Summary

How are skeletal tissues derived from skeletal stem cells? Here, we map bone, cartilage and stromal development from a population of highly pure, post-natal skeletal stem cells (mouse Skeletal Stem Cell, mSSC) to its downstream progenitors of bone, cartilage and stromal tissue. We then investigated the transcriptome of the stem/progenitor cells for unique gene expression patterns that would indicate potential regulators of mSSC lineage commitment. We demonstrate that mSSC niche factors can be potent inducers of osteogenesis, and several specific combinations of recombinant mSSC niche factors can activate mSSC genetic programs in situ, even in non-skeletal tissues, resulting in de novo formation of cartilage or bone and bone marrow stroma. Inducing mSSC formation with soluble factors and subsequently regulating the mSSC niche to specify its differentiation towards bone, cartilage, or stromal cells could represent a paradigm shift in the therapeutic regeneration of skeletal tissues.

Introduction

Stem cell regulation in the skeletal system, as compared to the hematopoietic system, remains relatively unexplored. Pioneering studies by Friedenstein et al. established the presence of colony forming skeletogenic cells, but only recently have efforts begun to identify and isolate bone, cartilage, and stromal progenitors for rigorous functional characterization (Bianco, 2011; Chan et al., 2013; Friedenstein et al., 1987; Mendez-Ferrer et al., 2010; Morrison et al., 2006; Park et al., 2012). In addition, the bone marrow is a favored site of prostate and breast cancer metastasis and the characteristics of the bone stroma supporting metastatic stem cell niches are largely uncharted. Another important challenge in tissue regeneration is the limited capacity to (re)generate cartilage, which is deficient in many diseases (e.g., osteoarthritis, connective tissue disorders) (Burr, 2004; Kilic et al., 2014).

We hypothesized that the skeletal system follows a program similar to that of hematopoiesis, with a multipotent stem cell generating various lineages in a niche that regulates differentiation. Thus we sought to: (i) identify a multipotent skeletal stem cell and map its relationship to its lineage committed progeny; and (ii) identify cells and factors in the skeletal stem cell niche that regulate its activity.

Results

I. Identification of the skeletal stem cell, its progeny, and their lineage relationships

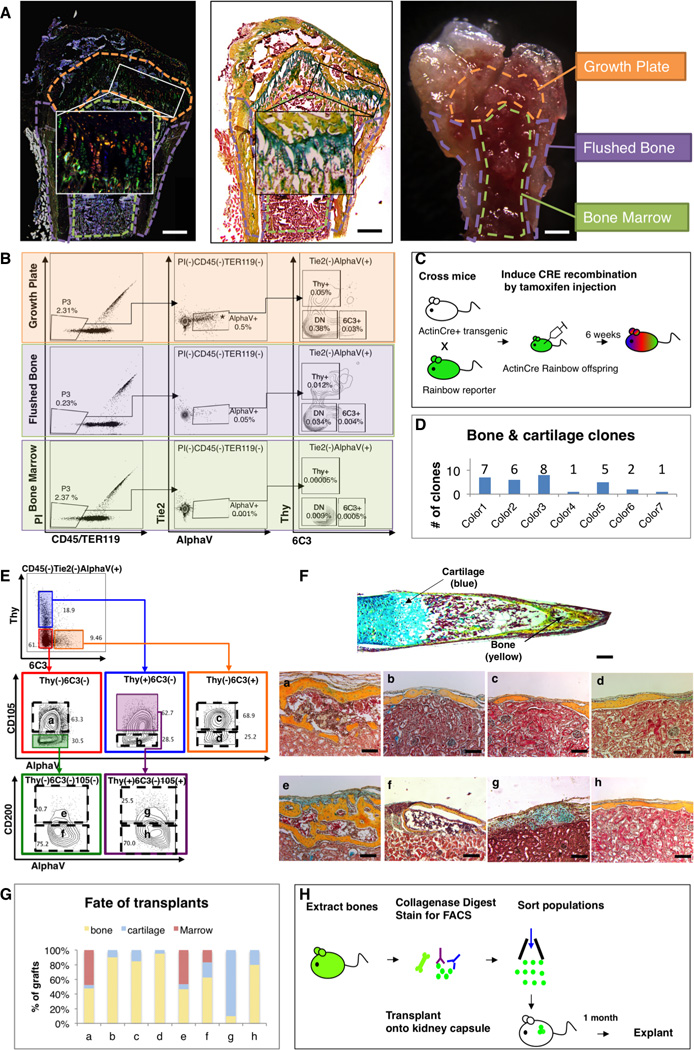

Bone and cartilage are derived from clonal, lineage-restricted progenitors

We used a “Rainbow mouse” (Ueno and Weissman, 2006) model to evaluate clonal-lineage relationships in vivo to determine whether mesenchymal tissues in bone—including stroma, fat, bone, cartilage, and muscle—share a common progenitor (Rinkevich et al., 2011)(See Experimental Methods). To visualize clonal patterns within all tissues, we crossed ‘Rainbow’ mice with mice harboring a tamoxifen(TMX)-inducible ubiquitously expressed Cre under the actin promoter (Actin-Cre-ERT) (Figure 1C). Six weeks after this recombinase activation, clonal regions could be detected as uniformly labeled areas of a distinct color (Supplementary Figure 1A, B). Using this system, we observe clonal regions in the bone, particularly at the growth plate, that encompass bone, cartilage, and stromal tissue, but not hematopoietic, adipose, or muscle tissue at all timepoints studied (Figure 1A, C–D, Supplementary Figure 1D). These data indicate that bone, cartilage, and stromal tissue are clonally derived in vivo from lineage-restricted stem and progenitor cells that do not also give rise to muscle and fat, at least at the timepoints examined (Supplementary Figure 1).

Fig 1. Bone and cartilage are derived from clonal, lineage-restricted progenitors.

(A) Micrographs: 6-week old Rainbow Actin-Cre-ERT mouse femur, following TMX-induction at P3, shows clonal expansion at the growth plate. Fluorescent microscopy (left), pentachrome stain (middle), and dissection microscope (right). Scale bar: 500µM. Representative of 10 replicates.

(B) FACS plots: cells isolated from three different parts of the femur illustrate that [AlphaV+] is most prevalent in the growth plate (uppermost horizontal panel in the middle) (p<0.001, ANOVA, n=3). DN = double negative, negative for Thy and 6C3 surface expression.

(C) Scheme of experiment: Actin-Cre-ERT transgenic mouse was crossed with rainbow reporter gene mouse. Cre recombination of offspring was induced by TMX induction on E15, P3 and postnatal week 6. Bones were harvested 6 weeks post induction.

(D) Graphic representation illustrating different numbers of clones present, which span the bone and cartilage. Representative of sections with 10 mice. See also Figure S1.

(E) FACS gating strategy for isolation of eight distinct skeletal tissue subpopulations obtained from the [AlphaV+] subset. a=BCSP, b=BLSP, c=6C3, d=HEC, e=mSSC, f=pre-BCSP, g=PCP, h=Thy. Representative of 50 replicates.

(F) P3 Femur stained with Movat’s pentachrome (top). Sections stained with pentachrome of tissue grafts following cell transplant beneath the renal capsule (bottom). Populations e (mSSC), f (pre-BCSP) and a (BCSP) can reconstruct entire bone, consisting of bone, cartilage and a functional marrow cavity. Populations b (BLSP), c (6C3), d (HEC), and h (Thy) formed bone only. Population g (PCP) formed cartilage with a minimal of bone. Scale bar: 200µM. Representative of 3–20 experiments.

(G) Graph depicting the percentage tissue composition [bone (yellow), marrow (red), and cartilage (blue)] of each of the explanted grafts a to h. Representative of 3–20 experiments.

(H) Scheme of experiment: 20,000 cells of each subpopulation of [AlphaV+] were isolated from the long bones of GFP-labeled P3 mice using FACS. Purified GFP+ cells were then transplanted beneath the kidney capsules of recipient mice. One-month later, the grafts were explanted.

See also Figures S1, S3, S4, S6.

Purified cartilage, bone and stromal progenitors cells are heterogeneous and lineage restricted

As we had observed a high frequency of clonal regions in the growth plate during our ‘Rainbow’ clonal analysis, we isolated cells from the femoral growth plates by enzymatic and mechanical dissociation and analyzed them by FACS for differential expression of CD45, Ter119, Tie2, and AlphaV integrin. These surface markers correspond to those present on hematopoietic (CD45, Ter119), vascular and hematopoietic (Tie2), and osteoblastic (AlphaV integrin) cells. We found that the growth plate had a high frequency of cells that were CD45− Ter119− Tie2− AlphaV+ , hereafter referred to as [AlphaV+]. Based on subsequent microarray analysis of [AlphaV+] showing differential expression of CD105, Thy, 6C3, and CD200, we fractionated this population into eight sub-populations (Figure 1B, E, (Seita et al., 2012).

To evaluate the intrinsic ability of the eight sub-populations to give rise to skeletal tissue, we isolated cells of each subpopulation from the long bones, ribs and sternum of GFP+ mice (Figure 1E) and transplanted them beneath the renal capsule of immunodeficient mice (Figure 1H). Four weeks after transplantation, we explanted the GFP-labeled kidney grafts and processed the tissues for histological analysis to determine developmental outcome (Figure 1F). The eight subpopulations exhibited different developmental fates (Figure 1F–G): three followed a pattern of endochondral ossification (grafts consisting of bone, cartilage and marrow) (Figure 1F–G: populations a, e, f); four gave rise to primarily bone with minimal cartilage and no marrow (Figure 1F–G: populations b, c, d, h); and one gave rise to predominantly cartilage with minimal bone and no marrow (Figure 1F–G: population g). Unlike the eight subpopulations of [AlphaV+], the CD45/Ter119+ and Tie2+ subsets did not form bone, cartilage or stroma (Supplementary Figure 4), further emphasizing the existence of distinct progenitors of bone, cartilage and stromal tissue. These results indicate that the skeletogenic progenitors are diverse, with distinct cell surface marker profiles and skeletal tissue fates, similar to the diverse hematopoietic progenitor cells that generate various differentiated blood cells.

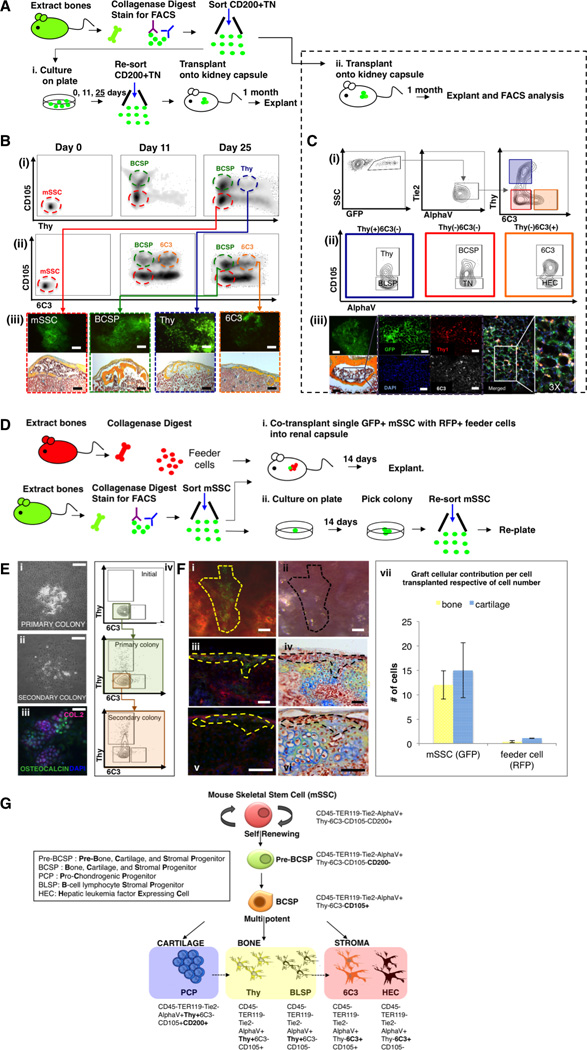

Identification of a post-natal skeletal stem cell

We hypothesized that skeletogenesis may proceed through a developmental hierarchy of lineage-restricted progenitors as occurs in hematopoiesis. We observed that the [CD45− Ter119− Tie2− AlphaV+ Thy− 6C3− CD105− CD200+ ] subpopulation generates all of the other (seven) subpopulations through a sequence of stages both in vitro and in vivo, beginning with generation of two multipotent progenitor cell types: firstly, the [CD45− Ter119− Tie2− AlphaV+ Thy− 6C3− CD105− CD200− ] cell population, hereafter referred to as the pre-BCSP (pre-bone cartilage and stromal progenitor); and the [CD45− Ter119− Tie2− AlphaV+ Thy− 6C3− CD105+ ] cell population which we previously described as the BCSP (bone, cartilage, and stromal progenitor) (Chan et al., 2013). The [CD45− Ter119− Tie2− AlphaV+ Thy− 6C3− CD105− CD200+ ] subpopulation generates in vitro and in vivo all of the other (seven) subpopulations in a linear fashion. In vitro, freshly sorted cells were cultured for 25 days, at which point they were re-fractionated by FACS (Figure 2A (i), Figure 2B (i), (ii)), and subsequently transplanted beneath the renal capsule (Figure 2A (i), Figure 2B (iii)). In vivo, the purified cells were transplanted beneath the renal capsule and explanted one month later for FACS analysis (Figure 2A (ii), Figure 2C (i), (ii)) or immunohistochemistry (Figure 2C (iii)). These data demonstrate that the [CD45− Ter119− Tie2− AlphaV+ Thy− 6C3− CD105− CD200+ ] subpopulation generates all of the other (seven) subpopulations in a linear fashion both in vitro and in vivo.

Fig 2. Identification of the mSSC (mouse Skeletal Stem Cell).

(A) Scheme of experiment: CD200+TN [CD45− Ter119− Tie2− AlphaV+ Thy− 6C3− CD105− CD200+ ] cells were isolated from femora of GFP+ mice at P3. (i) Purified mSSCs were seeded and harvested on days 0, 11, 25 for FACS analysis. On day 25 following re-fractionation of the cells by FACS, 20,000 cells of each subset (mSSC, BCSP, Thy, 6C3) were transplanted beneath the kidney capsules of recipient mice. The grafts were explanted 1 month later. (ii) Purified GFP-labeled mSSCs were also directly transplanted beneath the kidney capsules of recipient mice. 1 month post transplantation, the grafts were explanted.

(B) FACS analysis of cultured mSSC on days 0, 11 and 25 in culture (i, ii). Transplanted mSSC (red box) and BCSP (green box) formed bone, cartilage and a marrow cavity. Thy (blue box) and 6C3 (orange box) formed bone only, without a marrow cavity (iii). Scale bar: 500 µm (iii, upper panel), 200 µm (iii, lower panel). Representative of 3 replicates/subpopulation.

(C) (i, ii) FACS analysis of explanted kidney capsule grafts, in which highly purified populations of GFP-labeled[CD45− Ter119− Tie2− AlphaV+ Thy− 6C3− CD105− CD200+ ](mSSC) cells were transplanted beneath the kidney capsule: graft consisted of 7 downstream subpopulations (blue, red and orange boxes). Brightfield micrograph of pentachrome-stained explant (iii, far lower left) demonstrates that mSSCs are capable of generating bone, cartilage and marrow. Immunostained explant (purple box, zoomed) shows that mSSCs are capable of generating cells that express Thy and 6C3 (iii, middle; Thy = red, 6C3 = white). Merged image (iii, extreme right). Fluorescent image of GFP+ graft (iii far upper left). Scale bar: 500 µm (iii, upper panel), 100 µm (iii, lower panel), 50 µm (iii). Representative of 3 replicates per transplanted subpopulation.

(D) Scheme of experiment: Unsorted cells from the long bones of RFP+ P3 mice served as feeder cells. Cells from the long bones of P3 GFP+ mice were isolated following mechanical and enzymatic dissociation and mSSCs were obtained following FACS. (i) A single GFP-labeled mSSC was co-transplanted with 5,000 RFP(+) feeder cells beneath the renal capsule of immunodeficient mice. (ii) A single purified GFP-labeled mSSC was plated per well of a 96-well culture dish. Following 14 days, formed colonies were counted, harvested, re-sorted using FACS and a single purified GFP-labeled mSSC was again plated per well of a 96-well culture dish and the assay repeated.

(E) In vitro, colony formation assays were performed by plating a single mSSC in each well of a 96-well culture dish. (i) Representative micrograph of a primary colony depicted at 14 days post plating. (ii) Passaging of primary colonies resulted in the formation of secondary colonies with similar morphology to primary colonies. (iii) Primary colonies stained positive for anti-collagen 2 (purple), anti-osteocalcin (green), and DAPI (blue) following immunofluorescent staining. (iv) Vertical panel on right depicts FACS analysis of initial mSSC cells isolated (top), and subsequent primary colony (middle), and secondary colony cell (bottom). Scale bar: 500 µm (i, ii), 100 µm (iii). Representative of 10 assays.

(F) Microscopy of explanted grafts (as per Figure 2D (i)). The extent of the in vivo colony formation from GFP-labeled mSSCs is outlined by a yellow broken line (i, iii, v) or black broken line (ii, iv, vi). Clonally expanded, GFP-labeled mSSCs are seen as green cells (fluorescent image, i, iii, v). Corresponding brightfield micrographs (ii, iv, vi). Fluorescent imaging of transverse sections of grafts (iii, v). Corresponding brightfield micrographs of pentachrome-stained sections demonstrates clonally expanded cells are fated into bone (yellow) and cartilage (blue) (iv, vi). Graph (vii) is representative of the contribution by GFP or RFP cells (per cell transplanted) to bone or cartilage formation (mean SEM). Scale bar: 200 µm (i-vi). Representative of 5 transplants of each assay.

(G) Schematic representation of the skeletal stem cell lineage tree. The mSSC occupies the apex of this hierarchal tree and is multipotent, capable of self-renewal, and differentiation into more lineage restricted progenitor cells (pre-BCSP and BCSP). The mSSC, pre-BCSP and BCSP are capable of giving rise to bone, cartilage and hematopoietic supportive stroma. The immunophenotype of each cell is shown.

Single sorted cells from the [CD45− Ter119− AlphaV+ Thy− 6C3− CD105− CD200+ ] subpopulation also generated all of the other subpopulations in a linear fashion both in vitro and in vivo (Figure 2D–E). In vitro: Individual [CD45− Ter119− Tie2− AlphaV+ Thy− 6C3− CD105− CD200+ ] cells were plated and cultured for 14 days (Figure 2E (i)). FACS analysis of the resultant primary colonies showed that they contained clones of the original cell and all other (seven) subpopulations of [AlphaV+] (Figure 2E (iv): middle panel FACS plot). These colonies contained both cartilage and bone tissue when examined by immunohistochemistry (Figure 2E (iii)). Furthermore, when a single freshly-sorted [CD45− Ter119− Tie2− AlphaV+ Thy− 6C3− CD105− CD200+ ] cell isolated from the primary colony was again plated and cultured for 14 days, the resultant secondary colony contained clones of the original cell and all other subpopulations (Figure 2E (ii)) on FACS analysis (Figure 2E (iv): bottom panel FACS plot). These results demonstrate that the in vitro self-renewal of a single [CD45− Ter119− Tie2− AlphaV+ Thy− 6C3− CD105− CD200+ ] cell maintained the skeletogenic properties of freshly-isolated [CD45− Ter119− Tie2− AlphaV+ Thy− 6C3− CD105− CD200+ ] cells. In vivo: When transplanted individually, [CD45− Ter119− Tie2− AlphaV+ Thy− 6C3− CD105− CD200+ ] cells did not engraft efficiently beneath the renal capsule, perhaps reflecting their need for a supportive niche. Thus, we co-transplanted a single GFP-labeled [CD45− Ter119− Tie2− AlphaV+ Thy− 6C3− CD105− CD200+ ] cell with five-thousand unsorted, RFP-labeled cells isolated from the long bones to simulate a niche (Figure 2D (i)). Two-weeks after transplantation, we explanted the grafts for immunohistochemical analysis. The GFP-labeled transplanted cells (Figure 2F (i)–(ii)) differentiated into both chondrocytes and osteocytes in vivo (Figure 2F (iv), (vi)–(vii)), consistent with in vitro properties (Figure 2E (iii)). These data indicate that the [CD45− Ter119− Tie2− AlphaV+ Thy− 6C3− CD105− CD200+ ] population possesses definitive stem cell-like characteristics of self-renewal and multipotency. We therefore conclude that the [CD45− Ter119− Tie2− AlphaV+ Thy− 6C3− CD105− CD200+ ] cell population represents a mouse Skeletal Stem Cell (mSSC) population in post-natal skeletal tissues (Figure 2G), and that the seven other subpopulations of [AlphaV+] are mSSC progeny.

Based on the analyses described above, we defined a lineage tree of skeletal stem/progenitor cells (Figure 2G). The mSSC initiates skeletogenesis by producing a hierarchy of increasingly fate-limited progenitors. The multipotent and self-renewing mSSC first gives rise to multipotent progenitors, pre-BCSPs and BCSPs. These cells then produce the following oligolineage progenitors: pro-chondrogenic progenitors (PCPs) [CD45− Ter119− Tie2− AlphaV+ Thy+ 6C3− CD105+ CD200+ ]; the Thy subpopulation, [CD45− Ter119− Tie2− AlphaV+ Thy+ 6C3− CD105+ ] hereafter referred to as Thy; B-cell lymphocyte stromal progenitors, BLSPs [CD45− Ter119− AlphaV+ Thy+ 6C3− CD105− ]; the 6C3 subpopulation, [CD45− Ter119− AlphaV+ Thy− 6C3+ CD105+ ] hereafter referred to as 6C3; and the hepatic leukemia factor expressing cell, HEC [CD45− Ter119− AlphaV+ Thy− 6C3+ CD105− ] (Figure 2G). mSSC-derived lineages include cell types that we have previously characterized, which possess distinct hematopoietic supportive capabilities (Chan et al., 2013) (Supplementary Figure 2A, B).

II. Identification of Factors that Regulate Skeletal Stem and Progenitor Cell Activity and Differentiation

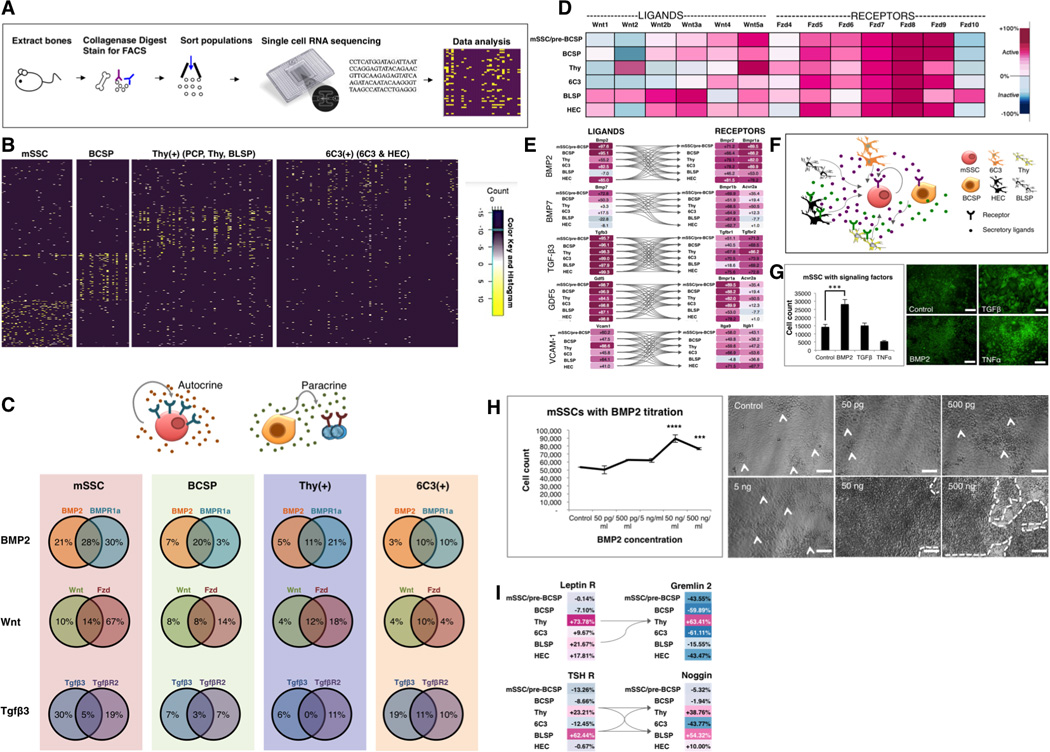

Downstream skeletal progenitors regulate mSSC activity

Once we had isolated the mSSC, we focused on identifying the cells that make up the mSSC niche, the microenvironment that supports and regulates stem cell activity. We first conducted microarray gene expression analyses of freshly-sorted mSSC/pre-BCSP and five downstream progenitor populations [(i) BCSP; (ii) Thy; (iii) 6C3; (iv) BLSP; and (v) HEC] to identify receptors to signaling pathways that may regulate activity of the mSSC and its progeny (Figure 3D–E).

Fig 3. The mSSC niche is composed of other skeletal-lineage cells.

(A) Scheme of experiment: Long bones of P3 mice were harvested as previously described. The cell suspension was sorted by FACS to obtain mSSC; BCSP; Thy(+), which encompasses the PCP, Thy and BLSP subsets; and 6C3(+), which encompasses 6C3 and HEC. Cell subpopulations were prepared for single cell RNA sequencing.

(B) Hierarchical clustering of single cell RNA sequencing data demonstrate four molecularly distinct patterns of single cell transcriptional expression between mSSC, BCSP, Thy(+) and 6C3(+).

(C) Percentage transcriptional expression of morphogen (left circle in each Venn diagram), receptor (right circle in each Venn diagram) or both (overlapping central portion of the Venn diagram) on single cell RNA sequencing. Note the percentage denotes the percentage of cells within each subset (mSSC, BCSP, Thy(+) and 6C3(+)), which express the relevant gene sequence. (Bottom) The patterns show the potential for paracrine (right) and autocrine (left) signaling.

(D) Gene expression levels of Wnt-associated genes in skeletal populations as determined using the Gene Expression Commons analysis platform. The range of transcriptional expression is illustrated by a color change as depicted on the extreme right of the figure (i.e. dark purple correlates to high expression, whereas dark blue correlates to low expression). Heat map shows high expression of both Wnt ligands (Wnt3a, Wnt4, Wnt5a) and receptors (Fzd5-9), demonstrating that Wnt signaling may be actively involved in skeletal progenitor function. Fzd = frizzled receptor. These data were compiled in triplicate, with 10,000 cells of each subset analyzed in each sample.

(E) Ligand-receptor interaction maps demonstrating that the skeletal stem/progenitor cells can act as their own niche and signal through each other to promote skeletogenesis. Gene expression analysis of microarray data extracted from skeletal subsets illustrating ligands in the left column and cognate receptors in the right column. The connecting arrows indicate possible ligand-receptor interaction pathways. Note: GDF= growth and differentiation factor, VCAM-1= vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Data were compiled from triplicate samples, with 10,000 cells of each subset analyzed in each sample.

(F) Diagram illustrating potential signaling pathways influencing activity of skeletal stem / progenitor cells. Paracrine and/or autocrine signaling may occur in the skeletal stem cell niche and regulate cell activity and maintenance.

(G) Fluorescent micrographs illustrate colony morphology of mSSCs post culture with morphogen (BMP2 / TGFβ /TNFα) supplementation/control (right). Graph shows the number of mSSC present following culture for 14 days under the different conditions (left). rhBMP-2 supplementation was associated with significant amplification of the mSSC populations in vitro (bottom left) in comparison to control, non-supplemented media (top left) (mean SEM, p<0.01, t-test, n=3). Supplementation with TGFβ or TNFα resulted in altered colony morphology (upper and lower right). These results show that niche signaling can influence mSSC proliferation. Scale bar: 200µm.

(H) Graph illustrates the effect of rhBMP2 titration on mSSC proliferation in culture (left). The effect of BMP-2 was significantly greater than control at each of the following concentrations: 50ng/mL (mean SEM, p<0.001, ANOVA), 500ng/mL (mean SEM, p<0.01, ANOVA). Phase images illustrate the colonies of cells derived from the mSSC (indicated by arrowhead in control, 50pg/mL, 500pg/mL, 5ng/mL and by a broken line in 50ng/mL and 500ng/mL) (right). Scale bar: 500µM, n=3.

(I) Ligand-receptor interaction maps show gene expression levels of BMP antagonists gremlin-2 and Noggin (right top and bottom respectively). There is increased expression of the receptors for the systemic hormones leptin and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) on the same subpopulations of downstream progenitors, Thy and BLSP (left top and bottom), which express BMP antagonists. Viewing the left and right panels in unison, the ligand-cognate receptor interaction graph shows that signaling through systemic hormones leptin and TSH receptors may produce inhibitory signals for mSSC expansion by BMP2 antagonism (via gremlin 2, noggin) and subsequent osteogenesis in skeletal stromal populations. Arrows illustrate the potential receptor-ligand interactions. Data were compiled from triplicate samples, with 10,000 cells of each subset analyzed in each sample.

See also Figures S2, S5.

To interpret the gene expression profiles of these cells, we used the Gene Expression Commons (Seita et al., 2012), a platform that normalizes microarray data against a large collection of publicly available microarray data from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus. From this analysis, it is apparent that mSSC and its progeny differentially express receptors involved in transforming growth factor, TGF (specifically bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)) and Wnt signaling pathways, and cognate morphogens of these pathways, including BMP2, TGF-β3 and Wnt3a (Figure 3D–E). These results suggest that paracrine and/or autocrine signaling among mSSCs and their progeny may positively regulate their own expansion (Figure 3F). Furthermore, single cell RNA sequencing revealed co-expression of BMP2 and its receptor (BMPR1a) in 28% of mSSC (Figure 3A–C, Supplementary Figure 5), supporting potential for autocrine and/or paracrine signaling in the mSSCs.

In support of transcriptional data, the addition of exogenous recombinant BMP2 to culture media rapidly induced expansion of isolated mSSC, while supplementation of media with either exogenous recombinant TGFβ or TNFα did not (Figure 3G, 3H). In addition, proliferation of mSSC in vitro was markedly inhibited by addition of recombinant gremlin 2 (an antagonist of BMP2 signaling) protein to culture media, in contrast to control. Progeny of the mSSC express antagonists of the BMP2 signaling pathway, such as Gremlin 2 and Noggin (Figure 3I), suggesting the presence of a potential negative feedback mechanism to control mSSC proliferation by more differentiated progeny. Specifically, Thy expresses Gremlin 2, and both Thy and BLSP express Noggin. This is consistent with Thy and BLSP subpopulations acting in a negative feedback loop to inhibit BMP-2 induced proliferation of the mSSC, further supporting a regulatory role for paracrine signaling among mSSCs and their progeny.

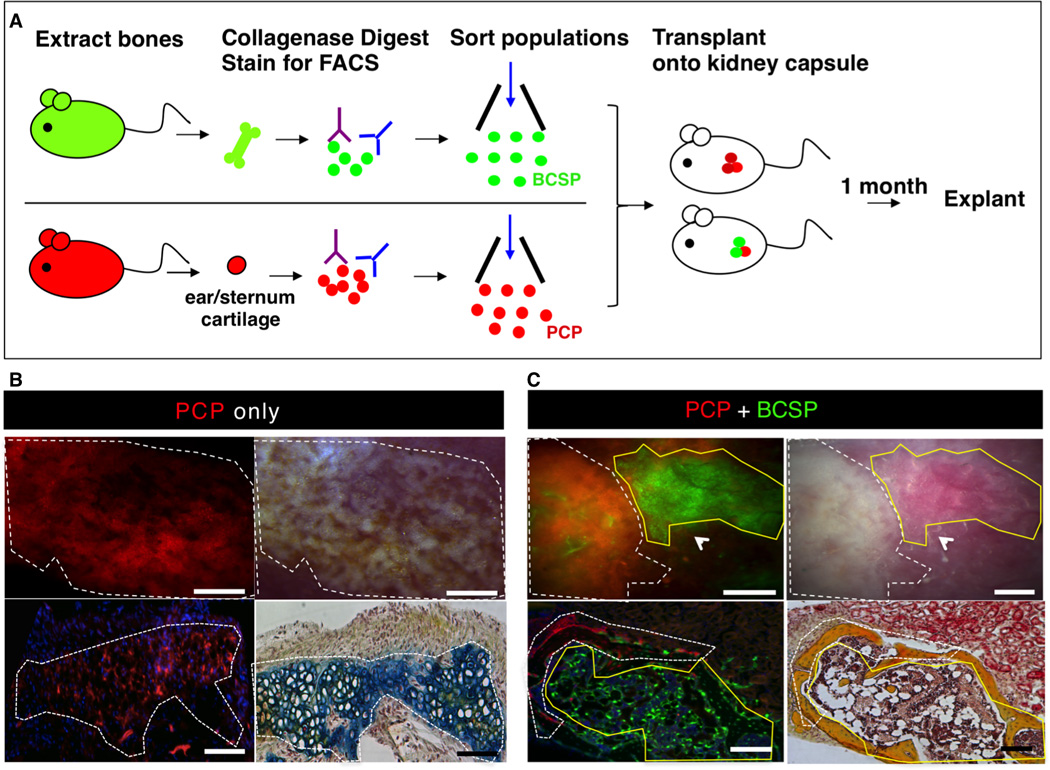

Shifting fates: cartilage to bone

Our next step was to comprehend signaling pathways that could play a role in directing the differentiation of skeletal stem/progenitor cells. Specifically, we wished to direct osteogenesis to chondrogenesis, as this is directly related to a large unmet clinical need for cartilage (Bhumiratana et al., 2014; Jo et al., 2014; Makris et al., 2014; Mollon et al., 2013). We asked whether mSSC-derived stroma could influence fate commitment of skeletal progenitor cells (Figure 2G). We observed that the skeletal subsets with the following immunophenotype [CD45-Ter119-AlphaV+Thy+6C3-CD105+CD200+](Figure 1F: population g) isolated from RFP+ mice are directed primarily towards cartilage formation when transplanted in isolation beneath the renal capsule of non-fluorescent mice; thus, we designated this cell the prochondrogenic progenitor (PCP) (Figure 4A, B). However, when RFP-labeled PCPs (Figure 2G) are co-transplanted with GFP-labeled BCSPs, they differentiate into bone but not cartilage (Figure 4C).

Fig 4. Shifting fates: cartilage to bone.

(A) Scheme of experiment: BCSPs were isolated from femora of GFP+ mice at P3 and PCPs (pro-chondrogenic progenitor) were isolated from ears/sternum of RFP+ adult mice following mechanical and enzymatic digestion, and subsequent FACS fractionation. Purified GFP+ BCSP and RFP+ PCP were co-transplanted beneath the kidney capsules of immunodeficient recipient mice. RFP+ PCP transplant served as a control. 1 month after transplantation, all grafts were removed for analysis.

(B) Microscopy of explanted grafts 1 month following transplantation of 20,000 RFP+ PCP cells (see Figure 4A). The white dotted line outlines the extent of the graft formed. Fluorescence micrograph of explanted graft demonstrating the presence of an RFP+ graft (upper left). Corresponding brightfield micrograph is shown in upper right panel. Transverse section stained with Movat’s Pentachrome demonstrates that RFP-labeled PCP cells form cartilage (blue stain) (lower right). Scale bar: 500µm (upper panel), 200µm (lower panel). Representative of 4 replicates.

(C) Microscopy of explanted grafts following co-transplantation of 20,000 RFP-labeled PCP cells with 20,000 GFP-labeled BCSPs (as detailed in Figure 4A). The grafts, which formed, are outlined by a white dotted line (indicating RFP+ portion) and a yellow solid line (indicating GFP+ portion) (upper left). A corresponding brightfield micrograph is shown in the upper right panel. A transverse section stained with Movat’s pentachrome shows that both RFP-labeled PCPs and GFP-labeled BCSPs form bone (yellow stain) (lower right). Scale bar: 500µm (upper panel), 200µm (lower panel). Representative of 5 replicates.

Shifting fates: bone to cartilage

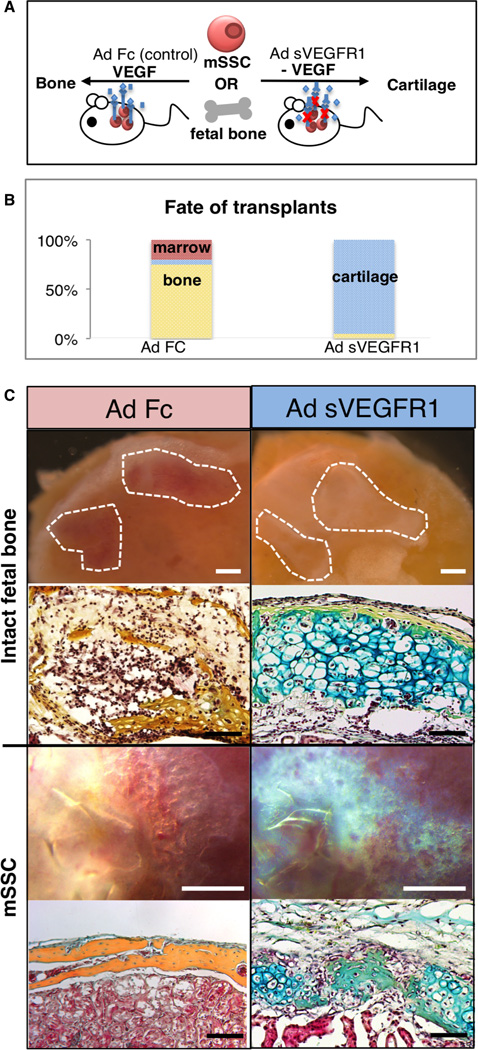

Having observed that signaling from co-transplanted BCSP could divert cartilage fated-cells towards bone formation, we next sought to identify factors that could, conversely, selectively promote mSSCs to cartilage rather than bone fates. Emerging evidence indicates that increased VEGF expression can spur resting chondrocytes to re-enter a hypertrophic state and resume endochondral ossification (Saito et al., 2010; Street et al., 2002). Thus, we aimed to determine whether inhibition of VEGF signaling could promote chondrogenic differentiation of mSSCs by blocking VEGF-dependent ossification (Figure 5A). We administered adenoviral vectors encoding a soluble ligand-binding ectodomain (ECD) of the VEGFR1 receptor (Ad sVEGFR1) intravenously, leading to potent systemic VEGF antagonism (Wei et al., 2013). Adenovirus encoding a control immunoglobulin IgG2α Fc domain served as control treatment. One day later, we transplanted either intact E14.5 pre-osteogenic fetal femora or freshly-sorted mSSC under the renal capsule of these mice, and then explanted the tissue 3 weeks later (Figure 5A). The grafts from the Ad sVEGFR1-treated mice contained predominantly cartilaginous tissue (Figure 5B(right)). In contrast, the grafts from the control Ad Fc animals evidenced endochondral ossification and formation of a marrow cavity surrounded by cortical bone (Figure 5B(left)). These results suggest that VEGF blockade may promote chondrogenesis at the expense of osteogenesis (Figure 5C).

Fig 5. Shifting fates: bone to cartilage.

(A) Scheme of experiment: mSSCs were isolated from P3 mice as described previously. Either intact pre-osteogenic femora isolated from E14.5 mice or 20,000 mSSCs were then transplanted beneath the kidney capsule of recipient mice with / without systemic inhibition of VEGF signaling. For inhibition of VEGF signaling, adenoviral vectors encoding soluble VEGFR1 ectodomain (Ad sVEGFR1) were delivered intravenously to the recipient mice 24 hours prior to cell transplantation, leading to systemic release of this potent antagonist of VEGF signaling. Ad Fc encoding an immunoglobulin Fc fragment was served as a negative control. Grafts were explanted 3 weeks later.

(B) Explanted grafts are shown in the first and third row from the top of the panel (control, Ad Fc in left panel and Ad sVEGFR1 in the right panel). Representative sections stained with Movat’s pentachrome are shown in the second and fourth rows from the top of the panel. (top two rows: intact fetal bone, bottom two rows: mSSC) VEGF signaling inhibition resulted in the formation of cartilage (blue stain) (right), with the Ad Fc group forming bone (yellow stain) (left). Scale bar: 500µm (Intact fetal bone, top), 100µm (Intact fetal bone, bottom), 500 µm (mSSC, top), 200 µm (mSSC, bottom). Representative of 5 replicates per assay.

(C) Graphic representation of the fate of the mSSC/fetal bone transplants in the presence of Ad sVEGFR1 or Ad Fc control. Cartilaginous fate is promoted in the presence of systemic VEGF antagonism. (n=5, ANOVA, p<0.001).

BMP pathway manipulation can induce de novo formation of the mSSC in extra-skeletal locations

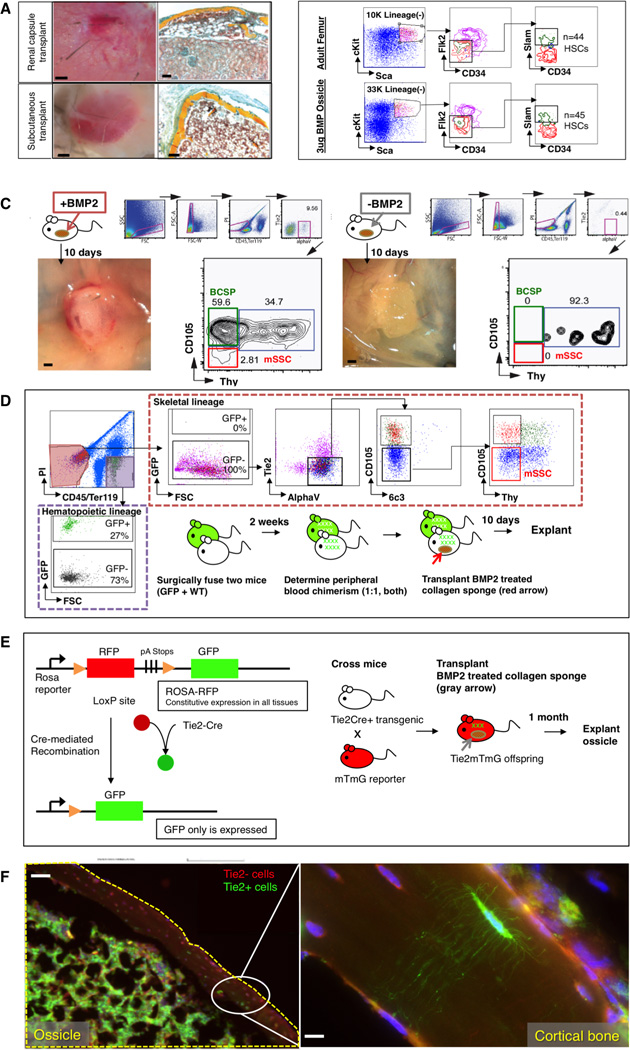

We next investigated whether other tissue types contain cells that are osteo-inducible or harbor dormant mSSCs that can be activated to undergo osteogenesis. As we observed that BMP2 can expand mSSC in vitro (Figure 3G, H), we tested BMP2 as an agent that may induce such osteogenesis. We placed collagen sponges containing recombinant BMP2 into subcutaneous extraskeletal sites. Harvest of the collagen sponges 4 weeks after placement revealed abundant osseous osteoids replete with marrow (Figure 6A–C). Furthermore, FACS analysis of cells within the marrow of the induced osteoids revealed that HSC engraftment also occurs in the osteoids (Figure 6B). By FACS analysis we determined that mSSC are normally not detectable or are exceedingly rare in subcutaneous adipose tissue (Figure 6C: right panel). In contrast, mSSC are plentiful in BMP2-induced osteoids 10 days after implantation, while ossification is still proceeding (Figure 6C: left panel).

Fig 6. Manipulation of the BMP pathway can induce de novo formation of the mSSC in extraskeletal regions.

(A) Collagen sponges containing 3ug of lyophilized rhBMP2 were placed into extraskeletal sites in C57BL6 wild-type mice. 1 month later, the graft was explanted for analysis. Brightfield images of explants, with renal capsule transplant shown above and subcutaneous transplant shown below (left). Transverse sections stained with Movat’s Pentachrome demonstrate that induced osseous osteoids formed a marrow cavity (red stain) (right). Scale bar: 500µm (left), 200 µm (right). Representative of 5 replicates.

(B) FACS analysis of cells within the induced osteoid marrow reveals that circulating SlamF1 positive HSC engraftment occurs in the osteoids (bottom row) similar to that which occurs naturally in “normal” adult femurs (top row). Representative of 3 replicates.

(C) (Left) Following explantation of rhBMP2-laced collagen sponges at day 10 post extraskeletal placement, FACS analysis of constituent cell populations present within the graft revealed that mSSC (red box on FACS plot) and BCSP (green box on FACS plot) are readily detectable in the rhBMP2 treated explants. (Right) In contrast, FACS-analysis of adipose tissue in the absence of BMP2 does not detect either mSSC (red box on FACS plot) or BCSP (green box on FACS plot). Scale bar: 500 µm. Representative of 3 replicates.

(D) A parabiosis model of GFP+ and non-GFP mouse shows that circulating skeletal progenitor cells did not contribute to BMP2-induced ectopic bones. A GFP+ mouse was parabiosed to a non-GFPmouse. Two weeks later, a collagen sponge containing 3ug of lyophilized rhBMP2 was transplanted into the inguinal fat pad of the non-GFP mouse. Ten days later, the tissue was explanted and isolated the constituent cell populations of the ectopic bone tissue as described previously. The contribution of the GFP-labeled cells to ectopic bone formation in the non-GFP mouse was analyzed by FACS (broken red line; GFP+ = circulating cells, and non-fluorescent = local cells). GFP-labeled cells contributing to the graft were solely CD45(+) hematopoietic cells (extreme left panel, broken purple line), and not consistent of the skeletal progenitor population (horizontal upper panel, mSSC shown in red box on FACS plot). Representative of 3 replicates.

(E) (Left) Diagram of reporter gene mouse model shows that Tie2 expression leads to GFP expression. Tie2+ cells turn green but Tie2− cells remain red. (right) Scheme of experiment: In order to determine the cell types, which could undergo BMP-2 mediated reprogramming to mSSC in extraskeletal sites, we implemented a Tie2Cre x MTMG reporter mouse and placed a collagen sponge containing rhBMP2 into the subcutaneous inguinal fat pad. The ossicle was explanted 1 month later for histological analysis.

(F) Fluorescent micrographs: BMP-2 derived ossicles (yellow broken line) clearly incorporate both GFP+ Tie2+ derived osteocytes with visible canaliculi and Tie2− negative RFP-labeled osteocytes. Area denoted by white oval is shown at higher magnification in the box on the extreme right, showing the presence of (GFP+) Tie2+ canaliculi in the presence of (RFP+) Tie2−cells. Scale bar: 500µM (left), 50um (right). Representative of 3 replicates.

To determine whether BMP2 induced skeletal transformation of in situ cells or migration of circulating skeletal progenitors recruited from bone tissue, we used a parabiont model (Figure 6D). We surgically fused actin-GFP transgenic mice to non-GFP congenic mice such that they established a shared circulatory system (Conboy et al., 2013). Two weeks after parabiosis, after confirmation of chimerism, we implanted collagen sponges containing recombinant BMP2 into the inguinal fat pad of the non-GFP parabiont. Ten days after implantation, we explanted the sponge and surrounding tissue and performed mechanical and chemical dissociation to isolate the constituent cells. We assayed the contribution of the GFP-labeled cells to ectopic bone formation in the non-GFP mouse by FACs analysis, to determine whether circulating cells contributed to ectopic bone development. The tissue of the explants contained abundant GFP-labeled cells at harvest, but GFP-labeled cells in the graft were solely CD45(+) hematopoietic cells (Figure 6D: left panel, top and bottom), and not skeletal progenitors (Figure 6D: FACS plots, mSSC cell population shown on far right). The skeletal progenitor population present in the explanted tissue was entirely GFP-negative, suggesting that circulating cells did not contribute to BMP2-induced ectopic bone. These data indicate that BMP2-induced osteogenesis involves local cell response that is sufficient to induce mSSC formation in the subcutaneous fat pads, leading to formation of ectopic bone that can support hematopoiesis.

We next wished to determine which cell types could undergo BMP2-mediated reprogramming to mSSC in these extraskeletal sites. We, therefore, conducted FACS analysis of suspended cells isolated from the kidney and the subcutaneous adipose tissue and looked for markers that could distinguish cell types common to both of these extraskeletal organs. We found that both kidney and adipose tissue contain high numbers of Tie2 (Arai et al., 2004; De Palma et al., 2005; Heldin and Westermark, 1999). Using a specific Tie2Cre x MTMG reporter mouse, which genetically labels cells that expressed Tie2 with GFP and other cells with RFP, we again inserted collagen sponges containing recombinant BMP2 into the inguinal fat pad and harvested the implanted tissue one month later (Figure 6E). FACS analysis revealed that BMP2-derived ossicles clearly incorporated GFP-positive Tie2-derived osteocytes with visible canaliculi (Figure 6F: high magnification inset) and Tie2-negative RFP-labeled osteocytes (Figure 6F), suggesting both that Tie2-positive and Tie2-negative lineages underwent BMP2-induced skeletal reprogramming. These data suggest that a variety of cell types could potentially be induced by BMP2 to initiate formation of mSSC.

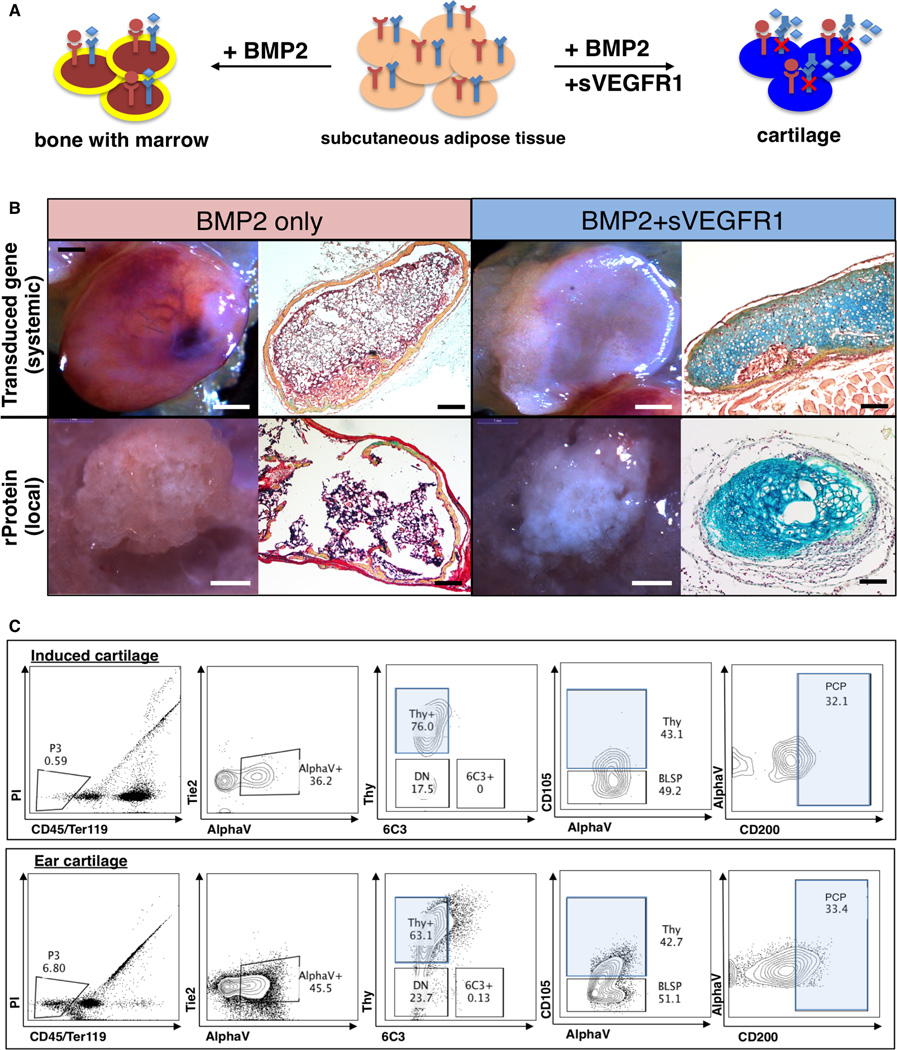

Co-delivery of BMP2 and VEGF inhibitor is sufficient to induce de novo formation of cartilage in adipose tissue

While bone itself possesses regenerative ability, the capacity for regeneration in other skeletal tissue (e.g. cartilage) is very low. As BMP2 induction could stimulate mSSC expansion and formation (Figure 3G–H, Figure 6C), we speculated that the mSSC-inducing capacity of BMP2 could be coupled with VEGF blockade to direct de novo cartilage formation. To test this possibility, we implanted BMP2-treated collagen sponges into the adipose tissue of mice that had been treated 24 hours earlier with either intravenous Ad sVEGFR1 as in Figure 5, or included soluble VEGFR1 ECD (50 µg) directly in the collagen sponge (Figure 7A). One month later the tissues were explanted. BMP2 alone generated bone tissue with a marrow cavity (Figure 7B: left panel). However, BMP2 with either systemic or local VEGF inhibition resulted in predominant cartilage formation (Figure 7B: right panel). The induced cartilage contained a similar frequency of PCPs to that seen in natural cartilage (Figure 7C). Since native adipose tissue normally does not undergo chondrogenesis, the induced cartilage likely derives from BMP2-induced mSSCs that were shifted towards cartilage fate by the action of VEGF blockade.

Fig 7. Co-delivery of BMP2 and VEGF inhibitor is sufficient to induce de novo formation of cartilage in adipose tissue.

(A) Scheme of experiment: co-delivery of BMP2 and soluble VEGFR1 in adipose tissue. BMP2 and inhibition of VEGF signaling leads to cartilage formation. BMP2 alone leads to bone formation.

(B) Fate of subcutaneous collagen sponge implants containing BMP2 without (2 panels on left) or with VEGF blockade (2 panels right). 1 month after placement of collagen sponges, the grafts were explanted for analysis. Brightfield images of grafts (left) are shown alongside representative sections stained with Movat’s pentachrome (right). The co-delivery of BMP2 and sVEGFR1 resulted in the formation of blue staining cartilage (extreme right panels, top and bottom). The result following systemic VEGF blockade is shown in the top series on the right, while the result of local VEGF blockade is shown in the bottom series on the right. Scale bar: (panels moving from right to left): 1mm, 200µm, 1mm, 200 µm. Representative of 4 replicates.

(C) FACS plot analysis of the constituent cells of the induced cartilage (top horizontal panel) (experimental scheme as shown in Figure 7A) versus those of freshly isolated cells from ear cartilage of age-matched mice (bottom horizontal panel) demonstrates that PCPs (pro-chondrogenic progenitor) are found in similar frequency in the induced and natural cartilage tissue. Representative of the assay performed in triplicate.

Translational Implications of Skeletal Stem Cell Biology

We next investigated the role of mSSC in skeletal repair. Highlighting their potential regenerative capabilities, we find that the mSSC number is significantly higher in the callus of a fractured femur than in the uninjured femur; (Supplementary Figure 6A–B). Interestingly, mSSCs isolated from a fracture callus also demonstrate enhanced osteogenic capacity (in comparison to uninjured) in vitro (Supplementary Figure 6C: left panel) and in vivo (Supplementary Figure 6C: right panel). Since it is well known that irradiation results in osteopenia and reduced fracture healing (Mitchell and Logan, 1998), we asked if the skeletal response to irradiation is linked to depletion of mSSC activity. When mice were irradiated 12 hours prior to fracture induction, we noted a significant reduction in mSSC expansion at one week following fracture in comparison to non-irradiated femora 1-week post fracture (Supplementary Figure 6D), echoing previous observation (Galloway et al., 2009).

Discussion

Identifying postnatal skeletal stem/progenitor cells and defining the lineage tree

The mSSC lineage map we present consists of eight different cellular subpopulations with distinct skeletogenic properties and encompasses subpopulations that have characteristics of described skeletogenic cell types identified by lineage tracing (Bianco, 2014, Mendez-Ferrer et al., 2010; Park et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2014). For example, the Thy subtype selectively expresses high levels of CXCL12, leptin receptor, and nestin, which are characteristics of CXCL12-abundant reticular cells, leptin receptor–expressing cells (LepR+), and Nestin-expressing mesenchymal stem cells, respectively. We also find that both Nestin-cre and MX1-cre labeled populations overlap with the mSSC population (Supplementary Figure 3) (Chan et al., 2013).

Signals controlling mSSC and progenitor activity

Mechanistically, mSSC expansion and self-renewal must be tightly controlled, evidenced by the expression of numerous cognate receptors to signaling molecules belonging to most of the known signaling pathways including Hedgehog, BMP, FGF, Notch. Both BMP2 and 4 are expressed by mSSCs and most mSSC-derived subsets, where they likely mediate survival and expansion via both autocrine and paracrine loops. Conversely, downstream progeny of mSSCs, such as Thy and BLSP populations, express noggin and/or gremlin-2, which antagonize BMP signaling. This suggests that mSSCs and some of their progeny form a portion of their own niche, maintaining critical levels of pro-survival factors such as BMP2 but also controlling skeletal growth by antagonizing BMP signaling. In addition, mSSCs are dramatically amplified in fracture callus, implying that extrinsic signals generated in the regenerative environment could locally activate these cells (Supplementary Figure 6).

Directing skeletal progenitor fate determination from bone to cartilage

Antagonistic signaling between mSSC-derived skeletal subsets also appears to be a key mechanism in skeletal subset lineage commitment, particularly to either a bone or cartilage fate. When we antagonized VEGF signaling in early skeletal progenitors, bone fates were inhibited in favor of cartilage fates. These results echo previous reports, which suggest that VEGF acts as an essential chondrogenic regulator (Carlevaro et al., 2000; Gerber et al., 1999; Harper and Klagsbrun, 1999).

Directing skeletal progenitor fate determination from cartilage to bone

Paracrine signaling among skeletal subsets may also participate in determining bone versus cartilage formation, specifically in favoring bone. Altered signaling in a particular subpopulation can direct the skeletal fate of other subpopulations in the microenvironment. It is possible that pathological conditions involving calcification of cartilaginous tissues, such as osteoarthritis, could stem from defects in the mSSC niche, leading to aberrant signaling that promotes osteogenesis.

Hematopoietic and skeletal stem cell homeostasis may be closely related

At a transcriptional level, mSSC-generated progeny express numerous cytokines necessary for HSC maintenance and hematopoiesis, including Kit ligand and stromal derived factor (Supplementary Figure 2C). We also find evidence that stem and progenitor cells of the hematopoietic system may reciprocally regulate skeletal progenitors (Supplementary Figure 2A–B,D). We conducted gene expression analysis of multiple hematopoietic stem and progenitor subsets and found that hematopoietic progenitors express myriad factors associated with skeletogenesis, including BMP2, BMP7 and Wnt3a. As previously shown, the cognate receptors of these factors are highly expressed by mSSCs and their progeny (Figure 3D–E). Intriguingly, while mSSC-generated progeny, such as Thy and BLSP, selectively express receptors to circulating systemic hormones, such as leptin and thyroid-stimulating hormone, these receptors are not highly expressed in HSCs or hematopoietic subsets (Supplementary Figure 2D, data not shown, (Seita et al., 2012)), thus, suggesting that mSSC-derived stromal cells may link systemic endocrine regulation to both skeletal and hematopoietic systems.

Altering extra-skeletal niche signaling to induce osteogenesis and chondrogenesis

Modulating niche signaling can stimulate tissue growth by inducing proliferation of stem cells, as we have observed with skeletal stem cells and as described in the hematopoietic system (Calvi et al., 2003). Niche interactions may also play significant roles in maintaining lineage commitment, for instance, high levels of BMP2 signaling can dominate local adipose signaling and re-specify resident Tie2(+) and Tie2(−) subsets to undergo osteogenesis. Niche interactions can also determine the fate of the mSSC. By implanting BMP2-treated collagen sponges in concert with systemic or local application of soluble VEGF receptor, we demonstrate that cartilage can be induced to form entirely by manipulation of local signaling pathways in extra-skeletal tissue.

Conclusion

Inducing mSSC formation with soluble factors and subsequently regulating the mSSC niche to specify its differentiation towards bone, cartilage, or stromal cells could represent a paradigm shift in the therapeutic regeneration of skeletal tissues. This therapeutic modality could also extend to the co-dependent hematopoietic system even when resident levels of endogenous mSSCs have been depleted by disease or aging. The challenge now is to understand how intrinsic and extrinsic signals guide mSSC to regulate skeletal shape and patterning at the single cell level.

Experimental procedures

Detailed experimental procedures described in the Supplementary Information.

Mice

C57BL6, Rag-2/gamma(c)KO, C57BL/6-Tg(CAG-EGFP)1Osb/J, Mx1Cre and mTmG were bred in our laboratory. Rosa-Tomato Red RFP and Tie2Cre mice were obtained from Jackson. ‘Rainbow’ mice were bred with mice harboring a TMX-inducible ubiquitously expressed Cre under the promoter of the actin gene. Mice were bred at our animal facility according to NIH guidelines. Protocols were approved by the institutional review board.

Isolation and transplantation of adult and fetal skeletal progenitors

Skeletal tissues were dissected from P3 GFP-labeled mice and dissociated by mechanical and enzymatic dissociation. Total dissociated cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for fractionation by FACS. Sorted and unsorted skeletal progenitors were then injected under the renal capsule of immunodeficient mice.

Transcriptional Expression Profiling

Microarray analyses was performed on mSSC/pre-BCSP, BCSP, Thy(+), 6C3(+), HEC and BLSPs. RNA was isolated, twice amplified, streptavidin-labeled, fragmented, and hybridized to Affymetrix 430-2.0 arrays. Raw microarray data were submitted to Gene Expression Commons (http://gexc.stanford.edu). Heat maps representing fold change of gene expression were generated in Gene Expression Commons.

Histological analysis of endochondral ossification

Representative sections were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin, Movat’s modified pentachrome, or Alizarin Red stains depending on requirement.

Immunofluorescence

Briefly, specimens were treated with a blocking reagent, then probed with monoclonal antibody at 4°C overnight. Specimens were washed, probed with alexa-dye conjugated antibodies, washed and imaged with an inverted microscope.

Cell culture

Skeletal progenitors were cultured in MEMα medium with 10% FCS, 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin under low O2 (2% atmospheric oxygen, 7.5%CO2) conditions. For mSSC colony forming assays, single cells were sorted into each well of a 96-well plate and cultured for 2 weeks.

Parabiosis

Age and sex-matched congenic mice of GFP and non-GFP mice were sutured together along the dorsal-dorsal, and ventral-ventral folds of the skin flaps. Two weeks later, blood chimerism was assessed by FACS.

In vivo osteo-induction with BMP2

rhBMP2 was re-suspended in sterile filtered buffer and applied to a collagen sponge. Sponge was lyophilized and transplanted subcutaneously into anesthetized mice.

Inhibition of VEGF signaling

To study systemic inhibition of VEGF signaling, 109 pfu units of adenoviral vectors encoding the soluble murine VEGFR1 ectodomain (Ad sVEGFR1) was injected intravenously to the designated recipient mice 24 hours prior to transplantation, leading to hepatic infection and secretion of this potent antagonist of VEGF signaling into the circulation. For negative control, adenovirus encoding a murine IgG2α Fc immunoglobulin fragment was used (Ad Fc). These reagents are described elsewhere (Wei et al., 2013).

(ii) Local VEGF inhibition: 50µg of soluble VEGFR1 was placed into the subcutaneous fat of along with a collagen sponge containing lyophilized recombinant BMP2.

Single Cell RNA sequencing

This was performed as previously described (Treutlein et al., 2014).

Mouse Femoral Fracture +/− Hind limb Irradiation

An incision was made from the groin crease to the knee of the right femur. A medullary rod was placed via the intercondylar fossa. A bicortical transverse mid-diaphyseal fracture was created and the skin incision closed with nylon sutures and the mice received post-operative analgesia. The callus was harvested and constituent cells isolated by mechanical and enzymatic dissociation and subsequent FACS fractionation. C57BL6 hind-limbs received a single dose of 800 rads (8Gy) to bilateral hind limbs. Surgical placement of fracture was performed 12 hours post irradiation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Seth Karten for his critical help in editing the manuscript; Christopher Duldulao and Tejaswitha Naik for technical assistance; Shirley Kantoff, Libuse Jerabek and Terry Storm for laboratory management; Aaron McCarty and Felix Manuel for animal care; Patty Lovelace and Jennifer Ho in the Shared FACS Facility in the Lokey Stem Cell Institute; Steve Quake, Norma Neff, Sopheak Sim and Gary Mantalas for critical help while performing single cell RNA sequencing.

The authors would like to acknowledge ongoing support for this work: National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants U01HL099999, R01 CA86065 and R01 HL058770 (to I.L.W); R01 DE021683, R21 DE024230, R01 DE019434, RC2 DE020771, U01 HL099776, R21 DE019274 (to M.T.L.), 1R01CA158528, 1R01NS064517 and 2U01DK085527-06 (to C.J.K); Siebel Fellowship from Thomas and Stacey Siebel Foundation, Prostate Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award(to C.K.F.C.), CIRM TR1-01249, the Oak Foundation, the Hagey Laboratory for Pediatric Regenerative Medicine, the Gunn/Olivier Research Fund (to M.T.L); The Stanford Medical Scientist Training Program, NIH-T32GM007365 (to J.Y.C); Stanford University Transplant and Tissue Engineering Center of Excellence Fellowship (to A.McA and R.T.); the Plastic Surgery Foundation / Plastic Surgery Research Council Pilot Grant and the American Society of Maxillofacial Surgeons Research Grant (to R.T.); Burroughs Wellcome Career Award for Medical Scientists, K08 DK096048 01(to K.S.Yan); Stanford Developmental Cancer Research Award (to D.S.); the Stanford Medical Scientist Training Program, NIGMS training grant GM07365 (to G.G.W) and the Anonymous Donor Skeletal Stem Cell Research Fund (to E.S., C.K.F.C., M.T.L.).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributions

C.K.F.C, I.L.W, M.T.L conceived the overall project strategy; C.K.F.C, E.S, J.Y.C, D.L, A.McA, R.T., J.V.T, T.W., W.J.L, K.S.Y, M.T.C, O.M., M.T., R.U., G.G.W, A.S.L designed, performed and interpreted data, contributed to the writing and editing of manuscript and prepared figures. R.S., E.S. and D.S. performed single cell RNA sequencing/analysis; J.S. provided new algorithms for transcriptional analysis. C.K. and K.S. Yan designed and contributed reagents for vascular signaling manipulation. I.L.W and M.T.L edited manuscript and supervised laboratory.

References

- Arai F, Hirao A, Ohmura M, Sato H, Matsuoka S, Takubo K, Ito K, Koh GY, Suda T. Tie2/angiopoietin-1 signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 2004;118(2):149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhumiratana S, Eton RE, Oungoulian SR, Wan LQ, Ateshian GA, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Large, stratified, and mechanically functional human cartilage grown in vitro by mesenchymal condensation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:6940–6945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324050111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco P. Bone and the hematopoietic niche: a tale of two stem cells. Blood. 2011;117:5281–5288. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-315069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco P. "Mesenchymal" stem cells. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2014;30:677–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr DB. The importance of subchondral bone in the progression of osteoarthritis. The Journal of rheumatology Supplement. 2004;70:77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, Weber JM, Olson DP, Knight MC, Martin RP, Schipani E, Divieti P, Bringhurst FR, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the hematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425:841–846. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlevaro MF, Cermelli S, Cancedda R, Descalzi Cancedda F. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in cartilage neovascularization and chondrocyte differentiation: auto-paracrine role during endochondral bone formation. Journal of cell science. 2000;113((Pt 1)):59–69. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references are listed in SI

- Chan CK, Lindau P, Jiang W, Chen JY, Zhang LF, Chen CC, Seita J, Sahoo D, Kim JB, Lee A, et al. Clonal precursor of bone, cartilage, and hematopoietic niche stromal cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:12643–12648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310212110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conboy MJ, Conboy IM, Rando TA. Heterochronic parabiosis: historical perspective and methodological considerations for studies of aging and longevity. Aging cell. 2013;12:525–530. doi: 10.1111/acel.12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Palma M, Venneri MA, Galli R, Sergi Sergi L, Politi LS, Sampaolesi M, Naldini L. Tie2 identifies a hematopoietic lineage of proangiogenic monocytes required for tumor vessel formation and a mesenchymal population of pericyte progenitors. Cancer cell. 2005;8(3):211–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finerty JC. Parabiosis in physiological studies. Physiological reviews. 1952;32:277–302. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1952.32.3.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedenstein AJ, Chailakhyan RK, Gerasimov UV. Bone marrow osteogenic stem cells: in vitro cultivation and transplantation in diffusion chambers. Cell and tissue kinetics. 1987;20:263–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1987.tb01309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway JL, Delgado I, Ros MA, Tabin CJ. A reevaluation of X-irradiation-induced phocomelia and proximodistal limb patterning. Nature. 2009;460:400–404. doi: 10.1038/nature08117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber HP, Vu TH, Ryan AM, Kowalski J, Werb Z, Ferrara N. VEGF couples hypertrophic cartilage remodeling, ossification and angiogenesis during endochondral bone formation. Nature medicine. 1999;5:623–628. doi: 10.1038/9467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta V, Poss KD. Clonally dominant cardiomyocytes direct heart morphogenesis. Nature. 2012;484:479–484. doi: 10.1038/nature11045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper J, Klagsbrun M. Cartilage to bone--angiogenesis leads the way. Nature medicine. 1999;5:617–618. doi: 10.1038/9460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldin CH, Westermark B. Mechanism of action and in vivo role of platelet-derived growth factor. Physiological reviews. 1999;79(4):1283–1316. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo CH, Lee YG, Shin WH, Kim H, Chai JW, Jeong EC, Kim JE, Shim H, Shin JS, Shin IS, et al. Intra-articular injection of mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a proof-of-concept clinical trial. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2014;32:1254–1266. doi: 10.1002/stem.1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilic G, Kilic E, Akgul O, Ozgocmen S. Decreased femoral cartilage thickness in patients with systemic sclerosis. The American journal of the medical sciences. 2014;347:382–386. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31829a348b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris EA, Gomoll AH, Malizos KN, Hu JC, Athanasiou KA. Repair and tissue engineering techniques for articular cartilage. Nature reviews Rheumatology. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Ferrer S, Michurina TV, Ferraro F, Mazloom AR, Macarthur BD, Lira SA, Scadden DT, Ma'ayan A, Enikolopov GN, Frenette PS. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466:829–834. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell MJ, Logan PM. Radiation-induced changes in bone. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 1998;18:1125–1136. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.18.5.9747611. quiz 1242-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollon B, Kandel R, Chahal J, Theodoropoulos J. The clinical status of cartilage tissue regeneration in humans. Osteoarthritis and cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2013;21:1824–1833. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison JI, Loof S, He P, Simon A. Salamander limb regeneration involves the activation of a multipotent skeletal muscle satellite cell population. The Journal of cell biology. 2006;172:433–440. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D, Spencer JA, Koh BI, Kobayashi T, Fujisaki J, Clemens TL, Lin CP, Kronenberg HM, Scadden DT. Endogenous bone marrow MSCs are dynamic, fate-restricted participants in bone maintenance and regeneration. Cell stem cell. 2012;10:259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinkevich Y, Lindau P, Ueno H, Longaker MT, Weissman IL. Germ-layer and lineage-restricted stem/progenitors regenerate the mouse digit tip. Nature. 2011;476:409–413. doi: 10.1038/nature10346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinkevich Y, Montoro DT, Muhonen E, Walmsley GG, Lo D, Hasegawa M, Januszyk M, Connolly AJ, Weissman IL, Longaker MT. Clonal analysis reveals nerve-dependent and independent roles on mammalian hind limb tissue maintenance and regeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:9846–9851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410097111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T, Fukai A, Mabuchi A, Ikeda T, Yano F, Ohba S, Nishida N, Akune T, Yoshimura N, Nakagawa T, et al. Transcriptional regulation of endochondral ossification by HIF-2alpha during skeletal growth and osteoarthritis development. Nature medicine. 2010;16(6):678–686. doi: 10.1038/nm.2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepers AG, Snippert HJ, Stange DE, van den Born M, van Es JH, van de Wetering M, Clevers H. Lineage tracing reveals Lgr5+ stem cell activity in mouse intestinal adenomas. Science (New York, NY) 2012;337:730–735. doi: 10.1126/science.1224676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seita J, Sahoo D, Rossi DJ, Bhattacharya D, Serwold T, Inlay MA, Ehrlich LI, Fathman JW, Dill DL, Weissman IL. Gene Expression Commons: an open platform for absolute gene expression profiling. PloS one. 2012;7:e40321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street J, Bao M, deGuzman L, Bunting S, Peale FV, Jr, Ferrara N, Steinmetz H, Hoeffel J, Cleland JL, Daugherty A, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor stimulates bone repair by promoting angiogenesis and bone turnover. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(15):9656–9661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152324099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Hendrickson DG, Sauvageau M, Goff L, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Differential analysis of gene regulation at transcript resolution with RNA-seq. Nature biotechnology. 2013;31:46–53. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treutlein B, Brownfield DG, Wu AR, Neff NF, Mantalas GL, Espinoza FH, Desai TJ, Krasnow MA, Quake SR. Reconstructing lineage hierarchies of the distal lung epithelium using single-cell RNA-seq. Nature. 2014;509:371–375. doi: 10.1038/nature13173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno H, Weissman IL. Clonal analysis of mouse development reveals a polyclonal origin for yolk sac blood islands. Developmental cell. 2006;11:519–533. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei K, Piecewicz SM, McGinnis LM, Taniguchi CM, Wiegand SJ, Anderson K, Chan CW, Mulligan KX, Kuo D, Yuan J, et al. A liver Hif-2alpha-Irs2 pathway sensitizes hepatic insulin signaling and is modulated by Vegf inhibition. Nature medicine. 2013;19(10):1331–1337. doi: 10.1038/nm.3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Anczukow O, Krainer AR, Zhang MQ, Zhang C. OLego: fast and sensitive mapping of spliced mRNA-Seq reads using small seeds. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41:5149–5163. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou BO, Yue R, Murphy MM, Peyer JG, Morrison SJ. Leptin-receptor-expressing mesenchymal stromal cells represent the main source of bone formed by adult bone marrow. Cell stem cell. 2014;15:154–168. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.