Abstract

The vasculature is a prominent component of the subventricular zone neural stem cell niche. Although quiescent neural stem cells physically contact blood vessels at specialised endfeet, the significance of this interaction is not understood. In contrast, it is well established that vasculature-secreted soluble factors promote lineage progression of committed progenitors. Here we specifically investigated the role of cell-cell contact-dependent signalling in the vascular niche. Unexpectedly, we find that direct cell-cell interactions with endothelial cells enforces quiescence and promotes stem cell identity. Mechanistically, endothelial ephrinB2 and Jagged1 mediate these effects by suppressing cell-cycle entry downstream of mitogens and inducing stemness genes to jointly inhibit differentiation. In vivo, endothelial-specific ablation of either of the genes which encode these proteins, Efnb2 and Jag1 respectively, aberrantly activates quiescent stem cells, resulting in depletion. Thus, we identify the vasculature as a critical niche compartment for stem cell maintenance, furthering our understanding of how anchorage to the niche maintains stem cells within a pro-differentiative microenvironment.

Adult stem cells reside in specialized microenvironments, or niches, that maintain them as quiescent, undifferentiated cells to sustain life-long regeneration1-3. However, the molecular nature of the signals involved in stem cell maintenance or the cell types from which they originate within the niche remain largely unknown. The subventricular zone (SVZ) is one of the two germinal niches of the adult mammalian brain, where new neurons are continuously produced throughout life. Neurogenesis is initiated from quiescent type-B stem cells that upon activation to a proliferative state (activated type-B cells), give rise to type-C transit-amplifying progenitors, which in turn generate type-A neuroblasts. Type-A cells then migrate along the rostral migratory stream (RMS) to the olfactory bulb where they differentiate into mature interneurons4-6. The SVZ is extensively vascularized by a rich plexus of blood vessels5. Both type B and type-C precursor cells lie in close proximity to the vasculature, but their physical interactions with the vessels are very distinct. Type-B stem cells extend long projections that make stable contact with endothelial cells through specialized endfeet, whereas type-C progenitors contact the endothelium at smaller sites, indicative of a more transient interaction7-9. It is well established that soluble factors secreted by endothelial cells promote neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation, indicating that the vascular niche plays an important role in promoting lineage progression of committed progenitors through soluble secreted cues9-14. In contrast, the functional significance of the intimate physical association between quiescent type-B stem cells and endothelial cells is currently unknown.

Direct cell-cell interactions mediated by integral membrane proteins are critical players in stem cell maintenance15. Among these, Eph and Notch signalling play important roles in many stem cell niches16,17. Eph receptor tyrosine kinases and their membrane-bound ephrin ligands mediate cell-cell communication between neighboring cells to control cell migration, survival and proliferation through multiple effector pathways16. Notch receptors are activated by ligands of the Delta-like or Jagged families presented by adjacent cells and, upon proteolytic cleavage of their intracellular domains (NICD), translocate to the nucleus to modulate transcription17. In the SVZ, Eph signalling has been linked to the regulation of proliferation and identity and Notch signalling to stem cell maintenance, but little is known about how these pathways are themselves regulated within the niche19-21.

Here we systematically investigated whether, and how, direct cell-cell interactions with the endothelium regulate neural stem cell behaviour in culture and in the SVZ in vivo. Intriguingly, we discovered that the vasculature maintains quiescent neural stem cells through ephrinB2 and Jagged1. Our results provide important insights into the mechanisms by which the shared niche microenvironment both maintains quiescent stem cells and directs their differentiation.

Endothelial cell contact enforces quiescence and maintains identity

In vivo, SVZ progenitors contact blood vessels at sites devoid of astrocyte and pericyte coverage and are thus directly juxtaposed to endothelial cells8. To mimic this interaction, we seeded SVZ postnatal neural precursor cells (NPC) or adult neural stem cells (aNSC) in direct co-culture with endothelial cells for 24h in NPC growth media, which includes EGF and FGF. We used three types of murine endothelial cells for these experiments: primary brain microvascular endothelial cells (bmvEC), the brain microvascular endothelial cell line bEND3.1 (bEND) or conditionally immortalised pulmonary endothelial cells (pEC). Immunostaining for endothelial markers confirmed that all endothelial cells retained viability and endothelial character in these conditions (not shown). Within 18h of seeding, we observed a dramatic morphological change in the NPC and aNSC co-cultures (+bEND, +bmvEC and +pEC) compared to control monocultures (−), with precursors on endothelial cells forming clusters that maintained contact with the endothelial monolayer, but frequently displayed a neurosphere-like morphology (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1h and j). This effect was not due to increased cell death (Supplementary Fig. 1a), soluble factors secreted by the endothelial cells or higher co-culture density. Indeed, transwell co-culture with bEND or bmvEC (+Sol) in the absence of physical contact (Fig. 1a), or culture of the stem cells at high density (not shown), had no effect on NPC morphology. Instead, time-lapse microscopy revealed that endothelial cell contact switched NPC migration from repulsion to attraction, indicative of a change in the adhesive properties of the NPCs (Supplementary video 1 and 2)22. Consistent with these results, NPC clustering correlated with an accumulation of the adhesion molecule N-cadherin at cell-cell contacts and could be disrupted by overexpression of dominant-negative constructs (DN-Ncad) in NPC (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

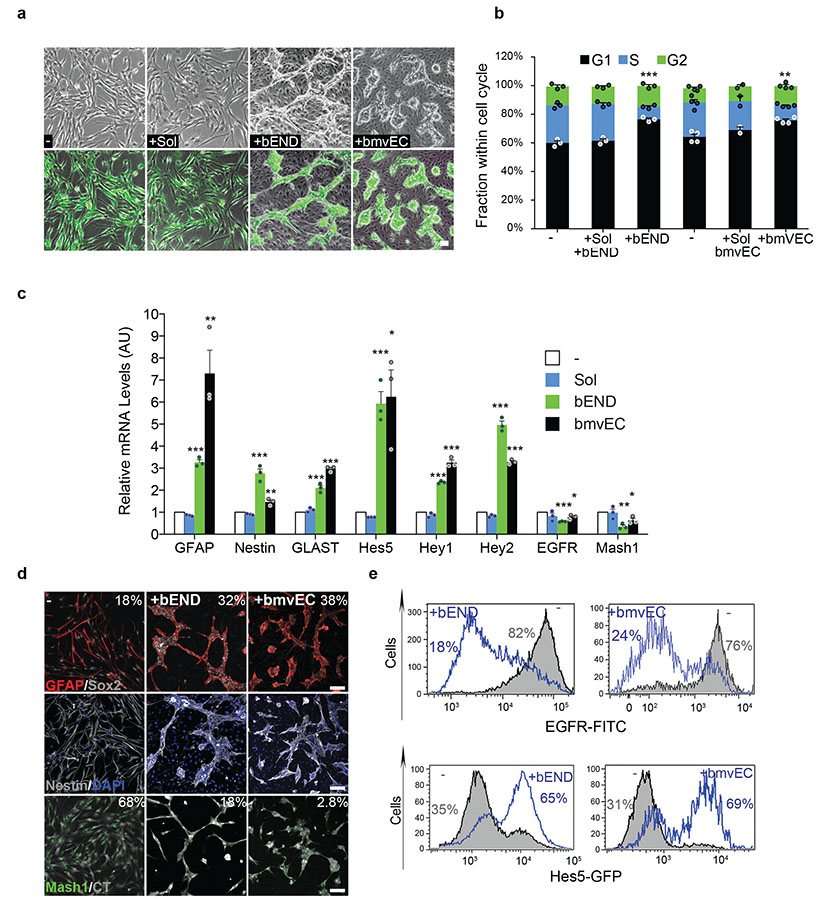

Figure 1. Endothelial cell contact enforces neural stem cell quiescence and promotes stem cell identity.

(a) Phase contrast and fluorescence images of cell-tracker labelled (green) SVZ cells cultured alone (−), in the presence of endothelial cell-secreted soluble factors (+Sol) and in direct co-culture with indicated endothelial cells (+bEND, +bmvEC). Cultures were imaged 24h after seeding. Merged images are shown for clear identification of the NPC in mixed cultures. (b) Quantification of PI-BrdU FACS profiles of cultures described in (a) following a 1 hour BrdU pulse. For this and all later experiments NPC were separated from endothelial cells prior to analysis (n=3 dishes from independent experiments for all bEND, n=2 for Sol bmvEC transwell and n=4 for bmvEC cocultures). Error bars denote s.e.m. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. (c) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mRNA levels of type-B and type-C marker genes in the indicated culture conditions expressed as fold change relative to control NPC monocultures (n=3 RNA extract from independent experiments). Error bars denote s.d. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. (d) Representative immunofluorescence images of NPC seeded alone (−) or in coculture with endothelial cells (+bEND, +bmvEC) for 24h and stained for the indicated type-B and type-C markers. All numbers embedded in the figures indicate the percentage of marker positive cells in each condition. (e) Representative FACS profiles and quantification of EGFR positive cells in the same cultures as in (d). (f) FACS plots and quantification of GFP+ NPCs isolated from Hes5-GFP reporter mice and cultured as in (d). For these and all later experiments for which n<5, individual data point are shown as dots. Source data in Supplementary table 1. For this and all later figures ***=p<0.001, **=p<0.01, *=p<0.05. Scale bars: a=30μm; d=75μm

To understand whether this phenotype correlated with a functional change in NPCs, we first examined proliferation of NPC seeded alone or with endothelial cells in growth media. Following a 1h BrdU pulse, all cells were separated from endothelial cells and subjected to FACS analysis to determine their cell-cycle profiles. We included a transwell co-culture control to assess the contribution of endothelial-secreted factors, which were shown to promote NPC proliferation in mitogen-free culture10. Strikingly, direct cell-cell contact with all endothelial cells inhibited NPC and aNSC proliferation, resulting in a strong reduction in S phase and an increase in G0-G1 (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1c, d). The cell-cycle arrest was not mediated by homotypic contact inhibition because it occurred in sparse co-cultures and NPCs infected with DN-N-cad, which lack adherens junctions, arrested on bEND to a similar extent as vector-infected controls (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Moreover, the cell cycle profiles of NPC+Sol and aNSC+Sol were indistinguishable from those of NPC or aNSC alone (as expected for cells in mitogens), indicating that the arrest was also independent of secreted factors and instead solely mediated by heterotypic cell-cell interactions with endothelial cells.

Next, we assessed stem cell identity in all culture conditions by measuring expression of type-B and type-C markers by qPCR23. We found that direct cell-cell contact with all endothelial cells, but not soluble factors alone, significantly increased type-B and downregulated type-C genes (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1f, g). These mRNA changes correlated with a similar change at the cellular level, as judged by analysis of marker proteins and Hes5 activation in Hes5-GFP NPC reporter cells (Fig. 1d-e and Supplementary Fig. 1h-k). Thus, endothelial contact promotes a quiescent type-B-like fate.

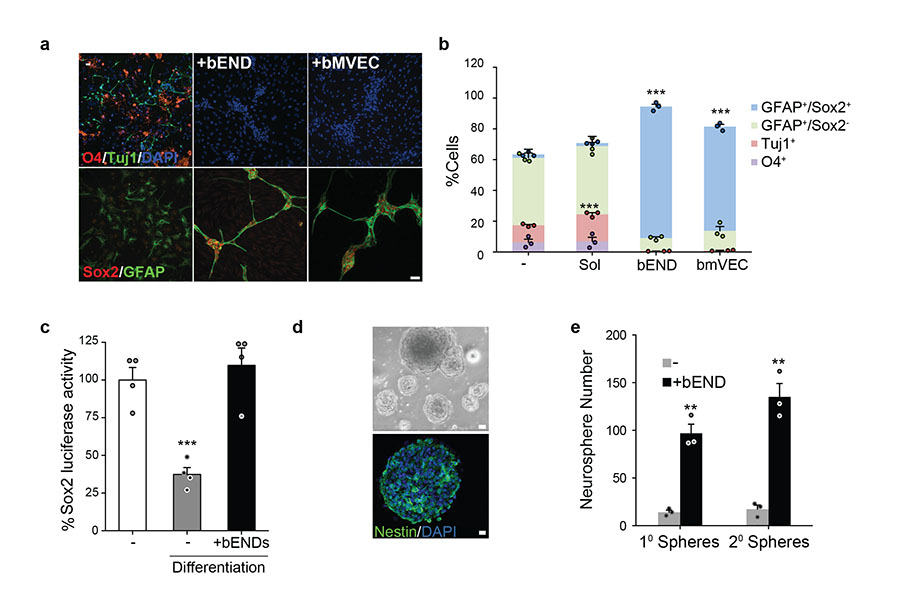

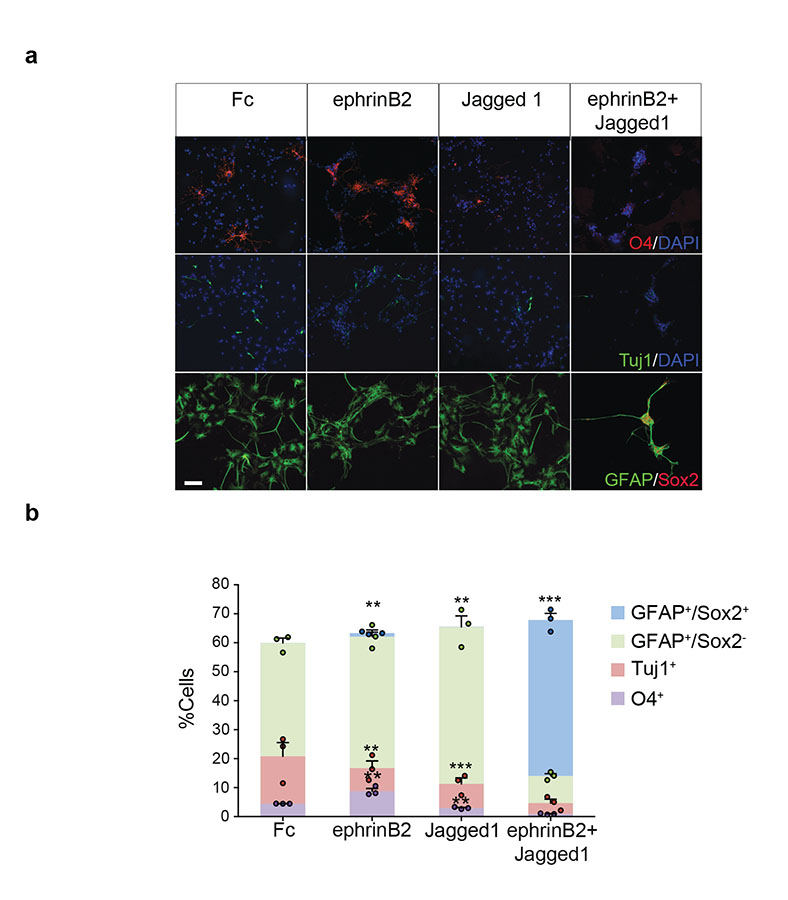

To address whether endothelial contact maintains a type-B phenotype also in pro-differentiative conditions, we differentiated NPC alone, in transwell or direct co-culture with bEND or bmvEC by mitogen removal (these conditions did not affect endothelial cells, Supplementary Fig. 2a). As expected, NPC alone gave rise to Tuj1+ neuroblasts, O4+ oligodendrocytes and GFAP+Sox2− astrocytes. In agreement with previous reports, endothelial secreted factors increased NPCs neurogenesis with no significant change in gliogenesis10. In contrast, differentiation into all three lineages was inhibited by direct cell-cell contact with bEND or bmvEC, as judged by the absence of Tuj1+, O4+ and GFAP+Sox2− cells (Fig. 2a, b). This was not due to NPCs acquiring endothelial fate, as reported in other systems24 (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Instead, NPCs cocultured with endothelial cells were maintained as multipotent GFAP+Sox2+ type-B-like cells with high Sox2 activity, which self-renewed and differentiated upon removal from the endothelium (Fig. 2c-e and Supplementary Fig. 2b). Similar results were obtained with aNSC (Supplementary Fig. 2c), confirming that the response to endothelial contact is independent of developmental stage. Consistent with this, type-B markers remained elevated in co-cultures compared to monocultures, whereas genes and proteins associated with neuroglial differentiation were downregulated (Supplementary Fig. 2d, e)25-27. Thus, direct cell-cell interactions with endothelial cells override extrinsic mitogenic cues and intrinsic differentiation programs to inhibit proliferation and differentiation, thereby maintaining neural precursors as quiescent, type-B-like stem cells.

Figure 2. Endothelial cells inhibit differentiation through direct cell-cell contact.

(a) Representative immunofluorescence images of neural stem cells seeded alone (−), or in direct co-culture with endothelial cells (+bEND, +bmvEC), induced to differentiate for 4 days and stained for the indicated proteins. (b) Quantification of neurons (Tuj1+), oligodendrocytes (O4+), astrocytes (GFAP+Sox2−) and type-B-like stem cells (GFAP+Sox2+) in the conditions depicted in the conditions depicted in panel a and in transwell co-culture (+Sol) (n=3 independent experiments each pooled from duplicate cultures). For each experiment a minimum of 200 cells across randomly selected fields of view was counted. Error bars denote s.e.m. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. (c) Sox2 promoter activity of NPCs transiently expressing luciferase reporter constructs cultured in factors or in differentiation media, either alone (−) or in the presence of endothelial cells (+bEND). Data are normalized to control cultures and expressed as mean±s.e.m. (n=4 experiments each pooled from triplicate lysates). Two-tailed paired Student’s t-test. (d) Neurosphere formation assay. Following differentiation, NPC cultured alone (−) or with bEND were dissociated and seeded in suspension to assess neurosphere forming potential. Representative phase contrast images (top) and immunofluorescence image (bottom) of neurospheres derived from NPC+bEND cultures stained for the pluripotency marker nestin (green) and counterstained for DAPI (blue). (e) Quantification of neurospheres formed from differentiated NPC monocultures (−) or cocultured with bEND (bEND). (n=3 experiments each pooled from duplicate dishes). Error bars denote s.e.m. Two-tailed paired Student’s t-test. Each dot represents an independent experiment. Source data in Supplementary table 1. Scale bars: a=50μm; d=20μm.

EphrinB2 attenuates MAPK to induce quiescence

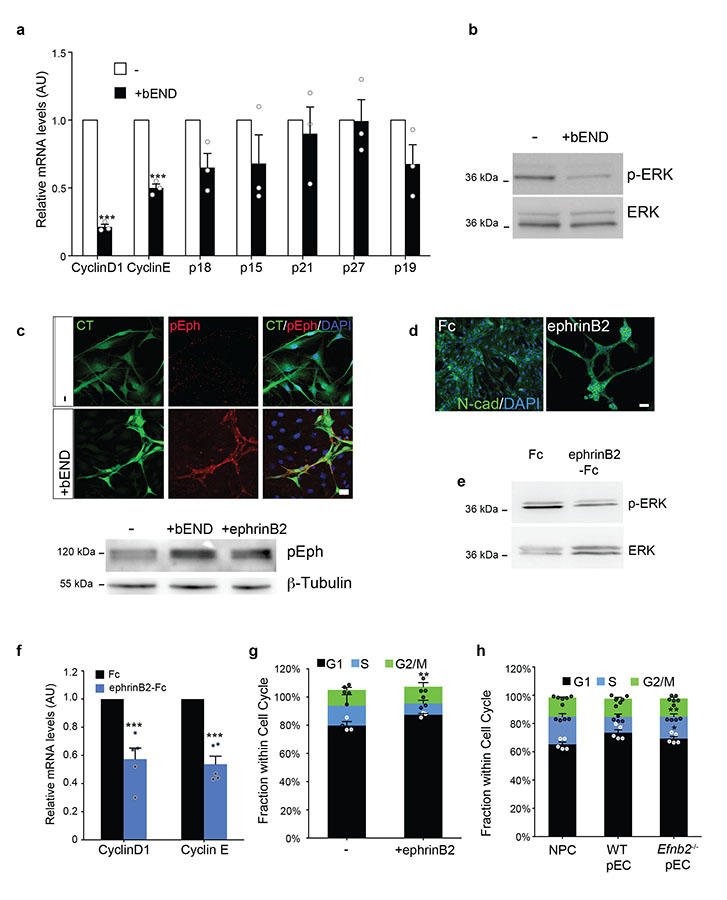

We next investigated the molecular mechanisms that underlie the cell-cycle arrest on endothelial cells. Because NPC arrested in G0-G1 upon endothelial contact, we measured expression of cell cycle regulators of the G1-S transition by qPCR. Whereas none of the CDKIs tested changed, we found a significant decrease in CyclinD and CyclinE levels on bEND (Fig. 3a). As CyclinD levels are controlled by growth factor receptors through MAPK28, we assessed phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK) levels in NPC+bEND and NPC controls and found that endothelial contact strongly suppressed ERK activation (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, treatment of NPC with the MEK inhibitor U0126 downregulated CyclinD, resulting in cell-cycle arrest. Conversely, overexpression of CyclinD in NPC rescued bEND-induced cell-cycle arrest (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Thus, contact with endothelial cells dampens MAPK signalling downstream of extrinsic mitogens to downregulate CyclinD levels and prevent cell-cycle entry.

Figure 3. Neural precursor cell proliferation on endothelial cells is inhibited by ephrinB2 ligands.

(a) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mRNA levels of the indicated cell-cycle regulators in NPC cultured on their own (−) or together with endothelial cells (+bEND) in growth media for 24h (n=3 RNA extracts from independent experiments). Error bars denote s.d. Two-tailed paired Student’s t-test. (b) Western blot analysis of p-ERK and total ERK levels in NPC cultured alone (−) or with endothelial cells (+bEND) for 24h under the same conditions. (c) Top: Representative immunofluorescence images of cell-tracker labelled (green) NPC in monoculture or co-culture with endothelial cells (unlabelled) and pure endothelial cell control cultures stained for p-Eph (red). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Bottom: western analysis of pEph levels in NPC cultured alone (−), on bEND or ephrinB2-Fc for 24h, β-tubulin is used as loading control. (d) Immunofluorescence staining for N-cadherin (green) of NPC seeded on clustered ephrinB2-Fc ligands or Fc controls. (e) Western analysis of p-ERK and total ERK levels in NPC cultured on ephrinB2-Fc or Fc ligands for 24h. (f) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of cyclinD1 and cyclinE mRNA levels in NPC stimulated with ephrinB2-Fc or Fc proteins (n=5 RNA extracts from independent experiments). Error bars denote s.d. Two-tailed paired Student’s t-test. (g) Quantification of NPC cell cycle profiles by FACS. Cells were seeded on Fc or ephrinB2-Fc for 24h and pulsed with BrdU for 1h (n=3 dishes from independent experiments). Error bars denote s.e.m. Each dot represents an independent experiment. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. (h) Quantification of FACS cell cycle profiles of NPC in monoculture (−) or coculture with wild type (+WT pEC) or Efnb2 knock-out (Efnb2−/− pEC) endothelial cells, measured by FACS (n=5 independent experiments). Error bars denote s.e.m. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. Source data in Supplementary table 1. Scale bars: c=30μm; d=50μm. Uncropped images of blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 7.

Ephs are among few receptor tyrosine kinases known to attenuate MAPK signalling downstream of mitogens16,29. Coupled with the observed changes in migration, this led us to hypothesize a role for Eph-ephrin signalling in our system30. Western analysis for activated Eph (p-Eph) detected high levels of p-Eph in NPC upon endothelial contact (Fig. 3c). As ephrinB2 is the most highly expressed ephrin in endothelial cells31, we asked whether ephrinB2 is the ligand responsible by treating NPCs with recombinant ephrinB2-Fc or Fc controls. Strikingly, ephrinB2 induced similar clustering to co-culture with endothelial cells, with NPC forming N-cadherin enriched neurospheres (Fig. 3d). Furthermore, stimulation with ephrinB2 ligands, but not Fc controls, was sufficient to reduce ERK phosphorylation and CyclinD/E mRNA levels and arrested NPC and aNSC in G0-G1 to the same extent as endothelial cells in a CyclinD-dependent manner (Fig. 3e-g and Supplementary Fig. 1l and 3b). In contrast, ephrinB2 treatment only partially modulated type-B marker expression independently of ERK (see GFAP, Supplementary Fig. 1m and 3c-e), indicative of additional mechanisms. To address whether ephrinB2 is also necessary for the cell-cycle arrest on endothelial cells, we cocultured NPCs with wild type or Efnb2−/− pECs and compared cell-cycle profiles by FACS (Fig. 3h; for efficiency of Efnb2 deletion see Supplementary Fig. 3f). Importantly, whereas NPC became quiescent on wild-type cells, endothelial deletion of Efnb2 rescued the cell-cycle arrest to a large extent, confirming that endothelial ephrinB2 plays a prominent role in enforcing NPC quiescence.

Jagged1 promotes type-B stem cell identity

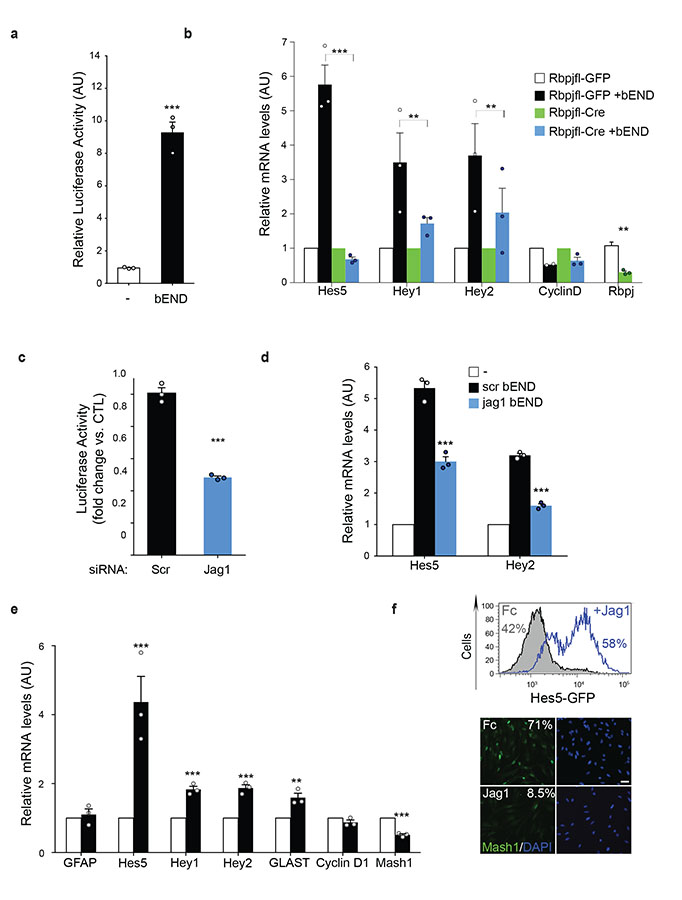

Many of the type-B genes upregulated by endothelial cell-contact are Notch targets, which has been shown to maintain SVZ type-B cells19,32. Therefore, we measured Notch activity using Hes5-luciferase reporter constructs and found a strong increase in NPC with bEND compared to controls (Fig. 4a). Consistent with this, inhibition of Notch signalling by genetic deletion of Rbpj in NPCs or pharmacological blockade of γ-secretase with DAPT, abolished the induction of Notch targets (Fig. 4b and Supplementary 4a). Interestingly, Notch inhibition had no effect on cyclinD, confirming that Eph-ephrin signalling is the main mediator of the G0-G1 arrest through MAPK-CyclinD. To rule out the possibility that Notch activation might be due to increased homotypic cell-cell interactions induced by ephrinB2, we measured Notch targets in DN-Ncad- and vector-transduced NPC cocultured with bEND and found a similar induction in both (Supplementary Fig. 4b), demonstrating that heterotypic cell-cell interactions activate Notch.

Figure 4. Endothelial Jagged1 ligands maintain the type-B phenotype.

(a) Hes-5 promoter activity in NPC transiently transfected with luciferase reporter constructs and cultured either alone (−) or with endothelial cells (+bEND). (n=3 experiments each pooled from triplicate lysates). Two-tailed paired Student’s t-test. (b) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mRNA levels of stated Notch target genes and CyclinD in RBPJflox/flox NPC infected with Adeno-GFP or Adeno-Cre viruses and cultured alone or with endothelial cells (+bEND) (n=3 RNA extracts from independent experiments). Two-tailed paired Student’s t-test. (c) Hes-5 luciferase reporter activity in NPC cocultured with scrambled siRNA (Scr) or Jag1 knock-down bEND cells (n=3 experiments pooled from triplicate lysates). Two-tailed paired Student’s t-test. (d) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the indicated Notch target genes in NPC cultured in the absence (−) or presence of Scr siRNA-treated endothelial cells and in the presence of Jag1-knock down endothelial cells (n=3 RNA extracts from independent experiments). One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. (e) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of indicated Notch target genes in NPC cultured on Fc (Fc) control proteins or Jagged1-Fc (n=3 RNA extracts from independent experiments). Two-tailed paired Student’s t-test. All bar graphs show mean±SEM. Each dot represents an independent experiment. Source data in Supplementary table 1. (f) top: representative FACS analysis and quantification of GFP+ cells in Hes5-GFP reporter NPC cultures treated with Fc or Jagged1 (Jag1) ligands. Bottom: representative immunofluorescence images of Fc and Jagged1 treated NPCs stained for Mash1 (green) and DAPI (blue). Numbers indicate percentage of Mash1+ cells in these cultures. Scale bar=50μm.

Next, to determine which endothelial Notch ligands are responsible, we performed loss-of-function studies. As Jagged1 and Delta-like protein 4 (Dll4) are the most highly expressed Notch ligands in endothelial cells33, we knocked them down individually in bEND using siRNA prior to co-culture with NPCs and measured Notch activity and targets. Whereas Dll4 knock-down had only a minor effect on Notch-dependent gene regulation (not shown), we found that Jag1 reduction significantly decreased Notch signalling (Fig. 4c, d; Supplementary Fig4c, d). Conversely, treatment of NPCs or aNSC with recombinant Jagged1 and ensuing Notch activation was sufficient to promote type-B fate (Fig.4e, f; Supplementary Fig. 1m and 4e). However, unlike ephrinB2, Jagged1 did not induce GFAP expression, indicating that the signalling mechanisms downstream of Eph and Notch are distinct. Consistent with this, Jagged1 knock-down in bEND had only a modest effect on the proliferation of cocultured NPCs and Jagged1 treatment induced a small decrease in S-phase of progenitors without affecting CyclinD levels (Fig.4e and Supplementary Fig. 1l, 4f and 5a). Thus, Jagged1 ligands on endothelial cells primarily regulate stem cell identity with a lesser role on proliferation independent of CyclinD.

Eph and Notch jointly inhibit differentiation

To test whether ephrinB2 and Jagged1 are sufficient to recapitulate the inhibition of differentiation elicited by endothelial cells, we seeded NPCs on either or both recombinant ligands and induced differentiation. Interestingly, we found that treatment with either ephrinB2 or Jagged1 alone altered NPC differentiation by decreasing neurogenesis and increasing oligodendrogenesis and astrogliogenesis, respectively, but was not sufficient to maintain type-B fate. In contrast, combined treatment with ephrinB2 and Jagged1 suppressed differentiation into all three lineages and maintained the cells as GFAP+Sox2+ type-B-like cells (Fig. 5a-b).

Figure 5. Jagged1 and ephrinB2 jointly inhibit neuronal differentiation.

(a) Representative immunofluorescence images of neural stem cells seeded on Fc controls, ephrinB2-Fc, Jagged1-Fc or both ligands as stated, differentiated for 4d and stained for the indicated markers and counterstained with DAPI. (b) Quantification of cultures shown in (a). Shown is the mean±s.e.m. of n = three independent experiments pooled from duplicate dishes. For each experiment a minimum of 200 cells across randomly selected fields of view was counted. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. Each dot represents an independent experiment. Source data in Supplementary table 1. Scale bar=100μm.

Together, our results suggest that ephrinB2 and Jagged1 do not cross-talk to maintain stem cells. To test this, we examined cell-cycle profiles of NPCs treated with either ligand alone or in combination and found that combined treatment does not further suppress proliferation, compared to ephrinB2 alone (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Similarly, treatment of NPC-Efnb2−/− pEC co-cultures with DAPT did not rescue NPC cell-cycle arrest to a greater extent than Efnb2 deletion alone (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Finally, stimulation of NPCs with ephrinB2 and Jagged1 did not induce identity genes to a greater extent than individual ligands (Supplementary Fig. 5c). We conclude that vascular ephrinB2 and Jagged1 function through independent mechanisms to cooperatively maintain neural stem cells.

As ERK signalling plays important roles in neuronal differentiation, we asked whether P-ERK downregulation by ephrinB2 might have a direct effect on NPC differentiation. Western analysis revealed that differentiation is accompanied by a two-day increase in p-ERK levels starting at d2 after growth factor removal, which was suppressed by ephrinB2 (Supplementary Fig. 5d). This increase was independent of proliferation as the cultures became quiescent within 48h of mitogen removal (not shown). However, whereas U0126 treatment of the cultures at d3-4 disrupted NPC differentiation, ERK inhibition alone or in conjunction with Jagged1 stimulation, did not maintain type-B fate (Supplementary Fig. 5e). Instead, U0126 increased oligodendrogenesis at the expense of neurogenesis, similar to ephrinB2. Together with the absence of changes in gene expression in U0126-treated cells (Supplementary Fig. 3e), these results suggest that the ephrinB2-dependent ERK downregulation maintains stem cells largely by suppressing proliferation at the onset of differentiation and not through a direct effect on neurogenesis.

Endothelial ephrinB2 and Jagged1 maintain quiescent stem cells in vivo

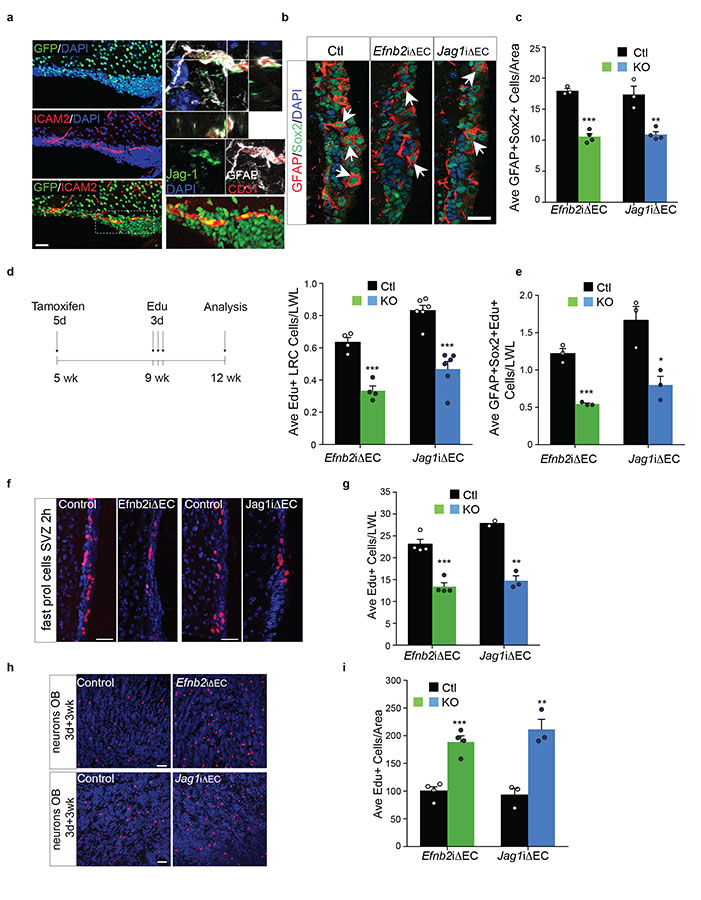

To test the role of endothelial ephrinB2 and Jagged1 on stem cell function in vivo, we first analysed expression of both ligands in the adult SVZ vascular niche. To detect ephrinB2, we assessed GFP levels in coronal sections of Efnb2-GFP reporter mice co-stained with the endothelial marker ICAM2 and found homogenous expression throughout the SVZ vasculature. Similarly, immunostaining of wild type SVZs for Jagged1, GFAP and the endothelial marker CD31 revealed endothelial expression of Jagged1 at sites of contact with GFAP+ type-B stem cells (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6. Vascular ephrinB2 and Jagged1 maintain neural stem cells in vivo.

Analysis of SVZ neurogenesis 4 weeks after recombination. (a) Immunofluorescence staining for GFP (green) and the endothelial marker ICAM2 (red) in coronal section of the SVZ of Efnb2-GFP reporter mice (left) and Jagged1, GFAP and CD31 staining of coronal sections of wild type SVZ (right). Inset (bottom right) shows a higher magnification of a representative GFP-positive SVZ vessel. Lateral views show colocalisation of GFAP+ type-B cell processes with Jagged1+ vessels. (b) Representative immunofluorescence images of SVZs of Efnb2iΔEC, Jag1iΔEC and control tamoxifen-injected littermates (Ctl) stained for GFAP and Sox2 at 4 weeks post-recombination. (c) Quantification of GFAP+Sox2+ type-B cells in all genotypes at the same timepoint as b (Ctl n=3 animals; Jag1iΔEC n=4). (d) Schematic representation of EdU labelling regime (left) and quantification of total EdU label retaining cells (LRC, right, Ctl Efnb2 and Efnb2iΔEC n=4; Ctl Jag1 and Jag1iΔEC n=6). (e) Quantification of EdU+GFAP+Sox2+ label retaining cells labelled with EdU as depicted in d and stained for GFAP, Sox2 and EdU at the end of the EdU chase period (7 weeks, n=3 all genotypes). (f) Representative EdU staining of actively proliferating cells in the SVZ of Efnb2iΔEC, Jag1iΔEC and respective control littermates at 4 weeks post-recombination. (g) Quantifications of EdU staining in (f). (Ctl Efnb2 n=4, Efnb2iΔEC n=4; Ctl Jag1 n=2 and Jag1iΔEC n=3). (h) Representative immunofluorescence images and quantifications (i) of EdU staining of label retaining cells in the olfactory bulbs of the indicates genotypes (Ctl Efnb2 and Efnb2iΔEC n=4; Ctl Jag1 and Jag1iΔEC n=3). Data are normalized to the length of the SVZ lateral wall (LWL) or to SVZ-olfactory bulb area analysed as indicated and expressed as mean±SEM. Each dot represents a mouse. p values were calculated using the two-tailed paired Student’s t-test. Source data in Supplementary table 1. Scale bars: a=100μm; b=20μm; f=30μm; h=30μm.

Next, we used an inducible loss-of-function genetic approach to delete Efnb2 and Jag1 selectively in the adult endothelium. We generated Efnb2iΔEC and Jag1iΔEC by crossing Enfb2flox/flox and Jag1flox/flox animals to Cdh5-CreERT2 mice and induced recombination postnatally using tamoxifen. Vascular specificity and recombination efficiency of Efnb2 and Jag1 deletion in the SVZ was confirmed in Cdh5-CreERT2;ROSA26-YFP reporter mice (Supplementary Fig. 6a) and by immunostaining for ephrinB2, Jagged1 and NICD34-36 (Supplementary Fig.6b-d).

Four weeks after recombination, we used GFAP+Sox2+ co-immunostaining and EdU-label retention to independently assess effects on quiescent type-B cells. Mice were injected for 3 consecutive days with EdU and analysis of label retaining cells (LRC) performed 3 weeks later (Fig. 6d). To confirm that EdU LRC counted in d corresponded to type-B cells, we also co-stained EdU+ cell for GFAP and Sox2 at the end of the chase period (7 weeks). All methods revealed a significant decrease in type-B numbers in the SVZs of Efnb2iΔEC and Jag1iΔEC mice compared to controls (Fig. 6b-e). This was not due to an increase in cell death or premature differentiation into mature astrocytes in the knock-outs, as there was no change in active caspase-3+ or S100β+ or GFAP+ cells (not shown and Supplementary Fig. 6e).

To analyse actively proliferating type-C and type-A cells progenitors, we pulsed the animals at 4 weeks post-recombination with EdU for 2h37. Consistent with the observed reduction in type-B cells, we found a significant decrease in EdU+ cells in the SVZs and an increase in the RMS of Efnb2iΔEC and Jag1iΔEC mice (Fig. 6f, g and not shown), indicating progenitor depletion and rapid exit from the SVZ.

In addition to slowly-dividing stem cells, label-retaining protocols label newborn neurons that migrate to the olfactory bulb during the chase period37,38. Therefore, to examine effects of ligand deletion on neurogenesis, we counted EdU+ cells in the olfactory bulb (which were NeuN+ interneurons, Supplementary Fig. 6g-h) and found a significant increase in both mutants relative to controls (Fig. 6h, i). Importantly, this increase was not due to a direct effect on neuronal survival, because apoptosis levels did not change in the olfactory bulb (Supplementary Fig. 6f).

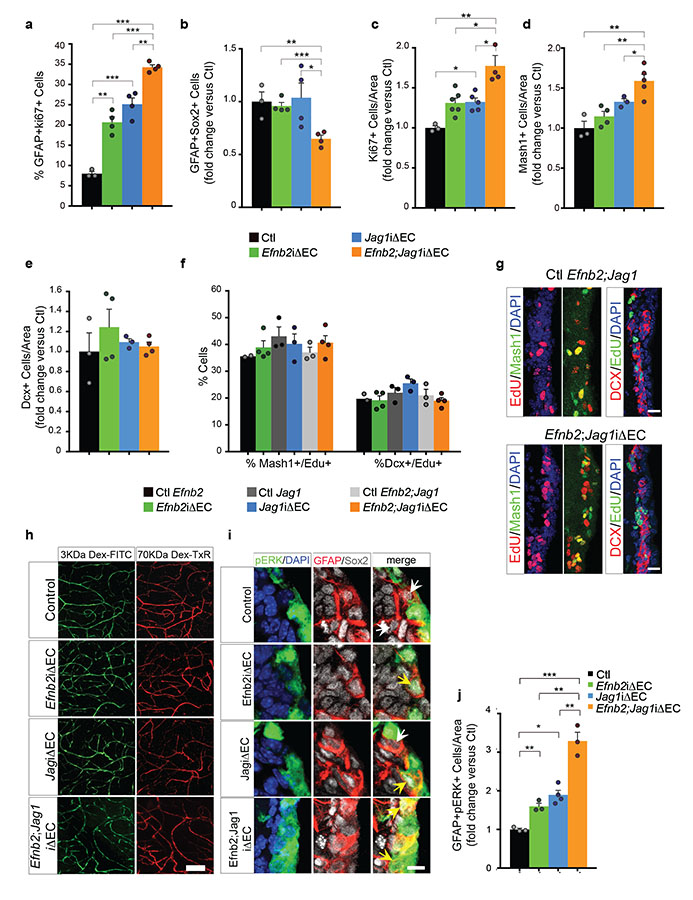

These findings suggest that upon deletion of vascular ephrinB2 and Jagged1, quiescent type-B stem cells become activated prematurely, resulting in an early increase in neuron production, followed by rapid depletion of the quiescent stem cell population and their immediate progeny. To test this directly, we examined type-B cell proliferation shortly after recombination (10d) by quantifying the percentage of activated type-B cells (Ki67+GFAP+), total numbers of type-B cells (GFAP+Sox2+) and total proliferating cells (Ki67+). In both models, we found a significant increase in activated type-B cells with no change in total type-B numbers upon ligand deletion, which was accompanied by a milder increase in the number of actively proliferating cells (Fig. 7a-c).

Figure 7. Loss of ephrinB2 and Jagged1 prematurely activates quiescent type-B stem cells in the SVZ.

Analysis of SVZ neurogenesis 10d after recombination. (a) Quantification of the percentage of activated GFAP+Ki67+ type-B cells in the SVZ of mice of indicated genotypes (Ctl n=3 animals and n=4 for all mutants). For this and all following graphs, only one representative control is depicted for clarity as all controls gave similar results. (b) Quantification of total GFAP+Sox2+ type-B cells. Values are expressed as fold change relative to respective tamoxifen-injected littermate controls (Ctl) to facilitate comparison across genotypes (Ctl n=3 and n=4 for all mutants). (c) Quantification of total Ki67+ cells normalised to controls (Ctl n=3, Efnb2iΔEC n=6, Jag1iΔEC n=5, Efnb2;Jag1iΔEC n=4). (d) Quantificaiton of total Mash1+ type-C cells. Values are expressed as fold change to controls (Ctl n=3; Efnb2iΔEC n=4, Jag1iΔEC n=3, Efnb2;Jag1iΔEC n=4). (e) Quantification of total DCX+ type-A cells. Values are expressed as fold change to controls (Ctl n=3; Efnb2iΔEC n=4, Jag1iΔEC n=3, Efnb2;Jag1iΔEC n=4). (f) Quantification of the percentage of EdU+ type-C (Mash1+) and type-A (DCX+) cells over total number of Mash1+ and DCX+ cells respectively, in the SVZs of all control and mutant mice (Ctl Efnb2 n=2, Efnb2iΔEC n=4, Ctl Jag1 n=3, Jag1iΔEC n=3, Ctl Efnb2;Jag1 n=3, Efnb2;Jag1iΔEC n=4). (g) Representative images of Mash1, DCX and EdU staining in Efnb2;Jag1iΔEC and Ctl SVZ. (h) Representative images of wholemount preparations of SVZs perfused intracardially with fixable fluorescent Dextrants of the indicated sizes. (i) Representative immunofluorescence images of SVZs of indicated genotypes stained for GFAP, Sox2 and pERK, white arrows indicate pERK negative and yellow arrows pERK positive type-B cells. (j) Quantification of staining in (e). Values are normalised to area and expressed as fold change over respective controls (Ctl n=3, Efnb2iΔEC n=3, Jag1iΔEC n=4, Efnb2;Jag1iΔEC n=3). All bars represent mean ±s.e.m. Each dot represents a mouse. For all quantifications shown p values were calculated using the two-tailed paired Student’s t-test. Source data in Supplementary table 1. Scale bars: g=25μm; h=75μm; i=15μm.

Importantly, the total number of Mash1+ type-C cells and DCX+ type-A cells and their proliferative activity (calculated as percentage of Mash1+EdU+ or DCX+EdU+ cells over total Mash1+ and DCX+ cells, respectively) did not change significantly (Fig. 7d-f), confirming that deletion of Efnb2 or Jag1 in the vasculature selectively affects type-B stem cells within the SVZ niche.

To rule out the possibility that activation is secondary to defects in tissue perfusion or blood brain barrier integrity caused by vascular ephrinB2 and Jagged1 deletion, we performed perfusion experiments with fluorescent dextrans followed by whole-mount imaging of the SVZ vascular plexus. As shown in Fig. 7h, vascular function remained intact in Efnb2iΔEC and Jag1iΔEC mice (and Efnb2;Jag1iΔEC double knock-out mice, see below), as evidenced by homogenous fluorescence and absence of leakage. These results confirm that type-B cell activation is specifically caused by loss of cell-cell contact dependent signalling with endothelial cells.

We next assessed whether ERK signalling contributes to type-B cell proliferation in vivo by co-staining the SVZs of control, Efnb2iΔEC and Jag1iΔEC mice for p-ERK, GFAP and Sox2 and counting numbers of p-ERK+ type-B cells. Consistent with the increase in activated type-B cells in both mutants, we found a significant increase in the numbers of p-ERK+ type-B cells, which were comparable to the numbers of activated cells (Fig. 7i, j). These observations suggest that activation of type-B cells to a proliferative state in vivo is accompanied by p-ERK derepression and that this process is aberrantly enhanced in Efnb2iΔEC and Jag1iΔEC mice.

Thus, vascular ephrinB2 and Jagged1 both negatively regulate the transition of quiescent type-B stem cells to the activated state. To investigate how these pathways interact in vivo to maintain stem cells, we generated Efnb2;Jag1iΔEC compound mice, and examined effects of ligands deletion on type-B cells 10d post-recombination. Remarkably, we found a greater increase in the percentage of activated type-B cells and p-ERK+ type-B cells in the double endothelial-specific knock-outs compared to single knock-out mice, which was accompanied by a 0.35 fold decrease in the total number of type-B cells (in the absence of apoptosis, not shown), indicative of early depletion (Fig. 7a, b, j). Consistent with a more severe phenotype, we also found a greater increase in the number of Ki67+ proliferating cells in Efnb2;Jag1iΔEC, accompanied by an increase in the overall number of type-C cells (with no change in type-A cells, Fig. 7c-e). Importantly, as in the single knock-out mice, the proliferative capacity of type-C or type-A cells remained unaffected, confirming the specificity of the effects on type-B cells (Fig. 7f). We conclude that vascular ephrinB2 and Jagged1 function independently to jointly maintain type-B cells.

Discussion

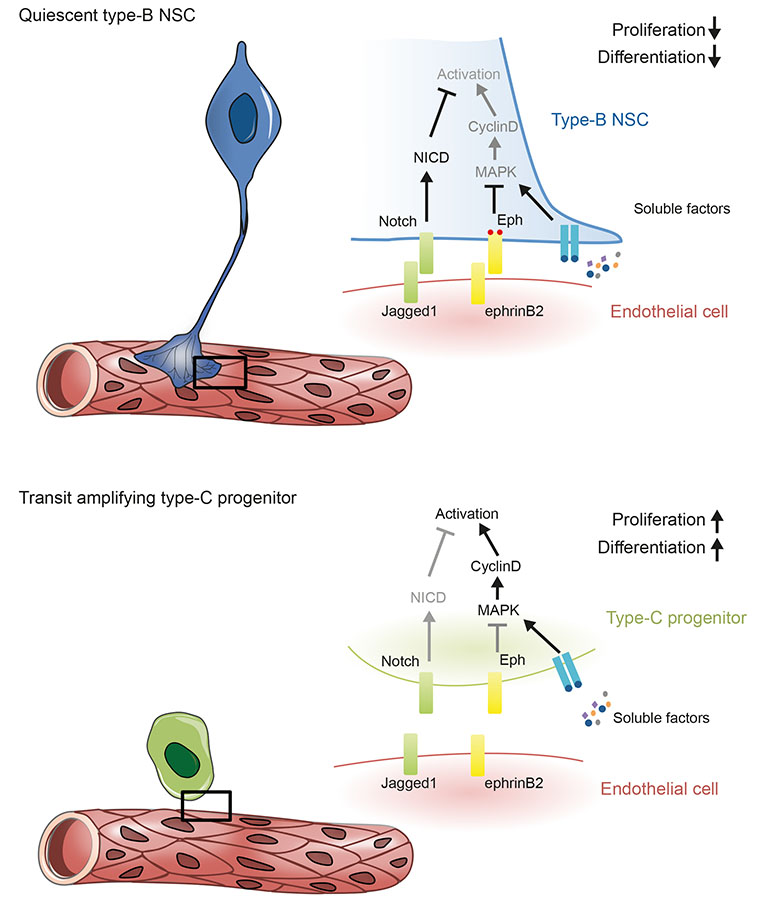

The niche, by definition, both maintains stem cells in a quiescent and undifferentiated state to prevent depletion, and directs their differentiation along the appropriate lineages1,3,39. However, how a shared microenvironment produces such opposite biological outcomes on its resident stem cell subpopulations remains unclear. This fundamental question is particularly relevant to the SVZ, where most progenitor subtypes associate with the vascular niche5,8,9, but whereas activated type-B and type-C progenitors respond to vascular-secreted factors by proliferating and differentiating, type-B stem cells remain quiescent and undifferentiated. We showed that stable direct cell-cell interactions between quiescent type-B cells and endothelial cells underlie this differential response, in that physical contact renders stem cells refractory to extrinsic proliferative and differentiative cues to maintain quiescence and identity. We found endothelial ephrinB2 and Jagged1 to be largely responsible for these effects, with ephrinB2 mainly suppressing MAPK signalling to enforce quiescence and Jagged1 predominantly controlling identity. These results are consistent with the previously reported roles for Eph and Notch in the SVZ and identify the vasculature as a critical regulator of these pathways within this niche18,19,21,34-36.

Though it is clear that ephrinB2 is a key player in the enforcement of quiescence by the vasculature, genetic deletion of Efnb2 in endothelial cells, reversed the cell-cycle arrest of cocultured precursors incompletely, indicating that additional mechanisms are likely to be involved. Intriguingly, previous reports have identified endothelial-secreted BMPs as negative regulators of neural stem cell proliferation40,41. It will be of great interest to explore a potential crosstalk between Eph and Smad signalling in this context.

Interestingly, although ephrinB2 and Jagged1 had distinct functions in vitro, conditional deletion of either ligand in the adult vasculature in vivo resulted in a strikingly similar phenotype, which was enhanced in double knock-out mice and mirrors other mouse models with defects in stem cell maintenance19,36,37: increased conversion of quiescent type-B cells to the activated state, followed by rapid depletion of the stem cell pool. A likely explanation for this apparent discrepancy is that in vivo vascular loss of ephrinB2 activates type-B stem cells through a direct effect on proliferation, whereas Jagged1 deletion, does so indirectly, by promoting the acquisition of the activated type-B transcriptional profile, which was recently shown to be intrinsically proliferative42. Alternatively, Jagged1 might play a much greater role in restraining stem cell proliferation in vivo than it does in culture due to the greater complexity of the SVZ microenvironment.

Although a recent study identified EphB2 as a Notch target in ependymal cells21, we did not detect a similar direct crosstalk in our system, where ephrinB2 and Jagged1 appear to function independently both in vitro and in vivo. Together, our findings strongly suggest that SVZ stem cell maintenance depends on the combinatorial activation of separate pathways downstream of vascular ephrinB2, Jagged1 and other yet unknown cues, a stem cell regulation principle shared by many other niches43.

Together, our results point to the following model of stem cell regulation by the vascular niche (Fig.8). Anchorage to the vasculature exposes type-B stem cells to ephrinB2 and Jagged1 ligands, which restrain their proliferation and differentiation to maintain identity and prevent depletion. Upon activation and displacement from the niche, precursor cells lose stable vascular contact. This terminates Eph and Notch signalling, allowing the cells to respond to soluble cues and progress through the lineage.

Figure 8. Model of vascular niche-regulated neurogenesis in the adult SVZ.

(a) In the adult SVZ, quiescent type-B stem cells physically contact endothelial cells through specialized endfeet. This direct cell-cell interaction allows endothelial ephrinB2 and Jagged1 to respectively activate Eph and Notch signalling in type-B cells. Upon stimulation, Eph attenuates MAPK signalling induced by growth factors, thereby downregulating CyclinD levels to inhibit proliferation. In parallel, activation of Notch signalling by Jagged1 maintains quiescent type-B fate by modulating gene expression. (b) Type-C progenitors contact the endothelium more transiently and at smaller sites. This terminates Eph and Notch signalling, allowing the cells to activate MAPK in response to soluble cues and enter the cell-cycle to progress through the lineage.

Methods

Animals

All animal work was carried out in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the Home Office. For loss-of-function studies, Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 mice44 were crossed to animals carrying a loxP-flanked Efnb2 gene (Efnb2flox/flox) or Jag1 gene (Jag1flox/flox)45,46. To induce Cre activity in adult mice, 5 consecutive intraperitoneal tamoxifen injections (100mg/Kg) were given to 3 or 5 week old mice, yielding 50-60% recombination efficiency, as assessed by crossing Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 mice to a ROSA26eYFP reporter strain (Supplementary Figure 6a). Tamoxifen-injected Efnb2flox/flox littermates were used as control. Mice were analysed 7 days and 4 weeks after the final tamoxifen injection.

Cell Culture and treatment

The SVZ was dissected from P6-P10 mouse brains as described previously47. Briefly, following isolation, the SVZ was dissociated in HBSS medium (Invitrogen) containing 0.05% trypsin (Invitrogen) and 60U/ml Dnase I (Sigma), washed and plated on poly-l-lysine (PLL)-coated plates in SVZ explant medium [DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen), 3%FBS, 20ng/ml EGF (Peprotech)]. The next day NPCs were purified by fractionation and the medium was replaced with SVZ culture medium [DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen), 0.25% FBS (invitrogen), N2 (Invitrogen), 20ng/ml EGF (Peprotech), 10ng/ml bFGF (Peprotech) and 35ug/ml bovine pituitary extract] modified from Scheffler et al.48. NPCs were cultured in adhesion under the same conditions for up to 8-10 passages. Adult neural stem cells were isolated from 2-3 month old mice and cultured as neurospheres or in adhesion as previously described49-50. SVZs from postnatal Rbpjflox/flox floxed mice were isolated and NPCs were infected with either adeno-GFP or Adeno-Cre viruses at an MOI of 100. The efficiency of the recombination was assessed by qPCR (Figure 4d).

The bEnd.3.1 mouse brain endothelial cell line and primary mouse brain microvascular endothelial cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and Caltag Medsystems, respectively, and subcultured according to the suppliers’ recommendations. Conditionally immortalised WT and EfnbB2 knock-out pulmonary endothelial cells (pEC) were derived and cultured as previously described44.

For all co-culture experiments, endothelial cells were seeded at 4×104 per cm2 on PLL-laminin in endothelial medium. The following day, endothelial cells monolayers were washed in serum-free media and NPCs were seeded at the same density directly onto the endothelial cell monolayers in SVZ culture medium. For analyses of NPCs phenotypes on bEND and bmvEC, NPCs were separated from endothelial monolayers prior to analysis by differential trypsinization, as follows. A thin layer of trypsin was added to the co-cultures for 1-2 minutes to specifically detach NPCs, leaving the endothelial cell monolayer intact. This method yielded negligible endothelial cell contamination as judged by the absence of endothelial markers in purified NPCs when measured by qPCR analysis. For co-culture experiments with pEC, NPCs isolated from Td-Tomato mice or cell-tracker labelled wild type NPCs were isolated from endothelial cells by FACS prior to analysis. For the experiments performed at low density, endothelial cells and NPCs were both seeded at 1.5×104 per cm2 on PLL coated plates. In order to assess the contribution of endothelial cell-secreted soluble factors, NPCs were plated on the bottom well of a transwell insert (0.4 μm pore-size, BD Falcon) onto which endothelial cells were seeded, at a density 1 × 104cells per cm2.

To inhibit Notch signalling in vitro, the cultures were treated with 10 μM DAPT or DMSO as control for 24 h. For p-ERK inhibition, the MEK inhibitor UO126 was used at 5-10 μM. For detection of apoptosis, NPCs were treated with Bleomycin at 0.06U/ml as a positive control. For ephinB2 and Jagged1 stimulation, clustered ephrinB2-Fc and/or Jagged1-Fc fusions at a final concentration of 8 μg/ml and 4 μg/ml were absorbed on PLL-coated tissue culture plated plates (R&D systems). Clustering was achieved using anti-human Fc antibodies (Jackson Laboratory) at a 2:1 molar ratio and clustering quantifications were performed as reported51. To inhibit homotypic cell-cell interactions, NPCs were infected with adenoviral vectors encoding a truncated form of N-cadherin that acts as a dominant-negative without affecting endogenous N-cadherin level or control virus52. To induce differentiation, the cells were seeded on PLL-laminin glass coverslips in SVZ culture medium. After 24hrs, the cells were induced to differentiate by removing growth factors and serum from the SVZ culture medium. Cultures were analysed 4 days later and the number of neuroblasts, oligodendrocytes and astrocytes was determined by scoring 200 cells across randomly selected fields in duplicate coverslips.

Transfections and Luciferase assays

NPC were transfected with Nucleofector kit (Amaxa) according to manufacturer’s instructions before plating as above. 24 hrs post-nucleofection, culture medium was either replaced or switched to differentiation media [DMEM/F12, N2, B27 (Invitrogen)] and luciferase activity measured 48 hrs later. Luciferase levels were normalized to total cell number. The pHes5p-luc construct was obtained from Addgene (plasmid 26869)53.

siRNA, qPCR, Western Blotting and Immunofluorescence

RNA silencing, quantitative reverse transcription-PCR, western blotting and immunostainings were performed as previously described51. Target sequences for Jag1 were: CTGGTTGAATCTCATTACAAA and CCGGATGGAATACATCGTATA. Oligos were used at a final concentraiion of 50-80nM. All western blots shown were performed on three lysates from independent experiments with similar results.

Flow cytometry and immunocytochemistry

BrdU (10 μM) was added to the medium 1 hour before harvesting cells. Ethanol-fixed samples were stained with anti-BrdU (Roche) and propidium iodide (Sigma) and analysed using FlowJo software (Becton Dickinson). ≥10,000 events were collected for each sample and gates set manually using negative controls. For EGFR staining, NPCs were fixed with PFA 4% and stained with mouse antibodies to EGFR. Hes5-GFP NPCs were fixed and stained with mouse anti-Nestin (Abcam) and rabbit anti-GFP 488 (Invitrogen) antibodies prior to FACS analysis. All FACS stainings were performed on 2 independent cultures from separate experiments with the exception of experiments in Fig. 1e, which were repeated 3 times. Immunocytochemistry was performed as described previously51. All representative stainings shown were repeated a minimum of 3 times on independent dishes with similar results.

EdU labelling Immunohistochemistry and Quantifications

To label actively proliferating cells, EdU (Invitrogen) was injected intraperitoneally (50mg/kg) 2h prior to analysis. For label retaining cells, mice were given daily EdU injections for 3 days and sacrificed 3 weeks later. The whole extent of the SVZ was cut in coronal sections (50 μm) and the sections were stained using the Click-iT kit (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Sections were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min and then incubated in blocking solution containing 10% normal donkey serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 hr at RT. Primary antibodies were added in blocking solution at 4°C overnight. Subsequently, sections were washed in PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies (Alexa) in PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 for about 1 hr at RT, washed in PBS and mounted in vectashield (Vector) mounting medium. For Ki67 staining, antigen retrieval was performed in target retrieval solution (DAKO) for 20 minutes at 120 °C in a pressure cooker (EMS) before permeabilisation. For ephrinB2 detection in the SVZ vasculature, we either used Efnb2-GFP reporter mice and performed GFP staining as reported or ephrinB2 antibody (a kind gift of Makinen)44,54. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit antibodies to Sox2 (Abcam ab97959, 1:400), pEph (Abcam ab61791, 1:500), p-ERK (Cell Signalling 4370, 1:100), Ki67 (Novocastra 201701, 1:500), GFAP (DAKO Z0334, 1:1000), Active Caspase-3 (Cell Signalling 9664, 1:500), Jagged1 (Cell Signalling 2620, 1:500), GFP (Invitrogen 11814460001, 1:200) and NICD (Abcam ab8925, 1:100; Cell Signalling 4147, 1:100), mouse antibodies to Tuj1 (Covance MMS-435P, 1:500), N-cadherin (BD biosciences 610921, 1:200), nestin (Abcam ab6142, 1:100) and O4 (R&D MAB1326, 1:200), Sox2 (Abcam ab79351, 1:200), goat antibodies to Jagged1 (Santa Cruz sc-6011, 1:100) and GFAP (Abcam ab53554, 1:500) and rat antibodies to ICAM2 (BD biosciences 553325, 1:200), Mash1 (R&D MAB2567, 1:100), VE-cadherin or CD31 (BD biosciences 550274, 1:100). Biotinylated fixable dextrans experiments were performed as described8, with the following modifications. Briefly, mice were anesthesized and perfused intracardially with 9 ml of oxygenated 0.9% NaCl solution containing 200ug/ml of sodium fluorescein and texas red dextran conjugates (molecular mass 3kDa and 70kDa, Invitrogen) and wholemounts were dissected55.

For all quantifications, the following criteria were used: from each animal 15-20 slices throughout the SVZ were randomly selected (corresponding to approx. 1 every 3 sections) and the number of marker positive cells situated within 50–60 μm from the lateral wall of the ventricle was counted and normalized either to the area or to the length of the ventricular wall. For olfactory bulb quantifications, the entire olfactory bulb was sectioned coronally (50 μm) and 8-10 slices from each animal were randomly selected and analysed. The number of positive cells was normalized to the area of the olfactory bulb examined. All representative in vivo stainings for which quantifications are shown were performed on the same number of animals as the quantifications. Source data in Supplementary table 1. Animal numbers for the remaining immunofluorescence stainings were as follows: Fig. 6a n=3; Fig. 7h Ctl n=3, Efnb2iΔEC and Jag1iΔEC n=3 Efnb2;Jag1iΔEC n=2; Fig. S6a n=3; Fig. S6b n=4; Fig.S6c n=3; Fig. S6d n=3; Fig. S6e n=2).

Statistics

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Significance was calculated with the 2-tailed Student’s t test and ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test using SPSS software. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. Sample size was determined based on existing literature and our previous experience. The experiments were not randomized. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments but quantifications were performed blind, i.e. the investigators were blinded during outcome assessment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Medical Research Council, UK (C.O., B. K., M. C. and S. P.) and the Royal Society (S. P.). We thank A. Fisher, M. Raff, L. Aragon and M. Ungless for critical reading of the manuscript, S. Nicolis, Univerity of Milano-Bicocca, Italy, M. Herlyn, The Wistar Institute, USA and J. Gil, MRC Clinical Sciences Centre, UK for constructs, S. Di Giovanni, Imperial College London, UK and V. Taylor, University of Basel, Switzerland for Hes5-GFP neural stem cells, S. Pollard, MRC Centre for Regenerative Medicine, UK for cells, T. Makinen, Universitu of Uppsala, Sweden for ephrinB2 antibody and J. Lopez Tremoleda for technical advice.

References

- 1.Fuchs E, Tumbar T, Guasch G. Socializing with the neighbors: stem cells and their niche. Cell. 2004;116:769–778. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen S, Wang S, Xie T. Restricting self-renewal signals within the stem cell niche: multiple levels of control. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2011;21:684–689. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.07.008. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagers AJ. The stem cell niche in regenerative medicine. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:362–369. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.018. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doetsch F, Caille I, Lim DA, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Subventricular zone astrocytes are neural stem cells in the adult mammalian brain. Cell. 1999;97:703–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80783-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ihrie RA, Alvarez-Buylla A. Lake-front property: a unique germinal niche by the lateral ventricles of the adult brain. Neuron. 2011;70:674–686. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.004. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Verdugo JM, Doetsch F, Wichterle H, Lim DA, Alvarez-Buylla A. Architecture and cell types of the adult subventricular zone: in search of the stem cells. J Neurobiol. 1998;36:234–248. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199808)36:2<234::aid-neu10>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirzadeh Z, Merkle FT, Soriano-Navarro M, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Neural stem cells confer unique pinwheel architecture to the ventricular surface in neurogenic regions of the adult brain. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.004. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tavazoie M, et al. A specialized vascular niche for adult neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.025. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen Q, et al. Adult SVZ stem cells lie in a vascular niche: a quantitative analysis of niche cell-cell interactions. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.026. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen Q, et al. Endothelial cells stimulate self-renewal and expand neurogenesis of neural stem cells. Science. 2004;304:1338–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.1095505. doi:10.1126/science.1095505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kokovay E, et al. Adult SVZ lineage cells home to and leave the vascular niche via differential responses to SDF1/CXCR4 signalling. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.05.019. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calvo CF, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 directly regulates murine neurogenesis. Genes & development. 2011;25:831–844. doi: 10.1101/gad.615311. doi:10.1101/gad.615311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quaegebeur A, Lange C, Carmeliet P. The neurovascular link in health and disease: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Neuron. 2011;71:406–424. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.013. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg JS, Hirschi KK. Diverse roles of the vasculature within the neural stem cell niche. Regen Med. 2009;4:879–897. doi: 10.2217/rme.09.61. doi:10.2217/rme.09.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen S, Lewallen M, Xie T. Adhesion in the stem cell niche: biological roles and regulation. Development. 2013;140:255–265. doi: 10.1242/dev.083139. doi:10.1242/dev.083139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pasquale EB. Eph-ephrin bidirectional signalling in physiology and disease. Cell. 2008;133:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.011. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pierfelice T, Alberi L, Gaiano N. Notch in the vertebrate nervous system: an old dog with new tricks. Neuron. 2011;69:840–855. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.031. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conover JC, et al. Disruption of Eph/ephrin signalling affects migration and proliferation in the adult subventricular zone. Nature neuroscience. 2000;3:1091–1097. doi: 10.1038/80606. doi:10.1038/80606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imayoshi I, Sakamoto M, Yamaguchi M, Mori K, Kageyama R. Essential roles of Notch signalling in maintenance of neural stem cells in developing and adult brains. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:3489–3498. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4987-09.2010. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4987-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ehm O, et al. RBPJkappa-dependent signalling is essential for long-term maintenance of neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:13794–13807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1567-10.2010. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1567-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nomura T, Goritz C, Catchpole T, Henkemeyer M, Frisen J. EphB signalling controls lineage plasticity of adult neural stem cell niche cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:730–743. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.009. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Theveneau E, Mayor R. Collective cell migration of epithelial and mesenchymal cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1251-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pastrana E, Cheng LC, Doetsch F. Simultaneous prospective purification of adult subventricular zone neural stem cells and their progeny. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:6387–6392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810407106. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810407106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wurmser AE, et al. Cell fusion-independent differentiation of neural stem cells to the endothelial lineage. Nature. 2004;430:350–356. doi: 10.1038/nature02604. doi:10.1038/nature02604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hack MA, et al. Neuronal fate determinants of adult olfactory bulb neurogenesis. Nature neuroscience. 2005;8:865–872. doi: 10.1038/nn1479. doi:10.1038/nn1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menn B, et al. Origin of oligodendrocytes in the subventricular zone of the adult brain. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2006;26:7907–7918. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1299-06.2006. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1299-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshioka N, Asou H, Hisanaga S, Kawano H. The astrocytic lineage marker calmodulin-regulated spectrin-associated protein 1 (Camsap1): phenotypic heterogeneity of newly born Camsap1-expressing cells in injured mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2012;520:1301–1317. doi: 10.1002/cne.22788. doi:10.1002/cne.22788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sherr CJ. D-type cyclins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:187–190. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miao H, et al. Activation of EphA receptor tyrosine kinase inhibits the Ras/MAPK pathway. Nature cell biology. 2001;3:527–530. doi: 10.1038/35074604. doi:10.1038/35074604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parrinello S, et al. EphB signalling directs peripheral nerve regeneration through Sox2-dependent Schwann cell sorting. Cell. 2010;143:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.039. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gale NW, et al. Ephrin-B2 selectively marks arterial vessels and neovascularization sites in the adult, with expression in both endothelial and smooth-muscle cells. Developmental biology. 2001;230:151–160. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0112. doi:10.1006/dbio.2000.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koch U, Lehal R, Radtke F. Stem cells living with a Notch. Development. 2013;140:689–704. doi: 10.1242/dev.080614. doi:10.1242/dev.080614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu TS, et al. Endothelial cells create a stem cell niche in glioblastoma by providing NOTCH ligands that nurture self-renewal of cancer stem-like cells. Cancer research. 2011;71:6061–6072. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4269. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andreu-Agullo C, Morante-Redolat JM, Delgado AC, Farinas I. Vascular niche factor PEDF modulates Notch-dependent stemness in the adult subependymal zone. Nature neuroscience. 2009;12:1514–1523. doi: 10.1038/nn.2437. doi:10.1038/nn.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mizutani K, Yoon K, Dang L, Tokunaga A, Gaiano N. Differential Notch signalling distinguishes neural stem cells from intermediate progenitors. Nature. 2007;449:351–355. doi: 10.1038/nature06090. doi:10.1038/nature06090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawaguchi D, Furutachi S, Kawai H, Hozumi K, Gotoh Y. Dll1 maintains quiescence of adult neural stem cells and segregates asymmetrically during mitosis. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1880. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2895. doi:10.1038/ncomms2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kokovay E, et al. VCAM1 is essential to maintain the structure of the SVZ niche and acts as an environmental sensor to regulate SVZ lineage progression. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.06.016. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doetsch F, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Cellular composition and three-dimensional organization of the subventricular germinal zone in the adult mammalian brain. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1997;17:5046–5061. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05046.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller FD, Gauthier-Fisher A. Home at last: neural stem cell niches defined. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:507–510. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.008. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mathieu C, et al. Endothelial cell-derived bone morphogenetic proteins control proliferation of neural stem/progenitor cells. Molecular and cellular neurosciences. 2008;38:569–577. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.05.005. doi:10.1016/j.mcn.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun Y, Hu J, Zhou L, Pollard SM, Smith A. Interplay between FGF2 and BMP controls the self-renewal, dormancy and differentiation of rat neural stem cells. Journal of cell science. 2011;124:1867–1877. doi: 10.1242/jcs.085506. doi:10.1242/jcs.085506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Codega P, et al. Prospective identification and purification of quiescent adult neural stem cells from their in vivo niche. Neuron. 2014;82:545–559. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.039. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crosnier C, Stamataki D, Lewis J. Organizing cell renewal in the intestine: stem cells, signals and combinatorial control. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:349–359. doi: 10.1038/nrg1840. doi:10.1038/nrg1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y, et al. Ephrin-B2 controls VEGF-induced angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nature. 2010;465:483–486. doi: 10.1038/nature09002. doi:10.1038/nature09002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brooker R, Hozumi K, Lewis J. Notch ligands with contrasting functions: Jagged1 and Delta1 in the mouse inner ear. Development. 2006;133:1277–1286. doi: 10.1242/dev.02284. doi:10.1242/dev.02284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grunwald IC, et al. Hippocampal plasticity requires postsynaptic ephrinBs. Nature neuroscience. 2004;7:33–40. doi: 10.1038/nn1164. doi:10.1038/nn1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lim DA, Alvarez-Buylla A. Interaction between astrocytes and adult subventricular zone precursors stimulates neurogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:7526–7531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scheffler B, et al. Phenotypic and functional characterization of adult brain neuropoiesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:9353–9358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503965102. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503965102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pollard S, et al. Adherent Neural Stem (NS) Cells from Fetal and Adult Forebrain. Cerebral Cortex. 2006;16(suppl 1):i112–i120. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj167. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferron SR, et al. A combined ex/in vivo assay to detect effects of exogenously added factors in neural stem cells. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:849–859. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parrinello S, et al. EphB signalling directs peripheral nerve regeneration through Sox2-dependent Schwann cell sorting. Cell. 2010;143:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.039. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kintner C. Regulation of embryonic cell adhesion by the cadherin cytoplasmic domain. Cell. 1992;69:225–236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90404-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mizutani K, Yoon K, Dang L, Tokunaga A, Gaiano N. Differential Notch signalling distinguishes neural stem cells from intermediate progenitors. Nature. 2007;449:351–355. doi: 10.1038/nature06090. doi:10.1038/nature06090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davy A, Soriano P. Ephrin-B2 forward signaling regulates somite patterning and neural crest cell development. Developmental biology. 2007;304:182–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.028. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mirzadeh Z, Doetsch F, Sawamoto K, Wichterle H, Alvarez-Buylla A. The subventricular zone en-face: wholemount staining and ependymal flow. J Vis Exp. 2010 doi: 10.3791/1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.