Abstract

Objectives

To systematically review the evidence for the impact of study design and setting on the interpretation of tuberculosis (TB) transmission using clustering derived from Mycobacterial Interspersed Repetitive Units-Variable Number Tandem Repeats (MIRU-VNTR) strain typing.

Data sources

MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINHAL, Web of Science and Scopus were searched for articles published before 21st October 2014.

Review methods

Studies in humans that reported the proportion of clustering of TB isolates by MIRU-VNTR were included in the analysis. Univariable meta-regression analyses were conducted to assess the influence of study design and setting on the proportion of clustering.

Results

The search identified 27 eligible articles reporting clustering between 0% and 63%. The number of MIRU-VNTR loci typed, requiring consent to type patient isolates (as a proxy for sampling fraction), the TB incidence and the maximum cluster size explained 14%, 14%, 27% and 48% of between-study variation, respectively, and had a significant association with the proportion of clustering.

Conclusions

Although MIRU-VNTR typing is being adopted worldwide there is a paucity of data on how study design and setting may influence estimates of clustering. We have highlighted study design variables for consideration in the design and interpretation of future studies.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, MOLECULAR BIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a timely evaluation of the impact of study design on estimates of tuberculosis clustering using Mycobacterial Interspersed Repetitive Units-Variable Number Tandem Repeats strain typing because it has been incorporated into national typing services globally.

The strength of this meta-analysis was limited by the lack of detail reported by the included studies, highlighting the need for better quality reporting in primary studies.

We have shown that the proportion of clustering derived from MIRU-VTNR typing is influenced by the number of loci typed, whether consent is required to type isolates, TB incidence in the study setting, and the maximum cluster size, highlighting these as important considerations in the design and interpretation of future studies.

Introduction

The introduction of molecular typing methods has improved our understanding of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) transmission and has changed local and national control policies.1–5 The proportion of cases that are clustered is often used to estimate the amount of ongoing transmission within the population, based on the assumption that cases with indistinguishable strain types are part of a chain of transmission. TB molecular typing methodology is changing rapidly and it is important that we better understand how to interpret the outputs and thus act.

TB molecular typing methods include Spoligotyping,6 insertion sequence 6110 (IS6110) restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis (the recent gold standard),7 Mycobacterial Interspersed Repetitive Units-Variable Number Tandem Repeats (MIRU-VNTR) typing,8 and whole genome sequencing.9–11 Published reviews have identified factors that might influence or bias clustering by IS6110 RFLP.12 13 No study has repeated this analysis using more up-to-date typing methods, which is important for understanding of the epidemiology of TB and to shape the application of molecular typing to improve TB control.

Published meta-analyses and modelling studies using IS6110 RFLP data show that the proportion of clustering observed can be affected by (1) study design (affecting the proportion of eligible cases that are included in the study); (2) features of the typing method (such as the ability to type isolates with low copy numbers); and (3) study setting (such as characteristics of the study population). For example, the proportion of clustering increases when the fraction of the total data sampled increases13–15 and when study duration increases.16

MIRU-VNTR is currently the preferred method of molecular typing,17–21 and can be used together with Spoligotyping.8 Relative to IS6110 RFLP, MIRU-VNTR does not have to exclude isolates with a low IS6110 copy number, has a faster turnaround time, is high throughput and the numeric strain types are more easily compared. MIRU-VNTR strain typing is increasingly being adopted worldwide,1 22–27 yet unlike IS6110 RFLP, the evidence for the interpretation of the findings such as the impact of study design and setting on clustering have not been reviewed. Although the two typing methods have been shown to have a similar discriminatory value, the markers evolve independently and at different rates, resulting in a difference in clustering between the two methods.28 This suggests that there could be differences in the way study design, typing method and setting affects clustering by the two methods. We conducted a systematic review to assess the evidence for the impact of study design and setting on the interpretation of TB transmission using clustering derived from MIRU-VNTR strain typing—as has been shown using IS6110 RFLP typing.

Methods

Five electronic databases were searched (EMBASE, ISI Web of Science, CINHAL, Scopus and Medline (Ovid)) up to 20 October 2014. The search strategy combined the following terms with Boolean operators: Tuberculosis, strain typing, and transmission (see online supplementary appendix 1). The search was limited to studies using the standard MIRU-VNTR method,8 in humans only, and in English.

All titles and abstracts from each of the searches were examined. The full text of each paper was obtained and reviewed if the study reported MIRU-VNTR strain typing of M. tuberculosis complex isolates with at least 15 of the standardised 24 loci (Exact Tandem Repeat A, B, C, D, E; MIRU 2, 10, 16, 20, 23, 24, 26, 27, 39, 40; VNTR 424, 1955, 2163b, 2347, 2401, 3171, 3690, 4052, 4156).8 29 30

Studies using fewer than 15 loci were not included because the level of discrimination is inadequate for epidemiological use (n=121).8 Studies that used loci different to the standardised 15 and 24 set were not included in the analysis in order to reduce the heterogeneity between studies (n=19). All publication types were included in this first screen to ensure that no relevant data were missed.

Reviews, letters, editorials, outbreaks or case reports (n=103) were excluded in the second screen. Studies that used incomplete sampling (eg, random samples, studies using subsets of populations such as multidrug-resistant patients; n=47) and studies that had a sample size of less than 50 (n=4) were also excluded.

A reviewer (JM) extracted the following data items from all included studies using a form developed in Excel (Microsoft 2010): publication details (year, authors, study country), study details (study duration, loci typed, secondary typing method, study population, whether participant consent was required (a characteristic of the study design that was used as proxy for sampling fraction, assuming that where consent was required the sampling fraction was low)), the number of clustered and unique isolates and the covariates of interest: the maximum size of clusters; the proportion of clusters containing two cases; the proportion of the population that was culture positive; the proportion of culture positive isolates typed; risk factors for clustering; and the Hunter Gaston Discriminatory Index (HGDI)31). IA extracted data from 10% of the papers for external validity, disagreements were discussed and a consensus agreed on.

The main outcome measure—the proportion of TB isolates clustered by MIRU-VNTR strain typing—was calculated as the number of clustered isolates/number of clustered+unique isolates. Where there were uncertainties JM consulted with IA.

Authors were contacted if TB incidence rate was not reported. Where no response was received WHO country estimates of TB incidence for the study year were used.32 As so few studies reported the proportion coinfected with TB/HIV, these estimates for the study country were taken from an European Union-wide survey and WHO country profiles.33 34 Owing to poor recording of the sampling fraction (the number of isolates typed/the total number of culture positive TB cases diagnosed during the study period (n=19)), whether the study required the consent of participants (yes/no) was included as a proxy for (low/high) sampling fraction. The risk of bias within each study was assessed using the STROME-ID checklist.35

Data were analysed in Stata V.12. Where studies reported data from more than one set of loci, the method with the highest discriminatory value was included (ie, MIRU-VNTR 24 would be chosen over MIRU-VNTR 15, and MIRU-VNTR 15 plus Spoligotyping would be chosen over MIRU-VNTR 15 alone; n=8). This review was not concerned with summary measures of clustering, but factors that influenced clustering; therefore articles must have included at least one of the covariates. Continuous variables were transformed where the distribution was skewed. The proportion clustered was transformed using the Freeman Tukey transformation.36 Study heterogeneity was assessed using a forest plot and the χ2 test of heterogeneity. Univariable meta-regression analyses were carried out to determine the effect of the study design covariates on the proportion of clustered isolates. All covariates in the analysis were hypothesised to influence the proportion clustered a priori.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to see the effect of removing studies reporting 0% clustering, with only extrapulmonary TB cases, only Mycobacterium bovis cases, studies using the ‘old 12’ MIRU loci as part of their 15 loci, and studies assessed as having a high likelihood of bias (STROME-ID score less than 20).

Results

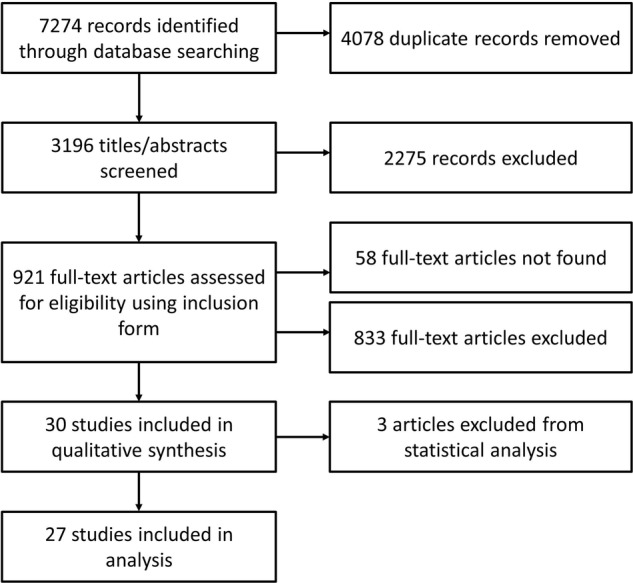

The search identified 7274 references resulting in 27 studies (25 journal articles and 2 conference abstracts) included after deduplication and title/abstract/full text screening (figure 1). The main characteristics of the included studies are shown in table 1. Studies were published between 2007 and 2014 and the clustering reported varied from 0%37 to 62.8%.38 In all studies, clustered isolates were defined as having identical strain types based on the MIRU-VNTR loci typed, with or without Spoligotyping. Seventeen studies included isolates from newly diagnosed TB cases, three studies reported including isolates from new and chronic cases of TB, and seven did not report this information. In addition, 10 studies did not include repeat isolates from the same patient, one study included a repeat isolate from one patient and the remaining 17 did not report whether repeat isolates were included or not. Furthermore, four studies included isolates with missing loci in the cluster analysis, whereas four excluded isolates with missing loci and the remaining 20 did not report how they dealt with missing loci. The number of studies reporting each variable of interest is shown in table 2. STROME-ID scores can be found in online supplementary appendix 2.

Figure 1.

Results of systematic search, screening and data extraction.

Table 1.

The study setting and design characteristics of the included articles

| Reference | Study setting |

Study design |

Risk of bias* | Clustering (%)† | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study area and country | TB incidence (per 100 000) | TB/HIV (per 100 000)‡ | Previous TB treatment (%) | Pulmonary TB (%) | Maximum cluster size | Clusters of size 2 (%) | Study duration (months) | Study size (clustered +unique isolates) | Culture positive in study population (%) | Culture positive isolates typed (%) | Typing method§ | Loci typed¶ | Consent required | |||

| 51 | New South Wales, Australia | 6.7 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 63.7 | 36 | 1128 | m24 | N | no | low | 20.1 | ||||

| 40 | Tabriz and Orumieh, Azarbaijan | 26.0 | 5.2 | 87.0 | 5 | 81.8 | 12 | 156 | 94.5 | m15 | O | no | low | 32.7 | ||

| 52 | Brussels-Capital Region, Belgium | 35.2 | 5.1 | 10.8 | 23 | 64.2 | 24 | 530 | 86.1 | 87.9 | m24 | N | no | low | 29.6 | |

| 53 | Brussels-Capital Region, Belgium | 35.2 | 5.1 | 100 | 39 | 802 | 81.8 | 84.7 | m24s | N | no | low | 28.8 | |||

| 54 | Ontario, Canada | 4.8 | 0.4 | 18 | 58.8 | 65 | 2016 | m24s | N | no | low | 23.1 | ||||

| 37 | Changping District, Beijing, China | 0.3 | 100 | 0 | 30 | 318 | 31.5 | 94.6 | m24 | N | no | high | 0.0 | |||

| 38 | Croatia | 19.0 | 0.1 | 45 | 48.3 | 36 | 1587 | m15 | N | no | high | 62.8 | ||||

| 55 | Amhara region, Northwest Ethiopia | 24.0 | 17.6 | 100 | 13 | 5 | 244 | m24 | N | yes | low | 45.1 | ||||

| 56 | Finland | 5.0 | 0.0 | 20 | 48 | 1048 | 75.4 | 99.4 | m15s | no | low | 33.9 | ||||

| 57 | Hamburg, Germany | 12.7 | 45.5 | 12 | 154 | 78.2 | 91.1 | m24s | N | no | low | 22.1 | ||||

| 45 | Schleswig-Holstein, Germany | 3.2 | 0.1 | 22 | 44.4 | 48 | 277 | m24s | N | no | high | 27.1 | ||||

| 58 | South West Ireland | 15.3 | 3.3 | 82.7 | 12 | 36 | 171 | 79.5 | 96.1 | m24s | N | no | low | 27.5 | ||

| 59 | South Tawara, Kiribati | 370.0 | 4.1 | 100 | 25 | 55.6 | 24 | 73 | 45.4 | 98.6 | m24s | N | yes | low | 75.3 | |

| 60 | Netherlands | 6.5 | 0.2 | 57.2 | 60 | 3978 | 100.1 | m24 | N | no | low | 46.7 | ||||

| 41 | Kharkiv, Russia | 94.0 | 3.8 | 63.3 | 100 | 10 | 50.0 | 3 | 98 | 100 | m15 | O | yes | high | 31.6 | |

| 61 | Eastern province, Saudi Arabia | 4.0 | 73.1 | 24 | 19.0 | 24 | 522 | m24s | N | no | low | 40.2 | ||||

| 62 | Singapore | 40.5 | 1.2 | 21 | 48.0 | 24 | 1128 | 82.0 | 34.5 | m24s | N | no | low | 30.8 | ||

| 63 | Slovenia | 10.6 | 0.0 | 6 | 12 | 196 | 94.4 | 97.5 | m24s | N | no | low | 36.2 | |||

| 47 | Almeria, Spain | 26.0 | 6.0 | 8 | 27 | 281 | 81.9 | m15 | N | no | high | 43.1 | ||||

| 64 | Sweden | 4.8 | 0.1 | 10 | 36 | 406 | m24s | N | no | low | 21.2 | |||||

| 65 | Mubende, Uganda | 86.0 | 31.1 | 87.8 | 11 | 70.0 | 6 | 67 | 21.5 | 90.5 | m15s | N | yes | low | 35.8 | |

| 42 | East Lancashire, UK | 18.3 | 8.2 | 13 | 58.3 | 102 | 332 | 48.5 | 69.9 | m15 | O | no | low | 42.8 | ||

| 39 | UK | 8.2 | 42.3 | 12 | 50.0 | 48 | 102 | 90.7 | 87.2 | m15 | O | no | low | 30.4 | ||

| 66 | London, UK | 44.9 | 8.2 | 9 | 964 | 36.0 | 100 | m24 | N | no | 37.0 | |||||

| 43 | Midlands, UK | 15.0 | 8.2 | 48 | 4207 | 58.3 | 100 | m15 | O | no | 61.2 | |||||

| 44 | Odessa and Nikolaev, Ukraine | 80.4 | 3.9 | 34.2 | 100 | 4 | 225 | m15 | O | yes** | low | 60.4 | ||||

| 67 | Hanoi, Vietnam | 146.0 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 100 | 20 | 465 | 92.7 | 91.9 | m15s | N | yes | low | 55.3 | ||

*Risk of bias was assessed using the STROME-ID checklist. Studies scoring <20 were categorised as have a high risk of bias. See online supplementary appendix 2 for STROME-ID scores.

†The proportion of clustering was calculated as the number of clustered isolates/number of clustered+unique isolates.

§15=15 MIRU-VNTR loci (made up of the ‘old 12’ or ‘new 12’ defined in the footnote below), 24=24 MIRU-VNTR loci (ETR A, B, C, D, E; MIRU 2, 10, 16, 20, 23, 24, 26, 27, 39, 40; VNTR 424, 1955, 2163b, 2347, 2401, 3171, 3690, 4052, 4156), S=with Spoligotyping.

¶O=old 12 MIRU loci (MIRU 2, 4, 10, 16, 20, 23, 24, 26, 27,30, 31, 39, 40), N=new 12 MIRU loci (MIRU 10, 16, 26, 31, 40 +Mtub 04, 21, 39+ETR A C+QUB 11b, 26).

**11.3% did not consent to being part of the study. The other studies that required consent for isolates to be typed did not report the refusal rate.

ETR, Exact Tandem Repeat; TB, tuberculosis.

Table 2.

The number of studies that reported the variables of interest

| Reported | Missing | |

|---|---|---|

| Study setting | ||

| TB incidence | 8 | 15 |

| TB/HIV coinfection | 5 | 22 |

| Previous TB treatment | 9 | 18 |

| Proportion pulmonary TB | 14 | 13 |

| Maximum cluster size | 19 | 8 |

| Percentage of clusters with 2 cases | 14 | 13 |

| Study design | ||

| Study duration | 27 | 0 |

| Study size | 27 | 0 |

| Percentage of population that is culture positive | 15 | 12 |

| Percentage of culture positive typed | 19 | 8 |

| 24 loci (compared to 15) | 27 | 0 |

| Repeat isolates | 12 | 15 |

| Missing loci | 8 | 19 |

| Double alleles | 1 | 26 |

| Consent required | 6* | 21 |

| Epidemiological information | 6 | 21 |

*Only one study reported the consent rate.

TB, tuberculosis.

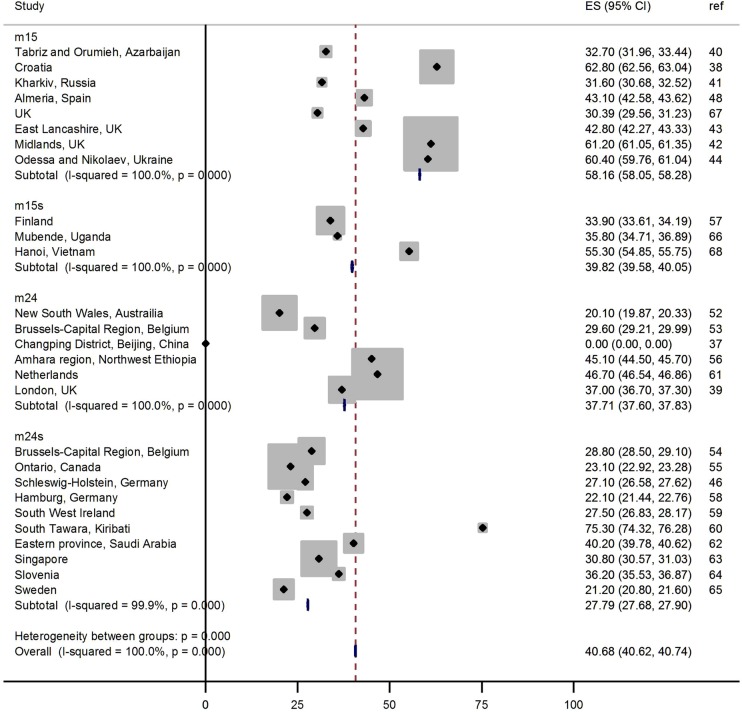

A forest plot shows the spread of clustering reported by number of loci and additional typing method (figure 2). Significant heterogeneity was identified between the studies (p<0.001), suggesting that a metaregression would be an appropriate analysis.

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing the proportion of clustering reported in each study by the number of MIRU-VNTR loci typed. The number of loci typed is categorised into 15 loci (m15), 15 loci with Spoligotyping (m15 s), 24 loci (m24) and 24 loci with Spoligotyping (m24 s). The study reference is shown in the right hand column.

The univariable metaregression shows evidence for the proportion of clustering to decrease as the number of MIRU-VNTR loci typed increased from 15 to 24 (p=0.04; table 3), accounting for 14% of the between study variation, and to increase when the study participants consented to being included in the study (p=0.03), accounting for 14% of the between study variation. The proportion of clustering increased as the TB incidence in the population increased (p=0.007, adjusted R2=26.7). There was also evidence for the proportion of clustering to increase as the maximum cluster size increased (p=0.001), accounting for 48% of between study variation. There was no evidence of the other study design or study setting variables significantly influencing the proportion clustered. Though non-significant (p>0.05), the TB/HIV coinfection rate in the population explained 2% of the between study variation. Too few studies included information on the proportion of clusters containing two cases, proportion of the study sample with previous TB or with pulmonary TB, so these could not be included in the analysis (table 2).

Table 3.

Univariable metaregression showing the coefficients for change in the proportion of clustering and the percentage of between-study variation explained by variables describing the study design and setting

| n | Coefficient* | CI | p Value | Adjusted R2† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study setting | |||||

| TB incidence | 23 | 0.14 | 0.04 to 0.24 | 0.007 | 26.74 |

| TB/HIV coinfection | 23 | 0.04 | −0.03 to 0.11 | 0.246 | 2.00 |

| Maximum cluster size | 19 | 0.20 | 0.09 to 0.30 | 0.001 | 48.20 |

| Study design | |||||

| Study duration | 27 | −0.02 | −0.09 to 0.06 | 0.677 | −3.37 |

| Percentage of population that is culture positive | 15 | 0.34 | −1.23 to 1.96 | 0.661 | −5.92 |

| Percentage of culture positive typed | 19 | 0.22 | −1.08 to 1.52 | 0.725 | −5.41 |

| Study size | 27 | 0.03 | −0.11 to 0.16 | 0.702 | −3.31 |

| 24 loci (compared to 15) | 27 | −0.30 | −0.59 to −0.01 | 0.04 | 13.58 |

| Consent required | 27 | 0.38 | 0.04 to 0.72 | 0.029 | 14.41 |

*Coefficients for the change in the proportion of clustering for each covariate. For example, for a one unit increase in maximum cluster size, the proportion of clustering increases by 0.2.

†The proportion of between-study variation explained by the univariate metaregression.

TB, tuberculosis.

Sensitivity analyses to examine the effect of excluding studies reporting 0% clustering,37 only M. bovis cases,39 studies using the ‘old 12’ MIRU loci,39–44 and studies assessed as having a high risk of bias,37 38 45–47 did not generally change the results. The proportion of culture-positive TB in the population remained insignificant but explained 2.6% of the between study variation when excluding 0% clustering (p=0.278 and adjusted R2=2.62). Similarly, the proportion of culture-positive TB in the population remained insignificant but explained 2.6% of the between study variation when excluding studies with the highest risk of bias (p=0.278 and adjusted R2=2.62). The number of loci typed became non-significant, but explained 9.6% and 10.5% of the between study variation when excluding studies using the ‘old 12’ loci and the highest risk of bias, respectively (p=0.106, adjusted R2=9.63; p=0.111, adjusted R2=10.51, respectively).

Discussion

This review identified 27 studies that met the inclusion criteria. We illustrate that the interpretation of studies using MIRU-VNTR to estimate clustering is subject to bias relating to study design and setting; however, there were insufficient data available to fully explore this impact.

As expected, we found that the proportion of clustering decreased with a greater number of MIRU-VNTR loci typed, with increasing TB incidence and with increasing maximum cluster size. We found that requiring consent to type patient isolates increased the proportion of clustering, which is not expected, given that the sampling fraction would be lower in these studies.

The other study design variables included in this analysis, such as study duration, did not significantly influence the proportion of isolates that were clustered, contrary to previous findings.12 This is likely to be because of a lack of good quality evidence: of the 27 studies that met the inclusion criteria for the review, none reported all the variables of interest, reducing the power of the analysis and precluding multivariable metaregression (table 2). Importantly, key details of cluster analyses were not reported consistently across the studies, such as whether repeat isolates from the same patients were included, or typing profiles with missing loci were included, introducing new, unmeasured biases. In addition, the range of the variables may have been too limited to show any impact on clustering estimates. For example, the proportion of culture-positive isolates typed ranged from 34.5% to 100%, with 17 of the 19 studies reporting this variable from 81.9% to 100%. Furthermore, most of the studies (17/27=63%) were from low TB burden settings and therefore may be reflecting the rate at which imported cases have matching strain types by chance, rather than rates of recent transmission.

The sensitivity analysis suggested that, when excluding the studies with the greatest risk of bias, the culture-positivity in the population might explain a small amount of the between-study variation. This is consistent with estimates of the influence of sampling on the proportion of clustering using IS6110 RFLP typing.48 In the sensitivity analysis excluding studies that used the ‘old 12’ loci, the effect of the number of loci typed becomes non-significant. This is likely because studies using the ‘old 12’ accounted for six out of 10 studies reporting 15 loci, reducing the number of studies and the power of the model.

This study is a timely evaluation of the impact of study design on estimates of TB clustering using MIRU-VNTR strain typing because it has been incorporated into national typing services globally.23 49 The findings are relevant where strain typing is used to evaluate TB control systems across different settings because the proportion of clustering is influenced by the number of loci typed, the TB incidence and the maximum cluster size. Given that strain typing methods are advancing beyond MIRU-VNTR typing and that the application of whole genome sequencing to TB control and public health strategies has been demonstrated,9–11 50 it is important that the biases in the analysis of such methods are explored and compared. Understanding how to design and compare research studies for public health will greatly improve the benefit gained from newer technologies.

The strength of this meta-analysis was limited by the (lack of) detail reported by the included studies. This review has highlighted the need for better quality reporting in primary studies to enable future reviews to be more robust. Recently published standards for reporting of molecular epidemiology for infectious diseases should improve the quality of reporting.35 This review is further limited by our inability to access 58 of the title/abstract screened articles for full text screening.

The use of TB strain typing as a public health tool in TB control programmes is increasing globally. We have identified a lack of good quality studies that can contribute to our understanding in interpreting the molecular typing of TB. We have also shown that the proportion of clustering derived from MIRU-VTNR typing is influenced by the number of loci typed, whether consent is required to type isolates, TB incidence in the study setting and the maximum cluster size, highlighting these as important considerations in the design and interpretation of future studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Ross Harris from the Statistics Unit at Public Health England for his advice on metaregression.

Footnotes

Contributors: JM drafted the article and PS, IA, TDM and TC revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the review, and the analysis and interpretation of data. All authors approved the final version for publication.

Funding: Public Health England and University College London Impact Studentship. JM is funded through a Public Health England and University College London Impact Studentship. IA is funded through a NIHR Senior Research Fellowship

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Lambregts-van Weezenbeek CSB, Sebek MMGG, van Gerven PJHJ et al. Tuberculosis contact investigation and DNA fingerprint surveillance in The Netherlands: 6 years’ experience with nation-wide cluster feedback and cluster monitoring. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2003;7:S463–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borgdorff MW, van den Hof S, Kremer K et al. Progress towards tuberculosis elimination: secular trend, immigration and transmission. Eur Respir J 2010;36:339–47. 10.1183/09031936.00155409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kik SV, Verver S, Van Soolingen D et al. Tuberculosis outbreaks predicted by characteristics of first patients in a DNA fingerprint cluster. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:96–104. 10.1164/rccm.200708-1256OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Small PM, McClenny NB, Singh SP et al. Molecular strain typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to confirm cross-contamination in the mycobacteriology laboratory and modification of procedures to minimize occurrence of false-positive cultures. J Clin Microbiol 1993;31:1677–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Vries G, van Hest RAH, Richardus JH. Impact of mobile radiographic screening on tuberculosis among drug users and homeless persons. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:201–7. 10.1164/rccm.200612-1877OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamerbeek J, Schouls L, Kolk A et al. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol 1997;35:907–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Embden JD, Cave MD, Crawford JT et al. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J Clin Microbiol 1993;31:406–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Supply P, Allix C, Lesjean S et al. Proposal for standardization of optimized mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit-variable-number tandem repeat typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol 2006;44:4498–510. 10.1128/JCM.01392-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schürch AC, van Soolingen D. DNA fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: from phage typing to whole-genome sequencing. Infect Genet Evol 2012;12:602–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22067515 (accessed 13 Mar 2012). 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardy JL, Johnston JC, Ho Sui SJ et al. Whole-genome sequencing and social-network analysis of a tuberculosis outbreak. N Engl J Med 2011;364:730–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1003176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker TM, Ip CL, Harrell RH et al. Whole-genome sequencing to delineate Mycobacterium tuberculosis outbreaks: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis 2013;13:137–46. 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70277-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houben RMGJ, Glynn JR. A systematic review and meta-analysis of molecular epidemiological studies of tuberculosis: development of a new tool to aid interpretation. Trop Med Int Health 2009;14:892–909. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02316.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fok A, Numata Y, Schulzer M et al. Risk factors for clustering of tuberculosis cases: a systematic review of population-based molecular epidemiology studies. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2008;12:480–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borgdorff MW, Van Den Hof S, Kalisvaart N et al. Influence of sampling on clustering and associations with risk factors in the molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis. Am J Epidemiol 2011;174:243–51. http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2011/05/23/aje.kwr061 (accessed 29 Mar 2012). 10.1093/aje/kwr061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glynn JR, Bauer J, de Boer AS et al. Interpreting DNA fingerprint clusters of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. European concerted action on molecular epidemiology and control of tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 1999;3:1055–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glynn JR, Crampin AC, Yates MD et al. The importance of recent infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis in an area with high HIV prevalence: a long-term molecular epidemiological study in Northern Malawi. J Infect Dis 2005;192:480–7. 10.1086/431517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Beer JL, Kremer K, Ködmön C et al. First worldwide proficiency study on variable-number tandem-repeat typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains. J Clin Microbiol 2012;50:662–9. 10.1128/JCM.00607-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maes M, Kremer K, van Soolingen D et al. 24-locus MIRU-VNTR genotyping is a useful tool to study the molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis among Warao Amerindians in Venezuela. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2008;88:490–4. 10.1016/j.tube.2008.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sougakoff W. Molecular epidemiology of multidrug-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011;17:800–5. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03577.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weniger T, Krawczyk J, Supply P et al. MIRU-VNTRplus: a web tool for polyphasic genotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res 2010;38:W326–31. 10.1093/nar/gkq351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Supply P. MIRU-VNTR typing: the new international standard for TB molecular epidemiology Symposium of the Institut Pasteur de Tunisia, 2010.

- 22.Van Soolingen D, Borgdorff MW, de Haas PE et al. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis in the Netherlands: a nationwide study from 1993 through 1997. J Infect Dis 1999;180:726–36. 10.1086/314930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cowan LS, Diem L, Monson T et al. Evaluation of a two-step approach for large-scale, prospective genotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in the United States. J Clin Microbiol 2005;43:688–95. 10.1128/JCM.43.2.688-695.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. New CDC program for rapid genotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. JAMA 2005;293:2086–2086. 10.1001/jama.293.17.2086 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bauer J, Kok-Jensen A, Faurschou P et al. A prospective evaluation of the clinical value of nation-wide DNA fingerprinting of tuberculosis isolates in Denmark. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2000;4:295–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bauer J, Yang Z, Poulsen S et al. Results from 5 years of nationwide DNA fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates in a country with a low incidence of M. tuberculosis infection. J Clin Microbiol 1998;36:305–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zolnir-Dovc M, Poljak M, Erzen D et al. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis in Slovenia: results of a one-year (2001) nation-wide study. Scand J Infect Dis 2003;35:863–8. 10.1080/00365540310017221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanekom M, van der Spuy GD, Gey van Pittius NC et al. Discordance between mycobacterial interspersed repetitive-unit-variable-number tandem-repeat typing and IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism genotyping for analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing strains in a setting of high incidence of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:3338–45. 10.1128/JCM.00770-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Supply P, Lesjean S, Savine E et al. Automated high-throughput genotyping for study of global epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units. J Clin Microbiol 2001;39:3563–71. 10.1128/JCM.39.10.3563-3571.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gopaul KK, Brown TJ, Gibson AL et al. Progression toward an improved DNA amplification-based typing technique in the study of Mycobacterium tuberculosis epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol 2006;44:2492–8. 10.1128/JCM.01428-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunter PR, Gaston MA. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson's index of diversity. J Clin Microbiol 1988;26:2465–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.WHO|TB data (n.d.). WHO. http://www.who.int/tb/country/en/index.html (accessed 12 Dec 2012).

- 33.Kruijshaar ME, Pimpin L, Abubakar I et al. The burden of TB-HIV in the EU: how much do we know? A survey of surveillance practices and results. Eur Respir J 2011;38:1374–81. 10.1183/09031936.00198310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization (n.d.) WHO Tuberculosis Country Profiles. http://www.who.int/tb/country/data/profiles/en/

- 35.Field N, Cohen T, Struelens MJ et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Molecular Epidemiology for Infectious Diseases (STROME-ID): an extension of the STROBE statement. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:341–52. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70324-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freeman MF, Tukey JW. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Statist 1950;21:607–11. 10.1214/aoms/1177729756 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guang-ming D, Zhi-guo Z, Peng-ju D et al. Differences in the population of genetics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis between urban migrants and local residents in Beijing, China. Chin Med J 2013;126:4066–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zmak L, Obrovac M, Katalinic Jankovic V. First insights into the molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis in Croatia during a three-year period, 2009 to 2011. Scand J Infect Dis 2014;46:123–9. 10.3109/00365548.2013.855322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mandal S, Bradshaw L, Anderson LF et al. Investigating transmission of Mycobacterium bovis in the United Kingdom in 2005 to 2008. J Clin Microbiol 2011;49:1943–50. 10.1128/JCM.02299-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Asgharzadeh M, Kafil HS, Roudsary AA et al. Tuberculosis transmission in Northwest of Iran: using MIRU-VNTR, ETR-VNTR and IS6110-RFLP methods. Infect Genet Evol 2011;11:124–31. 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dymova MA, Liashenko OO, Poteiko PI et al. Genetic variation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis circulating in Kharkiv Oblast, Ukraine. BMC Infect Dis 2011;11:77 10.1186/1471-2334-11-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sails AD, Barrett A, Sarginson S et al. Molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in East Lancashire 2001-2009. Thorax 2011;66:709–13. 10.1136/thx.2011.158881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Evans J. Analysis of prevalent Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains in the United Kingdom: detection, distribution and expansion of MIRU-VNTR profiles containing high numbers of isolates. Vienna, Austria: European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nikolayevskyy VV, Brown TJ, Bazhora YI et al. Molecular epidemiology and prevalence of mutations conferring rifampicin and isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains from the southern Ukraine. Clin Microbiol Infect 2007;13:129–38. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01583.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roetzer A, Schuback S, Diel R et al. Evaluation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis typing methods in a 4-year study in Schleswig-Holstein, Northern Germany. J Clin Microbiol 2011;49:4173–8. 10.1128/JCM.05293-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dymova MA, Kinsht VN, Cherednichenko AG et al. Highest prevalence of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype isolates in patients newly diagnosed with tuberculosis in the Novosibirsk oblast, Russian Federation. J Med Microbiol 2011;60:1003–9. 10.1099/jmm.0.027995-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alonso-Rodriguez N, Martínez-Lirola M, Sánchez ML et al. Prospective universal application of mycobacterial interspersed repetitive-unit-variable-number tandem-repeat genotyping to characterize Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates for fast identification of clustered and orphan cases. J Clin Microbiol 2009;47:2026–32. 10.1128/JCM.02308-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glynn JR, Vyonycky E, Fine PEM. Influence of sampling on estimates of clustering and recent transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis derived from DNA fingerprinting techniques. Am J Epidemiol 1999;149:366–71. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.TB Strain Typing Project Board HPA. TB Strain Typing Cluster Investigation Handbook for Health Protection Units 1st Edition 2011. https://hpaintranet.hpa.org.uk/Content/ProgrammesProjects/HPAProgrammes/HPAKeyHealthProtectionProgrammes/Respiratory/TB/StrainTyping/ (accessed 30 Nov 2011).

- 50.Walker TM, Monk P, Grace Smith E et al. Contact investigations for outbreaks of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: advances through whole genome sequencing. Clin Microbiol Infect 2013;19:796–802. 10.1111/1469-0691.12183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gurjav U, Jelfs P, McCallum N et al. Temporal dynamics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotypes in New South Wales, Australia. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:455–5. 10.1186/1471-2334-14-455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allix-Béguec C, Fauville-Dufaux M, Supply P. Three-year population-based evaluation of standardized mycobacterial interspersed repetitive-unit-variable-number tandem-repeat typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:1398–406. 10.1128/JCM.02089-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Allix-Béguec C, Supply P, Wanlin M et al. Standardised PCR-based molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis. Eur Respir J 2008;31:1077–84. 10.1183/09031936.00053307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tuite AR, Guthrie JL, Alexander DC et al. Epidemiological evaluation of spatiotemporal and genotypic clustering of mycobacterium tuberculosis in Ontario, Canada. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2013;17:1322–7. 10.5588/ijtld.13.0145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tessema B, Beer J, Merker M et al. Molecular epidemiology and transmission dynamics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Northwest Ethiopia: new phylogenetic lineages found in Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:131 10.1186/1471-2334-13-131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smit PW, Haanpera M, Rantala P et al. Molecular Epidemiology of Tuberculosis in Finland, 2008-2011. PLoS ONE 2013; 8:e85027 10.1371/journal.pone.0085027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oelemann MC, Diel R, Vatin V et al. Assessment of an optimized mycobacterial interspersed repetitive- unit-variable-number tandem-repeat typing system combined with spoligotyping for population-based molecular epidemiology studies of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol 2007;45:691–7. 10.1128/JCM.01393-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ojo OO, Sheehan S, Corcoran DG et al. Molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates in Southwest Ireland. Infect Genet Evol 2010;10:1110–16. 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aleksic E, Merker M, Cox H et al. First Molecular Epidemiology Study of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Kiribati. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e55423 http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-84873163328&partnerID=40&md5=3994b8e5638129b621abc4d7d6d5e3b8http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-84873163328&partnerID=40&md5=3994b8e5638129b621abc4d7d6d5e3b8 10.1371/journal.pone.0055423http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Beer JL, van Ingen J, de Vries G et al. Comparative study of IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism and variable-number tandem-repeat typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in the Netherlands, based on a 5-year nationwide survey. J Clin Microbiol 2013;51:1193–8. 10.1128/JCM.03061-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Varghese B, Supply P, Shoukri M et al. Tuberculosis transmission among immigrants and autochthonous populations of the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e77635 http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-84885784886&partnerID=40&md5=4fdbf4015a999a9fcd1a1c31207a75a2 10.1371/journal.pone.0077635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lim LK-Y, Sng LH, Win W et al. Molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in Singapore, 2006-2012. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e84487 10.1371/journal.pone.0084487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bidovec-Stojkovic U, Zolnir-Dovc M, Supply P. One year nationwide evaluation of 24-locus MIRU-VNTR genotyping on Slovenian Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. Respir Med 2011;105(Suppl 1):S67–73. 10.1016/S0954-6111(11)70014-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jonsson J, Hoffner S, Berggren I et al. Comparison between RFLP and MIRU-VNTR genotyping of mycobacterium tuberculosis strains isolated in stockholm 2009 to 2011. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e95159 http://www.plosone.org/article/fetchObject.action?uri=info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0095159&representation=PDF 10.1371/journal.pone.0095159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Muwonge A, Malama S, Johansen TB et al. Molecular epidemiology, drug susceptibility and economic aspects of tuberculosis in Mubende District, Uganda. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e64745 http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-84878608813&partnerID=40&md5=babbd6d006ca64e327fb19e01b6bc697 10.1371/journal.pone.0064745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hamblion EL, Wynne-Edwards E, Anderson C et al. A summary of strain typing and clustering of TB in London in 2010 and an analysis of the associated risk factors. Thorax 2011;66:A88–9. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201054c.50 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hang NTL, Maeda S, Lien LT et al. Primary drug-resistant tuberculosis in Hanoi, Vietnam: present status and risk factors. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e71867 UNSP 10.1371/journal.pone.0071867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.