Abstract

Objective

To investigate the association between age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and mortality in older persons.

Design

Population-based prospective cohort study.

Participants

Participants aged 67–96 years old (43.1% male) enrolled between 2002 and 2006 in the Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study (AGES).

Methods

Retinal photography of the macula was digitally acquired and evaluated for the presence of AMD lesions using the Wisconsin Age-Related Maculopathy grading scheme. Mortality was assessed prospectively through 2013 with cause of death available through 2009. The association between AMD and death, due to any cause and specifically, cardiovascular disease (CVD), was examined using Cox proportional hazards regression with age as the time scale, adjusted for significant risk factors and comorbid conditions. To address a violation in the proportional hazards assumption, analyses were stratified into two groups based on the mean age at death (83 years).

Main Outcome Measures

Mortality from all-causes and cardiovascular disease.

Results

Among 4910 participants, after a median follow-up period of 8.6 years, 1742 died (35.5%), of whom 614 (35.2%) had signs of AMD at baseline. CVD was the cause of death for 357 people who died before the end of 2009, of whom 144 (40%) had AMD (101 early and 43 late). After considering covariates, including comorbid conditions, having early AMD at any age, or late AMD in individuals under age 83 (n=4179), were not associated with all-cause or CVD mortality. In individuals aged 83 years and older (n=731), late AMD was significantly associated with increased risk of all-cause [hazard ratio (HR): 1.76 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.20–2.57)] and CVD-related mortality [HR: 2.37 (95% CI: 1.41–3.98)]. In addition to having AMD, older individuals who died were more likely to be male, have low body mass index, impaired cognition, and microalbuminuria.

Conclusions

Competing risk factors and concomitant conditions are important in determining mortality risk due to AMD. Individuals with early AMD are not more likely to die than peers of comparable age. Late AMD becomes a predictor of mortality by the mid-octogenarian years.

Keywords: AGES-Reykjavik Study, age-related macular degeneration, mortality, cardiovascular mortality

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a complex disease whose etiology remains poorly understood, although risk factors for AMD and cardiovascular disease, a leading cause of death, are similar and may connote shared underlying pathobiology.1–8 There have been several attempts to discern whether persons with AMD are at increased risk of death, particularly due to cardiovascular causes, but results are inconsistent.9–19 In the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS), persons with advanced stages of maculopathy had significantly reduced survival, independent of demographic and lifestyle characteristics and comorbid conditions.19 The population-based Blue Mountains Eye Study also found increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in persons aged 49–74 years with AMD.12–13 In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, persons with late AMD had higher 10 year mortality rates but the numbers of people with late AMD were too few to allow for covariate adjustment.10 The Copenhagen City Eye Study also reported, after adjusting for risk indicators, reduced survival among women with AMD but not among men.9 Yet, two other studies, the Rotterdam Study and the Medical Research Council Trial of Assessment and Management of Older People in the Community, reported that associations between AMD and mortality were the result of risks attributable to cardiovascular disease and/or diabetes and after adjustment for these factors, persons with AMD were not at higher risk of death.16,18 There was no association between AMD and mortality in the Beijing Eye Study although the study population was middle-aged and experienced few deaths.11

Iceland experiences high life expectancy which may explain, in part, why the AMD prevalence in the Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik (AGES) cohort is higher than has been reported in other cohorts of comparable age.20–21 Since the AGES study collected data on a wide array of conditions common in old age, it provides an opportunity to examine, in the context of concomitant conditions including cardiovascular disease, the association between AMD and mortality.

METHODS

Study Population

The AGES study22 is a population-based prospective c ohort study of 5764 persons aged 67 years and older at recruitment between 2002 and 2006, selected randomly from surviving participants (n=11,549) of the Reykjavik Study initiated by the Icelandic Heart Association (IHA) in 1967. Of the participants examined as part of the AGES study, 4994 (86.6%) completed the eye examination with retinal imaging. Of these, 84 participants were excluded due to insufficient data to determine AMD status, leaving 4910 individuals for the current analysis.

The AGES Study was approved by the Icelandic National Bioethics Committee (VSN: 00-063), the Icelandic Data Protection Authority, Iceland, and by the Institutional Review Board for the National Institute of Aging, National Institutes of Health, USA. All participants provided written informed consent.

Retinal Examination

Retinal fundus images were acquired following a standardized protocol, described in detail previously.20, 23–24 In brief, after pharmacologic dilation of the pupils, a Canon CR6 nonmydriatic camera (US Canon Inc, Lake Success, NY) photographed both eyes taking two 45-degree images of each retina, one centered on the optic disc and the other centered on the fovea.

Retinal images were evaluated by masked graders at the Ocular Epidemiology Reading Center at the University of Wisconsin. Images were assessed using a semiquantitative approach with EyeQ Lite image processing software (Digital Healthcare Inc., Cambridge, UK) and a modified Wisconsin Age-Related Maculopathy grading scheme.24–25 Detailed information on AMD lesions defined in AGES, as well as the quality control procedures and inter- and intra-observer reliability for AMD assessment, have been published elsewhere.20 Briefly, soft drusen were defined by size and appearance; pigmentary abnormalities were characterized by increased retinal pigment or RPE depigmentation. Early AMD was defined as: 1) the presence of any soft drusen and pigmentary abnormalities; or 2) the presence of large soft drusen (≥ 125µm in diameter) with a large drusen area (> 500µm in diameter); or 3) large indistinct soft drusen (≥ 125µm) in the absence of late AMD. Late AMD was defined by the presence of geographic atrophy (GA) or exudative AMD (RPE detachment, subretinal hemorrhage or visible subretinal new vessel, or subretinal fibrous scar or laser treatment scar for AMD). If one eye was not gradable, data from the fellow eye was used; otherwise, the AMD grade of the more severely affected eye was used.

Mortality Outcome

Ascertainment of mortality events was completed by the Icelandic Heart Association with the permission of the Icelandic Data Protection Authority. Participant identifiers from the AGES study were linked to the complete adjudicated registry of deaths in the Icelandic National Roster maintained by Statistics Iceland (http://www.statice.is/Statistics/Population/Births-and-deaths). All deaths occurring between the date of the eye examination and September 27, 2013 were utilized in analyses of death from any cause. Cause-of-death attributable to cardiovascular disease was determined by the Icelandic Heart Association using the International Classification of Disease (ICD) (versions 9–10) and guidelines from the Systemic Coronary Risk Evaluation project.26 Deaths with the following ICD codes for cause-of-death were attributed to cardiovascular disease: 401 through 414, 426 through 443, and 798.1 and 798.2, with the exception of the following codes for definitely non-atherosclerotic causes of death: 426.7, 429.0, 430.0, 432.1, 437.3, 437.4, and 437.5. Cause-of-death was available only for deaths recorded through December 31, 2009 when funding for cause-of-death classification in Iceland ceased.

Covariates

During detailed in-person interviews and an extensive clinical examination, numerous characteristics and health indicators were assessed. Education was dichotomized as completed secondary school or less than secondary school. Smoking status was classified as never smoker, former smoker, or current smoker. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (meters) squared. Hypertension was characterized by a self-reported history of hypertension, use of antihypertensive drugs, or blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mm Hg. Diabetes mellitus was determined by a self-reported history of diabetes, use of glucose-modifying medications, or fasting blood glucose of ≥ 7.0 mm ol/L. Total cholesterol (mmol/L), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (mmol/L), glucose (mmol/L), albumin (g/L), creatinine (mmol/L), and HbA1c (%) were measured on-site at the IHA laboratory using standard protocols. HbA1c levels ≥ 6.5% were considered elevated. Microalbuminuria was defined as a urine albumin: creatinine ratio (UACR) ≥ 30 mg/g. An estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 ml/min/1.73m2 was considered evidence of chronic kidney disease (CKD). A score of six or greater on the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale was necessary to be categorized as having depressive symptomology. Self-reported health status was measured using a Likert scale (e.g. excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor) and later dichotomized as poor or good based upon the participant’s response in interview. The AGES protocol included a three-step procedure to identify cases of dementia, which were adjudicated in a consensus conference adhering to international guidelines. For this analysis, the data were dichotomized into impaired (dementia/mild cognitive impairment) and not impaired (not demented).27 Walking disability was defined by self-report of difficulty walking or use of walking aids. Record of a clinical cardiovascular event came from documented hospital reports of a myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass surgery, or angioplasty and was classified as yes or no. Data on the Y402H polymorphism (rs1061170) in the Complement Factor H (CFH) gene were available from approximately half of cohort, chosen at random, who participated in a candidate gene SNP array project genotyped by Illuminia Genotyping Services, San Diego, California, U.S.A, using its high throughput BeadArray Microarray Technology. Vision impairment and severe vision impairment were defined as a presenting visual acuity in the better eye of 20/50 or worse and 20/200 or worse, respectively. Eyes that were blind, per participant or clinician report, were not excluded from this analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis of covariance and logistic regression, adjusting for age and sex, were used to compare baseline characteristics by AMD status. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) first for mortality due to any cause, and specifically CVD, to determine characteristics significantly associated with these endpoints. Model entry and selection c riteria for covariates utilized the minimum Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) corresponding to an implied significance level of P < 0.11–0.19. Thereafter, Cox proportional hazards regression models included these covariates along with AMD status. Since risk of AMD and risk of mortality are strongly associated with increasing age, age was used as the time scale in the Cox proportional hazards regression, allowing the models to compare risk for people of comparable age (instead of length of time under follow-up). The proportionality assumptions of the HRs associated with each variable in the Cox proportional hazards models, incorporating AMD, were inspected graphically and tested by generating time-dependent covariates for each variable from the interactions of the variable with the logarithm of the follow-up time to determine the statistical significance of the interaction terms in each regression analysis (of early and late AMD with all-cause and CVD-related mortality). Only the time-dependent covariate for age was found to be significant in AMD models, and therefore, analyses were stratified into two age groups (ages 67 to 82 years and ages 83+ years) based on the mean age-at-death. Coincidentally, 83 years was the median age-at-death and also the mean age, at baseline, of persons with late AMD. This age-stratified analysis allowed us to account better for health conditions that could influence mortality risk in different phases of older life. Participants with late AMD were excluded from all analyses of early AMD. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported, by AMD status, for risk factors significantly associated with mortality. Analyses were two-sided at the 5% significance level. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Compared to study participants, individuals without retinal data were older (76.4±5.5, range 67–96 years, versus 80.5±6.7, range 67–98 years, P<0.01), less likely to be male, less educated, less likely to consume alcohol, and more likely to be a current smoker, self-report poor health, be depressed, be cognitively impaired, have diabetes, have a walking disability or a history of falls, take more medications, and have higher HDL cholesterol, glucose, and HbA1c levels (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics for Study Population

| Characteristic at Baseline Exam | Participants with AMD Data (n=4910) |

Participants without AMD Data (n=854) |

p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age in years | 76.4 (5.5) | 80.5 (6.7) | < 0.01 |

| Male | 43.1% (2116) | 37.7% (322) | < 0.01 |

| Education Level, Completed Secondary or More | 76.9% (3746) | 69.8% (321) | 0.02 |

| Marital Status, Married or Living Together | 60.2% (2934) | 51.7% (238) | 0.12 |

| Physical Activity, Moderate or Greater Frequency | 32.5% (1474) | 27.1% (118) | 0.11 |

| Former Smoker | 44.9% (2204) | 32.2% (214) | < 0.01 |

| Current Smoker | 12.1% (593) | 13.5% (90) | < 0.01 |

| Current Alcohol Consumption | 65.2% (3180) | 54.4% (360) | < 0.01 |

| Hypertension | 80.9% (3970) | 82.7% (667) | 0.31 |

| Mean DBP, mmHG | 74.0 (9.7) | 72.5 (10.6) | 0.46 |

| Mean SBP, mmHG | 142.4 (20.2) | 142.6 (24.1) | 0.06 |

| Mean BMI | 27.0 (4.4) | 27.0 (4.8) | 0.07 |

| Self-Reported Health Status, Poor | 5.5% (269) | 14.2% (112) | < 0.01 |

| Depressive Symptomology | 7.0% (325) | 15.2% (112) | < 0.01 |

| Cognitive Status, Impaired | 14.3% (693) | 38.2% (250) | < 0.01 |

| Walking Disability | 17.6% (861) | 40.7% (270) | < 0.01 |

| Self-Reported History of Falls | 17.8% (873) | 23.3% (184) | 0.03 |

| Cod Liver Oil Use | 57.7% (2835) | 44.7% (382) | < 0.01 |

| Mean Number of Medications | 4.1 (2.9) | 5.3 (3.9) | < 0.01 |

| Aspirin Use | 34.6% (1697) | 37.4% (319) | 0.44 |

| Mean High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.6 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.5) | < 0.01 |

| Mean Total Cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.6 (1.2) | 5.7 (1.2) | 0.81 |

| Diabetes | 11.7% (572) | 20.7% (177) | < 0.01 |

| HbA1c ≥ 6.5% | 5.1% (233) | 7.5% (57) | < 0.01 |

| Microalbuminuria | 8.7% (422) | 9.8% (46) | 0.76 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 30.7% (1505) | 37.5% (319) | 0.84 |

| History of Angina, by Self-Report | 14.5% (696) | 12.5% (73) | 0.16 |

| History of Cancer, by Self-Report | 15.2% (744) | 17.1% (135) | 0.61 |

| History of Cardiovascular Disease, by Self-Report | 23.5% (1153) | 26.8% (212) | 0.21 |

| Record of Clinical Cardiovascular Event | 15.5% (751) | 15.2% (128) | 0.83 |

Data are presented as % (N) or mean (standard deviation);

Adjusted for age and sex.

Among the 4910 participants, AMD was present at the baseline examination in 1341 (27.3%); of whom, 1064 (21.7%) had early AMD and 277 (5.6%) had late AMD (Table 2). During the ten-year follow-up period (median follow-up 8.6 years, range 3–10 years), 1742 (35.5%) individuals died. The mean time-to-death from baseline exam was 4.8 years and the mean age-at-death was 83.9 years. Deaths occurring through 2009 numbered 846, of which 357 (42.2%) were attributed to CVD. The mean time-to-death did not differ significantly by AMD status; however, those who died without AMD were significantly younger at death than individuals with early or late AMD (82.8±5.7 versus 85.4±5.5 and 87.7±4.8 years, respectively, P<0.01 for both).

Table 2.

Mortality Characteristics, Overall and by Age-Related Macular Degeneration

| AMD Status |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Overall N=(4910) |

No AMD (N=3569) |

Early AMD (N=1064) |

Late AMD (N=277) |

| Mean Age at Baseline, in years (SD)a | 79.4 (5.6) | 78.3 (5.5) | 80.8 (5.4)** | 83.5 (4.5)** |

| Mean Age at Death from All Causes, in years (SD)a | 83.9 (5.8) | 82.8 (5.7) | 85.4 (5.5)** | 87.7 (4.8)** |

| Mean Age at Death from CVD-Related Causes, in years (SD)a | 84.3 (6.0) | 82.8 (6.0) | 86.0 (5.5)** | 87.5 (4.3)** |

| Mortality Rate from All Causes % (N) | 35.5% (1742) | 31.6% (1128) | 43.1% (458)** | 56.3% (156)** |

| Mortality Rate from All Causes among Participants Aged 67–82 years % (N)b | 29.4% (1227) | 27.6% (880) | 34.2% (284)** | 39.6% (63)** |

| Mortality Rate from All Causes among Participants Aged 83+ years % (N)c | 70.5% (515) | 65.3% (248) | 74.7% (174)** | 78.8% (93)** |

| Mortality Rate from CVD-Related Causes % (N) | 7.3% (357) | 6.0% (213) | 9.5% (101)** | 15.5% (43)** |

| Mortality Rate from CVD-Related Causes among Participants Aged 67–82 years % (N)b | 4.9% (206) | 4.6% (148) | 5.5% (46) | 7.6% (12) |

| Mortality Rate from CVD-Related Causes among Participants Aged 83+ years % (N)c | 20.7% (151) | 17.1% (65) | 23.6% (55)* | 26.3% (31)* |

| Mean Time-to-Death from All Causes from Baseline Exam, in years (SD)a | 4.8 (1.7) | 4.8 (1.7) | 4.8 (1.7) | 4.5 (1.9) |

| Mean Time-to-Death from CVD-Related Causes from Baseline Exam, in years (SD)a | 3.6 (1.8) | 3.7 (1.7) | 3.5 (1.9) | 3.2 (1.8) |

All-cause mortality was assessed through 27 September 2013; CVD-related mortality was assessed through 31 December 2009, by which time there were 846 deaths from any cause.

T-tests and chi-square tests were used to compare means and rates, respectively. Comparisons were between each AMD group and the no AMD group and were unadjusted;

p<0.05;

p<0.01

Among non-survivors.

Mortality rates for participants aged 67–82 years were calculated from an overall sample of N=4179 and samples of N=3189, N=831, and N=159 for no AMD, early AMD, and late AMD, respectively.

Mortality rates for participants aged 83+ years were calculated from an overall sample of N=731 and samples N=380, N=233, and N=118 for no AMD, early AMD, and late AMD, respectively.

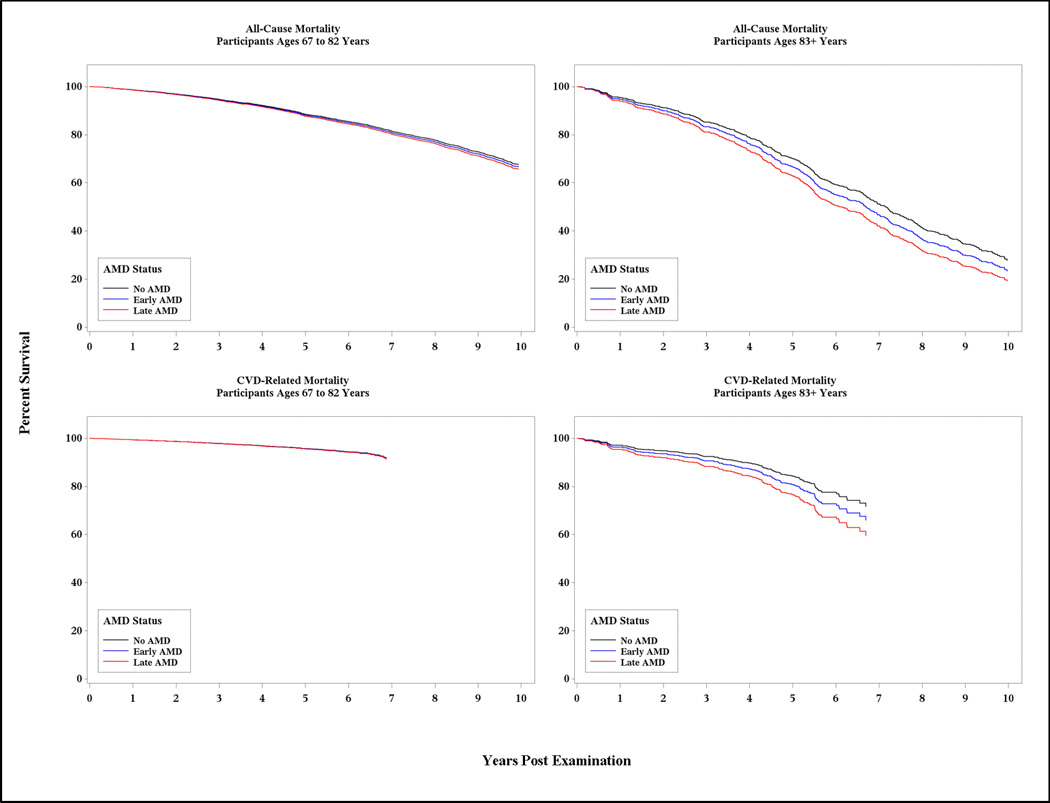

Persons with late AMD, but not early AMD, were significantly more likely to die compared to their peers of comparable age (supplemental Table A); however, upon closer scrutiny of the proportional hazards assumptions, it became clear that this association was driven by data from people at the older age of the distribution and, for statistical reasons, age stratification of the cohort was warranted. This is depicted graphically in Figure 1, which illustrates, over the ten year follow-up period, mortality by AMD status (none, early, or late), stratified by age group and, within each panel, adjusted for age and sex. As expected, mortality risk increased with increasing age and was most pronounced for the oldest members of the cohort.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Plot for All-Cause and CVD-Related Mortality Rates by AMD Status, Stratified by Age Group and Adjusted for Age and Sex.

All-cause mortality was assessed through 27 September 2013; CVD-related mortality was assessed through 31 December 2009.

Participants with AMD who died were significantly older at baseline (78.0±5.5, range 67–93 years, versus 81.3±5.3, range 67–96 years, P<0.01). Characteristics for those who died are provided by AMD status, stratified by age group, in Table 3. Among those who died in the younger group (ages 67–82 years), current smoking was significantly associated with AMD status after adjusting for age and sex, whereas in the older group of individuals who died (ages 83+ years), higher HDL-cholesterol was associated with both early and late AMD. Regardless of age group, persons who died with late AMD were significantly more likely to be visually impaired in their better eye than persons without AMD.

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristics by Age-Related Macular Degeneration in those who Died

| Participants Ages 67 to 82 years (N=1227) |

Participants Ages 83+ years (N=515) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic at Baseline Exam | No AMD (n=880) |

Early AMD (n=284) |

Late AMD (n=63) |

No AMD (n=248) |

Early AMD (n=174) |

Late AMD (n=93) |

| Mean Age in years | 76.0 (4.2) | 77.3 (3.8)** | 79.1 (3.1)** | 85.3 (2.4) | 86.0 (2.9)* | 86.0 (2.8)* |

| Male | 50.7% (446) | 53.2% (151) | 41.3% (26) | 52.4% (130) | 47.1% (82) | 54.8% (51) |

| Education Level, Completed Secondary or More | 76.2% (664) | 74.5% (210) | 60.7% (37) | 74.9% (179) | 70.2% (118) | 69.2% (63) |

| Marital Status, Married or Living Together | 61.5% (536) | 59.2% (167) | 56.5% (35) | 39.3% (94) | 40.5% (68) | 49.5% (45)* |

| Former Smoker | 47.0% (413) | 49.1% (139) | 40.3% (25) | 47.2% (117) | 41.0% (71) | 45.2% (42) |

| Current Smoker | 16.4% (144) | 19.8% (56)* | 27.4% (17)** | 5.7% (14) | 6.4% (11) | 10.8% (10) |

| Hypertension | 82.7% (727) | 80.3% (228) | 87.3% (55) | 91.1% (226) | 87.9% (153) | 86.0% (80) |

| Mean BMI | 26.9 (4.7) | 26.9 (4.8) | 26.9 (4.7) | 25.8 (4.0) | 25.6 (4.2) | 24.9 (3.7) |

| Self-Reported Health Status, Poor | 9.9% (87) | 6.0% (17) | 12.7% (8) | 8.9% (22) | 12.6% (22) | 3.2% (3) |

| Depressive Symptomology | 10.6% (86) | 8.0% (21) | 13.3% (8) | 9.0% (21) | 8.0% (13) | 8.2% (7) |

| Cognitive Status, Impaired | 20.0% (173) | 18.5% (52) | 29.5% (18) | 36.6% (89) | 35.3% (60) | 45.2% (38) |

| Walking Disability | 22.2% (195) | 25.1% (71) | 30.2% (19) | 38.3% (95) | 44.5% (77) | 45.2% (42) |

| Cod Liver Oil Use | 54.4% (479) | 54.9% (156) | 49.2% (31) | 58.5% (145) | 58.1% (101) | 57.0% (53) |

| Mean Number of Medication | 4.7 (3.1) | 4.6 (3.1) | 5.1 (2.7) | 5.1 (3.3) | 5.1 (3.3) | 4.6 (2.8) |

| Aspirin-Use | 39.6% (348) | 40.5% (115) | 39.7% (25) | 33.5% (83) | 42.0% (73) | 44.1% (41) |

| Mean High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.5 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.4) | 1.7 (0.5)** | 1.7 (0.4)** |

| Mean Total Cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.5 (1.1) | 5.4 (1.2) | 5.6 (1.1) | 5.5 (1.2) | 5.7 (1.3) | 5.5 (1.0) |

| Diabetesa | 15.0% (132) | 20.4% (58)* | 12.7% (8) | 12.1% (30) | 10.9% (19) | 14.0% (13) |

| Microalbuminuria | 12.2% (105) | 13.2% (37) | 12.9% (8) | 21.3% (50) | 16.5% (28) | 15.4% (14) |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 35.5% (312) | 39.8% (113) | 33.3% (21) | 51.2% (127) | 45.4% (79) | 37.6% (35)* |

| History of Angina, by Self-Report | 19.6% (168) | 19.5% (54) | 18.6% (11) | 17.1% (40) | 12.0% (20) | 18.9% (17) |

| History of Cancer, by Self-Report | 20.8% (182) | 18.8% (53) | 14.3% (9) | 18.9% (46) | 19.7% (34) | 19.6% (18) |

| History of Cardiovascular Disease, by Self-Report | 29.9% (263) | 34.4% (97) | 36.5% (23) | 27.2% (67) | 28.7% (50) | 30.1% (28) |

| Record of Clinical Cardiovascular Event | 21.5% (188) | 23.2% (66) | 19.4% (12) | 16.2% (40) | 16.8% (29) | 16.3% (15) |

| Vision Impairment (Better Eye)b | 12.3% (108) | 21.7% (61)** | 57.4% (35)** | 25.5% (63) | 29.5% (51) | 58.1% (54)** |

| Severe Vision Impairment (Better Eye)b | 0.7% (6) | 0.7% (2) | 19.7% (12)** | 1.2% (3) | 2.3% (4) | 28.0% (26)** |

| CFH Genotype RS1061170c | ||||||

| Allele TT | 40.0% (166) | 26.1% (36)** | 6.9% (2)** | 43.9% (47) | 32.4% (22) | 25.0% (7) |

| Allele CT | 49.4% (205) | 47.1% (65) | 62.1% (18) | 44.9% (48) | 52.9% (36) | 60.7% (17) |

| Allele CC | 10.6% (44) | 26.8% (37) | 31.0% (9) | 11.2% (12) | 14.7% (10) | 14.3% (4) |

All-cause mortality was assessed through 27 September 2013. Data are presented as % (N) or mean (standard deviation). Comparisons are for each AMD group with the No AMD group, adjusted for age and sex;

p-value < 0.05,

p-value < 0.01.

Diabetes mellitus was defined as the self-reported history of diabetes, use of glucose-modifying medications, or fasting blood glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L.

Vision impairment (VI) was defined as a presenting visual acuity of 20/50 or worse in the better eye; severe VI was defined as a presenting visual acuity of 20/200 or worse in the better eye.

Available in approximately 50% of the sample.

Among participants aged 67 to 82 years old who died, persons with late AMD and, to a lesser extent, persons with early AMD were significantly less likely to have the CFH TT genotype compared to persons without AMD. Interestingly, the overall rate of mortality among those with a CC genotype (35.3%) was lower compared to those with a TT genotype (37.0%), although among those who died, persons with AMD, after adjusting for age and sex, were significantly less likely to carry two T alleles compared to those without AMD (10.9% versus 18.9%). Further adjustment for smoking status did not attenuate this finding (data not shown).

There were 4179 participants aged 67 to 82 years at their baseline examination; of whom, 1227 (29.4%) died, and of these, 284 had early AMD and 63 had late AMD. After considering age, established mortality risk factors and comorbid conditions, AMD status was not associated with all-cause or CVD-related mortality when compared to individuals without signs of AMD. In this age group, factors predictive of mortality included smoking, low BMI, increased number of medications used, cognitive impairment, walking disability, self-reported history of cancer or angina, record of clinical cardiovascular event, microalbuminuria, and chronic kidney disease (Table 4).

Table 4.

Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Models of All-Cause and CVD-Related Mortality by Age-Related Macular Degeneration

| Participants Ages 67 to 82 years (N=4179) |

Participants Ages 83+ years (N=731) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | All-Cause Mortality (HR and 95% CI) |

CVD-Related Mortality (HR and 95% CI) |

All-Cause Mortality (HR and 95% CI) |

CVD-Related Mortality (HR and 95% CI) |

| Early AMD, present vs absent | 1.01 (0.81, 1.27) | 0.91 (0.63, 1.31) | 1.21 (0.90, 1.62) | 1.42 (0.94, 2.12) |

| Sex, female vs male | 0.72 (0.58, 0.90)** | 0.77 (0.53, 1.12) | 0.64 (0.46, 0.89)** | 0.70 (0.44, 1.11) |

| Smoking Status, former vs never | 1.55 (1.24, 1.94)** | 1.16 (0.81, 1.67) | 1.01 (0.79, 1.29) | 0.82 (0.53, 1.26) |

| Smoking Status, current vs never | 2.26 (1.71, 2.98)** | 1.99 (1.26, 3.15)** | 1.40 (0.86, 2.26) | 1.66 (0.68, 4.04) |

| BMI, per kg/m2 | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99)* | 0.99 (0.95, 1.03) | 0.92 (0.88, 0.95)** | 0.91 (0.85, 0.96)** |

| Number of Medications, per unit | 1.07 (1.04, 1.11)** | 1.05 (0.99, 1.11) | 1.05 (0.99, 1.09) | 1.11 (1.03, 1.20)** |

| Self-Reported Health Status, poor vs good | 1.14 (0.89, 1.42) | 1.32 (0.77, 2.27) | 1.50 (0.95, 2.36) | 1.27 (0.67, 2.43) |

| Depressive Symptomology, yes vs no | 1.17 (0.94, 1.46) | 1.41 (0.86, 2.30) | 0.65 (0.40, 1.05) | 1.01 (0.52, 2.00) |

| Cognitive Status, impaired vs unimpaired | 2.49 (1.99, 3.12)** | 2.28 (1.60, 3.27)** | 1.53 (1.13, 2.07)** | 1.12 (0.72, 1.73) |

| Diabetes, yes vs no | 1.27 (0.96, 1.52) | 1.24 (0.81, 1.90) | 1.27 (0.89, 1.82) | 1.07 (0.57, 2.01) |

| Walking Disability, yes vs no | 2.04 (1.62, 2.57)** | 1.81 (1.24, 2.62)** | 1.01 (0.79, 1.29) | 1.02 (0.65, 1.59) |

| Total Plasma Cholesterol, per mmol/L | 0.95 (0.90, 1.01) | 1.02 (0.87, 1.19) | 0.91 (0.82, 1.01) | 1.03 (0.85, 1.25) |

| High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol, per mmol/L | 1.06 (0.90, 1.24) | 0.83 (0.54, 1.27) | 1.00 (0.75, 1.34) | 0.52 (0.30, 1.01) |

| History of Angina, yes vs no | Not Included in Model | 1.56 (1.02, 2.38)* | Not Included in Model | 1.21 (0.69, 2.11) |

| History of Cancer, yes vs no | 2.05 (1.66, 2.54)** | Not Included in Model | 1.11 (0.84, 1.47) | Not Included in Model |

| History of Cardiovascular Disease, yes vs no | 1.09 (0.94, 1.26) | Not Included in Model | 0.86 (0.65, 1.14) | Not Included in Model |

| Record of Clinical Cardiovascular Event, yes vs no | Not Included in Model | 1.59 (1.02, 2.47)* | Not Included in Model | 0.95 (0.53, 1.70) |

| Microalbuminuria, yes vs no | 1.48 (1.12, 1.95)** | 1.52 (0.98, 2.36) | 1.92 (1.36, 2.71)** | 1.97 (1.23, 3.15)** |

| Chronic Kidney Disease, yes vs no | 1.33 (1.08, 1.62)** | 1.35 (0.98, 1.88) | 1.16 (0.92, 1.47) | 1.17 (0.77, 1.78) |

| Late AMD, present vs absent | 1.37 (0.95, 1.98) | 1.07 (0.55, 2.06) | 1.76 (1.20, 2.57)** | 2.37 (1.41, 3.98)** |

| Sex, female vs male | 0.73 (0.59, 0.91)** | 0.73 (0.51, 1.06) | 0.64 (0.46, 0.88)** | 0.64 (0.40, 1.01) |

| Smoking Status, former vs never | 1.58 (1.27, 1.97)** | 1.11 (0.78, 1.58) | 1.08 (0.86, 1.35) | 0.78 (0.50, 1.22) |

| Smoking Status, current vs never | 2.29 (1.75, 2.99)** | 1.89 (1.21, 2.95)** | 1.42 (0.94, 2.15) | 1.92 (0.94, 3.92) |

| BMI, per kg/m2 | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99)** | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.92 (0.89, 0.96)* | 0.92 (0.87, 0.98)* |

| Number of Medications, per unit | 1.08 (1.04, 1.12)** | 1.06 (1.01, 1.12)* | 1.06 (1.01, 1.12)* | 1.11 (1.03, 1.20)** |

| Self-Reported Health Status, poor vs good | 1.31 (0.99, 1.67) | 1.23 (0.73, 2.10) | 1.33 (0.87, 2.05) | 1.15 (0.53, 2.49) |

| Depressive Symptomology, yes vs no | 1.15 (0.93, 1.42) | 1.28 (0.79, 2.06) | 0.66 (0.42, 1.03) | 0.63 (0.27, 1.45) |

| Cognitive Status, impaired vs unimpaired | 2.31 (1.85, 2.87)** | 2.35 (1.67, 3.32)** | 1.56 (1.15, 2.13)** | 1.35 (0.87, 2.09) |

| Diabetes, yes vs no | 1.24 (0.94, 1.48) | 1.20 (0.79, 1.82) | 1.22 (0.88, 1.68) | 1.18 (0.65, 2.13) |

| Walking Disability, yes vs no | 1.97 (1.58, 2.45)** | 1.74 (1.22, 2.50)** | 0.98 (0.78, 1.23) | 1.16 (0.74, 1.80) |

| Total Plasma Cholesterol, per mmol/L | 0.96 (0.90, 1.02) | 1.04 (0.90, 1.21) | 0.90 (0.82, 1.00) | 1.10 (0.91, 1.33) |

| High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol, per mmol/L | 1.05 (0.90, 1.23) | 0.83 (0.55, 1.26) | 1.07 (0.82, 1.40) | 0.53 (0.30, 1.05) |

| History of Angina, yes vs no | Not Included in Model | 1.67 (1.11, 2.51)* | Not Included in Model | 1.07 (0.61, 1.90) |

| History of Cancer, yes vs no | 1.96 (1.60, 2.42)** | Not Included in Model | 1.08 (0.83, 1.41) | Not Included in Model |

| History of Cardiovascular Disease, yes vs no | 1.12 (0.97, 1.30) | Not Included in Model | 0.87 (0.67, 1.11) | Not Included in Model |

| Record of Clinical Cardiovascular Event, yes vs no | Not Included in Model | 0.51 (0.98, 2.33) | Not Included in Model | 1.07 (0.59, 1.94) |

| Microalbuminuria, yes vs no | 1.53 (1.17, 1.99)** | 1.53 (1.01, 2.34)* | 1.84 (1.30, 2.60)** | 2.08 (1.28, 3.37)** |

| Chronic Kidney Disease, yes vs no | 1.29 (1.06, 1.57)* | 1.36 (0.99, 1.87) | 1.20 (0.97, 1.50) | 1.37 (0.89, 2.11) |

HR = Hazard Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval,

p-value < 0.05,

p-value < 0.01;

“Not Included in Model” indicates a variable that did not meet the AIC criteria as outlined in the methods section.

Among the 731 individuals aged 83 years and older at baseline, 70.5% died during follow-up period. In this older age group, persons with early AMD were also not at increased risk of death after considering age and concomitant conditions; however, persons with late AMD were at greater risk of all-cause [HR: 1.76 (95% CI: 1.20–2.57)] and CVD-related mortality [HR: 2.37 (95% CI: 1.41–3.98)] compared to individuals of comparable age without AMD. More specifically, pure geographic atrophy, present in 7.8% (n=52) of individuals, was associated with increased all-cause and CVD-related mortality after controlling for potential confounders [HRs: 1.80 (95% CI: 1.03–3.16) and 3.23 (95% CI: 1.63–6.38), respectively], and exudative AMD, present in 9.0% (n=66) of individuals, was significantly associated with death attributable to any cause [HR: 1.65 (95% CI: 1.04- 2.62)] but not cardiovascular disease (supplemental Table B). Other significant independent predictors of increased risk of all-cause or CVD-related mortality in participants aged 83 years and older (besides late AMD) include male sex, low BMI, increased number of medications used, cognitive impairment, and microalbuminuria (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Individuals in their mid-80’s and older with geographic atrophy and, to a lesser extent, exudative AMD are at increased risk of mortality from all causes and CVD causes even after considering microalbuminuria and cognitive impairment, other conditions influencing risk of mortality in this older age group. Younger individuals with late AMD are not at higher risk of dying compared to their same age peers after considering other conditions or diseases, such as smoking, cardiovascular disease, and cancer, which elevate risk of mortality in early old age. Persons with early AMD at any age are not at increased risk of dying relative to others of comparable age without AMD.

Results from the current study are supported by some, but not all, of the previous findings.9–19 The Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS)19 reported that the probability of death from any cause and from cardiovascular causes occurring over a median of 6.5 years of follow-up was higher, even after covariate adjustment, among participants with advanced AMD compared to those without AMD or with drusen only. Similarly, the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study found no evidence for an association between early AMD and all-cause mortality but did observe a higher 10 year mortality rate among individuals with late AMD although the small number of late AMD cases precluded full adjustment for important covariates.10 Women with AMD, but not men, experienced lower rates of survival over a 14 year follow-up period in the Copenhagen City Eye Study where the overall mortality rate in the cohort was 61%, the highest of any study examining this issue.9 Interestingly, women with AMD were significantly more likely to die from respiratory causes, including pulmonary disease secondary to cardiac insufficiency, compared to women without AMD. The Blue Mountains Eye Study12 found that, only among individuals younger than 75 years at the baseline examination, signs of early and late AMD were predictive of increased all-cause mortality, but only late AMD predicted increased vascular mortality, after adjustment for potentially confounding variables. The Blue Mountain study re-evaluated the associations between AMD and death due to cardiovascular causes after excluding individuals with a history of stroke, angina, or myocardial infarction, and reported persons under age 75 years with early AMD were significantly more likely to die from cardiovascular causes than persons of similar age who did not exhibit signs of early AMD.13 There was no such associations found in persons ages 75 years and older or in persons of either age group with late AMD, although the relative risks were elevated but not significant, likely due to the small numbers of individuals with late AMD. The results of the current study support and extend these findings reporting associations between AMD and mortality, enhancing our understanding of the impact of AMD on an older population and other concomitant risk factors associated with mortality in older individuals.

Unlike our study, however, the Beijing Eye Study did not find any association between AMD and mortality in its younger cohort of participants (mean age 56 years) followed over 5 years.11 A UK study of participants ages 75 years and older followed over 6.1 years did observe significant associations between AMD and all-cause mortality, as well as with cardiovascular mortality, both of which persisted after adjustment for age and sex but attenuated to become non-significant after covariate adjustment.18 AMD was also not associated with survival, or only crudely associated (when analyses adjusted for age and sex only), in the Beaver Dam Eye Study15 and the Rotterdam Study.16 The low prevalence of late AMD (< 2%) and the younger ages of participants (e.g. aged 43–84 years with mean age of 64 years and aged 55 years or older, respectively) in these two studies may explain the inconsistencies with the current study. At the 20 year follow-up of the Beaver Dam cohort, however, late AMD was associated with increased mortality risk in persons aged 85 years and older, supporting the notion that increasing age impacts on mortality risk attributable to AMD.14

In the current study, there were numerous concomitant factors significantly increasing risk of death among persons aged 67 to 82 years old at baseline, specifically smoking, angina, previous clinical cardiovascular events, cancer, cognitive decline, walking disability, and kidney dysfunction. By the mid-octogenarian years, however, fewer factors account for death in our analysis. In addition to having late AMD, octogenarians who died were more likely to be cognitively impaired and have microalbuminuria. As has been concluded by others,10 the factors increasing mortality risk in older adults appear to be highly age-dependent. As such, it is possible that putative risk factors may reflect a differential distribution of underlying health profiles based on distinct exposures experienced b y different birth cohorts over their lifetime.

We were unable to assess the role of CFH genotype in the Cox proportional hazard regression models since genotype data were available from fewer than half of the participants; however, we looked at this in the subgroup with this data since the topic of selective survival has been raised.29 Adjusting only for age, sex and smoking status, persons with AMD compared to persons without AMD were more likely to have the CC or CT genotype, relative to a TT genotype (data not shown), as has been reported previously.14 Unlike a previous report from Finland30, we found the mortality rate was higher for participants with the TT genotype, which make explain, in part, the higher rate of AMD in the older Icelandic cohort.

Consistent with a previous analysis on this cohort, visual impairment was not a significant, independent predictor of mortality28 and was not retained as a covariate in the regression models. However, AMD is highly associated with visual impairment, an important indicator of quality of life. In the deceased, 57.8% of those with late AMD had vision impairment at the baseline exam compared to 24.7% of those with early AMD and 15.2% of those without AMD. Among the 156 people with late AMD who subsequently died, 38 (24.7%) had severe visual impairment in their last years of life.

Strengths of the current study include its large elderly cohort with high participation rate, standardized objective methods for assessing AMD, availability of a wide array of health indicators, and a complete, adjudicated registry of deaths assessed without knowledge of AMD status. Additionally, the greater prevalence of AMD, specifically at advanced-stages, in this cohort increases our ability to assess the relationship between late AMD and mortality independent of other adverse health conditions that increase the risk of death. The study was limited by the availability of cause-of-death only through December 31, 2009 when funding for such classification was withdrawn. Additionally, this analysis considered health characteristics assessed at a single point in time. Thus, while mortality was assessed prospectively, decreased survival may result from undocumented comorbid conditions arising rapidly in the median eight year interval between baseline examination and death. Finally, the possibility of a selection bias, between those community-dwelling older persons who completed the retinal examination and those who did not, could have influenced our results, although it is likely that the results we report are conservative given that non-participants were older and had poorer health.

In summary, our findings suggest that by the mid-octogenarian years, persons with late AMD are at increased risk of all-cause and CVD-related mortality. The reasons for the association of late AMD, an ocular condition, with decreased survival are not known and may reflect some, as yet undetermined, systemic pathology indicative of physiologic aging. Although early AMD is not associated with mortality at any age, halting AMD before it progresses to advanced stages may reduce the risk of severe visual impairment and improve quality of life for older person with AMD. Finally, older people with AMD have other coexisting conditions and concomitant health indicators, particularly kidney dysfunction and cognitive impairment, which should be considered in the design and evaluation of therapies for AMD and in addressing issues of patient management, including treatment compliance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support

Supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging (ZIAAG007380) and the National Eye Institute (ZIAEY000401), National Institutes of Health (contract N-01-AG-1-2100), Bethesda, MD, USA; the Icelandic Heart Association, Kopavogur, Iceland; the Icelandic Parliament, Reykavik Iceland; the University of Iceland Research Fund, Reykjavik Iceland; and the Helga Jonsdottir and Sigurlidi Kristjansson Research Fund, Reykjavik, Iceland. The funders had no role in data collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data, preparation, writing and approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no proprietary or commercial interest in any materials discussed in this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Seddon JM, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Hankinson SE. A prospective study of cigarette smoking and age-related macular degeneration in women. JAMA. 1996;276:1141–1146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seddon JM, Cote J, Davis N, Rosner B. Progression of age-related macular degeneration: association with body mass index, wrist circumference, and waist-hip ratio. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:785–792. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.6.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eye Disease Case-Control Study Group. Risk factors for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:1701–1708. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080240041025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vingerling JR, Dielemans I, Bots ML, et al. Age-related macular degeneration is associated with atherosclerosis. The Rotterdam Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:404–409. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyman L, Schachat AP, He Q, et al. Hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;18:351–358. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith W, Mitchell P, Leeder SR, Wang JJ. Plasma fibrinogen levels, other cardiovascular risk factors, and age-related maculopathy: the Blue Mountain Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:583–587. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein R, Klein BE, Frank T. The association of cardiovascular disease and its risk factors to age-related maculopathy: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:406–414. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31634-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarty CA, Mukesh BN, Fu CL, et al. Risk factors for age-related maculopathy: the Visual Impairment Project. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1455–1462. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.10.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buch H, Vinding T, la Cour M, Jensen GB, Prause JU, Nielsen NV. Age-related maculopathy: a risk indicator for poorer survival in women: the Copenhagen City Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong TY, Tikellis G, Sun C, Klein R, Couper DJ, Sharrett AR. Age-related macular degeneration and risk of coronary heart disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu L, Wang YX, Wang J, Jonas JJ. Mortality and ocular diseases: the Beijing Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:732–738. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cugati S, Cumming RG, Smith W, Burlutsky G, Mitchell P, Wang JJ. Visual impairment, age-related macular degeneration, cataract, and long-term mortality. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:917–924. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.7.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan JSL, Wang JJ, Liew G, Rochtchina E, Mitchell P. Age-related macular degeneration and mortality from cardiovascular disease or stroke. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:509–512. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.131706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gangnon RE, Lee KE, Klein BEK, Iyengar SK, Sivakumaran TA, Klein R. Effect of the Y402H variant in the complement factor H gene on the incidence and progression of age-related macular degeneration. Results from multistate models applied to the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:1169–1176. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knudtson M, Klein BEK, Klein R. Age-related eye disease, visual impairment, and survival. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:243–249. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borger PH, van Leeuwen R, Hulsman CA, et al. Is there a direct association between age-related eye diseases and mortality? The Rotterdam Study. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1292–1296. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00450-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE. Age-related eye disease and survival: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:333–339. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100030089026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thiagarajan M, Evans JR, Smeeth L, et al. Cause-specific visual impairment and mortality: results from a population-based study of older people in the United Kingdom. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1397–1403. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.10.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clemons TE, Kurinij N, Sperduto RD AREDS Research Group. Associations of mortality with ocular disorders and an intervention of high-dose antioxidants and zinc in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study: AREDS Report No. 13. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:716–726. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.5.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonasson F, Arnarsson A, Eiríksdottir G, Harris TB, Launer LJ, Meuer SM, Klein BE, Klein R, Gudnason V, Cotch MF. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in old persons: Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility Reykjavik Study. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:825–830. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonasson F, Fisher DE, Eiriksdottir G, Sigurdsson S, Klein R, Launer LJ, Harris T, Gudnason V, Cotch MF. Five-year incidence, progression and risk factors for age-related macular degeneration: the Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility Study. Ophthalmology. 2014 Apr 24;121:1766–1772. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.03.013. pii: S0161-6420(14)00237-1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.03.013. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris TB, Launer LJ, Eiriksdottir G, et al. Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility–Reykjavik Study: multidisciplinary applied phenomics. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:1076–1087. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klein R, Davis MD, Magli YL, et al. The Wisconsin Age-Related Maculopathy Grading System. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1128–1134. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klein R, Meuer SM, Moss SE, Klein BE, Neider MW, Reinke J. Detection of age-related macular degeneration using a nonmydriatic digital camera and a standard film fundus camera. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:1642–1646. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.11.1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein R, Klein BE, Knudtson MD, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in 4 racial/ethnic groups in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conroy RM, Pyorala K, Fitzgerald AP, et al. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE project. Eur Heart J. 2003;24 doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00114-3. 987e1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saczynski JS, Jonsdottir MK, Garcia ME, et al. Cognitive impairment: an increasingly important complication of type 2 diabetes. The Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility–Reykjavik Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:1132–1139. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams MKM, Simpson JA, Richardson AJ, et al. Can genetic associations change with age? CFH and age-related macular degeneration. Human Molecular Genetics. 2012;21:5229–5236. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jylhava J, Eklund C, Jylha M, et al. Complement factor H 402His variant confers an increased mortality risk in Finnish nonagenarians: The Vitality 90+ study. Experimental Gerontology. 2009;44:297–299. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher D, Li C, Chiu M, et al. Impairments in hearing and vision impact on mortality in older persons: the AGES-Reykjavik Study. Age Ageing. 2014;43:69–76. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.