Abstract

Background

Botrytis cinerea Pers. Fr. is an important pathogen causing stem rot in tomatoes grown indoors for extended periods. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have been reported as gene expression regulators related to several stress responses and B. cinerea infection in tomato. However, the function of miRNAs in the resistance to B. cinerea remains unclear.

Results

The miRNA expression patterns in tomato in response to B. cinerea stress were investigated by high-throughput sequencing. In total, 143 known miRNAs and seven novel miRNAs were identified and their corresponding expression was detected in mock- and B. cinerea-inoculated leaves. Among those, one novel and 57 known miRNAs were differentially expressed in B. cinerea-infected leaves, and 8 of these were further confirmed by quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR). Moreover, five of these eight differentially expressed miRNAs could hit 10 coding sequences (CDSs) via CleaveLand pipeline and psRNAtarget program. In addition, qRT-PCR revealed that four targets were negatively correlated with their corresponding miRNAs (miR319, miR394, and miRn1).

Conclusion

Results of sRNA high-throughput sequencing revealed that the upregulation of miRNAs may be implicated in the mechanism by which tomato respond to B. cinerea stress. Analysis of the expression profiles of B. cinerea-responsive miRNAs and their targets strongly suggested that miR319, miR394, and miRn1 may be involved in the tomato leaves’ response to B. cinerea infection.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12870-014-0410-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Tomato, High-throughput sequencing, B. cinerea-responsive miRNA, Target expression

Background

Botrytis cinerea, a necrotrophic fungus causing gray mold disease, caused by Botrytis cinerea is considered an important pathogen around throughout the world. It induces decay on in a large number of economically important fruits and vegetables during the growing season and during postharvest storage. It is also a majorcreating serious obstacle problem to in long- distance transport and storage [1]. B. cinerea infection leads to annual losses of 10 to 100 billion US dollars worldwide [2]. Necrotrophs kill their host cells by secreting toxic compounds or lytic enzymes; they also produce an array of pathogenic factors that can subdue host defenses [3,4]. To limit the spread of pathogens, host cells generate signaling molecules to initiate defense mechanisms in the surrounding cells. Abscisic acid and ethylene are plant hormones that participate in this process [5-7]. Li et al. [8] have found that SlMKK2 and SlMKK4 contribute to the resistance to B. cinerea in tomato. However, despite extensive research efforts, the biochemical and genetic basis of plant resistance to B. cinerea remains poorly understood.

sRNAs are non-coding small RNAs (sRNAs), approximately 21–24 nt in length. These RNAs induce gene silencing by binding to Argonaute (AGO) proteins and directing the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to the genes with complementary sequences. The plant miRNAs are a well-studied class of sRNAs; they are hypersensitive to abiotic or biotic stresses and various physiological processes [9,10]. miR393 participates in bacterial PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI) by repressing auxin signaling [11]. In Arabidopsis plants treated with flg22, miR393 transcription is induced and the mRNAs of miR393 targets, including three F-box auxin receptors, namely transport inhibitor response 1 (TIR1), auxin signaling F-Box protein 2 (AFB2), and AFB3, are downregulated. Consequently, the resistance to Pseudomonas syringae, a bacterial plant pathogen, is increased [11]. miRNAs are also directly involved in the regulation of disease resistance (R) genes [12-14]. For example, nta-miR6019 and nta-miR6020 are implicated in the regulation of disease resistance in Nicotiana benthamiana by controlling the expression of the N gene. This gene encodes a Toll and Interleukin-1 Receptor type of nucleotide binding site-leucine-rich-repeat receptor protein that provides resistance to the tobacco mosaic virus [14,15]. The members of different R-gene families in tomato, potato, soybean, and Medicago truncatula are targeted by miR482 and miR2118 miRNAs [12,13]. In addition, pathogen sRNA can also suppress the host immunity by loading into AGO1 and cause enhanced susceptibility to B. cinerea [2].

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum, 2n = 24), a widespread member of the Solanum species, is an economically important vegetable crop worldwide. Several miRNAs can respond to B. cinerea infection in tomato [16]. To investigate the function of miRNAs in the resistance to this pathogen, we constructed two sRNA libraries from mock- and B. cinerea-inoculated tomato leaves. These libraries were then sequenced using an Illumina Solexa system. This study was conducted to identify and validate B. cinerea-responsive miRNAs from tomato leaves. The outcome of this study could enhance our understanding of the miRNA-mediated regulatory networks that respond to fungal infection in tomato; it could also provide new gene resources to develop resistant breeds.

Results

Deep sequencing of sRNAs in tomato

To identify miRNAs that respond to B. cinerea infection, two sRNA libraries were constructed from B. cinerea-inoculated (TD7d) and mock-inoculated (TC7d) tomato leaves at 7 days post-inoculation (dpi). The libraries were sequenced using an Illumina Solexa analyzer in Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI; China) and the sequences have been deposited in the NCBI Short Read Archive (SRA) with the accession number SRP043615. We generated 33.31 million raw reads from the two sRNA libraries. After removing low-quality tags and adaptor contaminations, we obtained 16,844,708 (representing 6,075,098 unique sequences) and 13,935,908 (representing 4,807,933 unique sequences) clean reads, ranging from 18 nt to 30 nt, from TC7d and TD7d libraries, respectively (Table 1). Most reads (>86% of redundant reads and >77% of unique reads) had at least 1 perfect match with the tomato genome (Table 1).

Table 1.

Statistics of the Illumina sequencing of two small RNA libraries including Botrytis cinerea infection and control samples

| Read data | TC7d* | TD7d* |

|---|---|---|

| Raw reads | 18158256 | 15153960 |

| Reads of appropriate size (18–30 nt) | 16844708 | 13935908 |

| Unique reads of appropriate size | 6075098 | 4807933 |

| Percentage of total reads mapping to S.lycopersicum sl2.40 (100% identity) | 87.65% | 86.86% |

| Percentage of unique reads mapping to S.lycopersicum sl2.40 (100% identity) | 78.66% | 77.61% |

*TC7d, Mock-inoculated leaves at 7 dpi; TD7d, B.cinerea-inoculated leaves at 7 dpi.

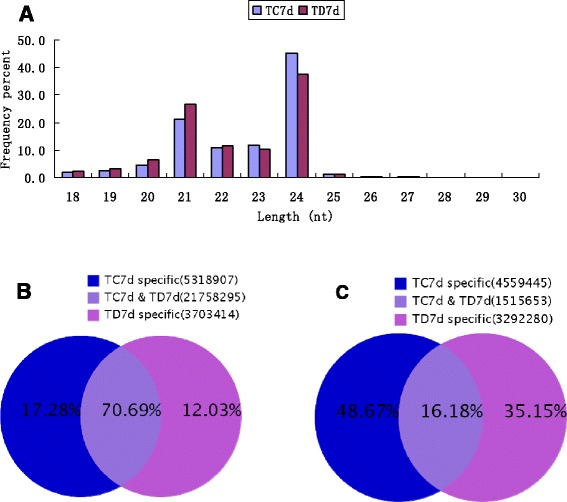

The majority of sRNA reads were from 20 nt- to 24 nt-long. Sequences with 21-nt and 24-nt lengths were dominant in both libraries (Figure 1A). The most abundant sRNAs were 24 nt in length, accounting for 45.15% (TC7d) and 37.65% (TD7d) of the total sequence reads. Our results are consistent with those of previous studies using other plant species such as Arabidopsis [17], Oryza [18], Medicago [19,20], and Populus [21]. Moreover, the ratios of the tags differed significantly between the two libraries. The relative abundances of 24-nt sRNAs in the TD7d library were markedly lower than those in the TC7d library; this result suggested that the 24-nt sRNA classes are repressed by B. cinerea infection. Nevertheless, the abundance of 21-nt miRNAs was evidently higher in the TD7d library than in the TC7d library, suggesting that the 21-nt miRNA classes are implicated in the response to B. cinerea infection. The proportions of common and specific sRNAs in both the libraries were further analyzed. Among the analyzed sRNAs, 70.69% sRNAs common to both libraries; 17.28% and 12.03% were specific to TC7d and TD7d libraries, respectively (Figure 1B). However, opposite results were obtained for unique sRNAs; in particular, the proportions of specific sequences were larger than those of common sequences. Only 16.18% was common to both the libraries; moreover, 48.67% and 35.15% were specific to TC7d and TD7d libraries, respectively (Figure 1C). These results suggested that the expression of unique sRNAs was altered by B. cinerea infection.

Figure 1.

Size distribution of small RNAs in Mock-inoculated (TC7d) and B.cinerea-inoculated (TD7d) libraries from tomato leaves (A), and Venn diagrams for analysis of total (B) and unique (C) sRNAs between TC7d and TD7d libraries.

Identification of known miRNA families in tomato

Based on unique sRNA sequences mapped to miRBase, release 20.0 [22], with perfect matches and a minimum of 10 read counts, we identified 123 unique sequences belonging to 23 conserved miRNA families in TC7d and TD7d libraries, with total abundances of 90,472 and 137,058 reads per million (RPM), respectively (Table 2). Among the conserved miRNA families, 3 families (miR156, miR166, and miR172) consisted of more than 10 members. In contrast, miR165, miR393, miR394, miR395, and miR477 contained only one member each. Moreover, 20 unique sequences from the 17 non-conserved miRNA families (i.e., conserved only in a few plant species [23]) were detected in TC7d and TD7d libraries. For instance, miR894 has been found only in Physcomitrella patens [24]. The majority of non-conserved miRNA families had only one member each; three miRNA families (miR827, miR1919, and miR4376) contained two members (Table 2) each.

Table 2.

Known miRNA families and their transcript abundance identified from TC7d and TD7d libraries in tomato

| conserved miRNA family | No. of members | miRNA reads count (RPM) | Log2 (TD7d/TC7dC) | P-value | Significance (Up/Down) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC7d | TD7d | |||||

| Conserved miRNA family | ||||||

| miR156 | 25 | 39076 | 85295 | 1.13 | 0.0000 | ** (Up) |

| miR157 | 2 | 481 | 865 | 0.85 | 0.0000 | |

| miR159 | 2 | 128 | 331 | 1.37 | 0.00 | ** (Up) |

| miR160 | 2 | 13 | 19 | 0.59 | 0.0000 | |

| miR162 | 3 | 491 | 527 | 0.10 | 0.0000 | |

| miR164 | 3 | 100 | 184 | 0.88 | 0.0000 | |

| miR165 | 1 | 7 | 6 | −0.07 | 0.7470 | |

| miR166 | 19 | 28611 | 21493 | −0.41 | 0.0000 | |

| miR167 | 7 | 7843 | 8977 | 0.19 | 0.0000 | |

| miR168 | 7 | 11938 | 17420 | 0.55 | 0.0000 | |

| miR169 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 0.71 | 0.0016 | |

| miR170 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.12 | 0.7557 | |

| miR171 | 8 | 103 | 83 | −0.32 | 0.0000 | |

| miR172 | 10 | 890 | 772 | −0.20 | 0.0000 | |

| miR319 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 2.33 | 0.0000 | ** (Up) |

| miR390 | 4 | 476 | 607 | 0.35 | 0.0000 | |

| miR393 | 1 | 28 | 30 | 0.14 | 0.1483 | |

| miR394 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2.23 | 0.0000 | ** (Up) |

| miR395 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0.70 | 0.0585 | |

| miR396 | 6 | 147 | 172 | 0.23 | 0.0000 | |

| miR399 | 5 | 12 | 14 | 0.15 | 0.2994 | |

| miR477 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.27 | 0.4504 | |

| miR482 | 6 | 115 | 235 | 1.03 | 0.0000 | ** (Up) |

| Non-conserved miRNA family | ||||||

| miR827 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.01 | 0.9654 | |

| miR894 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.35 | 0.4469 | |

| miR1446 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 7.85 | 0.0000 | ** (Up) |

| miR1511 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.91 | 0.1035 | |

| miR1919 | 2 | 86 | 153 | 0.83 | 0.0000 | |

| miR2111 | 1 | 1 | 0 | −6.57 | 0.0001 | ** (Down) |

| miR4376 | 2 | 180 | 187 | 0.06 | 0.1292 | |

| miR5300 | 1 | 515 | 1401 | 1.44 | 0.0000 | ** (Up) |

| miR5301 | 1 | 54 | 103 | 0.93 | 0.0000 | |

| miR5304 | 1 | 7 | 13 | 0.81 | 0.0000 | |

| miR6022 | 1 | 975 | 1317 | 0.43 | 0.0000 | |

| miR6023 | 1 | 89 | 101 | 0.17 | 0.0015 | |

| miR6024 | 1 | 56 | 103 | 0.89 | 0.0000 | |

| miR6026 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.52 | 0.1671 | |

| miR6027 | 1 | 3750 | 3211 | −0.22 | 0.0000 | |

| miR6300 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1.60 | 0.0002 | ** (Up) |

| miR7122 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.07 | 0.0488 | |

**Significant difference; Up, Up-regulation; Down, Down-regulation.

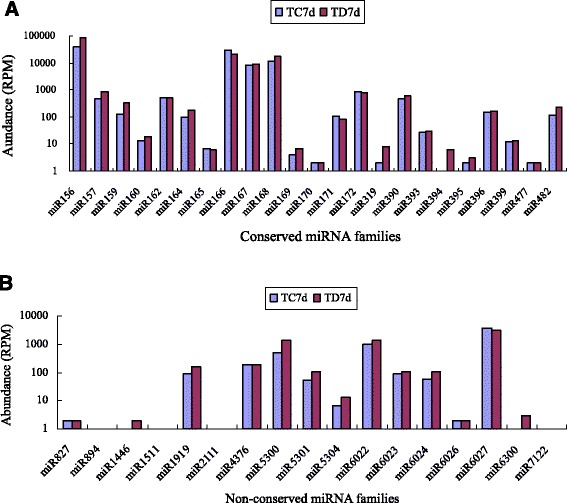

Read counts differed drastically among the 23 known miRNA families. A few conserved miRNA families such as miR156, miR166, and miR168 showed high expression levels (more than 10,000 RPM) in both the libraries. The most abundantly expressed miRNA family was miR156 with 39,076 (TC7d) and 85,295 (TD7d) RPM, accounting for 43.2% and 62.2% of all the conserved miRNA reads, respectively. miR166 was the second most abundant miRNA family in both the libraries. Several miRNA families, including miR157, miR159, miR162, miR164, miR167, miR171, miR172, miR390, miR396, and miR482, were moderately abundant (Figure 2A). Nevertheless, the most non-conserved miRNA families such as miR827, miR894, and miR1446 showed relatively low expression levels (less than10 RPM) in TC7d and TD7d libraries (Figure 2B). Moreover, different members of the same miRNA family displayed significantly different expression levels (Additional file 1: Table S1). For instance, the abundance of miR156 members varied from 0 to 923,832 reads. These results demonstrated that the expression levels of conserved and non-conserved miRNAs varied dramatically in tomato. The results were consistent with those of previous studies, which showed that non-conserved miRNAs have lower expression levels than conserved miRNAs [25-27].

Figure 2.

Reads abundance of conserved miRNA (A) and non-conserved miRNA (B) families in TC7d and TD7d library.

Identification of novel miRNA in tomato

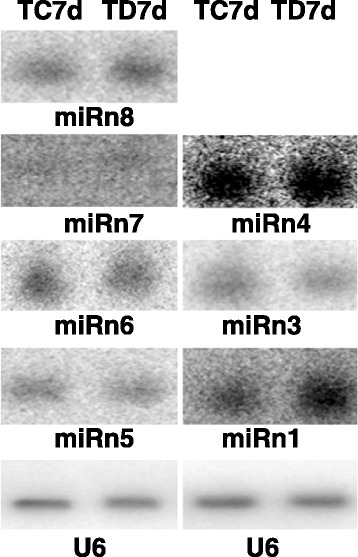

To search for novel miRNAs, we excluded sRNA reads homologous to known miRNAs and other non-coding sRNAs (Rfam 10) and analyzed the secondary structures of the precursors of the remaining 20-nt to 22-nt sRNAs using RNAfold program. The precursors with canonical stem–loop structures were further analyzed using a series of stringent filter strategies to ensure that they satisfied the common criteria established by the research community [28,29]. We obtained 31 miRNA candidates derived from 33 loci, which satisfied the screening criteria. Among those candidates, seven contained miRNA-star (miRNA*) sequences identified from the same libraries; 24 candidates did not contain any identified miRNA* (Additional file 2: Table S2). We considered the seven candidates with miRNA* sequences to be novel tomato miRNAs and the 24 remaining candidates without miRNA* sequences to be potential tomato miRNAs. The secondary structures and sRNA mapping information of the seven novel miRNA precursors are shown in Additional file 3: Figure S1. Gel blot analysis was performed to validate the seven miRNAs and determine their expression patterns. miRn7 had no signal; this was possibly caused by a very low expression in tomato leaves or false-positive results in sRNA sequencing. The six remaining candidates were identified as miRNAs expressed in tomato leaves (Figure 3). In agreement with the sRNA sequencing data, gel blot results showed that miRn1 was upregulated in B. cinerea-infected leaves.

Figure 3.

Validation of novel miRNAs by northern blotting. RNA gel blots of total RNA isolated from leaves of mock- (TC7d) and B.cinerea-inoculated (TD7d) leaves were probed with labeled oligonucleotides. The U6 RNA was used as internal control.

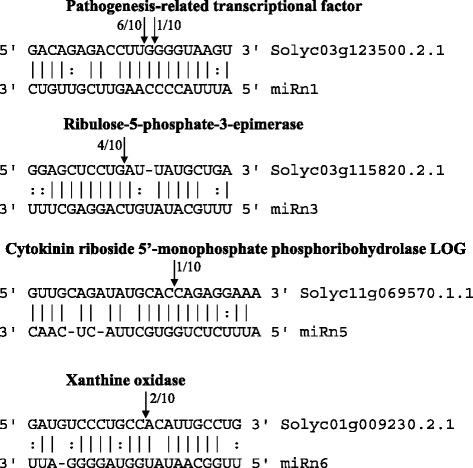

To validate and functionally identify these six miRNAs, cleaved targets were detected using CleaveLand pipeline. Abundance of the sequences was plotted for each transcript (Additional file 4: Figure S2). We found 26 cDNA targets for five miRNAs (miRn1, miRn3, miRn4-2, miRn5, and miRn6) but none for miRn8. There were 2, 10, 9, and 5 targets in categories 0, 2, 3, and 4, respectively (Table 3). These findings further validated miRn1, miRn3, miRn4-1, miRn5, and miRn6 as novel miRNAs expressed in tomato leaves. miRn1 may target the pathogenesis-related transcriptional factor, indicating that it may be a B. cinerea-responsive miRNA. In addition, a total of 10 targets (Solyc03g123500.2.1 and Solyc06g063070.2.1, targeted by miRn1; Solyc03g115820.2.1 and Solyc07g017500.2.1, targeted by miRn3; Solyc04g054480.2.1 and Solyc10g005730.2.1, targeted by miR4-2; Solyc11g069570.1.1 and Solyc12g056800.1.1, targeted by miR5; and Solyc01g009230.2.1 and Solyc06g050650.1.1, targeted by miRn6) were selected for cleavage analysis through 5′ RLM-RACE (5′ RNA ligase mediated rapid amplification of cDNA ends). The results showed that pathogenesis-related transcriptional factor (Solyc03g123500.2.1), Ribulose-5-phosphate-3-epimerase (Solyc03g115820.2.1), Cytokinin riboside 5′-monophosphate phosphoribohydrolase LOG (Solyc11g069570.1.1) and Xanthine oxidase (Solyc01g009230.2.1) were targeted by miRn1, miRn3, miRn5 and miRn6, respectively (Figure 4). The cleavage sites were not found at the expected positions in the seven remaining targets. These results indicated that the four novel miRNAs (miRn1, miRn3, miRn5 and miRn6) would cleave the targets to regulate their expression.

Table 3.

Sliced targets were identified using CleaveLand pipline

| miRNA name | Target | Cleave site | category | Target annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRn1 | Solyc03g121180.2.1 | 816 | 3 | GDSL esterase/lipase At5g22810 |

| miRn1 | Solyc03g123500.2.1 | 370 | 4 | Pathogenesis-related transcriptional factor and ERF, DNA-binding |

| miRn1 | Solyc04g017620.2.1 | 363 | 3 | Phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase 9 |

| miRn1 | Solyc06g063070.2.1 | 447 | 3 | Pathogenesis-related transcriptional factor and ERF, DNA-binding |

| miRn1 | Solyc09g008480.2.1 | 2181 | 2 | Phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase 9 |

| miRn3 | Solyc01g067070.2.1 | 959 | 3 | Mitochondrial deoxynucleotide carrier |

| miRn3 | Solyc01g111600.2.1 | 494 | 3 | Metal ion binding protein |

| miRn3 | Solyc03g115820.2.1 | 1115 | 2 | Ribulose-5-phosphate-3-epimerase |

| miRn3 | Solyc03g118020.2.1 | 2483 | 2 | RNA-induced silencing complex |

| miRn3 | Solyc06g008110.2.1 | 1236 | 2 | WD repeat-containing protein |

| miRn3 | Solyc06g074720.2.1 | 324 | 4 | MKI67 FHA domain-interacting nucleolar phosphoprotein-like |

| miRn3 | Solyc07g017500.2.1 | 1272 | 0 | Lateral signaling target protein 2 homolog |

| miRn3 | Solyc07g047670.2.1 | 1347 | 2 | Pescadillo homolog 1 |

| miRn3 | Solyc07g066650.2.1 | 887 | 3 | DCN1-like protein 2, Defective in cullin neddylation |

| miRn3 | Solyc10g076250.1.1 | 948 | 2 | Aminotransferase like protein |

| miRn3 | Solyc11g006680.1.1 | 2199 | 2 | Pentatricopeptide repeat-containing protein |

| miRn4-2 | Solyc04g054480.2.1 | 4328 | 4 | C2 domain-containing protein-like |

| miRn4-2 | Solyc10g005730.2.1 | 849 | 4 | WD-40 repeat family protein |

| miRn5 | Solyc11g069570.1.1 | 306 | 3 | Cytokinin riboside 5'-monophosphate phosphoribohydrolase LOG |

| miRn5 | Solyc12g056800.1.1 | 575 | 2 | Oxidoreductase family protein |

| miRn6 | Solyc01g009230.2.1 | 4003 | 2 | Xanthine oxidase |

| miRn6 | Solyc02g072130.2.1 | 1191 | 3 | Protein transport protein SEC61 alpha subunit |

| miRn6 | Solyc05g015680.1.1 | 144 | 4 | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 7 long form |

| miRn6 | Solyc06g050650.1.1 | 489 | 3 | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 7 long form |

| miRn6 | Solyc06g084000.2.1 | 417 | 2 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K |

| miRn6 | Solyc07g042120.1.1 | 783 | 0 | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 7 long form |

| miR159 | Solyc01g009070.2.1 | 967 | 0 | MYB transcription factor |

| miR159 | Solyc05g053100.2.1 | 1088 | 4 | Dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase |

| miR159 | Solyc06g048730.2.1 | 1010 | 2 | Uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase |

| miR159 | Solyc06g073640.2.1 | 997 | 0 | MYB transcription factor |

| miR159 | Solyc10g083280.1.1 | 357 | 2 | evidence_code:10F0H1E1IEG 30S ribosomal protein S.1 |

| miR159 | Solyc12g014120.1.1 | 472 | 2 | evidence_code:10F0H0E1IEG Unknown Protein |

| miR160 | Solyc01g107510.2.1 | 1843 | 2 | DNA polymerase IV |

| miR160 | Solyc06g075150.2.1 | 1280 | 0 | Auxin response factor 16 |

| miR160 | Solyc09g007810.2.1 | 1364 | 4 | Auxin response factor 3 |

| miR160 | Solyc11g010790.1.1 | 855 | 3 | Glucosyltransferase |

| miR160 | Solyc11g010800.1.1 | 447 | 3 | Anthocyanidin 3-O-glucosyltransferase |

| miR160 | Solyc11g010810.1.1 | 855 | 4 | Glucosyltransferase |

| miR160 | Solyc11g013470.1.1 | 554 | 0 | Auxin response factor 17 (Fragment) |

| miR160 | Solyc11g069500.1.1 | 1313 | 0 | Auxin response factor 16 |

| miR169 | Solyc01g090420.2.1 | 1893 | 2 | Armadillo/beta-catenin repeat family protein |

| miR1919 | Solyc03g111340.2.1 | 1215 | 4 | Ubiquitin-like modifier-activating enzyme 5 |

| miR1919 | Solyc12g043020.1.1 | 1209 | 3 | evidence_code:10F0H1E1IEG Dihydroxy-acid dehydratase |

| miR319 | Solyc06g068010.2.1 | 702 | 2 | Biotin carboxyl carrier protein of acetyl-CoA carboxylase |

| miR319 | Solyc08g048370.2.1 | 763 | 3 | Transcription factor CYCLOIDEA (Fragment) |

| miR319 | Solyc08g048390.1.1 | 1025 | 2 | evidence_code:10F0H1E1IEG Transcription factor CYCLOIDEA (Fragment) |

| miR394 | Solyc01g109400.2.1 | 488 | 3 | Flavoprotein wrbA |

| miR394 | Solyc01g109660.2.1 | 298 | 2 | Glycine-rich RNA-binding protein |

| miR394 | Solyc05g015520.2.1 | 1162 | 2 | F-box family protein |

| miR394 | Solyc06g051750.2.1 | 1208 | 2 | Cytochrome P450″ |

| miR394 | Solyc06g082220.2.1 | 707 | 3 | Tat specific factor.1 |

| miR394 | Solyc12g044860.1.1 | 1328 | 2 | evidence_code:10F0H1E1IEG ATP dependent RNA helicase |

| miR5300 | Solyc08g068870.2.1 | 679 | 2 | Aspartic proteinase nepenthesin.1 |

| miR5300 | Solyc11g012970.1.1 | 265 | 2 | Aminoacylase.1 |

Figure 4.

Cleavage analysis of miRNA targets by 5′ RLM-RACE method. The identified cleavage sites are indicated by black arrows, and cleavage frequency is presented on top of the arrows.

Identification of B. cinerea-responsive miRNAs in tomato

To determine which of the known miRNAs respond to B. cinerea, we retrieved the read counts of the 143 unique sequences from 40 known miRNA families from both the libraries; we then normalized these sequences to characterize B. cinerea-responsive miRNAs (Additional file 1: Table S1). We identified 57 known miRNAs (from 24 families) that were differentially expressed in response to B. cinerea stress (Additional file 5: Table S3). Among these differentially expressed miRNAs, 41 were upregulated and 16 were downregulated in the TD7d library in comparison with the TC7d library. The abundances of 40 miRNA families or the sum of read counts in each miRNA family was calculated and used in differential expression analysis; the results are presented in Table 2. We found that 8 miRNA families were differentially expressed in B. cinerea-infected leaves. Seven families, miR159, miR169, miR319, miR394, miR1919, miR1446, and miR5300, were upregulated and only 1 family, miR2111, was downregulated in B. cinerea-infected leaves. Thus, the majority of B. cinerea-responsive miRNAs or families were upregulated in the TD7d library in comparison with the TC7d library, suggesting that the upregulation of miRNAs is involved in plant responses to B. cinerea infection.

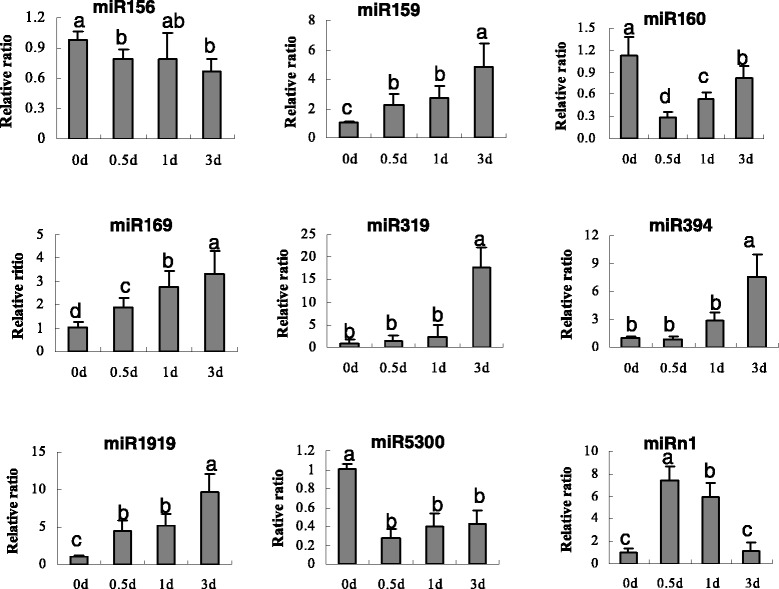

Dynamic expression of B. cinerea-responsive miRNA

We also confirmed the Solexa sequencing results and evaluated the dynamic expression patterns of B. cinerea-responsive miRNAs at different times after B. cinerea-inoculation (0, 0.5, 1, and 3 days). We examined the expression patterns by subjecting 9 B. cinerea-responsive miRNAs, including 8 known miRNAs (miR156, miR159, miR160, miR169, miR319, miR394, miR1919, and miR5300) and 1 novel miRNA (miRn1), to quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) (Figure 5). The Student’s t-test was performed and the probability values of p < 0.05 were considered significant. Consistently with sRNA sequencing data, qRT-PCR results showed that 6 miRNAs, miR159, miR169, miR319, miR394, miR1919, and miRn1, were upregulated at each examined time point after B. cinerea inoculation. The expression of the first 5 miRNAs increased gradually. In contrast, miRn1 was rapidly upregulated and reached the maximum expression at 0.5 days. miR160 and miR5300, were downregulated; however, no significant differential expression in B. cinerea-inoculated leaves was observed for miR156 (Figure 5). These results are consistent with previous data reported by Weiberg et al. [2]. Therefore, these miRNAs, except for miR156, may be involved in the response to B. cinerea infection in tomato leaves.

Figure 5.

Quantitative analysis of 9 B.cinerea -rsponsive miRNAs by qRT-PCR at 0, 0.5, 1 and 3 day. U6 RNA was used as the internal control. Error bars indicate SD obtained from three biological repeats.

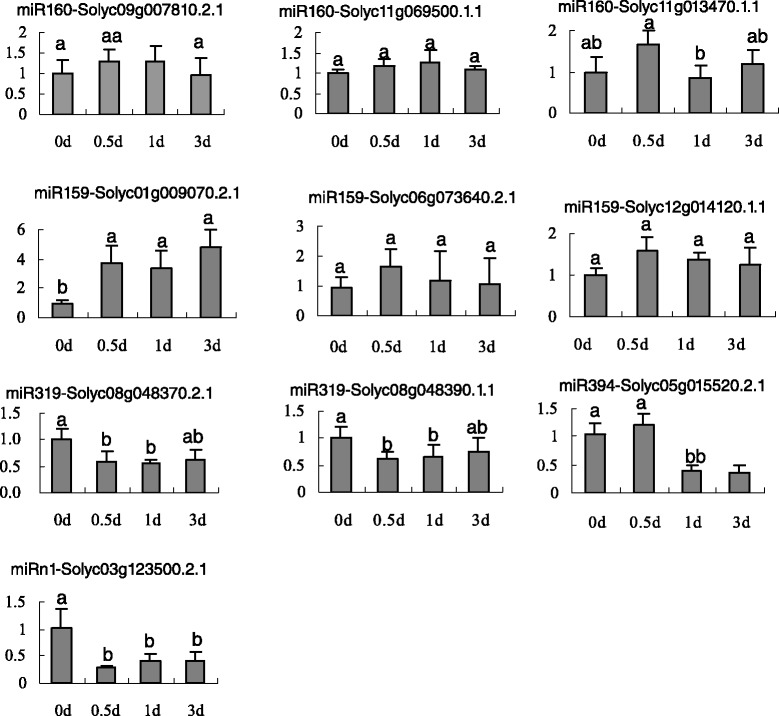

The expression profiles of the B. cinerea-responsive miRNA targets

CleaveLand pipeline was performed to predict the targets of the seven known B. cinerea-responsive miRNAs (miR159, miR160, miR169, miR319, miR394, miR1919, and miR5300), thereby detecting the expression profiles of their target genes. The results showed that the seven known miRNAs targeted 28 CDS targets (Table 3). The psRNAtarget program was used for the second screening of the targets, only 9 CDSs were targeted by 4 known miRNAs, namely miR159, miR160, miR319, and miR394 (Additional file 6: Table S4). Moreover, no CDS was predicted as a target of the remaining three miRNAs, namely miR169, miR1919, and miR5300. The expression profiles of these nine target CDSs and Solyc03g123500.2.1 were determined using qRT-PCR at different times (0, 0.5, 1, and 3 d) after the inoculation of B. cinerea. The result showed in Figure 6. Two members of the TCP transcriptional factor family (Solyc08g048370.2.1 and Solyc08g048390.1.1), an F-box protein (Solyc05g015520.2.1) and a Pathogenesis-related transcriptional factor (Solyc03g123500.2.1), which were targeted by miR319, miR394 and miRn1, respectively, were significantly downregulated in B. cinerea-inoculated leaves at different times (Figure 6), and exhibited a negative relationship to the expression of the 3 miRNAs (Figure 5). However, a MYB transcriptional factor (Solyc01g009070.2.1), which was targeted by miR159, was significantly upregulated and exhibited a consistent expression pattern with that of miR159. In addition, no significant differential expression in B. cinerea-inoculated leaves was observed in the remaining five target CDSs (Figure 6). Therefore, the results strongly suggested that the miR319, miR394 and miRn1 may be involved in the responses to B. cinerea infection in tomato leaves.

Figure 6.

Quantitative analysis of 10 CDSs targeted by 5 B.cinerea -rsponsive miRNAs by qRT-PCR at 0, 0.5, 1 and 3 day. Actin was used as the internal control. Error bars indicate SD obtained from three biological repeats.

Discussion

miRNAs have been found as post-transcriptional regulators in many eukaryotic plants and are involved in the response to various environmental stresses [30,31]. To identify tomato miRNAs associated with the resistance to B. cinerea, we performed high-throughput sequencing of TD7d and TC7d libraries constructed from B. cinerea- and mock-inoculated tomato leaves, respectively. The results showed substantially higher abundance of 21-nt miRNAs in the TD7d library than in the TC7d library, indicating that the upregulation of the 21-nt miRNA classes may be important in the response to B. cinerea infection. The relative abundances of 24-nt sRNAs in the TD7d library were markedly lower than those in the TC7d library. Plant 24-nt small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are mostly derived from repeats and transposons. These 24-nt siRNAs trigger DNA methylation at all CG, CHG, and CHH (where H = A, T, or C) sites, resulting in H3K9me2 modifications [32]. These modifications reinforce transcriptional silencing of transposons and genes that harbor or are adjacent to repeats or transposons in Arabidopsis [33-38]. In this study, the decreased number of 24-nt sRNAs in TD7d library suggested that the levels of DNA methylation at some specific loci are reduced in response to B. cinerea infection. We could reasonably assume that the reduced DNA methylation exposes some host genes, which could enhance the resistance or susceptibility to B. cinerea infection. Further research will be necessary to prove these assumptions.

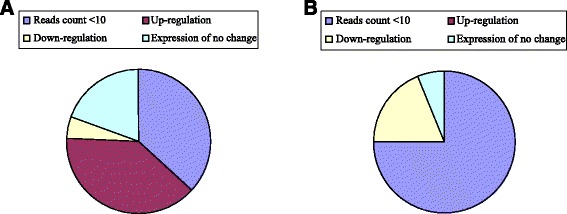

In this study, 57 known miRNAs from 24 families were differentially expressed in the response to B. cinerea stress (Additional file 5: Table S3). Among these differentially expressed miRNAs, 41 were upregulated and 16 were downregulated in the TD7d library compared with those in the TC7d library. We compared the expression profiles of these 57 differentially expressed miRNAs with the published data on B. cinerea-infected tomato leaves at 0, 24, and 72 h after inoculation [2]. A total of 27 miRNAs presented low read counts (<10) in the three libraries (Figure 7). The total read count in each of TC7d and TD7d was approximately two to the three times higher than that in the three libraries. Most of the 27 miRNAs presented lower read counts than the 20 miRNAs in the present study. Among the remaining 30 miRNAs, most differentially expressed miRNAs also showed consistent expression profiles between our data and the reported data (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Match analysis for the 57 miRNA profiles in this study and previous reported data [ 2 ]. The Match analysis for 41 miRNAs A) and 16 miRNAs B) which were up- and down-regulated in the TD7d library in comparison with the TC7d library, respectively.

We obtained 31 novel miRNA candidates derived from 33 loci, which satisfied the screening criteria. Seven of these novel miRNA candidates contained miRNA* sequences identified from the same libraries, whereas 24 candidates did not contain any identified miRNA* sequences (Additional file 2: Table S2). We performed a gel blot analysis to validate these seven novel miRNAs and determine their expression patterns. MiRn7 was not expressed, but miRn6 was expressed in mock- and B. cinerea-infected leaves (Figure 3). This finding is inconsistent with the sRNA-seq data, in which miRn7 exhibited higher read count than miRn6 (Additional file 2: Table S2). We speculated that few miRNAs may show inconsistent abundance values when examined using two different methods, i.e., Northern blot and sRNA-seq.

miR319 is a conserved miRNA that mediates the changes in plant morphology [39-43]. Some microarray data suggest that this miRNA is also involved in plant responses to drought and salinity stress; transgenic plants of creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera) with an overexpressed rice miR319 gene have enhanced resistance to drought and salt stress [44]. Our results showed that transient overexpression of miR319 may increase the resistance of tomato plants to B. cinerea.

miR394 is a conserved miRNA found in several plant species [45-48]. Liu et al. [49] have found that high salinity upregulates the expression of miR394 in Arabidopsis. The expression of miR394b in roots and miR394a and miR394b in shoots is initially upregulated and then downregulated under iron-deficient conditions [50]. In Brassica napus, miR394a, b, and c are upregulated in the roots and stems under sulfate-deficient conditions [47]. Similarly, the expression of miR394a, b, and c in all plant tissues is induced by cadmium treatment [47]. Song et al. [51] have reported that miR394 and its target, the F-box gene At1g27340, are involved in the regulation of leaf curling-related morphology of Arabidopsis. The available data suggest that miR394 is involved in the development and abiotic stress regulation. Furthermore, transgenic plants overexpressing the Arabidopsis miR319a gene may have enhanced drought resistance but diminished salt tolerance [52]. In this study, we found that the transient overexpression of miR394 may also increase the resistance of tomato leaves to B. cinerea.

Conclusions

This study was the first to perform a genome-wide identification of miRNAs involved in resistance against B. cinerea by using sRNA sequencing and transient overexpression in tomato leaves. We identified 174 miRNAs, including 143 known and 31 novel miRNAs, by using the high-throughput sequencing data of B. cinerea-infected and mock-infected tomato leaves. Among these 174 miRNAs, 58 were differentially expressed in B. cinerea-stressed leaves. Our study showed that the upregulated miRNAs may play important roles in the response to B. cinerea infection in tomato plants. We also found that that upregulated miRNAs inhibited the expression of their targets. Hence, these miRNAs may be involved in the response to B. cinerea infection in tomato leaves.

Methods

Plants, B. cinerea inoculation, and RNA extraction

Tomatoes (S. lycopersicum) cv. Jinpeng 1 were used as host plants; they were grown in a greenhouse at a 16-h day/8-h night cycle, at 22–28°C. At the age of 6 weeks, plants were inoculated using a solution containing B. cinerea conidia (2 × 106 spores ml−1), 5 mM glucose, and 2.5 mM KH2PO4. The inoculation solution was applied to both leaf surfaces using a soft brush. After inoculation, the plants were kept at 100% relative humidity to ensure spore germination. The B. cinerea- and mock-inoculated leaves were harvested at 5 time points (0 days, 0.5 days, 1 days, 3 days, and 7 days) after treatment, in 3 biological replicates. We found that the B. cinerea spores appeared on the leaves at 7 dpi. The 7-dpi leaves of B. cinerea-infected (TD7d) and control (TC7d) plants were sent to BGI (Shenzheng, China) for the deep sequencing of sRNAs. The samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C for the studies of transcript expression.

Total RNAs were extracted from leaf tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), followed by RNase-free DNase treatment (Takara, Dalian, China). Their concentrations were quantified using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer.

Identification of novel miRNAs in tomato

For the prediction of novel miRNAs, the unique sequences with a minimum raw reads count of 10 in each library were extracted and combined into 1 sRNA library for miRNA prediction; all reads that matched to tomato coding RNA, tRNA, rRNA, or known miRNA sequences with 2 mismatches were removed. The remaining reads were mapped to genomic sequences from ftp://ftp.solgenomics.net/tomato_genome/wgs/assembly/build_2.40 using Bowtie with a maximum of 2 mismatches [53]. With 1 end anchored 20 bp away from the mapped sRNA location, sequences of 120 to 360 bp with each extension of 20 bp that covered the sRNA region were collected. Secondary structures of each sequence were predicted using the RNAfold tool from the Vienna package (version 1.8.2) [54]. Under conditions similar to those suggested by Meyers et al. [28] and Thakur et al. [29], stem–loop structures with ≤3 gaps involving ≤8 bases at the sRNA location and miRNA–miRNA* duplexes accounting for more than 75% reads mapping to the precursor locus were considered candidate miRNA precursors. Finally, the candidate miRNAs matching with no mismatch to all plant miRNAs deposited into miRBase database (Version 20.0) [22] were considered to be conserved miRNAs and the remaining were considered to be novel miRNA candidates.

Identification of B. cinerea-responsive miRNAs

The frequency of miRNAs from the 2 libraries was normalized to 1 million by total clean reads of miRNAs in each sample (RPM). If the normalized read count of a given miRNA was zero, the expression value was modified to 0.01 for further analysis. The fold-change between the TD7d and TC7d libraries was calculated using following the equation: Fold-change = log2 (TD7d/TC7d). The miRNAs with fold-changes of >2 or <0.5 and p-values of ≤0.001 were considered to be upregulated or downregulated in response to B. cinerea stress, respectively. The p-value was calculated according to the previously established methods [55].

Validation of identified miRNAs using RNA gel blot

For each sample, a 100 μg-aliquot of RNA was resolved on a 15% polyacrylamide/1× TBE/8 M urea gel and subsequently transferred to a GeneScreen membrane (NIN). DNA oligonucleotides that were perfectly complementary to candidate miRNAs (Additional file 7: Table S5) were end-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) to generate highly specific probes. Hybridization and washing procedures were performed as described previously [9]. The membranes were briefly air-dried and then read in a phosphoimager.

Identification of miRNA targets

For identifying the miRNA targets, the degradome data of tomato leaves was downloaded from NCBI GEO database (accession number: GSM553688). The FASTA files of tomato CDS sequences were downloaded from the ftp site ftp://ftp.solgenomics.net/genomes/Solanum_lycopersicum/nnotation/ITAG2.3_release/ITAG2.3_cds.fasta. Following this, CleaveLand pipeline was first employed for detecting the cleaved targets of miRNAs [56,57]. The online psRNAtarget program was further used for target identification (http://plantgrn.noble.org/psRNATarget/?function = 3).

Target validation of RLM-RACE analysis

miRNA-mediated target gene cleaveage was confirmed using total RNA by 5′ RLM-RACE, as previously described [58]. In brief, poly (A) + RNA was isolated from cucumber leaves using a magnetic mRNA isolation kit (NEB, UK). The cleaved products were uncapped and carried a free phosphate, thereby allowing direct ligation with the RNA adaptor RA44 using T4 RNA Ligase (Ambion, USA). The ligation products were extracted using phenol/chloroform and precipitated with glycogen before first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, USA). Nested PCR was performed using premix ExTaq™ Hot Start Version (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and RA44OP/IP and GSP1/GSP2 primers in order to detect the cleaved products. The amplicons were further confirmed by sequencing. The adaptor and primers used for 5′ RLM-RACE analysis are listed in Additional file 7: Table S5.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Expression profiles of the B. cinerea-responsive miRNAs were assayed by qRT-PCR. Total RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase I (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) to remove genomic DNA. Forward primers for 5 selected miRNAs were designed based on the sequence of the miRNAs and are listed in Additional file 7: Table S5. The reverse transcription reaction was performed with the One Step PrimeScript miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol [20].

SYBR Green PCR was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions (Takara, Japan). In brief, 2 μl of cDNA template was added to 12.5 μl of 2× SYBR Green PCR master mix (Takara), 1 μM each primer, and ddH2O to a final volume of 25 μl. The reactions were amplified for 10 s at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 30 s. All reactions were performed in triplicate, and the controls (no template and no RT) were included for each gene. The threshold cycle (CT) values were automatically determined by the instrument. The fold-changes for miR811 and miR845 were calculated using 2−ΔΔCt method, where ΔΔCT = (CT,target − CT,inner)Infection − (CT,target − CT,inner)Mock [59].

Availability of supporting data

The data sets supporting the results of this article are included within the article and its additional files. The sRNA-seq data sets of TC7d and TD7d libraries are available in NCBI SRA database under accession number SRP043615. The clean reads of TC7d and TD7d data sets are also available in Additional files 8 and 9.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 31372075 and 31000913).

Abbreviations

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse-transcription PCR

- CDS

Coding sequence

- miRNAs

microRNAs

- B.cinerea

Botrytis cinerea

- sRNAs

small RNAs

- AGO

Argonaute

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing complex

- PTI

PAMP-triggered immunity

- TIR1

Transport inhibitor response 1

- AFB2

Auxin signaling F-Box protein 2

- dpi

Days post inoculation

- RPM

Reads per million

- miRNA*

miRNA-star

- siRNA

small interfering RNAs

- RLM-RACE

RNA ligase mediated rapid amplification of cDNA ends

Additional files

Identification and characterization of known miRNA members.

Identification and expression analysis of novel miRNAs in tomato.

Identification of the novel miRNAs.

Target plots (t-plots) of miRNAs targets confirmed by using degradome sequencing in tomato.

The differential expression of known miRNAs.

Prediction the targets of B.cinerea-responsive miRNAs via psRNAtarget.

Primers used in this study.

TC7d.tar.gz. Compressed file of TC7d sRNA-seq data with a minimum raw reads count of 2.

TD7d.rar.gz. Compressed file of TD7d sRNA-seq data with a minimum raw reads count of 2.

Footnotes

Weibo Jin and Fangli Wu contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

WJ and FW carried out most of the experiments. WJ designed the experiments, performed bioinformatics analysis and wrote the paper. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Weibo Jin, Email: jwb@zstu.edu.cn.

Fangli Wu, Email: wfl@zstu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Sommer NF, Fortlage RJ, Edwards DC. Postharvest diseases of selected commodities. In: Kader AA, editor. Postharvest technology of horticultural crops. Davis, USA: University of California Davis, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, and Publication; 1992. pp. 117–60. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiberg A, Wang M, Lin FM, Zhao HW, Zhang ZH, Kaloshian I, et al. Fungal small RNAs suppress plant immunity by hijacking host RNA interference pathways. Science. 2013;342:118. doi: 10.1126/science.1239705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Kan J. Licensed to kill: the lifestyle of a necrotrophic plant pathogen. Trends Plant Sci. 1996;11:247–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choquer M, Fournier E, Kunz C, Levis C, Pradier JM, Simon A, et al. Botrytis cinerea virulence factors: new insights into a necrotrophic and polyphageous pathogen. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;277:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Audenaert K, De Meyer GB, Höfte MM. Abscisic acid determines basal susceptibility of tomato to Botrytis cinerea and suppresses salicylic acid-dependent signaling mechanisms. Plant Physiol. 2002;128:491–501. doi: 10.1104/pp.010605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boller T. Ethylene in pathogenesis and disease resistance. In: Mattoo AK, Suttle JC, editors. The plant hormone ethylene. Boca Raton, F.L: CRC press; 1991. pp. 293–314. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bleecker AB, Kende H. Ethylene: a gaseous signal molecule in plants. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:13–8. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li XH, Zhang YF, Huang L, Ouyang ZG, Hong YB, Zhang HJ, et al. Tomato SlMKK2 and SlMKK4 contribute to disease resistance against Botrytis cinerea. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sunkar R, Zhu JK. Novel and stress-regulated microRNAs and other small RNAs from Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2004;16:2001–19. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.022830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J, Rivas FV, Wohlschlegel J, Yates JR, III, Parker R, Hannon GJ. A role for the P-body component GW182 in microRNA function. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1261–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Navarro L, Dunoyer P, Jay F, Arnold B, Dharmasiri N, Estelle M, et al. A plant miRNA contributes to antibacterial resistance by repressing auxin signaling. Science. 2006;312:436–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1126088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhai J, Jeong DH, De Paoli E, Park S, Rosen BD, Li Y, et al. MicroRNAs as master regulators of the plant NB-LRR defense gene family via the production of phased, trans-acting siRNAs. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2540–53. doi: 10.1101/gad.177527.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li F, Pignatta D, Bendix C, Brunkard JO, Cohn MM, Tung J, et al. MicroRNA regulation of plant innate immune receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:1790–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118282109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shivaprasad PV, Chen HM, Patel K, Bond DM, Santos BA, Baulcombe DC. A microRNA superfamily regulates nucleotide binding site-leucine-rich repeats and other mRNAs. Plant Cell. 2012;24:859–74. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.095380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitham S, Dinesh-Kumar SP, Choi D, Hehl R, Corr C, Baker B. The product of the tobacco mosaic virus resistance gene N: similarity to toll and the interleukin-1 receptor. Cell. 1994;78:1101–15. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin W, Wu F, Xiao L, Liang G, Zhen Y, Guo Z, et al. Microarray-based analysis of tomato miRNA regulated by botrytis cinerea. J Plant Growth Regul. 2012;31:38–46. doi: 10.1007/s00344-011-9217-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh LC, Lin SI, Shih AC, Chen JW, Lin WY, Tseng CY, et al. Uncovering small RNA-mediated responses to phosphate deficiency in Arabidopsis by deep sequencing. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:2120–32. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.147280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Bartel B. MicroRNAs and their regulatory roles in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:19–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lelandais-Brière C, Naya L, Sallet E, Calenge F, Frugier F, Hartmann C, et al. Genome-wide Medicago truncatula small RNA analysis revealed novel microRNAs and isoforms differentially regulated in roots and nodules. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2780–96. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang TZ, Chen L, Zhao MG, Tian QY, Zhang WH. Identification of drought-responsive microRNAs in Medicago truncatula by genome-wide high-throughput sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:367. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen L, Ren YY, Zhang YY, Xu JC, Sun FS, Zhang ZY, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of heat-responsive and novel microRNAs in Populus tomentosa. Gene. 2012;504:160–5. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffiths-Jones S, Grocock RJ, van Dongen S, Bateman A, Enright AJ. miRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D140–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou ZS, Song JB, Yang ZM. Genome-wide identification of Brassica napus microRNAs and their targets in response to cadmium. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:4597–613. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fattash I, Voss B, Reski R, Hess WR, Frank WE. Evidence for the rapid expansion of microRNA-mediated regulation in early land plant evolution. BMC Plant Biol. 2007;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeong DH, Park S, Zhai J, Qurazada SGR, De Paoli E, Meyers BC, et al. Massive analysis of rice small RNAs, mechanistic implications of regulated microRNAs and variants for differential target RNA cleavage. Plant Cell. 2011;23:4185–207. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.089045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu X, Wang H, Lu YZ, Ruiter M, Cariaso M, Prins M, et al. Identification of conserved and novel microRNAs that are responsive to heat stress in Brassica rapa. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:1025–38. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang JH, Liu XY, Xu BC, Zhao N, Yang XD, Zhang MF. Identification of miRNAs and their targets using high-throughput sequencing and degradome analysis in cytoplasmic male-sterile and its maintainer fertile lines of Brassica juncea. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyers BC, Axtell MJ, Bartel B, Bartel DP, Baulcombe D, Bowman JL, et al. Criteria for annotation of plant microRNAs. Plant Cell. 2008;20:3186–90. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thakur V, Wanchana S, Xu M, Bruskiewich R, Quick WP, Mosig A, et al. Characterization of statistical features for plant microRNA prediction. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang B, Pan X, Cannon CH, Cobb GP, Anderson TA. Conservation and divergence of plant microRNA genes. Plant J. 2006;46:243–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khraiwesh B, Zhu JK, Zhu JH. Role of miRNAs and siRNAs in biotic and abiotic stress responses of plants. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1819;2012:137–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei L, Gu L, Song X, Cui X, Lu Z, Zhou M, et al. Dicer-like 3 produces transposable element-associated 24-nt siRNAs that control agricultural traits in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:3877–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318131111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J, He Y, Amasino R, Chen X. siRNAs targeting an intronic transposon in the regulation of natural flowering behavior in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2873–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.1217304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lippman Z, Gendrel AV, Black M, Vaughn MW, Dedhia N, McCombie WR, et al. Role of transposable elements in heterochromatin and epigenetic control. Nature. 2004;430:471–6. doi: 10.1038/nature02651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henderson IR, Jacobsen SE. Tandem repeats upstream of the Arabidopsis endogene SDC recruit non-CG DNA methylation and initiate siRNA spreading. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1597–606. doi: 10.1101/gad.1667808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cao X, Jacobsen SE. Role of the Arabidopsis DRM methyltransferases in de novo DNA methylation and gene silencing. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1138–44. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00925-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu C, Tian J, Mo B. siRNA-mediated DNA methylation and H3K9 dimethylation in plants. Protein Cell. 2013;4:656–63. doi: 10.1007/s13238-013-3052-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhai J, Liu J, Liu B, Li P, Meyers BC, Chen X, et al. Small RNA-directed epigenetic natural variation in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nath U, Crawford BCW, Carpenter R, Coen E. Genetic control of surface curvature. Science. 2003;299:1404–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1079354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palatnik JF, Allen E, Wu X, Schommer C, Schwab R, Carrington JC, et al. Control of leaf morphogenesis by microRNAs. Nature. 2003;425:257–63. doi: 10.1038/nature01958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ori N, Cohen AR, Etzioni A, Brand A, Yanai O, Shleizer S, et al. Regulation of LANCEOLATE by miR319 is required for compound-leaf development in tomato. Nat Genet. 2007;39:787–91. doi: 10.1038/ng2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schommer C, Palatnik JF, Aggarwal P, Chételat A, Cubas P, Farmer EE, et al. Control of jasmonate biosynthesis and senescence by miR319 targets. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nag A, King S, Jack T. miR319a targeting of TCP4 is critical for petal growth and development in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:22534–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908718106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou M, Li D, Li Z, Hu Q, Yang C, Zhu L, et al. Constitutive expression of a miR319 gene alters plant development and enhances salt and drought tolerance in transgenic creeping Bentgrass. Plant Physiol. 2013;161:1375–91. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.208702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP. Computational identification of plant microRNAs and their targets, including a stress-induced miRNA. Mol Cell. 2004;14:787–99. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu S, Sun YH, Chiang VL. Stress-responsive microRNAs in Populus. Plant J. 2008;55:131–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang SQ, Xiang AL, Che LL, Chen S, Li H, Song JB, et al. A set of miRNAs from Brassica napus in response to sulphate deficiency and cadmium stress. Plant Biotechnol J. 2010;8:887–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pantaleo V, Szittya G, Moxon S, Miozzi L, Moulton V, Dalmay T, et al. Identification of grapevine microRNAs and their targets using high-throughput sequencing and degradome analysis. Plant J. 2010;62:960–7. doi: 10.1111/j.0960-7412.2010.04208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu HH, Tian X, Li YJ, Wu CA, Zheng CC. Microarray-based analysis of stress-regulated microRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. RNA. 2008;14:836–43. doi: 10.1261/rna.895308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kong WW, Yang ZM. Identification of iron-deficiency responsive microRNA genes and cis-elements in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010;48:153–9. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song JB, Huang SQ, Dalmay T, Yang ZM. Regulation of leaf morphology by microRNA394 and its target leaf curling responsiveness. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012;53:1283–94. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Song JB, Gao S, Sun D, Li H, Shu XX, Yang ZM. miR394 and LCR are involved in Arabidopsis salt and drought stress responses in an abscisic acid-dependent manner. BMC Plant Biol. 2013;13:210. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-13-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memoryefficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hofacker IL. Vienna RNA secondary structure server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3429–31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Man MZ, Wang X, Wang Y. POWER_SAGE: comparing statistical tests for SAGE experiments. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:953–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.11.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Addo-Quaye C, Eshoo TW, Bartel DP, Axtell MJ. Endogenous siRNA and miRNA targets identified by sequencing of the Arabidopsis degradome. Curr Biol. 2008;18:758–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Addo-Quaye C, Miller W, Axtell MJ. CleaveLand: a pipeline for using degradome data to find cleaved small RNA targets. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:130–1. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu QH, Spriggs A, Matthew L, Fan L, Kennedy G, Gubler F, et al. A diverse set of microRNAs and microRNA-like small RNAs in developing rice grains. Genome Res. 2008;18:1456–65. doi: 10.1101/gr.075572.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(t)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]