Abstract

Background and Purpose

Many GPCRs can be allosterically modulated by small-molecule ligands. This modulation is best understood in terms of the kinetics of the ligand–receptor interaction. However, many current kinetic assays require at least the (radio)labelling of the orthosteric ligand, which is impractical for studying a range of ligands. Here, we describe the application of a so-called competition association assay at the adenosine A1 receptor for this purpose.

Experimental Approach

We used a competition association assay to examine the binding kinetics of several unlabelled orthosteric agonists of the A1 receptor in the absence or presence of two allosteric modulators. We also tested three bitopic ligands, in which an orthosteric and an allosteric pharmacophore were covalently linked with different spacer lengths. The relevance of the competition association assay for the binding kinetics of the bitopic ligands was also explored by analysing simulated data.

Key Results

The binding kinetics of an unlabelled orthosteric ligand were affected by the addition of an allosteric modulator and such effects were probe- and concentration-dependent. Covalently linking the orthosteric and allosteric pharmacophores into one bitopic molecule had a substantial effect on the overall on- or off-rate.

Conclusion and Implications

The competition association assay is a useful tool for exploring the allosteric modulation of the human adenosine A1 receptor. This assay may have general applicability to study allosteric modulation at other GPCRs as well.

Table of Links

| TARGETS | LIGANDS | |

|---|---|---|

| Adenosine A1 receptor | CCPA | DPCPX |

| CPA | NECA |

This Table lists key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (Alexander et al., 2013).

Introduction

Adenosine receptors are a subfamily within the class A of GPCRs, which includes four subtypes: A1, A2A, A2B and A3 (Fredholm et al., 2011). These receptors are expressed in many tissues and play important roles in numerous physiological processes (Gao and Jacobson, 2007). Adenosine receptors can be activated by their endogenous ligand adenosine or by a range of synthetic low MW agonists that share the same binding site as the natural ligand, which is referred to as the orthosteric site (Gao et al., 2005). Adenosine receptors also possess an allosteric site, which is a binding pocket topographically distinct from the orthosteric site (Göblyös and IJzerman, 2011). Currently, many GPCRs, including the adenosine receptor subfamily, have been reported to have one or several allosteric binding sites that interact with an allosteric modulator (Gregory et al., 2007; Keov et al., 2011; Müller et al., 2012; Davie et al., 2013; Gao and Jacobson, 2013; Wang and Lewis, 2013). Such a binding event is believed to result in receptor conformational changes, which, in turn, affect the binding of the orthosteric ligand, its potency and/or level of activation (Christopoulos and Kenakin, 2002; Melancon et al., 2012). Moreover, the extent of allosteric modulation also depends upon the nature of the orthosteric ligand, so-called probe dependency (Christopoulos, 2002; Keov et al., 2011). These complexities add difficulties to a full understanding of the concept and mechanism of allosteric modulation.

Recently, an increasing amount of evidence suggests that ligand–receptor binding kinetics is an overlooked key factor in the broader concept of a drug's mechanism of action (Copeland et al., 2006; Zhang and Monsma, 2010; Guo et al., 2014). Insight in the ligand–receptor binding kinetics may further our knowledge of the molecular mechanism of GPCR allosterism and improve our understanding of this concept (May et al., 2010). However, current kinetic studies of GPCR allosterism mostly rely upon the ‘probe’ dissociation experiment, that is, determining the change in the dissociation rate of a radiolabelled orthosteric ligand (Kostenis and Mohr, 1996; Christopoulos and Kenakin, 2002; De Amici et al., 2010). This radiolabelling process is both labour-intensive and, importantly, only practical for high affinity ligands. As a consequence, the investigation of GPCR allosterism from a kinetic point of view has been limited. Therefore, it is highly desirable to measure the binding kinetics of label-free orthosteric ligands in the absence or presence of an allosteric modulator.

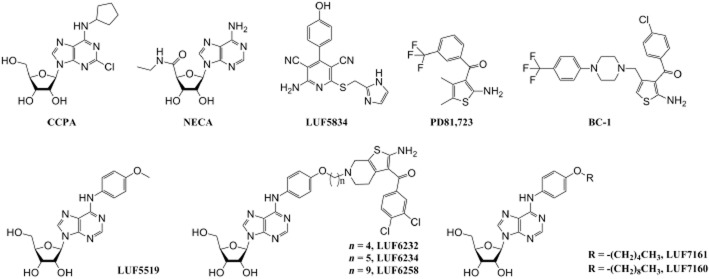

To determine the binding kinetics, we followed a recently validated competition association assay on the human adenosine A1 receptor in our laboratory (Guo et al., 2013), based upon the mathematical model described by Motulsky and Mahan (1984). In the current study, we examined the association and dissociation rates of several adenosine A1 receptor agonists in the absence or presence of different allosteric modulators (Figure 1). Among these compounds, CCPA (2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine) and NECA (N-5′-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine) are ribose-containing A1 receptor agonists (Lohse et al., 1988; Müller, 2001), whereas LUF5834 [2-amino-4-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-6-(1H-imidazol-2ylmethyl-sulfanyl)-pyridine-3,5-dicarbonitrile] is a A1 receptor agonist without the ribose moiety (Beukers et al., 2004). The allosteric modulators, PD81,723 (2-amino-4,5-dimethyl-3-thienyl)-[3-(trifluoromethyl)-phenyl]methanone) and BC-1 [i.e. compound 8j by Romagnoli et al. (2008), 2-amino-4-((4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)piperazin-1-yl)methyl)thiophen-3-yl)(4-chlorophenyl)methanone] are allosteric enhancers of the A1 receptor (Bruns and Fergus, 1990; Romagnoli et al., 2008). The binding kinetics of three ‘bitopic’ ligands (synthesized in-house), namely LUF6232 {N6-[2-amino-3-(3,4-dichlorobenzoyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno-[2,3-c]pyridin-6-yl-4-butyloxy-4-phenyl]-adenosine}, LUF6234 {N6-[2-amino-3-(3,4-dichlorobenzoyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno-[2,3-c]pyridin-6-yl-5-pentyloxy-4-phenyl]-adenosine} and LUF6258 {N6-[2-amino-3-(3,4-dichlorobenzoyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[2,3-c]-pyridin-6-yl-9-nonyloxy-4-phenyl]-adenosine} (Figure 1, Narlawar et al., 2010), were also investigated, as they are useful tools for the exploration of A1 receptor allosteric modulation (Lane et al., 2013). These bitopic ligands share the same orthosteric and allosteric pharmacophores, mimicking LUF5519 [A1 receptor agonist, N6-(4-methoxyphenyl)adenosine] and PD81,723 {2-amino-4,5-dimethyl-3-thienyl)-[3-(trifluoromethyl)-phenyl]methanone}, respectively, which are covalently linked via a spacer with different lengths, that is, four-, five- and nine-carbon atoms respectively.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of compounds used in the present study. CCPA, NECA and LUF5519 are ribose-containing adenosine A1 receptor agonists, whereas LUF5834 is a non-ribose agonist (Lohse et al., 1988; Müller, 2001; Beukers et al., 2004); PD81,723 and BC-1 are allosteric enhancers for adenosine A1 receptor agonists (Romagnoli et al., 2008). LUF6232, LUF6234 and LUF6258 are in-house synthesized bitopic ligands for the adenosine A1 receptor with four-, five- and nine-carbon linker, respectively (Narlawar et al., 2010). LUF7161 and LUF7160 are newly synthesized monovalent ligands with five-atom linker and nine-atom linker respectively.

Methods

Cell culture and membrane preparation

Cell culture and membrane preparation were performed as reported previously (Guo et al., 2013).

Radioligand displacement assays

Membrane aliquots containing 5 μg of protein were incubated in a total volume of 100 μL assay buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), supplemented with 5 mM MgCl2 and 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS] at 25°C for 1 h. The displacement experiments were performed using 11 concentrations of competing ligands with 2.6 nM [3H]-DPCPX in the absence or presence of 10 μM of PD81,723 or BC-1. In such experiments, CCPA and NECA were also tested in the presence of 1 mM GTP. For the determination of the allosteric potency of PD81,723 and BC-1, 100 nM (IC80 value) CCPA was used in the presence of increasing concentrations of these two allosteric modulators to examine the potentiated [3H]-DPCPX displacement. Non-specific binding was determined in the presence of 100 μM N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CPA) and represented less than 10% of the total binding. Incubations were terminated and samples were obtained as described previously (Guo et al., 2013).

Radioligand association and dissociation assays

Association experiments were performed by incubating membrane aliquots containing 5 μg of protein in a total volume of 100 μL of assay buffer at 25°C with 2.6 nM [3H]-DPCPX. The amount of radioligand bound to the receptor was measured at different time intervals during a total incubation of 45 min in the absence or presence of 1, 10 and 33 μM PD81,723 or BC-1. For the dissociation assay, membrane aliquots containing 5 μg of protein were allowed to reach equilibrium for 1 h with the same amount of radioligand. After the pre-incubation, radioligand dissociation was started by adding 10 μM of DPCPX at different time points in the absence or presence of 1, 10 and 33 μM PD81,723 or BC-1. The amount of radioligand still bound to the receptor was measured at various time intervals for a total of 1 h. Incubations were terminated and samples were obtained as described previously (Guo et al., 2013).

Radioligand competition association assay

The binding kinetics of unlabelled ligands was quantified at 25°C using the competition association assay based upon the theoretical framework by Motulsky and Mahan (1984). This method has been recently adopted and validated on the adenosine A1 receptor in our laboratory (Guo et al., 2013), which enables accurate determination of unlabelled ligands' binding kinetics. In the present study, we followed the same method. In brief, we used a concentration of approximately 1-, 3- and/or 10-fold Ki of the unlabelled ligand with or without the co-incubation of 1, 10 or 33 μM PD81,723 or BC-1. The experiment was initiated by adding membrane aliquots containing 5 μg of protein in a total volume of 100 μL assay buffer at different time points for a total incubation of 1 h, except for LUF6232, LUF6234 and LUF6258, which were incubated for 2 h given their slow kinetic profiles. Incubations were terminated and samples were obtained as described previously (Guo et al., 2013).

Data analysis

All experimental data were analysed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Radioligand displacement curves were fitted to one- and two-state/site binding models. kobs and koff values of [3H]-DPCPX in the absence or presence of PD81,723 or BC-1 were obtained from the association and dissociation curves. Values for kon were obtained by converting kobs values using the following equation:

| (1) |

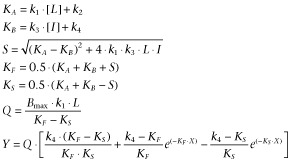

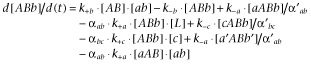

Association and dissociation rates for unlabelled ligands were calculated by fitting the data in the competition association model using ‘kinetics of competitive binding’ (Motulsky and Mahan, 1984):

|

(2) |

where X is the time, Y is the specific [3H]-DPCPX binding (DPM), k1 and k2 are the kon (M−1·min−1) and koff (min−1) of [3H]-DPCPX pre-determined in radioligand association and dissociation assay, respectively, in the absence or presence of different concentrations of PD81,723 or BC-1, L is the concentration of [3H]-DPCPX used (M), Bmax is the total binding (DPM) and I is the concentration unlabelled ligand (M). Fixing these parameters allows the following parameters to be calculated: k3, which is the kon value (M−1·min−1) of the unlabelled ligand, and k4, which is the koff value (min−1) of the unlabelled ligand. Ligand–receptor residence times (RT) were calculated using the following equation (Copeland, 2005):

| (3) |

The derived association and dissociation rates of the unlabelled ligand were used to calculate the ‘kinetic KD’ using the following equation:

| (4) |

Data simulations

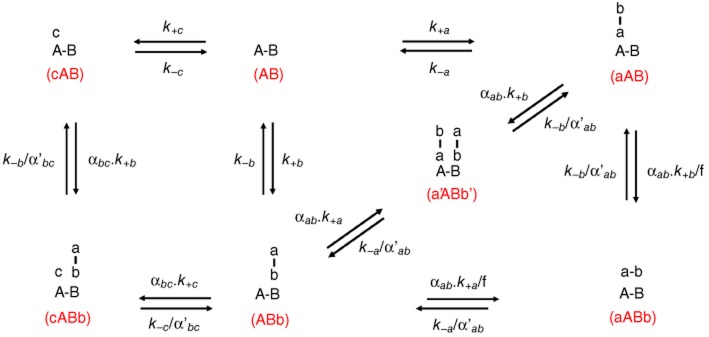

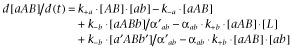

Differential equations (see below, Equations 5–12) were used to follow the time (t)-wise changes in target ‘AB’ occupancy by a bitopic ligand, ‘ab’, or a monovalent ligand, ‘c’, based upon the thermodynamic model in Figure 2 (Vauquelin et al., 2013). The abbreviation notions for different molecular complexes are in parentheses in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the monovalent, ‘c’, and bitopic, ‘ab’, ligand–target site interactions. The bitopic ligand bears two distinct pharmacophores: ‘a’ and ‘b’. ‘AB’ is the target with distinct binding sites ‘A’ and ‘B’. ‘a’ and ‘c’ only bind to ‘A’ in a competitive manner and ‘b’ only binds to ‘B’. The abbreviated notation for the free target and target complexes is in parentheses. k+a, k+b and k+c (in M−1·min−1) are the microscopic association rate constants and k−a, k−b and k−c (in min−1) are the microscopic dissociation rate constants for a-A, b-B and c-A binding respectively. αab and αbc are cooperativity factors affecting the association process of different pharmacophores. α'ab and α'bc are cooperativity factors affecting the dissociation process of different pharmacophores.

| (5) |

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

in which k+a and k+b (M−1·min−1) are the microscopic association rate constants of the bitopic ligand, ab, for a-A and b-B binding; k−a and k−b (min−1) are the dissociation rate constants of the bitopic ligand, ab, for a-A and b-B unbinding; [c] is the concentration of the monovalent ligand (M), representing the radioligand; k+c and k−c are the association rate and dissociation rate for c-A binding/unbinding. Both ab and c are assumed to be in large excess over the target sites. [ab] is the total concentration (M) of the bitopic ligand and [L] is the local concentration of the second pharmacophore to bind. [AB]occ by c is the sum of all c-bound species and is expressed as percentage of the total target population. The cooperativity factor (α), which is defined by how much binding affinities of two ligands increase (Lazareno and Birdsall, 1995), was also included in the thermodynamic model in Figure 2 and the data simulations. The cooperativity factor that affects the association process was named α; the cooperativity factor that affects the dissociation process was named α’. The first pharmacophore of the bitopic ligand to bind (either ‘a’ or ‘b’) may trigger a conformational change of the target. This may modify the association rate constant that governs the binding of the second pharmacophore (‘b’ if ‘a’ was bound first and vice versa) and/or the dissociation rate constant of the first unbinding event (i.e. dissociation of ‘a’ or ‘b’ from the aABb complex). Additionally, while the binding of ‘a’ and ‘c’ to ‘A’ is considered to be competitive, the c-A and b-B interactions may show cooperativity as well. Thus, the cooperativity factors were subdivided even further to yield αab and αbc for association and α'ab and α'bc for dissociation (Vauquelin et al., 2013). The macroscopic kon and koff value of a bitopic ligand can be theoretically calculated using the following equations (Vauquelin, 2013; Vauquelin et al., 2013; Vauquelin and Charlton, 2013):

| (13) |

| (14) |

Data simulations were performed to mimic the binding of a radioligand (represented by the target occupancy of ‘c’) by solving Equations 5–12 during a period of 50 min, either alone or in the presence of increasing concentrations of ‘ab’. The microscopic binding kinetics of the bitopic ligand ‘ab’ were defined as k+a = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−a = 1 min−1, k+b = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−b = 1 min−1 and [L] = 0.29 mM. The binding kinetics of the monovalent ligand ‘c’ was defined as k+c = 1 × 107 M−1·min−1, k−c = 0.3 min−1 and [c] = 100 nM. The cooperativity factors of ‘ab’ were set as (i) αab = 10; (ii) αab = 0.1; (iii) α'ab = 10; (iv) α'ab = 0.1. For simplicity, we kept αbc = α'bc = 1. The simulated data were collected for a total of 50 min and subsequently subjected to the competition association model using ‘kinetics of competitive binding’ (Motulsky and Mahan, 1984). The kinetics data obtained thereof were compared with the theoretically calculated values (by subjecting the defined microscopic rate constants mentioned above into Equations 13 and 14) to explore the relevance of using the competition association assay for bitopic ligands' binding kinetics.

Materials

[3H]-1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine ([3H]-DPCPX, specific activity 103 Ci·mmol−1) was purchased from ARC, Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Unlabelled DPCPX and CCPA were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). NECA was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). CPA was obtained from Research Biochemicals Inc. (Natick, MA, USA). LUF5834, PD81,723 and BC-1 were prepared in-house following synthesis routes reported previously (Bruns and Fergus, 1990; Beukers et al., 2004; Romagnoli et al., 2008). LUF5519, LUF6232, LUF6234 and LUF6258 were also synthesized in-house as described by Narlawar et al. (2010). The synthesis of LUF7160 [N6-(4-nonyloxyphenyl) adenosine] and LUF7161 [N6-(4-pentyloxyphenyl)adenosine] was performed as described in the Supporting Information. CHAPS [3-((3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio)-1-propanesulfonate] was obtained from Carl Roth GmbH (Karlsruhe, Germany). GTP was purchased from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium). Chinese hamster ovary cells stably expressing the human A1 receptor (CHO-hA1R) were obtained from Prof. Steve Hill (University of Nottingham, UK). All other chemicals were of analytical grade and obtained from standard commercial sources.

Results

Quantification of the affinity (Ki) of A1 receptor ligands in the absence or presence of PD81,723, BC-1, GTP or a combination thereof in displacement experiments

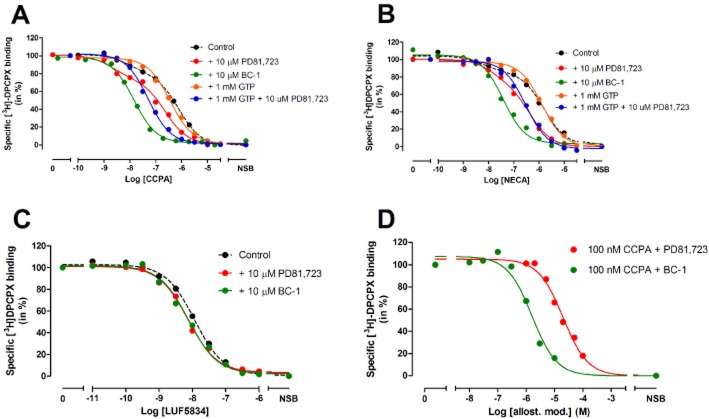

To determine the affinities of several agonists at the A1 receptor in the absence or presence of allosteric modulators, radioligand displacement experiments were performed. All compounds tested produced concentration-dependent inhibition of specific [3H]-DPCPX binding (Figure 3) and their affinities are detailed in Table 1. Among the agonists tested, the binding of CCPA and NECA was preferably fitted in a two-site/state competition model, whereas the non-ribose agonist LUF5834 was best described in a one-site/state competition model. Upon the addition of 1 mM GTP, the binding curves of CCPA and NECA were best fitted with a one-site/state competition model with Ki values of 141 ± 28 and 505 ± 93 nM respectively (Table 1). In the presence of 10 μM PD81,723, CCPA demonstrated a significant increase of both its high and low affinity (KH = 2 ± 1 nM, KL = 77 ± 5 nM). This effect was even more pronounced upon the addition of BC-1. Notably, the two-site binding curve of CCPA was shifted to a one-site binding curve (Ki = 4.5 ± 0.3 nM) in the presence of this allosteric modulator. Similar to CCPA, the affinity of NECA was increased in the presence of PD81,723 or BC-1 respectively. Both were mainly from a gain in affinity at the low-affinity binding site. Similar observations were carried out in the experiments with 1 mM GTP to solely examine agonist binding to the G protein-uncoupled form of the A1 receptor. In this situation, the affinities of CCPA and NECA in the presence of PD81,723 (20 ± 2 and 115 ± 23 nM) increased approximately seven- and fivefold compared with their values in the absence of the same allosteric modulator respectively. In contrast to the ribose-containing agonists, that is, CCPA and NECA, the binding affinity of non-ribose agonist LUF5834 to the A1 receptor was not significantly altered by the presence of either allosteric modulator.

Figure 3.

(A) Displacement of specific [3H]-DPCPX binding from the adenosine A1 receptor at 25°C by CCPA in the absence or presence of 10 μM PD81,723, 10 μM BC-1, 1 mM GTP or a combination thereof. (B) Displacement of specific [3H]-DPCPX binding from the adenosine A1 receptor at 25°C by NECA in the absence or presence of 10 μM PD81,723, 10 μM BC-1, 1 mM GTP or a combination thereof. (C) Displacement of specific [3H]-DPCPX binding from the adenosine A1 receptor at 25°C by LUF5834 in the absence or presence of 10 μM PD81,723 or BC-1. (D) Displacement of specific [3H]-DPCPX binding from the adenosine A1 receptor at 25°C by 100 nM CCPA (normalized as 100%) in the presence of increased concentrations of PD81,723 or BC-1. Representative graphs from one experiment performed in duplicate.

Table 1.

[3H]-DPCPX displacement experiments by CCPA, NECA and LUF5834 on CHO-hA1R membranes

| Compound added | CCPA | NECA | LUF5834 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KH (nM) | KL or Ki (nM) | RH (%) | KH (nM) | KL or Ki (nM) | RH (%) | Ki (nM) | |

| Control (none) | 16 ± 1 | 338 ± 27 | 20 ± 4 | 4 ± 1 | 731 ± 94 | 18 ± 3 | 7.8 ± 1.5 |

| +1 mM GTP | NA | 141 ± 28 | NA | NA | 505 ± 93 | NA | ND |

| +10 μM PD81,723 | 2 ± 1 | 77 ± 5 | 27 ± 7 | 6 ± 4 | 200 ± 78 | 26 ± 9 | 9.6 ± 2.6 |

| +1 mM GTP, +10 μM PD81,723 | NA | 20 ± 2 | NA | NA | 115 ± 23 | NA | ND |

| +10 μM BC-1 | NA | 4.5 ± 0.3 | NA | 8 ± 2 | 128 ± 27 | 10 ± 3 | 6.7 ± 1.5 |

Data are shown as mean ± SEM of three separate experiments each performed in duplicate. KH and KL are values for the high- and low-affinity states, respectively, and are shown for data that could be fitted to a two-state model; RH is the fraction of receptors in the high affinity state and is shown in %. Ki values are shown for data that could be fitted to a one-state model. NA, not available; ND, not determined.

Quantification of the potency of two allosteric modulators

The potencies of PD81,723 and BC-1 were investigated by examining the enhanced [3H]-DPCPX displacement from the A1 receptor by 100 nM CCPA (IC80) in the presence of increasing concentrations of these two allosteric modulators. It follows from Figure 3D that BC-1 had a 13-fold higher potency (EC50 = 1.5 ± 0.2 μM) than PD81,723 (EC50 = 19 ± 2 μM) for modulating CCPA binding to the A1 receptor.

Quantification of the association [kon (k1)] and dissociation rate constants [koff (k2)] of [3H]-DPCPX in the absence or presence of PD81,723 or BC-1

Since knowledge of the association [kon (k1)] and dissociation rate constants [koff (k2)] of [3H]-DPCPX was necessary for subsequent competition association assays in the presence of an allosteric modulator, we performed a direct [3H]-DPCPX association and dissociation assay to determine DPCPX's binding kinetics in the absence or presence of 1, 10 and 33 μM PD81,723 or BC-1. As detailed in Table 2, [3H]-DPCPX displayed a fast association (1.2 ± 0.1 × 108 M−1·min−1) and dissociation rate (0.23 ± 0.01 min−1) in the absence of PD81,723, which values were not significantly affected by the presence of 1, 10 or 33 μM PD81,723 (P > 0.05, Student's t-test). In contrast, BC-1, a structural analogue of PD81,723 (Figure 1), in most cases significantly changed both the on- and off-rates of [3H]-DPCPX at three different concentrations. These k1 and k2 values in the absence or presence of an allosteric modulator allowed us to further explore the corresponding k3 and k4 values of unlabelled ligands.

Table 2.

The association and dissociation rates of [3H]-DPCPX binding to CHO-hA1R membranes in the absence or presence of 1, 10 or 33 μM PD81,723 or BC-1

| Cmpd | kon (M−1·min−1)a | koff (min−1)b | KD (nM)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| DPCPX | 1.2 ± 0.1 × 108 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 1.9 ± 0.3 |

| +1 μM PD81,723 | 1.2 ± 0.1 × 108 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 2.0 ± 0.1 |

| +10 μM PD81,723 | 1.4 ± 0.1 × 108 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 1.6 ± 0.1 |

| +33 μM PD81,723 | 1.6 ± 0.2 × 108 | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 1.7 ± 0.1 |

| +1 μM BC-1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 × 108 | 0.14 ± 0.00*** | 0.93 ± 0.04*** |

| +10 μM BC-1 | 2.8 ± 0.2 × 108** | 0.080 ± 0.004*** | 0.29 ± 0.02*** |

| +33 μM BC-1 | 2.8 ± 0.3 × 108** | 0.076 ± 0.004*** | 0.27 ± 0.01*** |

Values are means ± SEM of three separate experiments each performed in duplicate.

Association [kon (k1)] of [3H]-DPCPX to CHO-hA1R membranes at 25°C; kon = (kobs − koff)/[radioligand].

Dissociation [koff (k2)] of [3H]-DPCPX from CHO-hA1R membranes at 25°C.

‘Kinetic KD’ = koff/kon.

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001 compared with the values in the absence of an allosteric modulator; Student's t-test.

Validation and optimization of the competition association assay for the binding kinetics of unlabelled ligands on the A1 receptor in the absence or presence of an allosteric modulator

In our previous work at the adenosine A1 receptor, we have validated the competition association assay to test a ligand's binding kinetics (Guo et al., 2013). Here, we adopted the method and examined the binding kinetics of unlabelled DPCPX in the absence or presence of two allosteric modulators (PD81,723 and BC-1). The obtained kon (k3) and koff (k4) values for DPCPX were compared with the k1 and k2 values in the radiolabelled probe, that is, [3H]-DPCPX, association and dissociation assay (Table 3). In the presence of 10 μM PD81,723, the k1 (1.4 ± 0.1 × 108 M−1·min−1) and k2 (0.23 ± 0.01 min−1) values of DPCPX corresponded to its k3 (1.9 ± 0.1 × 108 M−1·min−1) and k4 (0.30 ± 0.07 min−1) values. This held true for the presence of 10 μM BC-1 as well (k3 = 2.7 ± 0.1 × 108 M−1·min−1, k4 = 0.072 ± 0.005 min−1), although the presence of BC-1 affected the on- and off-rates of the radiolabeled probe (k1 = 2.8 ± 0.2 × 108 M−1·min−1, k2 = 0.080 ± 0.004 min−1). These findings convinced us that we could use this assay to measure the binding kinetics of unlabelled orthosteric ligands in the presence of an allosteric modulator.

Table 3.

Comparison of the binding kinetics of DPCPX in the absence or presence of 10 μM PD81,723 or BC-1 determined by radioligand association and dissociation assay or by the competition association assay

| kon (M−1·min−1) | koff (min−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k1a | k3b | k2a | k4b | |

| DPCPX | 1.2 ± 0.1 × 108 | 1.7 ± 0.4 × 108 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.26 ± 0.01 |

| +10 μM PD81,723 | 1.4 ± 0.1 × 108 | 1.9 ± 0.4 × 108 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.30 ± 0.07 |

| +10 μM BC-1 | 2.8 ± 0.2 × 108 | 2.7 ± 0.1 × 108 | 0.080 ± 0.004 | 0.072 ± 0.005 |

Values are means ± SEM of three separate experiments each performed in duplicate.

kon (k1) and koff (k2) of unlabelled DPCPX in the absence or presence of 10 μM PD81,723 or BC-1 were determined in [3H]-DPCPX (2.6 nM) association and dissociation assay.

kon (k3) and koff (k4) of unlabelled CCPA in the absence or presence of 10 μM PD81,723 or BC-1 were determined in [3H]-DPCPX (2.6 nM) competition association assays.

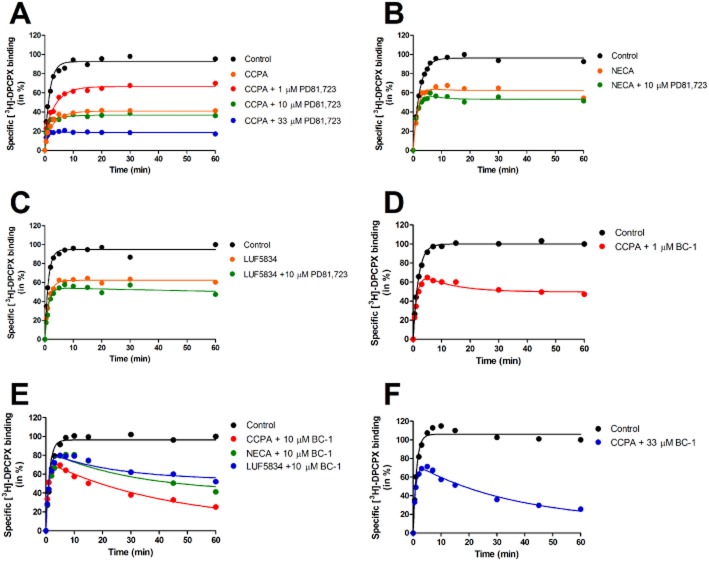

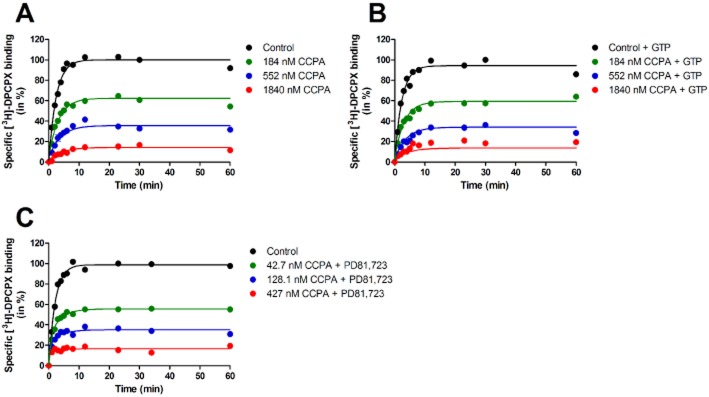

Next, we determined the on- and off-rates of CCPA, either in the absence or presence of 1 mM GTP (Figure 4A and 4B). The presence of 1 mM GTP did not significantly change the agonist's association and dissociation rate constants, which were 1.1 ± 0.2 × 107 M−1·min−1 and 1.2 ± 0.3 min−1 (Table 4). Notably, the kinetic KD values for CCPA (109 ± 12 nM and 169 ± 40; Table 4) derived from their respective on- and off-rates were in agreement with CCPA's Ki value obtained from the equilibrium binding experiments in the presence of 1 mM GTP (i.e. 141 ± 28 nM; Table 1). Thus, we decided not to add GTP in our system for further kinetic profiling of agonists. We also examined the binding kinetics of CCPA by analysing its data at three different concentrations (i.e. 184, 552 or 1840 nM), given that the agonist is known to occupy both high- and low-affinity binding sites. It follows from Table 4 that the on- and off-rates derived by analysing a single concentration were not statistically different from one another or from the values obtained by global, simultaneous analysis of three concentrations of unlabelled CCPA (P > 0.05). This held also true when we further included 10 μM PD81,723 (Table 4; Figure 4C). Thus, a single agonist concentration was used in the following experiments.

Figure 4.

[3H]-DPCPX competition association assay in the absence or presence of three different concentrations of unlabelled CCPA. (A) Control experiment. (B) Experiment in the presence of 1 mM GTP. (C) Experiment in the presence of 10 μM PD81,723. Representative graphs from one experiment performed in duplicate (see Table 4 for kinetic values).

Table 4.

The binding kinetics of unlabeled CCPA in the absence or presence of 10 μM PD81,723 or 1 mM GTP

| Compound | kon (M−1·min−1)a | koff (min−1)a | KD (nM)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCPAc | 1.1 ± 0.2 × 107 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 109 ± 12 |

| CCPA (184 nM)d | 8.2 ± 2.0 × 106e | 0.85 ± 0.23e | 104 ± 22e |

| CCPA (552 nM)d | 9.0 ± 2.5 × 106e | 1.1 ± 0.3e | 122 ± 27e |

| CCPA (1840 nM)d | 6.7 ± 2.7 × 106e | 0.91 ± 0.40e | 136 ± 47e |

| CCPA + 1 mM GTPc | 1.3 ± 0.4 × 107f | 2.2 ± 0.6f | 169 ± 40f |

| CCPA + 10 μM PD81,723c | 1.1 ± 0.1 × 107 | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 28 ± 3 |

| CCPA (43 nM) + 10 μM PD81,723d | 1.4 ± 0.2 × 107g | 0.34 ± 0.06g | 24 ± 3g |

| CCPA (128 nM) + 10 μM PD81,723d | 1.0 ± 0.1 × 107g | 0.32 ± 0.03g | 32 ± 3g |

| CCPA (427 nM) + 10 μM PD81,723d | 0.7 ± 0.1 × 107g | 0.24 ± 0.03g | 34 ± 4g |

Values are means ± SEM of three separate experiments each performed in duplicate.

kon (k3) and koff (k4) of unlabelled CCPA in the absence or presence of 10 μM PD81,723 or 1 mM GTP were determined in [3H]-DPCPX (2.6 nM) competition association assays.

Kinetic KD = koff/kon; kon (k3) and koff (k4) values of unlabelled CCPA were generated from [3H]-DPCPX (2.6 nM) competition association assay at 25°C.

Data obtained by globally analysing three concentrations of unlabelled CCPA.

Data obtained by analysing a single concentration of unlabelled CCPA.

Not significantly different from its respective values obtained by globally analysing three concentrations of unlabelled CCPA; P > 0.05; Student's t-test.

Not significantly different from its respective values in the absence of 1 mM GTP; P > 0.05; Student's t-test.

Not significantly different from data obtained by globally analysing three concentrations of unlabelled CCPA in the presence of 10 μM PD81,723; P > 0.05; Student's t-test.

Quantification of the binding kinetics of unlabelled agonists on the A1 receptor in the absence or presence of an allosteric modulator by using the competition association assay

We examined the binding kinetics of three A1 receptor agonists (CCPA, NECA and LUF5834) in the absence or presence of two allosteric modulators (PD81,723 and BC-1). Several observations were made. Firstly, both allosteric modulators affected the affinity of the orthosteric ligands, by influencing their binding kinetics (Table 5; Figure 5). Taking CCPA as an example, its dissociation rate decreased almost fourfold in the presence of 10 μM PD81,723 (koff = 0.32 ± 0.03 min−1), whereas its association rate was not much affected. As a result, the affinity (KD = 131 ± 21 nM) of CCPA was increased over fourfold in the presence of PD81,723 (32 ± 3 nM). In comparison, 10 μM BC-1 lowered CCPA's off-rate by 100-fold (koff = 0.011 ± 0.03 min−1) and raised its on-rate by 3.5-fold (kon = 3.5 ± 0.2 × 107 M−1·min−1). Overall, this resulted in a strongly increased A1 receptor affinity of 0.31 ± 0.05 nM. This finding correlated to our above-mentioned statement that BC-1 is a more potent A1 receptor allosteric modulator than PD81,723, yet with more detailed kinetic information. Secondly, the allosteric effect was concentration dependent. It follows from Table 5 and Figure 5 that BC-1 slowed down the dissociation process of CCPA by 19- to 105-fold at low concentrations (i.e. 1 μM or 10 μM), whereas at a relatively high concentration (i.e., 33 μM), it further decreased CCPA's off-rate by another twofold. A similar trend was observed for PD81,723, although the effect was smaller in comparison to that of BC-1. Thirdly, A1 receptor allosteric modulation was ‘probe-dependent’, that is, the on- and off-rates of different orthosteric ligands were influenced to varying degrees in the presence of the same allosteric modulator. For instance, in the presence of 10 μM PD81,723, the dissociation rates of ribose-containing agonists (CCPA and NECA) were decreased by approximately four- to fivefold, whereas the dissociation rate of the non-ribose agonist (LUF5834) was not significantly affected (0.92 ± 0.09 min−1 vs. 0.78 ± 0.08 min−1, P = 0.31). Similarly, in the presence of the more potent allosteric modulator BC-1, all three orthosteric ligands showed varying changes in their dissociation rates. A significant difference was observed for the residence times of LUF5834 and CCPA, that is, 34- or 200-fold increased to 29 ± 3 and 172 ± 50 min−1 respectively. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that an opposite effect on the non-ribose agonist's (LUF5834) association process was observed compared with the ribose-containing ligands in the presence of 10 μM BC-1. CCPA and NECA had a 3.6- and 1.8-fold increase in their on-rates, respectively, whereas for LUF5834, a five-fold decreased kon value was observed (4.2 ± 0.4 × 107 M−1·min−1).

Table 5.

List of binding kinetic variables (association rate, dissociation rate, residence time (RT) and kinetic KD) for CCPA, NECA and LUF5834 in the absence or presence of an allosteric modulator (PD81,723 or BC-1) at CHO-hA1R membranes, derived from competition association assays

| Cmpd | kon (M−1·min−1)a | koff (min−1)a | RT (min)b | KD (nM)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCPA | 9.6 ± 1.8 × 106 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.86 ± 0.17 | 131 ± 21 |

| +1 μM PD81,723 | 1.9 ± 0.5 × 107 | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 43 ± 7* |

| +10 μM PD81,723 | 1.0 ± 0.1 × 107 | 0.32 ± 0.03* | 3.1 ± 0.3* | 32 ± 3** |

| +33 μM PD81,723 | 3.4 ± 0.8 × 107* | 0.20 ± 0.02** | 5.0 ± 0.4*** | 5.9 ± 1.9** |

| +1 μM BC-1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 × 107* | 0.063 ± 0.005** | 16 ± 1*** | 3.3 ± 0.2** |

| +10 μM BC-1 | 3.5 ± 0.2 × 107*** | 0.011 ± 0.003** | 91 ± 14** | 0.31 ± 0.05** |

| +33 μM BC-1 | 3.5 ± 0.3 × 107** | 0.0058 ± 0.0029** | 172 ± 50* | 0.17 ± 0.05** |

| NECA | 0.9 ± 0.4 × 106 | 0.47 ± 0.09 | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 522 ± 146 |

| +10 μM PD81,723 | 3.0 ± 0.3 × 106* | 0.21 ± 0.02* | 4.8 ± 0.3** | 70 ± 6* |

| +10 μM BC-1 | 1.6 ± 0.2 × 106 | 0.025 ± 0.005** | 40 ± 5** | 16 ± 2* |

| LUF5834 | 2.0 ± 0.2 × 108 | 0.92 ± 0.09 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.4 |

| +10 μM PD81,723 | 2.6 ± 0.2 × 108 | 0.78 ± 0.08 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.2 |

| +10 μM BC-1 | 4.2 ± 0.4 × 107** | 0.034 ± 0.007*** | 29 ± 3*** | 0.81 ± 0.11*** |

Data are shown as mean ± SEM of three separate experiments each performed in duplicate.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001 compared with the values in the absence of an allosteric modulator; Student's t-test.

kon (k3) and koff (k4) of unlabelled A1 receptor agonists in the absence or presence of an allosteric modulator (PD81,723 or BC-1) were determined in [3H]-DPCPX (2.6 nM) competition association assays.

RT (residence time) = 1/koff.

Kinetic KD = koff/kon; kon (k3) and koff (k4) values of unlabeled antagonists were generated from [3H]-DPCPX (2.6 nM) competition association assays at 25°C.

Figure 5.

(A) [3H]-DPCPX competition association assay in the absence or presence of unlabeled CCPA with or without different concentrations of PD81,723. (B) [3H]-DPCPX competition association assay in the absence or presence of unlabelled NECA with or without 10 μM PD81,723. (C) [3H]-DPCPX competition association assay in the absence or presence of unlabelled LUF5834 with or without 10 μM PD81,723. (D) [3H]-DPCPX competition association assay in the absence or presence of unlabelled CCPA with or without 1 μM BC-1. (E) [3H]-DPCPX competition association assay in the absence or presence of unlabeled CCPA, NECA or LUF5834 with or without 10 μM BC-1. (F) [3H]-DPCPX competition association assay in the absence or presence of unlabelled CCPA with or without 33 μM BC-1. Data were fitted to Equation 2 described in the Methods section to calculate the kon (k3) and koff (k4) values of unlabelled ligands by using the respective k1 and k2 values of [3H]-DPCPX under different conditions. Representative graphs from one experiment performed in duplicate (see Table 5 for kinetic values).

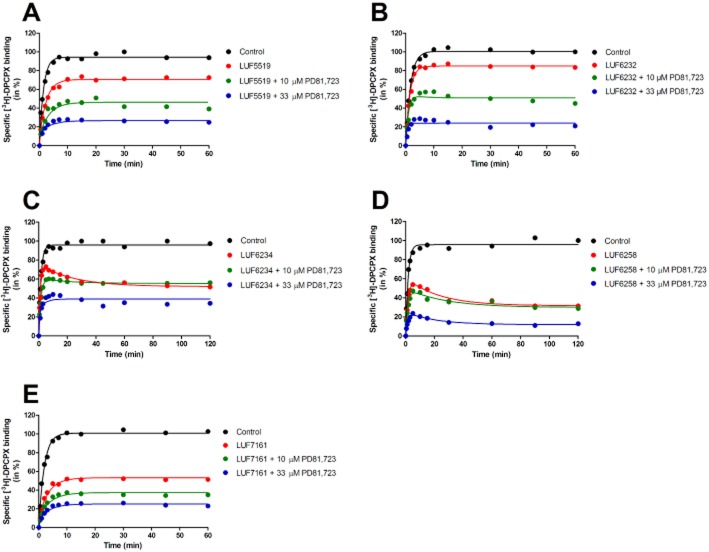

Quantification of the binding kinetics of bitopic ligands for the A1 receptor in the absence or presence of an allosteric modulator by using the competition association assay

The binding kinetics of three A1 receptor bitopic ligands, synthesized in-house, were investigated in the competition association assay. These three ligands, LUF6232, LUF6234 and LUF6258, with four-, five- and nine-carbon spacer length, respectively (Figure 1), were previously designed and synthesized as tools for understanding A1 receptor allosterism (Narlawar et al., 2010). Here, we further examined the binding kinetics of the compounds and compared their values to the orthosteric ligand LUF5519 in combination with PD81,723 (each representing the orthosteric and allosteric pharmacophore of the bitopic ligands, respectively; see Figure 1 for chemical structures). In the absence of an allosteric modulator, LUF5519 displayed an on-rate of 2.0 ± 0.4 × 106 M−1·min−1 and an off-rate of 1.19 ± 0.19 min−1, which led to an affinity of 595 ± 92 nM (Figure 6A; Table 7). Upon the addition of 10 μM PD81,723, the association rate of LUF5519 (kon = 2.4 ± 1.4 × 106 M−1·min−1) did not significantly change, whereas the dissociation rate decreased by approximately threefold from 1.19 ± 0.19 to 0.38 ± 0.05 min−1 (Figure 6A; Table 7). Further raising the concentration of PD81,723 to 33 μM increased LUF5519's on-rate to 9.1 ± 1.1 × 106 M−1·min−1, while a smaller effect on its off-rate was observed (0.46 ± 0.07 min−1). Taken together, this resulted in an enhanced kinetic KD value of 51 ± 16 nM. However, after covalently linking the allosteric and orthosteric pharmacophores, all three bitopic ligands demonstrated a significantly decreased association rate of over 33-fold in comparison to LUF5519 (LUF6232, 6.0 ± 0.3 × 104 M−1·min−1, LUF6234, 5.3 ± 0.7 × 104 M−1·min−1 and LUF6258, 0.8 ± 0.3 × 104 M−1·min−1), indicative of an extra hurdle for the receptor to accommodate large flexible molecules. With respect to their off-rates, all three compounds displayed significantly longer receptor RTs (LUF6232, RT = 4.5 ± 1.3 min, LUF6234, RT = 19 ± 3 min and LUF6258, RT = 48 ± 11 min) than LUF5519 (RT = 0.8 ± 0.1 min, P < 0.05). Interestingly, the presence of ‘external’ 10 μM PD81,723 significantly increased the association rates of these bitopic ligands (LUF6232, kon = 2.8 ± 0.5 × 106 M−1·min−1; LUF6234, kon = 3.1 ± 0.1 × 106 M−1·min−1; LUF6258, kon = 3.0 ± 1.4 × 104 M−1·min−1), although LUF6258 was less affected than its four- and five-carbon linker analogues. Such effects were more pronounced when 33 μM PD81,723 was added. As for the dissociation rate, the bitopic ligands demonstrated different profiles upon the addition of 10 μM PD81,723: LUF6234's RT was significantly reduced to 2.5 ± 0.3 min, whereas the RTs of LUF6232 and LUF6258 were not affected (5.3 ± 0.6 and 48 ± 15 min), even after further raising the concentration of PD81,723 to 33 μM (Table 7). In addition, we examined the binding kinetics of a newly synthesized monovalent ligand LUF7161 (Figure 1), which served as a control, as it contains the orthosteric part and the five-atom linker. It follows from Table 7 that LUF7161 had a similar dissociation rate (koff = 1.21 ± 0.32 min−1) as LUF5519, yet its association rate to the A1 receptor was approximately 10-fold lower (kon = 2.7 ± 0.7 × 105 M−1·min−1) than LUF5519. Upon the addition of 10 and 33 μM PD81,723, the association rate of LUF7161 was 14- and 17-fold higher, respectively, whereas its dissociation rates were less affected in comparison to its kinetics in the absence of the allosteric modulator. The other monovalent ligand with nine-atom linker (LUF7160) did not display significant radioligand displacement up to concentrations of 33 μM (data not shown); thus, its binding kinetics were not determined.

Figure 6.

(A) [3H]-DPCPX competition association assay in the absence or presence of unlabeled LUF5519 with or without 10 or 33 μM PD81,723. (B) [3H]-DPCPX competition association assay in the absence or presence of unlabelled LUF6232 with or without 10 or 33 μM PD81,723. (C) [3H]-DPCPX competition association assay in the absence or presence of unlabelled LUF6234 with or without 10 or 33 μM PD81,723. (D) [3H]-DPCPX competition association assay in the absence or presence of unlabelled LUF6258 with or without 10 or 33 μM PD81,723. (E) [3H]-DPCPX competition association assay in the absence or presence of unlabelled LUF7161 with or without 10 or 33 μM PD81,723. Data were fitted to the equations described in the methods to calculate the kon (k3) and koff (k4) values of unlabelled ligands by using the k1 and k2 values of [3H]-DPCPX. Representative graphs from one experiment performed in duplicate (see Table 6 for kinetic values).

Table 7.

Binding parameters for bitopic ligands and their constituent parts in the absence or presence of PD81,723 at CHOhA1R membranes, derived from competition association assays

| Compound | kon (M−1·min−1)a | koff (min−1)a | RT (min)b | KD (nM)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LUF5519 | 2.0 ± 0.4 × 106 | 1.19 ± 0.19 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 595 ± 92 |

| +10 μM PD81,723 | 2.4 ± 1.4 × 106 | 0.38 ± 0.05* | 2.6 ± 0.4* | 158 ± 41* |

| +33 μM PD81,723 | 9.1 ± 1.1 × 106** | 0.46 ± 0.07* | 2.2 ± 0.2** | 51 ± 6** |

| LUF6232 (linker N = 4) | 6.0 ± 0.3 × 105 | 0.22 ± 0.11 | 4.5 ± 1.3 | 367 ± 106 |

| +10 μM PD81,723 | 2.8 ± 0.5 × 106* | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 5.3 ± 0.6 | 68 ± 11* |

| +33 μM PD81,723 | 1.0 ± 0.2 × 107** | 0.21 ± 0.04 | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 21 ± 3* |

| LUF6234 (linker N = 5) | 5.3 ± 0.7 × 104 | 0.052 ± 0.007 | 19 ± 3 | 981 ± 65 |

| +10 μM PD81,723 | 3.1 ± 0.1 × 106*** | 0.40 ± 0.05** | 2.5 ± 0.3** | 129 ± 13*** |

| +33 μM PD81,723 | 7.8 ± 0.9 × 106*** | 0.35 ± 0.05** | 2.9 ± 0.2** | 45 ± 5*** |

| LUF6258 (linker N = 9) | 0.8 ± 0.3 × 104 | 0.021 ± 0.008 | 48 ± 11 | 2625 ± 810 |

| +10 μM PD81,723 | 3.0 ± 1.4 × 104 | 0.021 ± 0.011 | 48 ± 15 | 700 ± 284 |

| +33 μM PD81,723 | 5.8 ± 3.4 × 104 | 0.023 ± 0.014 | 43 ± 15 | 397 ± 194 |

| LUF7161 | 2.7 ± 0.7 × 105 | 1.21 ± 0.32 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 4481 ± 985 |

| +10 μM PD81,723 | 3.8 ± 0.9 × 106* | 0.87 ± 0.21 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 229 ± 45* |

| +33 μM PD81,723 | 4.7 ± 0.9 × 106** | 0.74 ± 0.15 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 157 ± 25* |

Data are shown as mean ± SEM of three separate experiments each performed in duplicate.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001 compared with the values in the absence of an allosteric modulator; Student's t-test.

kon (k3) and koff (k4) of unlabelled A1 receptor agonists in the absence or presence of an allosteric modulator (PD81,723 or BC-1) were determined in [3H]-DPCPX (2.6 nM) competition association assays.

RT (residence time) = 1/koff.

Kinetic KD = koff/kon; kon (k3) and koff (k4) values of unlabelled antagonists were generated from [3H]-DPCPX (2.6 nM) competition association assays at 25°C.

Data simulations and assay validation for determining the bitopic ligands' binding kinetics in the competition association assay

Simulated data were collected by consecutively solving the differential equations in the Methods section (Equations 5–12), which mimic the binding of a radioligand in the absence or presence of a bitopic ligand (Supporting Information Tables S1–S4). Next, the binding kinetics of the bitopic ligand were analysed using two methods: (i) by subjecting the defined microscopic kinetic constants (Table 4, ‘input parameters’) into Equations 13 and 14 to obtain the theoretical macroscopic binding parameters (Table 4, ‘calculated parameters’) and (ii) by subjecting the simulated data into the model of competition association assay to obtain the ‘collected parameters’ in Table 6 (Supporting Information Fig. S1). In general, the binding kinetics analysed by using both methods correlate well with each other. The association rates of the bitopic ligands from the competition association assay are similar to the theoretical values in all four examples. For instance, the collected kon value in Example 2013 is 2.3 × 105 M−1·min−1, which correlates well with its corresponding theoretical kon value of 2.0 × 105 M−1·min−1. Likewise, the dissociation rate can be reliably determined by using the competition association assay. All collected/experimental koff values turned out to be within twofold difference from the corresponding calculated values. Thus, the competition association assay enables the determination of the binding kinetics of bitopic ligands.

Table 6.

Binding of the monovalent ligand ‘c’ (k+c = 1 × 107 M−1·min−1, k−c = 0.3 min−1 and [c] = 100 nM) was simulated during a time lapse of 50 min in the absence or presence of different concentrations of the bitopic ligands ‘ab’ (k+a = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−a = 1 min−1, k+b = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−b = 1 min−1 and [L] = 0.29 mM) with different cooperativity factors

| Example | Cooperativity factor | Calculated parametersa | Collected parametersb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kon (M−1·min−1) | koff (min−1) | kon (M−1·min−1) | koff (min−1) | ||

| 1 | αab = 10 | 2.0 × 105 | 0.0069 | 2.3 × 105 | 0.0046 |

| 2 | αab = 0.1 | 1.6 × 105 | 0.41 | 1.1 × 105 | 0.72 |

| 3 | α'ab = 10 | 1.9 × 105 | 0.0066 | 2.1 × 105 | 0.0039 |

| 4 | α'ab = 0.1 | 2.0 × 105 | 0.50 | 1.3 × 105 | 0.90 |

The ‘macroscopic’ kinetic binding parameters of the bitopic ligands were calculated using Equations 13 and 14 or by subjecting the simulated data (Supporting Information Tables S1–S4) into the competition association assay based on the theoretical framework by Motulsky and Mahan (1984).

The ‘macroscopic’ kinetic binding parameters of the bitopic ligands were calculated using Equations 13 and 14.

kon and koff values were determined by analysing the simulated data (Supporting Information Tables S1–S4) in the competition association model ‘kinetics of competitive binding’ (Motulsky and Mahan, 1984).

Discussion

In the present study, we examined the allosteric modulation of the adenosine A1 receptor from a kinetic perspective, focusing on the orthosteric ligand. It follows from Table 2 that the competition association assay (Motulsky and Mahan, 1984) can be applied to determine the binding kinetics of unlabelled orthosteric ligands in the presence of an allosteric modulator that could either modulate the binding of the radioligand (e.g. BC-1) or not (e.g. PD81,723). This confirms the general applicability of the assay to study GPCR allosterism. Two additional validation experiments were performed though to further prove the general applicability, especially in the case of examining orthosteric agonists, while using an antagonistic radioligand. Firstly, it was necessary to examine the effect of different agonist's concentrations on its occupancy of the two different receptor states (coupled to or uncoupled from the G protein) and the corresponding binding kinetics. Hence, we examined the GTP effect on the equilibrium affinity and binding kinetics of CCPA and NECA, while we used a radiolabelled antagonist, [3H]-DPCPX. We observed that the kinetics of CCPA was insensitive to the presence of 1 mM GTP (Table 4) in our system and its kinetic KD values correlated to the equilibrium affinity in the presence of GTP (141 nM). This convinced us that we could continue without applying GTP in our further kinetic assays. Secondly, we analysed the binding kinetics of CCPA at high or low concentrations, as the compound was shown to have two affinity sites in the equilibrium binding assay. One could reason that a different set of kinetic parameters might be obtained at high or low agonist concentrations, as the high and low affinity states will be occupied to different degrees. However, we did not observe significant variations when the agonist was tested at three different, single concentrations or by globally analysing them (Table 4). Of note, similar findings were observed for an agonist at the adenosine A2A receptor (Guo et al., 2012). Taken together, this suggested that the agonist's binding kinetics obtained from the competition association assay using the antagonist [3H]-DPCPX was predominantly from the G protein-uncoupled sites/states, at least on the adenosine receptors.

The competition association assay offers several, not yet fully realised advantages for the investigation of allosteric modulation. Firstly, it enables the measurement of the kinetic characteristics of a probe in an unlabelled form, expanding the availability of orthosteric ligands for probe-dependent investigations. Secondly, the method allows the determination of the complete range of binding kinetics. This includes the association rate, dissociation rate, residence time and the ‘kinetic KD’ for the ligand studied. These abundant details are very useful to interpret the dynamic interactions between the ligand and receptor, especially given that many allosteric modulators have the propensity to alter the dissociation rates of orthosteric ligands. For instance, upon the addition of PD81,723 or BC-1, the receptor-residence times (RT) of CCPA or NECA were prolonged. Such a change can be immediately captured in the competition association assay from the typical ‘overshoot’ pattern as in Figure 5, indicating a compound's slower dissociation process than the radioligand (Motulsky and Mahan, 1984). PD81,723 and other GPCR allosteric modulators are known to influence a probe's affinity by changing its dissociation rate (Bruns and Fergus, 1990; Bhattacharya and Linden, 1995; Lazareno and Birdsall, 1995; Gao et al., 2001; Bauer et al., 2012). Their effect on the association rates of orthosteric ligands, however, has been less investigated. Here, by using the competition association assay, we found that an allosteric modulator could also change an orthosteric ligand affinity by influencing its association rate. For NECA, the association rate increased by 3.3-fold upon the addition of 10 μM PD81,723, which, together with the 2.2-fold decrease in the dissociation rate, resulted in an overall 6.9-fold change in affinity. We also reaffirmed that the allosteric effect of both A1 receptor modulators was concentration-dependent, as evidenced by the concentration-dependent increase in the RT for CCPA (Table 5). Moreover, the kinetics of different orthosteric ligands were not equally altered, which reflects the specific feature of GPCR allosteric modulation, the so-called ‘probe-dependency’ (Christopoulos, 2002). For orthosteric ligands, such a phenomenon is not only limited to their affinity or potency, the parameters most often investigated for GPCR allosterism, but is also reflected in the less examined dissociation and association rate. As evidence, the association and/or dissociation rates for CCPA and NECAwere significantly changed upon the addition of 10 μM PD81,723, but not by LUF5834 (Table 5). Apparently, all these details of ligand–receptor interaction can be simultaneously obtained by using the competition association approach. It should be pointed out that the current assay has limited advantages when it comes to the quantification of parameters for the modulators, for instance, the cooperativity factor, α. To fully characterize the latter, the approach developed by Lazareno and Birdsall (1995) may be more suitable.

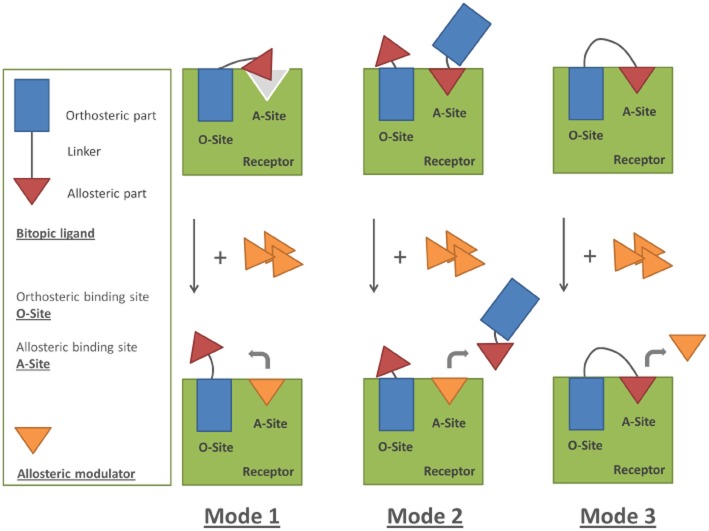

In the present study, we furthermore performed a competition association assay with bitopic ligands to study their kinetic behaviour. A bitopic ligand is a useful tool to study the molecular mechanism of allosteric modulation (Lane et al., 2013). However, interpretation of its binding can be very complex. Different bitopic ligands may display three divergent binding modes: the ligand can be bound to the allosteric site only, to the orthosteric site only or to both sites simultaneously if the length of the linker is optimal. Moreover, one receptor can be occupied by two bitopic ligands, that is, one to the allosteric site and the other to the orthosteric site (Steinfeld et al., 2007; Narlawar et al., 2010; Lane et al., 2013). A kinetic investigation of a bitopic ligand could add information to an affinity- or potency-based evaluation. Therefore, we selected three previously reported bitopic ligands (Narlawar et al., 2010), namely LUF6232, LUF6234 and LUF6258, and examined their binding kinetics in the present study. We found that the theoretically calculated macroscopic kinetics correlated well with the values that were determined by analysing the simulated data in the competition association assay (Table 6). Additionally, our kinetic KD values were generally in the same range as the Ki values reported by Narlawar et al. (2010), although their Ki of LUF6234 was slightly higher than we determined. Thus, the competition association assay enables sufficient quantification of the net changes of the macroscopic binding kinetics of bitopic ligands. Next, we observed that, because of the covalent link between the orthosteric and allosteric pharmacophores, the dissociation process of LUF6234 and LUF6258 was much slower than their orthosteric constituent, LUF5519, in the presence of PD81,723 (Table 7). Such phenomenon can be explained by the fact that a freshly dissociated pharmacophore is obliged to remain in ‘forced proximity’ to its cognate binding site as long as the tethered, companion pharmacophore is still bound. This favours its rebinding to that site, thereby significantly slowing down the net dissociation process (Vauquelin, 2013; Vauquelin and Charlton, 2013). To our knowledge, our present observation of the gained target RT of the bitopic ligand provides the first experimental evidence for such rebinding mechanism of low MW ligands. One could reason that such slow dissociation rates of LUF6234 and LUF6258 could occur via another mechanism where the bitopic ligand is bound to the orthosteric site and the allosteric portion may be close to, but not interacting with the allosteric site. If this would be the case, the bitopic ligand could flip between orthosteric and allosteric binding modes, while remaining in close proximity to or even occluding the orthosteric site and therefore extending its apparent RT. To distinguish between these two mechanisms, we also included the binding kinetics of another bitopic ligand, LUF6232, which has a four-carbon linker, that is, shorter than LUF6234. In comparison, the RT of LUF6232 was increased to a lesser extent than its analogues with a five- or nine-carbon linker. Specifically, its value (4.5 ± 1.3 min) was more close to the RT of the monovalent ligand LUF5519 or LUF7161 in the presence of 10 or 33 μM PD81,723. This result further confirmed that both the allosteric and orthosteric sites need to be occupied by, rather than being close to, the corresponding portion of the bitopic ligand to exert the synergistic effect of long receptor occupancy, and excluded the mechanism of increased RT by a bitopic ligand through ‘flipping’ between the two binding modes.

To further clarify mode of binding of bitopic ligands to the A1 receptor, we examined the effect of the addition of ‘external’ PD81,723 in studies with the bitopic ligand. In this way, the monovalent modulator should be able to occupy the allosteric site on the receptor preventing the rebinding of the freshly dissociated allosteric pharmacophore. In this sense, both association and dissociation of LUF6234 became faster compared with its kinetics in the absence of PD81,723, indicative of competition between the allosteric part of LUF6234 and the ‘free’ allosteric modulator at the A1 receptor allosteric binding site. Such binding mechanism can be illustrated in Mode 1 (Figure 7). On the contrary, the RT of a ligand that cannot simultaneously occupy both the allosteric and orthosteric binding site should be less affected upon the addition of the external monovalent modulator, like LUF6232 (Mode 2, Figure 7). Indeed, the dissociation rate of LUF6232 was unaffected upon the addition of 10 or 33 μM PD81,723. Interestingly, the dissociation rate of LUF6258 was also unaffected upon the addition of 10 or 33 μM PD81,723. Based upon this result alone, one could hypothesize that LUF6258's binding mode may fall into the same category as its four-carbon linker analogue, LUF6232 (i.e. Mode 2). However, this mode fails to explain LUF6258's long RT. Therefore, we reasoned that this unique phenomenon of LUF6258 binding was most likely due to the flexibility of its linker: it has more freedom of rotation and thus increased the likelihood that both pharmacophores could interact tightly with the receptor (Figure 7, Mode 3). In contrast, the shorter five-carbon linker might be able to bridge both allosteric and orthosteric sites simultaneously, yet in a non-optimal manner due to its short length and thus higher energy constraint (Figure 7, Mode 1).

Figure 7.

Proposed diagram of three distinct binding modes for the bitopic ligands in the absence or presence of further added allosteric modulator. Mode 1: the linker length of a bitopic ligand is sufficient to occupy both sites on the receptor, yet in a non-optimal manner. Mode 2: the linker length of a bitopic ligand is not sufficient to occupy both sites on the receptor. Two ligands could possibly bind to one receptor with either the orthosteric part to the ‘O-site’ or with the allosteric part to the ‘A-site’ on the receptor. Mode 3: the linker length of a bitopic is optimal to occupy both orthosteric and allosteric sites of the receptor. Upon the addition of excess allosteric modulator, the allosteric modulator can prevent the rebinding of the freshly dissociated allosteric pharmacophore in Mode 1 due to the bitopic ligand's less optimal binding pose or occupy the ‘A-site’ on the receptor and thus ‘displace’ the bitopic ligand binding to the receptor via its allosteric pharmacophore in Mode 2. In contrast, the binding of the bitopic ligand with optimal linker length (Mode 3) is less affected in the presence of the allosteric modulator.

Notably, our proposed binding modes of LUF6234 and LUF6258 expand on the conclusions previously drawn by Narlawar et al. (2010), where the authors suggested that the bitopic ligand with linker length of five (LUF6234) failed to completely occupy both allosteric site and orthosteric site, whereas the one with linker length of nine (LUF6258) was able to occupy both sites. This conclusion was based upon the hypothesis that if the linker is of sufficient length to allow simultaneous occupancy of the allosteric and orthosteric binding sites, the addition of further PD81,723 will have a minimal effect on the potency of the bitopic ligand, while for the bitopic ligand with insufficient linker length affinity will be significantly increased (Narlawar et al., 2010). Following this hypothesis, we would have reached the same conclusion if merely affinity was taken into consideration, as we also observed that LUF6234 displayed a strongly increased kinetic KD upon the addition of 10 μM PD81,723 (7.6-fold), while less so for LUF6258 (3.8-fold). However, it is also noteworthy from our study that both LUF6234 and LUF6258 displayed significantly increased receptor RTs compared to that of the monovalent ligand, LUF5519 or LUF7161, in the presence of PD81,723 (Table 7). Such a result strongly indicates that both allosteric and orthosteric sites on the A1 receptor were simultaneously occupied for both compounds, which appeared to induce a synergistic effect – greater than simply combining two monovalent ligands – on the global receptor conformation. If LUF6234's linker length had been insufficient to occupy both sites, it should have had a RT comparable to the monovalent LUF7161 or the bitopic ligand LUF6232 that has a shorter linker, which, in fact, is not the case for this bitopic ligand. Apparently, investigation of binding kinetics adds significantly to understanding the molecular mechanism of the binding of a bitopic ligand.

In summary, we have validated and shown the use of a competition association assay at the human adenosine A1 receptor to determine the allosteric modulation of the binding kinetics of different A1 receptor agonists. Our data suggest that the influence of an A1 receptor allosteric enhancer (positive allosteric modulator) on the binding kinetics of the orthosteric agonist is dependent upon the concentration of the allosteric modulator and the nature of the orthosteric ligand and that both the association and dissociation rates can be affected. Furthermore, we examined the binding kinetics of two bitopic ligands and investigated their binding mode. The relevance of the competition association assay for the binding kinetics of bitopic ligands was also explored by analysing a series of simulations and comparing the result to the theoretically determined kinetics. Taken together, the competition association assay enables accurate determination of the binding kinetics of an orthosteric ligand, whether radiolabelled or not, in the absence or presence of an allosteric modulator. We believe that this approach will have general applicability for the study of allosteric modulation at other GPCRs as well.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Julien Louvel and Mr Maris Vilums for helpful comments on the manuscript and Dr Thea Mulder-Krieger for skilled technical assistance. This project was financially supported by the Innovational Research Incentives Scheme of the Netherlands Research Organization (NWO; VENI-Grant 11188 to L. H.).

Glossary

- BC-1

(2-amino-4-((4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)piperazin-1-yl)methyl)thiophen-3-yl)(4-chlorophenyl)methanone

- CCPA

2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine

- CHAPS

3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate

- CHO-hA1R

Chinese hamster ovary cells stably expressing the human adenosine A1 receptor

- CPA

N6-cyclopentyladenosine

- DPCPX

1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine

- k1

the association rate constant of the radioligand

- k2

the dissociation rate constant of the radioligand

- k3

the association rate constant of the unlabelled ligand

- k4

the dissociation rate constant of the unlabelled ligand

- LUF5519

N6-(4-methoxyphenyl)adenosine

- LUF5834

2-amino-4-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-6-(1H-imidazol-2ylmethyl-sulfanyl)-pyridine-3,5-dicarbonitrile

- LUF6232

N6-[2-amino-3-(3,4-dichlorobenzoyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno-[2,3-c]pyridin-6-yl-4-butyloxy-4-phenyl]-adenosine

- LUF6234

N6-[2-amino-3-(3,4-dichlorobenzoyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno-[2,3-c]pyridin-6-yl-5-pentyloxy-4-phenyl]-adenosine

- LUF6258

N6-[2-amino-3-(3,4-dichlorobenzoyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[2,3-c]-pyridin-6-yl-9-nonyloxy-4-phenyl]-adenosine

- LUF7160

N6-(4-nonyloxyphenyl) adenosine

- LUF7161

N6-(4-pentyloxyphenyl)adenosine

- NECA

N-5′-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine

- PD81,723

(2-amino-4,5-dimethyl-3-thienyl)-[3-(trifluoromethyl)-phenyl]methanone

- RT

residence time

Author contributions

D. G. designed and conducted the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. S. N. V. conducted the experiments. A. M. conducted the experiments and analysed the data. J. P. D. V. synthesized the compounds and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. G. V. conducted the simulations, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. A. P. I. designed the experiments, assessed the results and wrote the manuscript. L. H. H. designed the experiments, assessed the results and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.12836

Competition association assay of a radioligand, ‘c’ (with k+c = 1 × 107 M-1·min-1, k−c = 0.3 min−1 and [c] = 100 nM), during a period of 50 min, either alone or in the presence of increasing concentrations of ‘ab’ (k+a = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−a = 1 min−1, k+b = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−b = 1 min−1 and [L] = 0.29 mM) with different cooperativity factors: (1) αab = 10; (2) αab = 0.1; (3) α'ab = 10; (4) α'ab = 0.1. Data input into this analysis were from Table S1 to S4 respectively.

Table S1 Data simulation of the binding of radioligand, ‘c’, during a period of 50 min, either alone or in the presence of increasing concentrations of the bitopic ligand, ‘ab’. The microscopic binding kinetics of the bitopic ligand ‘ab’ was defined as k+a = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−a = 1 min−1, k+b = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−b = 1 min−1 and [L] = 0.29 mM. The binding kinetics of the monovalent ligand ‘c’ was defined as k+c = 1 × 107 M−1·min−1, k−c = 0.3 min−1 and [c] = 100 nM. The cooperativity factors of ‘ab’ were set as αab = 10.

Table S2 Data simulation of the binding of radioligand, ‘c’, during a period of 50 min, either alone or in the presence of increasing concentrations of the bitopic ligand, ‘ab’. The microscopic binding kinetics of the bitopic ligand ‘ab’ was defined as k+a = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−a = 1 min−1, k+b = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−b = 1 min−1 and [L] = 0.29 mM. The binding kinetics of the monovalent ligand ‘c’ was defined as k+c = 1 × 107 M−1·min−1, k−c = 0.3 min−1 and [c] = 100 nM. The cooperativity factors of ‘ab’ were set as αab = 0.1.

Table S3 Data simulation of the binding of radioligand, ‘c’, during a period of 50 min, either alone or in the presence of increasing concentrations of the bitopic ligand, ‘ab’. The microscopic binding kinetics of the bitopic ligand ‘ab’ was defined as k+a = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−a = 1 min−1, k+b = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−b = 1 min−1 and [L] = 0.29 mM. The binding kinetics of the monovalent ligand ‘c’ was defined as k+c = 1 × 107 M−1·min−1, k−c = 0.3 min−1 and [c] = 100 nM. The cooperativity factors of ‘ab’ were set as α'ab = 10.

Table S4 Data simulation of the binding of radioligand, ‘c’, during a period of 50 min, either alone or in the presence of increasing concentrations of the bitopic ligand, ‘ab’. The microscopic binding kinetics of the bitopic ligand ‘ab’ was defined as k+a = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−a = 1 min−1, k+b = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−b = 1 min−1 and [L] = 0.29 mM. The binding kinetics of the monovalent ligand ‘c’ was defined as k+c = 1 × 107 M−1·min−1, k−c = 0.3 min−1 and [c] = 100 nM. The cooperativity factors of ‘ab’ were set as α'ab = 0.1.

References

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: G Protein-Coupled Receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1459–1581. doi: 10.1111/bph.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M, Chicca A, Tamborrini M, Eisen D, Lerner R, Lutz B, et al. Identification and quantification of a new family of peptide endocannabinoids (Pepcans) showing negative allosteric modulation at CB1 receptors. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:36944–36967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.382481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beukers MW, Chang LC, von Frijtag Drabbe Kunzel JK, Mulder-Krieger T, Spanjersberg RF, Brussee J, et al. New, non-adenosine, high-potency agonists for the human adenosine A2B receptor with an improved selectivity profile compared to the reference agonist N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine. J Med Chem. 2004;47:3707–3709. doi: 10.1021/jm049947s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S, Linden J. The allosteric enhancer, PD 81,723, stabilizes human A1 adenosine receptor coupling to G proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1265:15–21. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(94)00204-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns RF, Fergus JH. Allosteric enhancement of adenosine A1 receptor binding and function by 2-amino-3-benzoylthiophenes. Mol Pharmacol. 1990;38:939–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos A. Allosteric binding sites on cell-surface receptors: novel targets for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:198–210. doi: 10.1038/nrd746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos A, Kenakin T. G protein-coupled receptor allosterism and complexing. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:323–374. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland RA. Evaluation of enzyme inhibitors in drug discovery. A guide for medicinal chemists and pharmacologists. Methods Biochem Anal. 2005;46:1–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland RA, Pompliano DL, Meek TD. Drug-target residence time and its implications for lead optimization. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:730–739. doi: 10.1038/nrd2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie BJ, Christopoulos A, Scammells PJ. Development of M1 mAChR allosteric and bitopic ligands: prospective therapeutics for the treatment of cognitive deficits. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2013;4:1026–1048. doi: 10.1021/cn400086m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Amici M, Dallanoce C, Holzgrabe U, Trankle C, Mohr K. Allosteric ligands for G protein-coupled receptors: a novel strategy with attractive therapeutic opportunities. Med Res Rev. 2010;30:463–549. doi: 10.1002/med.20166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Linden J, Müller CE. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXI. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors – an update. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:1–34. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao ZG, Jacobson KA. Emerging adenosine receptor agonists. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2007;12:479–492. doi: 10.1517/14728214.12.3.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao ZG, Jacobson KA. Allosteric modulation and functional selectivity of G protein-coupled receptors. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2013;10:e237–e243. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao ZG, Kim SK, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA. Allosteric modulation of the adenosine family of receptors. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2005;5:545–553. doi: 10.2174/1389557054023242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao ZG, Van Muijlwijk-Koezen JE, Chen A, Muller CE, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA. Allosteric modulation of A3 adenosine receptors by a series of 3-(2-pyridinyl)isoquinoline derivatives. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:1057–1063. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göblyös A, IJzerman AP. Allosteric modulation of adenosine receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808:1309–1318. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory KJ, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A. Allosteric modulation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2007;5:157–167. doi: 10.2174/157015907781695946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D, Hillger JM, IJzerman AP, Heitman LH. Drug-target residence time-a case for G protein-coupled receptors. Med Res Rev. 2014;34:856–892. doi: 10.1002/med.21307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D, Mulder-Krieger T, IJzerman AP, Heitman LH. Functional efficacy of adenosine A2A receptor agonists is positively correlated to their receptor residence time. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166:1846–1859. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D, van Dorp EJ, Mulder-Krieger T, van Veldhoven JP, Brussee J, IJzerman AP, et al. Dual-point competition association assay: a fast and high-throughput kinetic screening method for assessing ligand-receptor binding kinetics. J Biomol Screen. 2013;18:309–320. doi: 10.1177/1087057112464776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keov P, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A. Allosteric modulation of G protein-coupled receptors: a pharmacological perspective. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostenis E, Mohr K. Two-point kinetic experiments to quantify allosteric effects on radioligand dissociation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1996;17:280–283. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(96)10034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane JR, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A. Bridging the gap: bitopic ligands of G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2013;34:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazareno S, Birdsall NJM. Detection, quantitation, and verification of allosteric interactions of agents with labeled and unlabeled ligands at G-protein-coupled receptors – interactions of strychnine and acetylcholine at muscarinic receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48:362–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse MJ, Klotz KN, Schwabe U, Cristalli G, Vittori S, Grifantini M. 2-Chloro-N-6-cyclopentyladenosine – a highly selective agonist at A1 adenosine receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1988;337:687–689. doi: 10.1007/BF00175797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May LT, Self TJ, Briddon SJ, Hill SJ. The effect of allosteric modulators on the kinetics of agonist-G protein-coupled receptor interactions in single living cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78:511–523. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.064493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melancon BJ, Hopkins CR, Wood MR, Emmitte KA, Niswender CM, Christopoulos A, et al. Allosteric modulation of seven transmembrane spanning receptors: theory, practice, and opportunities for central nervous system drug discovery. J Med Chem. 2012;55:1445–1464. doi: 10.1021/jm201139r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motulsky HJ, Mahan LC. The kinetics of competitive radioligand binding predicted by the law of mass action. Mol Pharmacol. 1984;25:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller CE. A1 adenosine receptors and their ligands: overview and recent developments. Farmaco. 2001;56:77–80. doi: 10.1016/s0014-827x(01)01005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller CE, Schiedel AC, Baqi Y. Allosteric modulators of rhodopsin-like G protein-coupled receptors: opportunities in drug development. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;135:292–315. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narlawar R, Lane JR, Doddareddy M, Lin J, Brussee J, IJzerman AP. Hybrid ortho/allosteric ligands for the adenosine A1 receptor. J Med Chem. 2010;53:3028–3037. doi: 10.1021/jm901252a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, et al. NC-IUPHAR. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert-driven knowledge base of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl Acids Res. 2014;42(Database Issue):D1098–D1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romagnoli R, Baraldi PG, Carrion MD, Cara CL, Cruz-Lopez O, Iaconinoto MA, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 2-amino-3-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-4-[N-(substituted) piperazin-1-yl]thiophenes as potent allosteric enhancers of the A1 adenosine receptor. J Med Chem. 2008;51:5875–5879. doi: 10.1021/jm800586p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeld T, Mammen M, Smith JAM, Wilson RD, Jasper JR. A novel multivalent ligand that bridges the allosteric and orthosteric binding sites of the M2 muscarinic receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:291–302. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.033746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vauquelin G. Simplified models for heterobivalent ligand binding: when are they applicable and which are the factors that affect their target residence time. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2013;386:949–962. doi: 10.1007/s00210-013-0881-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vauquelin G, Bricca G, Van Liefde I. Avidity and positive allosteric modulation/cooperativity act hand in hand to increase the residence time of bivalent receptor ligands. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2013:1–14. doi: 10.1111/fcp.12052. doi: 10.1111/fcp.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vauquelin G, Charlton SJ. Exploring avidity: understanding the potential gains in functional affinity and target residence time of bivalent and heterobivalent ligands. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168:1771–1785. doi: 10.1111/bph.12106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CI, Lewis RJ. Emerging opportunities for allosteric modulation of G-protein coupled receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Monsma F. Binding kinetics and mechanism of action: toward the discovery and development of better and best in class drugs. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2010;5:1023–1029. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2010.520700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Competition association assay of a radioligand, ‘c’ (with k+c = 1 × 107 M-1·min-1, k−c = 0.3 min−1 and [c] = 100 nM), during a period of 50 min, either alone or in the presence of increasing concentrations of ‘ab’ (k+a = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−a = 1 min−1, k+b = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−b = 1 min−1 and [L] = 0.29 mM) with different cooperativity factors: (1) αab = 10; (2) αab = 0.1; (3) α'ab = 10; (4) α'ab = 0.1. Data input into this analysis were from Table S1 to S4 respectively.

Table S1 Data simulation of the binding of radioligand, ‘c’, during a period of 50 min, either alone or in the presence of increasing concentrations of the bitopic ligand, ‘ab’. The microscopic binding kinetics of the bitopic ligand ‘ab’ was defined as k+a = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−a = 1 min−1, k+b = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−b = 1 min−1 and [L] = 0.29 mM. The binding kinetics of the monovalent ligand ‘c’ was defined as k+c = 1 × 107 M−1·min−1, k−c = 0.3 min−1 and [c] = 100 nM. The cooperativity factors of ‘ab’ were set as αab = 10.

Table S2 Data simulation of the binding of radioligand, ‘c’, during a period of 50 min, either alone or in the presence of increasing concentrations of the bitopic ligand, ‘ab’. The microscopic binding kinetics of the bitopic ligand ‘ab’ was defined as k+a = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−a = 1 min−1, k+b = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−b = 1 min−1 and [L] = 0.29 mM. The binding kinetics of the monovalent ligand ‘c’ was defined as k+c = 1 × 107 M−1·min−1, k−c = 0.3 min−1 and [c] = 100 nM. The cooperativity factors of ‘ab’ were set as αab = 0.1.

Table S3 Data simulation of the binding of radioligand, ‘c’, during a period of 50 min, either alone or in the presence of increasing concentrations of the bitopic ligand, ‘ab’. The microscopic binding kinetics of the bitopic ligand ‘ab’ was defined as k+a = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−a = 1 min−1, k+b = 1 × 105 M−1·min−1, k−b = 1 min−1 and [L] = 0.29 mM. The binding kinetics of the monovalent ligand ‘c’ was defined as k+c = 1 × 107 M−1·min−1, k−c = 0.3 min−1 and [c] = 100 nM. The cooperativity factors of ‘ab’ were set as α'ab = 10.