Abstract

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is the most common cause of end-stage kidney disease in the United States, and accounts for a significant increase in morbidity and mortality in patients with diabetes. Early detection is critical in improving clinical management. Although microalbuminuria is regarded as the gold standard for diagnosing onset of DN, its predictive powers are limited. There have been great efforts in recent years to identify better strategies for the detection of early stages of DN and progressive kidney function decline in diabetic patients. Here, we review various urinary biomarkers that have emerged and hold promise to be more sensitive for earlier detection of diabetic kidney disease and predictive of progression to end-stage kidney disease. A number of key biomarkers present in the urine have been identified that reflect kidney injury at specific sites along the nephron, including glomerular/podocyte damage and tubular damage, oxidative stress, inflammation, and activation of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system. Moreover, we describe newer approaches including urinary microRNAs, which are short noncoding mRNAs that regulate gene expression, and urine proteomics used to identify potential novel biomarkers in the development and progression of diabetic kidney disease.

Keywords: Biomarkers, Diabetic nephropathy, microRNA, Podocyte, Proteomics, Tubular damage

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most common chronic diseases, and its incidence continues to increase not just in adults but also in the pediatric population. A recent study based on Markov modeling projected that by year 2050 the U.S. population below the age of 20 years with type 1 or type 2 diabetes would increase by 1.2–3 fold and 1.5–4 fold, respectively [1]. The rising burden of diabetes has significant public health impact. Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is considered one of the major microvascular complications of diabetes and arguably the most devastating, given that those with kidney disease predominantly account for the increased morbidity and mortality in diabetic patients [2]. DN is the largest single cause of end-stage kidney disease, underscoring the importance of early identification, treatment and prevention. There is a particular need to identify those at risk of DN in the pediatric population given the increasing prevalence of diabetes observed in youths and the ensuing diabetic kidney disease.

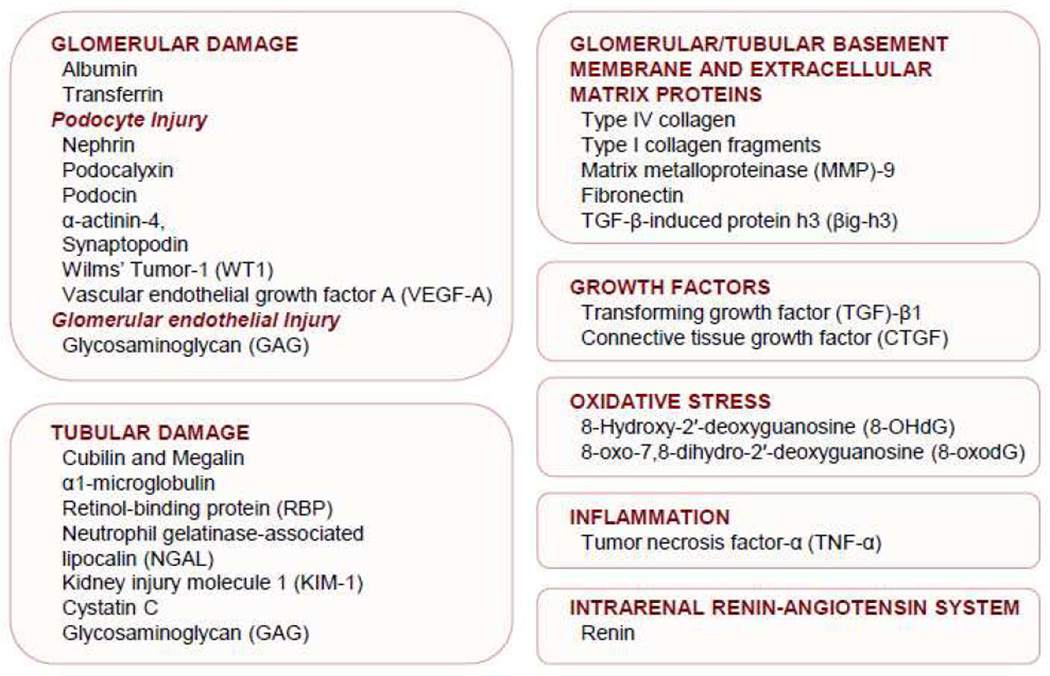

Microalbuminuria is the most widely used early clinical indicator of DN and has been recognized as a predictor of progression to end-stage kidney disease in both type 1 [3] and type 2 diabetes [4]. However, there are attendant shortcomings of microalbuminuria for diagnosing onset of diabetic kidney disease and its predictive powers are limited. Some patients without microalbuminuria display advanced renal pathological changes, indicating that microalbuminuria may not be an optimal marker for early detection of diabetic kidney disease [5, 6]. In some instances, patients with diabetes develop progressive loss of kidney function before the development of microalbuminuria [7, 8]. Some patients who have microalbuminuria at one point in time no longer have it when measured at a later time and it is a poor predictor of the development of macroalbuminuria [9]. Microalbuminuria is not specific for the presence of diabetic kidney disease because it can occur in patients with diabetes without concurrent or future DN, and in nondiabetic patients with progressive chronic kidney disease (CKD) [10]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify more sensitive and specific biomarkers than microalbuminura for early detection of diabetic kidney disease and prediction of progression to end-stage kidney disease. To this end, there have been intensive investigations in recent years, and here, we review key urinary biomarkers that have emerged. A number of new and important biomarkers present in the urine have been identified. They include biomarkers that reflect kidney injury due to glomerular/podocyte damage and tubular damage, oxidative stress, inflammation and activation of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system (Figure 1). We also describe newer approaches including urinary microRNAs and urine proteomics used to identify potential novel biomarkers in the development and progression of diabetic kidney disease.

Figure 1.

Urinary biomarkers of diabetic nephropathy that reflect kidney injury due to glomerular/podocute damage and tubular damage, growth factors, oxidative stress, inflammation, and activation of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system

Biomarkers of glomerular damage

A key feature of glomerular damage in DN is characterized by changes in glomerular permeability and structure that can occur as a result of injury to any of the major components of glomerular filtration barrier apparatus, including the glomerular basement membrane, podocytes and glomerular capillary endothelium. Glomerular damage results in the appearance in urine of an excess of serum proteins that are not normally freely filtered through the glomerulus, including macromolecules such as albumin and transferrin, and extracellular matrix proteins [11]. In normal individuals, only a small amount of albumin is filtered in the glomerulus and it is subsequently reabsorbed by the tubules. The onset of microalbuminuria is used clinically for diagnosing DN at present, but certain limitations as discussed above should be taken into consideration.

Transferrin is a serum protein that is very similar in molecular weight to albumin, 76.5 kDa and 65 kDa respectively, but is less anionic than albumin and presumably filtered more readily in the glomerulus [12]. Thus, urinary transferrin may be a more sensitive marker of glomerular damage in patients with diabetes. Indeed, elevated urinary transferrin excretion, or transferrinuria, has been reported in diabetic patients, even in those without albuminuria [13]. An abnormal urinary transferrin/creatinine ratio was found in up to 61% of normoalbuminuric patients [14]. Among patients with type 2 diabetes, 31% of patients who exhibited transferrinuria at baseline subsequently developed microalbuminuria, compared with 7% of patients without transferrinuria [15]. Therefore, increased transferrinuria was a predictor of the development of microalbuminuria in normoalbuminuric type 2 diabetic patients [15, 16]. Increased urinary transferrin excretion has also been reported in children with type 1 diabetes and correlated significantly with urinary albumin excretion [17]. In patients who already exhibit albuminuria, urinary transferrin excretion has a linear relationship with urinary albumin excretion, and increased transferrinuria was found in 95% of microalbuminuric patients and 100% of macroalbuminuric patients [14]. Transferrinuria may be a more sensitive indicator for earlier detection of DN than microalbuminuria and a predictor of the development of microalbuminuria. However, urinary transferrin excretion, like albumin, is also elevated in other diseases that affect the glomerulus, such as primary glomerulonephritis, and is not specific to DN [18].

Podocyte injury

Podocyte injury has been reported as an early feature of DN [19]. A reduction in podocyte number and density per glomerulus has been linked to the development of proteinuria and the progression of diabetic kidney disease in patients with diabetes [20]. Studies reporting podocytopenia in normoalbuminuric patients suggest that podocyte lesions exist before the development of proteinuria [20, 21]. A number of podocyte-specific proteins have been examined for their potential roles as biomarkers of early DN and progression of diabetic kidney disease.

Nephrin, a transmembrane protein of the immunoglobulin superfamily, is a key molecular component of the glomerular filtration slit diaphragm between adjacent podocytes. Its expression is known to be altered in experimental models of diabetes and also in various human proteinuric diseases, including diabetes [22]. A recent investigation by Jim et al revealed that nephrinuria was present in 100% of type 2 diabetic patients with microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria [23]. Interestingly, nephrinuria was also present in 54% of the type 2 diabetic patients with normoalbuminuria [24]. Similarly, nephrinuria was observed in 30% of normoalbuminuric type 1 diabetic patients, as well as 28% of patients previously normoalbuminuric but subsequently testing positive for microalbuminuria, whereas none of the nondiabetic control subjects had nephrinuria [20]. While further research is needed to confirm the above findings, urine nephrin levels could be a good biomarker of early diabetic kidney disease, as it appears to precede development of microalbuminuria.

Podocalyxin, a sialoglycoprotein, is the major constituent of the glycocalyx of podocytes and is responsible for the highly negative surface charge of podocytes. In addition to other podocytopathies in glomerular disease, microvillous transformations containing podocalyxin appear on the apical surface of injured podocytes, and these are shed into urine. Hara et al quantified such shedding of vesicles using highly sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect urinary podocalyxin in patients with type 2 diabetes [24]. Interestingly, elevated levels of urinary podocalyxin were observed in 53.8% of normoalbuminuric patients, indicating that urinary podocalyxin might be a useful biomarker for detecting early podocyte injury in diabetic patients [24]. Moreover, urinary mRNA profile studies suggest that quantification of mRNA expression of podocalyxin, and other podocyte-associated molecules such as synaptopodin, α-actinin-4, and podocin may be useful biomarkers for detecting early podocyte injury and the progression of diabetic kidney disease [25, 26]. However, the strategy of utilizing urinary mRNA is limited by the susceptibility for mRNA degradation by the presence of RNAses. There is also the issue of specificity given that podocalyxin expression is not restricted to podocytes, but is also expressed in endothelial cells, parietal epithelial cells, and a variety of nonrenal cells, such as platelets and hematopoietic stem cells [27].

Wilms’ Tumor-1 (WT1) is a zinc-finger transcription factor that plays an important role in podocyte maturation [19, 21]. In the mature glomerulus, the expression of WT1 is limited to podocytes. Kubo et al first reported the detection of endogenous WT1 mRNA in the urine of patients with renal diseases, including DN [28]. More recently, WT1 protein in urinary exosomes was isolated from spot urine samples of patients with type 1 diabetes, and higher levels were associated with significant increases in the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, albumin-to-creatinine ratio and serum creatinine levels, as well as a decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) [21]. Interestingly, 50% of diabetic patients without proteinuria were also positive for urinary WT1 protein, while nondiabetic control subjects showed an almost absent level of WT1 [21]. These findings suggest that urinary WT1 protein levels could serve as a podocyte-specific biomarker for early diagnosis of diabetic kidney disease and prediction of renal outcome.

Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) represents another potential podocyte-derived biomarker that has been implicated in DN. It is constitutively expressed in the podocytes, and autocrine/paracrine VEGF-A signaling occurs between podocytes and adjacent glomerular endothelial cells, which express the VEGF receptors, VEGFR-1 (Flt-1) and VEGFR-2 (KDR/Flk-1). In diabetes, particularly in the early stages of development of diabetic kidney disease, an upregulation of VEGF-A expression has been demonstrated and is paralleled by an increase in urinary protein levels of VEGF and the soluble form of VEGFR-1 (sFlt-1) in type 2 diabetic patients with microalbuminuria [29]. Urinary excretion of VEGF was significantly higher in the diabetic groups, even at the normoalbuminuric stage, compared to the nondiabetic healthy control group, and urinary VEGF levels increased as DN advanced [29]. This suggests that urinary VEGF might be useful as a sensitive marker of DN, particularly during the earlier stage and for predicting disease progression.

Glomerular endothelial injury

Endothelial dysfunction has long been implicated as a major mechanism for diabetic kidney disease and other microvascular complications in diabetes [30]. Recent investigations have demonstrated that glomerular endothelial cells have on the luminal surface a gel-like layer of glycocalyx covering the fenestrae. The endothelial glycocalyx, comprising of proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains and sialoglycoproteins, has an important barrier function with albumin-restricting ability [31]. Heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate represent the majority of the sulfated GAG chains in the endothelial glycocalyx. Hyperglycemia has been shown to result in endothelial glycocalyx damage through reduced synthesis of GAGs by the glomerular endothelial cells. Damage to the endothelial glycocalyx disrupts normal microvascular permeability and is associated with the onset of microalbuminuria in diabetic patients [31, 32]. Studies show that diabetic patients excrete significantly more GAGs than the control group [32]. Moreover, increased urinary GAGs have been detected in patients with microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria, and positively correlated with the duration of DN [33].

The assessment of urinary GAG levels could potentially be a good marker for diabetic kidney disease. In particular, it may be useful for determining endothelial dysfunction in the early stages of DN and the progression of the disease. However, there are a number of points that need to be considered. While some studies reported increased urinary GAGs in diabetics including normoalbuminuric patients, others have reported either no significant differences between normoalbuminuric diabetics and healthy nondiabetic control subjects, or a decrease in GAG excretion with increase in urinary albumin excretion [34]. It should be noted that GAGs are also major components of basement membranes including the tubular basement membrane. Studies show a correlation between urinary GAG excretion and urinary markers of tubular damage, such as Tamm-Horsfall protein [34]. These findings suggest that excretion of GAG may actually reflect tubular dysfunction in diabetic patients.

Glomerular/tubular basement membrane and extracellular matrix proteins

Type IV collagen is a high-molecular-weight protein (approximately 540 kDa) that forms a major component of the glomerular and tubular basement membranes and the mesangial matrix, and is not normally filtered through the glomerulus [35]. Urinary type IV collagen has been shown to be significantly elevated in type 2 diabetic patients, compared with healthy nondiabetic individuals, which correlates with the degree of albuminuria, and in normoalbuminuric diabetic patients evidence indicates that increases in urinary type IV collagen levels may precede the appearance of microalbuminuria [35–37]. Moreover, recent studies report a correlation between high urinary type IV collagen excretion and the annual decline in eGFR in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes without overt proteinuria [38, 39]. Hence, the urinary excretion of type IV collagen may be useful as an earlier biomarker than albuminuria in DN. However, it remains unclear whether it would prove to be a reliable predictor of progression of kidney function decline in diabetic patients, rather than a mere association.

It is well established that the hallmark of DN is the excessive production and accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins in the mesangium and basement membrane of the glomerulus. Besides type IV collagen, studies suggest that urinary mRNA levels of fibronectin, α-smooth muscle actin, and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 might be novel biomarkers of diabetic kidney disease [40]. Urinary MMP activities were noted to be increased in adolescents aged 12–19 years with early stages of type 1 diabetes [41]. Fibronectin is an intrinsic component of the glomerular extracellular matrix. Its expression is increased in DN, and urinary fibronectin has been shown to be increased in type 1 diabetic patients with macroalbuminuria, and in type 2 diabetic patients with microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria [42, 43]. However, it remains uncertain whether urinary fibronectin might be a clinically useful biomarker of early DN, and further studies are necessary to determine its potential superiority compared to microalbuminuria.

Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β is a potent inducer of extracellular matrix proteins and is generally regarded as a central mediator in the pathogenesis of DN. TGF-β-induced protein h3 (βig-h3) is an extracellular matrix protein that has been used to assess the biological activity of TGF-β in the kidney [44]. The ratio of βig-h3 to creatinine in urine was noted to be elevated in type 2 diabetic patients with normoalbuminuria (101.6±9.27), microalbuminuria (120.2±14.48) and overt proteinuria (146.3±16.34), compared with healthy control subjects (64.8±7.14) [45]. Urinary excretion of βig-h3 was significantly higher in the diabetics compared to controls, even in the normoalbuminuric stage, and urinary βig-h3 levels increased significantly as diabetic nephropathy advanced [46]. Together, these studies suggest that longitudinal monitoring of urinary βig-h3 may detect DN at an earlier stage, and βig-h3 could be a sensitive marker of diabetic kidney disease progression. Urinary levels of TGF-β were increased in type 2 diabetic patients compared with nondiabetic controls [47] and in young type 1 diabetic patients [48], and patients with DN had higher urinary TGF-β1 levels compared to normoalbuminuric patients with diabetes and healthy controls [49]. In patients with type 2 diabetes, increased urinary TGF-β1 excretion correlated with albuminuria and mesangial expansion [50], suggesting that urinary TGF-β concentration might be a useful marker of renal TGF-β expression and diabetic kidney disease. However, the results of prospective studies to assess the prognostic value of urinary TGF-β1 have been mixed. One report concluded that urinary TGF-β1 predicted the rate of renal function decline and progression of diabetic nephropathy after a mean follow-up of 2 years [51], whereas another did not [52]. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) has emerged as an important modulator of pro-fibrotic TGF-β activities and promotes renal fibrosis. A large cross-sectional study of 318 type 1 diabetic patients found that urinary CTGF levels correlated with urinary albumin excretion and increased in those with DN [53]. A subsequent prospective study of type 1 and type 2 diabetics followed for 6 years demonstrated that urinary CTGF levels correlated with the progression of microalbuminuria, demonstrating its potential usefulness as a prognostic biomarker for early progression of diabetic nephropathy [54].

Cystatin C

Cystatin C, a cysteine protease inhibitor, is a 13 kDa protein that is freely filtered by the glomerulus and has been identified as a promising marker to estimate GFR. Serum cystatin C has been shown to be more accurate than serum creatinine in the overall estimation of GFR in type 2 diabetic patients [55] and urinary cystatin C has been associated with the decline of eGFR [56]. A recent prospective study in type 2 diabetics demonstrated that there was a significant association of increases in urinary cystatin C with a decline in GFR, particularly at the early stages of nephropathy in patients with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2, and correlated with progression to CKD stage 3 or greater [56]. These findings suggest that urinary cystatin C may be a sensitive biomarker for early detection and predicting progression of kidney impairment in type 2 diabetic patients. Further studies are needed in larger cohorts and longer follow-up periods to confirm the findings. It should also be noted that the filtered cystatin C is almost entirely reabsorbed in the proximal tubule, as with other low molecular weight proteins, with virtually no tubular secretion of cystatin C, and as such, increases in urinary cystatin C, independent of serum cystatin C, suggest renal tubular damage rather than solely glomerular damage [57]. Other biomarkers of tubular damage will be discussed below.

Biomarkers of tubular damage

Although the importance of the glomerular filtration barrier in the development of albuminuria and diabetic kidney disease is well known, it has been suggested that the rate of decline in kidney function correlates better with the degree of tubular injury and tubulointerstitial fibrosis [58]. Furthermore, recent studies have renewed interest in the role of the proximal tubule reabsorption of urinary albumin in the glomerular filtrate. They suggest that albumin filtration under physiologic conditions is greater than previously determined, and that proximal tubule cell (PTC) damage alone can lead to the development of albuminuria [59]. The proximal tubule may play a greater role in the development of albuminuria than previously thought, and hence, some markers of tubular damage may be more sensitive than microalbuminuria during the very early stages of diabetic nephropathy, independent of defects in glomerular permeability [60].

Receptor-mediated endocytosis via clathrin-coated vesicles is a central mechanism responsible for protein reabsorption in the proximal tubule [61]. This process involves two apical membrane receptors, megalin and cubilin, that interact with high affinity. Megalin is an approximately 600 kDa transmembrane protein belonging to the LDL receptor family, and cubilin is a slightly smaller peripheral membrane protein, approximately 460 kDa, also known as the intrinsic factor-cobalamin receptor [61, 62]. Most proteins that are filtrated through glomeruli have been identified as ligands of megalin, cubilin, or both. Albumin binds both megalin and cubilin. Cubilin is required for the uptake of albumin by PTCs, and megalin drives endocytosis of the cubilin-albumin complex [62]. Studies by Thrailkill et al demonstrated that urinary megalin and cubilin excretion was significantly elevated in microalbuminuric patients with type 1 diabetes, resulting from proximal tubule shedding of these proteins, possibly by enhanced MMP activity in the diabetic kidney [63]. Ogasawara et al subsequently demonstrated that urinary full-length form of megalin was increased in correlation with the severity of DN in patients with type 2 diabetes [64]. In this study, the urine levels of megalin in normoalbuminuric patients were significantly higher (39% over the normal cut-off value) than those in normal control individuals, implying that the urinary megalin assay is sufficiently sensitive for the early diagnosis or prediction of the development of DN. Larger prospective cohort studies are needed to confirm the utility of megalinuria or cubilinuria as predictive markers for early diabetic kidney disease.

Low molecular weight plasma proteins whose excretion in the urine is increased due to deficient tubular reabsorption have also been described as biomarkers of tubular damage. Increased urinary excretion of α1-microglobulin [65] and retinol-binding protein [66] has been reported in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with healthy control subjects. Both α1-microglobulin and retinol-binding protein are low molecular weight proteins and their unbound forms are freely filtered and are then reabsorbed by the PTCs. Reduction in proximal tubule function results in increased excretion of these proteins in urine. Moreover, urinary levels of both α1-microglobulin and retinol-binding protein were elevated in some normoalbuminuric patients with diabetes [65–67]. However, serum levels can affect urinary levels of α1-microglobulin and retinol-binding protein and their predictive value to detect early DN is not enough to replace microalbuminuria.

Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), a member of the lipocalin family, was originally identified as a 25 kDa protein that is covalently associated with gelatinase from human neutrophils. NGAL is produced in the distal nephron, and upregulated in response to kidney injury [68]. Kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1), a type 1 transmembrane protein present on the apical membrane of PTCs, is also upregulated in acute kidney injury. Both urine NGAL and urine KIM-1 were elevated in patients with type 1 diabetes, with or without albuminuria, indicating tubular damage at an early stage [69], and higher urine NGAL and urine KIM-1 levels were predictive of a faster decline in eGFR in patients with type 2 diabetes [70]. A recent cross-sectional study to investigate the prevalence of tubular damage in the early stage (less than five years) of type 2 diabetes demonstrated that urine NGAL and urine KIM-1 levels were significantly increased in the diabetic group, compared with the control group [71]. Moreover, urine NGAL showed stronger positive correlation with urine albumin/creatinine ratio and a negative correlation with eGFR, whereas urine KIM-1 showed no significant difference among the three diabetic groups (normoalbuminuria, microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria), and did not correlate with either urine albumin/creatinine ratio or eGFR [71]. These findings indicate that tubular damage is relatively common at the early stage of type 2 diabetes, and that urine NGAL may be a promising biomarker for early detection and monitoring of kidney impairment in type 2 diabetes.

Biomarkers of oxidative stress

Oxidative stress is well recognized as an important causative factor in the development of DN. Hyperglycemia and the diabetic milieu induce cellular superoxide overproduction and the activation of pathways associated with the pathogenesis of diabetes complications such as polyol pathway activation, advanced glycation end-product overproduction, and the activation of protein kinase C isoforms [72]. 8-Hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) and 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-oxodG) are products of oxidative DNA damage that are freely filtered, and thus their urinary levels serve as an index of systemic oxidative stress [73]. Urinary excretion of 8-OHdG is markedly increased in patients with type 2 diabetes compared to healthy control subjects, and a high level of urinary 8-OHdG was associated with high glycosylated hemoglobin [73] as well as the severity of the tubulointerstitial lesion [72]. Moreover, a prospective longitudinal study demonstrated that elevated urinary 8-oxodG excretion at baseline was associated with the development of nephropathy 5 years later, and urinary 8-oxodG was identified as the strongest predictor for development of the complication among several risk factors examined [74]. Significant correlation was seen between higher excretion of 8-oxodG in urine and progression of DN [74, 75]. Taken together, these studies indicate that urinary 8-OHdG and 8-oxodG may be useful biomarkers to predict the development of DN. However, conflicting results were noted in a more recent study. While urine 8-OHdG levels were increased in diabetic patients, the study found that urine 8-OHdG was not a useful clinical marker, compared with urine albumin/creatinine ratio, in predicting the patients at risk of developing DN [76].

Biomarkers of inflammation

Growing evidence indicates that immunologic and inflammatory mechanisms play a significant role in disease development and progression in DN. Studies suggest that individuals who develop diabetic kidney disease have low-grade inflammation years before the onset of the disease, and that elevated excretion of inflammatory markers in urine was associated with early progressive renal function decline in type 1 diabetic patients [77]. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) is a key mediator of inflammation and a major participant in the pathogenesis of kidney injury by promoting inflammation, apoptosis, and accumulation of extracellular matrix, reducing GFR and increasing albumin permeability. Although activated macrophages are the major source of TNF-α, intrinsic renal cells are also able to express TNF-α and contribute to renal injury [78]. Recent investigation revealed that increases in urinary TNF-α excretion were seen in patients with type 2 diabetes compared to control subjects, and were associated with urinary albumin excretion, and correlated with the severity of DN [79]. Together, these results indicate that TNF-α may have potential as a useful urinary biomarker for DN.

Biomarkers of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system

An activated intrarenal renin-angiotensin system (RAS) has been implicated to play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of DN. It is widely thought that blockade of components of the RAS with the use of drugs such as an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, through inhibition with local production and/or local effects of angiotensin II, exerts renoprotective effects [80]. Angiotensinogen (AGT) is constitutively secreted in the proximal straight tubule, and because AGT is the only known substrate for renin, increased intrarenal AGT levels contribute to angiotensin II generation [81]. Studies have shown that urinary AGT is highly correlated to renal tissue expression of angiotensin II and therefore, a potentially suitable marker of intrarenal RAS activity [82, 83]. Moreover, urinary AGT is associated with increased risk for deterioration of renal function in patients with CKD and thus predictive of GFR loss in longitudinal studies [83].

In a recent study, van den Heuvel and colleagues demonstrated that urine renin levels were increased in diabetic patients, and that treatment with ACE inhibitor and/or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) reduced urinary renin, but not AGT, despite elevated plasma renin levels [84]. These results indicate that urinary renin reflects the renal RAS activity and the efficacy of RAS blockade in the kidney. Further studies show that the urine/plasma ratio of renin was more than 100-fold higher than that of AGT and albumin, and 4-fold reduced by single RAS blockade, and more than 10-fold by dual RAS blockade [85]. In contrast, reductions in urinary AGT paralleled albuminuria changes, and the urine/plasma ratio of AGT was identical to that of albumin under all conditions, suggesting that urinary AGT is a marker of filtration barrier damage rather than intrarenal RAS activity [85]. These findings suggest that the urine/plasma renin ratio, and not urine renin alone, may reflect the renal efficacy of RAS blockade, and can serve as a very sensitive early marker of intrarenal RAS activation and DN.

Urinary microRNA (miRNA)

In recent years, a novel class of naturally occurring short non-coding RNA called microRNA (miRNA) has emerged as important post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression, capable of regulating numerous biological functions. There has been considerable attention recently focusing on the role of miRNAs as mediators or biomarkers of diseases, including DN. It is also noteworthy that most miRNAs that have been implicated in nephropathy are regulated by the profibrotic cytokine TGF-β [86]. The use of urinary miRNA as biomarkers of kidney disease is currently being actively investigated. A recent study by Szeto et al examined the urinary miRNA expression profiles in patients with CKD from various etiologies, including IgA nephropathy, diabetes and hypertension, and found that they differed between the groups [87]. Patients with diabetic glomerulosclerosis had lower urinary miR-15 expression than the other groups. In addition, urinary miR-21 and miR-216a expression correlated with the rate of kidney function decline and risk of progression to dialysis-dependent kidney failure regardless of the type of CKD [87]. Argyropoulos et al identified a set of 27 differentially expressed miRNAs in urine samples from patients with type 1 diabetes in different stages of DN whose renal outcomes had been ascertained after >20 year follow-up [88]. Although these studies bear limitations, including the relatively low number of patients studied and differences in therapies among the patients, such as receiving or not receiving ACE inhibitors and/or ARBs, the results underscore the potential value of urinary miRNAs as molecular signatures associated with distinct clinical stages of diabetic kidney disease and suggest the possibility that changes in miRNA expression may be early indications of kidney injury in diabetes. Further investigations that include larger cohorts are still necessary to determine whether urinary miRNA expression profiles would prove to be ideal biomarkers for early diagnosis and risk stratification of DN.

Urine proteomics

Proteomics is a method aimed at large-scale study of proteins that allows a simultaneous examination of the patterns of multiple urinary and plasma proteins. Urine proteome analysis is rapidly emerging as a tool for diagnosis and prognosis in disease states, and the technology of high-resolution protein separation by capillary electrophoresis together with mass spectrometry allows for the unbiased search for potential new biomarkers. Recent studies using this approach identified a set of biomarkers for DN with a sensitivity and specificity of 97% in type 1 diabetic patients [89], and 93.8% sensitivity and 91.4% specificity in type 2 diabetics [90]. These studies identified urinary proteomic biomarkers that are distinct for patients who had microalbuminuria and diabetes and who subsequently progressed toward overt DN, and allow early detection of DN, or discrimination from other nondiabetic CKD, or prediction of normoalbuminuric diabetic patients prone to develop DN [89, 90]. However, these studies defined DN exclusively on the clinical basis of presence of macroalbuminuria with or without a decline of eGFR, but without histological verification. Studies by Papale et al used the technique of surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionization-time of flight/mass spectrometry (SELDI-TOF/MS) to determine a urine proteomic fingerprint defining a set of biomarkers able to reliably identify biopsy-proven DN in type 2 diabetic patients and differentiate DN from nondiabetic CKD in both patients with and without diabetes [91].

To evaluate urinary proteome analysis as a tool for prediction of DN, Zürbig et al examined urine samples from a longitudinal cohort of patients with type 1 and 2 diabetes using a previously generated CKD biomarker classifier and capillary-electrophoresis/mass spectrometry to assess the low–molecular weight proteome, referred to as the “peptidome” [92]. The application of the classifier system was able to identify normoalbuminuric subjects that 5 years later developed macroalbuminuria and was superior in this regard to microalbuminuria as a predictor and enabled the early detection of subsequent progression to macroalbuminuria [92]. Interestingly, many of the biomarkers were fragments of collagen type I, and quantities were reduced in patients with diabetes or DN. The decrease in collagen fragments preceded increase in albumin excretion 3–5 years before the onset of macroalbuminuria, suggesting the importance of extracellular matrix changes and collagen turnover may be indicative of the molecular pathophysiology of diabetes [92]. A recent prospective case-control study examined the value of a urinary proteomic-based risk score, or classifier, in predicting the development and progression of microalbuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes based on 273 urinary peptides [93]. The study found that the proteomic classifier was independently associated with the transition to microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria, and predicted the progression of albuminuria. Altogether, urinary proteomic-based biomarker discovery represents a novel strategy to identify earlier and more specific biomarkers than urinary albumin and enable early renal risk assessment in patients with diabetes.

Conclusion

Over the last couple of decades, there has been tremendous interest in the discovery of biomarkers of DN that allow for the detection of early stages of DN and progressive kidney function decline in diabetic patients. Recent studies have highlighted some promising new biomarkers including plasma concentrations of TGF-β to bone morphogenetic protein-7 (BMP-7) ratio [94] and TNF receptors 1 and 2 (TNFR1 and TNFR2) [95, 96]. A number of new and important biomarkers present in the urine have also emerged. However, in clinical practice, they have yet to replace the use of microalbuminuria, which remains the gold standard for detecting diabetic kidney disease.

Some of the clinical studies exploring the urinary biomarkers associated with diabetic kidney disease are discussed in this review, and are summarized in Table 1. Limitations of the majority of these studies include their small sample size, or their cross-sectional or short-term prospective nature. Various biomarker detection methods were employed. The majority of the biomarkers were assayed by immunoassays, primarily ELISA. The strategies to determine urinary mRNA profiles, such as in the studies of podocyte-associated molecules (podocalyxin, synaptopodin, α-actinin-4, podocin) [25, 28] and expression levels such as TNF-α [79], by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) may be limited by the susceptibility for mRNA degradation by the presence of RNAses The analysis of biomarkers of renal injury in urinary exosomes represents an alternative approach. Exosomes can be recovered from the urine by differential centrifugation as a low-density membrane fraction. The use of exosome isolation provides an advantage for detection of low-abundance urinary proteins by allowing marked (>30-fold) enrichment of constituent proteins, including intracellular proteins and transcription factors such as WT1 [21]. The newer molecular technologies such as quantitative PCR (qPCR) to detect urine miRNAs [88] and urine proteomics are associated with increased costs. Nevertheless, the utilization of urinary biomarkers might be a sensitive, noninvasive and clinically useful method that is particularly attractive given that urine is an easily available source. Future efforts should be directed at both new urinary biomarker discovery and validation, as well as larger longitudinal prospective studies to confirm the utility of the biomarkers that would be reliable earlier, more predictive and prognostic markers of diabetic kidney disease and progression.

Table 1.

Clinical studies of urinary biomarkers associated with diabetic kidney disease.

| Biomarkers | Study population |

Study type | Key results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albumin | T1DM | Longitudinal | 29% with new-onset microalbuminuria developed advanced CKD, independent of progression to proteinuria | [3] |

| T2DM | Longitudinal | Progression to microalbuminuria and macroalbuminemia at 2% and 2.8% per year, respectively. Prevalence of microalbuminuria was 25% after 10 years of follow-up, macroalbuminuria was 5.3% | [4] | |

| Transferrin | T2DM | Longitudinal | Predictive of future development of microalbuminuria, higher urinary transferrin levels in patients who progressed to microalbuminuria | [15, 16] |

| T1DM | Cross-sectional | Urinary transferrin levels correlated with urinary albumin excretion | [17] | |

| Nephrin | T1DM | Cross-sectional | Present in 30% of normoalbuminuric diabetic patients, 28% of new-onset microalbuminuria, and none of the nondiabetic controls | [20] |

| T2DM | Cross-sectional | Present in 100% of diabetic patients with micro- and macroalbuminuria, and 54% of patients with normoalbuminuria | [23] | |

| Podocalyxin | T2DM | Cross-sectional | Elevated in 53.8% patients at normoalbuminuric stage, 64.7% at microalbuminuric stage and 66.7% at macroalbuminuric stage | [24] |

| Podocin, α-actinin-4, Synaptopodin | T2DM | Cross-sectional | Urinary mRNA profiles of podocin, α-actinin-4, and synaptopodin correlated with urinary albumin | [25, 26] |

| WT1 | T1DM | Cross-sectional | Urinary exosomal WT1 protein levels correlated with increased urine albumin/creatinine ratio, serum creatinine, and decline in eGFR | [21] |

| VEGF-A | T2DM | Cross-sectional | Elevated in microalbuminuric and proteinuric diabetic patients, and correlated with urine albumin/creatinine ratio | [29] |

| GAG | T1/T2DM | Cross-sectional | Elevated in diabetic patients with microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria, and positively correlated with the duration of DN | [33] |

| Collagen IV | T2DM | Longitudinal/Cross-sectional | Elevated in diabetic patients, correlated weakly with urine albumin/creatinine ratios | [36, 37] |

| Collagen I fragments | T1/T2DM | Longitudinal | Decrease in collagen fragments preceded increase in albumin excretion 3–5 years before the onset of macroalbuminuria | [92] |

| MMP-9 | T1DM | Cross-sectional | Elevated MMP-9 activities in adolescents with early stages of T1DM | [41] |

| T2DM | Cross-sectional | Elevated urinary mRNA levels in DN and positively correlated with both urinary albumin excretion and serum creatinine | [40] | |

| Fibronectin | T1DM | Cross-sectional | Elevated in diabetic patients with macroalbuminuria | [42] |

| T2DM | Cross-sectional | Elevated in diabetics with microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria | [43] | |

| TGF-β | T1DM | Cross-sectional | Elevated in diabetic patients | [48] |

| T2DM | Cross-sectional | Correlated with albuminuria and mesangial expansion | [47, 50] | |

| βig-h3 | T2DM | Cross-sectional | Elevated in diabetic patients even in the normoalbuminuric stage | [45, 46] |

| CTGF | T1DM | Cross-sectional | Correlated with urinary albumin excretion and increased with DN | [53] |

| T1/T2DM | Longitudinal | Correlated with progression of microalbuminuria | [54] | |

| Cystatin C | T2DM | Longitudinal | Correlated with decline in GFR | [56] |

| Cubulin | T1DM | Cross-sectional | Increased cubulin and megalin in microalbuminuric diabetic patients | [63] |

| Megalin | T2DM | Cross-sectional | Increased full-length megalin correlate with the severity of DN | [64] |

| α1-MG | T2DM | Cross-sectional | Correlated with albuminuria, duration, severity, control of diabetes | [65] |

| RBP | T1DM | Longitudinal | Elevated in diabetic patients with macroalbuminuria and normoalbuminuria, 4.2% of normoalbuminuric diabetic patients developed persistent microalbuminuria at 30–36 months of follow-up | [66] |

| NGAL, KIM-1 | T1DM | Cross-sectional | Both are elevated in diabetic patients with and without albuminuria | [69] |

| T2DM | Longitudinal | Higher levels were predictive of a faster decline in eGFR | [70] | |

| T2DM | Cross-sectional | Both are elevated in early stage (<5 years) of diabetes. Urine NGAL with stronger positive correlation with urine albumin/creatinine ratio | [71] | |

| 8-OHdG, 8-oxodG | T2DM | Longitudinal | High urinary excretion at baseline was associated with the development of nephropathy 5 years later | [74] |

| TNF-α | T2DM | Cross-sectional | Correlated with urinary albumin excretion, and the severity of DN | [79] |

| Renin | T1/T2DM | Cross-sectional | Increased in diabetic patients, treatment with ACE inhibitor and/or ARB reduced urinary renin, despite elevated plasma renin levels | [84] |

| miRNAs | T1DM | Historical cohort | Urinary microRNA profiles differ across the different stages of DN whose renal outcomes were ascertained after >20 year follow-up | [88] |

Abbreviations: α1-microglobulin, α1-MG; Retinol-binding protein, RBP; T1DM, type 1 diabetes; T2DM, type 2 diabetes

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grants R01-DK57661, R01-HL079904, and P01-HL114501 to M.E.C.

References

- 1.Imperatore G, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Case D, Dabelea D, Hamman RF, Lawrence JM, Liese AD, Liu LL, Mayer-Davis EJ, Rodriguez BL, Standiford D SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study Group. Projections of type 1 and type 2 diabetes burden in the U.S. population aged <20 years through 2050: dynamic modeling of incidence, mortality, and population growth. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2515–2520. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanton RC. Frontiers in diabetic kidney disease: introduction. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(2) Suppl 2:S1–S2. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perkins BA, Ficociello LH, Roshan B, Warram JH, Krolewski AS. In patients with type 1 diabetes and new-onset microalbuminuria the development of advanced chronic kidney disease may not require progression to proteinuria. Kidney Int. 2010;77:57–64. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adler AI, Stevens RJ, Manley SE, Bilous RW, Cull CA, Holman RR UKPDS GROUP. Development and progression of nephropathy in type 2 diabetes: the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS 64) Kidney Int. 2003;63:225–232. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zachwieja J, Soltysiak J, Fichna P, Lipkowska K, Stankiewicz W, Skowronska B, Kroll P, Lewandowska-Stachowiak M. Normal-range albuminuria does not exclude nephropathy in diabetic children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:1445–1451. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1443-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fioretto P, Steffes MW, Mauer M. Glomerular structure in nonproteinuric IDDM patients with various levels of albuminuria. Diabetes. 1994;43:1358–1364. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.11.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer HJ, Nguyen QD, Curhan G, Hsu CY. Renal insufficiency in the absence of albuminuria and retinopathy among adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2003;289:3273–3277. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.24.3273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacIsaac RJ, Tsalamandris C, Panagiotopoulos S, Smith TJ, McNeil KJ, Jerums G. Nonalbuminuric renal insufficiency in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:195–200. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Araki S, Haneda M, Sugimoto T, Isono M, Isshiki K, Kashiwagi A, Koya D. Factors associated with frequent remission of microalbuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:2983–2987. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.10.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glassock RJ. Is the presence of microalbuminuria a relevant marker of kidney disease? Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12:364–368. doi: 10.1007/s11906-010-0133-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis EJ, Xu X. Abnormal glomerular permeability characteristics in diabetic nephropathy: implications for the therapeutic use of low-molecular weight heparin. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(Suppl 2):S202–S207. doi: 10.2337/dc08-s251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Memişoğullari R, Bakan E. Levels of ceruloplasmin, transferrin, and lipid peroxidation in the serum of patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 2004;18:193–197. doi: 10.1016/S1056-8727(03)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narita T, Sasaki H, Hosoba M, Miura T, Yoshioka N, Morii T, Shimotomai T, Koshimura J, Fujita H, Kakei M, Ito S. Parallel increase in urinary excretion rates of immunoglobulin G, ceruloplasmin, transferrin, and orosomucoid in normoalbuminuric type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1176–1181. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheung CK, Cockram CS, Yeung VT, Swaminathan R. Urinary excretion of transferrin by non-insulin-dependent diabetics: a marker for early complications? Clin Chem. 1989;35:1672–1674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kazumi T, Hozumi T, Ishida Y, Ikeda Y, Kishi K, Hayakawa M, Yoshino G. Increased urinary transferrin excretion predicts microalbuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1176–1180. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.7.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Narita T, Hosoba M, Kakei M, Ito S. Increased urinary excretions of immunoglobulin G, ceruloplasmin, and transferrin predict development of microalbuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:142–144. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.1.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin P, Walton C, Chapman C, Bodansky HJ, Stickland MH. Increased urinary excretion of transferrin in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 1990;7:35–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1990.tb01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackinnon B, Shakerdi L, Deighan CJ, Fox JG, O'Reilly DS, Boulton-Jones M. Urinary transferrin, high molecular weight proteinuria and the progression of renal disease. Clin Nephrol. 2003;59:252–258. doi: 10.5414/cnp59252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su J, Li SJ, Chen ZH, Zeng CH, Zhou H, Li LS, Liu ZH. Evaluation of podocyte lesion in patients with diabetic nephropathy: Wilms' tumor-1 protein used as a podocyte marker. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pätäri A, Forsblom C, Havana M, Taipale H, Groop PH, Holthofer H. Nephrinuria in diabetic nephropathy of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:2969–2974. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.12.2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalani A, Mohan A, Godbole MM, Bhatia E, Gupta A, Sharma RK, Tiwari S. Wilm's tumor-1 protein levels in urinary exosomes from diabetic patients with or without proteinuria. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang SX, Rastaldi MP, Patari A, Ahola H, Heikkila E, Holthofer H. Patterns of nephrin and a new proteinuria-associated protein expression in human renal diseases. Kidney Int. 2002;61:141–147. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jim B, Ghanta M, Qipo A, Fan Y, Chuang PY, Cohen HW, Abadi M, Thomas DB, He JC. Dysregulated nephrin in diabetic nephropathy of type 2 diabetes: a cross sectional study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36041. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hara M, Yamagata K, Tomino Y, Saito A, Hirayama Y, Ogasawara S, Kurosawa H, Sekine S, Yan K. Urinary podocalyxin is an early marker for podocyte injury in patients with diabetes: establishment of a highly sensitive ELISA to detect urinary podocalyxin. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2913–2919. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2661-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng M, Lv LL, Ni J, Ni HF, Li Q, Ma KL, Liu BC. Urinary podocyte-associated mRNA profile in various stages of diabetic nephropathy. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wickman L, Afshinnia F, Wang SQ, Yang Y, Wang F, Chowdhury M, Graham D, Hawkins J, Nishizono R, Tanzer M, Wiggins J, Escobar GA, Rovin B, Song P, Gipson D, Kershaw D, Wiggins RC. Urine podocyte mRNAs, proteinuria, and progression in human glomerular diseases. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:2081–2095. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013020173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nielsen JS, McNagny KM. The role of podocalyxin in health and disease. J Am Soc Neph. 2009;20:1669–1676. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kubo K, Miyagawa K, Yamamoto R, Hamasaki K, Kanda H, Fujita T, Yamamoto K, Yazaki Y, Mimura T. Detection of WT1 mRNA in urine from patients with kidney diseases. Eur J Clin Invest. 1999;29:824–826. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1999.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim NH, Oh JH, Seo JA, Lee KW, Kim SG, Choi KM, Baik SH, Choi DS, Kang YS, Han SY, Han KH, Ji YH, Cha DR. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and soluble VEGF receptor FLT-1 in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2005;67:167–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karalliedde J, Gnudi L. Endothelial Factors and Diabetic Nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:S291–S296. doi: 10.2337/dc11-s241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh A, Fridén V, Dasgupta I, Foster RR, Welsh GI, Tooke JE, Haraldsson B, Mathieson PW, Satchell SC. High glucose causes dysfunction of the human glomerular endothelial glycocalyx. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300:F40–F48. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00103.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nieuwdorp M, Mooij HL, Kroon J, Atasever B, Spaan JA, Ince C, Holleman F, Diamant M, Heine RJ, Hoekstra JB, Kastelein JJ, Stroes ES, Vink H. Endothelial glycocalyx damage coincides with microalbuminuria in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2006;55:1127–1132. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Popławska-Kita A, Mierzejewska-Iwanowska B, Szelachowska M, Siewko K, Nikołajuk A, Kinalska I, G�rska M. Glycosaminoglycans urinary excretion as a marker of the early stages of diabetic nephropathy and the disease progression. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24:310–317. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torffvit O. Urinary sulphated glycosaminoglycans and Tamm-Horsfall protein in type 1 diabetic patients. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1999;33:328–332. doi: 10.1080/003655999750017428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iijima T, Suzuki S, Sekizuka K, Hishiki T, Yagame M, Jinde K, Saotome N, Suzuki D, Sakai H, Tomino Y. Follow-up study on urinary type IV collagen in patients with early stage diabetic nephropathy. J Clin Lab Anal. 1998;12:378–382. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2825(1998)12:6<378::AID-JCLA8>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kotajima N, Kimura T, Kanda T, Obata K, Kuwabara A, Fukumura Y, Kobayashi I. Type IV collagen as an early marker for diabetic nephropathy in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 2000;14:13–17. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(00)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cawood TJ, Bashir M, Brady J, Murray B, Murray PT, O'Shea D. Urinary collagen IV and πGST: potential biomarkers for detecting localized kidney injury in diabetes—a pilot study. Am J Nephrol. 2010;32:219–225. doi: 10.1159/000317531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morita M, Uchigata Y, Hanai K, Ogawa Y, Iwamoto Y. Association of urinary type IV collagen with GFR decline in young patients with type 1 diabetes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58:915–920. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Araki S, Haneda M, Koya D, Isshiki K, Kume S, Sugimoto T, Kawai H, Nishio Y, Kashiwagi A, Uzu T, Maegawa H. Association between urinary type IV collagen level and deterioration of renal function in type 2 diabetic patients without overt proteinuria. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1805–1810. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng M, Lv LL, Cao YH, Zhang JD, Wu M, Ma KL, Phillips AO, Liu BC. Urinary mRNA markers of epithelial mesenchymal transition correlate with progression of diabetic nephropathy. Clin Endocinol. 2012;76:657–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKittrick IB, Bogaert Y, Nadeau K, Snell-Bergeon J, Hull A, Jiang T, Wang X, Levi M, Moulton KS. Urinary matrix metalloproteinase activities: biomarkers for plaque angiogenesis and nephropathy in diabetes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;301:F1326–F1333. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00267.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fagerudd JA, Groop PH, Honkanen E, Teppo AM, Gronhagen-Riska C. Urinary excretion of TGF-β1, PDGFBB and fibronectin in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus patients. Kidney Int. 1997;51:S195–S197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takahashi M. Increased urinary fibronectin excretion in type II diabetic patients with microalbuminuria. Nihon Jinzo Gakkai Shi. 1995;37:336–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gilbert RE, Wilkinson BJL, Johnson DW, Cox J, Soulis T, Wu LL, Kelly DJ, Jerums G, Pollock CA, Cooper ME. Renal expression of transforming growth factor-β-inducible gene-h3 (βig-h3) in normal and diabetic rats. Kidney Int. 1998;54:1052–1062. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ha SW, Kim HJ, Bae JS, Jeong GH, Chung SC, Kim JG, Park SH, Kim YL, Kam S, Kim IS, Kim BW. Elevation of urinary βig-h3, transforming growth factor-β-induced protein in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2004;65:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cha DR, Kim IS, Kang YS, Han SY, Han KH, Shin C, Ji YH, Kim NH. Urinary concentration of transforming growth factor-β-inducible gene-h3(βig-h3) in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2005;22:14–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharma K, Ziyadeh FN, Alzahabi B, McGowan TA, Kapoor S, Kurnik BR, Kurnik PB, Weisberg LS. Increased renal production of transforming growth factor-beta1 in patients with type II diabetes. Diabetes. 1997;46:854–859. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.5.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Korpinen E, Teppo AM, Hukkanen L, Akerblom HK, Grönhagen-Riska C, Vaarala O. Urinary transforming growth factor-beta1 and alpha1-microglobulin in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:664–668. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.5.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gilbert RE, Akdeniz A, Allen TJ, Jerums G. Urinary transforming growth factor-β in patients with diabetic nephropathy: implications for the pathogenesis of tubulointerstitial pathology. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:2442–2443. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.12.2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sato H, Iwano M, Akai Y, Kurioka H, Kubo A, Yamaguchi T, Hirata E, Kanauchi M, Dohi K. Increased excretion of urinary transforming growth factor beta 1 in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Am J Nephrol. 1998;18:490–494. doi: 10.1159/000013415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Verhave JC, Bouchard J, Goupil R, Pichette V, Brachemi S, Madore F, Troyanov S. Clinical value of inflammatory urinary biomarkers in overt diabetic nephropathy: a prospective study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;101:333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Titan SM, Vieira JM, Jr, Dominguez WV, Moreira SR, Pereira AB, Barros RT, Zatz R. Urinary MCP-1 and RBP: independent predictors of renal outcome in macroalbuminuric diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Complications. 2012;26:546–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nguyen TQ, Tarnow L, Andersen S, Hovind P, Parving HH, Goldschmeding R, van Nieuwenhoven FA. Urinary connective tissue growth factor excretion correlates with clinical markers of renal disease in a large population of type 1 diabetic patients with diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:83–88. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tam FW, Riser BL, Meeran K, Rambow J, Pusey CD, Frankel AH. Urinary monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and connective tissue growth factor (CCN2) as prognostic markers for progression of diabetic nephropathy. Cytokine. 2009;47:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kalansooriya A, Holbrook I, Jennings P, Whiting PH. Serum cystatin C, enzymuria, tubular proteinuria and early renal insult in type 2 diabetes. Br J Biomed Sci. 2007;64:121–123. doi: 10.1080/09674845.2007.11732770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim SS, Song SH, Kim IJ, Jeon YK, Kim BH, Kwak IS, Lee EK, Kim YK. Urinary cystatin C and tubular proteinuria predict progression of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:656–661. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herget-Rosenthal S, Feldkamp T, Volbracht L, Kribben A. Measurement of urinary cystatin C by particle-enhanced nephelometric immunoassay: precision, interferences, stability and reference range. Ann Clin Biochem. 2004;41:111–118. doi: 10.1258/000456304322879980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.White KE, Bilous RW. Type 2 diabetic patients with nephropathy show structural-functional relationships that are similar to type 1 disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:1667–1673. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1191667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dickson LE, Wagner MC, Sandoval RM, Molitoris BA. The proximal tubule and albuminuria: really! J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:443–453. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013090950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Russo LM, Sandoval RM, Campos SB, Molitoris BA, Comper WD, Brown D. Impaired tubular uptake explains albuminuria in early diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:489–494. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008050503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Christensen EI, Birn H. Megalin and cubilin: synergistic endocytic receptors in renal proximal tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F562–F573. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.4.F562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Amsellem S, Gburek J, Hamard G, Nielsen R, Willnow TE, Devuyst O, Nexo E, Verroust PJ, Christensen EI, Kozyraki R. Cubilin Is Essential for Albumin Reabsorption in the Renal Proximal Tubule. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1859–1867. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thrailkill KM, Nimmo T, Bunn RC, Cockrell GE, Moreau CS, Mackintosh S, Edmondson RD, Fowlkes JL. Microalbuminuria in type 1 diabetes is associated with enhanced excretion of the endocytic multiligand receptors megalin and cubilin. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1266–1268. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ogasawara S, Hosojima M, Kaseda R, Kabasawa H, Yamamoto-Kabasawa K, Kurosawa H, Sato H, Iino N, Takeda T, Suzuki Y, Narita I, Yamagata K, Tomino Y, Gejyo F, Hirayama Y, Sekine S, Saito A. Significance of urinary full-length and ectodomain forms of megalin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1112–1118. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hong CY, Hughes K, Chia KS, Ng V, Ling SL. Urinary alpha1-microglobulin as a marker of nephropathy in type 2 diabetic Asian subjects in Singapore. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:338–342. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Salem MA, el-Habashy SA, Saeid OM, el-Tawil MM, Tawfik PH. Urinary excretion of n-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase and retinol binding protein as alternative indicators of nephropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Diabetes. 2002;3:37–41. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5448.2002.30107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Koh KT, Chia KS, Tan C. Proteinuria and enzymuria in non-insulin-dependent diabetics. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1993;20:215–221. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(93)90081-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mishra J, Dent C, Tarabishi R, Mitsnefes MM, Ma Q, Kelly C, Ruff SM, Zahedi K, Shao M, Bean J, Mori K, Barasch J, Devarajan P. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a biomarker for acute renal injury after cardiac surgery. Lancet. 2005;365:1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74811-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nielsen SE, Schjoedt KJ, Astrup AS, Tarnow L, Lajer M, Hansen PR, Parving HH, Rossing P. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin (NGAL) and Kidney Injury Molecule 1 (KIM1) in patients with diabetic nephropathy: a cross-sectional study and the effects of lisinopril. Diabet Med. 2010;27:1144–1150. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nielsen SE, Reinhard H, Zdunek D, Hess G, Gutierrez OM, Wolf M, Parving HH, Jacobsen PK, Rossing P. Tubular markers are associated with decline in kidney function in proteinuric type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fu WJ, Xiong SL, Fang YG, Wen S, Chen ML, Deng RT, Zheng L, Wang SB, Pen LF, Wang Q. Urinary tubular biomarkers in short-term type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a cross-sectional study. Endocrine. 2012;41:82–88. doi: 10.1007/s12020-011-9509-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kanauchi M, Nishioka H, Hashimoto T. Oxidative DNA damage and tubulointerstitial injury in diabetic nephropathy. Nephron. 2002;91:327–329. doi: 10.1159/000058412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Leinonen J, Lehtimaki T, Toyokuni S, Okada K, Tanaka T, Hiai H, Ochi H, Laippala P, Rantalaiho V, Wirta O, Pasternack A, Alho H. New biomarker evidence of oxidative DNA damage in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. FEBS Lett. 1997;417:150–152. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hinokio Y, Suzuki S, Hirai M, Suzuki C, Suzuki M, Toyota T. Urinary excretion of 8-oxo-7, 8-dihydro-2'-deoxyguanosine as a predictor of the development of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetologia. 2002;45:877–882. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0831-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Broedbaek K, Weimann A, Stovgaard ES, Poulsen HE. Urinary 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2 deoxyguanosine as a biomarker in type 2 diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1473–1479. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Serdar M, Sertoglu E, Uyanik M, Tapan S, Akin K, Bilgi C, Kurt I. Comparison of 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) levels using mass spectrometer and urine albumin creatinine ratio as a predictor of development of diabetic nephropathy. Free Radic Res. 2012;46:1291–1295. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2012.710902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wolkow PP, Niewczas MA, Perkins B, Ficociello LH, Lipinski B, Warram JH, Krolewski AS. Association of Urinary Inflammatory Markers and Renal Decline in Microalbuminuric Type 1 Diabetics. J Am Soc Neph. 2008;19:789–797. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007050556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Timoshanko JR, Sedgwick JD, Holdsworth SR, Tipping PG. Intrinsic renal cells are the major source of tumor necrosis factor contributing to renal injury in murine crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1785–1793. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000073902.38428.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Navarro JF, Mora C, Gomez M, Muros M, Lopez-Aguilar C, Garcia J. Influence of renal involvement on peripheral blood mononuclear cell expression behaviour of tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6 in type 2 diabetic patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:919–926. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lu X, Roksnoer LC, Danser AH. The intrarenal renin-angiotensin system: does it exist? Implications from a recent study in renal angiotensin-converting enzyme knockout mice. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:2977–2982. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pohl M, Kaminski H, Castrop H, Bader M, Himmerkus N, Bleich M, Bachmann S, Theilig F. Intrarenal renin angiotensin system revisited: role of megalin-dependent endocytosis along the proximal nephron. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:41935–41946. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.150284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nishiyama A, Konishi Y, Ohashi N, Morikawa T, Urushihara M, Maeda I, Hamada M, Kishida M, Hitomi H, Shirahashi N, Kobori H, Imanishi M. Urinary angiotensinogen reflects the activity of intrarenal renin-angiotensin system in patients with IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:170–177. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yamamoto T, Nakagawa T, Suzuki H, Ohashi N, Fukasawa H, Fujigaki Y, Kato A, Nakamura Y, Suzuki F, Hishida A. Urinary angiotensinogen as a marker of intrarenal angiotensin II activity associated with deterioration of renal function in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1558–1565. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006060554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.van den Heuvel M, Batenburg WW, Jainandunsing S, Garrelds IM, van Gool JM, Feelders RA, van den Meiracker AH, Danser AH. Urinary renin, but not angiotensinogen or aldosterone, reflects the renal renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activity and the efficacy of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade in the kidney. J Hypertens. 2011;29:2147–2155. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834bbcbf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Persson F, Lu X, Rossing P, Garrelds IM, Danser AH, Parving HH. Urinary renin and angiotensinogen in type 2 diabetes: added value beyond urinary albumin? J Hypertens. 2013;31:1646–1652. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328362217c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McClelland A, Hagiwara S, Kantharidis P. Where are we in diabetic nephropathy: microRNAs and biomarkers? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014;23:80–86. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000437612.50040.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Szeto CC, Ching-Ha KB, Ka-Bik L, Mac-Moune LF, Cheung-Lung CP, Gang W, Kai-Ming C, Kam-Tao LP. Micro-RNA expression in the urinary sediment of patients with chronic kidney diseases. Dis Markers. 2012;33:137–144. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2012-0914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Argyropoulos C, Wang K, McClarty S, Huang D, Bernardo J, Ellis D, Orchard T, Galas D, Johnson J. Urinary microRNA profiling in the nephropathy of type 1 diabetes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rossing K, Mischak H, Dakna M, Zürbig P, Novak J, Julian BA, Good DM, Coon JJ, Tarnow L, Rossing P PREDICTIONS Network. Urinary proteomics in diabetes and CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1283–1290. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007091025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Alkhalaf A, Zürbig P, Bakker SJ, Bilo HJ, Cerna M, Fischer C, Fuchs S, Janssen B, Medek K, Mischak H, Roob JM, Rossing K, Rossing P, Rychl�k I, Sourij H, Tiran B, Winklhofer-Roob BM, Navis GJ PREDICTIONS Group. Multicentric validation of proteomic biomarkers in urine specific for diabetic nephropathy. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Papale M, Di Paolo S, Magistroni R, Lamacchia O, Di Palma AM, De Mattia A, Rocchetti MT, Furci L, Pasquali S, De Cosmo S, Cignarelli M, Gesualdo L. Urine proteome analysis may allow noninvasive differential diagnosis of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2409–2415. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zürbig P, Jerums G, Hovind P, Macisaac RJ, Mischak H, Nielsen SE, Panagiotopoulos S, Persson F, Rossing P. Urinary proteomics for early diagnosis in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2012;61:3304–3313. doi: 10.2337/db12-0348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Roscioni SS, de Zeeuw D, Hellemons ME, Mischak H, Zürbig P, Bakker SJ, Gansevoort RT, Reinhard H, Persson F, Lajer M, Rossing P, Lambers Heerspink HJ. A urinary peptide biomarker set predicts worsening of albuminuria in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2013;56:259–267. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2755-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wong MG, Perkovic V, Woodward M, Chalmers J, Li Q, Hillis GS, Yaghobian Azari D, Jun M, Poulter N, Hamet P, Williams B, Neal B, Mancia G, Cooper M, Pollock CA. Circulating bone morphogenetic protein-7 and transforming growth factor-β1 are better predictors of renal end points in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Kidney Int. 2013;83:278–284. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Niewczas MA, Gohda T, Skupien J, Smiles AM, Walker WH, Rosetti F, Cullere X, Eckfeldt JH, Doria A, Mayadas TN, Warram JH, Krolewski AS. Circulating TNF receptors 1 and 2 predict ESRD in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:507–515. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011060627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gohda T, Niewczas MA, Ficociello LH, Walker WH, Skupien J, Rosetti F, Cullere X, Johnson AC, Crabtree G, Smiles AM, Mayadas TN, Warram JH, Krolewski AS. Circulating TNF receptors 1 and 2 predict stage 3 CKD in type 1 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:516–524. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011060628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]