Abstract

Background

Brassica napus (AACC) is self-compatible, although its ancestor species Brassica rapa (AA) and Brassica oleracea (CC) are self-incompatible. Most B.napus accessions have dominant self-compatibility (SC) resulting from an insertion of 3.6 kb in the promoter region of BnSCR-1 on the A genome, while recessive SC in B.napus has rarely been observed. Expression and cloning of SRK and SCR genes and genetic analysis were carried out to dissect bases of recessive SC in B.napus.

Results

Eleven accessions were screened to identify stable recessive SC and had the S genotype BnS-7 on the A genome and BnS-6 on the C genome similarly to BrS-29 and BoS-15, respectively. In eight SC accessions, BnSCR-7 and BnSCR-6 were nearly undetectable and harbored no structural mutations in the promoters, while SRK genes were expressed at normal levels and contained intact CDS, with the exception of BnSRK-7 in line C32. SRK and SCR genes were expressed normally but their CDSs had no mutations in three SC accessions. In self-incompatible S-1300 and 11 F1 hybrids, SRK genes and BnSCR-1300 transcripts were present at high levels, while expression of the BnSCR-7 and BnSCR-6 were absent. Plants of S genotype S1300S1300 were completely SI, while SI phenotypes of SBnS-7SBnS-7 and S1300SBnS-7 plants were segregated in BC1 and F2 populations.

Conclusions

The recessive SC in eight accessions is caused by the loss of function of BnSCR-7 and BnSCR-6 in pollen. Translational repression contributes to the recessive SC in three accessions, whose SRK and SCR genes were expressed normally and had identical CDSs to BrS-29 or BoS-15. SI in 11 F1 hybrids relies on the expression of BnSCR-1300 rather than SRK genes. Other factor(s) independent of the S locus are involved in recessive SC. Therefore, diverse causes underlie recessive SC in B. napus, yielding insight into these complex mechanisms.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/1471-2164-15-1037) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Brassica napus, Self-incompatibility (SI), S locus genes, Gene expression, Genetic analysis

Background

Brassica napus (AACC) is an amphidiploid species developed from B. rapa (AA) and B. oleracea (CC). B. rapa and B. oleracea are self-incompatible, but B. napus is self-compatible. Elucidating how self-incompatibility (SI) was lost and self-compatibility (SC) was acquired has profound consequences for understanding the origin of B. napus as well as trait changes during the evolutionary process of plant polyploidization.

Self-incompatibility in Brassica is controlled sporophytically by a single multi-allelic locus called S locus (i.e., pollen SI phenotype is determined by the diploid genotype of the pollen-producing parent) [1]. The S locus consists of at least two genes: the stigma determinant S-locus receptor kinase gene (SRK) [2] and the pollen determinant S-locus protein 11 gene (SP11)/S-locus cysteine-rich protein (SCR) gene [3, 4] (SP11, referred to as SCR hereafter). The S locus is also termed the ‘S haplotype’ because S-locus genes are transmitted to progeny as one unit [5]. The SRK-SCR interaction is haplotype-specific and only occurs between the receptor and ligand encoded in the same S-locus haplotype [6–8]. S haplotypes can be divided into two classes. Class-II haplotypes are generally recessive to class-I haplotypes in pollen, but they are co-dominant in the stigma [9]. More than 100 and 50 S haplotypes occur in B. rapa and B. oleracea, respectively [10, 11]; only three and four haplotypes, respectively, are class II [12].

Self-incompatible B. napus strains have been developed via introgression from B. oleracea and B. rapa[13, 14] or via the resynthesis of B. napus from B. oleracea and B. rapa[15]. Thus, natural B. napus is usually thought to have lost S haplotypes, resulting in SC during evolution. However, latent S alleles are widespread in cultivated SC B. napus[16], and S haplotypes are widely distributed in cultivated B. napus lines [17, 18]. The most predominant S genotype is class-I S haplotype BnS-1 on the A genome (similar to B. rapa S-47 (BrS-47)) and class-II S haplotype BnS-6 on the C genome (similar to B. oleracea S-15 (BoS-15)). An insertion of 3.6 kb in the promoter region of BnSCR-1 previously resulted in no gene expression, but the non-functional class-I SCR on the A genome suppressed the expression of the recessive BnSCR-6 on the C genome, resulting in SC [17, 19]. However, SC in B. napus with two class-II S haplotypes has rarely been observed.

The B. napus self-incompatible line S-1300 contains two class-II S haplotypes, BnS-1300 on the A genome (similar to BrS-60) and BnS-6 on the C genome [18, 20]. In S-1300, SI is recessive in most accessions but dominant in some genetic backgrounds [21]; SI is determined by BnS-1300[22]. The suppression of BnSCR-1300 by the non-functional BnS-1 in most lines with dominant SC explains their dominant SC. Accessions with recessive SC usually have only two class-II S haplotypes, one on the A genome (similar to BrS-29) and the other on the C genome (similar to BoS-15) [23]. Furthermore, one recessive gene previously co-segregated with the S-locus SCR gene and was reported to control recessive SC in Bing409 [23], while at least two genes controlled the recessive SC of 97Wen135 [24]. It is puzzling that Bing409 and 97Wen135 are self-compatible but can maintain the SI of S-1300.

To uncover the basis of recessive SC in natural B. napus, 11 B. napus accessions were screened to identify stable recessive SC and had the S genotype BnS-7 on the A genome and BnS-6 on the C genome in this study. Genetic analysis, gene expression, and gene cloning suggest that diverse causes underlie recessive SC in B. napus.

Results

Screening B. napuswith recessive SC

Of the 30 F1 hybrids derived from crossing SI line S-1300 as a mother with 30 SC lines, 11 were stably SI, with an average SCI of <1 in both Wuhan and Lanzhou (Table 1). Thus, 11 male parents (B409, 1728, 614, 1745, C32, 1241, 326, 1638, 89008, 230, and 242) maintained the SI of S-1300 and displayed stable recessive SC.

Table 1.

Plants SI phenotype of 30 F 1 hybrids developed from S-1300 as the mother line

| Male parent | Wuhan, 2010.5 | Lanzhou, 2010.8 | SI stability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI | PSI | SC | SI | PSI | SC | ||

| 128-2 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| 131-2 | — | — | — | 0 | 2 | 7 | |

| 173-1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 2 | |

| 177-1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | — | — | — | |

| 182-1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| 230-1 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | + |

| 242-1 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | + |

| 326-2 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 2 | 0 | + |

| 336-1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | |

| 360-2 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | |

| 614-1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | + |

| 1100-1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1122-1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| 1241-1 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | + |

| 1242-1 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| 1621-1 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1638-1 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 | + |

| 1728-1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 0 | + |

| 1731-2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1745-1 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | + |

| 1756-1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | |

| 1760-2 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 2 | |

| 1771-1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 0 | |

| 89008 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | + |

| 68-1Chang | 1 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 0 | 0 | |

| B409 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 0 | + |

| C32 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | + |

| D29 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| ZY2045-2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | |

| Huashuang5 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 3 | |

SI: self-incompatible, SCI <2; PSI (partially SI): 2 ≤ SCI <10; SC: self-compatible, SCI ≥10; +: stable recessive SC accessions. SCI was calculated as the number of seeds per flower.

Shaplotypes in recessive SC B. napus

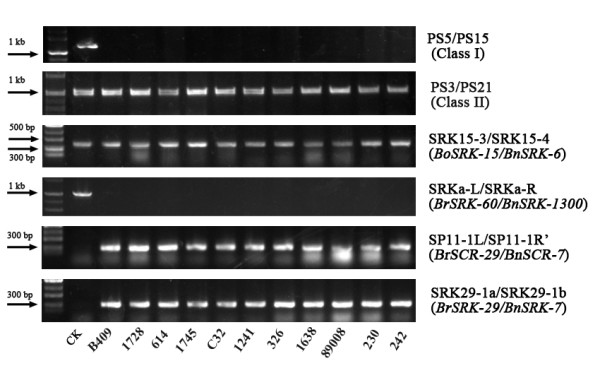

The S haplotypes of the 11 accessions were identified with the primer combinations in Table 2. There was no amplification by the class-I specific primer pair PS5/PS15, but amplification did result from class-II specific primers PS3/PS21 (Figure 1), indicating that the 11 accessions only had class-II S haplotypes.

Table 2.

Primers for S haplotype identification

| Primer | Nucleotide Sequence 5′ to 3′ | Length (bp) | S haplotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS3 | ATGAAAGGGGTACAGAACAT | 1000 | Class II | [25] |

| PS21 | CTCAAGTCCCACTGCTGCGG | |||

| PS5 | ATGAAAGGCGTAAGAAAAACCTA | 1340 | Class I | [25] |

| PS15 | ATGAAAGGCGTAAGAAAAACCTA | |||

| SRK15-3 | ATTCGATTGTGTTTCAGGCTC | 380 | BoSRK-15 | [22] |

| SRK15-4 | TCGACATGGTGATTTGGTTC | |||

| SRKa-L | CAAGTTCTAATGAACGAGGTGG | 1058 | BrSRK-60 | [20] |

| SRKa-R | CTGAGGAATAATAGGAGATACG | |||

| SP11a-L | CAGAAGTCATGAGATATGCTAC | 303 | BrSCR-29 | [23] |

| SP11a-R | ATTAGTAACATTCGGTCCG | |||

| SRK29-1a | TATCATTAAGAATTCATCCGACCT | 300 | BrSRK-29 | This study |

| SRK29-1b | TCATCGTCACGCCTAGAATAAG |

Figure 1.

S haplotype identification. Control (CK) is Westar in PS5/PS15 and S-1300 in the other five primer pairs.

Primer pairs SRK15-3/SRK15-4, SRKa-L/SRKa-R, and SP11a-L/SP11a-R were designed to amplify class-II S-locus genes BoSRK-15, BrSRK-60, and BrSCR-29, respectively. The 11 SC accessions and SI line S-1300 yielded a fragment with the same size (380-bp) which amplified by primer pair SRK15-3/SRK15-4 (Figure 1). This fragment was 100% identical to BnSRK-6 (AB270772.1), indicating that the 11 accessions carried BnS-6 (BoS-15) on the C genome.

Primer pair SRKa-L/SRKa-R produced a fragment of ~1000-bp only in S-1300, while SP11a-L/SP11a-R amplified a 303-bp DNA fragment in each of the 11 accessions (Figure 1). The 303-bp fragment was 100% identical to BrSCR-29 (AB067449.1), which is named BnS-7 in B. napus[17]. To confirm that the 11 SC accessions had BnS-7 (BrS-29) on the A genome, primer pair SRK29-1a/SRK29-1b was designed based on a fragment deletion of BnSRK-7 compared with sequences BnSRK-6 and BnSRK-1300. The 11 SC accessions yielded identical 300-bp fragments, but S-1300 did not (Figure 1). This fragment was 100% identical to BrSRK-29 (AB008191.1), confirming that BnS-7 (BrS-29) was on the A genome.

Gene expression of SRKand SCR

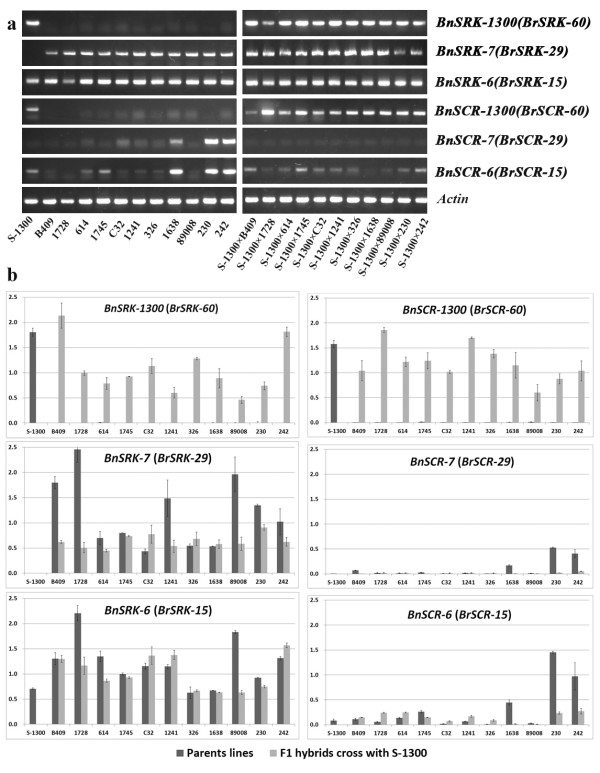

To detect relationships between S-locus genes expression and SI phenotype, specific primers based on S-locus genes were designed for qRT-PCR (Additional file 1: Table S1). Stigmas from parents and F1 hybrids, BnSRK-7 and BnSRK-6 expressed normally (Figure 2a) at a mean value of 1.05 (Figure 2b). Thus, SRK genes expression is co-dominant in stigma.

Figure 2.

SRK and SCR expression in parental lines (S-1300 and 11 SC accessions) and F 1 hybrids. (a) Semi-quantitative real-time PCR (b) Quantitative real-time PCR, Error bars represent standard error (n = 3).

In anther of self-incompatible S-1300 and F1 hybrids, BnSCR-1300 transcripts were present at high levels (>0.6), while BnSCR-7 and/or BnSCR-6 were nearly undetectable (Figure 2b). BnSCR-7 was only expressed in anthers from three males (1638, 230, and 242) (Figure 2a), with expression values of 0.17, 0.52, and 0.41 (Figure 2b), respectively; no expression was detected in other males (Figure 2a). Similarly, BnSCR-6 was expressed in 1638, 230, and 242 (Figure 2a), with values of 0.44, 1.45, and 0.97, respectively (Figure 2b), but little or no expression in other lines (<0.3) (Figure 2b). Thus, BnSCR-1300 expression is necessary for the SI of S-1300 and F1 hybrids, and diverse expression patterns of the SCR genes occur across SC accessions.

Cloning and sequence analysis of S-locus genes

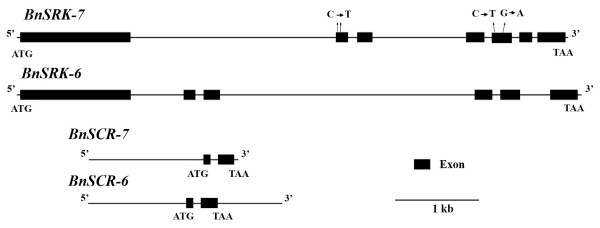

Sequence mutations in the BnS-6 and BnS-7 S-locus genes are thought to be responsible for recessive SC. Thus, 11 SC accessions were used to clone SRK from the A and C genomes. Primer combinations BnSRK7-2a/BnSRK7-2b (Additional file 2: Table S2) produced a 2590-bp sequence that contained the full BnSRK-7 CDS. Sequence alignment showed that 10 SC accessions were 100% identical to BrSRK-29 (AB008191.1), with four different base pairs in line C32 dispersed in exons 2 and 5 (Figure 3). Primer pair BnSRK6-1a/BnSRK6-1b produced a 2577-bp fragment with the full-length BnSRK-6 CDS from each SC accession. These fragments shared 100% sequence identity with BnSRK-6 (AB270772.1).

Figure 3.

Structure of S -locus genes and nucleotide sequence alignment. Arrows sites show 4 base pairs diversity dispersed in exons 2 and 5 of C32.

As only three male SC accessions (1638, 230, and 242) expressed BnSCR-7 and BnSCR-6 (Figure 2), cDNA from their anthers was used as template to clone the full CDS of SCR. Fragments 340-bp and 292-bp in length were obtained with primer pairs BnSCR7-2/BnSCR7-4 and BnSCR6-1a/BnSCR6-1b (Additional file 2: Table S2), respectively, with 100% identity to BrSCR-29 (AB067449.1) and BnSCR-6 (AB270774.1), respectively.

Primer combinations were developed to amplify genomic DNA including the 5′ promoter regions of BnSCR-7 and BnSCR-6. Primer combination BnSCR7-3/BnSCR7-4 amplified a 1784-bp fragment of BnSCR-7 that included 1367-bp 5′ upstream of the translation initiation site (Additional file 2: Table S2). All BnSCR-7 sequences from the 11 SC accessions were 100% identical. Combination of the CDS and genomic DNA sequences revealed that BnSCR-7 is 367-bp long and contains two exons and one intron.

Primer combinations BnSCR6-4a/BnSCR6-4b and BnSCR6-2a/BnSCR6-2b were developed to amplify 1193-bp and 1268-bp fragments of BnSCR-6, respectively. A 2320-bp fragment was obtained by combining the two fragments. This fragment encompasses 1176-bp of sequence 5′ upstream of the translation initiation site. All obtained BnSCR-6 sequences were 100% identical. Combining the CDS and genomic DNA sequences indicated that BnSCR-6 is 377-bp long, with two exons and one intron. Taken together, these observations show that the full genomic DNA sequences, including the 5′ promoter regions of SCR, have no sequence variation in 11 SC accessions, regardless of differences in expression.

Genetic analysis of recessive SC

The F2 populations and two BC1 populations from six males were used for genetic analysis of recessive SC. Segregation of the SI/SC phenotype demonstrated that the SC of three males (1728, 614, and 1638) was controlled by a single locus (Table 3). However, χ2 values >3.84 were observed in populations (S-1300 × 326) × 326, (S-1300 × 230) × 230, (S-1300 × 89008) × 89008, and (S-1300 × 89008) F2, revealing that the SC of lines 326, 230, and 89008 was not controlled by a single locus. Separate analyses of four males (614, 326, 230, and 89008) conducted over two years returned similar results (Table 3).

Table 3.

Genotypes and phenotypes in segregating populations

| Population | Genotype a | SI/SC phenotype | Expected ratio | χ 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S 1300 | S BnS-7 | S 1300 S BnS-7 | ||||

| Year 2012 | ||||||

| (S-1300 × 1728) × S-1300 | 84/0b | 78/0 | 162/0 | 1:0 | 0 | |

| (S-1300 × 1728) × 1728 | 11/28 | 27/9 | 38/37 | 1:1 | 0.03 | |

| (S-1300 × 1728) F2 | 33/0 | 12/26 | 48/7 | 93/33 | 3:1 | 0.1 |

| (S-1300 × 614) × S-1300 | 111/0 | 105/0 | 216/0 | 1:0 | 0 | |

| (S-1300 × 614) × 614 | 9/69 | 65/15 | 74/84 | 1:1 | 0.64 | |

| (S-1300 × 614) F2 | 35/0 | 9/31 | 71/12 | 115/43 | 3:1 | 0.36 |

| (S-1300 × 1638) × S-1300 | 56/0 | 55/0 | 111/0 | 1:0 | 0 | |

| (S-1300 × 1638) × 1638 | 9/49 | 54/12 | 63/61 | 1:1 | 0.04 | |

| (S-1300 × 1638) F2 | 37/0 | 14/27 | 67/8 | 118/35 | 3:1 | 0.44 |

| (S-1300 × 326) × S-1300 | 73/0 | 76/0 | 149/0 | 1:0 | 0 | |

| (S-1300 × 326) × 326 | 93/172 | 232/22 | 325/194 | 1:1 | 32.56 | |

| (S-1300 × 326) F2 | 122/0 | 24/93 | 196/37 | 342/130 | 3:1 | 1.56 |

| (S-1300 × 230) × S-1300 | 42/0 | 38/0 | 80/0 | 1:0 | 0 | |

| (S-1300 × 230) × 230 | 8/48 | 62/0 | 70/48 | 1:1 | 3.74 | |

| (S-1300 × 230) F2 | 54/0 | 7/38 | 85/0 | 146/38 | 3:1 | 1.63 |

| (S-1300 × 89008) × S-1300 | 43/0 | 36/0 | 79/0 | 1:0 | 0 | |

| (S-1300 × 89008) × 89008 | 11/28 | 31/0 | 42/28 | 1:1 | 2.41 | |

| (S-1300 × 89008) F2 | 42/0 | 16/33 | 87/0 | 145/33 | 3:1 | 4.57 |

| Year 2013 | ||||||

| (S-1300 × 614) × S-1300 | 57/0 | 64/0 | 121/0 | 1:0 | 0 | |

| (S-1300 × 614) × 614 | 13/33 | 40/12 | 53/45 | 1:1 | 0.66 | |

| (S-1300 × 614) F2 | 33/0 | 11/23 | 72/15 | 116/38 | 3:1 | 0.03 |

| (S-1300 × 326) × S-1300 | 61/0 | 57/0 | 118/0 | 1:0 | 0 | |

| (S-1300 × 326) × 326 | 19/40 | 53/15 | 72/55 | 1:1 | 2.02 | |

| (S-1300 × 326) F2 | 33/0 | 15/24 | 55/12 | 103/36 | 3:1 | 0.35 |

| (S-1300 × 230) × S-1300 | 112/0 | 124/0 | 236/0 | 1:0 | 0 | |

| (S-1300 × 230) × 230 | 16/35 | 49/0 | 65/35 | 1:1 | 8.41 | |

| (S-1300 × 230) F2 | 21/0 | 5/23 | 54/0 | 80/23 | 3:1 | 0.15 |

| (S-1300 × 89008) × S-1300 | 30/0 | 0 | 25/0 | 55/0 | 1:0 | 0 |

| (S-1300 × 98008) × 89008 | 0 | 7/13 | 21/0 | 28/13 | 1:1 | 4.78 |

| (S-1300 × 89008) F2 | 34/0 | 14/21 | 71/0 | 119/21 | 3:1 | 6.94 |

SI: self-incompatible, SCI <2; SC: self-compatible, SCI ≥2.

aPrimer combinations SRKa-L/SRKa-R and SRK29-1a/SRK29-1b were used to detect BnS-1300 and BnS-7, respectively.

bNumber of investigated plants with the SI/SC phenotype.

Primer combinations SRKa-L/SRKa-R and SRK29-1a/SRK29-1b (Table 2), were used to determine the inheritance of S1300 and SBnS-7 and to clarify the role of S genotypes in determining the SI phenotype. All S1300S1300 plants were completely SI in all progeny from six accessions; all S1300SBnS-7 plants were SI in progenies from lines 230 and 89008. However, SI plants of genotype SBnS-7SBnS-7 were observed in all populations, and some plants with genotype S1300SBnS-7 were SC in a population descended from four males (1728, 614, 1638, and 326) (Table 3). These results suggest that factor(s) independent of the S locus are involved in recessive SC, but that the S haplotype BnS-1300 in the A genome is necessary for SI.

Discussion

Recessive SC in B. napushas diverse causes

SI has been used for hybrid breeding in B. rapa and B. oleracea. As B. napus is an oil crop, its hybrids should be fertile for harvesting seeds. On the other hand, a SI line must be propagated on a large scale to produce many hybrid seeds. The SI of line S-1300 is recessive in most accessions but dominant in some genetic backgrounds [21]. Therefore, it has been utilized for three-component hybrid breeding via SI F1 hybrids [21, 26]. Recessive SC lines thus play a key role in hybrid breeding.

Here, 11 accessions were screened to identify stable recessive SC and had the S genotype BnS-7/BnS-6. In 8/11 accessions, expression of BnSCR-7 and BnSCR-6 was nearly absent, but SRK genes were expressed at normal levels (Figure 2). SRK genes in these accessions contained no CDS mutations, with the exception of 4-bp in BnSRK-7 in line C32 (Figure 3). These data indicate that SC is caused by the loss of function of BnSCR-7 and BnSCR-6 in the pollen of these eight accessions. However, BnSCR-7 and BnSCR-6 harbor no structural mutations in the promoters of these lines, rendering the mechanism of this loss of function unclear.

Sequence insertion/deletion causing loss-function of SCR was previously reported to cause SC. The SC B. rapa cultivar Yellow Sarson, which has a self-compatible class-I S haplotype (S-f2), contains an 89-bp deletion in the SCR promoter region; this deletion resulted in the production of no transcript, which caused the loss of function in the S-f2 homozygote. The expression of recessive class-II SCR-60 was suppressed in the S-f2/S-60 heterozygote by non-functional class-I SCR-f2[27]. No expression of the class-I dominant SCR on the A genome resulted from the insertion of ~3.6 kb in the promoter region; this insertion’s suppression of the recessive locus BnSCR-6 on the C genome explains the SC of B. napus accessions with the S genotype of BnS-1/BnS-6[17, 19]. SC in A. thaliana is also caused by a 213-bp inversion in the male-specific gene SCR that inhibits the transcription of SCR[28]. However, we were surprised that SRK and SCR were expressed normally in three SC accessions in the present investigation (Figure 2). The SCR and SRK CDSs in these lines had no mutations relative to BrS-29 and BoS-15, implying that other factors contribute to SC by taking part in translational repression. Therefore, diverse causes result in recessive SC in B. napus.

Factor(s) independent of the Slocus contribute to SC in B. napus

Other factor(s) independent of the S locus may control recessive SC, based on our observations that S1300S1300 plants are completely SI, while SBnS-7SBnS-7 and S1300SBnS-7 plants segregated SI phenotypes in their progeny (Table 3). These observations are consistent with those of Ekuere et al. [16], who identified a latent S allele in at least two oilseed rape cultivars; the S phenotype of these latent alleles was masked by a suppressor system common to oilseed rape. A modifier was also proposed to cause transient SI in A. thaliana[29, 30]. Liu et al. [31] demonstrated that transient SI is caused by a hypomorphic allele of PUB8 that regulates SRK transcript levels, and suggested that disruption or down-regulation of the S-locus recognition genes was a major mechanism for the switch to self-fertility in A. thaliana. Although genetic analyses are not completely consistent with our previous results [23, 24], SI plants with genotype SBnS-7SBnS-7 and SC plants with genotype S1300SBnS-7 are useful for mapping and characterizing the other factor(s) or suppressor(s) in this system.

In the Brassicaceae, self-recognition involves SRK-SCR interaction and signal transmission. Any factor that suppresses mRNA expression of SRK or SCR or disrupts subsequent signal transduction would cause the breakdown of SI. Several proteins have been shown to affect SI response in Brassica, such as the armadillo repeat-containing protein ARC1 [32], the thioredoxin h-like proteins THL1 and THL2 [33], and M-locus protein kinase MLPK [34]. However, MLPK, ARC1, and Exo70A1 orthologs do not contribute to the SI response in A. thaliana SRK-SCR transformants [35]. The ARC1-related U-box gene AtPUB2, which is highly expressed in the stigma, does not function in SI either [36]. Further investigations will be needed to determine whether the factor(s) proposed in the present study consist of these proteins.

Dominant/recessive relationships in recessive class-II Shaplotypes

In general, S haplotypes in Brassica exhibit dominant/recessive relationships in pollen and co-dominant relationships in stigma [9]. Some S haplotypes are hierarchically dominant; in B. rapa, the order is S9 > S44 > S60 > S40 > S29[37]. Of these S haplotypes, S44, S60, S40 are dominant in some cases but recessive in others, based on the expression level of SCR[38]. The SI line S-1300 and 11 recessive SC accessions have a common S haplotype (BnS-6) on the C genome, but different S haplotypes on the A genome (BnS-1300 in S-1300 and BnS-7 in the 11 accessions). BnSCR-1300 (similar to BrSCR-60) was only expressed in S-1300 and the 11 F1 hybrids, while BnSCR-7 (similar to BrSCR-29) and BnSCR-6 (similar to BoSCR-15) were nearly undetectable (Figure 2). In pollen, BrSCR-60 is dominant over BrSCR-29[39]. The SI of F1 hybrids may be due to the dominant, functional BnSCR-1300 on the A genome, to which BnSCR-7 is recessive.

Dominant/recessive relationships between class-I and class-II S haplotypes are regulated by DNA methylation of the promoter of the recessive SCR gene [40]; this methylation is triggered by a trans-acting small non-coding RNA [41]. However, the mechanism underlying the dominant/recessive relationships between two class-II S haplotypes has not been reported to date. Previously, BoSCR-15 was 95.5% identical at the amino-acid level to BrSCR-60, but only 57.6% identical to BrSCR-29[12]. If the dominant/recessive relationship between two S haplotypes in B. rapa and B. oleracea is present in B. napus, as observed by Okamoto et al. [17], then BnSCR-1300 and BnSCR-6 may be co-dominant, with both dominant to BnSCR-7. However, we did not detect BnSCR-6 transcripts in the SI line S-1300, and neither BnSCR-6 nor BnSCR-7 was expressed in the anthers of eight SC accessions; the other three SC accessions clearly expressed BnSCR-6 and BnSCR-7 (Figure 2). Our observations cannot be explained by any dominant/recessive relationship among the class-II BnSCR-1300, BnSCR-6, and BnSCR-7. The SI line S-1300 and the recessive SC accessions employed here are unique materials for dissecting the dominant/recessive relationship and its mechanisms in class-II S haplotypes.

Much progress has been made toward elucidating the mechanism of SC in B. napus, but many questions persist, such as the roles of SRK and SCR in self-recognition, the dominant/recessive relationships between recessive class-II S haplotypes, and the identities and functions of other factors involved in SI singling. Our study provides insight into the complex mechanisms of SC in B. napus, laying the groundwork to characterize the novel factor(s) affecting S-locus gene expression and SI signaling. Dissecting these pathways will help elucidate the mechanisms of recessive SC and further our understanding of the evolution of plants from diploid to autoploid species and the changes in self-fertility during polyploidization.

Conclusion

The recessive self-compatible accessions screened in this study had two common class-II S haplotypes: BnS-6 on the C genome and BnS-7 on the A genome. Our observations of different BnSCR-6 and BnSCR-7 expression patterns across SC accessions, the reliance of SI on the expression of BnSCR-1300 rather than SRK genes, and the contributions to SI phenotypes of factor(s) independent of the S locus according to the inheritance of segregating populations suggest that diverse causes underlie recessive SC in B. napus, yielding insight into these complex mechanisms and laying the groundwork to characterize the novel factor(s) affecting S-locus gene expression and SI signaling.

Methods

Plant material

Self-incompatible line S-1300 and 30 cultivated self-compatible B. napus accessions used in this study are highly inbred lines (Table 1). Line S-1300 contains low erucic acid and low glucosinolates and is derived from the double-high SI line 271, which was bred by introgressing an S haplotype of B. rapa Xishuibai into a B. napus line through interspecific hybridization [42, 43]. These lines are Chinese semi-winter types and are conserved in Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China.

Line S-1300 was crossed as a female with the self-compatible B. napus accessions to obtain F1 hybrids in March 2009, in Wuhan (located on the central of China). F1 hybrids were artificially bud-pollinated to produce F2 populations and separately backcrossed with the female and males to generate BC1 populations in March 2011 in Wuhan. Phenotypes of F1 hybrids were investigated in two natural environments: in May 2010 in Wuhan and in August 2010 in Lanzhou (located on the northwest of China). Because of large and hard work of investigating SI phenotype, F2 and BC1 populations deriving only from 6 males were randomly selected and investigated in May of 2012. In 2013 in Wuhan, 3 males whose recessive SC controlled by at least two loci repeated separate analyses, and one male whose recessive SC controlled by one locus was used as control, as our original focus was on the modifier might existed in the recessive SC accessions.

Determination of SC index (SCI) and SI phenotype

SCI and SI phenotypes were determined using the methods previously described [20]: When 3–5 flowers were present on the major inflorescence of each plant, the major inflorescence and 2–3 branches were bagged. The bags were slapped gently every two days to ensure self-pollination and were removed two weeks later to allow natural seed development. After the seed pods matured, the seeds and flowers were counted, and the SCI was calculated as the number of seeds divided by the number of flowers. Approximately 100–150 flowers from each plant were investigated. SI phenotype of each plant were categorized as SCI <2 (SI), 2 ≤ SCI <10 (partially SI) and SCI ≥10 (SC).

DNA isolation and PCR

Genomic DNA of each plant from SI line S-1300, 11 SC accessions, 11 SI F1 hybrids and 4552 individuals of F2 and BC1 populations, was isolated from young leaves using cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide [44]. DNA concentration was measured using a Beckman spectrophotometer. DNA from three individuals in each of the SI line S-1300, 11 SC accessions and 11 SI F1 hybrids was mixed for PCR analysis. PCR was performed on a thermocycler (Model PTC-225, MJ Research) in a volume of 20 μL including 50 ng DNA template, 0.2 mM dNTP mix (Sangon, China), 0.5 μM of each primer, 1 U Taq DNA polymerase (MBI Fermentas, USA), 2.0 mM MgCl2, and 2 μL 10× Taq buffer. The PCR mixture was covered with 20 μL mineral oil [18]. PCR products were separated on a 1.0% agarose gel in 1× TAE buffer and detected by staining with ethidium bromide.

RNA analysis

Thirty stigmas or anthers of mature buds from each of the SI S-1300 line and 11 F1 hybrids and the 11 SC accessions were taken into a 2.0 ml tube placing on a box filled with liquid nitrogen gas. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA). Reverse transcription (RevertAid™ First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit, Fermentas, USA) was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The first-strand cDNA mixture was diluted 10-fold with sterile distilled water and used as a template to amplify cDNAs of SRK or SCR for semi-quantitative real-time PCR. Quantitative real-time PCR was also performed on a Bio-Rad CFX-96 with SYBR Green (Bio-Rad, USA). Actin (GeneBank accession number: AF111812) was amplified and used as a positive control. PCR was performed under the following conditions: 95°C for 3 min, followed by 47 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Relative transcript levels were determined by the comparative 2-ΔΔCT method [45] in triplicate. All primers are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. Primers were designed with Primer Premier 5.0 (http://www.PremierBiosoft.com) and synthesized by Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA.

Cloning and sequence analysis

A homologous candidate gene approach was used to generate the full coding DNA sequences (CDSs) of SRK and full sequences with the 5′ promoter regions of SCR in 11 SC B. napus accessions based on the CDSs of BnS-7 (BrS-29) on the A genome and BnS-6 (BoS-15) on the C genome. As B. rapa S-60, B. rapa S-29, and B. oleracea S-15 are class-II S haplotypes with high sequence similarity, their sequence differences were taken into consideration when designing primers (Additional file 2: Table S2).

DNA fragments were excised from a 1.0% agarose gel, purified using the UNIQ-10 column Gel Recovery Kit (Sangon, China), and ligated into vector PMD18-T (Takara, Japan). Positive transformed clones were screened by PCR with M13-specific primers. Three positive clones from each ligation were sequenced with an ABI 3730 automatic sequencer (Sangon, China). Sequence analysis was performed using BLAST [46], ClustalX 2.0 [47], and DNASTAR (Windows version 5.0.2, DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA).

Electronic supplementary material

Additional file 1: Table S1: Primers used to analyze the expression of SRK and SCR. (XLSX 10 KB)

Additional file 2: Table S2: Primers for cloning SRK and SCR. (XLSX 10 KB)

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Doctoral Fund of Ministry of Education (20110146110023), the National Support Plan (2010BAD01B), the Central College Fund (2011PY155), and the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (2011AA10A104, 2012AA101107).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ZW designed and carried out the S haplotype identification, expression analysis and gene cloning. JZ and YY participated in genetic analysis. CM conceived of and supervised the overall research. ZL, CG and GZ participated in field experimentation. ZW and CM wrote the manuscript. JT, JS and TF helped draft the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Wen Zhai, Email: zhaiwen1105@163.com.

Jianfeng Zhang, Email: zjf@webmail.hzau.edu.cn.

Yong Yang, Email: yongyang218@163.com.

Chaozhi Ma, Email: yuanbeauty@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Zhiquan Liu, Email: lzq0826@qq.com.

Changbin Gao, Email: gaocb1983@sina.com.

Guilong Zhou, Email: ZHOUGL0527@163.com.

Jinxing Tu, Email: tujx@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Jinxiong Shen, Email: jxshen@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Tingdong Fu, Email: futing@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Bateman AJ. Self-incompatibility systems in angiosperms. III. Cruciferae. Heredity. 1955;9:53–58. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1955.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stein JC, Howlett B, Boyes DC, Nasrallah ME, Nasrallah JB. Molecular cloning of a putative receptor protein kinase gene encoded at the self-incompatibility locus of Brassica oleracea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(19):8816–8820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schopfer CR, Nasrallah ME, Nasrallah JB. The male determinant of self-incompatibility in Brassica. Science. 1999;286(5445):1697–1700. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki G, Kai N, Hirose T, Fukui K, Nishio T, Takayama S, Isogai A, Watanabe M, Hinata K. Genomic organization of the S locus: identification and characterization of genes in SLG/SRK region of S(9) haplotype of Brassica campestris (syn. rapa) Genetics. 1999;153(1):391–400. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.1.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nasrallah JB, Nasrallah ME. Pollen-stigma signaling in the sporophytic self-incompatibility response. Plant Cell. 1993;5(10):1325–1335. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.10.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kachroo A, Schopfer CR, Nasrallah ME, Nasrallah JB. Allele-specific receptor-ligand interactions in Brassica self-incompatibility. Science. 2001;293(5536):1824–1826. doi: 10.1126/science.1062509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takayama S, Shimosato H, Shiba H, Funato M, Che FS, Watanabe M, Iwano M, Isogai A. Direct ligand-receptor complex interaction controls Brassica self-incompatibility. Nature. 2001;413(6855):534–538. doi: 10.1038/35097104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimosato H, Yokota N, Shiba H, Iwano M, Entani T, Che FS, Watanabe M, Isogai A, Takayama S. Characterization of the SP11/SCR high-affinity binding site involved in self/nonself recognition in brassica self-incompatibility. Plant Cell. 2007;19(1):107–117. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.038869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nasrallah JB, Nishio T, Nasrallah ME. The self-incompatibility genes of Brassica: expression and Use in genetic ablation of floral tissues. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1991;42:393–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.42.060191.002141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nou IS, Watanabe M, Isogai A. Comparison of S-alleles and S-glycoproteins between two wild populations of Brassica campestris in Turkey and Japan. Sex Plant Reprod. 1993;6:79–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00227652. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ockendon DJ. The S-allele collection of Brassica oleracea. Acta Hort. 2000;539:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sato Y, Sato K, Nishio T. Interspecific pairs of class II S haplotypes having different recognition specificities between Brassica oleracea and Brassica rapa. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;47(3):340–345. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacKay GR. The introgression of S-alleles into forage rape, Brassica napus L. from turnip, Brassica campestris L. ssp. rapifera. Euphytica. 1977;26:511–519. doi: 10.1007/BF00027020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goring DR, Banks P, Fallis L, Baszczynski CL, Beversdorf WD, Rothstein SJ. Identification of an S-locus glycoprotein allele introgressed from B. napus ssp. rapifera to B. napus ssp. oleifera. Plant J. 1992;2(6):983–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rahman MH. Resynthesis of Brassica napus L. for self-incompatibility: self-incompatibility reaction, inheritance and breeding potential. Plant Breed. 2005;124:13–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2004.01045.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekuere UU, Parkin IA, Bowman C, Marshall D, Lydiate DJ. Latent S alleles are widespread in cultivated self-compatible Brassica napus. Genome. 2004;47(2):257–265. doi: 10.1139/g03-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okamoto S, Odashima M, Fujimoto R, Sato Y, Kitashiba H, Nishio T. Self-compatibility in Brassica napus is caused by independent mutations in S-locus genes. Plant J. 2007;50(3):391–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, Ma C, Tang J, Tang W, Tu J, Shen J, Fu T. Distribution of S haplotypes and its relationship with restorer-maintainers of self-incompatibility in cultivated Brassica napus. Theor Appl Genet. 2008;117(2):171–179. doi: 10.1007/s00122-008-0763-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tochigi T, Udagawa H, Li F, Kitashiba H, Nishio T. The self-compatibility mechanism in Brassica napus L. is applicable to F1 hybrid breeding. Theor Appl Genet. 2011;123(3):475–482. doi: 10.1007/s00122-011-1600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang XG, Ma CZ, Fu TD, Li YY, Wang TH, Chen QF, Tu JX, Shen JX. Development of SCAR markers linked to self-incompatibility in Brassica napus L. Mol Breed. 2008;21:305–315. doi: 10.1007/s11032-007-9130-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma CZ, Jiang YF, Dan F, Dan B, Fu TD. Breeding for maintainer of self-incompatible lines and its potential in Brassica napus L. J Huazhong Agric Univ. 2003;22:13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao CB, Ma CZ, Zhang XG, Li FP, Zhang JF, Zhai W, Wang YY, Tu JX, Shen JX, Fu TD. The genetic characterization of self-incompatibility in a Brassica napus line with promising breeding potential. Mol Breed. 2013;31:485–493. doi: 10.1007/s11032-012-9805-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang J, Zhang J, Ma C, Tang W, Gao C, Li F, Wang X, Liu Y, Fu T. CAPS and SCAR markers linked to maintenance of self-incompatibility developed from SP11 in Brassica napus L. Mol Breeding. 2009;24(3):245–254. doi: 10.1007/s11032-009-9287-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma CZ, Li CY, Tan YQ, Tang W, Zhang JF, Gao CB, Fu TD. Genetic analysis reveals a dominant S locus and an S suppressor locus in natural self-compatible Brassica napus. Euphytica. 2009;166:123–129. doi: 10.1007/s10681-008-9846-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishio T, Kusaba M, Watanabe M, Hinata K. Registration of S alleles in Brassica campestris L by the restriction fragment sizes of SLGs. Theor Appl Genet. 1996;92(3–4):388–394. doi: 10.1007/BF00223684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu TD. Production and research of rapeseed in the People’s Republic of China. Eucarpia Cruciferae Newsl. 1981;6:6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujimoto R, Sugimura T, Fukai E, Nishio T. Suppression of gene expression of a recessive SP11/SCR allele by an untranscribed SP11/SCR allele in Brassica self-incompatibility. Plant Mol Biol. 2006;61(4–5):577–587. doi: 10.1007/s11103-006-0032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsuchimatsu T, Suwabe K, Shimizu-Inatsugi R, Isokawa S, Pavlidis P, Stadler T, Suzuki G, Takayama S, Watanabe M, Shimizu KK. Evolution of self-compatibility in Arabidopsis by a mutation in the male specificity gene. Nature. 2010;464(7293):1342–1346. doi: 10.1038/nature08927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nasrallah ME, Liu P, Nasrallah JB. Generation of self-incompatible Arabidopsis thaliana by transfer of two S locus genes from A. lyrata. Science. 2002;297(5579):247–249. doi: 10.1126/science.1072205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nasrallah ME, Liu P, Sherman-Broyles S, Boggs NA, Nasrallah JB. Natural variation in expression of self-incompatibility in Arabidopsis thaliana: implications for the evolution of selfing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(45):16070–16074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406970101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu P, Sherman-Broyles S, Nasrallah ME, Nasrallah JB. A cryptic modifier causing transient self-incompatibility in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr Biol. 2007;17(8):734–740. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gu T, Mazzurco M, Sulaman W, Matias DD, Goring DR. Binding of an arm repeat protein to the kinase domain of the S-locus receptor kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(1):382–387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bower MS, Matias DD, Fernandes Carvalho E, Mazzurco M, Gu T, Rothstein SJ, Coring DR. Two members of the thioridoxin-h family interact whith the kinase domain of a Brassica S locus receptor kinase. The Plant Cell. 1996;8:1641–1650. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.9.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murase K, Shiba H, Iwano M, Che FS, Watanabe M, Isogai A, Takayama S. A membrane-anchored protein kinase involved in Brassica self-incompatibility signaling. Science. 2004;303(5663):1516–1519. doi: 10.1126/science.1093586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kitashiba H, Liu P, Nishio T, Nasrallah JB, Nasrallah ME. Functional test of Brassica self-incompatibility modifiers in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(44):18173–18178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115283108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang J, Rea AC, Fu T, Ma C, Nasrallah JB. Exploring the role of a stigma-expressed plant U-box gene in the pollination responses of transgenic self-incompatible Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Reprod. 2014;27:59–68. doi: 10.1007/s00497-014-0240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hatakeyama K, Watanabe M, Takasaki T, Ojima K. Dominance relationships between S-alleles in self-incompatible Brassica campestris L. Heredity. 1998;80:241–247. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2540.1998.00295.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shiba H, Iwano M, Entani T, Ishimoto K, Shimosato H, Che FS, Satta Y, Ito A, Takada Y, Watanabe M, Isogai A, Takayama S. The dominance of alleles controlling self-incompatibility in Brassica pollen is regulated at the RNA level. Plant Cell. 2002;14(2):491–504. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kakizaki T, Takada Y, Ito A, Suzuki G, Shiba H, Takayama S, Isogai A, Watanabe M. Linear dominance relationship among four class-II S haplotypes in pollen is determined by the expression of SP11 in Brassica self-incompatibility. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003;44(1):70–75. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiba H, Kakizaki T, Iwano M, Tarutani Y, Watanabe M, Isogai A, Takayama S. Dominance relationships between self-incompatibility alleles controlled by DNA methylation. Nat Genet. 2006;38(3):297–299. doi: 10.1038/ng1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tarutani Y, Shiba H, Iwano M, Kakizaki T, Suzuki G, Watanabe M, Isogai A, Takayama S. Trans-acting small RNA determines dominance relationships in Brassica self-incompatibility. Nature. 2010;466(7309):983–986. doi: 10.1038/nature09308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fu TD, Liu HL. Preliminary report on breeding of self-incompatible lines of Brassica napus. Oil Crop China. 1975;4:77–85. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma CZ, Fu TD, Yang GS, Tu JX, Yang XN, Dan F. Breeding for self-incompatibility lines with double-zero on Brassica napus L. J Huazhong Agric Univ. 1998;17(3):211–213. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus. 1990;12:13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(21):2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1: Primers used to analyze the expression of SRK and SCR. (XLSX 10 KB)

Additional file 2: Table S2: Primers for cloning SRK and SCR. (XLSX 10 KB)