Abstract

Addition of an anionic donor to an MnV(O) porphyrinoid complex causes a dramatic increase in 2-electron oxygen-atom-transfer (OAT) chemistry. The 6-coordinate [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− was generated from addition of Bu4N+CN− to the 5-coordinate MnV(O) precursor. The cyanide-ligated complex was characterized for the first time by Mn K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and gives Mn–O=1.53 Å, Mn–CN=2.21 Å. In combination with computational studies these distances were shown to correlate with a singlet ground state. Reaction of the CN− complex with thioethers results in OAT to give the corresponding sulfoxide and a 2e−-reduced MnIII(CN)− complex. Kinetic measurements reveal a dramatic rate enhancement for OAT of approximately 24 000-fold versus the same reaction for the parent 5-coordinate complex. An Eyring analysis gives ΔH≠=14 kcal mol−1, ΔS≠=−10 cal mol−1 K−1. Computational studies fully support the structures, spin states, and relative reactivity of the 5- and 6-coordinate MnV(O) complexes.

Keywords: manganese, oxygen-atom-transfer, porphyrinoids, spin state reactivity, sulfoxidation

Determining the factors that control the inherent reactivity of metal–oxo complexes is of critical importance for understanding the function of both heme and nonheme metalloenzymes. Heme enzymes can be differentiated by the protein-derived axial ligand which binds the heme cofactor through one of the axial positions of the central metal ion. For example, peroxidases employ a histidine,[1] catalases employ a tyrosinate,[2] and Cytochrome P450s (CYP450) utilize a cysteinate ligand to coordinate to the iron center.[3] It has been suggested that the anionic Cys donor in CYP450 plays an important role in modulating the electronic features and reactivity of the high-valent iron–oxo species FeIV(O)(porph+.)(Cys) (Compound-I: Cpd-I), which is the critical intermediate responsible for substrate oxidation.[3]

The influence of axial ligands on the reactivity of synthetic Cpd-I analogues has been examined for several reaction classes, including alkyl and arene hydroxylation, and alkene epoxidation.[4] These previous studies have shown that both anionic and neutral donors have had a significant influence on the reactivity of the Cpd-I analogues, with reaction rates typically being influenced by 1–3 orders of magnitude. However, the fundamental origins of these axial ligand effects are still not well understood, and some of the explanations that were offered provide conflicting conclusions. The analogous influence of axial ligands on high-valent Mn–oxo complexes has been less well studied, in part because Cpd-I analogues MnIV(O)(porph+.), or the equivalent MnV(O)(porph0), are typically highly unstable and difficult to observe.[5], [6] We previously examined axial ligand effects on a high-valent manganese(V)–oxo complex, MnV(O)(TBP8Cz), [TBP8Cz=octakis(p-tert-butylphenyl)corrolazinato3−], which is a rare example of a stable and isolable MnV(O) porphyrinoid species.[7], [8] Reactivity towards C–H substrates was examined, and dramatic increases in hydrogen-atom transfer (HAT) rates were observed upon addition of anionic donors (e.g., F−, CN−). It was concluded that the anionic donors were weakly coordinating trans to the oxo ligand, and based on density functional theory (DFT) calculations, the axial ligands likely caused an increase in the basicity of the incipient [MnIV(OH)]– intermediate and a strengthening of the O–H bond. This thermodynamic influence, in turn, led to a greater overall driving force for HAT, which correlated with a lowering of the reaction barrier.[8a] An alternative explanation for the HAT reactivity based on additional DFT calculations was recently offered, and involves spin cross-over from the low-spin (ls) singlet (S=0) state for [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]– to a high-spin (hs) triplet (S=1) state.[9]

In this work we provide novel insights regarding the axial ligand effects on the OAT reactivity of a high-valent MnV(O) complex. Addition of the mono-anionic donor CN− leads to the formation of the 6-coordinate complex [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]−. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) measurements provided structural parameters and an oxidation state assignment for this complex. The oxygen-atom-transfer (OAT) reactivity of this complex was examined for thioether substrates, and a dramatic rate acceleration of approximately 24 000-fold over the 5-coordinate parent complex was observed. This increase in reactivity is orders of magnitude larger than that seen in similar studies on the axial ligand influence in either heme- or nonheme high-valent metal–oxo complexes of biological relevance.[4], [5], [10] Computational (DFT) methods led to optimized geometries that were in good agreement with the XAS studies, and these experimentally validated computational results help shed light on the ground spin states for the MnV(O) complexes. Further DFT calculations on the OAT reaction profiles fully support the experimentally observed increase in reaction rate.

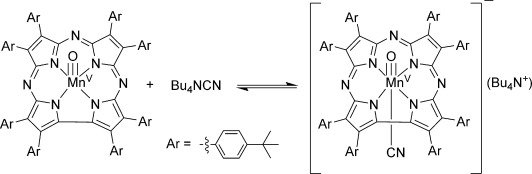

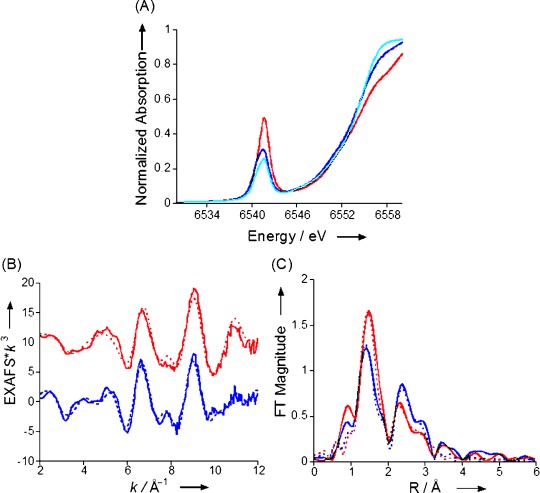

In an earlier study we showed that addition of excess Bu4N+CN− to MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) in CH2Cl2 led to a large increase in HAT reactivity.[8a] The UV/Vis spectrum of the MnV(O) complex is not sensitive to addition of CN−, but LDI-MS (neg. mode) showed clear evidence for a complex matching the formula [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]−, consistent with formation of a 6-coordinate complex as seen in Scheme 1. However, direct structural information on the cyanide-ligated complex was lacking, in part due to the instability of this complex. We now report the structural characterization of [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− by XAS. The Mn K-edge XAS spectra of MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) and [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− (prepared by addition of 10 and 100 equivalents of Bu4N+CN−) are shown in Figure 1 a. All three spectra are consistent with a MnV oxidation state assignment, based on the approximately 6553 eV position of the rising edge. Upon addition of CN−, the edge shifts by about 0.3 eV to lower energy, but not enough to suggest reduction to MnIV. Most notably, upon addition of CN−, the pre-edge remains at high energy (∼6542 eV), but the pre-edge intensity decreases relative to the 5-coordinate MnV–oxo complex. These data are consistent with formation of a 6-coordinate MnV–oxo species. Coordination of a trans axial CN− ligand would move the Mn further into the Cz plane, decreasing the amount of metal 3d–4p mixing, and thus decreasing the observed pre-edge intensity.

Scheme 1.

Formation of 6-coordinate [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]−.

Figure 1.

A) Comparison of the normalized Mn K-edge XAS data for MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) with zero (red), 10 (dark blue) and 100 (light blue) equivalents of added Bu4N+CN− in benzonitrile. B) EXAFS data (solid lines) and fits (dashed lines) for MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) (red) and MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)+100 equivalents of Bu4N+CN− (blue). C) The corresponding FTs (solid) and fits (dashed).

Figure 1 b shows the EXAFS data for MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) and [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− (at 100-fold excess of Bu4N+CN−) with the corresponding Fourier transforms (FTs) presented in Figure 1 c. These data clearly show that addition of CN− introduces a structural perturbation at the Mn site. The overall beat pattern of the EXAFS is altered and the relative intensity of the FT peaks is also modified. Based on our EXAFS fits, these trends are best interpreted as resulting from direct coordination of CN− to MnV(O)(TBP8Cz). The 5-coordinate MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) is best fit by inclusion of one Mn–O vector at 1.54 Å and 4 Mn–N(Cz) interactions at 1.87 Å, and multiple scattering (MS) interactions from the Cz ring are needed to fit the outer-shell contributions to the FT (see the Supporting Information for full fit parameters). These data match well with an earlier report, and were repeated here for the direct comparison with [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]−.[8b] For [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]−, the data are best fit by one Mn–O at 1.53 Å, four Mn–N(Cz) interactions at 1.87 Å, and a 2.21 Å Mn–C/N interaction consistent with a coordinated CN−. The coordination of CN− is further supported by the increase in the outer-shell FT amplitude (despite the decrease in the first shell amplitude). The increase in outer-shell multiple scattering intensity at approximately 2.5 Å is attributed to the presence of linear scattering from the nitrogen of coordinated CN−, in addition to Cz ring scattering.

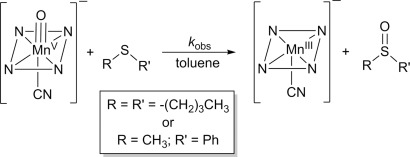

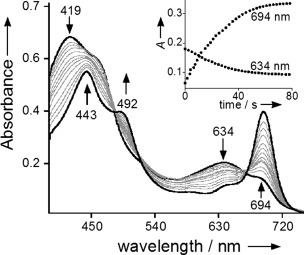

Reactivity studies with the cyanide complex [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− were undertaken to determine the influence of anionic axial donors on OAT reactivity. This species was allowed to react with dibutyl sulfide (DBS) in toluene at 25 °C (Scheme 2). This reaction was monitored by UV/Vis spectroscopy as shown in Figure 2, and exhibited rapid isosbestic conversion of [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− to a species with a split Soret band at 443 and 492 nm, and a Q-band at 694 nm. This final spectrum can be assigned to the 2e−-reduced MnIII complex [MnIII(TBP8Cz)(CN)]−, as confirmed by independent generation. The related chloride-ligated complex (Et4N)[MnIII(TBP8Cz)(Cl)] also exhibits a similar split Soret band and has been crystallographically characterized.[8b],[8c] The reaction was complete within a few minutes, as compared to several hours for the reaction of the 5-coordinate MnV(O) complex with the same substrate at much larger concentrations.[8d] These data clearly demonstrate that addition of CN− leads to a large increase in reactivity towards DBS.

Scheme 2.

Reaction of [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− with thioether substrates.

Figure 2.

UV/Vis spectral changes (0–80 s) for the reaction of [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− (11 μm) (419, 634 nm) with excess DBS (500 equiv) to give [MnIII(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− (443, 492, 694 nm) in toluene at 25 °C. Inset: changes in absorbance versus time for the growth of [MnIII(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− (694 nm) and the decay of [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− (634 nm).

A second substrate, thioanisole (PhSMe), was tested to examine the generality of the CN− influence over OAT reactivity with thioethers, and provides a convenient substrate for measuring quantitative yields of sulfoxide product by GC-FID. The reaction between PhSMe and [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− led to the expected conversion of the starting material to the cyanide-ligated MnIII product, and the reaction mixture was analyzed directly by GC-FID. The anticipated methyl phenyl sulfoxide was obtained in high yield (84 %; Scheme 2). Labeling of the terminal oxo ligand with 18O from H218O, followed by reaction with PhSMe led to 71 % incorporation of 18O in the final sulfoxide product as seen by GC-MS. These data show that [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− carries out direct OAT to thioethers to give the 2e−-oxidized sulfoxide as the major product.

The kinetics of OAT for [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− with DBS as substrate were quantitatively analyzed for comparison with the previously examined 5-coordinate MnV(O) complex (second-order rate constant of 3.8×10−4 m−1 s−1 for DBS).[8d] Reactions were run under pseudo-first-order conditions (175–750 equiv of DBS) and monitored by UV/Vis. Isosbestic behavior was observed as seen in Figure 2 for all concentrations of DBS, and plots of absorbance versus time for the decay of the [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− complex (634 nm) and the appearance of the [MnIII(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− complex (694 nm) were well-fit by a single exponential model. The resulting fits yielded the pseudo-first-order rate constants kobs, and plots of kobs at 694 or 634 nm versus [DBS] were linear. The kinetics are consistent with the overall second-order rate law: –d[MnV(O)(X)]/dt=k[MnV(O)(X)][DBS], and the slope of the best-fit line of the second-order plot for 694 nm gives k=9.2(±0.3) m−1 s−1. A comparison of the rate constant for the CN− complex with that reported for the 5-coordinate MnV(O) complex reveals a dramatic rate enhancement of 24 000-fold for OAT with DBS as substrate. This change can be compared to recent work by Fujii, which showed that modifying the nature of the axial ligand in an iron–oxo porphyrin Cpd-I analogue resulted in a 30-fold difference in OAT rate.[4a]

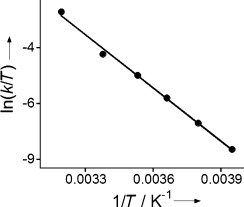

To obtain further information on the mechanism of OAT for [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− and DBS, a temperature-dependent study of the rate constants (−20 to 40 °C) was performed. An Eyring plot of ln(k/T) versus 1/T (Figure 3) shows a linear dependence that yields the activation parameters listed in Table 1. The activation parameters for the 5-coordinate MnV(O) complex, and the one-electron-oxidized analogue MnV(O)(TBP8Cz+.), are included in Table 1 for comparison, measured previously for the same substrate and solvent.[8d] The enthalpy of activation for the cyanide-ligated complex is lower than that found for the 5-coordinate complex, while the ΔS≠ is more positive. These differences both contribute to a lowering of the reaction barrier for the CN− complex. The overall negative ΔS≠ value for the CN− complex is consistent with a bimolecular mechanism, while the unusually large and negative ΔS≠ seen for the positively charged MnV(O)(TBP8Cz+.) is not observed for the negatively charged CN− complex. From these data, it appears that the addition of CN− to the MnV(O) complex does not cause a significant change in the mechanism of OAT, but does induce a significant lowering of the reaction barrier through a combination of both enthalpic and entropic effects.

Figure 3.

Eyring plot for the reaction of [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− (11.5 μm) with DBS (21 mm) in toluene from −20 to 40 °C.

Table 1.

Kinetic and activation parameters for OAT reactions with dibutyl sulfide.

| MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)[a] | MnV(O)(TBP8Cz+.)[a] | [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− | |

|---|---|---|---|

| k[b] | 3.8×10−4[c] | (6.2±0.2)×10−3 | 9.2±0.3 |

| ΔH≠[d] | 16±1 | 7.0±0.8 | 14±0.4 |

| ΔS≠[e] | −20±4 | −45±3 | −10±0.8 |

| ΔG≠[d] | 22±2[f] | 20±2[f] | 17±0.5[f] |

From Ref. [8d].

Values in m−1 s−1 at 298 K.

Extrapolated from a ln(k/T) versus 1/T plot.

Values in kcal mol−1.

Values in cal K−1 mol−1.

At 298 K.

Computational studies were employed to gain further insight into the structure and reactivity of [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]−. Previous calculations on the 5- and 6-coordinate MnV(O) complexes[8d] utilized an abbreviated Cz core with hydrogen atoms on all β-carbon positions (H8Cz) for computational convenience. To determine the influence of the peripheral substituents on the computational results, a set of DFT calculations with H8Cz, octamethyl (Me8Cz), and octamethylphenyl ((MePh)8Cz) corrolazine ligands were performed for both the MnV(O) and [MnV(O)(CN)]− complexes. Three different density functional methods were also employed for all complexes, providing a comprehensive DFT analysis of optimized geometries and spin ground states.[11] Although a certain degree of fluctuation in spin state ordering and relative energies is obtained between the different DFT methods, the majority of calculations give a singlet spin ground state. The Mn–O bond is shortest in the closed-shell singlet spin ground state; with Mn–O=1.55 Å at B3LYP-D3/SDD/6-31G(d) level of theory, as expected for a low-spin d2 ion with both π*(MnO) orbitals unoccupied. The excited triplet spin states for the [MnV(O)(CN)]− complexes exhibit different electronic configurations depending upon which functional is employed. For B3LYP and M06, spin densities indicate an electronic configuration that can be best described as a hs-MnIV(oxyl radical), whereas BP86 results in a configuration closer to a hs-MnV (d1π*1 state). The oxyl radical states give highly elongated Mn–O bonds (1.80–1.82 Å), and although the hs-MnV state has a shorter distance of approximately 1.67 Å, all of these Mn–O distances are significantly longer than that observed by EXAFS. Thus the DFT-optimized geometries for the singlet spin states provide the best match for the structure obtained by EXAFS. Time-dependent DFT calculations on the singlet states for the 5- and 6-coordinate complexes also reproduce the qualitative trend in the lowering of the pre-edge peak intensity for the CN− complex. From our combined spectroscopic and computational studies, we conclude that [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− has a low-spin singlet ground state. This state is the same as that seen for the five-coordinate MnV(O) complex, and these data indicate that CN− ligation does not perturb the spin ground state.

To further establish the electronic ground state and orbital occupations of the lowest energy singlet and triplet spin states of [MnV(O)(H8Cz)(CN)]− we ran a series of CASSCF-NEVPT2 calculations on the B3LYP optimized geometries. We find a singlet spin ground state with the triplet higher in energy by 13 kcal mol−1. This singlet–triplet energy gap is considerably larger than that found from DFT, and indicates that reactivity on the triplet spin state surface is highly unlikely. Interestingly, the NEVPT2 calculated triplet spin state gives spin densities of 2.1 on Mn and −0.1 on O, whereas the DFT result gives spin densities of about 3 on Mn and −1 on O instead. These results implicate that the DFT calculated triplet spin state may be a spurious artefact that has no realistic electronic structure. Further studies are needed to establish the exact nature of the triplet spin state and its reactivity, and therefore we will focus on the singlet spin state only.

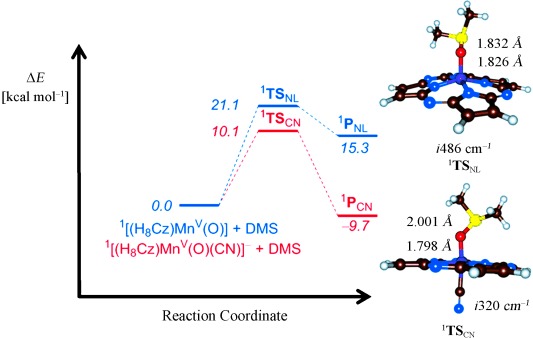

To gain insight into the mechanism of OAT, we then did a set of DFT studies on dimethyl sulfide sulfoxidation by [MnV(O)(H8Cz)(L)] with L=no ligand (NL) or CN−. Figure 4 shows the potential energy profile and rate determining transition state geometries for the sulfoxidation reaction. Similar to previous studies, sulfoxidation is a concerted reaction process with a single S–O bond formation transition state, TSL.[8d], [12] The enthalpy of activation (with solvent corrections included) is lowered dramatically upon addition of an axial ligand, in good agreement with the large rate enhancement observed for the 6-coordinate complex. A close inspection of the transition state geometries reveals that 1TSSO,CN is earlier on the potential energy surface than 1TSSO,NL with a longer S–O distance and shorter Mn–O distance. Often early transition states correspond to lower energetic barriers than late transition states.[13] The lowering of the barrier may also be related to the stabilization of the MnIII product via coordination of CN−. This computational result is in agreement with Fujii’s recent analysis that the increase in oxidative reactivity of Cpd-I analogues with different axial ligands can be ascribed to the energetics of axial ligand stabilization of the FeIII(porph) products.[4] Future experimental and computational work is warranted to determine the origins of the lowering of the reaction barrier in Figure 4.4

Figure 4.

Potential energy profile calculated at UB3LYP/BS2 level of theory for OAT reactions involving [MnV(O)(H8Cz)] and [MnV(O)(H8Cz)(CN)]− with DMS. Energies (ΔE+ZPE+Esolv) are given. Also shown are optimized transition state geometries (right-hand side) with bond lengths in angstroms and the imaginary mode in wave numbers.

Our combined experimental and computational studies demonstrate that the addition of an anionic axial ligand to an MnV(O) porphyrinoid complex results in a remarkable increase in OAT reaction rate with thioether substrates. The XAS data and DFT calculations indicate that the singlet ground state, and associated short Mn–O distance, for the 5-coordinate MnV(O) complex does not change upon addition of an anionic axial ligand. The OAT mechanism appears to be a concerted 2e− process, leading to the smooth formation of [MnIII(CN)]− and sulfoxide products. The DFT studies reproduce well the observed increase in reaction rate by a significant stabilization of the reaction barrier for the 1[MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− complex. Future studies will be aimed at determining the generality of the axial ligand effects on OAT reactivity for MnV(O) complexes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NSF (CHE0909587 and CHE121386 to D.P.G.) and the NIH (GM101153 to D.P.G). BBSRC is acknowledged for a studentship to M.G.Q. and the National Service of Computational Chemistry Software (NSCCS) is thanked for cpu time to S.d.V. Portions of this research were carried out at SSRL, a national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the US DOE, BES. We thank Prof. K. D. Karlin for instrumentation use. The Kirin cluster at Johns Hopkins University School of Arts and Sciences is thanked for cpu time to T.Y.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/chem.201404349.

References

- [1]a.Battistuzzi G, Bellei M, Bortolotti CA, Sola M. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2010;500:21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [1]b.Poulos TL. In: Handbook of Porphyrin Science. Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing; 2013. pp. 45–109. [Google Scholar]

- [1]c.Bewley KD, Ellis KE, Firer-Sherwood MA, Elliott SJ. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2012;1827:938–948. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]a.Díaz A, Loewen PC, Fita I, Carpena X. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012;525:102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]b.Alfonso-Prieto M, Vidossich P, Rovira C. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012;525:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]a.Groves JT. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:89–91. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]b.Green MT. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2009;13:84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]c.Green MT, Dawson JH, Gray HB. Science. 2004;304:1653–1656. doi: 10.1126/science.1096897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]d.Yosca TH, Rittle J, Krest CM, Onderko EL, Silakov A, Calixto JC, Behan RK, Green MT. Science. 2013;342:825–829. doi: 10.1126/science.1244373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]e.Poulos TL, Finzel BC, Howard AJ. J. Mol. Biol. 1987;195:687–700. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]f.Denisov IG, Makris TM, Sligar SG, Schlichting I. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2253–2277. doi: 10.1021/cr0307143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]a.Takahashi A, Yamaki D, Ikemura K, Kurahashi T, Ogura T, Hada M, Fujii H. Inorg. Chem. 2012;51:7296–7305. doi: 10.1021/ic3006597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]b.Gross Z. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1996;1:368–371. [Google Scholar]

- [4]c.Kang Y, Chen H, Jeong YJ, Lai W, Bae EH, Shaik S, Nam W. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:10039–10046. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]d.Takahashi A, Kurahashi T, Fujii H. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:2614–2625. doi: 10.1021/ic802123m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]e.Song WJ, Ryu YO, Song R, Nam W. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2005;10:294–304. doi: 10.1007/s00775-005-0641-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]f.Kamachi T, Kouno T, Nam W, Yoshizawa K. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006;100:751–754. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]g.Pan ZZ, Zhang R, Newcomb M. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006;100:524–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]h.Hessenauer-Ilicheva N, Franke A, Meyer D, Woggon WD, van Eldik R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12473–12479. doi: 10.1021/ja073266f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]i.Hessenauer-Ilicheva N, Franke A, Meyer D, Woggon WD, van Eldik R. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:2941–2959. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]a.Balcells D, Raynaud C, Crabtree RH, Eisenstein O. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:10090–10099. doi: 10.1021/ic8013706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]b.Jin N, Lahaye DE, Groves JT. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:11516–11524. doi: 10.1021/ic1015274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]c.Crestoni ME, Fornarini S, Lanucara F. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:7863–7866. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]d.Solati Z, Hashemi M, Hashemnia S, Shahsevani E, Karmand Z. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2013;374:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- [5]e.Jin N, Ibrahim M, Spiro TG, Groves JT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12416–12417. doi: 10.1021/ja0761737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]a.Marla SS, Lee J, Groves JT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:14243–14248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]b.Jin N, Groves JT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:2923–2924. [Google Scholar]

- [6]c.Song WJ, Seo MS, George SD, Ohta T, Song R, Kang MJ, Tosha T, Kitagawa T, Solomon EI, Nam W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:1268–1277. doi: 10.1021/ja066460v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]d.Nam W, Kim I, Lim MH, Choi HJ, Lee JS, Jang HG. Chem. Eur. J. 2002;8:2067–2071. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20020503)8:9<2067::AID-CHEM2067>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]e.Zhang R, Horner JH, Newcomb M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6573–6582. doi: 10.1021/ja045042s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]a.Kumar A, Goldberg I, Botoshansky M, Buchman Y, Gross Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:15233–15245. doi: 10.1021/ja1050296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]b.Liu HY, Lai TS, Yeung LL, Chang CK. Org. Lett. 2003;5:617–620. doi: 10.1021/ol027111i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]c.Liu HY, Yam F, Xie YT, Li XY, Chang CK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:12890–12891. doi: 10.1021/ja905153r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]a.Prokop KA, de Visser SP, Goldberg DP. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:5091–5095. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2010;122:5217–5221. [Google Scholar]

- [8]b.Lansky DE, Mandimutsira B, Ramdhanie B, Clausen M, Penner-Hahn J, Zvyagin SA, Telser J, Krzystek J, Zhan R, Ou Z, Kadish KM, Zakharov L, Rheingold AL, Goldberg DP. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:4485–4498. doi: 10.1021/ic0503636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]c.Lansky DE, Narducci Sarjeant AA, Goldberg DP. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:18214–8217. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2006;118:8394–8397. [Google Scholar]

- [8]d.Prokop KA, Neu HM, de Visser SP, Goldberg DP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:15874–15877. doi: 10.1021/ja2066237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]e.Leeladee P, Baglia RA, Prokop KA, Latifi R, de Visser SP, Goldberg DP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:10397–10400. doi: 10.1021/ja304609n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Janardanan D, Usharani D, Shaik S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:4421–4425. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2012;124:4497–4501. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sastri CV, Lee J, Oh K, Lee YJ, Lee J, Jackson TA, Ray K, Hirao H, Shin W, Halfen JA, Kim J, Que L, Jr, Shaik S, Nam W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:19181–19186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709471104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].de Visser SP, Quesne MG, Martin B, Comba P, Ryde U. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:262–282. doi: 10.1039/c3cc47148a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kumar D, Sastry GN, de Visser SP. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:6196–6205. doi: 10.1002/chem.201003187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]a.Evans MG, Polanyi M. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1936;32:1333–1359. [Google Scholar]

- [13]b.Kumar D, Karamzadeh B, Sastry GN, de Visser SP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:7656–7667. doi: 10.1021/ja9106176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.