Background: EOGT (epidermal growth factor (EGF) domain-specific O-linked N-acetylglucosamine) mutations have been identified in patients with Adams-Oliver syndrome (AOS).

Results: O-Linked N-acetylglucosaminylation (O-GlcNAcylation) of EGF domains in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is impaired in all EOGT variants associated with AOS.

Conclusion: AOS-causative EOGT mutations affect ER O-GlcNAcylation.

Significance: Impaired EOGT glycosyltransferase activity and a consequent reduction in O-GlcNAcylation underlie the etiology of EOGT-related AOS.

Keywords: Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER), Glycoconjugate, Glycosyltransferase, Notch Receptor, O-GlcNAcylation, Adams-Oliver Syndrome, EOGT, Hexosamine Pathway

Abstract

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) domain-specific O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (EOGT) is an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-resident O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) transferase that acts on EGF domain-containing proteins such as Notch receptors. Recently, mutations in EOGT have been reported in patients with Adams-Oliver syndrome (AOS). Here, we have characterized enzymatic properties of mouse EOGT and EOGT mutants associated with AOS. Simultaneous expression of EOGT with Notch1 EGF repeats in human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells led to immunoreactivity with the CTD110.6 antibody in the ER. Consistent with the GlcNAc modification in the ER, the enzymatic properties of EOGT are distinct from those of Golgi-resident GlcNAc transferases; the pH optimum of EOGT ranges from 7.0 to 7.5, and the Km value for UDP N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) is 25 μm. Despite the relatively low Km value for UDP-GlcNAc, EOGT-catalyzed GlcNAcylation depends on the hexosamine pathway, as revealed by the increased O-GlcNAcylation of Notch1 EGF repeats upon supplementation with hexosamine, suggesting differential regulation of the luminal UDP-GlcNAc concentration in the ER and Golgi. As compared with wild-type EOGT, O-GlcNAcylation in the ER is nearly abolished in HEK293T cells exogenously expressing EOGT variants associated with AOS. Introduction of the W207S mutation resulted in degradation of the protein via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, although the stability and ER localization of EOGTR377Q were not affected. Importantly, the interaction between UDP-GlcNAc and EOGTR377Q was impaired without adversely affecting the acceptor substrate interaction. These results suggest that impaired glycosyltransferase activity in mutant EOGT proteins and the consequent defective O-GlcNAcylation in the ER constitute the molecular basis for AOS.

Introduction

O-Linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) modification of nuclear, cytosolic, and mitochondrial proteins is prevalent in multicellular organisms, where more than 1,000 O-GlcNAcylated proteins have been identified (1, 2). The intracellular O-GlcNAcylation is reversible, and the cycling is dynamically regulated by intracellular O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT)2 and O-GlcNAcase. A large number of studies have indicated that O-GlcNAcylation is involved in various cellular functions, including transcription (3), epigenesis (4), cellular signaling (5), cell differentiation (6), stress (7), and glucose sensing (8) (reviewed in Ref. 9). Although it had long been postulated that O-GlcNAc is a unique intracellular modification and that intracellular OGT is the sole enzyme catalyzing the O-GlcNAc transfer reaction, extracellular O-GlcNAc was discovered on extracellular domains of Notch receptors (10). Moreover, in vivo studies revealed that O-GlcNAc is abundantly expressed in the Drosophila cuticle (11). Among cuticle proteins, Dumpy, a giant membrane-anchored cuticle protein containing a very large number of EGF-like domains, was identified as a major O-GlcNAcylated protein. In addition to Notch and Dumpy, Delta, and Serrate, ligands for Notch receptors, have been shown to be O-GlcNAcylated. The addition of O-GlcNAc onto extracellular proteins is catalyzed by EGF domain-specific O-GlcNAc transferase (EOGT).

The biological function of extracellular O-GlcNAc was first suggested by the phenotype of the Eogt mutant in Drosophila (11). Although the Eogt mutant does not exhibit the classical Notch phenotype, it shows the defects in the wings, notum, and cuticle (i.e. wing blistering, vortex, and cuticle detachment), similar to the dumpy mutant. A genetic interaction was observed between Eogt and dumpy or Eogt and pyrimidine metabolism pathway components in the wing blister phenotype (12). These studies suggested that Eogt regulates Dumpy-mediated processes directly or indirectly through regulation of pyrimidine metabolism.

EOGT is evolutionarily conserved from Caenorhabditis elegans to humans. Accordingly, extracellular O-GlcNAc is found on five extracellular O-GlcNAcylated proteins (Hspg2, Nell1, Lama5, Pamr1, and Notch2) present in the mouse cerebral cortex (13). It was also suggested that thrombospondin-1 is O-GlcNAcylated in platelets (14). Sequence alignment of O-GlcNAcylated proteins suggested that the predictive consensus sequence for the modification is CXXGX(T/S)GXXC, which is located between the fifth and sixth conserved cysteines of the EGF domain. In contrast to the pivotal roles of extracellular O-GlcNAc in Drosophila development, much less is known regarding the biological requirement of EOGT in mammals (15). The first implication came from a recent report of an EOGT mutation in a rare human congenital disorder, Adams-Oliver syndrome (AOS), which is characterized by aplasia cutis congenital and terminal transverse limb defects (16, 17). The aim of this study was to biochemically analyze EOGT mutations linked to AOS and demonstrate that a defect in O-GlcNAcylation in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) caused by EOGT mutations constitutes the molecular basis for AOS.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-EOGT (Sigma), rabbit anti-myc (Santa Cruz), mouse anti-calnexin (BD Biosciences), mouse anti-β-tubulin antibody (Seven Hills Bioreagents), rat anti-GFP antibody (Nacalai Tesque), anti-FLAG antibody (M2, Sigma), mouse anti-His antibody (MBL), and anti-multiubiquitin antibody (MBL). MG132 was obtained from Santa Cruz. Phytohemagglutinin-L lectin was obtained from Vector. Endonuclease-prepared small interfering RNA (esiRNA) against human OGT (HU-08230-1), and Renilla luciferase were obtained from Sigma. Mouse anti-O-GlcNAc antibodies, CTD110.6 and RL2, were obtained from Thermo Scientific and Abcam, respectively.

Plasmid Constructs

pSectag2/Hygro C/mouse Notch1 EGF1-36-mycHis6/IRES-EGFP expression vector encoding Myc-His-tagged mouse Notch1 EGF repeats (N1EGF1–36-MycHis), originally generated by Bob Haltiwanger, was provided by Pamela Stanley (18). pSegtag2/EOGT-IRES-GFP and pEF/EOGT-FLAG expression vectors were as described previously (19). The point or deletion mutations of EOGT constructs were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using a KOD-Plus Mutagenesis Kit (Toyobo). All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. All primers used are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| EOGT construct | Forward primer (5′→3′) | Reverse primer (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|

| EOGT W207S | GTTTGCTGAGCTACAAGGCT | GAAGACTGCAGGGGACTTTT |

| EOGT R377Q | CAGAAAATCCTGAACCAAGAC | GTATTCTGTGCTGCGTGCAAG |

| EOGT Δ359–527 | CATGATGAGCTATAGACTCGA | TCCCTCTTGAGTGATGTTCAG |

| EOGTΔ359–527 + HDEL | TAGACTCGAGGAGGGCCCGAA | TCCCTCTTGAGTGATGTTCAG |

Cell Culture and Transfection

Human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells were cultured in high-glucose (25 mm) DMEM (Sigma) supplemented with 10% FBS unless otherwise noted. Each expression vector or esiRNA was transiently transfected into HEK293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. CHO cells were cultured in low-glucose (5 mm) DMEM (Nissui Pharmaceutical) supplemented with 10% FBS. CHO cells stably expressing FLAG-EOGT or FLAG-EOGTR377Q were established by transfecting pEF/EOGT-FLAG (19) or pEF/EOGT-FLAGR377Q into CHO cells followed by selection using 500 μg/ml of G418 (Wako) for 3 weeks.

Purification of FLAG-EOGT

For the purification of FLAG-EOGT from cell lysates, cells were lysed in lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology; 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm Na2EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mm β-glycerophosphate, 1 mm Na3VO4, and 1 μg/ml of leupeptin) and the lysates were mixed with anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel beads (Sigma). After incubation for 2 h at 4 °C, the immunoprecipitates were washed extensively with 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, and 0.25% Triton X-100, and then eluted with SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing 2% SDS and 70 mm 2-mercaptoethanol or with 1 mg/ml of 3× FLAG peptide in 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.0.

Preparation of Recombinant EGF20

To prepare the unglycosylated recombinant EGF domain, the V5-hexahistidine-tagged 20th EGF domain of Drosophila Notch (EGF20) was prepared using the Kluyveromyces lactis protein expression kit (New England Biolabs). In brief, the EGF20:V5His fragment was cloned into the pKLAC1 expression vector, and the resultant plasmid was transformed into K. lactis GG799 cells (20). The transformed K. lactis cells were streaked on yeast carbon base (YCB) agar plates containing 5 mm acetamide; then, individual colonies were incubated in 1 ml of YPGal (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% galactose) medium for 2 days. The cell suspension was transferred to 500 ml of fresh YPGal medium and incubated for an additional 4 days to obtain saturated culture. The culture medium was collected by centrifugation at 4,160 × g for 15 min, filtered through a 0.45-μm filter, and concentrated 10-fold using Spin-X UF concentrators (5-kDa cut-offs; Corning). Concentrated medium was supplemented with one-tenth volume of FastBreak Cell Lysis Reagent (Promega), incubated for 30 min at 4 °C, and passed through the column packed with 3 ml of Complete His-Tag purification resin (Roche Applied Science). After washing with 100 mm HEPES, 10 mm imidazole, pH 7.5, bound proteins were eluted with 100 mm HEPES, 500 mm imidazole, pH 7.5. The eluate was concentrated and buffer exchanged into 100 mm HEPES, pH 7.0, using Spin-X UF concentrators (5-kDa cut-offs).

O-GlcNAc Transferase Assay

EOGT assay was performed in 20 μl of the glycosylation buffer (250 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, and 1 mm MnCl2) containing 5 μm UDP-[3H]GlcNAc (2 Ci/mmol), 2.0 μg of EGF20-V5His, and 1.0 μg of FLAG-tagged EOGT at 37 °C for 60 min unless otherwise noted. The reaction was applied to a LC-18 SPE tube (Supelco), washed with 5 ml of MilliQ, and eluted with 1 ml of 80% acetonitrile and 0.052% trifluoroacetic acid. Radioactivity in the elution was measured using a liquid scintillation counter (Aloka).

Purification of N1EGF1–36-MycHis and Western Blotting

For the purification of N1EGF1–36-MycHis from cell lysates, cells were lysed with lysis buffer, and then the lysates were combined with 0.2 μg of anti-myc antibody (4A6, Upstate). After incubation for 2 h at 4 °C, 5 μl of Protein G Mag-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) was added to the lysates, which were then incubated for 1 h at 4 °C. The immunoprecipitates were washed extensively with 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, and 0.25% Triton X-100 and then eluted with SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing 2% SDS and 70 mm 2-mercaptoethanol. For Western blotting, each sample was separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore). The membrane was probed with the appropriate primary antibody (1:1000 dilution) and HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000 dilution); this was followed by detection with Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore) and exposure to x-ray film. Quantification of ECL-exposed films was performed using a flatbed scanner, GT-X900 (Epson), and ImageJ 1.48 software.

Immunostaining

HEK293T cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min and cold methanol for 5 min. Cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min and blocked with PBS containing 5% FBS for 30 min. Immunostaining was performed by incubating first with the appropriate primary antibody (1:100 dilution) for 2 h and then with a fluorescent dye-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000 dilution) for 1 h. All samples were analyzed using a FV10 confocal microscopy (Olympus).

Hexosamine Treatment

HEK293T cells cultured in low-glucose DMEM/FBS were transiently transfected to express N1EGF1–36-MycHis with or without EOGT in Opti-MEM cell culture medium (Invitrogen) using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen). After 6 h, transfected cells were incubated for 36 h in low-glucose DMEM or low-glucose DMEM supplemented with 25 mm glucose, 10 mm glucosamine, 10 mm GlcNAc, or various concentrations of mannitol. Glucosamine was prepared as a 1 m stock solution dissolved in 500 mm HEPES, pH 7.0.

PNGase F Treatment

N1EGF1–36-MycHis was immunopurified from transfected HEK293T cells, using anti-Myc antibodies. After elution and denaturation of the bound protein by using 1× denaturing buffer (New England Biolabs), glycosidase digestion was performed for 1 h at 37 °C in 50 mm sodium citrate, pH 6.0, containing 1% Nonidet P-40, protease inhibitor mixture set I (Calbiochem), and PNGase F (Roche Applied Science).

Ultracentrifugation

HEK293T cells expressing wild-type or mutant forms of EOGT were lysed in lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology), and cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 17,860 × g for 15 min. The supernatants were further ultracentrifuged at 135,000 × g for 17 h. The supernatants and pellets were subjected to immunoblot analysis.

Binding Assay for EOGT

To detect binding between EOGT and EGF20, HEK293T cells were transfected with pSegtag2/EOGT-IRES-GFP, pSegtag2/EOGTR377Q-IRES-GFP, or pSectag2-IRES-GFP. Transfected cells were cultured for 2 days and then lysed in lysis buffer. Next, 0.1 μg of EGF20-V5His was added to 500 μl of the cell lysates, which were then incubated for 2 h at 4 °C. The mixtures were then purified using MagneHis nickel particles (Promega) to isolate EGF20-V5His-binding proteins, which were then analyzed by immunoblotting. Alternatively, 5 μg of purified EOGT or EOGTR377Q were incubated with 2.0 μg of EGF20-V5His in 500 μl of lysis buffer in the presence or absence of 5 μm UDP-GlcNAc. After incubation for 2 h at 4 °C, the mixtures were purified to isolate the EGF20·EOGT complex using MagneHis nickel particles, which were then analyzed by immunoblotting.

To detect binding between EOGT and EGF20, CHO cells stably transfected with pEF/EOGT-FLAG or pEF/EOGTR377Q-FLAG were lysed in lysis buffer and 500 μl of the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel beads (Sigma). After washing with PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100, 0.1 μg of EGF20-V5His was added to the beads and then incubated for 2 h at 4 °C. The mixtures were washed with PBS supplemented with 0.05% Triton X-100 to isolate the EGF20·EOGT complex and analyzed by immunoblotting.

To detect binding between EOGT and UDP-GlcNAc, HEK293T cells were transfected with pEF/EOGT-FLAG, pEF/EOGTR377Q-FLAG, or pEF/mycHis control vector, cultured for 2 days, and lysed in lysis buffer. Five hundred microliters of cell lysates were then supplemented with 5 μm UDP-[3H]GlcNAc and 2.0 μg of EGF20. After incubation for 30 min on ice, the mixtures were immunoprecipitated using anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel beads (Sigma) and radioactivity was measured.

RESULTS

O-GlcNAcylation in the ER

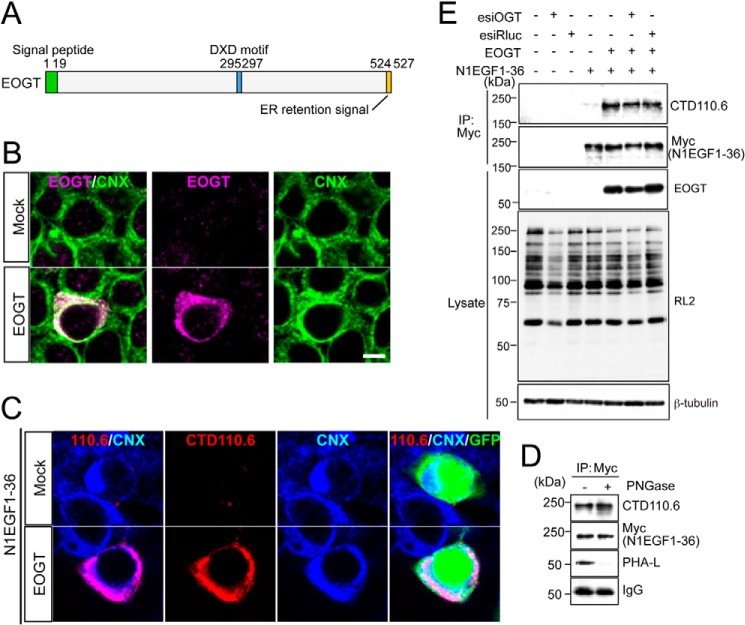

EOGT contains a hydrophobic region corresponding to a signal peptide at the amino terminus, and a KDEL-like ER-retrieval sequence at the carboxyl terminus (Fig. 1A) (11). ER localization of EOGT was detected in HEK293T cells transiently transfected to express EOGT (Fig. 1B). N1EGF1–36-MycHis was used to monitor EOGT-catalyzed O-GlcNAcylation in the cells, as the Notch1 EGF repeats possess an array of potential O-GlcNAcylation sites (10). HEK293T cells cotransfected with EOGT and N1EGF1–36-MycHis exhibited intense immunostaining for CTD110.6 antibody, and this staining overlapped with the staining for the anti-calnexin antibody (Fig. 1C). In contrast, HEK293T cells transfected with N1EGF1–36-MycHis alone exhibited weak cytoplasmic staining. These data indicated that EOGT-catalyzed O-GlcNAcylation occurs in the ER.

FIGURE 1.

O-GlcNAcylation occurs in the ER. A, schematic representation of the structure of EOGT. EOGT encodes a luminal ER protein that contains an amino-terminal signal peptide (green) and a carboxyl-terminal KDEL-like ER-retrieval signal (orange). A putative DXD motif involved in binding to the nucleotide sugar is shown in blue. B, immunostaining with anti-EOGT and calnexin (CNX) antibodies in EOGT- or mock-transfected HEK293T cells. C, N1EGF1–36-MycHis was expressed in HEK293T cells to monitor O-GlcNAcylation by EOGT. Cotransfectants of N1EGF1–36-MycHis and EOGT showed strong immunoreactivity to CTD110.6 antibody. In contrast, weak immunostaining was observed in cells expressing N1EGF1–36-MycHis alone. GFP expression indicates N1EGF1–36-MycHis-transfected cells. D, N1EGF1–36-MycHis was immunoprecipitated from the cell lysate of HEK293T cells expressing EOGT, untreated or deglycosylated with PNGase F, and immunoblotted with CTD110.6, anti-Myc tag antibody, or anti-mouse IgG antibody. Where indicated, lectin blotting with phytohemagglutinin-L (PHA-L) was performed. Note that PHA-L detects N-glycans on anti-Myc tag antibodies. E, N1EGF1–36-MycHis immunoprecipitated (IP) from the cell lysates of HEK293T cells co-transfected with or without EOGT together with esiRNA against OGT (esiOGT) or Renilla luciferase (esiRluc) was analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with the indicated antibodies.

It was recently reported that CTD110.6 antibody binds terminal β-GlcNAc on complex N-glycans (21). To exclude the possibility that EOGT generates a CTD110.6-reactive epitope on N-glycan, we analyzed the immunoreactivity of N1EGF1–36-MycHis toward CTD110.6 antibody after removal of N-glycans. PNGase treatment of affinity-purified N1EGF1–36-MycHis revealed that the CTD110.6 reactivity of N1EGF1–36-MycHis was not altered, whereas N-glycans on the anti-Myc tag antibody were barely observed (Fig. 1D). These results confirmed the specificity of CTD110.6 for O-GlcNAc under our experimental conditions.

Except for a few proteins such as Notch receptors, most O-GlcNAcylation occurs by the action of intracellular OGT. We thus extended our analysis by examining the effect of reducing intracellular OGT activity on O-GlcNAcylation of N1EGF1–36-MycHis. As expected, OGT esiRNA treatment did not affect the O-GlcNAcylation level of N1EGF1–36-MycHis as compared with control esiRNA-treated cells (Fig. 1E). These results demonstrate that EOGT is the sole enzyme that catalyzes O-GlcNAcylation of Notch1 EGF repeats.

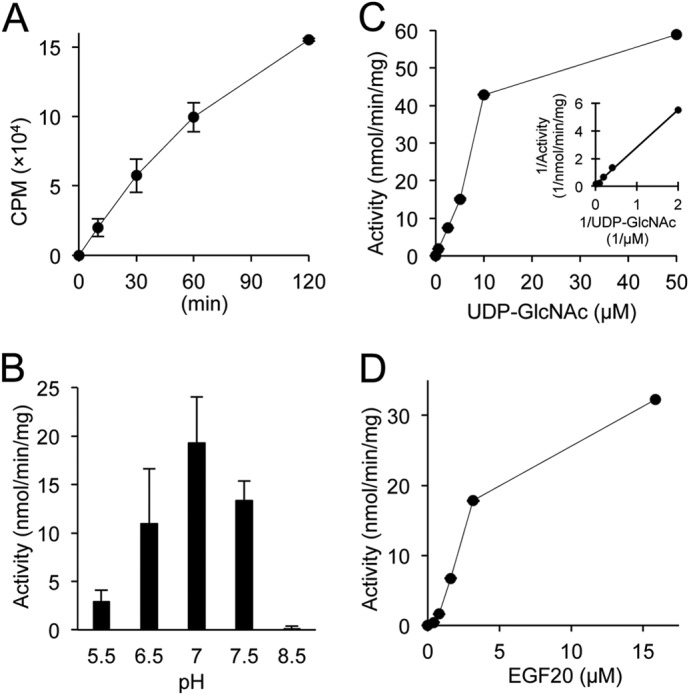

EOGT Enzymatic Properties

Initial experiments examining the enzymatic properties of EOGT showed that EOGT exhibits O-GlcNAc transferase activity specific to folded EGF domains (11, 19). However, there were no kinetic parameters available for EOGT, and thus it was not possible to compare the kinetics of ER-resident EOGT to intracellular OGT and other GlcNAc transferases that localize in the Golgi. Therefore, we performed a detailed characterization of EOGT activity. To obtain purified enzyme, FLAG-EOGT was stably expressed in CHO cells and isolated from cell lysates using anti-M2-agarose. EOGT O-GlcNAc transferase activity was detected in a time- or dose-dependent manner in a buffer containing UDP-[3H]GlcNAc and EGF20 as donor and acceptor substrates, respectively (Fig. 2A and data not shown). To determine the optimum pH for EOGT, O-GlcNAc transferase activities were measured at pH values ranging from 5.5 to 8.5 (Fig. 2B). Pronounced activity was observed at pH 7.0, as compared with that seen at pH 6.5. Moreover, only marginal activity was detected at pH 5.5 or 8.5. These data show that EOGT is more active at a neutral pH, corresponding to the estimated pH in the ER lumen (22).

FIGURE 2.

Enzymatic analysis of EOGT. Enzymatic properties for EOGT were characterized with respect to time (A), pH (B), UDP-GlcNAc concentration (C), and EGF20 concentration (D). A Lineweaver-Burk plot was used to determine kinetic constants (Km, Vmax) for UDP-GlcNAc (inset in C). When not varied, the conditions for the assay were as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Vertical bars represent the range of values obtained from duplicate samples.

Intracellular OGT has been shown to have extremely high affinity for UDP-GlcNAc compared with other GlcNAc transferases in the Golgi (23, 24). To explore whether the kinetic parameters of EOGT are distinct from those of intracellular OGT and Golgi-resident GlcNAc transferases, an activity assay was performed using increasing amounts of UDP-GlcNAc. Lineweaver-Burk analysis of the resulting data yields a Km value of 25 μm and a Vmax of 92 nmol/min/mg (Fig. 2C). EOGT also exhibits a linear increase in activity when increasing amounts of EGF20 were used as an acceptor substrate. However, kinetic constants for EGF20 were not determined in our experiments (Fig. 2D).

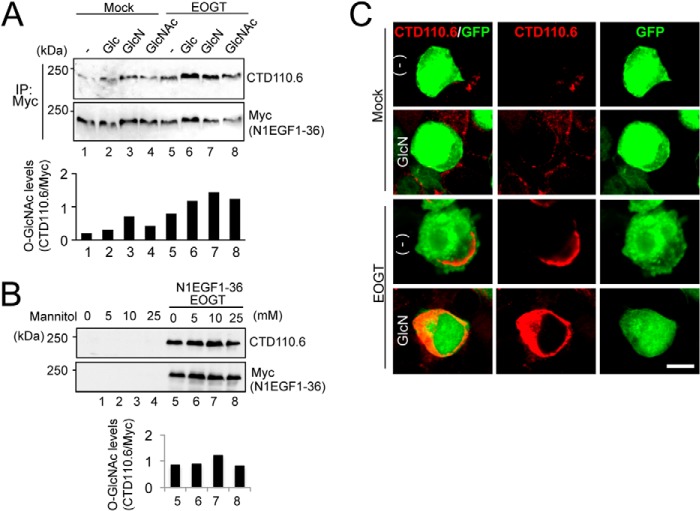

EOGT-catalyzed O-GlcNAcylation Responds to Stimulation of the Hexosamine Biosynthesis Pathway

Glucose and glucosamine are metabolically converted into UDP-GlcNAc via the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (HBP) (9). Previous research revealed that subsets of GlcNAc transferases with low affinity for UDP-GlcNAc respond to HBP stimulation to elevate the GlcNAc branch on N-glycans (25, 26). In Drosophila S2 cells, O-GlcNAcylation by Eogt increases in response to supplementation with glucosamine and GlcNAc. However, the relatively low Km value for UDP-GlcNAc in mouse EOGT led us re-examine whether O-GlcNAcylation of N1EGF1–36-MycHis could similarly be responsive to supplementation with glucose, glucosamine, or N-acetylglucosamine in HEK293T cells. Under culture conditions using low-glucose DMEM, the level of N1EGF1–36-MycHis O-GlcNAcylation was increased by HBP stimulation using glucose, glucosamine, or N-acetylglucosamine (Fig. 3A) in EOGT-transfected cells. The change in O-GlcNAcylation level was not due to the osmotic stress because the supplementation of mannitol did not affect the O-GlcNAcylation of N1EGF1–36-MycHis (Fig. 3B). To confirm the elevation of O-GlcNAcylation levels in the ER, immunostaining with CTD110.6 antibody was performed (Fig. 3C). Upon HBP stimulation, the O-GlcNAc signal in the ER was elevated in EOGT-transfected cells. These results indicate that the luminal UDP-GlcNAc concentration in the ER is controlled in a distinct manner by unique UDP-GlcNAc transporters.

FIGURE 3.

Stimulation of the hexosamine pathway increased O-GlcNAcylation of Notch1 EGF repeats. A, HEK293T cells were transfected to express N1EGF1–36-MycHis alone or together with EOGT. Transfected cells were incubated with 25 mm glucose (Glc), 10 mm glucosamine (GlcN), or 10 mm GlcNAc for 36 h. Myc-tagged N1EGF1–36-MycHis was immunoprecipitated (IP) from lysates using anti-Myc antibody and immunoblotted as indicated. The levels of O-GlcNAc modification on N1EGF1–36-MycHis quantitated by densitometric analyses of immunoblots are shown below. B, HEK293T cells transfected to express N1EGF1–36-MycHis and EOGT or untransfected cells were incubated with various concentrations of mannitol. After 36 h, cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis as indicated. Quantification of O-GlcNAc modification on N1EGF1–36-MycHis is shown below. C, HEK293T cells expressing N1EGF1–36-MycHis alone or together with EOGT were incubated with 10 mm GlcN for 36 h. Immunostaining was performed using anti-O-GlcNAc (CTD110.6; red) antibody. GFP expression indicates transfected cells. Bar, 10 μm.

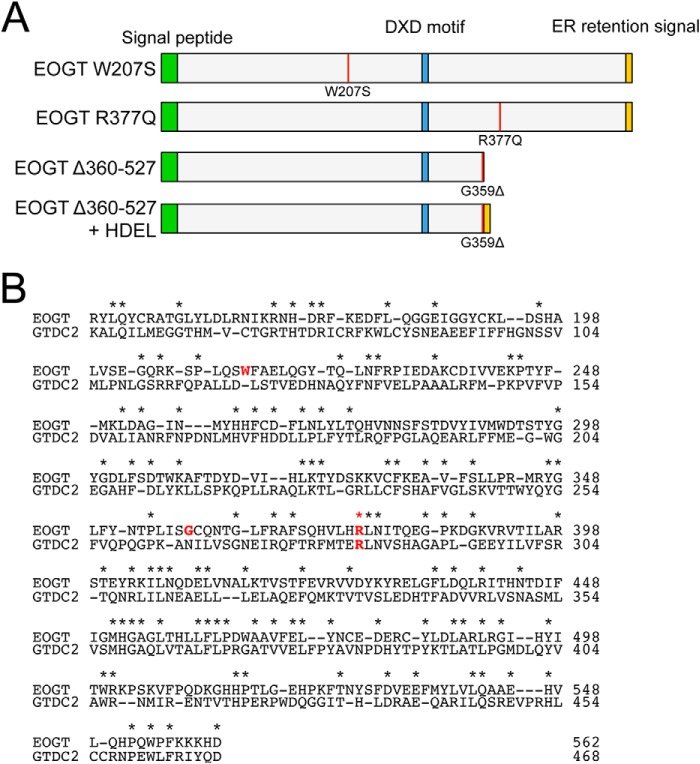

Impaired O-GlcNAcylation in EOGT Mutants Associated with AOS

Recently, the homozygous mutations in EOGT were identified in some patients with AOS (16, 17). To date, three homozygous mutations for EOGT have been reported (Fig. 4). Of these, W207S and R377Q are missense mutations that change amino acid residues absolutely conserved across species from C. elegans to Homo sapiens (16). In contrast, the G359D fs*28 mutation is a 1-bp deletion that causes a frameshift at Gly-359 and subsequent truncation. However, a molecular characterization of these mutations has not yet been performed.

FIGURE 4.

Mouse EOGT mutants associated with AOS. A, schematic representation of the structure of EOGT mutants used in this study. The color code is the same as that in Fig. 1A. The position of each mutation is indicated by a red line. B, the amino acid sequence alignment of mouse EOGT (NP_780522, 149–562 amino acids) and mouse GTDC2/EOGT-L (Q8BW41, 55–468 amino acids). Identical amino acids are shown with asterisks. Amino acid residues corresponding to the mutations found in AOS patients are indicated in red letters.

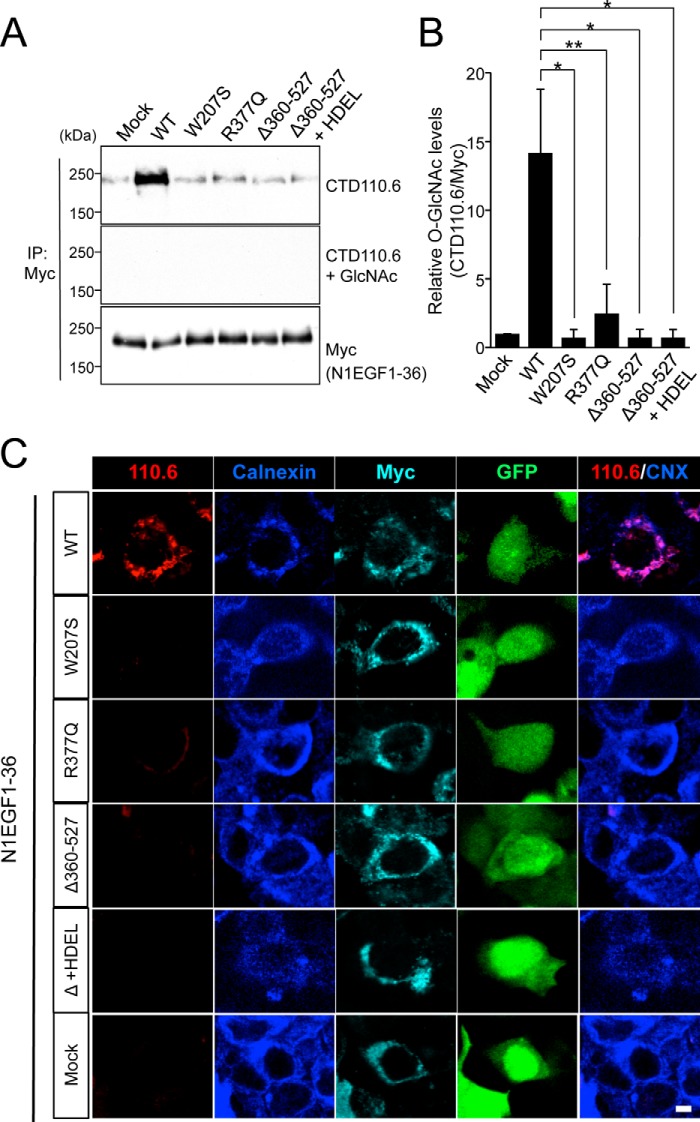

To biochemically characterize the EOGT variants found in AOS, we generated mouse EOGT constructs harboring the same W207S or R377Q mutation found in the AOS patients (Fig. 4A). To characterize the G359D fs*28 mutation, we generated a Δ360–527 construct that mimics the truncated form of EOGT produced by the G359D fs*28 mutation. To analyze O-GlcNAcylation in these mutants, N1EGF1–36-MycHis and the respective EOGT constructs were co-expressed in HEK293T cells. N1EGF1–36-MycHis from the transfected cells was then immunoprecipitated and subsequently analyzed by immunoblotting with CTD110.6 and anti-Myc antibodies (Fig. 5A). The O-GlcNAcylation levels for all EOGT mutants were comparable with that obtained from mock transfectants, whereas wild-type EOGT produced a strong O-GlcNAcylation signal (Fig. 5B). Anti-O-GlcNAc antibody immunoreactivity was specifically competed away in the presence of 0.1 m GlcNAc (Fig. 5A). These results demonstrated that the EOGT mutations reduce enzyme function. Consistent with this immunoblot data, HEK293T cells cotransfected with the EOGT mutants did not have detectable O-GlcNAc staining in the ER (Fig. 5C). These results indicate that defective O-GlcNAcylation in the ER is the molecular basis for AOS.

FIGURE 5.

EOGT mutants exhibit impaired O-GlcNAcylation of Notch1 EGF repeats. HEK293T cells were cotransfected to express N1EGF1–36-MycHis and EOGT constructs. A, N1EGF1–36-MycHis was immunoprecipitated (IP) from lysates using anti-Myc antibody and subjected to immunoblotting with CTD110.6 and anti-Myc antibodies. The specificity of the CTD110.6 antibody immunoreactivity was confirmed by a hapten inhibition test using 0.1 m GlcNAc. B, the levels of O-GlcNAc modification on N1EGF1–36-MycHis quantitated by densitometric analyses of immunoblots represented in A (n = 3; results are shown as mean ± S.D.; *, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.05; unpaired Student's t test). C, immunostaining of HEK293T transfectants with CTD110.6 (red), anti-calnexin (blue), and anti-Myc tag (cyan) antibodies. Bar, 10 μm.

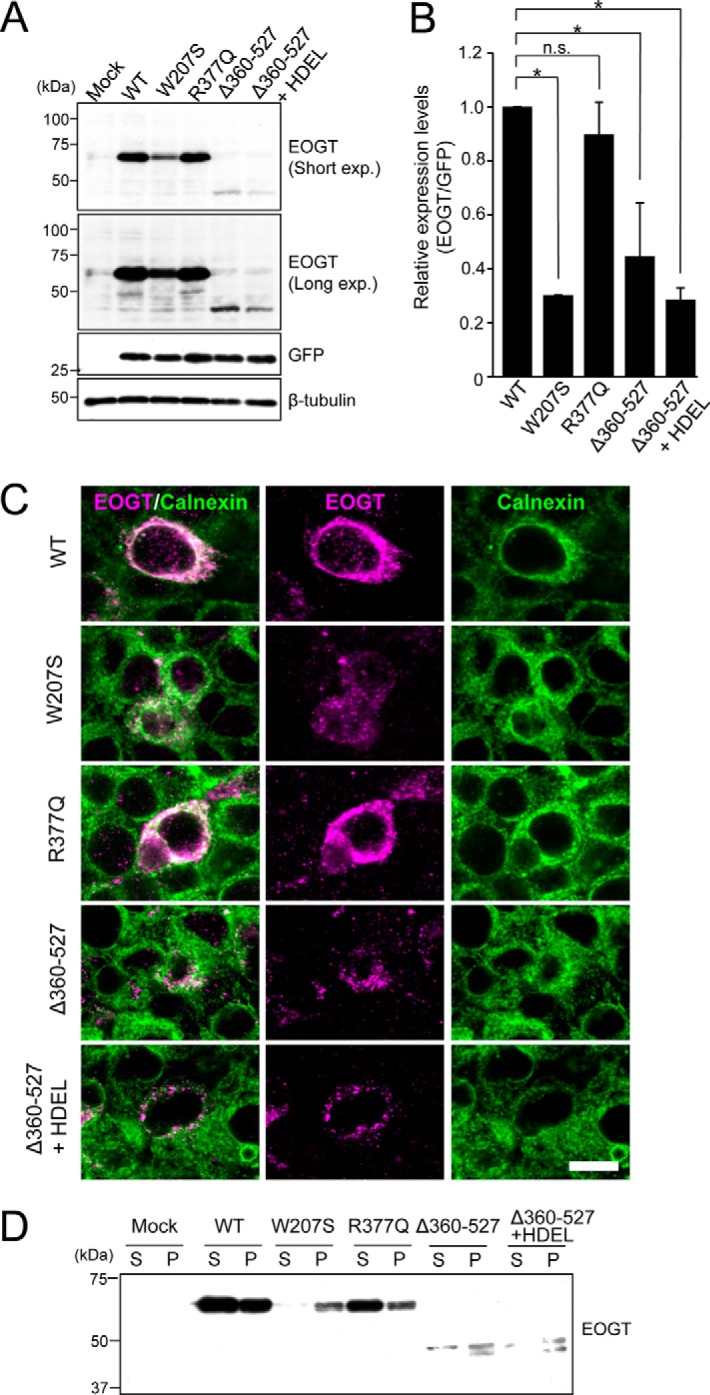

EOGT Mutant Protein Levels and Subcellular Localization

To analyze the precise mechanisms for defective O-GlcNAcylation seen with EOGT mutants, we quantified the expression level of each EOGT construct in HEK293T cells. In the experimental plasmids, the cDNA encoding the respective EOGT mutants is followed by an internal ribosome entry site (termed IRES) and a GFP sequence. Therefore, GFP expression was used as the internal control reference (Fig. 6A). Normalizing the expression levels for the EOGT variants revealed that the W207S mutation decreased expression by ∼70%, whereas the R377Q mutation did not affect the level of protein expression (Fig. 6B). Deletion of the 360–527 sequence also decreased the expression level of EOGT by ∼60%. This decrease is not attributable to the missing ER-retrieval sequence at the carboxyl terminus, because the addition of an HDEL sequence to the Δ360–527 construct failed to recover the protein expression level. These results suggest that protein stability appears to be affected in EOGTW207S and EOGTΔ360–527.

FIGURE 6.

Expression and subcellular localizations of EOGT mutants. A, immunoblot analysis of cell lysates from HEK293T cells transiently expressing wild-type or mutant forms of EOGT. The pSegtag2/EOGT-IRES-GFP constructs allow monitoring of the level of EOGT expression via GFP expression. β-Tubulin was used as a loading control. B, quantification of the EOGT expression level normalized to that of GFP (n = 3; results are shown as mean ± S.D.; *, p < 0.01; n.s., nonspecific; unpaired Student's t test). C, HEK293T cells were transfected to express wild-type EOGT or the indicated EOGT mutants. Immunostaining was performed using anti-EOGT (magenta) and anti-calnexin (green) antibodies. Bar, 10 μm. D, ultracentrifugation of Triton X-100-solubilized EOGT. Note that wild-type EOGT and EOGTR377Q were recovered in the supernatant fraction (S), whereas the majority of EOGTW207S and EOGTΔ360–527 were found in the pellet (P).

To further analyze the molecular mechanisms underlying the defective O-GlcNAcylation seen with the EOGT mutants, we examined the subcellular localization of the EOGT variants. Similar to EOGTWT, EOGTR377Q mainly localized in the ER, as detected by the ER marker calnexin (Fig. 6C). In contrast, the expression level of EOGTW207S in the ER was lower than that of EOGTWT, and immunostaining for EOGTΔ360–527 is hardly detectable in the ER. Moreover, EOGTW207S and EOGTΔ360–527 exhibited a punctate signal that only partially overlapped that of calnexin. Importantly, the addition of an HDEL sequence to EOGTΔ360–527 failed to restore ER localization, suggesting that the altered subcellular localization of EOGTΔ360–527 was not due to lack of the ER-retrieval sequence.

The mislocalization of EOGTW207S and EOGTΔ360–527 mutants prompted us to examine whether AOS-related mutations might affect the solubility of EOGT. Ultracentrifugation of Triton X-100-solubilized EOGT revealed that wild-type EOGT and EOGTR377Q were recovered in the supernatant fraction, whereas the majority of EOGTW207S and EOGTΔ360–527 were found in the pellet (Fig. 6D). These data suggest that W207S and Δ360–527 mutations, but not the R377Q mutation, affect the solubility of EOGT. Taken together, these results indicate that W207S and Δ360–527 mutations affect the stability and/or structure of EOGT, leading to its aberrant subcellular localization.

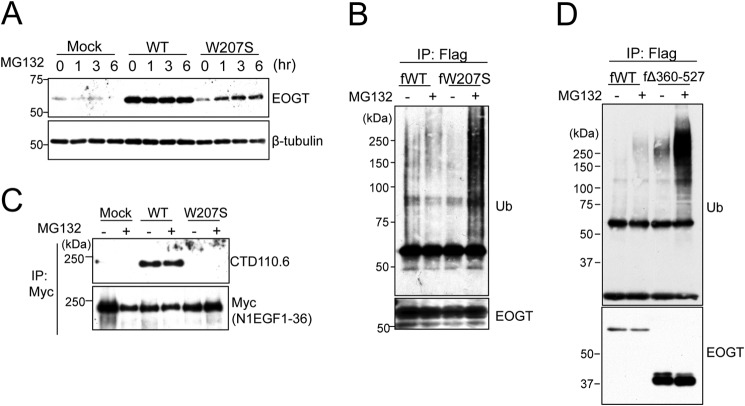

EOGTW207S Is Degraded through the Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway

Next, we attempted to analyze the stability of the EOGTW207S mutant using MG132, an ubiquitin-proteasome inhibitor. As shown in Fig. 7A, the level of EOGTW207S expression was clearly increased after 1 h of MG132 treatment. In contrast, MG132 had no effect on EOGTWT. The sensitivity of EOGTW207S to the ubiquitin-proteasome inhibitor prompted us to ask whether EOGTW207S is modified by ubiquitin (Fig. 7B). In the absence of MG132, ubiquitination of EOGTWT and EOGTW207S was barely observed. In contrast, the ubiquitination level of EOGTW207S was dramatically increased upon MG132 treatment. However, the diminished O-GlcNAcylation of N1EGF1–36-MycHis by EOGTW207S was not recovered by the MG132 treatment (Fig. 7C). These data suggested that the W207S mutation adversely affects protein folding in EOGT, leading to protein degradation and a consequent absence of O-GlcNAcylation in the ER.

FIGURE 7.

The W207S mutant is degraded through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. A, HEK293T cells were transfected to express either EOGTWT or EOGTW207S. At 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with 20 μm MG132 for the indicated time. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. B, HEK293T cells were transfected to express either FLAG-EOGTWT (WT) or FLAG-EOGTW207S (W207S). At 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with 20 μm MG132 for 90 min. Proteins from cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) using an anti-FLAG antibody and immunoblotted as indicated. (C) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with N1EGF1–36-MycHis and EOGT constructs. After 42 h, the transfected cells were added to 20 μm MG132 for 6 h. Proteins from cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using anti-Myc antibody and subjected to immunoblotting with anti-O-GlcNAc (CTD110.6) or anti-Myc antibodies. D, HEK293T cells were transfected to express either FLAG-EOGTWT (fWT) or FLAG-EOGTΔ360–527 (fΔ360–527). At 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with 20 μm MG132 for 90 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using anti-FLAG antibody-conjugated beads and immunoblotted as indicated.

We then asked whether EOGTΔ360–527 is similarly degraded through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Although EOGTΔ360–527 was modified by ubiquitin in the presence of MG132, the expression level of EOGTΔ360–527 appeared to be unaffected (Fig. 7D), suggesting that molecular mechanisms unrelated to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway would contribute to the decreased expression level of EOGTΔ360–527.

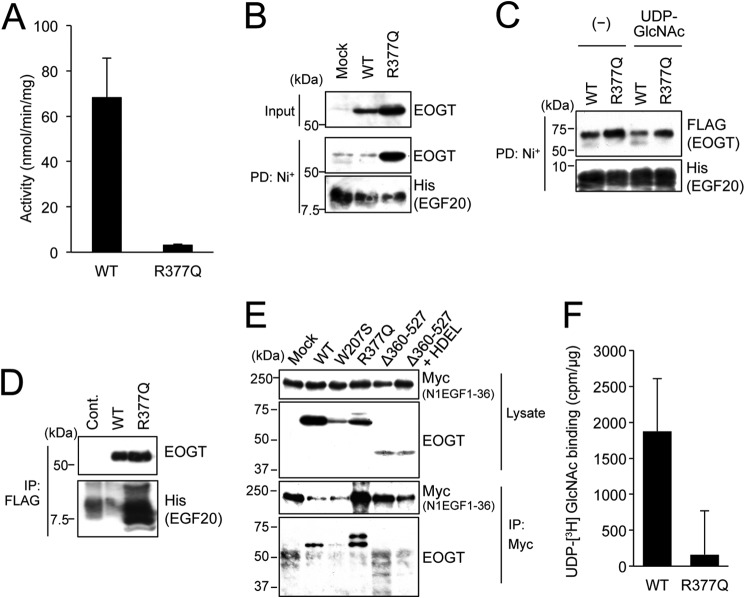

Characterization of the Enzymatic Properties of EOGTR377Q

To characterize the enzyme activity of EOGTR377Q, FLAG-EOGTR377Q was stably expressed in CHO cells and purified to homogeneity. As shown in Fig. 8A, enzyme activity was not detectable in the R377Q mutants.

FIGURE 8.

The R377Q mutant exhibits lack of enzymatic activity and impaired UDP-GlcNAc binding. A, in vitro O-GlcNAc transferase assay was used to measure the enzymatic activity of the R377Q mutant. B, recombinant Notch EGF20:His was incubated with cell lysates from HEK293T mock transfectants or transfectants expressing EOGTWT or EOGTR377Q, affinity purified from the mixtures using Ni+ beads, and subjected to immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. C, purified EOGTWT or EOGTR377Q was incubated with recombinant Notch EGF20:His with or without UDP-GlcNAc, affinity purified, and subjected to immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. D, Notch EGF20:His was incubated with cell lysates from CHO cells (Cont) or stable transfectants expressing FLAG-EOGTWT or FLAG-EOGTR377Q, immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody-conjugated beads, and subjected to immunoblotting as indicated. E, HEK293T cells were cotransfected to express N1EGF1–36-MycHis and the indicated EOGT constructs. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc tag antibody, and N1EGF1–36-MycHis·EOGT complexes were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. F, lysates from HEK293T cells expressing FLAG-EOGTWT or FLAG-EOGTR377Q were incubated with UDP-[3H]GlcNAc and EGF20 on ice and immunoprecipitated using anti-FLAG antibody, after which the level of radioactivity was measured. Lysates from mock transfectants were similarly processed for use as a control. Vertical bars represent the range of values obtained from duplicate samples.

To address the effect of the R377Q mutation on the enzymatic properties of EOGT, binding capacities of EOGTR377Q to acceptor substrates and UDP-GlcNAc were analyzed. For the assay examining the binding of EOGT to EGF20, lysates from HEK293T cells transfected to express either EOGTWT or EOGTR377Q were mixed with recombinant EGF20, and the subsequent EOGT·EGF20 complexes were recovered from the mixtures using Ni+ beads. Unexpectedly, the amount of EGF20 coprecipitated with EOGTR377Q was higher than that coprecipitated with EOGTWT (Fig. 8B).

To confirm this result, purified EOGTWT or EOGTR377Q was mixed with recombinant EGF20 in the presence or absence of UDP-GlcNAc, affinity purified, and analyzed as above. The amount of EGF20 that copurified with EOGTR377Q was higher than the amount that copurified with EOGTWT. Inclusion of UDP-GlcNAc in the mixture markedly decreased the EGF20-EOGTWT interaction, but did not obviously affect the EGF20-EOGTR377Q interaction (Fig. 8C). These results demonstrate that the R377Q mutation does not affect acceptor substrate binding in EOGT.

Based on these results, a reverse-binding experiment was conducted using lysates from CHO cells stably expressing either FLAG-EOGTWT or FLAG-EOGTR377Q. After purification on the M2 anti-FLAG resin, recombinant EGF20 was supplemented in the presence of UDP-GlcNAc, and the EOGT·EGF20 complexes were recovered from the mixtures. As expected, physical interaction between EOGTR377Q and EGF20 was detected (Fig. 8D). We further performed a binding analysis at the cellular level (Fig. 8E). Co-immunoprecipitation of N1EGF1–36-MycHis with wild-type or mutant forms of EOGT revealed that EOGTR377Q and, to a lesser degree, wild-type EOGT were bound to N1EGF1–36-MycHis. No evident binding between N1EGF1–36-MycHis and EOGTW207S or EOGTΔ360–527 was observed.

The apparent increase in the binding affinity of EOGTR377Q for acceptor substrates could be due to a decreased affinity for UDP-GlcNAc, which would result in the stabilization of an acceptor substrate-enzyme complex. However, the lack of enzymatic activity for EOGTR377Q hampered our attempt to directly measure the Km value for UDP-GlcNAc. As an alternative approach, either FLAG-EOGTWT or FLAG-EOGTR377Q was incubated with tritium-labeled UDP-GlcNAc (Fig. 8F). After incubation for 30 min on ice, the proteins were immunoprecipitated from the mixtures using anti-FLAG beads. Although complexes with UDP-[3H]GlcNAc were detected in both cases, the signal obtained with FLAG-EOGTR377Q was lower than that obtained with FLAG-EOGTWT. These results indicate that EOGTR377Q is defective in binding with UDP-GlcNAc; this defect may contribute, at least in part, to the lack of enzymatic activity seen in the mutant EOGT.

DISCUSSION

AOS is a rare congenital disorder characterized by aplasia cutis congenital and terminal transverse limb defects. AOS is genetically heterogeneous, and the molecular pathology appears complex. Until now, DOCK6 (27), ARHGAP31 (28), RBPJ (29), EOGT, and Notch1 (30) have recently been reported as AOS-causative genes. However, the molecular consequences of EOGT mutations have not been characterized. In this study, we demonstrated that EOGT mutations associated with AOS resulted in the loss of the ability of EOGT to O-GlcNAcylate EGF domains in the ER. Importantly, even though EOGTR377Q is catalytically inactive, it retains the ability to bind an acceptor substrate. The unique enzymatic properties of EOGTR377Q exclude the possibility of a glycosyltransferase-independent function of EOGT in the pathogenesis of AOS. Our findings show that impaired EOGT glycosyltransferase activity and defective O-GlcNAcylation in the ER constitutes the molecular basis for AOS.

Although EOGT and intracellular OGT both catalyze protein O-GlcNAcylation, EOGT has no sequence similarity with intracellular OGT. The EOGT-related gene GTDC2 encodes O-mannose β1,4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase, which acts on α-dystroglycan (31–34). Interestingly, arginine at position 377 is conserved between EOGT and GTDC2 (Fig. 4B). Given that both GTDC2 and EOGT are involved in GlcNAc modification in the ER and that Arg-377 in EOGT is conserved in GTDC2, the arginine residue may be important in the recognition of UDP-GlcNAc by EOGT and GTDC2.

It has been reported that the respective GlcNAc transferases exhibit different affinity for UDP-GlcNAc. Intracellular OGT has been shown to exhibit the highest affinity for UDP-GlcNAc among all GlcNAc transferases, which have Km values ranging from 545 nm to 8.5 μm (23, 24). In contrast, Golgi-resident GlcNAc transferases exhibit much higher Km values than OGT. For example, the Km value of UDP-GlcNAc for Mgat1 is 40 μm, and for Mgat2 is 0.96 mm (35). Even higher Km values for UDP-GlcNAc have been reported for Mgat4, with 5.0 mm, and Mgat5, with 11.0 mm (25, 35). EGF repeats in Notch receptors are also modified with O-fucose, which is further modified with β1,3-linked GlcNAc by Lfng, Rfng, and Mfng, exhibiting Km values of 78, 53.6, and 196 μm, respectively (36). Our finding of a Km value of EOGT for UDP-GlcNAc (25 μm) suggested that the affinity of EOGT for UDP-GlcNAc is higher than that of most GlcNAc transferases except OGT. In the Golgi, Mgat4 and Mgat5 show lower affinities for UDP-GlcNAc, and their activities are limited by UDP-GlcNAc concentrations (26, 35). Thus, branching of N-glycans by Mgat4 and Mgat5 is stimulated by a hexosamine flux that leads to UDP-GlcNAc production (26). Paradoxically, our data showed that O-GlcNAcylation of Notch 1 EGF repeats by EOGT is also stimulated by hexosamine treatment. The Golgi concentration of UDP-GlcNAc was calculated to be ∼1.5 mm, 15-fold higher than that of cytoplasmic UDP-GlcNAc (37). Given that EOGT has a high affinity for UDP-GlcNAc but is still responsive to hexosamine flux, the concentration of UDP-GlcNAc in the ER would be maintained at a lower level than that in the Golgi.

Nucleotide sugars are transported from the cytosol to the ER and the Golgi by the nucleotide-sugar transporters, highly conserved hydrophobic proteins with multiple transmembrane domains that are part of the solute carrier family 35 (SLC35) (38, 39). Of these, SLC35A3 (40–42) and SLC35D2 (43, 44) are reported to be Golgi-resident UDP-GlcNAc transporters. In contrast, SLC35B4 has been shown to transport UDP-Xyl and UDP-GlcNAc (45), but the reports of the subcellular localization of this protein are somewhat inconsistent. Although an initial report suggested that SLC35B4 localizes in the Golgi (45), a more recent report suggests that it localizes in the ER (46). These conflicting results could be due to the different cell types used in the two studies. SLC35D1 is also reported to be an ER nucleotide-sugar transporter that transports UDP-GlcNAc, UDP-GalNAc, and UDP-GlcUA (47). It would be interesting to determine whether SLC35B4, SLC35D1, and/or a yet unidentified transporter are responsible for O-GlcNAcylation by EOGT in the ER.

Currently, the molecular mechanisms of how impaired O-GlcNAcylation leads to the anomalies observed in AOS remain unknown. Given that loss of function mutation for DOCK6 (27) and gain of function mutation for ARHGAP31 (28) cause AOS, O-GlcNAcylation might be involved in the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton (16). Alternatively, EOGT might be required for optimal Notch signaling, as a heterozygous mutation for RBPJ, which encodes a transcriptional factor involved in Notch signaling, also causes AOS (29). In this regard, it would be interesting to hypothesize that O-GlcNAc might regulate Notch receptor function, as it does with other O-glycans, including O-fucose and O-glucose glycans (48–55). However, no evidence for such a conclusion is provided by the genetic studies in Drosophila (11, 12). Eogt mutants in Drosophila show phenotypes related to dumpy (dp). Dumpy is O-GlcNAcylated by EOGT, and Eogt and dp genetically interact to create the dp phenotype, which includes wing blistering. Although Eogt similarly interacts with the components for the Notch signaling pathway in wing blistering (12), the effect of EOGT on the Notch signaling pathway could be indirect, because Notch signaling per se is involved in the regulation of pyrimidine synthesis, which is likely to promote wing blistering (12). As multiple substrates may be modified by EOGT, a careful examination of EOGT function with respect to Notch receptors and other glycoproteins should be conducted to elucidate the biological function of O-GlcNAcylation in the ER and its contribution to pathological processes.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to P. Stanley, Y. Sakaidani, and B. Pawel for their kind support and comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-aid for Challenging Exploratory Research (to T. O.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, a Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (to T. O., H. Y., and K. K.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, and a Grant-in-aid from the Takeda Foundation and the Astellas Foundation (to T. O.).

- OGT

- O-GlcNAc transferase

- AOS

- Adams-Oliver syndrome

- EOGT

- EGF O-GlcNAc transferase

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- N1EGF1–36-MycHis

- Myc-His-tagged mouse Notch1 EGF repeats

- O-GlcNAc

- O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine

- esiRNA

- endonuclease-prepared small interfering RNA

- PNGase F

- peptide:N-glycosidase F

- HBP

- hexosamine biosynthesis pathway

- IRES

- internal ribosome entry site.

REFERENCES

- 1. Slawson C., Housley M. P., Hart G. W. (2006) O-GlcNAc cycling: how a single sugar post-translational modification is changing the way we think about signaling networks. J. Cell. Biochem. 97, 71–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hart G. W., Slawson C., Ramirez-Correa G., Lagerlof O. (2011) Cross talk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: roles in signaling, transcription, and chronic disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 80, 825–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ranuncolo S. M., Ghosh S., Hanover J. A., Hart G. W., Lewis B. A. (2012) Evidence of the involvement of O-GlcNAc-modified human RNA polymerase II CTD in transcription in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 23549–23561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kizuka Y., Kitazume S., Okahara K., Villagra A., Sotomayor E. M., Taniguchi N. (2014) Epigenetic regulation of a brain-specific glycosyltransferase N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase-IX (GnT-IX) by specific chromatin modifiers. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 11253–11261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yang X., Ongusaha P. P., Miles P. D., Havstad J. C., Zhang F., So W. V., Kudlow J. E., Michell R. H., Olefsky J. M., Field S. J., Evans R. M. (2008) Phosphoinositide signalling links O-GlcNAc transferase to insulin resistance. Nature 451, 964–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ogawa M., Mizofuchi H., Kobayashi Y., Tsuzuki G., Yamamoto M., Wada S., Kamemura K. (2012) Terminal differentiation program of skeletal myogenesis is negatively regulated by O-GlcNAc glycosylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1820, 24–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miura Y., Sakurai Y., Endo T. (2012) O-GlcNAc modification affects the ATM-mediated DNA damage response. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1820, 1678–1685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vosseller K., Wells L., Lane M. D., Hart G. W. (2002) Elevated nucleocytoplasmic glycosylation by O-GlcNAc results in insulin resistance associated with defects in Akt activation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 5313–5318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hanover J. A., Krause M. W., Love D. C. (2010) The hexosamine signaling pathway: O-GlcNAc cycling in feast or famine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1800, 80–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Matsuura A., Ito M., Sakaidani Y., Kondo T., Murakami K., Furukawa K., Nadano D., Matsuda T., Okajima T. (2008) O-Linked N-acetylglucosamine is present on the extracellular domain of notch receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35486–35495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sakaidani Y., Nomura T., Matsuura A., Ito M., Suzuki E., Murakami K., Nadano D., Matsuda T., Furukawa K., Okajima T. (2011) O-Linked-N-acetylglucosamine on extracellular protein domains mediates epithelial cell-matrix interactions. Nat. Commun. 2, 583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Müller R., Jenny A., Stanley P. (2013) The EGF repeat-specific O-GlcNAc-transferase Eogt interacts with notch signaling and pyrimidine metabolism pathways in Drosophila. PLoS One 8, e62835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alfaro J. F., Gong C. X., Monroe M. E., Aldrich J. T., Clauss T. R., Purvine S. O., Wang Z., Camp D. G., 2nd, Shabanowitz J., Stanley P., Hart G. W., Hunt D. F., Yang F., Smith R. D. (2012) Tandem mass spectrometry identifies many mouse brain O-GlcNAcylated proteins including EGF domain-specific O-GlcNAc transferase targets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 7280–7285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hoffmann B. R., Liu Y., Mosher D. F. (2012) Modification of EGF-like module 1 of thrombospondin-1, an animal extracellular protein, by O-linked N-acetylglucosamine. PLoS One 7, e32762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ogawa M., Furukawa K., Okajima T. (2014) Extracellular O-GlcNAc: its biology and relationship to human disease. World J. Biol. Chem. 5, 224–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shaheen R., Aglan M., Keppler-Noreuil K., Faqeih E., Ansari S., Horton K., Ashour A., Zaki M. S., Al-Zahrani F., Cueto-González A. M., Abdel-Salam G., Temtamy S., Alkuraya F. S. (2013) Mutations in EOGT confirm the genetic heterogeneity of autosomal-recessive Adams-Oliver syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 92, 598–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cohen I., Silberstein E., Perez Y., Landau D., Elbedour K., Langer Y., Kadir R., Volodarsky M., Sivan S., Narkis G., Birk O. S. (2014) Autosomal recessive Adams-Oliver syndrome caused by homozygous mutation in EOGT, encoding an EGF domain-specific O-GlcNAc transferase. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 22, 374–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hou X., Tashima Y., Stanley P. (2012) Galactose differentially modulates lunatic and manic fringe effects on Delta1-induced NOTCH signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 474–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sakaidani Y., Ichiyanagi N., Saito C., Nomura T., Ito M., Nishio Y., Nadano D., Matsuda T., Furukawa K., Okajima T. (2012) O-Linked N-acetylglucosamine modification of mammalian Notch receptors by an atypical O-GlcNAc transferase Eogt1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 419, 14–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sakaidani Y., Furukawa K., Okajima T. (2010) O-GlcNAc modification of the extracellular domain of Notch receptors. Methods Enzymol. 480, 355–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tashima Y., Stanley P. (2014) Antibodies that detect O-GlcNAc on the extracellular domain of cell surface glycoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 11132–11142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim J. H., Johannes L., Goud B., Antony C., Lingwood C. A., Daneman R., Grinstein S. (1998) Noninvasive measurement of the pH of the endoplasmic reticulum at rest and during calcium release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 2997–3002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haltiwanger R. S., Blomberg M. A., Hart G. W. (1992) Glycosylation of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins. Purification and characterization of a uridine diphospho-N-acetylglucosamine:polypeptide β-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 9005–9013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ma X., Liu P., Yan H., Sun H., Liu X., Zhou F., Li L., Chen Y., Muthana M. M., Chen X., Wang P. G., Zhang L. (2013) Substrate specificity provides insights into the sugar donor recognition mechanism of O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT). PLoS One 8, e63452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sasai K., Ikeda Y., Fujii T., Tsuda T., Taniguchi N. (2002) UDP-GlcNAc concentration is an important factor in the biosynthesis of β1,6-branched oligosaccharides: regulation based on the kinetic properties of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V. Glycobiology 12, 119–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lau K. S., Partridge E. A., Grigorian A., Silvescu C. I., Reinhold V. N., Demetriou M., Dennis J. W. (2007) Complex N-glycan number and degree of branching cooperate to regulate cell proliferation and differentiation. Cell 129, 123–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shaheen R., Faqeih E., Sunker A., Morsy H., Al-Sheddi T., Shamseldin H. E., Adly N., Hashem M., Alkuraya F. S. (2011) Recessive mutations in DOCK6, encoding the guanidine nucleotide exchange factor DOCK6, lead to abnormal actin cytoskeleton organization and Adams-Oliver syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 89, 328–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Southgate L., Machado R. D., Snape K. M., Primeau M., Dafou D., Ruddy D. M., Branney P. A., Fisher M., Lee G. J., Simpson M. A., He Y., Bradshaw T. Y., Blaumeiser B., Winship W. S., Reardon W., Maher E. R., FitzPatrick D. R., Wuyts W., Zenker M., Lamarche-Vane N., Trembath R. C. (2011) Gain-of-function mutations of ARHGAP31, a Cdc42/Rac1 GTPase regulator, cause syndromic cutis aplasia and limb anomalies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88, 574–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hassed S. J., Wiley G. B., Wang S., Lee J.-Y., Li S., Xu W., Zhao Z. J., Mulvihill J. J., Robertson J., Warner J., Gaffney P. M. (2012) RBPJ mutations identified in two families affected by Adams-Oliver syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 91, 391–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stittrich A. B., Lehman A., Bodian D. L., Ashworth J., Zong Z., Li H., Lam P., Khromykh A., Iyer R. K., Vockley J. G., Baveja R., Silva E. S., Dixon J., Leon E. L., Solomon B. D., Glusman G., Niederhuber J. E., Roach J. C., Patel M. S. (2014) Mutations in NOTCH1 cause Adams-Oliver syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 95, 275–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yoshida-Moriguchi T., Willer T., Anderson M. E., Venzke D., Whyte T., Muntoni F., Lee H., Nelson S. F., Yu L., Campbell K. P. (2013) SGK196 is a glycosylation-specific O-mannose kinase required for dystroglycan function. Science 341, 896–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Manzini M. C., Tambunan D. E., Hill R. S., Yu T. W., Maynard T. M., Heinzen E. L., Shianna K. V., Stevens C. R., Partlow J. N., Barry B. J., Rodriguez J., Gupta V. A., Al-Qudah A. K., Eyaid W. M., Friedman J. M., Salih M. A., Clark R., Moroni I., Mora M., Beggs A. H., Gabriel S. B., Walsh C. A. (2012) Exome sequencing and functional validation in zebrafish identify GTDC2 mutations as a cause of Walker-Warburg syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 91, 541–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ogawa M., Nakamura N., Nakayama Y., Kurosaka A., Manya H., Kanagawa M., Endo T., Furukawa K., Okajima T. (2013) GTDC2 modifies O-mannosylated α-dystroglycan in the endoplasmic reticulum to generate N-acetylglucosamine epitopes reactive with CTD110.6 antibody. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 440, 88–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yagi H., Nakagawa N., Saito T., Kiyonari H., Abe T., Toda T., Wu S. W., Khoo K. H., Oka S., Kato K. (2013) AGO61-dependent GlcNAc modification primes the formation of functional glycans on α-dystroglycan. Sci. Rep. 3, 3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dennis J. W., Nabi I. R., Demetriou M. (2009) Metabolism, cell surface organization, and disease. Cell 139, 1229–1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rampal R., Li A. S., Moloney D. J., Georgiou S. A., Luther K. B., Nita-Lazar A., Haltiwanger R. S. (2005) Lunatic fringe, manic fringe, and radical fringe recognize similar specificity determinants in O-fucosylated epidermal growth factor-like repeats. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42454–42463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Waldman B. C., Rudnick G. (1990) UDP-GlcNAc transport across the Golgi membrane: electroneutral exchange for dianionic UMP. Biochemistry 29, 44–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Csala M., Marcolongo P., Lizák B., Senesi S., Margittai E., Fulceri R., Magyar J. E., Benedetti A., Bánhegyi G. (2007) Transport and transporters in the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1768, 1325–1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Song Z. (2013) Roles of the nucleotide sugar transporters (SLC35 family) in health and disease. Mol. Aspects Med. 34, 590–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Guillen E., Abeijon C., Hirschberg C. B. (1998) Mammalian Golgi apparatus UDP-N-acetylglucosamine transporter: molecular cloning by phenotypic correction of a yeast mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 7888–7892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Maszczak-Seneczko D., Sosicka P., Olczak T., Jakimowicz P., Majkowski M., Olczak M. (2013) UDP-N-acetylglucosamine transporter (SLC35A3) regulates biosynthesis of highly branched N-glycans and keratan sulfate. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 21850–21860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ishida N., Yoshioka S., Chiba Y., Takeuchi M., Kawakita M. (1999) Molecular cloning and functional expression of the human Golgi UDP-N-acetylglucosamine transporter. J. Biochem. 126, 68–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Suda T., Kamiyama S., Suzuki M., Kikuchi N., Nakayama K., Narimatsu H., Jigami Y., Aoki T., Nishihara S. (2004) Molecular cloning and characterization of a human multisubstrate specific nucleotide-sugar transporter homologous to Drosophila fringe connection. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26469–26474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ishida N., Kuba T., Aoki K., Miyatake S., Kawakita M., Sanai Y. (2005) Identification and characterization of human Golgi nucleotide sugar transporter SLC35D2, a novel member of the SLC35 nucleotide sugar transporter family. Genomics 85, 106–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ashikov A., Routier F., Fuhlrott J., Helmus Y., Wild M., Gerardy-Schahn R., Bakker H. (2005) The human solute carrier gene SLC35B4 encodes a bifunctional nucleotide sugar transporter with specificity for UDP-xylose and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 27230–27235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maszczak-Seneczko D., Olczak T., Olczak M. (2011) Subcellular localization of UDP-GlcNAc, UDP-Gal and SLC35B4 transporters. Acta Biochim. Pol. 58, 413–419 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hiraoka S., Furuichi T., Nishimura G., Shibata S., Yanagishita M., Rimoin D. L., Superti-Furga A., Nikkels P. G., Ogawa M., Katsuyama K. (2007) Nucleotide-sugar transporter SLC35D1 is critical to chondroitin sulfate synthesis in cartilage and skeletal development in mouse and human. Nat. Med. 13, 1363–1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Takeuchi H., Kantharia J., Sethi M. K., Bakker H., Haltiwanger R. S. (2012) Site-specific O-glucosylation of the epidermal growth factor-like (EGF) repeats of Notch: efficiency of glycosylation is affected by proper folding and amino acid sequence of individual EGF repeats. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 33934–33944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stahl M., Uemura K., Ge C., Shi S., Tashima Y., Stanley P. (2008) Roles of Pofut1 and O-fucose in mammalian Notch signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13638–13651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sasamura T., Sasaki N., Miyashita F., Nakao S., Ishikawa H. O., Ito M., Kitagawa M., Harigaya K., Spana E., Bilder D. (2003) neurotic, a novel maternal neurogenic gene, encodes an O-fucosyltransferase that is essential for Notch-Delta interactions. Development 130, 4785–4795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rampal R., Arboleda-Velasquez J. F., Nita-Lazar A., Kosik K. S., Haltiwanger R. S. (2005) Highly conserved O-fucose sites have distinct effects on Notch1 function. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 32133–32140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lee T. V., Sethi M. K., Leonardi J., Rana N. A., Buettner F. F., Haltiwanger R. S., Bakker H., Jafar-Nejad H. (2013) Negative regulation of notch signaling by xylose. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Okajima T., Irvine K. D. (2002) Regulation of notch signaling by O-linked fucose. Cell 111, 893–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Acar M., Jafar-Nejad H., Takeuchi H., Rajan A., Ibrani D., Rana N. A., Pan H., Haltiwanger R. S., Bellen H. J. (2008) Rumi is a CAP10 domain glycosyltransferase that modifies Notch and is required for Notch signaling. Cell 132, 247–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Taylor P., Takeuchi H., Sheppard D., Chillakuri C., Lea S. M., Haltiwanger R. S., Handford P. A. (2014) Fringe-mediated extension of O-linked fucose in the ligand-binding region of Notch1 increases binding to mammalian Notch ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 7290–7295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]