in the same molecule (Spagnolo et al., 2008; Khroyan et al., 2009); and (ii) nociceptin/orphanin FQ (N/OFQ) as well as selective NOP receptor agonists have been demonstrated to attenuate both conditioned place preference and self-administration of a variety of abused drugs (Kotlinska et al., 2003; Ciccocioppo et al., 2004; Sakoori and Murphy, 2004; Shoblock et al., 2005).

If activity at the NOP receptor can modulate buprenorphine's activity, it seems reasonable that a buprenorphine analogue with high affinity at NOP receptors would further mediate opiate behaviours. There are two directions in which NOP binding could modulate the activity of buprenorphine. If NOP affinity and efficacy were increased, the compound might have reduced abuse liability compared with buprenorphine itself or act as a better drug abuse medication. Conversely, a buprenorphine analogue with higher affinity at NOP receptors but with reduced efficacy at this receptor might have greater antinociceptive activity.

Accordingly, we have begun to conduct structure activity studies to identify buprenorphine analogues with increased affinity at NOP receptors. To this end, we produced a series of buprenorphine analogues with high affinity at all four receptors in the opioid receptor family with variable efficacies at NOP receptors (Cami-Kobeci et al., 2011). The first compound tested from this series was BU08028, a partial agonist at both NOP and μ receptors, which proved to have μ receptor-mediated antinociception and reward that overpowered NOP-mediated inhibition (Khroyan et al., 2011). Here, we discuss BU08073, which has high affinity at all four receptors, exhibits in vitro partial agonist activity at μ receptors, similar to buprenorphine, but has virtually no agonist activity at κ, δ and NOP receptors. However, in vivo, BU08073 produces an unusual profile in that it has virtually no antinociceptive activity in mice when tested alone, but has long-lasting antagonist activity at both μ- and κ-opioid receptors using the tail-flick assay.

Materials and methods

Animals

All animal care and experimental procedures complied with the guidelines of SRI International and of the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research [National Research Council (US) Committee on Guidelines for the Use of Animals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research, 2003] and were approved by the institutional ACUC of SRI International. All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010). A total of 221 animals were used in the experiments described here.

Male ICR mice (Charles River, Hollister, CA, USA) weighing 25–30 g at the start of the experiment were used. Animals were group-housed (n = 10/cage) under standard laboratory conditions using nestlets as environmental enrichment in their cages and were kept on a 12:12 h day/night cycle (lights on at 7:00 am). Testing was conducted during the animals' light cycle between 9:00 am and 2:00 pm. Animals were handled for 3–4 days before the experiments were conducted. On behavioural test days, animals were transported to the testing room and acclimated to the environment for 1 h.

In vitro characterization

Cell culture

All receptors were individually expressed in CHO cells stably transfected with human receptor cDNA, The cells were grown in DMEM with 10% FBS, in the presence of 0.4 mg·mL−1 G418 and 0.1% penicillin/streptomycin, in 100 mm polystyrene culture dishes. For binding assays, the cells were scraped off the plate at confluence. Receptor expression levels were 1.2, 1.6, 1.8 and 3.7 pmol per mg protein for the NOP, μ-, κ- and δ-opioid receptors respectively.

Receptor binding

Binding to cell membranes was conducted in a 96-well format, as described previously (Dooley et al., 1997; Toll et al., 1998). Briefly, cells were removed from the plates, homogenized in 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, using a Polytron homogenizer (Brinkmann Instruments, Westbury, NY, USA), then centrifuged once and washed by an additional centrifugation at 27 000× g for 15 min. The final pellet was re-suspended in Tris, and the suspension incubated with [3H]DAMGO (51 Ci·mmol−1, 1.6 nM), [3H]Cl-DPDPE (42 Ci·mmol−1, 1.4 nM), [3H]U69,593 (N-methyl-2-phenyl-N-[(5R,7S,8S)-7-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)-1-oxaspiro[4.5]dec-8-yl]acetamide) (41.7 Ci·mmol−1, 1.9 nM) or [3H]N/OFQ (120 Ci·mmol−1, 0.2 nM) for binding to, μ-, δ-, κ- and NOP receptors respectively. [3H]DAMGO [3H]Cl-DPDP, and [3H]N/OFQ were supplied by the NIDA drug supply program. [3H]U69,593 and [35S]GTPgS were from Perkin Elmer (Waltham MA, USA). Non-specific binding was determined with 1 μM of unlabelled DAMGO ([D-Ala2, N-MePhe4, Gly-ol]-enkephalin), DPDPE([D-Pen2,D-Pen5]enkephalin), ethylketocyclazocine and N/OFQ respectively. Samples were incubated for 60 min at 25°C in a total volume of 1.0 mL, with 15 μg protein per well. The reaction was terminated by filtration using a Tomtec 96 harvester (Orange, CT, USA) through glass fibre filters and radioactivity was counted on a Pharmacia Biotech β-plate liquid scintillation counter (Piscataway, NJ, USA). IC50 values were calculated using Graphpad/Prism (ISI, San Diego, CA, USA) and Ki values were determined by the method of Cheng and Prusoff (1973).

[35S]GTPγS binding

[35S]GTPγS binding was conducted basically as described by Traynor and Nahorski (1995). Cells were scraped from tissue culture dishes into 20 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, then centrifuged at 500× g for 10 min. Cells were resuspended in this buffer and homogenized using a Polytron homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 27 000× g for 15 min, and the pellet resuspended in Buffer A, containing: 20 mM HEPES, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4. The suspension was re-centrifuged at 27 000× g and suspended once more in Buffer A. For the binding assay, membranes (8–15 μg protein) were incubated with [35S]GTPγS (50 pM), GDP (10 μM), and the appropriate compound, in a total volume of 1.0 mL, for 60 min at 25°C. Samples were filtered over glass fibre filters and counted as described for the binding assays. For the antagonist assay, various concentrations of BU08073 were incubated in the presence of 100 nM N/OFQ to determine antagonist potency. Kb was determined by a modification of Cheng and Prusoff (1973) such that Kb = IC50/(1 + [L]/EC50), where [L] is the concentration of N/OFQ and the EC50 of N/OFQ was 1.1 nM.

Membrane potential assay

Functional activity of μ receptors in intact cells was determined by measuring receptor-induced membrane potential change, which can be directly read by Molecular Devices Membrane Potential Assay Kit (Blue Dye) using the FlexStation 3® microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). This experiment is similar to a recently published assay in which forskolin induced changes in cAMP levels, which ultimately induced hyperpolarization of CHO cells (Knapman et al., 2014). In this experiment, CHO cells transfected with human μ-opioid receptors were seeded in a 96-well plate (30 000 cells per well) 1 day prior to the experiments. For agonist assays, after brief washing, the cells were loaded with 225 μL of HBSS assay buffer (HBSS with 20 mM of HEPES, pH 7.4), containing the blue dye, and incubated at 37°C. After 30 min, 25 μL of the appropriate compounds were automatically dispensed into the wells by the FlexStation and receptor stimulation-mediated membrane potential change is recorded every 3 s for 60 s by reading 550–565 nm fluorescence excited at 530 nm wavelength. For the antagonist assay, the cells are loaded with 200 μL HBSS buffer containing the blue dye and incubated at 37°C. After 15 min, 25 μL of naloxone was added into corresponding wells, and after another 15 min, 25 μL of DAMGO or test compounds was added into wells by the FlexStation, with fluorescence measured as described above. The change in fluorescence represents the maximum response, minus the minimum response for each well.

In vivo characterization

Assessment of thermal nociception

Tail-flick assay

Acute nociception was assessed using the tail-flick assay with an analgesia instrument (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA) that uses radiant heat. This instrument is equipped with an automatic quantification of tail-flick latency, and a 15 s cut-off to prevent damage to the animal's tail. During testing, the focused beam of light was applied to the lower half of the animal's tail, and tail-flick latency was recorded. Baseline values for tail-flick latency were determined before drug administration in each animal. The mean basal tail-flick latency was 4.34 ± 0.10 SEM.

Drug regimens

In the first experiment, the effects of BU08073 alone were tested. Animals received a s.c. injection of BU08073 (0.3–10 mg·kg−1, n = 6–9/group; total n = 48) and were tested 1/2, 1 and 4 h post-injection. Controls received an injection of vehicle prior to testing. Because BU08073 alone did not produce a high level of antinociception, the effect of 3 mg·kg−1 BU08073 on morphine (μ receptor-mediated) antinociception was examined. In addition, given that BU08073 seems to be a potent antagonist at κ receptors, its effects on U50,488 (κ receptor agonist) antinociception was also tested. For these experiments, animals received a s.c. injection of BU08073 and 30 min prior to testing they received a s.c. injection of morphine (10 mg·kg−1) or U50,488 (30 mg·kg−1). The pretreatment time for BU08073 was altered such that tail-flick latencies were measured 1 h, 6 h, 1 day, 3 days, 6 days and 10 days following the injection of BU08073. Different groups of animals (n = 8 per time point) were used at each post-injection time point so animals received one injection of BU08073 and 30 min prior to their test time they received an injection of either morphine or U50,488 (n = 128 total for interaction experiments). Antinociception (% maximum potential effect; % MPE) was quantified by the following formula: % MPE = 100 * [(test latency – baseline latency)/(15 – baseline latency)]. If the animal did not respond before the 15-s cut-off, the animal was assigned a score of 100%.

Assessment of anxiety

Elevated zero maze

This maze is an elevated annular platform with two opposite quadrants enclosed with clear Plexiglas and two open quadrants connecting the two enclosed quadrants (Shepherd et al., 1994). The elevated zero maze similar to the elevated plus maze has been used as a model to measure anxiety in rodents repeatedly (Shepherd et al., 1994; Braun et al., 2011; Khroyan et al., 2012). In our laboratory, we have shown that diazepam significantly increased the amount of time spent in the open arms relative to vehicle controls indicative of its anxiolytic properties (Khroyan et al., 2012). Similar lighting conditions and experimental set-up were used as before (Khroyan et al., 2012) and animals were placed on the edge of the enclosed quadrant and behaviour was assessed for 5 min. The amount of time spent in the open quadrants, latency to enter the open quadrant and frequency of head dips over the edge of the platform were measured by an observer unaware of the animal's treatment group.

Animals received a s.c. injection of BU08073 (3 mg·kg−1) and were tested at the 6 h, 1 day and 6 day post-injection time points. Different groups of animals were used at each time point tested (n = 10). Separate groups of animals served as controls and received vehicle injection and were tested at the various time points indicated above. From previous experiments in our laboratory, given that the data from animals given vehicle injection at different ‘pretreatment’ time points and testing on the zero maze has not shown a difference we used an n = 5 at each time point (unpublished data). Because all of the vehicle animals at each time point did not differ (F2,12 = 0.006; no differences observed with scatterplot data), the vehicle data were combined resulting in n = 15 in the vehicle group. A total number of 45 animals were used for these experiments.

Data analysis

Data from all animals tested were analysed.

Data from the binding assays with radio-labelled substrates were analysed with the program from Graphpad Prism (La Jolla, CA, USA). Data from the functional assays of μ receptors (FlexStation dye assays) were also analysed by Graphpad PRISM to determine the EC50 and IC50 values.

Data from assays of nociception were analysed as follows. Results examining the effects of BU08073 alone were analysed by using repeated measures anova with dose (0, 0.3–10 mg·kg−1) as the between-group variable and post-injection time point (1/2, 1 and 4 h) as the repeated measure followed by one-way anova and Bonferonni post hoc tests where appropriate. For the effects of BU08073 on morphine or U50,488-induced antinociception, given that one dose of each drug were used and that different animals were used for each time point, a one-way anova with BU08073 post-injection time point (1 h, 6 h, 1 day, 3 days, 6 days and 10 days) was used as the between-group variable. Significant effects were further analysed by Bonferonni post hoc tests. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

For the assays of anxiety, the amount of time spent in the open quadrants, latency to enter the open quadrant and the frequency of head dips were analysed with one-way anova with BU08073 post-injection time point (6 h, 1 day and 6 days) as the between-group variable. Significant effects were further analysed by Bonferonni post hoc tests.

The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

Materials

The new buprenorphine analogues were synthesized using methods we have reported recently (Cami-Kobeci et al., 2011; Greedy et al., 2013) for other orvinols, but using the appropriate phenethyl magnesium bromide reagent in the Grignard addition step (see Supporting Information Appendix S1). For binding studies, compounds were dissolved in DMSO and diluted into Tris buffer, pH 7.5. For behavioural studies, BU08073 and U50,488 (2-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-N-methyl-N-[(1R,2R)-2-pyrrolidin-1-ylcyclohexyl]acetamide; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were dissolved in 1–2% DMSO and 30% polyethylene glycol 400 solution. Morphine hydrochloride (Eli Lilly & Co., Indianapolis, IN, USA) was dissolved in water. Drugs were injected in a volume of 0.1 mL per 30 g s.c. Controls received 0.1 mL per 30 g of the appropriate vehicle.

Results

In vitro characterization: receptor binding and functional activity

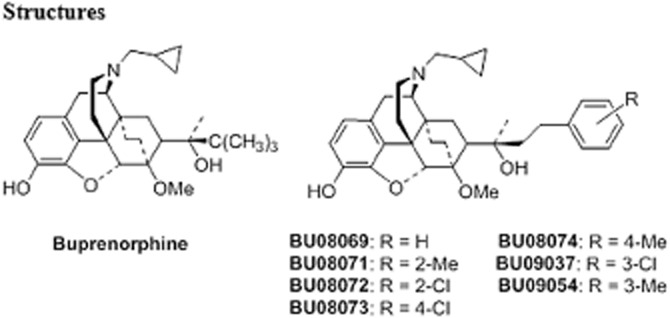

A series of analogues of buprenorphine were designed and constructed for the purpose of increasing affinity at NOP receptors but maintaining affinity at the opioid receptors (Figure 1). Similar to our previously described compound BU08028, several compounds had high affinity, with Ki values of less than 10 nM, at all four opioid receptors (Table 1). The new ligands bound with high affinity to μ, κ and δ receptors with little difference between ligands. Only the somewhat lower affinity of the meta-methyl-substituted analogue, BU09054, at δ receptors fell outside an otherwise narrow range. At NOP receptors, the ligands displayed far higher affinity than buprenorphine, to the extent that a number of compounds had affinity for this receptor almost equivalent to that at the μ, κ and δ receptors. In general a chloro substituent appeared to be better tolerated than a methyl substituent for binding to NOP receptors.

Figure 1.

Structures of buprenorphine and novel compounds tested. Full synthetic details and analysis, including microanalysis are provided in the Supporting Information Appendix S1.

Table 1.

Binding affinities Ki of buprenorphine analogues compared with buprenorphine and other prototypical agonists at NOP and other opioid receptors

| Receptor binding Ki (nM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | μ ± SEM | δ ± SEM | κ ± SEM | NOP ± SEM |

| Buprenorphine | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 6.1 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 1.21 | 77.4 ± 16.1 |

| DAMGO* | 1.59 ± 0.17 | 300 ± 58.6 | 305 ± 46 | >10 000 |

| DPDPE* | 503 ± 10 | 1.24 ± 0.09 | >10 000 | >10 000 |

| U69,593* | >10 000 | >10 000 | 1.6 ± 0.26 | >10 000 |

| N/OFQ | 133 ± 30 | >10 000 | 247 ± 3.4 | 0.08 ± 0.03 |

| BU08069 | 2.31 ± 0.27 | 0.87 ± 0.11 | 1.53 ± 0.23 | 3.47 ± 0.54 |

| BU08071 | 6.60 ± 2.72 | 2.05 ± 0.64 | 4.73 ± 0.78 | 19.8 ± 0.1 |

| BU08072 | 3.91 ± 0.69 | 1.22 ± 0.46 | 4.63 ± 0.80 | 8.54 ± 0.42 |

| BU08073 | 2.26 ± 0.33 | 3.20 ± 0.44 | 2.65 ± 0.87 | 7.60 ± 0.78 |

| BU08074 | 3.90 ± 1.22 | 2.48 ± 0.06 | 2.88 ± 0.86 | 14.2 ± 0.62 |

| BU09037 | 3.99 ± 0.36 | 6.01 ± 2.71 | 0.90 ± 0.35 | 5.38 ± 0.24 |

| BU09054 | 5.70 ± 2.35 | 44.77 ± 14.8 | 6.48 ± 2.96 | 24.7 ± 2.19 |

Data shown are mean ± SEM for at least two experiments conducted in triplicate.

Some of the data for the standard compounds are from (Khroyan et al., 2009).

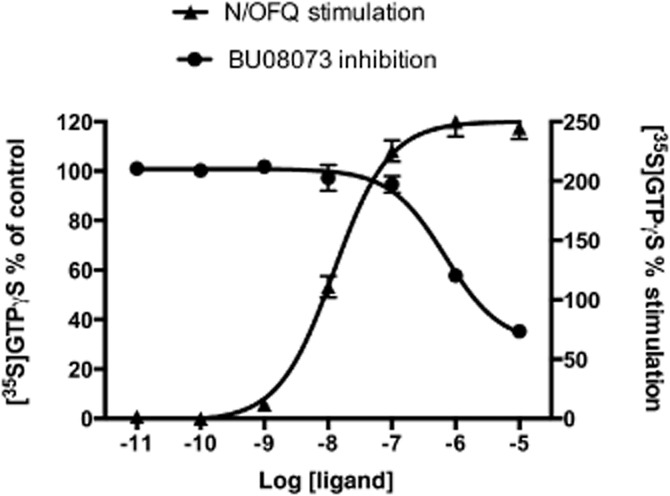

Each compound was tested for functional activity using the [35S]GTPγS binding assay. As seen in Table 2, generally, the compounds have moderate to low partial agonist activity at each receptor. Low partial agonist activity, at the μ receptor, in this assay has been reported for buprenorphine many times, and the even lower agonist activity at NOP receptors is consistent with what we have reported previously (Spagnolo et al., 2008; Khroyan et al., 2009). However, in some publications, the potency of buprenorphine is somewhat higher at μ receptors (Huang et al., 2001) and efficacy considerably higher at NOP receptors (Bloms-Funke et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2001). In this assay, five of the new compounds had efficacy at NOP receptors equivalent to or greater than buprenorphine. The three compounds with the highest efficacies (the unsubstituted and the ortho-substituted analogues) also proved to be more potent than buprenorphine at this receptor, but not to the extent predicted by their binding affinities. At the NOP receptor, an ortho-substituent on the phenyl ring was associated with higher efficacy than a meta-substituent with para-substitution leading to the lowest efficacy. A very similar SAR was seen at the μ receptor with para-substitution again giving the lowest efficacy compound; at δ- and κ receptors, the effect was at its most pronounced. Of the seven new compounds, only the two para-substituted analogues BU08073 and BU08074 had very low, or no efficacy at the κ receptor; each of the other compounds was a partial agonist with substantial (50–60%) efficacy. Because BU08073 had low partial agonist activity at NOP receptors, it was tested for antagonist activity. As seen in Figure 2, BU08073 blocked N/OFQ-induced [35S]GTPγS binding in a concentration-dependent way, with an IC50 of 697 ± 20 nM (Kb = 14.4 nM).

Table 2.

Stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding by buprenorphine analogues, compared with buprenorphine and other prototypical agonists at NOP and other opioid receptors

| μ | δ | κ | NOP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | EC50 | % Stim | EC50 | % Stim | EC50 | % Stim | EC50 | % Stim |

| Buprenorphine | 10.2 ± 2.2 | 28.7 ± 1.0 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 251 ± 94 | 15.5 ± 5.8 | ||

| DAMGO | 35.3 ± 0.53 | 100 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| DPDPE | – | – | 6.86 ± 0.41 | 100 | – | – | – | – |

| U69,593 | – | – | – | – | 78.4 ± 8.8 | 100 | – | – |

| N/OFQ | – | – | – | – | – | – | 8.1 ± 1.38 | 100 |

| BU08069 | 0.60 ± 0.34 | 37.0 ± 0.1 | 3.16 ± 1.68 | 24.8 ± 5.4 | 0.53 ± 0.19 | 52.6 ± 13 | 20.8 ± 4.2 | 24.6 ± 1.9 |

| BU08071 | 4.90 ± 0.01 | 56.3 ± 8.3 | 7.35 ± 0.79 | 37.7 ± 4.9 | 1.35 ± 0.6 | 58.9 ± 2.6 | 66.3 ± 22 | 20.5 ± 2.7 |

| BU08072 | 1.60 ± 0.17 | 58.7 ± 0.4 | 1.78 ± 0.76 | 72.9 ± 13 | 0.77 ± 0.3 | 49.6 ± 16 | 20.8 ± 8.2 | 33.5 ± 3.5 |

| BU08073 | 2.90 ± 0.98 | 31.9 ± 1.0 | * | 9.70 ± 4.8 | * | – | * | 8.2 ± 1.8 |

| BU08074 | * | 10.9 ± 7.4 | * | 4.70 ± 0.2 | * | 9.20 ± 2.7 | * | 6.10 ± 0.75 |

| BU09037 | 9.80 ± 4.54 | 65.2 ± 6.1 | 15.34 ± 0.6 | 58.2 ± 1.2 | 4.13 ± 2.77 | 55.2 ± 7.3 | * | 17.1 ± 1.5 |

| BU09054 | 7.10 ± 0.90 | 38.5 ± 6.6 | 10.29 ± 3.9 | 27.7 ± 4.5 | 146 ± 53 | 50.9 ± 10 | * | 14.9 ± 1.4 |

Data shown are mean ± SEM for at least two experiments conducted in triplicate.

Stimulation was too low to accurately determine EC50 value.

Figure 2.

BU08073 inhibits N/OFQ-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in CHO cells transfected with NOP receptors. Experiments were conducted as described in Materials and Methods. Data in the figure are represented as mean ± SEM for a single representative experiment conducted in triplicate. The EC50 value for stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding by N/OFQ was 12.7 ± 0.56 nM (mean ± SEM from three individual experiments). To test as an antagonist, the BU08073 dose response was conducted in the presence of 100 nM N/OFQ and the IC50 for BU08073 was 697 ± 20 nM (mean ± SEM from three individual experiments).

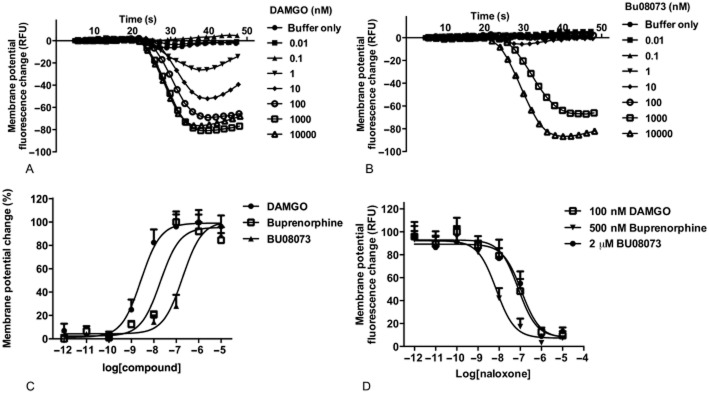

To examine functional activity in an intact cell assay, we measured real-time stimulation of membrane potential using the FlexStation. As seen in Figure 3, DAMGO hyperpolarizes CHO cells transfected with μ receptors (EC50 1.96 ± 0.56 nM), and this is blocked by low concentrations of naloxone. In contrast to the [35S]GTPγS binding assay, both buprenorphine and BU08073 are full agonists in this intact cell assay, with EC50 values of 45.5 ± 19 nM and 323 ± 140 nM, respectively, indicating significant amplification of the signal with this assay.

Figure 3.

The effect of DAMGO, buprenorphine and BU08073 in a whole-cell assay measuring membrane potential changes in CHO cells transfected with μ-opioid receptors. Experiments were conducted using the FlexStation. Data shown in the figure are represented as mean ± SEM from a single representative experiment conducted in quadruplicates. (A) DAMGO-induced membrane potential fluorescence change tracked for 50 s. (B) BU08073-induced membrane potential fluorescence change tracked for 50 s. (C) Agonist dose response curve for each compound. EC50 values were 1.96 ± 0.56, 45.5 ± 19 and 323 ± 140 (mean ± SEM from four individual experiments) for DAMGO, buprenorphine and BU08073 respectively. (D) Antagonist effect of naloxone demonstrating that all compounds are acting through the opioid receptor. IC50 values of naloxone were 63 ± 11, 34 ± 20 and 101 ± 43 140 (mean ± SEM from four individual experiments) when inhibiting 100 nM DAMGO, 500 nM buprenorphine and 2 μM BU08073 respectively.

Behavioural activity

The effects of BU08073 alone on nociception

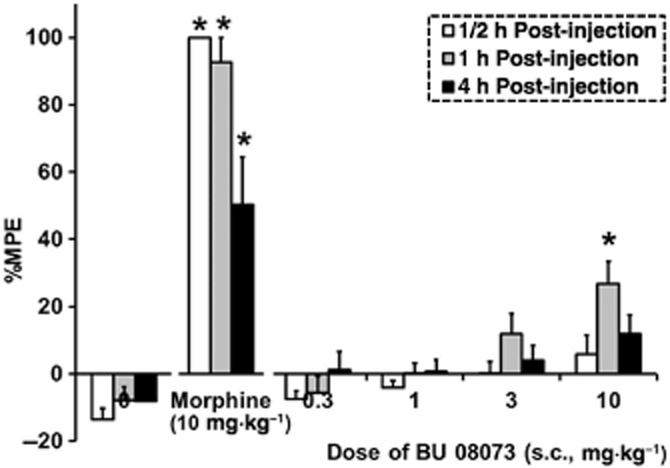

Because of its moderate efficacy at μ receptors in the [35S]GTPγS binding assay and full agonist activity in the whole-cell assay, we tested BU08073 to determine potential antinociceptive activity. The effect of BU08073 on thermal antinociception is shown in Figure 4. The overall anova indicated a significant interaction effect (F10,84 = 4.8, P < 0.05). Morphine produced a significant increase in %MPE relative to vehicle controls at each time points (P < 0.05). However, BU08073 produced a very small but significant increase in %MPE relative to controls that was evident only at the 1 h test point and following administration of the highest dose tested (10 mg·kg−1; P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

The effects of a range of doses of BU08073 on tail-flick latency compared with morphine (10 mg·kg−1) and vehicle controls at various post-injection time points (s.c., n = 6–9 per group). Data are mean %MPE ± SEM. *P < 0.05, significantly different from vehicle controls using repeated anova.

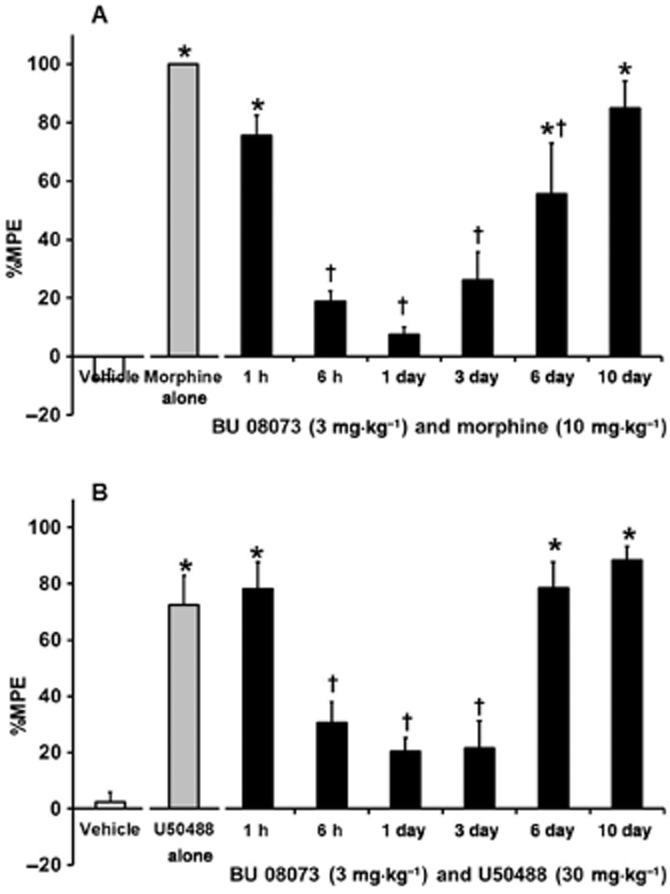

The effects of BU08073 on morphine or U50,488-induced antinociception

Because BU08073 did not produce a high level of antinociception we tested it as an antagonist to morphine antinociception (Figure 5A). The overall anova indicated a significant effect (F7,66 = 17.8, P < 0.05). As expected, 10 mg·kg−1 morphine produced an increase in %MPE 30 min post-injection, relative to vehicle controls (P < 0.05). When 3 mg·kg−1 of BU08073 was administered 30 min prior to morphine and animals were tested 30 min later, morphine antinociception was still evident. However, when BU08073 was given as a 6 h, 1 day and 3 day pretreatment prior to morphine administration, morphine antinociception was blocked and these groups of animals produced a similar level of %MPE as vehicle controls. BU08073 still attenuated morphine antinociception 6 days after a single administration of BU08073, (P < 0.05), although this group also showed a significant increase in %MPE relative to vehicle controls (P < 0.05), indicating μ-receptor inhibition was finally subsiding. By day 10, pretreatment with BU08073 did not alter morphine-induced antinociception and these animals produced a significant increase in %MPE relative to vehicle controls (P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

The effects of 3 mg·kg−1 BU08073 on morphine- (A) and U50,488-induced antinociception (B). All drugs were given via s.c. route of administration. Values on the X-axis indicate time elapsed from the BU 08073 injection. Vehicle, morphine and U50,488 were given 30 min prior to testing. Different groups of animals were used for each BU08073 pretreatment time point (n = 8 per group). Data are mean %MPE ± SEM. *P < 0.05, significantly different from vehicle controls. †significantly different from morphine or U50,488 alone.

BU08073 is devoid of agonist activity at κ-receptors in the [35S]GTPγS binding assay. Experiments were conducted to determine if this compound had long-lasting antagonist activity at κ-receptors as well, by determining the time course for inhibition of U50,488-mediated antinociceptive activity. As seen in Figure 5B, the ability of BU08073 to antagonize U50,488 was quite similar to its ability to antagonize morphine antinociception. The overall anova indicated a significant effect (F7,60 = 21.6, P < 0.05). U50,488 (30 mg·kg−1) alone produced an increase in %MPE 30 min post-injection relative to vehicle controls (P < 0.05). When BU08073 was given 30 min prior to U50,488 and animals were tested 1 h following administration of 3 mg·kg−1 BU08073, U50,488 antinociception was still evident. However, when BU08073 was given as a 6 h, 1 day and 3 day pretreatment prior to U50,488 administration, U50,488-induced antinociception was no longer evident and these groups of animals were significantly different compared with U50,488 alone (P < 0.05) and produced a similar level of %MPE as vehicle controls. By days 6 and 10 after a single treatment with BU08073, the animals produced a significant increase in %MPE relative to vehicle controls (P < 0.05) that were comparable with animals that received U50,488 alone.

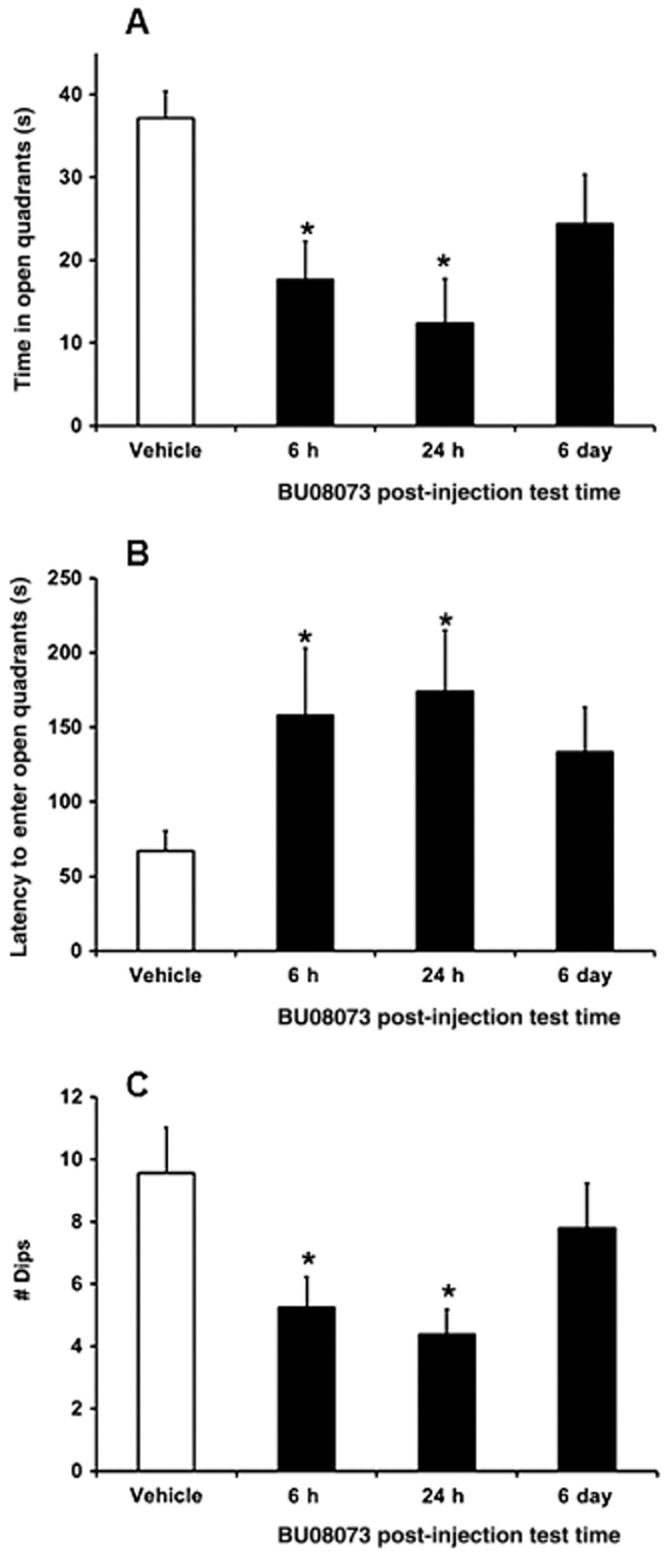

The effects of BU08073 alone on anxiety

The effect of BU08073 on anxiety-related behaviours as captured by zero-maze activity is shown in Figure 6. The overall anova indicated a significant effect looking at all the parameters tested (F3,38 = 6.0, P < 0.05, amount of time spent in the open quadrants; F3,38 = 3.1, P < 0.05, latency to enter the open quadrant; F3,38 = 3.0, P < 0.05, frequency of head dips). Animals that were tested 6 h and 1 day following BU08073 spent less time in the open quadrants, had a greater latency to enter the open quadrants and had a lower incidence of head dips compared with vehicle controls. Animals that received BU08073 and were tested 6 day post-injection were no different than vehicle controls.

Figure 6.

The effects of 3 mg·kg−1 BU08073 (s.c.) on anxiety as measured using the elevated zero maze examining time in the open quadrants (A), latency to enter an open quadrant (B) and number of dips over the side (C). Different groups of animals were used to assess the effects of BU08073 (n = 10 per time point) following different post-injection time points. Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, significantly different from vehicle controls.

In silico pharmacokinetic characterization

BU08073 was examined in silico (ADMET Predictor 6.5, Simulations Plus Inc., Lancaster, CA, USA), along with buprenorphine as a control, to predict its ADMET properties. BU08073 was predicted to be a better substrate than buprenorphine for cytochrome P450-2-C8, a P450 enzyme thought to be responsible for some of the N-dealkylation of buprenorphine to norbuprenorphine. (Picard et al., 2005). However, for buprenorphine, N-dealkylation results in an increase in efficacy as well as limiting access to the brain and this would not explain the lack of efficacy and delayed antagonism displayed by BU08073. No other substantial differences in metabolism were predicted between the two ligands. BU08073 has a higher clogP than buprenorphine, lower water solubility and is predicted to be more highly bound to plasma proteins (Table 3). Since both BU08073 and buprenorphine are predicted to have good blood–brain barrier (BBB) penetration, it is likely that the apparent slow kinetics of BU08073 relate to its high protein binding, resulting in a depot-like effect and slow release of the unbound form.

Table 3.

ADMET predictions for BU08073 compared with parent compound buprenorphine

| logP (simulation plus model) | Intrinsic water solubility (mg·mL−1) | Likelihood of BBB penetration | Log of blood–brain partition coefficient | % Unbound to plasma proteins | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BU08073 | 6 | 7.92E-03 | High | 0.58 | 12.47 |

| Buprenorphine | 4.72 | 5.64E-02 | High | 0.26 | 29.03 |

Discussion

As predicted by our earlier studies in the orvinols (Cami-Kobeci et al., 2011), having a lipophilic group separated from C20 by a short chain results in increased NOP activity compared with buprenorphine, which has the lipophilic t-butyl group attached directly to C20. This also results in higher efficacy at the other opioid receptors, again as would be predicted from earlier work. (Lewis and Husbands, 2004; Greedy et al., 2013). The high affinity of the new ligands at NOP receptors relative to buprenorphine is in agreement with the finding of Yu et al. that TH-030418 (a thienylethyl orvinol analogue) had as high affinity at NOP receptors as at the other opioid receptors (Yu et al., 2011). No indication of the efficacy of this compound at NOP receptors was given. Also, recently reported was the dimethylphenethyl analogue that has similar affinity for NOP receptors as for the other opioid receptors (Cami-Kobeci et al., 2011). In [35S]GTPγS assays, this analogue is a lower efficacy partial agonist at the μ receptor than BU08073 (17% vs. 32%) but is also a partial agonist at each of the other receptors; this is different than BU08073, which is largely devoid of agonist activity at opioid receptors other than μ receptors.

Buprenorphine, which has only approximately 28% maximal activity in the [35S]GTPγS binding assay, as well as other partial μ opioid receptor agonists, have potent antinociceptive activity in rodents and humans. However, efficacy of partial agonists is completely dependent upon the test being administered. This can be demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo. In the present study, we have shown that both buprenorphine and BU0873 are partial agonists at μ receptors in the [35S]GTPγS binding assay while in a whole-cell in vitro assay in which we measured membrane potential changes, both buprenorphine and BU08073 demonstrate full agonist activity. Buprenorphine also has full agonist activity in an intact cell reporter gene assay at NOP receptors (Wnendt et al., 1999) although it is very weak in the [35S]GTPγS binding assay (Spagnolo et al., 2008; Khroyan et al., 2009). Presumably, these differences are due to signal amplification and a high receptor reserve for the intact cells assays. In fact, it is very common that compounds with partial agonist, or even antagonist activity in in vitro assays can have agonist activity when tested in vivo. Buprenorphine provides an example for this phenomenon. Buprenorphine has very low efficacy in the [35S]GTPγS binding assay at NOP receptors (Spagnolo et al., 2008), but has clear agonist activity at NOP receptors when measuring antinociception (Lutfy et al., 2003; Khroyan et al., 2009). As another example, the peptide [Phe1psi(CH2-NH)Gly2]-NC(1-13)-NH2 was described as the first NOP receptor antagonist when tested in the mouse vas deferens assay (Guerrini et al., 1998), while further studies demonstrated that this compound has full agonist activity in transfected cells and is as potent as N/OFQ in blocking opiate analgesia in mice (Calo et al., 1998; Okawa et al., 1999). Due to agonist activity comparable to buprenorphine at μ-receptors in vitro, we expected BU08073 to have antinociceptive activity in vivo. Furthermore, high affinity at NOP receptors, with no apparent efficacy, should act to potentiate the antinociceptive activity of this compound. However, BU08073 displays only very limited antinociception at a single dose and single time point, in the tail flick. Even more surprising was the observation that although BU08073 antagonized both μ and κ receptor-mediated antinociception, antagonist activity of this compound was not evident at 1 h, a time point that is normally associated with maximal activity for many opiates, including its close analogue buprenorphine. BU08073 also has high affinity and antagonist activity at the other receptors in the opiate receptor family. But it seems very unlikely that antagonism of these other receptors would block the expected μ receptor-mediated antinociception.

When the antagonist activity of BU08073 was observed over longer periods of time, it was determined that this compound has antagonist activity at both μ and κ receptors that can last for 6 or more days after a single injection. Long-lasting antagonists are not unknown. β-funaltrexamine (β-FNA) is an opiate that has high affinity for μ, δ and κ receptors and acutely activates κ but inhibits μ and δ receptors (Portoghese et al., 1980). However, β-FNA has a reactive electrophilic functional group (a Michael acceptor) and once bound to the receptor, it forms a covalent bond with the μ receptor and thereby acts as an irreversible (and long lasting) antagonist, at this receptor only (Takemori et al., 1981; Manglik et al., 2012). It is often used as a μ receptor antagonist for in vivo studies since 24 h after administration, it can block μ receptors without inhibiting δ or κ receptors to any significant extent (Liu-Chen et al., 1991).

Several compounds can also antagonize κ receptors for extended periods of time both in vitro and in vivo. Both norbinaltorphimine (nor-BNI) and JDTic ((3R)-7-Hydroxy-N-[(2S)-1-[(3R,4R)-4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-3,4-dimethylpiperidin-1-yl]-3-methylbutan-2-yl]-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxamide) are very high affinity and selective κ receptor antagonists that can block U50,488-mediated antinociception for up to 6 weeks after a single injection (Horan et al., 1992; Jones and Holtzman, 1992; Carroll et al., 2004; Metcalf and Coop, 2005). The mechanism of this extremely long duration of action is not completely clear. These compounds do not bind covalently, so it is not due to functionally removing the receptors. One hypothesis is that these two compounds, and a few other analogues, activate the JNK family of MAPK, leading to prolonged inactivation of κ receptor signalling persisting for weeks after a single exposure (Bruchas et al., 2007; Melief et al., 2010; 2011). Another observation that is not incompatible with the JNK hypothesis is that nor-BNI can be found in the brain of mice, at quantities sufficient to antagonize κ receptors for at least 3 weeks after a single i.p. administration, suggesting that the long-lasting effect of nor-BNI could be simply due to its pharmacokinetic parameters (Patkar et al., 2013).

Similar to nor-BNI and JDTic, BU08073 does not have a reactive functional group and almost certainly does not form a covalent bond with opioid receptors. Unlike both the μ receptor antagonist β-FNA and the κ receptor antagonists nor-BNI and JDTic, the long-lasting antagonist activity of BU08073 has a similar time course for both μ and κ receptors, with antagonist activity most potent at 24 h and decreasing gradually over the next 6–10 days. Most likely, this is a pharmacokinetic phenomenon due to slow entry into the CNS.

Metabolism to an active, but antagonist metabolite, could potentially explain the behavioural results. The metabolism of buprenorphine, which is structurally very closely related, has been well characterized; thus N-dealkylation to give the equivalent nor-compound and glucuronidation at the C3 oxygen of both the parent and the nor-compound (Husbands, 2013). Norbuprenorphine may play a role in the pharmacology of buprenorphine, but its profile is as a high affinity, highly efficacious compound but with very limited access to the brain. Thus metabolism seems an unlikely explanation for the unusual profile of BU08073, although it cannot be ruled out completely.

Slow kinetics could account for the lack of effect of the compound 1 h after administration. What is unclear is how kinetics can affect the efficacy of the compound in vivo. In vitro, BU08073 has clear partial agonist activity in [35S]GTPγS binding and greater agonist activity in an intact cell assay. Perhaps the slow increase in receptor occupation leads to desensitization prior to generation of a significant antinociceptive signal. Another possibility that may contribute to the actions of this drug is its binding sensitivity to pH. If dissociation is much more rapid at low pH, perhaps the receptor and ligand are internalized but not recycled appropriately. This would reduce receptor availability and thereby functionally antagonize agonist activity at the receptors. Alternately, it could be a function of some ligand directed signalling. It has been hypothesized that biased agonists at the μ receptor could have antinociceptive activity without some of the unwanted side effects (Law et al., 2013). This could work the other direction as well. Perhaps the BU08073/μ receptor interaction does not activate an underlying pathway required for the expression of antinociception.

BU08073 also has long-lasting anxiogenic activity. This is different than the reported anxiolytic activity of systemically or locally administered morphine (Anseloni et al., 1999; Zhang and Schulteis, 2008) but consistent with the reported anxiogenic activity of buprenorphine (Lelong-Boulouard et al., 2006). The reason why buprenorphine and BU08073 would have different effects on anxiety behaviour than morphine is not clear. Morphine is quite selective for the μ receptor, so anxiogenic activity of buprenorphine and BU08073 might have to do with agonist or antagonist activity at one of the other opioid receptors or NOP. Since the κ receptor agonist U50488 has anxiogenic activity and these compounds are antagonists at κ receptors, it seems unlikely that the anxiogenic activity of BU08073 is due to κ receptor inhibition. However, several δ receptor agonists have been demonstrated to have anxiolytic activity, so it is possible that δ receptor antagonism could lead to the observed anxiogenic activity (Saitoh et al., 2004; Perrine et al., 2006; Vergura et al., 2008).

In conclusion, BU08073 is a buprenorphine analogue with high affinity at each of the receptors in the opioid receptor family. Although it has moderate efficacy at μ receptors, this compound displays very weak antinociceptive activity, and instead exhibits a rather delayed and long-lasting antagonism to both μ and κ receptor-mediated antinociceptive activity. This unusual property is probably due to very delayed pharmacokinetics. Studies are continuing to determine how pharmacokinetics can modulate opioid receptor mediated actions in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Simulations Plus Inc. for an evaluation license of the ADMET Predictor software. The work was supported by NIH grant DA023281 to L. T. and DA20469 to S. M. H.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- β-FNA

β-funaltrexamine

- DAMGO

[D-Ala2, N-MePhe4, Gly-ol]-enkephalin)

- DPDPE

[D-Pen2,D-Pen5]Enkephalin)

- JDTic

(3R)-7-Hydroxy-N-[(2S)-1-[(3R,4R)-4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-3,4-dimethylpiperidin-1-yl]-3-methylbutan-2-yl]-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxamide

- N/OFQ

nociceptin/orphanin FQ

- NOP

receptor, nociceptin opioid receptor

- U50,488

2-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-N-methyl-N-[(1R,2R)-2-pyrrolidin-1-ylcyclohexyl]acetamide

- U69,593

N-methyl-2-phenyl-N-[(5R,7S,8S)-7-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)-1-oxaspiro[4.5]dec-8-yl]acetamide

Author contributions

Khroyan, Wu, Polgar and Fotaki conducted in vitro, in vivo or in silico experiments.

Cami-Kobeci and Husbands provided materials. Khroyan, Wu, Husbands and Toll contributed to writing the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.12796

Appendix S1 Full synthetic details and analysis, including microanalysis.

References

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: G Protein-Coupled Receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1459–1581. doi: 10.1111/bph.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anseloni VC, Coimbra NC, Morato S, Brandao ML. A comparative study of the effects of morphine in the dorsal periaqueductal gray and nucleus accumbens of rats submitted to the elevated plus-maze test. Exp Brain Res. 1999;129:260–268. doi: 10.1007/s002210050896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloms-Funke P, Gillen C, Schuettler AJ, Wnendt S. Agonistic effects of the opioid buprenorphine on the nociceptin/OFQ receptor. Peptides. 2000;21:1141–1146. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00252-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun AA, Skelton MR, Vorhees CV, Williams MT. Comparison of the elevated plus and elevated zero mazes in treated and untreated male Sprague-Dawley rats: effects of anxiolytic and anxiogenic agents. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;97:406–415. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruchas MR, Yang T, Schreiber S, Defino M, Kwan SC, Li S, et al. Long-acting kappa opioid antagonists disrupt receptor signaling and produce noncompetitive effects by activating c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29803–29811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705540200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calo G, Rizzi A, Marzola G, Guerrini R, Salvadori S, Beani L, et al. Pharmacological characterization of the nociceptin receptor mediating hyperalgesia in the mouse tail withdrawal assay. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;125:373–378. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cami-Kobeci G, Polgar WE, Khroyan TV, Toll L, Husbands SM. Structural determinants of opioid and NOP receptor activity in derivatives of buprenorphine. J Med Chem. 2011;54:6531–6537. doi: 10.1021/jm2003238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll I, Thomas JB, Dykstra LA, Granger AL, Allen RM, Howard JL, et al. Pharmacological properties of JDTic: a novel kappa-opioid receptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;501:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccocioppo R, Economidou D, Fedeli A, Angeletti S, Weiss F, Heilig M, et al. Attenuation of ethanol self-administration and of conditioned reinstatement of alcohol-seeking behaviour by the antiopioid peptide nociceptin/orphanin FQ in alcohol-preferring rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;172:170–178. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1645-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccocioppo R, Economidou D, Rimondini R, Sommer W, Massi M, Heilig M. Buprenorphine reduces alcohol drinking through activation of the nociceptin/orphanin FQ-NOP receptor system. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan A, Lewis JW, Macfarlane IR. Agonist and antagonist properties of buprenorphine, a new antinociceptive agent. Br J Pharmacol. 1977;60:537–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1977.tb07532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox BM, Christie MJ, Devi L, Toll L, Traynor JR. Challenges for opioid receptor nomenclature: IUPHAR Review 9. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:317–323. doi: 10.1111/bph.12612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan A, Yassen A, Bijl H, Romberg R, Sarton E, Teppema L, et al. Comparison of the respiratory effects of intravenous buprenorphine and fentanyl in humans and rats. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94:825–834. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley CT, Spaeth CG, Berzetei-Gurske IP, Craymer K, Adapa ID, Brandt SR, et al. Binding and in vitro activities of peptides with high affinity for the nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor, ORL1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:735–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greedy BM, Bradbury F, Thomas MP, Grivas K, Cami-Kobeci G, Archambeau A, et al. Orvinols with mixed kappa/mu opioid receptor agonist activity. J Med Chem. 2013;56:3207–3216. doi: 10.1021/jm301543e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini R, Calo G, Rizzi A, Bigoni R, Bianchi C, Salvadori S, et al. A new selective antagonist of the nociceptin receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123:163–165. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan P, Taylor J, Yamamura HI, Porreca F. Extremely long-lasting antagonistic actions of nor-binaltorphimine (nor-BNI) in the mouse tail-flick test. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;260:1237–1243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Kehner GB, Cowan A, Liu-Chen LY. Comparison of pharmacological activities of buprenorphine and norbuprenorphine: norbuprenorphine is a potent opioid agonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;297:688–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husbands SM. Buprenorphine and related orvinols. In: Ko MCH, Husbands SM, editors. Research and Development of Opioid-Related Analgesics. Vol. 1131. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society Symposium Series; 2013. pp. 127–144. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DN, Holtzman SG. Long term kappa-opioid receptor blockade following nor-binaltorphimine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;215:345–348. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khroyan TV, Polgar WE, Jiang F, Zaveri NT, Toll L. Nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor activation attenuates antinociception induced by mixed nociceptin/orphanin FQ/mu-opioid receptor agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:946–953. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.156711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khroyan TV, Polgar WE, Cami-Kobeci G, Husbands SM, Zaveri NT, Toll L. The first universal opioid ligand, (2S)-2-[(5R,6R,7R,14S)-N-cyclopropylmethyl-4,5-epoxy-6,14-ethano-3-hydroxy -6-methoxymorphinan-7-yl]-3,3-dimethylpentan-2-ol (BU08028): characterization of the in vitro profile and in vivo behavioral effects in mouse models of acute pain and cocaine-induced reward. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;336:952–961. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.175620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khroyan TV, Zhang J, Yang L, Zou B, Xie J, Pascual C, et al. Rodent motor and neuropsychological behavior measured in home cages using the integrated modular platform – SmartCage(TM) Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2012;39:614–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2012.05719.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Animal research: Reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapman A, Abogadie F, McIntrye P, Connor M. A real-time, fluorescence-based assay for measuring mu-opioid receptor modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biomol Screen. 2014;19:223–231. doi: 10.1177/1087057113501391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotlinska J, Rafalski P, Biala G, Dylag T, Rolka K, Silberring J. Nociceptin inhibits acquisition of amphetamine-induced place preference and sensitization to stereotypy in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;474:233–239. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)02081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law PY, Reggio PH, Loh HH. Opioid receptors: toward separation of analgesic from undesirable effects. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelong-Boulouard V, Quentin T, Moreaux F, Debruyne D, Boulouard M, Coquerel A. Interactions of buprenorphine and dipotassium clorazepate on anxiety and memory functions in the mouse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;85:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JW, Husbands SM. The orvinols and related opioids – high affinity ligands with diverse efficacy profiles. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:717–732. doi: 10.2174/1381612043453027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu-Chen LY, Li SX, Wheeler-Aceto H, Cowan A. Effects of intracerebroventricular beta-funaltrexamine on mu and delta opioid receptors in the rat: dichotomy between binding and antinociception. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;203:195–202. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90715-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutfy K, Cowan A. Buprenorphine: a unique drug with complex pharmacology. Cur Neuropharmacol. 2004;2:395–402. doi: 10.2174/1570159043359477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutfy K, Eitan S, Bryant CD, Yang YC, Saliminejad N, Walwyn W, et al. Buprenorphine-induced antinociception is mediated by mu-opioid receptors and compromised by concomitant activation of opioid receptor-like receptors. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10331–10337. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-32-10331.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manglik A, Kruse AC, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Mathiesen JM, Sunahara RK, et al. Crystal structure of the micro-opioid receptor bound to a morphinan antagonist. Nature. 2012;485:321–326. doi: 10.1038/nature10954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WR. Pharmacology of opioids. Pharmacol Rev. 1983;35:283–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WR, Eades CG, Thompson JA, Huppler RE, Gilbert PE. The effects of morphine- and nalorphine- like drugs in the nondependent and morphine-dependent chronic spinal dog. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1976;197:517–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, McLachlan E, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melief EJ, Miyatake M, Bruchas MR, Chavkin C. Ligand-directed c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation disrupts opioid receptor signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11608–11613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000751107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melief EJ, Miyatake M, Carroll FI, Beguin C, Carlezon WA, Jr, Cohen BM, et al. Duration of action of a broad range of selective kappa-opioid receptor antagonists is positively correlated with c-Jun N-terminal kinase-1 activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;80:920–929. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.074195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Mendelson JH, Bree MP, Lukas SE. Buprenorphine suppresses cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys. NIDA Res Monogr. 1989;95:333–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Mendelson JH, Lukas SE, Gastfriend DR, Teoh SK, Holman BL. Buprenorphine treatment of opiate and cocaine abuse: clinical and preclinical studies. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1993;1:168–183. doi: 10.3109/10673229309017075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf MD, Coop A. Kappa opioid antagonists: past successes and future prospects. AAPS J. 2005;7:E704–E722. doi: 10.1208/aapsj070371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya ID, Gorelick DA, Preston KL, Schroeder JR, Umbricht A, Cheskin LJ, et al. Randomized trial of buprenorphine for treatment of concurrent opiate and cocaine dependence. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;75:34–48. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (US) Committee on Guidelines for the Use of Animals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research. Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okawa H, Nicol B, Bigoni R, Hirst RA, Calo G, Guerrini R, et al. Comparison of the effects of [Phe1psi(CH2-NH)Gly2]nociceptin(1-13)NH2 in rat brain, rat vas deferens and CHO cells expressing recombinant human nociceptin receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:123–130. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patkar KA, Wu J, Ganno ML, Singh HD, Ross NC, Rasakham K, et al. Physical presence of nor-binaltorphimine in mouse brain over 21 days after a single administration corresponds to its long-lasting antagonistic effect on kappa-opioid receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;346:545–554. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.206086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, et al. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert-driven knowledge base of drug targets and their ligands. Nucleic Acids Research. 2014;42(Database Issue):D1098–D1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrine SA, Hoshaw BA, Unterwald EM. Delta opioid receptor ligands modulate anxiety-like behaviors in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:864–872. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard N, Cresteil T, Djebli N, Marquet P. In vitro metabolism study of buprenorphine: evidence for new metabolic pathways. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:689–695. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.003681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portoghese PS, Larson DL, Sayre LM, Fries DS, Takemori AE. A novel opioid receptor site directed alkylating agent with irreversible narcotic antagonistic and reversible agonistic activities. J Med Chem. 1980;23:233–234. doi: 10.1021/jm00177a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh A, Kimura Y, Suzuki T, Kawai K, Nagase H, Kamei J. Potential anxiolytic and antidepressant-like activities of SNC80, a selective delta-opioid agonist, in behavioral models in rodents. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;95:374–380. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fpj04014x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakoori K, Murphy NP. Central administration of nociceptin/orphanin FQ blocks the acquisition of conditioned place preference to morphine and cocaine, but not conditioned place aversion to naloxone in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;172:129–136. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1643-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd JK, Grewal SS, Fletcher A, Bill DJ, Dourish CT. Behavioural and pharmacological characterisation of the elevated ‘zero-maze’ as an animal model of anxiety. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;116:56–64. doi: 10.1007/BF02244871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoblock JR, Wichmann J, Maidment NT. The effect of a systemically active ORL-1 agonist, Ro 64-6198, on the acquisition, expression, extinction, and reinstatement of morphine conditioned place preference. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spagnolo B, Carra G, Fantin M, Fischetti C, Hebbes C, McDonald J, et al. Pharmacological characterization of the nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor antagonist SB-612111 [(-)-cis-1-methyl-7-[[4-(2,6-dichlorophenyl)piperidin-1-yl]methyl]-6,7,8,9 -tetrahydro-5H-benzocyclohepten-5-ol]: in vitro studies. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:961–967. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.116764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spagnolo B, Calo G, Polgar WE, Jiang F, Olsen CM, Berzetei-Gurske I, et al. Activities of mixed NOP and mu-opioid receptor ligands. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:609–619. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemori AE, Larson DL, Portoghese PS. The irreversible narcotic antagonistic and reversible agonistic properties of the fumaramate methyl ester derivative of naltrexone. Eur J Pharmacol. 1981;70:445–451. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(81)90355-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toll L, Berzetei-Gurske IP, Polgar WE, Brandt SR, Adapa ID, Rodriguez L, et al. Standard binding and functional assays related to medications development division testing for potential cocaine and opiate narcotic treatment medications. NIDA Res Monogr. 1998;178:440–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynor JR, Nahorski SR. Modulation by mu-opioid agonists of guanosine-5′-O-(3-[35S]thio)triphosphate binding to membranes from human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;47:848–854. doi: 10.1016/S0026-895X(25)08634-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergura R, Balboni G, Spagnolo B, Gavioli E, Lambert DG, McDonald J, et al. Anxiolytic- and antidepressant-like activities of H-Dmt-Tic-NH-CH(CH2-COOH)-Bid (UFP-512), a novel selective delta opioid receptor agonist. Peptides. 2008;29:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wnendt S, Kruger T, Janocha E, Hildebrandt D, Englberger W. Agonistic effect of buprenorphine in a nociceptin/OFQ receptor-triggered reporter gene assay. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;56:334–338. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.2.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G, Yan LD, Li YL, Wen Q, Dong HJ, Gong ZH. TH-030418: a potent long-acting opioid analgesic with low dependence liability. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2011;384:125–131. doi: 10.1007/s00210-011-0652-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Schulteis G. Withdrawal from acute morphine dependence is accompanied by increased anxiety-like behavior in the elevated plus maze. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;89:392–403. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 Full synthetic details and analysis, including microanalysis.