Abstract

In summer 2012, a landfill liner comprising an estimated 1.3 million shredded tires burned in Iowa City, Iowa. During the fire, continuous monitoring and laboratory measurements were used to characterize the gaseous and particulate emissions and to provide new insights into the qualitative nature of the smoke and the quantity of pollutants emitted. Significant enrichments in ambient concentrations of CO, CO2, SO2, particle number (PN), fine particulate (PM2.5) mass, elemental carbon (EC), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) were observed. For the first time, PM2.5 from tire combustion was shown to contain PAH with nitrogen heteroatoms (a.k.a. azaarenes) and picene, a compound previously suggested to be unique to coal-burning. Despite prior laboratory studies’ findings, metals used in manufacturing tires (i.e. Zn, Pb, Fe) were not detected in coarse particulate matter (PM10) at a distance of 4.2 km downwind. Ambient measurements were used to derive the first in situ fuel-based emission factors (EF) for the uncontrolled open burning of tires, revealing substantial emissions of SO2 (7.1 g kg−1), particle number (3.5×1016 kg−1), PM2.5 (5.3 g kg−1), EC (2.37 g kg−1), and 19 individual PAH (totaling 56 mg kg−1). A large degree of variability was observed in day-to-day EF, reflecting a range of flaming and smoldering conditions of the large-scale fire, for which the modified combustion efficiency ranged from 0.85-0.98. Recommendations for future research on this under-characterized source are also provided.

Keywords: tire fire, emission factor, particle size distribution, PAH, azaarenes, Iowa City

1. Introduction

The widespread use of motor vehicles generates large quantities of scrap tires; in the United States of America in 2011, the Rubber Manufacturer's Association (RMA) estimates the generation of 231 million scrap tires (RMA, 2013). Active management programs in the USA remarket used tires as fuel (37.7%), ground rubber (24.6%), civil engineering materials (18.0%), exports (8.0%), and for other purposes (3.4%), while the remaining tires are landfilled (13%), baled with no market (0.9 %), or unaccounted for (4.6%) (RMA, 2013). Tires are an attractive chemical commodity, construction material, and solid fuel, due to their high energy density of 29-37 MJ kg−1 (Giere et al., 2004). The storage and reuse of tires requires attention to their potential environmental impact, including leaching and open-air burning. The risk of fire may be reduced by taking precautions to prevent ignition and spreading.

Uncontrolled tire fires are notoriously difficult to extinguish and release hazardous smoke and pyrolytic oil to the environment. The largest tire fire in United States history began in 1983 in Winchester, Virginia, where 7 million tires burned in nine months and polluted air and water in three surrounding states (Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, 2014). Since then, over a dozen major tire fires have been recorded in the United States (Singh et al., co-submitted). In countries without tire reuse and management programs, the frequency of tire fires is suggested to be much greater (Shakya et al., 2008; Stefanov et al., 2013). However, tire fires, particularly those that are small in scale, are largely undocumented, so that the frequency and magnitude of tire fires on a global scale is unknown.

The combustion of tires emits hazardous gases and particles to the atmosphere. These emissions reflect the chemical composition of tires, which are 50% natural or synthetic rubber by weight, 25% black carbon, 10% metal (mostly in the steel belt), 1% sulfur, 1% zinc oxide, and trace quantities of other materials (Seidelt et al., 2006). Laboratory studies of tire combustion report significant emissions of CO2 (2890 g kg−1), CO (71 g kg−1), NOx (6.0 g kg−1), and SO2 (28 g kg−1) (Stockwell et al., 2014), total suspended particles (TSP,65 -105 g kg−1), gaseous and particle-phase PAH (3.4-5.3 g kg−1), and volatile organic compounds (VOC, 12-50 g kg−1 ,e.g. benzene, toluene, xylene) (Lemieux and Ryan, 1993). Following a fire involving 6000 tires in Quebec in 2001, Wang et al. (2007) analyzed solid soot and liquid oil samples and identified 165 PAH and other aromatic compounds, many of which contained sulfur, nitrogen and oxygen heteroatoms. Emissions of PAH from co-firing tire crumbs in a high-efficiency boiler strongly depends on the fuel-to-air ratio; under oxygen-starved conditions, emissions of PAH increased by three orders of magnitude to a maximum of 7.2 g kg−1 (Levendis et al., 1996). Accordingly, the magnitude and chemical nature of emissions from burning tires depends on the combustion conditions.

Many pollutants emitted from tire burning are toxic, carcinogenic, and/or mutagenic; together, they present significant health hazards. In a mutagenicity assay, Demarini et al. (1994) reported that emissions from burning tires were more mutagenic than emissions from the open burning of plastic and burning of fossil fuels in utility boilers. Furthermore, mutagenicity levels were enhanced when tires were burned in oxygen-limited conditions, leading to the greater formation of PAH and related compounds. A comprehensive review of the health hazards posed by exposure to tire combustion emissions has been conducted by Singh et al. (co-submitted) and concludes that SO2, PM2.5, black carbon, acrolein, formaldehyde, and CO present significant health risks. Human exposure to tire burning emissions mainly occurs through inhalation of ambient air and depends on the proximity to the source and the strength and dilution of the smoke. Hence, persons living or working near tire fires (e.g. firefighters) have the greatest exposure. Of particular concern is the exposure of sensitive populations (e.g. children, elderly, and individuals with respiratory or cardiovascular disease) to emissions from this source, for whom the health impacts may be severe.

The current study characterized gas and particle emissions from an uncontrolled, large-scale tire fire that started at the municipal landfill in Iowa City, Iowa, USA on Saturday, May 26, 2012. What ignited the fire is unknown, but city officials speculated that hot charcoals or remnants of a burn barrel were dumped into the landfill Friday evening. High wind speeds led the fire to spread across seven acres of a one-meter-thick drainage layer made from shredded tires. An estimated 1.3 million tires (20.5 million kg) burned, generating more than 454,000 L of pryolytic oil and emitting a thick smoke plume. Public health officials issued public warnings for residents to avoid smoke exposure. Firefighting efforts to smother the fire with dirt commenced on June 4 and were completed by June 12, when smoke was no longer visible.

The goal of this paper is to characterize the emissions of gases and particles from the uncontrolled and large-scale open-burning of shredded tires. The field-based approach used in this study provides a real-world perspective on the open burning of tires, which has previously only been examined in small-scale, laboratory experiments (Lemieux and Ryan, 1993; Stockwell et al., 2014). Ambient measurements of particle number (PN), mass, and size distribution, EC, PAH, SO2, and CO are used to derive emission factors (EF) of key pollutants per kilogram of combusted tire. For the first time, EF for PN, PM2.5 mass, and PM2.5 PAH are determined, which are important to understanding the population exposure and potential health impacts of this source. EF from the in situ characterization of uncontrolled tire combustion are compared to prior laboratory studies in order to assess how emissions from this source differ under real-world and laboratory conditions. Furthermore, the EF determined in this study are used by Singh et al. (co-submitted) to assess the health risks posed by the tire fire smoke and to formulate recommendations on air monitoring needs in response to large-scale tire fires.

2. Methods

2.1 Filter Sample Collection and Analysis

PM samples were collected at the University of Iowa Air Monitoring Site (IA-AMS, 41.664527, -91.584735), located 4.2 km northeast of the Iowa City Landfill (41.652016, - 91.628081). Detailed site descriptions and map are provided in Singh et al. (co-submitted). PM10 samples were collected from May 30 to June 26, 2012 with a PM10 air sampler (Thermo 2025) on Teflon filters (Whatman) at 24 h intervals. PM2.5 samples were collected with a medium-volume sampling apparatus equipped with a Teflon-coated aluminum cyclone operating at 90 lpm (URG Corp) on quartz fiber filters (Whatman) pre-cleaned by baking at 550 °C for 18 hours. Filter changeovers occurred at midnight, with the following exceptions to the PM2.5 sample times: 00:00 May 27 to 08:00 May 28 (32 h), 08:00 to 08:00 (May 28 and 29), and 08:00 to 23:59 (16 h, May 30). One field blank was collected for every five samples.

2.2 Filter-based Measurements

Filter analyses followed well-established methodology and standard EPA methods, when available. PM10 mass was determined as the difference between Teflon filter masses (pre- and post-sample collection) measured by a high-precision balance (Mettler Toledo XP6) (EPA, 1999). PM2.5 mass was not directly determined, since quartz fiber filters are not suitable for mass determination; instead PM2.5 mass was estimated from measurements of particle number and assumptions described in the Supplemental Information. EC and OC were analyzed on sub-samples of PM2.5 quartz fiber filters by thermal-optical transmittance (Sunset Laboratories) following the ACE-Asia protocol (Schauer et al. 2003). Inorganic ions were measured in aqueous extracts of PM2.5 samples by ion chromatography (Dionex 5000) with suppressed conductivity detection (Jayarathne et al., 2014).

Total metals in PM10 were determined by nitric acid digestion of Teflon filters and analysis by inductively-coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, Agilent Technologies 7500ce) following EPA method EQL-0710-192 (EPA 2010). A representative strip of each filter was covered and extracted with dilute nitric acid (1:19, v/v) at 90-95 °C for 60-70 minutes in a 50-mL polypropylene extraction vessel. After cooling to room temperature the volume was brought to 50 mL using reagent grade water. Vessels were capped and shaken vigorously for 5 seconds. After standing for 30 minutes, vessels were shaken again, then allowed to settle for at least one hour before analysis. The ICP-MS scanned m/z 5-250 with unit mass resolution at 5% peak height. Instrument response was converted to concentration using an external calibration curve. Results were corrected for drift and matrix effects using internal standards. Laboratory control standards were within 80–120% of the expected values and instrument detection limits were sensitive to ambient concentrations above 1 ng m−3.

Organic species in PM2.5, including nineteen PAH with 3-7 rings, were solvent-extracted by ultrasonication and analyzed by gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS; Agilent Technologies 7890, 5975C) following Stone et al. (2012). Quartz fiber filters from May 24-July 3, 2011 and May 29-31, 2012 were composited to attain necessary sensitivity for meaningful reporting limits; other filters were extracted and analyzed individually. Analytes were quantified using 5-point calibration curves normalized to internal standards. Benzo[b]fluoranthene and benzo[k]fluoranthene co-eluted and were quantified together. Recoveries of spiked samples ranged from 85-135% of the expected values and analytical uncertainties were propagated from the method detection limit (~5 pg μL−1) and 20% of the measurement value. For qualitative analysis, GC with high-resolution MS (Agilent 7890A, Waters GCT ToF Premier Micromass) was applied to two ambient samples impacted by the tire fire plume (May 28 and June 2), a background sample (May 24), and a field blank.

2.3 On-line and Mobile Measurements

PM2.5 was measured in hourly intervals by a beta attenuation monitor (Met One BAM-1020) at Hoover Elementary, located 10.5 km east of the landfill (EPA site ID 191032001, 41.657232,-91.503478). For an immediate survey of the fire, handheld PM2.5 (TSI Dustrak 8520) and CO (TSI Q-Trak 7575) monitors were deployed at the edge of fire and downwind. A trailer intersected the tire fire plume at three locations ranging 3.2-3.4 km from the landfill from May 29-June 4, 2012. The trailer was equipped with: a Scanning Mobility Particle Sizer (TSI Classifier 3080, CPC 3025 with DMA 3081) for particles 14.6-661 nm at 135 second intervals; an Aerosol Particle Sizer (TSI APS Model 3321) for particles 0.54-20 μm at 10 second intervals; a condensation particle counter (TSI CPC 3786); a Vaisala 343 GMP flow-through CO2 monitor; an NDIR CO monitor (Thermo Scientific Model 48i-TLE); a SO2 UV fluorescence monitor (Teledyne 100E); and a roof-mounted weather station (DAVIS Vantage Pro2 Console). CO data was available only from May 29-31, 2012. On June 1, real-time instrumentation was deployed on a customized High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle (HMMWV or Humvee), which permitted mobile sampling at distances of 1.3, 3.2, and 4.8 km from the landfill. Samples were collected only while the Humvee was stopped and operating on batteries to avoid sampling of the vehicle's exhaust.

2.4 Calculation of Emission Factors of the Plume

EF for PM2.5, SO2 (g kg−1 fuel burned), and PN (cm−3) were calculated using Equation 1 (Lemieux et al., 2004):

| (1) |

where i is the pollutant, C represents carbon from CO and CO2, and fc is the mass fraction of carbon in the fuel, which is 0.85 for shredded tires (Quek and Balasubramanian, 2013). Concentrations of gases measured in real-time were averaged over 10 minutes. The conversion of CO2 mixing ratio to mass concentration assumed 25 °C and atmospheric pressure (i.e. 1 ppm CO2 is equivalent to 0.498 mgC m−3).

Plume-impacted samples were identified by visual inspection of time series data, field notes (where odor of the plume was noted), and wind direction. Background concentrations for PM2.5, CO, CO2, PN, and SO2 were calculated by averaging 30 minutes before and after each plume intercept, or from shorter time periods when plume intercepts occurred in quick succession. Enhancement of CO above background and the average CO:CO2 ratio was determined by P1-P4 in Figure 2. Equation 1 assumes tire carbon is emitted as CO2 and CO, ignoring VOC and PM, and does not account for up to 25% of tire carbon forming pyrolytic oil (Unapumnuk et al., 2006).

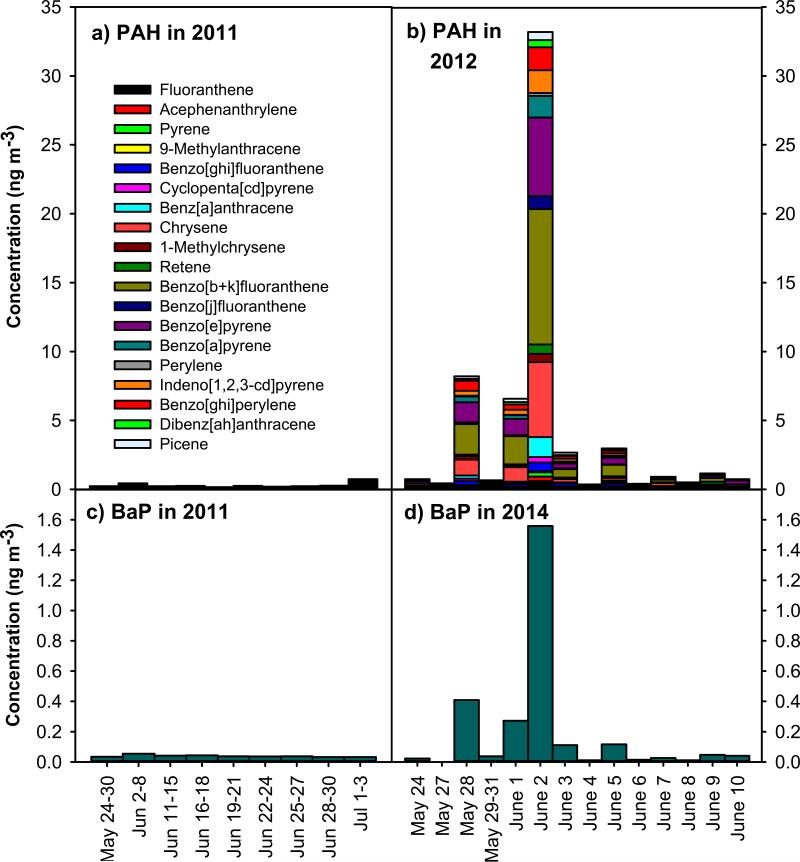

Figure 2.

Time series measurements of PAH and B[a]P during background (May-June 2011) and the tire fire period in 2012.

In cases where CO2 data was not available at the required location or time interval, Equation 2 (Lemieux et al., 2004) was used to calculate EF for species j relative to a species (k) for which EFk had been determined:

| (2) |

Size-resolved EFPN were determined relative to PM2.5, while EFPAH were calculated relative to EC following the assumption that EC comprised 45% of PM2.5 (Slowik et al., 2004).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Tire fire impacts on ambient EC, OC, PM2.5 and other fire-related species

The tire fire emitted a dense smoke plume with an acrid and irritating odor. During most periods, the plume was opaque and dark in color, indicating high mass loading and the presence of light absorbing PM. The smoke was, at times, visible from a distance of 35 km, and instantaneous Dustrak readings in the plume at 1 km from the source read over 2 mg m−3.

EC concentrations (measured at approximately 24 h intervals) at IA-AMS exceeded 0.45 μg m−3 on May 28, June 1-3, 5, and 7, and peaked at 0.8 μg m−3 on June 2 (Figure 1a). On these days, southwesterly winds transported the tire fire plume to IA-AMS. The plume-impacted EC levels were well above background levels measured in May-June 2011, which ranged from 0.06-0.38 μg m−3 and averaged 0.22±0.09 μg m−3. Meanwhile, plume-impacted OC concentrations ranged from 1.1-4.0 μg m−3, and were not significantly enhanced relative to 2011 concentrations (0.62-5.0 μg m−3, averaging 2.3±1.3 μg m−3). With enhanced EC and typical OC levels, plume-impacted samples had characteristically low OC:EC ratios ranging 3.6-7.4, compared to non-impacted days which ranged 9 to 46.

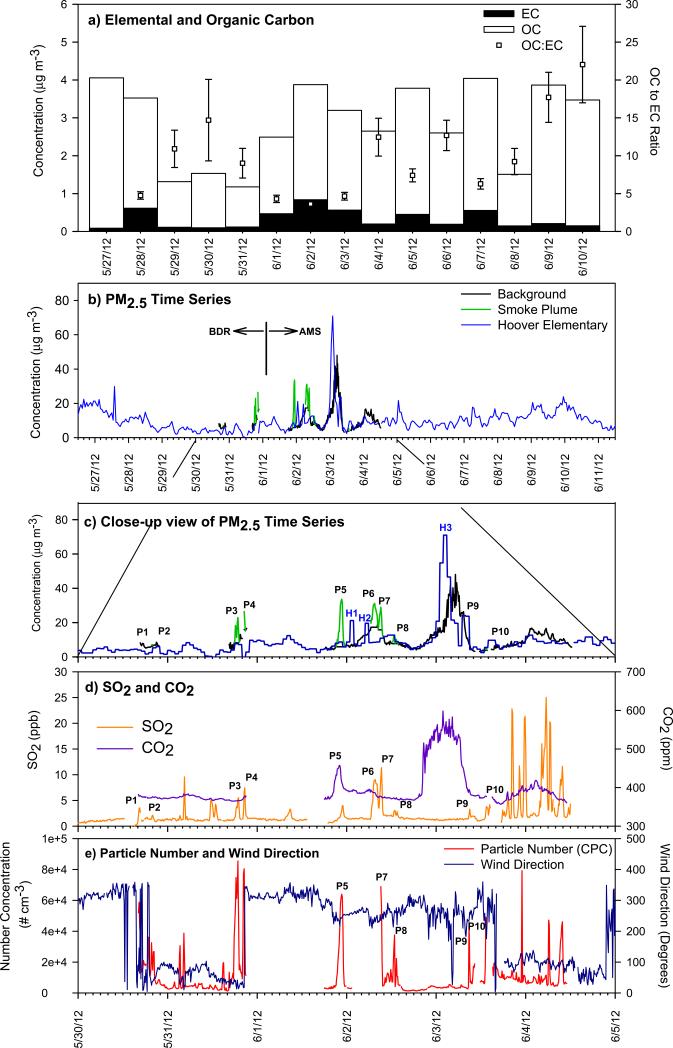

Figure 1.

Time series measurements tire-fire related species: a) OC, EC (left axis) and OC:EC (right axis) at IA-AMS, b) PM2.5 measured by mobile and stationary monitors, and close up view May 30-June 5 measurements of c) PM2.5, d) SO2 and CO2, and e) particle number and wind direction. The landfill is located at a bearing of 24° relative to the BDR site and at a be aring of 240° relative to the IA AMS site.

Ambient PM2.5 mass concentrations measured at Hoover Elementary, on Black Diamond Road (BDR), and IA-AMS are shown in Figures 1b and 1c. The tire fire plume impacted the monitor at Hoover Elementary on three occasions (marked H1-H3 in Figure 1c) when PM2.5 exceeded 70 μg m3 for periods of 20 min to 4 h. The plume-impacted samples were well above the 98th percentile PM2.5 levels measured at Hoover Elementary (< 25 μg m−3 for May-June 2012) (EPA, 2014), indicating a significant impact of the tire fire on local air quality.

At BDR and IA-AMS (3.2 and 4.2 km from the fire, respectively) the ten periods with enhanced PM2.5 concentrations were observed (marked P1-P10 in Figure 1c) with simultaneous increases in PN, CO2 and SO2 concentrations during periods with winds, consistent with transport from the landfill (Figure 1d and 1e). The unweighted average P1-P10 enhancements of PM2.5, PN, SO2, and CO2 above background levels were 12.0 μg m−3, 50,500 cm−3, 5.22 ppb and 24.1 ppm, respectively. SO2 spiked on June 3 after 17:00, but analysis of wind direction and operational logs indicate that these plumes very likely originated from the coal-fired power station in downtown Iowa City, located at a bearing of 102° and distance of 3.8 km from the IAAMS site. For plume intercepts with CO and CO2 measurements, the modified combustion efficiency, MCE = ΔCO2/(ΔCO2 + ΔCO), ranged 0.85-0.98, reflecting varied flaming and smoldering conditions (Yokelson et al., 1996).

The 24-h average PM2.5 mass concentration was 10.6 μg m−3 on June 2 at IA-AMS, consisting of 29% OC, 13% sulfate, 8% EC, 8% ammonium, 4% nitrate, and less than 1% each potassium, magnesium, and sodium. When applying an OC-to-organic-matter (OM) conversion factor of 1.8 (Turpin and Lim, 2001), uncharacterized mass accounted for 15% of PM2.5. Despite major emissions of SO2 and NOx from the tire fire, particle-phase sulfate and nitrate mass were not enhanced at the IA-AMS during periods of plume-impact, indicating that secondary inorganic aerosol formation did not significantly contribute to PM2.5 mass on the spatial scale of 4.2 km.

3.3 Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

Background and plume-impacted PM2.5 PAH concentrations are shown in Figure 2 and summarized in Table 2. Background PAH levels at IA-AMS measured in May-June 2011 ranged 0.15-0.42 ng m−3 and averaged 0.24 ng m−3 (Figure 2a) and were consistent with other rural locations in the Midwestern United States (Sun et al., 2006) when considering the same compounds measured across studies. On June 2, the 24 h PAH concentration peaked at 33.2 ng m−3, which is 138 times higher than background. Methyl-PAH (i.e. 1-methylchrysene), typically not detected in Iowa City, were detected in the tire fire plume (Figure 2b). Concentrations of benzo(a)pyrene (B[a]P), an indicator of carcinogenic PAH and Group 1 carcinogen are shown in for the 2011 background (Figure 2c) and tire fire period in 2012 (Figure 2d). Background B[a]P concentrations in May-June 2011 ranged from 0.03-0.12 ng m−3 with an average concentration of 0.04±0.01 ng m−3. During the tire fire, the maximum 24 h B[a]P concentration reached 1.6 ng m−3 on June 2, at 40 times above background.

Picene, a molecule typically considered a tracer for coal burning (Oros and Simoneit, 2000; Zhang et al., 2008; Zheng et al., 2006) was observed in the tire fire plume. Plume- impacted PM2.5 samples contained picene at 0.09-0.58 ng m−3, significantly above typical background levels (<0.01 ng m−3). This first observation of picene in tire burning emissions indicates that picene is not a unique tracer of coal combustion and raises questions about what other combustion sources may emit this PAH. In source apportionment studies, picene should not be used as a tracer for coal combustion if tire burning occurs in the surrounding airshed.

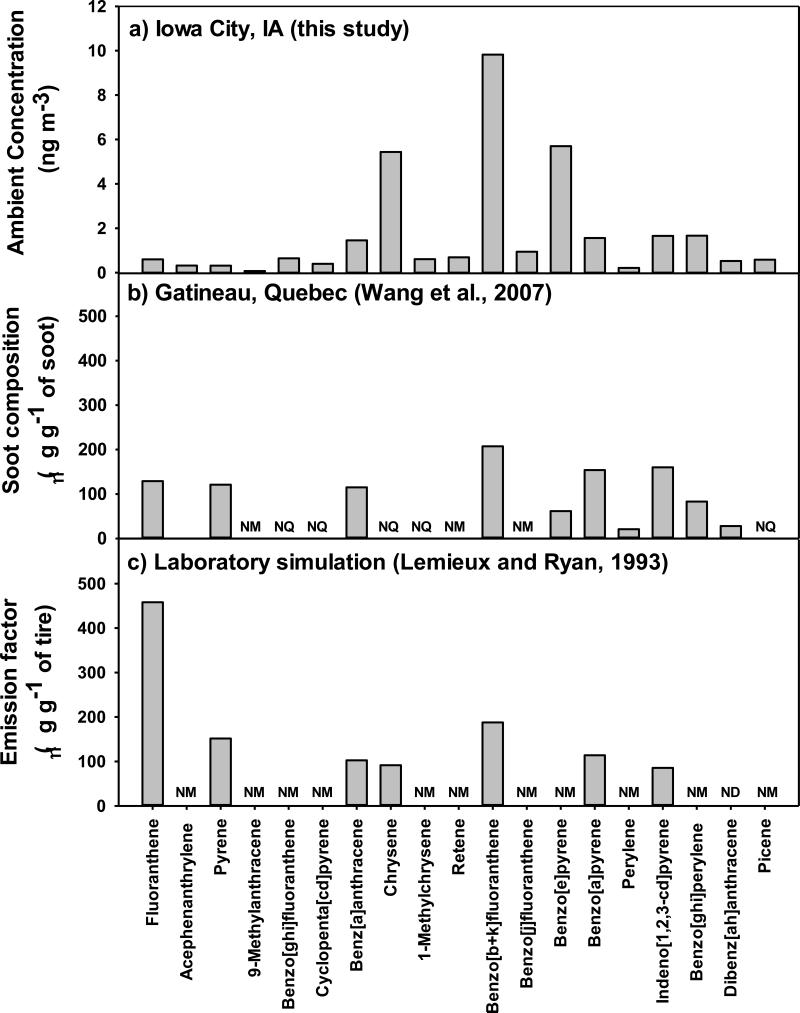

The relative concentrations of PM2.5 PAH measured at IA-AMS on June 2 are shown in Figure 3a. PAH with 4-5 fused aromatic rings were observed in the highest quantities, with benzo[b+k]fluoranthene, benzo[e]pyrene, and chrysene the most abundant. The presence of higher-ringed PAH is consistent with higher temperatures and low oxygen availability during combustion (Fitzpatrick et al., 2008). PAH with 3 rings, fluoranthene and acephenanthrylene, were observed at 6% and 3% of the concentration of benzo[b+k]fluoranthene. Generally, 2-3 ring PAH are primarily in the gas phase at ambient temperatures and pressures, 5-7 ring PAH are in the particle phase, and 4-ring PAH are distributed between the two phases. The distribution of PAH at AMS was shifted towards higher-molecular-weight PAH, indicating loss of 2-3 ring PAH to the gas phase.

Figure 3.

Distribution of PAH observed in a) PM2.5 impacted by the tire fire plume in Iowa City, b) soot following a tire fire in Quebec, Canada, and c) gas and particles in a laboratory study.

The IA-AMS PAH profile is compared in Figure 3b to the PAH profiled observed in soot particles following a 6000 whole-tire fire in Quebec, Canada (Wang et al., 2007). Similarly, 4-7 ring PAH were the most abundant, with maxima for benzo[b+k]fluoranthene, B[a]P, B[e]P, chrysene, and indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene. The decrease of B[a]P relative to B[e]P is an indicator of emission aging by photolysis (Bi et al., 2005). In soot samples, Wang et al. (2007) observed the B[e]P/(B[e]P + B[a]P) ratio to be 0.285, compared to a ratio of 0.80 at IA-AMS on days impacted by the plume. The increase in B[e]P relative to B[a]P in this study suggests that plume aging occurred during transport of the plume from the landfill to IA-AMS. Figure 3c shows a combined gas- and particle-phase PAH profile generated by open tire burning in the laboratory, in which the 3-ringed fluoranthene is most abundant (Lemieux and Ryan, 1993). Although only PM2.5 PAH were collected in Iowa City, it is expected that 2-3 ring PAH were present in relatively high concentrations in the gas phase.

3.4 Heterocyclic Aromatic Compounds

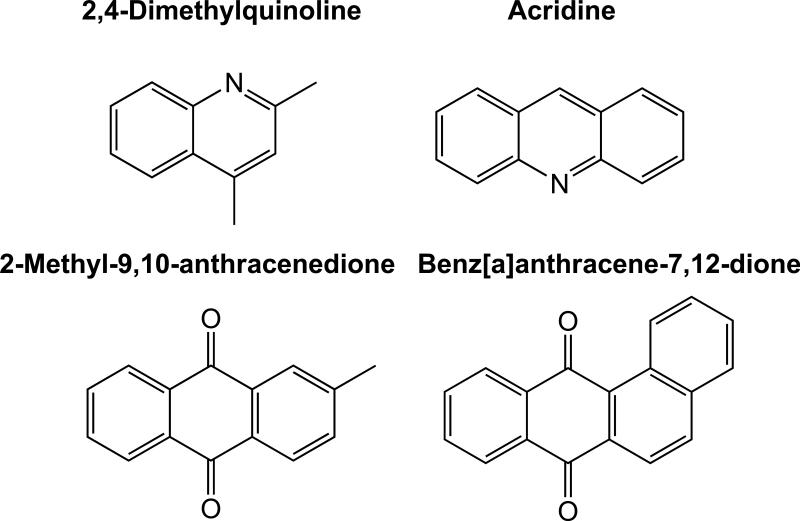

Two azaarenes—2,4-dimethylquinoline and acridine (Figure 4)—were observed in plume-impacted samples by high-resolution MS and confirmed against authentic standards (Table S2), and were not detected in background samples. These two azaarenes were previously associated with PM and soot generated by burning tires (Demarini et al., 1994; Wang et al., 2007). Azaarenes, with equal or greater toxic and genotoxic potentials than their parent PAH compounds (Bartos et al. 2006), have been suggested by Demarini et al. (1994) as major contributors to the mutagenicity of tire-burning emissions. Having been observed only in the tire fire plume-impacted samples, these azaarenes are qualitative indicators of tire burning.

Figure 4.

Molecular structures of azaarenes and oxy-PAH detected in the tire fire plume.

Partially oxygenated PAH (oxy-PAH) were also elevated in in plume-impacted PM2.5. 2-Methyl-9,10-anthracenedione and benz[a]anthracene-7,12-dione (Figure 4, Table S2) were observed in this study and in tire burning soot by Wang et al. (2007). Oxy-PAH may be emitted as directly to the atmosphere from combustion, or formed by secondary reaction of PAH. The oxy-PAH are generally less mutagenic than B[a]P (Durant et al., 1996) and are less of a health concern than are PAH and azaarenes.

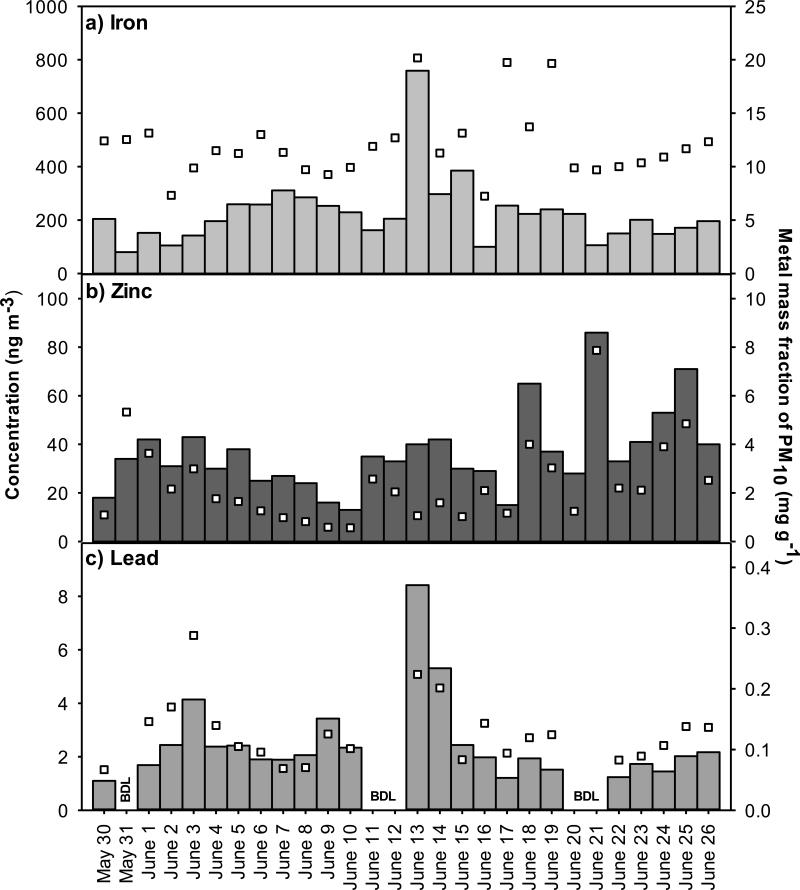

3.5 PM10 Metals

Ambient concentrations of total Fe, Zn and Pb in PM10 are shown in Figure 5 (left axis) with the metal mass fraction of PM10 (right axis). During the fire (May 30-June 12), concentrations of Fe, Zn, and Pb averaged 200±70 ng m−3, 29±9 ng m−3, and ranging from below detection (<1 ng m−3) to 4 ng m−3, respectively. Post-fire (June 13-26), these concentrations increased slightly to 250±170 ng m−3, 44±19 ng m−3 and 3±2 ng m−3, respectively. Absolute metal concentrations and mass fractions (Figure 5, right axis) exhibited no significant differences at the 95% confidence interval across tire fire and post-fire periods. On June 2, when the smoke plume from the fire was confirmed to have impacted IA-AMS (Figure 1), metal concentrations were below average. The observed PM10 lead concentrations at IA-AMS are consistent with typical background levels in Iowa; from 2008-2010, PM2.5 Pb concentrations averaged 2.2±0.6 ng m−3 at a rural site in Van Buren County and 2.3±0.8 ng m−3 at an urban site in Cedar Rapids (EPA, 2014). These data show no enhancement in the absolute or relative concentration of Fe, Zn, or Pb in PM10 at IA-AMS during the tire fire, indicating that the tire fire did not enhance the concentrations of respirable metals 4.2 km downwind.

Figure 5.

Time series of ambient PM10 metals concentrations (bars, left axis) and mass fraction (squares, right axis) at IA-AMS.

The lack of PM10 metal enhancement in this study is significant in light of prior studies that raised concern about emissions of toxic metals from tire burning. In their laboratory study, Lemieux and Ryan (1993) cautiously reported emissions of Zn and possibly Pb from TSP tire fires, but report results as “inconclusive” due to high blank levels. Elevated ambient concentrations of Pb, Fe, and Zn were detected in the Rinehart tire fire plume at levels of 11 μg m−3, 14 μg m−3, and 122 μg m−3, respectively (Reisman, 1997). The comparison of laboratory and field data suggests that particle-phase metals may be present in particles larger than PM10 that deposit near the source, but are neither in the respirable fraction nor transported long distances.

3.6 Fuel-based emission factors

Average fuel-based EF per kilogram tire for PN, particle mass, and SO2, for the ten plumes intercepted at IA-AMS (P1-P10 Figure 1), are presented in Table 1. Individual plume data are provided in Table S1.

Table 1.

Ambient concentrations of pollutants at Iowa City background and tire fire plume-impacted levels and fuel-based emission factors.

| Ambient Concentrations | Emission Factors (g kg−1 or # kg−1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formula | Background | Plume-impacted | Units | Mean | Std. Deviation | Median | |

| Carbon dioxidea | CO2 | 378.9 | 383.1 | (ppm) | - | - | - |

| Sulfur dioxidea | SO2 | 1.69 | 3.75 | (ppb) | 7.1 | 8.31 | 2.91 |

| PM2.5a | - | 9.81 | 15.1 | (μg m−3) | 5.35 | 5.39 | 3.05 |

| Elemental carbon | - | 0.22b | 0.84c | (μg m−3) | 2.41 | 2.43 | 1.37 |

| Particle numbera | - | 9800 | 39400 | (# cm−3) | 3.49E+16 | 3.41E+16 | 2.05E+16 |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbonsd | (mg kg−1) | (mg kg−1) | (mg kg−1) | ||||

| 9-Methylanthracene | C15H12 | BDLe | 0.07c | (ng m−3) | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.24 |

| Fluoranthene | C16H10 | 0.06 | 0.60 | (ng m−3) | 0.67 | 0.80 | 0.31 |

| Acephenanthrylene | C16H10 | BDL | 0.31 | (ng m−3) | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.31 |

| Pyrene | C16H10 | 0.02 | 0.64 | (ng m−3) | 0.70 | 0.34 | 0.52 |

| Benzo[ghi]fluoranthene | C18H10 | BDL | 0.64 | (ng m−3) | 1.6 | 0.5 | 1.4 |

| Cyclopenta[cd]pyrene | C18H10 | 0.08 | 0.39 | (ng m−3) | 0.65 | 0.34 | 0.54 |

| Benz[a]anthracene | C18H12 | 0.02 | 1.45 | (ng m−3) | 1.8 | 2.2 | 0.88 |

| Chrysene | C18H12 | 0.07 | 5.44 | (ng m−3) | 8.3 | 8.0 | 4.4 |

| Retene | C18H18 | BDL | 0.61 | (ng m−3) | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.45 |

| 1-Methylchrysene | C19H14 | BDL | 0.69 | (ng m−3) | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Benzo[b+k]fluoranthene | C20H12 | 0.16 | 9.82 | (ng m−3) | 17 | 13 | 11 |

| Benzo[j]fluoranthene | C20H12 | BDL | 0.94 | (ng m−3) | 1.1 | 1.4 | 0.48 |

| Benzo[e]pyrene | C20H12 | 0.18 | 5.70 | (ng m−3) | 9.8 | 7.6 | 6.7 |

| Benzo[a]pyrene | C20H12 | 0.02 | 1.56 | (ng m−3) | 2.3 | 2.2 | 1.5 |

| Perylene | C20H12 | 0.02 | 0.21 | (ng m−3) | 0.35 | 0.26 | 0.25 |

| Indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene | C22H12 | 0.05 | 1.65 | (ng m−3) | 2.9 | 2.1 | 1.8 |

| Benzo[ghi]perylene | C22H12 | 0.06 | 1.66 | (ng m−3) | 3.4 | 2.1 | 2.6 |

| Dibenz[ah]anthracene | C22H14 | BDL | 0.53 | (ng m−3) | 1.1 | 0.65 | 0.77 |

| Picene | C22H14 | BDL | 0.58 | (ng m−3) | 1.6 | 0.68 | 1.2 |

| Sum of quantified PAH | - | - | 33.4 | (ng m−3) | 56 | 44 | 37 |

Determined from samples collected 30 May to 3 June, 2012 (n = 10)

May-June 2011 background (n=28)

greatest plume-impact on June 2, 2012 (n=1)

EF determined from samples collected 28 May to 5 June, 2012 (n = 5)

pre-tire fire May 24, 2012 levels (n=1).

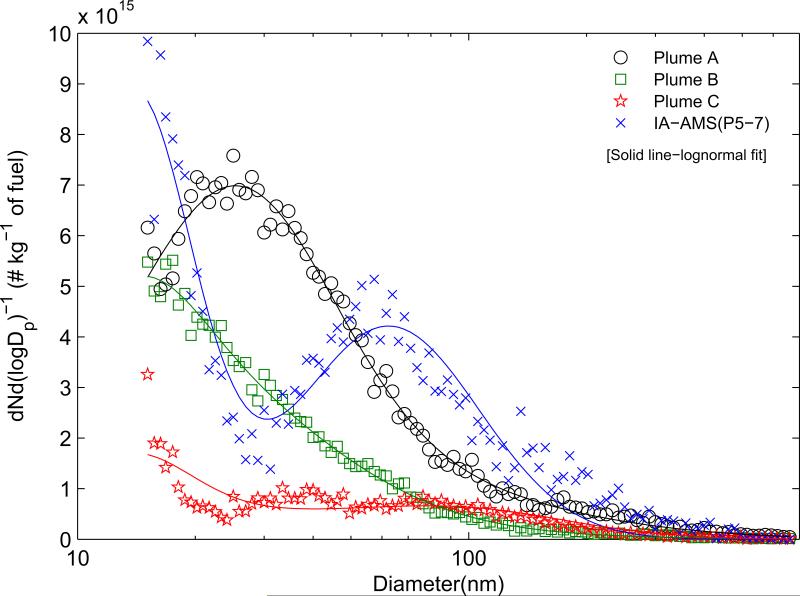

3.6.1 Particle number

The average EFPN for particles exceeding 3 nm in diameter was 3.5×1016 kg−1. EFPN and EFSO2 were positively correlated (R2 = 0.99), suggesting new particle formation in the plume was associated with high SO2 concentrations. This EFPN for tire burning is the first such value reported in the literature and is comparable in magnitude to EFPN reported for light and heavy duty vehicles under cruise and acceleration conditions, which ranged 0.7-2.7 x 1016 particles kg−1 (Kittelson et al., 2006; Lee and Stanier, 2014), and for biomass burning, ranging 3.1-5.9 ×1016 particles kg−1 (Akagi et al., 2011; Janhaell et al., 2010).

Figure 6 shows size-resolved EFPN calculated from three June 1 plume transects at distances of 1.3, 3.2, and 4.8 km downwind from the landfill (marked as plumes A-C, respectively) and averaged measurements from IA-AMS. All size-resolved EFPN demonstrate an enhanced nuclei mode at 15-20 nm and an Aitken mode at 50-60 nm. The contribution of accumulation mode (100-2500 nm) on a number basis is relatively small. The size-resolved EFPN are highly variable and reflect differences in plume aging, nucleation, and growth.

Figure 6.

Size-resolved particle number emission factors for plume transects: A-C were measured June 1 at distances of 1.3, 3.2, and 4.8 km from the landfill, while the other size-resolved EF is averaged from measurements at IA-AMS.

3.6.2 PM2.5, EC, and SO2 emission factors

EFPM2.5 ranged 0.7-14.0 g kg−1 across the ten plume intercepts, averaging 5.4±5.4 g kg−1. The absolute value of EFPM2.5 is subject to uncertainty associated with the conversion of PN to PM2.5 mass as described in the Supplemental Information. Across the plume transects, EFPM2.5 varied considerably, as indicated by the large standard deviations in Table 1, coefficients of variance of ~1, and the wide range of individual EFPM2.5 in Table S1. Since EF vary with combustion conditions, including oxygen availability, temperature, mechanical mixing, and smothering, the variability between plume transects in this study reflects the evolving conditions of the Iowa City tire fire with respect to duration of burn, meteorological conditions, and firefighting efforts. The EFPM2.5 observed in this study is more than an order of magnitude lower than the EFTSP reported by Lemieux and Ryan (1993) at 65 -105 g kg−1 . The excess of particulate emissions observed in laboratory versus field studies may be due to different combustion efficiencies, leading to greater particulate emissions; insufficient dilution in the laboratory to allow equilibration of gas-particle partitioning before sample collection; or differences in particle size cuts, if laboratory studies included coarse particles that were lofted by thermal convection.

The EFEC determined for the uncontrolled, open burning of tires is 2.4 g kg−1. In comparison to EFEC from open cooking (0.20-0.67 g kg−1), garbage fires (0.28-0.92 g kg−1), and brick kilns (0.60-1.50 g kg−1) (Christian et al., 2010), tire burning emits a significantly larger amount of EC.

The average EFSO2 from the open-burning of tires was 7.1 g kg−1. This value is a factor of 4-5 lower than EFSO2 reported by Levendis et al. (1996) at 35 g kg−1 and Stockwell et al. (2014) at 28 g kg−1, and an order of magnitude greater than the than EFSO2 of 0.1-0.8 g kg−1 reported by Shakya et al. (2008), all of which correspond to laboratory studies. Deviations in EFSO2 reflect the varying sulfur content of different types of tires and fuels and may also be influenced by sample collection and analysis methods.

3.6.3 PAH emission factors

EFPAH for the nineteen quantified species averaged 56±44 mg kg−1 (Table 1). The estimated EFB[a]P is 2.3 mg kg−1 and, near to EFB[a]P of 2.2 mg kg−1 reported by Levendis et al. (1996) for PAH emitted by burning tire crumb in a vertical furnace with a 33% excess of fuel relative to oxygen. This magnitude of EFB[a]P suggests that the Iowa City landfill fire was moderately oxygen-limited. The EFB[a]P observed in ambient PM2.5 in this study is significantly lower than the summed gas plus particle EFB[a]P of 113 mg kg−1 reported by Lemieux and Ryan (1993), highlighting the significant impact of sample collection, combustion efficiency, and dilution ratio on this value. Compared to PAH emissions from fireplace combustion of wood (Schauer et al., 2001), tires burning emitted significantly higher amounts of particle-phase PAH.

4. Implications for air quality management and future research

The study of emissions from the uncontrolled open burning of shredded tires at the Iowa City landfill in 2012 provides a better qualitative and quantitative understanding of this source. The EF reported herein for PM2.5, SO2, EC, and PAH from tire combustion are representative of uncontrolled, open-burning conditions and are recommended for use in modeling the emissions from large-scale, uncontrolled tire combustion. The EFPN reported in this work is the first in the literature for this source type; however, EFPN are sensitive to meteorological and atmospheric processing (e.g. nucleation) as well as sampling configuration, and will consequently be more variable than mass-based emission factors. Accurate modeling of the gaseous and particulate emissions downwind of a tire fire will aid air quality managers and public health officials in assessing the public health risk posed by the fire and responding to the event. Furthermore, the determination of EF for air pollutants per mass of tire burned allows for the assessment of the relative risks posed by the smoke constituents, as discussed by Singh et al. (co-submitted).

Future research on the emissions of tire combustion should address the remaining gaps in understanding this source, including direct measurement of EFPM2.5 (as opposed to using instruments to infer mass from particle counts) and EFOC. Particle phase and semi-volatile PAH should be collected in series, using combined filter and XAD samplers. To determine EF quantitatively, continuous measurements of CO2 and CO are needed; continuous measurement of SO2 is encouraged. Further studies of the open burning of tires are needed to better understand the variability and evolution of gaseous and particulate emissions from tire combustion. The absence of metals in plume-impacted PM10 in Iowa City warrants investigation into the extent to which metals are emitted from tire fires as a function of particle size. Emissions may change as the composition of tires and methods for fighting tire fires evolve. Furthermore, differences in EF due to sample collection methods, local meteorological conditions, gas-particle partitioning, and secondary aerosol formation could also be investigated. Finally, a risk assessment study for the costs and benefits of using tires as major components of landfill liners should be conducted, with fire-fighting, clean-up, and environmental and health impacts in mind.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Emissions from uncontrolled, open-burning of tires were characterized.

Emission factors for SO2, particle number, PM2.5, EC, and 19 PAH were determined.

Metals (Zn, Fe, Pb) were not enhanced in PM10 4.2 km downwind of the fire.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Keri Hornbuckle for access to IA-AMS, University of Iowa Facilities Management for maintaining the site, and undergraduate researchers Allaa Hassanein, Andrew Hesselink, Tony Nguyen, Sean Staudt, and Jim Vojahosky for preparing and deploying sampling equipment. We also thank Walker Williams for assistance with sample collection on Black Diamond Road and the Operator Performance Laboratory at the University of Iowa for help with the plume transect study. Funding was provided by the University of Iowa Environmental Health Sciences Research Center through the National Institutes of Health (NIH, P30 ES05605).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akagi SK, Yokelson RJ, Wiedinmyer C, Alvarado MJ, Reid JS, Karl T, Crounse JD, Wennberg PO. Emission factors for open and domestic biomass burning for use in atmospheric models. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 2011;11:4039–4072. [Google Scholar]

- Bi XH, Sheng GY, Peng P, Chen YJ, Fu JM. Size distribution of n-alkanes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in urban and rural atmospheres of Guangzhou, China. Atmospheric Environment. 2005;39:477–487. [Google Scholar]

- Christian TJ, Yokelson RJ, Cardenas B, Molina LT, Engling G, Hsu SC. Trace gas and particle emissions from domestic and industrial biofuel use and garbage burning in central Mexico. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 2010;10:565–584. [Google Scholar]

- Demarini DM, Lemieux PM, Ryan JV, Brooks LR, Williams RW. Mutagenicity and Chemical-Analysis of Emissions from the Open Burning of Scrap Rubber Tires. Environmental Science & Technology. 1994;28:136–141. doi: 10.1021/es00050a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant JL, Busby WF, Lafleur AL, Penman BW, Crespi CL. Human cell mutagenicity of oxygenated, nitrated and unsubstituted polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons associated with urban aerosols. Mutation Research-Genetic Toxicology. 1996;371:123–157. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1218(96)90103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPA, U.S. Sampling of Ambient Air for PM10 using an Anderson Dichotomous Sampler. Compendium Method IO-2.2. 1999 http://www.epa.gov/ttnamti1/files/ambient/inorganic/mthd-2-2.pdf.

- EPA, U.S. [January 14, 2014];Air Quality System Data Mart [internet database] 2014 available at http://www.epa.gov/ttn/airs/aqsdatamart.

- Fitzpatrick EM, Jones JA, Pourkashanian M, Ross AB, Williams A, Bartle KD. Mechanistic Aspects of Soot Formation from the Combustion of Pine Wood. Energy & Fuels. 2008;22:3771–3778. [Google Scholar]

- Giere R, LaFree ST, Carleton LE, Tishmack JK. Environmental impact of energy recovery from waste tires. Section Title: Waste Treatment and Disposal. 2004;236:475–498. [Google Scholar]

- Janhaell S, Andreae MO, Poeschl U. Biomass burning aerosol emissions from vegetation fires: particle number and mass emission factors and size distributions. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 2010;10:1427–1439. [Google Scholar]

- Jayarathne T, Stockwell CE, Yokelson RJ, Nakao S, Stone EA. Emissions of fine particle fluoride from biomass burning. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48:12636–12644. doi: 10.1021/es502933j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittelson DB, Watts WF, Johnson JP. On-road and laboratory evaluation of combustion aerosols - Part 1: Summary of diesel engine results. Journal of Aerosol Science. 2006;37:913–930. [Google Scholar]

- Lee SR, Stanier CO. Research Report. Vol. 179. Boston, MA: 2014. Development and Application of an Aerosol Screening Model for Size-Resolved Urban Aerosols, Health Effects Institute. www.healtheffects.org. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemieux PM, Lutes CC, Santoianni DA. Emissions of organic air toxics from open burning: a comprehensive review. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science. 2004;30:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lemieux PM, Ryan JV. Characterization of Air Pollutants Emitted from a Simulated Scrap Tire Fire. Journal Of The Air & Waste Management Association. 1993;43:1106–1115. [Google Scholar]

- Levendis YA, Atal A, Carlson J, Dunayevskiy Y, Vouros P. Comparative study on the combustion and emissions of waste tire crumb and pulverized coal. Environmental Science & Technology. 1996;30 [Google Scholar]

- Oros DR, Simoneit BRT. Identification and emission rates of molecular tracers in coal smoke particulate matter. Fuel. 2000;79:515–536. [Google Scholar]

- Quek A, Balasubramanian R. Liquefaction of waste tires by pyrolysis for oil and chemicals-A review. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis. 2013;101:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Reisman JI. Air Emissions from Scrap Tire Combustion (EPA-600/R-97-115) 1997.

- RMA Rubber Manufacturer's Association “2011 U.S. Scrap Tire Market Summary”. 2013 www.rma.org.

- Schauer JJ, Kleeman MJ, Cass GR, Simoneit BRT. Measurement of emissions from air pollution sources. 3. C-1-C-29 organic compounds from fireplace combustion of wood. Environmental Science & Technology. 2001;35:1716–1728. doi: 10.1021/es001331e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidelt S, Muller-Hagedorn A, Bockhorn H. Description of tire pyrolysis by thermal degradation behaviour of main components. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis. 2006;75:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shakya PR, Shrestha P, Tamrakar CS, Bhattarai PK. Studies on potential emission of hazardous gases due to uncontrolled open-air burning of waste vehicle tyres and their possible impacts on the environment. Atmospheric Environment. 2008;42:6555–6559. [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Spak SN, Stone EA, Downard J, Bullard R, Pooley M, Kostle PA, Mainprize MW, Wichman MD, Peters T, Beardsley D, Stanier CO. co-submitted. Uncontrolled Combustion of Shredded Tires in a Landfill - Part 2: Population Exposure, Public Health Response, and an Air Quality Index for Urban Fires. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Slowik JG, Stainken K, Davidovits P, Williams LR, Jayne JT, Kolb CE, Worsnop DR, Rudich Y, DeCarlo PF, Jimenez JL. Particle morphology and density characterization by combined mobility and aerodynamic diameter measurements. Part 2: Application to combustion-generated soot aerosols as a function of fuel equivalence ratio. Aerosol Science And Technology. 2004;38:1206–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanov SB, Biocanin RR, Vojinovic Miloradov MB, Sokolovic SM, Ivankovic D. Ecological modeling of pollutants in accidental fire at the landfill waste. Therm. Sci. 2013;17:903–913. [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell CE, Yokelson RJ, Kreidenweis SM, Robinson AL, DeMott PJ, Sullivan RC, Reardon J, Ryan KC, Griffith DWT, Stevens L. Trace gas emissions from combustion of peat, crop residue, domestic biofuels, grasses, and other fuels: configuration and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) component of the fourth Fire Lab at Missoula Experiment (FLAME-4). Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 2014;14:9727–9754. [Google Scholar]

- Stone EA, Nguyen TT, Pradhan BB, Dangol PM. Assessment of biogenic secondary organic aerosol in the Himalayas. Environ. Chem. 2012;9:263–272. [Google Scholar]

- Sun P, Blanchard P, Brice KA, Hites RA. Trends in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon concentrations in the Great Lakes atmosphere. Environmental Science & Technology. 2006;40:6221–6227. doi: 10.1021/es0607279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turpin BJ, Lim HJ. Species contributions to PM2.5 mass concentrations: Revisiting common assumptions for estimating organic mass. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2001;35:602–610. [Google Scholar]

- Unapumnuk K, Lu MM, Keener TC. Carbon distribution from the pyrolysis of tire- derived fuels. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006;45:8757–8764. [Google Scholar]

- Virginia Department of Environmental Quality Waste Tire Pile Cleanups. 2014 www.deq.virginia.gov.

- Wang Z, Li K, Lambert P, Yang C. Identification, characterization and quantitation of pyrogenic polycylic aromatic hydrocarbons and other organic compounds in tire fire products. Journal of Chromatography A. 2007:1139. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.10.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokelson RJ, Griffith DWT, Ward DE. Open-path Fourier transform infrared studies of large-scale laboratory biomass fires. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres (1984-2012) 1996;101:21067–21080. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YX, Schauer JJ, Zhang YH, Zeng LM, Wei YJ, Liu Y, Shao M. Characteristics of particulate carbon emissions from real-world Chinese coal combustion. Environmental Science & Technology. 2008;42:5068–5073. doi: 10.1021/es7022576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng M, Hagler GSW, Ke L, Bergin MH, Wang F, Louie PKK, Salmon L, Sin DWM, Yu JZ, Schauer JJ. Composition and sources of carbonaceous aerosols at three contrasting sites in Hong Kong. Journal Of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres. 2006;111 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.