During Drosophila dorsal closure, DPP and JNK signaling form a feed-forward loop that controls the specification and differentiation of leading edge cells to ensure robust morphogenesis.

Abstract

Development is robust because nature has selected various mechanisms to buffer the deleterious effects of environmental and genetic variations to deliver phenotypic stability. Robustness relies on smart network motifs such as feed-forward loops (FFLs) that ensure the reliable interpretation of developmental signals. In this paper, we show that Decapentaplegic (DPP) and JNK form a coherent FFL that controls the specification and differentiation of leading edge cells during Drosophila melanogaster dorsal closure (DC). We provide molecular evidence that through repression by Brinker (Brk), the DPP branch of the FFL filters unwanted JNK activity. High-throughput live imaging revealed that this DPP/Brk branch is dispensable for DC under normal conditions but is required when embryos are subjected to thermal stress. Our results indicate that the wiring of DPP signaling buffers against environmental challenges and canalizes cell identity. We propose that the main function of DPP pathway during Drosophila DC is to ensure robust morphogenesis, a distinct function from its well-established ability to spread spatial information.

Introduction

Mechanisms that achieve robustness evolved to cope with environmental stress or genomic instability. This buffering process, known as canalization (Waddington, 1959), stores genotypic diversity and minimizes phenotypic plasticity (Paaby and Rockman, 2014). When canalization is overwhelmed, cryptic genetic variations are unleashed for natural selection to act upon (Rutherford and Lindquist, 1998; Rohner et al., 2013). A well-known biological network that conveys robustness is the feed-forward loop (FFL), in which molecule A controls the expression of a branch component B, and A and B together act on a common target (Milo et al., 2002; Mangan and Alon, 2003). FFLs control patterning both in the Drosophila melanogaster embryo (Xu et al., 2005), the wing imaginal disc (Zecca and Struhl, 2007), and in the developing eye (Tsuda et al., 2002). In addition, miRNAs have been shown to form FFLs that regulate canalization (Posadas and Carthew, 2014).

Dorsal closure (DC) in the Drosophila embryo provides an elegant system to study robustness: hundreds of leading edge (LE) cells differentiate and act in concert to seal the dorsal opening in a process reminiscent of wound healing (Martin and Parkhurst, 2004; Belacortu and Paricio, 2011). LE cells are polarized, display strong adherent junctions, accumulate a dense microtubule network, and produce a trans-cellular actomyosin cable and filopodia (Jacinto et al., 2000, 2002; Kaltschmidt et al., 2002; Jankovics and Brunner, 2006; Fernández et al., 2007; Millard and Martin, 2008; Solon et al., 2009). The closure dynamics are highly reproducible at a given temperature, indicating that DC is a robust and quantifiable process (Kiehart et al., 2000; Hutson et al., 2003).

Two major developmental pathways control DC: the stress response pathway JNK acts upstream and induces the bone morphogenetic protein homologue Decapentaplegic (DPP; Glise and Noselli, 1997; Hou et al., 1997; Kockel et al., 1997; Riesgo-Escovar and Hafen, 1997). These two signaling pathways are crucial for DC since embryos mutant for either JNK or DPP pathway components fail to close dorsally and exhibit a dorsal open phenotype (Affolter et al., 1994; Glise et al., 1995). However, how JNK and DPP contribute to DC and how the signals are integrated in a robust manner remain unclear (Riesgo-Escovar and Hafen, 1997; Martin and Parkhurst, 2004; Ríos-Barrera and Riesgo-Escovar, 2013).

Here we report that DPP and JNK are wired in a coherent FFL that controls LE cell identity and differentiation. At the mechanistic level, we provide evidence that derepression by the transcription factor Brk is sufficient to mediate DPP input. We show that the DPP/Brk indirect branch of the FFL does not pattern the LE but can filter unwanted JNK signaling so that the developmental JNK input remains preserved. Interestingly, although the DPP/Brk indirect branch of the FFL is dispensable for DC at 25°C, it is critical at 32°C. We propose that DPP function during DC is to ensure the robust interpretation of the positional information provided by JNK. By being wired into the FFL, DPP signaling acts as a filter rather than a positional signal and fosters the canalization of morphogenesis.

Results

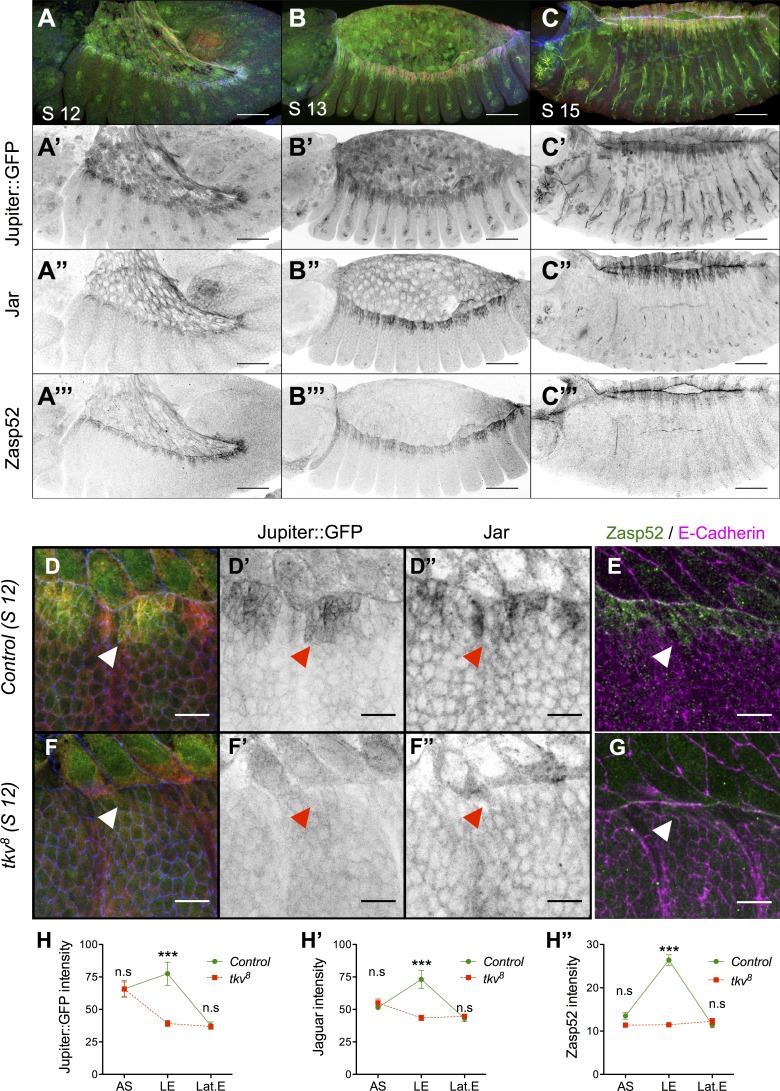

DPP is required for Jupiter, Jaguar (Jar), and Zasp52 accumulation at the LE

We first analyzed three markers that display a strong accumulation at the LE during DC: the myosin VI homologue Jar (Kellerman and Miller, 1992), the microtubule binding molecule Jupiter (Morin et al., 2001; Karpova et al., 2006), and Zasp52, which promotes integrin-mediated adhesion (Morin et al., 2001; Jani and Schöck, 2007). To determine whether DPP signaling is required for their accumulation, we analyzed these three markers in embryos mutant for the DPP receptor thick veins (tkv) at stage 12, during which morphological defects are not yet detected. We observed that the LE accumulation of all three markers is lost in tkv mutant embryos compared with controls (Fig. 1, D–G; see Fig. 1, H–H″ for quantifications). Therefore, LE accumulation of all three targets requires DPP activity.

Figure 1.

DPP signaling is required for Jupiter, Jar, and Zasp52 LE expression during DC. (A–C‴) Embryos at stage (S) 12 (A), 13 (B), and 15 (C) displaying Jupiter::GFP (green; gray in A′, B′, and C′), Jar (red; gray in A″, B″, and C″), and Zasp52 (blue; gray in A‴, B‴, and C‴). Bars, 50 µm. (D–G) Control (D and E) and tkv8 (F and G) stage 12 embryos marked for Jupiter::GFP (green in D and F; gray in D′ and F′), Jar (red in D and F; gray in D″ and F″) and E-Cadherin (blue in D and F), or Zasp52 (green in E and G) and E-Cadherin (magenta in E and G). Bars, 10 µm. (H–H″) Plot profile of Jupiter::GFP (n = 8), Jar (n = 8), and Zasp52 (n = 10) intensity in control and tkv8 embryos. AS, amnioserosa; LE, leading edge; Lat.E, lateral epidermis. (Two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post-hoc test: ***, P < 0.001.) Accumulation of Jupiter::GFP, Jar, and Zasp52 at the LE is lost in tkv− embryos (arrowheads). Error bars are means ± SEM.

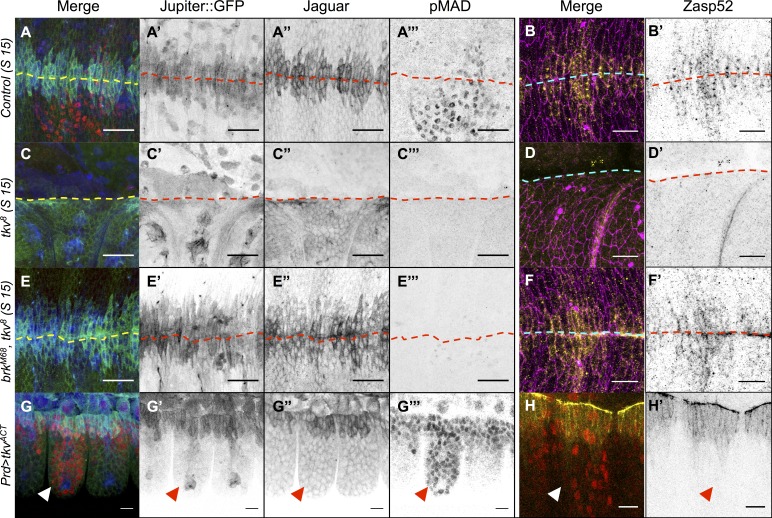

We next wondered how DPP mediates its effect on the markers. Indeed, DPP is known to induce two classes of targets that are both repressed by brinker (brk). Upon DPP action, Brk is transcriptionally repressed (Jaźwińska et al., 1999), leading to the induction of the first set of targets. The expression of the second set, however, requires the concomitant activation by the SMAD family of transcriptional activators (Affolter and Basler, 2007). Interestingly, loss of Brk is sufficient to rescue DC in the absence of pathway activation, suggesting that the DPP targets required for DC are expressed upon Brk derepression only (Marty et al., 2000). We hence tested whether removing Brk activity in the absence of DPP activation rescues Jar, Jupiter, and Zasp52 expression at the LE. To do so, we generated embryos double mutant for brk and tkv, to simultaneously disable DPP activation and prevent repression by Brk (Fig. S1 A). In these embryos, Jar, Jupiter, and Zasp52 expression is restored to wild type (Fig. 2, A–F′). In addition, brk overexpression represses the three markers (Fig. S1, B–B‴). We conclude that repression of brk alone is sufficient for the accumulation of Jar, Jupiter, and Zasp52 at the LE.

Figure 2.

DPP is required to derepress Jupiter, Jar, and Zasp52 but cannot induce them ectopically. (A–F′) Control (A and B), tkv8 (C and D), and brkM68, tkv8 (E and F) stage (S) 15 embryos marked for Jupiter::GFP (blue in A, C, and E; gray in A′, C′, and E′) Jar (green in A, C, and E; gray in A″, C″, and E″), phospho-Mad (pMad; red in in A, C, and E; gray in A‴, C‴, and E‴), Zasp52 (yellow in B, D, and F; gray in B′, D′, and F′), and E-Cadherin (magenta). The dashed lines delineate the midline. Accumulation of Jupiter::GFP, Jar, and Zasp52 at the LE is lost in tkv8 mutant embryos and restored in brkM68, tkv8 embryos. (J and K) Prd-Gal4, UAS-tkvACT embryos marked for Jupiter::GFP (blue in G; gray in G′), Jar (green in G; gray in G″), phospho-Mad (red in G; gray in G‴), or Zasp52::GFP (yellow in H; gray in H′) and phospho-Mad (red). Ectopic activation of the DPP pathway does not lead to Jupiter, Jar, or Zasp52 accumulation (arrowheads). Bars, 10 µm.

DPP does not delineate Jupiter, Jar, and Zasp52 expression pattern

DPP is the best example of a secreted morphogen, a factor that patterns gene expression in a concentration-dependent manner (Nellen et al., 1996). In the wing imaginal disc, Brk activity dictates the boundaries of the DPP targets Salm and Omb, whose expression patterns expand in brk− clones (Jaźwińska et al., 1999). In contrast, at the LE, the expression patterns of Jar, Jupiter, and Zasp52 remain unchanged in tkv brk or brk embryos (Fig. 2, E–F′; and Fig. S1, C–H‴). In addition, the phospho-Mad pattern is broader than the Jupiter, Jar, and Zasp52 pattern, suggesting that, instead of delineating the boundaries of the expression of these targets, DPP may fulfill a function different from its well-established patterning activity (Fig. 2, G and H; Dorfman and Shilo, 2001). We further confirmed that ectopic activation of the DPP pathway in paired stripes fails to induce these targets outside the LE, indicating that DPP does not define the boundary of the expression patterns of the three markers during DC (Fig. 2, G–H′). What then, is the factor that limits their expression pattern, and what is the biological significance of DPP control of Jar, Jupiter, and Zasp52?

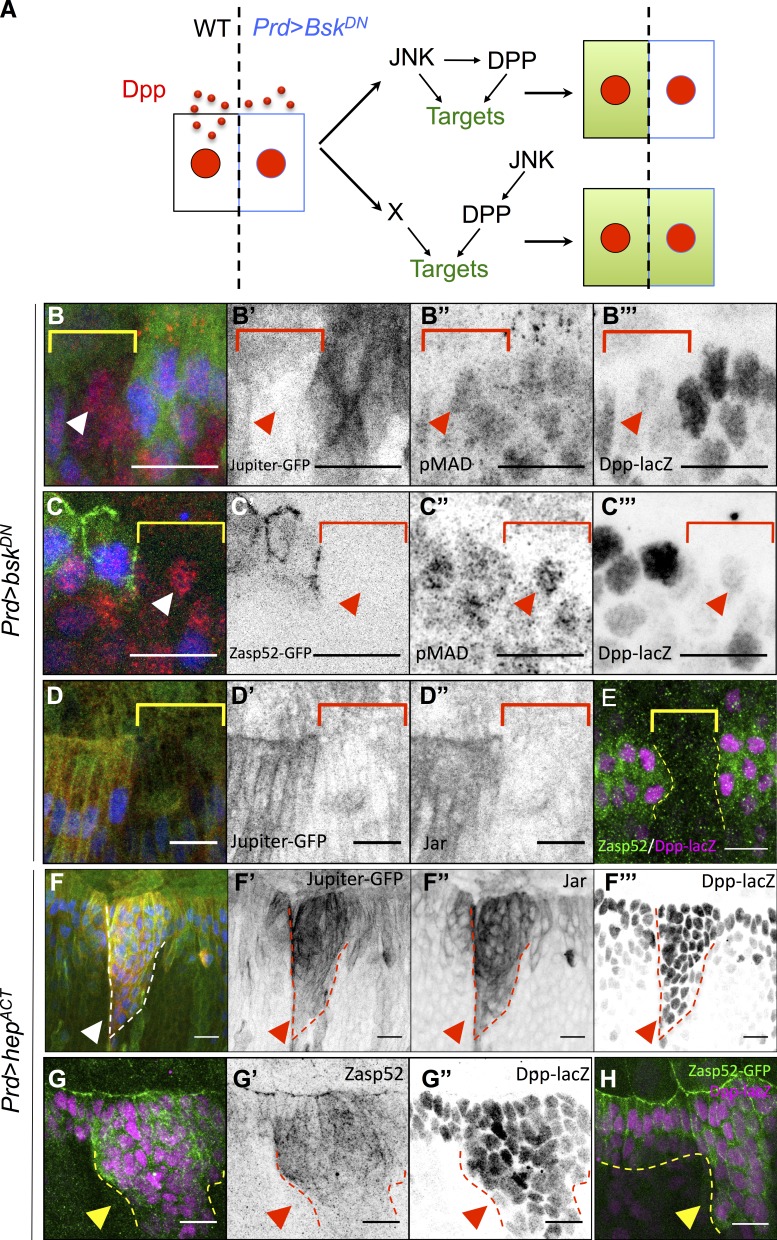

JNK and DPP are wired into a coherent FFL that controls LE cell differentiation

JNK acts upstream of DPP and determines LE identity (Glise and Noselli, 1997; Hou et al., 1997; Kockel et al., 1997; Riesgo-Escovar and Hafen, 1997). To test whether JNK activates the targets in parallel to DPP, we expressed a dominant-negative form of the JNK homologue basket (bsk) in paired stripes so that cells in the paired domain are deficient for JNK signaling but still receive DPP from their wild-type neighbors by diffusion (Fig. 3 A). We reasoned that if the expression of the markers does not require JNK activity in parallel to DPP, the markers should remain expressed in the cells in which JNK is affected as long as they receive DPP. We found that DPP produced by the neighboring cells efficiently induces Mad phosphorylation in the paired domain, yet the targets are not expressed (Fig. 3, B–E). Therefore, JNK acts both upstream and in parallel to DPP to control Jar, Jupiter, and Zasp52. To confirm that JNK directs the pattern of Jar, Jupiter, and Zasp52, we induced ectopic JNK signaling in paired stripes and used DPP-lacZ as a reporter of JNK activity. All the cells in which DPP-lacZ is induced also express Jar, Jupiter, and Zasp52 (Fig. 3, F–H). These observations indicate that JNK and DPP form a coherent FFL, in which JNK induces DPP, and both signals are absolutely required for target gene expression.

Figure 3.

JNK and DPP form a coherent FFL that regulates cell differentiation. (A) Experimental design. The wild-type (WT) cell (black rectangle) secretes DPP (red dots) that induces its pathway in all cells (red nuclei). The absence of target (green) in the Prd>BskDN cell abutting the wild-type cell indicates the presence of a JNK/DPP FFL. (B–C‴) Prd-Gal4, UAS-bskDN, Dpp-lacZ embryos marked for Jupiter::GFP (green in B; gray in B′) or Zasp52::GFP (green in C; gray in C′), phospho-Mad (red in B and C; gray in B″ and C″), and lacZ (blue in B and C; gray in B‴ and C‴). The brackets indicate the BskDN domain, where DPP-lacZ (blue) is off. Anti–phospho-Mad (red) indicates that all cells receive DPP. Jupiter (B) and Zasp52 (C) in green are excluded from the BskDN territory, even though DPP signaling is active (arrowheads), indicating that JNK acts also in parallel of DPP. (D–D″) Prd-Gal4, UAS-bskDN, Dpp-lacZ embryos marked for Jupiter::GFP (green in D; gray in D′) Jar (red in D; gray in D″) and lacZ (blue in D; gray in D‴). (E) Prd-Gal4, UAS-bskDN, Dpp-lacZ embryos marked for Zasp52::GFP and lacZ. All the markers are lost in the entire BskDN territory (brackets in B–D or dotted lines in E). (F) Prd-Gal4, UAS-hepACT, Dpp-lacZ, Jupiter::GFP embryos marked for Jupiter::GFP (green in F; gray in F′), Jar (red in F; gray in F″), and lacZ (blue in F; gray in F‴). (G–H) Prd-Gal4, UAS-hepACT, Dpp-lacZ embryos marked for lacZ (magenta in G and H; gray in G″) and Zasp52 (green in G; gray in G′) or Zasp52::GFP (green in H). Ectopic JNK activity (dotted lines) induces Jar, Jupiter, and Zasp52 accumulation (arrowheads). Bars, 10 µm.

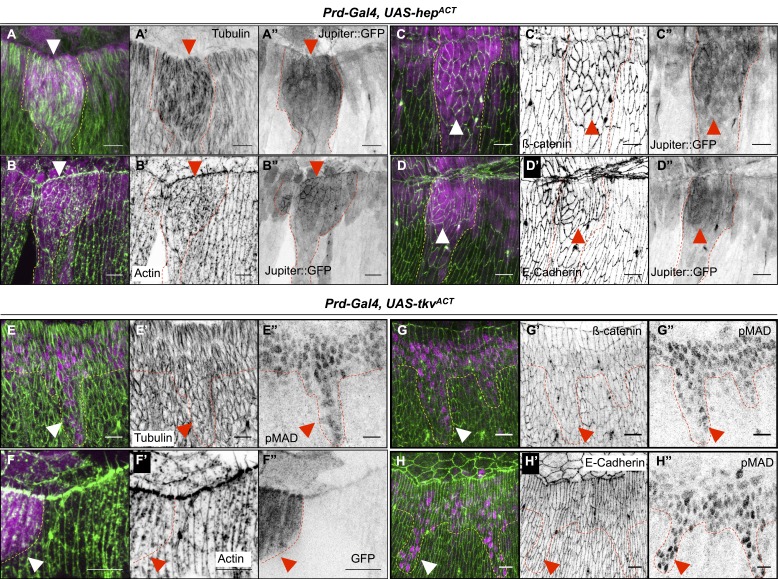

We next asked whether the FFL controls LE cell differentiation. We selectively inactivated in paired stripes, either JNK by using bskDN (Fig. 4, A–D‴) or DPP input by overexpressing brk (Fig. 4, E–H‴) and analyzed microtubule polarization, actomyosin cable, filopodia formation, and junctional integrity. Impairing either JNK or DPP signal affects the hallmarks of LE cell differentiation: First, microtubules fail to polarize and to accumulate (Fig. 4, A″ and E″). Second, filopodia and the actomyosin cable are absent (Fig. 4, B″, C″, F″, and G″). Last, both E-Cadherin and β-catenin expression are reduced, indicating weaker adhesion (Fig. 4, D″, D‴, H″, and H‴; see Fig. 4, I–N for quantifications). We conclude that both branches of the FFL are absolutely required for LE cell differentiation and morphogenesis.

Figure 4.

Cytoskeletal components crucial for DC are also regulated by the JNK/DPP FFL. (A–H‴) Prd-Gal4, UAS-bskDN, Jupiter::GFP embryos (A–D‴) and Prd-Gal4, UAS-brk, Jupiter::GFP (E–H‴) marked for Jupiter::GFP (green in all panels; gray in A′–H′), α-tubulin (magenta in A and E; gray in A″ and E″) or actin (magenta in B, C, F, and G; gray in B″, C″, F″, and G″), or β-catenin (red in D and H; gray in D″ and H″) and E-Cadherin (blue in D and H; gray in D‴ and H‴). In all panels, the BskDN or the Brk overexpression territory is marked by the absence of Jupiter::GFP (brackets), and the border between the wild-type and the BskDN or Brk overexpression territory is delineated by the dotted lines. (I–N) Quantification of microtubule intensity, actin cable intensity, and filopodia numbers. Error bars: ±SEM (for all panels, Mann–Whitney’s U test: **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). bskDN or brk overexpression affects microtubules, β-catenin, and DE-Cadherin accumulation as well as actin cable formation at the LE and filopodia (arrowheads in C″ and G″). Bars, 10 µm.

A prediction of this model is that ectopic JNK, but not ectopic DPP, should redirect lateral cells to the LE cell identity and path of differentiation. We tested this prediction by inducing either JNK activity or DPP signaling in stripes (Fig. 5, A–D″ and E–H″, respectively). As expected for an FFL, ectopic JNK induces ectopic accumulation of microtubules (Fig. 5, A–A″) and actin (Fig. 5, B–B″) as well as E-Cadherin and β-catenin (Fig. 5, C–D″). Conversely, ectopic activation of the DPP pathway has no effect on microtubules, actin, E-Cadherin, or β-catenin accumulation (Fig. 5, E–H″). Altogether, these data indicate that we identified a novel FFL that plays a pivotal role in LE cells specification and differentiation.

Figure 5.

Ectopic JNK but not ectopic DPP activity leads to accumulation of cytoskeletal components crucial for DC. (A–D″) Prd-Gal4, UAS-hepACT, Jupiter::GFP embryos marked for Jupiter::GFP (magenta in A–D; gray in A″–D″) and α-tubulin (green in A; gray in A′) or actin (green in B; gray in B′), β-catenin (green in C; gray in C′), or DE-Cadherin (green in D; gray in D′). In all panels, the ectopic JNK activity is marked by the ectopic accumulation of Jupiter::GFP (arrowheads) and is delineated by dotted lines. Ectopic JNK signaling leads to accumulation of microtubules, β-catenin, DE-Cadherin, and actin. (E–E″) Prd-Gal4, UAS-tkvACT embryo stained for phospho-Mad (magenta in E; gray in E″) and α-tubulin (green in E; gray in E′). (F–F″) Prd-Gal4, UAS-tkvACT, UAS-GFP embryos marked for GFP (magenta in F; gray in F″) and actin (green in F; gray in F′). (G–H″) Prd-Gal4, UAS-tkvACT embryos stained for phospho-Mad (pMad; magenta in G and H; gray in G″ and H″) and β-catenin (green in G; gray in G′) or E-Cadherin (green in H; gray in H′). In all panels, the ectopic DPP activity is marked by either ectopic phospho-Mad nuclei or the presence of GFP (arrowheads) and is delineated by dotted lines. Ectopic DPP signaling activity does not lead to any accumulation of microtubules, β-catenin, E-Cadherin, or actin. Bars, 10 µm.

The JNK/DPP FFL can filter unwanted JNK signaling

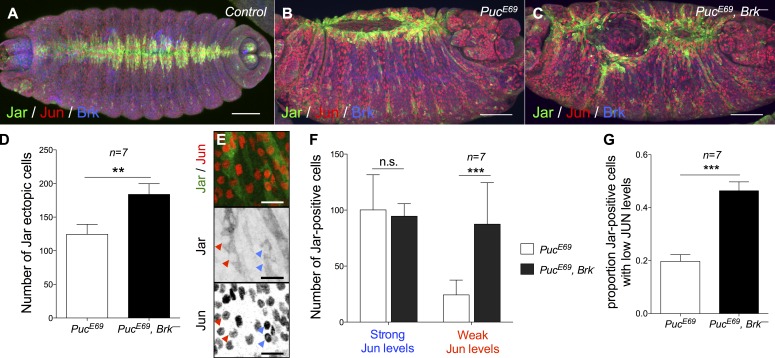

FFLs can act as filters of short bursts of signaling (Milo et al., 2002; Mangan and Alon, 2003), which are random noises that make biological processes error prone if unchecked. In this paradigm, signaling robustness is achieved in that the synchrony between the two branches of the FFL is absolutely required for a response to occur. If the direct signal switches off before the indirect signal fires, no response can be elicited. We reasoned that in the JNK/DPP FFL, brk-mediated repression is the sentinel that prevents unwanted JNK activity from specifying ectopic LE identity. To test this hypothesis, we needed to first produce a source of ectopic JNK signal that is nonuniform and subsequently verify whether the FFL can indeed filter out such unwanted JNK activity to canalize LE identity. A previous study and our observations indicate that puc mutant embryos display a salt-and-pepper pattern of ectopic JNK activation throughout the lateral epidermis, suggesting the presence of nonuniform, ectopic JNK signal that varies in strength (Martín-Blanco et al., 1998). To test whether the FFL can filter the ectopic JNK signal in puc embryos, we generated puc brk double mutants and found that the ectopic Jar expression and the morphological defects are magnified compared with puc single mutants, suggesting that more cells respond erroneously to the action of the unwanted JNK signal when the FFL is disabled (Fig. 6, A–D). A critical aspect of the FFL is that the filtering ability depends on the delay between the activation of the direct and the indirect branch: any signal shorter than the delay is filtered out. We reasoned that the uneven JNK activity pattern reflects signal duration and could provide us with a nice system to test whether transient and robust JNK inputs are discriminated by the FFL: weak Jun staining corresponds to short accumulation of Jun and reveals transient signaling; strong Jun staining corresponds to an accumulation of Jun synthesis over time and indicates robust signaling. We therefore compared Jar induction in cells displaying robust and weak Jun staining: although Brk activity does not modify Jar induction by robust ectopic JNK signaling, a cell that receives weak JNK signaling is ∼2.5 times more likely to wrongfully express Jar in a brk mutant (Fig. 6, E–G). We conclude that the FFL buffers weak ectopic JNK signaling to prevent the ectopic differentiation of lateral cells into LE cells.

Figure 6.

The JNK/DPP FFL filters weak ectopic JNK activity. (A–C) Control (A), PucE69 (B), and PucE69, brkM68 (C) stage 15 embryos stained for Jar, Jun, and Brk. Bars, 50 µm. (D) Quantification of Jar ectopic cells in the lateral epidermis. (n = 7; Mann–Whitney’s U test: **, P < 0.01.) Error bars: ±SEM. (E) Close-up of the lateral epidermis of a PucE69 embryo showing weak (red arrowheads) or strong (blue arrowheads) Jun expression. Bars, 10 µm. (F and G) Quantification of Jar expression in cells expressing low or high Jun levels in PucE69 versus PucE69, brkM68 embryos. (F: two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post-hoc test: ***, P < 0.001; G: Mann–Whitney’s U test: ***, P < 0.001.) Error bars: ±SEM. Brk represses Jar in about two thirds of the cells displaying weak Jun expression.

The JNK/DPP FFL canalizes DC

Having confirmed that the FFL filters unwanted JNK noise, we sought to test whether the indirect branch of the FFL canalizes morphogenesis in the presence of environmental perturbations. We compared how wild-type or FFL-deficient (brk−) embryos cope with thermal stress, a classical assay for robustness in Drosophila (Perry et al., 2010). At 25°C, brk mutants show wild-type Jar and Zasp52 expression and microtubule accumulation (Fig. 7, A–F). In contrast, brk mutants raised at 32°C display cells that ectopically express Jar and Zasp52 and accumulate microtubules, indicating that they differentiate into LE cells erroneously (Fig. 7, G–M; and Fig. S2, A–M). Therefore, brk canalizes LE specification by counteracting the deleterious effects of environmental stress. Next, we quantified DC dynamics in brk mutants at 32°C. Although closure speed is undistinguishable between wild-type and brk embryos at 25°C, a 1-h delay is recorded in brk at 32°C compared with wild type (Fig. 7, N and N′; Fig. S3; and Videos 1 and 2). Hence, brk activity renders embryonic morphogenesis more resilient to environmental challenge. Altogether, our data indicate that during DC, the DPP-mediated FFL canalizes LE identity to foster DC robustness (Fig. 8).

Figure 7.

The JNK/DPP FFL canalizes LE specification and fosters DC robustness. (A–L) Control (top) and brkM68 (bottom) embryos at 25°C (left) or 32°C (right) marked for Jar (yellow), Zasp52 (red), and Tubulin (green). Ectopic Jar, Zasp52, and microtubule accumulations are detected only in brkM68 embryos at 32°C (arrowheads). Bars, 10 µm. (M) Quantification of Jar ectopic cells in control and brkM68 embryos at 25°C or 32°C. Only brkM68 embryos at 32°C exhibit Jar ectopic cells. n ≥ 7. Two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post-hoc test: ***, P < 0.001. (N and N′) Width of the dorsal opening measured over time of control and brkM68 embryos imaged at 25°C or 32°C. Only brkM68 embryos at 32°C exhibit slower closure dynamics.

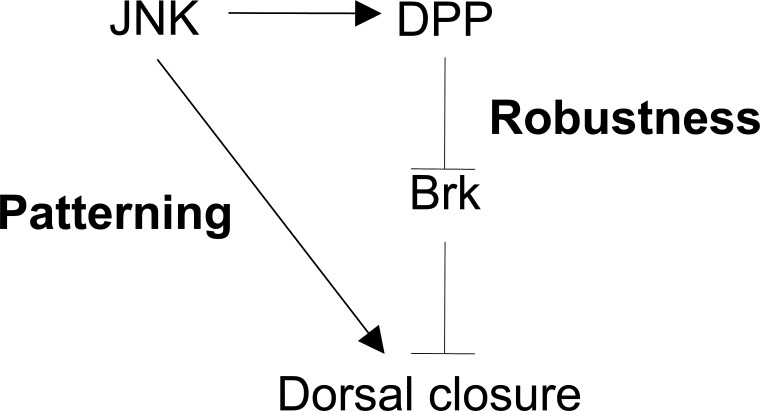

Figure 8.

Model of JNK and DPP wiring during DC. JNK and DPP form a coherent FFL that ensures a canalized and robust DC.

Discussion

We present a novel mechanism that weaves two classic signaling pathways into an FFL to canalize morphogenesis. This FFL is coherent as both JNK and DPP act positively and belong to the “and” type, as either signal alone does not trigger a response. Both experimental and computational evidence indicate that the general function of the indirect branch of a coherent FFL is to filter the input received by the direct branch (Mangan and Alon, 2003). Here, we find that during DC, patterning information is given by JNK, and the DPP/Brk branch filters this spatial information. In the presence of ectopic JNK generated by puckered loss of function, Brk filters out unwanted JNK signaling in two thirds of the cells displaying weak, but not strong, JNK activation. This is a prediction of the FFL model in which the network filters out only short bursts of signal and not longer, more robust signaling events. Interestingly, under normal laboratory conditions, at 25°C, Brk activity is not required for DC to proceed normally; LE markers are patterned correctly, and the dynamics of DC are nearly wild-type. Conversely, when embryos are subjected to thermal stress, at 32°C, Brk becomes critical to prevent the presence of ectopic LE cells in the lateral epidermis and to ensure proper closure dynamics. These observations provide strong evidence to support that DPP function during DC is to provide robustness to the system: under difficult conditions, phenotypic variation remains minimal, and cell identity remains canalized.

miRNAs are major players in the canalization of cell decisions in the face of environmental challenges (Posadas and Carthew, 2014): mir-7 stabilizes gene expression and allows the correct determination of sensory organs in flies subjected to temperature fluctuations (Li et al., 2009). miRNAs are posttranscriptional regulators that produce moderate but rapid effects on gene expression. This rapid action appears to have favored their recruitment into network motifs dedicated to tune gene expression in a prompt manner: a transcription factor controls the miRNA and both together control a common target, forming an FFL. The major difference between miRNA and DPP-mediated FFL is the time scale: compared with the swift-acting miRNAs, DPP needs to be translated, secreted, reach a threshold to activate its pathway, to finally repress brk transcription. The prediction is that DPP-mediated FFL filters JNK inputs that are on a long time scale: DPP would not only filter out JNK noise but could also filter out authentic JNK signaling that is important for nonpatterning functions. JNK is the main messenger of stress, and mechanisms must exist to distinguish stress-related and development-related JNK inputs within a given cell. This would explain why brk mutants close normally in favorable conditions. Environmental perturbations such as temperature excess are bound to have pleiotropic effects on biological systems. The FFL appears as the generic remedy to enforce robustness at several levels. Factors acting at specific kinetics form the indirect branches of FFLs adapted to specific needs: miRNAs cancel noise, and DPP ensures the proper interpretation of JNK signaling.

DPP is one of the main architects of fly development and as such fulfills many functions during embryogenesis: DPP specifies dorsal tissues, including the amnioserosa early and the dorsal epidermis at midembryogenesis (Ferguson and Anderson, 1992; Xu et al., 2005) and also directs dorsal tracheal migration (Vincent et al., 1997). At stage 5, DPP induces zerknüllt, and both DPP and Zerknüllt control the amnioserosa-specific gene Race, thus forming a coherent FFL (Xu et al., 2005). In addition, DPP also controls the spatial distribution of targets such as Ushaped, in both the dorsal epidermis and the amnioserosa (Lada et al., 2012). This regulation is important for the interaction between these two tissues that is critical for DC. Recently, a study reported how DPP can protect from JNK-induced apoptosis in the dorsal epidermis (Beira et al., 2014). They show that the DPP pathway repressor Schnurri directly represses the proapoptotic gene reaper. Therefore, JNK fails to induce reaper expression or apoptosis in the pannier domain. This indicates that JNK and DPP signaling pathways are reiteratively integrated during Drosophila embryogenesis. To get a full picture of this network, we will also need to integrate the two negative feedback loops mediated by Puc and scarface that dampen JNK activity (Martín-Blanco et al., 1998; Rousset et al., 2010). A likely possibility is that these feedback loops improve fidelity in signaling. Altogether, the dorsal epidermis provides an elegant model system to understand how different inputs are integrated to modulate cell decisions during development. Although some of these functions are paramount to cell specification, we show that some, such as the JNK/DPP FFL, can also counteract deleterious environmental stimuli and canalize development, a function distinct from DPP well-established, non–cell-autonomous patterning activity.

Materials and methods

Fly strains and genetics

We used the following lines: Canton-S (wild type), tkv8 (amorphic allele; Bloomington Stock Center [BL] 34509), BrkM68 (loss-of-function allele, see Jaźwińska et al., 1999), gift from M. Affolter (University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland), PucE69 (loss-of-function allele, see Martín-Blanco et al., 1998), Prd-Gal4 (BL 1947), upstream activation sequence (UAS)–tkvACT (BL 36537), gift from M. Grammont (Université de Lyon, Lyon, France), UAS-bskDN (BL 6409), UAS-hepACT (BL 9306), UAS-brk (brk coding sequence under the control of a promoter containing UAS sequence), gift from J. de Celis (Centro de Biología Molecular “Severo Ochoa,” Madrid, Spain), UAS-GFPNLS (BL 4776), Jupiter::GFP (GFP knock-in; BL 6836), Zasp52::GFP (GFP knock-in; BL 6838), and DPP-lacZNUCLEAR (lacZ-NLS coding sequence cloned after the BS 3.0 promoter of DPP, see Blackman et al., 1991). Unless otherwise indicated, all crosses were performed at 25°C.

Immunofluorescence and quantification

We used standard techniques of immunohistofluorescence as described in Ducuing et al. (2013). Embryos were dechorionated with bleach, fixed in a 1:1 mix of 4% PFA–heptane. Embryos were subsequently devitellinized by replacing the 4% PFA with methanol. Samples were incubated with primary antibodies, with fluorescent-coupled secondary antibodies and mounted in Vectashield.

We used the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-lacZ (1:1,000; Cappel), mouse anti-lacZ (1:250; G4644; Sigma-Aldrich), guinea pig anti-Brk (1:500; gift from G. Morata, Centro de Biología Molecular “Severo Ochoa,” Madrid, Spain), mouse anti-Jar 3C7 (1:100; Kellerman and Miller, 1992), rabbit anti-pMad (1:1,500; gift from P. ten Dijke, Leids Universitair Medisch, Leiden, Netherlands), rat anti–DE-Cadherin (1:333; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank [DSHB]), mouse anti-Armadillo (1:250; DSHB), mouse anti–α-tubulin (1:1,000; T6199; Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-Jun (1:10; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), and rabbit anti-Zasp52 (1:400; gift from F. Schöck, McGill university, Montreal, Quebec). For Brk, pMad, Jar, and Zasp52, antigen was a full-length protein. Secondary antibodies are from Invitrogen and were used at 1:500. We used the following secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor donkey anti–mouse 488, Alexa Fluor goat anti–mouse 633, Alexa Fluor goat anti–rat 546, Alexa Fluor donkey anti–rabbit 488, Alexa Fluor goat anti–rabbit 546, and Alexa Fluor goat anti–guinea pig 488. For 32°C experiments, embryos where first grown at 25°C and then shifted for 4 h at 32°C and immediately fixed after.

Phalloidin staining

Embryos were dechorionated with bleach and fixed in a 1:1 mix of 4% PFA–heptane. After PFA removal, embryos were stuck on double-sided tape, immerged in 0.1% Triton X-100 and PBS with Rhodamine Phalloidin (1:500; Sigma-Aldrich), and hand devitellinized with a needle. Devitellinized embryos were quickly rinsed twice with 0.1% Triton X-100 and PBS and mounted in Vectashield.

Image processing

Images were acquired on the acousto-optical beam splitter confocal laser-scanning microscope (SP5; Leica) with the following objectives: HC Plan Fluotar 20×, 0.5 multi-immersion (numerical aperture: 0.7), HCX Plan Apochromat 40× 1.25–0.75 oil (numerical aperture: 1.25), and HCX Plan Apochromat 63× 1.4–0.6 oil (numerical aperture: 1.4) using the acquisition software LAS AF (Leica) at the PLATIM imaging facility and analyzed with ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). Unless otherwise indicated, all images are projections of confocal sections.

Live imaging

Unless otherwise indicated, all crosses were performed at 25°C. Stage 10 or 11 embryos were staged and aligned in Halocarbon oil 27 (Sigma-Aldrich) and then imaged at 25°C or 32°C with a spinning disk (Leica), with a 20× dry objective (numerical aperture: 0.4) and a camera (iXon3; Andor Technology) using the acquisition software MetaMorph (Molecular Devices). brkM68/FM7 females were crossed with Jupiter::GFP males. In addition, wild-type females were crossed with Jupiter::GFP males as controls. Brk mutant embryos were identified by the absence of spontaneous movements at stage 17 and confirmed by the absence of hatching. For every sample, the length and width over time were normalized with the maximal length or maximal width, respectively.

Quantification and statistical analyses

We used the Prism software (GraphPad Software) to generate graphs. For Figs. 1, 4, 6, and 7 M, bar graphs represent means ± SEM. For Figs. 7 (N and N′) and S4, graphs represent the mean. Mann–Whitney’s U test was used to determine significant differences for Figs. 4 and 6 (D and G). For Figs. 1 (H–H″), 6 F, and 7 M, we used a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc test. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 describes the experimental strategy used to determine whether the three targets belong to the derepressed only or to the derepressed and induced class of DPP targets as well as the effects of the overexpression and the loss of function on the targets’ expression. Fig. S2 reports the effects of temperature on brk mutants. Fig. S3 displays the analysis of the dynamics of DCs in brk mutants at 25°C and 32°C. Video 1 is a live recording of the closure of embryos representative of the controls and brk mutants we analyzed at 25°C. Video 2 is a live recording of the closure of embryos representative of the controls and brk mutants we analyzed at 32°C. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.201410042/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the DROSO-TOOLS and PLATIM facilities of the UMS3444 and Bloomington and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for reagents. We thank Dali MA for the critical reading of this manuscript and Markus Affolter, Uri Alon, and Arezki Boudaoud for discussions.

This work was supported by a Chair from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique to S. Vincent.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- Brk

- Brinker

- DC

- dorsal closure

- DPP

- Decapentaplegic

- FFL

- feed-forward loop

- Jar

- Jaguar

- LE

- leading edge

- tkv

- thick veins

- UAS

- upstream activation sequence

References

- Affolter M., and Basler K.. 2007. The Decapentaplegic morphogen gradient: from pattern formation to growth regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8:663–674 10.1038/nrg2166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Affolter M., Nellen D., Nussbaumer U., and Basler K.. 1994. Multiple requirements for the receptor serine/threonine kinase thick veins reveal novel functions of TGF β homologs during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development. 120:3105–3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beira J.V., Springhorn A., Gunther S., Hufnagel L., Pyrowolakis G., and Vincent J.P.. 2014. The Dpp/TGFβ-dependent corepressor schnurri protects epithelial cells from JNK-induced apoptosis in Drosophila embryos. Dev. Cell. 31:240–247 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belacortu Y., and Paricio N.. 2011. Drosophila as a model of wound healing and tissue regeneration in vertebrates. Dev. Dyn. 240:2379–2404 10.1002/dvdy.22753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman R.K., Sanicola M., Raftery L.A., Gillevet T., and Gelbart W.M.. 1991. An extensive 3′ cis-regulatory region directs the imaginal disk expression of decapentaplegic, a member of the TGF-β family in Drosophila. Development. 111:657–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman R., and Shilo B.Z.. 2001. Biphasic activation of the BMP pathway patterns the Drosophila embryonic dorsal region. Development. 128:965–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducuing A., Mollereau B., Axelrod J.D., and Vincent S.. 2013. Absolute requirement of cholesterol binding for Hedgehog gradient formation in Drosophila. Biol. Open. 2:596–604 10.1242/bio.20134952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson E.L., and Anderson K.V.. 1992. Decapentaplegic acts as a morphogen to organize dorsal-ventral pattern in the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 71:451–461 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90514-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández B.G., Arias A.M., and Jacinto A.. 2007. Dpp signalling orchestrates dorsal closure by regulating cell shape changes both in the amnioserosa and in the epidermis. Mech. Dev. 124:884–897 10.1016/j.mod.2007.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glise B., and Noselli S.. 1997. Coupling of Jun amino-terminal kinase and Decapentaplegic signaling pathways in Drosophila morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 11:1738–1747 10.1101/gad.11.13.1738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glise B., Bourbon H., and Noselli S.. 1995. hemipterous encodes a novel Drosophila MAP kinase kinase, required for epithelial cell sheet movement. Cell. 83:451–461 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90123-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou X.S., Goldstein E.S., and Perrimon N.. 1997. Drosophila Jun relays the Jun amino-terminal kinase signal transduction pathway to the Decapentaplegic signal transduction pathway in regulating epithelial cell sheet movement. Genes Dev. 11:1728–1737 10.1101/gad.11.13.1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson M.S., Tokutake Y., Chang M.S., Bloor J.W., Venakides S., Kiehart D.P., and Edwards G.S.. 2003. Forces for morphogenesis investigated with laser microsurgery and quantitative modeling. Science. 300:145–149 10.1126/science.1079552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacinto A., Wood W., Balayo T., Turmaine M., Martinez-Arias A., and Martin P.. 2000. Dynamic actin-based epithelial adhesion and cell matching during Drosophila dorsal closure. Curr. Biol. 10:1420–1426 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00796-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacinto A., Wood W., Woolner S., Hiley C., Turner L., Wilson C., Martinez-Arias A., and Martin P.. 2002. Dynamic analysis of actin cable function during Drosophila dorsal closure. Curr. Biol. 12:1245–1250 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00955-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jani K., and Schöck F.. 2007. Zasp is required for the assembly of functional integrin adhesion sites. J. Cell Biol. 179:1583–1597 10.1083/jcb.200707045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankovics F., and Brunner D.. 2006. Transiently reorganized microtubules are essential for zippering during dorsal closure in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev. Cell. 11:375–385 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaźwińska A., Kirov N., Wieschaus E., Roth S., and Rushlow C.. 1999. The Drosophila gene brinker reveals a novel mechanism of Dpp target gene regulation. Cell. 96:563–573 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80660-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltschmidt J.A., Lawrence N., Morel V., Balayo T., Fernández B.G., Pelissier A., Jacinto A., and Martinez Arias A.. 2002. Planar polarity and actin dynamics in the epidermis of Drosophila. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:937–944 10.1038/ncb882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpova N., Bobinnec Y., Fouix S., Huitorel P., and Debec A.. 2006. Jupiter, a new Drosophila protein associated with microtubules. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 63:301–312 10.1002/cm.20124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellerman K.A., and Miller K.G.. 1992. An unconventional myosin heavy chain gene from Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Biol. 119:823–834 10.1083/jcb.119.4.823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehart D.P., Galbraith C.G., Edwards K.A., Rickoll W.L., and Montague R.A.. 2000. Multiple forces contribute to cell sheet morphogenesis for dorsal closure in Drosophila. J. Cell Biol. 149:471–490 10.1083/jcb.149.2.471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kockel L., Zeitlinger J., Staszewski L.M., Mlodzik M., and Bohmann D.. 1997. Jun in Drosophila development: redundant and nonredundant functions and regulation by two MAPK signal transduction pathways. Genes Dev. 11:1748–1758 10.1101/gad.11.13.1748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lada K., Gorfinkiel N., and Martinez Arias A.. 2012. Interactions between the amnioserosa and the epidermis revealed by the function of the u-shaped gene. Biol. Open. 1:353–361 10.1242/bio.2012497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Cassidy J.J., Reinke C.A., Fischboeck S., and Carthew R.W.. 2009. A microRNA imparts robustness against environmental fluctuation during development. Cell. 137:273–282 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangan S., and Alon U.. 2003. Structure and function of the feed-forward loop network motif. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:11980–11985 10.1073/pnas.2133841100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P., and Parkhurst S.M.. 2004. Parallels between tissue repair and embryo morphogenesis. Development. 131:3021–3034 10.1242/dev.01253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Blanco E., Gampel A., Ring J., Virdee K., Kirov N., Tolkovsky A.M., and Martinez-Arias A.. 1998. puckered encodes a phosphatase that mediates a feedback loop regulating JNK activity during dorsal closure in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 12:557–570 10.1101/gad.12.4.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty T., Müller B., Basler K., and Affolter M.. 2000. Schnurri mediates Dpp-dependent repression of brinker transcription. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:745–749 10.1038/35036383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millard T.H., and Martin P.. 2008. Dynamic analysis of filopodial interactions during the zippering phase of Drosophila dorsal closure. Development. 135:621–626 10.1242/dev.014001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milo R., Shen-Orr S., Itzkovitz S., Kashtan N., Chklovskii D., and Alon U.. 2002. Network motifs: simple building blocks of complex networks. Science. 298:824–827 10.1126/science.298.5594.824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin X., Daneman R., Zavortink M., and Chia W.. 2001. A protein trap strategy to detect GFP-tagged proteins expressed from their endogenous loci in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:15050–15055 10.1073/pnas.261408198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nellen D., Burke R., Struhl G., and Basler K.. 1996. Direct and long-range action of a DPP morphogen gradient. Cell. 85:357–368 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81114-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paaby A.B., and Rockman M.V.. 2014. Cryptic genetic variation: evolution’s hidden substrate. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15:247–258 10.1038/nrg3688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry M.W., Boettiger A.N., Bothma J.P., and Levine M.. 2010. Shadow enhancers foster robustness of Drosophila gastrulation. Curr. Biol. 20:1562–1567 10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posadas D.M., and Carthew R.W.. 2014. MicroRNAs and their roles in developmental canalization. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 27:1–6 10.1016/j.gde.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesgo-Escovar J.R., and Hafen E.. 1997. Drosophila Jun kinase regulates expression of decapentaplegic via the ETS-domain protein Aop and the AP-1 transcription factor DJun during dorsal closure. Genes Dev. 11:1717–1727 10.1101/gad.11.13.1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ríos-Barrera L.D., and Riesgo-Escovar J.R.. 2013. Regulating cell morphogenesis: the Drosophila Jun N-terminal kinase pathway. Genesis. 51:147–162 10.1002/dvg.22354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner N., Jarosz D.F., Kowalko J.E., Yoshizawa M., Jeffery W.R., Borowsky R.L., Lindquist S., and Tabin C.J.. 2013. Cryptic variation in morphological evolution: HSP90 as a capacitor for loss of eyes in cavefish. Science. 342:1372–1375 10.1126/science.1240276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousset R., Bono-Lauriol S., Gettings M., Suzanne M., Spéder P., and Noselli S.. 2010. The Drosophila serine protease homologue Scarface regulates JNK signalling in a negative-feedback loop during epithelial morphogenesis. Development. 137:2177–2186 10.1242/dev.050781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford S.L., and Lindquist S.. 1998. Hsp90 as a capacitor for morphological evolution. Nature. 396:336–342 10.1038/24550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solon J., Kaya-Copur A., Colombelli J., and Brunner D.. 2009. Pulsed forces timed by a ratchet-like mechanism drive directed tissue movement during dorsal closure. Cell. 137:1331–1342 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda L., Nagaraj R., Zipursky S.L., and Banerjee U.. 2002. An EGFR/Ebi/Sno pathway promotes delta expression by inactivating Su(H)/SMRTER repression during inductive notch signaling. Cell. 110:625–637 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00875-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent S., Ruberte E., Grieder N.C., Chen C.K., Haerry T., Schuh R., and Affolter M.. 1997. DPP controls tracheal cell migration along the dorsoventral body axis of the Drosophila embryo. Development. 124:2741–2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddington C.H.1959. Canalization of development and genetic assimilation of acquired characters. Nature. 183:1654–1655 10.1038/1831654a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M., Kirov N., and Rushlow C.. 2005. Peak levels of BMP in the Drosophila embryo control target genes by a feed-forward mechanism. Development. 132:1637–1647 10.1242/dev.01722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zecca M., and Struhl G.. 2007. Recruitment of cells into the Drosophila wing primordium by a feed-forward circuit of vestigial autoregulation. Development. 134:3001–3010 10.1242/dev.006411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.