Abstract

Alexander disease is a primary genetic disorder of astrocyte caused by dominant mutations in the astrocyte-specific intermediate filament glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). While most of the disease-causing mutations described to date have been found in the conserved α-helical rod domain, some mutations are found in the C-terminal non-α-helical tail domain. Here, we compare five different mutations (N386I, S393I, S398F, S398Y and D417M14X) located in the C-terminal domain of GFAP on filament assembly properties in vitro and in transiently transfected cultured cells. All the mutations disrupted in vitro filament assembly. The mutations also affected the solubility and promoted filament aggregation of GFAP in transiently transfected MCF7, SW13 and U343MG cells. This correlated with the activation of the p38 stress-activated protein kinase and an increased association with the small heat shock protein (SHSP) chaperone, αB-crystallin. Of the mutants studied, D417M14X GFAP caused the most significant effects both upon filament assembly in vitro and in transiently transfected cells. This mutant also caused extensive filament aggregation coinciding with the sequestration of αB-crystallin and HSP27 as well as inhibition of the proteosome and activation of p38 kinase. Associated with these changes were an activation of caspase 3 and a significant decrease in astrocyte viability. We conclude that some mutations in the C-terminus of GFAP correlate with caspase 3 cleavage and the loss of cell viability, suggesting that these could be contributory factors in the development of Alexander disease.

Keywords: GFAP, Mutation, Alexander disease, Intermediate filament, Stress, Small heat shock protein

Introduction

Alexander disease (AxD) is a rare and often fatal neurological disorder that has been divided into three subtypes based on the age of onset [1]. The infantile form, which occurs within the first 2 years of life, is currently the most common. This form of AxD is often associated with an aggressive disease progression and characterized by dramatic changes in white matter and the loss of myelin, leading to the usual classification of AxD among the leukodystrophies [2]. The juvenile and adult forms are associated with cerebellum and brainstem pathology. Leukodystrophy is less apparent in these later-onset forms of AxD and is sometimes completely absent [3,4]. A prominent neuropathological feature of all forms of AxD is the presence of Rosenthal fibers, ubiquitinated protein inclusions in the cytoplasm of astrocytes composed of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and containing the small heat shock proteins (SHSPS) αB-crystallin and HSP27 in the cytoplasm of astrocytes [5–7].

The molecular basis of AxD was unknown until the serendipitous finding that transgenic mice engineered to constitutively overexpress human GFAP developed a lethal phenotype associated with the formation of GFAP inclusions throughout the central nervous system, which are morphologically and biochemically similar to Rosenthal fibers [8,9]. This unexpected discovery strongly suggested that altering GFAP protein levels might be responsible for AxD. Accordingly, sequencing of GFAP gene in autopsy-confirmed AxD cases revealed single nucleotide coding changes that predicted amino acid substitutions throughout the GFAP protein [10]. Since that initial discovery, there are now 62 different GFAP mutations associated with AxD and interestingly these mutations are distributed throughout the entire GFAP protein sequence. Four mutational hotspots have emerged affecting residues R79, R88, R239 and R416. These account for more than half of all reported cases of AxD (see website information at http://www.waisman.wisc.edu/alexander/). Although most of these mutations are missense and located within the highly conserved rod domain of GFAP, some insertional and frame-shift mutations have also been identified. These include an in-frame deletion–insertion of two amino acids (K86V87delinsEF) [3], a duplication (R126L127dup) [3], an insertion (Y349Q350insHL) [11], and D417M14X out-of-frame mutation, in which 16 amino acids at the C-terminal of the tail domain are completely altered [12]. All mutations detected so far are heterozygous coding mutations, which are genetically dominant and therefore are expected to act in a gain-of-function fashion.

Like other intermediate filament (IF) family members, GFAP has a characteristic tripartite domain structure comprising a central α-helical rod domain flanked by non-α-helical N-terminal “head” and C-terminal “tail” domains [13]. The GFAP rod domain is flanked by consensus LNDR and TYRKLEGGE motifs that are evolutionary highly conserved throughout the whole IF family [14,15]. Mutations in these motifs found in other IF protein disorders usually correlate with the severest forms of the diseases [16,17] (see http://www.interfil.org). Although regions containing these motifs have been crystallized for vimentin [18,19], our knowledge of the important higher-order interactions within IFs is limited to low-resolution studies [20–22]. Therefore the full structural impact of GFAP mutations has yet to be fully detailed.

The non-α-helical head and tail domains are structurally the most variable among IF proteins in terms of size and primary sequence [23]. Their contributions to filament assembly vary depending on the IF protein considered [14]. For GFAP, the tail domain is reported to be important for filament assembly and function [24,25] and contains the R416W mutation, which is the cause of both sporadic and inherited AxD. Five other mutations have been found in this GFAP domain [12,26–30]. Here, we investigate the effects of these other tail mutations on GFAP assembly in vitro and in cultured cells. We find that the effects of the C-terminal GFAP tail mutants are dominant, affecting filament assembly in a way that promotes aggregate formation, increases SHSP sequestration and correlating with both the activation of p38 kinase and a significant decrease in cell viability.

Material and methods

Plasmid construction and site-directed mutagenesis

GFAP mutations were introduced by site directed mutagenesis (QuickChange, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) with use of wild type (WT) GFAP, corresponding to the most abundant splice variant GFAPα expressed in astrocytes [31]. For transient expression into tissue culture cells, the various GFAP constructs were subcloned into the pcDNA3.1(−) vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) [32]. All newly generated GFAP mutants were verified by sequencing before use. For expression in bacteria, both WT and mutant GFAP in the PCDNA 3.1(−) vectors were subcloned into the bacterial expression vector pET23b (Novagen, Nottingham, UK) with use of the XbaI and EcoRI restriction sites.

Expression and purification of recombinant GFAPs

The bacterial expression vector containing either WT or mutant GFAP was transformed into the host Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) PLYSS (Novagen, Nottingham, UK) and inclusion bodies prepared as described previously [32]. The expressed proteins were further purified from inclusion bodies by ion exchange chromatography as described [32,33], except that an AKTA prime plus system equipped with DEAE-Sepharose and CM-Sepharose Fast Flow columns (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) were used in the purification. Recombinant human R416W and the GFAP iso form GFAPδ were purified as described previously [32,33]. αB-crystallin was purified from bovine eye lenses as described [34] using a Sephacryl S-400 HR gel filtration column (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden).

In vitro assembly and sedimentation assay

In vitro assembly was carried out as described previously [32,33] and the efficiency of in vitro assembly was assessed by high-speed sedimentation assay [35]. To investigate the extent of filament–filament interactions after filament assembly, samples were subjected to low-speed centrifugation at 3000×g for 5 min at room temperature in a benchtop centrifuge (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The amount of GFAP in the supernatant and pellet fractions was analyzed by an image analyzer (ImageQuant 350, GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) and quantified using the image analysis software (ImageQuant TL 7.0, GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden).

For cosedimentation assays, WT or mutant GFAP was mixed with αB-crystallin in low-ionic strength buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA, and 1 mM DTT) at the indicated molar ratios. After assembly, samples were subjected to a low speed centrifugation assay and the supernatant and pellet fractions were compared by SDS-PAGE as described above.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

GFAP filament morphology was determined by negatively staining with 1% (w/v) uranyl acetate (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) followed by electron microscopy (Hitachi H-7500) essentially as described [32]. Measurement of filament length and diameter was performed on enlarged electron micrographs using the Image J software (National Institute of Health, USA).

Cell cultures and transient transfection

Human breast cancer epithelial MCF7 cells were obtained from the European Collections of Cell Cultures (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Human adrenal cortex carcinoma SW/cl.1 and SW13/cl.2 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Robert Evans (University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver). The human astrocytoma cell line U343MG was a gift from Dr. J. T. Rutka (Division of Neurosurgery, University of Toronto, Toronto) and they were grown essentially as described [32].

For transient transfection studies, plasmid DNA was prepared by PureLink™ HiPure plasmid Midi-Prep kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cells on 13-mm coverslips at a density of 40%–50% confluency were transfected using GeneJuice® transfection reagent (Novagen, Nottingham, UK) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In some experiments, cells were cotransfected with a reporter plasmid pDsRed2-Mito (Clontech Laboratories, CA) to identify transfected cells. Cells were allowed to recover for 48 h before further processing for immunofluorescence microscopy.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells grown on coverslip were processed for indirect immunofluorescence microscopy essentially as described [32]. The following primary antibodies used in this study were mouse monoclonal anti-GFAP (GA-5, 1:500, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), monoclonal anti-human GFAP (SMI-21, 1:500, Covance, Princeton, NJ), monoclonal anti-αB-crystallin (2D2B6, [36]), rabbit polyclonal anti-GFAP (1:200, DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA) and polyclonal anti-vimentin (clone 3052, 1:200, [37]) antibodies. Primary antibodies were detected using Alexa® 488 (1:600) or Alexa® 594 (1:600) conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Slides were observed using a LSM 510 confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Jena, Germany) taking 1.0 μm optical sections. Images were collected in multi-track mode and processed for figures using Adobe® Photoshop CSII (Adobe System, San Jose, CA). Quantification of the GFAP filament phenotypes was performed by visual assessment of various staining patterns in transfected cells. For each DNA construct, cells on three coverslips were counted and approximately 200–250 transfected cells were assessed per coverslip.

Cell fractionation and immunoblotting analysis

Cells grown on 10-cm2 Petri dishes were transfected with control vector (pcDNA3.1) or the same vector containing either WT or mutant GFAP. At 48 h after transfection, cells were lysed using two different extraction buffers, designed to test the resistance of GFAP filaments and aggregates to extraction, essentially as described previously [32]. Briefly a mild extraction buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.6, 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktails (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 1 mM PMSF) and a harsh extraction buffer (mild extraction buffer containing 0.5% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate and 0.1% (w/v) SDS) were used to prepare supernatant and pellet fractions. Pellet fractions were resuspended in Laemmli’s sample buffer, in a volume that was proportional to the supernatant before analysis by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

After immuneblotting essentially as described [32], the following primary antibodies were used to identify specific proteins; mouse monoclonal anti-GFAP (GA5, 1:5000, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), monoclonal anti-GFAP (cl.52, raised against a peptide sequence from codon 418 to 432 of the human GFAP, 1:1000, BD Transduction Laboratories, San Diego, CA), monoclonal anti-human GFAP (SMI-21, 1:5000, Covance, Princeton, NJ), monoclonal anti-HSP27 (G3.1, 1:2000, Abcam, Cambridge MA), monoclonal anti-αB-crystallin (2D2B6, 1:1000, [36]), monoclonal anti-actin (1:2000, AC-40, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), monoclonal anti-ubiquitin (1:1000, P4D1, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), monoclonal anti-caspase 3 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-GFAP (1:2000, DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA) and polyclonal anti-cyclinD1(1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) antibodies. In some experiments, the membrane was probed with rabbit monoclonal anti-p38 kinase and anti-phospho-p38 kinase antibodies (both from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) diluted by 1:1000 in blocking buffer. Primary antibodies were detected by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA) diluted by 1:2000 in blocking buffer, followed by washing with TBS for 30 min with several changes. Antibody labeling was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Western Lightning Plus-ECL, Perkin Elmer) with use of a luminescent image analyzer (ImageQuant 350, GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden). The strength of signal was quantified using the image analysis software (ImageQuant TL 7.0, GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden).

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, Promega, Madison, WI) assay. This assay reflects cell viability and proliferation as well as integrity of the mitochondria [38]. Briefly, 5×104 U343MG cells were seeded in 24-well plates containing 0.5 ml of growth medium. Cells were cultured for 24 h prior to transfection with either WT or mutant GFAP. Cells transfected with empty pcDNA3.1 DNA vector were used as a control. At 48 h after transfection, culture medium was replaced by fresh medium containing 0.5 mg/ml MTT. After incubation with MTT at 37 °C for 4 h, 0.5 ml of dimethyl sulfoxide was added to each well and incubated for 5 min to dissolve formazan crystals. Four 50 μl aliquots were then transferred to a 96-well plate, and absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 560 nm on a microplate reader.

Results

Impact of disease-causing mutations upon GFAP assembly in vitro

To determine how C-terminal AxD-causing mutations affected the assembly properties of GFAP, in vitro assembly studies were performed. Five different C-terminal GFAP mutants (N386I, S393I, S398F, S398Y and D417M14X) were generated by site directed mutagenesis and then used to produce recombinant protein (Fig. 1A) suitable for studies in vitro. The expression and purification of WT GFAP are shown as an example (Fig. 1B). This protein assembled into typical 10-nm filaments that were many microns in length (Fig. 2A). During the assembly of type III IF proteins like vimentin, desmin and GFAP, the in vitro assembly goes through several distinct and well-characterized stages [14]. The first stage is the formation of the unit length filament (ULF). These are usually 60–70 nm long. ULFs then anneal end to end to form filaments that are wider in diameter (~15 nm), but then these undergo compaction to form the mature filament that is 10-nm wide and many microns long.

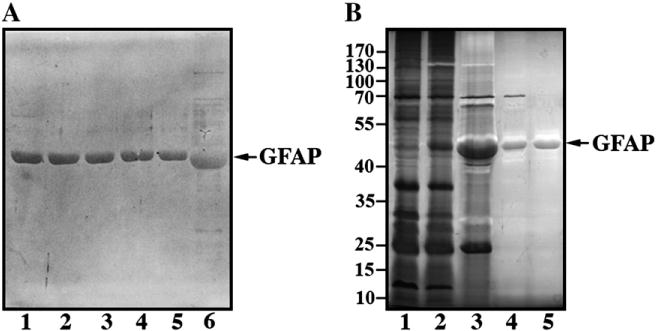

Fig. 1.

Expression, purification and electrophoretic analysis of WT and mutant GFAPS. (A) Purified recombinant GFAP was analyzed by 12% (w/v) SDS-PAGE and visualized by silver staining. Lane 1, WT GFAP; lane2, N386I GFAP; lane 3,S393I GFAP; lane 4, S398F GFAP; lane 5, S398Y GFAP. Note the relative increase in electrophoretic mobility of the D417M14X GFAP (A, lane 6). (B) WT GFAP was used to illustrate the expression and purification of recombinantly produced proteins. Total protein profiles of extracts from induced (B, lane 1) and IPTG-induced (B, lane 2) bacteria protein extracts are shown. After inclusion body preparation, one major protein band is seen (B, lane 3), which was subsequently purified to homogeneity by anion (B, lane 4) and cation exchange (B, lane 5) column chromatography. Samples were separated by 12% (w/v) SDS-PAGE and proteins visualized by silver staining. The relative electrophoretic mobility of molecular weight markers (in kDa) is indicated.

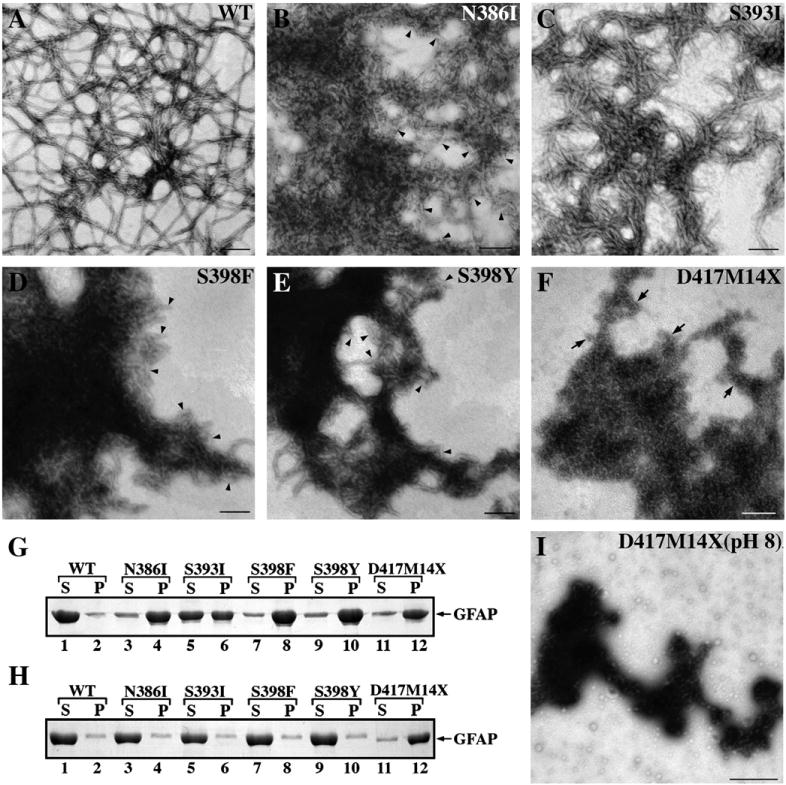

Fig. 2.

Effects of GFAP mutation upon the in vitro filament assembly. (A−F) Purified WT and mutant GFAP at a concentration of 0.3 mg/ml were assembled in vitro. Samples were negatively stained and visualized by TEM. In panels B,D and E, arrowheads indicate the presence of ULF-like structures. Bar=200 nm. (G) WT and mutant GFAP were subjected to low-speed centrifugation assay and the resulting supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. Under these assay conditions, WT GFAP remained mostly in the supernatant fraction (G, lane 1, labeled S). While S393I GFAP was found equally distributed in the supernatant and pellet fractions (G, lanes 5 and 6), other GFAP mutants were found mainly in the pellet fraction (G, lanes 4, 8, 10 and 12). (H) When preassembled materials in low ionic strength buffer (10 mM Tris−HCl pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA, and 1 mM DTT) were subjected to the same assay, the D417M14X mutant was found mainly in the pellet fraction (H, lane 12, labeled P), suggesting that aggregate formation had occurred early in the assembly protocol. (I) Electron microscopy of negatively stained samples of preassembled materials showed that the tail frameshift mutant had aggregated.

All the GFAP mutations studied here perturbed in vitro filament assembly. Some inhibited the annealing of the ULFs into filaments (N386I, S398F and S398Y) and one (S393I) appeared to affect the compaction stage of filament assembly. The N386I mutation prevented GFAP filament assembly by forming structures that appeared to resemble ULFs (Fig. 2B, arrowheads), but which are 62.3 ± 4.7 nm long, variable in width and aggregation prone. Some end to end annealing of these ULFs was possible as seen by the presence of some filamentous material (Fig. 2B). By contrast, S393I GFAP was able to form short filament-like structures, but these had not compacted properly as their diameters were irregular (Fig. 2C). The S398F (Fig. 2D) and S398Y (Fig. 2E) GFAP mutants both formed mainly ULF-like structures (Figs. 2D and E, arrowheads) that tend to aggregate. The most dramatic assembly defect was observed for the frameshift mutation in codon 417 (D417M14X), which is predicted to generate a protein product of 431 residues [12]. This D417M14X deletion mutant failed to self-assemble into filaments, but instead formed small (23.8 ± 3.4 nm) particles that tended to aggregate strongly (Fig. 2F, arrows).

A low-speed sedimentation assay ([39]; Fig. 2G and Supplementary Fig. 1A) was used to determine the effect of the C-terminal mutations upon GFAP assembly in vitro. Most of the WT GFAP remained in the supernatant fraction under these assay conditions (Fig. 2G, lane 1), with only 12% protein being pelleted (Fig. 2G, lane 2). These data indicate that the assembled filaments had a low tendency to self-associate and to form filament complexes that could be sedimented at 3000 × g after 5 minute centrifugation. The high-speed sedimentation assay confirmed that virtually all the GFAP could be pelleted using g-forces that sediment individual filaments (Supplementary Fig. 1B). TEM confirmed the presence IFs, which were very abundant in this sample.

All the GFAP mutants sedimented more efficiently than WT protein in the low speed sedimentation assay, with 79% of N386I (Fig. 2G, lane 4), 47% of S393I (Fig. 2G, lane 6), 86%of S398F (Fig. 2G, lane 8), 81% of S398Y (Fig. 2G, lane 10) GFAP and 77% of the D417M14X frameshift mutant (Fig. 2G, lane 12) being found in the pellet fraction. These data confirm that the assembled polymers of all the C-terminal GFAP mutants are more prone to self-aggregation than the WT protein.

The D417M14X frameshift GFAP mutant showed a greatly increased tendency to polymerize even under unfavorable buffer conditions. The proportion of mutant GFAP in the pellet fraction (Fig. 2H, lane 12, labeled P) was markedly greater than that of the WT GFAP (Fig. 2H, lane 1, labeled S) and the other mutant GFAPs (Fig. 2H, lanes 3, 5, 7 and 9, labeled S), which under these conditions remained mostly in the soluble fractions. These results suggest that the D417M14X frameshift mutant promoted oligomerization and subsequent aggregation of the assembled structures as confirmed by electron microscopy (Fig. 2I).

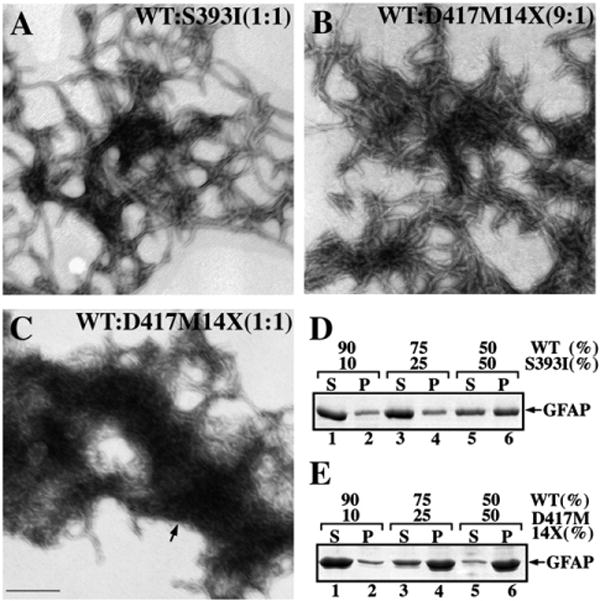

To demonstrate the dominant effects of the C-terminal tail mutants, WT GFAP was mixed with different proportions of either S393I or D417M14X GFAP, two mutants with different effects upon the in vitro filament assembly. When S393I and WT GFAP were coassembled in 10:90 and 25:75 ratios, the filaments formed were not dramatically altered in morphology (data not shown) compared with those made from WT GFAP alone (Fig. 2A). Increasing the proportion of S393I GFAP to 50% in the assembly mixture, however, resulted in filaments that appeared shorter, less uniform and had a marked tendency to aggregate (Fig. 3A). When compared to S393I, the D417M14X mutant had the most deleterious effect upon WT GFAP assembly. Coassembly studies showed that even 10% D417M14X GFAP altered the morphology of the assembled filaments (Fig. 3B). These filaments appeared more irregular in width, were shorter and more angular. With increasing D417M14X GFAP levels in the mixture with WT GFAP, more filament disruption was observed. In the 1:1 mixture large electron dense structures appeared, indicating a greater tendency for the assembled material to aggregate (Fig. 3C, arrow). Low-speed centrifugation assay confirmed that increasing the proportion of the S393I (Fig. 3D, lane 6) or D417M14X mutant (Fig. 3E, lanes 4 and 6) also increased the proportion of GFAP in the pellet fractions. These data show that both the S393I GFAP and D417M14X GFAP act in a dominant manner over the WT protein with respect to GFAP assembly in vitro.

Fig. 3.

The dominant effect of the GFAP tail mutants revealed by in vitro assembly studies. WT GFAP was coassembled with either S393I (A) or D417M14X (B and C) GFAP in the indicated ratios. After assembly, samples were negatively stained and visualized by TEM. Bar=200 nm. (D, E) Supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions from the low speed sedimentation assay were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue R250 staining. Notice that increasing the ratio of mutant GFAP in the assembly mixtures led to an increased GFAP signal in the pellet fractions.

The N386I mutation alters the binding of the GA5 antibody to GFAP

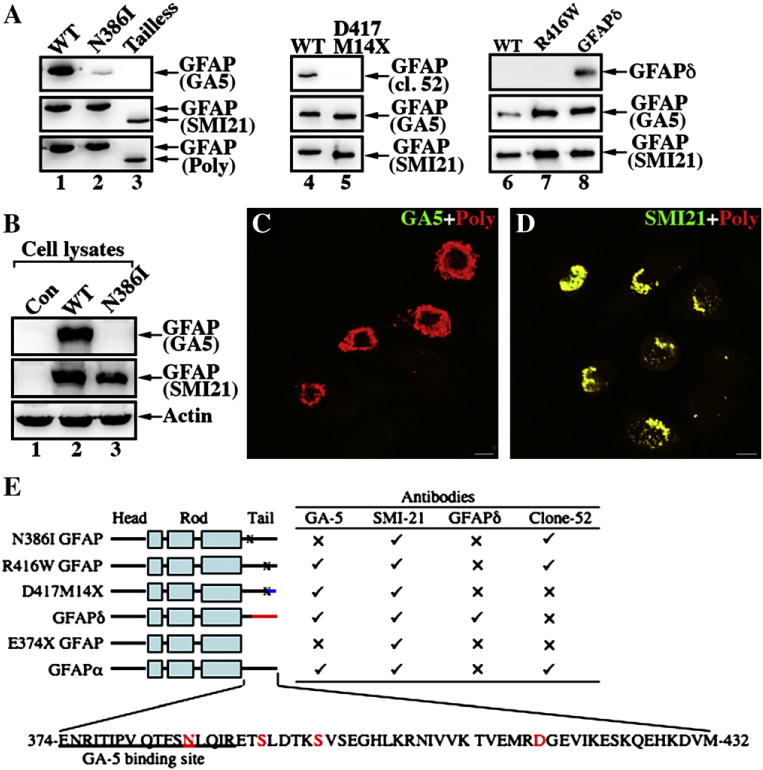

In the course of our studies, we noticed that the N386I mutant GFAP was virtually undetectable by the monoclonal anti-GFAP GA5 antibody (Fig. 4A, lane 2), despite the fact that both the monoclonal SMI21 and the polyclonal anti-GFAP antibodies could readily detect this mutant (Fig. 4A, lane 2). The GA5 antibody was able to detect WT (Fig. 4A, lanes 1,4 and 7) and R416WGFAP (Fig. 4A, lane 7) as well as GFAPS (Fig. 4A, lane 8), a natural occurring GFAP isoform with unique C-terminal 42 amino acid sequence in its C-terminal domain [40]. In addition, the clone 52 (cl.52) monoclonal antibody raised against the C-terminal tail domain of human GFAP recognized WT GFAP (Fig. 4A, lane 4) but not the D417M14X mutant (Fig. 4A, lane 5). Removing the GFAP C-terminal tail domain by generating a tailless GFAP (E374X) prevented GA5 antibody detecting the truncated GFAP (Fig. 4A, lane 3) demonstrating that the GA5 epitope was contained within this domain.

Fig. 4.

Epitope mapping of a monoclonal antibody GA-5 binding site on GFAP. (A) Purified recombinant GFAP variants were immunoblotted with the indicated anti-GFAP antibodies. The ability of the antibodies to detect WT and mutant GFAP proteins is summarized (E). (✓), Immunopositive; (x), immunonegative. (B) MCF7 cells (B, lane 1; untransfected) were transfected with WT (B, lane 2) or N386I (B, lane 3) GFAP. The total cell lysates were probed with anti-GFAP antibodies as indicated. Notice that the GA5 antibody failed to recognize N386I GFAP (lane 3). (C, D) MCF7 cells transiently transfected with N386I GFAP were fixed 48 h after transfection and visualized by double-label immunofluorescence microscopy. Cells were stained with either GA5 (C, green channel) or SMI-21 (D, green channel) antibody and counterstained with a polyclonal anti-GFAP antibody to reveal transfected cells (C, D; red channel). Merged images are shown. Note that transient expression of N386I GFAP in MCF7 cells resulted in the formation of GFAP-containing aggregates that were readily stained by the SMI antibody and a polyclonalanti-GFAP antibody, but not GA5 antibody. Bar = 10 μm. (E) A schematic view of GFAP structural organization and localization of alterations in the GFAP variants. GFAP comprises a central α-helical rod domain, flanked by non-α-helical head and tail domains (denoted by black bars). Within this rod domain, the heptad repeat-containing segments (denoted by boxes) are separated by short linker sequences (denoted by black bars). The blue (D417M14X with 14 novel residues after the codon 417) and red (GFAPδ with 42 novel residues after the codon 391) color-coding of the C-terminal domain gives a schematic representation of where these sequences differ to GFAPα. The single-letter amino acid code for tail domain of the WT GFAP (GFAPα) is also given and the disease-causing mutations studied are indicated (red letters). The sequence containing the GA5 epitope is underlined.

We confirmed by both immunoblotting (Fig. 4B) and immunofluorescence (Figs. 4C and D) techniques that the GA5 antibody was also incapable of detecting transfected N386I mutant GFAP in human breast cancer epithelial MCF7 cells, although WT GFAP was readily detected. Taken together, we conclude that the epitope of the GA5 antibody locates to a region immediately after the rod domain, but preceding the last 42 amino acids in the C-terminal tail of GFAP (Fig. 4E).

Effect of GFAP mutations upon IF network formation in SW13 cells

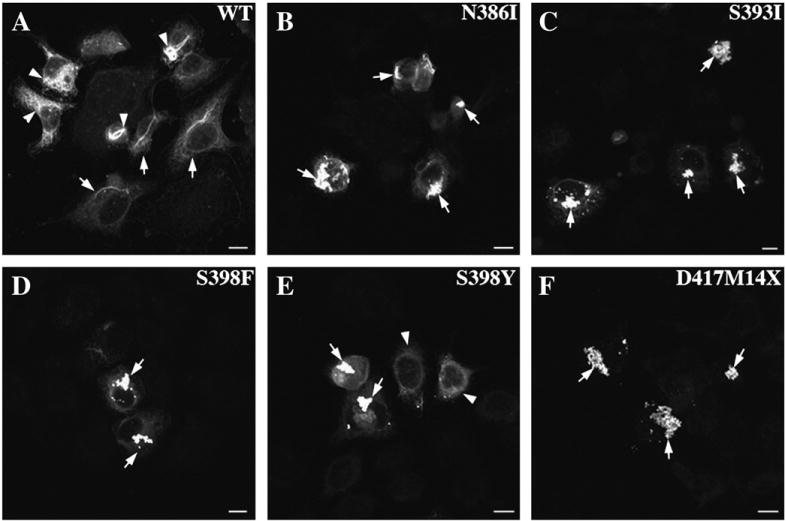

We used transient transfection assays to investigate the effect of the GFAP C-terminal tail mutations on the formation of GFAP networks in cells. Transient transfection into SW13/cl.2 (vim−) cells, which do not express any cytoplasmic IFs [41] was used to assess de novo IF network formation of the various GFAP mutants. WT GFAP forms filament networks in these cells (Fig. 5A, arrows), although filament bundles and aggregates were also observed (Fig. 5A, arrowheads). In contrast, all the GFAP C-terminal tail mutants failed to form filamentous networks, but instead formed clusters of punctuate aggregates with no obvious filamentous substructure (Figs. 5B–F, arrows).

Fig. 5.

Effect of GFAP tail mutations upon the de novo IF network formation. SW13/cl.2 (vim−) cells were transiently transfected with either WT or mutant GFAP. At 48 h after transfection, cells were processed for immunofluorescence microscopy and probed with the SMI-21 monoclonal anti-GFAP antibody. When expressed in this cell line, WT GFAP assembled into filamentous networks (A, arrows) that tended to bundle (A, arrowheads). In contrast, mutant GFAPs mainly formed cytoplasmic aggregates in transfected cells (B–F, arrows). Bar = 10 μm.

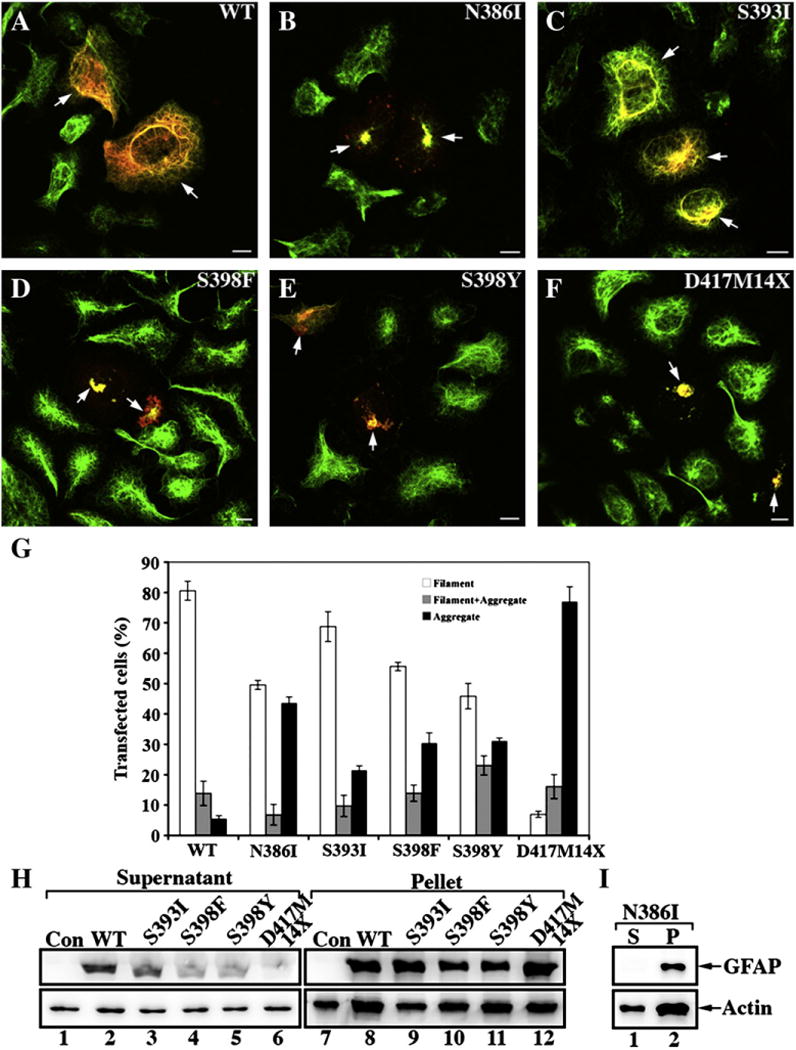

Vimentin is a natural coassembly partner of GFAP that is required for filament formation in astrocytes [42]. We therefore also selected the SW13/cl.1 (vim+) cell line that expresses vimentin to analyze the ability of GFAP and its mutants to integrate into an endogenous vimentin IF network. As expected, transient expression of WT GFAP resulted in its incorporation into the endogenous vimentin IF networks (Fig. 6A, arrows) in 80% of the transfected cells (Fig. 6G). In contrast, expression of N386I (Fig. 6B, arrows), S398F (Fig. 6D, arrows) and S398Y (Fig. 6E, arrows) GFAP mutants resulted in aggregate formation in 43%, 30% and 31% of transfected cells (Fig. 6G). In 77% of transfected cells (Fig. 6G), the D417M14X GFAP (Fig. 6F, arrows) also formed aggregates. By comparison, the S393I GFAP produced the least severe phenotype as 69% of the transfected cells (Fig. 6G) contained filament networks (Fig. 6C) and only 21% of transfected cells contained aggregates. Interestingly the S393I GFAP didn’t appear to incorporate to the same extent throughout the endogenous vimentin network, but rather was concentrated in aggregates in the perinuclear region (Fig. 6C, arrows). For all the GFAP mutants except for S393I GFAP (Fig. 6C), the endogenous vimentin IF networks were also disrupted (Figs. 6B, D–F, green channel) and colocalized with the mutant GFAP (Figs. 6B, D–F, red channel) in aggregates.

Fig. 6.

Transient expression of mutant GFAPs leads to aggregate formation in SW13/cl.1 (Vim+) cells. SW13/cl.1 (Vim+) cells transiently transfected with either WT (A) or mutant (B–F) GFAP were processed for double label immunofluorescence microscopy with antibodiesto both GFAP (red channel) and vimentin (green channel). For each transfection, cells on three coverslips were counted and their staining patterns (Filament; Filament + Aggregate; Aggregate) assessed. Quantification of the various patterns observed for transfected SW13/cl.1 (Vim+) cells are shown as mean ± SE and presented as bar charts (G). All the GFAP mutants resulted in a significant increase in GFAP aggregation in transiently transfected cells with the D417M14X deletion mutant predominantly forming protein aggregates. Bar=10 μm. (H,I) SW13/cl.1 (Vim+) cells transfected with the indicated GFAP construct were then extracted using a mild extraction protocol. The resulting supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with GA5 (H) and SMI-21 (I) monoclonal anti-GFAP antibodies. Actin was used as a sample loading control. Uncropped images of blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

The high transfection efficiency of the SW13/cl.1 cells allowed us to assess biochemically the solubility properties of the transfected GFAPs. Immunoblotting of supernatant and pellet fractions prepared from WT or mutant GFAP-transfected cells revealed that WT GFAP was detected in both the supernatant and pellet fractions (Fig. 6H, lanes 2 and 8). In contrast, nearly all N386I (Fig. 6I, lane 2), S398F (Fig. 6H, lane 10), S398Y (Fig. 6H, lane 11) mutant GFAPs were found in the pellet fractions, consistent with the formation of cytoplasmic aggregates. The D417M14X mutant GFAP (Fig. 6H, lane 12) was found almost entirely in the pellet fraction. The S393I mutant GFAP was somewhat intermediate between these two extremes of the WT and D417M14X GFAP, although the majority of the expressed S393I GFAP was found in the pellet fraction (Fig. 6H, lane 9), indicating that this point mutation had also adversely affected the solubility of the GFAP.

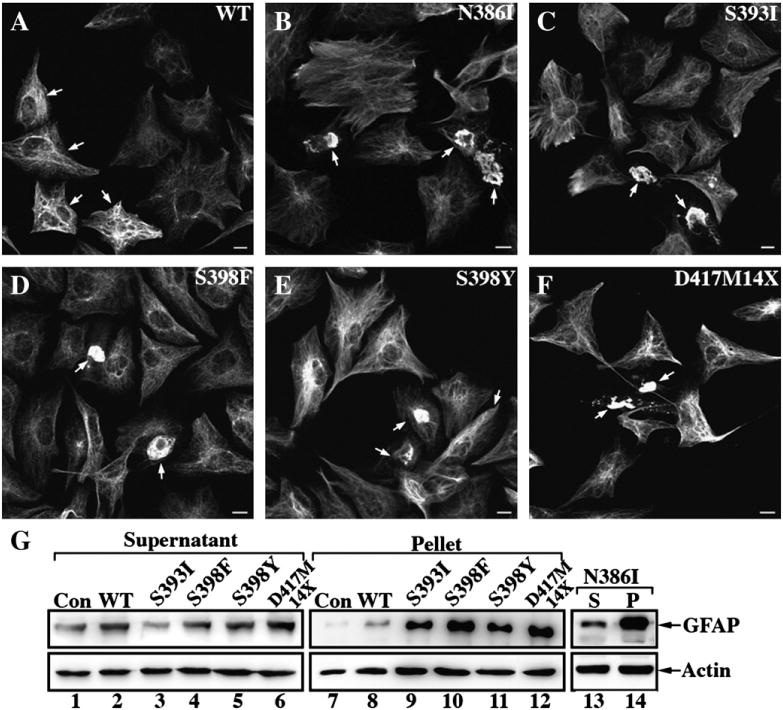

Aggregate formation by mutant GFAP in transfected human astrocytoma U343MG cells

To try to mimic better the cellular environment of the astrocyte, U343MG human astrocytoma cells were transiently transfected with either WT or mutant GFAP and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy. Transfected cells were identified using a reporter plasmid pDsRed2-Mito (Supplementary Fig. 3), which was cotransfected along with the various GFAP expression constructs. WT GFAP incorporated into the endogenous GFAP network without obviously altering the endogenous distribution (Fig. 7A, arrows). All the GFAP mutants, however, formed cytoplasmic aggregates and also disrupted the endogenous GFAP networks (Figs. 7, B–F, arrows).

Fig. 7.

Filament organization and solubility properties of WT and mutant GFAPs in astrocytoma U343MG cells. The human astrocytoma cell line, U343MG, was cotransfected with the indicated GFAP constructs and a reporter plasmid for cell identification purpose (Supplementary Fig. 3). At 48 h after transfection, cells were examined by immunofluorescence microscopy using a monoclonal anti-GFAP antibody (SMI-21). When transfected into U343MG cells, WT GFAP formed mainly filamentous networks that extended throughout the cytoplasm (A, arrows). In contrast, transient expression of mutant GFAP resulted in the formation of cytoplasmic aggregates (B–F, arrows). Bar=10 μm. (G) The solubility properties of the transfected GFAPs were analyzed by cell fractionation followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. WT or mutant GFAP-transfected cells were extracted using the harsh extraction protocol and the resulting supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions were probed with anti-GFAP antibodies GA5 (G, lanes 1–12) and SMI-21 (G, lanes 13 and 14). Under these extraction conditions, the endogenous GFAP in untransfected cells was found almost entirely in the supernatant fraction (G, lane 1). Although transfected WT GFAP was detected predominantly in the soluble fraction (G, lane 2), after transfection with the mutant constructs the GFAP was found mainly in the pellet fractions (G, lanes 9–12 and 14). Additional signals above and below the prominent GFAP-positive band are shown in uncropped images of blots (Supplementary Fig. 5). Actin was again usedasaloading control.

GFAP expression levels and its solubility were analyzed by immunoblotting of the supernatant and pellet fractions prepared from the transfected cells. After transfection, total GFAP levels were increased between 1.5 and 2.4 folds over the endogenous baseline levels (Supplementary Fig. 4). Levels were elevated in both the supernatant and pellet fractions, but all the GFAP mutants induced a greater increase in the pellet fraction(Fig. 7G, lanes 9–12 and 14). The endogenous GFAP could be extracted completely from untransfected cells (Fig. 7G, lane 1) and this was not dramatically changed after transfection with WT GFAP (Fig. 7G, lane 2) because only 8% was detected in the pellet fraction (Fig. 7G, lane 8). In contrast, the GFAP levels in the pellet fractions of cells transfected with the mutant GFAPs were all increased (Fig. 7G, lanes 9–12 and 14), consistent with their sequestration into cytoplasmic aggregates.

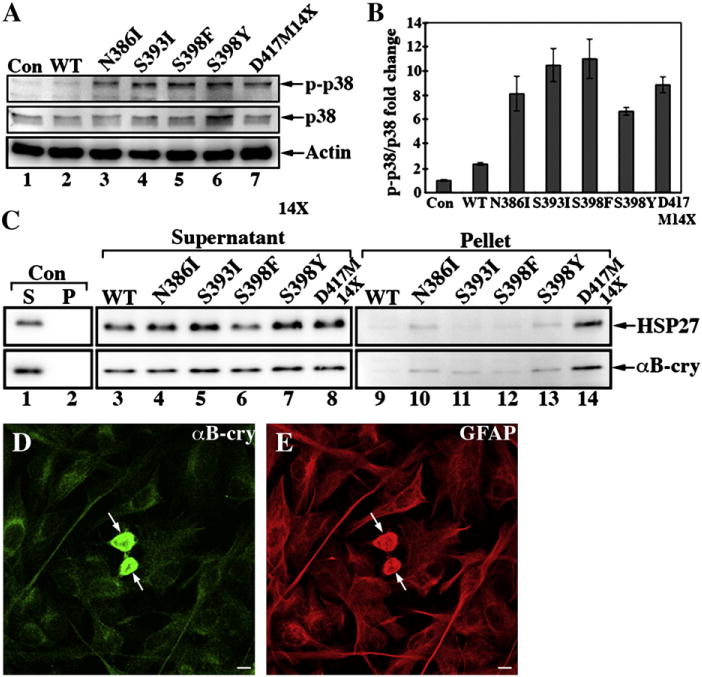

Activation of stress kinases and association of sHSPs with mutant GFAP in U343MG transfected cells

Stress kinases are activated by the over-expression of other GFAP mutants (R239C [43,44] and R416W GFAP [33]) and therefore we monitored the phosphorylation status of p38 kinase (p38) in our transiently transfected astrocytoma cells (Fig. 8A). In contrast to untransfected (Fig. 8A, lane 1) or WT GFAP-transfected (Fig. 8A, lane 2) cells, phosphorylated p38 levels were significantly elevated for those cells transfected with mutant GFAPs (Figs. 8A, lanes 3–7 and B).

Fig. 8.

Activation of p38 kinase and associations with sHSPs by mutant GFAPs intransfected U343MG cells. (A) Total cell lysates prepared from WT or mutant GFAP-transfected U343MG cells were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with antibodies to p38, the phosphorylated form of p38 (p-p38), and lastly actin as a loading control. (B) Quantification of p38 and p-p38 immunoreactive bands from three independent experiments are expressed as mean ± SD and presented as bar charts. Levels of p38 and p-p38 were normalized to the measurement obtained for actin and fold changes are expressed in arbitrary units relative to the untransfected cells. (C) To monitor the distribution of sHSPs, the supernatant and pellet fractions prepared from GFAP-transfected U343MG cells were also probed with antibodies to αB-crystallin and HSP27. Notice that a significant proportion of both HSP27 and αB-crystallin were detected in the pellet fractions (C, lane 14) in D417M14X GFAP-transfected cells. (D, E) The colocalization of αB-crystallin (D, arrows) with the aggregates formed by the D417M14X mutant GFAP (E, arrows) was visualized by double label immunofluorescence microscopy. Bar=10 μm.

As with the R416W mutant GFAP [32], the activation of p38 also coincided with the increased association of HSP27 and αB-crystallin with the GFAP aggregates in transiently transfected cells. Both HSP27 and αB-crystallin could be almost completely extracted from untransfected (Fig. 8C, lane 1) and WT GFAP-transfected cells (Fig. 8C, lane 3). In cells transfected with either S393I or S398F GFAP, however, some αB-crystallin resisted extraction (Fig. 8C, lanes 11 and 12), while HSP27 did not (Fig. 8C, lanes 11 and 12). Both HSP27 and αB-crystallin were detected in the pellet fractions of N386I (Fig. 8C, lane 10) and S398Y (Fig. 8C, lane 13) GFAP-transfected cells, but the most significant increase in the sHSP signals was seen for the D417M14X mutant (Fig. 8C, lane 14). Double label immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrated the colocalization of αB-crystallin (Fig. 8D, arrows) and HSP27 (data not shown) with the GFAP aggregates formed by the D417M14X GFAP (Fig. 8E, arrows). The transient overexpression of the GFAP tail mutants therefore not only activates the stress activated protein kinase pathway, but also leads to an increased association with the sHSPs, HSP27 and αB-crystallin.

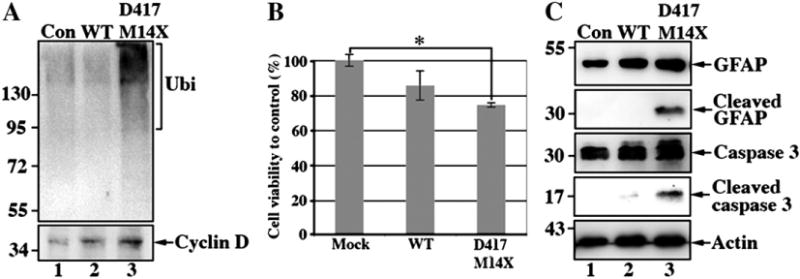

The appearance of GFAP aggregates coincides with impaired proteasome activity, activation of caspase 3 and decreased cell viability in U343MG cells

Altered proteosome function has been reported as a consequence of the accumulation of R239C GFAP [43] and so we investigated whether this is also the case for D417M14X GFAP. Levels of protein ubiquitination were indeed increased in mutant GFAP-transfected cells (Fig. 9A, lane 3) compared to controls (Fig. 9A, lanes 1 and 2). Cyclin D1, a known 20 S proteasome substrate [45], was increased in cells expressing the D417M14X GFAP (Fig. 9A, lane 3). These data suggest that the accumulation of mutant GFAP in transfected U343MG cells increases the levels of ubiquitinated proteins, evidencing compromised proteosome function.

Fig. 9.

Expression of D417M14X GFAP reduces astrocyte viability. (A) D417M14X GFAP inhibits the proteosome as shown by immunoblotting with antibodies to ubiquitin and cyclin D1, respectively. (B) U343MG cells were transfected with the pcDNA 3 vector alone or containing either WT or D417M14XGFAP and left for 48 h prior to measuring cell viability using the MTT assay. Data (bar charts) shown are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was tested using the Student’s t-test and the significance was set at*P<0.005, when compared to cells transfected with control vector. (C) Total lysates prepared from WT or mutant GFAP-transfected cells were probed with antibodies to either GFAP or caspase 3, including one to detect activated caspase 3. Notice that cells transfected with mutant GFAP also contained a ~30 kDa degradation product of GFAP (C, lane 3). Actin was used as a loading control. The relative electrophoretic mobility of certain molecular size markers (in kDa) are indicated.

The accumulation of mutant GFAP could adversely affect cell viability and to test this hypothesis we selected the D417M14X GFAP mutant GFAP for further studies. We measured cell viability in WT and D417M14X GFAP-transfected cells and found a 14% and 25% decrease respectively when compared to cells transfected with a control vector (Fig. 9B). We measured levels of caspase 3 cleavage in WT and mutant GFAP-transfected cells and found cleaved caspase 3 was mainly detected in the D417M14X GFAP-transfected cells (Fig. 9C, lane 3). This was accompanied by the cleavage of GFAP, as detected by immunopositive GFAP fragments in extracts prepared from the mutant GFAP-transfected cells (Fig. 9C, lane 3). No such degradation products were observed in mock or WT GFAP-transfected cells (Fig. 9C, lanes 1 and 2). These GFAP fragments most likely correspond to caspase-cleaved GFAP, as similar sized degradation products were also detected by site-directed caspase-cleavage antibody in damaged astrocytes of the Alzheimer’s disease brain [46]. These results suggest a direct link between the aggregation of the mutant GFAP and the loss of cell viability through the activation of caspase 3.

Discussion

Impact of GFAP tail mutations on IF assembly and network organization

This is the first comprehensive investigation of the effects of the five C-terminal domain mutations in GFAP linked to AxD. The data presented here show that all the point mutations and the one frameshift mutation (1249delG; D417M14X GFAP) affect the in vitro assembly and network formation of GFAP in transiently transfected tissue culture cells. The effects on the in vitro assembly suggest the mutations all affect the formation and subsequent annealing of the ULF.

This study contrasts a recent study of myopathy-causing mutations in desmin [47], where the mutations studied were mostly distal to the conserved RDG-sequence and appeared to compromise the mechanical properties of the filaments and their networks [48] rather than preventing in vitro assembly per se. The GFAP mutations studied here appeared to disrupt in vitro filament assembly at earlier stages affecting the ability of the ULFs to anneal and subsequently compact appropriately. When transfected into tissue culture cells, the GFAP mutants all induced aggregate formation (Figs. 5–7). Interestingly, this was not the case for myopathy-causing mutations in C-terminal tail of desmin [47,48]. There are perhaps important differences in the precise role(s) played by the C-terminal domains of type III IF proteins. Unlike vimentin or desmin, GFAP is altered by gene splicing to produce three different protein products with very distinct C-terminal sequences [31]. It is therefore reasonable to expect that mutations in the C-terminal domain of GFAPα, the most abundant splice variant expressed in astrocytes, is to significantly affect GFAP function.

The C-terminal mutations affect GFAP solubility with increased associations with sHSPs and activation of stress kinases

Of all the mutants that were studied here, the S393I GFAP has been linked to an adult-onset case of AxD (Table 1), which has relatively mild symptoms and disease progression. In agreement with the pathology, the effect of this mutation on the in vitro assembly was the mildest, but did induce a very strong interaction with αB-crystallin in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 6D). This mutant also produced the most obvious shift in GFAP solubility when transfected into U343MG cells. So although the effects on the in vitro assembly as measured by sedimentation assay appeared to be the least dramatic, both the morphological changes and its interaction with αB-crystallin would suggest otherwise. S393 is also a potential phosphorylation site for kinases such as the Ca2+-calmodulin (CaM)-dependent protein kinase 2 [49]. It is too early to speculate on the reason for this apparent anomaly between the studies presented here and symptoms based on a single patient. Nevertheless, these data do confirm that changing the morphology of the assembled GFAP causes an increased association with αB-crystallin, supporting our previous studies [32,33,50].

Table 1.

Clinical features of AxD patients with GFAP tail mutations.

| Nucleotide change (types of mutation) | Amino acid substitution | Types of AxD | Clinical symptoms | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1157A>T (missense) | N386I | Infantile | Multifocal seizures, macrocephaly, hypotonia with spasticity, neurologic deterioration, and white matter abnormalities | [26] |

| 1178G>T missense | S393I | Adult | Spastic paraparesis, bilateral Babinski sign, tetrahyperreflexia, dysphagia, dysarthria pseudobulbar speech, and brain stem atrophy | [27–29] |

| 1193C>T missense | S398F | Adult | Spastic gait, dysarthria, dysphagia, and atrophy of medulla oblongata | [30] |

| 1193C>A missense | S398Y | Adult | Atrophy of medulla oblongata | [27,28] |

| 1247–1249 GGG>GG deletion | D417M14X | Infantile | Frontal cerebral atrophy and white matter abnormalities | [12] |

At the other extreme, the D417M14X GFAP mutant is linked to an infantile form of AxD (Table 1). The sequence changes as a result of the mutation contrast the two naturally occurring splice variants (GFAPδ [40] and GFAPκ [51]) that also dramatically alter the C-terminal sequences of GFAP. The C-terminus of GFAPδ very significantly altered the solubility and function of GFAP [33]. Both GFAPδ and the D417M14X mutant GFAP were incapable of forming 10-nm filaments in vitro, but would do so when mixed with the WT GFAP (GFAPα). Both GFAPδ and the D417M14X GFAP mutant GFAP induced GFAP aggregate formation after transient transfection into tissue culture cells and both induced the activation of stress kinases and the increased association of sHSPs. The difference is that the D417M14X GFAP mutant leads to AxD [12], whereas GFAPδ is associated with long-term quiescence of neural stem cells [52]. Therefore what are the cellular consequences of D417M14X GFAP expression and how does this potentially relate to AxD?

Mechanisms involved in AxD

AxD is a primary genetic disorder of astrocyte, where mutations in GFAP are found in the large majority of AxD patients. Although the genetic basis linking GFAP mutation with AxD is firmly established, the precise detail of the mechanisms by which GFAP mutations lead to the disease have yet to be determined [53]. Previous studies using transient transfection of tissue culture cells had failed to demonstrate that AxD-causing mutant R239C GFAP would decrease cell viability [43] and it was only when primary astrocytes isolated from knocking mice overexpressing R236H GFAP by 2.5 fold was this seen [54]. In another report [55] that used primary astrocyte for transfection, R236H GFAP was also linked to decreased cell viability. When compared to the reported pathology associated with AxD, astrocyte cell death is not reported as a major consequence. In infantile cases, there is considerable loss of white matter through the compromisation of astrocyte function and of course disease progression has reached an end point making it difficult to identify this as an important disease feature [54,56]. This study, in conjunction with previous studies at least now formally poses that reduced astrocyte viability could be a contributory factor in the development of AxD as it is both rod (R239C/H) and tail (D417M14X) mutants that are seen to decrease cell viability.

An increase in absolute levels of GFAP is nevertheless a critical element in AxD pathogenesis, as even the overexpression of WT (GFAPα) GFAP induces pathogenesis in a dose-dependent manner [8,9]. The comprehensive comparison of the remaining C-terminal tail domain mutants in addition to R416W GFAP [32] indicate a range of effects upon in vitro assembly, the sequestration of αB-crystallin and the activation of p38. These collective data suggest that it might not be absolute changes that are important, but rather the altered balance in cellular homeostasis triggered by the presence of the mutant GFAPs that causes AxD. Our data show that extensive aggregate formation leading to the sequestration of sHSPs, the activation of p38 stress kinase and a greater decline in cell viability is driven by the over-expression of the mutant GFAPs. Which of these is the more important is still an open question.

The mechanism by which GFAP could induce astrocyte death is unknown. Based on the observations that αB-crystallin negatively regulates apoptosis through multiple mechanisms [57–59], sequestration of αB-crystallin into GFAP aggregates could result in depletion of its soluble cytoplasmic pool and therefore compromise its anti-apoptotic activity. Previous studies have also shown that αB-crystallin interacts with IFs and by so doing minimizes inter-filament associations [60] and reorganizes abnormal IF accumulations [61,62]. We therefore assessed whether GFAP filament aggregation in vitro and after transient transfection could be reversed by the presence of αB-crystallin (Supplementary Fig. 6), but we could only confirm an increased association of this chaperone with the pelletable fractions of the mutant GFAPs. Therefore these data suggest that preventing GFAP aggregation per se by αB-crystallin overexpression is too simplistic a goal as a strategy to prevent AxD. Indeed aggregate formation could be seen as a protective mechanism [63] and in AxD, mutant protein is found not only in aggregates but also in filaments too [32]. It is clear that αB-crystallin expression in astrocytes can positively influence survival in a mouse model of AxD [64]. The association of αB-crystallin with Rosenthal fibers is also a key histopathological feature [5–9,65], but itisnot yet clear how its association with GFAP filaments and their aggregates might prevent morbidity [64].

Recent studies have shown that αB-crystallin can protect cells from apoptosis by downregulating caspase-3 expression [66], or by inhibiting its activation [67]. In a recently published Drosophila model of AxD [65], the expression of R79H GFAP was correlated with a significant increase in TUNEL-positive glial and neuronal cells. Our data presented here show for the first time that the expression of a GFAP mutant (D417M14X) coincided with the increased activation of caspase 3 and a decrease in astrocyte viability. Perhaps our success in detecting a loss in cell viability where others have failed [43] might be related to the transient transfection strategy we have employed. Nevertheless, GFAP is itself a caspase substrate, detected within damaged astrocytes of Alzheimer’s disease-damaged brains [46]. In a retinal detachment model, the removal of GFAP and vimentin from the Müller glia reduced photoreceptor cell death [68] clearly implicating the astrocyte IF network in propagating signals that are key to neuronal death. The recent analysis of some of the original murine model of AxD [69] now reveals altered metabolic functions for both astrocytes and neurons as well as a decrease in the transfer of glutamine from astrocytes to neurons. These observations coupled to the fact that caspase activation may be related to alterations in astrocyte function that can be independent of cell death [46,70,71] implicate caspase activation as a result of altered GFAP function as a key part of the pathophysiology of AxD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J. T. Rutka (Division of Neurosurgery, University of Toronto, Canada) for U343MG cell line; Dr. Elly M. Hol (Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience, The Netherlands) for anti-GFAPδ antibody, and Dr. R. M. Evans (University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver) for SW13/cl.1 and SW13/cl.2. This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (P01NS42803 to RAQ and MDP) and the National Science Council grant (98-2311-B-007-001-MY2).

Abbreviations

- IF

intermediate filament

- SHSPS

small heat shock proteins

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- ULF

unit length filament

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

Supplementary materials related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.06.017.

References

- 1.Russo LS, Jr, Aron A, Anderson PJ. Alexander’s disease: a report and reappraisal. Neurology. 1976;26:607–614. doi: 10.1212/wnl.26.7.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodriguez D, Gauthier F, Bertini E, Bugiani M, Brenner M, N’Guyen S, Goizet C, Gelot A, Surtees R, Pedespan JM, Hernandorena X, Troncoso M, Uziel G, Messing A, Ponsot G, Pham-Dinh D, Dautigny A, Boespflug-Tanguy O. Infantile Alexander disease: spectrum of GFAP mutations and genotype–phenotype correlation. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:1134–1140. doi: 10.1086/323799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Knaap MS, Ramesh V, Schiffmann R, Blaser S, Kyllerman M, Gholkar A, Ellison DW, van der Voorn JP, van Dooren SJ, Jakobs C, Barkhof F, Salomons GS. Alexander disease: ventricular garlands and abnormalities of the medulla and spinal cord. Neurology. 2006;66:494–498. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000198770.80743.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barkovich AJ, Messing A. Alexander disease: not just a leukodystrophy anymore. Neurology. 2006;66:468–469. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000200905.43191.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomokane N, Iwaki T, Tateishi J, Iwaki A, Goldman JE. Rosenthal fibers share epitopes with alpha B-crystallin, glial fibrillary acidic protein, and ubiquitin, but not with vimentin. Immunoelectron microscopy with colloidal gold. Am J Pathol. 1991;138:875–885. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwaki T, Kume-Iwaki A, Liem RK, Goldman JE. Alpha B-crystallin is expressed in non-lenticular tissues and accumulates in Alexander’s disease brain. Cell. 1989;57:71–78. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Head MW, Corbin E, Goldman JE. Overexpression and abnormal modification of the stress proteins alpha B-crystallin and HSP27 in Alexander disease. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:1743–1753. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eng LF, Lee YL, Kwan H, Brenner M, Messing A. Astrocytes cultured from transgenic mice carrying the added human glial fibrillary acidic protein gene contain Rosenthal fibers. J Neurosci Res. 1998;53:353–360. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980801)53:3<353::AID-JNR9>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Messing A, Head MW, Galles K, Galbreath EJ, Goldman JE, Brenner M. Fatal encephalopathy with astrocyte inclusions in GFAP transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:391–398. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brenner M, Johnson AB, Boespflug-Tanguy O, Rodriguez D, Goldman JE, Messing A. Mutations in GFAP, encoding glial fibrillary acidic protein, are associated with Alexander disease. Nat Genet. 2001;27:117–120. doi: 10.1038/83679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li R, Johnson AB, Salomons G, Goldman JE, Naidu S, Quinlan R, Cree B, Ruyle SZ, Banwell B, D’Hooghe M, Siebert JR, Rolf CM, Cox H, Reddy A, Gutierrez-Solana LG, Collins A, Weller RO, Messing A, van der Knaap MS, Brenner M. Glial fibrillary acidic protein mutations in infantile, juvenile, and adult forms of Alexander disease. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:310–326. doi: 10.1002/ana.20406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murakami N, Tsuchiya T, Kanazawa N, Tsujino S, Nagai T. Novel deletion mutation in GFAP gene in an infantile form of Alexander disease, Pediatr. Neurol. 2008;38:50–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrmann H, Aebi U. Intermediate filaments and their associates: multi-talented structural elements specifying cytoarchitecture and cytodynamics. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:79–90. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herrmann H, Aebi U. Intermediate filaments: molecular structure, assembly mechanism, and integration into functionally distinct intracellular Scaffolds. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:749–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parry DA. Microdissection of the sequence and structure of intermediate filament chains. Adv Protein Chem. 2005;70:113–142. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)70005-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Omary MB, Coulombe PA, McLean WH. Intermediate filament proteins and their associated diseases. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2087–2100. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLean WH, Smith FJ, Cassidy AJ. Insights into genotype–phenotype correlation in pachyonychia congenita from the human intermediate filament mutation database. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10:31–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2005.10205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicolet S, Herrmann H, Aebi U, Strelkov SV. Atomic structure of vimentin coil 2. J Struct Biol. 2010;170:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strelkov SV, Herrmann H, Geisler N, Wedig T, Zimbelmann R, Aebi U, Burkhard P. Conserved segments 1A and 2B of the intermediate filament dimer: their atomic structures and role in filament assembly. EMBO J. 2002;21:1255–1266. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.6.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu KC, Bryan JT, Morasso MI, Jang SI, Lee JH, Yang JM, Marekov LN, Parry DA, Steinert PM. Coiled-coil trigger motifs in the 1B and 2B rod domain segments are required for the stability of keratin intermediate filaments. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3539–3558. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.10.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamada S, Wirtz D, Coulombe PA. Pairwise assembly determines the intrinsic potential for self-organization and mechanical properties of keratin filaments. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:382–391. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-10-0522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernot KM, Lee CH, Coulombe PA. A small surface hydrophobic stripe in the coiled-coil domain of type I keratins mediates tetramer stability. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:965–974. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parry DA, Strelkov SV, Burkhard P, Aebi U, Herrmann H. Towards a molecular description of intermediate filament structure and assembly. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2204–2216. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen WJ, Liem RK. The endless story of the glial fibrillary acidic protein. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:2299–2311. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.8.2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quinlan RA, Moir RD, Stewart M. Expression in Escherichia coli of fragments of glial fibrillary acidic protein: characterization, assembly properties and paracrystal formation. J Cell Sci. 1989;93:71–83. doi: 10.1242/jcs.93.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caceres-Marzal C, Vaquerizo J, Galan E, Fernandez S. Early mitochondrial dysfunction in an infant with Alexander disease. Pediatr Neurol. 2006;35:293–296. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pareyson D, Fancellu R, Mariotti C, Romano S, Salmaggi A, Carella F, Girotti F, Gattellaro G, Carriero MR, Farina L, Ceccherini I, Savoiardo M. Adult-onset Alexander disease: a series of eleven unrelated cases with review of the literature. Brain. 2008;131:2321–2331. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farina L, Pareyson D, Minati L, Ceccherini I, Chiapparini L, Romano S, Gambaro P, Fancellu R, Savoiardo M. Can MR imaging diagnose adult-onset Alexander disease? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1190–1196. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salmaggi A, Botturi A, Lamperti E, Grisoli M, Fischetto R, Ceccherini I, Caroli F, Boiardi A. A novel mutation in the GFAP gene in a familial adult onset Alexander disease. J Neurol. 2007;254:1278–1280. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0361-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sueda Y, Takahashi T, Ochi K, Ohtsuki T, Namekawa M, Kohriyama T, Takiyama Y, Matsumoto M. Adult onset Alexander disease with a novel variant (S398F) in the glial fibrillary acidic protein gene. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2009;49:358–363. doi: 10.5692/clinicalneurol.49.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quinlan RA, Brenner M, Goldman JE, Messing A. GFAP and its role in Alexander disease. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2077–2087. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perng M, Su M, Wen SF, Li R, Gibbon T, Prescott AR, Brenner M, Quinlan RA. The Alexander disease-causing glial fibrillary acidic protein mutant, R416W, accumulates into Rosenthal fibers by a pathway that involves filament aggregation and the association of alpha B-crystallin and HSP27. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:197–213. doi: 10.1086/504411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perng MD, Wen SF, Gibbon T, Middeldorp J, Sluijs J, Hol EM, Quinlan RA. Glial fibrillary acidic protein filaments can tolerate the incorporation of assembly-compromised GFAP-delta, but with consequences for filament organization and alphaB-crystallin association. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4521–4533. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-03-0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perng MD, Sandilands A, Kuszak J, Dahm R, Wegener A, Prescott AR, Quinlan RA. The intermediate filament systems in the eye lens. Methods Cell Biol. 2004;78:597–624. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(04)78021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nicholl ID, Quinlan RA. Chaperone activity of alpha-crystallins modulates intermediate filament assembly. EMBO J. 1994;13:945–953. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sawada K, Agata K, Yoshiki A, Eguchi G. A set of anti-crystallin monoclonal antibodies for detecting lens specificities: beta-crystallin as a specific marker for detecting lentoidogenesis in cultures of chicken lens epithelial cells. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1993;37:355–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandilands A, Prescott AR, Carter JM, Hutcheson AM, Quinlan RA, Richards J, FitzGerald PG. Vimentin and CP49/filensin form distinct networks in the lens which are independently modulated during lens fibre cell differentiation. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:1397–1406. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.4.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berridge MV, Tan AS. Characterization of the cellular reduction of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT): subcellular localization, substrate dependence, and involvement of mitochondrial electron transport in MTT reduction. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;303:474–482. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pollard TD, Cooper JA. Methods to characterize actin filament networks. Methods Enzymol. 1982;85(Pt. B):211–233. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(82)85022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roelofs RF, Fischer DF, Houtman SH, Sluijs JA, Van Haren W, Van Leeuwen FW, Hol EM. Adult human subventricular, subgranular, and subpial zones contain astrocytes with a specialized intermediate filament cytoskeleton. Glia. 2005;52:289–300. doi: 10.1002/glia.20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hedberg KK, Chen LB. Absence of intermediate filaments in a human adrenal cortex carcinoma-derived cell line. Exp Cell Res. 1986;163:509–517. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(86)90081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eliasson C, Sahlgren C, Berthold CH, Stakeberg J, Celis JE, Betsholtz C, Eriksson JE, Pekny M. Intermediate filament protein partnership in astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23996–24006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.23996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang G, Xu Z, Goldman JE. Synergistic effects of the SAPK/JNK and the proteasome pathway on glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) accumulation in Alexander disease. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38634–38643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang G, Yue Z, Talloczy Z, Hagemann T, Cho W, Messing A, Sulzer DL, Goldman JE. Autophagy induced by Alexander disease-mutant GFAP accumulation is regulated by p38/MAPK and mTOR signaling pathways. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1540–1555. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diehl JA, Zindy F, Sherr CJ. Inhibition of cyclin D1 phosphorylation on threonine-286 prevents its rapid degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Genes Dev. 1997;11:957–972. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.8.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mouser PE, Head E, Ha KH, Rohn TT. Caspase-mediated cleavage of glial fibrillary acidic protein within degenerating astrocytes of the Alzheimer’s disease brain. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:936–946. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bar H, Goudeau B, Walde S, Casteras-Simon M, Mucke N, Shatunov A, Goldberg YP, Clarke C, Holton JL, Eymard B, Katus HA, Fardeau M, Goldfarb L, Vicart P, Herrmann H. Conspicuous involvement of desmin tail mutations in diverse cardiac and skeletal myopathies. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:374–386. doi: 10.1002/humu.20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bar H, Schopferer M, Sharma S, Hochstein B, Mucke N, Herrmann H, Willenbacher N. Mutations in desmin’s carboxy-terminal “tail” domain severely modify filament and network mechanics. J Mol Biol. 2010;397:1188–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsujimura K, Tanaka J, Ando S, Matsuoka Y, Kusubata M, Sugiura H, Yamauchi T, Inagaki M. Identification of phosphorylation sites on glial fibrillary acidic protein for cdc2 kinase and Ca(2+)-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Biochem. 1994;116:426–434. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hsiao VC, Tian R, Long H, Der Perng M, Brenner M, Quinlan RA, Goldman JE. Alexander-disease mutation of GFAP causes filament disorganization and decreased solubility of GFAP. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2057–2065. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blechingberg J, Holm IE, Nielsen KB, Jensen TH, Jorgensen AL, Nielsen AL. Identification and characterization of GFAPkappa, a novel glial fibrillary acidic protein isoform. Glia. 2007;55:497–507. doi: 10.1002/glia.20475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van den Berge SA, Middeldorp J, Zhang CE, Curtis MA, Leonard BW, Mastroeni D, Voorn P, van de Berg WD, Huitinga I, Hol EM. Longterm quiescent cells in the aged human subventricular neurogenic system specifically express GFAP-delta. Aging Cell. 2010;9:313–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mignot C, Boespflug-Tanguy O, Gelot A, Dautigny A, Pham-Dinh D, Rodriguez D. Alexander disease: putative mechanisms of an astrocytic encephalopathy. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:369–385. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3143-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cho W, Messing A. Properties of astrocytes cultured from GFAP over-expressing and GFAP mutant mice. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:1260–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mignot C, Delarasse C, Escaich S, Della Gaspera B, Noe E, Colucci-Guyon E, Babinet C, Pekny M, Vicart P, Boespflug-Tanguy O, Dautigny A, Rodriguez D, Pham-Dinh D. Dynamics of mutated GFAP aggregates revealed by real-time imaging of an astrocyte model of Alexander disease. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2766–2779. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brenner M, Goldman JE, Quinlan RA, Messing A. Alexander disease: a genetic disorder of astrocytes. In: Parpura VH, Haydon PG, editors. Astrocytes in Pathophysiology of the Nervous System. Springer; Boston, Massachusetts, USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kamradt MC, Chen F, Cryns VL. The small heat shock protein alpha B-crystallin negatively regulates cytochrome c- and caspase-8-dependent activation of caspase-3 by inhibiting its autoproteolytic maturation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16059–16063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mao YW, Liu JP, Xiang H, Li DW. Human alphaA- and alphaB-crystallins bind to Bax and Bcl-X(S) to sequester their translocation during staurosporine-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:512–526. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li DW, Liu JP, Mao YW, Xiang H, Wang J, Ma WY, Dong Z, Pike HM, Brown RE, Reed JC. Calcium-activated RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathway mediates p53-dependent apoptosis and is abrogated by alpha B-crystallin through inhibition of RAS activation. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4437–4453. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Perng MD, Cairns L, van den IP, Prescott A, Hutcheson AM, Quinlan RA. Intermediate filament interactions can be altered by HSP27 and alphaB-crystallin. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2099–2112. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.13.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perng MD, Wen SF, van den IP, Prescott AR, Quinlan RA. Desmin aggregate formation by R120G alphaB-crystallin is caused by altered filament interactions and is dependent upon network status in cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:2335–2346. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-12-0893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koyama Y, Goldman JE. Formation of GFAP cytoplasmic inclusions in astrocytes and their disaggregation by alphaB-crystallin. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1563–1572. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65409-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schietke R, Brohl D, Wedig T, Mucke N, Herrmann H, Magin TM. Mutations in vimentin disrupt the cytoskeleton in fibroblasts and delay execution of apoptosis. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hagemann TL, Boelens WC, Wawrousek EF, Messing A. Suppression of GFAP toxicity by alphaB-crystallin in mouse models of Alexander disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1190–1199. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang L, Colodner KJ, Feany MB. Protein misfolding and oxidative stress promote glial-mediated neurodegeneration in an Alexander disease model. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2868–2877. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3410-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li DW, Xiang H, Mao YW, Wang J, Fass U, Zhang XY, Xu C. Caspase-3 is actively involved in okadaic acid-induced lens epithelial cell apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 2001;266:279–291. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ousman SS, Tomooka BH, van Noort JM, Wawrousek EF, O’Connor KC, Hafler DA, Sobel RA, Robinson WH, Steinman L. Protective and therapeutic role for alphaB-crystallinin autoimmune demyelination. Nature. 2007;448:474–479. doi: 10.1038/nature05935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakazawa T, Takeda M, Lewis GP, Cho KS, Jiao J, Wilhelmsson U, Fisher SK, Pekny M, Chen DF, Miller JW. Attenuated glial reactions and photoreceptor degeneration after retinal detachment in mice deficient in glial fibrillary acidic protein and vimentin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:2760–2768. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Meisingset TW, Risa O, Brenner M, Messing A, Sonnewald U. Alteration of glial–neuronal metabolic interactions in a mouse model of Alexander disease. Glia. 2010;58:1228–1234. doi: 10.1002/glia.21003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wagner DC, Riegelsberger UM, Michalk S, Hartig W, Kranz A, Boltze J. Cleaved caspase-3 expression after experimental stroke exhibits different phenotypes and is predominantly non-apoptotic. Brain Res. 2011;1381:237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Acarin L, Villapol S, Faiz M, Rohn TT, Castellano B, Gonzalez B. Caspase-3 activation in astrocytes following postnatal excitotoxic damage correlates with cytoskeletal remodeling but not with cell death or proliferation. Glia. 2007;55:954–965. doi: 10.1002/glia.20518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.