Abstract

Background

To understand the mechanism of frequent and early lymph node metastasis in high risk human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC), we investigated whether β-catenin is regulated by HPV oncoprotein and contributes to OPSCC metastasis.

Methods

Expression levels of p16, β-catenin, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) were examined in OPSCC samples (n=208) by immunohistochemistry. Expression and subcellular localization of β-catenin and EGFR activation were also studied in HPV-positive and -negative head and neck SCC cell lines by Western blot analysis. HPV16 E6 siRNA was used to elucidate the effect of HPV oncoprotein on β-catenin translocation. The involvement of EGFR in β-catenin translocation was confirmed by treatment with erlotinib. Moreover, the invasive capacity was evaluated after HPV16 E6/E7 repression.

Results

Our results showed that membrane weighted index (WI) of β-catenin was inversely correlated with p16 positivity (p<0.001) and lymph node metastasis (p=0.026), while nuclear staining of β-catenin was associated with p16-positive OPSCC (p<0.001). A low level of membrane β-catenin expression was significantly associated with disease free and overall survival (p<0.0001 in both cases). Furthermore, the membrane WI of EGFR was inversely correlated with p16 positivity (p<0.001) and positively correlated with membrane β-catenin (p<0.001). Our in vitro study showed that HPV16 E6 repression led to reductions of phosphoEGFR, and nuclear β-catenin, which were also observed after erlotinib treatment, and inhibition of invasion.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that HPV16 E6 mediates the translocation of β-catenin to the nucleus, which may be regulated by activated EGFR.

Keywords: HPV, oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, β-catenin, EGFR, lymph node metastasis

Background

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the sixth most common malignancy worldwide1. In recent years, the prevalence of high risk human papillomavirus (HPV) in OPSCC cases has significantly increased, from 16.3% during 1984-1989 to 71.7% during 2000-2004 in the USA2. It is clear that OPSCC can be classified as two groups: HPV-positive and HPV-negative cancers. HPV-negative cases are associated with heavy consumption of alcohol and/or tobacco, whereas HPV-positive cancers have risk factors related to sexual behavior2-6. The molecular events in HPV-induced carcinogenesis have been extensively studied in cervical cancer, however, remain to be elucidated in OPSCC.

β-catenin acts as the central component in the canonical Wnt pathway which is involved in a variety of biological activities, including cell proliferation, differentiation, invasion, and metastasis7-9. β-catenin can be translocated from the membrane to the cytoplasm and then enter the nucleus. Its translocation can be induced by many protein factors, including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)10, 11. Nuclear β-catenin then binds to T-cell factor (TCF) family members, leading to activation of the transcription of target genes. Reduced assembly of membranous β-catenin and its nuclear translocation was found to occur frequently in invasive areas and metastases of OPSCC12. Although nuclear translocation of β-catenin was detected in the primary tumor of HPV-driven tonsillar cancer13, it remains unclear whether β-catenin plays important roles in the carcinogenesis and progression of HPV-positive OPSCC. Moreover, how the HPV oncoproteins E6 and E7 regulate β-catenin activity has not been completely elucidated.

In the present study, we examined the expression of β-catenin and EGFR in OPSCC and sought to determine whether β-catenin translocation is involved in HPV-related OPSCC. Furthermore, we explored whether HPV oncoprotein regulates the translocation of β-catenin via EGFR activation in HPV-positive cancer cells.

Methods

OPSCC tissue samples

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Emory University. All of the clinical data analyses were conducted using de-identified records in compliance with HIPAA. Patients’ tissues (n= 208) for this study were obtained from the surgical specimens of patients who were diagnosed with OPSCC at the Emory University Hospital and had no prior treatment with radiation and/or chemotherapy. Tissues from the primary tumor were used in the study.Patients’ general characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Univariate association of p16 status with covariates

| p16 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Level | Negative N=70 | Positive N=138 | P-value* |

| Gender | Male (%) | 44 (27.67) | 115 (72.33) | 0.001 |

| Female (%) | 26 (53.06) | 23 (46.94) | ||

| Age | Median (Range) | 63.5 (40 -90) | 53 (32 -89) | <.001 |

| Race | African American (%) | 15 (75) | 5 (25) | <.001 |

| White (%) | 44 (28.39) | 111 (71.61) | ||

| Hispanic (%) | 1 (33.33) | 2 (66.67) | ||

| Smoking | Never (%) | 1 (3.03) | 32 (96.97) | <.001 |

| Former (%) | 19 (24.05) | 60 (75.95) | ||

| Current (%) | 46 (54.12) | 39 (45.88) | ||

| Differentiation Status | Well differentiated (%) | 9 (60) | 6 (40) | 0.005 |

| Moderately differentiated (%) | 31 (41.89) | 43 (58.11) | ||

| Nonkeratinized (%) | 30 (25.42) | 88 (74.58) | ||

| Tumor Stage | T1 (%) | 20 (29.41) | 48 (70.59) | 0.525 |

| T2 (%) | 25 (32.89) | 51 (67.11) | ||

| T3 (%) | 7 (46.67) | 8 (53.33) | ||

| T4 (%) | 12 (40) | 18 (60) | ||

| Node Metastasis | Negative (%) | 24 (61.54) | 15 (38.46) | <.001 |

| Positive (%) | 41 (26.8) | 112 (73.2) | ||

| Stage | I (%) | 9 (69.23) | 4 (30.77) | 0.008 |

| II (%) | 13 (46.43) | 15 (53.57) | ||

| III (%) | 5 (27.78) | 13 (72.22) | ||

| IV (%) | 38 (27.94) | 98 (72.06) | ||

| Nuclear β-catenin | Negative (%) | 40 (45.45) | 48 (54.55) | 0.002 |

| Positive (%) | 30 (25) | 90 (75) | ||

| Membranous β-catenin | Median (Range) | 126 (0 -240) | 32.5 (0 -253) | <.001 |

| Cytoplasmic EGFR | Median (Range) | 200(40 -300) | 200 (0 -300) | 0.442 |

| Membranous EGFR | Median (Range) | 140(0 -285) | 50 (0 -300) | <0.001 |

P-value is calculated by Wilcoxon rank-sum test for age, membranous β-catenin, cytoplasmic EGFR, and membranous EGFR; Fisher's exact test for race; chi-square test for the remaining categorical covariates.

Cell lines, cell culture and treatment

The HNSCC cell lines SCC2, SCC47, UM22B, and JHU012 were kindly provided by Dr. Thomas Carey (University of Michigan), and PCI15A, PCI13, and SCC090 by Drs. Robert Ferris and Susanne Gollin (University of Pittsburgh)14. The cervical cancer cell line CaSki was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. Most of the cell lines were maintained as a monolayer culture in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/F12 medium (1:1) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). SCC090 cells were maintained in MEM medium15, and UM22B and CaSki cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS. Genotyping of HNSCC cell lines has been completed either as described by Zhao et al14 or in our lab. The human origins of the cell lines have been confirmed (data not shown). One μM erlotinib was used to inhibit the activation of EGFR.

siRNA transfection

HPV16 E6 siRNA (Santa Cruz, CA) was mixed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions and applied to each plate (cells at 30%–50% confluence). Transfection medium was removed and replaced with complete medium after 5 hrs of incubation.

Western blot analysis

Cells were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) before being lysed on ice for 40 minutes with lysis buffer containing 50 mmol/L HEPES buffer, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA (pH 8.0), 1 mmol/L EGTA (pH 8.0), 1% IGEPAL CA-630, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10 mmol/L NaF, 2 mmol/L Na3VO4, 10 mmol/L β-glycerophosphate, and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The lysate was centrifuged at 16,000 × g at 4°C for 10 minutes. Ten to fifty micrograms of total protein for each sample were separated by 8%~12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto an Immobilon membrane (Millipore Inc, Billerica, MA.), and the desired proteins were probed with corresponding antibodies. Mouse anti-HPV16 E7 (1:1000 dilution) and anti-total EGFR (1:1000) were purchased from Santa Cruz, mouse anti-human actin (1:10000 dilution) from Sigma, anti-β catenin antibody from BD Pharmingen (San Jose, CA), and anti-phospho EGFR (tyrosine 1173) antibody from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Horseradish peroxidase– conjugated secondary anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) were obtained from Promega. Bound antibody was detected using the SuperSignal West Pico Chemoluminescence system (Pierce, Inc. Rockford, IL).

Matrigel invasion assay

The matrigel invasion assay was performed with the matrigel basement membrane matrix according to the manufacturer's protocol (Becton Dickinson Biosciences Discovery Labware) as described in our previous publication16. Briefly, 3 × 104 cells in 0.5 mL of serum-free medium were seeded in the invasion chamber containing the matrigel membrane (27.2 ng per chamber) in triplicate and allowed to settle for 2 hours at 37°C. Ten percent FBS medium was added as a chemoattractant in the lower compartment of the invasion chamber. The chambers were incubated for 36 hours at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The invading cells appeared at the lower surface of the membrane. The upper surface of the membrane was swiped with a cotton swab. After the cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet, the membrane was placed on a microscope slide with the bottom side up and covered with immersion oil and a cover slip. Cells were counted under a microscope as a sum of 10 high-power fields that were distributed randomly on the central and peripheral membrane. The experiment was repeated 3 times.

qRT-PCR

Total cellular RNA was collected using Trizol according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Two μg RNA were reverse-transcribed using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase. Two μl of the produced cDNA was used for triplicate subgreen real time-PCR according to the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems). HPV16 E6 primers were described by Cattani et al17, as HPV 16 E6 forward primer: 5’GCACCAAAAGAGAACTGCAATGTT3’ and HPV 16 E6 reverse primer: 5’AGTCATA TACCTCACGTCGCAGTA3’. HPV16 E6 mRNA levels were normalized to GAPDH levels. The amplification profile consisted of 3 min at 95°C for denaturation, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation (94°C 30 s), annealing (60°C 40 s), and extension (72°C for 40 s).

Immunohistochemistry and scoring

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were used for IHC, as described previously16. In brief, the slides were incubated with primary antibody against p16 (1:100 dilution, Delta Biolab, Gilroy, CA), and β-catenin (1:100 dilution, BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA). The available tissue was also subjected to EGFR immunostaining (1:100 dilution, Biogenex). Antibody staining was observed by diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride peroxidase substrate solution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Cell nuclei were counterstained by hematoxylin QS (Vector Laboratories). Immunoglobulin G (IgG) was used as a negative control. Membrane expression of β-catenin and the levels of total and cytoplasmic EGFR were scored separately as a weighted index [WI = intensity (0, 1+, 2+, and 3+) x % of positive staining]. The expression of β-catenin in normal epithelium was scored as: strong positive (3+), weak or moderate but clear β-catenin staining (1+ and 2+, respectively) (Fig. 1A). The scoring categories for EGFR were described in our previous publication18. Two surgical pathologists (Drs. Müller and Hu) evaluated the immunostained slides independently. Nuclear β-catenin and p16 were recorded as positive or negative. Positive p16 nuclear and/or cytoplasmic staining in more than 70% cancer cells was defined as p16 positive.

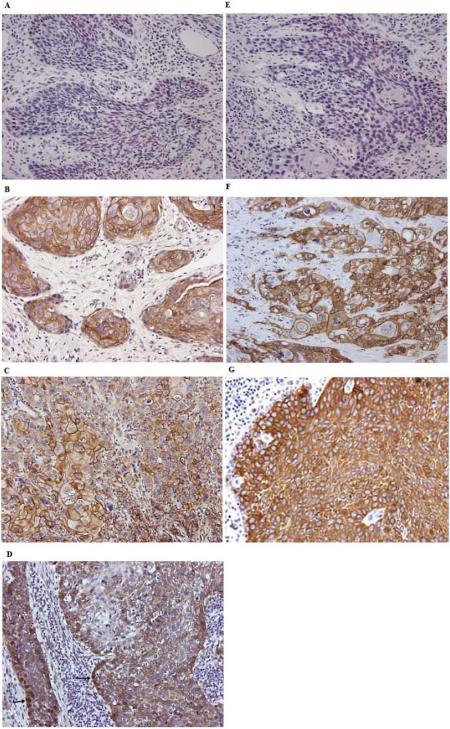

Figure 1.

Expression pattern of β-catenin and EGFR in OPSCC. (A) and (E) show the negative controls for β-catenin and EGFR staining, respectively. β-catenin is localized in the membrane (B), cytoplasm (C) and nucleus (D) as indicated by arrows, while EGFR is expressed in the membrane (F) and cytoplasm (G). Magnification: ×200.

Immunofluorescence

Fluorescence analysis was performed using a BX51 Olympus microscope on cultures fixed for 20 min at room temperature in 4% paraformaldehyde (Polysciences Inc). Primary antibody against β-catenin was incubated overnight at 4°C. Secondary antibodies were labeled with Alexa 488. 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining served to counterstain cell nuclei. Cells stained with only secondary antibody were used as negative controls. Optical density was analyzed by Inform 1.4 (Caliper Life Science Company).

Statistical analyses

Patient characteristics were summarized and compared between patients with p16 positive and p16 negative tumors. Age was presented as a median (range) and compared using Wilcoxon's rank sum test. Other variables, such as sex, smoking history, site, tumor (T), stage, and differentiation level (well differentiated, moderately differentiated, nonkeratinizing) were treated as categorical variables and compared with χ2 test or Fisher's exact test, where appropriate.

Overall survival (OS) was calculated as the time from the date of diagnosis to death or last patient contact. Disease free survival (DFS) was calculated as the time from the date of diagnosis to the date of disease progression, death, or last contact, whichever was earliest. Biomarkers were further dichotomized by the optimal cut-off point (high: >= cut-off point vs. low: < cut-off point), which corresponded to the most significant relationship with OS or DFS based on the log-rank statistic19. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates were calculated for each group of the patients stratified based on the optimal cut-off point along with a log-rank test20. A Cox proportional hazards model21 was also used to estimate the adjusted effect of β catenin on DFS or OS after adjustment for gender, age, race, grade, tumor stage, node metastasis, and p16 using a backward variable selection method with an alpha level of removal of 0.1. The SAS 9.3 statistical package (SAS Institute, Inc.) was used for all data management and analyses.

Results

β-catenin and EGFR expression in p16-positive and -negative OPSCC and their association with clinical-pathological features

As shown in Table 1, there was a significant association between p16 status and gender (p=0.001), race (p < 0.001), age (p < 0.001), differentiation status (p=0.005), stage (p = 0.008), and lymph node metastasis (p < 0.001); although p16 was not significantly associated with T-stage (p =0.525). Among 208 cases, 100 OPSCC tissues were confirmed for HPV status by HPV in situ hybridization22. Consistent with the literature, the correlation between positive HPV status and p16 expression was significant in these OPSCC cases (Table S1, P<0.001).

In p16-negative OPSCCs, β-catenin was mainly localized at the cell membrane (Fig. 1B). However, in p16-positive OPSCC, β-catenin levels were decreased at the membrane and in some cases, showed positivity in the nucleus (Fig. 1C and 1D). The WI of β-catenin at the membrane in p16-positive OPSCC was lower than that in p16-negative OPSCC (p<0.001) (Table 1). Compared to their HPV-negative counterparts, HPV-positive OPSCC also showed a lower WI of membranous β-catenin (p<0.001, data not shown). Positive β-catenin nuclear staining was higher in p16-positive OPSCC (65.22%) than in p16-negative OPSCC (42.86%) (p=0.002). Furthermore, membrane WI of β-catenin was inversely correlated with positive lymph nodes (p=0.026) (Table 2). Thus in p16-positive OPSCC, the expression of membrane β-catenin was distinctly decreased, accompanied by increasing nuclear translocation. The decreased expression of β-catenin at the membrane and the accumulation of nuclear β-catenin indicate the relocalization of β-catenin in p16-positive OPSCC.

Table 2.

Univariate association of node status with covariates

| Node Metastasis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Level | Negative N=39 | Positive N=153 | P-value* |

| Nuclear β-catenin | Negative | 21 (26.58) | 58 (73.42) | 0.071 |

| Positive | 18 (15.93) | 95 (84.07) | ||

| Membranous β-catenin | Median (Range) | 71 (0 -240) | 46 (0 -253) | 0.026 |

| Cytoplasmic EGFR | Median (Range) | 200 (90 -300) | 200 (0 -300) | 0.172 |

| Membranous EGFR | Median (Range) | 120 (0 -285) | 60(0 -300) | 0.141 |

P-value is calculated by Wilcoxon rank-sum test for membranous β-catenin, cytoplasmic EGFR, and membranous EGFR; chi-square test for nuclear β-catenin.

EGFR was mainly expressed in the cytoplasm of OPSCC cancer cells and only a small proportion of cancer cells showed membrane expression (Fig 1F and 1G). EGFR membrane staining was more common in keratinizing than in non-keratinizing cancer (Fig 1F and 1G). There was no significant association between p16 and the cytoplasmic level of EGFR (p=0.442). However there was a significant association between p16 and membrane EGFR (p<0.001) (Table 1). Patients with p16-positive OPSCCs had lower levels of membrane EGFR than those with p16-negative OPSCC. We also observed a positive correlation between the levels of membrane EGFR and membrane β-catenin (r=0.350, p<0.001).

Prognostic values of β-catenin and EGFR for OPSCC patients

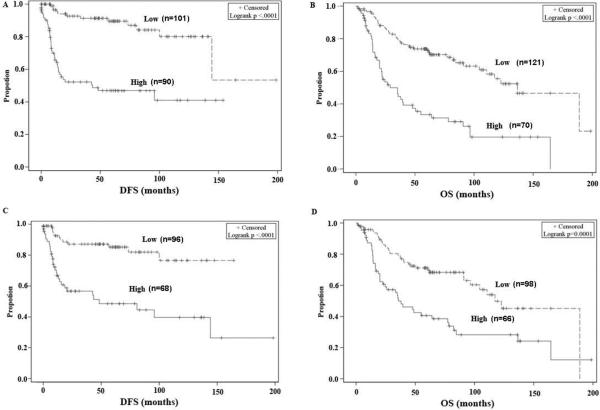

In all patients, a low level of membrane β-catenin was significantly associated with DFS and OS (Fig. 2A and 2B, p<0.0001 in both cases). Low expression of membrane EGFR was also significantly associated with DFS and OS in all patients (Fig. 2C and 2D, p<0.0001 and p=0.0001, respectively). Similarly, in the p16-positive group, low levels of both membrane β-catenin (Fig. S1A and S1B, p<0.0001 and p=0.001, respectively) and membrane EGFR (Fig. S1C and S1D, p=0.0002 and p=0.0248, respectively) were associated with more favorable DFS and OS.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier plot for disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) according to β-catenin and EGFR expression in all patients. DFS and OS based on membrane β-catenin expression level (A and B) and membrane EGFR (C and D). The cut-off points for membranous β-catenin and EGFR were obtained based on optimal correlation with OS and DFS. The cut-off values of membranous β-catenin for OS and DFS were 70 and 55, respectively, while the cut-off values of membranous EGFR were 120 and 105, respectively.

Univariate survival analyses showed that lower membrane β-catenin and EGFR levels were significantly related to better DFS in all patients and in the p16+ group (Table S2 and S3, p<0.001, p<0.001, p<0.001, and p=0.006, respectively). Nuclear β-catenin levels were not significantly associated with DFS in all patients, while negative nuclear β-catenin was significantly related to better DFS in the p16-positive group. Similarly, lower membrane β-catenin levels were significantly related to better OS in all patients and the p16-positive groups (Table S4 and S5, p<0.001 and p =0.009, respectively). However, lower levels of membrane EGFR were associated with more favorable OS only among all patients (p<0.001), and not in the p16+ group. Nuclear β-catenin levels were not significantly associated with OS in all patients or in the p16+ group.

In a multivariable analysis of DFS in all patients, membrane β-catenin, tumor stage, clinical stage, and age were all significant predictors of DFS (Table S6). In p16+ patients, a multivariable analysis of DFS showed only membrane β-catenin, was a significant predictor of DFS (data not shown). Multivariable analysis of OS in all patients showed that membrane EGFR, smoking history, tumor stage, and age were all significant predictors of OS (Table S7). In p16+ patients, a multivariable analysis of OS showed that smoking, tumor stage, cytoplasmic EGFR, and age were all significant predictors of OS (Table S8).

β-catenin and EGFR expression in HPV16-positive HNSCC cell lines

To investigate the possible mechanism underlying the observed nuclear accumulation of β-catenin, a hallmark of the activated canonical Wnt signaling pathway, we further examined cytoplasmic and nuclear β-catenin levels in HNSCC cell lines. In our analysis, we included three HPV16-positive HNSCC cell lines (SCC2, SCC47, and SCC090) and a cervical cancer cell line (CaSki). Four HPV-negative HNSCC cell lines (UM22B, JHU012, PCI13, and PCI15A) were included as controls. We did not observe any differences between the cell lines in β-catenin expression in whole cell lysates (Fig. S2). However, protein fractionation analysis showed that the nuclear protein level of β-catenin in HPV16-positive cells was substantially higher than that in HPV16-negative cells. Interestingly, there were no differences in the level of cytoplasmic β-catenin between HPV16-positive and -negative cancer cells. Since this study found a significant correlation between the levels of membranous β-catenin and EGFR in OPSCC tissues and other researchers reported that activation of EGFR could induce the translocation of β-catenin from the membrane to the nucleus11, we next investigated whether activation of EGFR was associated with the translocation of β-catenin in these cell lines. The level of phospho-EGFR in whole cell extracts was higher in 3 HPV16-positive cell lines than in HPV16-negative cells, suggesting that activation of EGFR may be involved in inducing the translocation of β-catenin from the membrane to the nucleus in HPV16-positive cells.

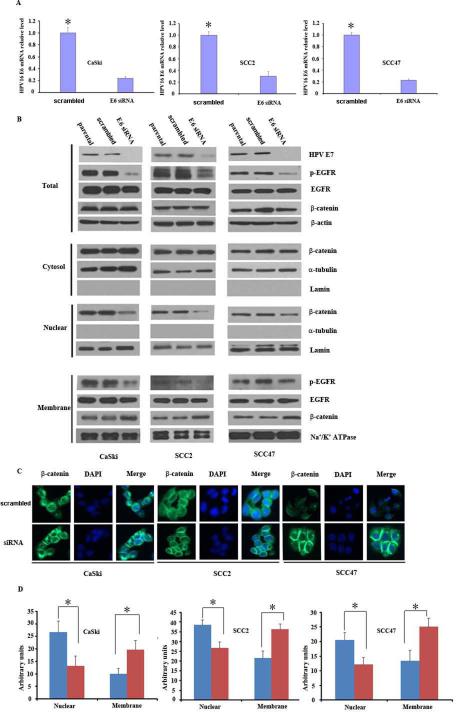

Effect of HPV16 E6/E7 depletion on β-catenin translocation and EGFR activation

To determine whether E6 and E7 oncogenes are responsible for β-catenin translocation, β-catenin levels were examined in HPV16-positive OPSCC cell lines (SCC2 and SCC47) and a cervical cancer cell line (CaSki) after HPV16 E6/E7 repression. HPV16 E6/E7 repression was achieved using HPV16 E6-specific siRNA to reduce the HPV16 E6/E7 transcript. As shown in Figure 3A and S3, HPV16 E6 siRNA transfection decreased the expression of HPV16 E6 and E7 mRNA. Western blot also showed that HPV16 E6 siRNA transfection further led to the downregulation of HPV16 E7 protein (Fig. 3B and S4). Repression of HPV16 E6 and E7 gene expression induced a reduction in the level of nuclear β-catenin. Following the transfection, we also observed increased levels of membrane β-catenin, while levels of cytoplasmic β-catenin remained constant in all 3 cancer cell lines, compared to the levels in control cells transfected with scrambled siRNA and parental cells. Moreover, Western blot analysis revealed that total β-catenin levels were unchanged following E6 siRNA transfection. To investigate whether HPV16 could induce the translocation of β-catenin from the membrane to the nucleus via its activation of EGFR, p-EGFR levels were also examined by Western blot analysis. HPV16 E6 siRNA transfection led to a decrease in phospho-EGFR not only in the whole cell lysate but also in the membrane fraction. Immunofluorescence staining for β-catenin after E6 siRNA transfection confirmed this finding (Fig. 3C and 3D), supporting that HPV16 can regulate translocation of β-catenin in cancer cells.

Figure 3.

HPV16 E6/E7 depletion decreases the phosphorylation of EGFR and the translocation of β-catenin. (A) mRNA level of HPV16 E6 before and after siRNA treatment. HPV16-positive cancer cell lines, CaSki, SCC2 and SCC47 were transfected with HPV16 E6 siRNA. Total RNA was isolated and transcribed to cDNA after 48h. E6 mRNA level was analyzed by quantitative PCR, with GAPDH as a loading control (p<0.05). (B) Western blot analysis of β-catenin, EGFR, and p-EGFR expression in whole cell lysates, cytosol, nuclear, and membrane fractions after HPV16 E6 siRNA transfection in HPV16-positive cell lines. Lamin and α tubulin were nuclear and cytoplasmic loading controls, respectively. (C) Distribution of β-catenin by immunofluorescence staining after HPV16 E6 siRNA transfection in HPV16-positive cell lines. (D) Optical density of immunofluorescence in (C) from three independent experiments. *: p<0.001. These experiments were repeated in triplicate.

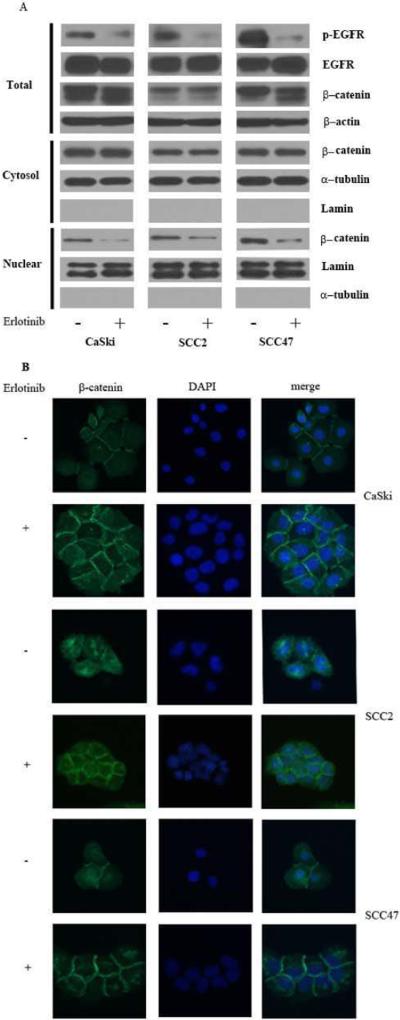

Erlotinib, an EGFR phosphorylation inhibitor, was used to further confirm that EGFR activation may lead to the translocation of β-catenin from the membrane into the nucleus. As shown in Figure 4 and S5, the addition of erlotinib (1 μM) resulted in a reduction of nuclear β-catenin levels without affecting its overall expression.

Figure 4.

Erlotinib, an EGFR activation inhibitor, decreases the translocation of β-catenin. (A) Western blot analysis of β-catenin in whole cell lysates, and protein fractionation. (B) Distribution of β-catenin by immunofluorescence staining after erlotinib treatment for 48h. These experiments were repeated in triplicate.

Effect of HPV16 E6/E7 depletion on the invasion capacity of HPV16-positive cancer cells

To investigate the effect of HPV16 E6/E7 on the invasion capacity of cancer cells, a matrigel invasion assay was conducted. As shown in Figure S6A, after HPV16 E6 siRNA transfection, HNSCC cell lines SCC47 and SCC2 and the cervical cancer cell line CaSki showed decreased invasion capacity compared with that of control cells transfected with scrambled siRNA (p<0.05) without significantly affecting proliferation of the cells (Figure S6B-S6D).

Discussion

In HPV-positive cancer cells, p16 immunoreactivity shows good agreement with HPV in situ hybridization findings. Our results are consistent with those from other groups, supporting p16 as a reliable surrogate for HPV-associated cancer23-26.

In this study, we have shown that, compared with p16-negative OPSCC, p16-positive OPSCC demonstrated a decrease in β-catenin levels at the membrane and an increase in the nucleus, indicating an enhancement of β-catenin translocation from the cell membrane to the nucleus in p16-positive OPSCC (Table 1). This observation is consistent with that of Stenner et al. who found that the nuclear localization of β-catenin expression was significantly higher in HPV-positive tonsillar cancer than in HPV-negative cases (p=0.030)13. Rampias et al., used AQUA quantitative fluorescent immunohistochemistry to demonstrate that HPV(+)/p16(+) tumors expressed near significantly higher levels of β-catenin (p=0.07) than HPV(-)/p16(-) tumors27. However, this study did not assess the subcellular localization of β-catenin. Our study examined β-catenin expression in different cellular compartments and did not find an increase in overall β-catenin in p16-positve OPSCC. In addition, we found that low membrane β-catenin is an independent positive prognostic factor in OPSCC (Fig. 2 and Table S6 and S7). Although positive β-catenin nuclear staining was higher in p16-positive OPSCC (65.22%) compared to p16-negative OPSCC (42.86%) (p=0.002). Other factors could have affected the accumulation of β-catenin in the nucleus besides p16 status. Moreover, the positive β-catenin nuclear staining observed in both p16 positive and negative groups was limited, which may explain the lack of correlation between β-catenin nuclear staining and DFS or OS.

Consistent with our findings in OPSCC tissue samples, our in vitro study further demonstrated a higher nuclear fraction of β-catenin in HPV16 positive cell lines than in negative cell lines (Fig. S2). Depletion of HPV16 E6/E7 did not decrease the level of β-catenin in whole cell lysates, but led to elevated levels of membrane β-catenin and reduced levels of nuclear β-catenin as compared to the controls. Our observations are consistent with those of Wilding et al, who found that co-transfection of an immortalized keratinocyte cell line with HPV-16 E6 and E7 led to redistribution of α-, β-, and γ-catenins from the undercoat membrane to the cytoplasm28. Furthermore, in transgenic mice, HPV16 E6 oncoprotein enhanced the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin29. A study from Rampias et al. also showed that repression of HPV E6 and E7 genes induced a substantial reduction in nuclear β-catenin levels in two cell lines30. In contrast, Lichtig et al. showed that E6 did not alter the expression levels, stability or cellular distribution of β-catenin in the human embryonic kidney cell line, HEK293T31. However, this cell line is not a natural host cell for HPV.

The association between EGFR overexpression and HPV-negative, but not HPV-positive, HNSCC has been reported previously32-35. Our data also showed similar results (data not shown). Furthermore, although the majority of OPSCC cancer cells showed cytoplasmic instead of membrane staining of EGFR, regardless of HPV status, compared to p16-negative OPSCC, p16-positive OPSCC showed a decreased level of membranous EGFR (Table 1). Lower membranous EGFR levels were significantly related to better DFS in all patients and the p16+ group. In p16-positive OPSCC, the Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed that a low level of membranous EGFR was associated with an improved OS (p=0.0248) while the univariate analysis didn't show this association (p=0.125). This inconsistency may be a result of the limited samples (n=104 with high EGFR: 37 and low EGFR: 67). The described association needs further evaluation with a larger sample size of p16-positive tumors. Moreover, the levels of membrane EGFR was positively correlated with membrane β-catenin (r=0.350, p<0.001). Activation of EGFR can induce the translocation of β-catenin from the membrane to the nucleus11, suggesting that EGFR may regulate the distribution of β-catenin in HPV-positive OPSCC. But it is worth noting that β-catenin may be independent on EGFR since β-catenin is not regulated only by EGFR. Furthermore, the multivariable analysis revealed that β-catenin is an independent predictive marker (Table S6).

Based on our findings in OPSCC patient tissues, we hypothesized that HPV may be involved in activation of EGFR and then induction of β-catenin translocation. Compared to HPV-negative cell lines, HPV-positive cancer cells showed higher levels of activated EGFR. HPV16 E6 and E7 depletion decreased the levels of phospho--EGFR, at least at tyrosine 1173, and nuclear translocation of β-catenin. This notion was supported by the inhibition of EGFR activation with erlotinib, which we found abrogated the accumulation of nuclear β-catenin. Our observations are consistent with those of Rampias et al27, who found that phospho-EGFR levels (Tyr845, Tyr992) were substantially reduced after E6/E7 oncogene repression. Phosphorylation of EGFR at Tyr1173 is involved in MAP kinase signaling activation and the NFκB signaling pathway36, whereas Tyr 992 is involved in the PLCγ-mediated downstream signaling pathway37. EGFR Tyr 845 phosphorylation is involved in the p38 MAPK signaling pathway38. Therefore, HPV may induce the phosphorylation of EGFR at multiple sites and then activate several signaling pathways. Rampias et al. found Siah-1 protein could promote the degradation of β-catenin through the ubiquitin/proteasome system27, suggesting that upregulation of Siah-1 is another possible mechanism that contributes to the increase in nuclear β-catenin levels.

HPV-positive patients with OPSCC have a higher incidence of lymph node metastasis (Table 1), suggesting that HPV infection may promote lymph node metastasis at an early stage. Our results further demonstrated that reduction of membranous β-catenin was significantly associated with lymph node metastasis. The depletion of E6 and E7 oncoproteins could repress the invasive potential of HNSCC cell lines. Considering that HPV oncoproteins may induce the translocation of β-catenin into the nucleus, it is reasonable to speculate that they may facilitate the expression of metastasis-associated proteins which promote lymph node metastasis and even distant metastasis. The role of HPV oncoproteins in the regulation of metastasis deserves further investigation.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that HPV16 E6 mediates the translocation of β-catenin to the nucleus, which may be regulated by activated EGFR.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Anthea Hammond for editing the paper. This study is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R33 CA161873) and Georgia Cancer Coalition Distinguished Scholar Award to ZGC.

List of abbreviations

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- OPSCC

oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- LNM

lymph node metastasis

- HNSCC

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- OS

overall survival

- DFS

disease free survival

- WI

weight index

- DAPI

4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcriptional polymerase chain reaction

Footnotes

Competing interests: None claimed

Author contributions:

Zhongliang Hu: experimental work, IHC evaluation, manuscript writing

Susan Muller: IHC evaluation, tissue and clinical information procurement

Guoqin Qian, Jing Xu, Ning Jiang, Dongsheng Wang, Hongzheng Zhang: experimental work

Sungjin Kim, Zhengjia Chen: statistical analysis

Nabil Saba and Dong M. Shin: experimental design

Zhuo Georgia Chen: experimental design, manuscript writing

References

- 1.Forastiere A, Koch W, Trotti A, Sidransky D. Head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1890–1900. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra001375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Applebaum KM, Furniss CS, Zeka A, et al. Lack of association of alcohol and tobacco with HPV16-associated head and neck cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1801–1810. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrero R, Castellsague X, Pawlita M, et al. Human papillomavirus and oral cancer: the International Agency for Research on Cancer multicenter study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1772–1783. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith EM, Ritchie JM, Summersgill KF, et al. Human papillomavirus in oral exfoliated cells and risk of head and neck cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:449–455. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz SM, Daling JR, Doody DR, et al. Oral cancer risk in relation to sexual history and evidence of human papillomavirus infection. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1626–1636. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.21.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillison ML, D'Souza G, Westra W, et al. Distinct risk factor profiles for human papillomavirus type 16-positive and human papillomavirus type 16-negative head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:407–420. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willert K, Nusse R. Beta-catenin: a key mediator of Wnt signaling. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu Y, Zheng S, An N, et al. beta-catenin as a potential key target for tumor suppression. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:1541–1551. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang F, Zeng Q, Yu G, Li S, Wang CY. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling inhibits death receptor-mediated apoptosis and promotes invasive growth of HNSCC. Cell Signal. 2006;18:679–687. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yip WK, Seow HF. Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling by EGF downregulates membranous E-cadherin and beta-catenin and enhances invasion in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2012;318:162–172. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang W, Xia Y, Ji H, et al. Nuclear PKM2 regulates beta-catenin transactivation upon EGFR activation. Nature. 2011;480:118–122. doi: 10.1038/nature10598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papagerakis P, Pannone G, Shabana AH, et al. Aberrant beta-catenin and LEF1 expression may predict the clinical outcome for patients with oropharyngeal cancer. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2012;25:135–146. doi: 10.1177/039463201202500116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stenner M, Yosef B, Huebbers CU, et al. Nuclear translocation of beta-catenin and decreased expression of epithelial cadherin in human papillomavirus-positive tonsillar cancer: an early event in human papillomavirus-related tumour progression? Histopathology. 2011;58:1117–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao M, Sano D, Pickering CR, et al. Assembly and initial characterization of a panel of 85 genomically validated cell lines from diverse head and neck tumor sites. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7248–7264. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferris RL, Martinez I, Sirianni N, et al. Human papillomavirus-16 associated squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN): a natural disease model provides insights into viral carcinogenesis. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:807–815. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang D, Muller S, Amin AR, et al. The pivotal role of integrin beta1 in metastasis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4589–4599. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cattani P, Siddu A, D'Onghia S, et al. RNA (E6 and E7) assays versus DNA (E6 and E7) assays for risk evaluation for women infected with human papillomavirus. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:2136–2141. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01733-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muller S, Su L, Tighiouart M, et al. Distinctive E-cadherin and epidermal growth factor receptor expression in metastatic and nonmetastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: predictive and prognostic correlation. Cancer. 2008;113:97–107. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mandrekar JN MS, Cha SS. Cutpoint determination methods in survival analysis using SAS®. Proceedings of the 28th SAS Users Group International Conference (SUGI) 2003:261–228. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The statistical analysis of failure time data. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cox DR. Regression Models and Life Tables. J Royal Stat Society. 1972;B34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sano T, Oyama T, Kashiwabara K, Fukuda T, Nakajima T. Expression status of p16 protein is associated with human papillomavirus oncogenic potential in cervical and genital lesions. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1741–1748. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65689-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weinberger PM, Yu Z, Haffty BG, et al. Molecular classification identifies a subset of human papillomavirus--associated oropharyngeal cancers with favorable prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:736–747. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smeets SJ, Hesselink AT, Speel EJ, et al. A novel algorithm for reliable detection of human papillomavirus in paraffin embedded head and neck cancer specimen. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:2465–2472. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis JS., Jr p16 Immunohistochemistry as a standalone test for risk stratification in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6(Suppl 1):S75–82. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0369-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rampias T, Pectasides E, Prasad M, et al. Molecular profile of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas bearing p16 high phenotype. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2124–2131. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilding J, Vousden KH, Soutter WP, McCrea PD, Del Buono R, Pignatelli M. E-cadherin transfection down-regulates the epidermal growth factor receptor and reverses the invasive phenotype of human papilloma virus-transfected keratinocytes. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5285–5292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonilla-Delgado J, Bulut G, Liu X, et al. The E6 oncoprotein from HPV16 enhances the canonical Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in skin epidermis in vivo. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10:250–258. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rampias T, Boutati E, Pectasides E, et al. Activation of Wnt signaling pathway by human papillomavirus E6 and E7 oncogenes in HPV16-positive oropharyngeal squamous carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:433–443. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lichtig H, Gilboa DA, Jackman A, et al. HPV16 E6 augments Wnt signaling in an E6AP-dependent manner. Virology. 2010;396:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Troy JD, Weissfeld JL, Youk AO, Thomas S, Wang L, Grandis JR. Expression of EGFR, VEGF, and NOTCH1 Suggest Differences in Tumor Angiogenesis in HPV-Positive and HPV-Negative Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7:344–355. doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0447-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romanitan M, Nasman A, Munck-Wikland E, Dalianis T, Ramqvist T. EGFR and phosphorylated EGFR in relation to HPV and clinical outcome in tonsillar cancer. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:1575–1583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar B, Cordell KG, Lee JS, et al. EGFR, p16, HPV Titer, Bcl-xL and p53, sex, and smoking as indicators of response to therapy and survival in oropharyngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3128–3137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young RJ, Rischin D, Fisher R, et al. Relationship between epidermal growth factor receptor status, p16(INK4A), and outcome in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1230–1237. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pourazar J, Blomberg A, Kelly FJ, et al. Diesel exhaust increases EGFR and phosphorylated C-terminal Tyr 1173 in the bronchial epithelium. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2008;5:8. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nogami M, Yamazaki M, Watanabe H, et al. Requirement of autophosphorylated tyrosine 992 of EGF receptor and its docking protein phospholipase C gamma 1 for membrane ruffle formation. FEBS Lett. 2003;536:71–76. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mueller KL, Powell K, Madden JM, Eblen ST, Boerner JL. EGFR Tyrosine 845 Phosphorylation-Dependent Proliferation and Transformation of Breast Cancer Cells Require Activation of p38 MAPK. Transl Oncol. 2012;5:327–334. doi: 10.1593/tlo.12163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.