Abstract

Photosynthetic microbial mats are complex, stratified ecosystems in which high rates of primary production create a demand for nitrogen, met partially by N2 fixation. Dinitrogenase reductase (nifH) genes and transcripts from Cyanobacteria and heterotrophic bacteria (for example, Deltaproteobacteria) were detected in these mats, yet their contribution to N2 fixation is poorly understood. We used a combined approach of manipulation experiments with inhibitors, nifH sequencing and single-cell isotope analysis to investigate the active diazotrophic community in intertidal microbial mats at Laguna Ojo de Liebre near Guerrero Negro, Mexico. Acetylene reduction assays with specific metabolic inhibitors suggested that both sulfate reducers and members of the Cyanobacteria contributed to N2 fixation, whereas 15N2 tracer experiments at the bulk level only supported a contribution of Cyanobacteria. Cyanobacterial and nifH Cluster III (including deltaproteobacterial sulfate reducers) sequences dominated the nifH gene pool, whereas the nifH transcript pool was dominated by sequences related to Lyngbya spp. Single-cell isotope analysis of 15N2-incubated mat samples via high-resolution secondary ion mass spectrometry (NanoSIMS) revealed that Cyanobacteria were enriched in 15N, with the highest enrichment being detected in Lyngbya spp. filaments (on average 4.4 at% 15N), whereas the Deltaproteobacteria (identified by CARD-FISH) were not significantly enriched. We investigated the potential dilution effect from CARD-FISH on the isotopic composition and concluded that the dilution bias was not substantial enough to influence our conclusions. Our combined data provide evidence that members of the Cyanobacteria, especially Lyngbya spp., actively contributed to N2 fixation in the intertidal mats, whereas support for significant N2 fixation activity of the targeted deltaproteobacterial sulfate reducers could not be found.

Introduction

In photosynthetic microbial mats high CO2 fixation activity often creates a great demand for nitrogen (N), which is partially met by high rates of N2 fixation (Bebout et al., 1994; Herbert, 1999). It was hypothesized that microbial mat development is dependent on the activity of N2-fixing microorganisms (diazotrophs) (Bergman et al., 1997). Microbial mats inhabiting the intertidal zone from Laguna Ojo de Liebre (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2) close to Guerrero Negro, Baja California Sur, Mexico, experience frequent alternating periods of desiccation (and thereby aeration) and tidal flooding (Omoregie et al., 2004b; Rothrock and Garcia-Pichel, 2005) and are subject to frequent physical disruption. This environment leads to a ‘pioneering stage' of habitat colonization, where N2 fixation is an important process, providing a source of N for mat growth (Bebout et al., 1994).

Although N2 fixation has previously been investigated in the intertidal mats from Laguna Ojo de Liebre (Bebout et al., 1993; Omoregie et al., 2004a, 2004b), the identity of the active diazotrophs remains elusive. Historically, Cyanobacteria were believed to be responsible for N2 fixation in microbial mats given their visual dominance and cultivation without an exogenous N source (Stal and Krumbein, 1981; Stal and Bergman, 1990; Paerl et al., 1991). This was further supported by biogeochemical assays using an inhibitor of oxygenic photosynthesis (3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea (DCMU)) (Stal et al., 1984; Bebout et al., 1993). However, molecular methods indicated that additional microorganisms (such as heterotrophic bacteria) present in microbial mats have the genetic potential for N2 fixation and may play an important role in microbial mat N2 fixation (Zehr et al., 1995; Steppe et al., 1996). In particular, sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) were hypothesized to contribute to N2 fixation in microbial mats (Steppe and Paerl, 2002). Indeed, earlier studies of the Laguna Ojo de Liebre intertidal mats, combining biogeochemical and molecular assays, were unable to detect nifH genes or transcripts from the visually dominating cyanobacterium Lyngbya spp. (Omoregie et al., 2004a, 2004b), despite the fact that several Lyngbya spp. possess the capability to fix N2 in culture (for example, Paerl et al., 1991; Bebout et al., 1993). Instead, nifH sequences from Cluster III, including SRB that belong to the Deltaproteobacteria, dominated these nifH gene libraries and were also found in the transcript library (Omoregie et al., 2004a, 2004b). In addition to these deltaproteobacterial sulfate-reducing diazotrophs, Cluster III also contains sequences from spirochetes, methanogens, acetogens, green sulfur bacteria and Clostridia (Zehr et al., 2003). Comparative investigation of available nifH sequences indicates that Cluster III contains the greatest diversity of all nifH lineages and that its diversity is still not fully understood (Gaby and Buckley, 2011).

The presence and/or transcription of the nifH gene does not necessarily mean that an organism actively fixes N2 in the environment since the nitrogenase enzyme activity can be regulated on multiple levels ranging from transcription (Chen et al., 1998) to post-translational protein modification (Kim et al., 1999). As such, identification of active diazotrophs requires investigation on the functional level, for example through stable isotope probing (SIP) with 15N2. The incorporation of 15N into biomass can be directly imaged with secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS; Cliff et al., 2002; Lechene et al., 2006; Popa et al., 2007), and especially the NanoSIMS 50 has been used recently to investigate diazotrophic communities at the single-cell level across diverse environments (for example, Dekas et al., 2009; Halm et al., 2009; Foster et al., 2011; Ploug et al., 2011; Woebken et al., 2012).

We sought to identify the diazotrophic community in intertidal mats at Laguna Ojo de Liebre, Mexico, and ascertain using a 15N2-SIP single-cell approach the actively N2-fixing populations. We applied a combination of inhibitor amendment experiments, nifH gene and transcript sequencing, and 15N2 incubations followed by single-cell isotope measurements. As in previous studies, inhibitor experiments coupled to acetylene reduction assays (ARAs) suggested that Cyanobacteria and SRB both have a major role in N2 fixation. However, further investigations through inhibitor addition experiments combined with 15N2-incubations, molecular and NanoSIMS analyses provided strong evidence that members of the Cyanobacteria (especially Lyngyba spp.) were the most active diazotrophs in the investigated mats.

Materials and methods

Mats with a phototrophic layer dominated by Lyngbya spp. (in terms of biomass, as assessed by light microscopy) were sampled from the intertidal zone at Laguna Ojo de Liebre, Baja California, Mexico (27.758 N (Lat.) and −113.986 W (Long.)) on 15 September 2010 (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2) during low tide. The N2 fixation activity of two replicate mat pieces of ca. 20 cm × 30 cm was investigated over a diel cycle at a nearby field laboratory (outdoor setup in Guerrero Negro, Baja California, performed in acrylic aquaria as described below) from 15 to 16 September 2010. Other mat pieces were transported to the NASA Ames Research Center, CA, USA, on 16 September 2010 for additional diel cycle studies including inhibition experiments, stable isotope incubations as well as nucleic acid-based investigations. For experiments at NASA Ames, mats were placed in acrylic aquaria transparent to ultraviolet radiation and covered with in situ water for 2 days before the beginning of the diel study (starting at 1200 hours and ending at 1500 hours the next day). To ensure full photosynthetic activity in the mats during the N2 fixation experiments, resumption of photosynthetic activity after rewetting was investigated by pulse amplitude modulation fluorescence. The quantum yield of PSII (ΦPSII) for a light-adapted sample was calculated based on FS (steady-state fluorescence under actinic light) and FM′ (maximum fluorescence under actinic light) measurements using the following equation: ΦPSII=(FM′−FS)/FM′. Rehydrated mats exhibited maximal photosynthetic activity (ΦPSII=0.30–0.40) within 4 h of wetting in congruence with earlier studies (Fleming et al., 2007); thus, diel cycle studies were conducted with fully active mats. Diel cycle studies were carried out under natural solar irradiance, and the water temperature was kept constant at ∼18 °C.

Nitrogenase activity was measured with ARAs and 15N2 incubations as previously described (Bebout et al., 1993; Woebken et al., 2012). For more details see Supplementary Information. Bulk sample 15N/14N isotope ratios were determined by isotope-ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS; ANCA-IRMS, PDZE Europa Limited, Crewe, England) at the University of California, Berkeley, corrected relative to National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) standards and are expressed as 15N/(14N+15N) isotope fractions, given in at% (means±s.e.).

All inhibition experiments were conducted at the NASA Ames Research Center. For photosynthesis inhibition experiments, DCMU was added to intact mat slabs before sunrise on the first day of the diel cycle study with a final concentration of 20 μM to ensure complete inhibition of photosystem II (PSII) (Oremland and Capone, 1988). For ARAs or 15N2 incubation experiments, mat cores were subsampled from these mat slabs and incubated as described in Supplementary Information, but with in situ water containing DCMU. Mat cores from mat slabs without DCMU treatment served as controls and were incubated in seawater without DCMU. For sulfate reduction inhibition experiments, sodium molybdate (Na2MoO4, a structural analog of sulfate) was added to intact mat slabs submerged in in situ seawater or artificial seawater in the early morning of the first day of the diel cycle study to achieve a final concentration of 30 mM (Oremland and Capone, 1988). Mat slabs incubated in in situ seawater or artificial seawater without molybdate served as controls. Two diel experiments were conducted: (A) mat samples in in situ seawater (control) versus mat samples in molybdate-amended seawater; and (B) mat samples in artificial seawater containing 23 mM sulfate (control) versus mat samples in artificial seawater without sulfate and with added molybdate. Incubations for ARA or 15N2 experiments were conducted as described in Supplementary Information.

All diel cycle experiments were accompanied by mat sampling for molecular analysis. At multiple time points during a diel experiment, four mat cores of 1 cm diameter were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further processing. DNA and RNA extractions were conducted as previously described (Woebken et al., 2012) and are further described in Supplementary Information. As N2 fixation was observed only during the night, all sequence data were derived from night-time samples.

454 pyrotag amplicon libraries (V6–V8 region) and clone libraries for Sanger sequencing of 16S rRNA genes/transcripts from two biological replicate mats, as well as clone libraries of the nifH genes/transcripts, were constructed and analyzed as previsously described (Woebken et al., 2012). Detailed information about the construction and analysis of these libraries can also be found in Supplementary Information. 16S rRNA 454 pyrotag sequencing resulted in 20 616 and 15 524 reads from both DNA templates and 20 138 and 22 246 reads from both cDNA templates (Supplementary Table S1). 16S rRNA Sanger sequencing resulted in 520 sequences from DNA samples (D3=256 and D5=264 sequences) and 316 sequences from cDNA samples (C3=150 and C5=166 sequences). Regarding nifH sequences, 313 sequences were retrieved from DNA, 522 sequences from cDNA and 181 from cDNA of the molybdate inhibition experiment. 16S rRNA and 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained in this study are deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KJ997979–KJ998814. Sequences of nifH genes and transcripts are deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KM212180–KM212266.

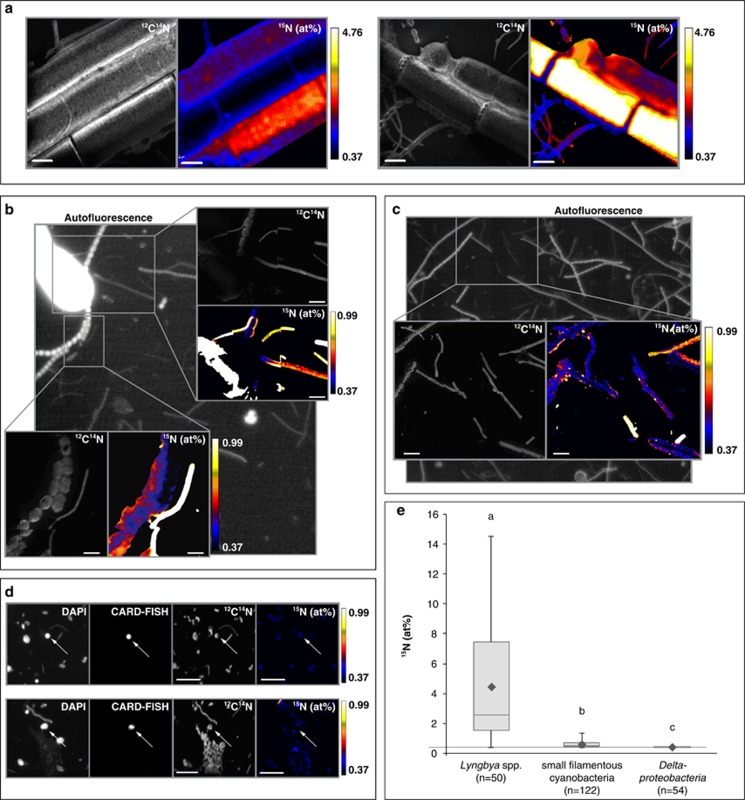

Single-cell NanoSIMS analyses were performed to identify active diazotrophs. The upper 2 mm of paraformaldehyde-fixed mat samples from 15N2 incubation experiments and negative control mat cores were prepared on 5 mm × 5 mm silicon wafer pieces (Ted Pella, Redding, CA, USA) for NanoSIMS analysis as previously described (Woebken et al., 2012). Filamentous cyanobacteria (Lyngbya spp.-related and small filamentous cyanobacteria) were identified based on their red autofluorescence when illuminated with green light by epifluorescence microscopy (excitation: BP 546/12, beam splitter: FT 560, emission: BP 607/80) and based on their morphology, as imaged by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; FEI Inspect F, FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA). Deltaproteobacteria were stained by catalyzed reporter deposition-fluorescence in situ hybridization (CARD-FISH) as previously described (Pernthaler et al., 2002; Woebken et al., 2012) using probes DELTA495 a-c (Loy et al., 2002; Lücker et al., 2007). Stained cells were identified and localized by epifluorescence microscopy. All targeted cells were localized and imaged by reflected light microscopy and SEM to ensure that the target cells were free of overlying cells or other material so that 15N/14N ratios could unambiguously be attributed to the target cells. SIMS analysis was performed at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) using a NanoSIMS 50 (Cameca, Gennevilliers Cedex, France) as previously described (Woebken et al., 2012). Isotopic compositions are expressed as the abundance of the tracer relative to the total tracer element (aN=15N/(14N+15N)) in at%. Reported data refer to the arithmetic mean of all measurements per cell type ±s.e. Detailed methods are provided in Supplementary Information.

Data retrieved in the ARAs, IRMS data of vertical sections and inhibition experiments as well as NanoSIMS data were analyzed for significant differences using Student's t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) with an alpha error of 0.05 and the Tukey–Kramer honestly significant difference as a multiple means comparison test (JMP Version 7, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Normal distribution was tested with the Shapiro–Wilk W-test, and in cases where the data did not meet the standard of homogeneity of variance, the Welch ANOVA was used to confirm the initial result. As 15N enrichment levels were very low in Deltaproteobacteria measured by NanoSIMS, the natural abundance values for Deltaproteobacteria were used to test for significant enrichment based on a 95% confidence interval.

Results

Bulk-level N2 fixation analysis

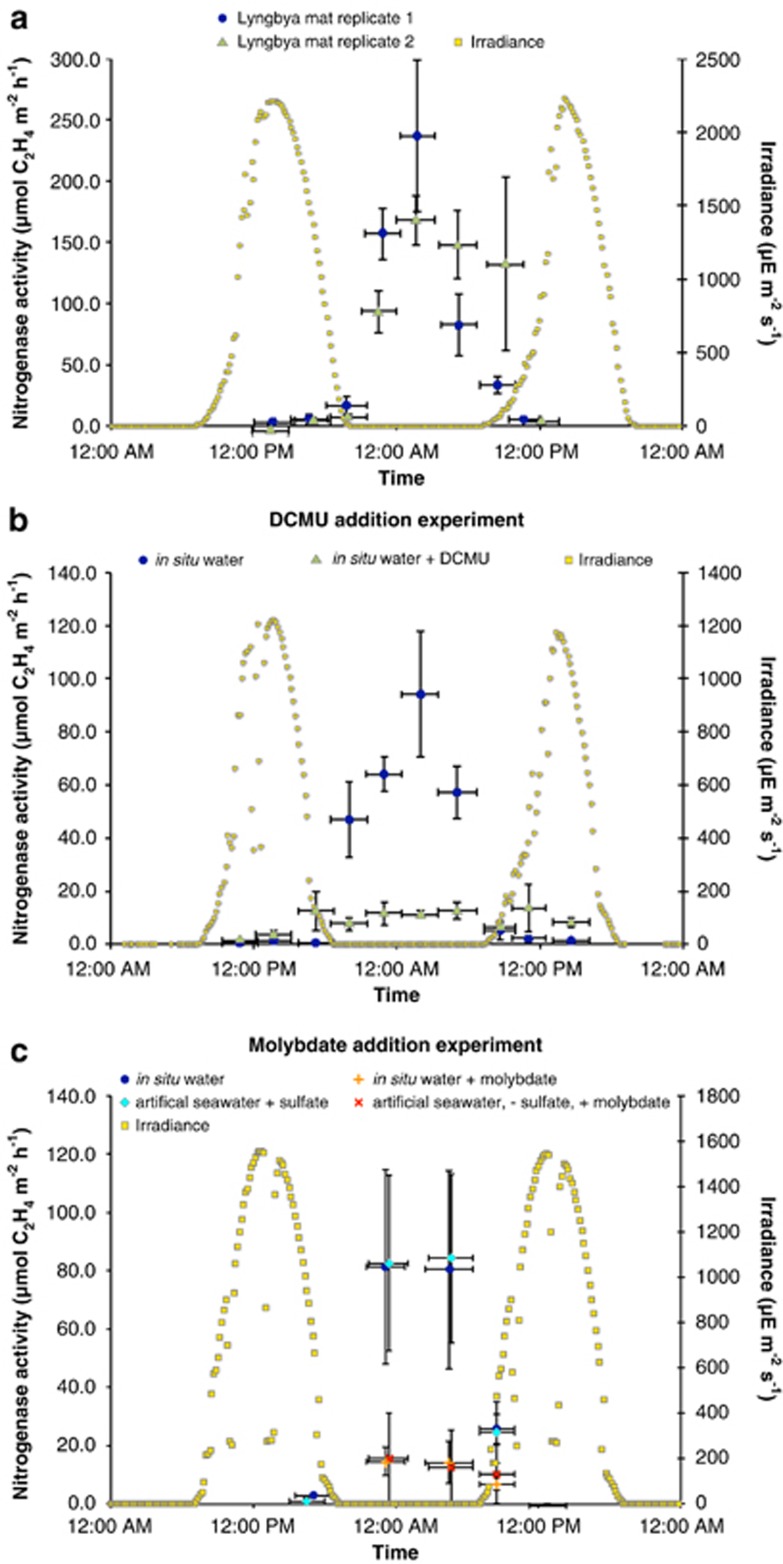

Nitrogenase activities in ARAs were significantly higher during the night than during the day-time (average± s.d. 131±67 vs 5±7 μmol C2H4 m−2 h−1, P<0.0001, Figure 1a) and well within the range of previously reported rates (Bebout et al., 1994; Omoregie et al., 2004b). The potential contribution of oxygenic phototrophs to N2 fixation was investigated by inhibiting photosystem II (PSII) with DCMU. In experiments where DCMU was added before sunrise on the first day of a diel experiment, nitrogenase activities were significantly reduced compared to un-amended control incubations (average±s.d.: 11±3 vs 66±22 C2H4 m−2 h−1, P<0.0001, Figure 1b). The potential contribution of SRB to N2 fixation was investigated by adding the sulfate reduction inhibitor molybdate. Samples exposed to molybdate had lower nitrogenase activities compared to un-amended incubations (average±s.d.: 12±5 vs 63±35 C2H4 m−2 h−1, P<0.0001, Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Acetylene reduction assay (ARA) as a proxy for N2 fixation activity in intertidal microbial mats from Laguna Ojo de Liebre, Baja California, Mexico. Each time point measurement in each diel cycle experiment was conducted in triplicate (values in graphs depict the average of the three replicate measurements per time point per experiment including the s.d. as error bars). The horizontal bars indicate the incubation intervals of mat cores with acetylene in the ARA (incubation time was 3 h). (a) The diel cycle experiment was conducted in Guerrero Negro, Mexico, before the mats were transported to CA, USA, for detailed analysis. Two replicate diel cycle experiments are shown in the graph. (b, c) Diel cycle experiments of intertidal mats from Laguna Ojo de Liebre conducted in the laboratory at NASA Ames, CA, USA. Note the reduced N2 fixation rates of controls (‘in situ water') compared to the experiments in Guerrero Negro. (b) Experiment investigating the effect of DCMU on nitrogenase activity. (c) Experiment investigating the effect of molybdate on nitrogenase activity. No significant difference was detected in control ARAs conducted with in situ water versus artificial seawater (average±s.d.: 63±36 vs 64±36 C2H4 m−2 h−1, P=0.3386).

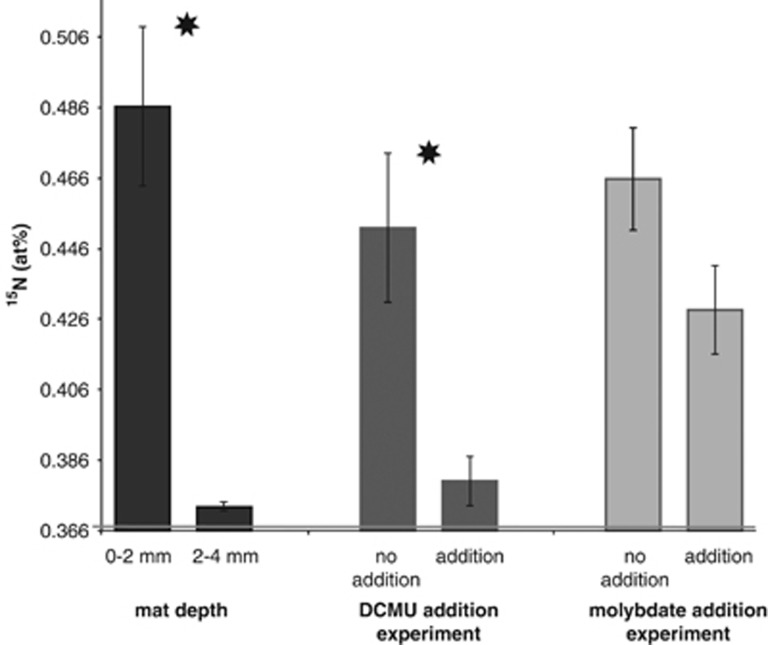

N2 fixation activity (that is, net 15N incorporation) in the intertidal mats was directly assessed with 15N2 incubation experiments (for 10 h in the dark) and subsequent IRMS analysis of both upper and lower mat layers (0 to 2 mm and 2 to 4 mm, respectively). The upper layer was significantly enriched in 15N relative to the deeper layer (Figure 2; average±s.e.: 0.486±0.023 vs 0.373±0.001 at% 15N, P<0.001). Mat cores incubated in air without 15N2 served as control samples for natural abundance and had values of (average±s.e.) 0.371±0.001 (0 to 2 mm) and 0.373±0.001 (2 to 4 mm) at% 15N. On the basis of these results, we focused all additional analyses on the upper layer. In 15N2 incubation experiments of this upper layer with and without inhibitors, mats incubated with DCMU had significantly lower 15N incorporation relative to control incubations without DCMU (Figure 2; average±s.e.: 0.380±0.007 vs 0.452±0.021 at% 15N, P<0.05). In molybdate addition experiments, incubations where molybdate was added had a slightly lower 15N enrichment than un-amended mats (average±s.e.: 0.429±0.013 vs 0.466±0.015 at% 15N, P=0.063), but the difference was not significant at the P<0.05 level.

Figure 2.

15N enrichment (at%) of mat cores that were incubated with 15N2 for 10 h in the dark measured by IRMS. Average values of three biological replicates per treatment are depicted with standard errors (for ‘0 to 2 mm depth', n=10). Asterisks indicate significant different paired treatments at P<0.05. Natural abundance of 0.37 at% 15N is indicated by a gray horizontal line.

Microbial diversity based on 16S rRNA and 16S rRNA gene analysis

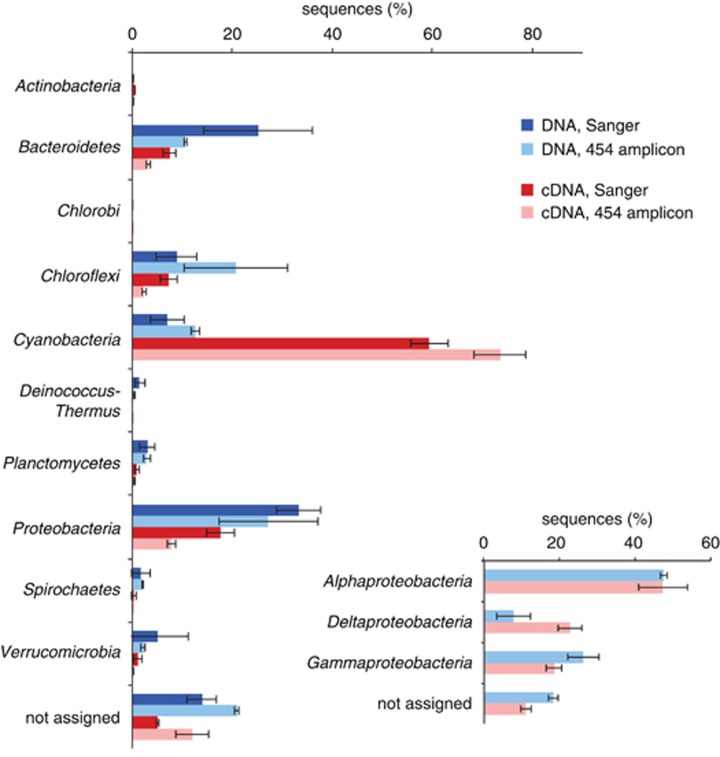

Lyngbya spp. and other filamentous cyanobacteria dominated the biomass of the upper phototrophic layer of the microbial mats from Laguna Ojo de Liebre based on light micrographs (Supplementary Figure S3). However, 16S rRNA and 16S rRNA gene sequencing indicated that the microbial community of this layer was diverse and composed of multiple bacterial phyla (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S2). DNA-derived Sanger sequences were affiliated with nine different phyla based on the RDP classifier (Wang et al., 2007). The majority of DNA sequences were classified as Proteobacteria (30–36%) and Bacteroidetes (17–33%), followed by Chloroflexi (6–12%), Cyanobacteria (5–9.5%) and Verrucomicrobia (1–9.5%). In contrast, the majority of 16S rRNA sequences (cDNA-based) grouped with Cyanobacteria (57–62%), followed by Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi and Bacteroidetes (6–20%). Based on phylogenetic analyses, all 16S rRNA cyanobacterial sequences were related to filamentous cyanobacteria (Supplementary Figure S4), and 24.4% of these cyanobacterial 16S rRNA sequences were related to Lyngbya spp., with up to 98.7% sequence identity to Lyngbya aestuarii PCC 7419 and Lyngbya sp. PCC 8106, or 97.9% identity to Lyngbya majuscula CCAP. 454 pyrotag amplicon sequencing was used to investigate the 16S rRNA and 16S rRNA gene diversity with greater coverage, and revealed reads clustering in 15 phyla (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S2). However, the trend was the same as in Sanger-based sequences (Figure 3); most of the amplicons recovered from DNA were assigned to Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi, Cyanobacteria and Bacteroidetes, while the majority of reads originating from cDNA clustered with Cyanobacteria. Calculation of the Chao1 estimator and the Shannon index revealed greater diversity in DNA-based reads than in cDNA-based reads (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 3.

Microbial community analysis based on 16S rRNA gene and transcript sequencing of the upper 2 mm of intertidal mats at Laguna Ojo de Liebre. Phyla depicted are those that contain ⩾0.1% of sequences detected by either Sanger sequencing (dark blue and dark red bars) or 454 amplicon sequencing (bars in light blue and light red). Each bar depicts the average value of 2 biological replicates. Both approaches illustrate a diverse community based on DNA analysis, with most of the sequences grouping within Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Chloroflexi and Cyanobacteria. Sequences based on cDNA are strongly dominated by Cyanobacteria (up to 74% of the sequences), followed by Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Chloroflexi. Inlet depicts proteobacterial community composition based on 454 amplicon sequences (sequence abundance of Alpha-, Delta- and Gammaproteobacteria within the Proteobacteria).

Community analysis of potential diazotrophs (nifH gene and transcript analysis)

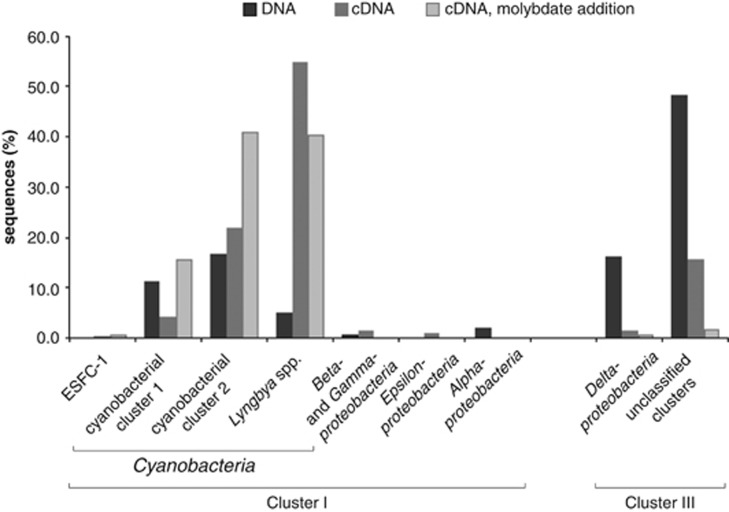

The diversity of bacteria with the genetic capability to fix N2 was specifically analyzed by sequencing nifH genes and transcripts from the upper 2 mm of the intertidal mats. Deduced amino-acid sequences formed 87 OTUs based on a cutoff of 97% sequence identity. Phylogenetic analysis of the deduced (amino-acid) NifH sequences derived from extracted DNA revealed that the majority (64.2%) grouped with Cluster III (based on Zehr et al., 2003; with uncultured microorganisms and Deltaproteobacteria), and the rest with Cluster I (with Cyanobacteria, Alpha-, Gamma- and Betaproteobacteria) (Figure 4). To focus on the community that was expressing the nifH gene, we also analyzed sequences derived from extracted RNA after reverse transcription into cDNA. The majority of these sequences (80.8%) were related to Cyanobacteria forming three major groups (Lyngbya spp.-cluster, cyanobacterial cluster 1 and 2, Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure S5), with Lyngbya spp.-related sequences being the most abundant. The other two abundant groups of cyanobacterial sequences clustered with sequences of filamentous cyanobacteria such as Phormidium and Leptolyngbya, and sequences from other microbial mats, freshwater, sponge or sediment samples. A minor proportion of the cyanobacterial nifH sequences (0.2%) were related to a cyanobacterium that is a dominant diazotroph in mats of Northern California (ESFC-1; Woebken et al., 2012; Everroad et al., 2013). Of all cDNA-based sequences, 16.9% grouped with Cluster III (1.3% of all sequences with deltaproteobacterial clusters containing known SRB and 15.5% with unclassified Cluster III sequences).

Figure 4.

Taxonomic classification of deduced (amino-acid) NifH sequences derived from DNA (nifH genes) and RNA (cDNA, nifH transcripts) in the upper 2 mm layer of intertidal microbial mats from Laguna Ojo de Liebre. Sequences derived from DNA are depicted in black (n=313), from cDNA in dark grey (n=522) and from cDNA of molybdate-treated samples in light grey (n=181). PCR amplification of cDNA from the DCMU treatment yielded no products.

NifH clone libraries (based on cDNA) of samples from the molybdate addition experiments were almost completely comprised of cyanobacterial sequences (97.2%), and only a minor portion of the sequences clustered with Cluster III (1.7%) or Deltaproteobacteria within this cluster (0.6%). Mat samples treated with DCMU during the diel cycle study failed to produce any detectable PCR product from cDNA with nifH-targeting primers (tested in two replicate RNA extractions, see Supplementary Information for details).

Single-cell isotope analysis of potential diazotrophic microbial community members

Based on the results of the inhibitor addition experiments and sequencing of expressed nifH genes, we focused our single-cell isotope analyses on Cyanobacteria and Deltaproteobacteria. The latter group was targeted to test as broadly inclusive as possible the 15N2 fixation activity of SRB within the Deltaproteobacteria. All detected Cyanobacteria were filamentous, and Lyngbya spp. filaments were easily distinguishable from other filamentous cyanobacteria based on their morphology (Supplementary Figure S3). The highest 15N enrichments in these mats were measured in Lyngbya spp. filaments (maximum of 14.54 at%), with an average (±s.e.) 15N tracer content of 4.40±0.57 at% (Figure 5, Supplementary Table S3). The enrichment in Lyngbya spp. filaments was significantly higher than in any other analyzed cells (P<0.0001 compared to small filamentous cyanobacteria; P<0.0001 compared to Deltaproteobacteria; and P=0.01 compared to unidentified single cells). Smaller filamentous cyanobacteria had an average enrichment (±s.e.) of 0.60±0.02 at% 15N with a maximum of 1.32 at%. The 15N enrichment of CARD-FISH-stained deltaproteobacterial cells from 15N2-labeled mats was not significantly different from those in control mat samples (average±s.e.: 0.38±0.00 vs 0.37±0.00 at% 15N, P=0.170). The highest 15N enrichment measured in an individual deltaproteobacterial cell was 0.41 at%.

Figure 5.

Single-cell isotope measurements by NanoSIMS of 15N2-incubated mat samples from Laguna Ojo de Liebre. (a) Elemental composition images (12C14N and 15N at%) of Lyngbya spp. filaments. However, as described in Supplementary Information, image analysis of Lyngbya spp. was not suitable for quantitative analysis of these large cells (instead isotope enrichment measurements were done by accelerated sputtering utilizing high primary ion beam currents (∼1 nA, 2 μm beam size)). Therefore, 15N isotopic composition depicted in these images will be an underestimation of the actual enrichment in 15N. (b, c) Epifluorescence micrograph and elemental composition images (12C14N and 15N at%) of analyzed small filamentous cyanobacteria. Filamentous cyanobacteria were identified based on their autofluorescence. (d) NanoSIMS analysis of Deltaproteobacteria. Epifluorescence micrographs depict cells stained by DAPI and deltaproteobacterial cells stained by CARD-FISH (with probe-mix DELTA495 a–c). Also depicted are elemental composition images (12C14N and 15N at%). (e) Boxplot diagram summarizing all measurements of the three cell types. The number of cells (or individual filaments) analyzed per cell type are indicated. 15N enrichments are depicted in at% natural abundance is 0.37 at% (indicated by a horizontal line). Lowercase letters indicate significantly different isotopic compositions between different cell types. Deltaproteobacteria were not significantly enriched in 15N relative to controls (average of 0.38 vs 0.37 at% 15N, P=0.170). The highest 15N enrichment measured in an individual deltaproteobacterial cell was 0.41 at%. Also when 15N dilution through CARD-FISH is accounted for, the deltaproteobacterial 15N isotope fraction values increase only slightly, and their corrected values are still not significantly enriched above natural abundance values (average of 0.38 at% 15N, P=0.131). We also considered the individual measured values (as opposed to the population mean), and found that based on the uncorrected values, 20.4% of the cells are significantly enriched in 15N based on a 95% confidence interval. This number increases to 31.5% if the dilution through CARD-FISH is taken into account. Scale bars represent 5 μm. Please note the different scales for 15N at% values.

Discussion

Members of the Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Chloroflexi and Cyanobacteria dominated the investigated mats based on 16S rRNA gene sequences (Figure 3), yet members of the Cyanobacteria mostly comprised the active microbial community (as inferred by 16S rRNA sequence-based community analysis). This dominance of cyanobacterial sequences in libraries derived from RNA seems to be common for microbial mats containing large filamentous cyanobacteria and was previously described (Burow et al., 2012, 2013; Lee et al., 2014). A similar pattern was observed for the nifH sequence analysis; sequences of Cluster III (including known SRB) dominated the DNA sequence pool, whereas cyanobacterial sequences dominated by far the pool of expressed nifH genes while the proportion of Cluster III sequences was strongly decreased. These data are in disagreement with earlier studies of mats from Laguna Ojo de Liebre in which nifH gene and transcript analyses suggested that both Cyanobacteria and Deltaproteobacteria (including SRB) were the major contributors for N2 fixation (Omoregie et al., 2004a, 2004b; Moisander et al., 2006). Interestingly, our detected nifH sequences in Cluster I and Cluster III, specifically sequences related to Lyngbya spp. were not detected in these previous studies. This lack of congruence could reflect temporal differences in the microbial community at the time studied (2001–2010), as these mats are characterized by a ‘pioneering life style' (Bebout et al., 1993) and thereby will most likely be dynamic in their microbial community composition. Other explanations for the differences in the detected microbial communities could be the depth of sequencing or a bias in the nucleic acid extraction. Although the same primer set was used in all studies (Zehr and Turner, 2001), in our study we added a pre-homogenization step prior to nucleic acid extraction, which could have increased the lysis efficiency of Lyngbya spp. cells.

The application of inhibitors in diel cycle studies can suggest the contribution of certain functional groups to N2 fixation, an approach that has been used extensively in the past (for example, Stal et al., 1984; Griffiths and Gallon, 1987; Bebout et al., 1993; Pinckney and Paerl, 1997; Steppe and Paerl, 2002). The addition of DCMU, an inhibitor of oxygenic photosynthesis (Oremland and Capone, 1988), during the day-time photoperiod strongly and significantly decreased N2 fixation the subsequent night, based on ARAs (Figure 1b) and 15N2 incubation experiments (Figure 2). This pattern was previously observed in non-heterocystous cyanobacterial mats (Griffiths and Gallon, 1987; Bebout et al., 1993), and also in Lyngbya spp. cultures (Bebout et al., 1993). DCMU interrupts the photosynthetic electron flow by inhibiting the O2-evolving PS II, which depletes the reductant formation required for N2 fixation (Oremland and Capone, 1988). This decrease in reductant will most likely also prevent CO2 fixation (Bebout et al., 1993; Paerl et al., 1996; Pinckney and Paerl, 1997), leading to a shortage of organic storage compounds that can be used for N2 fixation. This combined shortage in reductant can explain the observed decrease in N2 fixation rates upon DCMU addition and suggests that members of the Cyanobacteria contributed to N2 fixation activity.

This observation was supported by the detection of expressed cyanobacterial nifH genes in untreated control mats that showed N2 fixation (Figure 4). NifH transcripts related to Lyngbya spp. dominated the transcript pool, indicating that in these mats Lyngbya spp. were actively expressing nifH and potentially fixing N2. In addition, in DCMU-treated mats, we were unable to PCR amplify nifH transcripts, which is in congruence with a strong inhibition of N2 fixation activity in the DCMU addition experiment as observed in ARAs and 15N2 incubations followed by IRMS. Together, inhibitor experiments and sequence data suggested that Cyanobacteria were actively fixing N2 in the investigated mats, especially members of Lyngbya spp. However, care must be taken to infer N2 fixation activity from detected nifH transcripts or relative sequence abundance. First, nitrogenase enzyme activity can be regulated after transcription until the post-translational level (Kim et al., 1999). Furthermore, the potential for PCR biases (Suzuki and Giovannoni, 1996; Polz and Cavanaugh, 1998) makes it difficult to infer the activity of certain groups based on their nifH transcript abundance. Therefore, direct N2 fixation measurements coupled to the identification of cells are needed to clearly identify active diazotrophs in environmental samples. Incubation experiments with 15N2 and single-cell isotope analysis through NanoSIMS allowed us to investigate the active diazotrophs by measuring the incorporation of 15N into cellular biomass. This analysis revealed 15N enrichment in filamentous cyanobacteria of different morphotypes (Figures 5a–c), which corresponded to multiple detected clusters of cyanobacterial nifH sequences (Supplementary Figure S5). Consistent with the result of the nifH transcript analysis, within the filamentous cyanobacteria, Lyngbya spp. had by far the highest enrichments in 15N, demonstrating that Lyngbya spp. were the most active cyanobacterial diazotrophs in this mat. As previously detected in other diazotrophic populations (Lechene et al., 2007; Woebken et al., 2012), we observed large variations in 15N enrichments of Lyngbya spp. filaments indicating differing N2 fixation activities. A possible explanation could be spatial heterogeneity in the local environment.

In this study, we sought to take a function-based approach to investigate previous reports that SRB were contributing to N2 fixation in this mat type (Omoregie et al., 2004a, 2004b; Moisander et al., 2006). In a parallel study, our group measured significant sulfate reduction (as sulfide production) in these same mat samples (Lee et al., 2014). Therefore we can conclude that the sampled mats contained SRB that were physiologically active and that sulfate reduction was not inhibited on account of sampling and transport to the laboratory. On the intertidal flats at Laguna Ojo de Liebre, the mats experience naturally frequent alternating periods of desiccation (leading to aeration) and tidal flooding (Javor and Castenholz, 1984; Omoregie et al., 2004b; Rothrock and Garcia-Pichel, 2005). It appears that SRB in these mats are tolerant against oxygen exposure and maintain their capacity for sulfate reduction even after long oxic periods. The oxygen tolerance of SRB is a phenomenon previously described in cultured SRB and different mats (Canfield and Des Marais, 1991; Minz et al., 1999; Baumgartner et al., 2006; Fike et al., 2008). Detection of expressed dsrA genes (a key functional gene for sulfate reduction) by Lee et al. (2014) in the mats supports our conclusion that SRB were active, and sequencing revealed that the vast majority of the SRB that expressed dsrA (97%) belonged to previously known clusters within the Deltaproteobacteria (to Desulfobacteraceae and Desulfovibrionales). Sequences assigned to the Desulfobacterales (Desulfobacteraceae) and Desulfovibrionales (Desulfohalobiaceae) were also identified through 16S rRNA sequencing. These data further support our focus on deltaproteobacterial SRB in our single-cell isotope measurements. We are aware of the possibility that non-deltaproteobacterial heterotrophic diazotrophs exist in these mats, for example related to unidentified groups in Cluster III (designated ‘unclassified clusters' Figure 4). Unfortunately, owing to lack of isolates in these clusters, these bacteria are unidentified at the 16S rRNA level and thus cannot be targeted by a FISH-NanoSIMS approach.

Adding molybdate to the mats resulted in reduced nitrogenase activities in ARAs compared to un-amended samples (Figure 1c). Molybdate serves as a structural analog of sulfate and blocks the sulfate activation, thereby depleting ATP pools in SRB and ultimately causing death (Oremland and Capone, 1988). This effect of molybdate in ARAs was previously observed in an intertidal photosynthetic mat, where molybdate inhibited night-time nitrogenase activity by as much as 64% (Steppe and Paerl, 2002). However, it was previously recognized that reduced N2 fixation rates in response to molybdate additions could result from many direct effects, but also indirect consequences, such as altered environmental conditions due to the inhibition of sulfide production (Steppe and Paerl, 2002). Results based on this ‘specific inhibitor' should be interpreted with caution, a conclusion further supported by our study. In mats from Laguna Ojo de Liebre, the effect of molybdate on overall N2 fixation rates was only significant in ARAs, whereas 15N2 incubation experiments revealed a much less pronounced (and not significant) effect (Figure 2). This observed difference in the effect based on the applied assays could conceivably be caused by an enhanced consumption of ethylene, the measured product in ARAs, in molybdate-treated mats relative to un-amended controls. Ethylene can be metabolized aerobically (de Bont, 1976), and anaerobically (Koene-Cottaar and Schraa, 1998) by microorganisms, and especially the possibility of methanogens reducing ethylene (Oremland, 1981; Elsgaard, 2013) should be mentioned in experiments where SRB are inhibited. Thus, enhanced ethylene consumption in the molybdate treatments could mistakenly be interpreted as a large contribution of SRB to N2 fixation.

In this study, molybdate addition experiments coupled with 15N2 incubations and IRMS analyses did not indicate a significant contribution of SRB to N2 fixation, whereas earlier studies suggested that Deltaproteobacteria in nifH Cluster III, and more specifically SRB within the Deltaproteobacteria, were potentially important diazotrophs in photosynthetic mats (Steppe and Paerl, 2002; Omoregie et al., 2004a, 2004b). Sequencing of nifH genes and transcripts in our study indicated that sequences of Cluster III (including known SRB) dominated the DNA sequence pool, whereas cyanobacterial sequences dominated vastly the pool of expressed nifH genes, and the proportion of Cluster III sequences was strongly decreased (Figure 4). On account of potential PCR biases, one can only interpret the data semiquantitatively; however, these observations suggest that members of the Cyanobacteria were more actively expressing nifH genes than SRB within Cluster III. This hypothesis is supported by our NanoSIMS analyses, in which Deltaproteobacteria were not significantly enriched in 15N relative to controls (average of 0.38 vs 0.37 at% 15N, P=0.170). These cells were stained by CARD-FISH in contrast to the Cyanobacteria, which could introduce 14N-containing compounds during the procedure leading to a dilution of 15N and thereby to an underestimation of the 15N enrichment. Therefore, we analyzed the effect of CARD-FISH on the 15N (and for completeness also 13C) isotope content in isotopically labeled reference cells (Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis) and detected significantly reduced 15N and 13C isotope contents in these cells by NanoSIMS measurements (P<0.001, Supplementary Figures S6–S8, Supplementary Tables S4–S6; experiments are explained in detail in Supplementary Information). Our data indicate that CARD-FISH can result in an apparent dilution of up to 28% for N (and 38% for C). By using these data (28% dilution as a worst-case scenario for N), we tested whether the 15N isotope enrichments measured in microbial mat Deltaproteobacteria were strongly influenced by CARD-FISH (see Supplementary Information for calculations and discussion). On the basis of these calculations, when the CARD-FISH 15N dilution is accounted for, the deltaproteobacterial 15N isotope fraction values increase only slightly, and their corrected values are still not significantly enriched above natural abundance values (average of 0.38 at% 15N, P=0.131). We also considered the individual measured values (as opposed to the population mean), and found that, based on the uncorrected values, 20.4% of the cells are significantly enriched in 15N based on a 95% confidence interval. This number increases to 31.5% if the dilution through CARD-FISH is taken into account. However, the levels of enrichments were very low compared to the values measured in Cyanobacteria. We conclude that even though CARD-FISH has an effect on the 15N isotopic composition, the 15N enrichment values of investigated Deltaproteobacteria in this study changed very little when CARD-FISH dilution was accounted for.

Based on this combined approach of inhibitor addition experiments, nifH gene and transcript sequencing, and 15N2 incubations coupled with single-cell isotope analysis, we did not find support that the analyzed deltaproteobacterial SRB contributed significantly to N2 fixation in intertidal mats from Laguna Ojo de Liebre and conclude that their activity level was negligible for the N budget of the mat. Instead, the combined data indicate that Lyngbya spp. -related cyanobacteria were highly active diazotrophs in the mats at the investigated time.

Acknowledgments

We thank Angela Detweiler, Jan Dolinsek, Mike Kubo and Christina Ramon for their excellent technical assistance, José Q García-Maldonado for his assistance in the field, Andrew McDowell at UC Berkeley for IRMS analyses, and Stephanie A Eichorst for helpful comments on the manuscript. We are grateful for access to the field site and for the logistical support provided by Exportadora de Sal, S.A. de C.V. This work was performed under Fishery Permit DAPA/2/080310/734 granted by the National Commission of Aquaculture and Fishery of the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries and Food (Mexico). Work at LLNL was performed under the auspices of the DOE under contract DE-AC52-07NA27344. Work at LBNL was performed under the auspices of the DOE under contract DE-AC02-05CH11231. This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, Genomic Sciences Program, under contract number SCW1039. This work was further financially supported by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) (to DW) and the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) (P 25700-B20 to DW). FB and MW were supported by the European Research Council (Advanced Grant Nitrification Reloaded (NITRICARE) 294343).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

Supplementary Material

References

- Baumgartner LK, Reid RP, Dupraz C, Decho AW, Buckley DH, Spear JR, et al. Sulfate reducing bacteria in microbial mats: changing paradigms, new discoveries. Sediment Geol. 2006;185:131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Bebout BM, Fitzpatrick MW, Paerl HW. Identification of the sources of energy for nitrogen fixation and physiological characterization of nitrogen-fixing members of a marine microbial mat community. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1495–1503. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1495-1503.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebout BM, Paerl HW, Bauer JE, Canfield DE, Des Marais DJ.1994Nitrogen cycling in microbial mat communities: the quantitative importance of N-fixation and other sources of N for primary productivityIn: Stal LJ, Caumette P (eds)Microbial Mats Springer-Verlag: Berlin; 265–272. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman B, Gallon JR, Rai AN, Stal LJ. N2 fixation by non-heterocystous cyanobacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1997;19:139–185. [Google Scholar]

- Burow LC, Woebken D, Marshall IPG, Lindquist EA, Bebout BM, Prufert-Bebout L, et al. Anoxic carbon flux in photosynthetic microbial mats as revealed by metatranscriptomics. ISME J. 2013;7:817–829. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burow LC, Woebken D, Bebout BM, McMurdie PJ, Singer SW, Pett-Ridge J, et al. Hydrogen production in photosynthetic microbial mats in the Elkhorn Slough estuary, Monterey Bay. ISME J. 2012;6:863–874. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield DE, Des Marais DJ. Aerobic sulfate reduction in microbial mats. Science. 1991;251:1471–1473. doi: 10.1126/science.11538266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YB, Dominic B, Mellon MT, Zehr JP. Circadian rhythm of nitrogenase gene expression in the diazotrophic filamentous nonheterocystous cyanobacterium Trichodesmium sp. strain IMS 101. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3598–3605. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3598-3605.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cliff JB, Gaspar DJ, Bottomley PJ, Myrold DD. Exploration of inorganic C and N assimilation by soil microbes with time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:4067–4073. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.8.4067-4073.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bont JAM. Oxidation of ethylene by soil bacteria. A Van Leeuw J Microb. 1976;42:59–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00399449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekas AE, Poretsky RS, Orphan VJ. Deep-sea archaea fix and share nitrogen in methane-consuming microbial consortia. Science. 2009;326:422–426. doi: 10.1126/science.1178223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsgaard L. Reductive transformation and inhibitory effect of ethylene under methanogenic conditions in peat-soil. Soil Biol Biochem. 2013;60:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Everroad RC, Woebken D, Singer SW, Burow LC, Kyrpides N, Woyke T, et al. Draft genome sequence of an oscillatorian cyanobacterium, Strain ESFC-1. Genome Announc. 2013;1:e00527–13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00527-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fike DA, Gammon CL, Ziebis W, Orphan VJ. Micron-scale mapping of sulfur cycling across the oxycline of a cyanobacterial mat: a paired nanoSIMS and CARD-FISH approach. ISME J. 2008;2:749–759. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming ED, Bebout BM, Castenholz RW. Effects of salinity and light on the resumption of photosynthesis in rehydrated cyanobacterial mats from Baja California Sur, Mexico. J Phycol. 2007;43:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Foster RA, Kuypers MMM, Vagner T, Paerl RW, Musat N, Zehr JP. Nitrogen fixation and transfer in open ocean diatom-cyanobacterial symbioses. ISME J. 2011;5:1484–1493. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaby JC, Buckley DH. A global census of nitrogenase diversity. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:1790–1799. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths MSH, Gallon JR. The diurnal pattern of dinitrogen fixation by cyanobacteria in situ. New Phytol. 1987;107:649–657. [Google Scholar]

- Halm H, Musat N, Lam P, Langlois R, Musat F, Peduzzi S, et al. Co-occurrence of denitrification and nitrogen fixation in a meromictic lake, Lake Cadagno (Switzerland) Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:1945–1958. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert RA. Nitrogen cycling in coastal marine ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1999;23:563–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1999.tb00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javor BJ, Castenholz RW.1984Productivity studies of microbial mats, Laguna Guerrero Negro, MexicoIn: Cohen Y, Castenholtz RW, Halvorson HO (eds)Microbial Mats: Stromatolites Alan R. Liss Inc.: New York, NY, USA; 149–170. [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Zhang Y, Roberts GP. Correlation of activity regulation and substrate recognition of the ADP-ribosyltransferase that regulates nitrogenase activity in Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1698–1702. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.5.1698-1702.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koene-Cottaar FHM, Schraa G. Anaerobic reduction of ethene to ethane in an enrichment culture. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1998;25:251–256. [Google Scholar]

- Lechene C, Hillion F, McMahon G, Benson D, Kleinfeld AM, Kampf JP, et al. High-resolution quantitative imaging of mammalian and bacterial cells using stable isotope mass spectrometry. J Biol. 2006;5:20. doi: 10.1186/jbiol42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechene CP, Luyten Y, McMahon G, Distel DL. Quantitative imaging of nitrogen fixation by individual bacteria within animal cells. Science. 2007;317:1563–1566. doi: 10.1126/science.1145557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JZ, Burow LC, Woebken D, Everroad RC, Kubo MD, Spormann AM, et al. Fermentation couples Chloroflexi and sulfate-reducing bacteria to Cyanobacteria in hypersaline microbial mats. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:61. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loy A, Lehner A, Lee N, Adamczyk J, Meier H, Ernst J, et al. Oligonucleotide microarray for 16S rRNA gene-based detection of all recognized lineages of sulfate-reducing prokaryotes in the environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:5064–5081. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.10.5064-5081.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lücker S, Steger D, Kjeldsen KU, MacGregor BJ, Wagner M, Loy A. Improved 16S rRNA-targeted probe set for analysis of sulfate-reducing bacteria by fluorescence in situ hybridization. J Microbiol Meth. 2007;69:523–528. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minz D, Fishbain S, Green SJ, Muyzer G, Cohen Y, Rittmann BE, et al. Unexpected population distribution in a microbial mat community: sulfate-reducing bacteria localized to the highly oxic chemocline in contrast to a eukaryotic preference for anoxia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4659–4665. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.10.4659-4665.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moisander PH, Shiue L, Steward GF, Jenkins BD, Bebout BM, Zehr JP. Application of a nifH oligonucleotide microarray for profiling diversity of N2-fixing microorganisms in marine microbial mats. Environ Microbiol. 2006;8:1721–1735. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omoregie EO, Crumbliss LL, Bebout BM, Zehr JP. Determination of nitrogen-fixing phylotypes in Lyngbya sp. and Microcoleus chthonoplastes cyanobacterial mats from Guerrero Negro, Baja California, Mexico. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:2119–2128. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2119-2128.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omoregie EO, Crumbliss LL, Bebout BM, Zehr JP. Comparison of diazotroph community structure in Lyngbya sp. and Microcoleus chthonoplastes dominated microbial mats from Guerrero Negro, Baja, Mexico. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2004;47:305–308. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6496(03)00301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oremland RS. Microbial formation of ethane in anoxic estuarine sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;42:122–129. doi: 10.1128/aem.42.1.122-129.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oremland RS, Capone DG. Use of “specific” inhibitors in biogeochemistry and microbial ecology. Adv Microb Ecol. 1988;10:285–383. [Google Scholar]

- Paerl HW, Prufert LE, Ambrose WW. Contemporaneous N2 fixation and oxygenic photosynthesis in the nonheterocystous mat-forming cyanobacterium Lyngbya aestuarii. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3086–3092. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.11.3086-3092.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paerl HW, Fitzpatrick M, Bebout BM. Seasonal nitrogen fixation dynamics in a marine microbial mat: Potential roles of cyanobacteria and microheterotrophs. Limnol Oceanogr. 1996;41:419–427. [Google Scholar]

- Pernthaler A, Pernthaler J, Amann R. Fluorescence in situ hybridization and catalyzed reporter deposition for the identification of marine bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:3094–3101. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.6.3094-3101.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinckney JL, Paerl HW. Anoxygenic photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation by a microbial mat community in a Bahamian hypersaline lagoon. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:420–426. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.420-426.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploug H, Adam B, Musat N, Kalvelage T, Lavik G, Wolf-Gladrow D, et al. Carbon, nitrogen and O2 fluxes associated with the cyanobacterium Nodularia spumigena in the Baltic Sea. ISME J. 2011;5:1549–1558. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polz MF, Cavanaugh CM. Bias in template-to-product ratios in multitemplate PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3724–3730. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3724-3730.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popa R, Weber PK, Pett-Ridge J, Finzi JA, Fallon SJ, Hutcheon ID, et al. Carbon and nitrogen fixation and metabolite exchange in and between individual cells of Anabaena oscillarioides. ISME J. 2007;1:354–360. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothrock Jr, MJ, Garcia-Pichel F. Microbial diversity of benthic mats along a tidal desiccation gradient. Environ Microbiol. 2005;7:593–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stal LJ, Bergman B. Immunological characterization of nitrogenase in the filamentous non-heterocystous cyanobacterium Oscillatoria limosa. Planta. 1990;182:287–291. doi: 10.1007/BF00197123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stal LJ, Krumbein WE. Aerobic nitrogen fixation in pure cultures of a benthic marine Oscillatoria (cyanobacteria) FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1981;11:295–298. [Google Scholar]

- Stal LJ, Grossberger S, Krumbein WE. Nitrogen fixation associated with the cyanobacterial mat of a marine laminated microbial ecosystem. Mar Biol. 1984;82:217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Steppe TF, Olson JB, Paerl HW, Litaker RW, Belnap J. Consortial N2 fixation: a strategy for meeting nitrogen requirements of marine and terrestrial cyanobacterial mats. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1996;21:149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Steppe TF, Paerl HW. Potential N2 fixation by sulfate-reducing bacteria in a marine intertidal microbial mat. Aquat Microb Ecol. 2002;28:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki MT, Giovannoni SJ. Bias caused by template annealing in the amplification of mixtures of 16S rRNA genes by PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:625–630. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.625-630.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woebken D, Burow LC, Prufert-Bebout L, Bebout BM, Hoehler TM, Pett-Ridge J, et al. Identification of a novel cyanobacterial group as active diazotrophs in a coastal microbial mat using NanoSIMS analysis. ISME J. 2012;6:1427–1439. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehr JP, Mellon M, Braun S, Litaker W, Steppe T, Paerl HW. Diversity of heterotrophic nitrogen fixation genes in a marine cyanobacterial mat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2527–2532. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2527-2532.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehr JP, Turner PJ.2001Nitrogen fixation: nitrogenase genes and gene expressionIn: Paul JH (eds)Methods in Microbiology Academic Press: New York, NY, USA; 271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Zehr JP, Jenkins BD, Short SM, Steward GF. Nitrogenase gene diversity and microbial community structure: a cross-system comparison. Environ Microbiol. 2003;5:539–554. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.