Abstract

The development of high-speed analytical techniques such as next-generation sequencing and microarrays allows high-throughput analysis of biological information at a low cost. These techniques contribute to medical and bioscience advancements and provide new avenues for scientific research. Here, we outline a variety of new innovative techniques and discuss their use in omics research (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, proteomics, and interactomics). We also discuss the possible applications of these methods, including an interactome sequencing technology that we developed, in future medical and life science research.

1. Introduction

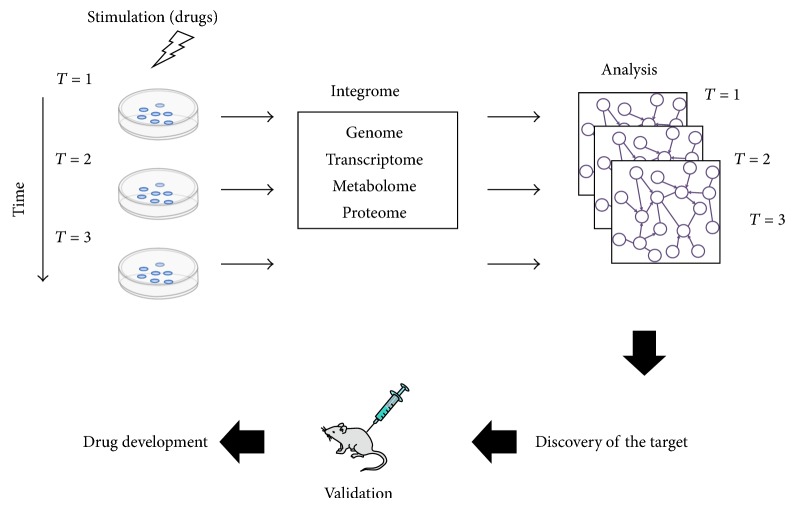

More than a decade has passed since the human genome sequence was decoded. Subsequent advancements in and integration of personal genome analysis, post-genome functional analysis, and multiomics analyses have facilitated the development of personalized medicine, which is emerging as the optimal therapeutic direction for the future of medical science (Figure 1). The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) and its use in clinical practice will enable the adaptation of multiomics data to personal medical care. However, the costs of these methods and the amount of data generated using multiomics approaches have emerged as challenges that must be tackled. Interactome analysis is considered to be a crucial integrator of multiomics analysis. Currently, the “integrome” is being investigated to determine how the large amounts of data generated using multiomics approaches can be integrated most advantageously. In this review, we discuss these innovative new approaches used in genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, and proteomics. We also present an overview of the new insights into complex biological systems that are provided by the use of these technologies.

Figure 1.

The dynamics of pharmacological response mechanisms can be examined by analyzing integrated multiomics data. First, the time series of the multiomics data are integrated. Second, an efficient module-detecting algorithm is applied to the composite maps. The maps can then be used for comparing cancer cells and normal cells and for assessing the effects of medicines. Lastly, the identified targets can be validated in animal experiments designed for the purpose of subsequent drug development.

2. Genomics

NGS has contributed substantially to recent advances in omics research. In NGS, a technology used in genome sequencing, sequences containing millions of DNA fragments are read by performing numerous reactions in parallel [1]. The use of this technology has dramatically reduced the time and cost required for sequencing and has facilitated analysis of the human genome, epigenome, and transcriptome. Several NGS platforms have been released by various companies, and a few representative platforms are HiSeq and MiSeq (Illumina), 454 GS FLX (Roche), and PacBio (Pacific Biotechnology) (Table 1). In these platforms, distinct methods of template preparation and signal detection are used [2, 3].

Table 1.

Comparison of representative NGS platforms.

| Platform | Company | Detection | Run time | Read length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 454 GS FLX Titanium XL+ | Roche | Pyrosequencing | 23 hours | 700 |

| 454 GS Junior System | Roche | Pyrosequencing | 10 hours | 400 |

| HiSeq 2000/2500 | Illumina | Fluorescence | 12 days | 2 × 100 |

| MiSeq | Illumina | Fluorescence | 65 hours | 2 × 300 |

| Ion torrent | Life Technologies | Proton release | 3 hours | 35–400 |

| Ion Proton | Life Technologies | Proton release | 4 hours | 125 |

| Abi/solid | Life Technologies | Fluorescence | 10 days | 50 |

| PacBio RSII | Pacific Bioscience | Fluorescence | 2 days | −8500 |

NGS can be used for performing genomic and epigenomic analyses (Table 2). In genomic analysis, somatic mutations are detected using whole-genome sequencing or whole-exome sequencing. In whole-genome sequencing, somatic mutations (e.g., single nucleotide polymorphisms or insertion-deletion mutations) are identified by sequencing the entire genome, and this approach has been used to identify several somatic mutations in various cancers [4, 5].

Table 2.

Types and features of next-generation sequencing technologies.

| Type of analysis | Type of sequencing | Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Genome | Whole-genome sequencing | Used to detect somatic mutations by sequencing the whole genome |

| Whole-exome sequencing | Used to detect somatic mutations by sequencing the whole exon region | |

|

| ||

| Epigenome | Bisulfite sequencing | Used for analyzing methylation by sequencing genome exhaustively |

| ChIP-seq | Used to detect the targets of transcription factors or analysis of histone modifications | |

| DNase-seq | Used for analysis of chromatin architecture | |

| FAIRE-seq | ||

| Hi-C | ||

| ChIA-PET | Used to characterize chromatin interactions that are mediated by nuclear protein of interest | |

|

| ||

| Transcriptome | RNA sequencing | Used for analysis of gene expression or detection of fusion genes and splice variants |

|

| ||

| Interactome | IVV-HiTSeq | Used to detect reliable protein (domain) interactome without cloning including interactions of protein-protein/DNA/RNA/metabolic compounds/small molecules/drugs and so forth, suitable for high-throughput application, acquisition of high-reliability datasets, and analysis of cytotoxic proteins |

| Y2H-seq | Used to detect interacting proteins or protein-domain pairs, but mating and the following diploid culture become the rate-limiting steps when applied in high-throughput technologies | |

ChIP-seq: chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing; FAIRE-seq: formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements sequencing; ChIA-PET: chromatin interaction analysis by means of paired-end tag sequencing; IVV-HiTSeq: IVV high-throughput sequencing; Y2H-seq: yeast two-hybrid interaction screening approach involving short-read second-generation sequencing.

The use of whole-exome sequencing, which is employed for analyzing exon regions, has identified numerous mutations that occur in disease, such as BRAF mutations in papillary craniopharyngiomas [6] and somatic mutations of BCOR in myeloid leukemia [7]. Furthermore, this approach has been used for analyzing tumor borders and for detecting the BRAF mutation characteristic to borderline tumors. By this approach, 15 novel somatic mutations were detected in serous borderline tumors of the ovary [8]. Thus, genomic analysis performed using NGS provides extensive information about somatic mutations. In addition to genomic analysis, epigenetic analyses are performed using NGS. DNA methylation is involved in transcriptional regulation and it potently affects disease progression. One of the methods used for analyzing the methylation status of DNA (in particular, the methylation of cytosine residues) is bisulfite sequencing. This application was developed based on exploiting the feature that bisulfate treatment converts all residues except methylated cytosine into uracil. The use of bisulfite sequencing has yielded key information regarding the epigenome in the context of cancer and other diseases [9, 10]. Thus, analyzing DNA methylation is critical in the field of epigenetics.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) can be used for detecting protein binding to target DNA sequences and histone modifications. The method enables analyses of transcription factor binding to gene promoters and epigenetic modifications (e.g., histone modifications) [11, 12]. Moreover, the chromosome conformation capture (3C) method [13, 14] is used for detecting protein-DNA interaction-mediated spatial chromosome proximity, which is involved in transcriptional regulation and coexpression. Studies in which genome-wide 3C methods were employed together with NGS, such as chromosome conformation capture-on-chip (4C) [15], Hi-C [16], and tethered conformation capture (TCC) [17], have shown that the spatial architecture of interphase chromosomes is closely related to DNA-replication timing, activity of genes, and cell differentiation (reviewed in [18]). Chromatin interaction analysis by means of paired-end tag sequencing (ChIA-PET), which is regarded as a combination of ChIP-seq and 3C, has been used for detecting the chromatin organization that is caused by a specific transcription factor [19, 20]. Recently, ChIA-PET studies performed on RNA polymerase II, which is present in the transcription preinitiation complex, comprehensively revealed active promoters, the transcription factors involved in their activation, and the spatial relationships among them [21, 22]. Thus, DNA sequencing has facilitated advances in both genomic and epigenomic analyses.

3. Transcriptomics

Similar to the manner in which DNA sequencing analysis has contributed to genomics and epigenomics, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has contributed to transcriptome analysis (Table 2). RNA-seq is an RNA-sequencing technology that is mainly used for sequencing mRNAs or long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs). The mRNA in cells is analyzed in order to quantify gene expression or to detect fusion genes and splice variants in various cancers [23–25]. RNA-seq has also been used for studying gene expression patterns unique to certain cancers, including lung and renal carcinomas, and this has enabled researchers to identify novel biomarkers for specific types of cancer [24, 26, 27]. Microarrays are also used for analyzing gene expression, but RNA-seq differs from that approach in the following manner: using RNA-seq, absolute quantification of expression is performed, whereas, using microarrays, relative expression is calculated. Moreover, an additional advantage of RNA-seq is that it can be used for detecting unknown transcription products, whereas microarrays cannot be used for this purpose. Certain transcription products have been detected using RNA-seq, and, in a few recent studies, RNA-seq was used for analyzing lncRNAs.

Thus, advances in this field of study have been made possible by the use of NGS-mediated analysis of the transcriptome. NGS has also already been successfully used for detecting mutations in cancer genes, and future research is expected to identify more of these mutations, which might be of therapeutic value.

4. Metabolomics

Metabolomics differs from nucleic acid-based-omics methods. Using metabolomics approaches, metabolites contained in a sample can be detected and their concentrations can be determined. This strategy is based on the premise that differences in metabolites reflect differences in biological processes.

Shifts in metabolite composition and changes at the genetic level enable the screening of potential biomarker candidates or therapeutic targets. For instance, high levels of reactive carbonyl compounds and low levels of vitamin B6 are observed in the plasma of patients with certain subtypes of schizophrenia [28], suggesting that the use of the carbonyl-scavenger pyridoxamine might provide therapeutic benefits for these patients [29]. The relationship between cancer and changes in metabolites is widely recognized. For example, the Warburg effect describes the process whereby cancer cells preferably use the glycolytic pathway to produce ATP, even when sufficient oxygen is present [30]. The recent accumulation of knowledge based on metabolomics could enable advances in early cancer detection. For example, metabolomics studies have revealed that the profile of free amino acids in plasma is altered in the presence of cancer [31]. This information might lead to the development of novel metabolomics-based screening for early detection of a malignancy.

Most methods used in metabolomics involve separation and detection processes (Table 3) [32–35]. Researchers have typically relied on chromatography—gas chromatography (GC) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)—and capillary electrophoresis (CE) for separation, whereas they have used nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) or mass spectrometry (MS) for detection [36, 37]. However, the drawbacks of these approaches have led researchers to combine two or more methods (e.g., liquid chromatography and MS (LC-MS/MS) plus NMR) in metabolomics studies [38].

Table 3.

Comparison of major metabolomics methods.

| Method | Benefit | Drawback |

|---|---|---|

| NMR | (1) Results obtained in a single experiment (2) Fast (3) Available for studying various nuclei (4) Consistent with liquid and solid matrices (5) Quantitative (6) Sample can be recovered after analysis |

(1) Requires highly skilled technicians and statisticians (2) Limited sensitivity (1–10 µmol/L) (3) Coresonant metabolites can be challenging to quantify |

|

| ||

| GC-MS | (1) High accuracy and repeatability of results (2) Small amounts of samples are required (3) High discrimination between molecules exhibiting very similar structures (4) High sensitivity (1 pmol/L) |

(1) Sample preparation (including derivatization) can be time-consuming (2) Not all compounds are suitable for gas chromatography |

|

| ||

| LC-MS | (1) Wide application (2) High sensitivity (1 pmol/L) |

(1) Requires extensive sample preparation, including derivatization (2) Long analytical time (20–60 min per sample) (3) Limited to volatile compounds (4) Suffers from ion suppression |

|

| ||

| CE-MS | (1) Suitable for polar molecules (2) Large separation capacity (3) High sensitivity (1 pmol/L) |

(1) Low repeatability |

Metabolomics is divided roughly into two categories based on the experimental methods used: nontargeted and target-defined metabolomics. Nontargeted metabolome analysis is extremely attractive because this method can be used to identify an unknown metabolite and to concurrently determine its relative amount; thus, this method is suitable for nonbiased metabolite fingerprinting and diagnostic-marker exploration. However, nontargeted analysis performed using a single routine method remains challenging. This is because the metabolome includes compounds that differ considerably in molecular weight, electric charge, and concentration. Furthermore, although reference mass-spectrum databases [39–43] have grown rapidly and NMR microassays [44] have been improved, the molecular structures of unknown compounds present in trace amounts cannot be readily determined. Conversely, in several cases, identifying and determining the concentrations of all metabolites is not necessary. For example, only approximately 3,000 types of compounds are currently recognized in relation to human disease [45]. Because MS/MS can be used for detecting hundreds of compounds present in a single extract [46], targeted analysis is more suitable than nontargeted analysis for certain types of application, such as when the research is focused on a specific metabolic pathway. Therefore, future analyses are likely to involve the use of wide-targeted approaches in which several targeted experiments are combined when target compounds are available.

5. Proteomics

Comprehensive proteome analysis includes expression proteomics and interaction proteomics. Expression proteomics reveals protein expression patterns in cells, and this approach has been typically used for analyzing the expression status of various proteins by using two-dimensional electrophoresis (differential display) and MS [47]. However, proteins typically do not act alone and must interact with other proteins in order to perform functions. Therefore, interactions between proteins should be analyzed comprehensively. Comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions (PPIs) is critical in the fields of proteomics, functional genomics, and systems biology. PPIs are detected using methods that can be divided into in vivo and in vitro techniques (Table 4). Among these methods, in vitro virus (IVV) and yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) tests allow the application of interactome sequencing (Table 2).

Table 4.

Comparison of comprehensive protein-protein interaction analysis methods.

| Method | Selection condition of PPIs | Library size | Cell cloning required | Next-generation sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y2H | In vivo | 106 | Yes | Applicable but limited |

| TAP-MS | In vitro | Living body sample | Yes | Inapplicable |

| Protein microarray | In vitro | Living body sample | No | Inapplicable |

| Shotgun proteomics | In vitro | Living body sample | No | Inapplicable |

| IVV | In vitro | 1012 | No | Applicable and effective |

See also Table 1.

Y2H: yeast two-hybrid; TAP-MS: tandem affinity purification-mass spectrometry; IVV: in vitro virus.

5.1. In Vivo Methods

The Y2H assay is an in vivo approach used to detect PPIs [48]. The assay requires two protein domains: a DNA-binding domain and an activation domain that is involved in the activation of DNA transcription. These domains are necessary for the transcription of reporter genes [49, 50]. The Y2H assay allows PPIs to be directly recognized, although in the analysis performed using this method false-positive interactions can appear. The data generated using in vivo techniques contain extremely high levels of false positives and false negatives. For example, although the exact rate of false-positive results in Y2H experiments is unknown, early estimates were that these are as high as 70% [51]. False-positive rates in AP experiments could be as high as 77% [52].

5.2. In Vitro Methods

Traditionally, PPIs in vitro have been detected using the tandem affinity purification (TAP) method [53, 54]. In this method, a bait containing tags allows protein complexes to be purified. The purified complexes are identified using a separate approach, such as MS [53, 54]. TAP tags have been developed which can be used for studying complex in vivo PPIs without the requirement of prior knowledge [53]. The TAP tagging technology has been used for analyzing the interactome in yeast [55]. The method is based on the attachment of two tags to a protein of interest, which is followed by a two-step purification process [56]. Proteins complexed with the target protein can then be identified using MS [57] and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The main advantage of TAP-MS is that it can be used for analyzing PPIs comprehensively in the form of protein complexes (which the target protein would be a part of in vivo) through the identification of a wide variety of protein complexes [56].

The protein microarray method is currently being established as a powerful tool for detecting proteins, observing their expression levels, and probing their interactions and functions. A protein microarray is a glass plate on which single proteins are bound at distinct positions according to a defined procedure [58]. Protein microarrays have been developed in order to allow an operator to process multiple samples in parallel by using an automated process; this enables efficient and sensitive high-throughput protein analysis.

Another method that allows high-throughput identification of PPIs in original extracts is shotgun proteomics [59]. In this technique, proteins are digested with a protease immediately after extraction and then the resulting peptides are separated using LC; subsequently, the amino acid sequences of the peptides are determined using MS/MS.

The development of the techniques described thus far has facilitated the high-throughput identification of protein interactions. However, the number of proteins that cannot be detected or identified even using these methods, such as the proteins that are expressed at extremely low levels or are highly insoluble, is considerably greater than the number of proteins that can be detected or identified (e.g., abundant, soluble proteins). Therefore, new technologies are required for performing highly efficient high-throughput analysis of numerous proteins.

The IVV-high-throughput sequencing (IVV-HiTSeq, Figure 2) method [60], which is a combination of NGS and IVV, has been developed with the aim of overcoming the aforementioned challenges. In the IVV method, protein interactions are selected under cell-free conditions [61–65], and the subsequent sequencing by means of NGS is not limited by cloning steps performed using any specific type of cell. Thus, using the IVV-HiTSeq method, large amounts of accurate protein-interaction data can potentially be generated. The cell-free aspect of the experimental procedure is one of the main advantages: it allows highly efficient production of interaction data. When IVV and HiTSeq are combined, no host cells are required for the purpose of DNA cloning, a step that previously limited the efficiency of screening and the number of interactions that could be examined. Furthermore, the IVV method can be used to select proteins from a cDNA library consisting of 1012 molecules, which is beyond the capacity of conventional high-throughput protein-selection methods [66, 67]. The coverage of the interactome is expected to increase in line with the further increases expected in the NGS throughput. Importantly, this completely cell-free procedure will also allow cytotoxic proteins to be analyzed, which will make interactome analysis more comprehensive than it currently is. With respect to the accuracy of IVV-HiTSeq data, the use of library-specific barcoded primers and in silico analysis reduces the number of false-positive interactions contained in the initial raw data [60]. IVV-HiTSeq was compared with conventional IVV performed using Sanger sequencing for the same prey library and bait. Whereas 640 sequences (87%) determined using Sanger sequencing were also obtained using IVV-HiTSeq, most of the sequences (99.7%) obtained using IVV-HiTSeq were new and were not detected using Sanger sequencing. Moreover, 88% of the real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays performed and followed up with the use of IVV-HiTSeq, which included in silico analyses, were positive. IVV-HiTSeq can potentially be applied to several cell-free display technologies, such as mRNA display, DNA display, and ribosome display. Moreover, the IVV test can be applied not only to in vitro selection of PPIs but also to the detection of protein-DNA, protein-RNA, and protein-chemical compound interactions [68]; this suggests that IVV-HiTSeq could become a universal tool for exploring protein sequences and interaction networks [47].

Figure 2.

The type of primer used contains a barcoded region (indicated in grey, green, blue, yellow, and red), with four selection-round-specific bases. The reads generated using high-throughput sequencing are sorted according to their barcoded parts and mapped to known genomic sequences. Read frequencies of each genomic position are calculated for each selection round and used for determining the enriched regions. Using barcoded primers can reduce the risk of cross-contamination between libraries. Moreover, in a PPI analysis, increasing the sequencing depth can help detect contamination between samples. In the experiment shown, the Roche 454 Sequencer was used. Statistical significance was calculated by comparing the read frequencies with the frequencies of the initial library and the negative control.

6. Discussion

To further our understanding of living cells, we must collect data by using multiomics analysis. Multiomics includes gene-, transcription-, metabolite-, and protein-specific information. By contrast, the interactome includes network data that are obtained based on direct interactions between molecules. Therefore, an integrated approach, which includes both interactome and multiomics data, is required for comparing the identities of individual cells. This approach is referred to as “integrome” analysis [69]. The integrome is a network map of the interactome together with a list of multiomics data that allows analyses of differences between cancer cells and normal cells [70], the effects of treatments, and key factors such as biomarkers. Because PPIs lie at the core of biomolecular networks, an IVV system designed for detecting PPIs has been developed in an attempt to work toward personal genomics [71], and, using this system, noteworthy results of interactome analysis have been obtained. An advantage of IVV is the large library size (up to 1012) that can be analyzed. This large size of the library increases the probability of selecting extremely rare sequences, and it also enhances the diversity of the selected sequences.

The use of NGS will allow the potential of IVV to be maximized. The latest Roche 454 Sequencer can sequence approximately 106 reads, at a rate of approximately 1000 bp per run. This capacity is sufficient for covering both of the linked variable regions. Although 106 reads are not adequate for covering the entire selected IVV library, this advance in NGS might make it possible to obtain unique, high-affinity binders.

Improvements in NGS might also facilitate the development of additional applications, and particularly notable is the speed with which NGS technology is being improved. When we have the capability to sequence the entire selected IVV library, we should be able to select low-affinity ligands that are commonly lost in a typical selection of repetitious rounds. IVV libraries will be subjected to high-throughput sequencing performed using NGS in order to generate interactome information, which will facilitate the archiving of the interactome map of a whole-cell library at a low cost. The use of IVV systems could make key contributions to our understanding of the interactome networks in cells and thus help in the development of pharmaceutical agents for treating currently intractable diseases [71].

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Mardis E. R. The impact of next-generation sequencing technology on genetics. Trends in Genetics. 2008;24(3):133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metzker M. L. Sequencing technologies the next generation. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2010;11(1):31–46. doi: 10.1038/nrg2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buermans H. P., den Dunnen J. T. Next generation sequencing technology: advances and applications. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta—Molecular Basis of Disease. 2014;1842(10):1932–1941. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cazier J.-B., Rao S. R., McLean C. M., et al. Whole-genome sequencing of bladder cancers reveals somatic CDKN1A mutations and clinicopathological associations with mutation burden. Nature Communications. 2014;5, article 3756 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao Y., Yang J., Chen Z., et al. Identification of somatic alterations in stage I lung adenocarcinomas by next-generation sequencing. Genes Chromosomes and Cancer. 2014;53(4):289–298. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brastianos P. K., Taylor-Weiner A., Manley P. E., et al. Exome sequencing identifies BRAF mutations in papillary craniopharyngiomas. Nature Genetics. 2014;46(2):161–165. doi: 10.1038/ng.2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grossmann V., Tiacci E., Holmes A. B., et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies somatic mutations of BCOR in acute myeloid leukemia with normal karyotype. Blood. 2011;118(23):6153–6163. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-365320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd J., Luo B., Peri S., et al. Whole exome sequence analysis of serous borderline tumors of the ovary. Gynecologic Oncology. 2013;130(3):560–564. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adey A., Shendure J. Ultra-low-input, tagmentation-based whole-genome bisulfite sequencing. Genome Research. 2012;22(6):1139–1143. doi: 10.1101/gr.136242.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kabekkodu S. P., Bhat S., Radhakrishnan R., et al. DNA promoter methylation-dependent transcription of the double C2-like domain β (DOC2B) gene regulates tumor growth in human cervical cancer. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2014;289(15):10637–10649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.491506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahony S., Edwards M. D., Mazzoni E. O., et al. An integrated model of multiple-condition ChIP-Seq data reveals predeterminants of Cdx2 binding. PLoS Computational Biology. 2014;10(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003501.e1003501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pick H., Kilic S., Fierz B. Engineering chromatin states: chemical and synthetic biology approaches to investigate histone modification function. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2014;1839(8):644–656. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dekker J., Rippe K., Dekker M., Kleckner N. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science. 2002;295(5558):1306–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.1067799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tolhuis B., Palstra R. J., Splinter E., Grosveld F., de Laat W. Looping and interaction between hypersensitive sites in the active β-globin locus. Molecular Cell. 2002;10(6):1453–1465. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00781-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Splinter E., de Wit E., Nora E. P., et al. The inactive X chromosome adopts a unique three-dimensional conformation that is dependent on Xist RNA. Genes & Development. 2011;25(13):1371–1383. doi: 10.1101/gad.633311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lieberman-Aiden E., van Berkum N. L., Williams L., et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science. 2009;326(5950):289–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1181369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalhor R., Tjong H., Jayathilaka N., Alber F., Chen L. Genome architectures revealed by tethered chromosome conformation capture and population-based modeling. Nature Biotechnology. 2012;30(1):90–98. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bickmore W. A., Van Steensel B. Genome architecture: domain organization of interphase chromosomes. Cell. 2013;152(6):1270–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fullwood M. J., Liu M. H., Pan Y. F., et al. An oestrogen-receptor-α-bound human chromatin interactome. Nature. 2009;462(7269):58–64. doi: 10.1038/nature08497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang J., Poh H. M., Peh S. Q., et al. ChIA-PET analysis of transcriptional chromatin interactions. Methods. 2012;58(3):289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y., Wong C.-H., Birnbaum R. Y., et al. Chromatin connectivity maps reveal dynamic promoter-enhancer long-range associations. Nature. 2013;504(7479):306–310. doi: 10.1038/nature12716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kieffer-Kwon K. R., Tang Z., Mathe E., et al. Interactome maps of mouse gene regulatory domains reveal basic principles of transcriptional regulation. Cell. 2013;155(7):1507–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maher C. A., Kumar-Sinha C., Cao X., et al. Transcriptome sequencing to detect gene fusions in cancer. Nature. 2009;458(7234):97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature07638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Z.-H., Zheng R., Gao Y., Zhang Q., Zhang H. Abnormal gene expression and gene fusion in lung adenocarcinoma with high-throughput RNA sequencing. Cancer Gene Therapy. 2014;21(2):74–82. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2013.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eswaran J., Horvath A., Godbole S., et al. RNA sequencing of cancer reveals novel splicing alterations. Scientific Reports. 2013;3, article 1689 doi: 10.1038/srep01689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han S. S., Kim W. J., Hong Y., et al. RNA sequencing identifies novel markers of non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2014;84(3):229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiong Z., Yu H., Ding Y., et al. RNA sequencing reveals upregulation of RUNX1-RUNX1T1 gene signatures in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. BioMed Research International. 2014;2014:8. doi: 10.1155/2014/450621.450621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arai M., Yuzawa H., Nohara I., et al. Enhanced carbonyl stress in a subpopulation of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):589–597. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyashita M., Arai M., Kobori A., et al. Clinical features of schizophrenia with enhanced carbonyl stress. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2014;40(5):1040–1046. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123(3191):309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyagi Y., Higashiyama M., Gochi A., et al. Plasma free amino acid profiling of five types of cancer patients and its application for early detection. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024143.e24143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mussap M., Antonucci R., Noto A., Fanos V. The role of metabolomics in neonatal and pediatric laboratory medicine. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2013;426:127–138. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffin J. L., Shockcor J. P. Metabolic profiles of cancer cells. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2004;4(7):551–561. doi: 10.1038/nrc1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Putri S. P., Yamamoto S., Tsugawa H., Fukusaki E. Current metabolomics: technological advances. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering. 2013;116(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belyakov P. A., Kadentsev V. I., Chizhov A. O., Kolotyrkina N. G., Shashkov A. S., Ananikov V. P. Mechanistic insight into organic and catalytic reactions by joint studies using mass spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy. Mendeleev Communications. 2010;20(3):125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.mencom.2010.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Armitage E. G., Barbas C. Metabolomics in cancer biomarker discovery: current trends and future perspectives. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 2014;87:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2013.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Putri S. P., Nakayama Y., Matsuda F., et al. Current metabolomics: practical applications. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering. 2013;115(6):579–589. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eugster P. J., Glauser G., Wolfender J.-L. Strategies in biomarker discovery. peak annotation by MS and targeted LC-MS micro-fractionation for de novo structure identification by micro-NMR. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2013;1055:267–289. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-577-4-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hummel J., Strehmel N., Selbig J., Walther D., Kopka J. Decision tree supported substructure prediction of metabolites from GC-MS profiles. Metabolomics. 2010;6(2):322–333. doi: 10.1007/s11306-010-0198-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith C. A., O'Maille G., Want E. J., et al. METLIN: a metabolite mass spectral database. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 2005;27(6):747–751. doi: 10.1097/01.ftd.0000179845.53213.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cui Q., Lewis I. A., Hegeman A. D., et al. Metabolite identification via the Madison Metabolomics Consortium Database. Nature Biotechnology. 2008;26(2):162–164. doi: 10.1038/nbt0208-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wishart D. S., Tzur D., Knox C., et al. HMDB: the human metabolome database. Nucleic Acids Research. 2007;35(1):D521–D526. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horai H., Arita M., Kanaya S., et al. MassBank: a public repository for sharing mass spectral data for life sciences. Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2010;45(7):703–714. doi: 10.1002/jms.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zalesskiy S. S., Danieli E., Blümich B., Ananikov V. P. Miniaturization of NMR Systems: desktop spectrometers, microcoil spectroscopy, and “NMR on a chip” for chemistry, biochemistry, and industry. Chemical Reviews. 2014;114(11):5641–5694. doi: 10.1021/cr400063g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wishart D. S., Jewison T., Guo A. C., et al. HMDB 3.0—the human metabolome database in 2013. Nucleic Acids Research. 2013;41(1):D801–D807. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abu-Reidah I. M., Arráez-Román D., Segura-Carretero A., Fernández-Gutiérrez A. Profiling of phenolic and other polar constituents from hydro-methanolic extract of watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) by means of accurate-mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS) Food Research International. 2013;51(1):354–362. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2012.12.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wittke S., Kaiser T., Mischak H. Differential polypeptide display: the search for the elusive target. Journal of Chromatography B. 2004;803(1):17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2003.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uetz P., Glot L., Cagney G., et al. A comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Nature. 2000;403(6770):623–627. doi: 10.1038/35001009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ito T., Chiba T., Ozawa R., Yoshida M., Hattori M., Sakaki Y. A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(8):4569–4574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061034498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.James P., Halladay J., Craig E. A. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics. 1996;144(4):1425–1436. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deane C. M., Salwiński Ł., Xenarios I., Eisenberg D. Protein interactions: two methods for assessment of the reliability of high throughput observations. Molecular and Cellular Proteomics. 2002;1(5):349–356. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M100037-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Edwards A. M., Kus B., Jansen R., Greenbaum D., Greenblatt J., Gerstein M. Bridging structural biology and genomics: Assessing protein interaction data with known complexes. Trends in Genetics. 2002;18(10):529–536. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)02763-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rigaut G., Shevchenko A., Rutz B., Wilm M., Mann M., Seraphin B. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nature Biotechnology. 1999;17(10):1030–1032. doi: 10.1038/13732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Puig O., Caspary F., Rigaut G., et al. The tandem affinity purification (TAP) method: a general procedure of protein complex purification. Methods. 2001;24(3):218–229. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gavin A. C., Bösche M., Krause R., et al. Functional organization of the yeast proteome by systematic analysis of protein complexes. Nature. 2002;415(6868):141–147. doi: 10.1038/415141a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pitre S., Alamgir M., Green J. R., Dumontier M., Dehne F., Golshani A. Computational methods for predicting protein-protein interactions. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology. 2008;110:247–267. doi: 10.1007/10_2007_089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rohila J. S., Chen M., Cerny R., Fromm M. E. Improved tandem affinity purification tag and methods for isolation of protein heterocomplexes from plants. Plant Journal. 2004;38(1):172–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.MacBeath G., Schreiber S. L. Printing proteins as microarrays for high-throughput function determination. Science. 2000;289(5485):1760–1763. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5485.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moresco J. J., Carvalho P. C., Yates J. R. Identifying components of protein complexes in C. elegans using co-immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry. Journal of Proteomics. 2010;73(11):2198–2204. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fujimori S., Hirai N., Ohashi H., et al. Next-generation sequencing coupled with a cell-free display technology for high-throughput production of reliable interactome data. Scientific Reports. 2012;2, article 691 doi: 10.1038/srep00691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miyamoto-Sato E., Fujimori S., Ishizaka M., et al. A comprehensive resource of interacting protein regions for refining human transcription factor networks. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009289.e9289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miyamoto-Sato E., Ishizaka M., Horisawa K., et al. Cell-free cotranslation and selection using in vitro virus for high-throughput analysis of protein-protein interactions and complexes. Genome Research. 2005;15(5):710–717. doi: 10.1101/gr.3510505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miyamoto-Sato E., Yanagawa H. Toward functional analysis of protein interactome using “in vitro virus”: in silico analyses of Fos/Jun interactors. Journal of Drug Targeting. 2006;14(7):505–511. doi: 10.1080/10611860600845017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miyamoto-Sato E. Next-generation sequencing coupled with a cell-free display technology for reliable interactome of translational factors. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2014;1164:23–32. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0805-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ohashi H., Fujimori S., Hirai N., Yanagawa H., Miyamoto-Sato E. Analysis of transcription factor networks using IVV method. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2014;1164:15–22. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0805-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roberts R. W. Totally in vitro protein selection using mRNA-protein fusions and ribosome display. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 1999;3(3):268–273. doi: 10.1016/S1367-5931(99)80042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang H., Liu R. Advantages of mRNA display selections over other selection techniques for investigation of protein-protein interactions. Expert Review of Proteomics. 2011;8(3):335–346. doi: 10.1586/epr.11.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Takahashi T. T., Austin R. J., Roberts R. W. mRNA display: ligand discovery, interaction analysis and beyond. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2003;28(3):159–165. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Baker M. Big biology: the 'omes puzzle. Nature. 2013;494(7438):416–419. doi: 10.1038/494416a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dimitrakopoulou K., Dimitrakopoulos G. N., Sgarbas K. N., Bezerianos A. Tamoxifen integromics and personalized medicine: dynamic modular transformations underpinning response to tamoxifen in breast cancer treatment. OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology. 2014;18(1):15–33. doi: 10.1089/omi.2013.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ohashi H., Miyamoto-Sato E. Towards personalized medicine mediated by in vitro virus-based interactome approaches. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2014;15(4):6717–6724. doi: 10.3390/ijms15046717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]