Abstract

Dectin-2 is a C-type lectin receptor that recognizes high mannose polysaccharides. Cryptococcus neoformans, a yeast-form fungal pathogen, is rich in polysaccharides in its cell wall and capsule. In the present study, we analyzed the role of Dectin-2 in the host defense against C. neoformans infection. In Dectin-2 gene-disrupted (knockout) (Dectin-2KO) mice, the clearance of this fungus and the inflammatory response, as shown by histological analysis and accumulation of leukocytes in infected lungs, were comparable to those in wild-type (WT) mice. The production of type 2 helper T (Th2) cytokines in lungs was higher in Dectin-2KO mice than in WT mice after infection, whereas there was no difference in the levels of production of Th1, Th17, and proinflammatory cytokines between these mice. Mucin production was significantly increased in Dectin-2KO mice, and this increase was reversed by administration of anti-interleukin 4 (IL-4) monoclonal antibody (MAb). The levels of expression of β1-defensin, cathelicidin, surfactant protein A (Sp-A), and Sp-D in infected lungs were comparable between these mice. In in vitro experiments, IL-12p40 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) production and expression of CD86 and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells and alveolar macrophages were completely abrogated in Dectin-2KO mice. Finally, the disrupted lysates of C. neoformans, but not of whole yeast cells, activated Dectin-2-triggered signaling in an assay with nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT)-green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter cells expressing this receptor. These results suggest that Dectin-2 may oppose the Th2 response and IL-4-dependent mucin production in the lungs after infection with C. neoformans, and it may not be required for the production of Th1, Th17, and proinflammatory cytokines or for clearance of this fungal pathogen.

INTRODUCTION

Cryptococcus neoformans, an opportunistic yeast-form fungal pathogen, infects the host via an airborne route (1). This fungus resists killing induced by macrophages, which enables its intracellular growth within these cells (2). The host defense against cryptococcal infection is mediated by the cellular immune response (3), and the type 1 helper T (Th1) response plays a critical role in eradicating this infection, whereas Th2 cytokines counterregulate this response (4). Mice with a genetic disruption of Th1-related cytokines, such as gamma interferon (IFN-γ), interleukin 12 (IL-12), and IL-18, are highly susceptible to cryptococcal infection compared to wild-type (WT) control mice (5–7). In contrast, mice lacking Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13, are more resistant to this infection than WT mice (8–10). For this reason, individuals with an impaired cellular immune response, such as hematological malignancy and AIDS, suffer from a severe C. neoformans infection that leads to disseminated infection in the central nervous system (11, 12).

When microorganisms infect the host, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are recognized by the host immune cells via their pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which initiates the host defense response (13). C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), a PRR-recognizing PAMP composed of polysaccharides, have garnered the attention of many investigators in the study of host defense against fungal infection (14). Recently, we demonstrated that caspase-associated recruitment domain 9 (CARD9), a common adaptor molecule delivering signals triggered by CLRs, plays a critical role in the host defense against infection with C. neoformans (15), suggesting the possible involvement of CLRs. In our earlier study (16), the genetic defect of Dectin-1, a representative CLR recognizing β1,3-glucan, did not influence the clearance of C. neoformans, and the inflammatory response during infection with this fungal pathogen suggests that other CLRs may be involved in this response.

Dectin-2 is expressed by a variety of myeloid cells, such as macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs), and its expression is enhanced during the inflammatory response (17, 18). Dectin-2 is involved in the recognition of high mannose polysaccharides, and its triggering leads to the production of various cytokines and chemokines, including proinflammatory Th1, Th17, and also Th2 cytokines (17, 18). Dectin-2 is known to recognize a variety of fungal pathogens, including Candida albicans, Aspergillus fumigatus, and noncapsular C. neoformans (19, 20), and indeed to play a critical role in the host defense against infection with C. albicans through inducing the Th17-mediated immune response (21). Like other fungal microorganisms, C. neoformans is rich in high-mannose polysaccharides, such as glucuronoxylomannan, galactoxylomannan, and mannoprotein, in its cell wall (22), which suggests that Dectin-2 may contribute to the recognition of this fungus by host immune cells. Thus, in the present study, we addressed the question of how dectin-2 is involved in the host defense immune response to infection with C. neoformans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

This study was performed in strict accordance with the Fundamental Guidelines for Proper Conduct of Animal Experiment and Related Activities in Academic Research Institutions under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan, 2006. All experimental procedures involving animals followed the Regulations for Animal Experiments and Related Activities at Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan, and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Tohoku University (approval numbers 22 IDOU-108, 2011 IDOU-86, 2012 IDOU-124, and 2013 IDOU-257). All experiments were performed with the animals under anesthesia, and all efforts were made to minimize the suffering of the animals.

Mice.

Dectin-2 gene-disrupted (knockout [KO]) mice were generated and established as described previously (21), and they were backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice for 7 generations. Littermate mice were used as wild-type (WT) control mice. Male or female mice at 6 to 8 weeks of age were used in the experiments. All mice were kept under specific-pathogen-free conditions at the Institute for Animal Experimentation, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine.

Microorganisms.

A serotype D strain of C. neoformans, designated B3501 (provided by Kwong Chung, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), was used. In some experiments, C. albicans (ATCC 18804) was used. The fungal microorganisms were cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA; Eiken, Tokyo, Japan) plates for 2 to 3 days before use. Mice were anesthetized using an intraperitoneal injection of 70 mg pentobarbital/kg of body weight (Abbott Laboratory, North Chicago, IL, USA) and restrained on a small board. Live C. neoformans (1 × 106 cells or 1 × 105 cells in some experiments) was inoculated at 50 μl into the trachea of each mouse using a 24-gauge catheter (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan).

Enumeration of viable C. neoformans cells.

Mice were sacrificed on days 7, 14, and 28 after infection. The lungs were dissected carefully, excised, and then homogenized separately in 5 ml of distilled water by teasing them with a stainless-steel mesh at room temperature. The homogenates, diluted appropriately with distilled water, were inoculated at 100 μl on PDA plates and cultured for 2 to 3 days before the resulting colonies were counted.

Histological examination.

The lung specimens obtained from mice were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H-E) or periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain using standard staining procedures at the Biomedical Research Core, Animal Pathology Platform, of Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine. Mucin production was estimated on the PAS-stained sections as the proportion of mucin-producing bronchi relative to total bronchi. The mucin-producing bronchi were classified into three categories: –, mucin-negative bronchi; +, bronchi with mucin production in 0 to 50% of bronchoepithelial cells; and ++, bronchi with mucin production in 50 to 100% of bronchoepithelial cells.

Cytokine assay.

Concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-12p40, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), IL-17A, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-10, and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) in the lung homogenates and culture supernatants were measured using the appropriate enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (BioLegend for IL-1β, IL-6, IFN-γ, IL-17A, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10; eBioscience [San Diego, CA, USA] for IL-13 and TGF-β; BD Bioscience [Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA] for TNF-α and IL-12p40).

Extraction of RNA and quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from the infected lungs using Isogen (Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan), and the first-strand cDNA was synthesized using a PrimeScript first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was performed in a volume of 20 μl using gene-specific primers and FastStart Essential DNA Green Master (Roche Applied Science, Branford, CT, USA) in a LightCycler Nano system (Roche Applied Science). The primer sequences for amplification are shown in Table 1. Reaction efficiency with each primer set was determined using standard amplifications. Target gene expression levels and that of hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) as a reference gene were calculated for each sample using the reaction efficiency. The results were analyzed using a relative quantification procedure and are illustrated as expression relative to HPRT expression.

TABLE 1.

Primers for real-time PCR

| Targeta | Sense primer (5′–3′) | Antisense primer (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ | ACTGCCACGGCACAGTCATT | TCACCATCCTTTTGCCAGTTCCT |

| IL-4 | ACGAGGTCACAGGAGAAGGGA | TTGGAAGCCCTACAGACGAGC |

| IL-5 | GCAATGGAAGGCTGAGGCTG | GGGTATGTGATCCTCCTGCGTC |

| IL-13 | CTCTTGCTTGCCTTGGTGGTCT | ACTCCATACCATGCTGCCGTTG |

| IL-17A | AACCGTTCCACGTCACCCTG | GTCCAGCTTTCCCTCCGCAT |

| MUC5AC | ACACCGCTCTGATGTTCCTCACC | ATGTCCTGGGTTGAAGGCTCGT |

| Cathelicidin | GACACCAATCTCTACCGTCTCCT | TGCCTTGCCACATACAGTCTCCT |

| β1-Defensin | GAGCATAAAGGACGAGCGA | CATTACTCAGGACCAGGCAGA |

| Sp-A | TCGGAGGCAGACATCCACA | GCCAGCAACAACAGTCAAGAAGAG |

| Sp-D | TCAGTACCCAACACCTGCACCC | TCTCACCCCGTGGACCTTCTCT |

| HPRT | GCTTCCTCCTCAGACCGCTT | TCGCTAATCACGACGCTGGG |

HPRT, hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase; Sp-, surfactant protein.

Preparation of lung leukocytes.

Pulmonary intraparenchymal leukocytes were prepared as previously described (23). Briefly, the chest of each mouse was opened and the lung vascular bed was flushed by injecting 3 ml of chilled physiological saline into the right ventricle. The lungs were then excised and washed in physiological saline. The lungs, teased apart with a 40-μm cell strainer (BD Falcon, Bedford, MA, USA), were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium (Nipro, Osaka, Japan) with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS; BioWest, Nuaillé, France), 100 U/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 10 mM HEPES, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 2 mM l-glutamine containing 20 U/ml collagenase and 1 μg/ml DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After incubation for 60 min at 37°C with vigorous shaking, the tissue fragments and the majority of dead cells were removed by passing the cells through the 40-μm cell strainer. After centrifugation, the cell pellet was resuspended in 4 ml of 40% (vol/vol) Percoll (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) and layered onto 4 ml of 80% (vol/vol) Percoll. After centrifugation at 600 × g for 20 min at 15°C, the cells at the interface were collected, washed three times, and counted using a hemocytometer. The obtained cells were centrifuged onto a glass slide at 110 × g for 3 min using Cytofuge-2 (StatSpin Inc., Norwood, MA, USA), stained with Diff-Quick (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan), and observed under a microscope. The number of leukocyte fractions was estimated by multiplying the total leukocyte number by the proportion of each fraction in 200 cells.

Flow cytometry.

The lung leukocytes were cultured at 1 × 106/ml with 5 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), 500 ng/ml ionomycin, and 2 nM monensin (Sigma-Aldrich) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS (BioWest, Nuaillé, France) for 4 h. The cells were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% FCS and 0.1% sodium azide and then stained with allophycocyanin (APC)–anti-CD3ε monoclonal antibody (MAb) (clone 145-2C11; BioLegend), phycoerythrin (PE)–anti-CD4 MAb (clone GK1.5; BioLegend), and allophycocyanin cyanine 7 (APC/Cy7)–anti-CD8a MAb (clone 53-6.7; BioLegend). After being washed twice, the cells were incubated in the presence of Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Bioscience), washed twice in BD Perm/Wash solution (BD Bioscience), and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–anti-IFN-γ or IL-17A MAb (clone XMG1.2 for IFN-γ [BioLegend] and clone TC11-18H10.1 for IL-17A [BioLegend]) and Alexa Fluor 488–anti-IL-4 (clone 11B11; BioLegend). Isotype-matched IgG was used for control staining. The stained cells were analyzed using a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Bioscience). Data were collected from 20,000 to 30,000 individual cells using forward-scatter and side-scatter parameters to set a gate on the lymphocyte or myeloid cell population. The number of particular cells was estimated by multiplying the lymphocyte or myeloid cell number, calculated as mentioned above, by the proportion of each subset.

Administration of anti-IL-4 MAb.

Anti-IL-4 MAb was purified from culture supernatants of hybridoma (clones 11B11) using a protein G column kit (Kierkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). To neutralize the biological activity of IL-4, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 200 μg of MAb against this cytokine on day 1 before and days 0, 3, and 7 after infection.

Preparation and culture of DCs.

Dendritic cells (DCs) were prepared from bone marrow (BM) cells as described by Lutz and coworkers (24). Briefly, BM cells from mice were cultured at 2 × 105/ml in 10 ml RPMI 1640 medium (Nipro, Osaka, Japan) supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) containing 20 ng/ml murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; Wako, Osaka, Japan). On day 3, 10 ml of the same medium was added, followed by a half change with the GM-CSF-containing culture medium on day 6. On day 8 or 9, nonadherent cells were collected and used as BM DCs. The obtained cells were cultured with C. neoformans or lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The culture supernatants were measured for synthesis of IL-12p40 and TNF-α by ELISA. The cells were stained with FITC–anti-CD11c (clone N418; eBioscience), Pacific Blue–anti-CD86 (clone GL1; BioLegend), and PE–anti-I-A/I-E MAbs (clone M5/114.15.2; BioLegend), and the expression of CD86 and MHC class II on CD11c+ cells was analyzed using a flow cytometer.

Preparation of alveolar macrophages.

The chests of WT and Dectin-2KO mice were opened, and their tracheae were cannulated (22-gauge intravenous [i.v.] catheter). PBS (1 ml) was infused intratracheally and withdrawn. This procedure was performed three times. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluids were centrifuged at 450 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the pellets were collected and suspended in the culture medium. The cells contained more than 95% alveolar macrophages. The obtained cells were cultured at 1 × 106/ml with C. neoformans or LPS for 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Dectin-2–NFAT–GFP reporter assay.

T cell hybridoma 2B4 was transfected with the NFAT-GFP construct prepared by fusing three tandem NFAT-binding sites with enhanced GFP cDNA (25). This cell line was transfected with Dectin-2 and FcRγ genes, and the same cell line but lacking Dectin-2 was used as a control. These cells were stimulated for 20 h at 2.5 × 105/ml with C. neoformans or its disrupted lysates, which had been prepared using Multi-Beads Shocker (Yasui Kikai, Osaka, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the expression of GFP was analyzed on the CD3+ cells, but not on dead 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD)-stained cells, by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed using JMP Pro 10.0.2 software (SAS Institute Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD). Differences between groups were examined for statistical significance using Welch's t test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

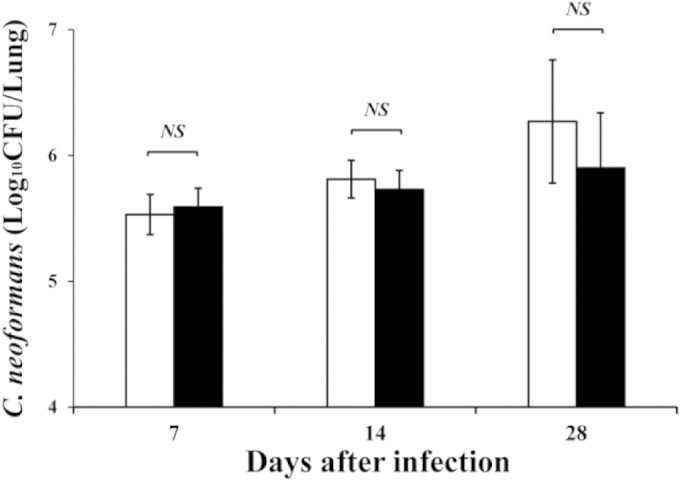

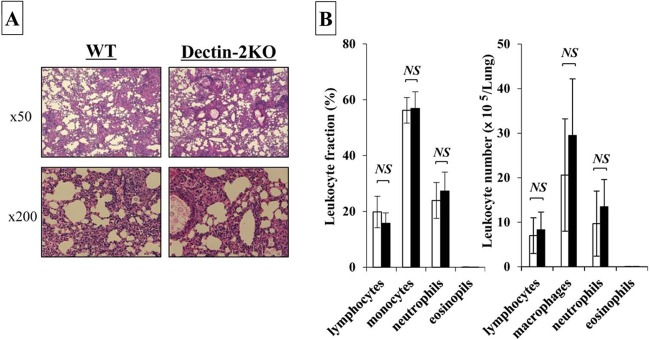

Effect of Dectin-2 deficiency on the clearance of C. neoformans and the inflammatory response in lungs.

To elucidate the effect of Dectin-2 deficiency on the host defense against cryptococcal infection, the clinical courses between WT and Dectin-2KO mice after infection with C. neoformans were compared. None of these mice died during the observation period (up to day 56). Next, the numbers of live colonies in lungs between these mice on days 7, 14, and 28 postinfection were compared. As shown in Fig. 1, there was no significant difference in the numbers of live C. neoformans cells at any time point between WT and Dectin-2KO mice. The live colonies of C. neoformans were not detected in the brains of both mouse strains on day 28 postinfection (data not shown). In addition, similar results were obtained when mice were infected with a lower dose of C. neoformans, 1 × 105 CFU/mouse (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). We then investigated how Dectin-2 deficiency affected the inflammatory response in the lungs after cryptococcal infection. Histological analysis did not find any apparent difference in the HE-stained lung sections on day 14 after infection (Fig. 2A). In addition, we examined the leukocyte fractions obtained from the lungs on day 14 after infection. The total numbers of leukocytes were not significantly different between WT and Dectin-2KO mice (3.7 × 105 ± 2.3 × 105 versus 5.1 × 105 ± 2.2 × 105 [5 mice each]), and the lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and eosinophils were found in comparable proportions and counts in these mice (Fig. 2B and C). These results indicated that Dectin-2 was not required for the clearance of C. neoformans and the inflammatory response caused by this infection in the lungs.

FIG 1.

C. neoformans infection in Dectin-2KO mice. WT and Dectin-2KO mice were infected intratracheally with C. neoformans. The numbers of live colonies in the lungs were counted on days 7, 14, and 28 after infection. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of results for five mice. Experiments were repeated twice, with similar results. NS, not significant.

FIG 2.

Effect of Dectin-2 deficiency on the inflammatory response in lungs. WT and Dectin-2KO mice were infected intratracheally with C. neoformans. (A) Sections of the lungs on day 14 postinfection were stained with H-E and observed under a light microscope at ×50 or ×200 magnification. Representative pictures from the five to six mice are shown. Experiments were repeated twice, with similar results. (B) The lung leukocytes prepared on day 7 postinfection were stained with Diff-Quick and observed under a light microscope. The amount of cells in each leukocyte fraction was counted. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of results for five mice. NS, not significant.

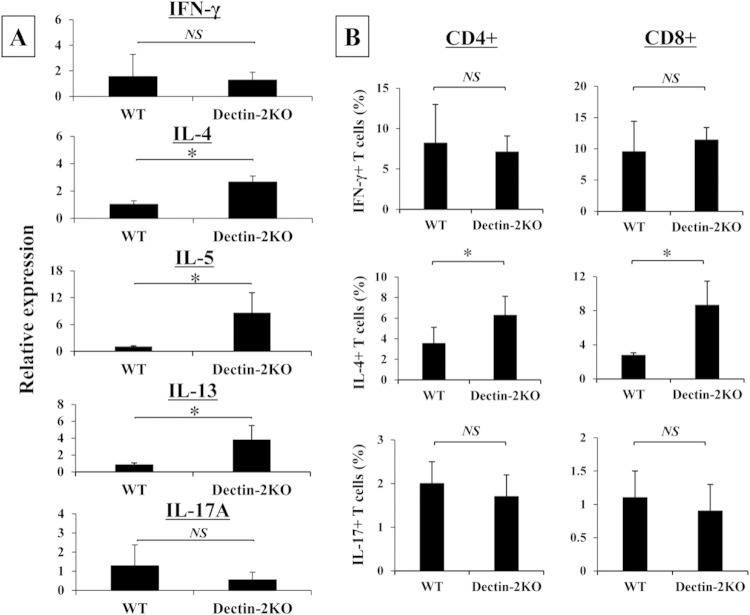

Increased production of Th2 cytokines in Dectin-2KO mice after infection with C. neoformans.

In the next series of experiments, the effect of Dectin-2 deficiency on the cytokine response to C. neoformans was examined by measuring the concentrations of various cytokines in the lung homogenates on days 0, 1, 3, 7, 14, and 21 postinfection. As shown in Table 2, proinflammatory cytokines (such as IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-12p40) and Th1 and Th17 cytokines (such as IFN-γ and IL-17A, respectively) were not significantly influenced by Dectin-2 deficiency compared to those in WT mice, except for IL-1β on day 3, IL-6 on day 14, and IL-17A on day 14; IL-1β was reduced, and IL-6 and IL-17A were increased. In contrast, the production of Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, was significantly increased on days 7 and 21, days 3, 7, and 14, and days 3, 7, 14, and 21, respectively. Similarly, production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10, was significantly increased on days 3, 7, and 14. We also examined IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17A mRNA expression on day 7 postinfection. As shown in Fig. 3A, the expression of Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, was significantly higher in Dectin-2KO mice than that in WT mice, whereas IFN-γ and IL-17A were expressed at equivalent levels in these mice. Additionally, we examined the intracellular expression of these cytokines in lung T cells on day 7, and expression of IL-4, but not of IFN-γ and IL-17A, was significantly increased in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3B).

TABLE 2.

Effect of Dectin-2 deficiency on cytokine production in lungs

| Cytokine | Production (pg/g lung) in indicated mice ona: |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 |

Day 1 |

Day 3 |

Day 7 |

Day 14 |

Day 21 |

|||||||

| WT | KO | WT | KO | WT | KO | WT | KO | WT | KO | WT | KO | |

| IL-1β | 9,262 ± 1,605 | 9,007 ± 1,270 | 8,849 ± 3,009 | 9,939 ± 3,027 | 11,313 ± 1,032 | 8,411 ± 2,192* | 5,051 ± 577 | 5,218 ± 727 | 6,003 ± 1,933 | 6,715 ± 1,349 | 9,256 ± 1,456 | 8,092 ± 1,357 |

| IL-6 | 2,714 ± 694 | 2,606 ± 302 | 2,939 ± 1,277 | 2,826 ± 1,429 | 4,243 ± 2,004 | 2,574 ± 1,083 | 663 ± 213 | 867 ± 174 | 1,163 ± 255 | 1,695 ± 402* | 2,468 ± 665 | 2,711 ± 360 |

| TNF-α | 570 ± 79 | 568 ± 73 | 559 ± 100 | 724 ± 269 | 1,624 ± 1,023 | 1,366 ± 547 | 277 ± 67 | 362 ± 115 | 334 ± 83 | 358 ± 79 | 338 ± 100 | 318 ± 93 |

| IL-12p40 | 2,088 ± 226 | 1,829 ± 202 | 3,400 ± 574 | 3,126 ± 308 | 23,193 ± 2,822 | 25,590 ± 3,577 | 4,530 ± 713 | 3,632 ± 1,216 | 2,334 ± 196 | 2,127 ± 136 | 6,198 ± 2,230 | 6,415 ± 2,914 |

| IFN-γ | 1,168 ± 342 | 1,121 ± 252 | 10,389 ± 2,303 | 9,539 ± 691 | 14,323 ± 4,695 | 15,319 ± 3,378 | 5,214 ± 538 | 6,234 ± 674 | 7,715 ± 1,611 | 7,132 ± 534 | 2,853 ± 954 | 3,182 ± 377 |

| IL-17A | 2,522 ± 437 | 2,617 ± 294 | 2,303 ± 616 | 2,831 ± 993 | 1,965 ± 399 | 1,582 ± 384 | 1,391 ± 536 | 1,166 ± 287 | 941 ± 151 | 1,232 ± 213* | 1,749 ± 548 | 1,754 ± 327 |

| IL-4 | 106 ± 20 | 86 ± 21 | 176 ± 89 | 139 ± 45 | 170 ± 79 | 226 ± 69 | 287 ± 49 | 1,307 ± 534* | 631 ± 488 | 848 ± 328 | 182 ± 80 | 312 ± 49* |

| IL-5 | 215 ± 25 | 215 ± 19 | 3,011 ± 482 | 3,050 ± 280 | 1,731 ± 163 | 2,644 ± 782* | 1,295 ± 99 | 1,542 ± 195* | 2,465 ± 366 | 3,593 ± 637* | 130 ± 40 | 126 ± 17 |

| IL-13 | 486 ± 77 | 449 ± 44 | 417 ± 96 | 439 ± 132 | 198 ± 22 | 276 ± 73* | 257 ± 54 | 547 ± 208* | 396 ± 81 | 748 ± 178* | 595 ± 168 | 882 ± 113* |

| IL-10 | 4,423 ± 756 | 4,593 ± 684 | 3,423 ± 1,187 | 4,554 ± 1,376 | 737 ± 116 | 1,724 ± 820* | 641 ± 100 | 1,137 ± 356* | 1,222 ± 286 | 2,071 ± 540* | 1,966 ± 908 | 1,829 ± 214 |

| TGF-β | 8,519 ± 2,058 | 7,512 ± 2,060 | 8,597 ± 2,343 | 10,242 ± 3,376 | 9,287 ± 2,391 | 10,007 ± 3,611 | 5,192 ± 2,407 | 4,584 ± 2,997 | 7,784 ± 2,296 | 6,272 ± 3,362 | 4,889 ± 1,375 | 4,432 ± 2,355 |

Cytokine production (pg/g lung) at the indicated time intervals after C. neoformans infection. Data shown are means ± SD of results for four to seven mice. Experiments were repeated twice with similar results. *, P < 0.05, compared to value for WT mice.

FIG 3.

Effect of Dectin-2 deficiency on the T cell immune response. WT and Dectin-2KO mice were infected intratracheally with C. neoformans. (A) IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-17A mRNA expression in the lungs was measured on day 7 after infection. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of results for three to four mice. Experiments were repeated twice, with similar results. NS, not significant; *, P < 0.05. (B) The lung leukocytes were prepared on day 7 postinfection. IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17A expression in CD3+ CD4+ or CD8+ T cells was analyzed using flow cytometry. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of results for three to five mice. Experiments were repeated twice, with similar results. NS, not significant; *, P < 0.05.

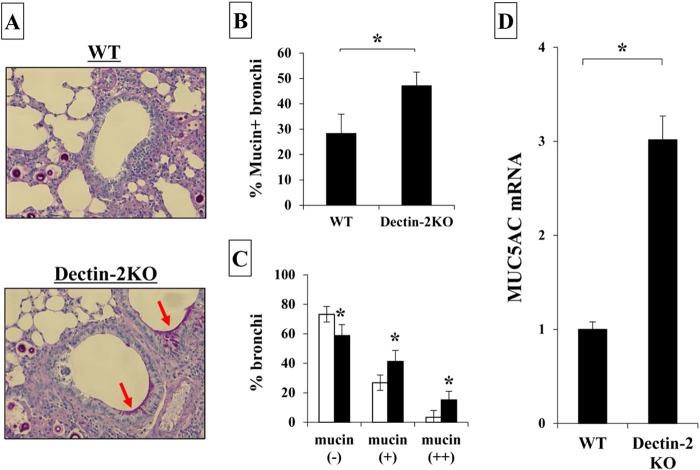

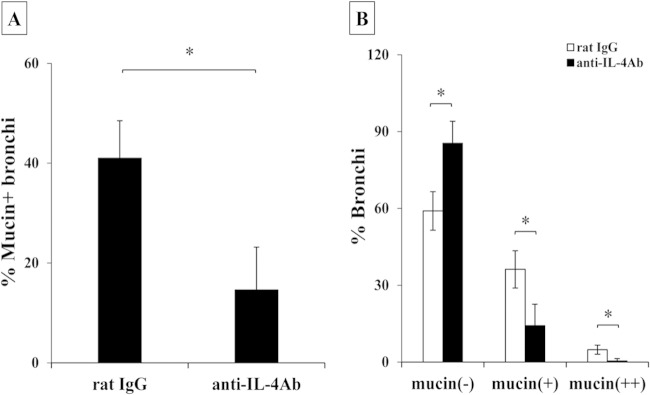

Increased production of mucin in Dectin-2KO mice after infection with C. neoformans.

In previous studies, Zuyderduyn and coworkers reported that mucin production was enhanced by IL-4 under conditions of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection (26). In addition, recently, Grahnert et al. demonstrated that mucin production was ameliorated in the lungs of IL-4RKO mice compared to that in WT mice after infection with C. neoformans (27). We next examined the expression of mucin detected by PAS staining in the lung sections on day 14 after cryptococcal infection. As shown in Fig. 4A to C, numbers of bronchi expressing mucin were significantly increased and numbers of mucin-negative bronchi were significantly decreased in Dectin-2KO mice compared with those detected in WT mice. Mucin is composed of various core proteins, including MUC5AC, a major one secreted from bronchial epithelial cells (28). Therefore, we examined the effect of Dectin-2 deficiency on MUC5AC expression in the lungs. As shown in Fig. 4D, this expression was significantly increased in the lungs of Dectin-2KO mice compared with that in WT mice. In addition, we addressed whether IL-4 was involved in the increased production of mucin in Dectin-2 KO mice by testing the effect of neutralizing anti-IL-4 MAb. Administration of this MAb led to significant reduction in the mucin production observed in Dectin-2KO mice (Fig. 5A and B). However, the same treatment did not show any influence on the clearance of C. neoformans in lungs on day 14 postinfection (data not shown). These results indicated that Dectin-2 deficiency led to the increase of mucin production in the lungs after cryptococcal infection, which suggested that Dectin-2 may be involved in the regulation of the Th2-mediated response and mucosal surface barrier in the lungs.

FIG 4.

Mucin production after infection with C. neoformans. WT and Dectin-2KO mice were infected intratracheally with C. neoformans. (A) Sections of the lungs on day 14 postinfection were stained with PAS and observed under a light microscope at ×200 magnification. Arrows indicate the mucin secreted by bronchoepithelial cells. Representative pictures from the five to six mice are shown. The proportion of mucin-producing bronchi (B) and the classification of mucin-producing bronchi (C) were determined. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of results for five to six mice. Experiments were repeated twice, with similar results. *, P < 0.05. (D) MUC5AC mRNA expression in the lungs was measured on day 7 after infection. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of results for three to four mice. Experiments were repeated twice, with similar results. *, P < 0.05.

FIG 5.

Effect of anti-IL-4 MAb on mucin production. Dectin-2KO mice were infected intratracheally with C. neoformans. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with anti-IL-4 MAb and control rat IgG. Sections of the lungs on day 14 postinfection were stained with H-E or PAS and observed under a light microscope. The proportion of mucin-producing bronchi (A) and the classification of mucin-producing bronchi (B) were determined. Each column represents the mean ± SD of results for five mice. *, P < 0.05.

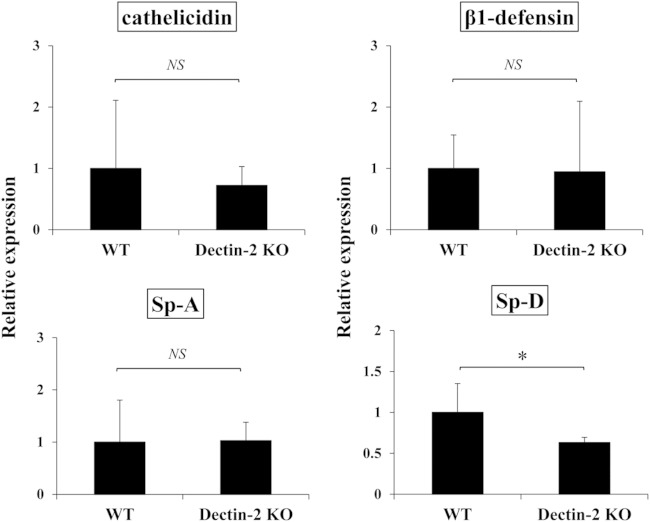

Effect of Dectin-2 deficiency on the humoral host defense factors.

Mucous layers on the bronchoepithelial cells contain various humoral host defense factors, such as β-defensin, cathelicidin, and collectins (collagen-containing C-type lectins), which show antimicrobial and proinflammatory activities (29–31). Surfactant protein A (Sp-A) and Sp-D host factors belonging to collectins are reported to bind to C. neoformans, and Sp-D promotes the phagocytosis of this fungus by macrophages (32, 33). We examined whether these host defense factors were affected by Dectin-2 deficiency during infection with C. neoformans. As shown in Fig. 6, there was no significant difference in the levels of expression of β1-defensin, cathelicidin, and Sp-A in the lungs of WT and Dectin-2KO mice 7 days after infection, although the Sp-D level was significantly lower in Dectin-2KO mice.

FIG 6.

Effect of Dectin-2 deficiency on antimicrobial peptides and surfactant proteins. Cathelicidin, β1-defensin, Sp-A, and Sp-D mRNA expression in the lungs was measured on day 7 after infection. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of results for three to four mice. Experiments were repeated twice, with similar results. NS, not significant; *, P < 0.05.

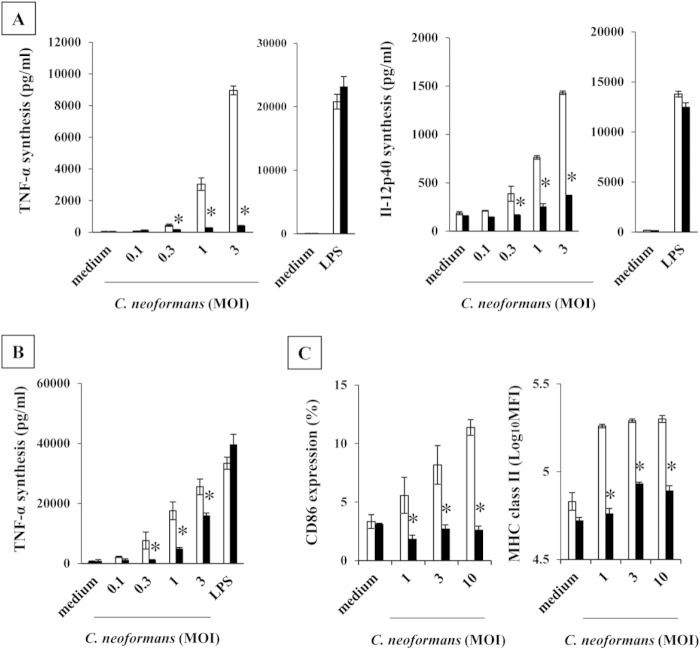

Reduced production of TNF-α and IL-12p40 by BM DCs and alveolar macrophages in Dectin-2KO mice.

We examined how Dectin-2 deficiency affected in vitro proinflammatory cytokine production by BM DCs and alveolar macrophages and expression of the maturation markers CD86 and MHC class II by BM DCs upon stimulation with C. neoformans. As shown in Fig. 7A and B, TNF-α and IL-12p40 production by BM DCs and TNF-α production by alveolar macrophages were strongly suppressed in Dectin-2KO mice compared to production levels in WT mice when these cells were stimulated with C. neoformans. IL-12p40 was not detected in the culture supernatants of alveolar cells stimulated with C. neoformans. Similar results were obtained in the expression of CD86 and MHC class II (Fig. 7C). These results suggested that Dectin-2 may be involved in the recognition of this fungal pathogen by DCs and macrophages.

FIG 7.

Production of proinflammatory cytokines by BM DCs and alveolar macrophages in Dectin-2KO mice. (A, C) BM DCs were prepared from WT and Dectin-2KO mice and stimulated with the indicated doses of C. neoformans or LPS for 24 h. IL-12p40 and TNF-α production in the culture supernatants (A) and cell surface expression of CD86 and MHC class II (C) were analyzed. MHC class II expression was expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (Log10MFI). (B) Alveolar macrophages were prepared from WT and Dectin-2KO mice and stimulated with the indicated doses of C. neoformans or LPS for 24 h, and production of TNF-α was measured. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of results for triplicate cultures. Experiments were repeated twice, with similar results. MOI, multiplicity of infection. *, P < 0.05.

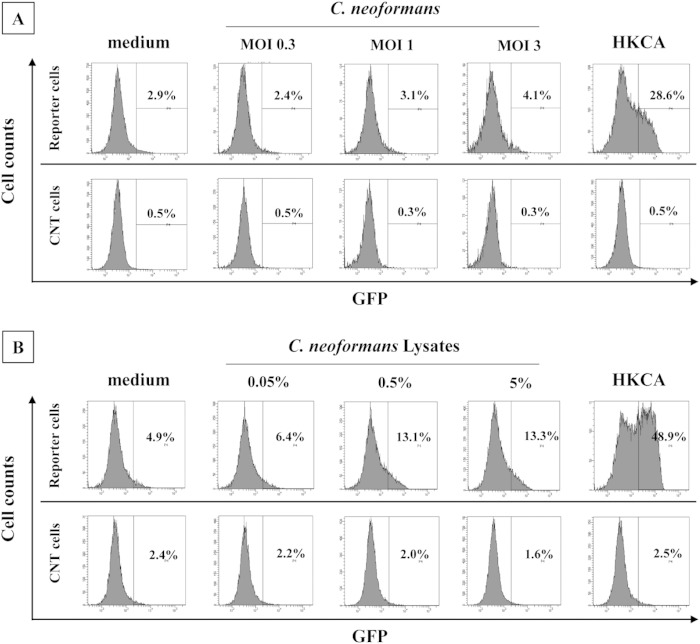

Activation of a Dectin-2-triggered signal by C. neoformans.

We examined whether C. neoformans directly triggered an activation signal via Dectin-2 using an NFAT-GFP reporter assay. As shown in Fig. 8A, whole C. neoformans yeast cells did not induce GFP expression by the reporter cells, whereas heat-killed C. albicans (HKCA) caused this activation. To address the possibility that Dectin-2 ligand may not be expressed on their surfaces, we examined whether disrupted C. neoformans lysates activated the reporter cells. As shown in Fig. 8B, the disrupted lysates induced GFP expression by the reporter cells, although this activity was not as high as that of HKCA. In contrast, the control cells lacking Dectin-2 did not show activation of the GFP gene by any stimulation.

FIG 8.

Dectin-2-NFAT-GFP reporter assay. The NFAT-GFP reporter cells expressing Dectin-2 or control cells were cultured with C. neoformans (A) or the disrupted lysates (B), and the expression of GFP was analyzed using a flow cytometer. Heat-killed C. albicans (HKCA) was used as a positive control. Representative data from three independent experiments are shown. MOI, multiplicity of infection.

DISCUSSION

Major findings in the present study are the following: (i) levels of clearance of C. neoformans in the lungs were almost equivalent in Dectin-2KO mice and WT mice; (ii) there was no apparent difference in the inflammatory responses in the infected lungs of these mice; (iii) production of Th2 cytokines, but not Th1, Th17, and proinflammatory cytokines, after infection was significantly increased in Dectin-2KO mice compared to that in WT mice; (iv) mucin and MUC5AC production in infected lungs was higher in Dectin-2KO mice than in WT mice; (v) increased mucin production was reversed by administration of anti-IL-4 MAb to Dectin-2KO mice; (vi) the levels of expression of β1-defensin, cathelicidin, Sp-A, and Sp-D in infected lungs were comparable between these mice; (vii) TNF-α and IL-12p40 production by BM DCs and alveolar macrophages and CD86 and MHC class II expression by BM DCs were mostly abrogated in Dectin-2KO mice compared to those in WT mice; and (viii) disrupted C. neoformans lysates, but not whole yeast cells, induced the activation signal triggered by Dectin-2 in an NFAT-GFP reporter assay. These results suggest that Dectin-2 may play a role in the host response during infection with C. neoformans.

In in vivo experiments, C. neoformans clearances and the inflammatory responses, as shown by the histological analysis and analysis of the accumulated leukocytes in infected lungs, were almost comparable between WT and Dectin-2KO mice, which suggests that Dectin-2 may not be required for host defense against this infection. In contrast, Dectin-2KO mice were more susceptible to infection with C. albicans than WT mice, as shown by the shortened survival and attenuated clearance of fungal microorganisms in the kidney, and this reduced host resistance was due to impairment in the appropriate host immune response (21). Similar results were reported for C. glabrata infection (34). In host defense against candida infection, neutrophils play a central role (35), and IL-17A is an important cytokine for the appropriate immune response (36). Consistently with this notion, in these studies with Candida spp., the Th17 response was ameliorated under conditions lacking Dectin-2. In the present study, Th1 cytokine production and inducible NO synthase expression (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) were not hampered in Dectin-2KO mice during infection with C. neoformans. These results were consistent with the data showing no impairment in the clearance of C. neoformans from these mice, because the Th1 response and NO production are required for the host defense against this fungus (4, 37). In addition, levels of IL-17A production were equivalent in WT and Dectin-2KO mice during this infection, which is in contrast to what occurred during infection with Candida spp., although the role of the Th17 response in the host defense against C. neoformans seems limited (38, 39).

Dectin-2KO mice showed increases in their production of Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, but not Th1 and Th17 cytokines, after infection with C. neoformans. Previously, Barrett and coworkers demonstrated that Dectin-2 is an important recognition receptor of house dust mites for inducing the Th2-type immune response through the production of cysteinyl leukotriene (40, 41). These previous findings were obtained in an allergic-disease model, and a similar mechanism may exist during cryptococcal infection. Although it remains to be elucidated how the Th2 response was promoted under Dectin-2-deficient conditions in our model, the production of Th2 cytokines was increased in the adaptive immune phase on days 7 and 14, and both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressed IL-4 within their cytoplasm on day 7 after infection with C. neoformans. This suggests that Th2 differentiation is promoted in Dectin-2KO mice. For Th2 cell differentiation, IL-4 is required during the innate immune phase (42), and innate immune cells, such as NKT cells, are thought to be the source of IL-4 production (43). In our unpublished data, there was no significant difference between WT and Dectin-2KO mice in IL-4 expression by NKT cells, a potent lymphocyte subset that synthesizes IL-4 (44). Other innate immune cells may contribute to the early production of this cytokine.

C. neoformans resists macrophage killing, which enables it to grow within these phagocytes (2). Therefore, the cell-mediated immune response promoted by Th1 cytokines is essential for the host defense against this fungus, and Th2 cytokines suppress the protective Th1 response (3–10). In Dectin-2KO mice, Th2 cytokine production was enhanced after infection with C. neoformans, but the Th1 response and clearance of this fungal pathogen were not affected, suggesting that the increased Th2 response may not be enough to ameliorate the host defense against this infection. On the other hand, mucin expression in infected lungs was promoted under conditions lacking Dectin-2, which was reversed by administration of neutralizing anti-IL-4 MAb. In agreement with these results, Zuyderduyn and coworkers previously demonstrated that Th2 cytokines were involved in the elimination of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by bronchoepithelial cells through inducing the production of mucin and antimicrobial peptides (26). In addition, Grahnert et al. recently reported that IL-4RαKO mice showed an attenuated host defense to C. neoformans infection through reduced mucin production in the lungs (27). Taken together with these findings, Dectin-2 may have an impact on host defense against cryptococcal infection through regulating IL-4-dependent mucin production by bronchoepithelial cells, although an effect on the production of antimicrobial peptides was not found in our study.

In in vitro experiments, alveolar macrophages and BM DCs almost completely lost their ability to produce TNF-α and IL-12p40 and to increase the expression of CD86 and MHC class II upon stimulation with C. neoformans, suggesting the existence of a certain ligand for Dectin-2 in this fungus. However, unexpectedly, whole C. neoformans yeast cells did not induce the activation of Dectin-2-expressing NFAT-GFP reporter cells. We addressed another possibility, namely, that the putative Dectin-2 ligand may not be expressed on the surfaces of, but rather inside, yeast cells. In agreement with this possibility, disrupted C. neoformans lysates triggered the activation signal via Dectin-2, and Dectin-2 did not bind to whole C. neoformans yeast cells in a binding assay using Dectin-2–Fc fusion protein (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In an earlier study by McGreal and coworkers (20), Dectin-2–Fc fusion protein bound to an acapsular strain of C. neoformans, Cap67, but not to the capsular strain, B3501, used in the current study, suggesting that this acapsular strain may trigger the activation signal by Dectin-2. However, whole yeast cells of the Cap67 strain did not induce GFP expression by the reporter cells, although its lysates showed this activation (data not shown). In addition, Dectin-2 fused with the Fc portion of human immunoglobulin (Dectin-2–Fc) did not bind to the acapsular strain (Cap67), which is a result similar to that for the capsular strain (B3501) (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). It is currently not clear why the results in these two studies showed a difference in levels of binding of Dectin-2–Fc fusion protein to the acapsular C. neoformans strain.

Thus, the current results suggest that a certain ligand that is not expressed on the surface of C. neoformans may be detected by Dectin-2 and may play a role in the host immune response to this fungal pathogen. However, even though this possibility exists, it is not known how the internal ligand accesses Dectin-2 through the capsule. To address this issue, it is necessary to define the Dectin-2 ligand in this fungal pathogen. An explanation for the discrepant results between the in vitro and in vivo experiments remains unclear. A compensatory mechanism may operate to activate the critical Th1-mediated immune response in place of the Dectin-2-mediated pathway. Recently, Viriyakosol and coworkers reported a similar discrepancy between in vitro and in vivo experiments in a fungal infection, in which in vitro production of proinflammatory cytokines by macrophages stimulated with Coccidioides immitis was reduced in Dectin-2KO mice, whereas the clearance of this fungal pathogen in the lungs and spleen was comparable to that in WT mice (45).

In our recent study, mice lacking CARD9, a common adapter molecule in signaling via CLRs, including Dectin-2, were highly susceptible to infection with C. neoformans, which was associated with the amelioration of early IFN-γ production (15). This was consistent with the possibility that Dectin-2 is involved in the host defense against this fungus. However, in contrast to CARD9KO mice, Dectin-2KO mice were resistant to this infection, with no impairment of IFN-γ production, but the Th2 response and IL-4-dependent mucin production were promoted. These distinct results between CARD9KO and Dectin-2KO mice suggest that the immune response during C. neoformans infection may be modified by signals via other CLRs besides Dectin-2. There are CLRs, including Dectin-1 and Mincle, besides Dectin-2 that use CARD9 as a common adaptor molecule to transduce the activation signal (46). Our previous study showed that, among these receptors, Dectin-1 was not likely to be involved in this response because its deficiency disturbed neither the Th1-mediated immune response nor C. neoformans clearance (16). There is currently no information on the role of Mincle in host defense to this fungal pathogen.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the absence of Dectin-2 led to an acceleration of the Th2 response and IL-4-dependent mucin production but did not affect the proinflammatory response, Th1 and Th17 cytokine production, or C. neoformans clearance in infected lungs. These results suggested that Dectin-2 may be involved in triggering a negative signal for the production of Th2 cytokines and mucin and that it may be involved in the recognition of C. neoformans for this response. Thus, the current study has important implications for understanding the precise mechanism of the host defense against this infection. However, there are many issues to be solved. For example, C. neoformans used in this study was serotype D, not serotype A, the latter of which is more common in AIDS patients (47). Because the carbohydrates on serotypes A and D are different, the current findings may not apply to serotype A. Thus, further investigation is necessary for a better understanding of the innate immune response during infection with C. neoformans.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Shiho Yoneya for her assistance in conducting the NFAT-GFP reporter assay.

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (23390263) and a Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research (24659477) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan and by grants (Research on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases [H22-SHINKOU-IPPAN-008 and H25-SHINKOU-IPPAN-006]) from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan.

We have no financial conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.02835-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Perfect JR, Casadevall A. 2002. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 16:837–874. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5520(02)00036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldmesser M, Tucker S, Casadevall A. 2001. Intracellular parasitism of macrophages by Cryptococcus neoformans. Trends Microbiol 9:273–278. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(01)02035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim TS, Murphy JW. 1980. Transfer of immunity to cryptococcosis by T-enriched splenic lymphocytes from Cryptococcus neoformans-sensitized mice. Infect Immun 30:5–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koguchi Y, Kawakami K. 2002. Cryptococcal infection and Th1-Th2 cytokine balance. Int Rev Immunol 21:423–438. doi: 10.1080/08830180213274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuan RR, Casadevall A, Oh J, Scharff MD. 1997. T cells cooperate with passive antibody to modify Cryptococcus neoformans infection in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:2483–2488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decken K, Köhler G, Palmer-Lehmann K, Wunderlin A, Mattner F, Magram J, Gately MK, Alber G. 1998. Interleukin-12 is essential for a protective Th1 response in mice infected with Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun 66:4994–5000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawakami K, Koguchi Y, Qureshi MH, Miyazato A, Yara S, Kinjo Y, Iwakura Y, Takeda K, Akira S, Kurimoto M, Saito A. 2000. IL-18 contributes to host resistance against infection with Cryptococcus neoformans in mice with defective IL-12 synthesis through induction of IFN-γ production by NK cells. J Immunol 165:941–947. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blackstock R, Murphy JW. 2004. Role of interleukin-4 in resistance to Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 30:109–117. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0156OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blackstock R, Buchanan KL, Adesina AM, Murphy JW. 1999. Differential regulation of immune responses by highly and weakly virulent Cryptococcus neoformans isolates. Infect Immun 67:3601–3609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Müller U, Stenzel W, Köhler G, Werner C, Polte T, Hansen G, Schutzen N, Straubinger RK, Blessing M, Ackenzie AN, Brombacher F, Alber G. 2007. IL-13 induces disease-promoting type 2 cytokines, alternatively activated macrophages and allergic inflammation during pulmonary infection of mice with Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol 179:5367–5377. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunha BA. 2001. Central nervous system infections in the compromised host: a diagnostic approach. Infect Dis Clin North Am 15:567–590. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5520(05)70160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarvis JN, Harrison TS. 2007. HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis. AIDS 21:2119–2129. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282a4a64d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. 2003. Toll-like receptors. Annu Rev Immunol 21:335–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willment JA, Brown GD. 2008. C-type lectin receptors in antifungal immunity. Trends Microbiol 16:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamamoto H, Nakamura Y, Sato K, Takahashi Y, Nomura T, Miyasaka T, Ishii K, Hara H, Yamamoto N, Kanno E, Iwakura Y, Kawakami K. 2014. Defect of CARD9 leads to impaired accumulation of IFN-γ-producing memory-phenotype T cells in lungs and increased susceptibility to pulmonary infection with Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun 82:1606–1615. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01089-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura K, Kinjo T, Saijo S, Miyazato A, Adachi Y, Ohno N, Fujita J, Kaku M, Iwakura Y, Kawakami K. 2007. Dectin-1 is not required for the host defense to Cryptococcus neoformans. Microbiol Immunol 51:1115–1119. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2007.tb04007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saijo S, Iwakura Y. 2011. Dectin-1 and Dectin-2 in innate immunity against fungi. Int Immunol 23:467–472. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxr046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kerscher B, Willment JA, Brown GD. 2013. The Dectin-2 family of C-type lectin-like receptors: an update. Int Immunol 25:271–277. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxt006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato K, Yang XL, Yudate T, Chung JS, Wu J, Luby-Phelps K, Kimberly RP, Underhill D, Cruz PD Jr, Ariizumi K. 2006. Dectin-2 is a pattern recognition receptor for fungi that couples with the Fc receptor gamma chain to induce innate immune responses. J Biol Chem 281:38854–38866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606542200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGreal EP, Rosas M, Brown GD, Zamze S, Wong SY, Gordon S, Martinez-Pomares L, Taylor PR. 2006. The carbohydrate-recognition domain of Dectin-2 is a C-type lectin with specificity for high mannose. Glycobiology 16:422–430. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saijo S, Ikeda S, Yamabe K, Kakuta S, Ishigame H, Akitsu A, Fujikado N, Kusaka T, Kubo S, Chung SH, Komatsu R, Miura N, Adachi Y, Ohno N, Shibuya K, Yamamoto N, Kawakami K, Yamasaki S, Saito T, Akira S, Iwakura Y. 2010. Dectin-2 recognition of alpha-mannans and induction of Th17 cell differentiation is essential for host defense against Candida albicans. Immunity 32:681–691. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cherniak R, Sundstrom JB. 1994. Polysaccharide antigens of the capsule of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun 62:1507–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawakami K, Kohno S, Morikawa N, Kadota J, Saito A, Hara K. 1994. Activation of macrophages and expansion of specific T lymphocytes in the lungs of mice intratracheally inoculated with Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Exp Immunol 96:230–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lutz MB, Kukutsch N, Ogilvie AL, Rössner S, Koch F, Romani N, Schuler G. 1999. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J Immunol Methods 223:77–92. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(98)00204-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohtsuka M, Arase H, Takeuchi A, Yamasaki S, Shiina R, Suenaga T, Sakurai D, Yokosuka T, Arase N, Iwashima M, Kitamura T, Moriya H, Saito T. 2004. NFAM1, an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif-bearing molecule that regulates B cell development and signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:8126–8131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401119101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zuyderduyn S, Ninaber DK, Schrumpf JA, van Sterkenburg MA, Verhoosel RM, Prins FA, van Wetering S, Rabe KF, Hiemstra PS. 2011. IL-4 and IL-13 exposure during mucociliary differentiation of bronchial epithelial cells increases antimicrobial activity and expression of antimicrobial peptides. Respir Res 12:59. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grahnert A, Richter T, Piehler D, Eschke M, Schulze B, Müller U, Protschka M, Köhler G, Sabat R, Brombacher F, Alber G. 2014. IL-4 receptor-alpha-dependent control of Cryptococcus neoformans in the early phase of pulmonary infection. PLoS One 9:e87341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thornton DJ, Rousseau K, McGuckin MA. 2008. Structure and function of the polymeric mucins in airways mucus. Annu Rev Physiol 70:459–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Risso A. 2000. Leukocyte antimicrobial peptides: multifunctional effector molecules of innate immunity. J Leukoc Biol 68:785–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang D, Biragyn A, Hoover DM, Lubkowski J, Oppenheim JJ. 2004. Multiple roles of antimicrobial defensins, cathelicidins, and eosinophil-derived neurotoxin in host defense. Annu Rev Immunol 22:181–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuroki Y, Takahashi M, Nishitani C. 2007. Pulmonary collectins in innate immunity of the lung. Cell Microbiol 9:1871–1879. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geunes-Boyer S, Oliver TN, Janbon G, Lodge JK, Heitman J, Perfect JR, Wright JR. 2009. Surfactant protein D increases phagocytosis of hypocapsular Cryptococcus neoformans by murine macrophages and enhances fungal survival. Infect Immun 77:2783–2794. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00088-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walenkamp AM, Verheul AF, Scharringa J, Hoepelman IM. 1999. Pulmonary surfactant protein A binds to Cryptococcus neoformans without promoting phagocytosis. Eur J Clin Invest 29:83–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1999.00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ifrim DC, Bain JM, Reid DM, Oosting M, Verschueren I, Gow NA, van Krieken JH, Brown GD, Kullberg BJ, Joosten LA, van der Meer JW, Koentgen F, Erwig LP, Quintin J, Netea MG. 2014. Role of Dectin-2 for host defense against systemic infection with Candida glabrata. Infect Immun 82:1064–1073. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01189-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kullberg BJ, Netea MG, Vonk AG, van der Meer JW. 1999. Modulation of neutrophil function in host defense against disseminated Candida albicans infection in mice. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 26:299–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hernández-Santos N, Gaffen SL. 2012. Th17 cells in immunity to Candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe 11:425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rossi GR, Cervi LA, García MM, Chiapello LS, Sastre DA, Masih DT. 1999. Involvement of nitric oxide in protecting mechanism during experimental cryptococcosis. Clin Immunol 90:256–265. doi: 10.1006/clim.1998.4639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hardison SE, Wozniak KL, Kolls JK, Wormley FL Jr. 2010. Interleukin-17 is not required for classical macrophage activation in a pulmonary mouse model of Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Infect Immun 78:5341–5351. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00845-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wozniak KL, Hardison SE, Kolls JK, Wormley FL. 2011. Role of IL-17A on resolution of pulmonary C. neoformans infection. PLoS One 6:e17204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barrett NA, Maekawa A, Rahman OM, Austen KF, Kanaoka Y. 2009. Dectin-2 recognition of house dust mite triggers cysteinyl leukotriene generation by dendritic cells. J Immunol 182:1119–1128. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barrett NA, Rahman OM, Fernandez JM, Parsons MW, Xing W, Austen KF, Kanaoka Y. 2011. Dectin-2 mediates Th2 immunity through the generation of cysteinyl leukotrienes. J Exp Med 208:593–604. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swain SL, Weinberg AD, English M, Huston G. 1990. IL-4 directs the development of Th2-like helper effectors. J Immunol 145:3796–3806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshimoto T, Bendelac A, Watson C, Hu-Li J, Paul WE. 1995. Role of NK1.1+ T cells in a TH2 response and in immunoglobulin E production. Science 270:1845–1847. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Godfrey DI, Hammond KJ, Poulton LD, Smyth MJ, Baxter AG. 2000. NKT cells: facts, functions and fallacies. Immunol Today 21:573–583. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(00)01735-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Viriyakosol S, Jimenez Mdel P, Saijo S, Fierer J. 2014. Neither Dectin-2 nor the mannose receptor is required for resistance to Coccidioides immitis in mice. Infect Immun 82:1147–1156. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01355-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Drummond RA, Saijo S, Iwakura Y, Brown GD. 2011. The role of Syk/CARD9 coupled C-type lectins in antifungal immunity. Eur J Immunol 41:276–281. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kwon-Chung KJ, Fraser JA, Doering TL, Wang Z, Janbon G, Idnurm A, Bahn YS. 2014. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii, the etiologic agents of cryptococcosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 4:a019760. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.