Abstract

Circulating triglycerides (TG) normally increase after a meal but are altered in pathophysiological conditions such as obesity. Although TG metabolism in the brain remains poorly understood, several brain structures express enzymes that process TG-enriched particles, including mesolimbic structures. For this reason, and because consumption of high fat diet alters dopamine signaling, we tested the hypothesis that TG might directly target mesolimbic reward circuits to control reward-seeking behaviors. We found that the delivery of small amounts of TG to the brain through the carotid artery rapidly reduced both spontaneous and amphetamine-induced locomotion, abolished preference for palatable food, and reduced the motivation to engage in food-seeking behavior. Conversely, targeted disruption of the TG-hydrolyzing enzyme lipoprotein lipase specifically in the nucleus accumbens increased palatable food preference and food seeking behavior. Finally, prolonged TG perfusion resulted in a return to normal palatable food preference despite continued locomotor suppression, suggesting that adaptive mechanisms occur. These findings reveal new mechanisms by which dietary fat may alter mesolimbic circuit function and reward seeking.

Keywords: Dietary triglyceride, reward, motivation, amphetamine, feeding behavior, nucleus accumbens, lipoprotein lipase

INTRODUCTION

The regulation of energy balance depends on the ability of the brain to provide an adaptive response to changes in circulating factors of hunger and satiety 1-3. The hypothalamus is regarded as a key integrative structure in the homeostatic control of energy balance, but feeding behavior is also modulated by sensory input (e.g., tastes and odors) and emotional state 4-8. Calorie-dense foods and other objects of desire (e.g., sex, drugs) stimulate dopamine release, a key signal underlying their potent reinforcing properties 9, 10, 11 , 12. In particular, the projection of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens (NAc) is a crucial substrate upon which drugs of abuse exert their effect and thus this projection is often referred to as the brain’s ‘reward circuit’. As with drugs of abuse, this projection is a substrate upon which calorie-rich foods act to promote positive reinforcement, and adaptations in this circuit may underlie the downward spiral of uncontrolled craving, compulsive over-consumption, and ultimately obesity 7, 12-15.

Indeed, multiple lines of evidence now suggest that obesity or chronic exposure to a high sucrose high fat diet is associated with deficits in the reward system11, 14-19. For example, striatal levels of the dopamine D2 receptor (D2R) are inversely related to body weight and D2R knockdown rapidly accelerates the development of addiction-like reward deficits in rats with extended access to high fat food 14. In humans, obesity is associated with decreased striatal DA release in response to palatable food intake 16 but also with greater activation of the reward system during food reward anticipation 11, 15, 16, 19-21. Furthermore, animals consuming high fat diet, independent of obesity, exhibit decreased dopamine turnover in cortical and striatal structures, reduced preference for psychostimulants, attenuated operant responding for sucrose, and cognitive deficits 22. Moreover, obesity-associated cognitive impairment can be improved by selective lowering of circulating triglyceride (TG), while intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection of TG impairs learning in normal mice 23. Together, these observations raise the possibility that nutritional lipid, particularly TG, directly affect cognitive and reward processes.

Circulating lipids are found as non-esterified long-chain fatty acids (LCFA) but also esterified and packaged into TG-rich particles such as chylomicrons or liver-born very low density lipoprotein (VLDL). TG and LCFAs are both circulating lipid species but their physiological entries into plasma differ drastically. LCFA typically increase in response to a fast due to adipose lipolysis – while TG-rich particles accumulate after a meal 24. While LCFA metabolism at the level of the hypothalamus regulates energy balance 25-30, little is known about brain TG sensing.

Both mesolimbic and hypothalamic regions express enzymes involved in the transport, manipulation, and metabolism of TG 31-38. In particular, the hippocampus and the NAc express lipoprotein lipase (LpL), a key enzyme involved in TG hydrolysis 39. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of brain TG hydrolysis in the regulation of energy balance 40 and the variation in circulating TG after a high-fat meal was a strong predictor for hyperphagia and obesity 41 but until now a physiological model that allows for the study of TG action on the brain has been missing.

Here we describe a novel physiological model in which freely moving mice receive small amounts of TG emulsion infused through the carotid artery in the direction of the brain. Without affecting circulating lipids or body weight, brain TG delivery rapidly reduced spontaneous and amphetamine-induced locomotion. Brain TG delivery also decreased reward seeking while NAc-selective knockdown of LpL increased reward seeking. Finally, brain TG delivery abolished preference for palatable food while NAc-specific LpL knockdown increased palatable food intake. Based on these data, we conclude that LpL-mediated hydrolysis of nutritional TG within the mesolimbic system modulates reward impact.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and diets

All animal experiments were performed with approval of the Animal Care Committee of the University Paris Diderot-Paris 7. Ten week old male mice C57Bl/6J (25-30g, Janvier, Le Genest St Isle, France)were housed individually in stainless steel cages in a room maintained at 22 ± 3°C with light from 0700 to 1900 hours. 8-10 weeks old Animals C57Bl/6J were subjected to a 6-months high fat feeding to produce diet-induced obese animals (see supplementary information).

Catheter implantation procedures

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and received 10μg/kg i.p. xylazine (Rompun ®) for the insertion of a catheter in the carotid artery towards the brain. Then the catheter was exteriorized at the vertex of the head 42. Following surgery, mice received 10μg/kg i.p. ketoprofen (Ketofen ®). Catheters were kept patent through daily flushing with a solution of NaCL+ heparin (20U/ml). Infusions started after a 7-10 days recovery period.

Infusion procedures

After 10 day recovery period, catheters were connected to a swiveling infusion device, allowing the animal free movement and access to water and food. Mice were infused with saline solution (0.9% NaCl, 0.1-0.5 μl/min)for 3-4 days for habituation to the infusion device. Mice were then divided into 2 groups: one continuing to receive saline (NaCl mice) and the other receiving a triglycerides emulsion (TG mice) (Intralipid®) at a rate of 0.1-0.3 μl/min in continue during 4 days or 6 hours before Amphetamine test or Progressive ratio test.Due to small variations in catheters, we varied the pump settings slightly across animals to obtain constant flow rates of ~0.1 μl/min at the exit of the tube.

Viral production

The plasmid CBA.nls myc Cre.eGFP expressing the myc-nls-Cre-GFP fusion protein 43 was kindly provided by Richard Palmiter (Univ. of Washington, Seattle, USA). Adeno-associated virus serotype 2/9 (AAV2/9) (6×1011 genomes/ml and 1.7×108 infectious units/μl) were produced by the viral production facility of the UMR INSERM 1089 (Nantes, France).

Stereotaxic procedures

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and received 10μg/kg i.p. xylazine analgesic. They were then placed on a stereotaxic frame. AAV Cre-GFP virus were injected bilaterally into the NAc (Stereotactic co-ordinates are relative to bregma : X:±1 mm; Y:+1.5mm; Z:-4.2 mm) at a rate of 0.20 μL/min for 5 minutes per side . At the end of surgical procedures mice received 10μg/kg i.p. ketoprofen.

Measurement of locomotor activity and food intake

Metabolic analyses were performed in an automated online measurement system using high sensitivity feeding and drinking sensors and an infrared beam-based activity monitoring system (Phenomaster, TSE Systems GmbH, Bad Homburg, Germany).

Amphetamine injection

After 6 hours of TG infusion mice were given i.p. injection of saline on the first two days, and 3 mg/kg i.p. D-amphetamine (A5880, Sigma) on the subsequent two days. Locomotor activity for each animal was measured during 2 hours after Vehicle or Amphetamine injection.

Operant conditioning system

Computer-controlled operant conditioning was conducted in 12 identical conditioning chambers equipped with a swiveling infusion device (Phenomaster, TSE Systems GmbH, Bad Homburg, Germany). Each chamber contains an operant wall with a food cup, two levers located 3 cm lateral to the food cup, with the left lever designated the active lever (for food pellet delivery).To ensure responding, animals were food restricted to 90% of initial BW. The reinforcer was a single 20-mg peanut butter flavored sucrose tablet (TestDiet, Richmond, USA).

LPL activity assay

Heparin-releasable LPL activity was assayed in microdissected brain regions using a kit (RB-LPL, Roar Biomedical, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

Displayed values are means ± SEM. Variance equality was analysed by a F- test (Microsoft Excel®). Comparisons between groups were carried out using a parametric Student’s t test or by a non-parametric Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon’s test (Microsoft Excel®, Minitab®). When appropriate, repeated measures analysis were performed by using General Linear Regression analyses followed by a Bonferroni’s test with time (day or min) and groups and their interaction as factor (Minitab®). A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Central triglyceride delivery decreases locomotor activity and abolishes preference for palatable food

To assess whether TG-rich particles act as brain signaling molecules we established a model of brain-specific infusion of phospholipid TG emulsion (Intralipid 20%, 2 kcal/ml,) through the carotid artery in the direction of the brain in freely moving animals (Supplementary Figure 1a, b). To test whether TG delivered via this route is metabolized in the brain, we infused radiolabelled TG ([9,10- 3H (N)]-triolein) through the carotid artery. Detectable quantities of radiolabelled LCFA were present in brain structures known to express TG processing enzymes indicative of local TG hydrolysis (Supplementary Figure 2). Intralipid was infused at a rate of 0.1μl-0.3μl/min to approximate the physiological amount of TG entering the brain (see methods). Importantly, at this rate of infusion 24-hrs intra-carotid TG infusion does not affect circulating levels of FFA, TG or cholesterol in the periphery (Supplementary Figure 1c).

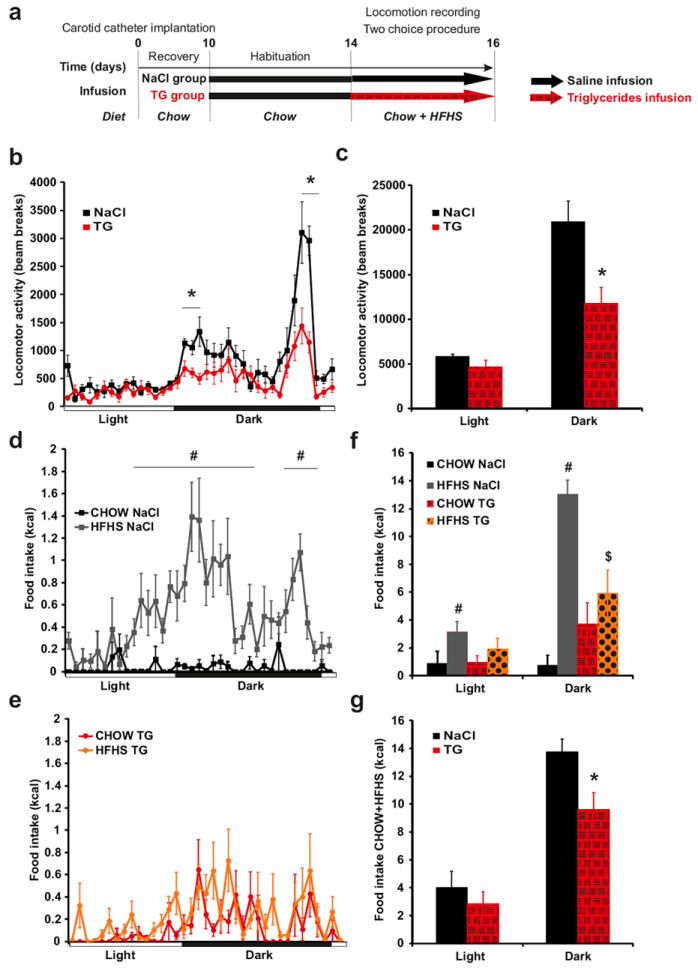

Next we assessed the behavioral and metabolic consequences of brain TG delivery using modified home cages allowing for chronic infusion while measuring food consumption, water intake, and locomotor activity. After catheter implantation mice were allowed to recover for 10 days followed by 4 days of saline infusion; during this time baseline parameters were acquired, mice were split into saline- and TG-infused groups, and presented with choice of normal chow and high fat high sucrose diet (HFHS) (Figure 1a). While both groups were indistinguishable during basal saline/chow condition (not shown), TG perfusion selectively decreased nocturnal, but not diurnal, locomotor activity (Figure 1b, c). Importantly, this action of TG on locomotion rapidly diminished when TG infusion was discontinued and animals were returned to saline infusion (Supplementary Figure 3). Consistent with the reduction in activity we found a decrease in energy expenditure at several time points of the dark period during TG infusion, as well a decrease in nocturnal respiratory quotient (Supplementary Figure 4).

Figure 1. Central triglycerides delivery specifically decreases nocturnal locomotor activity and abolishes feeding preference for palatable food.

Experimental procedure (a). Daily variation of locomotor activity (b) and cumulative locomotor activity during light and dark periods (c) in control mice (black squares and bars) and triglycerides (TG) infused mice (red circles and hatched red bars). Daily variation in chow (black squares) and HFHS (gray squares) diet intake in control mice (d). Daily variation in chow (red circles) and HFHS (orange circles) diet intake in TG infused mice (e). Cumulative food intake during light and dark periods of chow diet (control mice: black bars; TG infused mice: hatched red bars) and HFHS diet (control mice: grey bars; TG infused mice: dotted orange bars) (f). Cumulative total food intake (chow+HFHS diet) during light and dark periods in control mice (black bars) and TG infused mice (hatched red bars) (g).Locomotor and feeding recording period are indicated by an hatched arrow .Data present the mean of days 14+15. Displayed values are means ± SEM. (n=5-6). *p<0,05 NaCl vs TG; #p<0,05 CHOW NaCl vs HFHS NaCl; $p<0,05 HFHS NaCl vs HFHS TG.

On food choice, saline-infused animals clearly showed a strong preference for the palatable diet over chow, however, mice receiving TG consumed a similar amount of calories from both diets (Figure 1d, e, f), indicating that brain TG delivery abolished preference for palatable food with little effect on total caloric intake (chow+HFHS) (Figure 1g). Importantly, when animals were not given the choice between diet, central TG still reduced locomotor activity but did not alter normal chow intake, ruling out potential adverse responses to centrally delivered TG (Supplementary Figure 5).

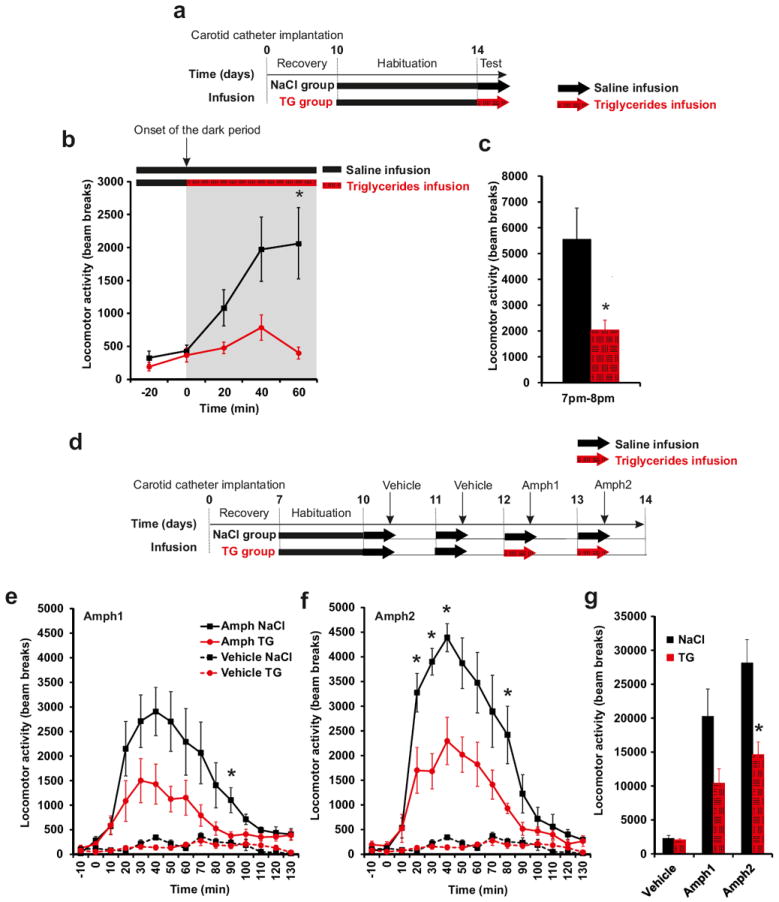

Central triglyceride delivery decreases spontaneous and amphetamine-induced locomotion

The sharp reduction in nocturnal locomotor activity prompted us to explore the effects of TG perfusion on the increase in spontaneous activity that normally occurs at the onset of the dark period. Animals received saline perfusion up until 20 min prior to the initiation of the dark cycle at which point one group was shifted to TG perfusion (Figure 2a). While lights off triggered a 400% increase in locomotion in the saline-infused control group, the group receiving TG remained at a level only slightly above diurnal level (Figure 2b, c). This result indicates that brain-specific TG delivery can act rapidly to alter behavior. Both spontaneous activity and preference for palatable food are regulated by the release of dopamine in striatal and limbic brain regions 17, 18, 44-46. We therefore reasoned that TG entering the brain may influence dopamine signaling and tested the ability of amphetamine to induce locomotion in animals receiving a short 6-hrs intra-carotid perfusion of TG (Figure 2d). Central TG delivery reduces amphetamine-induced locomotion by ~50% (Figure 2e, f), suggesting a potential role for nutritional TG in the regulation of dopamine signaling. Again, upon cessation of TG infusion, animals regained sensitivity to amphetamine (Supplementary Figure 6). In addition, we recapitulated these results using the selective dopamine D2 receptor (D2R) agonist quinpirole. At a dose (0.1 mg/kg) shown to acutely increase locomotion 47, central TG delivery decreased quinpirole-induced locomotion (Supplementary Figure 7).

Figure 2. Central triglycerides delivery rapidly alters spontaneous locomotor activity and decreases Amphetamine-induced locomotion.

Experimental procedure (a, d). Locomotor activity evolution (b) and cumulative activity (c) was monitored at the very beginning of the infusion at the onset of dark period (7pm-8pm) in control mice (black squares and bars) and TG infused mice (red circles and hatched red bars). Locomotor activity was recorded during 2h after an acute intraperitoneal injection of 3 mg/kg D-amphetamine or vehicle (saline solution)in control mice (black square) and TG infused mice (red circles) day 12 (e) and day 13 (f). Cumulative locomotor activity after vehicle or amphetamine injection in control mice (black bars) and TG infused mice (hatched red bars) (g). Mice were infused with NaCl or TG solution during 6h just before vehicle or D-amphetamine injection. Displayed values are means ± SEM. (n=5). *p<0,05 NaCl vs TG.

Evaluation of dopamine and dopamine metabolites 2-hr after amphetamine injection revealed that central TG delivery was associated with a modest increase in striatal dopamine turn-over (Supplementary Figure 8a-e). However, in the absence of acute amphetamine, 24-hrs TG perfusion was insufficient to alter dopamine turn over (Supplementary Figure 8f-i). Similarly, we found no significant changes in the levels of striatal D2R protein (Supplementary Figure 9) or enkephalin (a peptide enriched in D2R-expressing striatal neurons and involved in food-reward5, 48) (Supplementary Figure 10). Taken together these data suggest that TG may act within the striatum, downstream of DA receptor binding, to alter basal ganglia output.

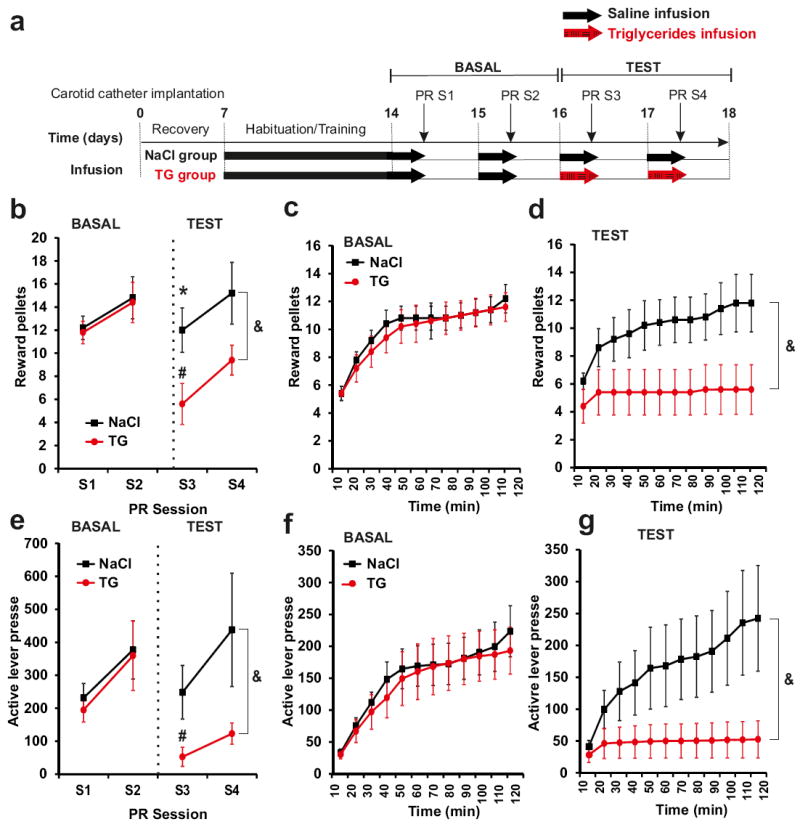

Central triglyceride delivery decreases food reward seeking

Palatability and hedonic impact are powerful determinants of food intake. Ingestion of food, particularly foods rich in sugar or fat, provides subjective pleasure and can be a source of comfort in response to depression or stress 4, 9, 11, 49, 50. The action of central TG delivery on food preference, nocturnal activity, and psychostimulant-induced locomotion suggested that brain lipid signaling may directly influence motivated behavior. We tested this hypothesis by first pre-training mice to lever press for high-sucrose food reward pellets and then following intra-carotid saline or TG infusion, assessing their performance on a progressive ratio (PR) task that measures the amount of effort an animal is willing to exert to obtain food rewards (Figure 3a).

Figure 3. Central triglycerides delivery specifically decreases motivational aspect of reward seeking.

Experimental procedure (a). Progressive ratio (PR) responding for sucrose pellet in control mice (black squares)and TG infused mice (red circle). During basal conditions both group were infused with saline solution. Numbers of rewards achieved (b) and active lever presses achieved (e) were recorded during 4 sessions of PR. Time course of number of rewards and active lever presses were recorded during the 1st (c, f) and 3rd PR session (d, g). Mice were infused with NaCl or TG solution during 6h just before session of PR. Displayed values are means ± SEM. (n=5). *p<0,05 NaCl vs TG; #p<0,05 TG S1 et S2 vs TG S3.Using repeated measure analysis we show an effect of group (NaCl vs TG) during TEST &p<0,001.

Mice received saline for the first 2 consecutive PR sessions (S1 and S2) and were then divided into two groups receiving either saline or TG for an additional two consecutive sessions (S3 and S4). While both groups demonstrated similar performance during S1 and S2 (basal saline infusion), 6-hrs TG delivery was sufficient to induce a significant decrease in lever presses and rewards received during S3 and S4 (Figure 3b-g). Importantly, there were no changes in the ratio of active versus inactive lever presses, suggesting that TG infusion does not impair discrimination learning or memory retrieval in this task (Supplementary Figure 11). These results indicate that changes in circulating levels of nutritional TG are sensed within the brain and are sufficient to suppress reward-seeking behavior in the absence of any changes in metabolic demand.

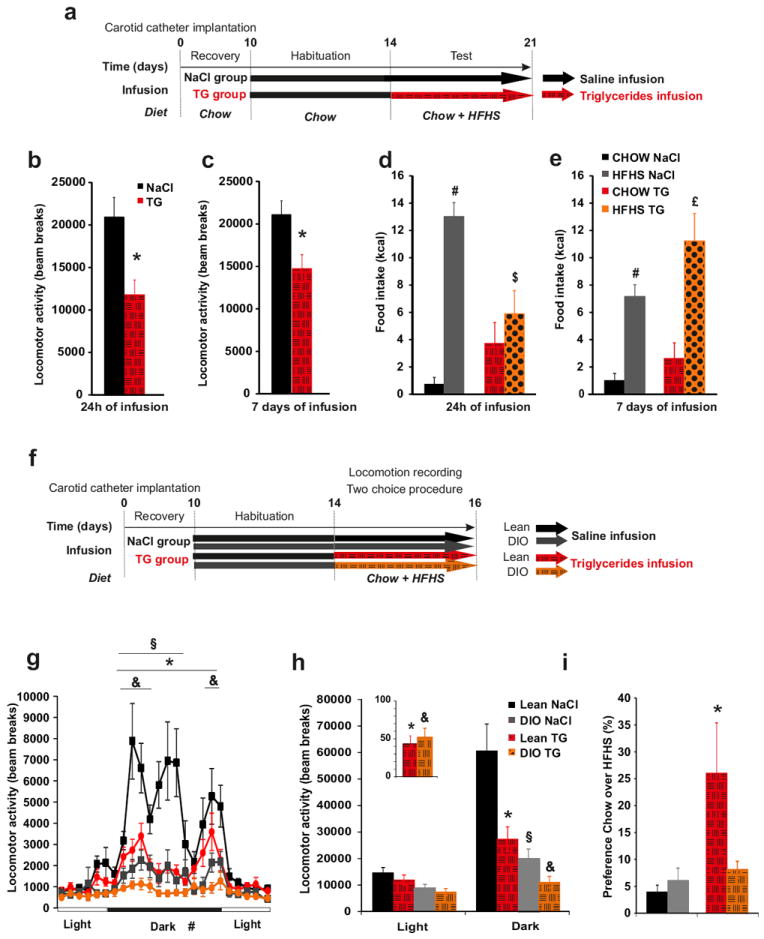

In conditions of chronic hypertriglyceridemia central TG delivery no longer affects feeding preference but still reduces locomotor activity

Our results suggest that an immediate surge in plasma TG after a meal would act in the brain to inhibit preference and desire for high-fat or high-sucrose foods and thereby homeostatically regulate feeding behavior. However, chronic hypertriglyceridemia and altered feeding behavior, particularly intense craving for highly palatable food, are symptoms commonly associated with obesity 16, 24. In order to reconcile these observations we compared the behavioral consequences of one versus seven days of brain TG delivery. Mice received either saline or TG infusion in the carotid artery and locomotor activity, food intake, and food choice were continuously monitored for the first 24-hrs and, again on the seventh day of infusion (Figure 4a). Importantly, even if animals had a slight increase in body weight due to HFHS diet exposure they were not obese. Results show that brain-specific TG infusion was equally effective in reducing locomotor activity on day 1 or day 7 (Figure 4b, c). However, while TG delivery suppressed preference for palatable food on day 1, by the seventh day of TG infusion mice displayed a normal preference, suggesting that adaptive mechanisms had occurred (Figure 4d, e). Importantly, over the course of infusion body weight remained unchanged (Supplementary Figure 12), arguing against non-specific effects of these procedures on animal health. Because obesity leads to chronically elevated TG, the action of centrally delivered TG was also evaluated in mice with diet-induced obesity (DIO 36.5g ± 0.99 vs lean 26g ±0.26g of body weight, p<0.05) using a protocol similar to that in Figure 1 (Figure 4f). In agreement with previous observations, 51 DIO mice exhibited reduced locomotor activity compared to lean counterparts under baseline conditions. Consistent with our hypothesis, central TG delivery in lean mice induces a decrease in activity to the level of saline-perfused DIO (Figure 4g, h) while TG perfusion in both lean and DIO mice similarly induced a ~50% decreased in locomotor activity (Figure 4g, h and insert). Central TG delivery also reduced amphetamine-induced locomotion by ~50% in both lean and DIO mice (Supplementary Figure 13). Finally, using the food choice procedure, central TG delivery increased the consumption of chow over HFHS food in lean mice as we had previously observed, but did not affect tropism for palatable food in DIO mice (Figure 4i).

Figure 4. Prolonged central triglycerides delivery results in desensitization of feeding but not locomotor activity.

Experimental procedure (a, f). Cumulative locomotor activity during dark period in control mice (black bars) and TG infused mice (hatched red bars) was recorded after 24h (b) or 7 days (c) infusion Cumulative food intake during dark period of chow (control mice: black bars; triglycerides infused mice: hatched red bars) and HFHS diet (control mice: grey bars; triglycerides infused mice: dotted orange bars) was recorded in a food choice procedure after 24h (d) or 7 days (e) of infusion. Daily variation of locomotor activity (g), cumulative locomotor activity (h) (insert represents the reduction of locomotor activity expressed in % of total activity during saline perfusion) and ratio between chow/HFHS kcal intake during a two choice procedure (i) in lean mice infused with NaCl (black squares and bars), in lean mice infused with TG (red circles and hatched red bars), in DIO mice infused with NaCl (grey square and bars)and in DIO mice infused with TG (orange circles and hatched orange bars).Data present the mean of days 14+15 (b, d, g, h) and days 19+20 (c, e). Displayed values are means ± SEM. (n=5-7). *p<0,05 NaCl vs TG; #p<0,05 CHOW NaCl vs HFHS NaCl; $p<0,05 HFHS NaCl vs HFHS TG; £p<0,05 CHOW TG vs HFHS TG; & p<0,05 NaCl-DIO vs TG-DIO; § p<0,05 DIO vs Lean.

NAc-specific Lpl knock down increases reward seeking and palatable food consumption

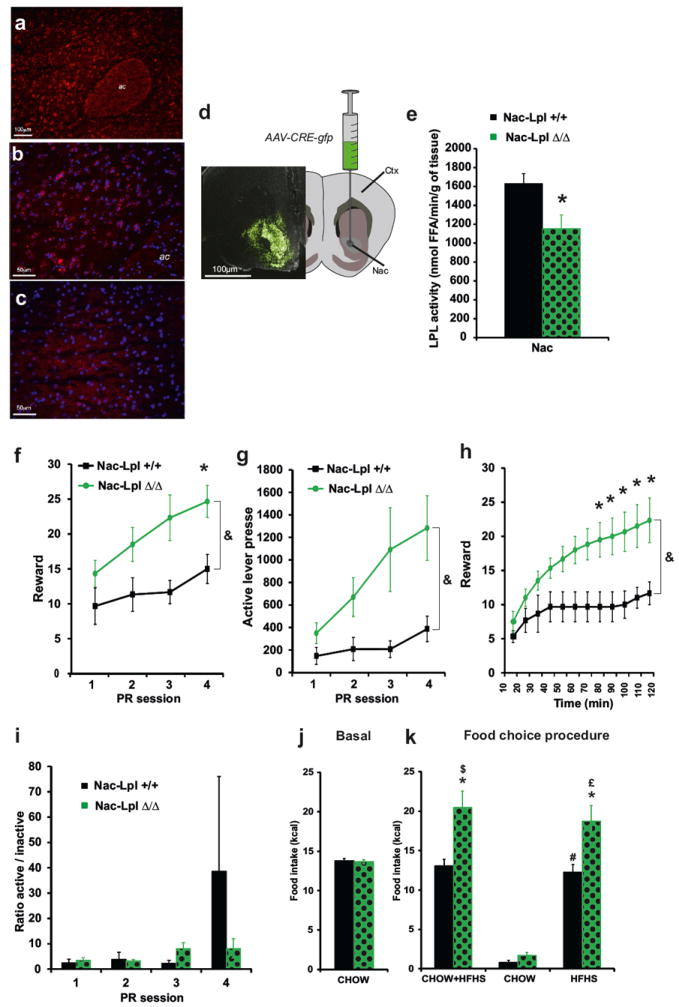

Our data using brain TG infusion suggests that TG-sensing neural circuits detect changes in circulating TG to alter behavior. The behavioral consequences suggest a role for mesolimbic circuits, but the molecular mechanisms of TG sensing remain obscure. In the hypothalamus, LpL-mediated TG hydrolysis plays an important role in TG sensing and, suggestively, this enzyme is also expressed at high levels in striatum 31, 35, 38, 40. We therefore hypothesized that LpL-mediated TG hydrolysis locally in the NAc acts as molecular relay for TG effects on reward seeking. Consistent with these findings, in situ hybridization confirmed the expression of Lpl mRNA in NAc neurons, (Figure 5a, b) with significantly lower expression levels across cortical regions (Figure 5c), highlighting the specificity of Lpl expression and supporting a functional role in NAc. LPL activity is also present in several brain structures including the hypothalamus, the hippocampus, the striatum and the cortex (Supplementary Figure 14a); and consistent with mRNA expression levels, LPL activity was higher in NAc than cortex. We next engaged in the selective knock down of LPL in the NAc by stereotactic injection of adeno-associated virus (AAV) expressing a chimera of Cre recombinase fused to GFP 43 (AAV-Cre:GFP) into the NAc of mice in which the first exon of Lpl is flanked by LoxP sites (Lpllox/lox), allowing for Cre mediated Lpl gene deletion 40,52 (see Figure 5d and supplementary Figure 14b, d). Following AAV-Cre:GFP injection into the NAc, LPL activity was decreased by ~30% in the NAc of Lpl lox/lox compared to control Lpl+/+ mice (referred as to NAc-LplΔ/Δ and NAc-Lpl+/+) (Figure 5e).

Figure 5. NAc-specific Lpl knock down increases motivational aspect of reward seeking.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization was performed for LPL mRNA (red) within NAc (a) revealing that the gene is expressed across multiple NAc neurons labeled with dapi (blue, b). No expression of LPL mRNA was observed in white matter tracks (anterior commissure, ac) or other brain regions, as reflected in the absence of LPL mRNA grains within the somatosensory cortex (c). Schematic and representative photo micrograph showing GFP expression after AAV-CRE-GFP virus injection in the NAc of Lpllox/lox mice (d). Schematic and representative photo micrograph showing GFP expression after AAV-CRE-GFP virus injection in the NAc of Lpl +/+ (NAc-Lpl +/+ black bars) and Lpl lox/lox mice (NAc-LplΔ/Δ,green dotted bars) after viral injection (e). Progressive ratio responding for sucrose pellets in control mice (black squares and bars) and in mice with a NAc-specific Lpl knock down (green circles and green dotted bars). Numbers of rewards (f), active lever presses (g) and ratio of active/inactive lever presses achieved (i) were recorded during 4 sessions of PR. Time course of rewards acquisition in within the 3rd PR session (h). Average chow intake was recorded at several time points during 2 months after NAc-specific AAV-Cre-GFP virus injection (j). Total cumulative food intake (chow+HFHS) and specific cumulative food intake of chow and HFHS diet was recorded in a 24h food choice procedure (k) in control mice (black bars) and mice with a NAc-specific Lpl knock down (green dotted bars). Displayed values are means ± SEM. (n=5-6 in each group). *p<0,05 NAc-Lpl+/+ vs NAc-LplΔ/Δ; $p<0,05 CHOW NAc-Lpl+/+ vs CHOW+HFHS NAc-Lpl+/+; #p<0,05 CHOW NAc-Lpl+/+ vs HFHS NAc-Lpl+/+; £p<0,05 CHOW NAc-LplΔ/Δ vs HFHS NAc-LplΔ/Δ. Using repeated measure analysis we show an effect of group (NAc-Lpl+/+ vs NAc-LplΔ/Δ) &p<0,001

NAc-LplΔ/Δ and NAc-Lpl+/+ mice were subjected to the operant task described above. NAc-specific knock down of LPL activity did not impact performance on a low fixed ratio task during pre-training (not shown). However on a PR task, NAc-LplΔ/Δ displayed an increase in both rewards received and lever presses compared to NAc-Lpl+/+ (see Figure 5f, g, h), with no effect on the ratio of active/inactive lever presses (Figure 5i). Thus while brain TG delivery decreased reward-seeking behavior, NAc-specific knockdown of the TG processing enzyme LPL had the opposite effect, increasing the drive to work for rewards (Figure 5). These data are consistent with a role for LPL-mediated TG signaling in the NAc in the regulation of food-seeking behavior.

Because intra-carotid delivery of TG abolished preference for HFHS diet (Figure 1), we predicted that NAc-specific reduction of LPL activity might produce the opposite outcome. Cumulative food intake was monitored in NAc-Lpl+/+ and NAc-LplΔ/Δ mice during ad libitum feeding with regular chow, and over a 24-hrs period during which regular chow and HFHS diet were available. NAc-specific inactivation of LPL had no impact on regular chow consumption (Figure 5j). However, when given the choice, NAc-LplΔ/Δ were hyperphagic and consumed ~30% more calorie-dense HFHS food compared to NAc-Lpl+/+ mice (Figure 5k). This result indicated that impairing the ability to hydrolyze TG specifically in the NAc resulted in increased incentive to consume palatable food. Taken together these results indicate that nutritional TG, detected directly at the level of the NAc,modulate the reinforcing properties of palatable food.

DISCUSSION

The last several decades have witnessed a pandemic expansion of pathologies related to high-fat and high-carbohydrate diets including obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia and cardiovascular diseases – collectively referred to as metabolic syndrome53, 54. Globally, there has been both an increased intake of energy-dense foods that are high in fat, sugar and salt, and a concomitant decrease in physical activity 53, 54. Despite the increasing prevalence and burden of the metabolic syndrome, effective and safe treatments to reverse the epidemic remain unavailable.

Although the presence of high-fat nutrient-rich food is essentially ubiquitous in developed countries, not all individuals with access to these foods over-consume them or become obese. It is thus likely that certain individuals become more vulnerable to the hedonic or reinforcing effects of calorie-rich food, and ultimately form eating habits that become disassociated from the homeostatic mechanisms that normally maintain energy balance 3. Understanding the early mechanisms underpinning the progressive loss in homeostatic control of energy balance is a key step toward a clinical breakthrough in the treatment of hyperphagia and obesity.

Hypothalamic and extra hypothalamic lipid sensing: different lipid species for a different purpose?

LCFA metabolism at the level of the hypothalamus has been shown to regulate neuronal activity, food intake, autonomic control of insulin release, and liver insulin-sensitivity 25-28, 55. But although TG and LCFAs are both circulating lipid species, the physiological entry into plasma differ drastically. Indeed, whereas TG-rich particles accumulate after a meal; LCFA are released by fasting-induced adipose lipolysis and are thus elevated during periods of food abstinence 24. In addition, while fatty-acid transporters promote the uptake of LCFA into various brain structures, TG must first be hydrolyzed by specific TG-hydrolyzing enzymes, the distribution of which will severely limit central availability of TG-derived signals. Hence, the central structures involved in the detection of peripheral lipid fluctuations as well as the nature of the adaptive behavioral and metabolic responses might radically differ depending on the lipid species and the physiological status (e.g., fasting, post-prandial, or obesity-associated hypertriglyceridemia).

Previous work on how circulating lipids affect the brain has focused chiefly on the effects of non-esterified fatty acids on brain metabolism and behavior. For instance, ICV injection of oleic acid was shown to alter hypothalamic lipid metabolism and result in decreased food intake 25. Furthermore, lipid metabolism in the hypothalamus has been repeatedly shown to be critical in mediating the central effects of LCFAs 25-28, 55, 56. However 48-hr intra-carotid TG delivery did not alter whole brain expression levels of key lipid-modifying or lipid-sensitive enzymes (Supplementary Figure 15). Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids have anti-inflammatory properties which could contribute to the central effects of TG 57. However, intra-carotid infusion of a TG emulsion enriched in the omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) recapitulated the behavioral effects on food choice and locomotor activity, suggesting that the pro- or anti-inflammatory nature of omega-3 vs omega-6 lipids were not fundamentally involved in the behavioral phenomena we observed (Supplementary Figure 16).

We therefore propose that the central availability of TG and LCFA differ, that these lipid species influence neural circuit function through separate mechanisms, and that they have opposing effects on food seeking behavior. While LCFAs may principally act in the hypothalamus and function to increase food intake in response to a fast; TG sensing may depend on local hydrolysis by LPL in limbic structures where they decrease the incentive or motivational properties of food. Potential mechanisms could involve lipid-mediated activation of membrane receptors 58, cellular energy-related pathways 28, 55, endoplasmic-reticulum stress 59, eicosanoids-dependent inflammatory processes 60, endocannabinoid signaling pathways 61, 62, andlipid-activated transcriptional adaptations 63.

Central detection of triglyceride and the modulation of reward

Our results provide the first experimental evidence that TG can directly target mesolimbic structures to modulate reward seeking. We have established a method to evaluate the behavioral & metabolic consequences of brain lipid sensing by infusing TG via the natural route of access to the brain through the carotid artery 1) in the direction of the brain, 2) at a rate & concentration that closely recapitulate the post-prandial increase in TG, but 3) without affecting systemic LCFA or TG concentrations. Such TG infusion leads to a decrease in nocturnal and amphetamine-induced locomotor activity in both normal (lean) and diet-induced obese (DIO) mice, but only abolishes preference for palatable HFHS food only in lean mice. In addition, brain TG delivery decreases the overall motivation to work for reward as assessed by a PR task. We have also begun to define the neural circuitry and molecular mechanisms by which TG influence neural activity and behavior. Indeed, in contrast to the effects of TG infusion, deletion of the gene encoding the TG-hydrolyzing enzyme LPL specifically in the NAc leads to sensitization to the reinforcing properties of palatable food as revealed by the PR operant task and hyperphagia during a HFHS food preference task.

Plasma TG accumulate after a meal and gradually return to basal levels due to the contribution of both insulin-mediated TG storage and lipid oxidation in tissue 24. However, plasma TG is chronically elevated in obesity. During prolonged TG perfusion, designed to mimic chronic hypertriglyceridemia, we found that adaptive desensitization processes occur such that TG infusion no longer abolishes HFHS preference but continues to suppress locomotor activity (Figure 4). Consistent with this, using DIO mice to physiologically model chronic hypertriglyceridemia, central TG delivery still reduced locomotor activity but no longer was effective in modulating food tropism (Figure 4f-i).

Together, these data suggest a model whereby post-prandial increases in plasma TG are hydrolyzed locally in the striatum where they alter striatolimbic circuitry to effect a reduction in locomotor activity and homeostatically reduce the incentive properties of calorie-rich HFHS foods. However, in the face of sustained elevations in plasma TG, achieved either by intra-carotid perfusion or diet-induced obesity, the homeostatic mechanisms that normally serve to reduce the hedonic impact of HFHS foods break down. This model predicts a positive feedback loop whereby chronically high plasma TG, such as occur in obesity, cripple the homeostatic mechanisms that curb food intake resulting in uncontrolled caloric consumption and reduced physical activity. Such a mechanism would serve to drive body weight gain while making weight loss more difficult.

Further studies will be required to uncover the cellular basis of LPL-mediated mesolimibic TG sensing, the downstream molecular events that occur following TG hydrolysis, and how these events alter the activity of striatolimbic neural circuits. Finally, our findings suggest new avenues to therapeutic intervention in obesity, obesity-associated pathologies, and perhaps other disorders of compulsive reward seeking, such as drug addiction, which will require testing in disease models.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by young investigator ATIP grant from the Centre National la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS),an grant from the Région Île-de-France, from the University Paris Diderot-Paris 7, from the “Agence Nationale de la Recherche” ANR-09-BLAN-0267-02 and ANR 11 BSV1 021 01. C. C. received a PhD fellowship from the CNRS and a research grant from the Société Francophone du Diabète-Roche (SFD).TSH was supported by NIH grant DA026504 and a scientist exchange award from the University of Paris Diderot-Paris VII. We express our gratitude to Aundrea Rainwater for help establishing the infusion technique and operant schedule and to Dr Susanna Hofmann for critical review on the manuscript. We acknowledge the technical platform Functional & Physiological Exploration Platform (FPE) and the platform “Bioprofiler” of the Unit “Biologie Fonctionnelle et Adaptative”, (Univ Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cité, BFA, UMR 8251 CNRS, F-75205 Paris, France) for metabolic and behavioral analysis and for the provision of high-performance liquid chromatography data. We also acknowledge the animal core facility “Buffon” of the University Paris Diderot Paris 7/Institut Jacques Monod, Paris for animal husbandry and breeding together with Dr Serban Morosan for its precious help regarding DIO mice.

Footnotes

Supplementary information is available at Molecular Psychiatry’s website

Supplemental data includes supplemental results, supplemental experimental procedures, supplemental references, and 16 supplementary Figures.

The authors declared that no conflict of interest exist

References

- 1.Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte D, Jr, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG. Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature. 2000;404(6778):661–671. doi: 10.1038/35007534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morton GJ, Cummings DE, Baskin DG, Barsh GS, Schwartz MW. Central nervous system control of food intake and body weight. Nature. 2006;443(7109):289–295. doi: 10.1038/nature05026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berthoud HR. Mind versus metabolism in the control of food intake and energy balance. Physiol Behav. 2004;81(5):781–793. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dallman MF, Pecoraro N, Akana SF, La Fleur SE, Gomez F, Houshyar H, et al. Chronic stress and obesity: a new view of “comfort food”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(20):11696–11701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934666100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelley AE, Baldo BA, Pratt WE, Will MJ. Corticostriatal-hypothalamic circuitry and food motivation: integration of energy, action and reward. Physiol Behav. 2005;86(5):773–795. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelley AE, Baldo BA, Pratt WE. A proposed hypothalamic-thalamic-striatal axis for the integration of energy balance, arousal, and food reward. J Comp Neurol. 2005;493(1):72–85. doi: 10.1002/cne.20769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiLeone RJ, Taylor JR, Picciotto MR. The drive to eat: comparisons and distinctions between mechanisms of food reward and drug addiction. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(10):1330–1335. doi: 10.1038/nn.3202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Tomasi D, Baler R. Food and drug reward: overlapping circuits in human obesity and addiction. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2012;11:1–24. doi: 10.1007/7854_2011_169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mela DJ. Eating for pleasure or just wanting to eat? Reconsidering sensory hedonic responses as a driver of obesity. Appetite. 2006;47(1):10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunstad J, Paul RH, Cohen RA, Tate DF, Spitznagel MB, Gordon E. Elevated body mass index is associated with executive dysfunction in otherwise healthy adults. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48(1):57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stice E, Spoor S, Bohon C, Veldhuizen MG, Small DM. Relation of reward from food intake and anticipated food intake to obesity: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117(4):924–935. doi: 10.1037/a0013600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vucetic Z, Reyes TM. Central dopaminergic circuitry controlling food intake and reward: implications for the regulation of obesity. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2010;2(5):577–593. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Logan J, Pappas NR, Wong CT, Zhu W, et al. Brain dopamine and obesity. Lancet. 2001;357(9253):354–357. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03643-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson PM, Kenny PJ. Dopamine D2 receptors in addiction-like reward dysfunction and compulsive eating in obese rats. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(5):635–641. doi: 10.1038/nn.2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michaelides M, Thanos PK, Volkow ND, Wang GJ. Dopamine-related frontostriatal abnormalities in obesity and binge-eating disorder: emerging evidence for developmental psychopathology. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2012;24(3):211–218. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2012.679918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stice E, Spoor S, Bohon C, Small DM. Relation between obesity and blunted striatal response to food is moderated by TaqIA A1 allele. Science. 2008;322(5900):449–452. doi: 10.1126/science.1161550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geiger BM, Behr GG, Frank LE, Caldera-Siu AD, Beinfeld MC, Kokkotou EG, et al. Evidence for defective mesolimbic dopamine exocytosis in obesity-prone rats. FASEB J. 2008;22(8):2740–2746. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-110759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis JF, Tracy AL, Schurdak JD, Tschop MH, Lipton JW, Clegg DJ, et al. Exposure to elevated levels of dietary fat attenuates psychostimulant reward and mesolimbic dopamine turnover in the rat. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122(6):1257–1263. doi: 10.1037/a0013111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin LE, Holsen LM, Chambers RJ, Bruce AS, Brooks WM, Zarcone JR, et al. Neural mechanisms associated with food motivation in obese and healthy weight adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(2):254–260. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothemund Y, Preuschhof C, Bohner G, Bauknecht HC, Klingebiel R, Flor H, et al. Differential activation of the dorsal striatum by high-calorie visual food stimuli in obese individuals. Neuroimage. 2007;37(2):410–421. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoeckel LE, Weller RE, Cook EW, 3rd, Twieg DB, Knowlton RC, Cox JE. Widespread reward-system activation in obese women in response to pictures of high-calorie foods. Neuroimage. 2008;41(2):636–647. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis JF, Tracy AL, Schurdak JD, Tschop MH, Lipton JW, Clegg DJ, et al. Exposure to elevated levels of dietary fat attenuates psychostimulant reward and mesolimbic dopamine turnover in the rat. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122(6):1257–1263. doi: 10.1037/a0013111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farr SA, Yamada KA, Butterfield DA, Abdul HM, Xu L, Miller NE, et al. Obesity and hypertriglyceridemia produce cognitive impairment. Endocrinology. 2008;149(5):2628–2636. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruge T, Hodson L, Cheeseman J, Dennis AL, Fielding BA, Humphreys SM, et al. Fasted to fed trafficking of Fatty acids in human adipose tissue reveals a novel regulatory step for enhanced fat storage. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(5):1781–1788. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Obici S, Feng Z, Morgan K, Stein D, Karkanias G, Rossetti L. Central administration of oleic acid inhibits glucose production and food intake. Diabetes. 2002;51(2):271–275. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lam TK, Pocai A, Gutierrez-Juarez R, Obici S, Bryan J, Aguilar-Bryan L, et al. Hypothalamic sensing of circulating fatty acids is required for glucose homeostasis. Nat Med. 2005;11(3):320–327. doi: 10.1038/nm1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lam TK, Schwartz GJ, Rossetti L. Hypothalamic sensing of fatty acids. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(5):579–584. doi: 10.1038/nn1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez M, Tovar S, Vazquez MJ, Nogueiras R, Senaris R, Dieguez C. Sensing the fat: fatty acid metabolism in the hypothalamus and the melanocortin system. Peptides. 2005;26(10):1753–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Migrenne S, Cruciani-Guglielmacci C, Kang L, Wang R, Rouch C, Lefevre AL, et al. Fatty Acid signaling in the hypothalamus and the neural control of insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2006;55(Suppl 2):S139–144. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blouet C, Schwartz GJ. Hypothalamic nutrient sensing in the control of energy homeostasis. Behav Brain Res. 2010;209(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H, Eckel RH. Lipoprotein lipase in the brain and nervous system. Annu Rev Nutr. 2012;32:147–160. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071811-150703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H, Eckel RH. Lipoprotein lipase: from gene to obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297(2):E271–288. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90920.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ronnett GV, Kleman AM, Kim EK, Landree LE, Tu Y. Fatty acid metabolism, the central nervous system, and feeding. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(Suppl 5):201S–207S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ronnett GV, Kim EK, Landree LE, Tu Y. Fatty acid metabolism as a target for obesity treatment. Physiol Behav. 2005;85(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paradis E, Clavel S, Julien P, Murthy MR, de Bilbao F, Arsenijevic D, et al. Lipoprotein lipase and endothelial lipase expression in mouse brain: regional distribution and selective induction following kainic acid-induced lesion and focal cerebral ischemia. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;15(2):312–325. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim EK, Miller I, Landree LE, Borisy-Rudin FF, Brown P, Tihan T, et al. Expression of FAS within hypothalamic neurons: a model for decreased food intake after C75 treatment. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;283(5):E867–879. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00178.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rapoport SI. In vivo fatty acid incorporation into brain phosholipids in relation to plasma availability, signal transduction and membrane remodeling. J Mol Neurosci. 2001;16(2-3):243–261. doi: 10.1385/JMN:16:2-3:243. discussion 279-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eckel RH, Robbins RJ. Lipoprotein lipase is produced, regulated, and functional in rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81(23):7604–7607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.23.7604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ben-Zeev O, Doolittle MH, Singh N, Chang CH, Schotz MC. Synthesis and regulation of lipoprotein lipase in the hippocampus. J Lipid Res. 1990;31(7):1307–1313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang H, Astarita G, Taussig MD, Bharadwaj KG, DiPatrizio NV, Nave KA, et al. Deficiency of lipoprotein lipase in neurons modifies the regulation of energy balance and leads to obesity. Cell Metab. 2011;13(1):105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karatayev O, Gaysinskaya V, Chang GQ, Leibowitz SF. Circulating triglycerides after a high-fat meal: predictor of increased caloric intake, orexigenic peptide expression, and dietary obesity. Brain Res. 2009;1298:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cruciani-Guglielmacci C, Hervalet A, Douared L, Sanders NM, Levin BE, Ktorza A, et al. Beta oxidation in the brain is required for the effects of non-esterified fatty acids on glucose-induced insulin secretion in rats. Diabetologia. 2004;47(11):2032–2038. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1569-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu Q, Palmiter RD. GABAergic signaling by AgRP neurons prevents anorexia via a melanocortin-independent mechanism. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.10.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palmiter RD. Is dopamine a physiologically relevant mediator of feeding behavior? Trends Neurosci. 2007;30(8):375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palmiter RD. Dopamine signaling in the dorsal striatum is essential for motivated behaviors: lessons from dopamine-deficient mice. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1129:35–46. doi: 10.1196/annals.1417.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Geiger BM, Haburcak M, Avena NM, Moyer MC, Hoebel BG, Pothos EN. Deficits of mesolimbic dopamine neurotransmission in rat dietary obesity. Neuroscience. 2009;159(4):1193–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eilam D, Szechtman H. Biphasic effect of D-2 agonist quinpirole on locomotion and movements. European journal of pharmacology. 1989;161(2-3):151–157. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90837-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kelley AE, Bakshi VP, Haber SN, Steininger TL, Will MJ, Zhang M. Opioid modulation of taste hedonics within the ventral striatum. Physiol Behav. 2002;76(3):365–377. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00751-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wise RA. Role of brain dopamine in food reward and reinforcement. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361(1471):1149–1158. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oliveira-Maia AJ, Roberts CD, Simon SA, Nicolelis MA. Gustatory and reward brain circuits in the control of food intake. Advances and technical standards in neurosurgery. 2011;36:31–59. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0179-7_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bjursell M, Gerdin AK, Lelliott CJ, Egecioglu E, Elmgren A, Tornell J, et al. Acutely reduced locomotor activity is a major contributor to Western diet-induced obesity in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294(2):E251–260. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00401.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Augustus A, Yagyu H, Haemmerle G, Bensadoun A, Vikramadithyan RK, Park SY, et al. Cardiac-specific knock-out of lipoprotein lipase alters plasma lipoprotein triglyceride metabolism and cardiac gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(24):25050–25057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401028200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365(9468):1415–1428. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reaven GM. The metabolic syndrome: is this diagnosis necessary? The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2006;83(6):1237–1247. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lopez M, Saha AK, Dieguez C, Vidal-Puig A. The AMPK-Malonyl-CoA-CPT1 Axis in the Control of Hypothalamic Neuronal Function-Reply. Cell Metab. 2008;8(3):176. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yue JT, Lam TK. Lipid sensing and insulin resistance in the brain. Cell Metab. 2012;15(5):646–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cintra DE, Ropelle ER, Moraes JC, Pauli JR, Morari J, Souza CT, et al. Unsaturated fatty acids revert diet-induced hypothalamic inflammation in obesity. PloS one. 2012;7(1):e30571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abumrad NA, Ajmal M, Pothakos K, Robinson JK. CD36 expression and brain function: does CD36 deficiency impact learning ability? Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2005;77(1-4):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang X, Zhang G, Zhang H, Karin M, Bai H, Cai D. Hypothalamic IKKbeta/NF-kappaB and ER stress link overnutrition to energy imbalance and obesity. Cell. 2008;135(1):61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rapoport SI, Chang MC, Spector AA. Delivery and turnover of plasma-derived essential PUFAs in mammalian brain. J Lipid Res. 2001;42(5):678–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lafourcade M, Larrieu T, Mato S, Duffaud A, Sepers M, Matias I, et al. Nutritional omega-3 deficiency abolishes endocannabinoid-mediated neuronal functions. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(3):345–350. doi: 10.1038/nn.2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Solinas M, Goldberg SR, Piomelli D. The endocannabinoid system in brain reward processes. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154(2):369–383. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aleshin S, Strokin M, Sergeeva M, Reiser G. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)beta/delta, a possible nexus of PPARalpha- and PPARgamma-dependent molecular pathways in neurodegenerative diseases: Review and novel hypotheses. Neurochemistry international. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.